Introduction

Genetic information and tools have been applied across taxonomic groups to assist management where resistance to a control method has been found, including: antimicrobial resistance (Bengtsson-Palme et al. Reference Bengtsson-Palme, Abramova, Berendonk, Coelho, Forslund, Gschwind, Heikinheimo, Jarquin-Diaz, Khan, Klumper, Lober, Nekoro, Osinska and Ugarcina Perovic2023; Hadfield et al. Reference Hadfield, Megill, Bell, Huddleston, Potter, Callender, Sagulenko, Bedford, Neher and Kelso2018), insecticide resistance (Faria et al. Reference Faria, Quick, Claro, Thézé, de Jesus, Giovanetti, Kraemer, Hill, Black, da Costa, Franco, Silva, Wu, Raghwani and Cauchemez2017; Knox et al. Reference Knox, Juma, Ochomo, Pates Jamet, Ndungo, Chege, Bayoh, N’Guessan, Christian, Hunt and Coetzee2014; Rodbell et al. Reference Rodbell, Hendrick, Grettenberger, Wanner and Anderson2022), herbicide resistance (Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Comont and Neve Reference Comont and Neve2020; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons and Jiang2010; Heap Reference Heap2024), and fungicide resistance (Fontaine et al. Reference Fontaine, Remuson, Caddoux and Barrès2019; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Hawkins, Fraaije, Sariaslani and Gadd2015; Massi et al. Reference Massi, Torriani, Borghi and Toffolatti2021). Pretreatment identification of resistant populations using genetic markers can inform management and control.

Recent studies demonstrate that genetic variation can be relevant to aquatic weed management as well. For example, herbicide resistance has been documented in hydrilla [Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle] (Michel et al. Reference Michel, Arias, Scheffler and Duke2004), landoltia [Landoltia punctata (G. Mey.) D.H. Les & D.J. Crawford] (Koschnick et al. Reference Koschnick, Haller and Glasgow2017), and Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum L. sensu lato) (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2012, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015a, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015b; Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Heilman, Hausler, Huberty, Tyning, Wcisel, Zuellig, Berger, Glomski and Netherland2012). However, genetic studies of resistance are relatively rare for aquatic weeds compared with agricultural weeds, and thus molecular assays for resistance are relatively rare (but see Benoit and Les Reference Benoit and Les2013; Michel et al. Reference Michel, Arias, Scheffler and Duke2004). Therefore, the development of molecular tools to predict herbicide response could improve aquatic plant management outcomes.

For clonal organisms, such as many aquatic plants, characterizing herbicide response of clones (i.e., genets) can inform management decisions in the short term, while longer-term studies to identify herbicide response genes are being conducted. For example, clones that are widespread, rapidly increasing, and/or have been noted by managers to exhibit lower than desired management response could be prioritized for herbicide response characterization, which could inform management efforts in all locations where they are found. Therefore, DNA fingerprinting approaches (e.g., microsatellites and single-nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] assays) that can identify ramets of the same genet and distinguish unique genets can be a valuable, short-term management tool for the management of clonal aquatic plants (e.g., Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022; Hoff and Thum Reference Hoff and Thum2022; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020).

Myriophyllum spicatum and its hybrids with native northern watermilfoil (Myriophyllum sibiricum Kom.) are among the most widespread and heavily managed aquatic weeds in the United States (Bartodziej and Ludlow Reference Bartodziej and Ludlow1997; Confrancesco Reference Confrancesco1993). Within M. spicatum, its native sister species, M. sibiricum, and their hybrid M. spicatum × M. sibiricum, there are distinct genotypes, or strains, that are produced through sexual reproduction (Hartleb et al. Reference Hartleb, Madsen and Boylen1993; LaRue et al. Reference LaRue, Zuellig, Netherland, Heilman and Thum2013; Thum and McNair Reference Thum and McNair2018; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020). Therefore, unique M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum clonal lineages (hereafter “strains”) can spread indefinitely through clonal propagation both within and between lakes (Smith and Barko Reference Smith and Barko1990).

Strains of invasive Myriophyllum differ in their response to herbicide treatment (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2012, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015a, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015b; Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Hoff and Thum Reference Hoff and Thum2022; Netherland and Willey Reference Netherland and Willey2017). As such, strain-level information about invasive Myriophyllum populations is relevant to management. Because some strains are found in multiple lakes (Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020), herbicide treatment options can be better evaluated when the particular strain(s) in a lake are characterized for their herbicide response. For example, a fluridone-resistant strain of M. spicatum × M. sibiricum is commonly found in Michigan lakes, whereas fluridone-susceptible strains are also commonly found in Michigan lakes (Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020). Therefore, genetic screening for these strains can help determine whether fluridone is an appropriate herbicide to use in a given Michigan lake.

Even in the absence of herbicide response data, strain composition information can help inform management (Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022). For example, utilizing pre- and posttreatment strain surveys on a lake can help identify whether the relative frequencies of different M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains change after a herbicide treatment. If so, this observation could help to identify strains for further study in laboratory herbicide response assays. Additionally, aquatic plant managers and stakeholders whose lakes share strains could share their management experiences, or even judiciously design field studies to assess management alternatives.

