The administrative burden literature positions the citizen at the center of analysis and seeks to explore the onerous “experience of policy implementation” on citizens (Burden et al. Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2012, 741). Administrative burdens are generally divided into three main categories: learning costs, compliance costs, and psychological costs. Learning costs are the costs associated with the time and effort undertaken to learn about a program or service. Compliance costs are costs associated with gathering the necessary documents (or other forms of information) to prove eligibility and perhaps pay into a program or service. Psychological costs are the emotional and/or mental health impacts of participating in a program or service, such as the social stigma of being involved in an unpopular program (Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd and Moynihan2018, 23).

The administrative burdens literature has evolved from identifying categories of burdens to exploring the origins of burdens (Bullock Reference Bullock2014; Holler et al. Reference Holler, Tarshish and Kaplan2024; Peeters Reference Peeters2020) and how rules and regulations made up of legislation, executive orders, administrative directives, and street-level discretion may make up a “constellation” or “regime” of burdens (Moynihan et al. Reference Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd2022). The literature also demonstrates that burdens can have a “trickle-down” effect from third-party providers who deliver a publicly financed good or service down to clients seeking access (Zuber et al. Reference Zuber, Strach and Pérez-Chiqués2024). Moreover, if the costs are too high, citizens who cannot pay material or nonmaterial costs may be excluded from essential programs or services (Brodkin and Majmindar Reference Brodkin and Majmundar2010). The literature further identifies that administrative burdens, themselves, can be mechanisms that perpetuate inequality (Herd et al. Reference Herd, Hoynes, Michener and Moynihan2023), impacting individuals on the basis of race (Liang Reference Liang2016; Meier Reference Meier2019; Ray et al. Reference Ray, Herd and Moynihan2023) as well as gender, sexual orientation, or other elements of identity (Beardall et al. Reference Beardall, Mueller and Cheng2024; Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Satterfield, Solorzano, Bowen, Hardison-Moody and Williams2021). On a societal level, burdens may also have the potential consequence of undermining public trust in government through both interpretive effects (i.e., negative experiences that incite negative emotional responses) and resource effects (i.e., the experience of failing to access or losing access to programs or services) (Bell et al. Reference Bell, Wright and Oh2024; see Pierson Reference Pierson1993).

The literature has empirically demonstrated the impact of burdens across a range of policy domains including healthcare (Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd and Moynihan2020; Kyle and Frakt Reference Kyle and Frakt2021), taxation (Braunerhjelm et al. Reference Braunerhjelm, Eklund and Thulin2021; Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd, Hoynes, Michener and Moynihan2023; Shybalkina Reference Shybalkina2021), education (Bell and Smith Reference Bell and Smith2021; Gándara et al. Reference Gándara, Acevedo, Cervantes and Quiroz2024), and childcare (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Burns, White, Hampton and Pearlman2020; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Delany and Doyle2023). Additionally, its empirical investigations have slowly extended beyond developed nations to include exploring burdens in low-middle income countries (Heinrich Reference Heinrich2015; Mahangila and Anderson Reference Mahangila and Anderson2017; Peeters and Campos Reference Peeters and Campos2021). Generally, advancements in the literature indicate that burdens have consequences, particularly for groups with limited resources. Furthermore, in their systematic review of the literature, Halling and Baekgaard (Reference Halling and Baekgaard2023) find that beyond the identification of burdens and their consequences, the literature has also moved to identify concepts such as burden tolerance. They suggest that this tolerance might contribute to the construction of burdens and note a potential feedback effect where citizens’ experiences of administrative burdens influence policymakers’ burden tolerance (Halling and Baekgaard Reference Halling and Baekgaard2023, 191).

Administrative burdens may stem from the unintentional failure to consider the effect of policies or a deliberate attempt at “undermin[ing] legislation through administrative means” (Peeters Reference Peeters2020, 568). They are also conceptualized as being shaped by “structural factors that shape individual-level interactions with organizational processes that in turn influence individual-level life course experiences over time” (Beardall et al. Reference Beardall, Mueller and Cheng2024, 88).

However, the literature pays little attention to the ways in which policy trade-offs and disputes between direct target populations may shape administrative burdens as well. This article offers that administrative burdens can also be conceptualized as the consequence of competition between target groups. While the broader macro-level “social construction” (Ingram et al. Reference Ingram, Schneider, Deleon and Sabatier2007; Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993) or “social location” (Beardall et al. Reference Beardall, Mueller and Cheng2024) of target groups can impact the type and/or extent to which they bear administrative burdens, I argue that target populations can also shape administrative burdens for one another. In this way, this article positions citizens as not merely having an experience of policy implementation shaped by government and frontline workers but also as actors with agency who can shape administrative burdens for others. To capture these dynamics, I propose the concept consequent population to identify theoretically and empirically distinct groups that must navigate the consequences of competition within the policy arena, and the concept consequent costs to specify this sub-category of administrative burden.

The article is structured as follows. The first section examines the methodological approach undertaken, combining abductive analysis with inductive insights. The second section advances a conceptual framework for understanding consequent populations and consequent costs. The third section presents a case study examining gamete donation policy and donor-conceived adults, situating administrative burdens within varying regulatory contexts and then focusing specifically on the Canadian case. This section highlights inter-actor dynamics and the strategic deployment of administrative burdens. The final section considers the theoretical implications of the case, discussing how administrative burdens function both as policy instruments and as outcomes of inter-actor competition.

