Introduction

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral interventions, such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, Reference Resick, Monson and Chard2024), have consistently been shown to be highly effective for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Asmundson et al., Reference Asmundson, Thorisdottir, Roden-Foreman, Baird, Witcraft, Stein, Smits and Powers2019; Watts et al., Reference Watts, Schnurr, Mayo, Young-Xu, Weeks and Friedman2013). Individuals who complete these treatments generally show large symptom reductions, which are generally sustained over time (Held et al., Reference Held, Smith, Parmar, Pridgen, Smith and Klassen2024; Resick, Williams, Suvak, Monson, & Gradus, Reference Resick, Williams, Suvak, Monson and Gradus2012; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Schumacher, Hannig, Barth, Lotzin, Schäfer and Kleim2021). However, when looking beyond group averages, research has demonstrated that not all individuals respond equally to evidence-based treatments (Held et al., Reference Held, Smith, Bagley, Kovacevic, Steigerwald, Van Horn and Karnik2021; Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, King, Smith, Gradus, Resick and Galovski2021; Schumm, Walter, & Chard, Reference Schumm, Walter and Chard2013).

A goal of clinical care is to produce optimal outcomes for every individual. To better understand the observed variability in PTSD treatment outcomes, researchers have begun to test whether machine learning can be leveraged to identify factors that impact both PTSD severity in general (Galatzer-Levy, Karstoft, Statnikov, & Shalev, Reference Galatzer-Levy, Karstoft, Statnikov and Shalev2014; Karstoft, Galatzer-Levy, Statnikov, Li, & Shalev, Reference Karstoft, Galatzer-Levy, Statnikov, Li and Shalev2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ouyang, Jiao, Cheng, Zhang, Shang and Liu2024) and response to treatment more specifically (Held et al., Reference Held, Schubert, Pridgen, Kovacevic, Montes, Christ and Smith2022; Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, King, Smith, Gradus, Resick and Galovski2021; Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). Findings from this research are promising, with studies suggesting that machine learning models are capable of identifying individuals who are predicted to respond to treatment quickly, as well as those who are not likely to experience meaningful symptom improvement, with high accuracy both before treatment begins (Held et al., Reference Held, Schubert, Pridgen, Kovacevic, Montes, Christ and Smith2022) and early in treatment (Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, King, Smith, Gradus, Resick and Galovski2021). Studies have also demonstrated that treatment-response predictions can be further improved through continuously updating machine learning models that utilize data captured throughout treatment (Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). Use of updating machine learning models may allow clinicians to optimize treatment outcomes, for example, by altering the course of treatment or complementing it with alternative strategies when the model indicates that a patient is unlikely to improve on the current course.

Although prediction psychiatry and the use of predictive analytics to estimate and ultimately improve treatment outcomes are promising, it has yet to be studied whether available models perform significantly better at predicting clinical outcomes than clinicians. This question builds on a longstanding line of work contrasting clinical and actuarial prediction in psychology and medicine (Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, Reference Dawes, Faust and Meehl1989; Swets, Dawes, & Monahan, Reference Swets, Dawes and Monahan2000). Measurement-based care (Scott & Lewis, Reference Scott and Lewis2015) is a core component of many evidence-based interventions and provides clinicians with important data about their patients’ performance in treatment based on self-reported data, which is the same data that are often used to build machine learning models (e.g. Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, King, Smith, Gradus, Resick and Galovski2021; Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). Clinicians already use these data to discuss progress (or lack thereof) with their patients and evaluate potential adjustments to the treatment they deliver based on the information, such as adjusting the treatment targets (Scott & Lewis, Reference Scott and Lewis2015). Thus, if clinicians already have access to this information, it is plausible that they also develop mental models of their patients’ progress and make predictions about likely overall symptom reduction and treatment endpoint PTSD severity. The amount of self-report and other clinical data (e.g. behavioral observations, changes in patient affect) increases throughout treatment; therefore, clinicians may also have increasing accuracy and confidence in their predictions as treatment progresses.

