Introduction

The study of European representatives is crucial, as they are linked to the institutionalization process of the European Parliament (EP) (Daniel Reference Daniel2015), namely the most important crossnational, democratic, parliamentary arena in the world. In particular, the main interest for EU studies has been to understand whether, and to what extent, a European political class has clearly emerged or not by providing some positive (Salvati Reference Salvati2016; Reference Salvati2022), but not conclusive, answers (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024).

Only recently has literature started to reflect on how in contemporary democracies the interdependence between different levels of government can affect not only the decision-making process (ie Marks Reference Marks1996; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2013) and electoral behavior (ie Schakel Reference Schakel2018; Bolgherini, Grimaldi, and Paparo Reference Bolgherini, Grimaldi and Paparo2020) but also the career paths of political elites (ie Botella, Teruel, Barberà et al. Reference Botella, Teruel, Barberà and Barrio2010; Borchert and Stolz Reference Borchert and Stolz2011; Pilet, Tronconi, Onate et al. Reference Pilet, Tronconi, Onate and Verzichelli2014; Grimaldi and Vercesi Reference Grimaldi and Vercesi2017). In particular, the adoption of a dynamic perspective is crucial to give us a deeper insight into the broader political space in which politicians can move. Unfortunately, the collection of data on institutional careers at the subnational level is often hard to achieve, and hence, such experiences have been often excluded in studies of MEPs by hindering the comprehensive understanding of their career evolution. Indeed, only recently regional offices have been taken into account when investigating MEP careers (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024), but local offices remained largely unexplored (with the partial exception of Salvati Reference Salvati2022).

However, we claim the importance of including the local experiences within the picture, often being the starting point of any political career, as they are related to the closest level of government for citizens, and they are placed in the first context in which individuals can experiment in participation and learn democratic rules (Dahl and Tufte Reference Dahl and Tufte1973). Moreover, neglecting the inclusion of local offices when investigating political careers may expose the theorization of career models to different biases. First of all, their exclusion cannot help completely overcome the methodological nationalism in political research that was first related to electoral studies (Dandoy and Schakel Reference Dandoy and Schakel2013) but may affect many other political areas, including career studies. In other words, political research tends to focus on the national or federal level of government as the first-order arena in terms of relevance and importance, notwithstanding the nation–state crisis – which emerged in the second half of the 20th century – which proves the importance of paying attention to supra- and subnational levels of government. Ironically the nation–state crisis, which led to the deepening of the EU integration process, does not correspond to a higher sensibility on subnational arenas when investigating MEP careers, as for a long time the only offices considered were the national or federal ones. Secondly, including local offices is crucial, as in many EU countries (15 Member States) a meso level in terms of Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 2 does not exist, and consequently, the only way of considering the subnational level precisely is to take into account the local arena in terms of Local Administrative Unites (LAU). Third, two phenomena are related to the increasing attraction of local offices in Europe, namely the progressive increase of the level of local autonomy (measured through Local Administrative Index (LAI)) in the last 30 years (Ladner, Keuffer, and Bastianen Reference Ladner, Keuffer and Bastianen2025) and the personalization of politics, which also affects the local arena (ie Freschi and Mete Reference Freschi and Mete2020; Wauters Reference Wauters2024) and has increased the ability of mayors to be visible and powerful across different political arenas. In fact, in Italy and Spain there are several examples of movements from the local to the European arena that show that the office of mayor is considered a sufficiently important experience to access the EP even without any other kind of political experience. Examples of these trajectories are the cases of Pedro Aparicio Sanchez, Mayor of Malaga (1979–95) who then became an MEP (1994–2004) and that of Leonardo Domenici, Mayor of Florence (1999–2009) who then became an MEP (2009–14). In addition, there are also examples of movements from the European to the local arena that show that backward jumps are seen as viable and potentially interesting options by MEPs. This is the case of Celia Villalobos who, after leaving the EP in 1995, became Mayor of Malaga (1995–2000), or the case of Luigi De Magistris, who became Mayor of Naples in 2011 after his experience in Bruxelles (2009–11).

As a consequence, our first theoretical purpose is to reflect on how the introduction of local-level experiences can help provide a comprehensive and parsimonious classification of MEPs’ career models, which can be used in comparative and longitudinal analyses. Actually, a growing body of literature has highlighted the extreme diversity and pluralism of MEPs in terms of personal characteristics, recruitment rules, circulation dynamics, and political ambitions. Such diversity has naturally led to numerous attempts to classify the career patterns of MEPs. However, such models need to be revised by also reflecting on how elite circulation may display downward movements, namely toward regional but also local offices, and how political ambition may also be focused on certain appealing local offices, such as those of mayors in medium-large municipalities. In short, we propose an adaptation of the existing models in literature.

Furthermore, our case selection helps us understand how the empowerment of subnational institutions, and in particular the local arena, was intertwined with the empowerment of the EP after the 1990s – in other words, whether and to what extent the increase in subnational autonomy corresponds to a change in the structure of opportunities that led to a higher Europeanization of MEPs and a reduction of career volatility, as argued by Daniel (Reference Daniel2015).

Our second objective is to understand whether certain political characteristics (party affiliation, crucial EP elections, and length of previous career) may have an impact on MEPs’ career models when local offices are included in the models. In doing so, we consider not only the studies on the European elite but also other literature dealing with national parliamentarians or regional politicians.

