Many people believe that the institutions of traditional representative democracies are full of corrupt self‐dealers who cannot effectively cooperate to ‘get things done’ on important policy issues (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Hibbing & Theiss‐Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002). This scepticism of traditional politics provides an opening for politicians and other actors to cultivate public support for institutional reforms that promote alternative forms of political rule. This sometimes takes the form of politicians stoking and using mass discontent to facilitate the gradual power grab that characterizes democratic erosion (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021; Lührmann, Reference Lührmann2021). However, many attempts at institutional reform trade on a prevalent desire for a more democratic system via reforms that improve the transparency of governing procedures, increase public voice in policymaking, and promote the use of direct forms of public influence (Altman, Reference Altman2011; Merkley et al., Reference Merkley, Cutler, Quirk, Druckman and Freese2019; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020). The continued durability of democratic regimes may depend, in no small part, on which of these two impulses wins out among politicians and ordinary members of the mass public.

One increasingly prominent democratic innovation is the use of deliberative mini‐publics (DMPs) as a component of policymaking processes (Beauvais & Warren, Reference Beauvais and Warren2019; Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2009; Landemore, Reference Landemore2020; OECD, 2020). DMPs typically involve a random sample of ordinary citizens who gather to hear expert evidence and then deliberate together regarding potential policy responses. The results of these deliberations may translate directly into policy in some circumstances (Wampler et al., Reference Wampler, McNulty and Touchton2021), but more commonly influence policy indirectly through assembly recommendations (Gastil et al., Reference Gastil, Knobloch, Reedy, Henkels and Cramer2018; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006). These sorts of democratic innovations are often thought to be especially well‐suited to addressing long‐term policy issues, given that elected representatives are incentivized by the electoral cycle to worry more about short‐term concerns and re‐election prospects (Smith, Reference Smith2019). Climate change is arguably the most obvious example of this short‐termism issue, with evidence suggesting that it poses an especially large challenge in majoritarian democracies like the UK (Finnegan, Reference Finnegan2022; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Curato and Smith2022). It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the use of ‘Citizens’ Climate Assemblies’ has become a common demand of environmental groups (e.g., Extinction Rebellion), think‐tanks and scholars (see, for example, Adachi, Reference Adachi2019). We therefore focus our study on ‘climate assemblies’ – DMPs intended to help address climate change, a pressing policy issue that is among the most common topics addressed in mini‐publics (European Climate Foundation, 2021; Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2021).

While DMPs are not without critics (e.g., Machin, Reference Machin2023; Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2017), one of their central justifications rests on their ability to ‘promote the legitimacy of collective decisions’ (Gutmann & Thompson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004). This argument has inspired a nascent literature focused on the public's perceptions of DMP legitimacy (Bedock & Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2021; Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O'Leary and Tilley2022; Germann et al., Reference Germann, Marien and Muradova2024; Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023; Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Már & Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2023; Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020; Rojon et al., Reference Rojon, Rijken and Klandermans2019; Van Dijk & Lefevere, Reference Dijk and Lefevere2023). Existing work finds that non‐participants view deliberative events more positively when they see people like themselves in the forum (Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020), when they distrust politicians and traditional political institutions (Bedock & Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2023; Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023) and when they agree with the policy positions that the DMP has adopted (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022).

One important element that past research has broadly neglected concerns the origins of DMPs (but see Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023, whom we discuss below). Deliberative events, such as climate assemblies, are still relatively uncommon and hence must be proposed and implemented by policy entrepreneurs. These actors may be ordinary citizens, activists, interest groups or more explicitly, partisan actors such as elected officials (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006). Mini‐publics thus differ in how ‘coupled’ they are to existing democratic institutions and patterns of partisan conflict (Kuyper & Wolkenstein, Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019). This is important because DMPs are political institutions and, as such, may generate elite conflict regarding their legitimacy and the legitimacy of their policy proposals (Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O'Leary and Tilley2022; Landemore, Reference Landemore2020). But do the origins of a given climate assembly affect perceptions of the institution's policymaking legitimacy?

We build on existing theory and empirical analyses to hypothesize that evaluations of deliberative events, such as climate assemblies, will be influenced by prior attitudes toward the actors involved in creating them. First, we expect that reactions will be more positive when elected representatives create assemblies in response to demands from non‐partisan actors (e.g., residents in their constituency), since politicians in this scenario may be judged as upholding important democratic norms such as responding to mass input (Lapinski et al., Reference Lapinski, Levendusky, Winneg and Jamieson2016). Second, we expect that evaluations toward the specific political parties involved will be correlated with evaluations of the DMP, and especially so when partisan conflict is present. Individuals may use partisan cues (i.e., which party is setting up the assembly) to make inferences about how the DMP will be conducted and whether they will agree with the DMP's policy recommendations, such that a DMP will be judged more positively when originating from a liked party than a disliked party. Partisan conflict, in turn, should deepen the connection between attitudes toward the parties involved and assembly evaluations by further motivating individuals to adopt attitude‐consistent preferences (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Slothuus & De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010).

We test these expectations using two pre‐registered survey experiments fielded via Prolific in the United Kingdom.Footnote 1 Respondents in the experiments were asked to evaluate a proposed climate assembly wherein we independently varied: (1) whether the assembly was initially proposed by local residents or the majority party of a local city council; (2) whether the majority party on the council was Labour or Conservative; and (3) whether the two main parties explicitly disagreed about whether to implement the mini‐public. We find some evidence that assemblies are more positively evaluated when they stem from the demands of local residents rather than partisan actors, but this effect is relatively modest and does not emerge consistently across our analyses. Similarly, the partisanship of the party proposing the DMP does not appear to have had a robust effect on reactions either. The presence of elite conflict, by contrast, led respondents to adopt more ideologically stereotypical views of the assembly – with left‐wing (right‐wing) respondents being more supportive of Labour‐sponsored (Conservative‐sponsored) assemblies. This suggests that ‘coupling’ deliberative institutions to traditional party politics in contexts where there is partisan disagreement over DMPs may pose a challenge to their ability to transcend existing ideological cleavages within society.

Mini‐publics and legitimacy

DMPs represent an important case where normative theorizing, in this instance the ‘deliberative turn’ in political theory, directly inspired worldwide experimentation in democratic practice (OECD, 2020). A large body of empirical research has subsequently focused on studying DMP participants (Barabas, Reference Barabas2004; Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Siu, Diamond and Bradburn2021; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Kolk, Carty, Blais and Rose2011; Karpowitz & Mendelberg, Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Luskin et al., Reference Luskin, Sood, Fishkin and Hahn2022). Here, crucial debates concern whether participation is unequal across social groups and whether deliberation enhances the quality of participants’ attitudes.

