Introduction

COVID-19 disrupted all aspects of society, including civil society, where the crisis prompted people to mobilize through their social networks and form online communities on social media to provide for the needs created by the pandemic and lockdowns (Reference Bertogg and KoosBertogg & Koos, 2021; Reference Carlsen, Toubøl and BrinckerCarlsen et al., 2021; Reference Höltmann, Hutter and SpechtHöltmann et al., 2023; Reference Levine, Park, Adhikari, Alejandria, Bradlow, Lopez-Portillo and HellerLevine et al., 2023). The ability of crises to mobilize individuals for crisis-related voluntary action has been widely observed in the context of different crises (Reference Carius, Graw and SchultzCarius et al., 2024). For instance, during the arrival of Syrian refugees in Europe in 2015 (Reference Agustín and JørgensenAgustín & Jørgensen, 2018; Reference Gundelach and ToubølGundelach & Toubøl, 2019), the arrival of Ukrainian refugees in 2022 (Reference Bang Carlsen, Gårdhus and ToubølBang Carlsen et al., 2024), and in response to natural disasters (Reference AldrichAldrich, 2012; Reference MichelMichel, 2007).

While much research has examined how crises mobilize voluntary action by highlighting urgent needs that state institutions cannot immediately address – prompting civil society to step in (Reference AldrichAldrich, 2012; Reference Miao, Schwarz and SchwarzMiao et al., 2021; Reference Toubøl, Carlsen, Nielsen and BrinckerToubøl et al., 2022)—less attention has been given to their impact on ongoing volunteering, whether through formal organizations or informal networks. Lockdown measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 primarily restricted physical gatherings, and as a result, many voluntary organizations had to adjust their operations to comply with lockdown guidelines (Statens Serum Institut, 2021). Furthermore, as resources and public attention were redirected toward addressing the immediate consequences of the pandemic, voluntary initiatives unrelated to COVID-19 may have faced additional strain (Reference Brechenmacher, Carothers and YoungsBrechenmacher et al., 2020; Reference Lebenbaum, de Oliveira, McKiernan, Gagnon and LaporteLebenbaum et al., 2024).

Expectedly, the limited research in this area shows a decline in levels of volunteering in various countries during COVID-19 (Reference DederichsDederichs, 2023; Reference Grant, French, Bolic and HammondGrant et al., 2024; Reference ZhuZhu, 2022). However, we suspect that this decline may differ across various areas of civil society and demographic groups, as illustrated in studies of the impact of COVID-19 on NPOs (Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023a, Reference Plaisance2023b). Declining levels of volunteering likely varied depending on different areas’ political resources, that is, their ability to influence political decision-making, particularly regarding the re-opening of society. Additionally, differences in how various areas of civil society were able to comply with lockdown restrictions may have further shaped the extent to which volunteering was disrupted or sustained during the pandemic. While many factors influence individuals' volunteer participation, differences in structural barriers to volunteering during this period may help explain variations in volunteering participation between demographic groups (Reference Southby, South and BagnallSouthby et al., 2019). Based on this, we seek to understand how differences in organizational settings and political resources between various areas of civil society, and differences in barriers to volunteering between demographic groups, explain uneven patterns of decline in volunteering during COVID-19.

To examine this, we compare civic participation in volunteering unrelated to the pandemic. Here, we draw on a broad definition of volunteering, encompassing formal volunteering in organizations and informal volunteering within informal networks. Further, we draw on cross-sectional and panel survey data from Denmark measuring volunteer participation before and several times during the first year of the pandemic.

Our paper offers a nuanced understanding of volunteer participation during the pandemic by examining differences across various volunteer areas and demographic groups. In doing so, we contribute to the literature by highlighting an overlooked factor that may have moderated the disruptive influence of the COVID-19 pandemic: the varying political resources within different areas. These resources are important because areas with many political resources could affect the design of state-imposed restrictions on social activity during COVID-19 in ways that benefit themselves.

Background: The COVID-19 Crisis in Denmark

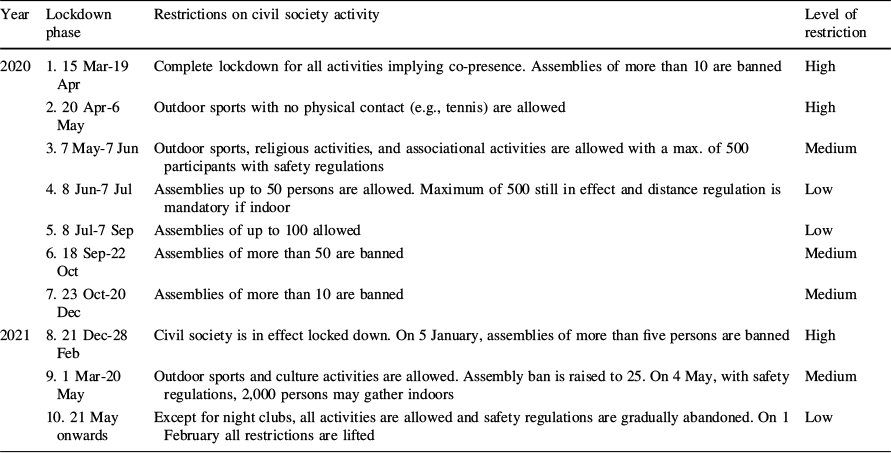

In this section, we introduce the case of COVID-19 in Denmark, focusing on the imposed restrictions implemented, and their relevance for civil society. Table 1 summarizes the lockdowns in Denmark in 10 phases, focusing on the restrictions’ implications for civil society.

