1. Introduction

In the face of global population aging and individuals living longer with chronic health conditions or disabilities, demand for long-term care is accelerating. The delivery of such care poses a major challenge to social policy and practice in China and around the world. Long-term services and supports include certain institutionally based and non-institutionally based long-term services and supports (Harris-Kojetin et al., Reference Harris-Kojetin, Sengupta, Lendon, Rome, Valverde and Caffrey2019). Many countries have opted to shift the provision of care from institutionally based long-term services and supports (e.g. hospitals and long-term care facilities) to non-institutionally based long-term services (e.g. home and community settings) for cost savings. In turn, such substitution might lead to more efficient use of nursing home and hospital beds (Mah et al., Reference Mah, Stevens, Keefe, Rockwood and Andrew2021; Perkins, Reference Perkins, Ferraro and Carr2021), though emerging evidence suggests prolonged aging in place may not always yield efficiency gains (Bakx et al., Reference Bakx, Wouterse, van Doorslaer and Wong2020).

The formal long-term care services in China are featured by rapid growth of the institutional care sector and slow development of home and community-based services (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Glinskaya, Chen, Gong, Qiu, Xu and Yip2020). Demographic and socioeconomic changes are weakening informal care while escalating the needs for formal long-term care services for older adults in China (Feng and Wu, Reference Feng and Wu2023). According to Ministry of Civil Affairs of China (2024), by the end of 2023, China’s elderly population reached 296.97 million, accounting for 21.1 percent of the total population. Nearly one-quarter of this population had physical or cognitive impairment, with an increasing demand for long-term care (Glinskaya and Feng, Reference Glinskaya and Feng2018; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Guo, Du, Yang and Wang2022). However, Ministry of Civil Affairs of China (2024) indicates that there were only 8.23 million long-term care beds by the end of 2023. Both institutional care and home and community-based services need to expand to meet the growing need of the aging population (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Gao and Luo2013).

China has achieved near-universal health insurance coverage, covering over 95 percent of the population through two principal social health insurance schemes: the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and the Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI). The expansion of health insurance has significantly improved older adults’ access to healthcare services. However, the burgeoning demand for long-term care (LTC) of frail and disabled older adults have become a challenge due to limited access to formal care (Glinskaya and Feng, Reference Glinskaya and Feng2018; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Guo, Du, Yang and Wang2022; Dang, Reference Dang2023) and declining informal care resulting from reduced family size and increased labor participation of women (Zhu and Oesterle, Reference Zhu and Oesterle2017). Consequently, individuals are increasingly compelled to seek formal care from hospitals, further occupying hospital beds and leading to a surge in medical expenditures (Fried et al., Reference Fried, Bradley, Williams and Tinetti2001; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Glinskaya, Chen, Gong, Qiu, Xu and Yip2020). To optimize the allocation of medical resources, reduce healthcare expenditures, and address the long-term care needs of aging populations, China launched a pilot Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) program across 15 cities in 2016, subsequently expanding it to an additional 14 cities by 2020.

Existing cross-culture studies have focused more on the association between LTCI and improved health outcomes, as well as reduced healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket medical expenditures (Chen and Ning, Reference Chen and Ning2022a; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Bai, Hong and Liu2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guan and Wang2023). Research indicates that LTCI has contributed to better self-reported health and a reduction in out-of-pocket medical expenditures in China (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Bai, Hong and Liu2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guan and Wang2023). LTCI reduced outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and the length of inpatient stays among older adults in the past year (Chen and Ning, Reference Chen and Ning2022a). Some studies found that LTCI policy is associated with a reduction in healthcare utilization (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park and Jang2023) and lower mortality risk among care beneficiaries in Korea (Sohn et al., Reference Sohn, O’Campo, Muntaner, Chung and Choi2020). Meanwhile, an increasing number of studies have examined the impacts of LTCI on informal caregiving and living arrangements (Pei et al., Reference Pei, Yang and Xu2024; Zhu and Bai, Reference Zhu and Bai2025). Prior research has found that LTCI has reduced the burden of family caregiving (Chen and Ning, Reference Chen and Ning2022b; Pei et al., Reference Pei, Yang and Xu2024; Zai, Reference Zai2024) and increased workforce participation among family caregivers (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Noguchi, Kawamura, Takahashi and Tamiya2017). Home-based LTC services have been shown to prevent an increase in care needs (Koike and Furui, Reference Koike and Furui2013), and subsidy policies have increased the utilization of home help services, albeit not affecting visiting care and adult daycare services among low-income families as much (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Hashimoto, Tamiya and Yano2006). LTCI has encouraged older adults to live independently in China (Zhu and Bai, Reference Zhu and Bai2025), while in the United States it has reduced the likelihood of adult children co-residing and promoted stronger labor market attachment (Coe et al., Reference Coe, Goda and Van Houtven2023). In addition, some studies have examined the impacts of LTCI on the consumption and savings of households with older adults (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma and Zhao2023; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zheng and Li2024). Despite the positive impacts of LTCI on alleviating the burden of informal caregiving and improve the well-being of older adults, a critical gap remains in understanding its role in facilitating access to home and community-based services (HCBS) for older adults.

