Introduction

Assessing the social value generated by nonprofit and voluntary organizations (NPVOs) is a theoretical, methodological and practical issue that both academics and nonprofit organizations faced in the last decade. A variety of standardized performance measurements have been proposed and many studies have shown attempts to develop instruments measuring social value and to assess and understand what the nonprofit sector seeks to achieve (Forbes, Reference Forbes1998; Mook et al., Reference Mook, Richmond and Quarter2003; Reed et al., Reference Reed, Jones and Irvine2005; Sabert & Graham, Reference Sabert and Graham2014; Sawhill & Williamson, Reference Sawhill and Williamson2001). Some of the most used ones are the Balance Scorecard (BSC), the Social Return on Investment (SROI) and the Cost–Benefit Social Analysis (CBSA) (Maas & Liket, Reference Maas, Liket, Burritt, Schaltegger, Bennett, Pohjola and Csutora2011) that, however, come with a number of issues (Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Lyon, McKay and Moro2013; Arvidson & Lyon, Reference Arvidson and Lyon2014; Bagnoli & Megali, Reference Bagnoli and Megali2011; Bull, Reference Bull2007; Treinta et al., Reference Treinta, Moura, Almeida Prado Cestari, Pinheiro de Lima, Deschamps, Gouvea da Costa and Leite2020). Indeed, these tools have mainly adapted classical profit principles such as investment, cost-benefits, efficiency, accountability and performance to the aims and functioning of social enterprises but, in doing so, have also generally failed to account for the specific extra-economic impact of value-driven organizations, such as NPVOs, that mostly prioritize social value over economic value (Mair & Marti, Reference Mair and Marti2006).

The need to consider the unique social impact and social value of NPVOs has become more and more pressing since in several European countries recent national legislation has prompted NPVOs to monitor and assess the social value they generate (for example in the UK: Courtney, Reference Courtney2017 or in Italy: Law 106/2016). As a result, currently there is a growing interest among NPVOs in systematic assessing their social outcomes both to support internal decision-making and to increase transparency and accountability vis-à-vis their stakeholders––beneficiaries, but also funders––(Knutsen & Brower, Reference Knutsen and Brower2010; Straub et al., Reference Straub, Koopman and van Mossel2010).

In order to capture the specific social value of NPVOs, Italian relational sociologists have developed the notion of social added value (SAV) (Bassi, Reference Bassi2011, Reference Bassi, Franz, Hochgerner and Howaldt2012, Reference Bassi2013; Donati, Reference Donati2013, Reference Donati2014), which refers to the ability to produce, maintain and regenerate relational goods for both NPVOs members and the broader community. In this perspective NPVOs would be able to produce relational social inclusion through a virtuous interaction between relational goods and social capital. Indeed, social capital is itself a specific relational good, configured as a social exchange that operates through trust and cooperative norms: as such, it is both a precondition for the emergence of relational goods and is in turn regenerated by them (Donati & Solci, Reference Donati and Solci2011).

A few years ago, in a study run on a range of NPVOs based in Southern Italy, Mannarini and colleagues (Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018) developed a model-based measure that enriched the relational sociological approach by including a range of psychosocial variables drawn from organizational and community psychology. Specifically, SAV was operationally defined as composed of two components:

a. Internal relational goods (for NPVOs members) resulting from sense of organizational community, identification with the organization, perceived social support from co-members, good internal relationships, role satisfaction, influence on the organization’s decisions, and organization’s social responsibility towards members.

b. External relational goods (for community members, users, and stakeholders) resulting from the quality of external relations and the organization’s social responsibility towards users and institutions, and towards social and non-social stakeholders.

The present study intended to complement Mannarini and colleagues’ (Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018) work with the aim to integrate the perspective of NPVOs members on SAV (specifically, on the external relational goods) with the perspective of community members, who can be either direct users of the NPVOs’ activities, stakeholders related to NPVOs for institutional or economic reasons, or people who has never been in contact with this type of organizations in any role. Therefore, this study––planned as a continuation of the previous one––was set up to develop a scale to measure SAV according to the perception of community members who are not actively involved in NPVOs, that is, among members of the general public.

Public Perception of NPVOs

Studies conducted in different European countries and in the United States suggest that at the community level, NPVOs are considered as actors able to contribute to community development and whose role and activities are beneficial to the well-being of both individuals and society at large (Arvidson, Reference Arvidson2009 as for UK; Rebetak & Bartosova, Reference Rebetak and Bartosova2020 as for Slovakia). In the US these organizations have emerged in many communities as stakeholders delivering important services and promoting social capital and responsible behavior (Mathew, Reference Mathews, Flynn and Hodgkinson2001). Notwithstanding, the public perception of NPVOs is multifaceted as it combines mixed impressions. International research, on the one hand, highlighted a decline in the confidence in NPVOs and negative public perceptions (Light, Reference Light2008) but, on the other hand, also showed that the general public often has fairly positive perceptions of certain high-impact national or international NPVOs (Sagawa & Jospin, Reference Sagawa and Jospin2009). For instance, in Italy Bonanomi et al. (Reference Bonanomi, Migliavacca and Rosina2018) found an overwhelmingly positive view of volunteering, perceived as a trustworthy and reliable practice among a representative sample of young Italians who placed it second in a ranking of institutions where only three scored the minimum threshold.

