Introduction

There are no two similar kinds of reindeer. You have to be with the reindeer to learn. When you have worked with him for ten years, you no longer need to study, because you know him, even from every flick of his ear. (H3, cited in Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2022, 105)

Reindeer herding has shaped the worldview of the indigenous Sámi of northern Fennoscandia since the onset of herding more than a thousand years ago. In the present-day Sámi worldview, the world is understood as a relational unity that includes both human and non-human actors, as well as both animate and inanimate actors (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010; Schanche Reference Schanche2000; Tervaniemi & Magga Reference Tervaniemi, Magga, Hylland Eriksen, Valkonen and Valkonen2019). The pastoral Sámi perceive animals, for instance reindeer, as being sentient persons in their own, unique ways (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010). It has also been suggested (based on archaeological evidence of burial and offering practices, for example) that elements of the relational worldview among the Sámi date as far back as the Late Iron Age and Medieval periods (see e.g. Äikäs et al. Reference Äikäs, Puputti, Núñez, Aspi and Okkonen2009; Schanche Reference Schanche2000; Svestad Reference Svestad, Bergsvik and Dowd2018). Such relational worldviews are common among hunter-gatherers and pastoralist peoples across the Arctic, with the particulars varying between cultures (Hill Reference Hill, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018). However, while ethnographic and contemporary participant research clearly indicate that reindeer are sentient creatures for the herders, possessive of agency and personhood, it is also evident that the reindeer are persons in different ways, with their age, gender, physical appearance, personality and other social roles being acknowledged and recognized by the herders who maintain their relationships with animals in different ways within their herding tasks (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). As articulated by a contemporary reindeer herder in Finland, in the quotation with which I began this paper, there are no two similar reindeer—relationships with each and every one of them take shape through interaction and over time, becoming a process of knowing each other.

In past decades, scholarship on non-Western ontologies has made it urgent for archaeologists to re-consider our interpretations of past ontologies, lived-in worlds and relationships between humans and non-humans (Harrison-Buckley & Hendon Reference Harrison-Buckley, Hendon, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018). These studies have made it clear that in many worldviews, ranging from Amazonian to northern Eurasian and beyond, people are perceived to co-inhabit the world with a range of non-human entities, whose capacities to participate in conversations and social interactions vary situationally (e.g. Fienup-Riordan Reference Fienup-Riordan2020; Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010; Kohn Reference Kohn2013; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998; Willerslev Reference Willerslev2007). In acknowledgement of this body of scholarship, current archaeological research often addresses questions related to relational ways of being in the world, exploring agency (the capacity to act), animacy (the state of possessing a life force) and personhood (the capacity to partake in social relationships) of non-human entities (Boyd Reference Boyd2017; Harrison-Buckley & Hendon Reference Harrison-Buckley, Hendon, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Hill Reference Hill2013). Such approaches have explored how, for instance, non-human animals, plants, buildings and objects actively participate in webs of social interaction (e.g. Hendon Reference Hendon, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Herva Reference Herva2010; Hill Reference Hill2013; van der Veen Reference van der Veen2014).

An important research avenue in relational archaeology has focused on the inclusion of animals into webs of social interaction—emphasizing, for instance, the social relations between humans and domesticated species in past agrarian and pastoral economies (see e.g. Armstrong Oma Reference Armstrong Oma2010; Orton Reference Orton2010). Another strain of research has focused on uncovering past animals as individuals with personhood, agency and life histories of their own, mapping the ways in which their lives unfolded and intersected with those of humans (e.g. Losey et al. Reference Losey, Bazaliiskii and Garvie-Lok2011; Salmi & Fjellström Reference Salmi, Fjellström, Whitridge and Hill2024; Tourigny et al. Reference Tourigny, Thomas and Guiry2016). A third line of inquiry has explored how past lived-in worlds have been co-constituted with non-human animals, with this co-constitution unfolding in various practices and engagements with non-human actors (e.g. Brittain & Overton Reference Brittain and Overton2013; Overton & Hamilakis Reference Overton and Hamilakis2013). Reaching beyond species-to-species dyads, multispecies archaeological approaches have embraced relationality to examine the range of non-human creatures included in webs of social interaction and the long-term changes in more-than-human communities (Pilaar Birch Reference Pilaar Birch2018). Moreover, the multiplicity of interweaving relations has been brought forward in ethnoarchaeological approaches—uncovering, for instance, individual and situational relations between hunters and their prey (LeMoine et al. Reference LeMoine, Darwent, Darwent, Helmer, Lange, Whitridge and Hill2024) as well as gendered ways of engaging with non-human entities (Hill Reference Hill, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Nomokonova et al. Reference Nomokonova, Losey, Razdymakha, Okotetto, Plekhanov and Gusev2022). Together, these relational approaches acknowledge that the world has always been co-created together with various things and creatures, and that what is perceived as being alive and possessive of personhood has varied situationally, cross-culturally, as well as within society (Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Hill Reference Hill, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016).

In this paper, I try to tackle the multiplicity of relations in the more-than-human community among the Sámi of northern Fennoscandia in the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries through an archaeological case study. Reindeer pastoralists engaged in varied livelihoods, consisting of hunting, fishing, gathering and small-scale reindeer herding. These Sámi communities interacted not only with ‘reindeer’ as in a homogenous group of animals belonging to a Linnaean taxon, but with a variety of individuals of different ages, genders, social roles and placements on the wild/domesticated axis. I employ zooarchaeological data to show that ancient reindeer herders were in contact with different kinds of reindeer, including wild reindeer, working reindeer and ‘ordinary’ herd reindeer. In addition, I turn to ethnoarchaeological perspectives so as to characterize the variety of these relations. Based on the material evidence on reindeer herding practices, I will ask what kind of meanings and affective qualities characterized these different relations. Ultimately, this paper will examine how the different kinds of reindeer participated in the co-creation of the more-than-human community in this specific time and place in history, contributing to the study of culturally specific past ontologies.

Reindeer herding and human–reindeer relationships among the Sámi of northern Fennoscandia

Reindeer herding plays a vital role both as a livelihood and a cultural tradition for various communities throughout northern Eurasia. Reindeer-herding peoples are distributed across the region, stretching from Fennoscandia in the west to Eastern Siberia in the east (Helskog Reference Helskog2011). While the precise origins of reindeer domestication are still debated among researchers, recent studies suggest that this process likely began in Siberia around the turn of the first millennium (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Harrault, Milek, Forbes, Kuoppamaa and Plekhanov2019; Losey et al. Reference Losey, Nomokonova and Arzyutov2021). The timeline and interrelations of different reindeer-herding traditions are still not fully understood. However, the early dating of the Siberian evidence, combined with archaeologically documented interactions between Sámi groups and Siberian communities during the Iron Age and the overall similarities in herding practices, suggests that Sámi reindeer herding may have been influenced by Siberian practices (Røed et al. Reference Røed, Bjørklund and Olsen2018; Salmi Reference Salmi2023).

