I met Jack, officially known as John Bradbury Penney, Jr., at the reception at Dean David Roger’s house the night before my first day at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (Figure 3.1). Most of the students were dressed up and looking very straight. I joined a bunch of people hovering together who had more facial hair and seemed more liberal. Jack was one of them and he was expounding on being a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and how awful the Vietnam War was. I mostly agreed with his opinions, although I wasn’t in favor of the violence groups like SDS espoused. I also found him way too vocal and aggressive. I didn’t realize it at the time, but a loud and talkative Jack was a break from his usual quiet personality. We all went out after the reception to drink beer. I was thinking that this medical school thing might be a drag. I couldn’t see myself hanging out with the guys wearing ties and jackets, but I wasn’t exactly charmed by the loudmouth liberals with whom I presumably had more in common.

The first weekend I was in Baltimore, there was a party at the Pithotomy Club, an eating club for male medical students only. Female medical students and nurses were invited to parties, and I decided to go. The party was a typical medical student party with lots of beer and dancing. All of a sudden, we heard shots ring out on the street. The medical students rushed out onto the street. A man had been shot right in front of the club. A real opportunity for the students to practice their skills! They crowded over him, trying to revive him by CPR and attempting to stop the bleeding from the wound. A group of them carried him up the street to the emergency room.

A month or two after starting medical school, a biochemistry graduate student asked me to go with him to his professor’s house for a party. At the door I was introduced to the professor. “Anne Young! Oh, I have a great story to tell you!” He said he was on the Admissions Committee when my application came up for review. The file was huge. Twice the size of others! The committee soon realized it contained material from two applicants named ‘Anne Young.’ They spent an entire meeting sorting out the two applicants. After finally getting one pile of the Anne Young they didn’t want and a second of the Anne Young they did want, they had to contend with a letter that couldn’t be associated with one or the other. The letter was from a psychiatrist who said, “Anne Young is completely crazy and should never be a doctor.”

I didn’t say anything. I wanted to get away from the door and into the party. I was the crazy applicant described in the letter. I had naively allowed all my medical records to be submitted along with my medical school applications. Back in those days, medical schools encouraged (but didn’t require) the applicant to send in records.

I stood there while the host professor told me that Hopkins Professor Mary Betty Stevens (a Vassar alumna) had checked me out at Vassar and decided that I was fine. I took a deep breath. I had gotten into med school by the seat of my pants.

My first impressions of the people I’d gravitated to that first night at the dean’s house gradually became more positive as I got to know and become part of a small group of students who sat at the back of the lecture hall, reading the New York Times and talking about civil rights, the antiwar movement, drugs and the need to help the poor. I learned quickly that Jack was a very quiet man – not the loudmouth I saw the first night. He also had an incredible fund of knowledge having read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica when he was a child. Our group became lifelong friends and colleagues: Walter Henze, Darrell Salk (son of Jonas Salk who produced the first polio vaccine), Jack, Jeremy Tuttle and me.

Whenever Jack sat near me, I noticed this really bad smell coming from under the chairs. I soon realized that the smell emanated from Jack’s feet. In his attempts to be a hippie, he wore jeans, wool shirts and Birkenstocks with no socks. His feet sweat and his sandals stank. In my usual subtle way, I said that if he didn’t fix the stink in his feet, he shouldn’t sit next to me. He did fix it! He started wearing socks (and as I learned later, he was spraying his feet with foot powder). He got a new pair of Birkenstocks. That was my first sign that he liked me. And I liked him.

A group of us attended the big Second Anti-War Moratorium in Washington, DC on November 15, 1969, to protest the senseless Vietnam War in which too many Americans were dying. Although we weren’t exactly invited to help, we decided to go and be prepared to help any people who were hurt or fell ill. The war felt very real to us especially because Jack had received a very low lottery number from the Draft Board – meaning if he wasn’t in medical school, he would have been drafted into military service. We wore our white coats and black armbands and were prepared to take care of minor wounds and tear gas with water bottles and cloth strips. There were half a million protesters and by the end of the evening the march deteriorated into throwing sticks and stones. The police heavily tear-gassed the crowd. At least we had water-soaked pieces of cloth to help people breathe and see.