Consequently, our research questions are as follows:

-

1. What are the most widespread career models among Italian and Spanish MEPs?

-

2. What are the political factors that influence certain career models more than others?

To address these questions, we used an original dataset, which gathered all available information about Italian and Spanish MEPs from 1994 to 2019 using official sources. In short, we can rely on 508 observations in terms of individuals (and not positions). We focus on Italy and Spain, as they have similar but not identical institutional arrangements, with Spain being a quasi-federal state and Italy a regionalized state. As a consequence, we can count on two country cases in which regional and local offices can have a similar attraction – despite some nuances – in regard to the careers of politicians. Moreover, although both are southern European cases, one country is a founding member of the EU (Italy), while the other joined the EU in 1986 (Spain). As a consequence, our time frame starts from the mid-1990s to improve comparability because it is only after the reforms of the 1990s that Italy is considered a regionalized country and because it is likely that the first EP elections were characterized by idiosyncratic and specific factors in Spain. Furthermore, as the literature suggested (Whitaker Reference Whitaker2014), the empowerment of the EP occurred especially after the co-decision procedure was introduced, namely after 1994. In sum, in this paper we adopt a comparative diachronic perspective to effectively expand and potentially generalize our knowledge of career paths of MEPs.

The paper proceeds as follows: In the section ‘Literature review and hypotheses’, we first summarize the literature debate on the career models of MEPs, and we justify our choice to rely on only four career models. Secondly, we propose a set of hypotheses that take into account certain drivers that, according to international literature, have been recognized to have an impact on political career paths. In the section ‘Data, method and descriptive analysis’ we explain our dataset, the methodology of our analysis, and the first descriptive findings, whereas in the section ‘Explicative analysis’, we show our main explicative findings. Concluding remarks are in the section ‘Conclusions’.

Literature review and hypotheses

Classifications of MEP career patterns

Since the mid-1990s, an interesting branch of literature has started to investigate the career models of MEPs. In particular, the first work by Scarrow (Reference Scarrow1997) aimed at understanding whether a specific political European elite was emerging because of the increasing empowerment of the EP (eg König Reference König2008; Hix and Hoyland Reference Hix and Høyland2013; Meissner and Schoeller Reference Meissner and Schoeller2019) and the EU enlargements that assured an increasing number of parliamentarians. Scarrow (Reference Scarrow1997) originally distinguished between three main categories of career paths: the political-dead-end MEPs, who served in the EP for short time or ended their career in the EP; the stepping-stone MEPs, who seek to win or regain a term in national office after their experience in the EP; and the European careerists, who are truly committed to the EP and aim to spend their career at the EU level. Subsequently, other authors redefined some of these categories. For instance, van Geffen (Reference Van Geffen2016), when considering those who stayed in the EP for only a short time, distinguished between EU retiree and one-off MEPs. The latter are those who stay in the EP less than one term without having any political experience before or after such a position. Similarly, within the stepping-stone type certain differentiations have been introduced (eg Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir Reference Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir2007), albeit the most promising and interesting one was proposed by Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021). These authors suggested distinguishing between MEPs with national and regional ambitions, especially in regionalized and federal countries, to avoid methodological nationalism. However, most of the theoretical efforts dwelt on the differences and nuances between those MEPs who stayed longer in the EP. In particular, the distinction by Verzichelli and Edinger (Reference Verzichelli and Edinger2005) between ‘Euro-politicians’ and ‘Euro-expert’ has become the most widespread in political science literature (eg Edinger and Fiers Reference Edinger and Fiers2007; Van Geffen Reference Van Geffen2016; Salvati Reference Salvati2016; Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021). According to such a distinction, Euro-politicians are those who served in the EP for multiples terms without any previous political experience, whereas Euro-experts are those who had a previous domestic career but then focused their efforts on building or consolidating their professional career in the EP (also labelled two-track Euro MEPs by Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022). Recently, Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021) pointed out that there is another important category that has been neglected, namely that of the ambiguous multilevel career MEPs, composed of ‘individuals with experience at several levels of government in a non-ordered manner. [… In other words], MEPs with multi-level careers are defined as MEPs with (a) experience served at three levels of government (i.e., regional, national and European), and/or with (b) distinct complex sequences (e.g., national-European-national-regional); and/or (c) with time served in office that does not permit to establish a clear orientation towards one level or the other’ (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021: 6).

Despite such classifications being clearly important as a starting point for further investigations, most of them relied on empirical works that only took into account career positions held by MEPs before entering the EP (ie Verzichelli and Edinger Reference Verzichelli and Edinger2005; Bale and Taggart Reference Bale and Taggart2006; Beauvallet and Michon, Reference Beauvallet and Michon2010; Reference Beauvallet and Michon2016; Daniel Reference Daniel2015; Beauvallet-Haddad, Michon, Lepaux et al. Reference Beauvallet-Haddad, Michon, Lepaux and Monicolle2016; Salvati, Reference Salvati2016). On the contrary, in line with studies on career patterns at national or regional levels (ie Borchert Reference Borchert, Borcher and Zeiss2003; Helms Reference Helms2020; Musella Reference Musella, Andeweg, Elgie and Helms2020), we believe that it is fundamental to also look at post-careers to effectively classify political professional patterns. Furthermore, among those studies that consider jointly pre- and post-career offices of MEPs, some are single-case studies (eg Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir Reference Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir2007; Kakepaki and Karayiannis Reference Kakepaki and Karayiannis2021), and others focus on a limited time frame (ie van Geffen Reference Van Geffen2016; Biró-Nagy Reference Bíró-Nagy2016; Reference Bíró-Nagy2019), and therefore, their classifications may be somewhat biased by the lack of comparative data or a diachronic perspective. Our approach is in line with research that takes into account precedent and subsequent political experiences of MEPs, and that considers career paths with a cross-sectional and comparative perspective (ie Scarrow Reference Scarrow1997; Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024). As a consequence, we mostly refer to career models suggested by studies that put together all the abovementioned characteristics.

In particular, we rely on the macro classification proposed by Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022) that encompasses most of the patterns identified in the abovementioned studies, namely the short-termers (political dead-end), the stepping-stone MEPs (with domestic ambition), the long-termers (with European ambition), and the multilevel career MEPs.Footnote 1 In our view, such a classification is sufficiently parsimonious to allow small n and large N quantitative comparative research, but at the same time it can be unpacked into different subtypes to allow more in-depth qualitative research on the classification of career patterns in certain countries.

