Introduction

For several decades, the European Council has been at the center of theoretically driven and practically oriented studies of the European integration process and of what today is the European Union (EU). Scholars have highlighted its importance for EU crisis management and key decisions taken on issues such as EU enlargement (widening) and treaty revisions (deepening), the budget, foreign policy, and the EU’s role in the international system (see, for instance, Bulmer and Wessels Reference Bulmer and Wessels1987; Werts Reference Werts2008; Reference Werts2021; De Boissieu, Blanchet, Cloos et al. Reference De Boissieu, Blanchet, Cloos, Galloway, Keller-Noellet, Milton, Roger, Christoffersen and van Middelaar2015; Wessels Reference Wessels2015; van Middelaar and Puetter Reference Middelaar, Puetter, Hodson, Puetter, Saurugger and Peterson2021). However, despite the apparent desire and need for closer academic and policy-oriented engagement, the understanding of the European Council’s activities and functioning remains limited.

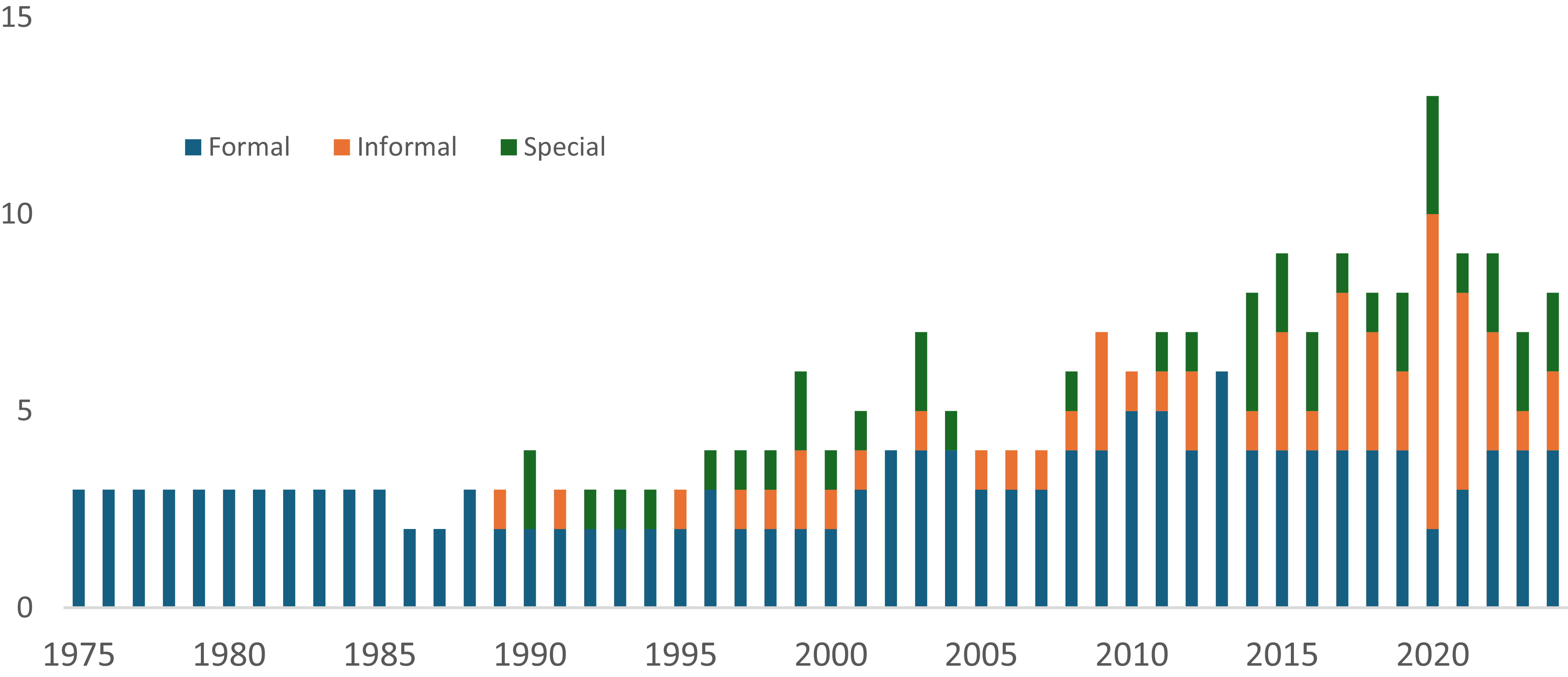

Established at the Paris Summit in December 1974, this institution met for the first time under the name ‘European Council’ in Dublin in March 1975. It was first mentioned in the primary law of the then European Community in the Single European Act of 1987. Gradually, it has become the key institution in what has been the EU since 1993. Mainly through its Conclusions, the European Council provides political impetus and sets the course for European integration. European Council summits have increased in frequency and often also in length compared with the early phase. While the European Council met three times per year during the first decade of its existence, the current treaty provisions suggest at least four meetings per year; in practice, however, the Heads tend to meet (much) more often. Since the onset of the Eurozone crisis in 2009, and throughout the EU’s recent ‘decade of crisis’ (Zeitlin, Nicoli, and Laffan Reference Zeitlin, Nicoli and Laffan2019), the European Council has seen a further rise in the number of meetings.

Importantly, this rise is driven by ‘informal’ and ‘special’ meetings. Apparently, there is a great need and willingness to meet more often and discuss matters of common concern. Figure 1 documents the number of European Council meetings per year. The items on the agenda cover a large range of policy areas (Cloos Reference Cloos2024); there hardly is any issue that the Heads do not discuss. Therefore, an analysis of this institution has become indispensable for understanding important political, economic, and social developments in (Western) Europe over the past five decades, as well as for assessing the current shape and future trajectory of the EU.

Figure 1. European Council meetings per year (1975 – 2024).

Source: own compilation.