To study these assumptions, it is imperative to directly compare clinicians’ predictions of treatment outcomes with those of existing machine learning models. Doing so would also allow us to better understand the strengths and limitations of existing precision psychiatry use cases and enable us to develop tools that can enhance clinicians’ capabilities, not merely duplicate them. In this study, we compared three different machine learning models to clinicians’ predictions of their patients’ symptom change and posttreatment PTSD severity. Specifically, we evaluated the ability to predict a 10-point change on the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr2013), which is often considered a clinically meaningful reduction in PTSD symptoms (National Center for PTSD, n.d.). We also examined prediction accuracy for determining whether a patient would end the program at or below a PCL-5 score of 33, which is considered a threshold for meeting the criteria for likely PTSD (National Center for PTSD, n.d.). (Newer research that was published after the present study was conceived has suggested a 15-point PCL-5 change to be indicative of clinically meaningful change and a score above 28 to indicate a probable PTSD diagnosis (Marx et al., Reference Marx, Lee, Norman, Bovin, Sloan, Weathers, Keane and Schnurr2022).) Finally, we also assessed clinician confidence to determine whether it increased as treatment progressed and more data became available, as well as to evaluate whether clinician confidence impacted prediction accuracy. We hypothesized that machine learning models would have significantly better prediction accuracy compared to clinicians across both outcomes of interest and that clinician confidence would both improve over time and be associated with prediction accuracy.

Methods

Clinician participants

A total of 20 clinicians participated in the current study. All participants held at least a master’s degree and were clinicians who provided CPT as part of a 2-week accelerated PTSD treatment program (ATP) at the Road Home Program: Center for Veterans and their Families at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, IL. The sample was 70.00% female and 30.00% male. Clinicians identified their race as 65.00% non-Hispanic White, 20.00% Hispanic White, 10.00% Black, and 5.00% ‘other’. The average age of clinician participants was 32.05 years (SD = 4.30; range 27–43 years). The average self-reported years since licensure for the sample was 2 years (SD = 2.92) with 3.42 years (SD = 2.82) of experience providing CPT. To qualify for the current study, clinicians had to have completed CPT training and consultation through a national CPT trainer.

Patient population

Clinicians were asked to make predictions about the service member or veteran they were treating in individual CPT during the ATP. Ratings were made on a total of 194 patients who attended the ATP. An additional 508 patients from the same program were used to train machine learning and statistical prediction models. The patient population was 54.99% male and 45.01% female. Patients identified their race as 55.95% non-Hispanic White, 6.61% Hispanic White, 22.32% Black, 2.20% Asian, 1.17% Pacific Islander, and 10.13% ‘other’. The average patient age was 44.77 years (SD = 10.25; range 20–84 years).

Measures

Demographics

Clinicians self-reported age, gender, race, level of education, years licensed to practice, and the number of years they have been providing CPT.

Treatment-response prediction survey

Clinicians were asked to complete a brief survey at the beginning of each treatment day about whether they believed their patient would respond by the end of treatment and how confident they felt about their prediction. Clinicians responded to the following: 1) Do you believe your patient’s PCL-5 score will reduce by 10 points by the end of treatment (Yes/No)? How confident are you in your answer (0–100%)? 2) Do you believe your patient’s PCL-5 score will fall below 33 points by the end of treatment (Yes/No)? How confident are you in your answer? How confident are you in your answer (0–100%)? Clinicians had access to the PCL-5 measurements completed that day and on previous days.

PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr2013)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses PTSD symptom severity according to DSM-5 criteria. Consistent with measurement-based care practices (Scott & Lewis, Reference Scott and Lewis2015) and CPT (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Monson and Chard2024), patients completed the PCL-5 at baseline, treatment days 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, and posttreatment. (Repeated measurement as well as assessing past-day PTSD symptom severity has previously been shown to be appropriate for intensive treatment (Roberge et al., Reference Roberge, Wachen, Bryan, Held, Rauch and Rothbaum2025).) Symptoms are rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Scores can range from 0–80 with higher scores indicating higher symptoms severity. Probable PTSD is considered if scores are at or above 33 points on the PCL-5 (National Center for PTSD, n.d.). For the purpose of this study, the 33-point cutoff was utilized. At baseline, patients report on the past month symptom severity. During treatment and posttreatment, patients report on the past-week PTSD severity.

Procedure

Clinicians were asked to complete the treatment-response survey via REDCap each morning prior to meeting with their patient for their first individual CPT session. Participants were encouraged to utilize all information available to them to make their predictions, including chart review, direct interaction with their patient, and previous scores on their patient’s self-report surveys. All clinicians provided CPT as part of an ATP. The 2-week ATP consists of 16 individual CPT sessions, as well as adjunctive services such as mindfulness and psychoeducational groups. Additional information about the ATP can be found in Held, Smith, Pridgen, Coleman, and Klassen (Reference Held, Smith, Pridgen, Coleman and Klassen2023). The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Statistical analysis

We first examined the association between clinicians’ confidence in the accuracy of their predictions and the accuracy of each prediction using logistic mixed-effects models. Time-varying confidence ratings were partitioned into between- and within-subjects components to assess whether improvements in accuracy were associated with increases in performance, or whether any association between confidence and accuracy could be explained by between-participant differences. (We further explored the potential for nesting at the clinician-level by incorporating a third (clinician) level in mixed-effects models. However, results indicated that less than 1% of the variability in accuracy could be explained at the clinician-level, and clinician-level covariates were not significant predictors. We therefore report the results of the more appropriate two-level model here.)