While it is important to understand the effect of deliberation on deliberators, the purpose of many deliberative institutions is not simply to generate ‘enlightened’ collective opinions, but rather to affect policymaking (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Kuyper & Wolkenstein, Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019). This can occur in various ways. DMPs, for instance, may draw up policy recommendations that non‐participants can use as a voting aid – leading some researchers to investigate whether non‐participants learn from, and are persuaded by, these recommendations (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2017; Gastil et al., Reference Gastil, Knobloch, Reedy, Henkels and Cramer2018; Ingham & Levin, Reference Ingham and Levin2018; Suiter et al., Reference Suiter, Muradova, Gastil and Farrell2020). Alternatively, mini‐publics may be more tightly connected to legislative policymaking institutions, either by directly making policy or (more commonly) by offering legislators a way to obtain information about public opinion (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006; Wampler et al., Reference Wampler, McNulty and Touchton2021). A central focus for empirical research in this vein concerns whether non‐participants believe mini‐publics are legitimate policymaking institutions and want DMP recommendations to be converted into policy (Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023; Már & Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2023; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020; van Dijk et al., Reference Dijk, Turkenburg and Pow2023; Van Dijk & Lefevere, Reference Dijk and Lefevere2023; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Our focus is on this latter issue: when do non‐participants grant policymaking legitimacy to DMPs such as climate assemblies?

Granting DMPs policymaking legitimacy may seem odd at first glance given that their participants are electorally unaccountable to non‐participants (Lafont, Reference Lafont2015). However, existing research identifies two potential sources of DMP legitimacy, both of which are consistent with broader theories of institutional legitimacy (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006). First, individuals evaluate deliberative institutions instrumentally. Non‐participants feel more positively about DMPs that deliver their preferred policy outputs (Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Non‐participants also evaluate DMPs more positively when they anticipate policy agreement based on what they know about participants (Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020).

Second, procedural considerations also impact evaluations of DMPs. On the one hand, mini‐publics satisfy what appears to be a general preference for citizen participation in policymaking, and are consequently associated with more positive evaluations when compared to processes that do not involve direct citizen input (Christensen, Reference Christensen2020; Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O'Leary and Tilley2022; Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). On the other, procedural considerations also matter insofar as they shape the perception that the process involved was fair and unbiased, just as occurs with other policymaking institutions (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006). While instrumental considerations may generally have a stronger impact on evaluations than procedural ones, factors that promote perceived fairness and unbiasedness are important because they may improve legitimacy perceptions even among those who stand to lose from the institution's actions (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Linholm2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022).

Taking these points together suggests that individual‐level perceptions about assembly recommendations and the procedures used to generate those recommendations are likely to shape public responses to DMPs.

Theorizing about the (partisan) origins of climate assemblies

As climate assemblies are typically not institutionalized, some type of policy actor (or actors) needs to advocate for one to be held; this could be partisan actors, such as elected officials, or actors outside of government, such as ordinary citizens. More broadly, there is considerable variation in the partisanship of those who propose DMPs: while empirical research suggests that left‐wing and Green politicians are more favourably inclined to these measures (e.g., Bottin & Schiffino, Reference Bottin and Schiffino2022; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022), a number of prominent cases of DMPs have in fact been pushed forward by cross‐partisan support (for an overview, see Nissan, Reference Nissan, Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023). But does variation in the origins of DMPs shape how non‐participants evaluate the legitimacy of these assemblies?

Most existing research has ignored the potential impact of assembly origins. The sole exception, to our knowledge, considers whether non‐participants react differently to a DMP initiated by ‘the government’ versus an (unnamed) NGO (Goldberg & Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023).Footnote 2 While that analysis generated several important insights, our focus here is on a comparison between DMPs that were initiated by specific partisan actors in government (i.e., legislators from named political parties) versus those that were advocated for by ordinary citizens. A reference to ‘the government’ may imply to participants a consensus among government actors, which may give an additional sheen of legitimacy to the institution. However, DMPs typically stem from the actions of specific partisan teams in the legislature. The UK's 2020 Climate Assembly, for instance, was the initiative of select committees in the Conservative‐dominated House of Commons. Partisan actors, meanwhile, are unlikely to always be in agreement about the need for a specific DMP or the potential legitimacy of its outputs, as Landemore's (Reference Landemore2020) discussion of DMP experiences in Iceland and France demonstrates.

Furthermore, we consider the potential influence of whether the assembly stemmed from public pressure. Many DMPs are initiated at the behest of the public: Parkinson (Reference Parkinson2006), for example, analyzes cases of deliberative institutions in the UK that vary in this way, including efforts by the Labour Party to implement a health‐service related citizen jury in the wake of public protest regarding proposed changes to local hospital service. Furthermore, it is plausible that non‐participants will care about which segment of civil society is pushing for a DMP, with NGOs perhaps treated with more suspicion than other groups. Many people are distrustful of ‘interest groups’ and see them as a source of corruption (e.g., Hibbing & Theiss‐Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002), which may explain some of the preference for government‐initiated DMPs noted in Goldberg and Bächtiger (Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023). Whether non‐participants react the same to initiatives stemming from public demand remains unclear.

We hypothesize that evaluations of a mini‐public will be more positive when they originate from public pressure (i.e., from ordinary citizens) rather than from partisan actors (i.e., political parties). There are two reasons to suspect this may be the case. First, many people hold negative attitudes regarding politicians and political parties (Bøggild, Reference Bøggild2020; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018). DMPs originating from public demand may thus benefit simply from being comparatively disassociated from party politics. Second, many in the mass public believe that responding to public opinion is an important element of democratic representation and practice (Bengtsson & Wass, Reference Bengtsson and Wass2010; Harden, Reference Harden2016; Lapinski et al., Reference Lapinski, Levendusky, Winneg and Jamieson2016). A mini‐public demanded by the public and then adopted by existing institutional actors may therefore be evaluated more positively because it coheres with this broader political norm.

-

H1 Attitudes toward the climate assembly will be more positive when the assembly is portrayed as emanating from the desires of local residents than when it is portrayed as coming from a partisan source

Our remaining hypotheses focus on contexts wherein a DMP originates wholly from the efforts of partisan actors. Here, we anticipate that evaluations will be shaped by (1) attitudes toward the political parties involved and (2) the extent of salient partisan conflict surrounding the DMP's creation.

