[Y]oung black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.

(Hartman xv)Introduction

In the first few pages of the 1986 volume Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte (translated in 1992 as Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out), the twenty-six-year-old Black German writer and activist May Ayim indicated that the first depiction of a biracial character was in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, a medieval romance that Geraldine Heng also examined in The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages.Footnote 1 This was one of the early references of a biracial character in medieval literature but not the first. It was Parzival’s biracial half brother Feirefis whose skin appeared in a patchwork of black and white, marking his difference. Ayim recognized the romance as an example of medieval race-thinking and continued to explore European entanglements or “intimacies” (Lowe) with non-Europeans. As she writes,

Besonders die großen Handelshäuser Fugger, Welser und Imhoff finanzierten einige der ersten Flotten, die seit dem Mittelalter unter portugiesischer und spanischer Flagge Handel betrieben. Über diese Handelsbeziehungen kamen zunächst vor allem Gold, Elfenbein, Gewürze und andere Rohstoffe nach Europa; später wurden zunehmend auch Menschen als “Mitbringsel” nach Europa verschifft, die erhandelt oder als Pfand für die Einhaltung von Vertragsbestimmungen verschleppt wurden. (26)

The large trading houses of Fugger, Welser, and Imhoff, in particular, financed some of the first fleets that traded under Portuguese and Spanish flags from the Middle Ages onward. Initially, these trade expeditions primarily brought gold, ivory, spices, and other raw materials to Europe; later, people were increasingly shipped to Europe as “souvenirs,” acquired through trade or kidnapping as collateral for the fulfillment of treaty agreements.Footnote 2

Ayim thus demonstrated the interconnectedness of medieval European countries, especially since they funded the transatlantic slave trade. In many ways, she validated Cedric Robinson’s concept of “racial capitalism” in Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Critiquing Marx in his critical 1983 book, Robinson defined racial capitalism, arguing that as “[t]he development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology. As a material force, then, it could be expected that racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism” (2). He linked racial capitalism to European feudalism and noted that “from its very beginnings, this European civilization, containing racial, tribal, linguistic, and regional particularities, was constructed on antagonistic differences” (10).Footnote 3 In other words, slavery, imperialism, dispossession, violence, and genocide undergirded European capitalist endeavors from the medieval period to postmedieval periods.

Additionally, Ayim pens,

Ich konnte nirgends Zahlen finden, wie viele Schwarze zur Zeit des Mittelalters in Deutschland lebten. In der Hauptstadt Portugals waren Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts ein Zehntel der Bevölkerung schwarze Sklaven, und wie in Frankreich und England gehörte es wohl auch in Deutschland—wenn auch weniger verbreitet—zum “guten Ton,” “in seiner Equipage in seiner Karosse, in seinem Salon und in seinem Pferdestall solch eine exotische Figur zu haben.” (26)

I couldn’t find any figures anywhere on how many Black [Schwarze] people lived in Germany during the Middle Ages. In the mid–sixteenth century, one-tenth of the population in the Portuguese capital were enslaved Black people, and, as in France and England, it was probably also considered “good form” in Germany—albeit less widespread—“to have such an exotic figure in one’s horse-drawn carriage, coach, parlor, and stable.”

