1.1 Prospects of Data-Intensive Studies in English Linguistics

This volume focuses on data-intensive studies and methods in English linguistics.Footnote 1 Researchers of the English language have been leaders in adopting and developing novel empirical methods in the humanities for more than a century, making it therefore fitting to explore this theme in a book series on English linguistics. The field has seen numerous pioneers in innovative quantitative research methodology, starting with Otto Jespersen’s (Reference Jespersen1924) empirical work that highlights the “direct observation of living speech” (7) and Randolph Quirk’s launch of the Survey of English Usage, which builds on empirical observations and the use of large, stylistically balanced corpora (Quirk Reference Quirk1960).

This pioneering spirit continued with the advent of the first digital text corpora, both synchronic and diachronic, from the 1960s and 1970s onward. Groundbreaking digital materials were collected to facilitate the descriptive study of English, initially by Nelson Francis and Henry Kučera at Brown University and later in various endeavors worldwide (e.g., Svartvik et al. Reference Svartvik, Eeg-Olofsson, Forsheden, Oreström and Thavenius1982; Rissanen Reference Rissanen and Svartvik1992; Greenbaum and Nelson Reference Greenbaum and Nelson1996; Granger Reference Granger2003; Davies Reference Davies2009). More recently, the openness and progressive spirit toward data-intensive approaches have been evident in the statistical turn in linguistics. Many insights into the quantification of linguistic variability have emerged through the development and testing of novel statistical tools on data and questions related to English (Gries Reference Gries2009; Kortmann Reference Kortmann2021).

This volume aims to examine the state-of-the-art of current data-intensive approaches in English linguistics today, and it builds on the idea that we can only look ahead to future developments by understanding the past and the present. The research context for the volume is recent developments in digitalization and data-intensive technologies, including digital humanities in English.

The current growing interest in digital tools and computational methods can be seen in a number of earlier publications spanning digital linguistics, data modeling, and social media data, among other related topics. Dealing with the digital transformation in fundamental research in general, a recent report by the Humanities and Data Science Special Interest Group based at the Alan Turing Institute in the UK, outlines future steps for the fuller integration of digital tools in the humanities (McGillivray et al. Reference McGillivray, Alex, Ames, Armstrong, Beavan, Ciula, Colavizza, Cummings, De Roure, Farquhar, Hengchen, Lang, Loxley, Goudarouli, Nanni, Nini, Nyhan, Osborne, Poibeau, Ridge, Ranade, Smithies, Terras, Vlachidis and Willcox2020). It identifies a number of contact points on how to increase collaboration between any disciplines in the humanities and data science/artificial intelligence (AI). The recommendations emphasize the need for common methodological terminology, transparency, and openness in research at the intersection of humanities and data science. The report also highlights the importance of reproducible research, robust technical infrastructure, interdisciplinary funding policies, and comprehensive training and career development opportunities for researchers.

Empirical studies include, for instance, Suhr, Nevalainen, and Taavitsainen (Reference Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019), in which the contributions explore the overlap of corpus linguistics, digital linguistics, and digital humanities in an effort to discuss the benefits and challenges of “big data” (increasing size of data), “rich data” (multifaceted co[n]textual data), and “uncharted data” (adaptation of existing datasets to new uses). Adolphs and Knight (Reference Adolphs and Knight2020) offer a handbook-length overview of the intersection of English and digital humanities. Rüdiger and Dayter (Reference Rüdiger and Dayter2020) focus on analyzing multimodal social media data using corpus linguistic methods: they call for increased interdisciplinarity to cross-fertilize the different approaches to corpus-based social media research, and for discussion on data access and research ethics in relation to social media data (also Di Cristofaro Reference Di Cristofaro2024). Flanders and Jannidis (Reference Flanders and Jannidis2019) zoom specifically into the topic of data modeling in digital humanities research, discussing the evolving nature of what data today is and how we can employ computers to help us navigate the immense and intricate datasets in digital humanities. Further, the Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence special issue focusing on computational sociolinguistics, edited by Grieve and colleagues (Reference Grieve, Hovy, Jurgens, Kendall, Nguyen, Stanford and Sumner2023), offers a multitude of articles aiming to use computational techniques to understand language variation and change in English but also other languages. While there are a few recent volumes that revolve around language and digital tools, they narrowly focus on only one branch of linguistics, such as discourse analysis (Vásquez Reference Vásquez2022), cognitive linguistics (Tay and Pan Reference Tay and Molly2022), and second-language acquisition and pedagogy (Lütge and Merse Reference Lütge and Merse2021; Sukhova, Dubrovskaya, and Lobina Reference Sukhova, Dubrovskaya and Lobina2021).

