9.1 Introduction

We all experience stress. It is a fact that at some point in our lives, we will face an event or moment that triggers a stress response. How we deal with stress is very different. How children deal with stress is also related to their own childhood experiences as well as the biological responses. Sometimes children find their experiences so stressful that the response is ‘I just can’t do it anymore’. And this is why our manifesto calls for new thinking about how we respond, as caregiver and educator, to the children in our schools.

I’ll start with a confession: I (Sarah Temple) am not a qualified teacher. In fact, for the last thirty-five years, I have worked across the UK in a number of different health, care and education settings. Although my main role is as a general practitioner (GP), I have also worked within community paediatrics and child and adolescent mental health services. In 2014 I founded EHCAP Ltd – a social enterprise committed to finding innovative solutions for education, health, care and prison services. My work with EHCAP was initially school based – ranging from working with early years teams through to secondary schools. More recently I have provided webinar-based training on adverse childhood experiences and the biology of stress for the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Association of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, the European Mentoring and Coaching Council and the Personalised Care Institute. In writing this manifesto, I collaborated with Isabelle Butcher. Isabelle is a postdoctoral researcher working on the ATTUNE project (understanding mechanisms and mental health impacts of adverse childhood experiences to co-design preventative arts and digital interventions), Oxford University (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui2022), and I am a senior advisor on the board of the project.

Over the years, I have heard countless stories of parents, caregivers, young people and children struggling to make sense of themselves, their relationships and the systems of schools and other services they draw upon to thrive (or survive). This manifesto aims to show the vital importance of three aspects for the healthy development of children and for improving outcomes for children, young people and families:

9.2 The Biology of Stress and the Importance of Responsive Relationships to Stress Management: Raising Awareness of the Science for Teachers

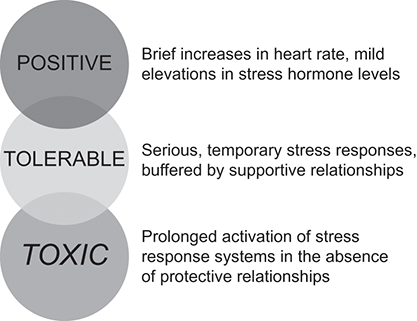

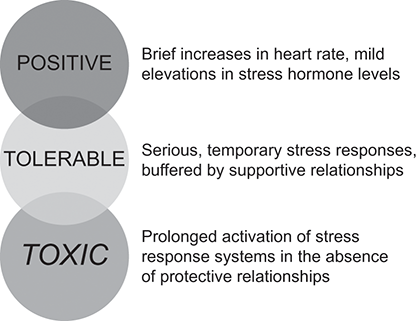

For educators working closely with children, knowledge about stress and stress responses will support them in knowing how to support the children in their care. To reduce sources of stress, we need first to understand the biology of stress responses. Shonkoff (Reference Shonkoff2018) talks about the ‘biology of stress’ in terms of the body’s physiological response to differing levels of stress. Let us consider three different responses: positive, tolerable and toxic (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Center on the Developing Child (2021) model of positive, tolerable and toxic stress.

Figure 9.1Long description

Three overlapping circles arranged in a vertical row labelled, form top to bottom, positive, tolerable, and toxic, are accompanied by descriptions of different levels of physiological responses to stress. Positive: brief increases in heart rate, mild elevations in stress hormone levels. Tolerable: Serious, temporary stress responses, buffered by supportive relationships. Toxic: Prolonged activation of stress response systems in the absence of protective relationships.

When there is a positive stress response, it is a normal and essential part of healthy development, characterised by brief increases in heart rate and mild elevations in hormone levels. Examples include things like getting to an appointment on time, getting children ready for school or preparing for a deadline.

At some point in our lives, we may face an event or moment that triggers a tolerable stress response. In this situation, the body’s stress response systems are activated at a higher level with more severe, longer-lasting difficulties. An example of this could be the death of a much-loved grandparent. Many families experienced this level of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to understand the difference between this tolerable stress response and a toxic stress response, we need first to understand what is meant by responsive relationships.