Both negative and positive public perceptions (see Bekkers et al., Reference Bekkers, Mersianova, Smith, Abu-Rumman, Layton, Roka, Smith, Stebbins and Grotz2016 for an international review) can be influenced through exposure to media emphasizing flaws or scandals of “deviant organizations” (Smith, Reference Smith2016), or focusing on few virtuous examples, or through personal experiences or experiences by close people (Schlesinger et al., Reference Schlesinger, Shannon and Gray2004). Specifically, awareness stands out as a key factor orienting public perceptions. As revealed by a survey from McDougle (Reference McDougle2014) in San Diego County, individuals with higher levels of NPVOs awareness are also more likely to perceive their performances more positively, that is, they are more confident in the ability of NPVOs to use wisely their resources and provide quality services.

As far as SAV is concerned, to the best of our knowledge no study has specifically investigated how members of the general public perceive the NPVOs’ contributions to the community in terms of relational goods.

Study Context

In order to validate a measure of SAV based on the perception of community members, data were collected in two different areas of Italy, characterised by different socio-economic conditions: the province of Milan, a metropolitan city (1,349,930 inhabitants in 2022) located in one of the richest regions of Italy—Lombardy—in the North of the country, and the province of Lecce (94,783 inhabitants in 2022), a medium-sized urban center located in the less rich South (Apulia region). To mention just one economic indicator, the average family income is remarkably higher in Lombardy, both in the case of employment and self-employment (in 2020, 40,858 and 52,489 euros respectively, compared to 29,860 and 32,245 euros in Apulia, ISTAT public dataset: http://dati.istat.it/). Lombardy and Apulia also have different positions in the ranking of the 22 Italian regions based on the Welfare Index – a combination of 22 key performance indicators covering structural indicators (e.g., unemployment, school dropout, social housing, health facilities, etc.) and investments in health, social services, education, pensions, etc. –. On a scale 0–100 in 2022 Lombardy scored 73.8 (5th in the ranking) and Apulia 56.9 (16th in the ranking) (Think Tank “Welfare Italia”, 2022). The differences between the two regions also concern the number of NPVOs (ISTAT, 2022): in Lombardy, in 2020, there were 57.9 organisations per 10,000 inhabitants, while in Apulia the ratio was 48.9. However, while in the former the total number of NPVOs had slightly decreased (−0.4%) compared to 2019, in the latter it had increased (+ 1.6%). In addition, NPVOs in the South were established more recently than those in the North: half of the NPVOs in the South were established in 2010, in the North in 2004–2005 (ISTAT, 2022).

In terms of municipal spending on families and children, the disabled, the elderly, immigrants, and those living in extreme poverty, the average per capita expenditure in 2019 in Milan was 171 euros, while in Lecce was 68 euros (ISTAT public dataset: http://dati.istat.it/). Finally, there are also territorial differences in social capital. In 2022 (ISTAT public dataset: http://dati.istat.it/), 28% of people living in Lombardy agreed that most people are trustworthy, compared with 20.9% in Apulia (ISTAT public dataset: http://dati.istat.it/). The rationale for selecting areas that differ in terms of NPVOs and welfare index was to validate the theory-driven measure across contexts.

Study Rationale and Aims

For the purpose of the present study SAV was operationalized as the external relational goods generated by NPVOs and concerning the members of the general public, who is composed of three categories: users of the organizations’ services and activities, stakeholders with various roles (i.e., providers, local administrators, etc.), and individuals who do not or did not previously have any relationship with NPVOs.

SAV was conceptualized as resulting from three psychosocial indicators:

a. Contribution to the Community. In defining the type of contribution both the concrete and the socio-symbolic dimension were considered. At the concrete level NPVOs deliver services and accomplish tasks that meet basic community needs but whose quality can vary (services and tasks component). Indeed, these services are in many cases important or even essential for people’s lives (NICVA, 2017), yet many nonprofit organizations struggle to evaluate the quality and efficacy of their activities (Bach-Mortensen & Montgomery, Reference Bach-Mortensen and Montgomery2018). At the socio-symbolic level, NPVOs can show a more or less pronounced capacity of vision, i.e., considering the broader context of their activities and their deployment in time and space, and low or high awareness of their position and role in the community (vision component). Vision relates to the beliefs and values of organizations, including their leaders’ and members’, and plays a crucial role in NPVOs’ development as it works like a compass directing activities towards their mission (Liao & Huang, Reference Liao and Huang2016) and influencing their strategic development and performance (Balduck et al., Reference Balduck, Van Rossem and Buelens2010). The NPVO’s mission and vision can facilitate innovation (McDonald, Reference McDonald2007), which supports NPVO’s sustainability in the long term (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Lau and Lee2019) and is an important step to achieve superior organizational performance. Finally, NPVOs can also adopt socially responsible behaviors by showing concern or neglect towards the community and the environment and by taking care or disregarding both (social responsibility component). As Zeimers et al., (Reference Zeimers, Anagnostopoulos, Zintz and Willem2019, p. 956) put it, “beyond providing basic social services, NPOs responsibilities can also consist in looking beyond their own interests and contribute to the needs of the community and society”.