That spring, Jack announced that on March 7 there was going to be a total eclipse of the sun. He always followed celestial events by reading the relevant sections of the Baltimore Sun and Scientific American. The band of totality was going to fall across the southern tip of the Eastern Shore of Maryland and northern Virginia. Walter, Jack, Lynne Gerson (a fellow medical student) and I decided to miss classes to go and see it, since this was the event of a lifetime. We got in Walter’s VW and started off toward the Eastern Shore. It was spring and the weather was clear and fresh. We had to go over the 4-mile-long Chesapeake Bay Bridge to the Eastern Shore and I thanked my lucky stars I wasn’t driving. We drove on as far as we could until we were way down the shore and out in the boonies with no clear idea of where we were. At about 10 p.m., we came to a dirt road and followed it until we found a little place where we could put down our sleeping bags. We all fell asleep. It was chilly but we were all excited about the next day.

As the first light came, there were sudden explosions all around us! What was happening? It was gunfire! We were petrified when we realized that we were on the edge of some marshes and guns were being fired from several directions. We were in the middle of a duck-hunting preserve! We instantly packed up our sleeping bags and stuffed them in the car and hightailed it out of there. We got back on a paved road and decided to try to get as far south as possible. When we neared the end of the peninsula, there were stretches of salt marshes. We parked and picked a path out into the marshes. It was an absolutely clear, cool, cloudless day. We pulled out a joint and got stoned. Rushes lined the pathway, and you could see up and out but couldn’t see anything beyond five feet side to side. We walked out along the path and, after about half a mile, we turned a corner and there in front of us was a clear area where a man and his young son had set up all sorts of equipment to see the eclipse. He had several telescopes and cameras on tripods. He had a large white sheet spread out and anchored by rocks to see the interference waves in the seconds before totality. The guy was very nice and invited us to stay. He was obviously an astronomy buff and Jack was absolutely thrilled.

As the eclipse began, we looked at it through the man’s special telescope and pinhole projections on the ground. As totality neared, we noted that all the shadows became absolutely crisp since the sun was closer to a point source. When I held out my hair, I could distinguish all the individual hairs! As it got darker, it got colder by about 15 degrees. The shore birds started returning to land en masse somewhat confused about what was going on. As totality approached, interference bands raced across the spread-out sheet and suddenly the sun winked out and all we could see was a ring of fire surrounding the moon. It lasted several minutes, and we all relished the moment together in this most beautiful of places. After the event, we piled back in the VW and headed back to school feeling a little richer for the shared experience. Along the way, we stopped to eat, and Walter ate three dozen raw oysters in celebration. That night, he became terribly ill to his stomach as a consequence of his gluttony.

That trip was the longest time I had spent with Jack. I liked him.

That spring, Jack and I spent more and more time together. In May, I invited him and Walter Henze to my room to watch the Kentucky Derby, drink mint juleps and bet on the races. When I was young my mother liked to say, “Why don’t you call up one of your friends to play.” I was sure they would hate it if I called. I was always hoping someone might call me up to come over. Even as an adult, I avoided calling strangers on the phone and had to work up my courage to call Jack and Walter, who accepted my invitation. When the day came, I set up the mint juleps and had snacks and the TV all ready. But they didn’t show up. I was crushed. Later, I found out they’d decided to go out with someone else. In the end, it didn’t really matter because two weeks later we all went to the Preakness Stakes in Baltimore and watched the horses from the infield. Three years later, we saw Secretariat win the Preakness as part of winning the Triple Crown – winning the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes and the Belmont Stakes.

