Impact statement

The world is rapidly changing due to land use intensification, climate change and ongoing globalization. These changes are driving the emergence of novel ecosystems composed of native and introduced organisms, which are likely to expand as species migrate in response to changing environmental conditions. Many of these introduced organisms are threatened or extinct in their native ranges, and all of them are evolving. The possibility that these systems and these organisms may have conservation value is highly contentious for both empirical and normative reasons. We here present a series of questions to help guide critical thinking in both empirical and normative domains. This perspective aims to foster good-faith discussion around what we consider to be among the most salient challenges facing conservation in our modern world.

Introduction

For hundreds of thousands of years, camels (Camelus spp.) roamed Eurasia and northern Africa alongside straight-tusked elephants, Stephanorhinus rhinos, equids and large bovids. In North America, two to three species of wild equid, including modern horses (Equus ferus), grazed alongside mammoths and ground sloths. Rich megafauna communities were the norm on all continents for 50–30 million years until 50,000–12,000 years ago. The extinction of these large animals as humans spread from Africa appears to be one of the earliest human effects on the global biosphere (Svenning et al., Reference Svenning, Lemoine, Bergman, Buitenwerf, le Roux, Lundgren, Mungi and Pedersen2024).

However, relationships between humans and nonhumans are complex. Some of the populations that went ‘extinct’ were later spread around the world in domesticated form, where they subsequently went ‘feral’ (Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Ramp, Ripple and Wallach2018) – a form of spontaneous rewilding. From this, feral horses (E. ferus) have returned to North America, and the world’s only wild population of dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) roam in central Australia, a landscape recently populated by hippo-sized migratory diprotodons, giant wombats and horse-like short-faced kangaroos (Prideaux et al., Reference Prideaux, Ayliffe, DeSantis, Schubert, Murray, Gagan and Cerling2009; Price et al., Reference Price, Ferguson, Webb, Feng, Higgins, Nguyen, Zhao, Joannes-Boyau and Louys2017; Faurby et al., Reference Faurby, Davis, Pedersen, Schowanek, Antonelli and Svenning2018). If feral camels were to be eradicated from Australia, where many biologists consider them to be ‘invasive’ species, we would make another species extinct in the wild.

Overall, 50% of introduced megafauna (>100 kg body mass) are threatened or extinct in their native ranges (Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Ramp, Ripple and Wallach2018); 22% of all introduced mammals are threatened in their native ranges (Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Wallach, Svenning, Schlaepfer, Andersson and Ramp2024b); 27% of introduced plants are threatened in at least part of their native range (Staude et al., Reference Staude, Grenié, Thomas, Kühn, Zizka, Golivets, Ledger and Méndez2025); and many birds and herpetofauna have found refuge through introductions (Gibson and Yong, Reference Gibson and Yong2017; Figure 1). What if conservationists were to value at least some of these introduced populations of threatened species?

Figure 1. Many introduced organisms are threatened in their native ranges. These organisms present conservation paradoxes that can only be navigated with critical thinking in empirical and normative dimensions. (A) The world’s only population of wild dromedary camels roam in central Australia (extinct in the wild, not listed on the IUCN Red List). (B) Rusa deer (Rusa timorensis, vulnerable in their native range) have established populations in eastern Australia (Wallach et al., Reference Wallach, Lundgren, Ripple and Ramp2018b); (C) yellow-crested cockatoos (Cacatua sulphurea, critically endangered) are thriving in Hong Kong (Andersson, Reference Andersson2023); (D) Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus, vulnerable) are considered one of the worst ‘invasive’ species in Florida (IUCN, 2018); (E) cardboard cycad (Zamia furfuracea, endangered) is widespread in Florida; and (F) Angel’s trumpet (Brugmansia suaveolens) is extinct in the wild but has established wild introduced populations globally. A–F: ©ADW; ©https://animalia.bio/; ©Astrid Andersson; ©https://animalia.bio/; ©Jens-Christian Svenning; ©Scott Hecker.

