1 Introduction: The Presence of the Past

As an historian, my contribution in this Element will be centered on the historiography of paleontology, or the different ways in which paleontologists and historians have been engaging with paleontology’s past. The main thesis is as follows: How the history of paleontology is being told and shared has a role to play in making paleontology more accessibleFootnote 1 and equitableFootnote 2. How any community, including the paleontological community, relates to its past and summons it in the present helps define some of its future. This Element introduces a new and growing historiography of paleontology as a valuable resource for anyone (students, educators, researchers, curators, volunteers, community leaders, etc.) seeking to make the study of the Earth’s deep past benefits to and from a diversity of people worthy of the diversity of life it brights to light.

1.1 Appreciating the Presence of the Past

Paleontologists are in a privileged position to appreciate the presence of the past. They are, as Norman MacLeod once put it, “no strangers to an obsession with the past” (MacLeod Reference MacLeod2006). The nature of their work brings to light the simple fact that the past is never truly gone. Past life lingers in the present, leaving behind traces of things that happened and remains of beings that were alive long ago. Paleontologists deal with a large spectrum of traces and remains, from faint ichnofossilsFootnote 3 to incredible Lagerstätte.Footnote 4 Advances in technology and research methods have been providing ways to retrieve clues believed to be forever erased and to get around the gaps in the fossil record. From a paleontological perspective, the past is also present within the forms and structures of today’s organisms and environments. This constitutive place of the past within the present is what provides grounds for the analogies paleontologists draw between the extinct and the existent and for the relevance of paleontological knowledge to understand our world (Halliday Reference Halliday2022, p. xv–xx).

Since the early beginnings of the field, paleontologists have expressed their deep appreciation for the presence of the Earth’s past. They have shared the unique and fulfilling experience of being able to “see” the past in the present (Turner Reference Turner2019). Recounting his climbing of a mountain in the Andes, Charles Darwin, then a young geologist embarked on the Beagle expedition, described how the landscape surrounding him was rendered even more sublime by finding fossil shells on the most elevated ridge:

The atmosphere resplendently clear; the sky an intense blue; the profound valley; the wild broken forms; the heaps of ruins, piled up during the lapse of ages; the bright-coloured rocks, contrasted with the quiet mountains of snow; all these together produced a scene I never could have figured to my imagination. Neither plant nor bird, excepting a few condors wheeling around the higher pinnacles, distracted the attention from the inanimate mass. I felt glad I was alone: it was like watching a thunderstorm, or hearing a chorus of the Messiah in full orchestra.

About a decade later, Gideon Mantell concluded his geological guide to the Isle of Wight by superimposing the deep past onto the present in an exercise of stereoscopic description:

At the present time, the deposits containing the remains of the mammoth and other extinct mammalia, are the sites of towns and villages, and support busy communities of the human race; the Huntsman courses, and the Shepherd tends his flocks on the elevated masses of the bottom of the ancient chalk ocean – the Farmer reaps his harvests upon the cultivated soil of the delta of Iguanodon – and the Architect obtains from beneath the petrified forest, the materials with which to construct his temples and his palaces.

Experiencing the presence of the past has been and remains a leitmotiv in the popular writings of many paleontologists. In Dinosaur Heresies, Robert T. Bakker shared with his readers some of his experience working in the field in the early morning. In the mind’s eye of the paleontologist, the fossils still trapped in the rock seem to find life again:

From where I sit on the quarry’s rim I can see the dinosaur’s great trochanters, the attachment site of the immense hip muscles, and the bone surface pitted and rough where tendons and ligaments were anchored to the femur. A hundred thousand millennia ago, those tendons and muscles were full of dinosaur blood coursing through capillary beds, bringing oxygen to the cells that powered the stride of this ten-ton giant. Muscles pulsed in cycles of contraction and release, and the hind limb, fully twelve feet long from hip to toenails, swung through its stroke covering six feet with every pace.

Sharing the details of his expedition in Mongolia at the beginning of the 1990s, Philippe Taquet described in similar terms his encounter with fossil remains:

For us today, in the twilight of the end of a beautiful day, in the hollow of this canyon in the Nemegt Valley, in front of the parched remains of this superb tarbosaur with its skin still preserved, truth became stranger than fiction, and the shadow of the past was truly present.

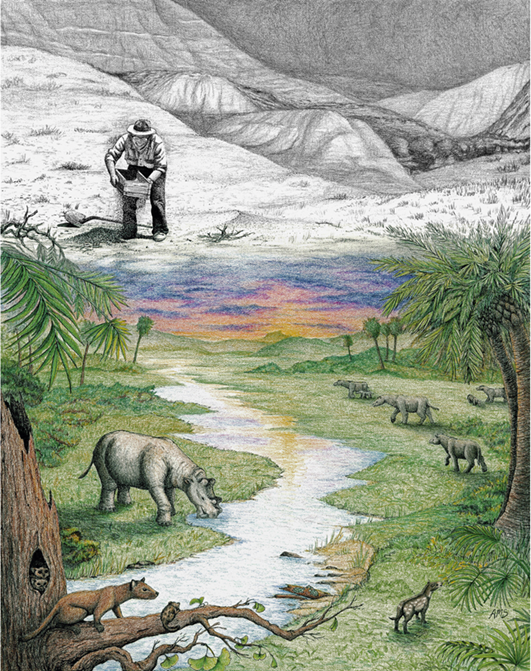

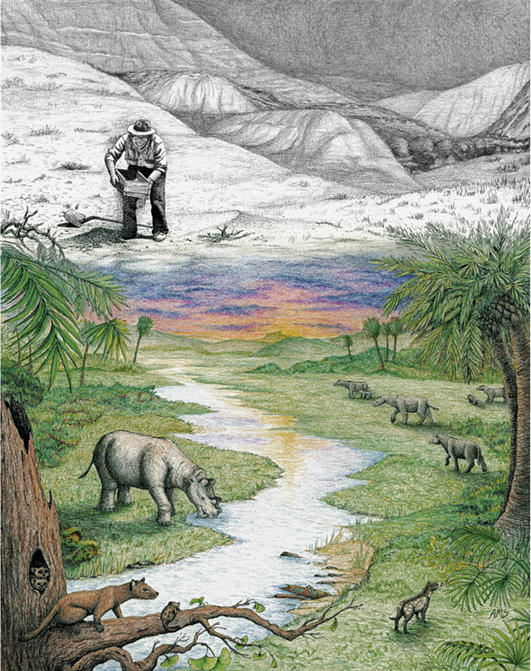

One recent and compelling expression of this appreciation for the presence of the past is a picture made in 2016 by Chicago Field Museum collection assistant and paleoartist Adrienne Stroup, Bill Turnbull’s Eocene (Figure 1). The top-half of the picture, inspired by black-and-white photographs from the 1950s (Stroup Reference Stroup2017), shows paleontologist William Turnbull working in southern Wyoming. The landscape is barren and, apart from the lone protagonist, graced with very few signs of life. In contrast, the colorful bottom-half of the picture shows a river running through a luxuriant landscape inhabited by animals from the Washakie Formation. The two scenes are cleverly connected by the posture of Turnbull, who, bending over his sieve in search of fossils, appears to be peaking at the scene from the geological past unfolding beneath him. The fading of the sky’s blue in the black-and-white sands completes the illusion. Strangely enough, the 1950s seem more remote than the Eocene period.

Figure 1 Bill Turnbull’s Eocene by Adrienne Stroup. 2016.

