Issues in national politics in 2024

The year 2024 confirmed a global environment defined by pronounced political fragmentation, heightened electoral activity, and a deepening wave of autocratization that continued a 25-year trajectory. The sheer volume of key political events—from elections across all levels, to major governmental collapses, and the dramatic emergence of new opposition forces—underscored the turbulence of the year in politics. Democracies faced internal pressures from rising populist and anti-establishment movements, while economic challenges persisted, marked by inflationary pressures and variable growth rates across advanced economies. The overall narrative of 2024 centered on intense domestic political contests occurring against a backdrop of fundamental challenges to institutional stability and the established democratic order.

The growing political relevance of populist and anti-establishment parties and candidates could be seen across many of the countries included in the Yearbook. Although these parties have been gaining traction for several decades, their success reached new heights in a number of countries. In Portugal, for instance, the populist right Chega (Enough) experienced a significant surge in the legislative elections (Magone Reference Magone2025). In France, the Rassemblement National’s strong performance in the European Parliament (EP) election precipitated a snap legislative election where the party further increased both its vote share and its parliamentary representation (Bendjaballah & Sauger Reference Bendjaballah and Sauger2025). Another case in point is the Netherlands, where the radical-right Party for Freedom entered a coalition government at the national level for the first time (Otjes & de Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2025). On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States saw the electoral success of Donald Trump, who won a second presidential mandate (Katz Reference Katz2025). Populist parties were also successful in countries such as Slovakia, where the left populist Direction - Social Democracy (SMER-SD) won the general election and went on to form a government with Voice–Social Democracy and the ultranationalists of the Slovak National Party (Láštic Reference Láštic2025).

Besides the French case discussed above, populist right-wing parties also made significant gains in other countries during the EP elections, held between 6 and 9 June in 27 of the 37 cases covered in this volume. In the German contest, Alternative for Germany recorded substantial gains despite the numerous controversies surrounding the party (Kinski & Brause Reference Kinski and Brause2025). In Italy, Brothers of Italy, led by Giorgia Meloni, came in first, largely at the expense of its coalition partner, the League (Gallina & Biancalana Reference Gallina and Biancalana2025). Further examples of radical-right success included the first-time EP delegation of Chega in Portugal (Magone Reference Magone2025), the rise of the new far-right party The Party is Over (Se Acabó La Fiesta—SALF) in Spain (Bohigues & Sendra Reference Bohigues and Sendra2025), and the emergence of the AUR alliance (Alliance for the Union of Romanians) and SOS in Romania's EP elections (Stan & Zaharia Reference Stan and Zaharia2025). While the traditional center-right (European People's Party) and center-left (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats) maintained their dominance within the EP overall, they lost ground in several member states.

Economic performance displayed volatility in 2024 (The World Bank 2024). Among the largest economies, Austria experienced an economic contraction, with GDP shrinking by 1.2 per cent, and Germany confronted a persistent economic recession, with GDP shrinking for the second consecutive year. This fueled public discontent, intensifying disputes within the governing coalition regarding fiscal policy, notably debates over reforming the debt brake rule (Kinski & Brause Reference Kinski and Brause2025). They join Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and New Zealand as contracting economies in 2024. In New Zealand, the sluggish economy and high cost of living pressures led the new coalition government to focus on extensive cuts to the public sector, generating significant effects, especially in Wellington (Barker & Dreyer Reference Barker and Dreyer2025).

On average across the cases covered by the Yearbook, growth was 1.5 per cent. Beyond Malta, which had another year of strong growth around 6 per cent, the next best economies—Croatia, Denmark, Cyprus, Spain, and Poland—all grew at between 3 per cent and 4 per cent. Nevertheless, in Croatia, high inflation continued to be a persistent concern, driven by external factors like the war in Ukraine and increased public spending (Nikić Čakar & Raos Reference Nikić Čakar and Raos2025), while Spain enacted an “Omnibus Decree” encompassing economic measures, including the revaluation of retirement pensions and a temporary energy sector tax for 2025 (Bohigues & Sendra Reference Bohigues and Sendra2025). Ireland dug out of the large shrinkage of 2023 with positive growth near the average. Relative to the previous year, Australia, Latvia, and Iceland slowed considerably.

