Introduction

Iron silicides are a relatively rare family of minerals with only seven Fe-silicides having been approved as minerals by the IMA: suessite (Fe3Si), xifengite (Fe5Si3), gupeiite (Fe3Si), hapkeite (Fe2Si), luobusaite (Fe0.84Si2), linzhiite (FeSi2) and naquite (FeSi). Among these, hapkeite has been reported to occur in different environments. As terrestrial occurrences, it has been found in three locations. (1) In corundum xenocrysts in Late Cretaceous pyroclastic ejecta from Mount Carmel (northern Israel), associated with alluvial deposits in the Kishon River area (e.g. Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Griffin, Huang, Gain, Toledo, Pearson and O’Reilly2017; Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Gain, Saunders, Huang, Alard, Toledo and O’Reilly2021). At Mt. Carmel, large corundum grains contain several forms of iron silicides, including gupeiite, xifengite, naquite, hapkeite, and an unnamed Fe5Si, either pure or in combination with Ti and P (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Gain, Huang, Saunders, Shaw, Toledo and O’Reilly2019, Reference Griffin, Gain, Saunders, Bindi, Alard, Toledo and O’Reilly2020). (2) In carbonate xenoliths of Neogene basalts at Dalihu, Inner Mongolia, China (Liu et al., Reference Liu, He, Gao, Foley, Gao, Hu, Zong and Chen2015; He et al., Reference He, Gao, Chen, Liu and Hu2017). At Dalihu Ni-rich hapkeite (empirical formula: Fe1.56Ni0.49Si1.00) coexists with Ni-rich suessite (empirical formula: Fe2.92Ni0.02Cr0.01Si1.08) and an unnamed Fe2.86Ti0.19Ni0.16Al0.11Si7.00. (3) In limestones of the Targhasa reef massif, Eastern Sayan mountains, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia (Eremenko et al., Reference Eremenko, Polkanov and V.K1974), hapkeite is associated with naquite, linzhiite, xifengite, unnamed FeSi9, unnamed Fe3Si2, and unnamed Fe4Si9 (Rappenglück, Reference M.A2022). Natural silicides – including hapkeite – have also been reported in the streambed of a tributary to the Sheshenyak Minor River (Basu et al., Reference Basu, Murty, Shukla and Shukla2000) between the Alatau and Kalu ranges, close to the abandoned settlement of Utar-Yurt (Southern Urals, Ishimbayskiy rayon, Russia). Here, hapkeite is associated with gupeiite, xifengite, naquite and other exotic phases such as Fe7Si2, Fe3Si2, (Fe,Ti)4Si5, (Fe,Ca,Ti)5Si4, and (Fe,Ca,Ti)4Si7. Lastly, hapkeite is also known to occur in either natural or anthropogenic fulgurites, along with other unusual compositions such as Fe8Si3 and Fe7Si3, as well as Fe–Si–Al alloys like FeTi(Al,Si)2, Fe(Al,Si)3, Fe(Al,Si)5 or Fe5AlSi10 (Ramírez-Cardona et al., Reference Ramírez-Cardona, Castro and Cortès Garcia2006; Sheffer, Reference A.A2007; Pasek et al., Reference Pasek, Block and Pasek2012; Abbatiello et al., Reference Abbatiello, Bindi and Pasek2025; Morana et al., Reference Morana, Pasek, Catelani and Bindi2025).

