Introduction

North America hosts numerous diamond deposits (Fig. 1), with the most productive being in the northern regions of Canada. Many of these diamonds are sourced directly from kimberlites whereas others come from secondary glacial till deposits (e.g. Kjarsgaard and Levinson, Reference Kjarsgaard and Levinson2002). Though not as prolific as Canadian deposits, diamond occurrences found within the United States have yielded ∼27,000 carats to-date. About 25% of those stones have been gem quality. Although most diamonds have been ≤ 2 ct, stones range up to 41 ct (Hausel, Reference Hausel1994; Hausel, Reference Hausel1998; Worthington, Reference Worthington2007; Howard, Reference Howard, Harris and Staebler2017; Wallace Jr, Reference Wallace, Harris and Staebler2017). Notable faceted gems include the 12.40 ct faint pinkish brownish, ‘M’ colour grade ‘Uncle Sam’ diamond from Arkansas, currently on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. Another notable diamond is the 16.87 ct faint yellow, ‘L’ colour grade ‘Freedom’ diamond from Colorado (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Kimberlite, lamproite and reported diamond occurrences in North America overlain with the maximum extent of the Laurentide ice-sheet, the Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane, Archean terranes and the eastern edge of the subducting Farallon slab at 100 and 90 Myr ago (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1988; Hausel Reference Hausel1998; Krajick, Reference Krajick2011; Kjarsgaard et al., Reference Kjarsgaard, Heaman, Sarkar and Pearson2017; Czas et al., Reference Czas, Stachel, Pearson, Stern and Read2018, Reference Czas, Pearson, Stachel, Kjarsgaard and Read2020). Most diamond occurrences in the USA appear to be spatially coincident with the extent of the Laurentide ice sheet during the last glacial maximum (Pielou, Reference Pielou1991; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Stokes and Batchelor2022).

Figure 2. Famous diamonds found in the USA include the (a) 16.87 ct. Colorado ‘Freedom’; (b) 4.25 ct. Arkansas ‘Kahn Canary’ set within a design by Henry Dunay and famously worn by Hillary Clinton; (c) 12.40 ct. Arkansas ‘Uncle Sam’; and (d) a suite of six diamonds mined from the Prairie Creek lamproite by one of the most prolific local Arkansas diamond miners, James Archer and set within a brooch commissioned by Sue John Anthony. Photo credits to Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History for photographs of the Colorado Freedom and Uncle Sam, Glenn Worthington for the Kahn Canary and Nathan Renfro for the Sue John Anthony jewellery piece.

Diamonds from Arkansas are not a strong economic resource, but they drive significant tourism at the Crater of Diamonds State Park (Bassoo and Befus, Reference Bassoo and Befus2020). These diamonds are also important scientific resources, because they are ancient minerals from the mantle that are useful to infer mantle conditions and tectonic processes operating beneath the southern edge of the North American Craton. In the scientific literature Arkansas diamonds are also known as Prairie Creek diamonds, referring to the Prairie Creek lamproite. No comprehensive studies exist that characterise the physical and spectroscopic characteristics of a large collection of Arkansas diamonds. Here, we review published isotopic and elemental compositions of these diamonds as well as their mineral inclusions. We then supplement this information with new data on the crystal morphology, infrared spectroscopy, elastic thermobarometry, optical cathodoluminescence, visible-near infrared absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy of 155 diamonds from the Prairie Creek lamproite in Arkansas, which inform us of formation and deformation processes. We present new evidence indicating that diamonds from Arkansas formed in highly heterogeneous lithospheric mantle and subsequently underwent internal deformation. These processes may be characteristic of primary diamond occurrences along cratonic margins, as opposed to the more common kimberlite occurrences within cratons.

Geological setting

Diamonds from the USA are found in placers and in Neoproterozoic to mid-Cretaceous-aged kimberlites and lamproites. Placer diamonds occur in the USA within Eocene to recent conglomerates and glacial moraines coincident with the proposed maximum extent of the Laurentide glacial ice-sheet (Hobbs, Reference Hobbs1899; Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Gurney and Kirkley1992; Hausel, Reference Hausel1994, Reference Hausel1998, Hausel and Bond, Reference Hausel and Bond1994). Whereas the majority of global diamond-bearing igneous rocks typically penetrate through the thick, cold roots beneath ancient cratons, diamonds found in Arkansas lamproites occur in a distinct tectonic setting along the edge of the North American lithosphere. Recent geophysical studies indicate the lithosphere thins significantly to <150 km towards the south and southwest into the United States (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Dueker, Schmandt and Yuan2013; Schaeffer and Lebedev, Reference Schaeffer and Lebedev2014; Kjarsgaard et al., Reference Kjarsgaard, Heaman, Sarkar and Pearson2017). This is an atypical tectonic environment for diamond formation. Typically, old and thick cratons overlie Archean lithospheric roots that extend to 150 to 200 km in depth. Igneous rocks within these cratonic roots are depleted in Al, Ca, Fe, K, Th and U and are therefore relatively buoyant and cooler than the convecting mantle at similar depths (Jordan, Reference Jordan1978; Pollack and Chapman, Reference Pollack and Chapman1977). These conditions raise the graphite to diamond phase transition to shallower depths, making the cratonic root favourable for diamond formation and storage (Stachel and Harris, Reference Stachel and Harris2008). Outside of this narrow diamond stability field, we do not expect diamonds to form and/or reside for very long periods before turning to graphite. Consequently, diamondiferous kimberlites are typically found inside the oldest and thickest portions of cratons, where they transect the cratonic root and entrain diamonds (Smith, Reference Smith1983; Zurevinski et al., Reference Zurevinski, Heaman and Creaser2011; Stachel and Harris, Reference Stachel and Harris2008). Kimberlites and lamproites that intrude along the margin of cratons should be devoid of diamonds because they do not transect this root zone (Kjarsgaard et al., Reference Kjarsgaard, de Wit, Heaman, Pearson, Stiefenhofer, Janusczcak and Shirey2022). Notable exceptions include the Buffalo Head Hills kimberlites in Canada, the Pimenta Bueno and Juína kimberlites in Brazil, and the Argyle and Ellendale lamproites in Australia (Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Hall, Sheraton, Smith, Sun and Drew1989; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Hillier, Hood, Pryde and Skelton1999; Bulanova et al., Reference Bulanova, Smith, Walter, Blundy, Gobbo and Kohn2008; Luguet et al., Reference Luguet, Jaques, Pearson, Smith, Bulanova, Roffey, Rayner and Lorand2009; Smit et al., Reference Smit, Shirey, Richardson, le Roex and Gurney2010; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018; Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Luguet, Smith, Pearson, Yaxley and Kobussen2018; Cabral-Neto et al., Reference Cabral-Neto, Ruberti, Pearson, Luo, Azzone, Silveira and Almeida2024). Diamondiferous lamproites in Arkansas are additional examples of primary diamondiferous rocks which occur along craton margins. These lamproites occur above the extent of the subducting Farallon slab, within a tentative mid-Cretaceous to Neoproterozoic corridor that extends from Somerset Island in Arctic Canada through central Saskatchewan and Alberta to Prairie Creek in Arkansas (Fig. 1) (Sharp, Reference Sharp1974; Heaman et al., Reference Heaman, Kjarsgaard and Creaser2003; Reference Heaman, Kjarsgaard and Creaser2004; Currie and Beaumont, Reference Currie and Beaumont2011; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014; Kjarsgaard et al. Reference Kjarsgaard, Heaman, Sarkar and Pearson2017).