Since the Treaty of Lisbon came into force in 2009, the European Council has brought together the Heads of State or Government of the EU member states, of which there are currently 27, as well as its own full-time President and the President of the European Commission. In a guest capacity, it includes the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Only the national Heads have the right to vote. The Treaty of Lisbon elevated the European Council’s status, listing it as an EU institution in Article 15 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), alongside the three ‘traditional’ Community bodies with legislative functions: the European Commission, the Council (of national ministers), and the European Parliament (Anghel and Drachenberg Reference Anghel and Drachenberg2019).

The Heads of State or Government have actively used, and continue to use, their institution to pursue national and European agendas (Schramm and Wessels Reference Schramm and Wessels2023). The treaty text, which stipulates that the European Council should provide the EU with the ‘necessary impetus for its development’ but itself ‘shall not exercise legislative functions’ (Art. 15(1) TEU), tends not to capture the full reality; this is because, regularly, the European Council does pursue ‘quasi-legislative activities’ (Bressanelli, Koop, Minetto et al. Reference Bressanelli, Koop, Minetto and Reh2025). Similarly, the requirement for consensus that the treaty usually foresees, along with the associated national right of veto for each member, suggests gridlock and political standstill. In practice, however, the European Council has repeatedly taken far-reaching and sometimes surprisingly ambitious decisions.

Therefore, any analysis of the European Council’s working patterns and effects must start with the Treaties’ legal requirements, but it must also include political practice. Of great importance are the constraints and incentives for the Heads regarding EU-level action, which include the dynamics coming from their respective domestic arenas and the role of other EU institutions. This article assesses key logics, patterns, and paradoxes in the work of the European Council against the backdrop of its 50th anniversary. Its aim is to contribute to a better understanding of this pivotal institution. Concretely, the article addresses three questions: What is the position and role of the European Council in the EU’s system of governance (‘The European Council in the EU’s multi-institutional and multi-level system’ section)? Why does the European Council regularly take decisions that strengthen supranational procedures, despite its intergovernmental composition (‘Paradoxes in the work and activities of the European Council’ section)? And how can and should we study, from an academic perspective, the European Council in view of data and access limitations (‘Weak points, deficits, challenges: the work in and on the European Council’ section)? By way of concluding, the article highlights weaknesses in the work of the European Council.

