Anthropometric charts, based on birth weight, length, and head circumference data, should be used in clinical practice for the assessment of neonatal size, and represent a useful tool to define neonates as small, appropriate or large for gestational age (GA), using defined thresholds (WHO Expert Committee, Reference Expert Committee1995). Whereas reference charts describe how a population actually grows under prevailing local conditions, prescriptive standards define how it should grow under optimal conditions, including balanced nutrition, lack of environmental constraints, and adequate healthcare (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007).

Fetal growth and neonatal size at birth are affected by several pathological conditions as well as physiological variables such as parity and sex. A number of neonatal charts is available for singletons, among those a set of international standards that complete the WHO child growth standards (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014).

Evidence has shown how singletons and twins’ intrauterine growth starts to diverge from 28th−30th week of gestation onwards, resulting in a significant difference in size at birth (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). This difference seems to be related to a physiological modulation of growth due to twinning but may be enhanced by multiplicity-associated pathologies.

Furthermore, birth weight thresholds predicting neonatal morbidity and mortality differ between singletons and twins, being lower for the latter (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022), and most twins that are classified as small for gestational age (SGA) on singletons charts do not show an increased risk for neonatal mortality or morbidities (Briffa et al., Reference Briffa, Di Fabrizio, Kalafat, Giorgione, Bhate, Huddy, Richards, Shetty and Khalil2022; Giorgione et al., Reference Giorgione, Briffa, Di Fabrizio, Bhate and Khalil2021).

Therefore, authors have postulated that when evaluating twins’ birth size, the use of twin-specific charts should be preferred; this approach has the potential to avoid over-diagnosis of SGA and its consequences, including unnecessary medical interventions, misuse of resources, and increased parental anxiety (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). This would allow healthcare providers to assess whether growth has been affected by any morbidity beyond the modulation induced by the twinning itself. This distinction is especially important in preterm twins, and especially for the widely represented group of the late preterm infants, where accurate growth assessment is critical for guiding nutritional management and monitoring for morbidity.

Numerous twin-specific charts are available, built on different populations and using various methodologies: the evaluation of the methodological quality of these studies is important to assess their applicability in clinical practice. To the best of our knowledge, such rigorous evaluation has not been performed with a systematic approach. Therefore, we performed a systematic review aiming to assess the methodological quality of studies creating twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was registered with Prospero (CRD42022356027) and reported according to the MOOSE guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000).

Eligibility Criteria

We included studies that aimed at developing cross-sectional anthropometric charts for twins at birth, published from January 1990 to April 2024. The 1990 threshold was suggested in a previously published systematic review (Giuliani et al., Reference Giuliani, Ohuma, Spada, Bertino, Al Dhaheri, Altman, Conde-Agudelo, Kennedy, Villar and Cheikh Ismail2015) since most of the advanced statistical approaches to develop charts (e.g., the LMS method) were proposed in the early 1990s (Cole & Green, Reference Cole and Green1992). No language restriction was applied.

Studies were excluded if they (1) were case series or report, editorials, commentaries, and reviews or letters without original data; (2) did not use anthropometric measurements at birth to develop charts (e.g., studies based on fetal obstetric estimates); or (3) did not develop curves specific for twins.

Search Strategy

We applied a hybrid search strategy, by combining structured database searches with predefined snowballing searches, in order to identify the highest number of relevant studies (Wohlin et al., Reference Wohlin, Kalinowski, Romero Felizardo and Mendes2022).

The systematic search was performed in December 2023 on the following electronic databases: Cinahl, Embase, Global Index Medicus, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science. The search was run again on PubMed in April 2024. Grey literature was searched on Google Scholar, bioRxiv, medRxiv, Nature Proceedings, PeerJPrePrints, Researchsquare, and greylit.org in April 2024. The search strategy consisted of search words on the key concepts of ‘twin’, ‘newborn’, ‘birthweight’, and ‘chart’. The search strategy used for PubMed, then adapted for the other databases, is available in Appendix A.