Three machine learning and statistical approaches were utilized to generate predictions of 10-point reduction and posttreatment scores below 33 on the PCL-5. We used two of these approaches in previously published analyses using continuously updating machine learning models for precision psychiatry (Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are designed to capture temporal dependencies by maintaining a hidden state that evolves over time. This architecture allows RNNs to effectively learn patterns and trends across repeated measures, making them ideal for longitudinal analyses in which past observations inform end-of-program outcomes. This approach utilized a single-layer long short-term memory architecture to integrate sequential symptom scores in PCL-5 and PHQ-9 across program timepoints, along with baseline covariates. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss over 20 epochs and a batch size of 32. Similarly, mixed-effects random forest (MERF) take advantage of the flexibility of the tree-based structure in random forests to capture nonlinear relationships in combination with mixed-effects modeling to account for within-subject correlation. This was trained using 200 decision trees, Gini impurity as the split criterion, and bootstrapped sampling. Logistic generalized mixed-effects models with random intercepts were also used here, as they are considered a gold-standard statistical approach to modeling longitudinal data, and have been demonstrated to be as effective as machine learning approaches in predicting treatment response in prior work (Hedeker & Gibbons, Reference Hedeker and Gibbons2006; Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). (Three-level models, exploring nesting by clinician as the third level, were also explored. However, intraclass correlation (ICC) values indicated that insufficient amount of variability existed at the clinician level to justify this approach (ICCs < .01), thus only two-level models are reported here.) A combination of demographic and baseline clinical features were included in all machine learning models, as well as updated PTSD and depression severity values (see Supplemental Table S1 for a full list of features).

To compare accuracy across timepoints between clinician ratings and machine learning models we utilized logistic mixed-effects models predicting accuracy at each timepoint. This longitudinal analytic approach included random intercepts and slopes and accounts for within-subject correlation and participant-level variability over time. Rater type (machine vs. clinician) was examined as a fixed effect to examine overall differences in accuracy across timepoints, and rater-by-time interactions assessed whether changes in accuracy occurred over time. Machine learning models were conducted using R, and accuracy comparisons and mixed-effects models were explored within Stata version 17.

Results

A higher proportion of patients improved by 10 points on the PCL-5 (75.36%) than those who ended treatment below 33 points (58.26%), and 53.58% met both criteria for treatment response. Clinician confidence in predictions of these outcomes ranged from 71.61% (SD = 17.03) to 91.98% (SD = 13.43) when predicting a 10-point PCL-5 reduction, and between 63.57% (SD = 22.05) and 91.77% (SD = 11.81%) when predicting whether participants would complete treatment with a PCL-5 score below 33 points (see Figures 1 and 2). Correspondingly, clinician accuracy in predicting a PCL-5 reduction of 10 points increased from 73.82% (SD = 44.08) at the start of treatment to 88.82% (SD = 31.62) on the last day of treatment. Accuracy in predicting a final PCL-5 score below 33 ranged from 63.20% (SD = 48.59) to 87.50% (SD = 33.18). Both accuracy and confidence in predictions were generally higher in predictions of a 10-point reduction than in predictions of completing the program with a final PCL-5 below 33.

Figure 1. Prediction of a 10-point PCL-5 reduction. Note: LMM, linear mixed-effects model; MERF, mixed-effects random forest; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; RNN, recurrent neural network.

Figure 2. Prediction of end-of-treatment scores at or below 33 points on the PCL-5. Note: LMM, linear mixed-effects model; MERF, mixed-effects random forest; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; RNN, recurrent neural network.

Greater confidence among clinicians was associated with greater overall accuracy in logistic mixed-effects models, both for predicting a 10-point reduction (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08, p < .001) and a final PCL-5 score below 33 (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04–1.08, p < .001). Partitioning between- and within-subjects effects indicated that both between- and within-subjects components (ps < .001) were significant in predicting accuracy in 10-point reduction predictions. Similarly, between- and within-subjects effects were significant in predicting accuracy for final PCL-5 scores below 33 (ps < .001), indicating that clinicians who were more accurate were significantly more confident, and that within-subject increases in confidence were associated with increases in accuracy.