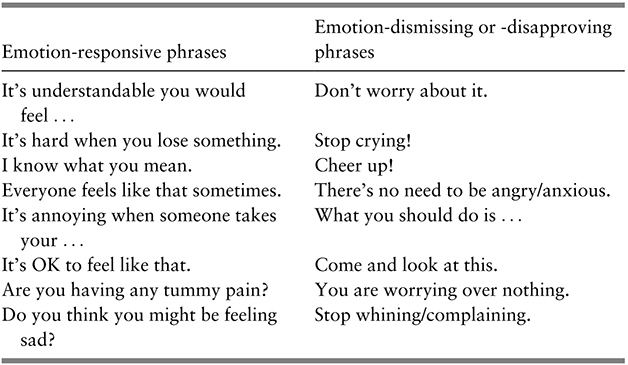

The concept of responsive relationships can be difficult to explain (see Table 9.1 for examples of emotion-responsible phrases and their opposite dimissing or disapproving phrases). In essence, responsive relationships are about an emotional connection between the responsible or close adult and the child or between two adults. The terms emotion coaching (Gottman and Katz, Reference Gottman and Katz1996) and emotion validating (Lambie, Lambie and Sadek, Reference Lambie, Lambie and Sadek2020) are often used to describe responsive relationships.

| Emotion-responsive phrases | Emotion-dismissing or -disapproving phrases |

|---|---|

| It’s understandable you would feel … | Don’t worry about it. |

| It’s hard when you lose something. | Stop crying! |

| I know what you mean. | Cheer up! |

| Everyone feels like that sometimes. | There’s no need to be angry/anxious. |

| It’s annoying when someone takes your … | What you should do is … |

| It’s OK to feel like that. | Come and look at this. |

| Are you having any tummy pain? | You are worrying over nothing. |

| Do you think you might be feeling sad? | Stop whining/complaining. |

Sometimes it can be easier to understand what a responsive relationship is by looking at relationships that are not emotionally responsive – for example emotion-dismissing or emotion-disapproving relationships. The following examples may help explain the difference between these relationship styles. In the first, Mum dismisses Max’s feelings, and in the second, Mum disapproves of Max’s feelings.

Example of a Non-Responsive, Emotion-Dismissing Relationship Style

Mum: Max, it’s time to go.

Max: I don’t want to. I hate school.

Mum: Come on Max, you know you enjoy school. Of course you’re going.

Max: No, I hate it. Why do you always tell me what I like? You never listen.

Mum: What do you mean I never listen? Now come on we need to go- I’ve got a meeting I need to get to this morning.

Max comes out of the kitchen banging his bag on the door and kicking the chair. They drive to school in silence.

Example of a Non-Responsive, Emotion-Disapproving Style

Mum: Max, it’s time to go.

Max: I’m not going.

Mum: What do you mean, I’m not going?

Max: I hate school.

Mum: That’s ridiculous, you love school.

Max: Jake’s being mean.

Mum: That’s quite enough now get into the car. You need to calm down and get your things together. Stop making such a fuss.

They drive to school in silence.

For young and pre-adolescent children, a responsive relationship with an adult caregiver means pausing, noticing and describing physical sensations associated with emotions as well as expanding the child’s awareness and understanding of different feelings associated with their emotions. Gottman and Katz (Reference Gottman and Katz1996) coined the term emotion coaching in their research, whilst Lambie, Lambie and Sadek (Reference Lambie, Lambie and Sadek2020) use the term emotion validating. Both are emotionally responsive relationships. Let’s take a look at Mum and Max’s interactions where Mum is curious, is emotionally present for her son and validates how he is feeling. This in turn allows Max to speak more and for his mum to model how an emotional response to a situation can be ‘worked through’.

Responsive Emotion Coaching Relationship Style

Mum: Max, it’s time to go.

