Introduction

Detailed knowledge about the geographic distribution of threatened species is critical for the evaluation of their conservation status, and then for active management (Guisan et al. Reference Guisan, Tingley, Baumgartner, Naujokaitislewis, Sutcliffe, Tulloch and Buckley2013, Gedeon et al. Reference Gedeon, Rodder, Zewdie and Topeer2018). However, obtaining such information through intensive field surveys is time consuming and costly. Further, when and where field surveys take place can be limited by difficult climatic conditions or by areas that are topographically inaccessible or politically sensitive, such as transboundary areas (Goodale et al. Reference Goodale, Stern, Margoluis, Lanfer and Fladeland2003). An alternative way to obtain information on species’ ranges is through species distribution models (hereafter SDMs). By quantifying the relationships between environmental predictor variables and the occurrence data of the species, SDMs can produce an empirical model of the habitat conditions that the species requires, a model that can then be projected over a large region (Guisan and Thuiller Reference Guisan and Thuiller2005, Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Anderson and Schapire2006, Elith and Leathwick Reference Elith and Leathwick2009), including inaccessible areas such as in transboundary zones. Indeed, SDMs have been widely used in ecology and conservation for the last decade, including studies of a variety of animal taxa, including birds (Walther et al. Reference Walther, Schaffer, Van Niekerk, Thuiller, Rahbek and Chown2007, Hu and Liu Reference Hu and Liu2014, De Lima et al. Reference De Lima, Sampaio, Dunn, Cabinda, Fonseca, Oquiongo and Buchanan2017), mammals (Newbold et al. Reference Newbold, Gilbert, Zalat, Elgabbas and Reader2009), amphibians (Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Raxworthy, Nakamura and Peterson2006, Eduardo and Jorge Reference Eduardo and Jorge2009), and other taxa (Guisan and Thuiller Reference Guisan and Thuiller2005).

The performance of SDMs for a given species is affected by the model that is applied and an array of factors. Different types of SDM have different requirements for data and sample sizes (Stockwell and Peterson Reference Stockwell and Peterson2002, Elith et al. Reference Elith, Graham, Anderson, Dudik, Ferrier, Guisan and Zimmermann2006, Guillera-Arroita et al. Reference Guillera-Arroita, Lahozmonfort, Elith, Gordon, Kujala, Lentini and Wintle2015). For those rare species with few occurrence data, maximum entropy modeling has good predictive power, is not particularly sensitive to sample size, and requires presence data only, which is much easier to acquire (Wisz et al. Reference Wisz, Hijmans, Li, Peterson, Graham and Guisan2008). Maximum entropy modelling is often implemented in the software MaxEnt (Phillips and Dudík Reference Phillips and Dudík2008). Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Graham, Master and Albert2006), in an investigation of 18 species in different taxa, tested four types of predictive models and found that MaxEnt had the best performance. At the same time, factors such as species dispersal capacity, geographic barriers and historical events also affect the robustness of the SDM approach (Guisan and Thuiller Reference Guisan and Thuiller2005). Thus, field surveys are crucial for model evaluation, and particularly necessary in those studies of threatened species in which specific conservation practices need to be implemented.

Nonggang Babbler Stachyris nonggangensis; hereafter, NB) is a newly discovered member of the family Timaliidae, found in the limestone karst forest of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (Zhou and Jiang Reference Zhou and Jiang2008). It was classified originally as ‘Near Threatened’ in 2010 and then changed to ‘Vulnerable’ in 2012, due to its small population and narrow geographic distribution (https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22735635/110376677). Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013) found that NB was restricted to three out of 19 nature reserves and forest areas they surveyed in south-west Guangxi and south-east Yunnan Province, China. Eames and Truong (Reference Eames and Truong2016) also recently discovered NB in north-east Vietnam. Even with this foundation of research, the status of the species in the Sino-Vietnamese border area, and between the known sites of distribution in China, is poorly known. Due to the difficult terrain of this karst region and the transboundary nature of the area, the SDM approach to estimating suitable range is particularly appropriate for this species.

In this study, we first compiled and extended the occurrence data of NB field surveys, consulting with researchers or forestry officials who work in this area. We then implemented the SDM for NB, integrating data on climatic, vegetation and topographical variables. Finally, we conducted a field investigation to validate the accuracy of the SDM, and test if the range of the species is greater than previously thought.