These paradoxes are not outliers but are increasingly likely to become a core feature of twenty-first century conservation. The world is continuing to change in dramatic ways as humans continue to alter landscapes, global climate and the chemical composition of the environment (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Ordonez, Riede, Atkinson, Pearce, Sykut, Trepel and Svenning2025). Are current conservation paradigms sufficient to make pragmatic and conscientious decisions that can prevent extinctions and protect complex and diverse ecosystems?

Including introduced organisms under the umbrella of conservation care is one of the most contentious questions in conservation biology. Yet, we believe it is one of the most essential to wrestle with – on empirical and normative grounds – in order to prepare conservation for a radically novel future (Schlaepfer and Lawler, Reference Schlaepfer and Lawler2023).

While many of us recently proposed and conducted simulations of how conservation may prevent extinctions by accounting for introduced populations (Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Wallach, Svenning, Schlaepfer, Andersson and Ramp2024b), these matters require case-by-case decision-making that considers both global conservation aims (e.g., preventing extinctions) and local conservation concerns (e.g., the effects of the introduced organism). Moreover, as we will describe below, these decisions require attention to both empirical data and normative values for how the world ought to be.

We here present a series of questions to help reconcile the contradictions – and opportunities – presented by introduced species in an age of species reshuffling and extinction. These questions are meant to help guide conservationists and ecologists in critically thinking about the effects of introduced organisms and how valuing some introduced populations may assist with global efforts to prevent extinction.

When is nativeness empirically measurable?

The core functional postulate underlying conservation’s concern with the effects of introduced organisms was articulated by Michael Soulé (Reference Soulé1985), when he wrote, ‘many of the species that constitute natural communities are the products of coevolutionary processes’. According to this hypothesis, introduced species sever the long-term coevolved relationships between native species, leading to chain reactions that unravel ecosystems. This notion has become central to conservation thought (Rejmánek and Simberloff, Reference Rejmánek and Simberloff2017; Pauchard et al., Reference Pauchard, Meyerson, Bacher, Blackburn, Brundu, Cadotte, Courchamp, Essl, Genovesi, Haider, Holmes, Hulme, Jeschke, Lockwood, Novoa, Nuñez, Peltzer, Pyšek, Richardson, Simberloff, Smith, van Wilgen, Vilà, Wilson, Winter and Zenni2018).

While there is evidence that some introduced species have prospered, at least on short timescales, because of coevolutionary mismatches (e.g., Shine, Reference Shine2010; Brian and Catford, Reference Brian and Catford2023), there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the importance of long-term coevolutionary history in shaping ecological interactions. Even specialized interactions can emerge simply from ecological fitting (Janzen, Reference Janzen1985; Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2004); dominant coevolutionary hypotheses in invasion biology have mixed and declining support (Jeschke et al., Reference Jeschke, Gómez Aparicio, Haider, Heger, Lortie, Pyšek and Strayer2012); and considerable evidence indicates that (co)evolution can occur on rapid, ecologically relevant timescales, even among large vertebrates – suggesting that (co)evolution is a more dynamic force in ecology than typically considered (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Loye, Dingle, Mathieson, Famula and Zalucki2005; Cattau et al., Reference Cattau, Fletcher, Kimball, Miller and Kitchens2018; Singer and Parmesan, Reference Singer and Parmesan2018; Campbell-Staton et al., Reference Campbell-Staton, Arnold, Gonçalves, Granli, Poole, Long and Pringle2021).

However, the primary evidence used to argue for the ‘harmfulness’ of introduced species does not stem from studies of (co)evolutionary mismatches but from the negative effects of introduced species on native species. For instance, the 2023 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) review of over 30,000 peer-reviewed articles and copious gray literature found that 85% of the effects of introduced species were negative for native species (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Pauchard, Stoett and Renard Truong2024). At first glance, numbers like this seem indisputable. However, these numbers can be easily misinterpreted because they lack a proper null comparison: the effects of similar native species (Sagoff, Reference Sagoff2020).