Although genetic variation is clearly important for M. spicatum management outcomes, a centralized location that provides access to M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain information is currently lacking. Here, we present an R Shiny application designed to address this need—MilfoilMapper.

Materials and Methods

Strain Identification and Distribution

To date, 4,911 Myriophyllum tissue samples have been collected and identified to the strain level from across 15 different U.S. states through the participation of state agencies, aquatic plant management consultants, and citizen scientists. Additionally, some data contained in the MilfoilMapper database have been previously published (Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Eltawely et al. Reference Eltawely, Newman and Thum2020; Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022; Hoff and Thum Reference Hoff and Thum2022; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020). New strain data are added to MilfoilMapper every season, and more than 200 strains have been added to the database since the most recent publications cited above.

To characterize strain composition for a lake, we recommend contributors target a representative sample of 20 to 50 plants from around the lake. However, there was no standardized sampling protocol used for the samples included in MilfoilMapper due to the differing sampling methods, objectives, and constraints among collectors. For example, some samples were collected as a part of quantitative vegetative mapping (e.g., point-intercept surveys), whereas others were collected in a stratified way across locations where Myriophyllum was present in the water body (e.g., meandering shoreline surveys). In some cases, plant samples were submitted with little to no information on the sampling protocol used. When more than 20 plants were sampled, we typically processed a subsample of 20 plants. If fewer than 20 plants were provided for a water body, all plants were processed.

In some cases, the exact latitude and longitude values were provided for each individual sample for a given water body. However, in most cases, we do not have those data. Therefore, we decided to standardize all strain occurrences to a centroid latitude–longitude point within a water body. These values were taken from state Department of Natrual Resources (DNR) websites when available. If these data were unavailable, a centroid latitude–longitude was selected using Google Maps.

Plant samples were generally dried with silica gel before being shipped to the laboratory for processing. In some cases, plant samples were shipped live, and fresh material was either immediately dried with silica gel or flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored in a −80 C freezer until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from all samples using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA extractions were duplicated for ∼10% of all samples to assist with scoring of microsatellites.

Plants were genotyped using the same methods described in Thum et al. (Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020). Briefly, we genotyped plants using eight microsatellite loci developed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Yu and Xu2013; Myrsp 1, Myrsp 5, Myrsp 9, Myrsp 12, Myrsp 13, Myrsp 14, Myrsp 15, and Myrsp 16) under the PCR conditions described therein. Fluorescently labeled microsatellite PCR products were sent to the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign’s Core Sequencing Facility for fragment analysis on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Microsatellites were scored using GeneMapper v. 5.0 (Applied Biosystems). Because M. spicatum, M. sibiricum, and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum are hexaploid, exact strain identifications cannot be determined, as the numbers of allele copies are ambiguous. Therefore, we treated microsatellites as dominant, binary data (i.e., presence or absence of each possible allele at each locus) using R (R Core Team 2022) and the R package polysat (Clark and Jasieniuk Reference Clark and Jasieniuk2011). We delineated distinct multi-locus strains (hereafter, simply “strains”) using Lynch distances and a threshold of 0 in polysat (Clark and Jasieniuk Reference Clark and Jasieniuk2011). Each unique microsatellite strain identification was given a unique identification code. Individuals with the same microsatellite strain identification were assumed to be ramets of the same genetic clone and were therefore given the same identification code in MilfoilMapper.

Each strain present in MilfoilMapper is assigned one of four different herbicide response labels (Susceptible, Resistant, Of Concern, or Unknown) based on herbicide characterization data (Supplementary Table 1). “Susceptible” and “Resistant” labels are given to strains that have both field and laboratory observations of herbicide efficacy that comport with one another. Strains labeled as “Of Concern” have been brought to our attention by lake managers as possibly resistant based on qualitative observations but have not yet been included in a quantitative and controlled laboratory study of herbicide response. Finally, strains without any herbicide response observations are labeled as “Unknown.”