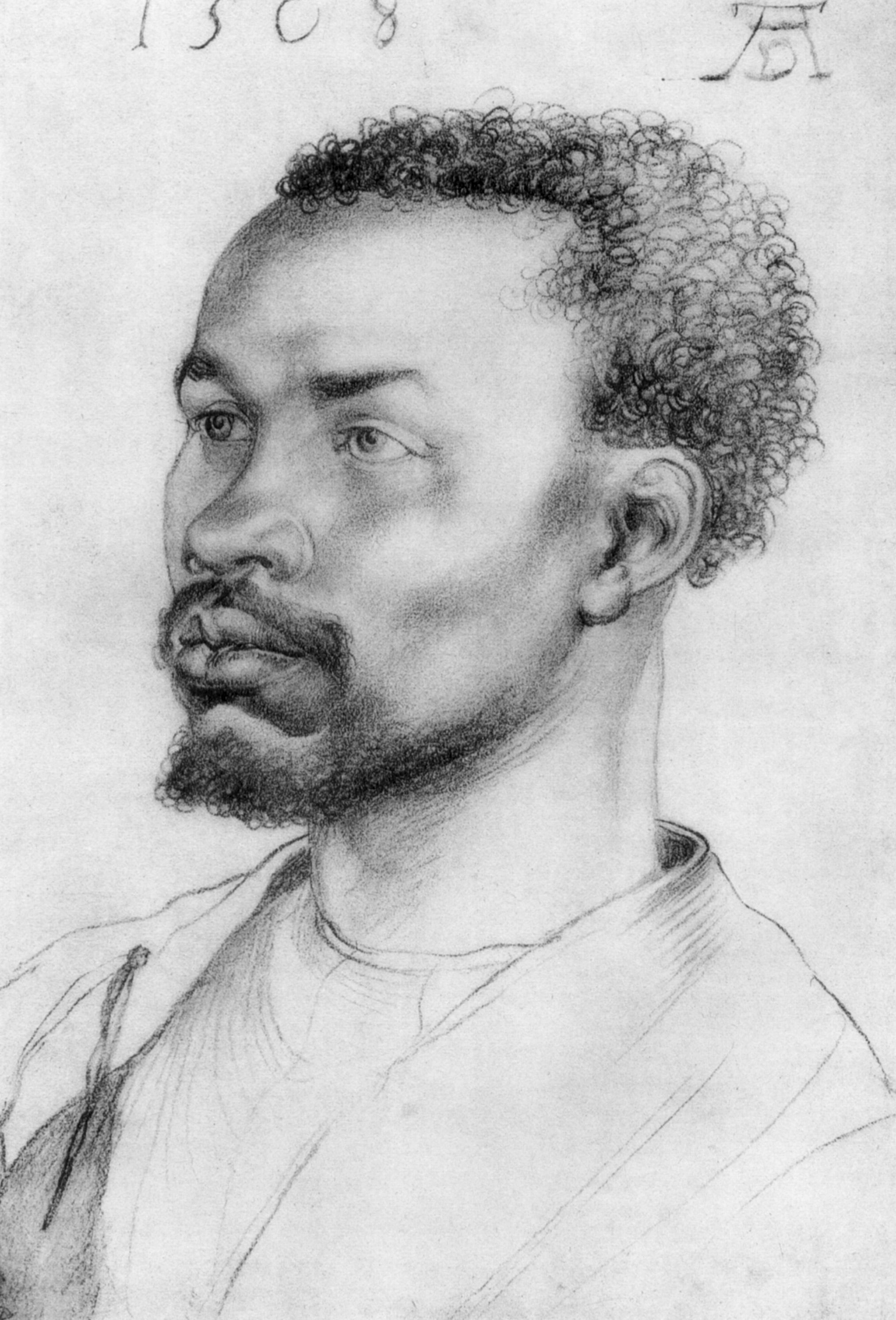

On the adjacent page, there is a reproduction of Porträt eines Äthiopiers (1508; Portrait of an Ethiopian; fig. 1), painted by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). The painting featured a man of African descent, who was “der als Angestellter in einem der großen Handelshäsuer Augsburgs tätig war” (“an employee in one of the largest trading firms in Augsburg”; 25). Her inclusion of (and later analysis of) art history in the volume, especially with discussions of the depiction of one of the three magi from the Bible as Black, reinforced the idea that a Black diaspora already existed in the German Middle Ages.

Fig. 1. Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of an Ethiopian, at the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Austria. Image courtesy of WikiArt.org, www.wikiart.org/en/albrecht-durer/head-of-an-african.

On those first few pages, Ayim offered a brief entry point into the European Middle Ages, alerting readers to the presence of people of African descent in Europe. By so doing, she recovered the medieval past to impart an important lesson that echoed the Sri Lankan Tamil and British writer and activist Ambalavaner Sivanandan’s aphorism, “We are here because you were there,” drawn from his 1983 speech “Challenging Racism: Strategies for the ’80s.”Footnote 4 Ayim knew that medieval Europe had never been a raceless continent, because its early explorations and expeditions, as well as the slave trade, brought African diasporic people to the continent. Ayim confirms Heng’s claims that the Middle Ages were “the time of race, as racial time” and that “the refusal of race destigmatizes the impacts and consequences of certain laws, acts, practices, and institutions in the medieval period, so that we cannot name them for what they are, makes it impossible to bear adequate witness to the full meaning of the manifestations and phenomena they install” (18, 23). In the process, Ayim’s intellectual work certainly illuminated more than it obscured because she countered the years of historical erasure and forgetting of the Black diaspora in Europe while also offering new epistemic practices.