The five most cited relevant studies identified through the systematic search (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Kogan, Martin and Papiernik1998; Arbuckle at al., Reference Arbuckle, Wilkins and Sherman1993; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Deng, Li, Yi, Li, Mu, Li, Yao and Wang2017; Dollberg et al., Reference Dollberg, Haklai, Mimouni, Gorfein and Gordon2005; Sankilampi et al., Reference Sankilampi, Hannila, Saari, Gissler and Dunkel2013) were screened on PubMed for the list of similar and cited by papers (in April 2024). Moreover, the reference lists of all included studies were screened to find additional articles.

Selection Process

The search results from different databases were merged using the EndNote software, and duplicates automatically removed by the software. Each record was independently screened by two authors (SD, SG) to determine inclusion on the basis of eligibility and exclusion criteria, firstly by title and abstract, hence by full-text screening. Conflicts during the screening process were solved by discussion or by involvement of a third reviewer (FG).

Data Collection

We developed two standardized data extraction forms to collect information on study characteristics and study methodology (Appendix B).

The descriptive data extraction form collected data on study details (e.g., country where the study was conducted, years of enrolment), population details (e.g., sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant baseline characteristics), output details (e.g., anthropometric variables included in the charts, chart presentation). The qualitative data extraction form collected data on study design, statistical methods, and reporting of the results. Two reviewers (SD, SG) independently extracted the data from the included studies. The extracted data were cross-checked, and, if any difference was identified, a third reviewer was involved (FG). A team member specialized in statistics (IS) reviewed the items related to study statistical methods.

Study Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated by the 16-items grading system used in our previous evaluation of neonatal anthropometric charts for singletons (Giuliani et al., Reference Giuliani, Ohuma, Spada, Bertino, Al Dhaheri, Altman, Conde-Agudelo, Kennedy, Villar and Cheikh Ismail2015) plus two additional items related to twins (determination of chorionicity and determination of birth weight discordance). Data extracted in the qualitative data form were used to define 18 quality items, grouped into three domains: study design, statistical methods, and reporting of results. Each item was scored as low risk of bias (score = one) or high risk of bias (score = zero) (Appendix C).

The qualitative assessment was performed independently by two reviewers (SD, SG). Conflicts were resolved by consultation with the third reviewer (FG).

Data Synthesis

Scores for the three individual domains, and the overall quality score were computed. The median, interquartile range (IQR) and range were calculated as the summary measure of the distribution of scores of the included studies.

Results

We identified 5625 records from database searches, and 12,040 records from grey literature search and snowballing search. After deletion of duplicates, 17,090 records were screened by title and abstract, and 191 records were found to be relevant for full-text screening. Ultimately, 68 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for the systematic review.

The main characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. Twenty (29%) studies were published between 1990 and 2000, 18 (26%) between 2001 and 2010, and 30 (44%) after 2010. Thirty (44%) studies were conducted in the European Region, 21 (30%) in the Western Pacific Region, 13 (19%) in the Region of the Americas, one in the African region, one in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, and one in the South-East Asian Region. One study was a multicenter study conducted in two different WHO regions (Western Pacific Region and Region of the Americas).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of selected studies

Note: BW, birth weight; BL, birth length; GA, gestational age; HC, head circumference; MUAC, middle upper arm circumference; CC, chest circumference; W*L, weight for length.

Fifty-one studies (75%) were published in English, five (7%) in Spanish, three (4%) in German, two each (9%) in Chinese, Russian and Italian, and one each in (4%) in Hungarian, French, and Korean.

Study Design

There was great variability in sample size (from 80 to 1,346,477 participants; median 8454), and minimum GA considered in the charts (between 20−23 weeks in 43% of studies, between 24−27 weeks in 38% of studies, and 28 or more weeks in 19% of the studies).

Regarding anthropometric variables, 50 studies (75%) reported birth weight only; one study reported birth weight and body length; one study reported birth weight and head circumference; two studies reported body length only. All three main anthropometric variables, that is, birth weight, body length and head circumference, were reported in 14 studies (21%).

Authors aimed to construct a reference chart in 44% of studies and a standard chart in 21% of studies. In the remaining studies (35%), it was unclear whether the aim was to create a reference or a standard chart.

Most studies (84%) aimed to create charts for twins born in a specific geographical area. However, the percentage of twin neonates included in the charts out of the total number of twins born in that geographical area at the given time was not specified.

In 53% of the studies, data were extracted from birth registries, in 35% from hospital records, in 9% from research forms, in 3% from other sources, and in 1% the data source was unclear. Among the hospital-based studies, 18 were single-centre and 11 were multicenter (range 2 to 95 centres).