Methods

The findings presented in this paper arise primarily from an abductive synthesis of the administrative burdens literature and case analysis. Abductive analysis is a way of analyzing findings, outside the silos of inductive and deductive reasoning, “recursively moving back and forth between a set of observations and a theoretical generalization” (Tavory and Timmermans Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014, 4; see Timmermans and Tavory Reference Timmermans and Tavory2012; Peirce Reference Peirce1974). Rather than beginning with an existing theory and confirming or rejecting it or beginning with a dataset and no predetermined theoretical framework, this approach prioritizes inference while also encouraging a creative, speculative analytical process (Rinehart Reference Rinehart2021). It is particularly useful for examining “breakdowns when the empirical data differs from what is expected based on current theoretical understanding” (Thompson Reference Thompson2022, 1411; see Reichertz Reference Reichertz and Flick2013).

The empirical focus of this study is Canada, with the period of analysis spanning 1989 to 2023. The starting point corresponds to the establishment of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies (1989), which initiated federal attention to assisted reproduction, including efforts to regulate gamete donation. The period concludes with Quebec’s 2023 legislative reform governing assisted reproductive technologies (ART), including provisions specific to gamete donation, representing the most recent provincial intervention in this policy domain. Situating the case within these years highlights how administrative burdens have developed in response to both federal and provincial interventions.

Extant research on administrative burdens provides a valuable framework for understanding policy implementation costs within this subsystem, however the case dynamics reveal patterns that exceed the framework’s explanatory scope. Specifically, the case highlights inter-actor interactions that necessitate further conceptual refinement to capture the underlying drivers and implications of inter-actor competition as it pertains to administrative burdens. In response, the analysis moved iteratively between the empirical case, drawing on qualitative sources such as legislative committee transcripts and government reports, and the administrative burden literature to develop a refined conceptual account addressing this gap. The findings suggest that administrative burdens can operate as a strategic mechanism, enabling more efficient policy implementation for some target populations over others. Additionally, while administrative burdens can function as barriers that lead to exclusion (Brodkin and Majmundar Reference Brodkin and Majmundar2010), the case suggests that administrative burdens may also act as drivers for mobilization. Consequently, this article integrates a review of the literature with inductive, case-based conceptual insights and abductively derived empirical insights, offering a contribution that is both empirically grounded and theoretically informed.

Conceptualizing consequent populations

Origins of consequent populations and consequent costs

Before defining consequent populations and costs more precisely, it is useful to understand the competitive processes through which they emerge. While administrative burdens can be shaped by ignorance, political aims, and systemic factors, they can also be shaped by multiple target populations competing in a policy subsystem. Competition in the policy arena manifests in diverse ways, shaped by intervening variables such as institutional configurations, elite interest alignment, and access to policymaking venues. These factors influence how and when actors can assert or defend their interests. While the mechanisms of competition may vary, ranging from public-facing advocacy to behind-the-scenes negotiations, they ultimately serve the same function: securing interests within the policymaking process.

Conceptualizing administrative burdens as the consequence of “winning” or “losing” recognizes that target populations are not always actors who experience the impact of burdens in a passive manner but that they can also be groups that have the agency to actively participate in the structuring of costs associated with policy implementation as they work to ensure their interests are represented in policymaking. Competition is shaped both by well-resourced actors who leverage their power to shape perceptions of deservingness and by the cognitive and administrative limits that constrain how information is processed and policies are implemented.

At the meso-level, competing actors strategically frame other groups as undeserving while positioning themselves as legitimate recipients of less burdensome policy implementation. Simultaneously, policymakers, as “behaviorally rational” actors, navigate complex information but are limited by cognitive constraints and heuristics that affect decision-making (Jones Reference Jones2017, 73). At the administrative level, finite financial resources, expertise, and organizational capacity further restrict the information they can process and the policy tools they can deploy (Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd and Moynihan2018, 31). These human and institutional limitations shape, and often facilitate, the strategic shifting of administrative burdens across populations. By centering competition as shaped by both actor power and cognitive-administrative constraints, this framework deepens understanding of how administrative burdens are distributed and sustained.

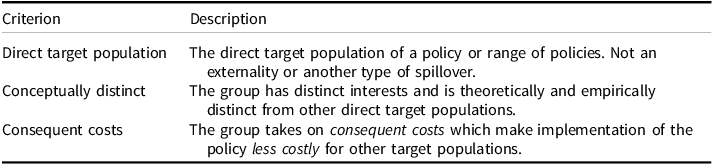

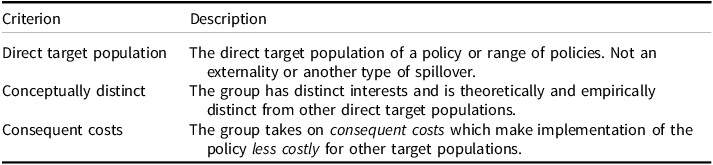

Table 1. Consequent population criteria

Source: Author.

Defining consequent populations and consequent costs

I propose that when a target population experiences administrative burdens in order to make the experience of policy implementation on another target group easier, this is a consequent population. I put forth, consequent populations are direct stakeholders who bear burdens as a result of failing to adequately secure their interests into a policy subsystem. Additionally, consequent costs are the legislative and regulatory costs that enable another target group or range of target groups to experience policy implementation in a less costly manner.

I argue that three specific criteria must be met for a target population to be considered a consequent population (See Table 1). The first criterion is that they must be the direct target of the policy, rather than an indirect beneficiary. The latter would be indicative of a spillover effect, where a decision in one jurisdiction impacts a seemingly unrelated jurisdiction (Baicker Reference Baicker2005; Figueiredo et al. Reference Figueiredo, Lima and Orefice2020; Lakdawala et al. Reference Lakdawala, Moreland and Schaffer2021). Second, the population must be conceptually distinct, with unique interests, and treated as analytically separate even if some members also belong to other groups. Their involvement in the policy process could, theoretically, shift future costs onto other stakeholders or the state. Third, this population takes on unique costs. These costs can include learning, compliance, and psychological costs associated with policy implementation. However, one function of these costs must be to alleviate the burden on other target populations.