MilfoilMapper Creation

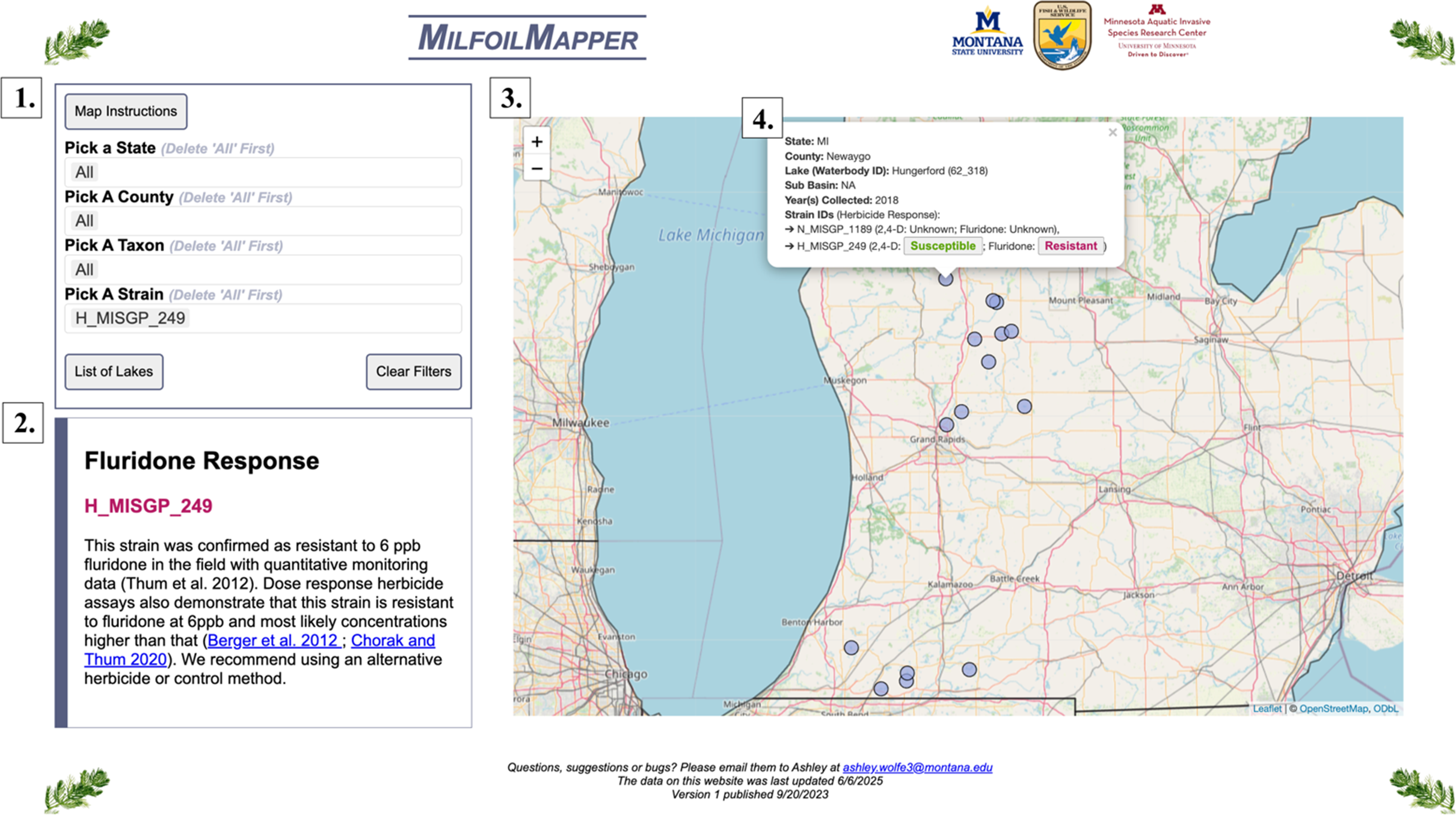

We created an R Shiny application—MilfoilMapper—to house and share compiled M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain information (Figure 1). We chose to create our website using the R package shiny (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Cheng, Allaire, Sievert, Schloerke, Xie, Allen, McPherson, Dipert, Borges, Foundation, Otto, Thornton, Nawaz Khan, Tsaran and Lembree2024) because it is a user-friendly way (creators are not required to be familiar with HTML, CSS, or JavaScript) to build web applications that can house and visualize voluminous data for free for both users and developers. MilfoilMapper can provide two pieces of information for identified strains to guide management decisions: (1) herbicide response for one or more herbicides commonly used for control and (2) occurrence and geographic distribution information. The application is available at: https://thumlab-msu-watermilfoilapp.shinyapps.io/milfoil_app/. A copy of all source code is contained in a GitHub repository: https://github.com/AshleyW406/MilfoilMapper.git.

Figure 1. Illustration of MilfoilMapper components. (1) The database can be queried by geography (state, county, lake) or genetic factors (taxon or strain). This example filters data for the strain H_MISGP_294. The “List of Lakes” button will return a list based on the query (not shown). (2) An information box, where additional details about herbicide response information and strain nomenclature are displayed. (3) Interactive map showing the distribution of strains based on the results of a given query. In this example, H_MISGP_249 occurs in two discrete clusters in the central and southwestern part of Michigan. (4) Selecting an individual water body produces a list of all strains that have been identified there, including buttons displaying herbicide response information. At present, herbicide response information is limited to two common herbicides for Myriophyllum spicatum sensu lato control: 2,4-D and fluridone. If a herbicide response button is selected, additional information populates box 2. In this example, the selected lake, Hungerford Lake, MI, displays the two strains identified in this lake: H_MISGP_249 is indicated as Susceptible to 2,4-D and Resistant to fluridone, whereas H_MISGP_1189 is indicated as having unknown herbicide responses.