Furthermore, we prefer to rely on the abovementioned macro-categories as certain subtypes suggested by Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024) are not fully convincing, such as the distinction between discrete Euro career (MEPs making their entire career in the EP but for less than 1.5 terms) and one-off MEPs (only one term in the EP without political experience before or after) within the short-termers category, since the only difference pertains to the time spent in the EP, which is quite negligible. Similarly, within the macro-category multilevel career MEP the distinction between accumulating MEPs, who are classified as EU retirees, Euro two-track MEPs, and Euro-politicians with a substantial domestic accumulation, and discrete two-track MEPs, namely those with a short career at national and EU levels, is questionable. The problem with such a classification is that it focuses more on the time spent in each office rather than on the ‘jumps’ that MEPs may do back and forth among different levels of government. Moreover, the first subcategory (accumulating MEPs) risks not being mutually exclusive in comparison with others, such as EU retiree (which is a subcategory of short-termers) and Euro two-track MEPs and Euro-politicians (which are subcategories of long-termers). As a consequence, we believe that the previous, more general classification of multilevel career MEPs (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021) is more effective.Footnote 2

Finally, we believe that Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021) were completely right in underlining that many studies suffer from methodological nationalism, as they completely neglect to consider regional offices when dealing with MEP career paths – so much so that, in their first classification of MEP career paths, Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021) distinguish between stepping-stone MEPs with national or regional goals. However, they found that both subcategories were residual, and they then preferred to recombine them into one (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022).

Furthermore, we also agree with the idea that it is necessary to clearly distinguish between municipal and regional (or similar meso-level) offices when dealing with the subnational career of MEPs, as many studies put all these experiences together in a chaotic way. However, in their empirical research Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022; Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024) failed to consider local offices when dealing with MEP careers. This aspect is problematic owing to three points of view. First, they do not consider that municipal offices are the first political training ground for most (regional, national, and European) politicians. Secondly, by not taking into account municipal offices, the career paths of any politician (and MEP) cannot entirely be traced; in other words, the attempt to have a truly comprehensive view of MEP careers fails. Thirdly, omitting the local level means not completely escaping from the bias of methodological nationalism imputed to other research.

We are fully aware that it is very complex to gather data on municipal careers in more country cases. However, we believe that a good strategy is looking at the executive offices at the subnational level. This choice can be justified for two reasons: Theoretically, the personalization and presidentialization of politics also affected subnational governments (ie Musella Reference Musella2009; Astudillo and Martínez-Cantó Reference Astudillo and Martínez-Cantó2019; Karsten, Sweeting, Kjær et al. Reference Karsten, Sweeting, Kjær, Kukovič, Callanan and Loughlin2021) and not only the national ones, especially in regionalized and federal states. This means that the regional or local executives are likely to empower and reinforce, when compared with assemblies, even when the parliamentary type of government is maintained, as happened in Spain (ie Teruel Reference Teruel2012; Fittipaldi Reference Fittipaldi2021). If this holds true, it is likely that subnational executive offices such as mayor or regional minister or regional president can be appealing enough for MEPs to consider jumping backward to the domestic arena pursuing a stepping-stone model (with subnational ambition) or a multilevel career. Furthermore, from an empirical point of view, it is clearly easier to map executive positions in comparison with legislative ones, the former being more publicized. We decided to follow such a strategy in our work.

In conclusion, our classification of MEPs’ careers is that proposed in Figure 1, which comprises the four macro-categories taken into account in this paper (short-termers, stepping-stone MEPs, long-termers, and multilevel surfers) and six possible subcategories (EU retirees, one-off MEPs, stepping-stone MEPs with national ambition, stepping-stone MEPs with subnational ambition, two-track Euro MEPs, and Euro-politicians).

Figure 1. The four main categories of MEPs career paths as identified in this study. Source: Adapted from Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2021.

Explaining different career patterns

Despite the interest in the conceptualization of different career paths, there is no clear-cut evidence of specific drivers that can explain what, and to what extent, certain factors correlate with one or another career model. Nevertheless, we consider it important to test whether some of the main findings of previous work on MEPs still hold true after our adaptation and reframing of their career models – in other words, whether the identified drivers have the same impact on certain career models when the structure of opportunities changes as a result of the inclusion of new local offices.

In particular, EU studies have identified three important political factors that affect MEPs’ careers: The first is the idea that the empowerment of the EP has created a more stable and long-lasting European political class (Edinger and Fiers Reference Edinger and Fiers2007; Daniel Reference Daniel2015; Beauvallet-Haddad, Michon, Lepaux et al. Reference Beauvallet-Haddad, Michon, Lepaux and Monicolle2016; Biró-Nagy Reference Bíró-Nagy2019), but at the same time that certain ‘critical junctures’ may affect MEPs’ careers; the second idea is that the Europeanization of the political class is not uniform and homogeneous, but depends on the party’s attitude toward European integration (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2018; Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024). The third point is related to the idea that, in federal countries or countries with a high degree of regional autonomy, MEPs are more likely to keep their office than to pursue other types of careers (Daniel Reference Daniel2015).

As far as the first point is concerned, most of the efforts have been devoted to explaining how the change of institutional rules have an impact on careers. For instance, Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch (Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2022) proved that, as the power of the EP increased, the number of long-termers increased as well, while that of the stepping-stone MEPs (with national ambition) declined. Similarly, the long-termers model increased from the VI legislature, when the rule forbidding holding simultaneous positions at different levels of government (in the EU and national arena) entered into force in 2004, whereas the multilevel career MEPs declined. However, the same authors reminded us that such findings should not be taken for granted, as the 2019 European elections presented the greatest turnover of MEPs since 1984, as well as a peak of parliamentary fragmentation, and since 2014, the eurosceptic parties obtained an impressive share of votes and seats. The Italian case is particularly emblematic, with eurosceptic parties such as the Lega per Salvini Premier gaining 34% of the vote in 2019 (+28% compared with the previous elections), but also in Spain in 2014, with the affirmation of Podemos (around 8% of the vote) and the Plural Left (10% of the vote, +6% compared with 2009).