Aging in place is preferred by older adults across cultures and can reduce healthcare expenditures. Existing research showed that publicly financed home care may be both more cost-effective and beneficial than institutional care for the least able (Kim and Lim, Reference Kim and Lim2015), and early community-based service utilization can delay institutionalization (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005). Some studies also suggested that both informal and formal home care will reduce the risk of depression of dependent elderly and increase their general mental health (Barnay and Juin, Reference Barnay and Juin2016). Aligned with ongoing reforms in long-term care, this study focused on non-institutional long-term services, particularly HCBS. HCBS can help people to receive care at home, rather than in a hospital or nursing home, and to live as independently as possible in the community based on each person’s own level of abilities. The overarching objectives of HCBS are to improve or maintain an optimal level of physical functioning and quality of life and enable older adults to ‘age in place’ with dignity while alleviates informal caregiver burden. Over the past decade, initiatives for promoting aging in place have been launched across the country, such as respite services that provided short-term relief for primary caregivers and elderly care stations (yang lao yi zhan) where older adults can visit and receive help in the community.

Our study contributes to the existing literature in the following two ways. First, the accessibility of HCBS is closely related to the health and well-being of older adults, yet the impact of LTCI on the physical accessibility of HCBS has been relatively understudied in the literature. Utilizing panel data from the 2014–2021 Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), this study employs the difference-in-differences (DID) approach to assess the impact of LTCI on the physical accessibility of HCBS among older adults.

Second, this study explores the heterogeneous effects by potential demand for HCBS of older adults and program designs. Regarding potential demand for HCBS of older adults, the impact of LTCI on the accessibility of HCBS is more pronounced for older adults who live alone or with a spouse only, have ADL limitations, and receive fewer financial transfers from children. In terms of program design, our findings reveal that the impact of LTCI on HCBS is more salient in pilot cities with higher compensation for HCBS (vs institutional care) and targeting individuals with moderate or severe disability or dementia (vs only with severe disability).

2. Institutional background

Since 2013, the Chinese government has expanded HCBS to cut healthcare costs, resulting in notable growth in both number and type of non-institutionally based long-term care services. By the end of 2023, the number of residential care facilities was approximately 41,000, compared with around 363,000 community-based facilities with 3.058 million beds, suggesting that the supply of HCBS were substantially higher than residential care (Ministry of Civil Affairs of China, 2024). However, the increasing number of HCBS still can’t meet the needs of growing aging population (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Guo and Chen2023). Although the overall supply of HCBS has steadily increased, highly variable quality of care resulting from weak quality regulation and the lack of a qualified and professional workforce are urgent issues (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Glinskaya, Chen, Gong, Qiu, Xu and Yip2020).

The intended goal of LTCI is to increase the provision of formal care and mitigate the burden of healthcare systems in China. The central government announced a pilot long-term care insurance in 15 cities across the country in 2016. The subsequent phase in 2020 included additional 14 pilot cities. A noteworthy aspect of this evolution was the independent implementation of LTCI by selected local administrations. By the end of 2023, China has implemented 49 LTCI pilots across a range of cities, covering about 183.309 million individuals and providing benefits to 1.343 million beneficiaries. In fiscal year 2023, the LTCI fund recorded a total revenue of 24.363 billion RMB against total expenditures of 11.856 billion RMB. Furthermore, the program accredited 8,080 service entities, underpinning a workforce of 302,800 caregiving personnel (National Healthcare Security Administration, 2024). Our study uses data from 2014 to 2021 from both pilot cities and autonomously initiated cities to evaluate the multifaceted impacts of LTCI coverage.

LTCI is financed by existing social health insurance programs, with UEBMI covering formal-sector employees and URRBMI covering the rest of the population (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Glinskaya, Chen, Gong, Qiu, Xu and Yip2020). Although most pilot cities also have supplemental funding from the government, individuals, or employers, UEBMI and URRBMI finance the largest portion of long-term care services. All pilot cities covered UEBMI enrollees, while a handful also covered URRBMI enrollees. The eligibility for long-term care services is generally defined based on functional limitations. In China, beneficiaries must be severely disabled for at least 6 months, assessed by the Barthel scale or its variants developed by the pilot cities.

The benefit package regarding service coverage and expense reimbursement varies across pilot cities in China. The service coverage in Chinese LTCI includes HCBS and/or residential care (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Glinskaya, Chen, Gong, Qiu, Xu and Yip2020). Cash benefits were provided to informal caregivers in some pilot cities in China.

3. Methods

3.1. Data

Data are drawn from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), collected by the Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies at Peking University in China. The 2021 data, the most recent available, were collected by the PKU Center for Healthy Aging and Development and the China Population and Development Research Center. This survey is collected through in-person interviews by a team comprising professionally trained staff members and community nurses and doctors. Extensive information is gathered encompassing demographic characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and both physical and psychological health. A detailed description of the CLHLS design can be found in previous publications (Yi et al., Reference Yi, Gu, Poston and Ashbaugh Vlosky2008).

This study analyzes three waves of CLHLS data (2014, 2018, and 2021) that span the LTCI implementation period from 2014 through 2021, with most pilot regions adopting the policy during 2015-2021, thereby providing complete policy lifecycle coverage aligned with survey administration. We only keep older adults that are observed at least twice in our study sample, as older adults with only one data point do not contribute to the identification in the model specification with individual fixed effects. The initial pooled sample consists of 13,622 older adults, aged 60 and above. We exclude 249 urban older adults from Qingdao who are covered by the local LTCI pilot in 2012 and only consider Qingdao’s 2015 reform for rural residents, due to the LTCI’s pre-study implementation in these urban areas. Consequently, the final sample for our study comprises 13,373 older adults, yielding a total of 28,395 observations across 165 prefecture-level cities.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Physical accessibility of home and community-based services

Home and community-based services encompass personal daily care, health education, psychological consulting, shopping, social and recreation activities, and legal aid or neighborhood-relation services for older adults in the CLHLS. We operationalize physical accessibility using a binary measure (1 = able to obtain; 0 = unable to obtain) indicating whether older adults can successfully secure at least one home and community-based service. In addition, we employ the number of home and community-based service types (range 0–6) as a variable to assess the extent of service accessibility. For example, a score of 6 indicates that the respondent is able to access to all six home and community-based services. Furthermore, we also examined the accessibility of each home and community-based service.