Use of a Large-Language Model

Authors acknowledge the limited use of a large-language model (LLM), ChatGPT 4.0, in the preparation of this article. Specifically, it was used for troubleshooting RStudio code for figure creation and for rewording select sentences to improve clarity in the original drafts of the manuscript. The tool was not used to generate scientific content, develop ideas, analyze data, or interpret results. All scientific work and manuscript writing are entirely the original work of the authors.

Results and Discussion

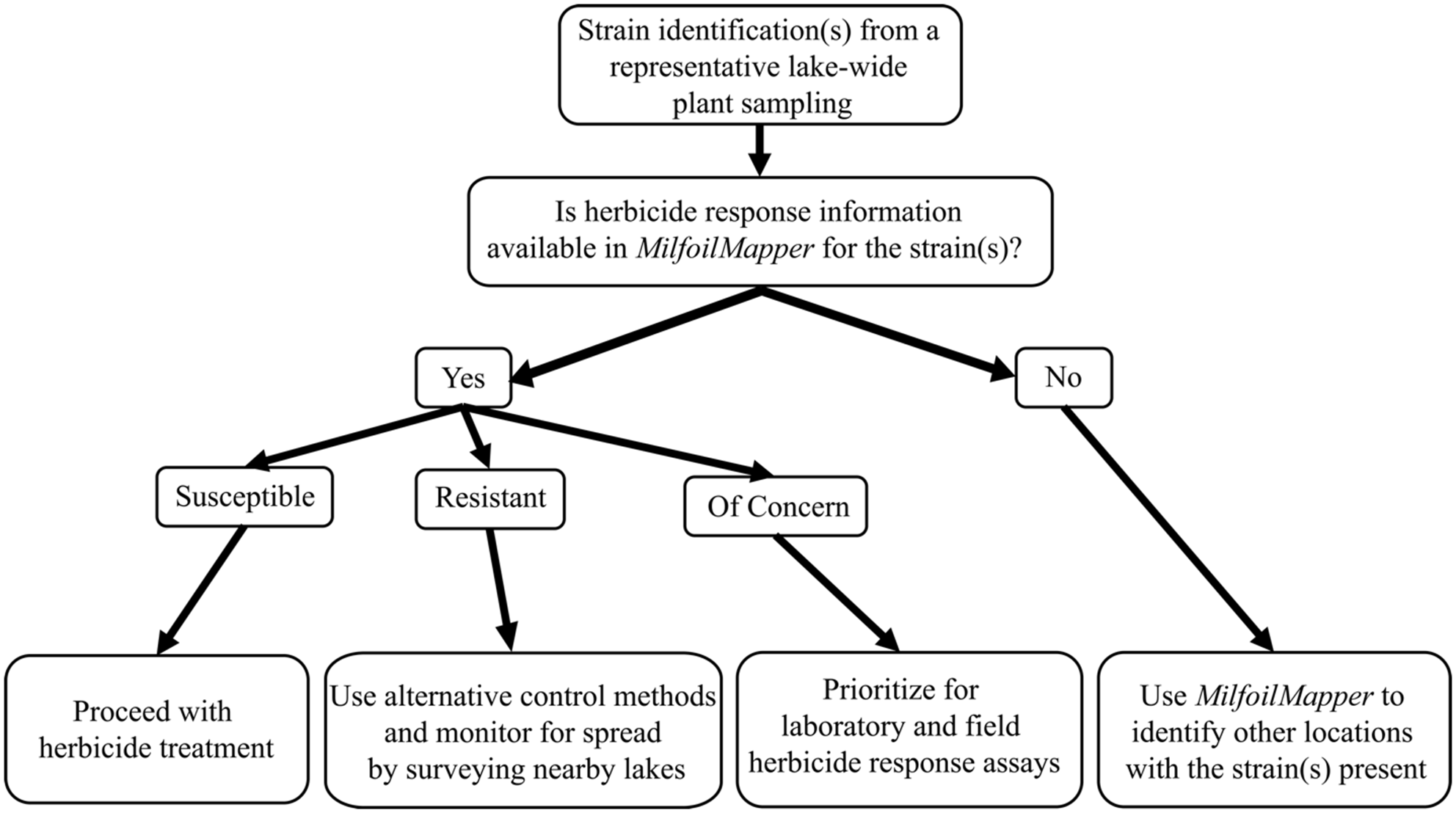

MilfoilMapper serves as a centralized, living repository that integrates strain and herbicide response data to help inform management strategies based on the strains present in a lake and whether those strains are common or regionally unique (Figure 2). When available, herbicide response data can be used to directly inform herbicide prescriptions. When herbicide response data are not available for a given strain, MilfoilMapper allows users to identify other lakes where the strain occurs, facilitating communication among managers and potentially pooling resources needed to conduct field or laboratory studies. Collectively, these components of MilfoilMapper provide valuable guidance for developing and modifying comprehensive management plans for M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum.

Figure 2. Workflow for Myriophyllum spicatum sensu lato strain identification(s) to help inform management decisions. The most direct impact on decision making will occur when herbicide response data are available. However, in the absence of herbicide response data, information on strain distribution and occurrence can still inform management decisions. We always recommend quantitative monitoring of a strain’s herbicide response in the field.