Against this background, the literature has often emphasized the impact of ‘critical junctures’ on the career patterns and profiles of MEPs. In particular, the critical juncture of the 2004 EP elections led to a new generation of MEPs with a more technocratic profile, a better gender balance, and, usually, more commitment to the EP (Verzichelli and Edinger Reference Verzichelli and Edinger2005). Similarly, other studies claim that the 2014 EP elections led to the emergence of a pro-European/anti-European cleavage (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2017), which also had an impact on MEP profiles and careers (Kakepaki and Karayiannis Reference Kakepaki and Karayiannis2021) in terms of gender and in terms of previous domestic career.

The 2014 elections represented a significant discontinuity, particularly in the context of southern Europe. Part of the literature (Kakepaki and Karayiannis Reference Kakepaki and Karayiannis2021) has highlighted that the destructuring of national party systems affects national, but also European, careers. The latter became shorter, and there was a greater presence of MEPs without extensive national experience. As a consequence, it is likely that another generation of MEPs less committed to the EU increased after the critical 2014 EP elections. Our first hypothesis therefore is as follows:

Hypothesis (H1): We expect that the long-termer MEPs are negatively affected by the EP 2014 elections, more specifically that they are likely to decrease in comparison with previous elections. On the contrary, short-termers are positively affected by the EP 2014 elections.

Turning to the second point, on the one hand, recent studies have highlighted that, despite the widespread belief that the EP serves either as a ‘retirement home’ for national politicians at the end of their careers or as a ‘training arena’ for younger ones (Hix and Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2011), there has been a gradual Europeanization of the political class over the years (Marzi and Verzichelli, Reference Marzi and Verzichelli2025; Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024). On the other hand, this Europeanization has not occurred uniformly; rather, it has been more pronounced among the more ‘mainstream’ parliamentary groups, particularly the socialists and the European People’s party (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024). This aspect may be particularly relevant in relation to the populist tide that has swept through all EU countries since the mid-2010s, as such populist parties are often distinguished according to the pro-European/anti-European cleavage. In particular, since the global economic crisis, Italy and Spain witnessed the success of the so-called neopopulist parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Font, Graziano, and Tsakatika Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2021) such as the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) and Podemos (Franzosi, Marone, and Salvati Reference Franzosi, Marone and Salvati2015; Damiani and Viviani Reference Damiani and Viviani2019), and the right-wing parties such as the Lega, Fratelli d’Italia (FDI) (Vampa Reference Vampa2023), and Vox, which challenged mainstream parties on several issues but especially on EU membership and engagement in the EU. It can be assumed that these parties, being less committed to the EU compared with other mainstream parties, tend to favor national political careers over European ones. Therefore, in line with their party’s sovereigntist agenda, they can use every opportunity to gain a national position and thus demonstrate their commitment to national politics. We can hypothesize that MEPs coming from eurosceptic parties (old and new) are actually less interested in the growth of a European political class, and therefore, our second hypothesis is as follows:

H2 MEPs from eurosceptic parties are less likely to develop a career as long-termers.

To the third point, previous research has suggested that federal countries are more likely to develop specific political personnel for different territorial institutions. For example, research on political careers in Germany has confirmed that there is a clear division between politicians who pursue careers at the subnational level (especially at state level) and those who are committed to federal politics. As a result, there are few opportunities to move from the subnational to the federal arena and vice versa (Borchert and Stolz Reference Borchert and Stolz2011). Similarly, Daniel (Reference Daniel2015) points out that federal or regional countries are more likely to develop a more distinct European political class, such that MEPs are more stable and willing to stay in the EP compared with MEPs from centralized countries. As a consequence, we can expect that:

H3 The long-term model is one of the most recurrent career types in Italy and Spain.

Furthermore, in an explorative attempt to understand whether certain other political features may have an impact on MEPs’ careers – as the latter proved to have for national or regional politicians – we produce another hypothesis related to previous careers.

Based on EU studies, Salvati (Reference Salvati2022) shows that the weight of subnational professionals among newcomers to the EP increased significantly during the 2009–2019 period. Moreover, the same research found a positive correlation between newcomers with a previous subnational career and the high degree of regional autonomy of their country of origin. However, this research also shows some important outliers, such as the UK, Denmark, and Finland. We argue that the direct move from the subnational arena to the EP can occur even in countries with low regional autonomy but high local autonomy (in terms of LAI), as in the cases of the countries mentioned above as outliers. This reinforces our perspective on the need to include local experiences to fully grasp MEP career types.

Furthermore, previous national and subnational careers have been assessed as crucial assets for improving MEPs’ expertise in terms of reducing the time spent on dealing with reports (Salvati and Vercesi Reference Salvati, Vercesi and Scherpereel2021). This finding does not clearly imply that such a previous career would necessarily increase stability and reduce volatility in the EP, but it does highlight how a considerable previous domestic career can open up several more possible trajectories for MEPs compared with those without previous experience.

Building on subnational career studies (Boldrini and Grimaldi Reference Boldrini and Grimaldi2023), evidence shows that a previous career is fundamental to determine the length of the tenure in a regional executive office. Furthermore, regional ministers with longer previous careers at the national level are more likely to move to national posts, whereas those with longer previous careers at the local level are more likely to move backward to local positions. If this also holds true for MEPs, we can assume that the length of their previous national, regional, or local career is fundamental to frame the multilevel career model. In other words, the ability to jump back and forth to different levels of government increases when politicians have proven enjoyment of consistent previous domestic political experience. In particular, parties are more likely to include on their lists outgoing MEPs who can offer some specific previous experience in relation to the electoral arena (national, regional, or local) in which they are standing. As a consequence, we can assume that:

H4 MEPs with longer previous careers (at municipal, regional, and national levels) are more likely to develop a multilevel career model.