As an extraterrestrial occurrence, hapkeite has been reported in Comet 81P/Wild 2, associated with suessite, unnamed (Fe,Ni,Cr)Si and an unnamed Fe7Si2 (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Tsuchiyama, Akaki, Uesugi, Nakano, Takeuchi, Suzuki and Noguchi2008). These iron silicides are thought to have been produced by a hypervelocity impact of (Fe,Ni)-S particles, leading to a temperature above 1400 K, heating the aerogel substrate (containing Si), melting it and mixing matter from the particle and the aerogel (SiO2), followed by rapid cooling. Hapkeite has also been reported with naquite, linzhiite, gupeiite, P-bearing suessite, and Cr-bearing xifengite in the lunar meteorite Dhofar 280 (Anand et al., Reference Anand, Taylor, Nazarov, Shu, Mao and Hemley2004 and references therein), and in one of the samples from crater ejecta blanket at the Mare Crisium landing site returned by the Luna-24 mission (Ashikmina et al., Reference Ashikmina, Bogatikov and Gorshkov1979). It was also discovered in association with suessite and naquite in the polymict DAG 1066 meteorite (Dar al Gani, Libya; Moggi Cecchi et al., Reference Moggi Cecchi, Caporali and Pratesi2015), in the ureilite EET 83,309 (Elephant Moraine, Antarctica; Herrin et al., Reference Herrin, Mittlefehldt, Downes and Humayum2007), and in the FRO 90,228 dimict ureilite (Smith, Reference C.L2008), all indicating an origin as impact-induced melt phases.

In impact-related material, hapkeite (Fe2Si) has been reported in magnetic spherules (100–200 μm) from Üveghuta, Lower Carboniferous Mórágy Granite Complex, Tolna County, Hungary, and from the Mesozoic Gemeric Granite Complex, and thought to be either extraterrestrial dust or remnants of a meteorite impact (Szöőr et al., Reference Szöőr, Elekes, Rózsa, Uzonyi, Simulák and Á.Z2001). Also, together with gupeiite and probably naquite, it has been found in a rock from the Koshava gypsum deposit, Moesia region, Northwest Bulgaria (Yanev et al., Reference Yanev, Benderev, Zotov, Dubinina, Iliev, Georgiev, Ilieva and Sergeeva2021). This exotic rock was initially identified as a meteorite, but since then, it has been reclassified as an impact ejecta. In addition, previous research into a proposed group of airburst/impact craters in Chiemgau, Germany, identified gupeiite, xifengite, hapkeite, naquite and linzhiite in glass (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hiltl, Rappenglück and Ernstson2019; Ernstson et al., Reference Ernstson, Bauer and Hiltl2023). Iron silicides were also reported at a proposed 12,800-year-old airburst/impact site within the prehistoric village of Abu Hureyra, Syria (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kennett, Napier, Bunch, Weaver, LeCompte, Adedeji, Hackley, Kletetschka, Hermes, Wittke, Razink, Gaultois and West2020, Reference Moore, Kennett, Napier, Bunch, Weaver and LeCompte2023), but their impact-related origin has been challenged (e.g. Holliday et al., Reference Holliday, Daulton, Bartlein, Boslough, Breslawski, Fisher, Jorgeson, Scott, Koeberl, Marlon, Severinghaus, Petaev and Claeys2023).