Despite a general easing of global inflationary trends, the cost of living and economic hardship remained a salient political issue in many countries, usually in connection with related topics such as housing affordability. The latter was a particularly relevant issue in Portugal (Magone Reference Magone2025), where it became one of the main subjects discussed during the legislative election. Increasingly acute housing shortages were also salient issues in other countries, including Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Ireland, among others (Arlow & O'Malley Reference Arlow and O'Malley2025; Dumont & Kies Reference Dumont and Kies2025; Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2025). The cost-of-living crisis and economic anxieties also dominated citizens’ priorities in Greece (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2025) and Japan (Hino et al. Reference Hino, Ogawa, Fahey and Liu2025).

A significant number of high-profile corruption scandals emerged across several countries, an issue that often became a central focus in the EP election campaigns. Specific examples include Malta, where a major hospital scandal led to multiple indictments (Fenech Reference Fenech2025); Portugal, where alleged corruption cases triggered a snap legislative election (Magone Reference Magone2025); and Spain, where various corruption allegations dominated the political agenda, including the Koldo case, which involved illegal commissions and irregularities surrounding public procurement (Bohigues & Sendra Reference Bohigues and Sendra2025). Broader controversies reflecting elite misconduct also included alleged cases of opaque procurement in Slovenia (Krašovec Reference Krašovec2025), alongside ministerial resignations concerning the possible misuse of public funds in Latvia and Sweden (Ikstens Reference Ikstens2025; Widfeldt Reference Widfeldt2025). Another significant event was the clemency scandal in Hungary, which involved President Katalin Novák pardoning a convicted official linked to child abuse (Baranyai et al. Reference Baranyai, Gyulai and Papp2025).

Deep-seated concerns over the rule of law and judicial independence continued in countries like Poland, where the government confronted a “dual legal order” stemming from reforms and judicial appointments made by the previous administration (Jasiewicz & Jasiewicz-Betkiewicz Reference Jasiewicz and Jasiewicz-Betkiewicz2025). In Slovakia, reforms to the Penal Code were widely criticized for weakening anti-corruption tools (Láštic Reference Láštic2025), while in Slovenia, tensions were fueled by reports of political pressure on the judiciary by the main opposition party and on the Court of Auditors by the government (Krašovec Reference Krašovec2025). Last, the annulment of the presidential election in Romania by the Constitutional Court was highly controversial, raising issues of institutional legitimacy given that the decision was rendered only after the vote, based on limited evidence, and issued by justices appointed by the parties the winning candidate had opposed (Stan & Zaharia Reference Stan and Zaharia2025).

Immigration continued to be a salient issue in many countries and served as a primary catalyst for political instability in the Netherlands, where it led to the collapse of the governing coalition (Otjes & de Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2025). Anti-migrant rhetoric was also a central theme of Trump's campaign in the United States and featured prominently in the legislative elections in France and Portugal, where it played a key role in the far-right's discourse (Bendjaballah & Sauger Reference Bendjaballah and Sauger2025; Katz Reference Katz2025; Magone Reference Magone2025). It also remained a polarizing issue in the United Kingdom, where anti-immigration riots and protests took place across England and Northern Ireland over the summer (Middleton Reference Middleton2025).

Finally, the fallout from the war in Ukraine and the ongoing conflict in the Middle East continued to shape debates across many Yearbook countries, though its impact was generally less pronounced than in previous years. Support for Ukraine remained a divisive issue in countries like Slovakia, where the newly elected government adopted a significantly less supportive stance towards Kyiv (Láštic Reference Láštic2025). Romania, in contrast, took a completely different position, signing a 10-year security agreement with Ukraine (Stan & Zaharia Reference Stan and Zaharia2025). The conflict also influenced broader security policies in Europe as evidenced by Sweden's accession to NATO in 2024 (Widfeldt Reference Widfeldt2025).

The state of democracy in 2024

The long-term trend of autocratization deepened in 2024, signaling that the global decline in democracy shows no sign of cresting. Drawing upon the Varieties of Democracy's Democracy Report 2025 (Nord et al Reference Nord, Angiolillo, Good God and Lindberg2025), the set of countries within this Yearbook had mixed democratic performance.

Using the Regimes of the World typology (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018), 21 cases remained categorized as Liberal Democracies, including Australia, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. However, in France, Italy, and the Netherlands, uncertainty about the classification means that they may be part of the lower Electoral Democracy category.