This volume builds on the idea that the development of data-intensive approaches and digital tools are changing the way we understand and do research today and tomorrow. They are an inescapable part of research and have great potential for providing novel ways of doing research in English linguistics. Recent years have seen a range of innovative uses of data-intensive methods and tools in English linguistics, including Huang and colleagues’ (Reference Huang, Guo, Kasakoff and Grieve2016) study of very large social media data in dialectology aiming at fixing the underrepresentation of certain geographic areas in the study of regional dialects. Similarly, Grieve, Nini, and Guo (Reference Grieve, Nini and Guo2016, Reference Grieve, Nini and Guo2018) have provided novel information on the emergence of neologisms, and their studies show when and where novel lexis in English emerges, something which was deemed to be an impossible task a few decades ago (cf. Milroy and Milroy [Reference Milroy and Milroy1985: 370] writing that “direct observation of the actuation process may be difficult, if not impossible”). Data-intensive studies have also provided novel angles to the study of World English varieties (Szmrecsanyi, Grafmiller, and Rosseel Reference Benedikt, Grafmiller and Rosseel2019), to language change in social networks (Laitinen, Fatemi, and Lundberg Reference Laitinen, Fatemi and Lundberg2020), and to specific questions in grammar, such as the use and variation of modal auxiliaries in English (Depraetere et al. Reference Depraetere, Cappelle, Hilpert, De Cuypere, Dehouck, Denis, Flach, Grabar, 17Grandin, Hamon, Hufeld, Leclercq and Schmid2023). In addition, significant advances have been witnessed in making available extremely large collections of dialectal spoken data by utilizing social media sources, such as transcripts of YouTube videos from Australia and New Zealand, among others (Coats Reference Coats, Busse, Dumrukcic and Kleiber2023, Reference Coats2024). What is more, these studies and other similar investigations show that if and when carefully utilized, data-intensive tools and methods may also lead to completely new questions, potentially transforming the ways we do research.

It is highly likely that the development of digital methods will continue to impact research in many disciplines. A significant digital breakthrough that coincided with the making of this volume was the release of tools leveraging large language models (LLMs). The development of LLM solutions, and generative artificial intelligence more broadly, offer substantial potential for data-intensive approaches in English linguistics. Among the most prominent LLM applications is OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT), a chatbot capable of generating natural language text and providing human-like responses to queries and prompts. However, numerous other solutions also exist (Claude AI, Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, etc.).

Generative AI represents a disruptive technology par excellence, and it can have profound implications for fundamental research across various disciplines, particularly those focused on human-generated language and its variability. A recent editorial in Nature Machine Intelligence argues that the impact of LLMs on the scientific study of languages could be substantial, suggesting that “the field of linguistics is clearly affected by the development of tools so powerful that their output can easily be confused with human-generated texts” (Nature 2023).While we acknowledge that distinguishing genuinely human production from automatically generated content poses a potential challenge, it is one that can, ironically, be addressed with advanced digital tools that would be designed to differentiate authentic communication from fabricated content. To illustrate, a recent article by Walters (Reference Walters2023) suggests that various tools, Copyleaks, TurnItIn, and Originality.ai, in particular, are capable of reaching high accuracy in discerning AI-generated from human-generated writing. We suggest, however, that a more relevant question would be to ask how English linguistics could benefit from these models and what data-intensive study focusing on statistical pattern discovery can offer for the future development of LLMs. The most obvious opportunities include providing more nuanced quantitative information of sociolinguistic variability in general, as now the GPT tools are trained with very large material of hundreds of billion words, but we do not know the full scope or representativeness of these training data in terms of situational or sociolinguistic variation. As of right now, the most substantial impact of data-intensive approaches seems to be related to providing nuanced quantitative information of the range of diverse settings in which language is used, encompassing not only register and situational variation but also domains and sociolinguistic categories (cf. Grieve et al. Reference Grieve, Bartl, Fuoli, Grafmiller, Huang, Jawerbaum, Murakami, Perlman, Roemling and Winter2025). This perspective is echoed by Anthony (Reference Anthony2023), who suggests that LLMs could offer a deep and nuanced understanding of language use across various domains and registers, provided these tools are fine-tuned and integrated into analytical toolkits by linking them directly to datasets utilized by researchers.