Stroup’s visual tribute to Turnbull points to the fact that the paleontological community also has a tradition of appreciating its own past. No scientific field can thrive as such without its current members acknowledging the work of their predecessors and, by doing so, forging connections that unites them through time and space in one research community. Paleontology is a “science of the archive” (Daston Reference Daston2012), not only because it deals with fossils, the “archives” of life, but also because it relies on the archived work of predecessors. Studying the depths of geological time, just like studying the immensity of the universe, requires collaboration across many generations. When paleontologists study fossil specimens stored in museum or university collections, they deal simultaneously with natural “archives” and human archives, remains of past life informed by the work of predecessors. It is the intergenerational sum of this work, which sometimes adds its own puzzling history (Stimpson et al. Reference Stimpson, Jukar and Bonea2024), that allows for paleontological research to generate new insights. One example of such intergenerational archival work is the global cataloguing of foraminifera, first spearheaded by micropaleontologists Brooks F. Ellis and Angelina R. Messina. Funded by the United States Work Progress Administration in the midst of the Great Depression of the 1930s (Croneis Reference Croneis, Ellis and Angelina1942), the collection and classification of fossil foraminifera turned into an endeavor spanning across borders and decades, way beyond the lifespan of its original editors, who, by the time of Ellis’ passing, had published sixty-nine volumes. Today, more content continues to be added to the catalogue on a yearly basis, making it an almost century-long archival project.

The paleontological community has a long tradition of acknowledging the contributions of its past members and of writing stories of foundation and growth for its science. In 1899, Karl Alfred von Zittel published the first authoritative history of geology and paleontology, emphasizing the international dimension of these two fields: “The questions of the highest import in Geology and Palaeontology are in no way affected by political frontiers” (Zittel Reference Zittel (von)1901, p. v).

In 1931, Henry F. Osborn, then Honorary Curator of vertebrate paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), published Cope: Master Naturalist. Dedicated to the life and accomplishments of Osborn’s late mentor, Edward D. Cope, this copious volume laid out a narrative of the early development of paleontology in the United States beginning with an age of “pioneers,” including Thomas Jefferson and Edward Hitchcock, leading on to an age of “founders,” including Joseph Leidy, Othniel C. Marsh and Cope himself. While Osborn was eager to preserve and celebrate the achievements of these men, he mostly hoped that his book would bring “posthumous justice” (Cope Reference Osborn1931, p. vii) to his mentor. Osborn’s biography of Cope and early history of American paleontology provided a storyline which greatly influenced the way the paleontological community (particularly its American contingent) tells its own story.

In the 1940s, George G. Simpson, then Associate Curator of vertebrate paleontology at the AMNH, followed in Osborn’s footsteps and published a couple of articles elucidating the beginnings of vertebrate paleontology in North America (Simpson Reference Simpson1942, Reference 53Simpson1943). In 1960, J. Marvin Weller presented in the Journal of Paleontology a four-part periodization of the “development of paleontology” from Aristotle to Simpson (Weller Reference Weller1960). In the 1980s, Henry N. Andrews published a history of paleobotany, Fossil Hunters: In Search of Ancient Plants (Andrews Reference Andrews1980), Eric Buffetaut composed A Short History of Palaeontology (Buffetaut Reference Buffetaut1987), and Stephen J. Gould offered, among many other writings, an essay on historical conceptions of geological time, Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle (Gould Reference Gould1987). Beginning in the 2000s, Philippe Taquet published the first two volumes of what was intended to be a three-part biography of Georges Cuvier (Taquet Reference Taquet2006, Reference Taquet2019). In 2018, Adrian Lister retraced the history of Darwin’s fossil collecting during his voyage on the Beagle (Lister Reference Lister2018).

It is clear, then, that since its beginnings, the paleontological community has shown not only a strong appreciation for the presence of the Earth’s past, as one would expect, but also an active engagement with the presence of its own past. With an ongoing tradition of historical writing, the paleontological community has, over the years, worked on interpreting and recovering some of its past.

1.2 Re-appreciating the Presence of the Past

Recently, a growing number of initiatives from within the paleontological community has begun to challenge this tradition. For their authors, the past of the paleontological community should be re-appreciated. This marks an unprecedented turn in the history of the paleontological community’s engagement with its own past. Much has been written about the history of paleontology, but shouldn’t we look at it again? Such is the question that has been gaining in strength in recent years. A question which raises a series of others: Who is the “we” that has been writing the history of paleontology and its community? Whom did that “we” include and exclude? Whom did it remember and forget? How does the “we” of today compare with the “we” of yesterday? The present paleontological community is knocking on the door of its own past with a renewed set of interests, less concerned with pioneering ages, stories of great discoveries, and spurts of progress. Instead, the reappreciation of the paleontological community’s past is concerned with persistent inequities and problematic practices that might impede on paleontological research and its social implications. It is not a search for origins but a search for perspectives on present issues. While the tradition of appreciating the past had been about building a community, with its shared stories and founding figures, the growing efforts to reappreciate the past are about reforming and reimagining that community.

During the spring and summer of 2014, paleontologist Ellen Currano and filmmaker Lexi Jamison Marsh asked women working in paleontology to be photographed in the field or in their laboratories wearing fake beards. The result is a series of provocative, often humorous, black-and-white portraits (Figure 2) parodying the iconic pictures of rugged “fossil hunters” (Figure 3) that have come to mostly define the visual and popular identity of paleontology (Panciroli Reference Panciroli2017). As an artistic commentary on the history of gender inequities within paleontology, the “Bearded Lady Project” (Marsh and Currano Reference Marsh and Currano2020) brings to light the necessity for the paleontological community to engage creatively with its own past, both through words and images, if it is to benefit from and to all interested individuals. This project is but one contribution within a broader and growing conversation on the inclusion of people who have historically been either excluded, marginalized, or neglected in paleontology and the geosciences due to their non-conforming gender identities (Olcott and Downen Reference Olcott and Downen2020), their neurodiversity (Kingsbury et al. Reference Kingsbury, Sibert and Killingback2020), or their disabilities (Chiarella and Vurro, Reference Chiarella and Vurro2020).

Figure 2 Leckie Lab: University of Massachusetts Amherst: Adriane R. Lam, PhD candidate in micropaleontology; Raquel Bryant, MS student of micropaleontology; and Serena Dameron, PhD candidate in micropaleontology

Figure 3 Othniel C. Marsh with his assistants. 1871. Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

More recently, in 2022, a collective of researchers published in Nature Ecology & Evolution the results of a scientometric study showing how historical events and their legacy continue to play a part in the sampling biases that characterize the fossil record. By arguing that “Spatial sampling biases are borne out not only by geological and physical factors influencing the fossil record, but also by pervasive historical and socioeconomic factors” (Raja et al. Reference Raja, Dunne and Matiwane2022, p. 150) that perpetuate international asymmetries in paleontological contributions, the authors highlighted the necessity to investigate the past of the paleontological community from a global and economic perspective. The results of the study also made clear that if the paleontological community stretches beyond political frontiers, as Zittel pointed out at the turn of the twentieth century, its history should not be hastily reduced to one of international collaboration and competition. Indeed, the means and opportunities to collaborate or compete have not been shared in equitable measures (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chattopadhyay and Dean2025). For the authors of the study, finding ways to measure historical factors affecting access to fossil material is a necessary step toward achieving the inseparable goals of improving our understanding of deep-time biodiversity and fostering global equity in paleontological research.