Plenty of the medical school lectures at Johns Hopkins were dry and boring, but some lecturers were remarkable. Professor Richard T. Johnson, a neurologist who pioneered studies of viruses infecting the nervous system, showed exciting movies of his research trips in the field. He showed an unforgettable film of a remote tribe in the mountains of Papua New Guinea that suffered a strikingly tragic and fatal disease called kuru. The disease caused trembling, followed by shrinkage and wasting of the muscles and loss of all coordination, resulting in death in one to two years. In 1964, Johnson joined the medical researcher D. Carleton Gajdusek in Papua New Guinea and filmed people affected by kuru. His movies showed the amazingly disorderly movements of the affected individuals. Gajdusek had demonstrated that people contracted the disease via their funerary rite of smearing the brains of dead relatives on their bodies. Whether it was a virus, bacteria, parasite or something else was unknown. Jack and I met Gajdusek at Johnson’s house one evening where he talked about his adventures and his theories of what caused kuru. We decided then that it would be cool to be part of a study that took us to remote parts of the world – a wish that came true years later when we did field research in Venezuelan stilt villages.

Whereas Johnson kept his lectures interesting with exciting medical content, more typically professors resorted to what was apparently an approved gimmick to keep the students’ attention: sprinkle every lecture with slides of Playboy pinups or lewd jokes. There were only 10 women in our class of 114 and so the women were expected to just tolerate the lewd material. I noticed that Jack and his ‘liberal’ friends were just as sexist as the rest of the class. Once when a woman gave an incredibly lucid lecture on infectious disease, all the guys tuned out almost as a matter of principle. It really pissed me off and I told Jack that I felt that way. He admitted that he’d tuned out and was embarrassed about it.

Despite this crude educational approach, there were two women at Hopkins who really impressed me. One was Professor Helen Taussig, a pediatric cardiologist who went completely deaf as she got older and thus couldn’t use a stethoscope to listen for various kinds of murmurs. Nevertheless, she could diagnose the most complex child by simple observation and the feel of the vibrations in the chest. Truly extraordinary. The other woman was Chief Resident in Medicine – a position reserved for the best – who had graduated from Vassar several years ahead of me and then attended Harvard Medical School. I once saw her present a complicated patient at Grand Rounds before a large audience and a front row seated with the giants of Hopkins Medicine – A. McGehee Harvey, Philip Tumulty and Victor McKusick. She was blonde, and in a short white skirt and short white jacket, she reminded me of Barbie, the doll. She spoke for 15 minutes summarizing all the details of the patient without pause and without uttering a single ‘Um’ or ‘Ah.’ It was perfect. She then confidently answered all the intentionally tough questions posed by the greats – again in full sentences without pauses. Bernadine Healy later became the first female director of the National Institutes of Health. These two women taught me to maintain confidence, never quit and to continue on despite barriers.

Summer was fast approaching. I wanted to work in a lab. Who should I work with? There were so many possibilities.

I asked multiple graduate students in different departments who I should talk to. Several people who knew of my potential interest in the brain suggested I speak with Solomon Snyder. He was then a young man who had recently joined the faculty of the pharmacology department while at the same time finishing his residency in psychiatry. He was working on neurotransmitters and drug effects on the brain.

I made an appointment to see him and was so excited that I went to the library and put together a proposal to study the effects of the blood pressure drug reserpine on potential amino acid neurotransmitters. Sol had lectured on reserpine and its effects on adrenaline release. Maybe it had an effect on other potential neurotransmitters.

Sol’s office was on the fifth floor of one of the main medical school buildings a block from the hospital. The office door opened into a room where his secretary was working at a desk next to another door to his office.

I announced myself and his secretary knocked on the door. Sol came out to meet me. He was thin, about 5′10″ and had light brown hair. I’m not sure what kind of person I expected but I immediately felt at ease. He did not appear physically strong, and his handshake was surprisingly weak. With a soft voice, he motioned me into his office. A large window looked out over the poor neighborhood below. His desk faced away from the window toward the inside of the office. There was a sitting area with a couch backed up against the desk and two chairs facing the couch. A whiteboard on the wall had lots of scribbles on it. I took a seat in one of the chairs.

“What can I help you with?” he asked.

“Well, I’m really interested in the brain and biochemistry. I’d like to learn more about it. I actually wrote a proposal for a lab project for the summer.” I handed him a copy of my proposal.

He looked it over politely as we talked. He asked me about my previous lab work, and I told him about my summers working in hospitals and my college honors thesis. I found him easy and enjoyable to interact with. He was so supportive and enthusiastic about my exploring brain chemistry that I came right out and asked, “Would it be possible to join your lab this summer?”