3.2.2. LTCI treatment status

The LTCI treatment status of older adults depends on whether the respondents are living in the LTCI pilot cities and the public health insurance program they enrolled in. For instance, an individual would be assigned to the treatment group if they live in a pilot area and participate in the URRBMI program when the local policy explicitly covers this insurance type. In our study sample, 27 out of 165 prefectural-level cities have implemented LTCI by the time the CLHLS survey is conducted in 2021, including 10 cities in the officially-announced pilot list in 2016, 6 cities in the officially-announced pilot list in 2020, and 11 cities where the local governments had launched the program during 2014–2021. We construct an indicator of whether the respondent is covered by LTCI based on whether they reside in a LTCI pilot area and public health insurance type of older adults (i.e., UEBMI for urban employees, URRBMI for urban residents, and URRBMI for rural residents). In our study sample, all 27 pilot cities provide LTCI coverage for UEBMI enrollees. Of these, 11 cities also cover both urban and rural residents enrolled in URRBMI, and 3 cities only cover urban enrollees under URRBMI. All pilot regions provide concurrent coverage for both institutional care and HCBS, allowing enrollees to choose between these options. Our study sample of 27 pilot regions reveals three distinct benefit patterns: (1) eleven regions (e.g., Suzhou) offer more generous benefits for HCBS; (2) twelve regions (e.g., Qiqihar) provide preferential benefits for institutional care; and (3) four regions (Tai’an, Weihai, Chongqing, and Kaifeng) maintain equal benefit levels for both service types.

In the main specification, we construct an indicator of the period after the LTCI pilot programs. However, pilot cities introduce LTCI at different time points. As an alternative approach, we also generate a continuous variable indicating the duration of LTCI program in the city at the time of survey. We calculate the LTCI duration in a city by subtracting each city’s date of pilot initiation from the interview date of each respondent in the city. It is coded as 0 if the respondent is interviewed before the LTCI introduction or from non-pilot cities.

3.3. Empirical specification

To assess the impact of LTCI on physical accessibility of HCBS, we employ time-varying DID approach. This method is applied when the treatment is introduced at different times across different regions (Goodman-Bacon, Reference Goodman-Bacon2021). The DID model incorporates individual fixed effects (FE) within a three-wave panel dataset. This methodology facilitates the identification of LTCI’s effect by comparing the change in HCBS accessibility for LTCI-eligible older adults in pilot cities against that of ineligible counterparts in both pilot and non-pilot cities after LTCI implementation. The DID specification is formalized as below:

where Y ict refers to the outcome variables of older adult i living in city c in year t. Elig ic is a treatment dummy variable (1 = had LTCI, 0 = no LTCI). This variable is determined by whether any older adult has the types of public health insurance targeted by LTCI according to local eligibility policies. Notably, the type of public health insurance for older adults is linked to their pre-retirement employment status and remains constant throughout the study. Post ct is a binary indicator coded as 1 for all years following the implementation of LTCI pilot programs and 0 for all pre-implementation years, thus representing treatment status. The coefficient β 1 on the interaction term Elig ic * Post ct represents the DID estimate of interest. Furthermore, Post ct , also captures the duration of LTCI coverage at the survey time, leveraging the temporal variation in city-level program rollout and interview dates. As a robustness check, our analysis is alternatively confined to older adults in pilot cities only.

X ict encompasses a range of individual characteristics, such as age, gender, marital status, educational attainment (measured in years of schooling), hukou status (urban or rural), household dynamics (e.g. number of living adult children, per capita household income), limitations in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson and Jaffe1963), and self-reported health status (0 = poor, 1 = fair, 2 = good). Capita household income was measured using the average household income over the past year, with its logarithmic form included in the models. Physical impairment was defined as difficulties in any of the six ADLs-eating, dressing, bathing, going to the toilet, indoor transfer, and continence. ADL scores ranged from 6 (fully independent) to 18 (severely impaired), with higher scores indicating worse functioning (>6 indicating the presence of ADL limitations). Additionally, we controlled for a set of area-by-year variables, including the logarithm of per capita GDP, the logarithm of per capita fiscal expenditure, and number of hospital beds per 1000 persons at the city level. Individual fixed effects μ i account for time-invariant personal attributes that are unobservable. Year fixed effects η t adjust for temporal variations affecting all older adults. ε ict is a random error component. In all estimation models, standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline results

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for our study sample. Within this cohort, 55.6 percent of older adults have physical access to HCBS. A breakdown of this accessibility reveals that health education is the most prevalent service, accessed by 42.2 percent of participants. This is followed by legal aid or neighborhood-relation services (34.2 percent), social and recreation activities (23.8 percent), psychological consulting (14.3 percent), personal daily care (12.3 percent), and shopping (11.3 percent). The group receiving treatment constitutes 14.3 percent of the sample.