Predicting is always challenging, and predicting the full impact of LLMs is even more challenging, given the speed of the developments in the field, but we have only seen the first empirical studies related to LLMs in empirical language studies. Uchida (Reference Uchida2024), for instance, argues that while LLMs cannot fully replace traditional tools for rigorous academic research, they can identify general linguistic trends. Additionally, the author argues that LLM tools can be valuable for educational purposes, effectively assisting learners in understanding linguistic patterns and in practicing oral production, for instance.

The developments of LLM technologies are without a doubt interesting, but the integration of digital and technological insights into the study of the English language is not restricted to them. As the contributions in this volume show, digital transformation is far more extensive than one single technology, and the contributions include a range of other data-intensive approaches in research.

1.2 What Are Data-Intensive Methods?

Building on the idea that methodological development and digitalization will accelerate and foster multi- and interdisciplinary research, this volume presents an overview of a range of data-intensive research in English linguistics. But what do we mean by data-intensiveness? Given that when applied to linguistic research, the term can encompass a range of empirical approaches, the following discussion outlines a number of essential characteristics for understanding it.

First and foremost, the broadest common definition is that data-intensive studies in English linguistics leverage large volumes of language data. This reliance on ever larger datasets has been a given fact in English linguistics for some time (Biber and Reppen, Reference Biber and Reppen2015), so that some of the largest balanced digital corpora are English corpora. An additional angle in using large digital corpora is they are often employed in combination with other computational and digital techniques to analyze, model, and understand patterns of language in use. For instance, various advanced quantitative methods have become increasingly prominent with the development of large digital corpora and with the advancement in statistical techniques in recent years (Larsson, Egbert, and Biber Reference Larsson, Egbert and Biber2022), but as shown in this chapter, we propose that being data-intensive means going beyond advanced quantitative methods.

Second, to clearly distinguish data-intensive research in this discipline from purely computational and NLP (natural language processing) approaches, we argue that a crucial common denominator is that data-intensive contributions in this volume are grounded in solid theoretical foundations in the study of English, its structure, and its use in context. Being data-intensive, as opposed to purely computational, means that researchers might consider the diachronic embedding of the phenomena under investigation or understand the boundaries of sociolinguistic variation within English (cf. Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2012, on the principle of accountability and circumscribing variable contents). Our informal observations of recent computational and NLP studies that deal with English suggest that such studies do not always meet the methodological rigor of English linguistics. For example, studies of lexical emergence and neologisms in online environments often use word lists from commercial dictionaries (e.g., Urbandictionary.com, NoSlang.com), as opposed to engaging in close readings of texts to identify true neologisms (e.g., Del Tredici and Fernández Reference Del Tredici, Fernández, Bender, Derczynski and Isabelle2018; Zhu and Jurgens Reference Zhu, Jurgens, Toutanova, Rumshisky, Zettlemoyer, Hakkani-Tur, Beltagy, Bethard, Cotterell, Chakraborty and Zhou2021). This means that while these studies excel in computational modeling of the phenomena, there is a risk that they lack a deeper understanding of the diachronic depth or the sociolinguistic embedding necessary for observing variation reliably.

Third, data-intensive studies employ advanced tools and computational methods to address research questions in the field. These tools and methods can encompass any type of digital methods at any stage of the research process. During the material collection phase, data-intensive methods can be used for effectively collecting, curating, and preprocessing data. Similarly, these methods may involve sophisticated data analytics, artificial intelligence, computational modeling during the analysis phase, or drawing insights from data visualization in digital storytelling. This distinction is crucial as we aim to differentiate data-intensive methods in English linguistics from purely computational linguistic approaches, which are based on different epistemic and theoretical foundations (Church and Liberman Reference Church and Liberman2021).

The contributions to this volume reflect a deep-rooted orientation in English linguistics. The studies included are not purely computational; nor do they use digital methods for their own sake. Instead, each contribution addresses the core question of data-intensiveness: How do the data-intensive and digital methods used help authors answer research questions that are firmly grounded in theoretical foundations in English linguistics? This approach raises further questions about the potential of these tools and technologies to advance English linguistics and keep pace with other linguistic disciplines that have widely adopted digital and computational methods.