The European Council in the EU’s multi-institutional and multi-level system

In principle, the position and role of the European Council can be examined along two central dimensions of the EU’s governance system (Akbik and Dawson Reference Akbik and Dawson2024). The first horizontal dimension concerns the relationship between the European Council and other EU institutions. Depending on the composition, competences, and general objectives of these institutions, their relationship with the European Council is characterized by greater cooperation or conflict. The second, vertical dimension, concerning the supposed ‘presidentialization’ of the EU multi-level system (Johansson and Tallberg Reference Johansson and Tallberg2010), relates to the position of national Heads of State or Government as members of the European Council. They act in ‘double capacity’ (Wessels Reference Wessels2015: 8), as they perform roles simultaneously in the national and European spheres. These two dimensions will now be examined in closer detail.

Along the horizontal dimension the relationship between the European Council, on the one hand, and the European Commission, the Council of the EU (formerly ‘Council of Ministers’), and the European Parliament, respectively, on the other hand, are of particular interest. Compared with the vertical multi-level dimension (see below), this horizontal dimension of checks and balances and of the EU’s interinstitutional architecture has received much academic attention. Regarding the European Commission, several academic studies suggest that the Commission’s ‘agenda setting function’ is under threat because of the growing prominence of the European Council (Bocquillon and Dobbels Reference Bocquillon and Dobbels2014). Accordingly, the European Council, as the driving force and pacemaker of European integration, could be considered to weaken the Commission’s treaty-based monopoly to initiate legislation.

However, it can also be argued that the constructive involvement of the Commission President in the work of the European Council, of which she is a member, is advantageous for the Commission and the EU’s overall institutional architecture. For instance, the Commission President can use her involvement to help prepare and negotiate issues in the European Council, from whose implementation her institution later benefits. The relationship between the European Council and the Commission remains of great importance for the study of EU interinstitutional relations, as there has been a lively academic debate over the past decade about the alleged institutional ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2014; Dehousse Reference Dehousse2016; Kassim Reference Kassim2023).

At first glance, the relationship between the European Council and the Council of the EU is less complex and conflictual. After all, both institutions comprise representatives from the member states, who predominantly follow intergovernmental decision-making patterns. Moreover, the establishment of the European Council in the early 1970s was driven by the desire of national leaders to overcome political impasse in the occasionally ineffective Council of Ministers (Mourlon-Druol Reference Mourlon-Druol2016). Ever since then, the Heads of State or Government have prioritized either deciding controversial issues themselves or tasking their ‘subordinate’ ministers with the legislative follow-up design of their decisions (Kroll Reference Kroll, Delreux and Adriaensen2017).

However, on closer inspection this relationship, too, is more dynamic. The reverse view suggests that members of the European Council might transfer issues to the ministers not just for implementation but for actual decision-making. The reason is that decision-making inside the European Council is subject to consensus (de facto, unanimity), while ministers can usually take decisions based on a qualified majority. Following this perspective, some European Council members might want to circumvent potential gridlock in their own institution. An example of this dynamic could be seen in late 2020 in the discussions about the new rule of law conditionality clause in the context of the ‘Next Generation EU’ Covid-19 recovery plan (Coman Reference Coman2022: 208–211): As it was clear that two members – the Hungarian and Polish prime ministers – would oppose any decision on that clause inside the European Council, several Heads were committed to leave this topic to the ministers who were able, and prepared, to adopt the clause via a qualified majority.

In turn, the relationship between the European Council and the European Parliament entails considerable potential for tension and conflict. With the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Parliament became an equal co-legislator and a central decision-making body in most policy areas and procedures. One reason for the tension is that the two institutions represent different constituencies and are therefore legitimized via different channels (Dinan Reference Dinan2018): While the European Council is composed of the national Heads of State or Government whose legitimacy derives from domestic elections, the European Parliament is the only directly elected EU institution and therefore feels accountable to the citizens of the EU.

To be sure, there is little direct interaction between these two institutions, let alone any form of formal dependency: The European Council is not politically accountable to any institution, which means that the European Parliament has no power to sanction it (Akbik and Dawson Reference Akbik and Dawson2024). This is one reason why the European Parliament, in its resolutions, repeatedly criticizes the European Council’s political ‘overreach’ and its ‘quasi-legislative activities’ (Bressanelli, Koop, Minetto et al. Reference Bressanelli, Koop, Minetto and Reh2025). However, a tense and direct relationship emerges in areas where important EU decisions require the consent of both institutions. This is notably the case for the election of the Commission President (Spitzenkandidat) and decisions on the expenditure side of the EU budget.