b. Quality of External Relationships. As community actors, NPVOs interact with a variety of stakeholders in various roles. The quality of such interactions indicates their more or less developed ability to establish relationships characterized by four dimensions: control mutuality, communal relationship, trust and commitment. Control mutuality is the ability to create a virtuous circle of mutual listening and valuing while also promoting interactional settings where every person/institution/organization can have a voice and each contribution is actually considered. In other words, it is the balance and point of agreement over how power is arranged in the relationship. Communal relationship refers to achieving goals and showing empathy, altruism and care for others while safeguarding respect for people and the environment. Trust refers to the level of confidence in and willingness to be exposed to other social actors and also indicates how NPVOs are considered trustworthy and accountable. Commitment ––in its ethical sense––is intended as the feeling of attachment to the relationship with the other, the personal/organizational intention to continue and the effort to ensure its continuity and improve its quality (Knutsen & Brower, Reference Knutsen and Brower2010). In brief, it entails that the relationship is worth the time and energy spent on it.

c. Capacity to Build Community Connections. NPVOs differ in terms of whether and how much they are willing to create community collaborative networks and intentionally act to achieve this goal, as opposed to operating alone and being uninterested in setting up shared initiatives and projects with community stakeholders. This component is different from (b) as it does not refer to the quality of relationships with various stakeholders but, rather, to whether NPVOs are willing to establish inter-organizational connections within the community. As Mariani and Cavenago (Reference Mariani and Cavenago2013) and Di Napoli et al. (Reference Di Napoli, Esposito, Candice and Arcidiacono2019) well illustrated, NPVOs play an important connector role between people, institutions and organizations.

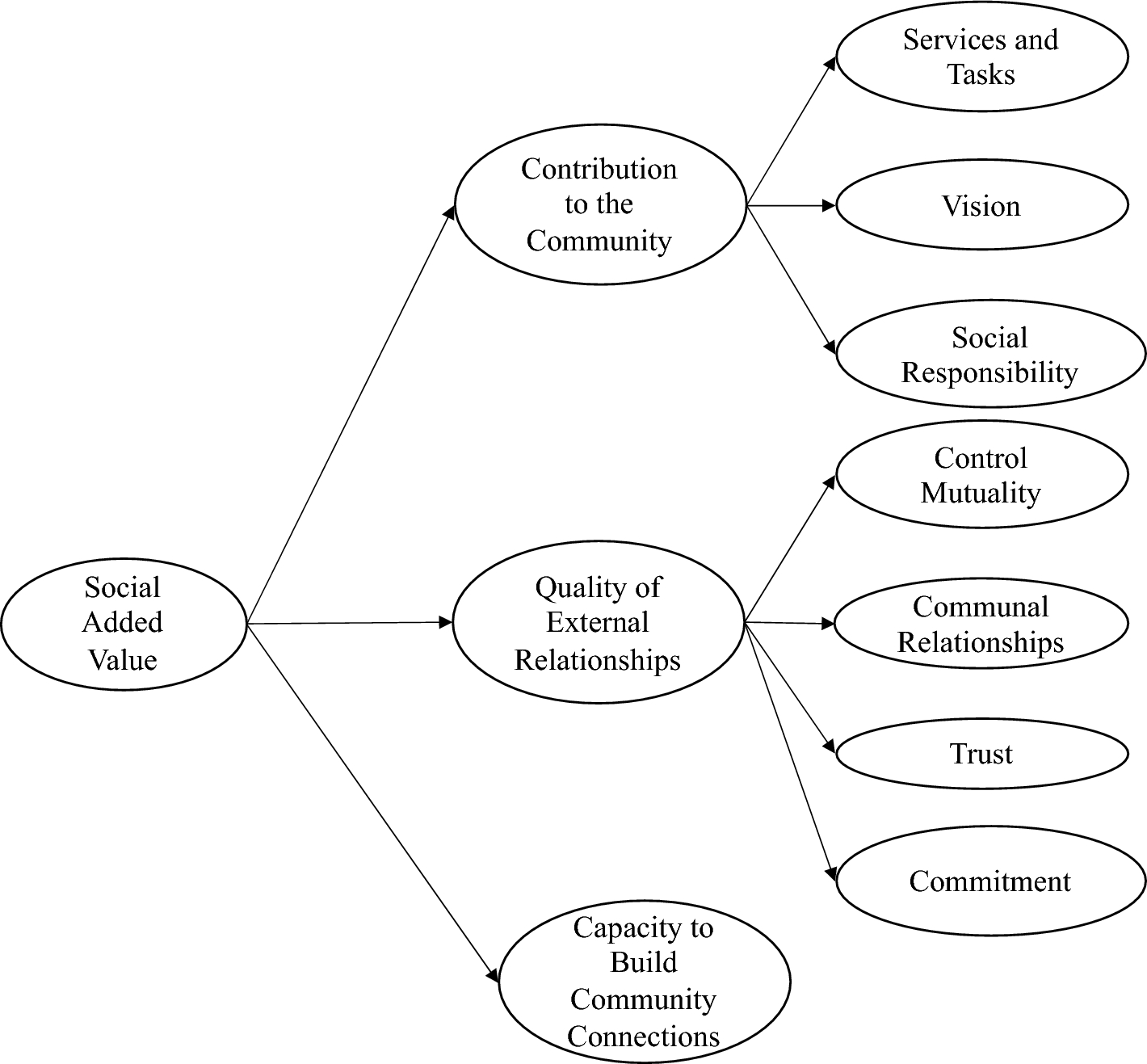

The main goal of the study was to develop and validate a model-based measure of SAV. Specifically, it was expected that the three variables mentioned above (i.e., contribution to the community; quality of external relationships––both multidimensional constructs––and capacity to build community connections––a unidimensional construct) would saturate onto a higher-order variable, i.e., SAV (see Fig. 1) (H1).