He did not hesitate. “Absolutely. I can provide you with a small stipend as well.”

What great news. Now I had this exciting summer of science ahead.

Most of the medical students lived in a dormitory across the street from the hospital. There was a basketball court and a swimming pool by the building. One evening, Jack and I sat by the pool talking and a second-year medical student came up, looked down at me and said, “Women shouldn’t be doctors. They should be at home taking care of the children and their husbands!” My playground instincts instantly returned. I jumped up, looked him in the eye, hauled off and hit him as hard as I could right between the eyes. He didn’t fall back much at all and instead he hauled off and hit me back, decking me to the ground. Jack didn’t do anything in response but just let it all play out. Clearly the wisest response.

I moved out of the medical school dorm at the end of my first year when two college friends, both taking creative writing courses at Hopkins, moved out of their apartment at 311 East 30th Street near the main Hopkins campus a couple of miles from the medical school. I moved into the apartment with Les Moore, who’d begun a job working in a sleep physiology laboratory in Baltimore. She brought along her boyfriend. As far as I could tell, he was neither going to school nor working. When I came home from work, Les and I and the boyfriend got stoned and/or drunk and hung out.

I was 22 that summer and it was my first time working in a pharmacology lab. That year, 1970, was the year the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to three scientists for discovering how chemical transmission worked between a nerve cell and the next neuron, gland or organ. At the time, physiologists specialized in recording brain electrical activity in response to specific behaviors. Although most thought that chemical transmission between nerve cells did exist, the prevailing belief was that transmission was primarily electrical. Electrical activity could be measured in living animals and was still considered to be a factor, but the Nobel work was groundbreaking in that it showcased the important role played by chemical transmission.

Sol Snyder had been a student of Julius Axelrod, a member of the Nobel Prize–winning team. So, by the time Sol came to Hopkins, he had already been intimately involved in the research that led to the discovery of the first chemical transmitters. His lab was to continue research into the chemistry of the brain. When I began my lab work, only four chemicals were widely considered as neurotransmitters: acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid). We had no clue at the time about the chemical transmitters for 90 percent of the brain neurons.