First, we expect that individuals will react more positively (negatively) to a climate assembly initiated by a political party that they like (dislike). Evaluations of deliberative mini‐publics track with perceptions of their likely policy outputs, which have been shown to be influenced, for example, by assumptions about participants (Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020). The party involved in creating the mini‐public may serve as a similar signal, with individuals who like the party being more inclined to assume that their policy views will be represented. For related reasons, orientations toward the parties organizing a mini‐public may also influence beliefs about the procedural qualities of the DMP. As per our earlier discussion, ordinary people may look favourably on a mini‐public because its characteristics meet the demands of a procedurally just institution (e.g., a lack of bias and the presence of high‐quality information). However, observers need to believe that these putatively fair procedures were actually fair in their execution. The presence of a liked political party in the creation of the DMP may reassure people that the assembly will work as intended, while the presence of a disliked party may raise concerns that the assembly will be procedurally just in name only, due to a distrust that the party would create an assembly that could hinder its political interests. Finally, affect toward the parties involved may also operate through identity‐based processes, wherein partisans adopt evaluations consistent with their ideological stance and broader partisan allegiances (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Sio, Paparo and Tucker2020; Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014).

Second, we anticipate that elite partisan conflict over the assembly's creation will strengthen the relationship between attitudes toward the parties and evaluations of the climate assembly. Existing work on party cues and conflict is consistent with this claim. Although DMPs typically find more support among left‐wing and Green elected representatives (see, for example, Bottin & Schiffino, Reference Bottin and Schiffino2022; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022), several prominent case studies have been marked by a focus on building a cross‐partisan consensus in order to increase the likelihood that the DMP will be successful (for a discussion, see Nissan, Reference Nissan, Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023). On the one hand, such an approach is likely seen to be key to building cross‐party support for eventually implementing DMP recommendations. On the other hand, it also points to potential concerns about the perceived impact of partisanship on assembly implementation in cases of partisan disagreement – arguably reflecting the worry, alluded to above, that ‘the topic for discussion, the timing, the material, and other practical details are entirely arranged “top down” by the authorities’ (Machin, Reference Machin2023, p. 853). We thus expect partisan conflict to enhance both the informational clarity and usefulness of party cues (Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010; Slothuus & De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010), as well as the power of identity‐based motivations to adopt the party line (Bolsen et al., Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). Taken together, these points lead us to our final two hypotheses.

-

H2 Attitudes toward the climate assembly will be more (less) positive among respondents with positive (negative) attitudes toward the majority party in charge of the assembly

-

H3 The presence of explicit partisan conflict will strengthen the relationship between prior party evaluations and assembly evaluations

Study 1

Sample

We test our hypotheses using a vignette experiment fielded in the UK; an anonymized version of our pre‐registration document is available via the link in the endnote.Footnote 3 We sampled 1500 respondents using Prolific's opt‐in online panel, with data collection occurring from July 20–26, 2022. The sample was created using quota sampling methods to ensure that our respondents reflected the broader sex, age and ethnicity characteristics of the UK population (see Table OA1 in the Supporting Information Appendix for sample characteristics). Data from Prolific samples tends to be of high quality (Peer et al., Reference Peer, Rothschild, Gordon, Evernden and Damer2022) and experimental results conducted on convenience samples tend to reproduce results found using probability based samples (Coppock et al., Reference Coppock, Leeper and Mullinix2018; Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015). The sample is nevertheless not a random probability based one, which restricts our ability to make strong generalizations to the broader UK population.

Procedures

We first asked respondents a series of questions regarding their educational attainment and region of residence, attitudes about climate change and broader political attitudes such as their left‐right ideology, trust in politicians and affect toward various groups (including Labour and Conservative politicians). Next, respondents took part in a separate experiment regarding climate assemblies, which opened with an introductory text providing general information about what they are (Már & Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2023). This general introduction should mitigate against pre‐existing differences in knowledge affecting subsequent reactions, and read as follows:

Around the world, different cities, states, and nations are experimenting with the use of citizens’ climate assemblies. These are assemblies made up of randomly selected citizens that carefully study issues related to climate change, then make recommendations or decisions. In every case, these bodies hear from advocates for and against policies, get to discuss issues with policy experts, and have ample time to deliberate among themselves over several days or weekends.Footnote 4

Respondents then read the vignette at the heart of this study and answered a series of additional questions.

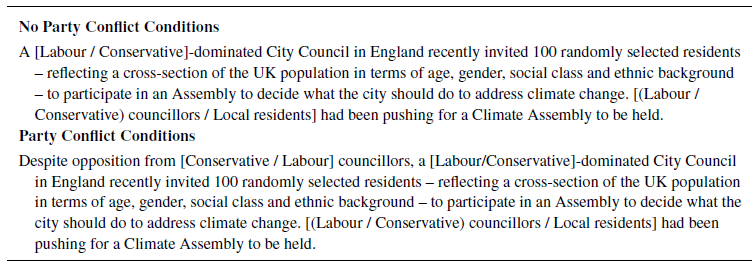

The experimental vignette featured a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design (see Table 1 for vignette wordings) centred around a climate assembly proposed by a local council. Our focus on the local level is motivated by two considerations. The first is empirical: lower‐level governments appear to be particularly keen to use DMPs, with over a dozen climate assemblies organized by local authorities in the UK over the last few years alone (King & Wilson, Reference King and Wilson2023). The second is theoretical, with a number of scholars arguing that local DMPs hold particular promise for improving democratic governance due to their greater likelihood (relative to national DMPs) of actually impacting public policy (Michels & Binnema, Reference Michels and Binnema2019).

Table 1. Vignette wordings, study 1

Note: Information in brackets is randomly assigned. If a respondent is assigned to hear that a partisan source ‘had been pushing’ to hold the assembly, the source was always the same as the majority party.

There are three sources of variation in the experimental vignette. The first concerned who was ‘pushing for the Climate Assembly to be held’, with half of respondents reading that it was ‘local residents’ and the other half reading that it was councillors from the majority party on the council. Second, we varied the identity of the majority party, with half reading that this was the Labour Party and the other half the Conservative Party. Finally, we varied the salience of elite partisan conflict surrounding the institution by altering the first line of the vignette: while respondents in the No Party conflict conditions simply read that the Labour or Conservative Party was involved, those in the Party Conflict conditions read that this assembly was held ‘despite opposition from’ the other major party (i.e., from Conservatives if in the Labour council conditions, or Labour if in the Conservative council conditions).

The vignette then concluded with text informing respondents that ‘After hearing expert testimony, weighing evidence, and debating the best course of action, the Assembly recommended a series of measures designed to reduce the carbon footprint of residents, the city government, and local businesses’.