Fig. 1 Theoretical framework

The second aim was to assess the relationship between SAV and two psychosocial variables: perceived NPVOs target values (Colozzi, Reference Colozzi2011) and sense of belonging to the community among the public (McMillan & Chavis, Reference McMillan and Chavis1986). Indeed, NPVOs are most often inspired by values that shape and underlie the organizational aims, activities and behaviors (Sarstedt & Schloderer, Reference Sarstedt and Schloderer2010). A relationship between the organization target-values and SAV was found among NPVOs members (Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018), suggesting that the more individuals perceive NPVOs as value-driven, the more they are likely to also perceive what these organizations can generate in terms of SAV. Based on this finding, the same trend was expected also among non NPVOs members, that is, in the general public (H2).

As far as sense of belonging to the community is concerned, a similar positive association with SAV was expected (H3). The rationale behind this hypothesis is that people who score higher in sense of belonging are likely to develop more positive perceptions of their community as both a social and functional environment (Mannarini & Fedi, Reference Mannarini and Fedi2009; Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Tartaglia, Fedi and Greganti2006; Winkle & Woosnam, Reference Van Winkle and Woosnam2014). Moreover, feelings of community belonging are associated with trust in community co-members (Blanchard, Reference Blanchard, Welbourne and Boughton2011; ter Huurne et al., Reference Huurne, Ronteltap and Buskens2020) and prosocial behavior patterns (Omoto & Snyder, Reference Omoto, Snyder, Stürmer and Snyder2009). This inclination is likely to resonate and be associated with favorable attitudes towards the actions and outcomes of community organizations such as NPVOs, that are often inspired by solidarity-based values.

Finally, the third aim was to compare different categories of community members on SAV scores: It was expected that individuals who were direct users of NPVOs’ services would show more positive perceptions and score higher on SAV (H4) compared to those who were in a different relationship with NPVOs (e.g., economic stakeholder/institutional stakeholder/community member attending NPVOs public events) or were in no relationship at all. This expectation was based on the hypothesis that a direct involvement as users would contribute to a higher NPVOs’ awareness (McDougle, Reference McDougle2014), thereby resulting in a more positive perception of the organization’s mission.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The participants involved in this study were 720 Italian citizens not engaged in NPVOs as active members. Non-membership was set as the minimum requirement for participation. They were recruited in the municipalities of Milan (37.5%) and Lecce (62.5%) and in several surrounding municipalities of the respective provinces, and were invited to participate in a study on their knowledge and perception of NPVOs. They were asked to answer a self-report questionnaire in the format they felt more comfortable with (paper or online), a task which took about 15 min and that was voluntarily undertaken with no incentives. According to APA’s ethical guidelines (standard 3.10, Informed consent) participants were informed on the subject, aim and procedures of the study as well as their right to refuse or withdraw at any time. Participants were recruited through advertisements on social networks (e.g., Facebook), emails and snowball sampling, with the help of trained and supervised Masters students enrolled at the University of Salento in Lecce and the Catholic University of Milan. Snowball sampling was used to increase the interest and willingness of potential participants to take part in the study, as they were asked by someone they knew or trusted.

Respondents (54.2% women) were aged between 18 and 80 (M = 39.1; SD = 15.35). Most of them (44.6%) had a high school diploma as their highest educational qualification, yet a similar percentage had a bachelor’s degree or higher (41.2%). Only a few had a secondary school diploma (14.2%). Among the participants, 18.9% were clerks and traders, 4.6% workers, 11.2% freelance professionals or small business owners, 9.4% teachers, and 9.3% doctors and paramedics. Among the non-working participants 24.7% were college students, 6.7% were housewives/husbands, 3.6% were retirees and 2.9% were unemployed. A residual percentage of 6.5% reported unspecified employment conditions.

Almost half of the sample (52.2%) revealed they had had at least one direct contact with one NPVO in the past and, among these respondents, 29.1% had been NPVOs users (i.e., direct beneficiaries) at least once.

Measures

A self-report questionnaire was developed and consisted of the following sections:

a. Background information: age, gender, education, employment and place of residence.

b. Contact/relationship with NPVOs. Participants were asked whether they had had a direct contact with at least one NPVO in the past and, if so, what kind of NPVO it was (voluntary organization/social cooperative/foundation/association for social advancement/cultural association/NGOFootnote 1), in what capacity they had this contact (direct beneficiary of services/economic stakeholder/institutional stakeholder/community member attending public events/other) and the frequency (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often).

c. Sense of belonging to the community. One ad hoc Likert-type item from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”) was used to rank agreement to the statement “I feel I belong to this community”.