Table 1. Summary statistics (CLHLS 2014–2021)

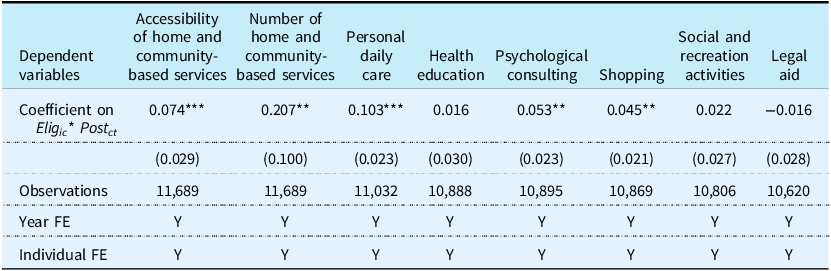

Table 2 shows the estimated effects of LTCI coverage on the physical accessibility of HCBS. The results are derived from Eq. (1), controlling for individual and household characteristics, area characteristics, year fixed effects, and individual fixed effects. The findings indicated that LTCI coverage has both an economically and statistically significant impact on the physical accessibility of HCBS. Specifically, LTCI coverage enhances the likelihood of accessing HCBS by 7.4 percentage points and increases the number of accessible HCBS by 0.207. Compared to the pre-LTCI mean, the physical accessibility of HCBS increased by 11.4 percent following the implementation of LTCI. Further, a detailed examination of each specific service reveals that LTCI coverage significantly increases the likelihood of accessing personal daily care (by 10.3 percentage points), psychological consulting services (by 5.3 percentage points), and shopping services (by 4.5 percentage points). This suggests that older adults with LTCI are 10.3 percentage points more likely to access personal daily care, 5.3 percentage points more likely to access psychological consulting services, and 4.5 percentage points more likely to access shopping services than those without LTCI. The most substantial increase is observed in personal daily care services, suggesting a meaningful enhancement in the welfare of older adults. This aligns with the foundational goals of LTCI implementation.

Table 2. Impact of LTCI coverage on accessibility of home and community-based services

Notes: All regressions control for individual and household covariates, as well as area-by-year covariates, as specified in Table 1. * p < .1; **p < .05; *** p < .01.

4.2. Validity of the difference-in-differences strategy

4.2.1. Event study

In our study, the DID specification presupposes that, in the absence of LTCI, the relative outcomes for the treatment group would mirror those of the control group. To scrutinize this assumption, we undertook an event study analysis focusing on the accessibility of HCBS. This analysis involved modifying Equation (1) by substituting the interaction term Elig ic * Post ct with a series of timing dummies. These dummies represent the years before and after the implementation of LTCI.

Figure 1 shows the years surrounding LTCI implementation on the x-axis. The event time ‘0’ denotes the year of reform, while ‘-1’ serves as the reference category, representing the year immediately preceding LTCI implementation. The pre-reform period estimates are all statistically insignificant, suggesting no notable pre-existing differences in HCBS accessibility between the treatment and control groups. This finding is crucial as it validates the DID assumption of parallel trends before the intervention.

Post-LTCI implementation, the timing dummies exhibit predominantly positive coefficients. While the first two years following implementation show marginal changes, a significant increase in HCBS accessibility becomes evident from the third year onwards. Notably, the impact of LTCI appears to intensify by the fifth year. This result underscores the validity of our initial findings and the effectiveness of LTCI in enhancing HCBS accessibility over time.