In the following sections, we discuss the current status and future prospects of the major components of MilfoilMapper: (1) strain identification; (2) diversity, occurrence, and distribution of strains; and (3) herbicide response.

Strain Identification

The strains currently in MilfoilMapper are distinguished with eight multi-locus microsatellite genotypes. We recognize the small number of microsatellite markers can potentially result in erroneous strain identifications. For example, two individuals may share the same multi-locus genotype by chance instead of through shared ancestry by clonal reproduction. The hexaploid nature of our microsatellite markers requires that we score microsatellite data as dominant and precludes us from calculating probabilities of identity for individuals with the same genotype. However, given the extensive clonal propagation of M. spicatum sensu lato, we believe assigning the same strain identification to individuals with the same multi-locus genotype is reasonable. In addition, somatic mutations can accumulate during clonal propagation, and individuals that share ancestry through clonal reproduction could exhibit different herbicide responses. For example, invasive H. verticillata in the United States has evolved fluridone resistance through somatic mutations (Michel et al. Reference Michel, Arias, Scheffler and Duke2004). Finally, scoring errors could potentially identify two individuals of the same clone as different strains. However, we have used extensive duplicate samples to identify microsatellite loci and alleles that are robust, and we manually inspect every microsatellite chromatogram for accurate scoring.

Given the limitations of microsatellite markers, M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain identification could potentially be improved with a modernized approach based on SNP markers. JJ Pashnick and RA Thum (unpublished) piloted a panel of targeted SNPs for genotyping-by-sequencing in M. spicatum sensu lato (see Baetscher et al. [Reference Baetscher, Clemento, Ng, Anderson and Garza2018] and Campbell et al. [Reference Campbell, Harmon and Narum2015] for similar methodologies). Implementation of this approach was initially hampered by difficulty in assigning reads to homeologous subgenomes, as well as unequal amplification of target SNPs and inconsistent amplification among individuals. The recent completion of a high-quality genome (Hannay et al., unpublished data) and further refinement of the original SNPs identified for genotyping-by-sequencing could facilitate the development and implementation of an SNP-based assay to replace the microsatellite approach currently used in MilfoilMapper.

Although it is possible for independent laboratories to collect the same genetic data to identify and distinguish M. spicatum sensu lato strains, combining data from different labs should be done with careful curation. Microsatellite allele sizes will differ depending on whether the primers are labeled with fluorescent tags directly versus using a universal fluorescent labeling system (e.g., Shimizu et al. Reference Shimizu, Kosaka, Shimada, Nagahata, Iwasaki, Nagai, Shiba and Emi2002), where the former will yield smaller PCR products than the latter for the same alleles. Similarly, scoring decisions can differ from person to person. We have carefully chosen allele bins based on a large number of duplicate samples, and therefore standardization of the methods used to identify and distinguish M. spicatum sensu lato strains is possible. Similarly, even though the development of an SNP-based identification method may facilitate automated scoring of genotyping-by-sequencing data, collated data from different laboratories would require careful curation to account for sequencing errors and genotype likelihoods. Therefore, we recommend a central curator be identified if multiple laboratories collaborate to collate microsatellite or SNP data on strain identification and occurrence.

Diversity, Occurrence, and Distribution of Strains

The current data contained in MilfoilMapper are a much-expanded version of the dataset presented in Thum et al. (Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020), who reported on 103 water bodies in Minnesota and Michigan. We have now identified strains from an additional 220 water bodies in 15 states. Diversity, occurrence, and distribution patterns in this expanded dataset are similar to those identified in Thum et al. (Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020).

Although we recommend sampling approximately 20 to 50 plants from across a lake to characterize strain composition, not all of the lakes in MilfoilMapper were sampled that way (see “Materials and Methods”). Currently, the strain data in MilfoilMapper are presence–absence. Therefore, any given lake may contain more strains than are reported, and this is obviously more likely in lakes with small sample sizes compared with lakes with large sample sizes. Furthermore, strain composition can vary over time (see Gannon et al. Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022) and thus strains present at a previous time may no longer be present, and vice versa. Future versions of MilfoilMapper may be improved by allowing users to see data for individual sampling events (e.g., sample sizes and dates).

Even though most lakes are dominated by a single M. spicatum sensu lato strain (n = 180), some lakes are more diverse and contain multiple strains (n = 143). Because different strains can respond to herbicides differently, it is important to consider strain composition when planning and assessing herbicide treatments. If multiple strains are present, managers should consider tracking relative strain frequencies over time to detect any shifts in strain frequency (see Gannon et al. Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022; Parks et al. Reference Parks, McNair, Hausler, Tyning and Thum2016). Strains that increased in their relative frequency could then be prioritized for laboratory herbicide assays. However, MilfoilMapper does not currently break down sampling events and is therefore not recommended as a data analysis tool for strain monitoring, per se.