That same year, Pedro Monarrez and colleagues published in Paleobiology a piece hoping “to encourage further discussion about colonialism and racism in geology and paleontology” (Monarrez et al. Reference Monarrez, Zimmt and Clement2022, p. 181). As with the two previous examples, the past of the paleontological community is approached by the authors as a space that needs to be reappreciated. At the beginning of their article, the authors acknowledge that their reflections and research were significantly motivated by the “racial unrest in the summer of 2020” (Monarrez et al. Reference Monarrez, Zimmt and Clement2022, p. 174) that followed the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis; a tragic event which resonated worldwide with other contexts of racial inequities (Klein Reference Klein2020) and occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic which was already casting a harsh light on economic disparities across the world (Stiglitz Reference Stiglitz2022). Some members of the geosciences community responded to these events by implementing the virtual and comprehensive initiative “Unlearning Racism in Geoscience” (URGE), which offers anti-racism curriculum and resources “to deepen the community’s knowledge of the effects of racism on the participation and retention of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people in Geoscience.”Footnote 5

If extraneous factors and events have encouraged a renewed engagement with the past through the lens of social issues, these same attempts are also determined by changes affecting the field of paleontology more directly. Among these changes is the growing number of women working in the field. According to the Paleontological Research Institution website, the percentage of women holding a membership in the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology doubled between 1980 and 2017, from 18% to 36%.Footnote 6 One effect of this increase over the last forty years is that it has rendered even more striking the stagnant numbers of racial and ethnic diversity over the same period (Bernard and Cooperdock Reference Bernard and Cooperdock2018). Additionally, recent debates over specimen repatriation, such as the ones around the holotype specimen of Ubirajara jubatus, eventually returned to Brazil in 2023, have seen historical considerations play crucial argumentative functions. Focusing on issues regarding paleontological research conducted in Mexico and Brazil, Juan Carlos Cisneros and colleagues argued that:

[The] structure of colonial science – derived from the practice of science in the colonies – has given rise to ‘scientific colonialism’ in the post-colonial world, some of whose extractive practices are sometimes referred to as parachute science, helicopter research, or even parasitic science. Within scientific colonialism, middle- and low-income countries are perceived as suppliers of data and specimens for the high-income ones, the contributions of local collaborators are devalued or omitted, and the legal frameworks in lower income countries are trivialized or even ignored. In turn, colonialist nations, owe their wealth to these colonial practices that have existed for centuries, allowing them to accumulate knowledge, power and financial resources. These extractive practices persist in the field of palaeontology to this day.

More broadly, the movement to decolonize natural history collections and develop renewed narratives around them to educate the public (Das and Lowe Reference Das and Lowe2018, Armstrong and Sharp Reference Armstrong and Sharp2024, Hide Reference Hide2024, Hurst et al. Reference Hurst, Moore and Simpson2024) has also been encouraging the re-appreciation of paleontology’s past. In 2018, a team of researchers from the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin revisited the history of the specimens of the Brachiosaurus Brancai found at the beginning of the twentieth century at Tendaguru Hill, in current Tanzania, questioning the inherited narrative of its discovery:

In additions to deconstructing the narrative, we also seek to recontextualize it – that is, to place the expedition and its finds within their broader historical, sociopolitical and musicological contexts. …The Tendaguru specimens uniquely embody the complex ties between colonialism, natural history and museums, and we use them to examine the conditions that permitted these and other fossils to be claimed, extracted, removed from their countries of origin and appropriated. …Given this history, the Tendaguru fossils raise the urgent question of who ‘nature’ really belongs to.

For the paleontological community, these new forays into the past make its history both harder to recognize and more urgent to understand. It is not surprising that these reappreciations of the past are sometimes met with skepticism or resistance. Some will want to defend the legacy of the “pioneers” and “fathers,” whose scientific accomplishments, they fear, might be obscured by anachronistic moral judgments. But the value of these efforts to reappreciate the past of paleontology does not lie in an attempt to separate “heroes” from “villains.” Instead, their value resides in the desire to engage with the past in ways that can help the paleontological community reconsider its inherited practices, culture, and institutions to improve its scientific production and social relevance. To build a sustainable paleontological community for tomorrow, a new, shared approach to the field’s past is needed.

1.3 Objectives and Plan

The first objective of this Element is to provide a conceptual toolkit to help with the interpretation of the unprecedented position in which the paleontological community finds itself regarding its own past. The second objective is to present historiographical resources and provide suggestions to assist the members of the paleontological community in engaging with the past of their field in the most beneficial way.

Section 2 details three different ways in which a community can engage with its past, following a distinction drawn by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. His distinction of three “species” of history (monumental, antiquarian, and critical) is mobilized in section 3 to assess how the paleontological community has traditionally been engaging with its past and what the limitations of this kind of engagement are. Section 4 introduces recent perspectives in the historiography of paleontology and explains how they could benefit the paleontological community in cultivating a renewed engagement with its past. Section 5 provides some suggestions on how to cultivate this new engagement with the past at the instruction, publication, and research levels. Standing as a conclusion, Section 6 reflects on the similarities that paleontology and the history of paleontology share as historical disciplines, and how these similarities should encourage cooperation for the mutual benefits of members of the paleontological community and historians. Section 7 consists in a thematic bibliography designed to facilitate the exploration of recent perspectives in the historiography of paleontology.

2 Three Species of History

2.1 An Historical Reckoning

It appears that the paleontological community is currently living through an historical reckoning. In light of the examples discussed in the previous section, the sources of this reckoning are numerous and complex, coming both from within and beyond the paleontological community. But it is certainly for the first time, in the two centuries of its existence, that this community is confronted with the emergence, within its own ranks, of historical discourses and commentaries that situate the field within broader ethical, social, economic, and global problematics. Instead of contributing to a more traditional narrative of progress in knowledge and methods, these discourses and commentaries point at inequities which, they argue, have limited access to the field in the past and which legacies continue to do so at the present time. The emergence of this new approach raises the question of what the paleontological community should do with its own past. Should it care about the broader historical context of the field’s developments? Should it leave such matters to historians? Should it limit itself to a version of its history focusing strictly on scientific matters? How much credit should it give to these new historical discourses? And if they deserve any, what good can they serve? The paleontological community is living through an historical reckoning because it faces, more urgently and explicitly than ever before, the need to choose the way in which it will engage with its own past.

Such interrogations are inevitably sources of tensions. Some might welcome the rise of new approaches to the field’s past as a much needed response to present challenges, while others might interpret it as an unwarranted attack on a past that had usually been a source of pride or, at the very least, a consensual object of intellectual curiosity. On both ends of the spectrum, there will be reasons to feel strongly about how the field’s past should and shouldn’t be approached. The reason behind such disagreement, I argue, lies in the variety of ways in which a same community can engage with its own past and which one(s) its members have learned to practice and value. To address this complex and delicate situation, it is therefore necessary to be able to distinguish between different ways of engaging with the past. Drawing clear distinctions should facilitate a productive conversation over what the paleontological community should do with its own past, how it has dealt with it until now, and how it might need to deal with it tomorrow.

To draw such distinctions, I propose to rely on an influential piece of philosophy of history, “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” an essay published by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in 1874. In this essay, Nietzsche distinguishes between three “species” of history, or ways in which a given community can approach its own past. The philosopher named these three species, monumental, antiquarian, and critical. Acknowledging the irreducible need for history in the life of any human community, Nietzsche tackled the problem of evaluating when “the study of history is something salutary and fruitful for the future” (Nietzsche Reference Nietzsche1997, p. 67) and when it ceases to be so.

To each species of history (monumental, antiquarian, and critical), the philosopher recognizes advantages and disadvantages. This chapter offers a working characterization of each species and shows how they can be used as conceptual tools to analyze the different ways in which the paleontological community has been engaging with its past. The aim of this section is not to comment on Nietzsche’s philosophy of history,Footnote 7 but rather to show how his distinction of three species of history can readily be mobilized to help clarify the challenge that the paleontological community is now facing regarding its own past. The following sections will discuss, in order, monumental history, antiquarian history, and critical history, illustrating each of them with examples related to the paleontological community.

2.2 Monumental History

Monumental history, as for the other two species of history, answers in a specific way the necessity that a given community has to engage with its past. As its name indicates, practicing monumental history consists in searching the past for “monuments,” landmarks of great accomplishments performed in the face of adversity, which may serve as sources of inspiration in the present. Looking at the past through such a lens, one “learns from it that the greatness that once existed was in any event once possible and may thus be possible again” (69). The value of monumental history lies in its ability to turn the past into a collection of examples that remind us that great things have been and can still be achieved despite doubts and difficulties.