4.2.2. Placebo test

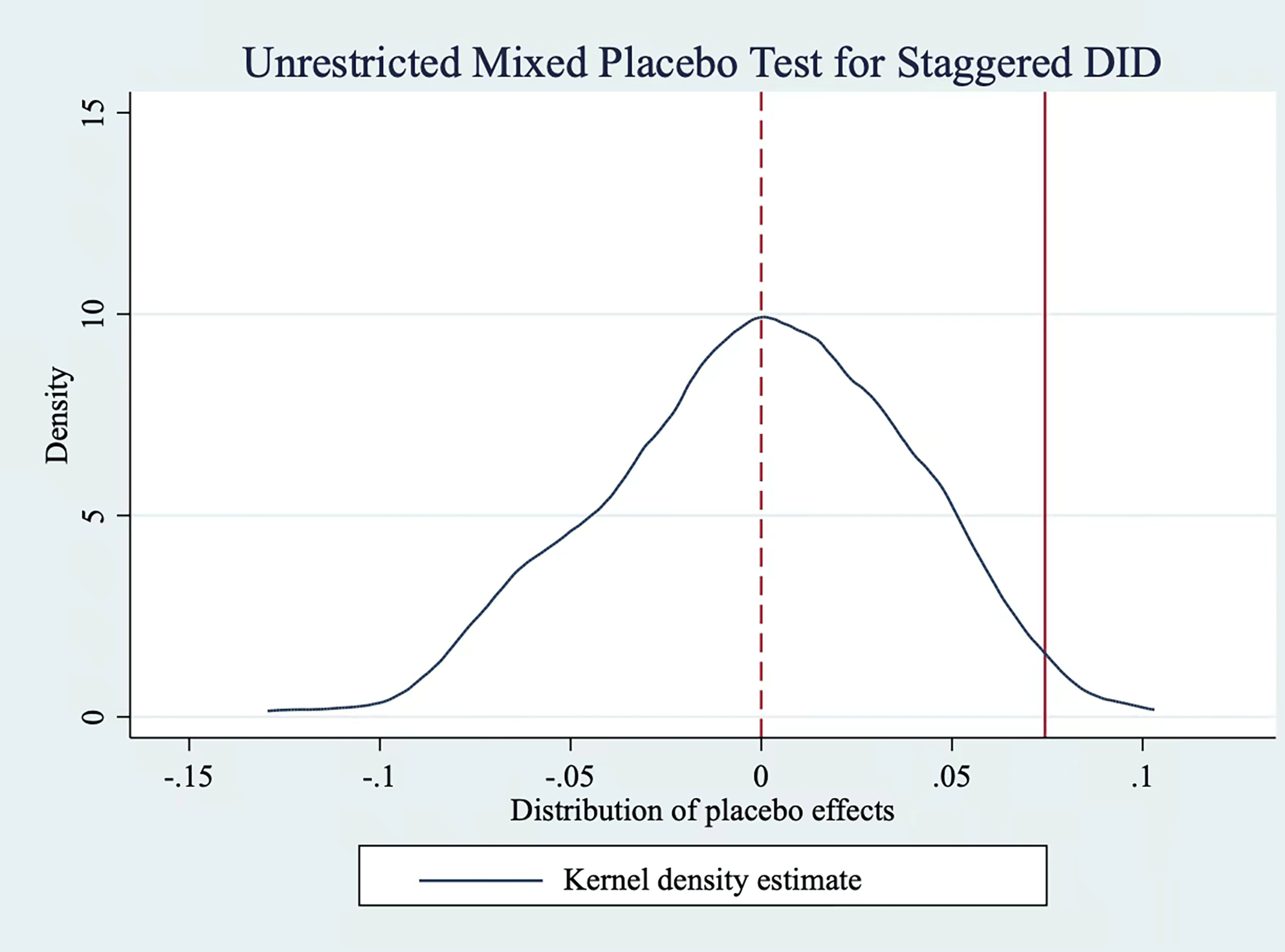

To address potential influences of other policies on the accessibility of HCBS and to mitigate concerns regarding omitted confounding events, we conducted a mixed placebo test. This test involved a counterfactual approach, wherein we randomly selected 27 cities from the total pool of 165 cities, designating them as ‘pseudo treatment groups’. It’s important to note that in our actual sample, the real treatment group comprised individuals from 27 pilot cities. Then, we chose a unified ‘pseudo treatment time’ for these cities, enabling us to perform DID estimation. To quantify the placebo effect, we generated 500 bootstrap samples, which provided a robust statistical basis for our analysis.

Figure 2 illustrates the results of this test through a kernel density plot and histogram representing the distribution of the placebo effect. The treatment effect estimate, marked by a vertical solid line in the figure, is notably positioned at the right tail of this distribution. This result indicates that the treatment effect is an extreme value when compared to the placebo effects. Statistically, the two-sided p-value is 0.048, and the right-sided p-value is 0.014. These values allow us to reject the null hypothesis that the treatment effect is zero at the 95 percent confidence level. Furthermore, the distribution of the placebo effect predominantly clusters around zero and follows a normal distribution pattern. This observation suggests that our primary findings are valid.

4.2.3. Robustness checks

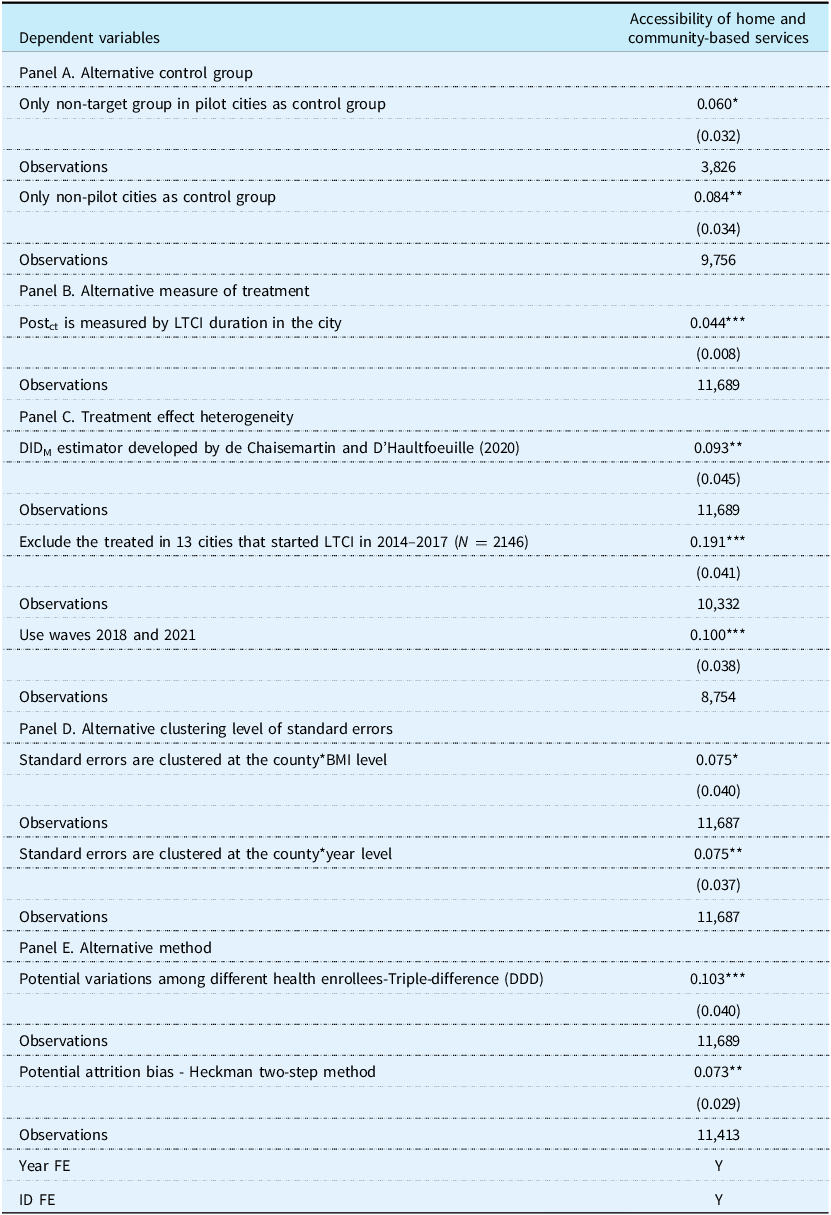

To ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted several tests using alternative specifications. Firstly, in Panel A of Table 3, we explored different control groups. To assess the potential impact of other policies in pilot cities such as financial subsidies for institutional care, we used non-target groups within pilot cities and residents of non-pilot cities as separate control groups. The findings in Panel A further corroborated our main estimates.