Table 1 Restrictions on civil society activities in denmark. Source:'Tidslinje for Covid-19’ (Time line of COVID-19), Statens Serum Institut (2021)

Year |

Lockdown phase |

Restrictions on civil society activity |

Level of restriction |

|---|---|---|---|

2020 |

1. 15 Mar-19 Apr |

Complete lockdown for all activities implying co-presence. Assemblies of more than 10 are banned |

High |

2. 20 Apr-6 May |

Outdoor sports with no physical contact (e.g., tennis) are allowed |

High |

|

3. 7 May-7 Jun |

Outdoor sports, religious activities, and associational activities are allowed with a max. of 500 participants with safety regulations |

Medium |

|

4. 8 Jun-7 Jul |

Assemblies up to 50 persons are allowed. Maximum of 500 still in effect and distance regulation is mandatory if indoor |

Low |

|

5. 8 Jul-7 Sep |

Assemblies of up to 100 allowed |

Low |

|

6. 18 Sep-22 Oct |

Assemblies of more than 50 are banned |

Medium |

|

7. 23 Oct-20 Dec |

Assemblies of more than 10 are banned |

Medium |

|

2021 |

8. 21 Dec-28 Feb |

Civil society is in effect locked down. On 5 January, assemblies of more than five persons are banned |

High |

9. 1 Mar-20 May |

Outdoor sports and culture activities are allowed. Assembly ban is raised to 25. On 4 May, with safety regulations, 2,000 persons may gather indoors |

Medium |

|

10. 21 May onwards |

Except for night clubs, all activities are allowed and safety regulations are gradually abandoned. On 1 February all restrictions are lifted |

Low |

On March 15, 2020, the Danish government imposed a comprehensive lockdown that stopped almost all of civil society's physical activities (phases 1–2). These restrictions were gradually eased during the spring of 2020, allowing most civil society activities to resume (phases 3–5). However, during the fall, the disease started spreading, and restrictions were gradually reintroduced (phases 6–7). In winter 2020, an almost complete restrictive lockdown was enforced again to contain the disease (phase 8), and by spring 2021, these restrictions were once again gradually lifted (phases 9–10).

Restrictions during the pandemic largely targeted assemblies and especially indoor activities, severely limiting possibilities for physical co-presence. As a result, volunteering that could be conducted outdoors, online, or in small groups with distance between participation was favored, while activities requiring larger in-person gatherings and taking place inside faced the most prolonged disruption.

The varying levels of restrictions during the different phases of the lockdowns provide essential context for understanding the pandemic's impact on civil society. Consequently, we consider these developments as we lay out our theoretical framework in the following section.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

In this section, we review research on the role of organizational settings and political resources in shaping an organization's ability to adapt to and influence public policies that affect it. We also review research on differences in structural barriers to volunteering during COVID-19 between different demographic groups to form hypotheses about unequal declines in volunteering during the pandemic.

Variations between Different Areas of Civil Society

In conceptualizing how lockdown periods disrupted different areas of civil society, we distinguish between six areas based on the activities taking place: (1) Sports, (2) Religion, (3) Welfare and health, (4) Culture and leisure, (5) Politics, and (6) Education. This distinction is based on the international classification of non-profit organizations (Reference Salamon and AnheierSalamon & Anheier, 1996). We use this classification scheme because it aligns with the distinction used in a repeated Danish survey of volunteering, allowing for comparison with volunteering in Denmark in the years prior to the pandemic (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021).

Similarly to Plaisance (Reference Plaisance2023a), we examine the role of structural characteristics in explaining differences between different areas of civil society. Specifically, we focus on organizational settings and political resources. Organizational settings pertain to an area's capacity to comply with lockdown restrictions, depending on factors such as the nature of its activities, regulatory framework, and organizational hierarchy. Political resources refer to an area's ability to influence lockdown regulations through access to the political system, allowing it to shape policies in ways that benefit its activities. This definition draws on broader scholarship on political capital, which more generally refers to civil society organizations’ access to the political system and political decision-making processes (Reference Xu and NgaiXu & Ngai, 2011).

Organizational Settings

The ability of organizations to adapt to changing policies and carry out activities while adhering to lockdown rules is a key component for volunteer participation within different areas of civil society during the pandemic. Research has shown that an area's capacity to comply with pandemic restrictions played a crucial role in determining its level of survival and disruption (Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023a). During the pandemic, factors such as the ability to comply with social distancing and conduct activities outdoors, and the degree of formalization within volunteer activities are key components.

During the pandemic, restrictions on activities requiring physical co-presence were stricter compared to activities that could take place either outside or online, possibly helping to explain differences in participation across areas of civil society, because of variation in their ability to shift formats. At one end of the spectrum, many sports activities were able to continue as they often could take place outdoors, allowing for better compliance with social distancing rules. Similarly, the area of education was likely able to shift its activities to online formats, enabling continued participation despite lockdown restrictions. At the other end of the spectrum, the areas of welfare and health rely heavily on in-person interactions in settings such as social cafés, shelters, and clinics (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021). Similarly, culture and leisure activities largely depend on large indoor gatherings, such as concerts, theater performances, and community events, which are not easily moved outdoors, especially in colder conditions.

Formalization refers to the extent to which volunteer activities are structured, with designated individuals responsible for compliance with regulations. Formalization is relevant in the context of broader trends during the pandemic, where formal volunteering declined, while informal volunteering increased (Reference Grant, French, Bolic and HammondGrant et al., 2024; Høgenhaven, 2025). While sports can be organized in informal settings where responsibility for compliance with restrictions is less clear, welfare and health volunteering is more formalized, as it increasingly supplements publicly funded health and social services in Denmark (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021). This creates a structured setting in which individuals are accountable for managing activities and ensuring adherence to regulations. Consequently, strict lockdown measures likely disrupted volunteer participation heavily in this area.

Political Resources

Political resources are another key factor that differs across areas, creating differences in the influence on how COVID-19 restrictions were designed and lifted. When examining political resources, it is important to account for cross-national differences in the status and influence of civil society areas. Evidence from France suggests that sports, culture, and leisure were particularly negatively affected by the pandemic (Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023b). In Denmark, however, we expect a different pattern, as sports holds significant political resources. This underscores the need to consider political resources, since the ability to shift activities outdoors alone cannot explain the differences, as sports in France likely also had this option.

In Denmark, sports is the largest field of volunteering, with 12 percent of the population participating in 2020, which is twice the share of politics, the second-largest area (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021; Reference Ibsen and SeippelIbsen & Seippel, 2010). Sports is an area with influential national interest organizations (Reference Selle, Strømsnes, Svedberg, Ibsen, Henriksen, Henriksen, Strømsnes and SvedbergSelle et al., 2019), enabling it to negotiate restrictions in ways that benefit its activities. Consequently, restrictions to sports were lifted earlier than in many other areas, with arguments emphasizing the importance of sports for physical and mental well-being (see also the timeline in Table 1).