Here, we report the results on a study of a glass fragment from a sediment sequence at the Blackville site in South Carolina, USA. The glass was found in a 15 cm interval between 175 to 190 cm with maximum concentrations at ∼183 cm below the surface. The glass was accompanied by peak concentrations of platinum and iridium (Kennett et al., Reference Kennett, Kennett, Culleton, Tortosa, Bischoff, Bunch, Daniel, Erlandson, Ferraro, Firestone, Goodyear, Israde-Alcántara, Johnson, Jordá Pardo, Kimbel, LeCompte, Lopinot, Mahaney, Moore, Moore, Ray, Stafford, Tankersley, Wittke, Wolbach and West2015), Fe- and Si-rich spherules (Bunch et al., Reference Bunch, Hermes, Moore, Kennett, Weaver, Wittke, DeCarli, Bischoff, Hillman, Howard, Kimbel, Kletetschka, Lipo, Sakai, Revay, West, Firestone and Kennett2012; Wittke et al., Reference Wittke, Weaver, Bunch, Kennett and Kennett2013), glass containing suessite and native iron (Bunch et al., Reference Bunch, Hermes, Moore, Kennett, Weaver, Wittke, DeCarli, Bischoff, Hillman, Howard, Kimbel, Kletetschka, Lipo, Sakai, Revay, West, Firestone and Kennett2012), soot/aciniform carbon (Wolbach et al., Reference Wolbach, Ballard, Mayewski, Adedeji and Bunch2018), carbon spherules (Kinzie et al., Reference Kinzie, Que, Stich, Tague, Mercer, Razink, Kenneth, DeCarli, Bunch, Wittke, Israde-Alcántara, Bischoff, Goodyear, Tankersley, Kimbel, Culleton, Erlandson, Stafford, Kloosterman, Moore, Firestone, Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, West, Kennett and Wolbach2014), and nanodiamonds (Kinzie et al., Reference Kinzie, Que, Stich, Tague, Mercer, Razink, Kenneth, DeCarli, Bunch, Wittke, Israde-Alcántara, Bischoff, Goodyear, Tankersley, Kimbel, Culleton, Erlandson, Stafford, Kloosterman, Moore, Firestone, Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, West, Kennett and Wolbach2014). The stratum was dated by Optically Stimulated Luminescence to 12,960 ± 1190 calendar years, leading Bunch et al. (Reference Bunch, Hermes, Moore, Kennett, Weaver, Wittke, DeCarli, Bischoff, Hillman, Howard, Kimbel, Kletetschka, Lipo, Sakai, Revay, West, Firestone and Kennett2012) to conclude that the stratum is too old and too deeply buried to contain anthropogenic contamination.

For our investigation, trigonal Fe2Si was isolated and studied using micro-computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, electron microprobe and X-ray single-crystal diffraction. The results are presented here.

Material and methods

Samples

The samples were collected by one of us (AW) at the Blackville site, South Carolina, USA (33.361545°N, 81.304348°W) using hand auger coring. The sediment sequence consists of aeolian and alluvial sediments, specifically variable loamy to silty red clays, extending downwards to an apparent disconformity at 190 cm below the surface. A 15-cm-thick interval from 175 to 190 cm below the surface displayed an enrichment in glass. Little to no glass was observed above or below this layer.

Micro-computed X-ray tomography

Initially, X-ray imaging was carried out using an Rx Solution NanoCT “EasyTom” with a voxel size of 13.69 μm. A 150 kV X-ray source was used with a current of 200 μA. A total of 1920 absorption radiographs were acquired over a 360° rotation. The raw data were reconstructed into two-dimensional slice images (Fig. 1) using Rx Solution Software. CT datasets were visualised and customised using Bruker’s CTAn and CTVox software.

Figure 1. Micro-CT images of the two rock fragments studied from the Blackville site. Silicate glass is in green and silicide droplets in orange. Scale bar is 1 cm.

Scanning electron microscopy

Three samples were embedded in epoxy, polished and then studied with a Zeiss EVO MA15 scanning electron microscope coupled with an Oxford UltimMax 40 energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS), operating at 15 kV accelerating potential and 700 pA nominal current in focused beam mode for EDS mapping and spectra acquisition (30 s live time). For linescan analyses, the instrument was set up at 10 kV acceleration voltage and 500 pA nominal probe current (20 s dwell time for each point). One sample was randomly selected and sputter-coated with a 30 nm thick carbon film.

Electron microprobe

Quantitative analyses on suessite and hapkeite (initially identified by scanning electron microscope) comprising a 250 μm-diameter droplet were carried out using a JEOL 8200 electron microprobe (WDS mode, 12 kV and 5 nA, focused beam). The focused electron beam was ∼150 nm in diameter. Analyses were processed using the CITZAF correction procedure. Both suessite (n = 3) and hapkeite (n = 4) were found to be homogeneous within analytical error (Table 1). The standards used were Fe metal, Ni metal, V metal, synthetic FeSi and GaP.