Measures and models

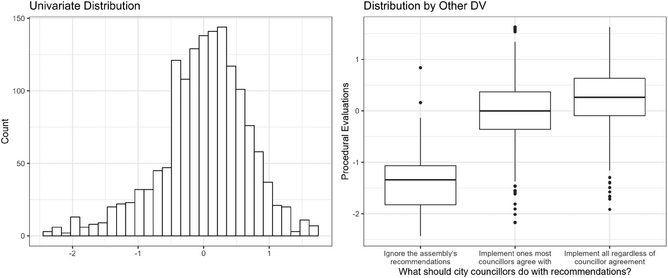

We examine two dependent variables included immediately after the vignette. The first, preferred bindingness, is based on a single item wherein respondents were asked what they think the City Council should do with the recommendations from the assembly: ‘ignore the assembly's recommendations’; ‘implement the recommendations that most councillors agree with’; or ‘implement all of the recommendations, regardless of whether most councillors agree with them’. These options represent increasing levels of binding authority for the assembly. The dominant response from respondents was that councillors should filter out the recommendations that they do not agree with (n = 969, 64.6 per cent). The remainder of respondents predominately supported giving the assembly the most power (i.e., completely bypassing partisan control; n = 452, 30.1 per cent), with very few respondents saying that councillors should totally ignore the assembly's recommendations (n = 79, 5.3 per cent).

Respondents were then asked for their level of agreement (0 = totally disagree, 10 = totally agree) with five statements that capture our second dependent variable, procedural evaluations: (1) people who share your views on climate change were given a say in the decision‐making process in the assembly; (2) on the whole, no one interest or point of view seemed to have more input and consideration than others in producing the assembly's recommendations; (3) the process through which this decision was reached was illegitimate; (4) the assembly did not take the necessary steps to come to an informed decision; and (5) I trust the assembly to make good decisions about climate change. These items tap into beliefs about the procedural quality of the assembly (e.g., how fair and unbiased its procedures were), which is a crucial predictor of institutional legitimacy and support (Gangl, Reference Gangl2003; Tyler, Reference Tyler2006). Our procedural evaluations dependent variable is thus an index of these five variables (with the two negatively valanced items above reverse scaled) created via confirmatory factor analyses (M = 0, SD = 0.67), such that higher values indicate more positive evaluations (see Supporting Information Appendix A for further details).

Figure 1 plots the procedural evaluations index's univariate distribution, as well as its distribution by respondent answers to our other dependent variable. Results indicate that attitudes regarding the assembly's procedures are positively correlated to respondent preferences regarding its policymaking influence.

Figure 1. Distribution of procedural evaluations regarding climate assembly, study 1.

Our primary independent variables are three binary indicators for treatment assignment: the first pertaining to whether the assembly was initially pushed for by local residents (= 1) rather than a political party (= 0); a second capturing whether the council was Labour (= 1) or Conservative (= 0) dominated; and a third indicating whether there was salient conflict (= 1) or not (= 0).

We argued in Hypotheses 2 and 3 that prior party attitudes will influence reactions. We make use of two measures from the pre‐test to examine this hypothesis. Respondents were asked to rate Labour and Conservative politicians on a feeling thermometer (range: 0‐100). While respondents did not express unbridled love for Labour politicians (mean = 40.98, standard deviation = 25.64), attitudes were nevertheless notably more favourable toward them than toward Conservative politicians (mean = 23.87, standard deviation = 24.50). We constructed a difference score tapping party affect to test Hypotheses 2 and 3: Majority Party Thermometer ‐ Minority Party Thermometer, where ‘Majority Party’ represents the party dominating the city council in the vignette the respondent was assigned to and ‘Minority Party’ represents the other party (mean = −0.85, standard deviation = 41.29, range: −98, +100). For example, if a respondent was assigned to a condition where the Conservatives dominated the city council, then this measure is formed as follows: Conservative Politicians Thermometer ‐ Labour Politicians Thermometer. We focus on a standardized version of this measure (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1) to facilitate interpretations below.Footnote 5 We also perform follow‐up analyses focused on assessing the effects of the party thermometers separately as well as the impact of party identification (see Supporting Information Appendix A).

In our main analyses, we perform linear regressions using indicators for treatment assignment and the party difference score as predictor variables.Footnote 6 We also control for four pre‐test covariates per our pre‐analysis plan: sex, education, age and trust in politicians. In theory, this approach should increase the precision of our resulting estimates, given that these covariates typically predict support for DMPs (Bedock & Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2021, Reference Bedock and Pilet2023; Garry et al., Reference Garry, Pow, Coakley, Farrell, O'Leary and Tilley2022; Gerber & Green, Reference Gerber and Green2012; Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Pow et al., Reference Pow, Dijk and Marien2020).

Hypothesis 1 results

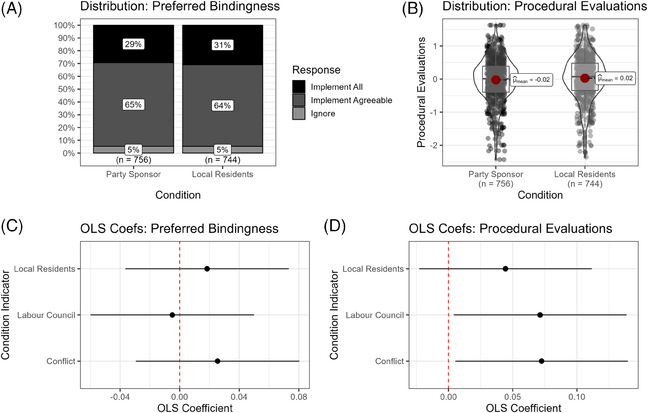

We argued in H1 that reactions to the climate assembly would be more positive when the assembly originated from public pressure rather than as a partisan initiative. We provide a summary of our analyses on this front in Figure 2. The top plots in Figure 2 illustrate the distribution of each dependent variable (DV) broken down by whether the respondent was assigned to the Local Residents or Party Sponsor conditions. The bottom panels, meanwhile, provide ordinary least squares (OLS) coefficients for our three treatment indicators; full model results, including coefficients for the pre‐treatment covariates, are provided in Supporting Information Appendix OA1. Arguably the most notable finding in Figure 1 is the substantial proportion of respondents who indicated that the assembly's recommendations should simply be accepted by politicians on the local council. Ultimately, however, Figure 2 provides little evidence that the initial sponsor of the assembly mattered for subsequent interpretations, either in bivariate or multiple regression tests. The distribution of responses is virtually identical across conditions, with a null OLS coefficient.