Only six studies (9%) were preplanned (i.e., before the recruitment of neonates).

Great variability in exclusion criteria was observed among included studies: 48 (71%) excluded stillbirths and babies with congenital malformations, 11 (16%) adopted additional exclusion criteria (e.g., maternal chronic diseases, smoking, significant birth-weight discordance, and other factors that could impair fetal growth), 2 excluded monoamniotic twins (de Paepe et al., Reference De Paepe, Shapiro, Young and Luks2015; Odibo et al., Reference Odibo, Cahill, Goetzinger, Harper, Tuuli and Macones2013), 1 excluded nonspontaneous pregnancies (Sankilampi et al., Reference Sankilampi, Hannila, Saari, Gissler and Dunkel2013), and 1 included only twins conceived by in-vitro fertilization (Dickey et al., Reference Dickey, Pridjian, Xiong and Klempel2017). Nine studies (13%) did not report exclusion criteria.

Chorionicity was evaluated in 12 studies (18%), but only in 8 studies were charts developed by chorionic placentation.

In 19 studies (28%), the method for GA evaluation was not described. Only 22 studies (34%) reported a reliable method for GA estimation: 21 used both last menstrual period and first trimester ultrasound and one, which included only infants conceived by in-vitro fertilization, added 14 days to the number of completed weeks since oocyte fertilization (Dickey et al., Reference Dickey, Pridjian, Xiong and Klempel2017).

There were considerable methodological issues in anthropometric evaluation: measurement instruments were reported and reliable in only 13 studies (19%), measurement techniques were described and reliable in 19 studies (28%), and training of the operators was reported in 4 studies (6%).

Statistical Methods

Statistical models were inappropriate or not adequately described in 31 studies (46%). Forty-nine percent of the studies developed growth curves estimated by regression models (linear, multivariate, quadratic, generalized linear models [GLM] or least mean square [LMS]). Only two studies (3%) used advanced ad hoc methods such as Bayesian models that allow more precise estimates of growth curves through appropriate smoothing techniques. Outliers were adequately evaluated and excluded in 20 (29%) studies. Eighteen studies (26%) did not consider gender as a covariate and did not produce gender-specific charts. Only 11 studies (16%) reported a control of goodness of fit. In 10 of them, the goodness of fit was embedded in the estimating method, while in the remaining one a worm plot for ‘visual inspection’ was reported. Smoothing techniques were reported in 31 (46%) studies. In many cases, the smoothing was embedded in the estimating model (cubic spine, LMS method, Bayesian method, and GAMLSS [generalized additive model for location, scale and shape]), while in seven studies post-hoc techniques were used (weighted mean or automatic graphical smoothing by the used statistical software).

The precision of the estimates, defined by standard errors or confidence limits of extreme centiles, were reported in 43 (63%) studies: three presented standard errors; 12 did not report standard errors but used LMS or GAMLSS methods, in which calculation of standard errors is embedded; and 28 neither reported standard errors or used LMS or GAMLSS methods, but provided a precision of estimates by confidence intervals, smoothing techniques or regression methods.

Reporting of Results

The study population characteristics were reported in 30 (44%) studies. The 10th, 50th and 90th centiles and z-scores were reported or computable in 56 (82%) and 34 (50%) studies, respectively. In 33 (48%) studies, only mean and standard deviation or centiles tables were presented.

Risk of Bias

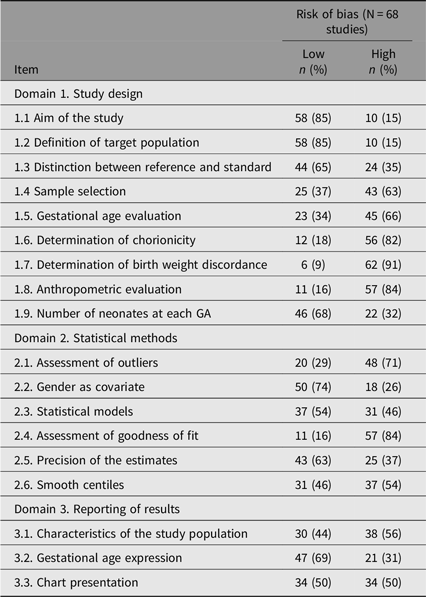

The risk of bias of the included studies is presented in Table 2. For the 68 included studies, the median, mean, interquartile range, and range of quality scores for each of the three domains are summarised in Figure 2. The median overall quality score was 44% (IQR 33−61%, range 11−83%).