Ecosystems are built from ‘negative’ interactions: Native predators reduce the abundance of their prey, native herbivores reduce the abundance of their preferred plants, native plants take up space that could have been used by other native plants and so on (Estes et al., Reference Estes, Terborgh, Brashares, Power, Berger, Bond, Carpenter, Essington, Holt, JBC, Marquis, Oksanen, Oksanen, Paine, Pikitch, Ripple, Sandin, Scheffer, Schoener, Shurin, ARE, Soulé, Virtanen and Wardle2011). Finding that introduced species reduce the abundance of their food sources or of their competitors, or take up space, only proves that they are alive.

To understand whether the effects of introduced organisms are due to their nativeness per se, one must compare their effects to similar native organisms, while controlling for relevant confounding variables (Figure 2). In other words, could an extraterrestrial ecologist determine which species was native and which introduced from their measurable impacts alone (Brown and Sax, Reference Brown and Sax2005)? Without a proper null comparison, tabulations of the effects of introduced species are insufficient to make any inference about the importance of (non-)nativeness itself and only serve as evidence that the introduced organism exists. As such, tabulations of the impacts of introduced species – such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) environmental impact classification for alien taxa protocol (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Bacher, Essl, Hulme, Jeschke, Kühn, Kumschick, Nentwig, Pergl, Pyšek, Rabitsch, Richardson, Vilà, Wilson, Genovesi and Blackburn2015)—present unfalsifiable tautologies where there is no way for an introduced organism to not be ‘harmful’.