Methods

Research area

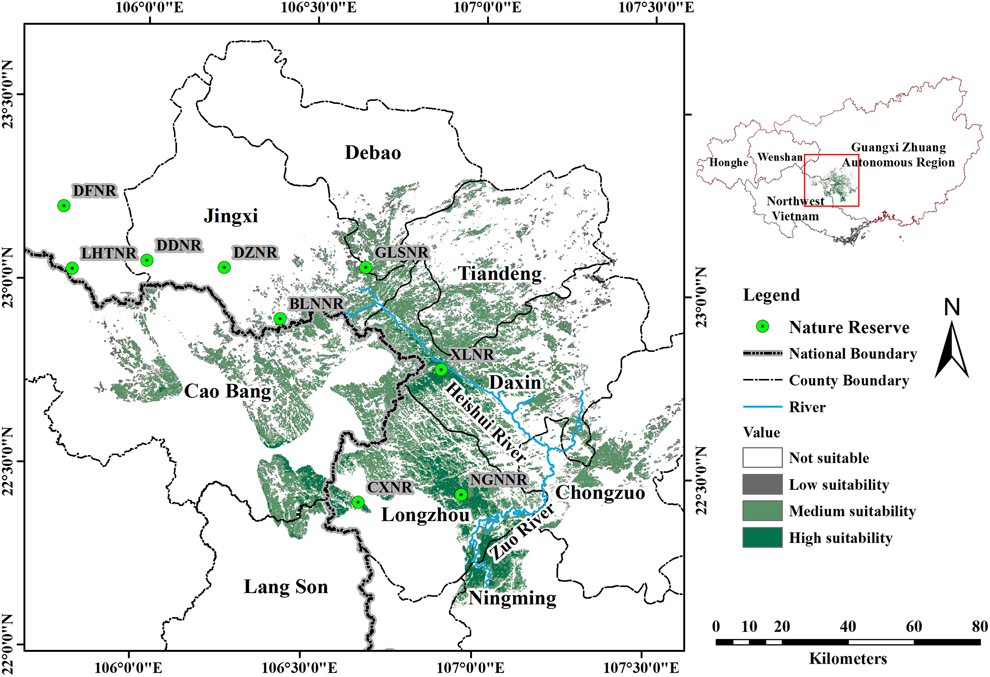

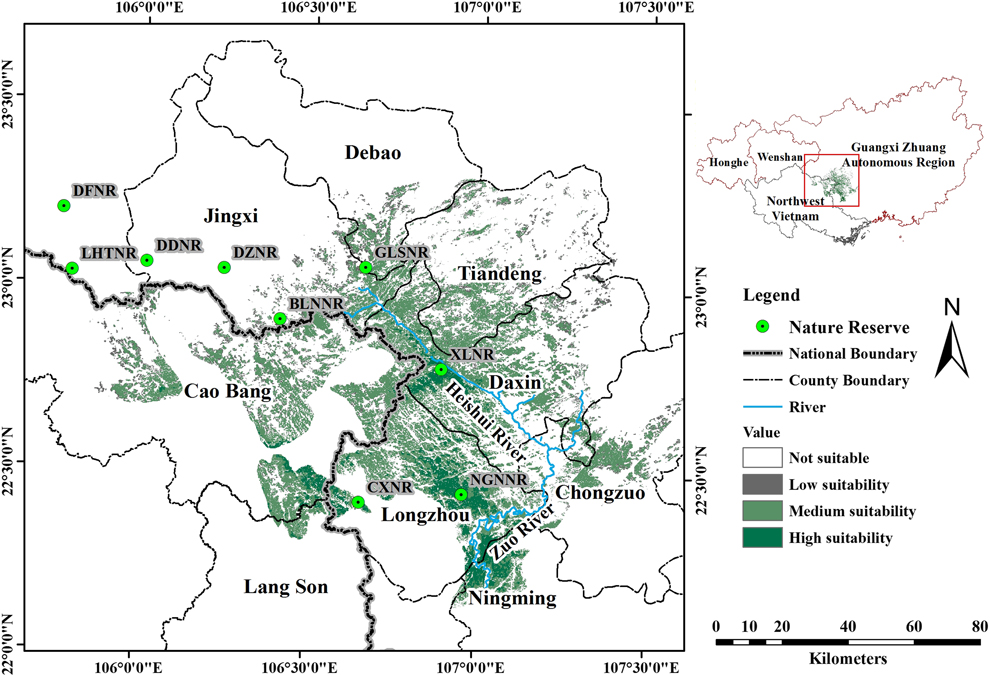

Previous research has described NB as a karst specialist that forages on the ground in relatively undisturbed karst forest along the Sino-Vietnamese border (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013), an ecological profile that has been confirmed by field observations in karst and non-karst habitats over the past few years in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhou and Liu2014). The typical habitat of NB is characterised by steep slopes, low shrub and tree density, and thick litterfall (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Lu, Yu, Jiang, Meng and Zhou2012), and the species only nests in limestone boulders or cliff sides (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhou, Wu and Liu2013). Hence, we restricted our study to a large area in the region that includes karst forest (Figure 1 inset): the whole administration area of Guangxi, Honghe Municipality and Wenshan Municipality in south-eastern Yunnan Province, and the LangSon, CaoBang and BacCan Provinces of north-eastern Vietnam. Even though some karst forest is distributed beyond this area, we do not consider such areas because 1) there are large distances (> 200 km) from existing populations, and geographic barriers that consist of non-karst landscape, or agriculture (e.g. Guizhou Province), or 2) these areas have been explored intensively by enthusiastic birders, but the species has never been recorded there, even though other karst specialist birds, such as Limestone Wren Babbler Napothera crispifrons or Streaked Wren Babbler Napother abrevicaudata, are well-known in the area (e.g. south-western Yunnan Province).