Table 1. Electron microprobe data (wt.% of elements) and chemical formulae for suessite (S – on the basis of 4 atoms) and trigonal Fe2Si (TH – on the basis of 3 atoms) from the Blackville site

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

A small fragment (size ∼18 × 15 × 10 μm) exhibiting an Fe2Si composition was extracted from the droplet shown in Fig. 2 under a reflected light microscope and mounted on a 5 μm diameter carbon fibre, which was, in turn, attached to a glass rod. The single-crystal X-ray study was carried out using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with a Photon III detector. Unit-cell parameters (Table 2) and intensity data were collected using graphite-monochromatised MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å); the data were then integrated and corrected for Lorentz-polarisation effects and absorption using the APEX5 software suite (Bruker, 2023).

Figure 2. X-ray element-distribution map (left) and scanning electron microscope back-scattered electron image of the investigated droplet composed of Fe-silicides. Trigonal Fe2Si and suessite are indicated.

Table 2. Crystallographic data and refinement parameters for trigonal Fe2Si

Notes: R(n/n–1)1/2[Fo2–Fo(mean)2]/ ΣFoint2

R 1 = Σ||Fo|–|Fc||/Σ|Fo|

GooF = {Σ[w(Fo2–Fc2)2]/(n–p)}1/2 where n = no. of reflections, p = no. of refined parameters

Surprisingly, the unit-cell parameters observed for the selected Fe2Si crystal indicated a trigonal symmetry, with a = 3.9782(2) and c = 5.0691(3) Å. No systematic absences were observed, in keeping with the space group P ![]() $\bar 3$m1. As trigonal Fe2Si has been previously described by several authors (e.g. Khalaff and Schubert, Reference Khalaff and Schubert1974; Heinz, Reference Heinz1977; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Tam, Xiong, Cao and Zhang2016), we decided to begin the refinement using these atom coordinates. The program SHELXL (Sheldrick, Reference G.M2008) was used for the refinement of the structure. The occupancy of all the sites was left free to vary (Fe vs. vacancy; Si vs. vacancy), but they were found to be fully occupied by the corresponding atomic species and then fixed accordingly. Neutral scattering curves for Fe and Si were taken from the International Tables for X-ray Crystallography (Ibers and Hamilton, Reference Ibers and Hamilton1974). At the last stage, with anisotropic atomic displacement parameters for all atoms and no constraints, the residual value settled at R = 0.0224 for 60 observed reflections [2σ(I) level] and 11 parameters and at R = 0.0336 for all 160 independent reflections.

$\bar 3$m1. As trigonal Fe2Si has been previously described by several authors (e.g. Khalaff and Schubert, Reference Khalaff and Schubert1974; Heinz, Reference Heinz1977; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Tam, Xiong, Cao and Zhang2016), we decided to begin the refinement using these atom coordinates. The program SHELXL (Sheldrick, Reference G.M2008) was used for the refinement of the structure. The occupancy of all the sites was left free to vary (Fe vs. vacancy; Si vs. vacancy), but they were found to be fully occupied by the corresponding atomic species and then fixed accordingly. Neutral scattering curves for Fe and Si were taken from the International Tables for X-ray Crystallography (Ibers and Hamilton, Reference Ibers and Hamilton1974). At the last stage, with anisotropic atomic displacement parameters for all atoms and no constraints, the residual value settled at R = 0.0224 for 60 observed reflections [2σ(I) level] and 11 parameters and at R = 0.0336 for all 160 independent reflections.

Experimental details and R indices are given in Table 2. Fractional atomic coordinates and equivalent displacement parameters are reported in Table 3 (anisotropic displacement parameters can be found in the accompanying crystallographic information file). Bond distances are given in Table 4. The cif has been deposited and is available as Supplementary material (see below).