Ayim’s early intervention is a critical one, especially as she excavated this history in the 1980s while conducting research for her bachelor’s thesis in education at the University of Regensburg. Her thesis served as a foundation for Farbe bekennen, which also included interviews, poetry, and personal narratives of a multigenerational group of Black German women and catalyzed a Black German diasporic movement that continues to exist today (El-Tayeb 43–80; Florvil, Mobilizing 103–13). Ayim wrote it before Martin Bernal’s first volume in his Black Athena trilogy, in which he posited that classical civilization had roots in Afro-Asiatic cultures. Ayim’s intellectual endeavor, moreover, was striking because she challenged the work of scholars such as Sander Gilman, who erroneously claimed that Germany had “Blackness without Blacks.” Ayim produced research that recuperated Black and diasporic pasts in Germany until her untimely death in 1996 at the age of thirty-six. In fact, Ayim sought to revise German and European narratives of world history. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, white European men presumed that world history unfolded rationally and teleologically because of Europe’s superior progress, culture, and development. It also remained crucial for her to redress the claims of pastlessness that Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and his contemporaries made about peoples from Africa and to demonstrate how intellectual and historical the continent and its diaspora truly were. Ayim follows the philosopher Susan Buck-Morss in rejecting what Buck-Morss calls “Hegel’s systematized comprehension of the past” and “Heidegger’s ontological claim that historicality is the essence of being” (x). With her diverse forms of writing and her public presentations, Ayim sought epistemic change and imparted knowledge about the complexity of Black people.

In this spirit, I use this piece to offer my own reflections on Ayim’s oeuvre. Although white and some Black German compatriots have regarded Ayim as only an activist who played a key role in establishing a Black German civil rights movement in the 1980s and 1990s, her intellectual thought and labor in and beyond the movement have been mostly ignored and overlooked in mainstream German academic and literary circles. While there have been recent reissues of her poetry and essays from the left-leaning press Unrast, these developments have not generated more mainstream acclaim for her in Germany. Elsewhere, I have written that her poetics, as well as her academic and nonacademic work, served as a form of “wake work” (“May Ayim’s ‘Wake Work’”), in which she retrieved narratives of Black diasporic ancestors from the past and made them legible in the present. Ayim’s wake work “excavated a long-ignored Black history and addressed the on-going valences of colonialism’s afterlives in Germany” (448). She recognized that race-making was also a premodern practice—an intellectual intervention that has not garnered any scholarly attention to date. Thus, it is time that she is recognized as a young Black “radical thinker” who studied the contours of race across different times and spaces in Europe.

Ayim’s Understanding of Medieval European Language

As a modern German historian by training and a scholar of Black German studies by choice, I have been reading and rereading Farbe bekennen for over twenty years now. Yet each time I open it, I discover something anew. It was during a recent rereading that I recognized Ayim’s early efforts to excavate a premodern history of Blackness with Blacks in Germany and, by extension, in Europe. Curiously, she pursued this work in the 1980s and 1990s, but scholars of medieval studies and history, such as Robert Barlett, Robert Greary, and Bernard Bachrach, have not engaged with her. Much like Robinson and Sylvia Wynter, whose works have often been ignored by Europeanists, Ayim recovered instances of race-making as well as processes of racialization in medieval Germany. So, in many ways, her early intervention helped initiate discussions about premodern race. Though she did this work within German academia, she received limited to no support from professors, who discouraged her from writing on this topic in 1984 because they claimed that racism was a problem only in South Africa or the United States. Ayim pursued this research in a German climate that perceived itself to be progressive and tolerant. The defeat of the Third Reich led to a national silencing of debates on race or racism on both sides of the Cold War divide. During the postwar period, East and West Germany clung to their own myths of antiracism and equality that the governments had codified in law in 1949.