Case study: gamete donation policy and donor-conceived adults

This article employs a single illustrative case study to demonstrate the operationalization of the concepts consequent population and consequent costs. The case of gamete donation policy was selected because the governance of ART in Canada can be traced to the establishment of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies in 1989. It is, therefore, possible to construct a detailed timeline of actor competition, legislative and regulatory choices, and the subsequent consequences of policy implementation and to triangulate such findings through cross-referencing multiple sources. This case illustrates that inter-actor competition at the start of a policy subsystem, or as new issues are introduced into the agenda-setting phase, plays a key role in shaping administrative burdens.

Gamete donation itself refers to the transfer of sperm, eggs, or embryos from gamete donors to recipient parents struggling with medical and/or social infertility. In Canada, gametes can be anonymously transferred (anonymous donation), transferred with the promise that the resulting child(ren) may be able to know the identity of their genetic parent(s) at 18 years old (open ID donation) or be transferred by someone known to the intended parent(s) such as a close friend (known or directed donation). Gamete donation is often subsumed under the umbrella of “assisted reproductive technologies” which include a range of medical procedures, pharmaceuticals, and parenting arrangements (Snow Reference Snow2018, 23). Those born through gamete donation are referred to as donor-conceived.

Across jurisdictions, the history of donor conception is one cloaked in secrecy. As Newton et al. (Reference Newton, Drysdale, Zappavigna and Newman2022) explain, “many older donor-conceived adults were conceived during an era in which medical records – if kept at all – were often intentionally inaccurate, modified post hoc or destroyed” (Newton et al. Reference Newton, Drysdale, Zappavigna and Newman2022, 4; see Hewitt Reference Hewitt2002; Dingle Reference Dingle2021). Furthermore, because the recipient parent – typically the mother – was considered the patient (as either the recipient of donor sperm, eggs, or embryos), medical records were seen as belonging to her, requiring donor-conceived people to obtain parental permission to access vital medical history (Dingle Reference Dingle2021).

There is a growing body of literature by scholars and donor-conceived adults themselves, particularly in Western countries, highlighting the consequences of lack of regulation in the fertility industry including frustration with donor anonymity (Beeson et al. Reference Beeson, Jennings and Kramer2011; Baumann, Reference Baumann2021; Guichon et al. Reference Guichon, Giroux and Mitchell2013; Hertz et al. Reference Hertz, Nelson and Kramer2013; Jadva et al. Reference Jadva, Freeman, Kramer and Golobok2010), discontent with and potential dangers of lack of accurate and updated medical history (Adams Reference Adams2012; Ravitsky Reference Ravitsky2012; Newton et al. Reference Newton, Drysdale, Zappavigna and Newman2022), and lack of limits on sibling groups/the number of people created using one person’s gametes (Millbank Reference Millbank2014; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Hertz and Kramer2016; Sánchez-Castelló et al. Reference Sánchez-Castelló, Gonzalvo, Clavero, María López-Regalado, Martínez-Granados, Navas and Castilla2017). Failure to reasonably limit the size of sibling groups could result in psychological discomfort for donor-conceived people and an increased fear of forming consanguineous relationships (Cahn Reference Cahn2009).

The administrative burden of being donor-conceived in jurisdictions with few regulations manifests in several ways. Learning costs, in this context, take several forms. Most fundamental is disclosure: for other costs to be relevant, a donor-conceived person must learn the truth of their origins. There is a robust debate about the ethics of disclosure, with scholars arguing both for (Gruben and Cameron Reference Gruben and Cameron2017; Ravitsky 2010, Reference Ravitsky2014; Symons and Kha Reference Symons and Kha2023) and against it (Leighton Reference Leighton2014; de Melo-Martin Reference de Melo-Martin2014; Pennings Reference Pennings2019). Those in favor emphasize the autonomy of the donor-conceived person, often adopting a deontological stance that centers truth-telling and personal agency: information should be provided, and the individual can then decide how, or whether, to act on it. In contrast, those against disclosure emphasize the donor’s right to privacy and the recipient parents’ authority in shaping a family environment that aligns with their values and provides emotional comfort and security.

Assuming one learns that one was conceived using donor gametes, additional learning costs may be undertaken to try to ascertain what the regulations in a given jurisdiction are and whether access to records (such as the identity of one’s genetic parent or updated medical information) is possible and what information may be necessary to obtain such knowledge (e.g., donor identification number, clinic one’s parents used, or facility where the donation occurred). Compliance costs may be incurred in gathering the necessary documentation to prove one is eligible to access such information. This may also involve paying associated fees. Lastly, psychological costs may arise due to the stress of taking on these administrative burdens while trying to access self-knowledge.

Alternately, it may result from frustration at their motivations for obtaining such information being misunderstood or misconstrued. For instance, in their study exploring the motivations and experiences of donor-conceived adults seeking the identity of their genetic fathers/parent’s sperm donors, Widbom et al. (Reference Widbom, Isaksson, Sydsjo, Svanberg and Lampic2024) report that donor-conceived adults communicated that they sought out such information while balancing various “stakeholder interests” including that of their genetic and legal parents. The donor-conceived adults attempted to balance their self-determination with their actions sometimes being misconstrued as being reflective of negative feelings toward their parents or being indicative of a desire to “replace” their fathers (Widbom et al. Reference Widbom, Isaksson, Sydsjo, Svanberg and Lampic2024, 5).