d. Perceived NPVOs Target Values (α = 0.93). The NPVOs target values scale drawn from Colozzi (Reference Colozzi2011) was used. Respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point scale (1 = not all; 5 = completely) how much they perceived that NPVOs were based on a set of target values (i.e., promoting community development, equal opportunities for children, trust in institutions, civil rights, tolerance and respect for diversity, civic engagement, sense of belonging and caring, supporting a fair distribution of resources, and helping impaired and disadvantaged groups).

e. Social Added Value (SAV). Three scales were used to measure NPVOs SAV as perceived by non NPVOs members:

e1. Contribution to the community (α = 0.83). Three subscales of the Reputation Quotient for corporate reputation (Fombrun et al., 1999), each one composed of three items, were adapted so as to assess the NPVOs’ services and tasks (α = 0.73) (e.g., “NPVOs offer high quality products and services”), social responsibility (α = 0.79) (e.g., “NPVOs address important and significant issues for society”), and capacity of vision (α = 0.72) (e.g., “NPVOs have a clear vision for the future”). The response format ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

e2. Quality of external relationships (α = 0.87). Four subscales of the PR Relationship Measurement Scale (Hon & Grunig, Reference Hon and Grunig1999) were adapted so as to assess the quality of NPVOs external relationships: control mutuality (α = 0.79), i.e., the degree to which parties agree on who has the rightful power to influence one another (5 items, e.g., “NPVOs really listen to what people have to say”); communal relationships (α = 0.78), i.e., the degree to which parties provide benefits to the other because they are concerned for the welfare of the other (5 items, e.g., “NPVOs help people without expecting anything in return”); trust (α = 0.89), i.e., the level of confidence in and willingness to open up to the other party (6 items, e.g., “NPVOs can be trusted to keep their promises”); and commitment (α = 0.81), i.e., the extent to which parties feel that the relationship is worth spending energy to maintain and promote (3 items, e.g., “NPVOs want to maintain a relationship with people”). The response format ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

e3. Capacity to build community connections (α = 0.78). Two ad hoc items were developed to assess the degree to which NPVOs also are willing to create community collaborative networks and intentionally act to achieve this goal, with a response format ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = fully (2 items, i.e., “NPVOs collaborate with institutions and community stakeholders” and “NPVOs develop relational and actional networks with community stakeholders and groups”).

Analyses

A set of analyses was performed. First, a confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) aimed to obtain a measure of SAV that could be theoretically and psychometrically satisfactory. MPlus was used to test the model. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model we intended to test. Second, a linear regression model was performed to assess the relationship between perceived NPVOs target value and sense of belonging to the community and SAV. Finally, an ANOVA procedure was performed to compare groups with different types of contact/relationship with NPVOs’ around SAV scores and a t-test analysis was used to compare SAV scores between the two sites.

Results

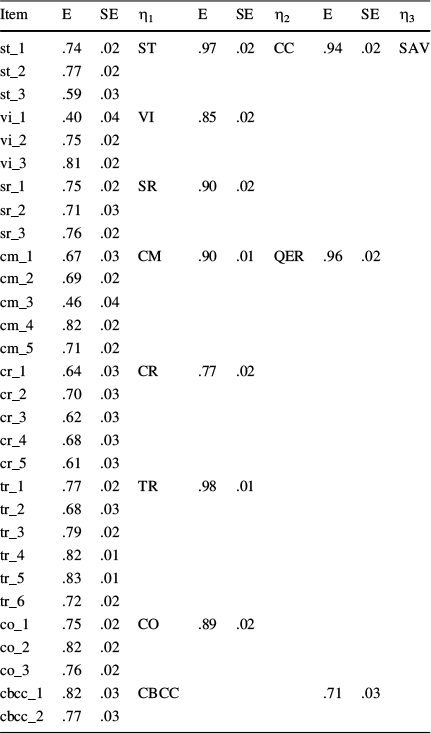

The tested SAV model included eight first-order variables, two second-order variables and one third-order variable. The first-order variables were control mutuality (5 items), communal relationships (5 items), trust (6 items), commitment (3 items), services and tasks (3 items), social responsibility (3 items), vision (3 items), and capacity to build community connections (2 items). The second-order variables were quality of external relationships and contribution to the community. The third-order variable was SAV. The model obtained an acceptable fit, χ2 (395) = 1072.98, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.92; TLI = 91; RMSEA = 0.05 [0.04, 0.05], p < 0.05; SRMR = 0.05; BIC = 41,851.55, with all the variables included showing high saturations on the respective higher-order variable (see Table 1 for the model parameters).