The fourth characteristic is closely linked to the previous ones, arising from the fact that various online data sources have opened up numerous opportunities for digital approaches to utilize large-scale data from online sources. We propose that a key aspect of data-intensive studies is the emphasis on data quality. Researchers should avoid using indiscriminate data dumps, which are often large and random samples, and instead carefully consider the representativeness of their data (Biber Reference Biber1993; Davies Reference Davies, Biber and Reppen2015). What do their data represent, and what do they not represent? Is the dataset balanced, or is it skewed toward specific genres, dialects, or demographics?

Lastly, in addition to the various statistical techniques (univariate and/or multivariate frequentist and Bayesian approaches alike), data-intensive methods in linguistics represent a convergence of linguistic analysis with modern computational methods, such as machine learning and utilizing insights from computer sciences. These approaches can potentially allow researchers to not only handle even greater amounts of linguistic data but also uncover patterns and insights that were previously inaccessible (cf. a recent volume of data-intensive quantitative studies on modals by Depraetere et al. Reference Depraetere, Cappelle, Hilpert, De Cuypere, Dehouck, Denis, Flach, Grabar, 17Grandin, Hamon, Hufeld, Leclercq and Schmid2023).

Another example of combining English linguistics with computer science is broadening the horizon of corpus linguistics to account for social, interactional connections and network ties on a massive scale. Unlike spoken corpora, such as the spoken components of the British National Corpus and certain sociolinguistically oriented diachronic corpora like the Corpus of Early English Correspondence (e.g., Nevalainen, Palander-Collin, and Säily Reference Nevalainen, Palander-Collin and Säily2018), social interactional information is typically not included in corpus metadata. Standard English corpora predominantly use text type as the primary level of coding in metadata. This contrasts with recent data-intensive sociolinguistic efforts that use representative data from social media, where the primary level of metadata coding is the individual, identifiable through a user ID (Laitinen and Fatemi Reference Laitinen, Fatemi, Rautionaho, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Nurmi2022). These network-based approaches are rooted in the idea that the main purpose of online communication is to form communities and networks, making the connections between people the focal point of analysis. Establishing these social connections in extremely large-scale data requires handling very complex data, necessitating collaboration beyond linguistics with other disciplines, such as data science. This leads to deeper integration of linguistics with digital methods for effective data handling.

1.3 Desiderata for Data-Intensive Future in English Linguistics

Given the considerable development of digital methods across nearly all research areas, data-intensiveness in English linguistics involves a willingness to digitize all aspects of the research process that can be meaningfully digitized. Digital technologies are transforming every aspect of the research process, a phenomenon we describe as quantitative squared. If fully adopted, this could lead to significant reorientations in research methodologies.

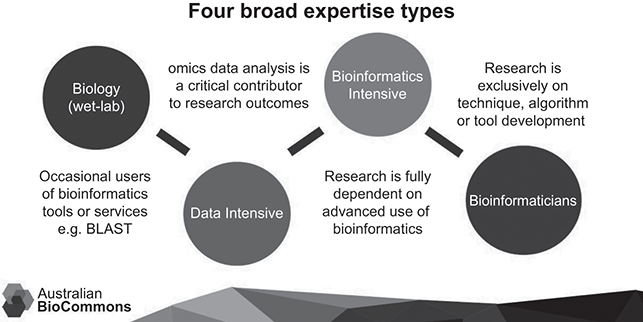

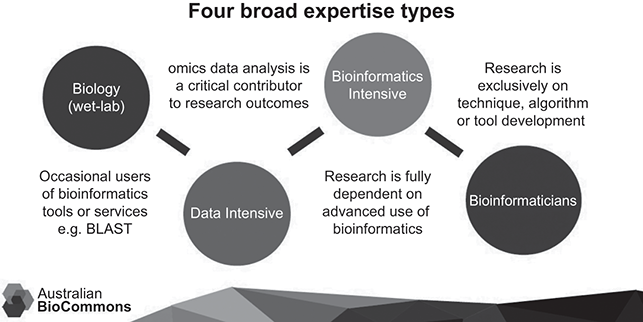

This transformation is illustrated by a visualization depicting a similar digital shift in biosciences. Figure 1.1 (from Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Coddington, Davis, Duncan, Francis, Hall, Kemp, Manos, Nelson, Nisbet, Price, Stevens and Lonien.d.) visualizes the four broad expertise types in a major digital infrastructure project of Australian BioCommons (for a more detailed depiction of the expertise types, see Francis and Christiansen Reference Francis and Christiansen2024). It distinguishes four types of expertise based on the extent to which researchers adopt digital and data-intensive methods and tools.