Data, method, and descriptive analysis

As previously mentioned, through a comparative analysis of the Spanish and Italian cases, this paper aims to investigate how political factors influence the career paths of MEPs by introducing the important innovation of career paths at the subnational and national levels. The two cases were selected on the basis of a comparative approach involving similar countries, with the aim of minimizing noise in the exploration of MEPs’ career trajectories. Spain and Italy share several strong similarities: Both are southern European countries; both were significantly affected by the economic (Hopkin Reference Hopkin, Matthijs and Blyth2015) and political crises (Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019); both witnessed the rise of populist, eurosceptic parties; and both – in Italy, following the reforms of the 1990s – feature a regionalized territorial power structure (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014). In this system, local positions either can serve as an important stepping stone toward a national political career or, conversely, can hold strong appeal as a career destination after a term in Brussels. Comparing these two similar yet institutionally distinct cases allows us to identify patterns that may otherwise be obscured in single-case studies, and findings from this comparative analysis may be relevant to other southern or western European countries with similar electoral systems, party structures, and multilevel governance dynamics. Given this premise, a quantitative analysis was chosen, including bivariate and multivariate analyses, applied to an original dataset on the careers of Italian and Spanish MEPs in terms of individuals rather than positions (thus, reconstructing the career of the individual from the last position held to the first) from 1994.

To this end, a dataset was constructed with all the positions held by individuals throughout their political careers. The data were extracted from the official website of the EP; the official websites of the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate of the Republic, and the Registry of Local and Regional Administrators for Italian MEPs; from the official websites of the Congress of Deputies, the Senate, and various autonomous communities; and from the CVs and profiles of the individual MEPs for the Spanish case.

The decision to focus only on MEPs after 1994 was dictated by the need for comparability between the two cases and the reliability of the data collected. Despite strong similarities, the Spanish and Italian political and institutional systems historically presented some significant differences. As is well known, the Italian political system before the fall of the Berlin Wall was characterized by bilateral oppositions and antisystem parties, which meant competition was not polarized and alternation was prevented. In contrast, since its foundation after the fall of Francoism, the Spanish system has been characterized by a polarized dynamic with strong alternation between the two main right and left coalitions. Moreover, the Italian institutional system until the 1990s was characterized by strong centralization and little autonomy for subnational levels of government (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014). Only starting with the reforms of the 1990s (in particular, Law 81/1993 on the direct election of mayors and Law 43/1995, known as the ‘Tatarella’ law after its proposer, on the direct election of the regional president) has the political power of subnational entities strengthened, enhancing the attractiveness of these types of positions in the perspective of building a political career (Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli2010). Consequently, including MEPs elected earlier would have introduced a significant distortion, weakening the intention to make a comparison between the two most similar cases. Furthermore, collecting data on subnational careers from earlier periods risked limiting the robustness of the analysis, as such data are not always reliable or even available.

The choice of the time frame’s endpoint proved to be more complex. In fact, to explore the careers of MEPs, it was necessary to identify a temporal threshold within which the possibility of holding additional positions can be considered. For this purpose, we chose to consider career movements within the 5 years following the end of the MEPs’ last term in office. While this choice may seem arbitrary, it was driven by theoretical and empirical reasons. Indeed, 4 years is the maximum duration of a legislature at local, regional, and national levels in Spain, while 5 years is the maximum duration of a legislature at local, regional, and national levels in Italy. In addition, a European legislature lasts a maximum of 5 years in both countries. This length of time ensures that at least one election at each level was covered, allowing for the inclusion of any positions obtained following these elections. In addition, from an empirical perspective, nearly all MEPs who secure a new position do so within precisely 5 years after the end of their term. Footnote 3 For this reason, it was decided to include in the analysis all MEPs who had completed their term in office in the EP at least 5 years before the time of this analysis (June 2024).

As mentioned, we rely on bivariate and multivariate analyses. The former was used to descriptively illustrate differences in the profiles of MEPs in terms of career type and in relation to country of origin, career and party affiliation, and duration of previous career. Conversely, a multinomial logistic regression was used to highlight which factors are associated with the development of a particular career model.

The independent variables included in the analysis concern political characteristics, such as the party’s position on the EU (whether eurosceptic or not), the critical 2014 EP election, and the previous (national, regional, and local) career.

Belonging to a eurosceptic party was operationalized as a dichotomous variable with a value of 1 if the MEP belonged to a party identified as eurosceptic according to the PopuList dataset (Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou et al. Reference Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou, Froio, Van Kessel, De Lange and Taggart2024). For example, mainstream parties such as the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), the Spanish Partido Popular (PP), or the Partito Democratico Italiano (PD) are considered noneurosceptic (variable value 0), whereas parties such as Vox or FDI are considered eurosceptic (variable value 1).

Similarly, the critical juncture of the 2014 EP election was operationalized as a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the MEP obtained their last term in office starting from 2014 or 0 otherwise.

Previous career was operationalized as a continuous variable, as the number of days in office prior to the first term in EP office as mayor, regional minister, regional president, national MEP, and national minister. In the multivariate analysis, for greater comparability of results, these variables were normalized.

Finally, a variable related to the country of origin was introduced, operationalized as a dichotomous variable (value 1 if elected in Spain, 0 if elected in Italy). This variable was included to account for all cross-country variability that may influence career trajectories. Specifically, it captures differences related to the political system and the electoral rules in each country. In Spain, MEPs are elected through a closed-list proportional representation system, where parties determine the ranking of candidates. In contrast, the Italian system follows an open-list proportional representation model, allowing voters to express preferences for specific candidates. These institutional differences can shape career opportunities and mobility patterns, making it essential to control for them in the analysis.

Moreover, we also considered two sociodemographic characteristics as control variables: gender and age. Gender was operationalized as a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the MEP was female and 0 otherwise. Since a linear effect of age is not necessarily expected, it was operationalized as an ordinal variable with six different categories related to age, expressed in years at the time of the first election to the EP (under 40, 40–49, 50–59, and 60 years or older).