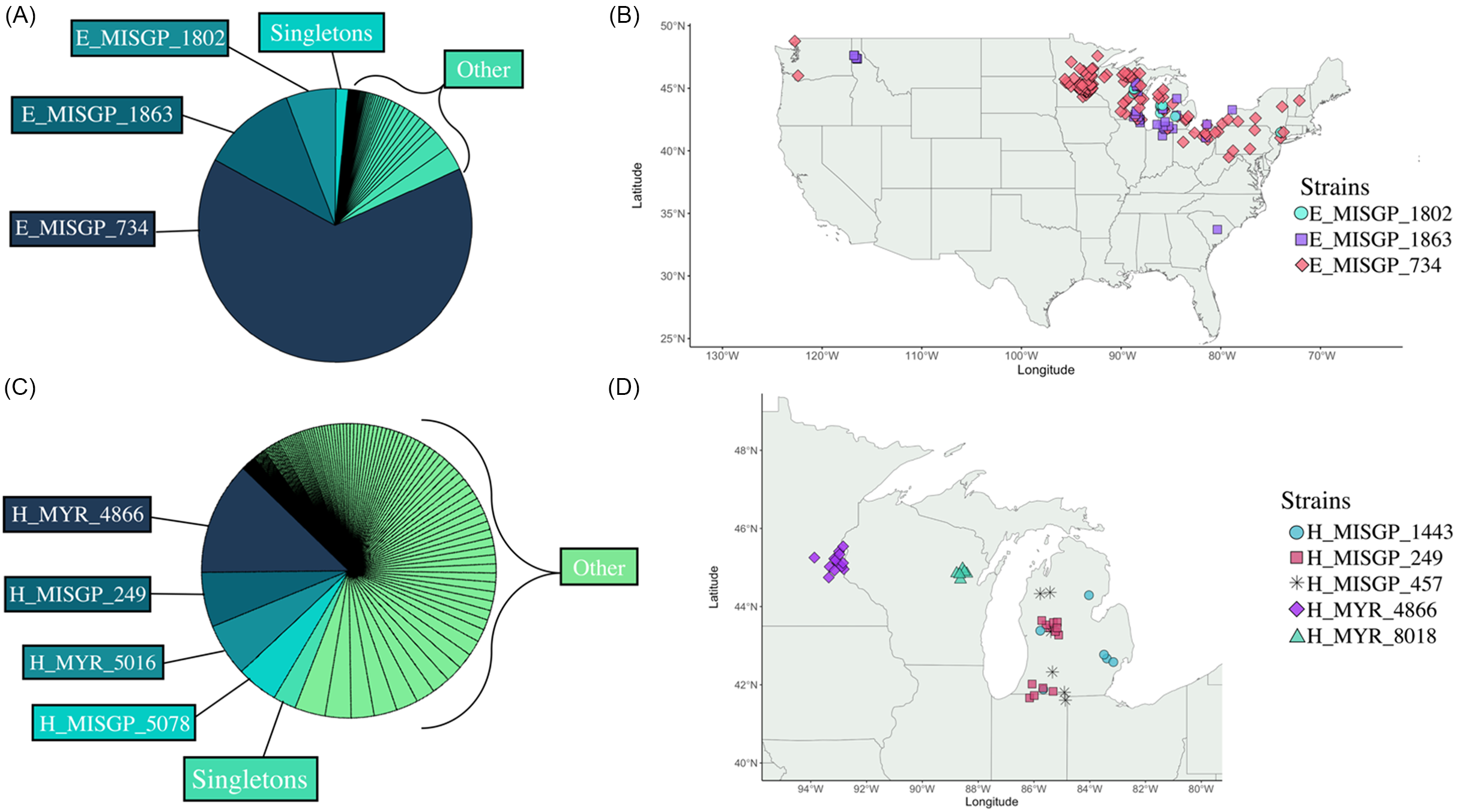

The proportion of strains that have been found in multiple locations, and the geographic breadth of their distributions, differ between M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains (Figure 3). Out of 85 total M. spicatum strains identified, 35 were singletons found only one time in a single lake, making up 1.4% of all M. spicatum strain occurrences. Out of the remaining 50 strains, 7 M. spicatum strains have been identified in multiple water bodies. Of these, three strains were particularly common and geographically widespread (E_MISGP_734, E_MISGP_1863, E_MISGP_1802; see also Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020). Furthermore, these three strains make up 82% of all M. spicatum water body occurrences in MilfoilMapper.

Figure 3. The geographic distribution and occurrence of Myriophyllum spicatum (A and B) and Myriophyllum spicatum × Myriophyllum sibiricum strains (C and D). (A) Relative frequencies of M. spicatum strain occurrences (n = 2,420). (B) Geographic distribution of the three most common M. spicatum strains. (C) Relative frequencies of M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain occurrences (n = 2,490). (D) Geographic distribution of widespread M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains. Strains on this map are considered widespread because they were found in five or more lakes. “Singletons” are strains that have been found once in a single lake. “Other” includes all other strain occurrences.