Primary diamonds from Arkansas

In 1842 an unexpected outcrop of ‘peridotite rock’ was reported by geologist W.B. Powell crosscutting Lower Cretaceous sedimentary units in Southwestern Arkansas near the confluence of Prairie Creek and the Little Missouri River (Miser and Ross, Reference Miser and Ross1923). Diamonds were occasionally reported in Arkansas subsequently during the late 1800s, but the discovery locations were kept secret. The ‘Prairie Creek peridotite’, now known to be a lamproite, was examined by geologist J.C. Branner in the late 1880s but no diamonds were found (Branner and Brackett, Reference Branner and Brackett1889). Diamonds were first formally discovered in 1906 at this locality when local farmer J.W. Huddleston found 2 stones, a ∼3.0 ct white and a ∼1.5 ct yellow, although accounts of this discovery vary (Henderson, Reference Henderson2002). Announcement of the discovery produced a speculative mining rush to the Prairie Creek area and led to the first scientific descriptions of Arkansas diamonds (e.g. Kunz and Washington, Reference Kunz and Washington1908). Decades of ensuing exploration and financially unsuccessful mining ventures at the Prairie Creek lamproite and in the surrounding area revealed additional lamproites, including the Twin Knobs #1, Twin Knobs #2, Black Lick, American and American North pipes. Each of these lamproites contain diamonds but they have not been economic to mine because of low diamond grades and sizes. The Prairie Creek lamproite had the highest diamond grade, but mining operations there also never returned a profit. In 1972 the State of Arkansas purchased the land the Prairie Creek lamproite occurs within and developed the Crater of Diamonds State Park. The state park is the only place in the world where the public can prospect a primary diamond deposit. Tourist and local artisanal miners recover ∼600 stones per year, but only 3.5% are larger than 1 ct. The Prairie Creek lamproite which hosts these diamonds is located tectonically between the Cenozoic Gulf Coastal Plain and the Palaeozoic Ouachita Mountains (Dunn, Reference Dunn2003). They intrude the Upper Early Cretaceous Trinity Group of sediments and are unconformably overlain by the Lower Late Cretaceous Tokio Formation. Such stratigraphic constraints are confirmed by phlogopite 40Ar/39Ar radiometric ages of 99±2 Ma and 108±3 Ma, which indicate Cretaceous emplacement and crystallisation of the lamproite (Zartman, Reference Zartman1977; Gogineni et al., Reference Gogineni, Melton and Giardini1978). Furthermore, radiogenic Sr (0.7069–0.771) suggest derivation from the sub-continental lithospheric mantle (SCLM) (Alibert and Albarède, Reference Alibert and Albarède1988; Heaman, Reference Heaman1989; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Shirey and Bergman1995; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014).

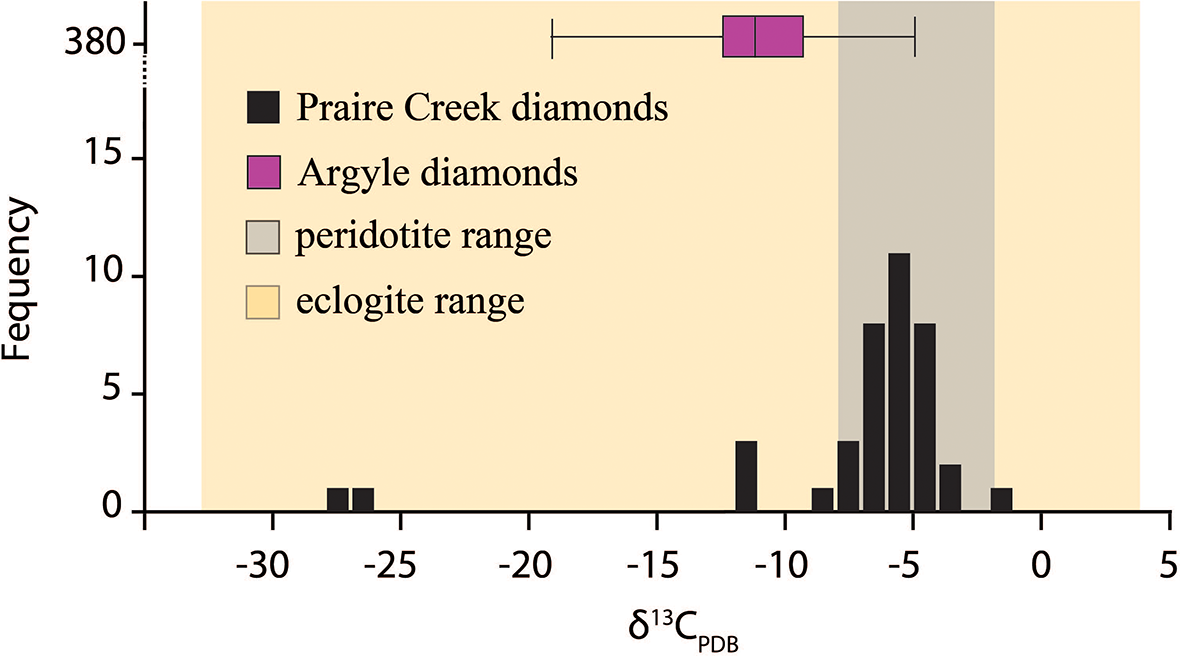

The reported lamproites have a variety of hypabyssal to subaerially-deposited facies, including magmatic, bedded volcanic breccias and tuffs and epiclastic deposits (Scott-Smith and Skinner, Reference B.H and E.M.W1984; Walker, Reference Walker1991). All units are olivine lamproite and generally preserve an assemblage of olivine (Fo92), clinopyroxene, poikilitic phlogopite, priderite, K-richterite, garnet, diamond, chromite and ilmenite. Much of the groundmass in all facies is thoroughly serpentinised. All facies contain abundant crustal xenoliths, as well as less common mantle eclogite, harzburgite, lherzolite and websterite xenoliths. Most diamonds are small (<2.0 mm); they have dodecahedral habits, but rare octahedral, tetrahexahedral and macle crystal habits are also found. The crystals can be colourless, light brown, or yellow. Diamonds commonly display fine hillocks and low-relief surfaces indicating intense or prolonged resorption (Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, McCandless and Dummett1987; McCandless, Reference McCandless1991). Isotopically, macro-diamonds from the Prairie Creek lamproite have mean δ13C ∼ –6.5±2.8‰ which suggests formation from fluids derived from peridotitic rocks (McCandless et al., Reference McCallum, Huntley, Falk and Otter1991; Cartigny, Reference Cartigny2005). Microdiamonds from Prairie Creek lamproite with δ13C values of –25.2 and –26.1‰ may indicate diamond crystallisation from websteritic or eclogitic rocks (Deines and Harris, Reference Deines and Harris2004; Ickert et al., Reference Ickert, Stachel, Stern and Harris2013; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Cartigny, Chacko and Pearson2022b).

Materials and methods

Diamonds unearthed within the United States are either in inaccessible personal collections or are very expensive to acquire, even for stones with little value in the jewellery trade. Our collection of 155 diamonds from the Prairie Creek lamproite includes seven diamonds that we found by personally mining on-site at the state park, 16 diamonds purchased from diamond dealer K. Glasser (Diamond RoughTM) and 132 lent to us for the investigation by local Arkansas miners/collectors, including Troy Savage, Glenn Worthington, Scott Kreykes, Sam Johnson, Don Roeder, Dennis Dunn and Tom Paradise.

The morphology and optical character of the diamonds was examined using a Zeiss AXIO petrographic microscope. These petrographic observations were used to characterise crystal shape, dissolution textures and abrasion. Additional visual inspection revealed diamond colour, colour distribution and presence/absence of mineral inclusions.

Infrared absorbance (IR) of the diamonds measured at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) was accomplished using a ThermoFisher Scientific Nicolet iN10 FTIR spectrometer. Analyses were performed across 675–4000 cm–1 in cooled transmission mode using a 200 × 200 µm aperture size, 64 to 128 scans and a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1. Some collectors preferred that their diamonds remain in their possession. For these 23 stones we used a transportable ThermoFisher Scientific IS5 FTIR. These analyses were performed across 675–4000 cm–1 at room temperature and a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1. For all samples nitrogen concentrations and aggregation state were calculated from individual spectra by applying the Beer-Lambert law and absorption values of the nitrogen bands at 1365, 1284 and 1175 cm–1, using the least-squares fitting approach (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Kiflawi, Luyten, Vantendeloo and Woods1995; Howell et al., Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012a; Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012b). Individual total N concentration (at.ppm) vs. %NB (degree of nitrogen aggregation from A to B centres) ratios were used to calculate mean residence temperatures using the kinetics of the nitrogen A-B centre aggregation reaction (e.g. Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Jaques and Ridd1990, Reference Taylor, Canil and Milledge1996). Infrared spectra were also used to characterise diamond optical defects following Shigley and Breeding (Reference Shigley and Breeding2013).

Optical cathodoluminescence of diamonds was observed using a Nikon LV UEPI microscope equipped with a low vacuum Reliotron III cathodoluminescence system operated at 7.5–9 kV and 0.3–0.5 amps. For each diamond the luminescence colour response, or lack thereof, was documented during cathodoluminescence. The visible-near-infrared (vis-NIR) absorption spectra of diamonds were acquired by a GIA vis-NIR system at 77 K. Photoluminescence spectra of diamonds were acquired using a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope at 100% laser power, 5–10× magnification, a ∼2 µm spot size, a full-resolution grating and with 457, 514, 633 and 830 nm laser excitations. The samples were kept at ∼77 K during analyses.