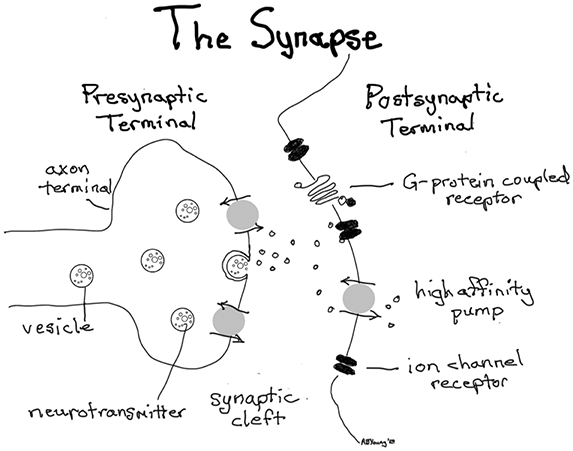

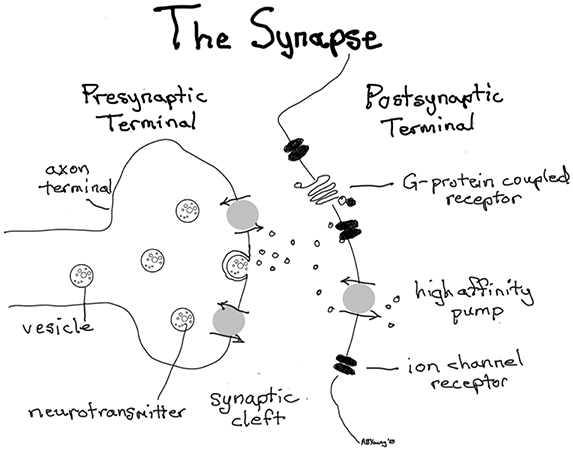

Neurotransmitters are basically messengers in the brain. They are chemicals released by nerve cell activation. The junction between one nerve cell and the next is called a synapse (Figure 3.2). Small vesicles (beads of membrane filled with the transmitter) fuse with the surface of the nerve ending at the synapse. The transmitter is released into the synaptic cleft and diffuses across to the next nerve cell where it binds to a receptor like a key in a lock. This is how the signal is passed on. Of course, as in a well-tuned security system, the receptors are very specific and selective and will only interact with certain chemicals. At each step, the processes in the brain can be modified by various enzymes, proteins, vitamins, hormones and drugs. The four accepted neurotransmitters we knew about thus far were all unique chemicals not used in any of the body’s other cellular functions.

Figure 3.2 The synapse. There are trillions of synapses in the human brain. Each synapse is unique but influenced by the other neighboring synapses. The transmitter is stored in vesicles that fuse with the presynaptic membrane to release the messenger when the presynaptic terminal is activated. The transmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft to activate specific postsynaptic receptors. The transmitter action is then terminated by special potent pumps that remove the transmitter from the cleft.

In Sol’s lab, several postdoctoral fellows were looking at amino acids as potential neurotransmitters. We knew that amino acids are the basic building blocks of proteins that are found in every cell in the body. Could they also be involved in something completely different than building proteins? If so, how could amino acids both be critical components of proteins and have secondary functions as neurotransmitters? There are 20 amino acids and each is present in high concentrations in all body parts. Could any or all of those 20 be involved in neurotransmission? Even the question was controversial back then. Identifying any of them as a neurotransmitter would open up opportunities to find drugs that affect their functioning. Finding new transmitters of any kind would allow scientists to develop a more complete map of the brain’s neurotransmitter pathways. For all these reasons, I was excited to be involved in the study of amino acids as potential neurotransmitters. It was then a significant, cutting-edge area of research where discoveries could be made.

Over the summer, Jack went back to his home in Boston to work in a lab at the University of Massachusetts. Between the time he stood me up for the Kentucky Derby and the end of the term, we’d made love in my little dormitory room and fallen in love. I adored his sparkly hazel eyes, his thick beard and hairy chest. He had a strong body. He smelled good. He was quiet yet always knew the right information. We both wanted to be together, and I knew I would miss him when he was in Boston. Jack and I wrote letters back and forth and his were very cute and clever. I don’t think he saved my letters – if he did, I don’t know where they are. We managed to get together a couple of times over the summer.

One long weekend, Walter and I visited Jack at his grandmother’s farm in southern New Hampshire. We arrived around five in the afternoon and Jack’s father came out to greet us. “Hi,” he said cheerfully. That’s the last word I heard from him all weekend. Jack’s mom and grandmothers were talkative and interactive. Meanwhile Jack’s dad smiled and laughed and served the food and helped with the dishes but didn’t say anything to any of us. I asked Jack what was going on and he said that his dad was just a bit shy and a man of few words.

During the week, work in Sol’s lab kept me busy. Sol had put me on a project measuring the level of histamine (a chemical associated with allergies) in the rat brain. A prior member of his lab had found high levels in the brain. What was it doing there? Could it be a neurotransmitter? First, I measured the localization of the histamine in the nerve cells. I then measured the histamine at various ages of the rat. I found out that the increased histamine was greatest in the newborn brain. It was highest in the nucleus of the cell and very low in the synaptic terminal where neurotransmission took place. My experiments allowed us to rule out histamine as a neurotransmitter – more likely involved in the development of the brain and the function of the nucleus.

Five or six postdoctoral fellows and several students shared the lab with me that summer, and by the time I got to work at 8 a.m. somebody else was already there. Each of us had an assigned work area at one of the six lab benches. We all had different backgrounds and training, which made our frequent scientific and political discussions especially interesting. We might argue loudly and vehemently, but no one was aggressive. Sol was brilliant and fun to talk to about science.