In Fennoscandia, the earliest signs of domesticated reindeer herding date to the Late Iron Age, approximately 600–800 ce. Multiple lines of evidence, such as settlement patterns, material culture, zooarchaeology and historical sources, indicate that early Sámi herding (c. 600–1400 ce) was a part of a mixed subsistence system that combined small-scale herding (including working animals) with hunting, fishing and gathering. These activities shaped seasonal movement patterns across the landscape (Salmi Reference Salmi2023; Seitsonen & Viljanmaa Reference Seitsonen and Viljanmaa2021).

A major transformation occurred around the fifteenth century, when Sámi communities shifted towards a mobile pastoralist economy centred on larger reindeer herds. This change probably resulted from a combination of factors, including climatic cooling during the Little Ice Age (c. 1300–1850 ce), the Black Death epidemic in the mid-fourteenth century and the increasing political and economic incorporation of Sámi territories into expanding Scandinavian states (Olsen Reference Olsen, Halinen and Olsen2019; Salmi & Seitsonen Reference Salmi, Seitsonen and Salmi2022; Wallerström Reference Wallerström2000). Although settlement patterns and ancient DNA evidence indicate major changes in herding practices and reindeer populations around this time (Bjørnstad et al. Reference Bjørnstad, Flagstad, Hufthammer and Røed2012; Røed et al. Reference Røed, Bjørklund and Olsen2018; Seitsonen & Viljanmaa Reference Seitsonen and Viljanmaa2021), it is important to note that the transition was not simultaneous across northern Fennoscandia—nor were all Sámi communities involved in it at all. For example, in the forested eastern parts of Fennoscandia, a mixed hunting-herding economy continued among forest Sámi communities well into the twentieth century (Hultblad Reference Hultblad1968; Tegengren Reference Tegengren1952). Despite the changes, there was significant continuity in cultural practices and the relationship with the land (Salmi Reference Salmi2023; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, Äikäs, Spangen, Fjellström and Mulk2018).

Broadly speaking, present-day reindeer herding is practised through reciprocal relationships between herders, the herd and the landscape (e.g. Mazzullo Reference Mazzullo, Stammler and Takakura2010; Stépanoff et al. Reference Stépanoff, Marchina, Fossier and Bureau2017). Although reindeer-herding strategies vary, and have historically varied, across the reindeer-herding area in accordance with local environmental, social and cultural factors, the different modes of herding typically combine the holistic care of the herd in its environment with other subsistence activities (such as gathering, fishing, hunting and farming), as well as trade and craft-making activities (see e.g. Hansen & Olsen Reference Hansen and Olsen2014, 174–231; Hultblad Reference Hultblad1968; Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948; Lundmark Reference Lundmark1982). Herders often strive to maintain a herd composed of animals of varied ages, sizes and types, ensuring resilience in changing environmental conditions (Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Turi and Sundset2007; Mazzullo Reference Mazzullo, Stammler and Takakura2010). Particularly before the late twentieth-century shift towards meat production for a market economy, the reindeer herd was a multi-purpose entity with individuals used for several purposes, such as meat production, reproduction, working, travelling and herd cohesion (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, van den Berg, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2022).

The contemporary Sámi worldview is relational. In it, animals and other non-human beings possess personhood, agency and the ability to communicate with humans (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010). The world is understood as a relational unity of human, non-human and supernatural actors. Landscapes, beings and objects gain meaning through their relationships with people (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010; Schanche Reference Schanche2000; Tervaniemi & Magga Reference Tervaniemi, Magga, Hylland Eriksen, Valkonen and Valkonen2019). Animals, including reindeer, are regarded as persons—sentient beings capable of emotion, intention and forming meaningful ties with humans. However, animal personhood is understood as distinct from human personhood, arising situationally and varying among individuals (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010). Reindeer personhood is especially significant in contexts such as the training of working reindeer (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024).

Theoretical perspectives on studying past ontologies with the aid of traditional knowledge and ethnoarchaeology

As relational approaches have become pervasive in archaeological practice, it is perhaps natural that concerns regarding the ubiquitousness of the term have been raised, calling for more critical understandings of what relational ontologies mean in each cultural context and how we as archaeologists go about studying them (e.g. Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Hill Reference Hill, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016). Moreover, critical thinking on how we study relational ontologies of the past has been called for—after all, if everything is relational, the word risks becoming meaningless and trivial (Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016). In this vein, it has been argued that archaeologists should embrace the variety of ontologies across cultures instead of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of relationality (Harrison-Buckley & Hendon Reference Harrison-Buckley, Hendon, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016). As a possible avenue to more critical and contextually aware relational archaeologies, it has been noted that archaeologists should strive to find ways to delve into culturally and historically specific relational ontologies through case studies (Harrison-Buckley & Hendon Reference Harrison-Buckley, Hendon, Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018). As archaeological studies are usually grounded in specific materialities, this approach is either implicitly or explicitly adopted in most current archaeological practice.

In the study of Arctic prehistory, the ethnographic record and/or traditional knowledge and archaeological evidence have often been considered together to understand how relational worldviews were grounded in materiality in particular cultural contexts (e.g. LeMoine et al. Reference LeMoine, Darwent, Darwent, Helmer, Lange, Whitridge and Hill2024; Losey et al. Reference Losey, Nomokonova and Arzyutov2021; Nomokonova et al. Reference Nomokonova, Losey, Razdymakha, Okotetto, Plekhanov and Gusev2022; Skandfer Reference Skandfer2009). However, in the context of Fennoscandian reindeer herding, ethnographic and participant research usually represent information gathered primarily during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (e.g. Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010; Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948; Soppela et al.2024 Reference Soppela, van den Berg, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2022; Vuojala-Magga Reference Vuojala-Magga, Stammler and Takakura2010). As such, traditional knowledge of reindeer herders is affected by the specific socio-economic and cultural conditions prevailing in modernity, including colonialism, and cannot uncritically be projected onto past reindeer-herding societies (see Politis Reference Politis and Smith2014; Stump Reference Stump2013).

The relationship between the ethnographic and archaeological records has been problematized and discussed in the field of ethnoarchaeology—a field that addresses the theoretical and methodological aspects of acquiring and using ethnographic data in archaeological interpretation (Politis Reference Politis and Smith2014; Stiles Reference Stiles1977). It has been suggested that ethnoarchaeological research should not treat traditional knowledge in the past and traditional knowledge today as the same (Stump Reference Stump2013), and that it should be particularly aware of the effects of Western colonialism on Indigenous societies (Politis Reference Politis and Smith2014). Indigenous cultures and lifeways have never been static, but are in a constant state of change (Schanche & Olsen Reference Schanche, Olsen and Næss1985). On the other hand, traditional knowledge can persist over long periods of time, even under the effect of colonialism, with a high degree of coherence (Smith Reference Smith2012). Skandfer (Reference Skandfer2009) has argued that though particular meanings change over time, present-day Sámi traditional knowledge can be relevant to archaeology because of the continuity between past and present landscape experiences—residing in people who still practise traditional means of livelihood and are socialized into these traditions through stories and practical engagement with the landscape. For Skandfer (Reference Skandfer2009), dismissing traditional knowledge would mean a ‘thinner’ description of the meanings inherent in the archaeological record, with material practices largely being stripped of their meaning.