Raman spectra of diamond-hosted inclusions were collected at Baylor University using a ThermoFisher Scientific DXR Raman microscope equipped with a 532 nm laser operating at 8 mW, a ∼2 µm spot and a high-resolution grating (1800 lines mm–1). Petrographic inclusion identification was confirmed with Raman spectra by matching peak positions and heights of the inclusions’ spectra with those in the RRUFF spectral database (Lafuente et al., Reference Lafuente, Downs, Yang and Stone2016). The Raman spectra of diamond-hosted inclusions were also used to calculate their entrapment pressures using elastic thermobarometry following Angel et al. (Reference Angel, Alvaro and Nestola2017) and the thermobarometry calculator provided by Cisneros and Befus (Reference Cisneros and Befus2020). Briefly, the shape and position of Raman spectra are a consequence of the mineral’s crystal lattice environment. The positions of Raman bands, or peaks, in the spectra of a mineral are also proportional to the residual pressure preserved within the inclusion. Variations in residual pressure preserved in fully entrapped or liberated inclusions will cause a ‘peak shift’ to higher or lower wavenumbers (Izraeli et al., Reference Izraeli, Harris and Navon1999). Such peak shifts have been calibrated to calculate residual pressures in mantle minerals (McSkimin and Andreatch, Reference McSkimin and Andreatch1972; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Mernagh and Jaques1990; Izraeli et al., Reference Izraeli, Harris and Navon1999; Kohn, Reference Kohn2014). As a diamond is transported to the surface, the reduced pressure and temperature conditions cause inclusions to change volume and may impart an elastic strain against the rigid diamond. The rigid covalent bonding in diamond accounts for its extreme hardness and high incompressibility with a bulk modulus of 440 GPa at 300 K (Oganov et al., Reference Oganov, Hemley, Hazen and Jones2013). Diamond will therefore have a negligible volume change, making it a very rigid host and excellent recorder of entrapment pressures. Entrapment pressure is calculated from the measured residual pressure using an elastic model that accounts for the thermal expansivity and compressibility of diamond host and inclusion (e.g. Izraeli et al., Reference Izraeli, Harris and Navon1999; Angel et al., Reference Angel, Alvaro and Nestola2017).

We analysed forsterite and coesite inclusions in colourless diamond interiors, far from surface cracks. Peak shifts of entrapped inclusions were measured against the Raman spectra of the reference standard San Carlos olivine, ∼Fo90 (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Brown, Slutsky and Zaug1997). We also assume that the reference peak positions of synthetic coesite are 521 cm–1, 466 cm–1, 427 cm–1 and 355 cm–1 (Hemley Reference Hemley, Manghnani and Syono1984; Sobolev et al., Reference Sobolev, Fursenko, Goryainov, Shu, Hemley, Mao and Boyd2000). We recognise a more precise residual pressure might be estimated by comparing to the measured peak position of a liberated coesite inclusion, but sample destruction was not possible for diamonds loaned for this work. The resulting uncertainty in the calculated inclusion pressures has a 1σ standard error of ∼0.6 GPa, which is controlled by the 1 cm–1 resolution of the Raman spectrometer. We acknowledge that diamond hosts may also have been plastically deformed, which can manifest as homogenous or banded pink-to-brown body colours and/or deformation ‘strain’ lamellae. However, we did not acquire inclusion spectra from diamonds that exhibit these deformation traits, from locations near fractures, or close to the edge of the diamond surface. The selected inclusions were cubo-octahedral in shape. (e.g. Eaton-Magaña et al., Reference Eaton-Magaña, Ardon, Smit, Breeding and Shigley2018).

Results

Morphology and inclusions

Prairie Creek lamproite diamonds from Arkansas used in this investigation range in mass from ≤0.1 to 8.66 cts (mean 0.45±1.1 cts). Collectively, these diamonds were of colourless (59%), brown (30%), or yellow (11%) body colours (Fig. 3). Many of these diamonds are fragments and their original morphology is unknown (30%). The remaining have dodecahedral to flattened dodecahedral (61%), combination (10%) and octahedral (3%) habits (Table 1). Approximately 20% of all diamonds preserve deformation lamellae which penetrate the crystal. A subset of 4% of diamonds from Arkansas are colourless, strongly resorbed, relatively larger and irregular to flattened in habit. Hillocks and terraces on crystal surfaces are common (Fig. 4). Other dissolution features include flat-bottomed dissolution pits such as trigons and trapezoids, which account for 21% of diamonds examined. Diamonds from Arkansas also preserve flat-bottomed hexagonal dissolution pits accounting for 5% of the population. Point bottom dissolution features were observed in one diamond. A quarter of the diamonds have frosted surfaces with corrosion sculptures or have visible microdisc swarms (9%). Diamonds from Arkansas have large cavities and minor edge abrasion (24%). Mineral inclusions were identified with Raman spectra. Inclusions occur in 7% of Arkansas diamonds and are in order of decreasing abundance; diopside, rutile, magnetite, forsterite and coesite. Epigenetic graphite and grey to black with metallic lustre sulfide inclusions also occur. However, no silicate inclusions were observed in the colourless, strongly resorbed, relatively larger and irregular to flattened in habit sub-population of diamonds.

Figure 3. Selected diamonds from (a) the Prairie Creek lamproite, Arkansas, including (b) large colourless Type IIa varieties.

Figure 4. Surface textures and inclusions typical of diamonds from Arkansas.

Table 1. Summary of physical, infrared, and luminescence characteristics of Arkansas diamonds

1 Notes: 2σ – 64 ppm, 22σ – 4%, 3assuming an eruption age of 102 Ma (Zartman, Reference Zartman1977; Gogineni et al., Reference Gogineni, Melton and Giardini1978) and residence time of 3.2 Ga for the Prairie Creek lamproite. Nitrogen concentration was calculated from individual spectra by applying the Beer-Lambert law and absorption values of nitrogen bands at 1365, 1284 and 1175 cm-1, using the least-squares fitting approach combined with a basic linear correction in the DiaMap excel spreadsheet (e.g., Howell et al., Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012a, Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012b). Italicised rows reflect oversaturated and therefore minimum estimates. 4IaB minimum diamond temperatures assuming a 99% B aggregation state. Inclusions were identified by comparing Raman spectra with known representatives in the Ruff Database (LaFuente et al., Reference Lafuente, Downs, Yang and Stone2016) and supplemented with morphology, colour, texture, and other optical properties

Cathodoluminescence

We applied optical cathodoluminescence to a group of 87 Arkansas diamonds. These diamonds produced cathodoluminescent colours of green-blue, green and blue (53%, 24% and 15%, respectively). The remaining 8% of the Arkansas diamonds tested are inert (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Cathodoluminescence colours and proportions observed in a subset of 87 Arkansas diamonds.

Photoluminescence and visible-near infrared absorption

Photoluminescence (PL) spectral peak positions of diamonds are associated with nitrogen content and aggregation state as well as various atomic-level structural defects, including interstitial carbon atoms, carbon vacancies, nitrogen impurities, nickel impurities, radiation damage and plastic deformation (Fig. 6, Table 2). Complex nitrogen defects are pervasive in the photoluminescence spectra of all diamonds which are dominated by H4 (four substitutional nitrogen atoms surrounding two vacancies) and H3 (two substitutional nitrogen atoms separated by a vacancy) defects. Most diamonds have H3, NV– (nitrogen-vacancy defect with negative charge) and NV0 (nitrogen-vacancy with neutral charge state) defects. Nickel-related defects occur in almost half the diamond population. No more than 40% of diamonds preserve defects commonly associated with exposure to natural sources of radiation, with 38% having detectable GR1 740.9 and 744.4 nm (vacancy with neutral charge state) and 23% having 488.9 nm (carbon/nitrogen-related interstitial) defects. More than 45% of diamonds have PL peaks related to defects caused by plastic deformation, including peaks at 490.7 nm and 576 nm. About 14% of Arkansas diamonds have Cape spectrum features and these stones never have detectable H3 defects (Table 3). More than 70% of Arkansas diamonds have featureless visible spectra (Fig. 6). Only two Arkansas diamonds have a 550 nm absorption band.

Figure 6. Representative photoluminescence (PL) and visible-near infrared (vis-NIR) spectra.

Table 2. Percentage of Arkansas diamonds with emission peaks detected by photoluminescence spectroscopy

Notes: N – Nitrogen, C – Carbon, V0 – neutral vacancy, V– – negative vacancy.

Table 3. Percentage of Arkansas diamonds with select visible – near infrared spectral emission features

Notes: N – Nitrogen, C – Carbon, V0 – neutral vacancy, V– – negative vacancy.