Taken together with the outdoor nature of many sports activities and their less formalized organizational settings, we hypothesize that the decline in volunteering in sports during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions was smaller compared to other areas (H1a), and that there was a significant increase in sports volunteering when restrictions were eased, due to the area's influence and adaptability (H1b).

Like sports, religion is another area that holds a privileged political position in Denmark. The Evangelical-Lutheran Church is a state church with close ties to the political system, and freedom of religion is a constitutionally protected right. Consequently, churches and religious congregations were allowed to maintain services, meetings, and cultural activities to a greater extent than other areas, despite many of these activities taking place indoors.

For these reasons, we hypothesize that there was no significant decline in volunteering in religion during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions (H2a), and no significant increase when restrictions were eased, as religious activities were not heavily restricted (H2b).

The area of culture and leisure do not possess the same political influence to negotiate favorable conditions or early reopening. As a result, restrictions in this area remained in place longer, even after general lockdown measures were eased. Given this prolonged disruption and dependence on indoor settings, we hypothesize that the decline in volunteering in culture and leisure during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions was high (H3a), and that there was no significant increase in volunteering in this area when restrictions were eased, due to prolonged limitations (H3b).

The areas of welfare and health lacked political influence to be part of the crisis response and were largely shut down in favor of government-employed workers. Unlike other countries, Denmark's rollout of COVID-19 testing and vaccination programs relied primarily on paid workers, particularly young people and retired health professionals, rather than volunteers (Reference WesthWesth, 2021). As a result, testing and vaccination programs did not drive an increased demand for volunteers nor create the necessary political resources to influence restrictions during lockdown.

Together with the reliance of in-person interaction, we hypothesize that the decline in volunteering in welfare and health during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions was high (H4a), and that there was no significant increase in volunteering in this area when restrictions were eased (H4b).

Finally, we do not propose specific hypotheses for politics and education, as the political influence of these areas is uncertain and it remains unclear to what extent they fully transitioned to or sustained online engagement during the pandemic, despite notable cases of digital civic participation (Reference GrubbGrubb, 2022).

Structural Barriers to Volunteering across Demographic groups

In Denmark, gender plays a significant role in shaping patterns of volunteering. Women are more likely to engage in welfare and health-related volunteering, whereas men more frequently participate in sports-related activities. These gendered patterns reflect broader societal norms and divisions of labor, where women's volunteer work often aligns with unpaid domestic and caregiving responsibilities, while men's participation tends to be linked to recreational and organizational activities (Reference Boje, Hermansen, Møberg, Henriksen, Strømsnes and SvedbergBoje et al., 2019).

Aligning with these broader gender patterns, research in Denmark shows that women took on the majority of informal care work during the pandemic (Reference Andersen, Toubøl, Kirkegaard and CarlsenAndersen et al., 2022). The closure of childcare institutions and schools during lockdowns increased domestic workloads for both parents but disproportionately for women (Reference Jessen, Spiess, Waights and WrohlichJessen et al., 2022; Reference Sevilla and SmithSevilla & Smith, 2020). These added responsibilities likely constrained their time for volunteering, as time pressures are known to limit volunteering opportunities (Reference QvistQvist, 2024). Furthermore, the restrictions greatly impacted parents who had to manage childcare and homeschooling during lockdown periods.

Considering these dynamics, we hypothesize that women experienced a greater decline in volunteering during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions than men (H5a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H5b). We also hypothesize that individuals with families experienced a greater decline in volunteering during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions than singles (H6a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H6b).

Age is another factor that shapes people's opportunities to volunteer. Typically, the relationship between age and volunteering follows an inverse U-shaped pattern, with participation increasing from youth into middle age before declining in older age. This trend is also evident in Denmark, where middle-aged volunteers constitute most of the volunteer force (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021). Younger individuals may have fewer opportunities or less stability to engage in volunteering due to educational and career commitments, while older individuals may face health-related limitations or reduced engagement opportunities (Reference Southby, South and BagnallSouthby et al., 2019).

Existing research on volunteering during COVID-19 suggests that volunteer participation declined most among older volunteers aged 65 or more (Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023b). Importantly, older individuals faced a higher risk of severe illness, leading to official recommendations for them to self-isolate.

Considering the above insights about age, we hypothesize that older individuals (aged 60 and above) experienced a greater decline in volunteering during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions than younger individuals (H7a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H7b).

Health risks during COVID-19 extended beyond older populations, as individuals with pre-existing conditions, particularly respiratory diseases, were classified as high-risk and may have been discouraged from volunteering in physically co-present settings (Statens Serum Institut, 2021). Against this backdrop, we hypothesize that individuals with poor health experienced a greater decline in volunteering during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions than those with better health (H8a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H8b). Moreover, we hypothesize that individuals in the COVID-19 risk group experienced a greater decline in volunteering during periods when COVID-19 restriction levels were higher than among those outside of the risk group (H9a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H9b).

The final sociodemographic factor we consider is education, which is also known to influence volunteer participation. Higher levels of education are typically associated with greater involvement in volunteering, as they provide individuals with resources such as skills, knowledge, and social capital that facilitate engagement in civil society (Reference EimhjellenEimhjellen, 2023). During the pandemic, evidence similarly indicates that individuals with higher education levels were more likely to volunteer than those with lower levels of education (Reference DederichsDederichs, 2023). For these reasons, we hypothesize that individuals with higher education experienced a smaller decline in volunteering during periods of high COVID-19 restrictions than those with lower education levels (H10a), and a smaller increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased (H10b).

Data and Methods

The data consists of cross-sectional and panel survey data collected during the first year of the pandemic in Denmark, which contain a wide range of items asking respondents about their volunteer activity both prior to and during the pandemic. The survey department at Statistics Denmark (DST) distributed the surveys online via Danish mandatory online post boxes to random samples of Danish adults (16–99), selected from the Danish CPR registers to ensure representativeness.