As a potential way forward, Politis (Reference Politis and Smith2014) suggests that archaeologists should carefully examine the similarities in the relationships between things, practices and concepts between past and present societies. This view is echoed in Van Oyen’s (Reference Van Oyen2016) and Harris’ (Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021) calls for approaches focusing on critical examination of sets of relations as a way forward for relational archaeology. They recommend description of sets of relationships and how they were ordered, as well as description of the affective qualities of these relations as critical ways to address past relational ontologies (Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016). Moreover, description of how relations are grounded in action and materiality is needed for archaeologists to begin to understand meaningful connections of relations in past societies (Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016).

My approach in this paper is based on the view that present-day reindeer herding encompasses traditional practices and knowledge systems adapted to the requirements of the modern world (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). Reindeer herders themselves think of reindeer-herding practices, such as draught reindeer use, as important bearers of reindeer-herding culture (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi and Wallén2020). Moreover, despite cultural and linguistic differences across Eurasia, there are broad similarities in relating to the reindeer and herding landscapes, emphasizing the autonomy of the reindeer and sharing the landscape with them (Mazzullo Reference Mazzullo, Stammler and Takakura2010; Stépanoff et al. Reference Stépanoff, Marchina, Fossier and Bureau2017). These types of broad relations, rather than exact details and specific meanings, are, in my view, useful for the interpretation of material practices which we can access through the archaeological record. I will therefore examine the relations emerging from the archaeological record—hunting and herding, for instance—and consider the possible meanings of these varying degrees of interaction in the light of ethnographic data and traditional knowledge. Much like Skandfer (Reference Skandfer2009), I see ethnographic data and traditional knowledge as ways to get a glimpse of the potential ways to engage practically and emotionally with the reindeer.