It is important to note that research on the motivations and experiences of donor-conceived people remains an emerging field, with most empirical work situated in the fields of psychology, sociology, or child development. As a result, much of the literature on donor-conceived individuals focuses on children. For example, in a systematic review of the psychological experiences of donor-conceived individuals, Talbot et al. (Reference Talbot, Hodson, Rose and Bewley2024) found that 52% of the 50 studies they reviewed (n = 4,666 donor-conceived participants) focused on children under the age of 12 (Talbot et al. Reference Talbot, Hodson, Rose and Bewley2024, 1754). The limited body of literature that does exist often presents mixed or conflicting conclusions. In their analysis, Talbot et al. (Reference Talbot, Hodson, Rose and Bewley2024) highlight that inconsistencies across the literature largely manifest in two conflicting narratives: while donor-conceived individuals often report average or above-average levels of well-being and self-esteem, many qualitative studies also highlight that donor-conceived people commonly report a range of negative experiences, “including feeling deceived, struggling with identity formation and lacking support to help them access information about their origins” (Talbot et al. Reference Talbot, Hodson, Rose and Bewley2024, 1754).

Donor-conceived people are one target population of gamete donation governance. Other target groups include recipient parents, gamete donors, and fertility industry professionals. In jurisdictions such as Canada, the governance of this policy subsystem, and the resulting policy implementation, disadvantages donor-conceived people. For instance, the continued allowance of gamete donor anonymity and the absence of limits on the size of sibling groups prioritize the interests of donors and recipient parents, who seek to ensure that the supply of gametes meets demand (Malone Reference Malone2017). Additionally, regulatory frameworks that do not mandate the maintenance of updated records, including medical information, aim to reduce administrative costs for clinics, banks, and government-run services such as registries (Kelly Reference Kelly2017). Consequently, shifting the burden of obtaining such information onto donor-conceived people enables other target groups to more easily access gamete donation services and allows providers to keep costs down (Cattapan et al. Reference Cattapan, Gruben and Cameron2019).

Despite the presence of socialized medicine in Canada and the fact that gamete donors in Canada cannot legally be paid beyond reimbursements for expenses associated with donating, the governance of donor conception reflects American influence, which favors a more laissez-faire approach to fertility care. This is because less regulation enables greater economic choice in the reproductive marketplace both in terms of the financial incentives offered to gamete donors whether legal or “under the table” (Motluk Reference Motluk2020) and the range of identification arrangements available to recipient parents (e.g., anonymous or open-ID options) (Speier Reference Speier2017). However, given the global nature of the reproductive marketplace, it is important to note that more stringent domestic regulations may not alleviate the administrative burden on donor-conceived adults conceived using imported genetic material. For example, a regulation that mandates certain record-keeping practices or limits the number of offspring per donor may apply within one jurisdiction but not in the jurisdiction from which the gametes were exported (Luetkemeyer Reference Luetkemeyer2010; O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Bowen, Perampaladas, Quershi, Xie and Hughes2017).

One major development for this population is the development of direct-to-consumer DNA testing. In jurisdictions such as Canada, where gamete donor anonymity is protected and records only need to be kept for 10 years, accurate medical histories might be a challenge for donor-conceived adults to obtain. Therefore, commercial DNA tests may be used to identify genetic parents and siblings and obtain ancestral and medical information (Darroch and Smith Reference Darroch and Smith2021). The cost of a commercial DNA test such as AncestryDNA or 23andMe are approximately $129 and $200, respectively and this is without additional services and subscriptions offered by the companies for those who want more health information or ongoing subscriptions to other databases (e.g., genealogy services). This consequent cost signals “a significant shift in the arrangements that sustain a power imbalance between donor-conceived people and very powerful institutions and may offer donor-conceived people greater control over their medical and genetic histories” (Newton et al. Reference Newton, Drysdale, Zappavigna and Newman2022, 4). Additionally, they are indicative of a newly established trend in the literature which seeks to explore the role of third-party organizations in managing or reducing administrative burden (Nam and Fay Reference Nam and Fay2024; Rode Reference Rode2024; Tiggelaar and George Reference Tiggelaar and George2023).

Administrative burdens in comparative regulatory contexts

In jurisdictions where regulations and enforcement mechanisms more clearly reflect the interests of donor-conceived people, administrative and psychological costs are often reduced for them and instead redistributed to recipient parents, donors, industry actors, or the state. For instance, Sweden was the first country to prohibit anonymous gamete donation in 1985. While there is no central registry, clinics that facilitate gamete transfers are required to preserve information through a “special medical record.” Donor-conceived individuals can request this record once they reach tillräcklig mognad, or “sufficient maturity,” rather than waiting until the age of majority (Lingren Reference Lingren2024). As a result, they may access identifying information about their genetic parent(s) before turning 18.

In contrast, some countries place the responsibility for record-keeping on existing state agencies rather than clinics. In Switzerland, while egg donation is prohibited, sperm donation is legal, and anonymous donation has been banned since 2001. When donor-conceived individuals reach the age of 18, they can request information from the Eidgenössisches Amt für Zivilstandswesen (EAWZ)/Federal Office for Civil Registration (Federal Office of Public Health 2025). Other jurisdictions have created separate, specialized government-run registries. The United Kingdom established one in 2004. Individuals born after April 2005 can, for a fee of £95, register with the Donor Conceived Register, maintained by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), to obtain updated medical and identifying information about their genetic parent(s). The Register provides two free counseling sessions, with additional sessions available at a cost of £25 (Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust 2017a, 2017b). These services substantially reduce the costs of verifying health information and connecting with genetic relatives compared to jurisdictions without such infrastructure.

Some jurisdictions have transitioned once-established registry responsibilities to other government agencies. In Victoria, Australia, the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA) implemented donor conception registry services beginning in 2010. These services included a free voluntary register that allowed donor-conceived individuals, their relatives (including parents and descendants), and donors (aged 18 and older) to share or access medical information, cultural heritage, and personal items such as photographs, letters, and videos. A separate central register was available for a fee (approximately $85) for those seeking more detailed information not included in the voluntary system. This could include both non-identifying details (e.g., medical history, physical characteristics, birth month and year) and identifying information (e.g., names, donor codes, and contact details). At the end of 2024, VARTA ceased operations. Effective January 1, 2025, regulatory responsibility for assisted reproduction and the management of Victoria’s donor conception registers was transferred to the Victoria Department of Health (Department of Health 2024).