Figure 1.1 Digital transformation of biosciences and its implications for expertise types (Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Coddington, Davis, Duncan, Francis, Hall, Kemp, Manos, Nelson, Nisbet, Price, Stevens and Lonien.d.).

Figure 1.1Long description

The first phase involves wet lab biology with occasional users of bioinformatics tools or services. The second phase is data intensive in the sense that omics data analysis is a critical contributor to the research outcomes. In the third phase, labelled bioinformatics intensive, the research is fully dependent on advanced uses of bioinformatics. In the final phase bioinformaticians are required as research is exclusively on technique, algorithm or tool development.

Despite the clear epistemic differences between linguistics and biosciences, the visualization illustrates how a field can transform itself through ongoing digital change. Transitioning from its origins in a wet lab to adopting data-intensive methods means that researchers not only use these methods more extensively but also that the field itself must evolve to develop the necessary tools, methods, and algorithms. This transformation requires substantial investments in computing power, data management, software development, and deployment, and according to a recent strategy document (Francis and Christiansen Reference Francis and Christiansen2024), it also involves investments in upskilling researchers in in scripting and coding (also Schweinberger, Chapter 10). Researchers could also benefit from simple-to-use service platforms that would enable developing data collection and analysis pipelines that could then be further developed on a broader scale in collaborative projects.

The plan is ambitious, and comparisons between biosciences and English linguistics should be approached with caution, but if a similar approach was adopted in the study of the English language, the initial phase in Figure 1.1 is comparable to qualitative language analyses that occasionally use corpus evidence. In this phase, research is empirical but not necessarily data-intensive, as researchers might occasionally use digital corpora and rely on both quantitative and qualitative tools. The primary focus of the research involves working with small samples, akin to biologists in a wet lab setting.

The second phase is the data-driven phase, where data analytics tools become essential to research. In English studies, it would be practically impossible to pursue a research agenda without basic digital tools and methods, such as concordances, clusters, n-grams, and keywords. According to our informal observations, most research in English linguistics today, particularly under the auspices of key international networks like the International Society for the Linguistics of English (ISLE) and the International Computer Archive of Modern and Medieval English (ICAME), falls within this data-driven phase.

Most contributions in this volume fall under the third phase depicted in Figure 1.1. This phase signifies that research is fully dependent on advanced data analytics, yet still guided by field-specific research questions. The methods employed are diverse, including big data analytics (Kretzschmar et al., Chapter 2), machine learning (Nasseri, Chapter 9), and advanced statistical techniques such as Bayesian methods or conditional inference trees (van Eyndhoven, Gotthard, and Filgueira, Chapter 4; Rautionaho and Meriläinen, Chapter 7; Ruohonen and Rudanko, Chapter 8). Additionally, some studies utilize computational methods like word embeddings for collocational analysis (Schneider, Chapter 5). Other contributions leverage advances in natural language processing (NLP) and employ sentiment analysis to address questions that have traditionally relied on manual or simple data-driven methods (e.g., the study of word-formation processes by Arndt-Lappe, Beliaeva, and Martin, Chapter 6).

The final step in the process depicted in Figure 1.1 involves a significant shift toward research that is primarily focused on algorithm and tool development for English studies. This field has previously seen efforts to develop advanced digital tools and methods, such as POS taggers and parsers. Notable examples include the development of taggers (e.g., the Multidimensional Analysis Tagger by Nini Reference Nini, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019), the parsing of various historical corpora like the Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence (by Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Nurmi, Warner, Pintzuk and Nevalainen2006; also PCEEC2), and the creation of normalization tools to manage heterogeneous spellings in historical corpora using the VARD tool (Baron and Rayson Reference Baron and Rayson2008). However, a broader shift toward true data informatics in English linguistics has yet to occur. The development of generative AI suggests that the near future will likely see numerous attempts to better harness computational power for data informatic approaches. The focus may then shift to how best to use LLMs for studying the English language and, importantly, how to understand the inner workings of these models so that English linguists retain control of the process.