Max: I’m not going.

Mum: What do you mean, you’re not going?

Max: I hate school.

Mum: Oh dear, what’s happened?

Max: It’s Jake, he doesn’t choose me for five-a-side now and I’m on my own at break time.

Mum: Oh dear Max (pause) – mmmm. I wonder how you are feeling about that? Are you feeling sad? Are you feeling any pain in your body?

Max: I’m feeling sick and my tummy hurts.

Mum: (pause) Yes, I understand that. When you’re feeling sad sometimes you might notice your tummy hurting or feeling sick. Are you a little bit disappointed as well?

Max: Yes. Jake used to be my best friend.

Mum: It’s OK, it’s normal to have these feelings – let’s get your stuff in the car and we can talk more on the way to school.

Max picks up his bag and walks to the car.

Adolescents respond best when adult caregivers facilitate their progression towards becoming autonomous (Havighurst et al., Reference Havighurst2010) by pausing and allowing the adolescent to express themselves – acting in a consultant role (as opposed to managerial) as the adolescent talks through their physical sensations, emotions and feelings and considers possible solutions. In countries like the UK – where children are in full-time education for as long as they are – this adolescent phase lasts into the mid twenties.

For pregnant women, responsive relationships with their partner and other adults’ buffer against the physiological impact of stress on both themselves and their developing baby or babies. Responsive relationships (e.g. emotion coaching or emotion validating) buffer against otherwise potentially damaging physiological changes of the tolerable stress response (Center on the Developing Child, 2021). This buffering effect is particularly significant in the critical phase of development between conception and the third birthday but is relevant to all ages.

A toxic stress response occurs when the body’s stress response systems are activated at a higher level with strong, frequent and/or prolonged adversity in the absence of an adult caregiver able to provide responsive relationships. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are some of the most intensive sources of stress that children can suffer whilst growing up (Bellis et al., Reference Bellis2023). In their research on ACEs, Felitti and Anda (Reference Felitti and Anda1998) devised a series of questions that intentionally included family dysfunction (mental health difficulties, addiction, domestic abuse, incarceration) as well as more traditional neglect and abuse. These difficulties make it almost impossible for adult caregivers to provide their children with responsive relationships unless they access support of some sort – for example coaching, counselling, medical input including medication or therapy.

Crucially, without responsive relationships, the stress response systems are activated at a level that can cause long-term physiological changes. As humans, we are particularly vulnerable to these changes while in the womb and during the first three years of life while our biological systems are developing. This is termed the critical developmental phase. A toxic stress response involves prolonged elevation of stress hormone levels as well as chronic inflammation. The impact during the critical developmental phase is on the laying down of hormonal systems, immune systems, metabolic systems, brain architecture and genetic systems (epigenetics).

The experience of a toxic stress response in the critical phase of development may mean a child

Is emotionally reactive

Has difficulty managing their emotions, behaviours and executive function

Has difficulty understanding what nurturing relationships and nurturing self-care are

Has difficulty with relationships (brain architectural difference)

Is cast into out-groups and has few friends

Is less able to make healthy lifestyle choices and be more likely to have difficulty with addiction, over or under eat, smoke or take drugs

Has long-term emotional, mental and physical health difficulties, including a higher risk of ischaemic heart disease, cancer, metabolic conditions such as diabetes and pulmonary conditions such as emphysema

As the child develops, there may be a period of latent vulnerability where the difficulties the child is experiencing are not recognised. When this happens, the child is likely to present to health or care services at about the age of eight or nine with behavioural issues that are causing difficulties in school and at home.

9.3 Strengthening Skills and Capabilities in Core Life Skills of Adult Caregivers

As a society, we need to notice the children who are experiencing a toxic stress response and support both them and their adult caregivers by providing education about the biology of stress as well as psycho-educational tools that strengthen core life skills in emotion literacy and emotion intelligence. It is important to maintain compassion and a clear sense of hope.