Infrared spectroscopy

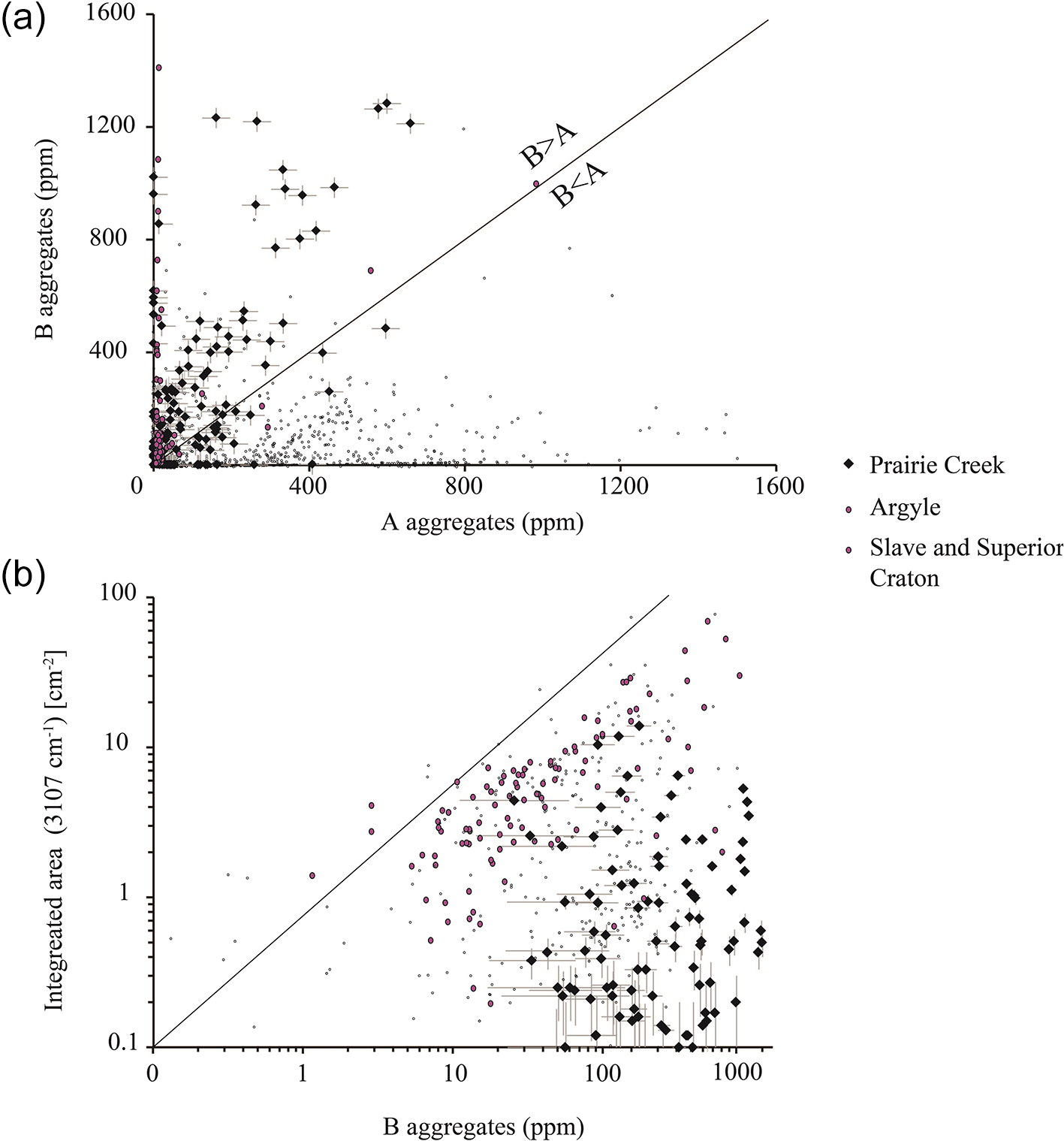

The nitrogen concentration in diamonds from Arkansas ranges between trace (<5 at.ppm ∼ nominally Type IIa) and 1880 at.ppm, with a mean of 344 at.ppm (Table 1). As a whole, ∼53% of the diamonds are Type IaAB with fewer Type IaA (20%), Type IaB stones (12%) and Type Ib stones (2%). Type IIa diamonds account for 12% of the diamond population. Of these Type IIa diamonds, 4% (n = 6) are larger (>0.7 cts), colourless, strongly resorbed and irregular. Infrared spectroscopy can be used to calculate the proportion of nitrogen A centres (NA, pairs of substitutional nitrogen) relative to more aggregated or complex nitrogen B centres (NB, four substitutional nitrogen surrounding a vacancy), using the absorption coefficients of NA and NB centres at 1282 cm–1and 1175 cm–1, respectively. Arkansas diamonds have a wide range of nitrogen aggregation states from weakly to strongly aggregated. The majority of the diamonds investigated have >50% NB (Fig. 7a).

Figure 7. (a) NA versus NB concentration obtained by calculation from infrared absorption spectra. Most diamonds examined for this study preserve more B aggregation and thus plot above the A=B aggregation line. (b) Integrated area of absorbance at 3107 cm–1 versus NB concentration. Note most diamonds from the USA plot below the expected upper limit for a given NB concentration of diamonds from a global database (thin line) (e.g. Melton, Reference Melton2013; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018). Diamond aggregation state could indicate exposure to elevated mantle temperatures.

More than 85% of Arkansas diamonds have a hydrogen-nitrogen-vacancy defect centre absorption at 3107 cm–1 (e.g. N3VH; Goss et al., Reference Goss, Briddon, Hill, Jones and Rayson2014). The integrated absorbance at that wavenumber ranges from below detection (<0.05 cm–2) to 13.9 cm–2 with a mean of 1.0±2.0 cm–2 (Table 1). When plotted against NB concentrations our diamonds have integrated 3107 cm–1 peak areas much lower than the proposed ‘upper limit’ of 3107 cm–1 areas (Fig. 7b), which correspond to the number of infrared-active N3VH centres (three substitutional nitrogen atoms surrounding a vacancy and a hydrogen atom). These defects are created as a by-product during NA to NB aggregation (Melton, Reference Melton2013).