Like any other community of science workers, the paleontological community has been engaging in monumental history to find, in its past, examples of great figures and accomplishments to emulate. In fashioning a collection of bright examples, a scientific community can simultaneously find pride in what has been accomplished by its predecessors and hope in what can be achieved by future generations. The monumental investment in the past by the paleontological community can be observed in a number of written tributes, events dedicated to the memory of past members, and actual monuments, such as statues of important figures in the field (Figure 4). All of these serve the important purpose of remembering “models, teachers, comforters” (67) to look up to when tackling the great tasks of the present. A most compelling example of the paleontological community cultivating a form of monumental history can be found, as it is the case in all other scientific fields, in the naming of prizes and awards after prominent contributors. Designed to recognize the accomplishments of younger members, such as the Alfred Sherwood Romer Prize from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, or more seasoned members, such as the Raymond C. Moore Paleontology Medal from the Society of Sedimentary Geology, these honors are also meant to actualize, in the form of periodic rituals, a connection between the great achievements of the past and those of the present. Year after year, the growing list of awardees constitutes its own memory of great accomplishments to look up to.

Figure 4 Statue of Georges Cuvier by David d’Angers. 1835.

Members of the paleontological community continue to look for and elevate figures from the past which they believe could inspire their community to surmount present challenges in the field. In recent years, for example, a number of initiatives have brought to light the accomplishments of pioneering women in paleontology in the hope of (a) providing paleo-enthusiastic girls and women with role models and (b) encouraging future efforts toward gender equity in the field. As the webpage of the 2020 exhibition Daring to Dig: Women in American Paleontology explains: “Despite [ … ] barriers, pioneering women found ways to surpass stereotypes, circumvent obstacles, and forge new paths in their efforts to contribute to the science of paleontology.” Presenting a gallery of women who contributed to the field from the seventeenth century to the present day, this exhibition could be interpreted as an exercise in monumental history, as far as its ambition to elevate new figures from the past who found ways to weather adversities is concerned.Footnote 8 In a similar effort, although taking quite a different form, a statue commemorating the British fossil collector and paleontologist Mary Anning (1799–1847) was inaugurated in Lyme Regis in May 2022 (Figure 5). This inauguration was the culmination of a campaign, “Mary Anning Rocks,” launched by a local schoolgirl and her mother four years prior. Such initiatives show that, despite what the adjective may suggest, monumental history is not a static way of engaging with the past. It is a continuous search for figures from the past to erect as monuments for the benefit of the present. New monuments arise, others crumble, while some endure, depending on what sort of inspiration members of the paleontological community believe they most need from the past.

Figure 5 Bronze sculpture of Mary Anning by Denis Dutton. 2022.

Despite all its benefits for the present and future of a community, some disadvantages are also associated with monumental history. The elevation of any figure from the past to the status of example runs the risk of idealizing that figure by making abstraction of details and circumstances which would prevent it from serving as an equivocal source of inspiration. Indeed, “as long as the past has to be described as worthy of imitation, as imitable and possible for a second time, it of course incurs the danger of becoming somewhat distorted, beautified and coming close to free poetic invention” (Nietzsche Reference Nietzsche1997, p. 70). The risks of monumental history lie in how the “beautified” version of the past might, unseemly, come to (a) impoverish the past by stripping it of its nuances and complexities, and (b) eventually stand for the only past that really matters. These risks, we will have to keep them in mind when, in Section 3, we will be discussing how the history of paleontology has traditionally been presented to aspiring members of the field in textbooks.

Monumental history is a way of looking at the past in search of inspiring examples to tackle the great tasks of the present with confidence. But if this engagement with the past answers a most important and collective need for role models, it also runs the risk of forgetting “whole segments” of the past (71), leaving it idealized, partial, and misunderstood.

2.3 Antiquarian History

In contrast to monumental history, antiquarian history is not searching the past for examples to emulate in the present, but is searching the present for past things to cherish and pass on to the next generations. Engaging in antiquarian history is “tending with care that which has existed from old” (72–73). Such an engagement with the past is motivated by the need to find and preserve the roots of one’s own existence and what made it possible. Its main advantage for the life of individuals and communities lies in the cultivation of a feeling of both belonging to a larger whole and an appreciation for what was inherited from the past. It is akin to “the contentment of the tree in its roots” (74).

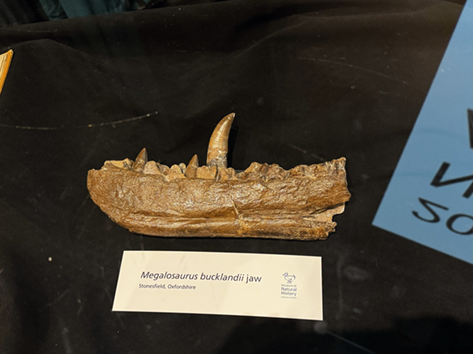

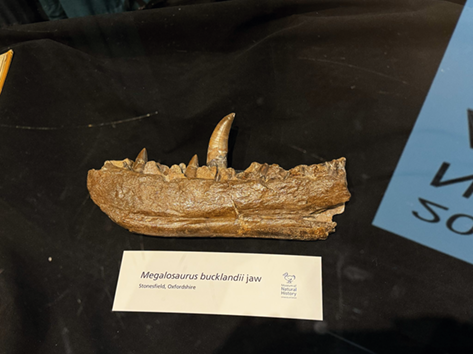

In addition to the examples of monumental history discussed earlier in this chapter, members of the paleontological community have also been practicing antiquarian history. Just as turning certain individuals of the past into examples to emulate is important to encourage future accomplishments in the field, caring for what was left behind by preceding members of the field is important to foster a sense of (a) appreciation for the continued existence of the field, and (b) belonging to its intergenerational community. This form of engagement with the past can be witnessed in anniversary events or publications celebrating foundational moments in the history of the field and providing opportunities to appreciate and reflect on the work accomplished since then. In 2024, for example, the paleontological community, especially its members interested in dinosaurs, celebrated the 200-year anniversary of what is considered to be the first valid scientific description and naming of dinosaur remains, published by British geologist and paleontologist William Buckland in the Transactions of the Geological Society of 1824 (Buckland Reference Buckland1824). Among the many special publications and events marking the bicentennial of the naming of Megalosaurus, the Natural History Museum in London hosted an international conference at which were exhibited the original jaw fragment described by Buckland along with an original copy of his publication (Figure 6). The value of having the original specimen at such an event resides, of course, in it being the first holotype of a dinosaur, but even more so in the emotional response it might prompt in those who, two centuries later, can “see” in it the origins of their field and their own work. The care taken in preserving and exhibiting such remains from the past is not only justified by their obvious scientific value, but also by their value as roots for an entire community of dinosaur specialists.

Figure 6 The Megalosaurus jaw from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History exhibited at the Natural History Museum in London.

Despite these clear benefits, there remain potential dangers associated with an excessive antiquarian approach. While such engagement with the past provides useful opportunities for a community to cultivate meaningful connections with its past, its feeling of appreciation for what came before might run the risk of becoming too acute. As is the case with an excessive monumental approach, an unchecked antiquarian approach limits the ability to fully understand the past. Focused on the care and respect for roots, “[t]he antiquarian sense of a man, a community, a whole people, always possesses an extremely restricted field of vision” (Nietzsche Reference Nietzsche1997, p. 74). While monumental history can lead from inspiration to idealization, antiquarian history can lead from appreciation to reduction. In both cases, the challenge lies in the ability of a community to remain aware of the many ways in which it engages with its past.

2.4 Critical History

A critical outlook on the past does not consist in a search for inspiring examples, nor in a search and care for roots. It consists in an examination of parts or aspects of the past seen as particularly unjust and which legacies are still affecting the present. Instead of seeking inspiration from the past as monumental history does, or seeking a sense of appreciation and belonging from the past as antiquarian history does, critical history “seeks deliverance” (67) from the unjust things that have been inherited from the past. The need for critical history arises when forgetting certain past injustices is no longer an option and there is a need “to be clear as to how unjust” (76) something inherited from the past is.