In terms of the vertical dimension, it is evident that the Heads of State or Government have repeatedly used the European Council as a platform to promote their national agendas. While in its early years the European Council dealt almost exclusively with issues of European foreign and economic policy, today the Heads tend to discuss all issues that also shape the political debates in the member states. For the European Council to be effective, its composition is of utmost importance. Unlike the EU’s supranational institutions – the European Parliament and the Commission – whose entire composition changes following the day of the European elections, the European Council has a ‘dynamic’ electoral cycle: Its composition alters every time there is a change in the government or presidency of a member state.

Because of the requirement for consensus, formally all members are equal. In practice, of course, those Heads from powerful member states – the largest ones with most economic resources – tend to have bigger influence inside the European Council (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2008). In addition, the reputation and experience of a Head matters. Some research suggests that the party-political and ideological composition of the European Council has had little impact on its overall performance (Tallberg and Johansson Reference Tallberg and Magnus Johansson2008). However, this is a factor that so far has not been subject to closer and systematic analysis (although see Drachenberg Reference Drachenberg2022).

Figure 2 displays the party-political composition of the European Council for the period from 2009 to 2019, compared with the size of the main centrist political groups inside the European Parliament. The figure documents variation not only in the party-political composition of the European Council over time but also in the share of the centrist groups that tends to be bigger in the European Council than in Parliament. This is because the Heads of State or Government (still) tend to come from center-right, center-left, or liberal political parties. Nevertheless, also inside the European Council the number of ‘non-centrist’ members has increased because of the electoral gains of nationalist-sovereigntist political forces (Servent and Zaun Reference Servent and Zaun2024).

Figure 2. Party-political composition of the European Council over time.

Source: Drachenberg and Nielsen (Reference Drachenberg and Nielsen2024: 13).

Another related factor concerns the room for maneuver of a Head in view of their domestic situation. While the composition and (in)stability of an individual national government rarely has had a direct impact on the overall performance of the European Council, the empirical record suggests that the parliamentary majority for individual Heads has become less solid over time. In recent years, this also included unstable or entirely missing majorities for the governments in the two largest EU member states, Germany and France. Overall, the ‘domestic situation’ of its members represents an important but hitherto understudied aspect in the functioning of the European Council, especially in a longer-term and comparative perspective (Wessels et al. Reference Wessels2013).

Finally, it is interesting to analyze how members of the European Council communicate their deliberations and decisions, which are usually recorded in the form of ‘Conclusions’, to their national constituencies. Sometimes it seems as if the members were not talking about the same decisions, because each one stresses national benefits and wants to report successes ‘at home’. Regarding communication and accountability, there is a large variance across member states (Winzen Reference Winzen2012; Reference Winzen2022): While some parliaments have advanced provisions and tools to scrutinize their national leaders, others have not. Accordingly, some Heads give comprehensive reports, whereas others provide less information. Scholars have started examining such communication patterns in greater detail, for instance, by looking at the national press conferences that every Head usually gives following a European Council summit (Hunter Reference Hunter2025).

Paradoxes in the work and activities of the European Council

The European Council is not free of paradoxes. A paradox is a situation in which the original or formal intention does not have the expected effect over time or in political practice. One such early paradox was that, at the time of its creation, the European Council was seen by the smaller member states – the three Benelux countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) – as a threat of the ‘intergovernmentalization’ of the Communities and a gateway to dominance by the larger members, especially France and Germany (Mourlon-Druol Reference Mourlon-Druol2016). However, in later years smaller member states – including the Central and Eastern European countries that gained their national sovereignty in the 1990s and joined the EU during the 2000s – tend to see the European Council as a safeguard against national marginalization in view of ongoing EU integration.

Another paradox in the work of the European Council is that, despite considerable formal and informal centrifugal forces, this institution has continuously proven able to take decisions, sometimes far-reaching ones. After all, decisions in the European Council are subject to the consensus principle, which allows for a multitude of national vetoes. Furthermore, the Heads of State or Government are generally highly self-confident policymakers with strong incentives to pursue strictly defined national priorities to raise their profile with their own political party or electorate. Nevertheless, despite – or perhaps because of – considerable differences in national preferences and scope for action, the European Council usually finds common solutions when shaping policies and the EU polity.