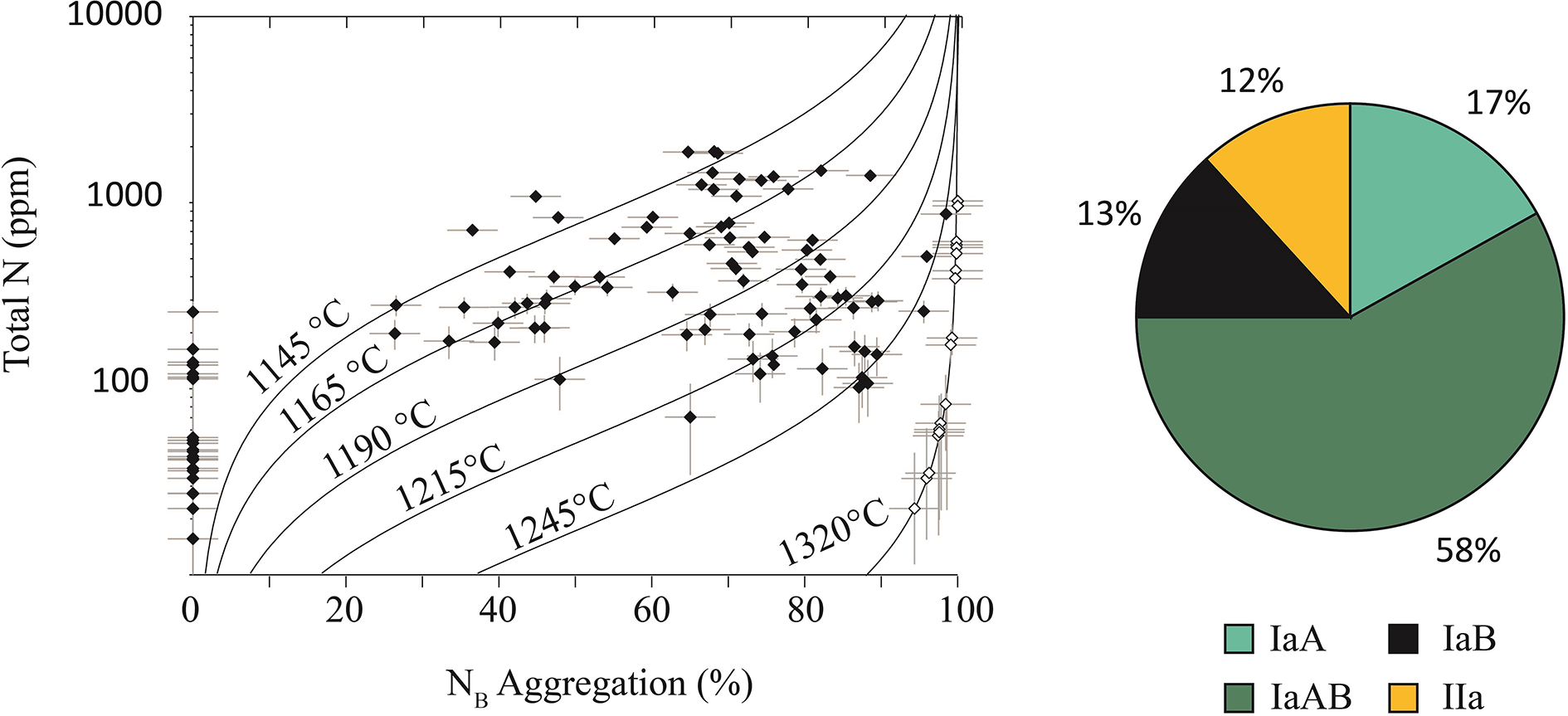

The nitrogen aggregation state of diamonds can be used to calculate the temperature of the ambient mantle during diamond residence. Nitrogen A centres convert or aggregate to more complex B centres by diffusion over geological time and at elevated temperature (e.g. Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Jaques and Ridd1990, Reference Taylor, Canil and Milledge1996). We determined mean diamond residence temperatures of 1205±63°C and a range from 1124–1321°C assuming a mean formation age of 1.4 Ga between 1.6 Ga and 1.2 Ga or analogous to the inferred age of the SCLM of the Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane (Alibert and Albarède, Reference Alibert and Albarède1988, Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Shirey and Bergman1995; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014), and therefore a calculated residence time of 1.3 Ga. Varying the formation age between 1.6 Ga and 1.2 Ga varies the residence temperature by 1–3% (e.g. Channer et al., Reference Channer, Egorov and Kaminsky2001; Bassoo et al., Reference Bassoo, Befus, Liang, Forman and Sharman2021).

Many diamonds plot along isotherms ∼1145–1190°C (Fig. 8) which is expected of cratonic diamonds (Stachel and Harris, Reference Stachel and Harris2009). However, a sub-population of diamonds plot along warmer isotherms ∼1215–1245°C. Arkansas diamonds also have a small population of strongly aggregated IaB diamonds which indicate minimum residence temperatures of ∼1320±0.414°C, assuming 99% NB aggregation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Total nitrogen (at.ppm) versus %NB with model isotherms calculated from the aggregation of diamond A aggregates to B aggregates and an assumed age of formation of 1.4 Ga [assuming a mean formation age of 1.4 Ga between 1.6 Ga and 1.2 Ga or analogous to the inferred age of the SCLM of the Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane (Alibert and Albarède, Reference Alibert and Albarède1988; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Shirey and Bergman1995; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014)] and an eruption age of 110 Ma. White diamond symbols represent IaB diamonds (100% B aggregation) and assume 99% B aggregation, which plot along a minimum ∼1290°C isotherm (Naeser and McCallum, Reference Naeser and McCallum1977; Zartman, Reference Zartman1977; Gogineni et al., Reference Gogineni, Melton and Giardini1978; Westerlund et al., Reference Westerlund, Shirey, Richardson, Carlson, Gurney and Harris2006).