The cross-sectional survey data were collected in the spring of 2020 (n 2020 = 3,497) and 2021 (n 2021 = 1,692). Subsequent analysis of the samples’ representativeness shows that women, older individuals, and individuals with higher levels of education are overrepresented among those who responded to the surveys. To account for this, we use survey weights based on information about the full population provided by DST.

The panel data were collected in short intervals during the first year of the pandemic in April 2020, May 2020, June 2020, and April 2021, and the panel is based on the first cross-section. Thus, the first panel and the first cross section are the same, but due to attrition, the panel consists of 1,340 Danes who responded to all four panel rounds. Among respondents who participated in all four rounds, older adults are especially overrepresented, and the panel is therefore weighted based on data on the full population. For a summary statistics Table of the two cross-sections and the panel, see Table A.1 (Online Appendix A).

Measures

In the cross-sectional data, volunteering measures if the respondent participated in volunteer work within the past 12 months. This captures their volunteer activity in the year preceding COVID-19 in the first cross-section (April 2019-April 2020) and during the first year of the pandemic in the second cross-section (April 2020-April 2021). This is a broad measure of volunteering, encompassing both one-time and recurrent volunteer activities, as well as formal and informal ones. In panel rounds 2, 3, and 4, volunteering measures respondents’ volunteer engagement within the 3 weeks prior to the time of filling out the survey. Since the panel is based on the first cross section, the first panel round measures volunteering in the year prior to the pandemic and is used as a base line in the analyses of the panel data.

After indicating their participation in volunteering, respondents are asked to specify in what areas they have volunteered, aligning with the conceptual framework: (1) Sports, (2) Religion, (3) Welfare and health, (4) Culture and leisure, (5) Politics, and (6) Education. Respondents are able to volunteer in more than one area, which we account for in the analysis.

The analysis includes several demographic variables such as sex used as a proxy for gender and divided into the categories male and female based on the Danish CPR registers, children (yes, or no), age coded into three categories corresponding to different life phases: (1) Young: 16–29, (2) Middle-aged: 30–59, and (3) Old: 60 + . We further include two health variables: self-evaluated health (coded as good or poor) and perceived risk of COVID-19 infection (coded as at risk or not at risk). We choose binary measures to ensure enough observations in each category in order to compare levels of volunteering. Finally, education is categorized into primary school, higher secondary/vocational education, medium higher education, and long higher education based on Danish register data (Full questionnaire is available in Online Appendix A.2).

Analytical Strategy

We deploy a two-fold analytical strategy. First, we conduct descriptive analyses to compare volunteer participation rates before and during the first year of COVID-19 based on the cross-sectional data. To test hypotheses H1a through H10a concerning differences between areas of civil society and demographic groups, we use mean difference tests comparing the share of volunteers in each area and demographic before the pandemic and during its first year and assess relative drops in volunteering and test for significant differences using interaction terms in logistic regressions (Online Appendix A.3).

The second part of the analysis is based on the four-round panel and tests the correlations between changes to the level of lockdown and individual movements in and out of volunteering to test hypotheses H1b through H10b. To capture the different levels of lockdown, we use the period variable based on the panel rounds. Corresponding with Table 1, Period 1 covers the 12 months before COVID-19 (our baseline period), with no restrictions. Period 2 represents a three-week period of complete lockdown, Period 3 represents a three-week period of low restrictions, and Period 4 represents a three-week period of high/medium restrictions. We use logistic fixed effect models to test if changes in the strictness of lockdown correlate with changes in volunteer participation within individuals. We repeat the logistic fixed effect models on different areas and demographic groups and use average marginal effects to compare the models and test the hypotheses regarding differences between different areas and demographic groups.