Table 3. Robustness checks using alternative specifications

Notes: All regressions control for individual and household covariates, as well as area-by-year covariates, as specified in Table 1. * p < .1; **p < .05; *** p < .01.

Secondly, we experimented with alternative measures of LTCI coverage for the variable Post ct . Specifically, we considered the duration of the LTCI program in a city as a continuous variable for Post ct . The results in Panel B of Table 3, which remained consistent across different measures, indicate that each additional year of LTCI coverage correlates with a 4.4-percentage-point increase in the likelihood of accessing HCBS.

We also addressed potential issues in DID analysis related to staggered treatment timings, as highlighted by Goodman-Bacon (Reference Goodman-Bacon2021). Our sample includes 13 pilot cities that implemented LTCI between 2014–2017 and 14 cities that did so between 2018–2022. Recognizing that treatment effects might vary across groups and time periods, we employed the DIDM estimator developed by De Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (Reference De Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille2020). This estimator is robust to heterogeneity in treatment effects across groups and time periods. The results in Panel C of Table 3, which are consistent with our primary results, showing the stability of our findings against such heterogeneity. Additionally, we excluded the treated sample from cities implementing LTCI during 2014–2017 or dropped the 2014 wave, resulting in a canonical DID specification. These results too remain consistent, further validating our conclusions.

Furthermore, we also varied the clustering level of the standard errors to test robustness. First, we clustered the standard errors at the LTCI implementation level, specifically at the level of the group covered by LTCI in pilot regions, defined by county*BMI (Basic medical insurance) type. Second, we clustered the standard errors at the county*year level, assuming that within a given county and year, there is correlation in the use of HCBS. The results, as shown in Panel D of Table 3, remained robust across these adjustments.

Additionally, concerns arise regarding the parallel trend assumption inherent in the DID specification, particularly due to potential variations in accessibility of HCBS among older adults covered by different health insurances. To address this, we followed Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Ma and Zhao2023) and employed a triple-difference (DDD) model. Specifically, we divided the control group into two segments: one comprising older adults from non-pilot areas, and the other encompassing non-participants of basic medical insurance in pilot areas. The results, as shown in Panel E of Table 3, remain robust.

Furthermore, to address potential attrition bias in the longitudinal survey, we employed Heckman’s sample selection model (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979). In the first stage, leveraging the random sampling design of CLHLS, we utilized respondent type (0 = follow-up respondents; 1 = newly added respondents) as an exogenous instrument variable (IV), along with baseline values of all explanatory variables, to predict continued participation in subsequent waves. Theoretically, whether respondents were first-time or repeat participants would affect their likelihood of being re-surveyed but should be uncorrelated with HCBS accessibility, satisfying the exclusion restriction. The first-stage probit regression yielded a coefficient of −0.761 (SE = 0.035, p < 0.01) for the IV. In the second stage, we incorporated the estimated inverse Mills ratio (IMR) into our main specification. As shown in Panel E of Table 3, the results remained robust after correcting for attrition bias. Notably, the IMR term was statistically insignificant at the 10% level, indicating that sample attrition posed minimal threats to our findings.