When children who experience a toxic stress response in the critical phase of their development become parents and caregivers themselves, they are likely to struggle with parenting effectively. This is sometimes referred to as intergenerational adversity. By educating whole communities we can together get better at compassionately noticing parents and caregivers who are struggling with emotional aspects of parenting – whether related to unresolved mental health difficulties, being genetically neurodivergent, having experienced a toxic stress response, or (more likely) a mix of these. The beauty of an approach that takes psycho-education tools into the whole population (universal approach) is that it avoids the pitfalls of assessment, thresholds, ‘fixes’ and referrals. This moves us away from the traditional trauma model of ‘identifying that family over there’ and then ‘doing something to them’, and moves us toward a coaching approach that encourages people to tap into and grow their internal resources; it is an affirmative model rather than a deficit one, using partnerships, collaboration and relationship development; a working-with approach to understanding that finds and explores ways to strengthen core life skills and executive function. Individuals are more likely to feel included and cared for and less likely to find themselves cast into out-groups. Understanding the biology of stress and what it means to hold responsive relationships gives whole communities the opportunity to notice those individuals who are struggling and offer compassionate support earlier.

The current system of safeguarding and child protection identifies and supports children who are experiencing high levels of stress, but unfortunately, some children ‘slip through the net’ or are identified late. We are advocating that this universal coaching approach run alongside existing services to complement and enhance their effectiveness.

The detail of the psycho-education tools that we use within EHCAP’s family wellness (sometimes known as school readiness) programme (Temple, Reference Temple2022) is beyond the remit of this manifesto, but in principle we use

Biology of stress (positive, tolerable, toxic)

An adapted version of Dan Siegel’s hand model (Siegel, Reference Siegel2015)

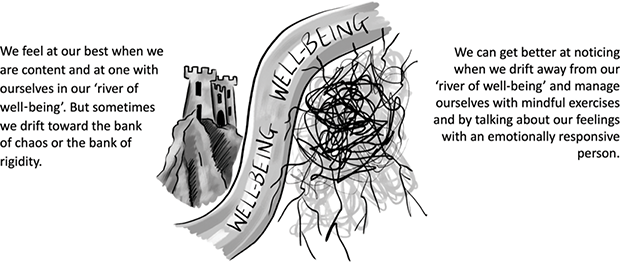

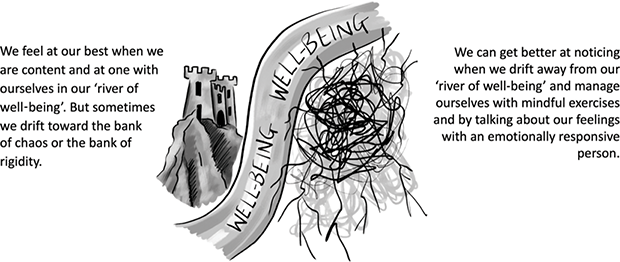

An adapted version of Dan Siegel’s river of well-being (Siegel, Reference Siegel2015; see Figure 9.2)

Emotion coaching and emotion validating

Mindful activities

Figure 9.2 EHCAP’s adaptation of Dan Siegel’s metaphor ‘the river of well-being’. Illustration: Sarah-Leigh Wills.

Figure 9.2Long description

In the middle, a curving river labelled ‘wellbeing’ separates a clifftop castle stronghold on the left and an abstract squiggle on the right. The following text is written to the left of the river, on the stronghold side: We feel at our best when we are content and at one with ourselves in our river of wellbeing. But sometimes we drift toward the bank of chaos or the bank of rigidity. The following text is written on the opposite side of the river: We can get better at noticing when we drift away from our river of wellbeing and manage ourselves with mindful exercises and by talking about our feelings with an emotionally responsive person.

Whilst, as a society, we are becoming increasingly aware of the relevance of emotionally responsive relationships to well-being and to the healthy development of the brain (Center on the Developing Child, 2011; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton2021), there are significant gaps in understanding the broader issues to do with how emotionally responsive relationships buffer against the wider physiological changes associated with a toxic stress response.