Archaeological sites

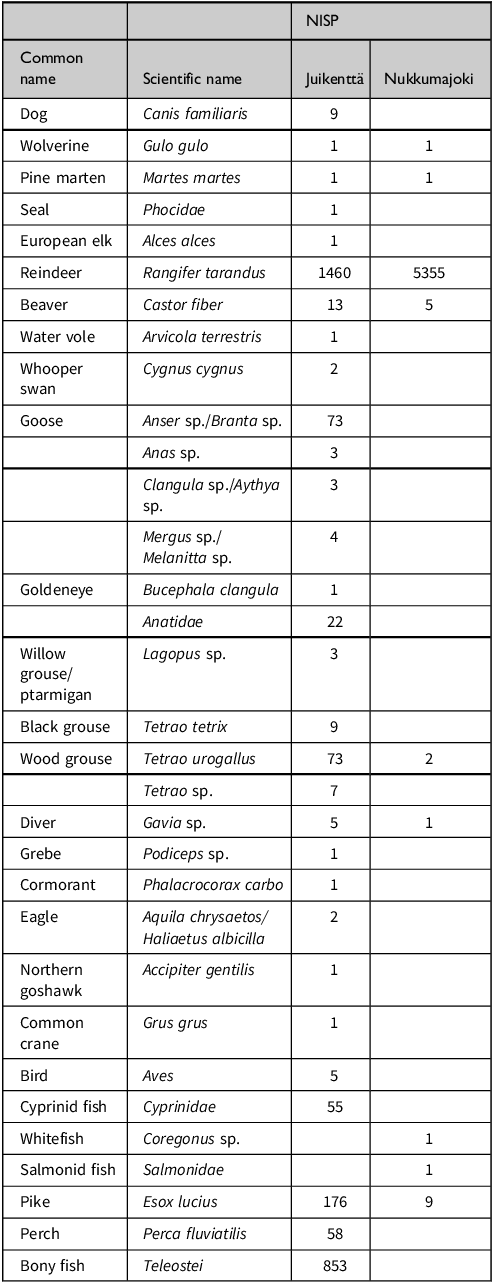

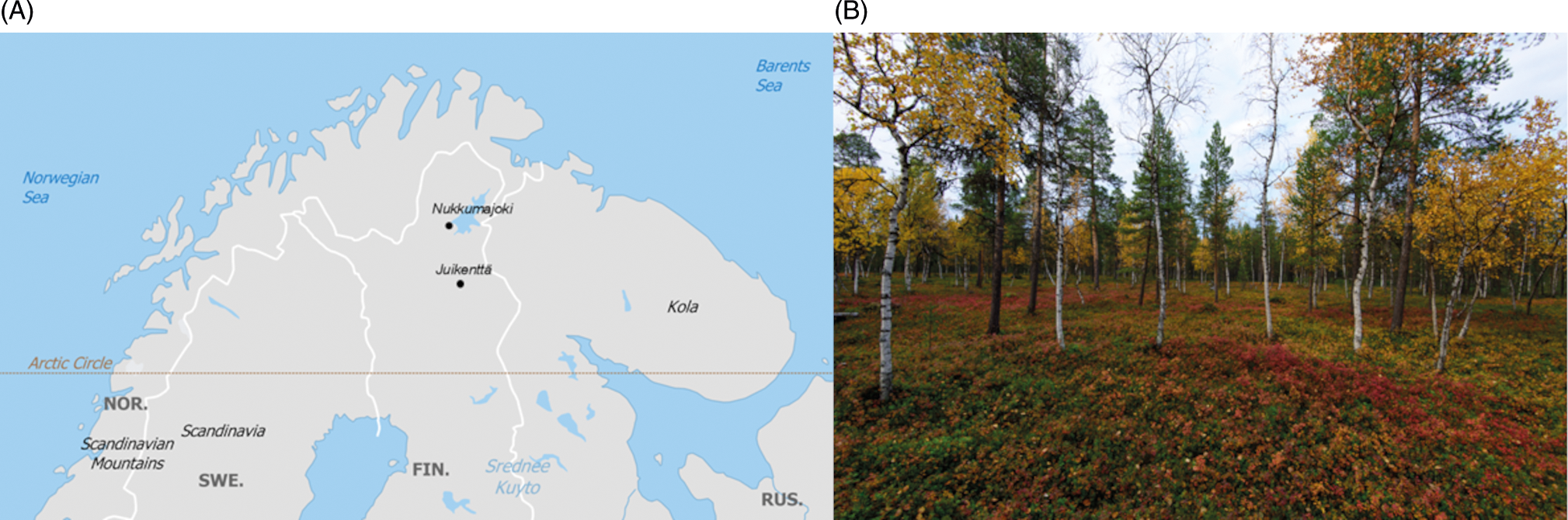

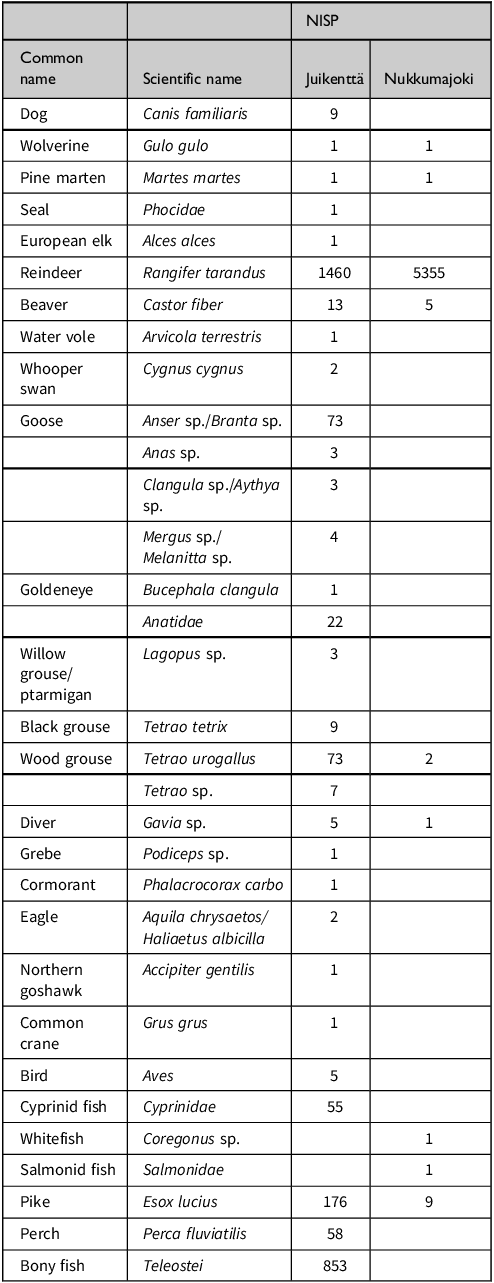

The faunal assemblages addressed in this paper come from two archaeological sites located in present-day northern Finland: Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki (Fig. 1). Both sites are Sámi dwelling sites, with the faunal assemblages dating between c. 1300 and 1650 ce (Carpelan Reference Carpelan1993; Carpelan et al. Reference Carpelan, Jungner and Mejdahl1990; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). Analyses of the faunal assemblages have been published in Harlin et al. (Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019); the results are compiled in Table 1.

Figure 1. (A) Map of northern Fennoscandia and the locations of Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä; (B) A view over the Nukkumajoki site. (Photograph: V. Laulumaa 2015. Arkeologian kuvakokoelma, Digikuvakokoelma, Finnish Heritage Agency).

Table 1. Numbers of identified specimens (NISP) in the faunal assemblages from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki. Data from Harlin et al. (Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). See Harlin et al. (Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019) for full details of bird taxonomic identification.

Juikenttä is located in the municipality of Sodankylä. A Sámi dwelling site interpreted as a forest Sámi summer village, it was occupied c. 1500 bce–1650 ce. The faunal remains investigated originate from five dwellings (goahti in North Sámi) and date to c. 1050–1650 ce, based on typological features of the material culture (Carpelan Reference Carpelan1993), with radiocarbon dates falling between 1292 and 1662 ce (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). The faunal material was dominated by reindeer bones, with a little more than 50 per cent of the number of identified specimens belonging to reindeer (Table 1; Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). Age estimations based on dental eruption and wear and epiphyseal fusion show that mostly young adult individuals were slaughtered (Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). In addition to reindeer, a range of other species were identified, such as domestic dog, various fur-bearing mammals, wild forest and water birds and freshwater fish (Table 1; Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). The bones of migratory water birds show that the site was probably inhabited in the period from spring to autumn. Fish bones testify to freshwater fishing, usually a summertime activity (Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019).

Nukkumajoki, located on the shore of the Nukkumajoki River, belongs to a series of winter villages. Radiocarbon dating indicates a probable occupation period between c. 1400 and 1660 ce (Carpelan 1991; Reference Carpelan and Lehtola2003; Carpelan et al. Reference Carpelan, Jungner and Mejdahl1990). The faunal assemblage discussed here originates from ten dwellings (goahti) and several fireplaces (Carpelan Reference Carpelan and Lehtola2003). It consisted overwhelmingly of reindeer bones, with approximately 99 per cent of the number of identified specimens belonging to reindeer (Table 1; Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). Age estimations indicate that mostly adult animals were slaughtered, although some sub-adult individuals were also present (Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019). Other identified taxa were pine marten, seal, beaver, capercaillie, diver, whitefish, salmonid and pike (Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019).

Identifying the kinds of reindeer at Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki

The importance of reindeer in the culture and economy of the Sámi communities inhabiting Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki is evident from the archaeological evidence. For a more nuanced understanding of the hunting and herding practices and herd compositions characterizing these communities, a series of detailed osteological and morphometric analyses has been undertaken in recent years. Several methodological avenues, such as osteometric and geometric morphometric analyses, palaeopathology and the analysis of physical activity markers have been explored to distinguish and identify the variety of reindeer that people inhabiting Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki interacted with, with detailed analyses published in Salmi et al. (Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021), Hull et al. (Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023) and Pelletier et al. (Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023).

Osteometric measurements and geometric morphometrics have been utilized to disentangle the effects of ecotype and sex on reindeer bone size and shape (Pelletier et al. Reference Pelletier, Kotiaho, Niinimäki and Salmi2021a Reference Pelletier, Kotiaho, Niinimäki and Salmi2020;, b; Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023; Puputti & Niskanen Reference Puputti and Niskanen2009; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021; van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Wallen and Salmi2023). Although the overlapping body sizes and bone measurements of wild forest reindeer and domesticated or mountain reindeer hinder the interpretive potential of osteometric analyses in terms of ecotype and sex differentiation, the metric analysis of reindeer bones from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki indicate that both ecotypes were present in the faunal assemblages (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). However, due to the extensive overlap of the measurements, any proportions beyond probable presence are impossible to estimate based on osteometric analysis. The range of the osteometric measurements also indicated the probable presence of male and female animals in the assemblages, although precise sex assessments could not be made due to the confounding effect of ecotype (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021).

Geometric morphometric analysis, on the other hand, is suited for statistically assigning specific samples to a group. Thus, the analyses of reindeer lower molars from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki were more suitable for estimating the approximate numbers of animals belonging to each ecotype in the assemblages (Pelletier et al. Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023). According to these results, approximately 15 per cent of all molars from these sites assigned to an ecotype belonged to wild forest reindeer and 85 per cent to mountain reindeer or domesticated reindeer (Pelletier et al. Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023). Due to the location of both sites in the boreal forest zone, domesticated reindeer is a more probable classification than wild mountain reindeer. Site-level differences are difficult to assess, due to only one mandibular fragment with molars from Juikenttä being assigned to an ecotype (wild forest reindeer). In the Nukkumajoki assemblage, the percentages of mountain/domesticated reindeer and wild forest reindeer were 72 per cent and 28 per cent respectively (Pelletier et al. Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023).