Moreover, Ayim’s work not only interrogated the past but also demonstrated that language, like nineteenth-century Rankean empiricism, was not objective or value free. In a Foucauldian sense, she understood that language was tied to power and knowledge and that power reproduced knowledge. Ayim observed how language helped construct specific medieval realities (and imaginaries) for majority European and minority non-European populations. For her, studying the German language opened a space where one could observe premodern racial and historical changes that influenced linguistics. In addition, studying language and culture enabled Ayim to renounce Black Germans’ nonexistence (or nonhumanness) and counteract minoritized communities’ marginalization while also removing the cloak of invisibility German society imposed on them. She furthered this work in her 1990 speech therapy thesis, entitled “Ethnozentrismus und Geschlechterrollenstereotype in der Logopädie: Eine kritische Betrachung von Bildund Wortmaterialien mit Verbesserungvorschlägen für die Logopädische Praxis” (“Ethnocentrism and Gender Role Stereotypes in Speech Therapy: A Critical Consideration of Picture and Word Materials with Suggestions for Improvement in Specialist Practice”), at the Freie Universität Berlin. She shared in Farbe bekennen, for instance, that “[d]ie sprachlichen Veränderungen im Gebrauch der Bezeichnungen ‘M***’ und ‘N****’ spiegeln den Wandel der deutschen bzw. europäischen Beziehungen zu Afrika” (“the linguistic changes in the use of the terms ‘M***’ and ‘N****’ mirror the changes in German and European relations, respectively, with Africa”; 28).Footnote 5

She further explicated that

“M***” ist die älteste deutsche Bezeichnung für Menschen anderer Hautfarbe und diente im Hochmittelalter zur Unterscheidung der schwarzen und weißen Heiden. Mor, aus dem lateinischen Mauri, erhielt seine Prägung durch die Auseinandersetzung zwischen Christen und Moslems in Nordafrika. Physische Andersartigkeit und fremde Glaubensvorstellungen charakterisieren somit diesen Begriff. (28)

“M***” is the oldest German term for people with a different skin color and was used during the high Middle Ages to differentiate between Black and white pagans. Mor, from the Latin mauri, was coined because of the conflict between Christians and Muslims in North Africa. Thus, it was physical difference and foreign religious beliefs that characterized this concept.

Ayim demonstrated that medieval Europeans interlinked race and religion, denoting Black as different or “other” from white and Christian. In this way, she laid bare what Heng explained in The Invention of Race:

Race-making thus operates as specific historical occasions in which strategic essentialisms are posited and assigned through a variety of practices and pressures, so as to construct a hierarchy of peoples for differential treatment. My understanding, thus, is that race is a structural relationship for the articulation and management of human differences, rather than a substantive content. (27)

Europeans’ “management of human differences” was predicated on the construction of boundaries of inclusion and exclusion in medieval society. Oftentimes, those European exclusionary practices revolved around commonplace usages that made Egyptian “als Synonym für Teufel” (“a synonym for the devil”; Ayim 28) and black as a descriptor for witches. With each example, the devil and witches were considered “Schwarz, hässlich und ohne gute Manieren, ein ‘ungehuire’” (“black [or evil], ugly, ill-mannered, and a ‘monster’”; 29). Moreover, Ayim noted that Blackness was depicted as the exact opposite of the medieval norm of whiteness. Drawing from “Wolfdietrich’s Saga,” an anonymous Middle High German heroic epic written around 1230, Ayim used the poem to illustrate how common this practice was. She utilizes the version of “Wolfdietrich’s Saga” that appeared in Gilman’s 1982 book. Ayim wrote:

Ain ungefuge fraw geporn von wilder art, Ging uff für alle paume: kain grosser wip nie wart Da dacht in sinem synne der edel rytter gut:

“O werder Christ von himel, hab mich in diner hut!”

Zwu ungefuge bruste an irem üb si trug.

“Wem du nu wurst taile,” so sprach der rytter klug

“Der hat des tufels muter, das darff ich sprechen wol.”