Various theoretical approaches have been mobilized and applied to make sense of this paradox. On the one hand, ‘rationalist’ perspectives point to comprehensive bargaining rounds and the formation of complex package deals that enable each member of the European Council to prioritize a key national interest (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1998). In the event of difficult negotiations, individual members or coalitions of members with the necessary resources can demonstrate leadership by proposing solutions, taking on significant costs, or presenting recalcitrant members with a fait accompli (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2008). As with European integration in general, the Franco-German partnership, typically working closely with the President of the European Council (formerly rotating, but full-time since 2009), has proven particularly influential within the European Council (Schramm and Krotz Reference Schramm and Krotz2024).

‘Constructivist’ perspectives, on the other hand, highlight the importance of deliberation and social norms in explaining the consensus paradox (Puetter Reference Puetter2014). Shared views, institutional membership, and the recognition that certain political problems can only be addressed and solved collectively within the European Council are said to leave Heads of State or Government deviating from strictly defined national positions. This realization might further be reinforced by institutionalized practices and a high degree of path dependency (Pierson Reference Pierson2000). The notion of a strong ‘problem-solving instinct’ on the part of the members of the European Council – stemming from the desire to achieve national objectives and the appreciation of this institution as a ‘club of leaders’ – demonstrates that rationalist and constructivist perspectives can complement each other (Wessels Reference Wessels2015: 19).

A third and perhaps most interesting and consequential paradox concerns the impact of the work of the European Council on the EU polity and the trajectory of European integration. Because of its composition and decision-making rules, the European Council fundamentally follows an intergovernmental logic (Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2017). No member wants or can be outvoted, except in cases involving decisions on the selection of top personnel or the convening of intergovernmental conferences for treaty revision. Alongside lengthy and complex negotiations, this constellation can result in formerly ambitious proposals by the European Commission being ‘watered down’ and national-specific arrangements being introduced, including transitional or permanent opt-outs for individual member states. Consequently, the European Council could be perceived as a highly deficient institution and integration brake.

Viewed over a longer period, however, the Heads of State or Government have repeatedly expanded the range of policy issues that member states deal with together and advanced the EU’s competences. In addition to the major treaty reforms of the 1990s and 2000s, this impetus includes measures to address the most immediate crisis pressures. Why and how has this been the case? A few recent examples illustrate this integration paradox. For instance, while defining the general principles, guidelines and ‘red lines’ for the EU’s withdrawal negotiations with the UK following the Brexit referendum, the European Council entrusted the European Commission with the daily and detailed talks with the UK government (Laffan and Telle Reference Laffan and Telle2023). Similarly, while agreeing to establish a ‘Recovery and Resilience Facility’ in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the European Council subsequently tasked the Commission with raising the joint debt, assessing national recovery and resilience plans, and distributing the €750bn to the member states (Schramm, Krotz, and De Witte Reference Schramm, Krotz and De Witte2022).

It seems that this paradox – the intergovernmental composition of the European Council regularly prompting more and deeper supranational Union procedures – is rooted in two main aspects. One aspect concerns the academic literature taking too narrow of a theoretical focus. The European Council is widely described as the EU’s ultimate and ‘supreme decision-maker’ (van Middelaar and Puetter Reference Middelaar, Puetter, Hodson, Puetter, Saurugger and Peterson2021), which comes into play when stakes are particularly high and politically controversial. Following an intergovernmentalist playbook, national leaders are said to deliberate in dramatic negotiations behind closed doors. Not surprisingly, much of the literature on the European Council focuses on ‘summits’, that is, the one- or two-day setting in which leaders ultimately take their decisions.

However, as the classical policy cycle reminds us (for instance, Jann and Wegrich Reference Jann, Wegrich, Fischer, Miller and Sidney2007), taking and realizing decisions also requires a preparation and implementation stage. Here, institutional actors and interests other than the ones represented by the European Council come in. The ‘new institutionalist leadership’ approach (Smeets and Beach Reference Smeets and Beach2020; Reference Smeets and Beach2023) deploys the policy cycle to put the role of the European Council into a broader perspective, but it has mostly done so by focusing on supposed crises. Future research should draw more extensively and explicitly from the public policy literature to assess the preparation and follow-up of pivotal European Council decisions. Moving beyond crises, or moments considered as such, would help ‘normalize’ the study of the European Council beyond emergencies.