Given the volume’s focus on data-intensive approaches, it is unsurprising that none of the contributions deal with algorithm development. However, increased digitalization is expected to lead to greater efforts in this area. This potential shift toward greater use of data analytics is also likely to foster increased multi- and interdisciplinary collaboration. Multidisciplinary approaches involve several disciplines working together to solve questions in one field, each providing different perspectives on a research problem. In contrast, interdisciplinary approaches are more holistic, integrating insights from numerous disciplines into solving research questions. The data-intensive future offers numerous opportunities to enhance both multi- and interdisciplinary collaboration. For instance, English studies could benefit from integrating insights from information and data visualization (see Sönning and Schützler, Reference Sönning and Schützler2023). Despite information visualization being an established field (e.g., there being journals, such as Information Visualization), its full and large-scale integration into English linguistics has not yet occurred, which is clearly seen in the fact that the contributors to the edited volume on data visualization of English language data mentioned previously are primarily linguists. Another area that could benefit from increased multi- and interdisciplinarity is the use of high-performance (or super-)computing. Given the increasing size and complexity of datasets, we should expect a greater number of truly interdisciplinary approaches in this domain as well.

The overarching issue in data-intensiveness is to strengthen the scientific rigor of English studies. This can be achieved in various ways, with one key element being the transparency of the empirical process to increase the replicability and reproducibility of studies and promote the reuse of data (Schweinberger, Chapter 10). Numerous disciplines have faced the so-called Replication Crisis (described in Sönning and Werner, Reference Sönning and Werner2021; Schweinberger and Haugh, Reference Schweinberger and Haugh2025), which highlights methodological issues arising from failures to replicate key observations and main conclusions. The crisis has two levels: reproducibility, which refers to whether other researchers can obtain consistent and similar results using the same original data and methodology, and replicability, which points to the consistency of results when other researchers work with similar but not necessarily the same data and methods. Both are crucial for the generalizability of research findings. Data-intensive research can positively contribute to methodological transparency and data reuse. As highlighted in Schweinberger’s contribution, a key component of data-intensive research is the need for clear and comprehensive reporting of methods, data, and analytical techniques. This can be better supported by improved data and methods literacy and increased awareness of documentation and workflows when working with data.

1.4 On Digital Fetishism

Digitalization, however, is not without its problems, and the purpose of this volume is not only to present data-intensive approaches but also to foster dialog of how digital tools could benefit researchers. One significant concern is the rapid pace of digitalization, which may lead researchers to adopt tools and methods developed for purposes that do not align with the epistemological foundations of English linguistics. While the data-intensive development in English linguistics is largely seen as beneficial, there is a strong consensus – at least as strong as possible in academia – that the adoption of new digital tools and technologies should not come at the expense of theoretical and contextual knowledge (also Larsson, Egbert, and Biber Reference Larsson, Egbert and Biber2022).

Recently, closely similar views have been expressed in data feminism, which has emerged within data science as a critical approach that focuses on the close relationship between data and power (D’Ignazio and Klein Reference D’Ignazio and Klein2020). Data feminism aims at challenging how we perceive, count, and classify data, showing that data are not necessarily neutral or objective. This approach also calls for researchers in all data-intensive fields to open up the computational systems that produce prejudiced (and sometimes outright racist) results and take a critical look into datafication, the collection and commodification of our data collected today.

Critical views on data have been presented in English linguistics for decades. As early as the late 1980s, Rissanen (Reference Rissanen1989) highlighted the potential pitfalls of the first large-scale diachronic text corpora, emphasizing the need for analyses to be supported by solid theoretical, contextual, and historical knowledge. More recently, Kortmann (Reference Kortmann2021) discussed the implications of the quantitative turn, underscoring the importance of integrating theoretical knowledge and qualitative analyses with advanced quantitative methods.

A crucial component of data-intensive research is that novel data and methods should not be utilized at the expense of theoretical knowledge and the sociocultural and historical contextualization of the phenomena being studied. Being data-intensive does not mean an excessive fixation on technology. The use of digital tools may lead to digital fetishism, an excessive fixation on data and digital solutions themselves, where the use of tools and methods is not justifiable or suitable for solving research questions (cf. Mair Reference Mair2006 on corpus fetishism). Therefore, it is important for researchers to carefully consider which tools and methods are used, for what purposes they were developed, and by whom. The use of digital methods and data-intensive approaches should aim at providing further empirical angles to research questions (cf. the critical approaches to data capitalism in the humanities in general in Ampuja Reference Ampuja and Stocchetti2020; Miconi Reference Miconi2024).