Table 2. Risk of bias for each of the 18 items assessed in the three domains

Figure 2. Whisker plot showing the range of quality scores across individual domains and the overall quality score. Each box represents the interquartile range (IQR), with the line indicating the median. Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum observed values. Notably, in Domain 3, the median and third quartile values overlap, indicating a clustering of high scores within the upper range.

Twenty-six studies (38%) had an overall quality score above 50%, but only 10 (15%) reached a quality score above 50% in each of the three domains.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to critically appraise studies which developed twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts. This study has shown that there is substantial heterogeneity and limitations in the methodological quality of studies aimed at creating twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts.

We identified 68 twin-specific neonatal charts, the majority of which were affected by major methodological flaws that limit their reliability in clinical practice. The most common deficiencies were related to the determination of birth-weight discordance, anthropometric evaluation, determination of chorionicity, and assessment of goodness of fit, which were adequately addressed in only ≤18% of included studies.

To define whether an anthropometric chart is a reference or standard is of foremost importance in its building and implementation. When the population used to build the charts includes neonates with risk factors for impaired fetal growth, the chart is a reference that describes ‘how growth actually is’ in such population. Differences between references may arise from the different prevalence of environmental, nutritional, socioeconomic, and health conditions that can affect fetal growth. Exclusion of all neonates exposed to any known risk factor for intrauterine growth restriction is the basis for a prescriptive standard that describes ‘how growth should be’ (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007; Grummer-Strawn et al., Reference Grummer-Strawn, Garza and Johnson2002). When these exclusion criteria are met, it has been demonstrated that fetal growth is similar across different regions (Garza & de Onis, Reference Garza and de Onis2004; Uauy et al., Reference Uauy, Casanello, Krause, Kusanovic and Corvalan2013). Hence, a unique international standard could be applied to all populations and represent the best tool for the anthropometric evaluation of newborns worldwide. From our search, it emerged that the exclusion criteria of almost all included studies are those of a reference, hence not applicable at an international level. The only study that fulfilled the criteria of a standard, that is, the exclusion of neonates exposed to known risk factors for impaired fetal growth (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007), is the study by Bossi et al. (Reference Bossi, Cortinovis, Milani, Gallo, Kusterman and Morotti1994). This is a good quality study, which applied exhaustive exclusion criteria, and a rigorous protocol for anthropometrical evaluation. However, those charts, built on neonates born more than 40 years ago, have some limitations, especially concerning reliability of GA, which was estimated by last menstrual period only.

An area-based study aims to include all neonates born in a specific geographical area during a given period (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Altman, Purwar, Noble, Knight, Ruyan, Cheikh Ismail, Barros, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Bertino, Gravett, Bhutta and Kennedy2013). Within these geographical and temporal frames, the target population on which the chart is built must be defined by clear inclusion criteria (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007; Milani et al., Reference Milani, Bossi, Bertino, di Battista, Coscia, Aicardi, Fabris and Benso2005) and should include a high percentage (e.g., above 80%; Villar et al., Reference Villar, Altman, Purwar, Noble, Knight, Ruyan, Cheikh Ismail, Barros, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Bertino, Gravett, Bhutta and Kennedy2013) of the target population. Studies included in our review are mainly area-based. However, the percentage of infants selected from the target population on which those charts are built was not reported. Moreover, several studies did not state clear inclusion and exclusion criteria.

A prospective preplanned study design is a requirement for a reliable anthropometric chart (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007). In our review, we disclosed a very low percentage (9%) of preplanned studies. Instead, more than half of the included studies retrospectively extracted data from birth registries: this affects their reliability; in particular, regarding GA evaluation and anthropometric measurements.

Reliable GA estimation, based on both last menstrual period and first trimester ultrasound, is of foremost importance to build anthropometric charts (Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Papile and Macones2017; Villar et al., Reference Villar, Altman, Purwar, Noble, Knight, Ruyan, Cheikh Ismail, Barros, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Bertino, Gravett, Bhutta and Kennedy2013). Only 34% of the studies included in our review adopted a reliable method to assess GA.