Between conception and the third birthday a complex interplay of factors such as genetics, environment (including diet, medicines, drugs or alcohol) and relationships (Shonkoff, Reference Shonkoff2018) affect the development of an individual child. A toxic stress response may impact

Learning and readiness to succeed in school

Lifelong emotional, mental and physical health through physiological changes to the

◦ brain architecture

◦ developing immune and metabolic systems

◦ developing genetic systems (epigenetics)

An individual’s ability to adapt, self-manage and thrive (manage life’s ups and downs)

An individual’s ability to engage with learning and education

An individual’s ability to manage relationships

An individual’s ability to parent effectively

Likelihood of being cast into an out-group

I recall a reflection from Jasmin (*pseudonym), a teacher and mum of two young children. Jasmin’s words point to the key principle of this manifesto: to listen with compassion, to draw from the biology of stress and to develop emotionally responsive school communities. Jasmin kindly provided this quote:

Jasmin, Primary School Teacher and Mum of Two Young Children (2022)

As a child who experienced adversity, I often struggled to identify and manage the emotions that I felt. During adolescence I remember feeling confused, unliked and worthless. My relationship with both parents was fractious, they were quite authoritative, and I often experienced what I now know as a lot of shame, blame and fear. I didn’t know how to cope with the feelings I had, for I didn’t even really know what a feeling was. Our emotional world was rarely discussed and was never deemed as an acceptable reason for any behaviour.

Looking back, I now understand that the child in me never developed the coping skills, language or ability to recognise and express how I was feeling. Because feelings were laughed at, it felt weak to show any struggle and I felt too vulnerable to express my true worries. At the same time, I didn’t want to burden my mum, who already had enough stress to contend with. I often hid my emotions or if I expressed them, it would end in upset. I quickly learnt to repress or hide them as it was safer that way.

This way of coping followed me into my teens where I found a way to seek control and cope with my feelings through food. At fourteen, I developed an eating disorder that lasted over twelve years. It was something I was deeply ashamed of and hid for as long as I could.

In my early twenties I was fortunate to connect with someone who supported me. Feeling emotionally understood and supported meant more to me than anything material. This person validated how I felt, made me feel strong, safe and ok with who I was. It gave me permission to express and explore my feelings which is when I started to journal and explore my emotional world.

Fortunately, I recovered from my eating disorder in adulthood. However, I firmly believe that this journey would not have taken almost fourteen years if I had had an emotionally validating relationship with someone from a young age; someone who accepted my emotions, helped me understand my physical signs of stress and feelings of being overwhelmed.

Jasmin’s story is not uncommon. We cannot separate people’s emotional stories and journeys from their academic or social lives. They are inextricably intertwined.

Let’s take a look at some possible ways forward that reduce sources of stress and enable responsive relationships. Some of the questions educators could consider follow:

How can teachers, schools, or communities support people like Jasmin (and her children)?

How can we move beyond the ‘firefighting’ of antisocial behaviour in classrooms towards a compassionate understanding of people rooted in a scientifically informed understanding of emotions and the biology of stress?

How do we limit judgements and instead use language that connects with feelings and needs?

How do we broaden this understanding from focusing on the brain to understanding the whole-body physiological impact of a toxic stress response and the potential impact on lifelong health and well-being?

Personalised approaches to educating and child-rearing were formally discussed in the UK by government-funded think tanks more than a decade ago (Diggins, Reference Diggins2011). However, for several reasons, they have been difficult to put into action. Simple concepts, such as empowerment and choice, are difficult to define and elaborate in groups, organisations and systems. Cultural differences within and between services and communities pose a barrier, as do practical-ethical implementation challenges and social inequalities and prejudices. Different experiences lead to different descriptors –words and acronyms – being used in schools by comparison with health or care settings. This gap in language – disrupting communication across professional contexts – can lead to children, young people and families not receiving the support they need. Communities and professional services can easily slip into blaming and shaming.