4.3. Heterogeneity

4.3.1. Heterogeneous effects by potential demand for home and community-based services

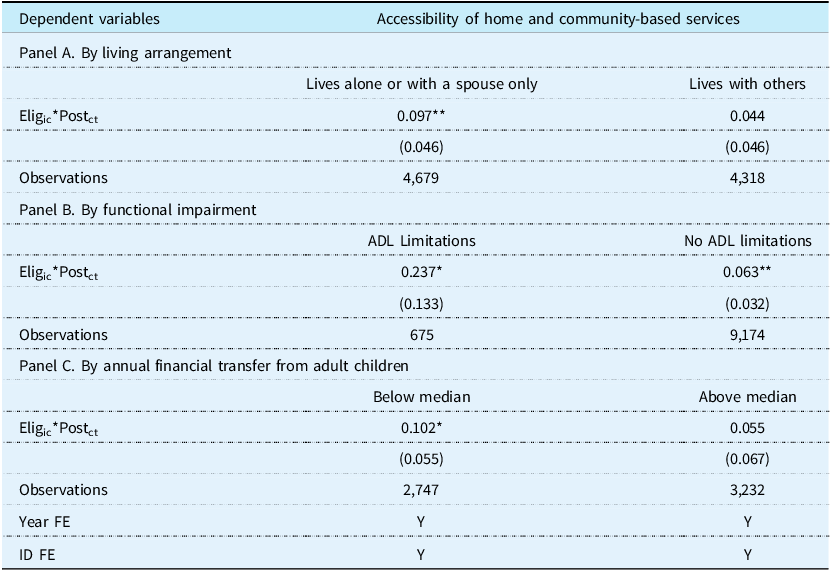

On the demand side, the impact of LTCI on the accessibility of HCBS could vary by service user characteristics. We observed a more pronounced effect of LTCI on the accessibility of HCBS among older adults with physical impairment, living alone or only with a spouse, or receiving lower financial transfers from their adult children. Older adults with higher levels of physical impairment typically demonstrate greater need for assistance with activities of daily living. When LTCI is available, eligibility assessments and benefit allocations often prioritize individuals with more severe functional limitations. This results in a higher probability that these older adults have increased access to HCBS. Meanwhile, older adults living alone or with a spouse only generally have less immediate informal support available for assistance with activities of daily living compared to those co-reside with more family members. These individuals rely more heavily on formal services to meet their care needs. When LTCI is available, older adults living alone or with a spouse only have greater accessibility to HCBS as these services fill a critical gap in their support system. In addition, when financial transfers from adult children are limited, older adults may have fewer resources to rely on formal services. LTCI can mitigate disparities in care access, ensuring that those without substantial financial support from family can still obtain essential HCBS.

Table 4 shows the relationship between LTCI and access to HCBS by living arrangements, functional impairment, and annual financial transfer from adult children. Panel A (“by living arrangement”) reveals that older adults either living alone or living only with their spouse experienced a statistically significant increase in HCBS access after the introduction of LTCI. The result is not statistically significant for older adults with other living arrangements. Panel B (“by functional impairment”) indicates that the benefits of LTCI on HCBS access are more pronounced for individuals with limitations in Activities of Daily Living (ADL). Panel C (“by annual financial transfer from adult children”) shows that older adults receiving few financial transfers exhibited a significant increase in HCBS access following the LTCI rollout, whereas this increase is not significant among those receiving more substantial intergenerational financial transfers. These results suggest that LTCI has a stronger positive effect on the accessibility of HCBS for vulnerable groups with higher needs.

Table 4. Heterogeneous effects of LTCI by potential demand for home and community-based services

Notes: All regressions control for individual and household covariates, as well as area-by-year covariates, as specified in Table 1. * p < .1; **p < .05; *** p < .01.

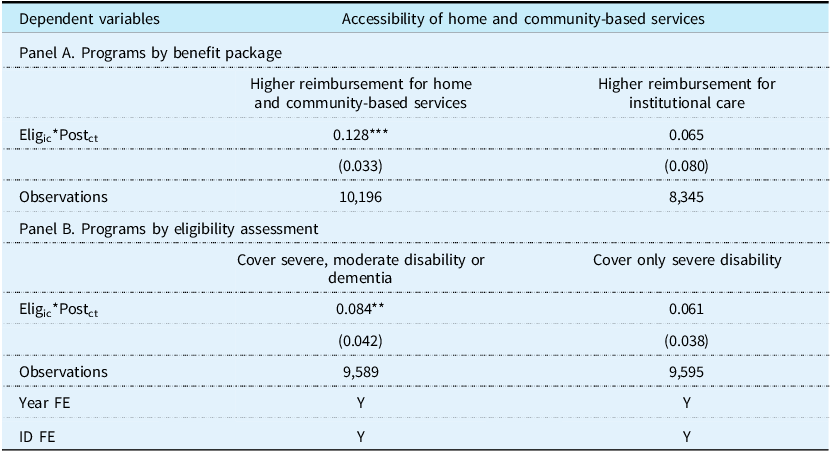

4.3.2. Heterogeneous effects by program design

LTCI has an impact on the accessibility of HCBS through offering direct benefits. The benefit package in terms of service coverage and expense reimbursement of LTCI varies across pilot cities and it includes subsidies to service providers and to service users. Pilot cities with higher reimbursement for HCBS and lower eligibility criteria might increase the affordability of HCBS and enable more older adults to have an access to these services.

We analyzed two key aspects of program designs of LTCI in pilot cities: LTCI reimbursement and eligibility. As expected, Panel A of Table 5 reveals a significant increase in HCBS accessibility in pilot cities where the compensation for HCBS are higher than institutional care after the introduction of LTCI. Panel B of Table 5 indicates that the impact of LTCI on HCBS is significant for pilot programs targeting individuals with moderate or severe physical impairment or dementia. However, the result is not significant for pilot programs which only covering older adults with severe disability. These findings support our hypothesis that the impact of LTCI on the accessibility of HCBS is more pronounced in programs with higher reimbursement for HCBS and more generous eligibility coverage.

Table 5. Heterogeneous effects of LTCI by program design

Notes: All regressions control for individual and household covariates, as well as area-by-year covariates, as specified in Table 1. * p < .1; **p < .05; *** p < .01.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Our study is among the first to evaluate the efficacy of LTCI pilot programs in enhancing the accessibility of HCBS. Analyzing three-wave CLHLS data using the DID approach, our findings suggest that LTCI significantly improves access to HCBS for older adults, particularly in personal daily care. In addition, LTCI is associated with a notable increase in psychological consulting and shopping services. The non-significant associations between LTCI and health education, social and recreation activities, and legal aid might be explained by that these services are not typically reimbursed by LTCI. Our findings suggest that LTCI has more salient impacts on the accessibility of HCBS which are reimbursed by LTCI.