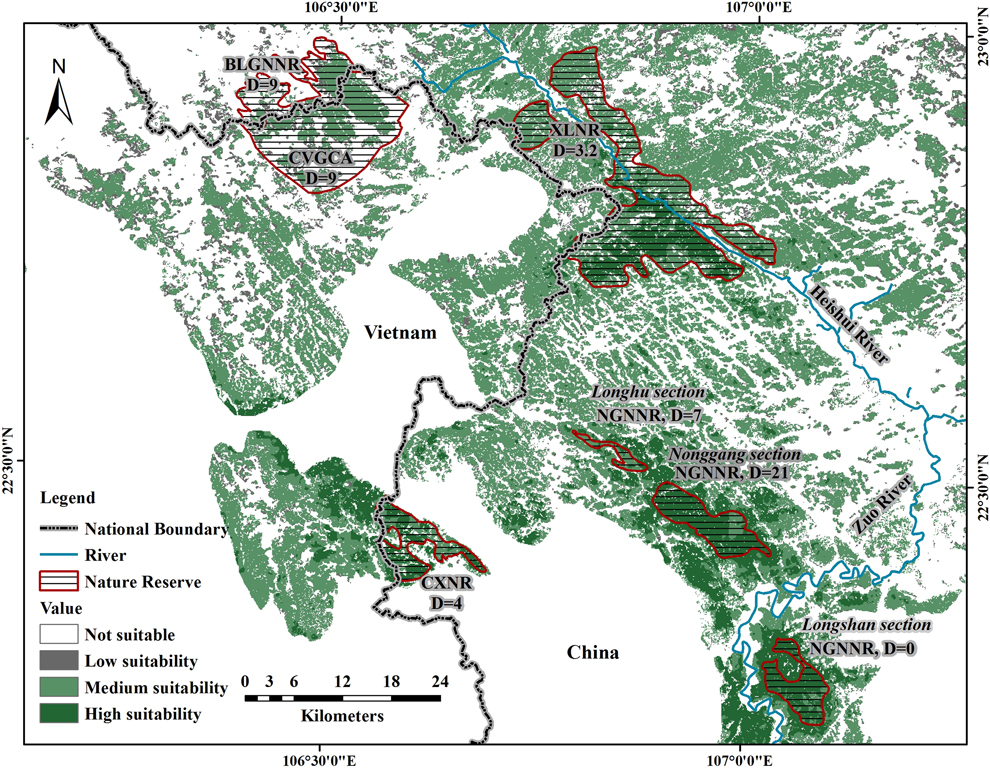

Figure 1. The research area and model outcome. 1) The inset on the top right shows the research area included in the analysis, in China and Vietnam. We included most areas that had karst forest in this region, as the Nonggang Babbler (NB) is clearly a karst specialist, except south-western Yunnan Province, where the bird has never been seen, despite extensive activity by birders. 2) The larger map shows the model outcome: the estimated distribution of the Nonggang Babbler, with habitats of high, medium and low suitability (see text for numerical threshold of these categories). Habitats where non-suitable areas are immediately adjacent to highly suitable habitats, such as south-western Longzhou County, China, represent lands that are not karst. The border between China and Vietnam is shown by the thickest line in the larger map. NB has not been detected to the east of the Heishui River or to the south of the Zuo River. For abbreviations for most of the Nature Reserves, please see Table 1 (additional abbreviations include: NGNNR, Nonggang National Nature Reserve; CXNR, Chunxiu Nature Reserve).

Data collection and modelling

Occurrence data

Occurrence data were collected throughout the entire habitat where NB has been observed in Guangxi, China, using two methods. The first method was to obtain occurrence points of NB by consulting with researchers or forestry officials who have conducted field surveys in Bangliang Gibbon National Nature Reserve (BLGNNR) and Chunxiu Nature Reserve (CXNR). The second method was through our own surveys in the Nonggang sector of Nonggang National Nature Reserve (NGNNR) and the surrounding areas (within 4 km of the reserve boundary). During the breeding seasons of 2012 and 2013, we searched for NB using a line transect method, placing 25 transects each of 1.5 km throughout this area. Transects were 100 m wide and were visited twice each and surveyed at a standard rate of 1.5 km/hr. When NB was detected on a transect, we recorded the exact longitude and latitude, slope and vegetation type. After aggregation of all the presence information, we kept only one point within 1 km square km to avoid spatial autocorrelation and to match the scale of resolution of the climate data. In all, 33 occurrence points were collected.

Predictor variables