Ir lip der waz geschaffen noh schwarczer dann ein kol,

Irn nas ging für daz kine, lanck, schwarcz so waz ir har. (29)

A monstrous woman, born in the wild, came toward him through the trees. There was never a bigger woman. The noble knight thought to himself: “O dear Christ, protect me!” Two monstrous breasts hung from her body. “Whoever gets you,” the wise knight spoke, “gets the devil’s mother, I do believe.” Her body was created blacker than coal. Her nose hung over her chin; long and black was her hair…. (Optiz 5)

After citing the passage, she explicated that

[d]ie wilde Frau, die aus den Wäldern (“für alle paume”) auf den edlen Ritter zugeht, bedroht diesen durch ihre unermessliche Größe, die durch ihre überdimensionalen (“ungefuge”) Brüste hervorgehoben wird. Der Ritter bittet in seiner Not Gott um Schultz, denn er glaubt an den Lippen, die noch schwärzer sind dals Kohle, der Nase, die weit über das Kinn hängt, und den langen schwarzen Haaren die eindeutigen Merkmale der Mutter des Teufels (des “tufels mutter”) zu erkennen. (Ayim 29)

the monstrous woman who approaches the noble knight in the woods (“lost through the trees”) frightens him with her immense size and through her oversized (“monstrous”) breasts. In his distress, the knight prays to God for protection, recognizing that her lips, which are blacker than coal, her nose that hangs far over her chin, and her long black hair are unmistakable characteristics of the mother of the devil (the “devil’s mother”).

Revealing the religious undertones of the epic, Ayim indicated that the knight’s unspoken (yet assumed) whiteness was indexed to piety. The large ugly woman did not represent virtue. Rather, she was a devilish woman emerging from the trees or the wild and causing the knight harm with her dreadful appearance. The juxtaposition of light (the unspoken whiteness of the knight) and dark (the witch or monstrous woman) reinforced the epic’s meaning, which positioned Blackness as the antithesis to whiteness.

Certainly, Ayim’s usage of this medieval example bolsters Christina Sharpe’s concept of “monstrous intimacies.” Monstrous intimacies were essentially “those subjectivities constituted from transatlantic slavery onward and connected, then as now, by the everyday mundane horrors that aren’t acknowledged to be horrors” and are “a set of known and unknown performances and inhabited horrors, desires, and positions produced, reproduced, circulated, and transmitted, that are breathed in like air and often unacknowledged to be monstrous” (Monstrous Intimacies 3). Ayim shared the monstrous intimacies that pervaded medieval Germany, which normalized monstrous Blackness in the quotidian. Through the anonymous poem, she emphasized that the Western and European system structured ontological claims that contributed to the negation of Blackness that prevailed not only in the medieval period but also in later centuries.

In her research Ayim showed that

[i]n der christlichen Farbensymbolik verkörpert “schwarz” den Inbegriff des Unerwünschten, somit Hässlichen und Verwerflichen. Religiös motivierte Vorurteile konnten daher schnell dazu führen, im schwarzen Menschen, der/die den eigenen christlich-patrarchalischen Vorstellungen entgegentrat, den Prototyp des “Bösewichts” zu sehen, was sich in der Projektion von schwarzer Hautfarbe auf Weiße ja bereits andeutet. (Ayim 29)

in Christian color symbolism [christlichen Farbensymbolik], “black” embodies the epitome of the undesirable, thus ugly and reprehensible. Religiously motivated prejudices therefore quickly propagated negative views of black people linking them to their own Christian-patriarchal ideas of the prototype of the “evil villain,” which already hinted at the projection of black skin color onto white people.

She emphasized European medieval processes of race-thinking, race-making, and boundary-making in poetry and stressed how medieval epics and medieval poetics presented seemingly entrenched cultural and political ideas about belonging and unbelonging. In this way, language had the power to shape both fictionalized and real-life medieval accounts. Ayim shared Heng’s belief “that a hierarchal politics of color, centering with precision on the polarity of black and white, existed and is in evidence across the multitude of texts and artifacts, sacred and secular, that descend to us” (42). Ayim’s intellectual contributions broke with the image of a preracial white Middle Ages that underpinned late-twentieth-century medieval scholarship. Instead, she created work that complemented her activism by exposing the myths of “white innocence” (Wekker) in Germany’spast and present.