The year 2024 includes several recent backsliders among those that had traditionally held high democratic status. Israel and Slovakia lost their status as liberal democracies in 2023, the former after more than 50 years as a Liberal Democracy. Romania also shows signs of decline: despite having undergone a period of democratization before 2020, the country was again identified as autocratizing in 2024; this was exacerbated by the Constitutional Court's decision to annul the first round of presidential election results, which, as mentioned earlier, further polarized the electorate (Stan & Zaharia Reference Stan and Zaharia2025). Hungary remained an Electoral Autocracy, the only country in the Yearbook to hold this status. Conversely, some countries demonstrated resilience: Poland continued its episode of a democratic U-turn by trending upwards. Czechia, having undergone deteriorations between 2017 and 2021, exhibited improvements in 2024 regarding access to justice, parliamentary effectiveness, and freedom of expression, bringing it close to the democratizer label. Overall, the total number of countries undergoing autocratization remained higher than those undergoing democratization.

Elections and referenda in 2024

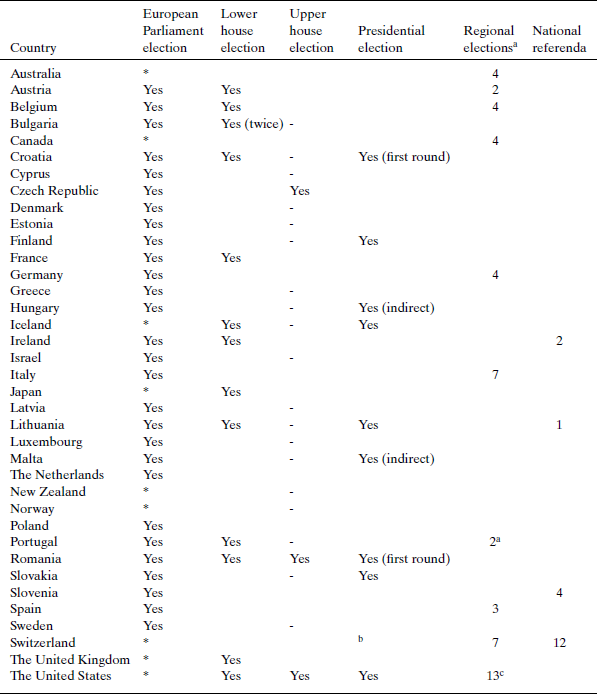

According to the data, 2024 was an “electoral year” for most of the 37 countries discussed in this year's volume (Table 1).Footnote 1 The main reason is that voters in all 27 European Union member states (representing 73 per cent of the cases included) were called to elect their representatives to the EP. In addition, general elections were held in 14 countries (38 per cent). Among these, Romania and the United States held elections for both the lower and upper houses, whereas only the second chamber was renewed in the Czech Republic. In 11 countries (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Lithuania, Portugal, and the United Kingdom), the legislative elections concerned only the first chamber. Bulgaria was a special case, as two parliamentary elections were held during the year (in June and October).

Table 1. Elections and referenda in 37 countries in 2024

Notes: Upper house elections are only reported for the following countries: Australia, the Czech Republic, Japan, Italy, the Netherlands, France, Poland, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. Regional elections are reported for federal (i.e., state elections) and decentralized countries. Only referenda at the national level are counted.

*Indicates that the country is not a member of the European Union.

-Indicates that there is no upper chamber. Presidential elections are reported only if a country has a (as if) directly elected president.

a Two elections were held in the two autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira.

b The Swiss president is annually elected by the Parliament. The elections are not competitive and follow consociational logics.

c Gubernatorial elections in US states.

Citizens voted to choose their president in Croatia, Finland, Iceland, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and the United States. It is worth noting, however, that the Croatian and Romanian presidents were not ultimately chosen in 2024, as only the first round of the presidential elections took place that year, with the decisive second round held in 2025.

Focusing on federal and strongly decentralized states, regional (or equivalent) elections were held in nine countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. Excluding gubernatorial elections in the United States, these countries held an average of 4.4 regional elections, with Italy and Switzerland recording the highest number (seven) and Austria the lowest (two). In addition, Table 1 also reports the two elections in Portugal's autonomous regions of the Azores and Madeira (Portugal is otherwise a unitary state).