Reforms that provide donor-conceived individuals with the right to access information about their genetic origins signal a redistribution of administrative burdens, from individuals to industry or state institutions. However, legal changes can outpace practical implementation. First, generational divides, where older cohorts were conceived under anonymity regimes, mean many still face insurmountable barriers, as reforms are rarely retroactive. Second, even where laws support transparency, access may be hampered by limited resources, poor frontline implementation, confusion around record-keeping responsibilities, legal ambiguities, and weak enforcement. Third, navigating the bureaucracy can impose high costs, especially when procedures are unclear or vary across regions, as is often the case in jurisdictions with sub-national registries.

The Canadian case, 1989–2023: creating a consequent population

Canada is an outlier with respect to the lack of protections for donor-conceived individuals. In Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, the United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand, parts of Australia, and parts of the United States have amended or updated legislation to reflect the interests of donor-conceived individuals. This is mostly through prohibiting gamete donor anonymity (Blyth and Frith Reference Blyth and Frith2009; Gardner Reference Gardner2023). These changes indicate a shift of burden from donor-conceived adults to other target populations. In Canada, however, this is not so.

In Canada, gamete donation is governed by the Assisted Human Reproduction Act S.C. 2004, c. 2 [AHRA] in accordance with Health Canada regulations. Although the first principle of the AHRA is: “the health and well-being of children born through the application of assisted human reproductive technologies must be given priority in all decisions respecting their use,” this has not happened. The story of this consequent population spans several decades. In practice, the laws and regulations governing gamete donation are not about donor-conceived people but about those seeking to obtain gametes, those seeking to give them away, and the professionals who facilitate these transactions. Regulations concerning the health of sperm and ova, mostly outline donor suitability to ensure immediate safety for recipient parents; reimbursement regulations for donors and surrogates; consent rules concerning when gametes count as “donor material” as well as procedures for withdrawing consent; and rules regarding administration and enforcement.

The lead-up to the AHRA began in 1978 after the first successful birth through in-vitro fertilization (IVF) occurred in the United Kingdom. After a decade of media attention, public speculation on the future of such technologies, and the eventual realization that IVF and other medical advancements would soon become mainstream, Canada launched an investigation into ART. By October 1989, the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies, led by Dr. Patricia Baird, was established. It involved over 300 researchers and gathered opinions from approximately 15,000 Canadians. This event created a policy window that allowed those with expertise, resources, and influence to define issues and set the agenda (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995, 77).

While the Commission outwardly stated its commitment to exploring ART prioritizing “the principles of autonomy equality, respect and dignity, protection of the vulnerable, non-commercialization of reproduction, appropriate application of resources, accountability, and balance between individual and collective interests,” in practice the Commission had a “bio-medical bias” that would privilege the interests of physicians and lawyers who sought to profit from these emerging technologies and, by extension, recipient parents who demanded them (Cattaptan Reference Cattapan2015, 78; Scala Reference Scala2019). Despite some ART activities, such as human cloning and the commercialization of gametes, being prohibited, the Commission’s structure and focus largely favored medical and scientific interests, marginalizing non-quantitative concerns such as dehumanization and exploitation. This bias was evident in its final report, Proceed with Care (1993), which prioritized infertility and medical advancements. For instance, the report dedicated 17 of 31 chapters to discussing infertility and subfertility and how new medical advancements (and adoption) could address them (Cattapan Reference Cattapan2015, 82).

With regard to gamete donation, specifically, the Commission discovered that facilities that practiced donor insemination were not standardized. While clinical practice guidelines had been developed before the formation of the Commission, they were “not followed at all clinics, and even less so in offices” (Baird Reference Baird1995, 493). Additionally, donor sperm that had not been tested for HIV had been used to inseminate patients, resulting in women being infected with the virus. Baird also notes that “medical and social information on the donor is needed and is very important for the child and recipient to have” yet “[t]he Commission found it is not routinely collected; there is great variation in what, if any, information is collected and in how long it is kept. It means there is no assurance of limits on numbers of offspring from one particular donor in a community, or that individuals who are half siblings may not marry” (Baird Reference Baird1995, 494).

The privileging of industry interests during this policy window provided the context for future consultations in which industry interests and the interests of recipient parents would align, forming a closed network that put limits on new actors and ideas being inserted into the policy process (Howlett Reference Howlett2002, 248). It also put limits on how issues and direct target populations could be constructed. Because the emphasis was on how ART could help people who wanted to be parents and relied on the expertise of those who would go on to make up the fertility industry, donor-conceived people were constructed as simply the products of services being provided to recipient parents. This is in opposition to the reality that they are, indeed, an autonomous group with their own interests. Yet, because a closed network was forming, it created a boundary that would make the inclusion of new stakeholders, ideas, and interests difficult – especially if their interests did not align with opposing stakeholders, such as industry or recipient parents. This was the beginning of the process whereby donor-conceived adults were relegated to the position of consequent population.

After the release of Proceed with Care (1993) the federal government crafted legislation to create a framework that comprehensively governed ART in Canada. In 1994, Health Canada began consultations and put a moratorium on certain activities, including those relating to payment for gametes and commercial surrogacy arrangements. However, Health Canada released a report in 1996 indicating that several physicians across the country were not adhering to these new rules (Snow Reference Snow2018, 25; Health Canada 1996a). Around this time, the only meaningful regulations in force were basic Health Canada guidelines outlining things such as laboratory cleanliness standards and infectious disease testing of gamete donors (Health Canada 1996b).