Our dependent variable consisted of the four different career models, discussed in the section ‘Introduction’ (Figure 1). As a consequence, we operationalized the shorter-termers as all those politicians who stayed in their last EP office for less than 1.5 terms after a domestic career at the national level, the subnational level, or both (EU retiree). Those politicians who only had one short run in office in the EP (less than 1.5 terms) without any previous or subsequent domestic offices (one-off MEPs) can also be counted in this category. The stepping-stone MEPs were those who used their EP post to pursue a domestic career at the national or subnational level. Accordingly, they obtained their first political office in the EP and then developed a longer national (stepping-stone MEPs with national ambition) or subnational career (stepping-stone MEPs with subnational ambition). Alternatively, their experience in the EP was an intermediate step between a previous and a subsequent domestic experience (if national, as with stepping-stone MEPs with national ambition, or, if subnational, as with stepping-stone MEPs with subnational ambition) and their tenure in the EP was in any case shorter than 1.5 terms in office. The long-termer MEPs are those who only had European experience for more than 1.5 terms in office (Euro-politicians) and all those who had a previous domestic (national, subnational, or both) experience but who then returned to the EP to remain there for longer than 1.5 terms in office. Furthermore, those who had an intermediate stage at the domestic level between two appointments to the EP (and the second for more than 1.5 terms in office; two-track Euro MEPs) were also included among the long-termers. Finally, we operationalized the multilevel career MEPs as all those politicians who had experience in all three different levels of government (European, national, and subnational) but no clear commitment to the EP, as this experience was never the last stage of their career path (see Appendix 1 for the connection between all career paths and the career models analyzed).

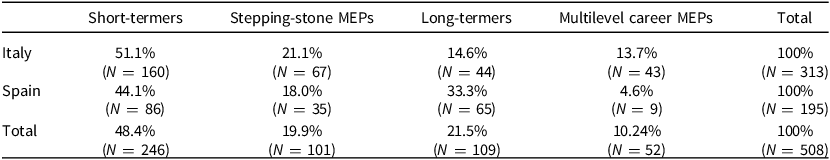

As presented in Table 1, our dataset comprised 313 Italian MEPs and 195 Spanish MEPs. Short-termers were the most widespread career model in Italy (51.1%) and in Spain (44.1%). However, the second most frequent model was different in the two countries. In Spain 33.3% of MEPs were long-termers, whereas in Italy only 14.1% were long-termers, as the second most frequent career model was that of the stepping-stone MEPs (21.1%). More interesting were the data regarding multilevel career MEPs; in fact, such a model was definitely more common in Italy than in Spain (13.8% and 4.6%, respectively).

Table 1. Distribution of MEPs per country according to the four career models identified

Note: Pearson chi-squared (3) = 32.3898, Pr = 0.000.

All in all, the most frequent career model of MEPs for both countries was that of short-termers, meaning that the EP is still considered a second-order arena (Reif and Schmitt Reference Reif and Schmitt1980), where national politicians can spend the last days of their career, rather than a first-order arena, where important political decisions are taken. However, while in Spain it seemed that a European political class has grown from 1994 to 2019, with the long-term model being the second most frequent, in Italy there was far less commitment to the EU, as the EP is seen as an intermediate step, functional to pursue a national – and sometimes even a subnational – career path. This result was strongly confirmed by the fact that in Italy the share of MEPs who displayed a multilevel career model was close to that of the long-termers. Thus, once again, the Italian political MEPs seemed less committed to the EU institutions than Spanish ones since for them it was essentially the same to stay in the EP or jump from one level of government to another. Such a result partly contradicts our third hypothesis (H3) since in Italy, despite the increasing regional autonomy, the volatility of MEPs in terms of moving from the EP to other arenas was still high. In our view, this could be because of the fact that Italy has experienced a series of reforms toward decentralization in the same years that the EP has increased its power (with the co-decision procedure), unlike Spain, which has experienced a quasi-federal architecture since its transition to democracy. In other words, in Italy, the subnational and supranational arenas have become more attractive at the same time, leading to increased rather than reduced volatility.

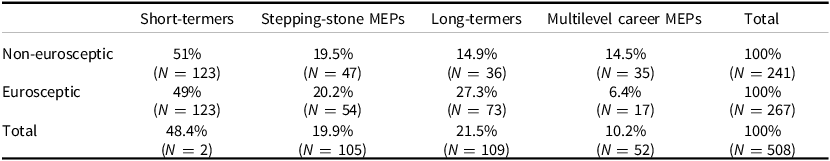

As for the distribution between the different party types (Table 2), a relatively even distribution between eurosceptic and noneurosceptic parties can be observed. The main differences concerned the presence of long-termers, which was higher among eurosceptic parties (27%) than among noneurosceptic ones (14.9%). Conversely, there was a higher presence of multilevel career MEPs among noneurosceptic parties (14.5% and 23%), while on the contrary, there was no particular difference for short-termers and stepping-stone MEPs.

Table 2. Distribution of MEPs according to the four career models per eurosceptism of their party

Note: Pearson chi-squared (3) = 17.9920, Pr = 0.000.

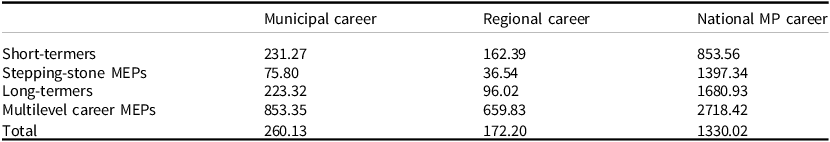

Table 3 shows that a previous national career was the longest for all career models of MEPs, whereas a local career was the second longest, even when a meso level of government exists, as in Spain and Italy. This finding reinforces our argument related to the importance of considering local offices beyond regional ones when investigating MEP career trajectories. All that said, it seems convincing that the time spent at the national level is the longest for short-termers, as for many of them the EP was a sort of retirement home, and thus the subtype EU retiree was the majority for this category in our sample. Similarly, we know that previous domestic experience is crucial for multilevel surfers who need the combination of the highest and different offices to fit this specific model of career. However, data also showed that a domestic career at the national level was also predominant for long-termers. This means that, within this category, the two-track Euro MEPs were more prevalent in comparison with those who only had European experience (Euro-politicians).