Results

Differences Between Areas of Civil Society

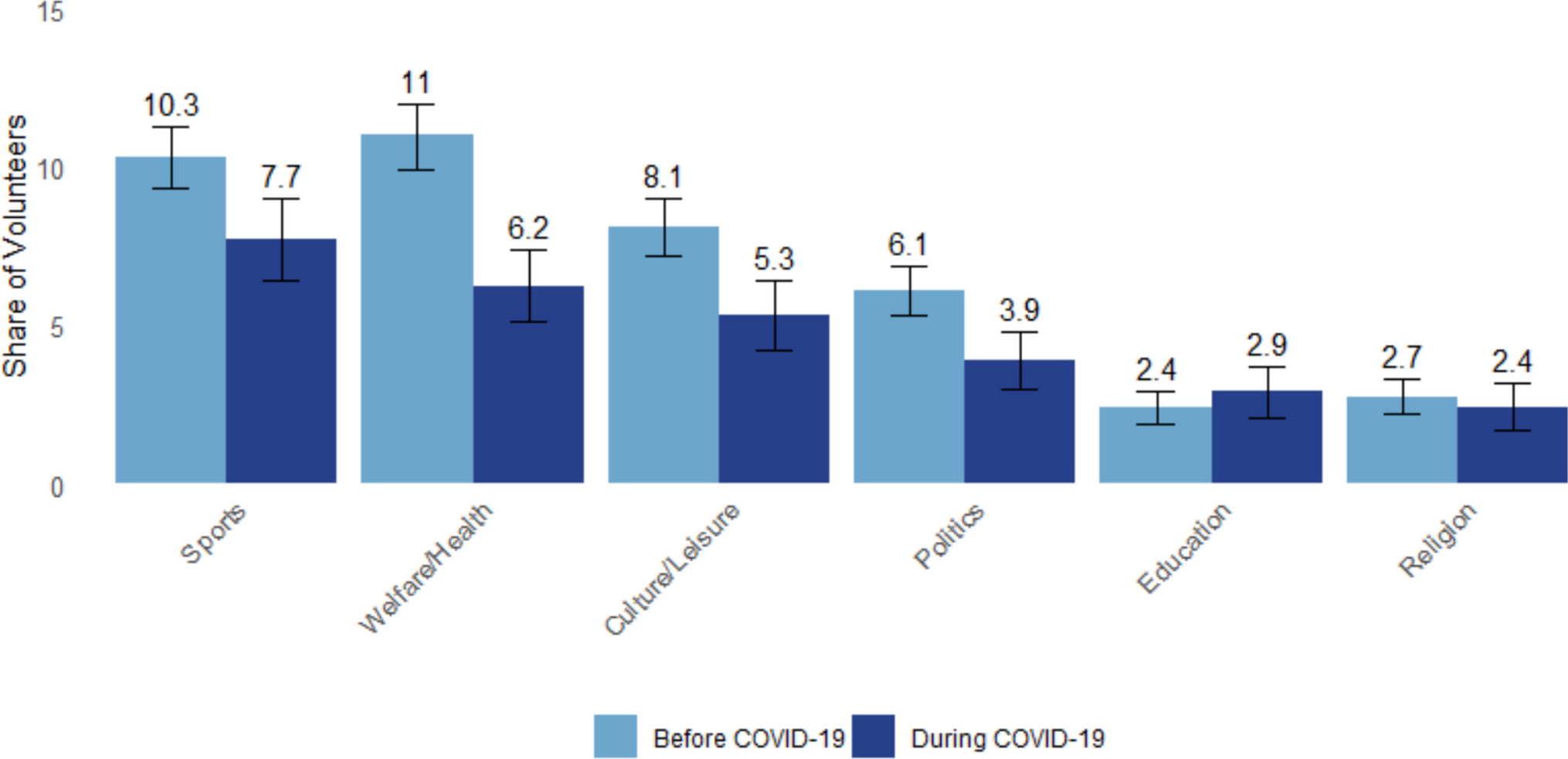

Across all areas of civil society, the total share of volunteers declines from 29 percent in the year before the pandemic to 23 percent during its first year, indicating a substantial disruption of volunteer participation (Online Appendix A.3). Looking at differences between areas, Fig. 1 illustrates the shares of volunteers in each of the six areas and shows that with the exception of education and religion, all areas experience a significant decline in the shares of volunteers during the first year of the pandemic.

Fig. 1 Share of volunteers in different areas of civil society before and during COVID-19. n2020 = 3,497 and n2021 = 1,692. Data is weighted based on the full population. See Table A.3 for relative drops and significance tests (Online Appendix A)

Figure 1 shows that the area of sports did not avoid a significant decline despite its political resources ensuring an advantaged position with fewer restrictions. On the contrary, the area witnesses a significant drop in volunteers of 25 percent, comparable in relative terms to the declines seen in other areas rejecting H1. The area of religion appears to experience only a small (11 percent) decrease in volunteers, which is not statistically significant, supporting H2 and the expectation of a small or no decline. However, the relative drop in volunteers is only statistically smaller than that of welfare and health.

Furthermore, the area of welfare and health experiences a substantial and statistically significant decline of 44 percent. Likewise, the area of culture and leisure also experiences a significant and large decline of 35 percent. This supports the idea that areas lacking the political resources to influence conditions in their favor experience significant disruption to volunteer participation during the pandemic lending support to hypothesis H3 and H4. However, the relative drops are not significantly different from that of other areas, except for a significant difference between welfare and health and religion.

We did not formulate specific hypotheses for politics and education. But exploratory results show that politics experiences a significant decline of 36 percent in volunteer participation, while education is the only area that significantly differs from the other areas, and appears to see an increase of 21 percent, although this increase is not statistically significant. One possible explanation is that the organizational settings within education facilitate a smoother transition from in-person activities to online formats.

In summary, with the exception of sports, declines in volunteering within each area followed expectations. Further, the overall pattern of decline was similar across areas, except for a significantly smaller decline in education as well as a significant difference between welfare and health and religion.