Finally, (national) referenda only took place in four countries (i.e., same number as in 2023). There were two referenda in Ireland, one in Lithuania, four in Slovenia, and—consistent with the country's long tradition of direct democracy—12 in Switzerland. By comparison, Switzerland held only three referenda in 2023, after conducting 20 in 2021 (11 of which were nationwide ballot proposals).

A comparative overview of the elections and referenda held in the Political Data Yearbook’s countries in 2024 can be found in Table 1.

General elections held during 2024 directly affected prime ministerial turnover in Bulgaria (after the June election), France, Iceland, Lithuania, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. In Bulgaria, Dimitar Glavchev was appointed caretaker head of a non-partisan Cabinet following the failure of government talks to form a new Cabinet under outgoing Prime Minister (PM) Nikolai Denkov. In August, President Rumen Radev reappointed Glavchev as caretaker PM, who remained in office until January 2025. In France, President Macron dissolved the Parliament and called early elections after his party's poor performance in the EP elections, leading to political instability that resulted in the appointment of three PMs (Attal, Barnier, and Bayrou) from July onwards. In Iceland, a new three-party coalition took office in December, the same month that Gintautas Paluckas was invested as PM in Lithuania, succeeding Ingrida Šimonytė. In Portugal, center-right candidate Luís Montenegro became PM following the March elections and the defeat of the Socialist Party. In the United Kingdom, the Labour Party won the general election, and Keir Starmer became head of a single-party majority Cabinet, which replaced the Conservative Sunak Cabinet.

In Ireland, the change of PM resulted from intra-party turnover rather than a government alternation, while in the United States, Donald Trump defeated incumbent President Joe Biden, returning to the White House after four years; he officially assumed office in January 2025.

General elections led to a change of the chief executive in 54 per cent of cases. Among parliamentary and semi-presidential countries, the largest losses in lower house elections for the incumbent party or electoral coalition occurred in the United Kingdom, where the Conservatives lost 19.9 per cent of votes. In France, Together!, the party of President Macron and PM Borne, lost 16.3 per cent of votes, roughly three percentage points more than the Socialist Party in Portugal (−13.4 per cent). In Iceland, PM Benediktsson's Independence Party lost 5 per cent, similar to Šimonytė’s Homeland Union–Lithuanian Christian Democrats in Lithuania (−6.9 per cent). In the United States, President Biden's Democratic Party lost just 0.1 per cent of the popular vote in the House of Representatives and 4 per cent in the Senate.

Overall, 2024 and 2023 were characterized by similar levels of electoral instability. In 2023, 73 per cent of legislative elections led either to a change in the chief executive or to substantial losses for the parties that retained the prime ministership. In this respect, 2023 and 2024 differed from 2022, when almost two-thirds (65 per cent) of incumbent Cabinets remained in office following general elections (cf., Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Mustillo and Vercesi2024).