Of great importance, anthropometric measurements should be taken with standardized instruments and techniques, by trained and standardized operators (Benso et al., Reference Benso, Nicoletti and Gilli2004; Cheikh Ismail et al., Reference Cheikh Ismail, Knight, Ohuma, Hoch and Chumlea2013). Only a minority of the studies included in our review fulfilled these criteria. A complete neonatal auxological evaluation must include weight, body length and head circumference (Benso et al., Reference Benso, Nicoletti and Gilli2004). A major limitation of the studies included in our review is that most of them evaluated birth weight only, while all three variables were reported in only 14 (21%) of them.

Regarding chorionicity, it is still debated whether monochorionic and dichorionic twins need separate anthropometric charts (Dall’Asta et al., Reference Dall’Asta, Rizzo and Ghi2023; Melamed et al., Reference Melamed, Hiersch, Kingdom and Fox2023): the difference in growth related to chorionicity seems to be too small to be clinically significant and justify chorionic-specific charts (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). In our review, only eight studies (12%) developed charts by placental chorionicity.

It is widely recognized that gender affects neonatal size at birth: however, one quarter of the studies included in our review did not produce gender-specific charts.

Regarding statistical methods, it is crucial to use an adequate statistical model to construct reliable anthropometric charts. In our review, the statistical models were not adequately described or not appropriate in nearly half of the included studies.

The methods used for the assessment of goodness of fit were not reported in the majority of studies. This does not allow the reader the evaluate the adequacy of the model used to trace charts.

The precision of the estimates is a relevant measure of the reliability of a chart. The precision of centile estimates increases with number of observations. Main areas of concern are external centiles in which the number of neonates is smaller. Standard errors or confidence limits of extreme centiles, which define the precision of those estimates, were not reported in 25 studies. Moreover, the number of neonates at each GA was not reported in 22 studies.

Smoothing reduces the fluctuation of raw centiles due to sample variability (Bertino et al., Reference Bertino, Milani, Fabris and De Curtis2007). To note that almost half of the included studies adopted descriptive approaches without the application of statistical models specific for tracing smoothed growth charts.

Presentation of neonatal size only by graphical methods without including numerical values makes the chart difficult to be used in clinical practice. In nearly 20% of the studies, values of at least 10th, 50th and 90th centiles were not reported or computable.

The possibility to express an anthropometric variable as z-score allows a better comparison between different subjects and statistical analyses in research. In half of the studies, z-scores were not reported or computable.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of our study include: (1) the use of the most rigorous and up-to-date methodology for performing a systematic review of observational studies, in line with the MOOSE group recommendations; (2) the extensive literature search with the use of different databases, without language restrictions, which allowed us to find and include studies that were published in English, Spanish, German, Chinese, Russian, Italian, Hungarian, French and Korean in the systematic review; (3) the inclusion of a relatively large number of studies and of participants from different populations throughout the world; and (4) the use of a quality score checklist, which allowed an objective and quantitative assessment of study methodology.

Some potential limitations of our study should be considered: (1) the risk of bias in the data abstraction process information and in the study quality assessment since reviewers were not blinded to the origin and authors of included studies; and (2) it is possible that older studies in this systematic review were assessed according to quality criteria which have only been established in recent years.

Conclusions

This systematic review has identified substantial heterogeneity of methodology used in studies designed to create twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts. We propose that the checklist we used for assessing the study methodological quality be used in future studies in order to improve consistency in twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts research. It has been increasingly recognized the need of specific charts for the anthropometric evaluation of twin newborns (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). The high number of studies identified in our search confirms this interest and need. However, studies that have so far developed twin-specific neonatal anthropometric charts have substantial methodological heterogeneity and limitations. Moreover, those charts are mainly references, derived from specific countries or regions at specific time points, and hence do not allow comparison among different populations or their use at international level.

The development of a high-quality international standard for newborn twins is of great relevance in both clinical practice and research for an appropriate auxological evaluation of twins worldwide.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2025.10027

Acknowledgments

We thank the librarians from the University of Turin and the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, for their expert support in the literature search and retrieval.

Financial support

No external funding was received for this study.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.