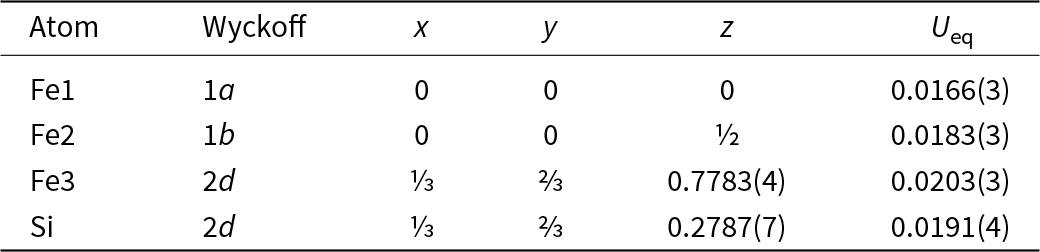

Table 3. Atoms, Wyckoff letter, fractional atom coordinates (Å) and equivalent atomic displacement parameters for trigonal Fe2Si

Table 4. Selected bond distances (Å) for trigonal Fe2Si

Results and discussion

Crystal structure and nomenclature remarks

Hapkeite was originally defined with the formula Fe2Si, cubic Pm ![]() $\bar 3$m structure (a = 2.831 Å) and Z = ⅔ (Anand et al., Reference Anand, Taylor, Nazarov, Shu, Mao and Hemley2004). In the structure, there are two positions with the same multiplicity: 1a (0,0,0) and 1b (½,½,½). The 1a position is occupied by Fe only, whereas the 1b position is occupied by ∼⅔Si and ∼⅓Fe. Given the preference to not give non-integer Z values and taking into account the rule of the dominance of a cation at a structural site, the formula had to be written either as Fe(Si,Fe) or FeSi with Z = 1. Because of this, hapkeite should be revisited and should be considered as a second polymorph of FeSi after naquite (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Bai, Li, Xiong, Yang, Ma and Rong2012). On the contrary, the trigonal, ordered variant of Fe2Si described here consists of four positions: 1a (0,0,0; fully occupied by Fe), 1b (0,0,½; fully occupied by Fe), 2d (⅓,⅔,z; fully occupied by Fe), and 2d (⅓,⅔,z; fully occupied by Si), with Z = 2. In this case, the formula must be written as Fe2Si.

$\bar 3$m structure (a = 2.831 Å) and Z = ⅔ (Anand et al., Reference Anand, Taylor, Nazarov, Shu, Mao and Hemley2004). In the structure, there are two positions with the same multiplicity: 1a (0,0,0) and 1b (½,½,½). The 1a position is occupied by Fe only, whereas the 1b position is occupied by ∼⅔Si and ∼⅓Fe. Given the preference to not give non-integer Z values and taking into account the rule of the dominance of a cation at a structural site, the formula had to be written either as Fe(Si,Fe) or FeSi with Z = 1. Because of this, hapkeite should be revisited and should be considered as a second polymorph of FeSi after naquite (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Bai, Li, Xiong, Yang, Ma and Rong2012). On the contrary, the trigonal, ordered variant of Fe2Si described here consists of four positions: 1a (0,0,0; fully occupied by Fe), 1b (0,0,½; fully occupied by Fe), 2d (⅓,⅔,z; fully occupied by Fe), and 2d (⅓,⅔,z; fully occupied by Si), with Z = 2. In this case, the formula must be written as Fe2Si.