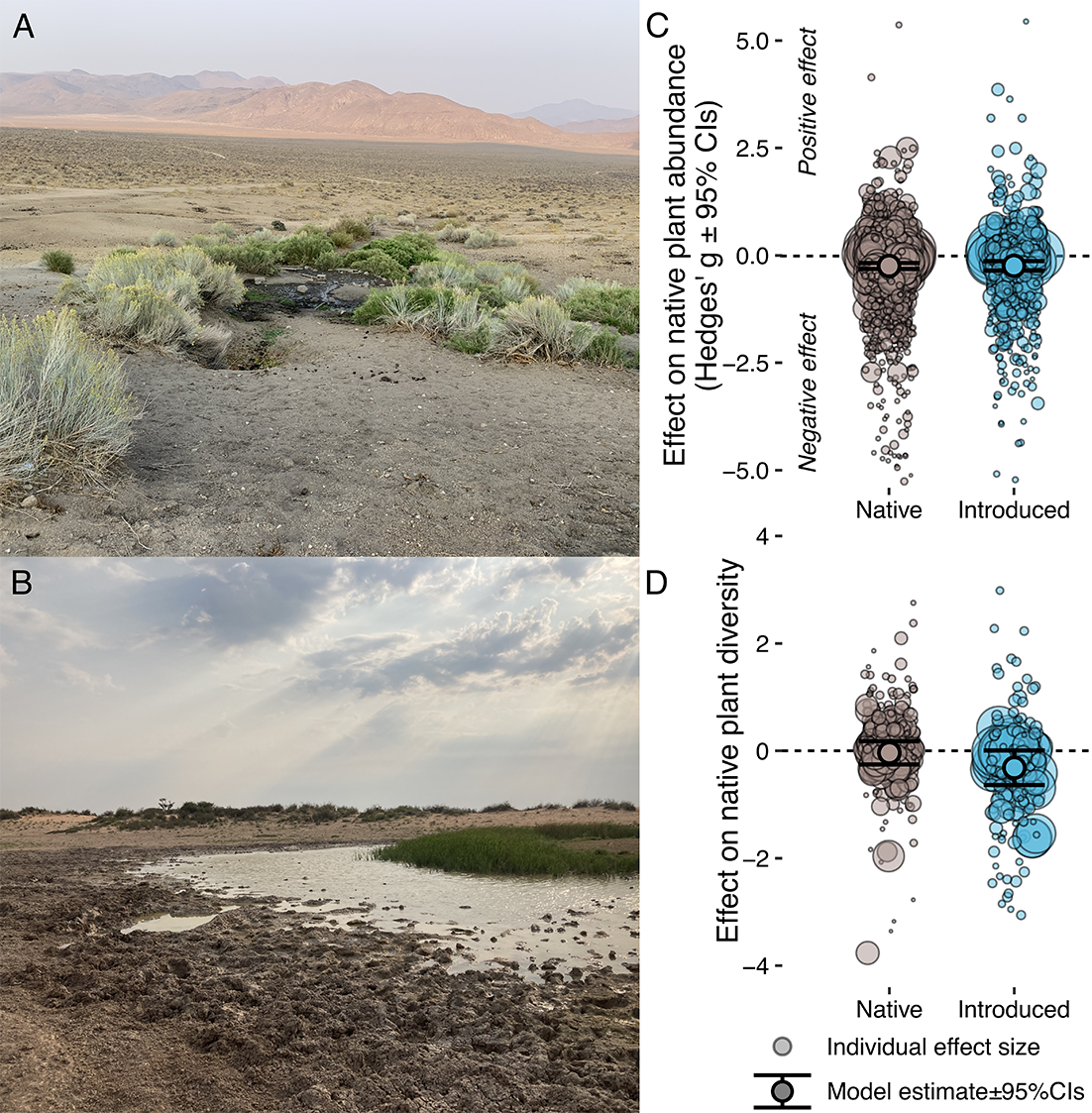

Figure 2. When is nativeness biologically measurable? (a and b) Could an extraterrestrial ecologist empirically determine that the megafauna effects in (a) were caused by introduced megafauna while those in (b) were caused by native megafauna? (a) ©EJL, Feral donkey impacts in Death Valley National Park, (b) ©EJL, native megafauna impacts in the Kalahari, South Africa. (c and d) It does not appear that an extraterrestrial could: A recent systematic meta-analysis of 221 studies found no evidence for differences between the effects of native and introduced megafauna on native plant abundance (c) or diversity (d), with functional traits such as dietary selectivity and body mass instead explaining the effects of native and introduced megafauna alike (Figure from Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Bergman, Trepel, le Roux, Monsarrat, Kristensen, Pedersen, Pereyra, Tietje and Svenning2024a).

Indeed, many, if not most, meta-analyses have found no difference between the effects of introduced and native organisms (e.g., Howard et al., Reference Howard, Therriault and Côté2017; Boltovskoy et al., Reference Boltovskoy, Correa, Burlakova, Karatayev, Thuesen, Sylvester and Paolucci2021; Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Bergman, Trepel, le Roux, Monsarrat, Kristensen, Pedersen, Pereyra, Tietje and Svenning2024a; Wooster et al., Reference Wooster, Ramp, Lundgren, Bonsen, Geisler-Edge, Ben-Ami, Carthey, Carroll, Keynan, Olek, O’Neill, Shanas and Wallach2024a). As an illustrative case in point, consider the Micronesian monitor lizards, which were thought to be introduced by Polynesians, until genetic evidence revealed that these lizards are native and endemic – and now endangered by conservation eradication programs (Weijola et al., Reference Weijola, Vahtera, Koch, Schmitz and Kraus2020).

If one cannot empirically determine the nativeness of an organism based on its impacts, the arguments used to eradicate introduced species could justify the eradication of any living organism. We suggest that identifying when and where nativeness is empirically discernible is a prerequisite to invasion biology’s core claims and should be a key research priority.

In many cases, the effects of introduced species are not only tautological but are confounded with other anthropogenic drivers. For example, of the 256 extinct species on the IUCN Red List for which one or more ‘invasive’ species are listed as a threat, just six have an ‘invasive’ plant mentioned as the primary cause of extinction. All six plants were found on the Seychelles island of Mahé, and the plant invader in question is Cinnamomum verum. However, the cinnamon plant was not simply introduced to the island by humans and then ‘out-competed’ the natives due to its lack of coevolutionary history. Mahé’s forest was almost completely razed by the French for timber in the 1820s, and cinnamon thrived in the starkly novel conditions of the clear-cut (Kueffer, Reference Kueffer2013). It appears to us that the primary cause of these extinctions should properly be described as ‘deforestation’. Moreover, if taking up a high proportion of available space on the local scale is enough to be deemed ‘harmful’, would conservation consider old-growth redwoods, mangroves and boreal spruce to also be ‘harmful’?