Our findings demonstrate that older adults who were living alone, had physical impairments, and received fewer financial transfers benefited more from LTCI, indicating the program’s redistribution effect toward disadvantaged groups with limited care support as well as its effectiveness in addressing their critical care gaps. Existing research has found that LTCI significantly reduces unmet care needs among older adults and mitigates their perceived risks (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Bai, Hong and Liu2022; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma and Zhao2023). This is particularly important for older adults, who may require various types of support to live independently (Campbell and Ikegami, Reference Campbell and Ikegami2000). Individuals with ADL limitations inherently require more support and services to sustain their independence and quality of life. LTCI programs are designed to offer financial aid and facilitate access to a spectrum of institutionally based and non-institutionally based long-term services and support catering to the specific needs of individuals with functional impairment and increase their well-being. Therefore, the findings of this study may be attributed to LTCI’s dual mechanisms: directly reimbursing care costs while lowering financial barriers and reducing perceived risks among older adults, thereby enhancing the accessibility of HCBS and better meeting their demand for such services. From a supply-side perspective, LTCI may also enhance the accessibility of HCBS by stimulating market supply. Our findings reveal that beyond improving the availability of core personal daily care services - its primary function - LTCI has also demonstrated spillover effects by boosting other eldercare services that address the mental health and social needs of older adults. As a result, LTCI has significantly expanded the overall service supply in HCBS.

This study also reveals that the efficacy of LTCI is intricately linked to its program design, underscoring the significant role of program design in shaping policy outcomes. Specifically, programs emphasizing non-institutionally based care exhibit a more pronounced impact on the accessibility of HCBS. This suggests that aligning LTCI program design with the preference of older adults for home-based care is crucial to maximize the welfare benefits of LTCI for those aging at home; otherwise, the efficacy of the LTCI policy may be compromised. Additionally, by extending professional institutional services into communities, LTCI enables home-dwelling older adults to access professional services. Therefore, LTCI may enhance the accessibility of both HCBS and institutional care. These two approaches are complementary rather than contradictory, as older adults have varying care needs. LTCI pilot programs exclusively for severe disability demonstrate limited effectiveness, possibly owing to the heightened inclination towards institutional care among severely disabled older adults. In contrast, more generous programs demonstrate a greater capacity to address LTC risks (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma and Zhao2023).

Prior studies showed that LTCI effectively reduces informal family caregiving, alleviating informal caregiving burden and promoting older adults’ independence (Chen and Ning, Reference Chen and Ning2022b; Zhu and Bai, Reference Zhu and Bai2025). It may inadvertently create systemic challenges as diminished family support interacts with potentially inadequate social care capacity. This underscores the necessity for balanced public-family responsibility sharing, exemplified by the promising caregiver allowance initiatives implemented in LTCI pilot regions, which offer a replicable model to address these emerging care coordination challenges.

This study has theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical standpoint, first, it substantiates LTCI as a public good with pronounced redistributive effects. This study validates the fundamental tenets of public finance theory, particularly the postulation regarding governmental intervention in resource allocation and income redistribution through social insurance mechanisms (Colm and Musgrave, Reference Colm and Musgrave1960). Second, this study provides compelling evidence regarding the pivotal role of institutional design of LTCI in shaping older adults’ care-seeking behavior and system-level resource allocation. Specifically, our findings suggest that eligibility criteria and benefit packages can incentivize the use of HCBS, reduce overreliance on institutional settings, and promote a more equitable distribution of healthcare resources across the community. These insights highlight the importance of integrating behavioral and economic considerations into LTCI policy design, offering practical guidance for developing countries seeking to expand long-term care coverage while maintaining system efficiency and responsiveness to older adults’ diverse needs. These nuanced findings also align with welfare mixed theory (Evers, Reference Evers1995), which emphasizes the synergistic interdependence between state, market, family, and community in sustainable care systems.

This study carries two key policy implications. First, our findings demonstrate that LTCI effectively enhances access to HCBS, suggesting that it can help rebalance China’s current medical resource allocation, which disproportionately favors institutional care over home-based care, thereby extending healthcare resources to the community level. Moreover, the observed association between LTCI and accessibility of HCBS provides insights for the development of LTCI policies in other developing countries. Second, this study provides a nuanced explanation of the impact of LTCI on HCBS through a heterogeneity analysis. This is critical for policymakers, offering nuanced insights regarding the evaluation of differentiated pilot programs across cities which can inform a uniform national LTCI policy. Future studies could examine the downstream effects of LTCI on caregiver outcomes, quality of care, and long-term fiscal sustainability.

This study has several limitations. First, there was no information on actual LTCI beneficiaries. The impacts of LTCI on HCBS might be underestimated due to treatment noncompliance. Second, due to data limitation, we could not distinguish between the impacts of institutionally based and non-institutionally based care benefits and further assess the specific effects of LTCI on the accessibility of institutional care.

In summary, our research uncovers a notable enhancement in the physical accessibility of HCBS following the implementation of LTCI. Heterogeneity analyses indicate that LTCI has a stronger positive effect on the accessibility of HCBS for vulnerable groups with higher needs. Additionally, the positive effect is more salient in regions with higher reimbursement for HCBS and more generous coverage. Our findings could inform policymakers to develop a universal LTCI plan in China. Our study has policy implications for the development of public LTCI systems in middle-income and developing countries.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Bai was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72574226). Dr. Zhu was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2025WKQN010). Dr. Li was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72504277), Social Science Foundation of Beijing (No. 25BJ03057), and Renmin University of China (23XNF041).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure 1. Event study for the effect of LTCI on accessibility of home and community-based services.

Notes: The figure depicts coefficients and the 95 percent confidence intervals for an event study analysis. On the x-axis, number –1 is the omitted group and indicates one year before LTCI. The regressions control for individual and household covariates, as well as area-by-year covariates, as specified in Table 1.

Figure 2. Placebo test for the effect of LTCI on accessibility of home and community-based services.