Differences between Demographic Groups

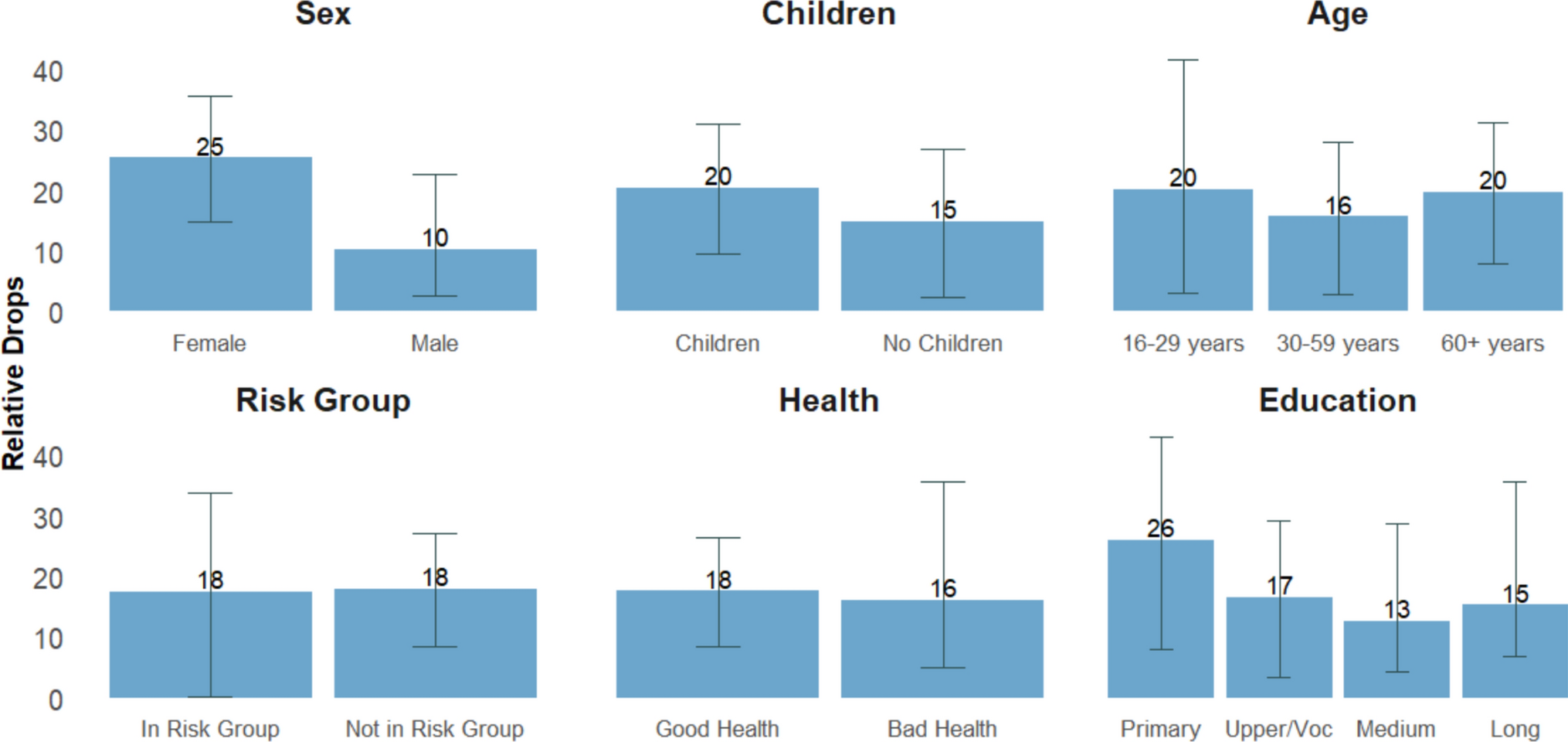

To test H5a through H10a about differences between demographic groups, Fig. 2 compares the relative drops in shares of volunteers for the different demographic groups.

Fig. 2 Relative drops in volunteering among different demographic groups from before and into the COVID-19 pandemic including .95 confidence intervals. Data is weighted based on the full population. The bars illustrate the relative drops in volunteering for each demographic based on the shares of volunteers before and during the pandemic. Confidence intervals are calculated based on the method described in Kohavi et al. (Reference Kohavi, Longbotham, Sommerfield and Henne2009). See Table A.3 for shares in each cross section and TableA.4 for significance tests (Online Appendix A)

Figure 2 shows larger drops in the shares of volunteers among women, people with children, and those with a primary school education. Still, there are no significant differences in the drops across demographic groups. The results, therefore, offer no support for our hypotheses that declines in volunteering are more pronounced for some demographic groups than others. However, during the pandemic, the differences in the share of volunteers between demographic groups mirror those prior to the pandemic, meaning that the pandemic does not significantly shift the distribution of volunteers (Online Appendix A.3).

As presented in the conceptual framework, levels of lockdown vary greatly in the first year of the pandemic, and we therefore turn to examine variations in volunteering during shifting levels of restriction.

Variations in Participation Between Areas during the First Year of the Pandemic

In this section, we use panel data to examine how changing pandemic restrictions correlate with individual movements in and out of volunteering. When looking across all areas and demographic groups, many volunteers drop out of volunteering between Period 1 (pre-pandemic) and Period 2 (first lockdown with high restrictions). However, in Period 3, when restrictions are low, volunteer persistence and recruitment increase, and dropout rates decline. In Period 4, levels of volunteering drop again as restrictions are high (Online Appendix B.1). A fixed-effects analysis confirms that individuals are significantly more likely to volunteer during periods of low restrictions, highlighting the responsiveness of volunteer participation to shifts in restrictions (Online Appendix B.2).

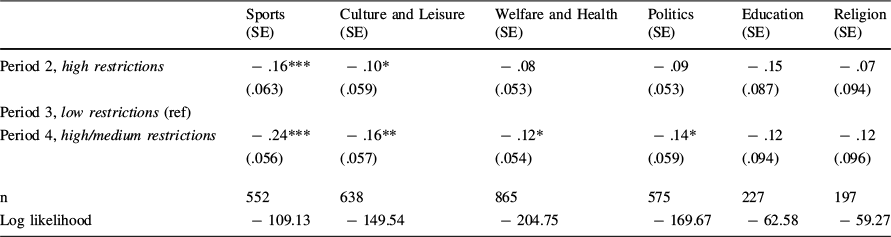

To test H1b-H4b about differences between areas, we run the same logistic fixed-effects model on subsets based on individuals who have volunteered within each area in at least one panel round (For raw numbers, see Online Appendix B.3). This means that some individuals are present in more than one subset.

Table 2 presents the results of the logistic fixed-effect models and shows largely similar patterns across all areas except for sports. These results thus support H1b, as sports showed a significant increase in volunteering when restrictions were eased. They also provide partial support for H2b, given that no significant increase was observed in religion; however, this may be attributed to the small sample size and limited statistical power. In contrast, H3b and H4b are rejected, as both culture and leisure, and welfare and health, showed significant increases in volunteering during periods of fewer restrictions. In sports, changes in volunteering behavior across periods are more pronounced than in other areas. Compared to Period 3, which had low restrictions, individuals were 16 percent more likely to volunteer in this area during Period 2 and 24 percent more likely to volunteer in Period 4. This result supports the idea that sports were influenced more by variation in restrictions due to its organizational setting, with many outdoor activities that are only prohibited during periods with high restriction levels. The area also seems to benefit from its political resources, potentially shaping the design of low-restriction periods to suit its own interests. However, the findings do indicate that sports were just as affected by high restriction levels as other areas, suggesting that their ability to leverage political resources are primarily focused on influencing the reopening rather than mitigating the initial impact of restrictions.