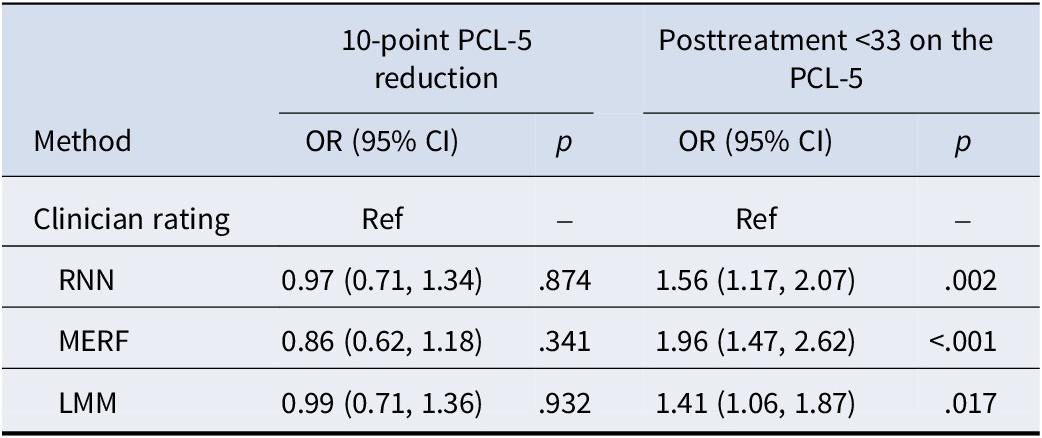

Examination of fixed effects of rater types in logistic mixed-effects models predicting accuracy indicated that machine learning and statistical approaches were significantly more accurate across program timepoints at predicting completion of the program with PCL-5 scores below 33 points (p < .001; see Table 1). This accuracy advantage was significant for all machine learning and statistical model types (see Figure 3). However, the rater-by-time interaction was not significant (p = .790), indicating that this effect did not differ significantly across program timepoints. This advantage for machine learning models existed only for predictions of completing the program with PCL-5 values below 33, however, as no significant difference in accuracy was found between machine learning predictions and clinician predictions of a 10-point PCL-5 reduction (p = .734; Figure 4). Feature-importance values for machine learning models indicated that updating PTSD severity scores, followed by updating depression severity scores, were the features driving model predictions (Supplemental Figure S1).

Table 1. Prediction accuracy comparisons between clinician ratings and machine learning approaches

Note: LMM, logistic mixed-effects model; MERF, mixed-effects random forest; RNN, recurrent neural network.

Figure 3. Confidence and accuracy predicting a 10-point PCL-5 reduction. Note: PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Figure 4. Confidence and accuracy predicting end-of-treatment scores at or below 33 points on the PCL-5. Note: PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Discussion

This study compared three different machine learning models to clinician predictions of veteran patients’ PTSD symptom change and posttreatment symptom severity. Additionally, clinician confidence was evaluated to determine the extent to which it improved as treatment progressed and how it related to prediction accuracy.

All three machine learning models outperformed clinicians in predicting whether patients would report their symptoms below 33 points on the PCL-5 at posttreatment. Accuracy increased as treatment progressed, which is to be expected as more data become available and the time to posttreatment shortens, which aligns with prior research (Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, King, Smith, Gradus, Resick and Galovski2021; Smith & Held, Reference Smith and Held2022). At the start of the second half of the 2-week ATP, the best-performing machine learning model was able to predict the likelihood of falling below the probable PTSD threshold with 81.96% accuracy. Despite the machine learning models outperforming clinicians, it is important to note that by the start of the second half of treatment clinicians still had a good ability to predict posttreatment severity (clinician accuracy: 74.14%). Given the relatively high accuracy of machine learning models even in the beginning phases of treatment, where they more clearly surpassed clinicians’ ability to make accurate predictions, such models may be particularly helpful for early identification of individuals who may end treatment with PTSD symptoms consistent with a probable diagnosis of PTSD. These findings also resonate with the broader literature contrasting clinical and actuarial prediction, which has consistently shown advantages of statistical approaches in many domains (Dawes et al., Reference Dawes, Faust and Meehl1989; Swets et al., Reference Swets, Dawes and Monahan2000). This information may be useful for adjusting treatment early to attempt to better reduce PTSD symptoms or to identify an optimal second course of treatment to resolve other concerns that may prevent PTSD symptoms from reducing further.