In addition to ecotype and sex assessment, identification of working reindeer based on palaeopathology and muscle and tendon attachment site morphology has been undertaken for the reindeer bone assemblages from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). The results of palaeopathological analysis showed that pathological lesions typical to modern working reindeer were present in both faunal assemblages. Moreover, these lesions were located on the same skeletal elements they typically are located on for modern working reindeer, and the distribution of severity scores of phalangeal pathological lesions was similar to that for modern working reindeer (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). Thus, palaeopathological analysis clearly indicates that working reindeer were present in both assemblages; however, any numbers or percentages of working individuals of the whole herd are not available based on palaeopathological analysis (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021).

A detailed analysis of entheseal changes in the archaeological reindeer phalanges offered some additional insights into the use of working reindeer in Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki. The statistical comparison of entheseal changes in modern and archaeological reindeer phalanges confirmed the presence of working reindeer at both sites (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023). Moreover, the analyses showed differences between the sites, with the Juikenttä assemblage containing a relatively larger number of phalanges assigned to working reindeer (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023). Although the share of working reindeer phalanges in a faunal assemblage does not directly represent the shares of working reindeer individuals in the herd, the overall trend is indicative of differential emphasis in herding strategies at these sites (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023).

Radiocarbon dates provide additional clues to the co-existence of different kinds of reindeer at the sites. Two phalanges with working-typical pathologies from Juikenttä were dated to 1292–1422 ce, possibly indicating the presence of working reindeer at the site already at that time (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021). A phalanx with entheseal changes showing that it probably belonged to working reindeer from Juikenttä dated to 1421–1616 ce. Another phalanx from Juikenttä, dated to 1292–1400 ce, was consistent with wild forest reindeer (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023). In Nukkumajoki, one phalanx dating to 1492–1662 ce was assigned to a domestic uncategorized/herded animal, and one phalanx dating to 1515–1798 ce to a wild forest reindeer (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023).

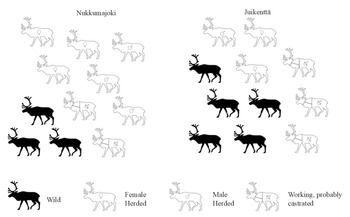

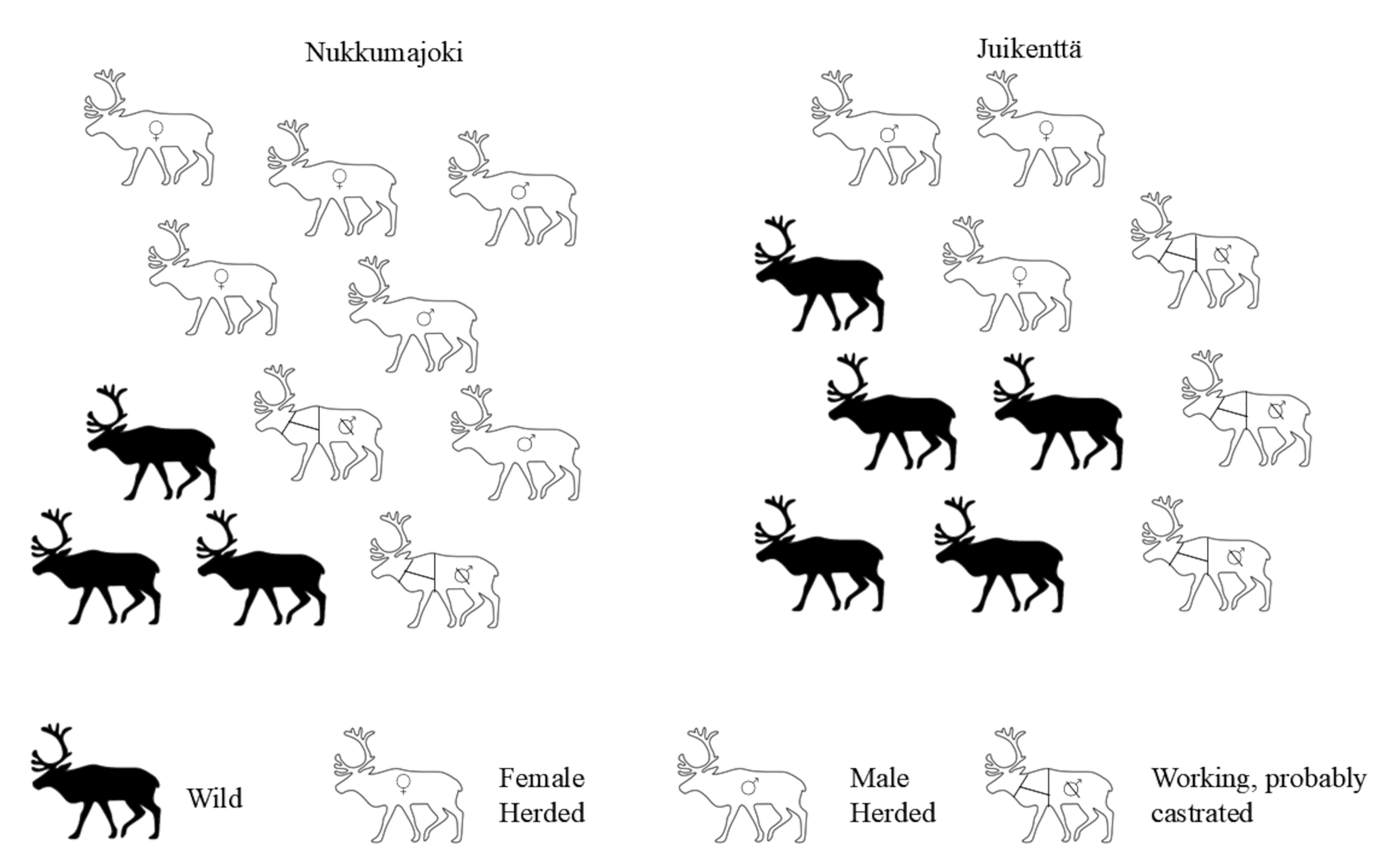

Thus, the osteological analyses show that the Sámi communities occupying Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki interacted with different kinds of reindeer within the same temporal frame (Fig. 2). Wild forest reindeer and domesticated reindeer were probably present at both sites. Moreover, male and female animals were probably present. Physical activity-related skeletal changes indicate that working reindeer belonged to the reindeer-herding strategy of the occupants of both sites. Together with the overall species frequencies in the faunal assemblages, these parameters act as evidence of a mixed subsistence pattern where hunting and fishing were practised alongside reindeer herding, a typical way of life for the forest Sámi communities also in later centuries (Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019; Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023; Pelletier et al. Reference Pelletier, Discamps, Bignon-Lau and Salmi2023; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, van den Berg, Niinimäki and Pelletier2021).

Figure 2. The approximate composition of the reindeer bone assemblages from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki based on osteometric, geometric morphometric, palaeopathological, and physical activity analyses. The numbers of different types of reindeer do not represent exact proportions but rough estimates of the relations between group sizes.