We selected and downloaded environmental variables from websites freely accessible to the public, including bioclimatic factors, topographical, and vegetation data. A) We selected the following climate variables, which were likely to shape species distributions by imposing extreme ecological conditions, and not strongly correlated to each other (Global Moran’s I < 0.69): (1) mean diurnal temperature range, (2) mean temperature of driest quarter, (3) precipitation of driest quarter, (4) precipitation of warmest quarter. Climate data were downloaded from the Global Climate Data website (http://www.worldclim.org/), which summarises average monthly conditions from 1970 to 2000. B) Topographical data included (5) digital elevation model (DEM) data, (6) slope, and (7) presence/absence of karst, because NB requires low elevation, steep slopes and the species is exclusively found in karst forest. We downloaded DEM data from Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn/) and then extracted slope derived from it. The distribution of karst forest was extracted manually by drawing a layer that coincides with the edge of karst formations, as judged by their unique visual pattern on satellite imagery. C) Vegetation factors like (8) normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and (9) tree cover were included because NB prefer undisturbed forest. For the NDVI data, we downloaded two MODIS MYD13Q1 V6 images from USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). The images were produced in February 2017 at 250 m resolution and were re-projected and formatted using the HDF-EOS tool of GeoTIFF Conversion Tool 2.14 (https://newsroom.gsfc.nasa.gov/sdptoolkit/HEG/HEGDownload.html), to match with the other factors. For the tree cover data, we first downloaded tree cover in the year 2000, and tree cover loss 2000–2017 (http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com), and then used the raster calculator tool in Arcmap 10.1 to obtain tree cover in 2017. All processing of these variables, such as clipping, format conversion, resampling, and reclassification were conducted in Arcmap 10.1 and resampled to 90 m resolution (a compromise between the 1-km resolution of the climate data, the 250-m resolution of NDVI data, and the 30-m resolution of the other data).

Model building

We followed the instruction of the MaxEnt software tutorial (version 3.4.0; Phillips Reference Phillips2017). In this process, we used 75% of occurrence data for model training and the rest for model testing, set the replication of prediction output at 15 and maximum iterations at 5,000, and selected cross validation as the replicated run type. All the marginal response curves of the variables were smooth, suggesting the models were not overfit.