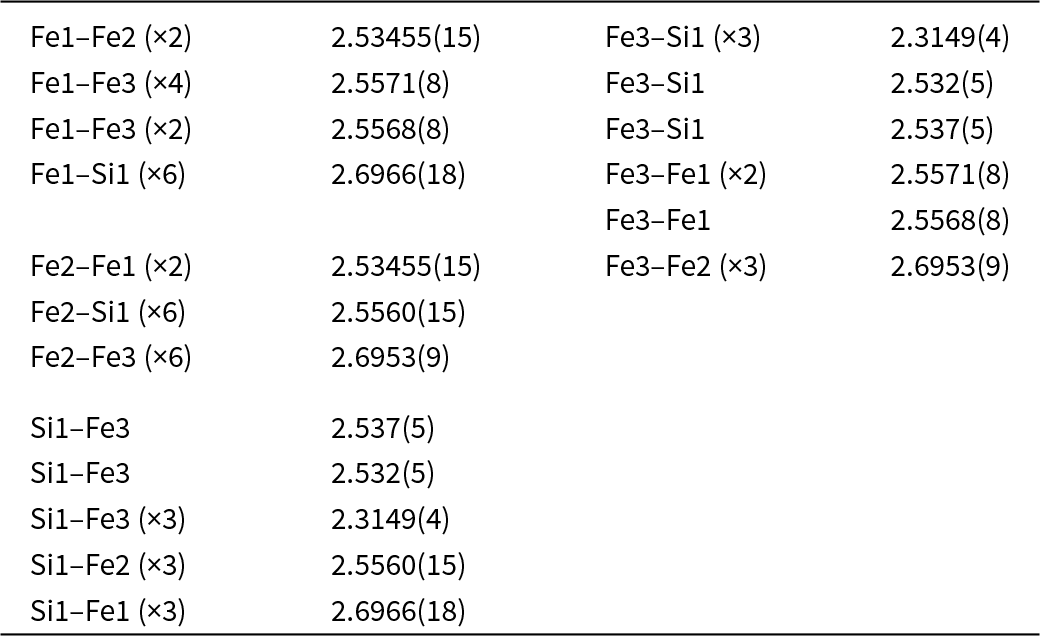

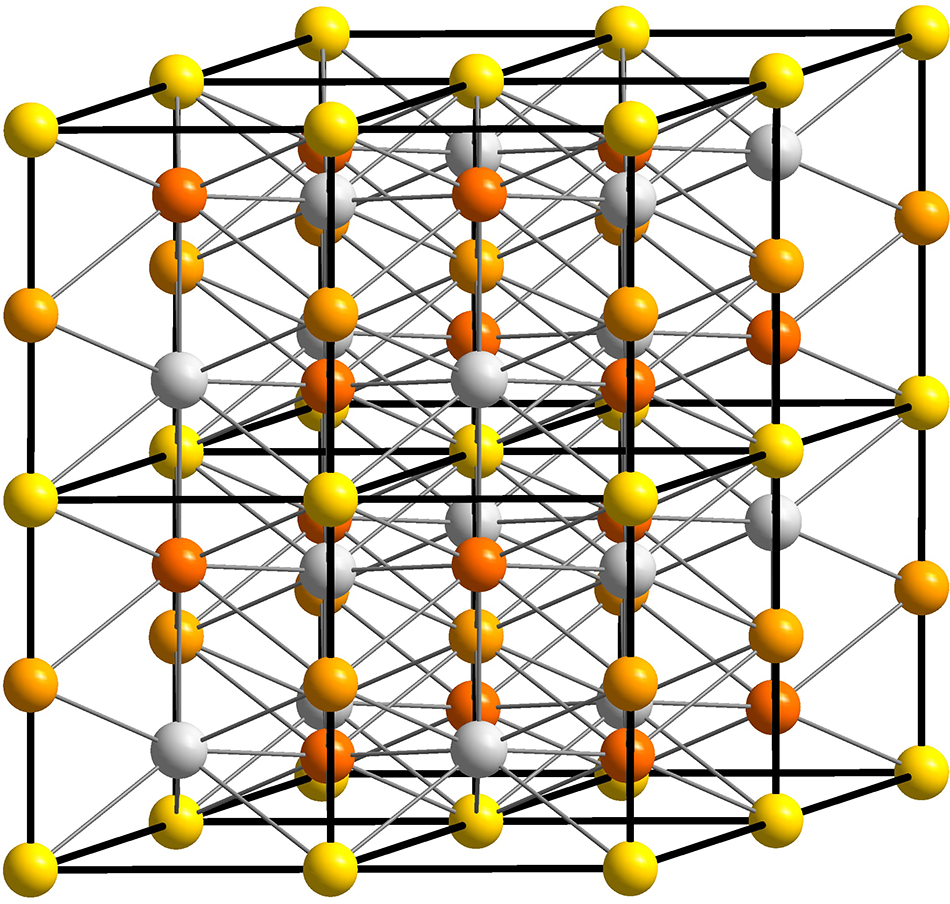

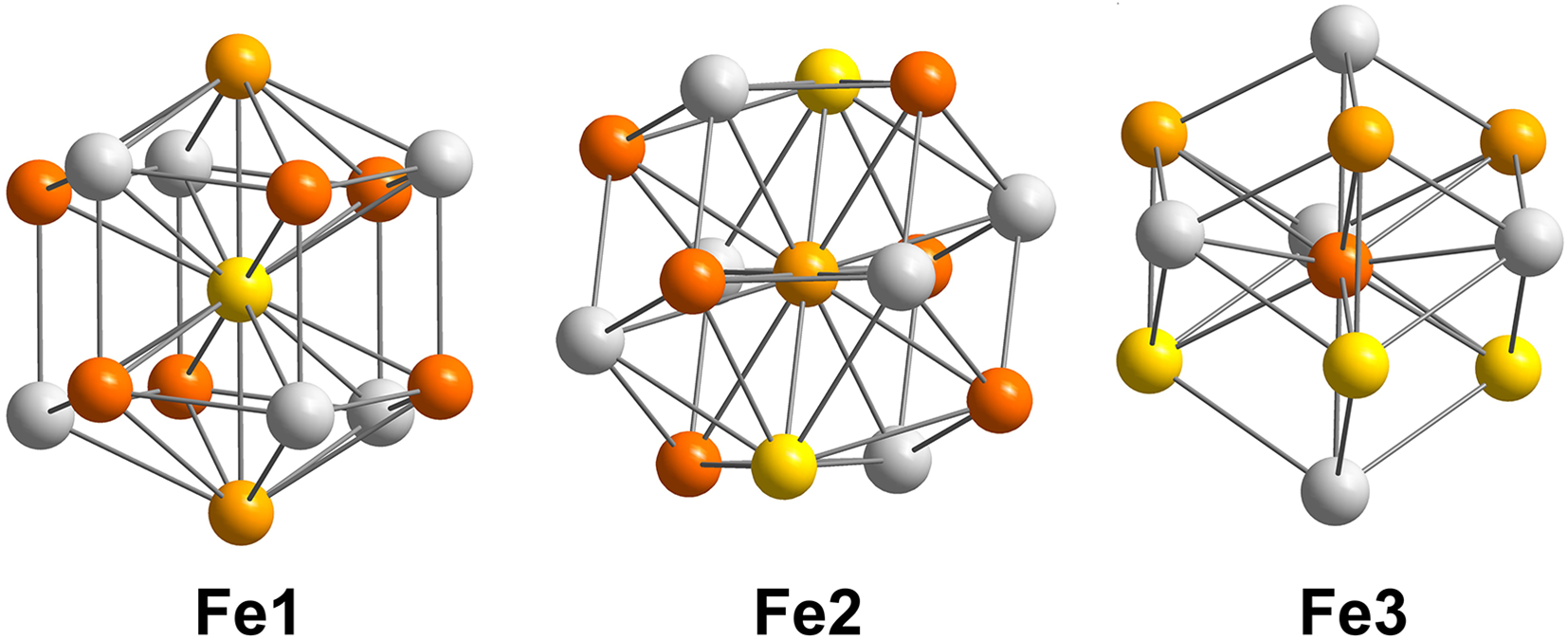

In addition to these nomenclature considerations, hapkeite and the compound described here (both with the Fe2Si formula) cannot be considered polytypes because the crystal-chemical environment of Fe atoms is different in the two phases. In cubic Fe2Si (hapkeite), Fe is surrounded by 8 (Si,Fe) atoms, whereas in trigonal Fe2Si (Fig. 3), Fe atoms exhibit different coordination spheres (Fig. 4 and Table 4). In detail, the latter is characterised by three inequivalent Fe sites. In the first Fe site, Fe is bonded in a 14-coordinate geometry to eight equivalent Fe and six equivalent Si atoms. All Fe–Fe bond lengths are in the range 2.53–2.56 Å, and the Fe–Si bond distances are close to 2.70 Å. The second Fe site shows a coordination environment very close to that observed for Fe1 (Table 4). In the third Fe site, Fe is bonded in an 11-coordinate geometry to six equivalent Fe and five equivalent Si atoms. Notably, Fe3 shows three short bond distances with Si (∼2.31 A). Si is bonded in a distorted body-centred cubic geometry to eleven Fe atoms.

Figure 3. The crystal structure of trigonal Fe2Si down the [100] (perspective view). Yellow, light orange, orange and white spheres refer to Fe1, Fe2, Fe3 and Si atoms.

Figure 4. Crystal-chemical environments of Fe atoms in the crystal structure of trigonal Fe2Si. Colours as in Fig. 3.