Changes in the composition of Cabinets and Parliaments in 2024

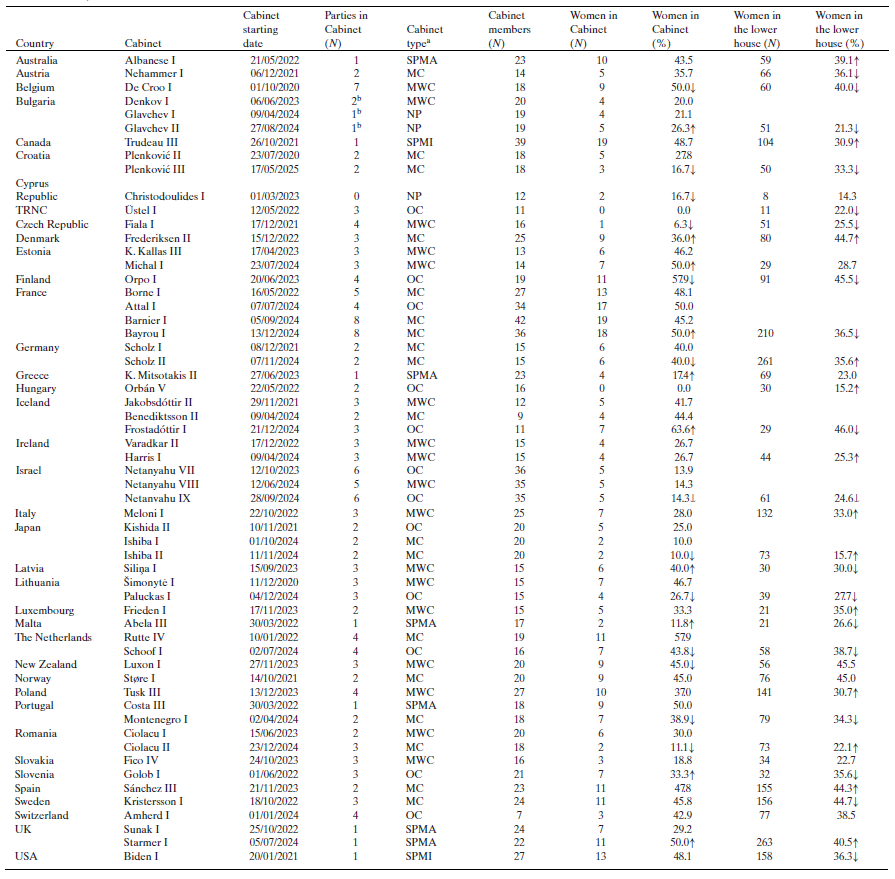

Table 2 presents the composition of Cabinets and Parliaments in the 37 Yearbook countries, along with changes that occurred in 2024. The figures show that 20 new Cabinets—two more than in 2023 and one less than in 2022—were installed in 14 countriesFootnote 2 (13 in 2023). These countries are Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, and the United Kingdom. It is also worth noting that the PM changed in 13 cases, corresponding to 65 per cent of instances of a new Cabinet.

Table 2. Cabinets and gender composition of Cabinets and Parliaments in 37 countries on 31 December 2024 (or on the last day in office for Cabinets terminated earlier in 2024)

Notes: SPMA, single-party majority Cabinet; SPMI, single-party minority Cabinet; MNC, minimum winning coalition; OC, oversized coalition; MC, minority coalition; NP, non-partisan. The arrows indicate lower (down) or higher (up) percentages of women in government and Parliament, compared to 31 December 2023. TRNC, UK, and USA mean, respectively, the following: Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.

a Based on the seats controlled in the lower house.

b The Cabinet was mostly made up of independent members.

Croatia, Germany, and Israel are the only three cases in which a change of Cabinet did not result in a change of head of government. In Croatia, incumbent PM Plenković formed a new Cabinet following the April elections. In contrast, the German Chancellor Scholz began leading a caretaker minority coalition of Social Democrats and Greens in November, after dismissing Finance Minister and Free Democrats’ leader Lindner, which prompted the Free Democrats to withdraw from the coalition. Similarly, the Israeli PM Netanyahu led three Cabinets with different coalition compositions.

Higher levels of Cabinet turnover occurred in France—with three new Cabinets in 2024—and in Bulgaria, Iceland, Israel, and Japan, each of which saw two. However, only in France and Iceland did all new Cabinets come with a change of PM. In Bulgaria and Japan, PMs Glavchev and Ishiba, respectively, took office before the elections and remained in post afterwards. Across 38 political systems (counting both the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, TRNC), 74 per cent (N = 28) did not experience a change at the apex of the executive. Together with the aforementioned data about the impact of general elections on Cabinet change, these figures indicate that in 2024, prime ministerial stability was the norm, except in post-electoral contexts.

Excluding Switzerland and presidential systems (i.e., the Republic of Cyprus and the United States), 57 per cent of cases (N = 20, including the TRNC) experienced no Cabinet change during 2024. Austria and Belgium are part of this group despite holding general elections, as these led to new Cabinets only in early 2025. Compared with 2023, Cabinet turnover was slightly higher in 2024: In the previous year, 24 political systems had seen no change of Cabinet. The 2024 figure, however, was almost identical to that of 2022, when 19 countries recorded Cabinet continuity.