Table 1 Parameters of the measurement model

Item |

E |

SE |

η1 |

E |

SE |

η2 |

E |

SE |

η3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

st_1 |

.74 |

.02 |

ST |

.97 |

.02 |

CC |

.94 |

.02 |

SAV |

st_2 |

.77 |

.02 |

|||||||

st_3 |

.59 |

.03 |

|||||||

vi_1 |

.40 |

.04 |

VI |

.85 |

.02 |

||||

vi_2 |

.75 |

.02 |

|||||||

vi_3 |

.81 |

.02 |

|||||||

sr_1 |

.75 |

.02 |

SR |

.90 |

.02 |

||||

sr_2 |

.71 |

.03 |

|||||||

sr_3 |

.76 |

.02 |

|||||||

cm_1 |

.67 |

.03 |

CM |

.90 |

.01 |

QER |

.96 |

.02 |

|

cm_2 |

.69 |

.02 |

|||||||

cm_3 |

.46 |

.04 |

|||||||

cm_4 |

.82 |

.02 |

|||||||

cm_5 |

.71 |

.02 |

|||||||

cr_1 |

.64 |

.03 |

CR |

.77 |

.02 |

||||

cr_2 |

.70 |

.03 |

|||||||

cr_3 |

.62 |

.03 |

|||||||

cr_4 |

.68 |

.03 |

|||||||

cr_5 |

.61 |

.03 |

|||||||

tr_1 |

.77 |

.02 |

TR |

.98 |

.01 |

||||

tr_2 |

.68 |

.03 |

|||||||

tr_3 |

.79 |

.02 |

|||||||

tr_4 |

.82 |

.01 |

|||||||

tr_5 |

.83 |

.01 |

|||||||

tr_6 |

.72 |

.02 |

|||||||

co_1 |

.75 |

.02 |

CO |

.89 |

.02 |

||||

co_2 |

.82 |

.02 |

|||||||

co_3 |

.76 |

.02 |

|||||||

cbcc_1 |

.82 |

.03 |

CBCC |

.71 |

.03 |

||||

cbcc_2 |

.77 |

.03 |

ST services and tasks, VI vision, SR social responsibility, CM control mutuality, CR communal relationships, TR trust, CO commitment, CBCC capacity to build community connections, QER quality of external relationships, CC contribution to the community, SAV social added value

All parameters are significant (p = .00)

With regard to the components of the second-order variables, the most relevant first-order variable loading on contribution to the community was services and tasks, followed, in order, by social responsibility and vision. Regarding the second-order variable quality of external relationships, trust was the most relevant factor, followed by mutual control, commitment, and communal relationships.

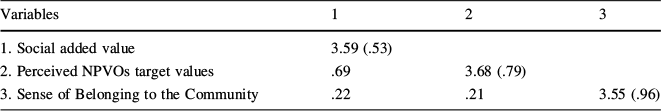

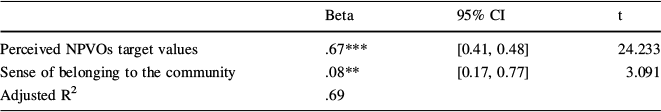

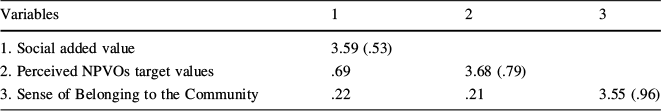

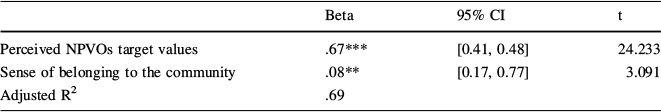

To assess the relationship between perceived NPVO target values, sense of belonging to the community and SAV, a linear regression model was performed. Both perceived NPVO target values and sense of belonging showed a positive relationship with SAV (F [2, 717] = 328.37, p = 0.000), yet with different strength––i.e., remarkably higher for values. The variance explained was high (adjusted R2 = 0.69) (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics, correlations and standard deviations and Table 3 for results).

Table 2 Correlations, means and standard deviations

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|---|---|---|---|

1. Social added value |

3.59 (.53) |

||

2. Perceived NPVOs target values |

.69 |

3.68 (.79) |

|

3. Sense of Belonging to the Community |

.22 |

.21 |

3.55 (.96) |

The table shows Pearsons r correlation coefficients. Diagonal cells report the variable mean (standard deviation in parentheses). All correlations are significant at p < .01

Table 3 Regression model. IVs: Values and sense of belonging to the community; DV: NPVOs social added value

Beta |

95% CI |

t |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Perceived NPVOs target values |

.67*** |

[0.41, 0.48] |

24.233 |

Sense of belonging to the community |

.08** |

[0.17, 0.77] |

3.091 |

Adjusted R2 |

.69 |

Standardized regression coefficients are reported

CI confidence interval

***p < .001; **p < .01

To ascertain the differences on SAV scores between respondents who experienced different types of contact/relationship with the NPVOs (no contact; contact as economic/institutional stakeholder or community member attending NPVOs public events; users, i.e., direct beneficiary of services) an ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analyses was performed. A scalar relation between the type of contact and SAV was observed (F [3, 718] = 24.77, p = 0.000). In particular, people who referred they had had no contact with NPVOs scored lower on SAV than those who had entered in contact with NPVOs as economic/institutional stakeholder or community members attending NPVOs public events (M difference = −0.14, p = 0.014) and even lower compared to direct beneficiaries of NPVOs services (M difference = −0.36, p = 0.000).

Finally, a t-test analysis was carried out on the three components of SAV (i.e., contribution to the community, quality of external relationships, and capacity to build community connections) in order to observe possible differences between participants living in the northern and in southern areas of Italy. The only statistically significant difference was found for the contribution to the community component, where southern participants (M = 3.57, DS = 0.49) scored significantly higher than northern participants (M = 3.41, DS = 0.49), t(649.73) = 3.74, p = 0.000.