The Social Care Institute of Excellence published Think Child, Think Parent, Think Family (Diggins, Reference Diggins2011) as a blueprint for moving towards compassionate, person-centred care. This report advocates for an approach with children and families at the heart of discussions and decision-making about their care, having values of working together across systems (e.g. education, healthcare and justice) and creating a common language, while keeping safeguarding as the golden thread.

Munro (Reference Munro2011) gave us a framework for a relational approach to person-centred care. Munro states that relationships are key for healthy child development – that relationship development is the answer to the challenges faced by parents and children. Of course, why wouldn’t relationships be central to the way we work with children and their families? So, the question is, How do our systems and structures of working prevent children and their families from forming appropriate and meaningful relationships? If we know the consequences of children not receiving emotional validation, what are the barriers to changing what we do and how we do it?

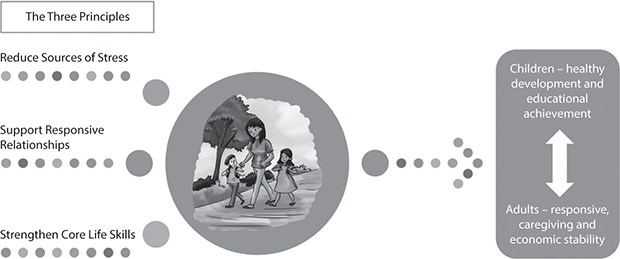

Healthcare research from multiple sources, including the Center on the Developing Child, shows that a personalised approach lays the foundation for responsive, caregiving and economically stable adults. When educational settings apply the principles of person-centredness and work together with families and communities (as well as other services), they can play a crucial role in enabling a child to succeed in school but also in their lifelong health and well-being. From an international perspective (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020), there is evidence that the interplay between a child’s genetic make-up, their environment (including diet) and their interpersonal relationships are central to their formation as individuals. Collating decades of research, the Center on the Developing Child (2021) developed three principles to improve outcomes for children and families (Figure 9.3):

Support responsive relationships

Strengthen core life skills such as emotional intelligence and executive function

Figure 9.3 Interplay between the Center on the Developing Child’s three principles and healthy development and educational achievement when a child is engaged with adult caregivers who are responsive and economically stable. Illustration: Sarah-Leigh Wills.

Figure 9.3Long description

In the centre is a circle showing two happy children walking alongside an adult on a path, with a tree in the background. To the left are three dotted lines titled the three principles, specifying: 1. Reduce sources of stress, 2. Support responsive relationships, 3. Strengthen core life skills. To the right, an arrow links the circle to a rectangle containing the impacts linked by a two-way arrow: 1. Children - healthy development and educational achievement, 2. Adults - responsive, caregiving, and economic stability.

Mindful emotion coaching, the family wellness (sometimes referred to as school readiness) programme that I have created (Temple, Reference Temple2022), holds these three principles as the foundation pillars in an outcome framework. In terms of reducing stress, we have developed a way of talking about the biology of stress with the intention that as community leads understand better this science they will work with their local communities and create their own innovations that reduce sources of stress. We have concluded that both emotion coaching (Gottman and Katz, Reference Gottman and Katz1996) and emotion validating (Lambie, Lambie and Sadek, Reference Lambie, Lambie and Sadek2020) are effective for enabling ‘serve and return’ responsive relationships. We have adapted these concepts into psycho-educational tools that are easy to access and use in everyday life. These tools strengthen core skills of emotion intelligence, emotion literacy and executive function.

9.4 Next Steps: How Do We Embed This Science in Educational and Healthcare Systems?

One way to strengthen understanding of responsive relationships is to engage with parents and adult caregivers in developing their own awareness of emotions, of the language and feeling of emotions, and of the physical sensations associated with them. The scientific advisor on the Disney film Inside Out describes seven core emotions common to all humans: joy, sadness, contempt, disgust, surprise, anger and fear (Ekman, Reference Ekman1992). Being able to connect with children experiencing difficult emotions, such as fear, worry, anxiety and anger, is an important aspect of emotion validation/coaching because it builds emotional literacy and emotional intelligence, which in turn enables more effective executive function.