This is not to say that introduced organisms do not come into conflict with conservation goals. Yet, so do native species (e.g., Bond and Loffell, Reference Bond and Loffell2001; Barrett and Stiling, Reference Barrett and Stiling2006). For example, both native and introduced species can attain high densities and thus have strong effects because of underlying anthropogenic impacts, such as predator persecution, changes in disturbance regimes, nutrient loading, deforestation and so on (MacDougall and Turkington, Reference MacDougall and Turkington2005; Stromberg et al., Reference Stromberg, Lite, Marler, Paradzick, Shafroth, Shorrock, White and White2007; King and Tschinkel, Reference King and Tschinkel2008; Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Sheley and Svejcar2008; Wallach et al., Reference Wallach, Ripple and Carroll2015; Jeppesen et al., Reference Jeppesen, de Rivera, Grosholz, Tinker, Hughes, Eby and Wasson2025). Focusing on eradication or control in these situations distracts us from addressing ultimate drivers and is likely to be ineffective, especially if eradication only leads to the establishment of other species adapted to the novel conditions (Byers, Reference Byers2002; Kueffer, Reference Kueffer2013).

The work of the conservation scientist, in our view, is to determine the ultimate drivers of conservation conflicts with introduced species, which may include coevolutionary mismatches but can also include purely ecological drivers. We suggest the following questions that we believe are foundational to critical thinking about the effects of introduced organisms and can help reveal new opportunities to prevent extinctions and to focus conservation energies in pragmatic directions.

-

1. Does the introduced organism have effects dissimilar to the effects of similar native species? Or, in other words, could one tell if the organism was introduced if one did not already know?

-

2. Is there any way for the introduced organism to not be ‘harmful’? – that is, are the claims falsifiable? For example, if a study reports on the effects of introduced species on biodiversity but defines biodiversity as only constituting native species, then the claims are tautological and unfalsifiable.

-

3. What are the ultimate drivers of the abundance and impacts of an introduced species? Could they be a function of ecological drivers, such as the persecution of predators, nutrient pollution, climate change, changes in disturbance regimes, fire suppression, deforestation and so on?

How ought the world to be?

Normative values are essential in applied scientific disciplines, such as conservation or medicine. Without values, there is no way to decide what one ought to do, nor where to direct research attention. Much as medicine is driven by a plurality of values (e.g., the life of the patient, their quality of life, avoiding unnecessary pain and so on), which are sometimes aligned and sometimes in conflict, conservation is also driven by a plurality of values for how the world ought to be (Sandbrook et al., Reference Sandbrook, Scales, Vira and Adams2011). Among these values, biological nativism underlies the way many conservation biologists understand introduced organisms and is central to many conservation policies and treaties (e.g., COP15 Rohwer and Marris, Reference Rohwer and Marris2021; Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

Biological nativism is the belief that systems should be similar to how they were at some moment in the past. These temporal baselines are generally defined by the first descriptions of European explorers or, in Europe, the dawn of industrialization (Peretti, Reference Peretti1998; Hettinger, Reference Hettinger2001; IUCN, 2018). However, others (including some members of this authorship team) have argued that the most biologically appropriate baseline for conservation is the range of conditions of the Miocene-Pleistocene (23 million years ago to 12,000 years ago), when large animals set the context under which most modern terrestrial organisms evolved (Faurby and J-C, Reference Faurby and J-C2015; Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Ramp, Rowan, Middleton, Schowanek, Sanisidro, Carroll, Davis, Sandom, J-C and Wallach2020; Søndergaard et al., Reference Søndergaard, Fløjgaard, Ejrnæs and Svenning2025). As such, the inadvertent reintroduction of wild horses in North America or even feral camels in Australia – which share functional similarities to extinct Australian megafauna (Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Ramp, Rowan, Middleton, Schowanek, Sanisidro, Carroll, Davis, Sandom, J-C and Wallach2020) – can be described as either ‘degradation’ or ‘restoration’ depending on which baseline we choose.

Regardless of its temporal baseline, there are legitimate defenses for nativism as a guiding value in conservation. Nativism can be a posture of respect for the world as it once was, which can counteract the ‘overweening arrogance’ (Gould, Reference Gould1998) of working to transform ecosystems for esthetic or economic reasons. In this way, nativism can be defended as a form of intellectual humility: treating the past as a guide given our limited understanding of how ecosystems work.