Discussion

Our study proposed a model-based measure for identifying non-profit organizations’ SAV, complementing the paper of Mannarini et al. (Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018) that focused on organizations’ members. As in the previous work, NPVOs SAV is defined as the psychosocial benefits generated by the organizations, in this case the benefits enjoyed by community members. Both studies adopt, as starting point, an earlier relational sociological theoretical approach (Bassi, Reference Bassi2011, Reference Bassi, Franz, Hochgerner and Howaldt2012, Reference Bassi2013; Donati, Reference Donati2013, Reference Donati2014) that conceptualizes social value as relational goods (i.e., non-material goods produced and consumed within groups, intrinsically linked to relationships and interaction, Bassi, Reference Bassi2011, Reference Bassi, Franz, Hochgerner and Howaldt2012; Uhlaner, Reference Uhlaner1989). Jointly, the main results of the two studies suggest that, in the case of individuals actively participating in a NPVO and its direct beneficiaries, the external relational goods generated by their own organization can be assessed as the extent to which the organization behaves responsibly towards users, stakeholders and institutions, and is able to create and maintain satisfying and nonconflictual relationship with them (Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018). For community members, external relational goods can be assessed as the extent to which NPVOs contribute to the community through the provision of concrete (i.e., services) and symbolic (i.e., vision) assets, social responsible behavior, willingness to create cooperative community networks, and ability to build their external relationships on collaborative principles.

The development of the SAV construct is the outcome of the hybridization between the sociological and community psychology approach and constructs. Specifically, according to the model developed in this study, SAV is constituted by three main elements: Contribution to the community, Quality of external relationships, and Capacity to build community connections.

The first one, Contribution to the community, is composed of services and tasks, pointing to the quality and innovation of the services offered, vision, referring to the ability to outline the organization’s development while also considering community orientations and directions, and social responsibility, looking at the capacity of NPVOs to identify the most important issues for people and the environment, and to find appropriate answers driven by values such as honesty and ethics. The second component of SAV, Quality of external relationships, includes control mutuality, c ommunal relationship, trust, and commitment. These four variables are usually used in the literature to measure the quality of the relationships that NPVOs establish with members, stakeholders, institutions and the general public (Hon & Grunig, Reference Hon and Grunig1999; Huang, Reference Huang2001; Hung, Reference Huang2001). The third component of SAV, Capacity to build community connections, emphasizes the capital of skills and resources mobilized to collaborate and develop networks that aim not just to implement specific projects but, more broadly, to address community needs.

Based on the model described above, the empirical measurement of SAV led to the definition of a third-order factor model (as expected in H1) saturated by two-order variables (contribution to the community and quality of external relationships) and eight first-order latent variables (services and tasks, vision, social responsibility, control mutuality, communal relationships, trust, commitment, and capacity to build community connections).

According to our results, community members considered the innovation and quality of the services provided as the most influential type of contribution that NPVOs offer to the community, followed by the assumed social responsibility (assumed by community members). As for the quality of external relationships, being trustful and accountable was deemed more important than relational mutual control and commitment, which in turn weighed more than communal relationships. As concluded by Van Dyk and Fourie (Reference Van Dyk and Fourie2012), the distinction between ‘exchange’ (quid pro quo) and ‘communal’ relationships in NPVOs does not seem to be really relevant, and although communal relationships are important, they are not the most important variable in determining SAV for community members.

As expected (H2 and H3), both perceived NPVOs target values and sense of belonging to the community were positively associated with SAV––the former to a greater extent. Indeed, when community members perceive that NPVOs promote values such as inclusion, justice and equality, community development, tolerance and solidarity, this perception is linked to an increase in the SAV level attributed to the same organizations. Hence, NPVOs that stand out as distinctively ‘value-driven’ are also likely to be acknowledged as having the capacity to generate SAV for the community.

The association between sense of belonging and NPVOs SAV, on the one hand, by suggesting that people with a higher sense of belonging to the community tend to perceive a greater contribution of the NPVOs, revealed a greater appreciation of the relational and social resources available in the community environment among those who value their belonging. At a conceptual level, this finding is consistent with research on sense of community (Mannarini & Fedi, Reference Mannarini and Fedi2009; Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Tartaglia, Fedi and Greganti2006), which highlights its association with trust (Blanchard, Reference Blanchard, Welbourne and Boughton2011; Huurne et al., Reference Huurne, Ronteltap and Buskens2020), other-focused values (Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Rochira, Ciavolino and Salvatore2020), and prosocial behaviour (Omoto & Snyder, Reference Omoto, Snyder, Stürmer and Snyder2009).

On the other hand, such findings could also result from the broader tendency to see one’s own group members more positively (ingroup bias) (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981)––assuming NPVOs were socially categorized by respondents as members of the ingroup, i.e., the community. However, this explanation could work only at a speculative level, since no data on the social categorization process was gathered in the present study.

Finally, differences were found between different groups of community members according to the type of contact they had established with NPVOs (H4). In line with McDougle (Reference McDougle2014), those who benefited from the services of NPVOs could learn about these organizations, see their activities and values and become aware of their social value more than those who had only occasional or little in-depth contact through their institutional or economic role (e.g., product suppliers). Those who benefited and those who had sporadic or instrumental contacts also had greater perception of NPVOs SAV compared to those who had no contact at all, and therefore no opportunity to learn about them and the effects of their actions.