The machine learning models did not perform better than clinicians in predicting whether patients would report a 10-point or greater decrease on the PCL-5. Both groups had very high accuracy levels throughout treatment that further improved over time, as would be expected. There are several possible explanations for this observation. The most plausible explanation is that it was likely due to the unbalanced data; previous research on this program has demonstrated that the majority of individuals experience at least a 10-point PCL-5 change, with a program-average change of approximately 21 points. It is likely that clinicians were aware of the high rates of symptom reduction in this program and thus may have been more inclined to predict their patients would respond by at least 10 points, which would automatically result in high prediction accuracy. Thus, machine learning models are unlikely to benefit clinicians in determining whether their patients are likely to experience clinically meaningful change in this particular program.

Clinicians’ confidence in making predictions for both outcomes increased over the course of treatment. This was expected, as clinicians had access to more patient data, both from self-report measures and from clinical information they gathered during sessions. In line with the aforementioned findings, confidence ratings were generally higher for predicting a 10-point PCL-5 change compared to predicting whether veterans would end treatment with a PCL-5 score at or below 33. Confidence in making predictions was positively associated with accuracy. We observed differences between clinicians, with some generally making ratings more confidently than others, although analyses did not reveal noticeable differences in clinician factors (e.g. time in profession) that could account for this. It appears that some clinicians are generally more confident than others, or that variables not captured in the present study may account for such differences.

The present study has several limitations that need to be noted. Clinician and patient diversity was limited. Additionally, the number of clinicians who participated in the study was relatively small, and some clinicians did not have many patients. This prevented us from conducting more in-depth analyses looking at clinician-level factors that may have influenced confidence or accuracy ratings. All of the measurements were based on self-reported PTSD symptoms. Although patients were instructed to anchor their symptoms to their index trauma, we were unable to verify this. Moreover, the PCL-5 used in this study assessed past-week PTSD severity, although individuals completed the measure repeatedly during the 2-week program. Although past-week ratings appear to be acceptable even in accelerated treatment formats (Roberge et al., Reference Roberge, Wachen, Bryan, Held, Rauch and Rothbaum2025), the rating timeframe may not have accurately captured the actual symptom change that patients experienced and may have therefore impacted predictions from both the machine learning models and the clinicians. Finally, given that this study was conducted in an intensive treatment setting, the generalizability of our findings to other non-intensive clinical settings, intensive clinical settings with worse outcomes, different staffing models, or patient populations may be limited.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to directly compare machine learning models’ abilities to predict PTSD symptom change and endpoint severity with those of clinicians. Machine learning models outperformed clinicians in predicting whether patients would end treatment with symptom severity indicative of probable PTSD, but they did not perform any better than clinicians in determining whether individuals would experience meaningful PTSD symptom change. Thus, machine learning models can be beneficial in estimating treatment response in some circumstances, and they can do so relatively early. As such, machine learning can potentially assist clinicians and programs in identifying patients at risk of experiencing suboptimal treatment response and provide a basis for evaluating whether treatment adjustments may be beneficial. Additionally, because clinicians’ confidence was positively related to their accuracy, these machine learning models could also be particularly beneficial for clinicians to consult when uncertain about a particular patient’s likelihood of improvement. At the same time, this study also clearly showed that machine learning models are not always better than clinicians with access to self-report measures (Scott & Lewis, Reference Scott and Lewis2015). Going forward, it will be important to evaluate the optimal ways to use machine learning to improve overall PTSD outcomes. Additional research is needed to test different machine learning models and clinics, as many of the existing models are currently clinic-specific and few have been evaluated to determine their performance in other settings. It will be important to conduct similar evaluations as those shown here to ensure that development can focus on tools that can enhance clinicians’ capabilities, not merely duplicate them. An area that warrants future investigation is understanding which information clinicians base their predictions on, as this can also help inform future training to make clinicians better at predicting their patients’ outcomes. Future research should move beyond benchmarking clinicians against machine learning models to the development and validation of individualized treatment rules that can generate actionable recommendations for clinicians who are making treatment decisions. This includes models capable of accurately forecasting outcomes prior to treatment initiation to guide treatment selection and personalization from the outset. In addition, future research should focus on predicting response defined by remission or functional outcomes rather than being solely focused on symptom-specific change, thereby better capturing real-world impacts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102742.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating veterans and their families, as well as acknowledge the administrators, research assistants, and clinicians at the Road Home Program. Philip Held receives grant support from the Department of Defense (W81XWH-22-1-0739; HT9425-24-1-0666; HT9425-24-1-0637), Wounded Warrior Project®, United Services Automobile Association (USAA)/Face the Fight, and the Crown Family Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Defense, Wounded Warrior Project®, USAA, or any other funding agency.

Author contribution

PH: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, writing – original draft; DLS: formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft; DRS: writing – reviewing and editing; SP: data curation, writing – original draft.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.