Sol’s lab was right next to his office, which made it easy for him to meet weekly with each lab member. He carefully went over all the actual numbers in my lab book, looking for any additional information in the data I might have missed. If experiments were outside his expertise, he didn’t hesitate to call up a colleague and arrange for me to go learn a new technique in the colleague’s laboratory. I was excited by the work in the lab and was eager to be someone who made discoveries in the world. Discovering more about transmitters and drugs in the brain was definitely an adventure. During college, when I’d sat around with my English major friends who talked about books, I wasn’t a match because my dyslexia meant I was very ignorant of classic literature. Instead, I was the scientist among the Pigs. I’d say, someday we’re gonna be able to manipulate the genetics of our systems. We might be able to cure diseases or create monsters. I liked to think about all the things humans might come up with.

Sol was willing to listen to my ideas and guided me in how to examine them. Julius Axelrod had taught him to design short ‘pilot’ experiments to test out new ideas. Some scientists are inclined to carry out long, large, all-inclusive experiments right out of the starting gate. Such experiments often failed not because of the design but rather because the experiments were too large and unwieldy. Better to design a shorter and smaller 12-tube experiment that indicated ‘yes’ or ‘no’ about the central idea.

During another long weekend visiting Jack in New Hampshire, he took me for a walk out across the field by a ledge and down the slope to where a grove of small beech trees crossed the field. A path wound its way through the cluster of thin trunks and then broke away into another little meadow that stretched up a slope. The meadow was covered with the most delightful speckling of little red dots – wild strawberries. We spent hours picking until we had about two quarts of the precious, tiny berries. Jack’s mother, who put up all sorts of fruits every year, helped us decide how to preserve the berries. We decided that it might be fun to try the recipe for ‘sunshine strawberries’ from Fannie Farmer’s cookbook. We mixed the berries with sugar, boiled them for 20 minutes and then spread them on glass platters and covered them with plastic wrap. We put them on the roof of the house in the full sun. The next day we both had to go back to school, so we put them on the shelf above the rear seat in Piglet, my VW bug, and tootled back to Baltimore where we put them on the roof again for three more days and then packed them up into sterilized glass jars and sealed them with wax. I don’t think Jack and I have ever tasted better strawberry preserves.

I loved to visit the farm in New Hampshire. Jack’s mom was always making something delicious. She taught me how to make several breads that Jack and I then made routinely back in Baltimore. She made an excellent roast and then whipped up Yorkshire pudding with the grease. Her soups and stews were outstanding, and we always had frozen fresh vegetables grown in her garden. She and I had several other projects together such as stenciling a border of flowers around one of the upstairs bedrooms in the farmhouse. She was so easy to talk to and we talked about all sorts of practical and funny things. Although she didn’t approve of sugar in tea, which meant I quickly learned to drink tea ‘neat,’ she was unlike my mother, who was always critical and argumentative. From the beginning, I was always completely comfortable with Margaret.

Jack and I loved to swim and often the weather at the farm became hot and oppressive. When it did, we drove the quick five-minute ride down to the dam on Bow Lake and went for a delicious swim in the fresh, clean water. The lake was beautiful with little islands sprinkled around the periphery and a dam at one end which controlled the water level. It is a glacial lake and there was no public access, so we had to have a little medallion to prove we had a right to swim there. The only problem with the lake was that once we had gone for a swim and were refreshed, we had to dry off, get in the car and head back to the farm. By the end of the short five-minute drive, we were hot and sweaty again.

At the end of the summer rotation, I asked Sol if I could get my PhD in his laboratory in the Department of Pharmacology. I had a year and a half left of my science and clinical rotations and I proposed joining the lab after that. He said there should be no problem. I made an appointment to meet with the dean. At the time, the Hopkins MD program had only 2.5 years of required courses. The rest were elective. I asked the dean if I could use all my elective time toward getting my PhD. He agreed. I asked if he would put that in writing. He gave me such a letter the next week.

I then went to the pharmacology department and asked the chair if I could get a PhD in their department working in Sol’s lab and he said yes.

“Could the Medical School courses in biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology count for the PhD?” I asked. This seemed reasonable since various departments counted these courses for graduate students.

“Yes,” they said again.

I asked if I could get that in writing and they gave me a letter soon thereafter. I must say I don’t know what drove me to ask for those letters, but it turned out to be a good thing later.