To increase the usefulness of our resulting maps in conservation planning, we applied the average value of maximum training sensitivity plus specificity (hereafter, “Max SSS”; 0.094 in our study) as the threshold for conversion of output data (colour heat maps) from a continuous variable of suitability prediction into a binary map of suitable and not suitable habitat (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Berry, Dawson and Pearson2005, Reference Liu, White and Newell2013). Additionally, as a threshold between low and intermediate suitability, we used the average values of occurrence in BLGNNR (0.164), which had the lowest values of occurrence of any of the sites of NB, and a considerably lower population density (9 individuals per km2) than the densest populations in the Nonggang sector of NNNR (21 individuals per km2). For the threshold between intermediate and high suitability, we used the average value of all occurrences (0.731).

After the model output, we eliminated areas with a tree cover of < 40%, because 1) there were no occurrences in such areas, and 2) Maxent could not distinguish the extensive but thin protrusions of valleys between limestone karsts, due to the low resolution of the imagery, and this approach allowed the model results to be more exclusive to the karsts themselves (Figure S1 in the online supplementary material). Finally, we deleted isolated patches of less than 4 pixels that were on the edge of potential suitable habitats.

Field validation

To test the accuracy of the models we carried out field validation surveys in seven nature reserves of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, including reserves where NB had never been detected and one with a known low density of NB (BLGNNR; Table 1). All these reserves had the forest type (tropical seasonal monsoon karst forest) required by NB but were predicted to have different levels of habitat suitability by our models. In total 39 transects were surveyed, > 500 m apart from each other, covering 157.2 km, between September 2015 and March 2017. Line transects varied from 0.8 km to 21.5 km in length (4.0 ± 3.4), and were placed in habitats of low, medium and high suitability in proportion to the amount of such habitat estimated by the SDM to be present in these reserves. Twenty-one transects in six nature reserves were in unsuitable habitats for NB, three transects in two reserves were in habitats of low suitability, 10 transects in three reserves were in habitats of medium suitability, and five transects in one reserve were in habitats of high suitability. The survey methods we implemented were similar to those described for NGNNR above (see “occurrence data collection”). After the field validation, to see how stable the model results were, we reran the SDM. This run included 41 occurrence points, including eight new occurrence points found during the field validation (see Results).

Table 1. The validation of the modeling by field surveys. All surveys were in Nature Reserves (NR) or National Nature Reserves (NNR) in Guangxi Province, China.

a NB was only discovered in high suitability transects

b NB was only discovered in medium suitability transects

Results

Species distribution modelling

The area under the curve value (AUC), a parameter often used in evaluation of robustness of MaxEnt models, was 0.994 and the training omission and testing omission of Max SSS were 0 and 0.06 respectively, which indicated our model had good performance. The first five out of nine variables contributed 97.9% of the model fit, including presence of karst (42.7%), mean temperature of driest quarter (23.1%), tree cover (14.3%), precipitation of driest quarter (9.2%), and NDVI (8.6%). The relative importance of the variables was similar when assessed by permutations.

The entire suitable habitat estimated by the model for NB was 4,481 km2 in extent, the majority of which was in the south-west of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (74.2 %), with the rest in north-east Vietnam (Figure 1). This distribution is consistent with the historical reports on this species. The highly suitable habitat for NB (Figure 1) was 541 km2, and mainly located in north Longzhou County and south-west Daxin County. Only a small percentage of the highly suitable habitat (14.4%) was in north-east Vietnam, in forest geographically connected with CXNR. Habitat with an intermediate level of suitability (Figure 1) was mainly distributed north and west of the highly suitable habitat, including the majority of Daxin County, the south of Tiandeng County, the south-east of Jingxi County and the west of Caobang Province, with a total area of 3,218 km2, 27.4% of which was in Vietnam. Habitat with a low level of suitability (Figure 1) was dispersed within or along the edge of the habitat of high or intermediate level suitability, covering 722 km2, with 27.3% of the habitat located in north-east Vietnam. The results remained quite similar when the model was re-run with more presence data found in the field validation (Figure S2).