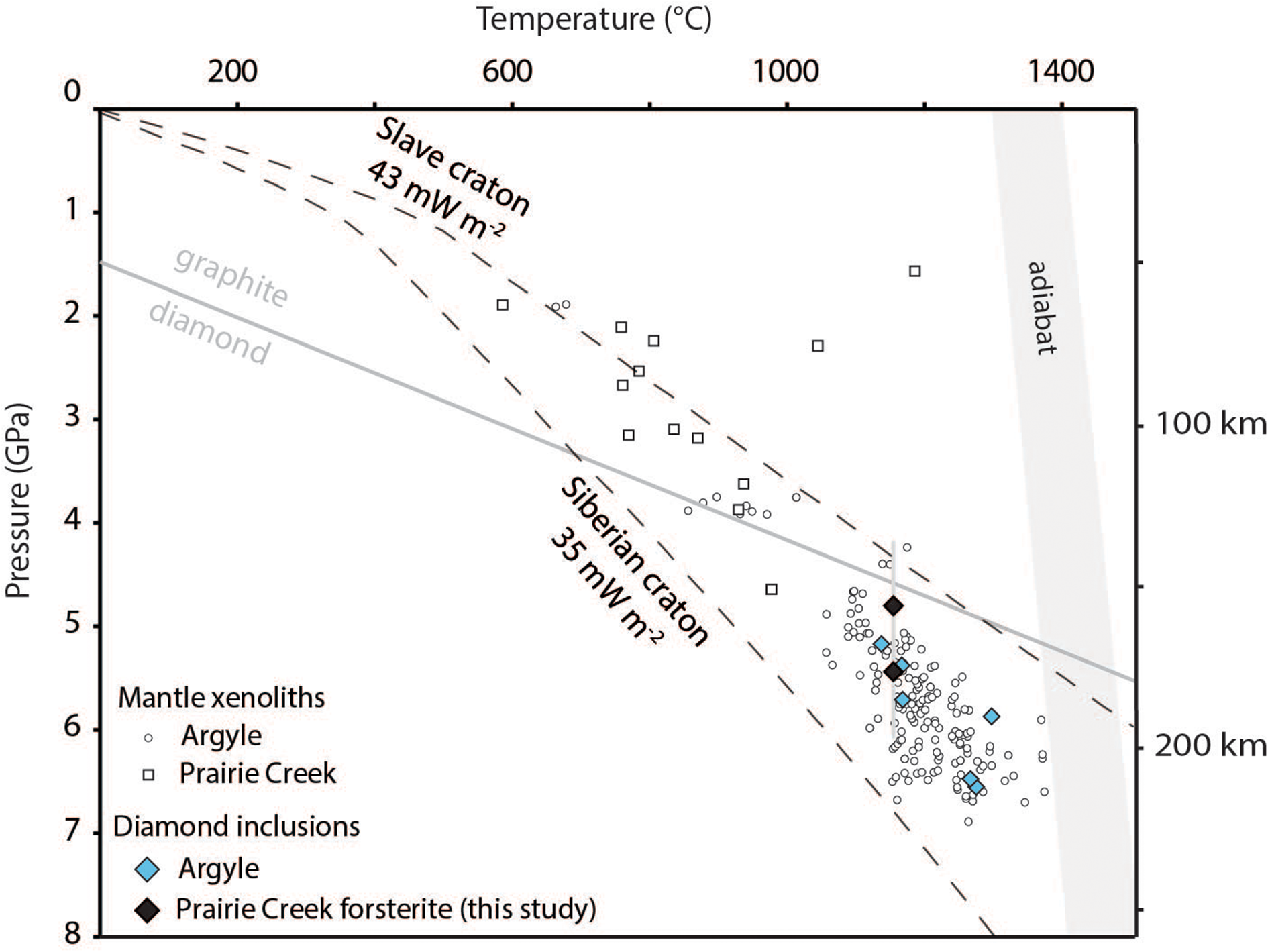

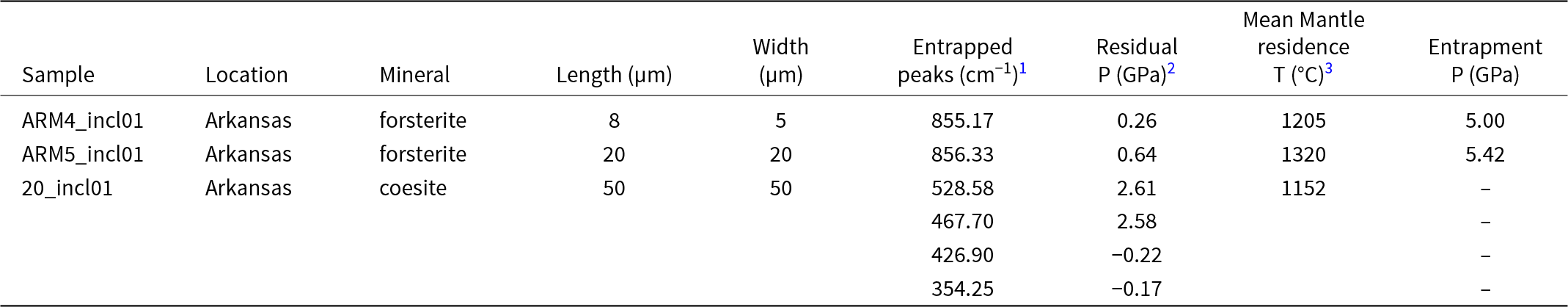

Elastic thermobarometry

Previous studies of olivine and coesite inclusions in diamond indicate preserved residual pressures that range from ∼2.8 to ∼0.9 GPa, respectively, at room temperature. These residual pressures indicate inclusion entrapment pressures at depth from ∼4.4 to 5.7 GPa at cratonic mantle temperatures (Izraeli et al., Reference Izraeli, Harris and Navon1999; Sobolev et al., Reference Sobolev, Fursenko, Goryainov, Shu, Hemley, Mao and Boyd2000; Bassoo and Befus, Reference Bassoo and Befus2021). Combined Raman spectroscopic analyses and diamond residence temperatures of forsterite and coesite inclusions in Arkansas diamond inclusions record residual pressures from ∼ –0.22 to 2.61 GPa. The single coesite inclusion records both negative and positive residual pressures indicating both tension and compression within it. We therefore assume anisoptropy of coesite and do not extrapolate entrapment pressures. Forsterite inclusions indicate entrapment at ∼ 5.21±0.21 GPa and 1163±58°C (Table 4). Such pressures and residence temperatures plot best along palaeo-geotherms between 40 and 43 mW/m2 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Elastic thermobarometry of forsterite and coesite entrapment conditions in Arkansas diamonds and previous thermobarometric estimates of diamond inclusions and Cr-diopside mantle xenocrysts from Argyle, Australia (Jaques et al., Reference Jacques, Hall, Sheraton, Smith, Sun and Drew1989; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018; Jaques et al., Reference Jacques, Luguet, Smith, Pearson, Yaxley and Kobussen2018; Sudholz et al., Reference Sudholz, Jaques, Yaxley, Taylor, Czarnota and Haynes2023) and garnet lherzolite and websterite xenoliths from Prairie Creek, USA (Dunn, Reference Dunn2003). Also included are estimated paleo-geotherms of the Slave (Kopylova et al., Reference Kopylova, Russell and Cookenboo1999) and Siberian Craton (Dymshits et al., Reference Dymshits, Sharygin, Malkovets, Yakovlev, Gibsher, Alifirova, Vorobei, Potapov and Garanin2020), using the parameters of Hasterok and Chapman (Reference Hasterok and Chapman2011). 1σ standard error of ∼0.6 GPa. Graphite to diamond transition line modified from Day (Reference Day2012). Adiabat based on mantle potential temperatures of 1300–1400°C

Table 4. Summary of calculated residual pressures of forsterite, coesite and diopside inclusions in diamonds from Arkansas

1 Notes: relative to 854.36 cm–1 of San Carlos olivine Fo90 (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Brown, Slutsky and Zaug1997) for forsterite, relative to 521 cm–1 of synthetic coesite (Sobolev et al., Reference Sobolev, Fursenko, Goryainov, Shu, Hemley, Mao and Boyd2000); 2Assuming a 3.09 cm–1 per GPa (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sharma and Cooney1993) for forserite and 2.9 cm–1, 0.66 cm–1, 0.45 cm–1, 0.44 cm–1 per GPa for the Raman bands 521 cm–1, 466 cm–1, 427 cm–1, 355 cm–1 respectively (Hemley Reference Hemley, Manghnani and Syono1984; Sobolev et al., Reference Sobolev, Fursenko, Goryainov, Shu, Hemley, Mao and Boyd2000) for coesite, 3 2σ = 62°C, assuming an eruption age of 102 Ma (Zartman, Reference Zartman1977; Gogineni et al., Reference Gogineni, Melton and Giardini1978), and a mean assumed formation age of 1.4 between 1.6 and 1.4 Ga or the inferred age of Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane (Alibert and Albarède, Reference Alibert and Albarède1988, Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Shirey and Bergman1995; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014), and therefore residence time of 1.3 Ga. Nitrogen concentration was calculated from individual spectra by applying the Beer-Lambert law and absorption values of nitrogen bands at 1365, 1284, and 1175 cm–1, using the least-squares fitting approach combined with a basic linear correction in the DiaMap excel spreadsheet (e.g. Howell et al., Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012a, Reference Howell, O’Neill, Grant, Griffin, Pearson and O’Reilly2012b).

Discussion

Tectonic setting

The ‘North American Craton’ is a complex assemblage of Archean terranes sutured together by Proterozoic orogens (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1988). Arkansas lamproites erupted through cratonic rocks of the 1.55 to 1.35 Ga Granite–Rhyolite Province, just to the south of the Mazatzal Province and north of the Grenville orogen (Fig. 1) (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Begg, Dunn, O’Reilly, Natapov and Karlstrom2011).

Diamond formation and storage within the subcontinental lithospheric mantle (SCLM) of the Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane seems unlikely because it generally does not exceed 150 km thickness. There are, however, local seismic anomalies which may approach 200 km in depth today (Schaeffer and Lebedev, Reference Schaeffer and Lebedev2014). Indeed, the Prairie Creek lamproite at the time of eruption was probably underlain by a thick lithosphere which was at most 190 km. This is postulated to be the result of tectonic stacking of subcontinental lithospheric mantle rocks during terrane accretion and stabilisation between 1.80 and 0.95 billion years ago beneath the southern edge of the Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane that has since thinned to its current depth (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, O’Reilly, Doyle, Pearson, Coopersmith, Kivi, Malkovets and Pokhilenko2004; Dunn, Reference Dunn2003; Whitmeyer and Karlstrom, Reference Whitmeyer and Karlstrom2007).

Primary diamond occurrences along cratonic margins are rare but can be prospective to plastically deformed and fancy coloured pink, brown and violet diamonds, as is the case for the Ellendale and Argyle mine in northwestern Australia and the Bunder lamproite field in India (Hall and Smith, Reference Hall, Smith, Glover and Harris1985; Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Hall, Sheraton, Smith, Sun and Drew1989; Bulanova et al., Reference Bulanova, Smith, Walter, Blundy, Gobbo and Kohn2008; Luguet et al., Reference Luguet, Jaques, Pearson, Smith, Bulanova, Roffey, Rayner and Lorand2009; Gaillou et al., Reference Gaillou, Post, Bassim, Zaitsev, Rose, Fries, Stroud, Steele and Butler2010; Smit et al., Reference Smit, Shirey, Richardson, le Roex and Gurney2010; Eaton-Magaña et al., Reference Eaton-Magaña, Ardon, Smit, Breeding and Shigley2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bulanova, Kobussen, Burnham, Chapman, Davy and Sinha2018; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018). Cratonic margins coincident with subducting slabs may create an environment favourable for plastic deformation of diamond and thus lead to the occurrence of diamonds with brown to pink colours. The transition between relatively thick and thinned lithosphere is conducive to the formation of edge-driven convection cells, generated by subducting and descending oceanic slabs (Elder, Reference Elder1976; King and Anderson, Reference King and Anderson1998; Usui et al., Reference Usui, Nakamura, Kobayashi, Maruyama and Helmstaedt2003; Kjarsgaard et al., Reference Kjarsgaard, Heaman, Sarkar and Pearson2017). This dynamic tectonic environment in a highly viscous upper mantle could be the mechanism that deforms diamonds along the southern margin of the North American Craton. In some cases, upwards migration of kimberlite and lamproite melts might also be facilitated by the leading edge of a subducting slab in an edge driven convection cell to then entrain diamonds from the lithosphere during their ascent to the surface (e.g. Barron et al., Reference Barron, Lishmund, Oakes, Barron and Sutherland1996; Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, O’Reilly, Davies, Vokes, Marshall and Spry1998; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018). Indeed, Arkansas lamproites have emplacement ages which coincide with the Mesozoic subduction of the Farallon slab (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Spasojevic and Gurnis2008). However, it should be noted that diamondiferous rock associations with subduction may be entirely coincidental. We document physical and spectroscopic characteristics of Arkansas diamonds which may have formed in such mantle conditions and highlight a previously undescribed subpopulation of Arkansas diamonds which share traits in common with the CLIPPIR suite of diamonds.