However, nativism can also perpetuate what many consider to be hubristic and ineffective actions, such as attempting to constrain the inherent dynamism of ecosystems and focusing on eradication instead of addressing the fundamental ecological drivers of undesirable outcomes (Gurevitch and Padilla, Reference Gurevitch and Padilla2004; Wallach et al., Reference Wallach, Bekoff, Batavia, Nelson and Ramp2018a). In this way, nativism can come into stark conflict with other important values that are shared by conservation practitioners and the public – who fund and support the very existence of conservation. These values include preferences for wildness (i.e., for organisms and communities to be autonomous and self-willed [Ridder, Reference Ridder2007]); the intrinsic value of biological collectives (e.g., species regardless of nativeness); the intrinsic value of sentient nonhuman individuals (Wallach et al., Reference Wallach, Bekoff, Batavia, Nelson and Ramp2018a); and the utilitarian value of services rendered to humans (Sandbrook et al., Reference Sandbrook, Scales, Vira and Adams2011).

Prioritizing any one of these values over all others as a ‘moral truth’ oversteps the power of science and excludes those with different values. Moreover, pretending that our values are empirical facts is a form of ‘stealth advocacy’ (Cardou and Vellend, Reference Cardou and Vellend2023) – a major driver of distrust in science with serious consequences to the political legitimacy of conservation and ecology.

While there is no empirical answer for what one ought to do that does not involve values or preferences, working toward value transparency and the clear separation of empirical claims from normative claims can help us navigate these complex paradoxes. We thus suggest the following questions to help guide critical thought about how to respond to the paradoxes presented by introduced species and novel ecosystems:

-

1. Which conservation claims are values in empirical clothes? Terms like ‘ecological health’, ‘invasion’, ‘ecological harm’, ‘pristine’, ‘equilibrium’, ‘degrade’ and ‘disrupt’ are explicitly normative or have deep normative roots. When terms like these are used, even in what seems to be purely empirical research, what values are being deployed?

-

2. As an exercise of imagination, what would happen if a different set of values were prioritized in a conservation project or scientific manuscript? How might our priorities and interpretations change?

-

3. Which values are in conflict or in alignment in a conservation project, and which values are most defensible and aligned with local communities? We suggest that mapping the alignments and conflicts between values in conservation projects can provide insight into an array of pathways for conservation action.

What might a twenty-first century conservation look like?

An evolutionary heartbeat ago, the world was populated by giants whose extinctions led to radical ecological changes (Svenning et al., Reference Svenning, Lemoine, Bergman, Buitenwerf, le Roux, Lundgren, Mungi and Pedersen2024). More recently, humans have again reshaped the world in a great and ongoing species reshuffling. Many of these introduced species are threatened in their native ranges, and all of them are evolving – a process which will increase global species diversity (Singer and Parmesan, Reference Singer and Parmesan2018; Faurby et al., Reference Faurby, Pedersen, J-C and Antonelli2022). While de-extinction may perhaps create functional analogues of lost species, broadening our conservation ethos can also prevent extinctions – instantly and for free – but requires a seismic shift in conservation thinking.

This shift will allow us to see and consider the invisible biodiversity of introduced organisms and the unexpected echoes of prehistoric ecologies in novel ecosystems (Wallach et al., Reference Wallach, Lundgren, Ripple and Ramp2018b; Wooster et al., Reference Wooster, Middleton, Wallach, Ramp, Sanisidro, Harris, Rowan, Schowanek, Gordon, Svenning, Davis, Scharlemann, Nimmo, Lundgren and Sandom2024a). Doing so requires attention to appropriate scientific comparisons, as well as explicit transparency about our values, critical justification of those values and not mistaking values for empirical facts. This will not provide easy answers, but is necessary to face an increasingly novel future (Ordonez et al., Reference Ordonez, Riede, Normand and Svenning2024). After all, rapid changes in global climate and land use are likely to scramble the ranges of all species into never-before-seen configurations (Ordonez et al., Reference Ordonez, Riede, Normand and Svenning2024; Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Ordonez, Riede, Atkinson, Pearce, Sykut, Trepel and Svenning2025).