This sort of engagement with the past, the paleontological community has recently seen it emerge within its own ranks. The “Bearded Lady Project”, cited in the introduction, is one example of such a critical engagement with the past, addressing, in this specific instance, the legacy of gender discrimination in paleontology. Other injustices inherited from the past have also begun to be addressed more explicitly, prompting the recovery of stories neglected until now. Since the second half of the 2010s, a collective of researchers has been working on unearthing the history of indigenous paleontology in South Africa. Blending methodologies from geomythology,Footnote 9 archeology, paleontology, and archival research, this initiative is helping evaluate how indigenous people’s cultural interpretations of fossils might have contributed to modern re-discoveries of fossil sites and could continue to do so in the future (Benoit Reference Benoit2018, Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Penn-Clarke and Rust2024, and Helm et al. 2018). Such an endeavor provides historical evidence to help develop a more equitable culture of recognition and credit in paleontology (Valenzuela-Toro et al. Reference Valenzuela-Toro, Viglino and Loch2025). In 2023, Hannah Kempf and colleagues published a historical review of the United States’ policies governing paleontological research on Native American lands (Kempf et al. Reference Kempf, Olson and Monarrez2023). This publication aimed at bringing the attention of the paleontological community, not only toward an “unfortunate history of fossil dispossession from Native American lands” (200), particularly during the mid-nineteenth century, but also toward present “policy gaps and ambiguities surrounding fossil collection on Native American lands” (194) which perpetuate, granted in different ways than a century and a half ago, this history of dispossession. In this case, critical history entails the gathering of information and evidence necessary to recount past injustices, evaluate their repercussions on the present, and suggest future ways of remedying them.

While critical history might allow a community to recognize and address old injustices which effects and legacies it does no longer tolerate, this form of engagement with the past “is always a dangerous process” (Nietzsche Reference Nietzsche1997, p.76), as those criticizing the injustices of the past still remain themselves “the outcome of earlier generations, [ … ] of their aberrations, passions, and errors” (76). The burden of past injustices is not easily removed, and this persistence might make any efforts to address them appear futile. Another potential risk is that of adopting a critical outlook on the past without the clearly recognized need of addressing any specific injustices in the present. Since “every past [ … ] is worthy to be condemned – for that is the nature of human things: human violence and weakness have always played a mighty role in them” (76), criticizing the past for its own sake could lead one down the path of raising an interminable list of retrospective grievances and condemnations without any clear benefits for the present.

2.5 A Conceptual Toolkit

This distinction between three species of history (monumental, antiquarian, and critical) can be used as a conceptual toolkit to clarify the nature of the historical reckoning the paleontological community is currently facing. Mobilizing these three species should help identify, evaluate, and compare the different ways it has been engaging with its past. While the following sections propose an interpretation of this historical reckoning and suggest steps to approach it, the main objective in laying out the distinction between three species of history is to provide conceptual tools for the benefit of a constructive conversation about what the paleontological community has been and should be doing with its past.

Before proposing an interpretation of how the paleontological community has traditionally been engaging with its past and transmitting it to its upcoming members, it is important to point out that the three species of history, like any other conceptual distinctions, do not neatly correspond to clear-cut observable ways of engaging with the past. Individuals and communities entertain complex, and often contradictory, relationships with the past. Characteristics of monumental, antiquarian, and critical histories might be recognizable in the same initiative or publication, and, as we saw throughout this section, the same community engages with the past in multiple ways simultaneously. Monumental, antiquarian, and critical histories are only the tools this Element proposes to use to analyze, evaluate, and compare the ways in which the paleontological community has been engaging with its past. They do not stand for the ways themselves.

It is also important to underscore that these three species of history, as conceptualized by Nietzsche, are part of a well-established canon of Western philosophy. The decision to mobilize them in this Element does not presume their superiority over other ways of thinking about the past. Arguably, the development of an always more inclusive paleontological community calls for the recognition and integration of diverse worldviews and relationships to human and non-human pasts, in particular from non-Western and Indigenous cultures (Howe and Rieppel Reference Howe and Rieppel2024, Hurst et al. Reference Hurst, Moore and Simpson2024). On one hand, the decision to rely on this threefold distinction is a reflection of my European cultural background and academic training. On the other hand, this distinction can easily be mobilized to begin disentangling some ambiguities inherent to the value-laden and polysemic notion of history, facilitating therefore a constructive conversation over the paleontological community’s engagement with its own past and why it matters.

3 Textbook History of Paleontology

There are many places and times for members of a given scientific community to learn about the history of their field and to develop a certain picture of its past. Surely, this part of any member’s education can be experienced as a continuous process by those who, either because of their research agenda or their personal curiosity, actively engage with the work of some of their predecessors. But among the variety of ways through which individual members of the same community can come to learn about the past of their field, textbooks constitute a key locus for the articulation, transmission, and consolidation of a shared narrative. For this reason, taking a closer look at how the history of paleontology has been told in introductory textbooks should provide valuable insights on how the paleontological community has traditionally been intending to teach its upcoming members to approach the field’s past.

Focusing solely on textbooks has obvious limits, since instructors might assign additional readings and other contents, prepare materials, and give lectures on historical topics beyond what is covered in the textbooks they use as references, or avoid textbook historical exposés altogether. Textbooks are also not accessible to all students equally and not all vocational paleontologists took formal coursework in paleontology or related fields. A much broader study, including a survey of instructors, would be necessary to draw more solid conclusions on at least the current state of the teaching and transmission of the field’s history. Nevertheless, textbooks, as cornerstone publications dedicated to the training of aspiring members of the field, can be approached as artifacts recording over time the kind of history and the place generally attributed to it in such training. They constitute a relatively homogeneous group of traces that can be compared with each other to begin reconstructing the evolution of the teaching of paleontology’s history. Although this method might not bring the most precise conclusions, it suits the aim of this section to help clarify the complex position in which the paleontological community finds itself regarding its relationship to its own past.

After reviewing a small selection of textbooks, this section mobilizes the three species of history to (1) characterize the kind of engagement with the field’s past that has traditionally been transmitted to students of paleontology, and (2) evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this kind of engagement.

3.1 A Short Review of Textbook Histories

This section analyzes a small selection of textbooks to provide the reader with a general idea of how the history of paleontology has traditionally been presented to students. All the textbooks selected have at least one segment dedicated to the history of the field, but, of course, not all textbooks reserve distinct paragraphs to discuss this topic. This fact alone is significant, for even the decision to not include a discussion of the past constitutes a way to engage with it and might tell us something about a more general approach to the past shared within the authors’ community.Footnote 10 But rather than speculating on the absence of historical considerations, this section describes how the history has been told when it has been explicitly covered in textbooks.

Published in 1955, Edwin H. Colbert’s Evolution of the Vertebrates summarizes the history of paleontology in one paragraph:Footnote 11

To the peoples of the classical civilizations the nature of fossils was hardly realized, and it was not until the days of the Renaissance that a true understanding of fossils was reached by (among others) that great and accomplished Florentine, Leonardo da Vinci. The scientific study of fossils, however, is barely more than a century and a half old, whereas the modern evolutionary interpretation of the fossil record really begins with the work of Charles Darwin, as crystallized in his epochal book The Origin of Species. In spite of the relative youth of paleontology as a science, an impressive amount of fossil material has been gathered together and studied by paleontologists all over the world.