During this time, policymakers began communicating that if the federal government was going to take the lead in the governance of reproductive technologies, the provinces would challenge them. For instance, in 1996, MP Pauline Picard (Bloc Québecois – Drummond) stated:

It goes without saying that setting up a national agency will inevitably result in the establishment of national standards over which the provinces will, of course, have no authority at all. […] I do not know how many times I have read the Constitution Act. According to sections 92(7) and (8) of the act of 1867, and based on the interpretation made by the courts, health and social services should come under the exclusive jurisdiction of Quebec. But this did not prevent the federal government from getting constantly involved, since as early as 1919, and even forcing Quebec to comply with so-called national standards and objectives (HC Oct 23 October 1996).

Yet, the federal government persisted. In the early 2000s, the federal government tasked the Standing Committee on Health, chaired by MP Bonnie Brown (Liberal – Oakville) to manage consultations on legislation that would eventually become the Assisted Human Reproduction Act S.C. 2004, c. 2 [AHRA]. One major issue of contention was gamete donor anonymity. At first, the Committee asserted that gamete donor anonymity was, indeed, harmful and recommended a system of open donation. The Committee recommended, “… that only donors who consent to have identifying information released to offspring should be accepted,” adding that, “where there is a conflict between the privacy rights of a donor and the rights of a resulting child to know its heritage, the rights of the child should prevail” (Standing Committee on Health, 2001).

However, in mid-2002, the Standing Committee on Health added physicians Hedy Fry (Liberal – Vancouver Centre) and Carolynn Bennett (Liberal – Toronto St. Paul’s) as members. Both physicians on the Committee strongly backed gamete donor anonymity because an open system would fail to keep up with the demand of recipient parents (Malone Reference Malone2017, 76). Transcripts from the standing committee consultations shed light on the values and priorities that influenced the development of the AHRA. They reveal not only the formal outcomes of the legislative process but also the contestation over which voices were considered legitimate in shaping policy. Several key themes emerge: persistent opposition to donor anonymity by donor-conceived individuals and their allies; concerns from industry representatives about potential donor shortages; and a mix of genuine curiosity and occasional hardline stances from policymakers.

On the topic of supply and demand, policymakers and practitioners expressed concerns that ending donor anonymity could reduce the availability of gametes; however, empirical evidence supporting or refuting this claim is limited. Where data exist, it is difficult to attribute any shortages solely to the removal of anonymity. Blyth and Frith (Reference Blyth and Frith2008) note that, during this period, shortages were occurring globally even in jurisdictions that maintained donor anonymity. Examining the period following the United Kingdom’s 2005 prohibition of anonymous donation, they find that donor recruitment did not change significantly in the short term and argue that recruitment strategies and clinic practices, rather than anonymity, were the primary determinants of supply (Blythe and Frith Reference Blyth and Frith2008, 82). The number of men recruited as sperm donors in the UK increased by 6% in the year following the policy change, suggesting that concerns about reduced supply may have been overstated (Day Reference Day2007).

In an attempt to secure their interests in this subsystem, donor-conceived individuals and their allies came to rely on a rights-based framework, sometimes comparing the circumstances of donor conception to adoption:

Adoption is based on the best interests of an existing child. But [this bill] fails to sufficiently protect the best interests of children born from ART, and in fact favours those of adults. B.C. has led the way in adoption reform. Children currently being adopted in that province have an unconditional right of access to the names of their biological parents. Under the current bill, donor-conceived children would certainly have fewer rights than B.C. adoptees (Jean Haase, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

We feel in the adoption community that we have a lot to offer with respect to this legislation. If the legislation proceeds as it is now […] you’re discriminating against those conceived through donor conception by not giving them the same rights as adopted persons (Catherine Clute, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

Above all, rights were discussed in a way that clearly underscored the element of competition between donor-conceived individuals and other stakeholders for control of the policy subsystem:

[These discussions are] often presented as a conflict of our rights versus a donor’s rights. I was seeking to present this evidence to say that it needn’t be. We can all have what we want” (Barry Stevens, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

Those who were pro-anonymity also framed the discussion in terms of competing rights:

“[W]e need to be a little bit careful in drafting the legislation, so that we don’t actually use the words of rights, and thus impose a whole lot of changes into our understanding of how families work in the first place (Kathleen Priestman, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

Others, such as physicians and other representatives of the fertility industry made it clear that their interests were aligned with both gamete donors and recipient parents, often stating that the right to privacy and the right to a sufficient supply of gametes outweighed other concerns:

I am certain that if we do not allow anonymity for sperm and egg donors, the pool of donors would be dramatically reduced (Clifford Librach, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

My patients are devastated and enraged that the proposed legislation will prevent them from being able to have children through this currently available technology (Clifford Librach, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

[W]e will be unable to supply our current patient population with high-quality samples from acceptable donors with the additional burden of mandated non-compensation and identity release (Heather Brooks, Standing Committee on Health 2002).

Committee members occupied a range of positions, sometimes asking probing questions, sometimes revealing clear preferences. Notably, MP Hedy Fry pushed back against the framing of donor conception as anonymous, stating that the current framework was not necessarily “anonymous” but, rather, “non-nominal” (Standing Committee on Health 2002):

We identify everything else about them; that’s important for the health and well-being. We just don’t want to know the name […] Let’s protect the human dignity of the donor by ensuring that one thing is kept secret, and that is the name of the person (Hedy Fry, Standing Committee on Health, 2002).

These assertions align with the perspectives of recipient parents, gamete donors, and the fertility industry, who argue that maintaining anonymity reduces the administrative burdens they would otherwise face during policy implementation (Malone Reference Malone2017). The concern seemed to be that ending anonymity would place excessive administrative burdens on these groups. At its core, the implementation of any policy entails some degree of burden. However, this record reveals competing logics about rights, access, and supply, and differing views on which configurations would make policy implementation easier or more difficult for each stakeholder group.