Table 2 Logistic fixed effect model. coefficient reported as average marginal effects

Sports (SE) |

Culture and Leisure (SE) |

Welfare and Health (SE) |

Politics (SE) |

Education (SE) |

Religion (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Period 2, high restrictions |

− .16*** (.063) |

− .10* (.059) |

− .08 (.053) |

− .09 (.053) |

− .15 (.087) |

− .07 (.094) |

Period 3, low restrictions (ref) |

||||||

Period 4, high/medium restrictions |

− .24*** (.056) |

− .16** (.057) |

− .12* (.054) |

− .14* (.059) |

− .12 (.094) |

− .12 (.096) |

n Log likelihood |

552 − 109.13 |

638 − 149.54 |

865 − 204.75 |

575 − 169.67 |

227 − 62.58 |

197 − 59.27 |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Period 3 with low levels of restrictions is chosen as the reference category to ease interpretation

Variations in Participation Between Demographic Groups During the First Year of the Pandemic

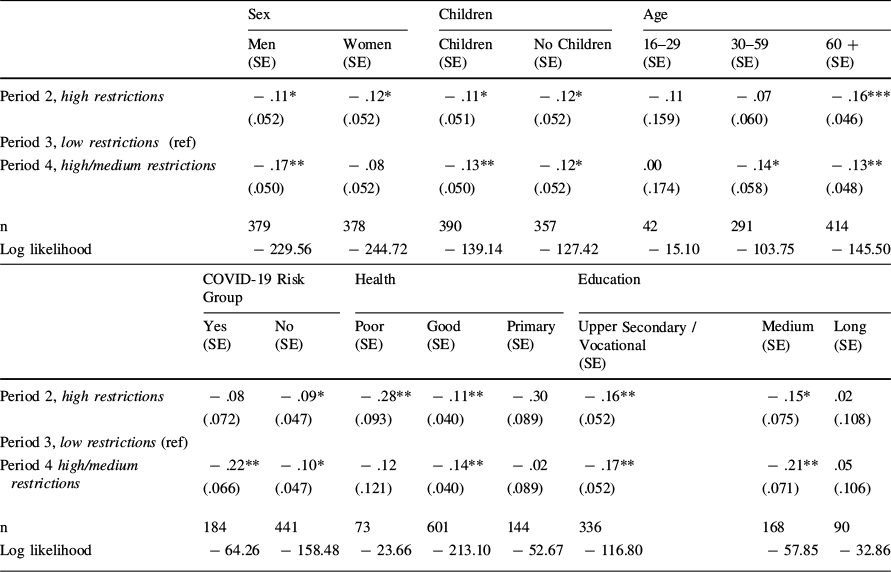

To test H5b-H10b and whether the correlations between restriction levels and individual movements in and out of volunteering differ between demographic groups, Table 3 presents the results of logistic fixed-effects models on subsets of the data according to demographic groups.

Table 3 Logistic fixed effect model on volunteering during periods 2–4 on subset of demographic groups. coefficients reported as average marginal effects

Sex |

Children |

Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Men (SE) |

Women (SE) |

Children (SE) |

No Children (SE) |

16–29 (SE) |

30–59 (SE) |

60 + (SE) |

|

Period 2, high restrictions |

− .11* (.052) |

− .12* (.052) |

− .11* (.051) |

− .12* (.052) |

− .11 (.159) |

− .07 (.060) |

− .16*** (.046) |

Period 3, low restrictions (ref) |

|||||||

Period 4, high/medium restrictions |

− .17** (.050) |

− .08 (.052) |

− .13** (.050) |

− .12* (.052) |

.00 (.174) |

− .14* (.058) |

− .13** (.048) |

n Log likelihood |

379 − 229.56 |

378 − 244.72 |

390 − 139.14 |

357 − 127.42 |

42 − 15.10 |

291 − 103.75 |

414 − 145.50 |

COVID-19 Risk Group |

Health |

Education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yes (SE) |

No (SE) |

Poor (SE) |

Good (SE) |

Primary (SE) |

Upper Secondary / Vocational (SE) |

Medium (SE) |

Long (SE) |

|

Period 2, high restrictions |

− .08 (.072) |

− .09* (.047) |

− .28** (.093) |

− .11** (.040) |

− .30 (.089) |

− .16** (.052) |

− .15* (.075) |

.02 (.108) |

Period 3, low restrictions (ref) |

||||||||

Period 4 high/medium restrictions |

− .22** (.066) |

− .10* (.047) |

− .12 (.121) |

− .14** (.040) |

− .02 (.089) |

− .17** (.052) |

− .21** (.071) |

.05 (.106) |

n Log likelihood |

184 − 64.26 |

441 − 158.48 |

73 − 23.66 |

601 − 213.10 |

144 − 52.67 |

336 − 116.80 |

168 − 57.85 |

90 − 32.86 |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Period 3 with low levels of restrictions is chosen as the reference category to ease interpretation. For raw counts, see Table B.4 (Online Appendix B)

Table 3 shows some variations, and for both men and women, transitioning from high restrictions in Period 2 to low restrictions in Period 3 correlates with an 11 percent increase in the likelihood of individuals starting to volunteer, which rejects H5b stipulating a larger incline among men. However, compared with the raw counts, the results suggest that as the pandemic progresses, the correlation between restriction levels and individual changes in volunteering becomes less pronounced for women than for men. This may indicate that while women's volunteer participation remains consistently lower throughout the pandemic, those who re-enter volunteering during periods of low restrictions are less sensitive to subsequent restriction changes than men (Online Appendix B.4).

The correlations between restriction levels and volunteering are similar for respondents with and without children, with lower restrictions increasing the likelihood of volunteering by 11–13 percent within individuals. This suggests that having children is not a significant barrier to volunteering during the pandemic rejecting H6b. Among age groups, those aged 60 + benefit the most from eased restrictions, with a 13–16 percent higher likelihood of volunteering, supporting H7b. However, no significant correlation exists for the youngest age group, likely due to a small sample size. Regarding health, Table 3 shows that individuals with poor health are more affected by restriction changes, with the likelihood of volunteering dropping by 22 percent from Period 3 to Period 4 among those in the risk group for COVID, compared to 10 percent for those not in the risk group rejecting H8b. Similarly, the likelihood of volunteering declines by 28 percent from Period 3 to Period 2 for those with poor health, compared to 11 percent for those with good health. Because the correlation between volunteering and restriction levels is higher among individuals with poor health, this finding rejects H9b.

Finally, turning to educational groups, the sample sizes among those with a primary education and long higher education are too small. However, the correlation between volunteering and restriction levels appears similar for individuals with upper secondary education and those with medium higher education rejecting H10b.