Interestingly, Errandonea et al. (Reference Errandonea, Santamaria-Perez, Vegas, Nuss, Jansen and Munoz2008) performed ab initio total energy calculations for both polymorphs (cubic and trigonal) of Fe2Si and found that at zero and low pressure, the most stable variant for Fe2Si is the trigonal structure because the cubic hapkeite structure is higher in energy by more than 200 meV pfu (particle flux unit).

Possible origin for silicides at the Blackville site

The discovery of trigonal Fe2Si and associated suessite in glass from the Blackville site suggests formation under highly reducing conditions related to unusual terrestrial conditions. Although the precise formation mechanism is unclear, past research suggests an as-yet-unidentified impact or a lightning strike event. Indeed, very similar silicide assemblages have been recently reported in fulgurites (e.g. Bindi et al., Reference Bindi, Feng and Pasek2023; Abbatiello et al., Reference Abbatiello, Bindi and Pasek2025; Morana et al., Reference Morana, Pasek, Catelani and Bindi2025). It is noteworthy that Essene and Fischer (Reference Essene and Fisher1986) observed that Fe–Si-bearing glass was associated with charred tree roots, suggesting that carbon may have assisted with the production of the highly reducing environment required for Fe–Si phase formation. However, though the sediment at the Blackville site contains carbon, it is probably insufficient by itself to drive the reduction process but still may have contributed to the formation of silicides. So, the origin of the Blackville silicides remains enigmatic and requires further research.

Conclusions