1.5 Overview of the Volume

This volume consists of ten chapters, each approaching data-intensive methods from different angles. The first chapters focus on questions related to data, paying special attention to data collection, curation, enrichment, and distribution. The chapters introduce new ways of handling existing datasets (van Eyndhoven, Filgueira, and Gotthard, Chapter 4; Kretzschmar, Olsen, Olsen, and Ireland, Chapter 2) and new corpus tools (Bridwell and Ireland, Chapter 3). The focus then shifts to data-mining methods and quantitative and/or interpretative tools to be used in the analysis. The next chapters introduce data-intensive methods to handle semantics (Schneider, Chapter 5), lexis and neologisms (Arndt-Lappe, Beliaeva, and Martin, Chapter 6), and academic writing (Nasseri, Chapter 9), while the other studies take on advanced statistical methods to address variation in English grammar (Rautionaho and Meriläinen, Chapter 7; Ruohonen and Rudanko, Chapter 8). In the final chapter, Schweinberger critically assesses the replication crisis and proposes a range of ways to improve reproducibility and transparency through data-intensive workflows.

In “What Big Data Tells Us about American English Phonetics” (Chapter 2), Kretzschmar, Olsen, Olsen, and Ireland showcase the benefits of using big data in a phonetic analysis of Southern US English, utilizing point pattern analysis to systematically represent the wide array of possible acoustic realizations of individual phonemes and to highlight the most frequently utilized acoustic realizations of those phonemes. Compared to traditional sociophonetic research, Kretzschmar and colleagues find evidence for a much wider range of realization for vowels than is typically represented for Southern US English, and thus argue that big data complements existing perspectives on speech by providing a fuller picture of the variation that exists in natural speech.

In Chapter 3, “Do You Reckon? Creating and Testing a Corpus of Spoken Southern American English from the Digital Archive of Southern Speech (1970–1983),” Bridwell and Ireland discuss the process of preparing a collection of transcribed interviews recorded in the 1970s and 1980s for the Digital Archive of Southern Speech (DASS) to be uploaded into a Corpus Workbench server. This reuse of existing data results in a fully tagged, queryable text-based corpus that allows more careful analysis of the syntactic and lexical features of Southern American English with a dataset that was originally primarily intended for phonetic investigation. Bridwell and Ireland demonstrate the use of DASS with a case study focusing on the use of reckon, a well-known feature of Southern American English alternating with the epistemic verbs think and believe. The findings indicate that reckon is more grammaticalized than think or believe, but also that its use is decreasing and becoming more stigmatized and nonstandard.

Van Eyndhoven, Filgueira, and Gotthard explore the use of a new data-analysis facility, defoe, for investigating historical data quantitatively in Chapter 4, “‘Scots for the Masses’? Utilising a Novel Data-Analysis Facility to Statistically Explore Late Modern Scots in the Digitised Chapbooks Collection.” Making use of defoe, a text-mining tool set capable of parallel processing of tasks, the chapter provides a pilot study of a quantitative investigation of Scots lexis in a collection of digitized eighteenth- and nineteenth-century chapbooks. The results gleaned with the help of defoe and conditional inference tree analyses indicate that Scots features persist in chapbooks, especially within specific domestic topics. The chapter highlights the benefits of access to newly digitized datasets and data-mining tools in the analysis of historical data.

In Chapter 5, “Combining Collocation Measures and Distributional Semantics to Detect Idioms,” Schneider introduces a new methodology for detecting idioms, based on the view that idioms are collocations in which the lexical participants have low semantic similarity in the word-embedding space. The combination of frequentist approaches to collocation detection and distributional semantics and word embeddings sheds more light on the question of noncompositionality and improves idiom detection with regard to the three constructions investigated: verb-prepositional phrase combinations, light verbs, and compound nouns. The detection tests include the cosine metric, replaceability with synonyms, and linear combinations with collocation measures. The chapter also includes a case study on recent diachronic changes of compound nouns in spoken and written English, mirroring digitalization and the revolution of the internet.