We did not hypothesize a priori that the effect of sponsor type would depend on the party in question. However, we performed exploratory analyses to examine whether the null results shown in Figure 2 could be explained by differences in attitudes toward Labour‐ versus Conservative‐dominated councils (see Supporting Information Appendix A). In doing so, we did find some evidence that reactions to the sponsor information depended on which party dominated the council: respondents tended to react more positively to a residents‐sponsored assembly than a Labour‐sponsored assembly (difference on preferred bindingness: 0.07 [−0.01, 0.15]; difference on procedural evaluations: 0.10 [0.001, 0.19]); whereas sponsorship had no effect when the council was Conservative dominated (preferred bindingness: −0.03 [−0.11, 0.04]; procedural evaluations: −0.01 [−0.10, 0.09]).

Figure 2. Hypothesis 1 analyses, study 1.

Notes: Plots on top (A and B) provide the distribution of the DVs according to sponsor condition. Plots on the bottom (C and D) provide OLS coefficients for assignment to each of the three treatment conditions. See Table OA3 for full model results.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 results

We argued in H2 that prior attitudes toward the parties involved in the creation of a climate assembly would correlate with assembly evaluations, while H3 suggested that this relationship would be stronger when partisan conflict was salient. We examine H2 by regressing our dependent variables on the relative party evaluations score discussed above, indicators for whether the council was Labour or Conservative dominated and whether there was explicit partisan conflict, and pre‐test covariates. We add an interaction term between relative party evaluations and the indicator for salient conflict in a second model to examine H3. We restrict these analyses to respondents who were assigned to a Party Sponsor condition per our pre‐analysis document.Footnote 7

Figure 3 provides an overview of results pertaining to these two hypotheses (see Table OA5 for full model results). The upper panels assess H2 by providing the OLS coefficients for the (relative) party evaluations score, the majority party condition, and the party conflict condition. A positive coefficient for the party evaluations score would be consistent with H2, as this would indicate that reactions to the assembly grew more positive as the ratings of the majority party (relative to the minority party) grow more positive. Figure 2 does not provide any evidence of this hypothesized relationship, however: the coefficients for party evaluations are close to zero in substantive terms and statistically insignificant. Prior party attitudes were unrelated to both preferred bindingness and procedural evaluations.

Figure 3. Hypotheses 2 and 3 analyses, study 1.

Notes: Plots A and B provide OLS coefficients for three variables to examine H2: relative party evaluations, Labour vs. Conservative dominated council, and (partisan) conflict vs. no conflict. Plots C and D plot the marginal effect of the party evaluations variable by conflict condition from a model with an interaction term between the two variables. See Table OA5 for full results.

The lower panels in Figure 3 lay out results pertaining to H3. Here we plot the marginal effect of the party evaluations item separately for those in the No Conflict and Party Conflict conditions. Evidence consistent with H3 would manifest in a more positive coefficient for the party evaluation item in the Conflict condition (in comparison with the No Conflict condition). As illustrated in the Figure, the relationship between party evaluations and each DV is estimated as negative in the No Conflict conditions but positive in the Party Sponsor conditions – yet these effects are not themselves statistically significant. The interaction term is positive in both cases but is only statistically significant in the model focused on preferred bindingness. These results are broadly consistent with H3 in that party attitudes mattered more in contexts of conflict, though even in this case their effect was relatively weak.

Exploratory analyses: Effects by respondent ideology

Attitudes toward political parties, and party cues, routinely predict political attitudes and behaviour (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Sio, Paparo and Tucker2020; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021). Why was the role of party attitudes so weak in the present case?

Exploratory analyses reported in Supporting Information Appendix A concerning the role of partisan identification as well as the Labour and Conservative thermometer items separately suggest one potential explanation: respondents may have been reacting more based on their ideological attitudes than their party attitudes. Past research has come to mixed conclusions about the effect of ideology on support for DMPs (Walsh & Elkink, Reference Walsh and Elkink2021). However, research on climate attitudes commonly shows a left‐right divide with those on the left typically being more concerned with – and supportive of ameliorative policies regarding – climate change (Egan & Mullin, Reference Egan and Mullin2017; McCright et al., Reference McCright, Dunlap and Marquart‐Pyatt2016). One possibility is that partisan conflict regarding a climate‐focused DMP may cue individuals about the potential implications of the assembly for their ideological attitudes, with support (or opposition) following suit (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus and Togeby2010).

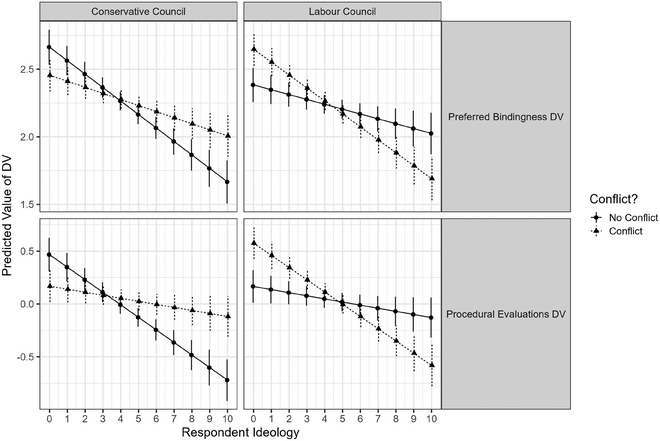

To assess this possibility, we use a pre‐test measure of respondents’ ideological identification on the left‐right scale (0‐10; higher = more right‐wing) to examine the interaction between treatment assignment and ideology. We regressed each DV on this measure, the full set of interactions between it and both the conflict and dominant party condition indicators, as well as controls for Local Residents vs. Party Sponsorship and the pre‐test covariates. Figure 4 provides the key results by plotting the predicted values along the left‐right spectrum for our two dependent variables (top and bottom panels), broken down by council majority (left and right panels) and conflict condition (circle = No Conflict, triangle = Party Conflict).

Figure 4. Ideology as moderator, study 1 (exploratory analyses).

Notes: Markers provide the predicted value of each dependent variable (top plots: Preferred Bindingness DV, bottom plots: Procedural Evaluations) by left‐right ideology (x‐axis). Left‐hand panels focus on treatments where the Conservative Party is the majority party on the Council, right‐hand panels focus on treatments where Labour is dominant. Separate lines/markers are provided for conditions of no partisan conflict (circular marker, solid line) and salient conflict (triangular marker, dashed line). Markers are offset for display purposes. Full model results are provided in Table OA16.