The speculations of ancient philosophers over the nature of fossils, the genius insights of Renaissance scholars like Leonardo da Vinci, and the revolution prompted by the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species are among the main episodes in the history of paleontology that one usually encounters in textbooks. In fact, these episodes can already be found in anterior publications, such as in Marcellin Boule and Jean Piveteau’s Fossils: Elements of Paleontology (Boule and Piveteau Reference Boule and Piveteau1935, p. 33–46) or in Charles Schuchert and Carl Dunbar’s Historical Geology (Schuchert and Dunbar Reference Schuchert and Dunbar1941, p. 20–22).

At the beginning of the 1960s, William L. Stokes dedicated a short section to the history of paleontology in his Essentials of Earth History: An Introduction to Historical Geology (Reference Stokes1960). The author cites the names of Aristotle, Da Vinci, Johann Scheuchzer, and William Smith in a story beginning with the mystical and magical interpretations of fossils by “many primitive and prehistoric peoples” (Stokes Reference Stokes1960, p. 79) and ending with “Smith’s methods of correlation” (81).Footnote 12 At the end of the same decade, David L. Clark wrote a three-page history of paleontology for the introductory chapter of Fossils, Paleontology and Evolution (Reference Clark1968). Clark’s historical section references a dozen philosophers and scientists, from Herodotus and Aristotle to Cuvier and Darwin, and frames the story around the resolution of the problem, “are fossils organic or inorganic?” (Clark Reference Clark1968, p. 2), and how, once this problem had been solved, paleontology was able to consolidate into a science contributing to the study of the Earth’s history and evolution.

Fifteen years later, Bernhard Ziegler provided an even richer preface on the “scope and development of palaeontology” in his Introduction to Palaeobiology (Reference Ziegler1983). The story follows the same storyline as Colbert’s and Clark’s, beginning with the ancient Greeks, noting the “exceptions” (Ziegler Reference Ziegler1983, p. 10) of Da Vinci and a few other Renaissance scholars, to finally end with the discipline-defining work of the likes of Cuvier and Smith. Although similar in that respect to previous textbook accounts, Ziegler’s three-page preface cites more than forty names, which beyond Herodotus, Aristotle, da Vinci, Cuvier, and Darwin, also includes figures like Bernard Palissy, Benoît de Maillet. James Sowerby, and Othniel C. Marsh. As an addendum to the main narrative, Ziegler dedicates short paragraphs to name some important contributors in the history of micropaleontology, invertebrate paleontology, and paleobotany. The author lists Zittel’s History of Geology and Palaeontology (Reference Zittel (von)1901) and Wilfred N. Edwards’ The Early History of Palaeontology (Reference Edwards1967) as its two historiographical references. Published in the same decade, Paleontology: The Record of Life (1989), by Colin Stearn and Robert Carroll, devotes the equivalent of one page to the history of paleontology. The authors evoke the “early speculations” (Stearn and Carroll Reference Stearn and Carroll1989, p. 5) of Greek philosophers, including Xanthos of Sardis and Aristotle, before mentioning the debates on the origins of “figured stones” during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, to finally explain how by the beginning of the nineteenth century, the origins of fossils as remains of extinct organisms had been established. The section is illustrated by a plate of figured stones by eighteenth-century Swiss naturalist Karl Land. In contrast to Ziegler’s history, this one is almost completely devoid of names. The author cites The Birth and Development of the Geological Sciences (1938) by Frank D. Adams as its historiographical reference.

By the end of the 1990s, the textbook history does not appear to have changed significantly. In Bringing Fossils to Life (1998), Donald Prothero delivers, in an illustrated, four-page “What is a fossil?” section, a narrative similar to its predecessors in both structure and cast. Dedicating a paragraph to Da Vinci, the author also discusses extensively the work of Nicholaus Steno. Notably, Prothero mentions, although in passing, how the work of Smith on index fossils had been prompted by engineering projects characteristic of the Industrial Revolution. This detail constitutes a rare hint at how broader historical factors might have been a part of the history of paleontology. For further reading, the author suggests Martin Rudwick’s The Meaning of Fossils (1972).

The first edition of Introduction to Paleobiology and the Fossil Record (2009) by Michael Benton and David Harper offers an account of the historical “steps to understanding” of fossils (Benton and Harper Reference Benton and Harper2009, p. 9). The narrative’s cast is comparable to the ones described earlier in this section and includes some of the same remarkable episodes. For example, it cites Xenophanes’ and Herodotus’s “early speculations” (9) and Da Vinci has a short paragraph dedicated to his interpretation of fossil shells observed in the Italian mountains.Footnote 13 The section is richly illustrated with, among others, the famous plate showing a shark head from Steno’s work on glossopetrae and an illustration by Edouard Riou from Louis Figuier’s popular science bestseller The World Before the Deluge (1863). In addition to this section, the authors set aside a few paragraphs for some historical comments on “Paleontology and the history of images,” from the first drawing reconstructions of extinct animals to Jurassic Park (1993) and Walking with Dinosaurs (1999). The second chapter offers also a history of biostratigraphy featuring figures like Smith and Roderick Murchison. As in Prothero’s textbook, the authors allude to a broader historical context when pointing out that “one of the first systems to be named was the Carboniferous (“coal-bearing”), a unit of rock that early industrialists were keen to identify!” (27–32). Among the reading suggestions related to the history of paleontology, the authors list Rudwick’s The Meaning of Fossils and Scenes from Deep Time (1992) as well as Buffetaut’s A Short History of Vertebrate Palaeontology (Reference Buffetaut1987). The second edition of Benton and Harper’s textbook from 2020, apart from additions to the “Paleontology and the history of images” section, does not include noticeable changes to the historical account.

A few observations can be drawn from this short review. First, the history of paleontology presented to students in textbooks has not experienced any fundamental changes in, at least, the last seventy years. Despite some differences between the historical accounts discussed in this section, each constitutes a version of a same narrative telling the story of how fossils came to be understood “as fossils,” to quote Benton and Harper’s expression. Second, the main cast of the story remains notably fixed: Herodotus, Aristotle, Da Vinci, Steno, Cuvier, Smith, and Darwin being among the most systematically cited. Third, apart from a few hints in versions like Prothero’s, and Benton and Harper’s, the story unfolds with little to no reference to a broader historical context.

Mobilizing our conceptual toolkit to characterize the kind of engagement with the past which appears to have been prevalent in textbooks should allow for an evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages that the paleontological community, especially its upcoming members, may experience from the transmission of such a narrative. The traditional textbook narrative mostly displays characteristics of both monumental and antiquarian histories. It does not only present a gallery of great philosophers and scientists who contributed to solve the “riddle” of fossil remains, but also situates the deepest roots of paleontology as far back as ancient Greece. As the previous section made clear, both monumental and antiquarian histories have advantages and disadvantages for the community who engages in them. The next two sections identify them respectively.

3.2 Advantages of the Traditional Textbook History

The traditional textbook history of paleontology has obvious advantages for the training of prospective members of the paleontological community. As a monumental history, it provides a shared and recognizable set of important past contributors to the field. As an antiquarian history, it also provides an origin story spanning multiple centuries. Both help, as philosopher and historian of science Thomas Kuhn pointed out, in building a sense of community: “Characteristically, textbooks of science contain just a bit of history, either in an introductory chapter or, more often, in scattered references to the great heroes of an earlier age. From such references both students and professionals come to feel like participants in a long-standing historical tradition” (Kuhn 1990, p. 138).

The clear succession of episodes and the relative concision characteristic of the textbook narrative amount to an easily transmissible story, requiring little time and space to reach its goal of fostering a sense of community. Additionally, the lack of references to the broader historical context in which paleontology developed into the scientific field it is today minimizes distraction, which helps in setting the stage for the transmission of the field’s most current methods and knowledge, the textbook’s raison d’être.