Lambie, Lambie and Sadek (Reference Lambie, Lambie and Sadek2020) show that teaching emotion validation skills to parents in a social care setting leads to children becoming calmer and more accepting of negative emotions. Lambie and colleagues have collaborated with the publishing company Skylark Online to create commercially available resources for parents and adult caregivers of babies and young children. Rose and Temple (Reference Rose and Temple2017) researched emotion coaching with children in schools and created lesson plans and resources for schools spanning from age three to nineteen. Havighurst et al. (Reference Havighurst2010) have created a suite of parenting programmes, called Tuning in to Kids, that seek to forge emotional connections between parents and children. These programmes have also been shown to improve emotion socialisation practices in parents of preschool children. The Happy Child Parenting App (Larson and Banks, Reference Larson and Banks2020) provides user-friendly video footage demonstrating responsive relationships.

According to Gottman and Katz (Reference Gottman and Katz1996), holding an emotion coaching relationship style at least 30 per cent of the time improves children’s ability to nurture relationships and cope with life’s ups and downs, and is likely to result in superior academic achievement. The change in emphasis from the predominant (in Western society) emotion-dismissing style to an emotion-coaching style can have surprising knock-on effects for the child as well as the parent. The following excerpt is about the experience of a mum with a baby and a toddler.

Mum of a Baby and Toddler (2022)

Initially, I didn’t really understand what emotion coaching was all about but as I listened to the information about the biology of stress, and in particular the toxic stress response, I started to understand how the trauma I experienced in my childhood was impacting on my baby and toddler – as well as my marriage. Gradually, I felt able to begin working with a counsellor and healer. I started to understand how reactive I am to stress and to learn how to calm myself and manage my emotions before interacting with my children.

While schools focus on children’s education, a teacher or teaching assistant could – with knowledge about the biology of stress – listen differently, respond with more compassion and resist the temptation to make judgements. They could also connect with the parents and adult caregivers with coaching style trauma–informed conversations. Consider Ellie:

Ellie, Mum of Two Daughters (2022)

I first went on anti-depressants/anti-anxiety medication after a period of undiagnosed post-natal depression and parenting a neurodivergent child. I tried to reach out for help to the GP, to school and even in earlier years to health visitors. I was a well-presented, middle-class parent who in public had well-behaved children. No one paid attention to me. I doubted my parenting and myself. I wanted and needed help but didn’t know where to go and no one took me seriously. I tried to get help via various online resources but still felt misunderstood until I came upon a Family Wellness Coach. The coach not only made me feel normal, she made me feel supported and helped my husband understand how being neurodivergent can affect a child’s ability to manage their emotions.

The journey is still hard, but I no longer feel alone. Family Wellness Coaching gave me the confidence to understand I had to do what was best for my child and that in turn has given me more confidence to access support.

Being involved in workshops about emotions or emotional literacy and the biology of stress raises awareness and makes a difference for those involved and their families. Listen to Amanda’s experiences:

Amanda, Mum of Four (2022)

I honestly can’t explain just how life changing the introduction of mindful emotion coaching has been to my family and I. … Although it wasn’t always easy, over time it became easier to remain calm and choose an emotion coaching response in those challenging moments. I found that teaching the children to tune into the physical sensation in their bodies helped massively. They learned to notice their stress sooner and while it was at a more manageable level. The children’s emotional literacy also developed significantly. One of my children went from only being able to identify good and bad feelings, to being able to identify and label complex emotions like shame, resentment and compassion.

Different sectors working in partnership is key; the siloed thinking of subject domains (e.g. health and education as separate entities) is not helping our young people to flourish. Box 9.1 illustrates the actions taken in one school in the UK where a passionate headteacher (Kate Nester) worked with a family support advisor (Andy Leafe).