Discussion and Conclusion

Using cross-sectional and panel survey data from Denmark, our results show that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a sharp decline in non-crisis-related volunteering across civil society. This finding is consistent with other studies (Reference Grant, French, Bolic and HammondGrant et al., 2024; Reference ZhuZhu, 2022) and with the notion that a crisis places additional strain on ongoing volunteering unrelated to the crisis (Reference Brechenmacher, Carothers and YoungsBrechenmacher et al., 2020; Reference Lebenbaum, de Oliveira, McKiernan, Gagnon and LaporteLebenbaum et al., 2024). While we hypothesized stronger variation across areas and demographic groups, the declines were more uniform than anticipated, which challenges assumptions that organizational setting and political resources necessarily buffer volunteer engagement during crises.

We hypothesized that the areas of sports and religion would experience smaller declines compared to the areas of welfare and health and culture and leisure due to differences in their political resources. Religion did appear to experience a smaller decline, consistent with evidence that political resources can be translated into political influence (Reference Selle, Strømsnes, Svedberg, Ibsen, Henriksen, Henriksen, Strømsnes and SvedbergSelle et al., 2019; Reference Xu and NgaiXu & Ngai, 2011). However, similarly to other areas, sports experienced a significant decline during periods of high restrictions. Further, we did not observe any significant differences in the relative decline between areas with different levels of political resources.

However, sports recovered faster than other areas during intermediate periods of lower restrictions, which aligns with the idea that organizational setting and thereby the ability to comply with restrictions during the pandemic allows for a faster recovery (Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023a). By contrast, culture and leisure, with fewer prerequisites for complying with lockdown restrictions, remained constrained by bans on large gatherings and indoor activities.

Taken together, these patterns suggest that political resources and organizational setting matter less for crisis outcomes through insulating activities from disruption, and more by facilitating favorable conditions for resumption (Reference Brechenmacher, Carothers and YoungsBrechenmacher et al., 2020; Reference PlaisancePlaisance, 2023a, Reference Plaisance2023b).

Turning to demographic groups, the lack of significant differences in declining volunteer rates across demographic groups was unexpected, given prior research on differences pertaining to socioeconomic variables like gender, age and education (Reference Southby, South and BagnallDederichs, 2022; Southby et al., 2019). Specifically concerning gender, our results suggest that women's participation in non-crisis volunteering may have declined more than men's, though not significantly, perhaps because women disproportionately shifted into informal care and crisis-related volunteering (Reference Calarco, Meanwell, Anderson and KnopfCalarco et al., 2021; Reference TwiggTwigg, 2020; Reference Andersen, Toubøl, Kirkegaard and CarlsenAndersen et al., 2021). This points to the importance of considering what type of volunteering is being examined.

Following this logic, a possible explanation for the absence of significant variance across age, parental status, health and education might lie in the exclusive focus on volunteering unrelated to the pandemic, which was highly constrained by the restrictions during the pandemic. Volunteering directly in response to COVID-19 was prevalent (Reference Høgenhaven, Boje, Espersen, Fridberg, Henriksen and IbsenHøgenhaven, 2023; Reference Miao, Schwarz and SchwarzHøgenhaven, 2025; Miao et al., 2021; Reference Toubøl, Carlsen, Nielsen and BrinckerToubøl et al., 2022) and incorporating this type of volunteering when examining declines in volunteering might see more differentiated patterns of volunteer participation.

Overall, this underscores the importance of distinguishing between types of volunteering when assessing societal resilience to crises. When focusing only on ongoing volunteering not related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the severity of restrictions during lockdowns and the limited opportunities to continue activities likely left little room for variation in participation across areas and demographic groups, as these restrictions overshadowed other differences.

Implications

The findings underscore the importance of considering how civil society's political resources and government engagement shape its ability to sustain volunteer participation during crises. While civil society demonstrated a strong capacity to mobilize volunteers in response to COVID-19 (Reference Carlsen, Toubøl and BrinckerCarlsen et al., 2021; Reference Toubøl and CarlsenToubøl & Carlsen, 2020) and played a complementary role in supporting marginalized groups alongside the state (Reference Brechenmacher, Carothers and YoungsBrechenmacher et al., 2020), our study reveals that the pandemic broadly disrupted non-crisis-related volunteering.

This highlights the importance of collaboration between civil society and government, not only for immediate crisis response but also for sustaining broader civil society activities unrelated to crisis mobilization. Governments differed in how they engaged civil society during COVID-19 (Reference KövérKövér, 2021), underscoring the need to ensure autonomy and partnership to protect long-term civic participation. Our findings further suggest that beyond differences in government engagement, varying levels of political resources and influence within civil society determine the capacity of different areas to negotiate favorable conditions and recover from crises.

More broadly, these results call for policy attention to the uneven vulnerabilities within civil society and the need to design crisis responses that mitigate disruptions to voluntary activity across all areas, ensuring that civic participation remains robust and inclusive during future emergencies.

Limitations and Future Research

Finally, we touch on three main limitations of the study. First, due to lower response rates among young respondents, we lack data with sufficient statistical power for young people, who it would be particularly interesting to examine in greater depth. Second, our observation period covers only the first year of the pandemic, limiting our ability to assess its long-term consequences. This constraint also prevents us from examining differences in how the pandemic shaped participation patterns over time between different areas. Additionally, the case of Denmark is arguably unique, as the country has a historically stable civil society (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021). Volunteer participation patterns may differ in other countries, and as Kövér (Reference Kövér2021) highlights, cross-national differences in how governments engage with civil society suggest that similar studies in other contexts would be beneficial. Third, the disruption to non-crisis-related volunteering was particularly pronounced during the pandemic. If the goal is to explore civil society's ability to influence governments during crises, future research in different crisis contexts could provide deeper insights into the long-term resilience and political influence of civil society.

Future research should explore the long-term consequences of the pandemic on different areas, as our analysis is limited to the first year and does not extend beyond the pandemic. Additionally, future studies could examine the negotiations between governments and civil society during crises, not only in terms of how civil society complements state efforts and mitigates crisis impacts but also how governments can prioritize long-term civic engagement and create favorable conditions for sustained participation beyond the immediate crisis context.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University. This study was funded by SparNord Fonden and Research Fund Denmark.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available at Figshare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30306406.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflict of interests to disclose.