Combining elements of monumental and antiquarian histories, the narrative traditionally found in introductory textbooks serves the paleontological community in providing its members with an inspiring origin story of the field, peopled with prominent figures whose work laid down the foundations of today’s science. The narrative serves to remind students that no matter how obvious the nature of fossils may now seem, this certainty is owed to the centuries of intellectual and scientific efforts that preceded them. In this regard, and in addition to its value as a source of inspiration and in community-building, the traditional textbook narrative can also serve to instill a sense of intellectual humility ahead of the work that remains to be accomplished in the field.Footnote 14

3.3 Disadvantages of the Traditional Textbook History

Despite its advantages, the traditional textbook history of paleontology, like any other monumental or antiquarian history, also holds potential disadvantages.

As a monumental history, the textbook history might provide a misleading picture of the kinds of actors that have been contributing to the advancement of paleontological knowledge and methods. Within the limited space assigned to a historical section in a science textbook, choices have to be made and names have to be left out to tell a coherent story. This is arguably the case with any account of the past, even the most comprehensive. The potential disadvantage of the textbook history as a monumental history does not lie in the necessity of selecting, but in the selection traditionally made. The textbook history focuses exclusively on authors who contributed essays, treatises, and scientific publications. While there are many valid reasons to reserve a significant portion of the narrative to this category of actors, focusing exclusively on it leaves unacknowledged a multitude of other actors whose contributions, although not taking a written form, were necessary for the work carried on by those who wrote and published: preparators, artists, workers, miners, guides, informants, and fossil collectors, among others. Again, the spatial constraint of a textbook does not allow for exhaustivity and choices have to be made, but a choice favoring only authors runs the risk of delivering an impoverished historical account of the diversity of actors that makes up the paleontological community. The textbook history does not focus exclusively on authors, but on Western men authors. This triple selection obscures even more the interplay of different categories of actors that has been contributing to the advancement of paleontology. Authors stand alone in the traditional narrative, “like a range of human mountain peaks” (Nietzsche Reference Nietzsche1997, p. 68).

As an antiquarian history, the textbook history focuses on the roots of paleontological knowledge and methods, delivering an account of the history of the field reduced to strict matters of science, such as the nature of fossils or the use of fossils in geology and evolutionary biology. Just as there are good reasons for focusing on authors, there are good reasons for focusing on scientific questions in the confine of a science textbook. After all, the primary goal of a textbook is to introduce readers to the current state of the science. In that case, it seems only appropriate to provide a historical narrative focusing on the science as well. But, similar to the exclusive selection of authors, the exclusive selection of scientific matters provides a narrative dissociating paleontology from any other historical contexts and factors that influenced its own history: the extraction of geological resources, the development of museal institutions, or the establishment of geological surveys in national and colonial territories, among others. The reduction of the history of paleontology to a succession of ideas about fossils and their significance runs the risk of giving the impression that paleontology has been standing and growing aside from “all the rest of the forest around it” (74).

These limitations of the traditional textbook history of paleontology hold unforeseen consequences for the paleontological community today and its upcoming members. As discussed in the previous section, any kind of engagement with the past bears its lot of beneficial and deleterious consequences for the community that practices it. The intended benefits of the traditional textbook history of paleontology come at a price. By limiting itself to authors, it offers an impoverished portrait of the actors that have historically taken part in the advancement of the science. By limiting itself to the succession of ideas, it gives out the impression that this advancement was not itself imbedded in broader contexts. The result is a narrative deprived of human complexity. As historian of science George Sarton once wrote, “such a history becomes quite dehumanized; it is not a true history, but merely the shadow of one” (Sarton Reference Sarton1949, p. 136).

One unforeseen disadvantage of this oversimplification is that the past is not presented as carrying into the present a complex legacy which informs, not only the state of today’s paleontological knowledge and methods, but also the current sociology, geography, economy, practices, and institutions of the field. It risks disconnecting present challenges within the paleontological community from their historical component, making them even harder to recognize, understand, and address. At a time that “palaeontology, and the geosciences more broadly, are currently grappling with overdue conversations around the societal and economic impact of their research practices” (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Raja and Stewens2022, p. 8), the traditional textbook history of paleontology misses on the opportunity to make the past useful for the future. Even further, the kind of engagement with the past that it transmits might come to stand in the way of cultivating a more complex understanding of the history of the field that could help understand and address a host of contemporary issues, such as specimen repatriations (Howe and Rieppel Reference Howe and Rieppel2024), parachute science (Thompson Reference Thompson2023), evolving fossil legislations (Liston Reference Liston2018), and gender gap in the field (Black Reference Black2018).

3.4 Beyond the Traditional Textbook History

As conceded at the beginning of this section, relying on a short review of textbook historical accounts to evaluate how the paleontological community has traditionally been engaging with its own past has its limits. Nevertheless, when considered as artifacts recording the kind of historical engagement transmitted to upcoming members in the field, looking at textbook histories help shed some light on the historical reckoning that the paleontological community is currently experiencing. The traditional history of the field that has been transmitted for decades is losing relevance in the face of present challenges. Its benefits for the paleontological community are beginning to be outweighed by its disadvantages. Through this traditional historical engagement, the past ceases to be a helpful resource for the members of the paleontological community to tackle contemporary issues of accessibility to the field and equity within it. On the contrary, this traditional history promotes a vision of the past that might delay, if not even prevent, the widespread recognition across the paleontological community of long-running inequities that affect how the science is being carried out and who stands to benefit from its successes.

Wrestling with the growing concern of insuring that the study of the history of life on Earth actually benefits from and to a greater number of people, the paleontological community is facing the need to abandon one deeply rooted engagement with its own past and to grow a new, more critical one, in the sense defined in the previous section. This transition is inevitably made difficult by (1) an expected attachment to the traditional history of the field and (2) the disruptive and evolving nature of the new histories being written. To achieve this transition in the most productive manner, the paleontological community can count on a renewed historiography of paleontology, which has been working on resituating paleontology within global, economic, social, and cultural histories.

4 A New Historiography of Paleontology

This section introduces a new historiography of paleontology which could assist members of the paleontological community in cultivating an approach to the past better suited to address contemporary challenges, such as increasing accessibility to education and career paths in the field for people with diverse backgrounds and identities (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Johnson and Schroeter2022) or defining shared ethical research standards in response to evolving and complex global circumstances as in the case of Myanmar amber (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Raja and Stewens2022). This section opens with a brief historiographical overview characterizing the most recent approaches in the history of paleontology and what they propose. Mobilizing the three species of history detailed in Section 2, it proceeds with a discussion of the potential advantages that the paleontological community and its upcoming members could enjoy from engaging with that new critical historiography of paleontology.

4.1 Paleontology’s Place in History

Since the second half of the twentieth century, a growing cohort of historians of science has been challenging “the interpretations of an older historiography” of paleontology (Rainger 2008, p. 185), which tended to focus on prominent figures in the field and how their works had played a role in the discovery of the geological past. This historiography included primarily works by paleontologists, such as Zittel’s History of Geology and Palaeontology to the End of the Nineteenth or Edward’s The Early History of Palaeontology, both cited in the previous section.

Informed by broader changes in the methodologies and problematics of the history of science, historians of paleontology began to pay closer attention to the cultural and social contexts in which paleontological work had been done. In The Meaning of Fossils, Rudwick proposed to show how “each period’s interpretation of the meaning of fossils may be an illuminating reflection of that period’s view of the natural world” (Rudwick Reference Rudwick1985, preface). In Fossils and Archetypes, Adrian J. Desmond described his own approach to a study of mid-nineteenth century paleontological debates in the following terms:

So my strategy, broadly speaking, will be to investigate how far abstruse debates over mammal ancestry or dinosaur stance reflected the cultural context and the social commitment of the protagonists, and as a result to determine the extent to which ideological influences penetrated palaeontology to shape it at both the conceptual and factual level.