Quotidian Intellectuals on the Move

I examined her intellectual work within and beyond Germany in my 2020 book, Mobilizing Black Germany: Afro-German Women and the Making of a Transnational Movement, and its 2023 German translation, Black Germany: Schwarz, Deutsch, Feministisch-die Geschichte einer Bewegung. I maintained that Ayim and her Black German compatriots were quotidian intellectuals “who thought, theorized, wrote, performed, and circulated their ideas and knowledge textually, visually, or orally through publications, workshops, conferences, presentations, and other artistic forms in the public sphere” (Mobilizing 6). I argued that quotidian intellectuals, a concept I coined,

opened other sites for knowledge production and circulation. In both their content and form, Black Germans brought everyday experiences of discrimination to the forefront. They used vernacular cultural forms to destabilize the power of dominant knowledge and representation, to establish the field of Black German studies (BGS), and to bring intellectual and academic inquiry to BGS through their publications and events, countering their archival erasure. (6)

Black German quotidian intellectuals were not connected to Karl Marx’s historical materialist tradition, nor were they like Antonio Gramsci’s organic intellectuals (187n26). They produced work that often existed beyond the traditional German academy and the scholarly channels of knowledge production. Indeed, these quotidian intellectuals created and disseminated knowledge through their collectives, magazines, exhibitions, poems, speeches, and edited volumes, which often remained on the margins of German society. Black Germans’ intellectual work established that the synthesis of theory and practice was achievable in everyday life.

Undeniably, Ayim was a quotidian intellectual par excellence who saw how entrenched white European empiricism was in obscuring the role of people of African descent in European history. And like Ayim, who sought to expose the erasure of the contributions of Black peoples in a European context, I recovered her by demonstrating her own critical contributions to intellectualism. Her early research and writing in Farbe bekennen, in particular, proved that she understood the importance of the European Middle Ages as a site for demarcating difference and advancing forms of exclusion. Ayim’s subsequent essays and presentations in Germany and elsewhere indicated that intellectual work could be accomplished on and in the quotidian.Footnote 6

Internationally, she made a critical mark that readily appealed to scholars of German in the North American academy as well as to writers and researchers in cultural centers. Through Farbe bekennen’s English translation and her networks with many across the Black diaspora, including Dionne Brand, Maryse Condé, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Audre Lorde, she gained more visibility.Footnote 7 In Germany, especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall, her profile rose. Ayim garnered invitations to present and contribute to edited volumes on intersectionality, racism, and Black German ethnic minorities. With the publication of her first poetry volume, blues schwarz-weiß (blues black-white) in 1995, she increasingly gained attention. Ayim also knew that her audience included not only white and Black Germans but other people of color and white communities across the globe who remained clueless about Germany’s Black diaspora.

Thus, Ayim’s written work and activism “allowed Black Germans to enter the public sphere” (Florvil, Mobilizing 6). Together with her compatriots, they “remade the public sphere, typically an exclusionary site, a Black space that did not ignore or bracket racial difference” (148). Her knowledge production challenged white European empiricism and epistemologies as well as the claims of pastlessness that aimed to minimize the presence and contributions of Africans and Black diasporic communities. Ayim’s act of recovery, moreover, entailed intellectual labor and enabled her to rewrite and unsilence Germany’s historical past, which also represented her past. “For what history is changes with time and place,” as Michel-Rolph Trouillot argued in Silencing the Past,

or, better said, history reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives. Only a focus on that process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others. (25)

Indeed, Ayim’s act of storytelling, historical retrieval, and knowledge-making were powerful interventions in a late postwar, post-Holocaust, and later post-Wende Germany.

Yet Ayim created a tension in Farbe bekennen, hewing to the Martinican theorist Frantz Fanon’s idea of an “epidermal racial schema” as a modern invention in the postmedieval world (Black Skin 92). She claimed that “[b]is zum 18. Jahrhundert waren Vorurteile gegen Schwarze weitgehend frei von Vorstellungen über die Existenz unterschiedlicher Rassen. Erst im Zeitalter der Aufklärung vollzog sich ein deutlicher Wandel, der mit der raschen Kolonialisierung der afrikanischen Länder südlich der Sahara einherging” (“until the eighteenth century, prejudices against black people were largely free of ideas about the existence of difference races. It was only in the Age of Enlightenment that a German transformation occurred, which coincided with the rapid colonization of sub-Saharan African countries”; Ayim 29). Ayim dismissed the possibility that race was a specific referential point for difference in medieval thinking while simultaneously demonstrating that it was. Once again, she used language to depict the transformation of terms and meanings. Ayim noted:

Im 18. Jahrhundert wurde “N****” zu einem deutschen Begriff. In Ergänzung und Ablösung der Bezeichnung “M***” wurde zur Beschreibung der Menschen südlich der Sahara verwandt und diente “darüber hinaus zur Bezeichnung der schwarzen Rasse schlechthin.” Während mit “M***” keine Unterscheidgung in hellere und dunklere Afrikaner vorgenommen wurde implizierte die neue Bezeichnung die ideologische Trennung Afrikas in einen weißen und einen schwarzen Erdteil mit der zunehmenden Kolonialisierung des Kontinentes. (30)

In the eighteenth century, “N****” became a German term. Complementing and replacing the term “M***,” it was used to describe people South of the Sahara and, “moreover, to designate the black race for all intents and purposes.”Footnote 8 While employing M*** as a concept, medieval Germans did not even bother to discern between dark- and light-skinned Africans. The new term [N****] reflected an ideological shift that helped Europeans divide Africa into different chromatics of white and black with the increasing colonization of the continent.

This constructed color schema strengthened Europeans’ claims of superiority and justified their dominance. It is unsurprising that this ideological shift helped sustain European settler colonialism and imperialism.

Citing Fanon, Ayim acknowledged the moment that “Schwarze Afrika” (“Black Africa”) was fully constituted, and it was “bezeichnet man als eine träge, brutal, unzivilisierte –eine wilde Gegend” (“described as sluggish, brutal, uncivilized—a wild region”; Fanon, Die Verdammten 138). To this extent, she wrote, “‘N****’ (aus dem lat. Niger=schwarz) wurde im Laufe kolonialer Ausbeutung, Versklavung und Fremdbestimmung zu einem ausgesprochen negativen Etikett” (“‘N****’ (from the Latin niger = black) definitely became a negative label through the course of colonial exploitation, slavery, and foreign domination”; Ayim 30).Footnote 9 The categorization of the continent also advanced the idea that it was pastless and therefore needed Europe’s civilizing mission. With the negative connotation of N****, Europeans linked physical, intellectual, and cultural characteristics. During Africa’s violent encounter with the West, Europe controlled Africa, allowing it to potentially enter world history. Ayim recognized the differences between the past and present and proved how the past was never past. She used Germany’s past (or history) to make sense of its present and future conditions. As a quotidian intellectual, Ayim utilized her research, writing, presentations, and activism to illuminate the contributions of people of African descent and expose centuries of racism in Germany and Europe.

Later in Farbe bekennen and subsequent academic and nonacademic work, Ayim continued to analyze race and gender, as well as minoritized communities and the Black diaspora in Germany, from the colonial period to post-1945 periods. By doing so, she offered historical context that positioned people of African descent in the metropole and in the colonial peripheries, demonstrating the permeability of European borders. Ayim’s intellectual work affirmed that one did not need to acquire traditional “scientific” training to produce history.

Farbe bekennen reflects the academic tensions about race in the premodern and modern periods and offers insights into Ayim’s own thought processes. She grasped, on the one hand, that the premodern period was a site that included differentiation by color (black and white). On the other hand, she was attached to Fanon’s epidermal schema of the modern world. But these were two sides of the same coin. Ayim allowed those contradictions to sit next to each other, which represented the messiness of her own thinking. She also did not shy away from retrieving other legacies of Blackness “in the wake” (Sharpe). While Farbe bekennen was the beginning of her intellectual journey, her quotidian intellectualism achieved an afterlife in the ashes of Africa’s pastlessness, Europe’s racelessness, and Germany’s antiracism.

The afterlives of medieval race and race-making are evident in the current European landscape, which includes heightened ethnonationalism, racism, anti-Semitism, and neofascism. The previous practices of medieval racialization, indeed, have evolved to fit the modern discourses of right-wing parties, especially Alternativ für Deustchland (Alternative for Germany), or AfD. AfD is now the largest opposition political group in the parliament or Bundestag, and they have achieved more support by bolstering antimigrant sentiment and claiming that Islam is incompatible with German democracy. Yet AfD is not alone in espousing this rhetoric. Green Party leaders and other left-leaning groups have also appropriated the far right’s arguments against migration, continuing to shatter the myth of German antiracism, a myth that Ayim already helped challenge in her activism and intellectual work. Because of all her critical intellectual labor, I urge scholars to observe Ayimism as a form of critical thought (just like Kantian or Hegelian thought) and use it as a form of epistemic liberation. Once we obtain epistemic liberation, we too can become “radical thinkers who timelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise” (Hartman xv).