In contrast, out of the 204 M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains identified to date, 56 are singletons, making up 2% of all M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain occurrences (Figure 3). Of the remaining 148 strains, 29 have been found in multiple waterbodies, making up only 48% of all M. spicatum × M. sibiricum occurrences in MilfoilMapper. However, unlike the three M. spicatum strains discussed earlier, none of the M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains found in multiple locations have a broad geographic range. Instead, M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains found in multiple locations tend to be geographically restricted. Some of these widespread M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains have a more clumped distribution (H_MISGP_249, H_MYR_4866, H_MYR_8018) and others are more dispersed across a state (H_MISGP_1443, H_MISGP_457) (see Figure 3D). These patterns may be due to strains spreading from lake to lake via dispersal vectors (e.g., boats and birds) with specific movement patterns. Alternatively, some strains may be more likely to spread and establish due to their growth or management response. For example, invasive Myriophyllum populations in Michigan are commonly managed with fluridone, and the fluridone-resistant hybrid strain H_MISGP_249 is relatively common in the state, potentially because it can outcompete other strains in lakes managed with fluridone.

The occurrence and geographic distribution patterns described have important management implications. Lakes containing M. spicatum are most likely to have one of a small number of common and widespread lineages, especially E_MISGP_734 (Figure 3). Therefore, herbicide response characterization of these common M. spicatum strains would have a relatively large impact on informing herbicide decisions for a large number of lakes across the United States. In fact, these three widespread M. spicatum strains have all been prioritized for fluridone and 2,4-D characterizations and are listed as “Susceptible” to both herbicides in MilfoilMapper. These M. spicatum strains should be prioritized for studies to characterize their response to other commonly used and newly developed herbicides.

In contrast to M. spicatum, we do not see any M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains that are as common or geographically widespread as the three M. spicatum strains discussed earlier (Figure 3). Instead, M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains are genetically more diverse, and comparatively more geographically restricted than pure M. spicatum strains. This pattern suggests that M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains have arisen many times independently from different M. spicatum and M. sibiricum parents in different locations (Thum et al. Reference Thum, Chorak, Newman, Eltawely, Latimore, Elgin and Parks2020; Zuellig and Thum Reference Zuellig and Thum2012). Further, the greater genetic diversity of M. spicatum × M. sibiricum suggests that we can expect to observe more variation in herbicide response among populations of M. spicatum × M. sibiricum compared with pure M. spicatum.

Admittedly, the more restricted distribution of M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains limits the ability to apply M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain–specific information across multiple locations. It is therefore especially important to carefully observe M. spicatum × M. sibiricum response to herbicide treatments and to prioritize those strains for laboratory herbicide response characterization based on field and observations of control efficacy and how common and geographically widespread they are. Because of their generally restricted distribution patterns, once M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains have been characterized for herbicide response, we recommend that nearby lakes be surveyed for the presence of the same strains. For example, the M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strain H_MISGP_249 is resistant to operational fluridone treatment levels in Michigan (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2012, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015a, Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2015b; Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Heilman, Hausler, Huberty, Tyning, Wcisel, Zuellig, Berger, Glomski and Netherland2012), Since its original discovery and characterization, it has been identified in 12 additional lakes. Further, these lakes occur in two discrete clusters located in central and southwestern Michigan (see Figures 1 and 3). Surveys of nearby lakes where this hybrid strain is identified can thus preclude costly fluridone treatment failures. Similarly, lakes containing hybrid strains that are known to be susceptible to a particular herbicide can reasonably predict similar responses to control methods used in nearby lakes with the same strains. Therefore, although there is considerable genetic diversity in M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains, and their distributions are generally restricted, genetic and herbicide response information provided by MilfoilMapper has the potential to inform management decisions and practices for M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains.

Herbicide Response

The ultimate goal of MilfoilMapper is to provide a living catalog of strain distribution and herbicide response information. Currently, the number of strains characterized is small (22 out of 290 strains identified from genetic surveys) and limited to only two commonly used herbicides (fluridone and 2,4-D) (see Supplementary Table 1). While we believe MilfoilMapper will be a valuable tool to provide an important platform to serve as a repository for additional information, as well as increasing M. spicatum sensu lato control efficiency and efficacy, there are admittedly several important limitations in populating MilfoilMapper with strain information and in interpreting and utilizing that information.

The most important limitation to populating MilfoilMapper with herbicide response information is logistical difficulty associated with conducting herbicide dose–response studies. Dose–response studies for aquatic plants require considerable time and space, and it is impossible to exhaustively characterize the large number of strains for response to the number of aquatic herbicides used for invasive Myriophyllum control. Therefore, it is necessary to prioritize the strains and herbicides targeted for characterization.