Literature review of Arkansas diamond-hosted inclusion compositions

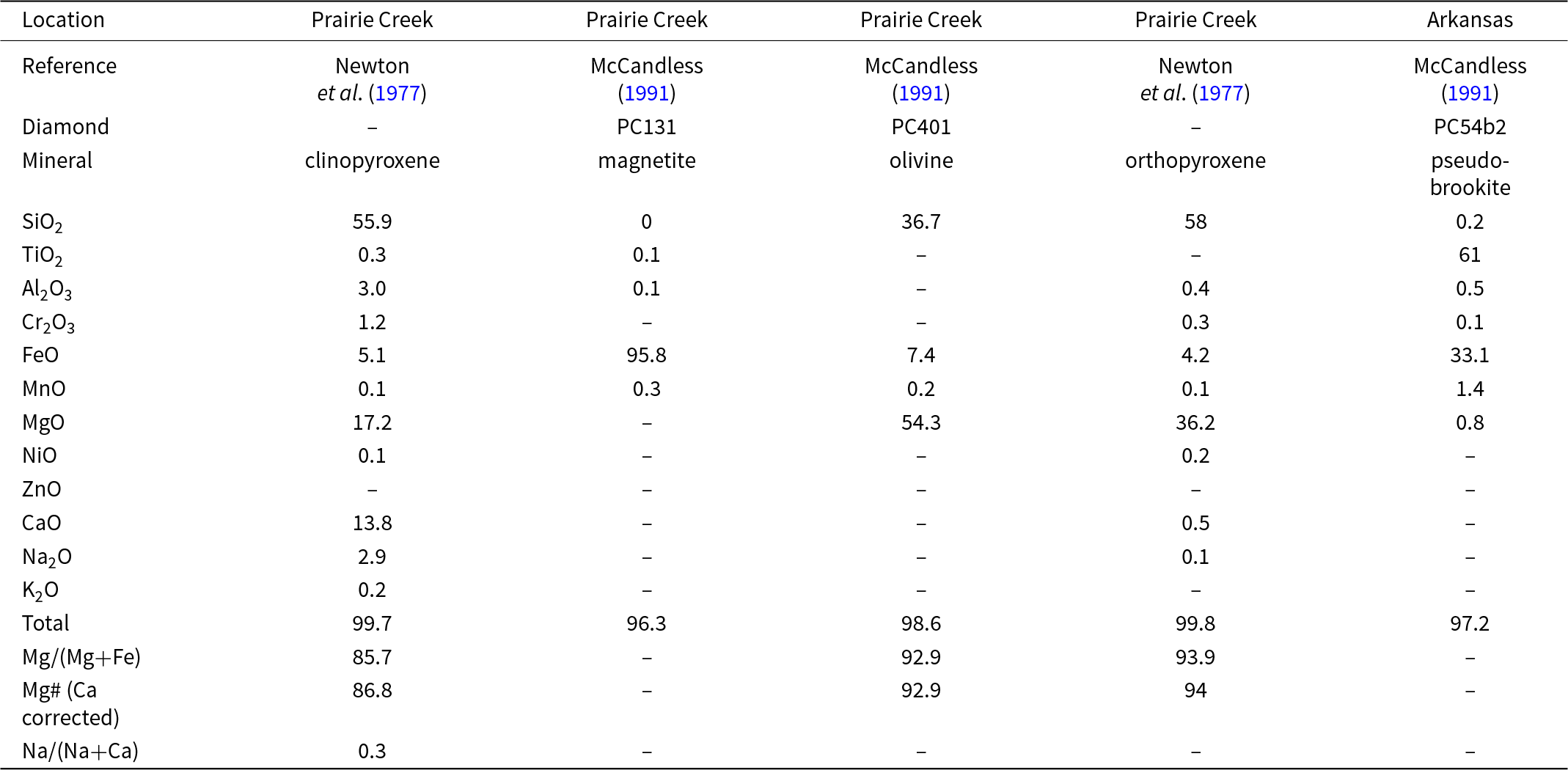

Mineral inclusions within diamonds have compositions that reflect their mantle sources. We review previously published results in the context of our new analysis to better constrain diamond formation beneath the southern edge of the North American craton (Table 5). Inclusions suites from primary diamonds from Arkansas are predominantly eclogitic including metallic sulfides with a minor proportion of peridotitic diamonds (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Melton and Giardini1977; Pantaleo et al., Reference Pantaleo, Newton, Gogineni, Melton and Giardini1979; McCandless, Reference McCandless1991). Geochemical data for the inclusions is limited to single data points (Table 5). One low-Cr clinopyroxene inclusion in an Arkansas diamond had an Mg# of 87, which was lower than that expected for clinopyroxene derived from lherzolite and harzburgite (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Melton and Giardini1977). This inclusion also has relatively elevated concentrations of elements that are typically incompatible in mantle peridotite, including Na, K and Ti, when compared to global occurrences (Supplementary Table S1). The presence of clinopyroxene, magnetite, pseudobrookite, magnetite inclusions and the sole clinopyroxene composition suggest an eclogitic paragenesis. Additionally, coesite and rutile cannot form in equilibrium with olivine in peridotitic mantle. Their presence as inclusions in Arkansas diamonds support the presence of subducted, metamorphosed and silica-oversaturated meta-basalts within the diamondiferous mantle beneath Arkansas (Schulze et al., Reference Schulze, Harte, Page, Valley, Channer and Jaques2013). The single olivine inclusion analysed was low in Ca and preserved a Mg# of 93, placing it within the range expected for peridotitic rocks worldwide (McCandless, Reference McCandless1991; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Aulback and Harris2022a). Additionally, only four olivine inclusions are recognised in three Arkansas diamonds thereby providing evidence for peridotite as a minor diamond host.

Table 5. Compositions of inclusions in Arkansas diamonds

Isotopically, δ13C values for diamonds from Arkansas have a mean δ13C ∼ –6±5‰ and are within the range expected of both eclogitic and peridotitic diamond δ13C values (Fig. 10) (Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Cartigny, Chacko and Pearson2022b). Two diamonds with strongly depleted δ13C < –21‰ plot away from mantle values. Previous modelling suggests values <–14‰ cannot be achieved by Rayleigh fractionation and are more likely to be related to recycled oceanic crust (Smart et al., Reference Smart, Chacko, Stachel, Muehlenbachs, Stern and Heaman2011; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Cartigny, Chacko and Pearson2022b). Diamond composition, inclusion suites and geochemistry suggest subduction-influenced formation from eclogitic and possibly oceanic protoliths mixed with peridotitic rocks beneath the cratonic margin.

Figure 10. δ13C compositions of diamonds from the Arkansas compared to those from Argyle (Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Aulback and Harris2022a and references therein; McCandless, Reference McCandless1991). Peridotite and eclogite ranges adapted from Cartigny (Reference Cartigny2005).

Formation and residence

Dodecahedral habits and common hillocks are physical features that indicate Arkansas diamonds experienced significant mantle and melt resorption. Most diamonds have flat bottomed dissolution, microdisc and corrosion sculpture textures which collectively indicate most diamonds were exposed to melts with a relatively high H2O to CO2 ratio (Tappert and Tappert, Reference Tappert and Tappert2011; Fedortchouk, Reference Fedortchouk2015). Hexagonal dissolution pits observed on one Arkansas diamond suggest at least some diamonds were also exposed to fluid compositions with CO2/(CO2+H2O) >0.9 during their ascent to the crust (Fedortchouk, Reference Fedortchouk2019). About 30% of Arkansas diamonds preserve deformation lamellae and brown body colours, indicating they experienced plastic deformation in the mantle (Orlov, Reference Orlov1977; Robinson, Reference Robinson1979; McCallum et al., Reference McCallum, Huntley, Falk and Otter1991; Gaillou et al., Reference Gaillou, Post, Bassim, Zaitsev, Rose, Fries, Stroud, Steele and Butler2010).

Palaeo-thermobarometry of diamond formation

The diamonds examined in this investigation are from precious personal collections and we were not permitted to extract inclusions for this study. Raman and infrared spectroscopy therefore offer alternative, non-destructive ways to calculate entrapment conditions where coexisting mineral pairs and assumptions of thermodynamic equilibrium are unavailable (e.g. Izraeli et al., Reference Izraeli, Harris and Navon1999; Angel et al., Reference Angel, Alvaro and Nestola2017; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Aulback and Harris2022a). Forsterite and coesite inclusions in Arkansas diamonds record entrapment pressures ∼5 GPa. Nitrogen aggregation suggests residence temperatures ranging from 1100 to 1220°C. Pressure–temperature conditions estimated from inclusions in diamonds from Arkansas indicate typical formation conditions expected of cratonic diamonds globally (Stachel and Harris, Reference Stachel and Harris2008). This is unexpected because independent geophysical studies corroborate formation within the craton margin and relatively shallow tectonic environments suggesting general thermal regimes unfavourable for diamond stability within the graphite field (Fig. 8) (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Dueker, Schmandt and Yuan2013; Schaeffer and Lebedev, Reference Schaeffer and Lebedev2014; Kjarsgaard et al., Reference Kjarsgaard, Heaman, Sarkar and Pearson2017). However, pressure estimates ≥4.6 GPa from garnet lherzolite mantle xenoliths and garnet xenocrysts suggest the lithosphere beneath Arkansas may have been at most 190 km and possibly more laterally extensive, at the time of eruption of the Prairie Creek lamproite (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Smith and Bergman2002, Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, O’Reilly, Doyle, Pearson, Coopersmith, Kivi, Malkovets and Pokhilenko2004; Dunn, Reference Dunn2003). Additionally, the timing of eruption is coincident with the subduction of the Farallon slab during the Mesozoic (Alibert and Albarède, Reference Alibert and Albarède1988; Heaman, Reference Heaman1989; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Shirey and Bergman1995; Dunn, Reference Dunn2003; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Spasojevic and Gurnis2008; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Carlson, Frost, Hearn and G.N2014). Subduction, therefore, may have played a role in subsequent thinning of the lithosphere beneath Arkansas to its current observable depth and lateral distribution. Hydrous partial melting during subduction could weaken the base of cratonic roots creating favourable conditions for delamination and lithospheric thinning (e.g. Liu et al., Reference Liu, Morgan, Xu and Menzies2018; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Li, Chen and Morgan2021). This is similarly observed at Argyle, Australia where diamonds are thought to form in a subduction-related tectonic regime (Fig. 8) (Jaques et al., Reference Jacques, Luguet, Smith, Pearson, Yaxley and Kobussen2018; Timmerman et al., Reference Timmerman, Honda, Zhang, Jaques, Bulanova, Smith and Burnham2019).