With regard to Cabinet types as of the last day in office, the most common type in 2024 was the minority coalition, accounting for 31 per cent of all reported Cabinets (N = 18 out of 58). The minimum winning coalition was the second most frequent type (17 Cabinets, 29 per cent), followed by oversized coalitions (12 Cabinets, 21 per cent). Single-party Cabinets were recorded in only eight cases: six were majority Cabinets (10 per cent of the total, in Australia, Greece, Malta, Portugal, and twice in the United Kingdom) and two were minority Cabinets (Canada and the United States). Non-partisan Cabinets (5 per cent) governed in Bulgaria (two Cabinets) and in the Republic of Cyprus (one Cabinet). Taken together, most Cabinets (46 of them, i.e., 79 per cent) were coalitional, whereas only eight (14 per cent) were single-party. In terms of parliamentary support (excluding non-partisan Cabinets), 36 per cent (N = 20) did not command a majority in the lower chamber, while 64 per cent (N = 34) did. Among majority Cabinets, 29 (83 per cent) were coalitions, and more than half of these (59 per cent) were minimum winning coalitions (they required all coalition partners to secure more than half of the parliamentary seats).

With regard to Cabinet personnel, in 2024, there was a further increase in the average percentage of women in ministerial positions, which moved from 30 per cent in 2022 to 32 in 2023 and 34 in 2024 (Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Mustillo and Vercesi2024). Comparing the situation on 31 December 2023 and 31 December 2024, 10 out of 38 political systems (26 per cent) recorded an increase in women's descriptive representation in Cabinet, while in 13 systems, the proportion declined, and in 15 (39 per cent) it remained unchanged.

Only two Cabinets did not include women ministers: The Üstel I Cabinet in the TRNC and the Orbán V Cabinet in Hungary. In contrast, the Finnish Orpo I and Dutch Rutte IV Cabinets, with 57.9 per cent both, and the Icelandic Frostadóttir I Cabinet, with 63.6 per cent, displayed the highest levels of female representation. Only nine Cabinets were parity Cabinets, that is, Cabinets with at least 50 per cent of women: De Croo I in Belgium, Michal I in Estonia, Orpo I in Finland, Attal I in France, Frostadóttir I in Iceland, Rutte IV in the Netherlands, Costa III in Portugal, and Starmer I in the United Kingdom. In absolute terms, the Cabinets with the highest number of women were Trudeau III in Canada and Barnier I in France, with 19 women ministers (on a total of 39 and 42, respectively).

Data on women's descriptive representation in the lower house at the end of 2024 indicate that, on average, about one-third of MPs were women (33 per cent, compared to 32 per cent in 2023). Consistent with established patterns, Nordic countries ranked at the top: Iceland (46 per cent), Finland (45.5), Norway (45), and Denmark and Sweden (44.7). New Zealand also belonged to this top group, matching Finland's figure. Once again, the highest absolute number of women MPs was recorded in Germany (261), followed by France (210). At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Republic of Cyprus had the lowest proportion (14.3 per cent), slightly below Hungary (15.2) and Japan (15.7). It is worth noting that Japan was at the bottom of the ranking in 2023 (10.3), prior to the 2024 general elections (Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Mustillo and Vercesi2024).

The positive trend in women's representation observed in 2023 did not continue in 2024. Only a minority of Parliaments experienced an increase in the proportion of women in the lower house—14 assemblies, or 37 per cent. In 17 cases (45 per cent), the share of women declined, while in seven cases (18 per cent) it remained unchanged. Overall, the absence of a declining trend was observed in just 55 per cent (N = 21) of Parliaments, a figure significantly lower than in 2023, when 84 per cent (N = 32) did not show negative trends (Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Mustillo and Vercesi2024).

The format of the Political Data Yearbook

As usual, the Political Data Yearbook issue presents data and information on political changes and events in 37 countries. With regard to Cyprus, the report deals with both the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The data cover the whole of 2024, from 1 January to 31 December 2023. For consistency's sake among issues, country reports follow the following core structure:

-

• Introduction;

-

• election report (presenting information on European, parliamentary, presidential, and regional elections as well as referenda);

-

• Cabinet report;

-

• Parliament report;

-

• political party report;

-

• institutional change report;

-

• issues in national politics.

More specifically, sections on parliamentary reports discuss both lower and upper houses elections, if relevant to the country. When a country experienced Cabinet turnover and/or total parliamentary renewals, data cover all Cabinets and Parliaments at issue. The political party report, in turn, presents institutional and leadership changes in major or minor parties. The institutional change report is mainly qualitative and addresses changes to the country's institutional settings, if any. If a heading is not included, the readers should interpret this as an indicator that the issue was not relevant for that country in the period covered by this Political Data Yearbook issue.