When a draft of the AHRA was advanced in Parliament, a clause protecting gamete donor anonymity had been added to the Bill. Then, the onus was on all those who opposed anonymity to attempt to secure an amendment. An amendment was put forth and defeated by one vote. After the AHRA was passed in 2004, it governed ART through criminal law – categorizing several activities associated with ART as either prohibited or controlled under the Criminal Code, a new federal body called Assisted Human Reproduction Canada (AHRC), and new Health Canada regulations.

In 2007, however, several provinces challenged the constitutionality of the AHRA, eventually resulting in the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruling several sections of the AHRA ultra vires Parliament. Because the federal role in the regulation of assisted reproduction had to be reduced, the AHRC was dismantled in 2012. In addition to this, there was an unexplained delay in Health Canada regulations being completed and coming into full force. This meant that at the end of 2012, there was no federal body overseeing the enforcement of regulations, and many Health Canada regulations themselves were incomplete. Therefore, issues that affected donor-conceived individuals, such as donor anonymity and medical record keeping were largely ignored, and “despite years of deliberations, policy consultations, and consideration of what to do about [assisted reproductive technologies], the AHRA [did] little to alter the open market in infertility services that had only grown since the time of the Royal Commission” (Cattapan Reference Cattapan2015, 254).

In 2016, Health Canada began working on regulations that would complete the AHRA. Initially, Health Canada left donor-conceived adults off their first consultation list, saying that they would like to hear from “health professionals and associations; intended parents, surrogates, and donors; provinces and territories; industry; academics and experts; and other interested parties” (Health Canada 2020). The website was later amended to include donor-conceived adults, but this was only after complaints from advocates. The regulations were completed in 2019 and came into force in 2020.

These include regulations that outline reimbursements for gamete donors and surrogates and ensure that “establishment[s] that import… sperm or ova must ensure that the sperm or ova are processed by a primary establishment that is registered in accordance with [Health Canada] Regulations” (Health Canada 2020). However, it is unclear how the fertility clinics that import gametes can prove that they are adhering to the regulations aside from signing paperwork stating that they did (Cattapan et al. Reference Cattapan, Gruben and Cameron2019).

Furthermore, the new regulations make no mention of donor-conceived interests in accessing updated medical information, identifying genetic relatives, limiting the size of sibling groups, or achieving other policy goals advanced by donor-conceived advocates. In the Canadian context, where regulatory provisions remain minimal, these gaps translate directly into learning costs (discovering one’s donor-conceived status and locating relevant records), compliance costs (navigating fragmented systems to gather documentation or register with multiple databases), and psychological costs (coping with stigma, family tension, and the uncertainty of incomplete information). Without institutional mechanisms to address these needs, members of this population must absorb these administrative burdens themselves. In sum, administrative burdens have continued to act as mechanism to reduce the onerous experience of policy implementation for some target groups while increasing it for others.

Quebec as a policy outlier

The federal government claiming that nearly every aspect of assisted reproduction policy should be governed solely by Parliament “set Parliament on a collision course with the provinces in the Supreme Court of Canada” (Snow Reference Snow2018, 7). It is the “collision of the initial path dependent framing of the policy arena with the realities of federalism” (Snow Reference Snow2018, 14) and it resulted in a limited capacity to enforce new rules, leading to delays in enacting legislation and corresponding external regulations. However, it also opened new opportunities for policy change at the sub-national level.

Quebec has taken a different trajectory than the rest of Canada with respect to the inclusion of donor-conceived interests in policymaking. This may be due to its unique socio-legal context, given its use of civil rather than common law. Between the 1980s and 2010s, Quebec made few changes to its family law, aside from early 2000s reforms recognizing children of same-sex couples and single mothers by choice. In the 2010s, legal challenges – including Quebec’s pushback against the federal AHRA and a 2013 family law case Quebec (Attorney General) v A on common law partnerships – spurred the province to initiate broader family law reform. In 2013, the Quebec government established the Comité consultatif sur le droit de la famille (CCDF) chaired by Professor Alain Roy, a specialist in family law. The Quebec government tasked Roy with exploring possible reforms for family law and related policy areas. The resulting report, Pour un droit de la famille adapté aux nouvelles réalités conjugales et familiales (2015), known as the Roy Report, proposed comprehensive reforms.

The core of the report is that the child’s interests should be at the fore of family law and any changes made to it. It explains that “the child [should] be the determining criteria for rights and obligations” of parents and families (CCDF 2015, 68; Tremblay Reference Tremblay2018). By prioritizing legal reforms that foreground the child’s perspective, the committee’s recommendations implicitly advanced the interests of donor-conceived individuals. This shift may be reflective of the increasing prominence of donor conception within public and academic discourse, as donor-conceived individuals have become more vocal and organized. Additionally, these discussions unfolded within the broader context of family-building debates. Given that family formation and maintenance were central to these discussions, excluding donor-conceived adults from the policy conversation would have been increasingly difficult.

This alignment can also be understood as shaped by the legacy of earlier mobilization efforts, during which donor-conceived advocates attempted to embed their interests within broader debates on adoption. Moreover, the framing of children’s claims in terms of “rights” reflects a continuity with language used in federal-level debates during the early 2000s. The Roy Report (2015) served as a catalyst for two key legislative reforms in Quebec – Bill 2 and Bill 12 – which provide an empirical basis to examine how these discursive and institutional shifts translated into policy change.

Bill 2 (An Act respecting family law reform with regard to filiation and amending the Civil Code in relation to personality rights and civil status) amends the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms to include knowledge of one’s origins. A close analysis of special consultation and committee transcripts suggests that rights-based discourse, reinforced by expert opinion, played a pivotal role in shaping subsequent legislative change:

Every child who so wishes should have access to their origins and be able to take ownership of their identity and their history. This is the objective of Bill 2. We even propose making this a fundamental right enshrined in the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms (Simon Jolin-Barrette, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec 2021).