Field validation

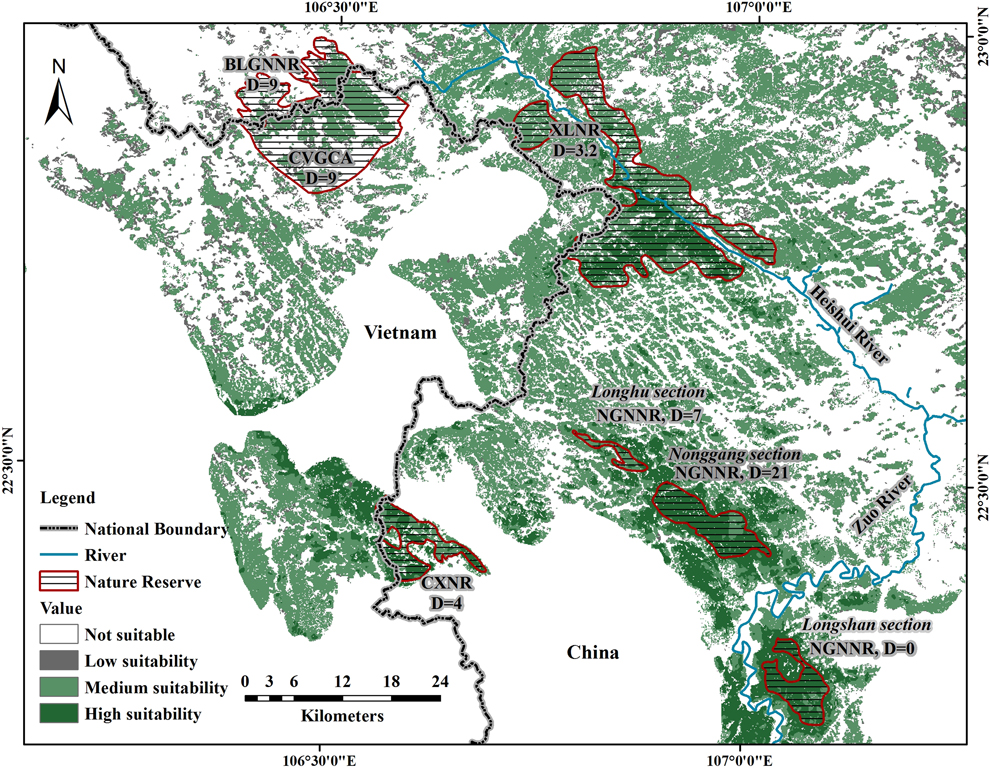

A new distribution site of NB, Xialei Nature Reserve (XLNR), was discovered in our field validation. NB was found in four out of five transects in the highly suitable habitat of this nature reserve and 21 individuals were counted, with a density estimated at 3.2 individuals per km2 (Table 1). NB was also detected in two out of 10 transects in habitat with an intermediate level of suitability, both times in BLGNNR, where a low density of NB has been found in previous work; here only three individuals were detected. NB was not detected in the 24 transects placed in habitat of low suitability or in not suitable habitat.

Updated estimates of the area of realised distribution of NB

In total, including sites discovered by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013) and Eames and Truong (Reference Eames and Truong2016), there are four isolated sites in which NB is known to occur: 1) NGNNR, the reserve where NB was discovered, which is near the center of the species’ distribution and contains well-preserved forest, 2) CXNR, a small reserve protected for water resources (78 km2), which is separated by 25 km from NGNNR by agricultural lowlands surrounding the city of Longzhou, has some parts that are heavily impacted by human disturbance, and is adjacent to some unprotected forest tracts in Vietnam, 3) XLNR, the newly discovered site, with well-protected karst forest, separated by 20 km from NGNNR, and 4) BLGNNR and Cao Vit Gibbon Conservation Area (CVGCA), which are geographically connected, although separated by the border, are 27 km away from XLNR, and have some parts that are highly fragmented. The combined area of these four sites, including the total extent of each reserve, is 555 km2, which comprises 12.4% of the entire suitable habitat for NB (this figure does not include the Longshan sector of NGNNR, where NB has never been recorded; see Discussion). In fact, only 31.2% of the entire suitable habitat is located within any kind of protected area.