Given the structural differences with hapkeite, trigonal Fe2Si would normally be considered a new mineral species. However, after thorough analysis and consideration of the circumstances surrounding the formation of this mineral, we have opted not to propose this compound as a new mineral species to the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) at the present time. One of the key factors in this decision is the possibility that anthropogenic activity may have played a role in the formation of this mineral, although that possibility seems unlikely given the depth of burial (183 cm) where the samples were collected. Further investigation is needed to understand the mineral origin better, and any future proposals will depend on a clearer delineation between natural and anthropogenic contributions to its formation. Until then, this discovery remains a significant observation in the field of Fe-silicides.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.10130

Acknowledgements

The paper benefited by the official reviews made by Peter Leverett and two anonymous reviewers. Associate Editor Ian Graham is thanked for his efficient handling of the manuscript. SC-XRD and EMPA data were collected, respectively, at CRIST (Centro di Servizi di Cristallografia Strutturale) and LaMA (Laboratorio di MicroAnalisi) of the Università degli Studi di Firenze, Italy.

Funding statement

This study was also conducted within the Space It Up project funded by the Italian Space Agency, ASI, and the Ministry of University and Research, MUR, under contract n. 2024-5-E.0-CUP n. I53D24000060005. GK was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (Grant 23-06075S) and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (Grant LUAUS25082).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.