Table 3. Average time in office (in days) per type of previous career and career model

Explicative analysis

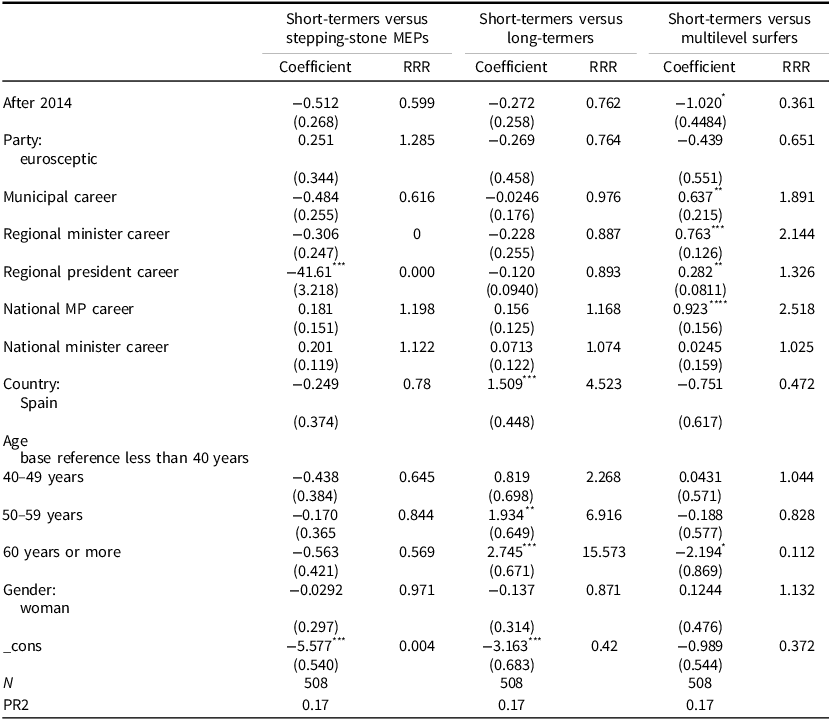

As mentioned in the previous section, we used a multinomial logistic regression analysis to test our hypotheses. The results are shown in Table 4. The first column displays the coefficients and the standard errors, whereas the second one presents the relative risk ratio (RRR) associated with each independent variable. An RRR greater than 1 indicates a greater probability of developing the associated event (in this case, the career model), while conversely, an RRR of less than 1 indicated a lower probability. In addition, to make it easier to understand the effect on career type, we displayed the marginal effects of each statistically significant variable.

Table 4. Results of the multinomial logistic regression

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

As initial results, the analysis underlines that a previous national career (as an MP and/or minister) or a subnational one (as a mayor, or regional minister or president) is crucial for multilevel career MEPs. In particular, Table 4 shows that such previous national or subnational careers were longer for multilevel surfers than for short-termers. This finding is important, as it demonstrates that prior domestic political experience plays a more significant role for multilevel career MEPs than for short-termers, including those who enter the EP as EU ‘retirees’ and who may, in some cases, have had extensive national experience. In fact, municipal, regional, and even national parliamentary careers were positively associated with the likelihood of pursuing a multilevel trajectory, thus confirming H4.

The only exception was the national ministerial career, which – although it showed a positive coefficient – was not statistically significant. However, this result may be influenced by the relatively small number of MEPs with substantial ministerial backgrounds, most of whom had relatively short careers at the European level.

In addition, an interesting pattern emerged when looking at the predicted probabilities associated with municipal experience (Figure 2). The confidence intervals for different career trajectories overlapped slightly, suggesting a less clear effect than the multinomial logistic regression initially suggested. In contrast, as shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5 – which illustrate the predicted probabilities for experience as a regional minister, regional president, and national MP, respectively – this overlap was either absent or much more limited. In these cases, the relationships between the explanatory variable and the career trajectories were more clearly defined.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on a municipal career.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on a regional minister career.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on a regional president career.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on a national MP.

This weaker pattern in the case of municipal experience may be because of the specific nature of this variable: Relatively few MEPs had a long-standing municipal career, which increased the uncertainty of the estimates, especially at higher values. Nevertheless, the direction and magnitude of the effect remained suggestive, and the trend was consistent with theoretical expectations. As a robustness check to assess whether the inclusion of municipal-level experience had a substantive impact on our classification of MEPs’ career trajectories, we re-estimated the multinomial regression model excluding these municipal positions.Footnote 4 The comparative results suggest that including municipal experience modestly improved model fit (McFadden R 2 increased from 0.149 to 0.170; Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) decreased) and enhanced the explanatory power of time-sensitive variables such as ‘after 2014’. This supports our argument that, while often overlooked, municipal careers contribute meaningfully to the understanding of political trajectories at the European level. However, further research is needed to better understand the role of local-level experience in shaping long-term parliamentary careers.

Our second hypothesis (H2) has not been confirmed. In particular, we did not find any evidence that politicians coming from pro-European parties at the national level were more likely to develop an EU career model as long-termers rather than as short-termers. These findings, despite being counterintuitive, are in line with recent research (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2018), which shows that eurosceptic parties are more likely to reconfirm incumbents at the EP in comparison with parties with neutral or positive attitudes toward EU integration.

Moreover, we did not find any significant statistical effect of the 2014 critical juncture on the likelihood of developing a short-termer career rather than a long-termer. However, a negative effect could be observed regarding the probability of developing a multilevel surfer career.Footnote 5 To better understand the effect of this variable, the marginal plot can be examined again (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on the 2014 critical juncture.

As can be seen from Figure 6, the probability of a short-term career significantly increased after 2014, highlighting a greater prevalence of this type of career. However, contrary to initial expectations, long-termers (as well as stepping-stone MEPs) remained relatively stable. In contrast, multilevel surfers showed a decrease in probability.