Quantitative and qualitative field observations are critical for prioritizing herbicide response characterization. In fact, we initially identified all the resistant strains in MilfoilMapper through field observations. The four fluridone-resistant strains (H_MISGP_249, E_MISGP_380, H_MISGP_1443, H_MISGP_1861) and two 2,4-D strains (H_MYR_5016, H_MYR_15816) were initially brought to our attention via manager observations of low efficacy in the field and subsequently confirmed with controlled laboratory study (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Netherland and MacDonald2012; Chorak and Thum Reference Chorak and Thum2020; Thum et al. Reference Thum, Heilman, Hausler, Huberty, Tyning, Wcisel, Zuellig, Berger, Glomski and Netherland2012; GM Chorak and RA Thum, unpublished data; HK Hoff and RA Thum, unpublished data; RM Newman and J Gerritsen, unpublished data; AL Wolfe and RA Thum, unpublished data) (see Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, a 2,4-D–resistant strain (N_MYR_15319) was initially identified through quantitative field monitoring of strain composition before and after herbicide treatments (see Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, Newman and Thum2022) and was then subsequently confirmed with controlled laboratory study. We suspect there are additional strains in the field that are resistant to one or both herbicides but have not yet been identified and/or brought to our attention for characterization. Further, field observations and data to identify susceptible strains are equally important. Therefore, we strongly encourage managers to conduct genetic surveys of lakes to determine how many and which strains are present for interpretation of their control results and to consider integrating strain monitoring data into quantitative evaluations of herbicide efficacy whenever feasible.

Although MilfoilMapper lists strains as “Resistant” versus “Susceptible,” it is important to recognize that herbicide response is not binary (Thum et al. Reference Thum, Sperry, Chorak, Leon and Ferrell2023). Because there are different herbicide treatment use patterns in different states, and because the achieved efficacy of a treatment will depend on strains’ specific dose–response curves to the herbicide used, a particular strain may be satisfactorily controlled in one place with one use pattern and not in another with a different use pattern. For example, the strains currently marked as “Resistant” versus “Susceptible” to fluridone in MilfoilMapper are classified as such based on reference to the operational rate of 6 μg L−1 fluridone treatment as it is applied in Michigan (see Premo et al. Reference Premo, Batterson, Gracki, McNabb and Harrison1999), where fluridone is used more commonly than in other midwestern states. However, fluridone use for M. spicatum sensu lato control is increasing in nearby states (e.g., Minnesota and Wisconsin) but is often used at lower concentrations. Therefore, a strain labeled as “Susceptible” in reference to 6 μg L−1 fluridone may not be controlled sufficiently at a lower concentration.

Given the limitations of a binary “Resistant” versus “Susceptible” scheme for herbicide response, MilfoilMapper could be improved by reporting standardized, quantitative herbicide response values (e.g., EC50) or including more detailed dose–response information for each strain and herbicide. Currently, the available resources for M. spicatum sensu lato herbicide response characterization do not provide a centralized laboratory to conduct herbicide studies, which in turn precludes a standard protocol for herbicide characterization. The development of collaborations among multiple laboratories and the development and implementation of standardized screening procedures (including standardized reference clones) would therefore improve the utility of MilfoilMapper. Nevertheless, the current approach and information available in MilfoilMapper should provide helpful guidance for managers.

It is important to acknowledge that management decisions and efficacy are influenced by a number of site-specific characteristics besides genetic composition and that poor efficacy can be observed even on strains that are genetically susceptible to an herbicide. For example, improper dose calculation or delivery could result in failure to achieve sufficient concentration and exposure time for effective control (Nault et al. Reference Nault, Barton, Hauxwell, Heath, Hoyman, Mikulyuk, Netherland, Provost, Skogerboe and Van Egeren2018; Schardt and Netherland Reference Schardt and Netherland2021; West et al. Reference West, Burger, Poole and Mowrey1983). Similarly, dilution and dissipation of a herbicide can prevent sufficient concentration and exposure times, especially for treatments applied to small areas of a water body. Finally, the extent of herbicide degradation (e.g., temperature, light, water chemistry, and microbial composition depending on the specific herbicide) could limit the achieved concentration and exposure time.

Conclusions

Although we have identified areas for improvement, we believe MilfoilMapper will facilitate improved management efforts by providing a centralized, interactive platform for tracking M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum strains. We advocate for the integration of more widespread genetic surveying and monitoring into M. spicatum and M. spicatum × M. sibiricum management to help identify and prioritize strains with documented herbicide response as well as identifying strains to characterize for herbicide response.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2025.10032

Acknowledgments

We thank Katie Gannon, Hannah Hoff, Del Hannay, and our many undergraduate research assistants who have helped to extract DNA and input samples into the main database. We also thank Katie Gannon for her assistance with microsatellite PCRs and analyzing those data. Thank you to the Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center—especially Meg Duhr and Kate Carlson—for developing the ESRI MilfoilApp that inspired the creation of MilfoilMapper. We want to thank Jo Latimore, Michelle Flenniken, Tracy Stirling, and Del Hannay for providing thoughtful comments on initial drafts of this paper.

Funding statement

Primary funding for this project was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative Interjurisdictional Funding grant no. F22AC00106 and Department of the Army U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center ERDC Federal Award Identification Number (FAIN): W912HZ2020060 and FAIN: W912HZ-23-2-0037. Additional support was provided by the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station (project MONB00249), Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center, the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch grant MIN-41-081).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.