Inter-site comparisons imply that, although hunting and herding were practised by the occupants of both sites, hunting, fowling and fishing were probably more prominent means of livelihood at Juikenttä than at Nukkumajoki, where a stronger emphasis was put on reindeer herding, including working reindeer use. It is possible that Juikenttä had more mixed subsistence practices than Nukkumajoki. In the light of present evidence, it is unclear whether the observed differences are due to seasonal, temporal or regional variation in reindeer-herding practices. Though the occupation of Juikenttä seems to go back further in time than Nukkumajoki, the radiocarbon dates overlap considerably. The sites are in territories of different siidas—family-based groups that shared the same subsistence pattern and territory—as the borders were located in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. However, both sites are in the region historically inhabited by the forest Sámi, thus probably sharing a broadly similar subsistence pattern (e.g. Näkkäläjärvi Reference Näkkäläjärvi, Pennanen and Näkkäläjärvi2000). It is possible that the sites represent seasonal activities of two communities sharing a similar subsistence pattern—with Juikenttä representing summer activities such as fowling and fishing, while Nukkumajoki represents the wild reindeer hunting and herded reindeer slaughtering of the cold season (Carpelan et al. Reference Carpelan, Jungner and Mejdahl1990; Harlin et al. Reference Harlin, Mannermaa, Ukkonen, Mannermaa, Manninen, Pesonen and Seppänen2019; Hull et al. Reference Hull, Salmi and Semeniuk2023).

The variety of life on the hoof

As shown above, the variety of life teeming around the people who occupied Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki in the centuries gone by can to some extent be documented with the aid of archaeological data. The cultural meanings of these archaeologically traceable forms of life, however, need a more multifaceted set of evidence than osteology alone to be examined properly. In what follows, I will investigate the possibilities of a combination of archaeology, ethnography, historical data and traditional knowledge of reindeer herders to characterize the relations and emotions that may have prevailed between people and the variety of life on the hoof. By examining how these relations were grounded in action and materiality of reindeer hunting and herding in fourteenth- to seventeenth-century eastern Fennoscandia, we can begin to understand what kind of emotions and meanings were attached to their relations, and how the various hoofed creatures participated in more-than-human society in this specific time and place.

Vibrant hunting and herding landscapes

First, the archaeological evidence shows that the occupants of Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki engaged with both wild and domesticated reindeer. Both these communities practised a mixed subsistence of small-scale reindeer herding, hunting, fishing and gathering. In this type of reindeer-herding strategy, the reindeer herds were usually small—perhaps fewer than ten animals per herder, as indicated by the Swedish Crown’s reindeer count from the region in the early seventeenth century (Hultblad Reference Hultblad1968). The small numbers of animals were probably individually known to their herders, with people sharing the landscape with them in varying herding activities. Archaeological evidence speaks of some of these seasonal herding tasks: for instance, stable isotope evidence suggests that supplementary winter feeding was also occasionally practised in the region at the time of the inhabitation of Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki (Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, Fjellström, Äikäs, Spangen, Núñez and Lidén2020). Moreover, there is evidence of wooden fences being used, probably to round the reindeer up for counting, marking and castration, as well as for selecting animals for slaughter in the autumn, in the forested zone of Fennoscandia at least from the seventeenth century onward and possibly earlier (Leem [1767] Reference Leem1956; Norstedt et al. Reference Norstedt, Rautio and Östlund2017; Zetterberg et al. Reference Zetterberg, Eronen and Briffa1994).

This archaeological evidence points to some of the ways in which human–reindeer relationships were grounded in the material practices of the inhabitants of Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki. In present-day reindeer herding, practices such as roundups and supplementary feeding are understood as parts of holistic care of the herd in the landscape. Herders protect the reindeer, monitor their well-being and guide them to good pastures (Mazzullo Reference Mazzullo, Stammler and Takakura2010; Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). On the other hand, reindeer herders also appreciate autonomy, intelligence and the active agency of the reindeer (Dwyer & Istomin Reference Dwyer and Istomin2008; Mazzullo & Soppela Reference Mazzullo, Soppela, Strauss-Mazzullo and Tennberg2023; Stépanoff et al. Reference Stépanoff, Marchina, Fossier and Bureau2017). It can be seen that reindeer and herders share a landscape where they both modify their behaviour to learn to live together (Stépanoff Reference Stépanoff2017). The probable reindeer-herding practices of the inhabitants of Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä—supplementary reindeer feeding and small-scale herding inclusive of seasonal roundups—would have required attentiveness to the needs of the reindeer on one hand, and (on the other) a considerable degree of independence on the part of the reindeer. Therefore, these practices imply broadly similar relations between reindeer, people and the landscape as in present-day reindeer herding. The material realities of reindeer herding in this region in the medieval and early modern period thus speak of negotiation of human–reindeer relationships in a constant push and pull of care and independence, of intimacy and distance.

The Sámi languages differentiate between wild (goddi in North Sámi) and domesticated reindeer (boazu in North Sámi); these categories are flexible, however, with the degree of domestication of the boazu varying and the different modes of livelihood overlapping in the landscape (Bjørklund Reference Bjørklund2013; Magga et al. Reference Magga, Oskal and Sara2001). Present-day Sámi hunters know their prey intimately and personally. In the context of the hunt, they can transcend species boundaries, communicate with the animals and form interpersonal relationships with them (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010). Moreover, relationships with the land and animals are constructed in active and reciprocal interaction with them (Helander-Renvall Reference Helander-Renvall2010; Tervaniemi & Magga Reference Tervaniemi, Magga, Hylland Eriksen, Valkonen and Valkonen2019). The word for land, meachhi (North Sámi), for example, means ‘forest’, but is also used in a broader sense to mean an area that people do not inhabit but which they engage with in their seasonal activities. It therefore gains its meaning relationally when people engage with it (see e.g. Schanche Reference Schanche2000; Tervaniemi & Magga Reference Tervaniemi, Magga, Hylland Eriksen, Valkonen and Valkonen2019). Traces of similar holistic relationships to the land and its animals are present in ethnographic data from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, showing that hunting was imbued with ritual actions and spiritual meaning—bear hunting, for instance, was an essential part of the special relationships between bears and people (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948, 14–16; Mebius Reference Mebius2003).

Historically, Sámi wild reindeer-hunting techniques consisted of both active and passive methods—including hunters on skis driving the reindeer towards pit or fence systems or natural features such as lakes, as well as trailing the animals to shoot them with bow and arrow or a firearm (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948, 12–40). The archaeological finds from Nukkumajoki indicate the prevalence of both bow-and-arrow and firearm hunting (Carpelan Reference Carpelan and Lehtola2003; Fig. 3). It is also possible that people at Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä practised pitfall hunting, though there is currently no dated archaeological evidence of it near the sites (Halinen Reference Halinen2025, 264–5). The material evidence thus indicates hunting by firearms, bow and arrow, and potentially pitfall systems—with all methods entailing short-term encounters with the wild reindeer. However, although the encounters were shorter in duration than those between humans and domesticated reindeer, they were probably culturally and socially meaningful—after all, it has been argued that hunting often entails intimate relationships between human and animal persons, not without close interaction and dialogue (Anderson Reference Anderson2012; Hill Reference Hill2013; Willerslev 2007; Reference Willerslev2012). Among the medieval and early modern Sámi, an active reciprocal relationship between people, animals and the land is evident—for instance, in the archaeological evidence of religious rituals of the Sámi, wherein the reciprocity was acted out via animal offerings given at sacred sites (Äikäs Reference Äikäs2015; Mulk Reference Mulk and Äikäs2009; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, Äikäs, Spangen, Fjellström and Mulk2018). At some of these offering sites, for instance in the Koskikaltionjoensuu offering site in Inari, wild and domesticated reindeer were offered within the same period (Heino et al. Reference Heino, Salmi and Äikäs2021), emphasizing how both hunting and herding were acted out in a reciprocal relationship with the land and the creatures inhabiting it.