Once a child is born, it becomes a full-fledged human being with rights of its own (Line Picard, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec 2021).

The stated objective of this part of the family law reform, namely to consider children first, fully reflects one of the committee’s concerns, to effectively recognize the child as a holder of rights (Philippe-André Tessier, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec 2021).

This reflects an effort to develop legislation that broadly addresses different aspects of family life, including both its formation (e.g., adoption, third-party reproduction) and its maintenance (e.g., relationship breakdown, domestic violence), with children placed at the center of these considerations. Bill 2 passed in June 2022.

The passage of Bill 2 led to Bill 12 (An Act to reform family law with regard to filiation and to protect children born as a result of sexual assault and the victims of that assault as well as the rights of surrogates and of children born of a surrogacy project). Bill 12 reflects an effort to further address multiple dimensions of family life.

With Bill 12, we are following up on Bill 2, which laid the groundwork for a major reform of family law […]. In addition to reintroducing measures from Bill 2 that could not be studied, including surrogate pregnancy and knowledge of origins in assisted reproduction, Bill 12 corrects an aberration (Simon Jolin-Barrette, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec 2023).

Similar to the debates of the 2000s, donor-conceived interests were discussed as being separate from other stakeholders:

[W]e are interested in all the parties involved, namely the gamete donors, obviously the surrogate mothers, we are also interested in the intended parents, but we are also interested in the children, which is particularly innovative, since there are very few studies being conducted on these children currently (Isabel Côté, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec).

Do you believe if we force a donor to eventually provide information about themselves, that doesn’t reduce the possibility of being a donor? Because, for the moment, in Quebec, there is a shortage of blond, blue-eyed donors (Kariane Bourassa, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec).

[W]e cannot manage this issue as if it were a question of supply and demand. We cannot start doing assisted reproduction, precisely, in a market logic […] I think that, if we do assisted reproduction, we must do it while respecting our values and ensuring that we respect the interest of the child above all (Andréane Letendre, Special Consultation, National Assembly of Quebec).

After very little opposition, Bill 12 passed in 2023. In federal systems like Canada’s, policy competition unfolds unevenly across jurisdictions, shaped by institutional design, political culture, and varying degrees of access to power. Quebec serves as an outlier: the convergence of rights-based discourse, distinct institutional configurations, and a unique political culture enabled donor-conceived individuals’ interests to align with broader debates around family formation and maintenance. This alignment of social and legal factors appears to have opened a policy window, allowing donor-conceived people to begin securing formal legal recognition.

The resulting reforms, particularly the prohibition of donor anonymity, demonstrate how administrative burdens can be reallocated from individuals to the state. Donor-conceived individuals, as the consequent population affected by these policies, once shouldered the costs of uncovering their origins and piecing together medical or familial histories. Now, they will have access to state-facilitated mechanisms for obtaining this information. In Quebec, donor-conceived individuals who are aware of their status may benefit from reduced learning and compliance costs, as institutions take on greater responsibility for managing information. Quebec’s policy trajectory illustrates how institutional design can directly mitigate the administrative burdens borne by consequent populations, transforming their relationship to the state and altering the distribution of costs. Their recognition in Quebec law reflects an attempt at redistributing costs, demonstrating how, under different institutional and discursive conditions, consequent populations may be relieved of certain administrative burdens through targeted policy feedback and reform.

Discussion

Despite years of advocacy by donor-conceived individuals and their allies, efforts to secure a more advantageous position in this policy subsystem have yet to succeed in the Canadian context, with the exception of Quebec. Broadly, this failure ranges from formal rules (such as the AHRA and subsequent Health Canada regulations) not adequately considering their interests to bureaucratic procedures and frontline discretion creating a burdensome experience for this population. Although studies on the experiences of donor-conceived individuals into adulthood are often too limited to be generalizable, reviews of current literature show that increased transparency (e.g., early disclosure, ability to access information and support) correlates with more positive outcomes with donor-conceived people. This underscores the need for “policymakers [to] consider how to make it easier for [donor-conceived] people to have access to this information and what support should be developed to help navigate the process (Talbot et al. Reference Talbot, Hodson, Rose and Bewley2024, 9; Best et al. Reference Best, Goedeke and Thorpe2022; Blyth et al. Reference Blyth, Crawshaw, Frith, Jones, Beier, Brügge, Thorn and Wiesemann2020). However, this would require shifting the burden onto other direct target populations, such as parents, donors, industry professionals, or the state. Nevertheless, the establishment of registries in Quebec, along with other jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom and Victoria, Australia, indicate that these kinds of administrative burdens are not inevitable for the donor-conceived and that, under certain conditions, burdens can and do shift onto other groups.

This case contributes to discussions of administrative burdens by expanding upon their function and origin. Concepts such as consequent populations and consequent costs are particularly beneficial in this context. By incorporating these concepts, we can enrich the administrative burden literature with a new understanding of target populations, viewing them as active agents engaged in competition. Furthermore, these concepts help broaden our understanding of the function of administrative burdens beyond merely unintended consequences or intentional political aims. They allow scholars to recognize administrative burdens as a dynamic policy trade-off.

While this case study provides in-depth insights into the consequences of inter-actor competition on the formation of administrative burdens, it is important to acknowledge several challenges in extending these concepts to other policy domains. Different policy areas may involve distinct institutional arrangements and stakeholder dynamics, which may affect how competition manifests and how administrative burdens are distributed. Additionally, variations in data availability and the complexity of tracing interactions among multiple actors may pose methodological hurdles. Despite these challenges, the widespread presence of inter-actor competition across policy fields makes it a valuable endeavor to apply and refine these concepts more broadly.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank her committee members Dr. Linda White, Dr. Andrew MacDougall, and Dr. Alison Smith for their support.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

The author declares none.