To face these challenges, we suggest that twenty-first century conservation will need to expand its vision of what is possible and what is good. This does not mean that we abandon our roles as stewards, who intervene to prevent extinctions or other agreed-upon ecological losses. Instead, we should critically examine circular claims regarding the harmfulness of introduced organisms as we work to identify the actions that can best conserve planetary-scale biodiversity, even as it kaleidoscopes into novel configurations. As such, we believe that twenty-first century conservation would benefit from embracing a pluralistic and future-facing ethos that is inspired by many pasts, and that is transparent to the diversity of values that undergird our love for the more-than-human world.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/ext.2025.10010.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/ext.2025.10010.

Data availability statement

This article did not conduct quantitative analyses or use data. The data plotted in Figure 2 is from Lundgren et al. (Reference Lundgren, Bergman, Trepel, le Roux, Monsarrat, Kristensen, Pedersen, Pereyra, Tietje and Svenning2024a).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank M. Schwartz and S. Raymond for helpful comments on earlier drafts. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, and B. Brook and J. Alroy for inviting the authors to submit this perspective.

Author contribution

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Financial support

JCS considers this work a contribution to the Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO), which is funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (grant DNRF173). ADW was supported by a Future Fellowship (FT210100243).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Erick Lundgren (erick.lundgren@gmail.com)

5-061 Centennial Centre for Interdisciplinary SCS II

11335 Saskatchewan Drive NW

Edmonton AB, T6G 2H5, Canada

4th April 2025

Dear Editors,

We are pleased to submit our manuscript “Many pasts, many futures: navigating the complexities of species reshuffling to help prevent extinctions” for consideration as a perspective in Cambridge Prisms: Extinctions. This research is original and is not under consideration elsewhere. We thank Profs Barry Brook and John Alroy for inviting this submission.

In a time of species extinction and massive climate change, conservationists are reaching for paradigm shifts. Notably, rewilding and the promise of technology-fueled de-extinction have become visible pathways to prevent a biodiversity starved future. Less discussed, however, is the contentious possibility that expanding our conservation ethos towards introduced organisms and novel ecosystems—with case-specific guidance from proper empirical comparisons—can also prevent extinctions. After all, a considerable percentage of introduced species are currently endangered or even extinct in their native ranges.

We here present a series of questions meant to guide critical thinking in empirical and normative dimensions regarding how to respond to the complex conflicts and challenges posed by introduced organisms and novel ecosystems. We believe that these challenges are emblematic of this time of ecological uncertainty and require revitalized empiricism and renewed attention to the normative values that undergird conservation action.

Empirically, we focus on the need for proper comparisons to understand the effects of introduced species. Most assessments of the impacts of introduced species lack proper comparisons to make any claim about the influence of nativeness per se, because they do not compare the effects of introduced species to similar native species. This has led to an unfalsifiable tautology, wherein any effect of an introduced organism can be described as an ecological ‘harm’.

We then discuss how conflicts in conservation value systems create legitimate normative disagreements about what constitutes a ‘good’ future for planet Earth. We pose a series of questions in this domain intended to inspire discussion about what we are actually working for and to help conservation scientists separate facts from values, which often wear normative clothes.

We have written this manuscript with the aim of fairly and honestly communicating the complexity of these issues and the need for case-by-case decision making, strong empiricism, and transparent and critical discussions of the values that undergird conservation action. We believe these questions are essential to wrestle with as they underlie and inform other conservation actions, such as rewilding and de-extinction. As such, we believe this article will be of great interest to your readers and will be a highly cited and discussed perspective piece on a contentious but essential topic.

We declare no conflict of interest. Please do not hesitate to contact me should there be any questions regarding this submission (erick.lundgren@gmail.com, +1 585.645.9974).

Thank you for your consideration of this manuscript.

Sincerely,

Erick Lundgren, PhD

Postdoctoral Researcher

Centre for Open Science and Synthesis in Ecology and Evolution

University of Alberta