Figure 3. An arrowhead from Nukkumajoki 2. KM20837:33. (Arkeologian esinekokoelma, Finnish Heritage Agency).

An adaptable herd in a changing world

In past reindeer herding, before the modern market economy steered reindeer herders predominantly towards meat production, diverse herds were valued, allowing adaptability and various functions (Beach Reference Beach1993; Paine Reference Paine1994). A herd that has animals of different ages, sizes and types of reindeer is still considered a beautiful herd or čappá eallu (North Sámi) by the herders. The variability within the herd improves its adaptability with respect to changing conditions (Mazzullo Reference Mazzullo, Stammler and Takakura2010; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Turi and Sundset2007). For instance, the behaviour of castrates keeps the herd calm and helps the herders keep the herd together (Paine Reference Paine1988; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Turi and Sundset2007). Males and castrates also guard the herd from predators and help other reindeer dig lichen under hard snow cover in the winter (Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Turi and Sundset2007). Female reindeer are needed for herd continuity (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). Moreover, herders pay close attention to female lineages, believing, for instance, that mothers can teach preferrable behavioural traits to their calves (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024).

The pastoral Sámi had a rich reindeer vocabulary, with dozens of words for different kinds of reindeer. Ethnographer T.I. Itkonen (Reference Itkonen1948, 96), for instance, noted that an experienced herder could remember hundreds of reindeer individually, both his own reindeer and those of others. The vocabulary distinguishes reindeer based on age, sex, antler characteristics, fur colour and quality, body type, character, family relationships and many other characteristics and features (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948, 96–115). Ethnographic evidence also shows that the herders gave names to some, but not all, reindeer. According to Itkonen (Reference Itkonen1948, 111), only a few selected individuals in a big herd would have names—typically, the named individuals were castrated males used for draught, whereas only a few females were named, and full males were ‘hardly ever talked about’. Some reindeer would be named as calves, whereas others would receive a name later in life (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948, 111). The differential degrees of familiarity with reindeer within a herd have also been observed in other reindeer-herding cultures in the present (Takakura Reference Takakura, Stammler and Takakura2010). In addition to naming practices, the degrees of familiarity are clear in the way in which contemporary reindeer herders in Finland talk about ‘tavanporo’ (an ordinary reindeer in the herd), ‘tuntoporo’ (a known reindeer) or ‘ajokas’ (a draught reindeer) (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024).

Within the domesticated herds in Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä, there was variation in terms of age, sex and social roles of the reindeer: zooarchaeological and morphometric analyses show the presence of female, male and possibly castrated reindeer of different sizes and ages. The exact vocabularies people used for this variation remain unknown, as do the precise social roles these individuals may have held. However, these reindeer would have had their species-, age- and sex-typical ecological and behavioural characteristics, which were undoubtedly observed closely by the herders, particularly because the herds were probably small. The ethnographic evidence gives us opportunities to imagine what those social roles may have been like (for example, regarding the association between herd continuity and female reindeer), and the herd cohesion-keeping capabilities of castrates may have been acknowledged by and culturally meaningful to past herders. There were also likely to be different degrees of familiarity between people and reindeer holding various social roles. The degrees of closeness would have been born out of and maintained through engagements and encounters, such as care, feeding and working together in various reindeer herding tasks.

Moreover, the ethnographic and traditional knowledge about the adaptability of a varied herd prompts us to wonder how the adaptive capabilities of the herd may have been valued in the past. At the time Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki were inhabited, roughly from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, the Sámi were facing environmental and societal changes profoundly affecting economy and society. These included at least the possible overhunting of wild reindeer (Hansen & Olsen Reference Hansen and Olsen2014, 204), the cooling of the climate during the Little Ice Age, effects of the Black Death plague pandemic (Seitsonen Reference Seitsonen2020; Sommerseth Reference Sommerseth2011; Storli Reference Storli1996), and the expansion of the power of the emerging states of Sweden, Norway and Novgorod (present-day Russia) into the region through increased trade, taxation and Christianization (Carpelan Reference Carpelan and Lehtola2003; Olsen Reference Olsen, Halinen and Olsen2019; Storli Reference Storli1996). The changes which these factors inflicted were variable between regions and are visible in, for instance, changes in settlement patterns and ritual practices of the Sámi at large as well as in the development and spread of mobile reindeer pastoralism with larger reindeer herds and a herding-focused economy (see e.g. Halinen Reference Halinen, Uino and Nordqvist2016; Salmi et al. Reference Salmi, Äikäs, Spangen, Fjellström and Mulk2018; Seitsonen & Viljanmaa Reference Seitsonen and Viljanmaa2021; Sommerseth Reference Sommerseth2011). In eastern Fennoscandia, where hunting, fishing and gathering retained their importance throughout this period, the changed societal conditions were nevertheless seen in the development of settlement sites like Nukkumajoki—these sites, featuring linear hearth rows, carried on the previous tradition of linear hearth row sites, but were probably winter villages organized from the outside to allow the taxation of the mobile hunter-herder population (Carpelan Reference Carpelan and Lehtola2003; Halinen Reference Halinen, Halinen and Olsen2019; Wallerström Reference Wallerström, Spangen, Salmi, Äikäs and Fjellström2020). The archaeological evidence shows that reindeer herding, hunting, fowling and fishing were practised in dynamic, seasonally varied ways by the Sámi communities inhabiting Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä. Perhaps a variable herd was also a valuable tool for adapting to the changing environmental and social conditions of the time.

Working, being, and learning together

Working reindeer have been an important part of the variable herd in many reindeer herding strategies (Fig. 4). The relationships between herders and working reindeer are often long-term, continuing across several seasons and years. These long-term relationships are based on mutual trust, knowing each other and emotional bonds (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024; Vuojala-Magga Reference Vuojala-Magga, Stammler and Takakura2010). During training, the herders closely observe reindeer behaviour in different situations, making interpretations about the reindeers’ personalities and the suitability of the reindeer for working (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). The herders often use the word ‘luonne’ in Finnish (‘character’ or ‘personality’), referring to the reindeer’s temperament and individual way of reacting (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). Working reindeer personality is also interwoven with its agency, as in the herders’ accounts and stories, the individual motivations and emotions of the reindeer are seen as the basis for their actions and decisions. They thus possess considerable agency, played out in individual ways based on the reindeer’s personality (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024).

Figure 4. Harnessed reindeer bulls, Utsjoki, Finland. (Photograph: J. Heinonen 1955. Suomalais-ugrilainen kuvakokoelma, Finnish Heritage Agency).