Hindhayes Infant School is in Street, Somerset, UK. Both Kate and Andy trained as mindful emotion coaches in 2015 and have adapted this training to meet the needs of their community and setting, embedding sustainable, relationship-based, child-centred care by

Creating a clear vision which they shared across staff, pupils and families and into the local community

Focusing on relationships – staff to staff, staff to parents and carers, staff to children and child to child

To implement these steps, they developed the following:

Curriculum design. Underpinned by a trauma-informed approach, following Kidd (Reference Kidd2020) and her ‘Curriculum of Hope’. The five areas of coherence, credibility, creativity, community and compassion now provide clear headings for school staff and the wider community. Stickers have been added to the children’s books and a strapline created – ‘Hindhayes, Kind Ways – Kind to self, others, school, community’. This approach made asking ‘are you OK?’ normal.

Recruitment processes. Embed a need for staff to have meaningful relationships with children in their care. This led to a reduction in the use of bank staff and an expanded role for teaching assistants (TAs) as play workers.

A learning culture. All staff, from TAs to senior leaders, are given space and time in the curriculum for their own learning.

Outdoor activities with Forest School. Every child has one half day a fortnight, with more vulnerable children having access once a week, depending on needs.

Community engagement. Volunteer roles are offered to isolated, vulnerable parents in the Forest School, which runs in both term time and holidays, providing an opportunity for connecting with parents and carers and skill building, for example by joining in with food preparation and fun activities, supporting effective parenting through play in adult caregivers.

Solution Circles. Once a week in a staff meeting, we talk about a challenging situation.

Behaviour policy transformed into relationship policy. Both consequences of behaviour and repair happen in school through a recovery curriculum, ‘correction through connection’.

Andy trained to run both Tuning in to Kids and Tuning in to Teens groups for parents (both programmes promote emotion-validating relationships). He has merged learning from Family Links and, using the mindful emotion-coaching approach, empowers parents to enhance their executive function through the use of psycho-educational tools. Andy creates his own easy-to-access resources for parents and carers, including information based on the biology of stress, emotion coaching and mindfulness. Mindful activities have been particularly helpful for staff as well as parents and carers, for example in the transition from home to school after drop-off. Kate has continued to develop her leadership skills and has drawn on multiple approaches to building emotion intelligence, recognising that no one size fits all and adapting her learning to meet the needs of children and families in her setting. This includes the innovative use of ‘Oops’ cards, which normalise moments when things just don’t go to plan.

The key issue in this example is the combination of leadership from Kate and the skill of Andy in networking with the community to connect with both children and families with a mindful emotion coaching approach. Building emotionally supportive futures is essential if we want our children and their caregivers to flourish, to move out of toxic stress and to live wholesome, healthier and more emotionally connected lives.

9.5 Conclusion: Building Emotionally Supported Futures

An emotionally supported, trauma-informed and personalised future is very much needed, especially in a post-pandemic world that has exacerbated inequalities and left many with high or toxic stress in their lives. Feelings matter, and the emotional well-being of families and children matter, not only for them but also for communities and society at large. If school professionals can help communities improve their understanding of the biology of stress and the protective buffering effect of responsive relationships, then there is the possibility that together we can reduce the number of children in our society who experience a toxic stress response (with all the potential lifelong emotional, mental and physical health difficulties associated).

The key questions that now must be asked follow:

How do we start conversations about the biology of stress, and how do we incorporate what we know into lesson plans, curriculum and behaviour policy as well as into our communities?

How do we support teaching staff to talk about difficult topics?

How do we notice and support those children who have experienced or are currently experiencing a toxic stress response?

Looking forward, further research and curriculum development needs to be orchestrated through community leaders as well as a multi-agency approach. This must include health and care professionals, educationalists, government support agencies, third sector organisations, community groups and people with lived experience of a toxic stress response.