The post-2014 context thus seems to have influenced political careers by reducing the likelihood of MEPs taking advantage of the opportunities offered by multilevel governance. One possible explanation for this effect is that the sudden electoral success of certain political formations with weak territorial roots – most notably M5S and Podemos – facilitated the entry of individuals with limited national experience into the EP. These individuals, in turn, struggled to maintain their position in Brussels or leverage the opportunity to secure a role at the national or subnational levels because of the electoral fluctuations affecting their parties. Thus, our H1 was only partially confirmed, and further investigations are needed to explore this effect in more detail.

Finally, the analysis shows that, in Spain, MEPs are more likely to become long-termers than short-termers, and less likely to follow a multilevel trajectory compared with a short one (Figure 7). The predicted probability of being a long-termer was significantly higher in Spain than in Italy (Δ = +0.245, p < 0.001). This difference is statistically robust and suggests a clear national divergence in long-term European parliamentary careers.

Figure 7. Predicted probabilities of an MEP career based on the MEP’s country.

These findings are noteworthy for two main reasons. First, the multinomial analysis corroborates the descriptive trends discussed in the section ‘Data, method and descriptive analysis’, namely that Spanish MEPs appear more committed to the European level than their Italian counterparts. Second, it highlights that, for Spanish MEPs, pursuing a multilevel career seems markedly less attractive than a long-term European one – despite Spain’s quasi-federal institutional configuration, which would theoretically facilitate vertical mobility between levels of government.

Conclusions

Our study, which follows a comparative and cross-sectional perspective, succeeds in demonstrating that a classification of MEPs’ career models into four types is sufficiently comprehensive and parsimonious, even when taking into account offices before and after their EP positions and introducing the subnational level, namely regional and municipal posts. In sum, we have identified, in line with established literature, that with regard to career models, MEPs can be distinguished into short-termers, stepping-stone MEPs, long-termers, and multilevel surfers.

Furthermore, our main findings demonstrated that the 2014 EP election influenced certain career models. In particular, we found that, after the populist tide and the subsequent strengthening of the pro-European/anti-European cleavage, the probability of MEPs engaging in the EP decreased, as they were more likely to develop a short-term career model than a long-term one. In other words, after 2014, a political class less committed to the EU has emerged, one that prefers to remain in the EP for a short period and then retire from politics or pursue other more appealing domestic positions. This finding is reinforced by the fact that there was no clear difference between eurosceptic or mainstream parties in this regard. Thus, it seems that the success of the populist parties in the EP after 2014 also contributes to the devaluation of the prestige of European institutions across party lines.

Another interesting result was related to the previous domestic career of MEPs; our study proves that such a career is an advantage for the development of the multilevel career model in comparison with the short-termer one. In particular, previous national experience and a regional executive career are the best predictors of a multilevel career. This result is important because it shows that the politicians who can actually take advantage of the multilevel institutional arrangements in terms of accumulating positions are those with a consistent previous domestic career. Namely, they are political professionals who had a clear commitment to domestic institutions before moving to the EP and then jump back and forth among different territorial levels. As noted, the municipal career path showed the least clear impact. However, this may be linked to the lower prevalence of long-term positions of this kind among MEPs. It can be speculated that this is because of the relatively lower relevance of municipal offices in facilitating election to the EP compared with national-level positions. Nonetheless, this remains an aspect that warrants further investigation in future research.

Putting these findings into a broader perspective, we can make two points. First, in line with literature, we can say that the institutionalization of a European political class is not a fully achieved goal. This is not only because of the persistent differentiation between western and eastern Member States (Dodeigne, Randour, and Kopsch Reference Dodeigne, Randour and Kopsch2024) but also because there are clear differences within western European countries with similar institutional characteristics. Furthermore, the EP is still seen as a ‘retirement home’ or a ‘training arena’ (Hix and Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2011) for most politicians, including those belonging to mainstream pro-EU parties. Consequently, our research supports the idea that a European political class that is less and less committed to the values and project of the EU, and that uses the EP in a utilitarian way, will end up disempowering the most important representative European institution.

However, we view the glass as half full because our research also shows that, in federal or regionalized countries, we have identified a significant Europeanized political class (as in Spain) that seems to be stable, or the emergence of a new type of career model, the so-called multilevel surfers (as in Italy). Therefore, our second point is that, in the near future, there will probably be room for different types of political professionals, those who specialize in national or European politics, to coexist with those who disregard such specialization and are more inclined toward a broader overview, namely people who can gain a different and integrated perspective by having been active in different institutional arenas for a reasonable period of time. Such experience in complex and turbulent times can have a positive effect at all levels of government, and not only at the European level.

Future research should test the robustness of our results in two directions: first, by including not only subnational executive offices but also legislative ones to get a clearer and more complete picture of MEPs’ career paths and, second, by expanding the sample of regional or federal countries to better understand the impact of prior political experience on the career models studied.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1682098325100039.

Data availability statement

The raw data required to reproduce the above findings cannot be shared at this time because of time limitations. An open dataset will be available soon.

Competing interests

None.

Selena Grimaldi is Associate Professor at the University of Macerata, where she teaches Political Science and Communication and Political Language. Her research interests are related to studies on leadership and presidential politics, regional and local elections, political class and careers, and the communication and political language of political leaders. Her work has been published in national and international journals such as the Political Studies Review, Local Government Studies, and Regional & Federal Studies. Her most recent books are Local Electoral Participation in Europe (with Bolgherini S. and Paparo A., Palgrave MacMillan, 2024) and The Informal Power of Western European Presidents (Palgrave MacMillan, 2023).

Matteo Boldrini is a postdoctoral researcher at University of Siena in Rome. He received his PhD in Social and Political Change from the University of Florence in co-tutorship with the University Paris 1 – Pantheon Sorbonne in Paris. His main research interests are related to political class and political careers, at the national and local levels. He has published in Regional & Federal Studies and Contemporary Italian Politics, among other journals.