Discussion

We estimated the extent of suitable habitat of NB, and hence its potential distribution, by applying MaxEnt SDM models, incorporating many environmental variables that may restrict the distribution of NB, including data on climate, topography and vegetation. Our model suggested that the entire area of suitable habitat of NB is 4,481 km2. In a strong field validation of the modelling, we found NB in four of five transects placed in highly suitable habitat in XLNR, a reserve where NB had previously not been detected, and in two out of 10 transects in habitat of intermediate suitability. Meanwhile, we found that the species is absent from large portions of habitats with low and intermediate level suitability. Below, we first discuss how factors not included in the SDM models, including the species’ life history and behavioural traits, may underlie why the realised distribution is so much smaller than the extent of suitable habitat. Second, we discuss how our measurement of factors in the model might have led to some exaggeration in the estimate of the range of suitable habitat. Finally, we consider the implications of our work for the conservation of NB.

Factors not included in the modeling that may restrict the realised distribution of NB

The realised distribution of species is shaped by many factors including biotic, abiotic, anthropogenic, and historical processes. Very few species fully colonise all the habitat suitable for them (i.e. their fundamental niche) and for this reason the ranges predicted by SDMs are usually larger than the realised distribution (Pulliam Reference Pulliam2000, Vetaas Reference Vetaas2002, Guisan and Thuiller Reference Guisan and Thuiller2005). In our case, geographic barriers may be the main factor that prevents NB from colonising suitable habitat. For example, all records of NB from this and previous studies are to the south and west of the Heishui River, which has a width of 20–140 m (see Figure 2). Further, no records of the species have been reported to the south of the Zuo River, which has a width of 100–200 m. This is despite there being suitable forests on the other sides of this river, with the Longshan sector of NNNR being one example. Other small rivers crisscross the range of NB, potentially influencing its movement.

Figure 2. Realised distribution and density of NB. Reserves in which NB has been found are indicated by shading. Associated with each reserve, or each part of NGNNR (divided into three sections), is an estimate of NB density (D = individuals per km2) from Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013). For XLNR that estimate was made from the data we gathered in the field validation phase of this study. CVGCA: Cao Vit Gibbon Conservation Area, the density of NB in this area was proposed by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013). The boundaries of reserves and governmental jurisdictions are approximate.

Beyond natural features such as rivers, human-induced change is also certain to restrict dispersal. Except for the forest inside nature reserves, all the karst forest has been disturbed to a varying degree. Areas that are relatively flat and lie between karst peaks have been transformed into intense cultivation of economically productive crops, such as sugarcane. It is probable that NB may avoid moving through such agricultural lands, as NB has never been observed in such land types outside forest (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhou, Wu and Liu2013, Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013).

The behavioural and ecological characteristics of NB may also limit it colonising suitable habitat. NB is a ground foraging species that very rarely flies for a long distance, even after approach by humans (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Lu, Yu, Jiang, Meng and Zhou2012), and this could contribute to its inability to cross natural or human-made barriers. Other terrestrial forest specialists have been shown to have trouble flying across bodies of water even 100 m across (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Robinson, Lovette and Robinson2008). Further, NB has apparently low breeding success, with a rate of nest predation of approximately 75% (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhou, Wu and Liu2013). Such a low level of breeding success, if characteristic throughout the species’ range, would result in low demographic pressure, rare emigration, and incomplete colonisation of the full suitable range. In conclusion then, low breeding success and catastrophic events might lead to extirpation of NB in small patches, while poor dispersal through disturbed habitats and geographic barriers would limit the establishment of new patches. Altogether, these factors suggest the existence of source-sink dynamics unfavorable to the continued existence of the species (Pulliam Reference Pulliam1988).

Issues of the accuracy and sample size of the data included in the modelling

The low resolution of the data used in the modelling may also have led to some exaggeration in the model’s estimates of the potential suitable habitat. First, several important environmental variables, such as climate data (1-km resolution), and NDVI (250 m) had low spatial resolution, and the outline of the limestone karst area was drawn manually, approximately along the edge of the mountains. The limestone karst landscape is very fine-scaled, with narrow, ribbon-like protuberances of valleys running through it (Figure S1). Even though we used the < 40% forest cover rule to improve the exclusivity to karst, some areas were probably misclassified. Second, the low resolution of vegetation data may have failed to identify degraded forest or timber plantation as distinct from natural forest in some areas. Third, in order to better match the climate and NDVI data, we had to resample tree cover, slope, and DEM datasets from 30 m to 90 m. This process may result in a small proportion of pixels being incorrectly classified. Overall then, the species may have stricter habitat requirements than we were able to model. We know that NB prefers well-developed karst forest, requiring high canopy cover and thin understorey (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Lu, Yu, Jiang, Meng and Zhou2012). Our vegetation data may have been too coarse to fully restrict the suitable habitat to areas with these precise requirements.