Trust is another important component of the human–working reindeer relationship. Trust is built over a long period of time in regular interaction with the reindeer and the process is different every time, but the herders often describe key moments in this process—such as the first time the reindeer agrees to walk on a leash, and the moment of ‘imprinting’ or ‘domestication’, as the herders call it, when the reindeer begins to trust and seek protection from the herder (Soppela et al.2024) Reference Soppela, van den Berg, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2022;. In addition to trust, there are various mutual emotions at play in the relationship between working reindeer and their trainers. These relationships are often conceptualized in terms of collaboration, mutual care and affection in a way that recognizes the emotions of both the human and reindeer participants (Salmi et al. in press). In the training process, mutual attuning to each other’s emotions is seen as important (Vuojala-Magga Reference Vuojala-Magga, Stammler and Takakura2010). Moreover, feelings of joy on one hand, and sorrow at the loss of a companion on the other, are often integral to the human–working reindeer relationship. The way the herders tell stories about their working reindeer reflects meaningful emotional bonds as well as cultural ideas of reindeer herding, working reindeer use and human–animal relationships (Salmi et al. in press).

Zooarchaeological evidence indicates the presence of working reindeer in the domestic reindeer herds in Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki. There is also other archaeological and historical evidence pointing towards variable uses for working reindeer around the period Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki were inhabited. Already from the tenth century onwards, gieres (North Sámi) type of sleds were used (Svestad Reference Svestad, Bergsvik and Dowd2018). Later ethnographic evidence indicates that such sleds were used to transport people and things during seasonal mobility, reindeer-herding tasks and trade journeys by the Sámi (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1948, 388–412). Moreover, historical sources from the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries, as well as and later historical sources, describe the use of draught and cargo reindeer among the Sámi (e.g. Magnus [1555] Reference Magnus1996; Rheen [1671] Reference Rheen1897; Schefferus [1674] Reference Schefferus1979; Tornaeus [1672] Reference Tornaeus and Wiklund1900). In the archaeological material from Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki specifically, in addition to the osteological analyses, the only direct link to working reindeer use from the sites is metal harness pieces discovered from Nukkumajoki, most likely pointing towards draught use (Carpelan 1991; Reference Carpelan1993).

Working reindeer-training practices have been versatile—the details of (for instance) technological solutions, the starting age of training and the purpose of working reindeer use have varied between herders and regions as well as across time. Therefore, the exact cultural meanings and emotions working reindeer use entailed for people in Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä cannot be accessed via archaeological data. However, there were similarities of relations between modern and ancient working reindeer use—for example, regardless of the technical details, training a working reindeer takes time, and also requires frequent interaction between the reindeer and the trainer (Soppela et al. Reference Soppela, Kynkäänniemi, Wallén and Salmi2024). Training also demands mutual learning, enskilment and emotional attuning with another sentient creature (Losey et al. Reference Losey, Nomokonova and Arzyutov2021; Vuojala-Magga Reference Vuojala-Magga, Stammler and Takakura2010). Moreover, working relationships with animals are laden with emotions (Kaarlenkaski Reference Kaarlenkaski2014; Leinonen Reference Leinonen2013; Salmi et al. in press). We can only guess at the exact emotional register related to working reindeer use in Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä, but I believe we can claim that an emotional framework based on close interaction, mutual learning and intimate knowledge of each other formed the basis of the relationship between the reindeer and the trainer. In these types of relations, the reindeer’s and the trainers’ individual personalities were likely to be important parts in how their relationships shaped out to be.

Conclusions

In this paper, I have attempted to delve into the variety of life on the hoof among Sámi reindeer herders in the period roughly between 1300 and 1660 ce. By relying on a range of zooarchaeological results, this paper has shown that the reindeer herd was not only a homogeneous mass of animals, but consisted of animals with different characteristics, behaviours, purposes and social roles. Zooarchaeologically identifiable groups of animals include reindeer of different ages and sexes, as well as working reindeer used for pulling and carrying things. Moreover, wild reindeer were hunted. The relationships between people and these different types of reindeer were grounded in specific materialities, cultural practices and interactions.

The reindeer herding practised by the inhabitants of Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä was probably small-scale herding combined with hunting, fishing and gathering. Herding practices were likely to be seasonally varied, including supplementary feeding, working reindeer training and use, and roundups for counting, slaughtering and other purposes. Using ethnographic data and reindeer herders’ traditional knowledge, I have argued that elements of care and independence probably characterized the human–domesticated reindeer relationship for the medieval and early modern Sámi living at these sites. The relationships between people and wild reindeer, although shorter in interaction duration, were also culturally and socially meaningful. Moreover, both hunting and herding occurred in the framework of reciprocal relationships between people and the land.

Within the domesticated herds in Nukkumajoki and Juikenttä, there was variation in terms of age, sex, and social roles of the reindeer. The ethnographic evidence gives us opportunities to imagine what those social roles may have been like—for example, regarding the association between herd continuity and female reindeer. Also the herd cohesion-keeping capabilities of castrates may have been acknowledged and culturally meaningful to past herders. There were also likely to be different degrees of familiarity between people and reindeer holding various social roles. The degrees of closeness would have arisen from and been maintained through engagements and encounters, such as care, feeding and working together in various reindeer-herding tasks. Working together with the reindeer, in particular, requires time, frequent interaction, mutual learning and emotional attuning with one another. I have used reindeer herders’ traditional knowledge to argue that the relationships between working reindeer and their trainers at Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki were based on an emotional framework characterized by closeness, mutuality and intimate knowledge of each other.

Finally, at the time Juikenttä and Nukkumajoki were inhabited, Sámi societies were experiencing a possible decrease in numbers of wild reindeer due to overhunting, climatic cooling, effects of the Black Death plague pandemic, and the expansion of the power of Sweden, Norway, and Novgorod (present-day Russia) into the region through increased trade, taxation and Christianization. While these pressures inflicted changes on the society, economy and reindeer-herding practices of the Sámi, the animal bone evidence from the sites shows how Sámi communities also adjusted to local environmental and socio-cultural conditions, practising reindeer herding, wild reindeer hunting, fowling and fishing in various combinations in nuanced, seasonally varied ways. A reindeer herd with individuals with different characteristics, behaviours and social roles would have been adaptable, and the variability of life on the hoof therefore being important for the survival of reindeer herding in a changing world.

The use of ethnographic data and traditional knowledge in interpretation of archaeological data from an earlier era is not straightforward, and we probably must accept that exact meanings and emotions imbued in past human–reindeer relationships will remain unknown. However, such knowledge, used cautiously, enriches and thickens archaeological interpretations of past ontologies, shedding light on possible relations and affect-based frameworks. By grounding our interpretations on materiality and practices, we can begin to understand the relational ontology among the Sámi reindeer herders of the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries, contributing to the study of culturally, spatially and temporally specific relational ontologies.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 756431) and the Academy of Finland (project number 308322). I wish to thank all the researchers working in the Domestication in Action project whose work has contributed to the results presented and cited in this article.