Chapter 6, “Using Data-Intensive Methods for Unlocking Expressiveness in Word Formation: The Case of English Name Blending,” by Arndt-Lappe, Beliaeva, and Martin, addresses determinative and coordinative blends composed of personal names, with the aim of exploring novel quantitative methods in the study of blends as expressive word-formation devices. The chapter presents two case studies on the expressive nature of the two types of blends and the relation between the blends and different contexts and communicative constellations. On a theoretical level, the chapter challenges previous claims about the irregular nature of blending by showing that expressiveness is a systematic property of the word-formation process. On a methodological level, the chapter addresses the use of recent data analytic tools in addressing theoretical linguistic questions in morpho-pragmatics: while sentiment analysis and microblogging platforms provide tools for operationalizing ‘expressiveness’ of blends, the chapter also outlines some caveats in their use.

In Chapter 7, “Modal Verb Usage across Native and Non-native Englishes: A Variationist Analysis,” Rautionaho and Meriläinen examine the variation between will and be going to in native and learner varieties of English, with the aim of discussing whether advanced learners of English have adopted ongoing changes in core versus semi-modals, and whether their choice of the modal auxiliary is governed by similar structural variables as in native varieties. Methodologically, the study adopts a generalized linear mixed model tree analysis on two levels: (i) the alternation between will and be going to, with their different forms collapsed together, and (ii) the alternations between be going to versus gonna and will versus its contracted forms separately, in an effort to ensure that subtle grammatical conditioning is not masked by uneven distribution of variants. The results indicate that the English of foreign-language learners is shaped by similar processes of change that influence native language varieties, but also that some learner groups are more similar to native speakers than others.

Ruohonen and Rudanko present another multivariate analysis on contemporary English in Chapter 8, “Bayesian Multivariate Analysis of Complement Selection: Subject-Control Complements of the Verb Fear.” Here they focus on identifying semantic and syntactic factors affecting the alternation between to-infinitival and bare gerundial clauses in subject-control complements of the verb fear. Drawing data from recent American English, Ruohonen and Rudanko launch a Bayesian mixed-effects logistic regression analysis and confirm explanatory principles, such as the Complexity Principle as well as the Choice Principle, which have been found operative in the nonfinite subject-control complementation of various adjectives. The study also illustrates how Bayesian modeling may be more effective than generalized linear mixed models, in cases where the variants under scrutiny are highly imbalanced.

In Chapter 9, “Statistical Modelling of Syntactic Complexity of English Academic Texts: Syntactic Predictors of Rhetorical Sections,” Nasseri investigates the syntactic complexity of rhetorical sections in academic texts written by students with different kinds of English-language backgrounds. Subjecting nine complexity measures to ensemble learning using four machine learning predictive classifiers of Random Forest – K Nearest Neighbors, Deep Learning Artificial Neural Network, Gradient Boosting (as the stacked layer), and the Naive Bayes Method (as the meat learner) – Nasseri is able to tease apart syntactic predictors and their variability in the distinct rhetorical sections of MA dissertations. The results of the study show, for instance, increasing syntactic complexification when moving from the abstract toward the final sections of the paper. Nasseri’s findings have implications not only for research on academic writing as well as thesis writing itself, but also for automatic text classification and identification systems or models.

In Chapter 10, Schweinberger focuses on scientific rigor and discusses the Replication Crisis and its implications for corpus linguistics: “Implications of the Replication Crisis: Some Suggestions to Improve Reproducibility and Transparency in Data-Intensive Corpus Linguistics.” After highlighting some of the issues related to the Replication Crisis – lack of training on enhancing reproducibility, disorganized data management, analysis procedures that impede replication, and convoluted workflows compounded by limited availability of resources – Schweinberger provides information on how corpus linguists can adhere to best practices in enhancing reproducibility and transparency, with a case study exemplifying the processes needed to tackle the Replication Crisis. The chapter provides a wealth of resources, practices, and tools for researchers to adopt into their work.

In sum, the objective of the volume is to go beyond simply cataloging novel datasets, tools, and methods. Given the development of digitalization in general, this would be an unattainable objective. Rather, we hope that the volume identifies and discusses a range of topic areas in which novel ways of working could be used in the future, and therefore it would foster dialog of how researchers could benefit from digital tools, methods, and data not only in the empirical study of the English language but also in neighboring disciplines in the humanities.