The results in Figure 4 suggest that attitudes toward the climate assembly are in all cases more negative among those on the right than those on the left. However, the size of the ideology effect varies based on the party in charge of the council and the salience of partisan conflict: partisan conflict increases ideological differences when Labour is the dominant party, while it decreases it when the Conservatives are in charge. Right‐wing respondents, for instance, tended to report more positive evaluations when the Conservative Party dominated the council and conflict between it and the Labour Party was salient (relative to when it was absent). Conversely, these respondents tended to more be critical of the DMP when Labour was the dominant party and conflict was salient (rather than absent). Similar patterns emerge for left‐wing respondents.

Figure 4 is thus consistent with our broader argument but suggests that our initial focus on partisanship – rather than ideology – was misplaced in this context.Footnote 8 We examine this possibility further in Study 2.

Study 2

Research design

Study 2 was fielded from 29 March to 04 April, 2023 using the same sampling procedure as Study 1: a quota sample of 1500 respondents from Prolific, with respondents who completed the first survey excluded from the eligible panel; see Table OB1 for sample characteristics. We also used a similar (pre‐registered) research design.Footnote 9 Study 2 thus allows us to broadly assess the replicability of the initial study, while also incorporating three changes to further investigate the patterns discussed above.

First, we slightly re‐worded the vignette text to foreground the actor pushing for the climate assembly. In Study 1, information about the initial sponsor of the climate assembly was provided after the information about the assembly (see Table 1). Respondents in the Local Residents sponsorship condition, however, were significantly less likely to correctly answer a post‐test recall question about who was ‘pushing’ for the assembly.Footnote 10 This led to a concern that the placement of the sponsorship information at the end of the vignette may have depressed related effects. Indeed, exploratory analyses presented in Supporting Information Appendix A are consistent with this reading, as we found stronger evidence for H1 when we restricted our sample to respondents who correctly answered the post‐test recall item. We therefore moved the sponsorship portion of the treatment to the beginning of the vignette for Study 2, using the formulation ‘Some local [residents / Conservative councillors / Labour councillors] have been urging their City Council in England to create an assembly to address climate change’. The rest of the vignette remained the same as in Table 1 (see Table OB2 for wordings).

Second, we added an item to the post‐test to capture whether respondents were using information from the vignette to make inferences about the policy recommendations of the climate assembly. Specifically, we asked respondents how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement on a scale ranging from 0 (totally disagree) to 10 (totally agree), ‘The type of assembly just described is likely to recommend policies that would help people like me’. We analyze this item on policy inferences separately from our two core dependent variables, as per our pre‐analysis plan.

Finally, we added left‐right ideology to our model specification and pre‐registered an additional related hypothesis. We consistently found in Study 1 that ideology was negatively associated with preferred bindingness and procedural evaluations. We therefore set out to assess whether left‐wing (right‐wing) respondents would react less (more) critically to the climate assembly in Study 2 as well. Furthermore, we found some evidence in our Study 1 exploratory analyses to suggest that the party treatments may have influenced this relationship. We thus formulated the hypothesis that the presence of partisan conflict would lead those on the political left (right) to report more positive attitudes when the Labour (Conservative) Party controlled the city council implementing the assembly.

Hypothesis 1 analyses

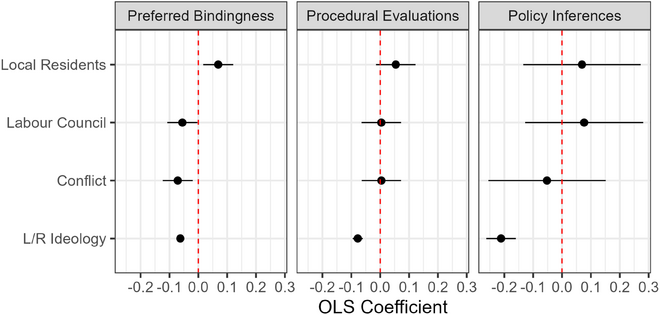

We begin with analyses pertaining to H1 (i.e., evaluations of the climate assembly will be more positive when the assembly was called for by local residents). We regressed our dependent variables (preferred bindingness, procedural evaluations, and policy inferences) on the three treatment indicators, left‐right ideology, trust in politicians, age, sex and education (with all covariates measured on the pre‐test). Figure 5 summarizes these analyses by providing the OLS coefficient for the three treatment indicators and for left‐right ideology (see Table OB3 for the underlying models).

Figure 5. Hypothesis 1 analyses, study 2.

Notes: Markers provide the OLS coefficient for each variable based on the models in Table OB3.

There are two key results in Figure 5. First, respondents tended to report more positive evaluations of the climate assembly when local residents were the ones pushing for the assembly, although this difference was only statistically significant when examining preferred bindingness. Second, we find the expected relationship between ideological identification and each of the three dependent variables. Right‐wing respondents evaluated the assembly more negatively than left‐wing respondents across all three outcome measures, with each coefficient statistically significant. Note that neither pattern is affected by restricting our focus to respondents who correctly answered the post‐test recall item about who ‘pushed’ for the assembly, and the influence of sponsorship did not depend on which party dominated the council (see Supporting Information Appendix B).

Hypotheses 2 and 3 analyses

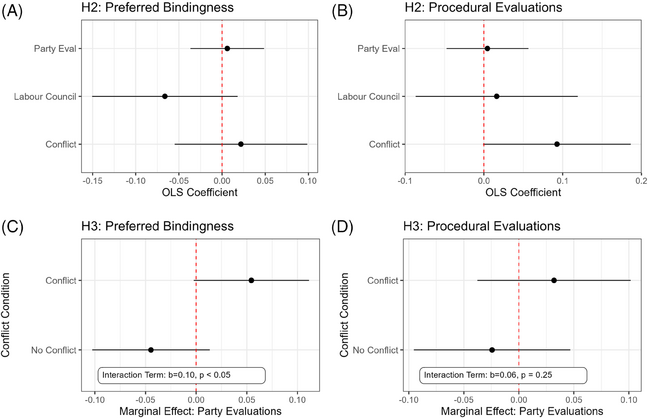

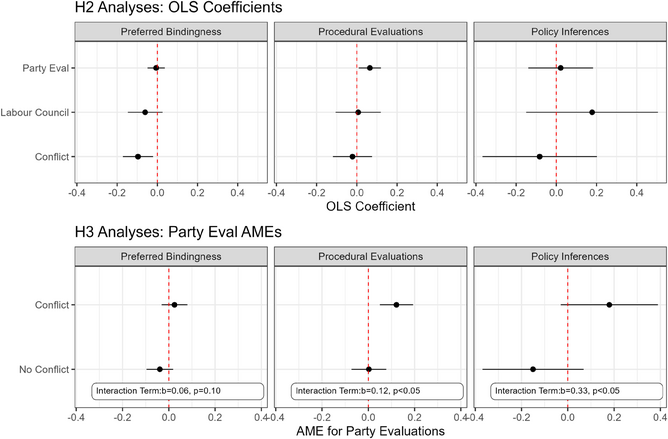

We now examine H2 (i.e., prior attitudes toward the parties involved will influence responses to the assembly) and H3 (i.e., partisan conflict will increase the party evaluation effect), with Figure 6 summarizing the key results (for the underlying models, see Tables OB7 and OB8 respectively). We restrict these analyses to respondents in the Party Sponsor condition, as indicated in our pre‐analysis plan.