Small sample sizes of presence data can affect the performance of any SDM. Unfortunately, with such a rare, range-restricted species, there are not many solutions for this problem. Nevertheless, MaxEnt has been shown to be robust to small samples sizes within the neighbourhood of 10 locations with presence data (Hernandez et al. Reference Hernandez, Graham, Master and Albert2006, Wisz et al. Reference Wisz, Hijmans, Li, Peterson, Graham and Guisan2008). Furthermore, results of the modelling remained quite similar when we added the new presence data found from the field validation (Figure S2).

Threat level of NB

The threat classification of NB has changed as more information has come in, currently being listed as ‘Vulnerable’ (http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22735635/0). When first discovered, it was known only to be present at NGNNR (Zhou and Jiang Reference Zhou and Jiang2008), but then Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Lu, Jiang, Yang and Yu2013) documented its presence in two additional forest reserves and updated its estimated distribution to 208 km2. Our work establishes that NB is now known to exist in four isolated sites, and we can revise the area of realised distribution to 555 km2 (Figure 2; this estimate should be thought of as generous, because it includes the total extent of the reserves in which the species has been found, even though some reserves have areas of considerable human disturbance). However, this current estimate for the range of realised distribution of NB is far less than the IUCN Red List criterion for ‘Endangered’ which stipulates that a species is ‘Endangered’ if it inhabits five or fewer sites of occurrence within an occupied habitat less than 5,000 km2 (http://www.iucnredlist.org/ technical-documents/categories-and-criteria).

Indeed, our models suggest that the entire extent of suitable habitat for NB is only 4,480 km2. The overall picture of NB’s population is concerning. Only 12.4% of this habitat is colonised by NB to our knowledge. Some populations have very low densities (< 10 individuals per km2), including all sites except the Nonggang section of NGNNR. Only 32.1% of the suitable habitat is located within protected areas. The species apparently has difficulties crossing geographic/human barriers, as described above, and low reproductive success. Given these concerns and that NB is well within the criteria of an ‘Endangered’ species, we suggest that the species be upgraded to this status, from ‘Vulnerable’. We also hope that the species be added to the national threatened species list for both China (http://www.cites.org.cn/database/) and Vietnam.

To conserve this threatened species, we suggest that further field surveys be (a) undertaken in Vietnam, which includes 25.8% of the suitable habitat, but where there is just one sighting to date (Eames and Truong Reference Eames and Truong2016), and (b) focus on areas outside reserves in China that are of high or intermediate levels of habitat suitability in these models, to determine the degree of disturbance that NB can tolerate, and the minimum size of forest patch that can retain the species. Yet we have enough information for managers and policy makers to act now. They can a) explore the possibility of corridors being restored between areas with a high density of birds and those with similar forest but with low densities or absence of NB, and/or b) plan to translocate birds into areas where they are absent, like the Longshan section of NGNNR.

Conclusions

We estimate for the first time the potential suitable habitat extent of this newly discovered species by using SDM. We found that the suitable habitat for NB is restricted to an area of 4,481 km2. Further, the area of its realised distribution is only 555 km2. Most of the habitat of high or intermediate suitability and most the known distribution are in China. Our field surveys strongly supported the model results, with populations only found in habitats classified by the model as suitable at a high or intermediate level, including one new distribution site for the species. Given the species’ range-restriction, poor dispersal abilities, low reproductive success, and the fragmentation of its habitat, we argue that the species should be upgraded from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Endangered’.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270919000236

Acknowledgements

We thank Weihu Duan, Chunrong Mi, Christos Mammides, for their help in the modelling process and Kathryn Sieving for improving an earlier draft. We also thank the National Geomatic Center of China for provided land cover data, as well as WorldClim for the climate dataset, and the Guangxi Forest Department for permission to do the fieldwork. The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31460567 to AJ) and the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCBZ2018011 to DJ).