Preservation of defects and diamond deformation

Photoluminescence, infrared and visible spectroscopy can be used to reveal diamond defects related to formation conditions and subsequent tectonic activity, including deformation. Diamond is composed of carbon but intrinsic and extrinsic impurities can form during diamond growth, mantle residence, entrainment into ultramafic magmas and during lower-temperature residence in the crust. Impurity and vacancy related defects specifically inform us of diamond formation and residence.

Diamonds from Arkansas record spectroscopic evidence of Ni impurities. These impurities may have been incorporated during Ni-rich metasomatism of lithospheric mantle (Giuliani et al., Reference Giuliani, Kamenetsky, Kendrick, Phillips and Goemann2013). Arkansas diamonds are nominally colourless, but <10% have a yellow colour caused by the presence of nitrogen (Shigley and Breeding, Reference Shigley and Breeding2013). More than 25% of diamonds have complex nitrogen defects, and more than 50% of diamonds have >200 at.ppm N. They also tend to be more strongly aggregated in nitrogen than those at Argyle, which are also known to be derived from the craton margin (Fig. 7a, Bulanova et al., Reference Bulanova, Speich, Smith, Gaillou, Kohn, Wibberley, Chapman, Howell and Davy2018). Indeed, on the basis of nitrogen aggregation, a subpopulation of Arkansas diamonds record minimum residence temperatures of ∼1320°C, indicating residence at very high temperatures for millions or billions of years, such as those that prevail in the base of the lithospheric mantle or uppermost asthenospheric mantle (Leahy and Taylor, Reference Leahy and Taylor1997). In addition, most diamonds from Arkansas have a narrow range of N3VH peak area per NB aggregation which is lower than that expected of diamonds from within craton settings, such as those analysed from the Slave and Superior cratons and is lower than Argyle (Fig. 7b). Arkansas diamonds did not experience the maximum N3VH centre creation as a consequence of A to B centre aggregation (Melton, Reference Melton2013; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018; Bulanova et al., Reference Bulanova, Speich, Smith, Gaillou, Kohn, Wibberley, Chapman, Howell and Davy2018). Diamonds from Arkansas instead indicate a lower concentration of available infrared-active hydrogen to accommodate N3 centre creation (Melton, Reference Melton2013). These observations may suggest NA to NB aggregation is more efficient than the production of N3VH defects, which might be caused by enhanced diffusion of nitrogen in diamond during plastic deformation and/or exposure to high thermal changes (Evans, Reference Evans1992; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Kiflawi, Luyten, Vantendeloo and Woods1995). Indeed, Arkansas diamonds preserve moderate incidences of plastic deformation related defects and a sub-population of IaB diamonds which probably experienced exposure to high thermal perturbations (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Kiflawi, Luyten, Vantendeloo and Woods1995).

About 30% of diamonds from Arkansas are brown with deformation lamellae and more than 45% have spectral features indicating that they experienced plastic deformation (Tables 1, 2). Brown and pink colour in diamonds can manifest as a more uniform body colour or be concentrated within parallel narrow bands termed deformation lamellae. Brown colouration in diamond is related to vacancy clusters along the {111} plane and are interpreted to have formed by plastic deformation (Hounsome et al., Reference Hounsome, Jones, Martineau, Fisher, Shaw, Briddon and Oberg2006; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Sibley and Kelly2009; Gaillou et al., Reference Gaillou, Post, Bassim, Zaitsev, Rose, Fries, Stroud, Steele and Butler2010; Eaton-Magaña et al., Reference Eaton-Magaña, Ardon, Smit, Breeding and Shigley2018). Applied stress altered the atomic structure of the diamond and created vacancies (Gaillou et al., Reference Gaillou, Post, Bassim, Zaitsev, Rose, Fries, Stroud, Steele and Butler2010). Diamond defects responsible for brown body colours were probably acquired during their long residence up to 1 billion years and within the shallow lithospheric mantle at ∼100 km (Collins, Reference Collins1982; Drury and Fitzgerald, Reference Drury, FitzGerald and Jackson1998; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Kanda and Kiflawi2000; Gaillou et al., Reference Gaillou, Post, Bassim, Zaitsev, Rose, Fries, Stroud, Steele and Butler2010; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Helmstaedt and Flemming2010; Shirey and Shigley, Reference Shirey and Shigley2013). Furthermore, a population of 4% of Arkansas diamonds are relatively large (>0.7 cts.), inclusion poor, Type IIa with <5 at.ppm N, irregular to flattened in habit, strongly resorbed and colourless. Similarly non-faceted, large, colourless and irregular diamonds historically have been recovered from the Prairie Creek lamproite including the ∼40 carat Uncle Sam and the ∼15 carat Star of Arkansas (Leiper, Reference Leiper1957). The relatively large size, strongly resorbed and irregular morphology, absence of colour and very low nitrogen content are traits shared by so-called CLIPPIR diamonds, which are inferred to be derived from sub-lithospheric depths and possibly as deeply as the transition zone or uppermost lower mantle (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Shirey, Nestola, Bullock, Wang, Richardson and Wang2016). Globally, CLIPPIR diamonds are rare, and comprise a small percentage of diamond populations. Of diamonds submitted to GIA for example, inclusion bearing CLIPPIR diamonds comprise 0.0001%. Examples of CLIPPIR diamonds have been recovered from the Premier and Letseng kimberlites in South Africa, and potentially also the Argyle lamproite in Western Australia (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Shirey, Nestola, Bullock, Wang, Richardson and Wang2016; Pay, Reference Pay2017; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Shirey and Wang2017; Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018; Shirey et al., Reference Shirey, Pearson, Stachel and Walter2024).

Conclusions

Arkansas has moderate incidences of plastically deformed and potentially sub-lithospheric diamonds exposed to high-temperature perturbations. Subduction processes may cause plastic deformation of a diamond entrained in a highly viscous and dynamic upper mantle. In this way subduction-driven tectonic settings might be more favourable for plastically deformed pink to brown diamonds along the margin of cratons. This has been similarly suggested for the Argyle mine, where diamonds might have originated from and deformed within the lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary (Stachel et al., Reference Stachel, Harris, Hunt, Muehlenbachs and Kobussen2018).

The Yavapai-Mazatzal terrane has isolated ‘pockets’ of diamondiferous lithosphere, and cratonic roots may have been more laterally extensive and may have extended to 190 km depth in the past (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, O’Reilly, Doyle, Pearson, Coopersmith, Kivi, Malkovets and Pokhilenko2004; Dunn, Reference Dunn2003; Whitmeyer and Karlstrom, Reference Whitmeyer and Karlstrom2007). A review of geochemical and geophysical data suggests that subsequent thinning of the lithosphere has left behind highly localised zones of mantle heterogeneity, depleted lithosphere and relatively thick mantle roots but within surrounding thinned lithosphere along the Southern margin of what constitutes the North American craton.

Arkansas has a sub-population of diamonds which are relatively large, largely inclusion free, strongly resorbed and Type IIa. These morphological and spectroscopic traits are shared with sub-lithospheric CLIPPIR diamonds. Future studies to identify inclusion species and compositions within these diamonds could confirm CLIPPIR diamond occurrences in Arkansas.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2024.92.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dennis Dunn, Troy Savage, Don Roeder, Craig Zapf, Scott Kreykes, Tom Paradise and Glenn Worthington for their Arkansas diamond samples, insight into Prairie Creek geology and how to mine for diamonds. We are indebted also to Nathan Renfro, Emily Lane and Judy Colbert of the GIA for diamond photographs. We thank the reviewers for improving the quality of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.