Figure 6. Hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3 analyses, study 2.

Notes: The top row of plots show the marginal effects of each variable by dependent variable. The bottom row provides the marginal effect of party evaluations by conflict condition. See Tables OB7‐OB8 for full model results.

The graphs in the top half of Figure 6 provide the coefficients for respondents’ relative evaluations of the two parties (higher = more favourable toward the dominant party) and treatment indicators for the other two conditions. A positive coefficient for the party evaluations predictor would be consistent with H2. We see evidence consistent with this hypothesis regarding procedural evaluations (b = 0.06 [0.01, 0.12]), as warmer party evaluations of the majority party are associated with more positive procedural evaluations. This effect does not extend, however, to either preferred bindingness (b = −0.01 [−0.05, 0.04]) or policy inferences (b = 0.02 [−0.14, 0.018]). The evidence in favour of H2 thus remains rather modest, much as in Study 1.

The bottom half of Figure 6 examines whether the relationship between party evaluations and our outcome variables is stronger when party conflict is salient than when it is not (H3). In line with this expectation, the relationship between party evaluations and each outcome measure is statistically insignificant when partisan conflict is absent.Footnote 11 This relationship is consistently more positive in the Party Conflict conditions, with two of the three interaction terms statistically significant at conventional levels. Even here, however, party evaluations only have a statistically significant direct effect on the procedural evaluations outcome measure, suggesting that party attitudes played a relatively minor role in shaping respondents’ reactions.Footnote 12

Ideology analyses

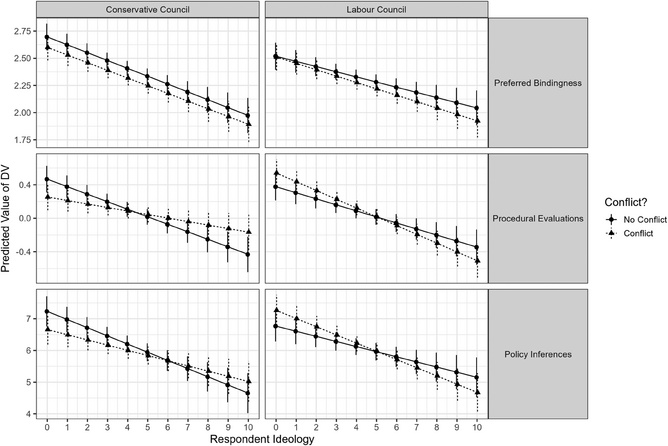

Our exploratory analyses of Study 1 suggested that respondent ideology might be interacting with treatment assignment to shape reactions to the assembly. We hypothesized that the presence of partisan conflict might increase ideological polarization based on these analyses. We are especially interested in whether those on the political right (left) reacted more positively when the Conservative Party (Labour Party) was creating the assembly against the wishes of the opposing party. We investigate this possibility in Figure 7, which reports predicted values along the left‐right spectrum for our dependent variables, broken down by council majority and conflict condition (see Table OB9 for the underlying models).

Figure 7. Ideology as moderator, study 2.

Notes: Markers provide the predicted value of each dependent variable by left‐right ideology (x‐axis). Left hand figures focus on treatments where the Conservative Party is the majority party on the Council, right‐hand figures focus on treatments where Labour is dominant. Separate lines/markers are provided for conditions of no partisan conflict (circular marker, solid line) and salient conflict (triangular marker, dashed line). Markers are offset for display purposes. Full results are reported in Table OB9.

If the party in charge of the council and the existence of partisan conflict are interacting to affect the strength of the relationship between ideology and the DVs, we would expect to see two patterns on display in Figure 7. First, when the Conservative Party is described as having the majority and conflict is salient, those on the right should be more favourable toward the assembly when Labour is opposed to it, as the presence of Labour opposition signals that the assembly aligns with their ideological interests; while those on the left should take a similar signal from Labour's stance and react in the opposite manner. Second, we would expect to find the inverse pattern when the Labour Party is described as having the majority.

Figure 7 provides modest evidence aligned with these expectations relative to procedural evaluations and policy inferences, but not preferred bindingness. The slope for ideology is essentially the same regardless of party or conflict condition when examining respondents’ levels of preferred bindingness. For procedural evaluations and policy inferences, on the other hand, the effect of ideology seems to vary based on which party is in charge of the council and whether there is salient partisan conflict. For instance, the slope for ideology is steeper for the Conservative majority conditions without salient partisan conflict, as conflict generates less support among those on the left and more among those on the right. The inverse pattern emerges when Labour is in charge: here the presence of conflict is associated with more support among left‐wing respondents and less among right‐wing respondents. And while the difference in effect sizes between the Party Conflict and No Conflict conditions only attains statistical significance in one instance (Conservative Council & Procedural Evaluations: difference between ideology effects = 0.05, p < 0.01), it is difficult to say whether the lack of a more consistent effect is simply the result of our limited power here, as three‐way interactions tax the analytical power of even reasonably large samples.

Conclusion

Commentators, politicians, and even researchers have increasingly come to worry that traditional representative democracy may be incapable of addressing the most pressing challenges of our time (see, for example, Adachi, Reference Adachi2019). Climate collapse is perhaps the clearest example of this: despite the scientific consensus on global warming, government action has been lacklustre, especially in majoritarian democracies like the UK (Finnegan, Reference Finnegan2022). Climate assemblies, which give ordinary people direct influence over environmental policies (Ackerman & Fishkin, Reference Ackerman and Fishkin2004; Beauvais & Warren, Reference Beauvais and Warren2019; Landemore, Reference Landemore2020), offer one potential solution. These DMPs have been a key demand of many environmental groups, and the UK, among other countries, has taken modest steps in this direction (Willis et al., Reference Willis, Curato and Smith2022). Yet if these assemblies are to overcome the current political gridlock, their decisions must impact policy. Past research suggests that this will require greater support for binding DMPs, both among the public and policymakers (Pogrebinschi & Ryan, Reference Pogrebinschi and Ryan2018), but there is considerable uncertainty as to how this can be achieved.