While approaches like Desmond’s allowed for an exploration of the complex interplay between culture, society, and science in the production of paleontological interpretations, the focus remained primarily, if not exclusively, on the Western context. Also, little attention was being given to the history of collections, fieldwork, preparation techniques, exhibitions, and the broader political context informing them. For instance, in the same study, Desmond intentionally left aside the question of the growth of paleontological collections in mid nineteenth-century London, addressing it only with brief references to the colonial and economic contexts of the period:

Whether the period saw an increase in the number of fossils shipped to London I do not know; certainly crates seemed to be arriving in Bloomsbury in ever increasing numbers from the colonies (particularly South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia), and my impression is that the “Coal age” vertebrates deposited in Jermyn Street increased considerably, as one might have expected given Britain’s predominant mining interests.

Historians of science eventually came to turn their attention more systematically toward things like the “crates” on which Desmond had chosen not to focus. They proceeded to show how labor (Shapin Reference Shapin1989), empires (Petitjean et al. Reference Petitjean, Jami and Moulin1992), gender (Schiebinger Reference Schiebinger1993), spaces (Livingstone Reference Livingston2000), and circulation (Secord Reference Secord2004) had been playing constitutive roles in the making of scientific knowledge. These “turns” in the general history of science set the foundations for a renewed historiography of paleontology investigating not only cultural and social influences on paleontology, but also paleontology’s influence on culture and society. Paleontology certainly has a history, but most importantly for this new historiography, paleontology counts as a historical player.

Investigating the global history of nineteenth-century mammal paleontology, The Age of Mammals (2023) by Chris Manias articulates some of the most characteristic perspectives of this new historiography of paleontology. First, it sets out to show that “numerous actors were critical for paleontological work: hunters, agricultural workers, miners, builders, preparators, artists, and others. These people were often subordinate but not powerless” (Manias Reference Manias2023, p. 382). Second, it investigates the interplay between paleontology and global power dynamics, reminding that a “persistent trend has been that work on fossils followed exploitation and control of territory” (383). Third, it uncovers the legacies of older paleontological ideas in today’s popular conceptions of the geologic past, evolution, and the environment. For example:

Despite constant refrains by paleontologists and evolutionary biologists to understand natural diversity in nonhierarchical manners, common language still refers to mammals as “higher” creatures, a norm in the animal world. References to animals like the rhinoceros and hippopotamus as “prehistoric,” and megafauna (both living and extinct) being valued as national or local icons, all persist from these nineteenth-century debates.

Finally, it explains (a) how the field and its community came to organize itself around specific geographical locations and institutional centers, since “large collections developed through taking advantage of extraterritorial and colonial links,” and (b) how these “structures of inequality and powers [ … ] have also persisted” (385).

Chapter 7, consisting in a thematic list of some of the most notable works belonging to this new historiography of paleontology, provides a broader picture of its various perspectives on paleontology’s past. But Manias’ remarks are representative of a general historiographical approach attentive to the impacts and legacies of paleontology’s past, both on the field itself and its present community and on “the current world” (4). This historiography takes seriously the cultural and social influence of paleontological work throughout history and in the present. The history of paleontology becomes a way to better understand a host of pressing issues, from public debates over environmental changes and conservation efforts to the balance of powers that has been shaping the production of paleontological knowledge.

4.2 Some Misunderstandings

A couple of common misunderstandings about such an historiographical approach need to be addressed to ensure a fair evaluation of its potential benefits to the paleontological community.

The broader contextualization of historical actors’ deeds, motivations, and ideas inevitably leads to more complex and contrasted portraits of their lives and accomplishments. For this reason, historiographical approaches that investigate an always more complex nexus of circumstances can be seen by some as working on tarnishing the image and reputation of generally well-regarded figures of the past. Discussing how Western paleontologists benefited from imperial endeavors, for example, does not aim at vilifying them. While such historical work is never completely free of moral consideration, its goal is not to separate the “heroes” from the “villains.” Instead, it is interested in reminding the part that contingency plays in any lives so as to better understand what made it possible for specific individuals and groups of people to think and act in the way they did. “They were people of their time,” a common phrase used to sometimes dismiss historical discourses that delve into what is seen as the unsavory part of the past, is precisely the relationship that historians are curious about: how were people defined by the time they lived in, and how did they make it “theirs”? A critical historiography aims at embracing the complexity and sometimes contradicting aspects of actors and events. It helps understand what made certain actions and practices possible by reconstructing and analyzing how historical actors justified or negotiated them. In this regard, it stands in clear contrast to the process of idealization and simplification that most often characterizes monumental and antiquarian approaches to the past.

A second misunderstanding is that bringing to light the interplay between past scientific work and its broader sociocultural context might amount to a depreciation of science, presenting it as a mere reflection of changing social norms and values. This sort of concern about the effects of historical and sociological analyses of science was at its peak during the infamous “science wars” at the end of the last century. The concern over such discourses chipping away at the credibility of paleontologists’ expertise and ability to know about the deep past is particularly legitimate considering that paleontology has been for a long time the target of anti-evolutionist, and creationist movements, especially in the United States (Padian Reference Padian2009, Laurence Reference Laurence2024). It is clear that the new historiography of paleontology inherits from the deconstructive approaches to science that emerged in the 1970s–1980s (Latour and Wooglar Reference Latour and Wooglar1979, Shapin and Schaffer Reference Shapin and Schaffer1985). For example, Lukas Rieppel opens his Assembling the Dinosaur (Reference Rieppel2019), a history of dinosaur exhibitions during America’s Gilded Age, in thought-provoking fashion:

The dinosaur is a chimera. Some parts of this complex assemblage are the result of biological evolution. But others are products of human ingenuity, constructed by artists, scientists, and technicians in a laborious process that stretches from the dig site to the naturalist’s study and museum’s preparation lab. The mounted skeletons that have become such a staple of natural history museums most closely resemble mixed media sculptures, having been cobbled together from a large number of disparate elements that include plaster, steel, and paint, in addition to fossilized bone.

Now, recognizing the complexity of paleontological reconstructions of extinct animals is not the same as reducing them to purely social constructs. Instead, an approach like Rieppel’s serves to open a whole field of investigation on the types of work and workers that have been making these reconstructions even possible. Its aim is not depreciative but heuristic: casting a light on the people, practices, and resources that contributed to make the paleontological community and the knowledge it produces about the deep past what they are today.

4.3 Potential Benefits

Mobilizing the three species of history, the new historiography of paleontology can best be described as a form of critical history. Investigating the local and global power relations that have informed the development of paleontology since the nineteenth century as well as uncovering its institutional and cultural legacies, this historiography could serve the present paleontological community, not by giving it new monuments and roots, but by bringing to its attention how the past is playing out in its present. Answering how he hoped his book The Age of Mammals could benefit the paleontological community, Manias explained, for example, that:

The book thinks about how palaeontology was deeply emmeshed with politics, empire and economics throughout its history. This isn’t just on the level of its material conduct, but still exists on the level of language – hierarchical thinking, ideas of progress, or notions of particular animal groups having ‘dominance.’ These are concepts which are rooted in nineteenth-century understandings and ideologies, and are deep in the history of the field. By thinking about how these ideas became rooted, we can start thinking about going beyond them.

As a critical history, the new historiography of paleontology provides the knowledge necessary “to break up and dissolve a part of the past” (Nietzsche 1990, p. 75), which legacy is seen as disserving the present paleontological community and its work.

The main benefit of this critical historiography is to present paleontology as a significant player in the way societies think about, talk about, and act upon the world around them. It reminds readers that the history of paleontology is not something unfolding parallel to the rest of history, or with occasional connections to it, but is actually embedded in it. This way of thinking about the history of paleontology makes members of the paleontological community, past and present, historical actors whose collective actions have been having implications for the world around them. It brings to light the social relevance and responsibility of the paleontological community and its individual members. It shows, through historical case studies, that how and why paleontological work is being conducted affects the world around beyond the intended uses of the knowledge thereby produced. Such an historical perspective could help upcoming members of the paleontological community cultivate an always more acute sense of the social and cultural implications of their work and that of their predecessors.