The North–South difference in the perception of the contribution of NPVOs to the community is not easy to explain. As a speculative hypothesis, we wonder whether the greater appreciation of this aspect among Southern residents might be influenced by the existence of a less consolidated and extended local welfare system compared to that established in the North of Italy. If NPVOs meet people's needs that are not met by the current welfare system, or if they meet the needs of a greater number of people, their contribution may be more valued because it fills a huge gap. For this reason, in a relatively deprived context, the contribution of NPVOs may be perceived as more prominent than in communities where there are many more services and facilities, and more longer-lived NPVOs, and where people are both used to NPVOs and do not struggle to meet their needs.

Our study has some limitations that should be addressed. The major limitation relates to the sample selected, that is limited to only two––yet different––areas in Italy (Northern and Southern Italy). To further enhance the scale, it might be useful to test the external validity of this SAV scale. Despite this limitation we believe that the scale is ready to be applied in other Italian but also European contexts, considering that the single constructs composing the SAV model-based scale were sound and drawn from international community and organizational psychology research and considering the excellent results of the statistical analyses. The broader application of the scale could help detect factors that remain invariant and factors that may vary according to different socioeconomic and cultural contexts, thus making the scale even more solid.

Another limitation is related to the time at which the data were collected. In fact, because data was collected just before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and before the Russian-Ukrainian conflict––in other words, before the beginning of an enduring period of global crisis––it would be interesting to replicate the study now to confirm or disconfirm the results achieved so far. Future research should address the limitations of this study and investigate the applicability of the SAV model in different socioeconomic and cultural contexts. It would be equally relevant to conduct research aimed at ascertaining how different types of NPVOs uniquely address the specific components of SAV.

However, the study also has strengths. The first is that it has filled a gap by offering a tool to measure SAV, which is also synthetic and articulated, as it can be used as a single dimension and/or with reference to specific sub-dimensions. Furthermore, this study has a clear strength at the theoretical level in that it combines the organisational (see Mannarini et al., Reference Mannarini, Talò, D’Aprile and Ingusci2018) and community perspective, the sociological and psychological approaches, in a single conceptualisation of SAV, while at the same time offering a measurement tool that is theory-based. Researchers can use this scale to read the reputation and attitude of different NPVOs in different contexts, to study the organisational culture of NPVOs and, in a predictive sense, to measure the degree of their penetration in the community.

Implications for Theory, Practice and Policy

Acknowledging and measuring the social value generated by NPVOs has become an issue increasingly discussed among both researchers and practitioners.

At a theoretical level, the current study contributes to the debate on social capital by assuming that the SAV of NPVOs consists in maintaining, restoring and regenerating relational goods in the community. Indeed, the very notion of social capital is based on the idea that a certain way of understanding and acting on social relations constitutes a collective resource, a value not only for individuals but also for groups and communities (Bagnasco et al., Reference Bagnasco, Piselli, Pizzorno and Trigilia2001). If NPVOs can contribute to increasing social capital (Wollebaek & Selle, Reference Wollebaek and Selle2002, Reference Wollebaek, Selle and Osborne2008), their role is particularly valuable in contexts where social capital is fragile or at risk. Moreover, if we draw attention to the overlap between social capital and another collective resource such as sense of community (Meneghini & Stanzani, Reference Meneghini, Stanzani and Mannarini2022), we can see how NPVOs, through their SAV, can also socialise people into a sense of societal community (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007).

Findings from this study provide several practical implications for NPVOs. Understanding the different components of the social value that they generate (contribution to the community through service delivery, vision and socially responsible behavior, quality of external relationship based on control mutuality, communality, trust, commitment, and capacity to build community connections) can serve as a reference guide for NPVOs. Knowledge of these components can help NPVOs enhance their performance and awareness on their social role. At a practical level, NPVOs could use these results to develop recruitment communication campaigns. They could also propose activities and programs that reinforce their identity based on the constructs underpinning the model presented here. It is also important that NPVOs strive to develop or increase the presence of these dimensions within themselves. For example, in terms of services and task, it is essential to continuously evaluate the effectiveness and impact of their actions in order to monitor the quality of the services provided over time and make it visible through data and certification. However, in order to gain trust and accountability NPVOs could, for example, not only make their economic and social budgets available—an action that many of them already undertake—but also proceed with the preparation of participatory budgets. Moreover, it is important that NPVOs engage in communicating and conveying the social value they generate also to those who are not their members or do not have direct contact with them. This means that clear and focused communication strategies should be implemented not only to recruit new members but also to be acknowledged by the community as a whole. However, being recognized as having the capacity to build networks and promote community development comes with risks as it creates expectations that, if not met, would result in disappointment and consequent deterioration of the reputation and value attributed to NPVOs. Likewise, they could use these findings to enhance their political role vis-à-vis public governments and the economic marketplace, as being considered trustworthy, value-bearers and innovators can increase the perception that they are more fit to successfully promote social change than other social actors.

Our findings also have implication at policy level. The main implication here is the need for government institutions and policy makers to consider NPVOs as valuable partners in the development of policies and interventions, beyond instrumental reasons. In fact, policy makers should be aware of the crucial role that NPVOs play at the social and cultural level, recognising that they are key to supporting social capital and socialising citizens into the sense of societal community.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the participants.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università del Salento within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

The research data is confidential.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Italian Psychology Association’s Ethics Code.