To help shed light on this issue, we fielded two UK pre‐registered survey experiments designed to investigate this central question: to what extent do the origins of DMPs affect the likelihood that the public will judge mini‐publics to be legitimate and support the implementation of their recommendations? Our experimental design allowed us to examine how public support may be shaped by partisan considerations, focusing on the potential role of: (1) whether the climate assembly was promoted by politicians or the general public; (2) which political party established the assembly; and (3) whether there was clear partisan conflict surrounding the creation of the assembly.

Taken together, the findings from our two studies suggest that although partisanship does not itself appear to matter on the whole, the assembly's origins may have a modest effect on preferred bindingness, while partisan conflict over the assembly's creation may play an important role in structuring procedural evaluations. Our findings also suggest that respondent ideology is a key determinant shaping reactions to climate assemblies. This is visible via not only a direct effect (with those on the right broadly more critical of these assemblies than those on the left) but also an indirect one, with the left‐right gradient shaped by both partisan sponsorship and conflict.

Our studies thus point to several key partisanship‐related findings. Most notably, we find that although party sponsorship does not seem to matter on its own, it does appear to shape respondent reactions in the presence of partisan conflict – and the nature and size of these effects are themselves conditioned by respondent ideology. While past work suggests that cross‐partisan support for DMPs is possible on more consensual topics (Nissan, Reference Nissan, Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023), the results from our studies therefore suggest that partisanship and respondent ideology are likely to affect mass public reactions in cases where partisan conflict over the DMP does arise. Insofar as climate policy remains a contentious partisan issue, then, climate assemblies are likely to have a difficult time building consensus among the broader population. Indeed, this caveat raises considerable implications vis‐à‐vis the potential of citizens’ assemblies more broadly, given that arguments in favour of DMPs are often based on the assumption that they will help to overcome partisan disagreement and short‐termism in legislative assemblies (for a discussion of these justifications, see Machin, Reference Machin2023) – yet ‘ordinary people’ may be prone to the exact same sorts of failings as well (see also Gazmararian, Reference Gazmararian2024).

There are also several promising avenues for future research that are highlighted by the limitations of our two studies. First, it is unclear whether and to what extent the design details of the assembly that we presented to respondents may have mattered. It seems plausible, for example, that the topic of the deliberative mini‐public under investigation, climate change, influenced the findings from our analysis: if respondents assumed that Labour and Conservative politicians in the UK would disagree on climate policy, and if left‐ and right‐wing respondents alike assumed that party sponsorship would affect assembly recommendations, then this may have muted the effect of the partisan conflict treatment. If so, then research that investigates DMPs focused on less polarizing topics – or indeed, DMPs proposed by non‐partisan actors/institutions – may find different results than we do here. Similarly, our experimental design does not vary the makeup of assembly participants, which is likely to be another factor shaping public reactions to DMPs and their recommendations. It may be, for example, that assembly makeup – for example, selecting participants by lot, or oversampling certain (especially affected) segments of the population – will have a much greater impact on the capacity of DMPs to improve democratic governance and increase public support for these initiatives.

The potential influence of the nature of the parties and party system involved is also an important area for future research. On the one hand, our studies centred on the two dominant parties (Labour and Conservative) within the UK's majoritarian Westminster system. This raises questions around the role of smaller, and perhaps niche, parties in interaction with the topic of the assembly. Green parties, for instance, are a plausible sponsor for a climate assembly, especially in non‐majoritarian party systems where they are likely to hold more power. It is possible that the party sponsoring a mini‐public will be a more important influence on subsequent evaluations when the assembly concerns an issue that the party ‘owns’ given that the party is likely to have a clearer ideological profile, and be perceived as especially competent, on the issue. On the other hand, it is unclear how our results would travel to multi‐party systems. It is likely that partisan conflict would matter differently in such a context, as coalition governments may blur ideological placements and limit partisan animosity between coalition members (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024). Partisan conflict might send stronger ideological signals when it involves parties not in coalition with one another, although conflict within coalitions may be more ‘surprising’ such that it might prompt deeper cognitive elaboration with important consequences for subsequent evaluations. Future research is required to disentangle these potential effects, as well as the possibility that organizing a DMP may itself affect evaluations of (liked and disliked) parties. Given the potential effects of both DMP design details and the specific nuances of party systems, conjoint experiments – with the additional analytical leverage they provide – are likely to offer a particularly promising route forward.

Finally, our experiment focused on climate assemblies pursued by a city council and, potentially, advocated for by ‘local residents’. While many DMPs focus on local issues and interact with local governments, other deliberative institutions are tied to policymaking disputes at the national level (Landemore, Reference Landemore2020). How might this affect the potential legitimacy of DMPs and the role of sponsorship and partisan conflict? We see two possibilities. First, it is plausible that ordinary citizens may be willing to grant more power to DMPs focused on local issues since their decisions may affect only a modest number of people. In addition, participants in a local DMP are more likely to be situated within the social networks of (some) non‐participants, thereby providing a non‐electoral pathway to accountability. Second, it may be that the extent and nature of partisan conflict will differ based on whether a DMP focuses on local or national politics. The latter type of DMP may receive more press coverage, for example, insofar as news coverage is biased toward national news (e.g., Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2018). Partisan conflict involving national politics is also likely to involve statements by party leaders, which may increase the influence of party‐messages on supporters insofar as leaders represent the party prototype (Hogg & Reid, Reference Hogg and Reid2006). Future work could investigate these possibilities via careful case comparisons or by experimentally varying the size of the constituency involved or governmental domain (local vs. regional vs. national), as well as the presence of party leaders in treatment information.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from feedback provided at the Workshop on Political Communication and Public Opinion (Centre for Research in Communication and Culture/School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Loughborough University) and the Comparative Politics Research Group (Department of Political Science, Lund University). We would also like to thank Mohsin Hussain and Flori So for their comments on earlier versions of the article.

Funding Statement

This project was granted funding from Loughborough University's School of Social Sciences and Humanities via its Early Career Researcher Seed Corn Fund and via an internal grant from the Department of Political Science at Leiden University.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study received ethics approval from Loughborough University's Ethics Review Sub‐Committee (2022‐7045‐10358/2023‐13739‐13181).

Data Availability Statement

Data and replication materials will be published on the Open Science Framework (OSF) webpage for this project. https://osf.io/2z5u6/files/osfstorage?view_only=4b7d13428d1e4790b5260285c3ea00b7

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information Appendix A

Supporting Information Appendix B