A second, related aspect of the integration paradox concerns the practical lack of capacity on the part of the European Council. To start with, this institution itself has a (very) small administration. Its President’s cabinet relies on the support of the larger administrations of other institutions, particularly the General Secretariats of the Commission and the Council of the EU (Dinan Reference Dinan2013). Moreover, the European Council is lacking enforcement mechanisms. Since there is no central authority available, it depends on the goodwill of its members and national administrations to have its decisions fully and timely implemented.

In the preparation and follow-up of its decisions, other EU institutions are often better prepared and placed than the European Council thanks to their respective legal competencies, larger administrative infrastructures, and/or more efficient internal decision-making processes. The result is that the European Council often depends on or actively entrusts, following a basic principal–agent perspective (Pollack Reference Pollack2003), other institutions with preparing, realizing, and monitoring its decisions. This implies, over time, a broadening of issues that the EU is dealing with and an increase in the opportunities for other institutional actors to get involved.

In sum, research suggests that national leaders often – though not always – view the EU level as the appropriate forum for making decisions and finding solutions to issues of common concern. Other than what is suggested by the ‘new intergovernmentalism’ (Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015), it seems that the Heads of State or Government are not opposed in principle to the strengthening of supranational actors and procedures. Such an impression may arise if only the European Council’s current negotiations and agreements (or the lack thereof) were considered in isolation. In the medium to long term; however, decisions by the European Council have often led to ‘more Europe’ – not necessarily at the expense of national actors and intergovernmental procedures but in a way that required the close(r) coordination of different institutional actors located at different levels of governance.

Weak points, deficits, challenges: The work in and on the European Council

There are a number of challenges that are associated with working on the European Council. Understanding and addressing these issues contributes to a better, more comprehensive understanding of this key EU institution. Firstly, the article highlights two issues regarding the European Council that often go unnoticed or tend to be underestimated. The section concludes by outlining challenges that arise for the academic study of the European Council.

A common feature of many EU institutions, particularly the European Council, is the reluctance of its members to admit disagreement and failure. It is generally difficult for academic observers and the interested public to understand where the lines of conflict lie within the European Council and why it has (not) made a decision in a particular situation. The Conclusions are the most visible outcome of European Council meetings and, as such, a popular source of academic research (see for instance Ullrichova Reference Ullrichova2023; Ghincea and Pleșca Reference Ghincea and Pleșca2025). However, they usually provide an incomplete or even distorted picture, as they merely summarize the discussion points and list the achieved results in a laudatory tone (Cloos Reference Cloos2022). This is because the adoption of the Conclusions is also subject to consensus.

To identify controversies, it is necessary to read the Conclusions carefully and have a good understanding of the respective temporal and political contexts. Individual formulations may indicate that no agreement has been reached. Contrary to what might be assumed at first glance, formulations stating that the members merely ‘discussed’ or ‘debated’ a certain point actually suggest that no agreement was reached. If the European Council does not adopt Conclusions as a collective, this usually indicates major and, for the moment, irreconcilable differences of opinion within the institution because at least one member has blocked their adoption, or that the European Council as a whole has decided that further consultations are necessary. In such cases, the President of the European Council often presents the Conclusions in their own name.

One example is the ‘Conclusions of the President of the European Council’ of 23 April 2020, in which President Charles Michel reported on the ongoing but still controversial and inconclusive deliberations on an EU financial ‘recovery plan’ (Council of the EU 2020). Regarding the EU’s support for Ukraine in its defense against the Russian war of aggression, in March 2025, 26 of the 27 Heads of State or Government published a separate declaration because the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, had prevented this statement from being included in the general Conclusions (European Council 2025). An extremely rare example of a summit that could be considered a complete failure was the European Council of Athens in December 1983: Following this summit, the then-European Council President, Andreas Papandreou, explicitly informed the press that no Conclusions had been agreed upon (Bulletin 1983).

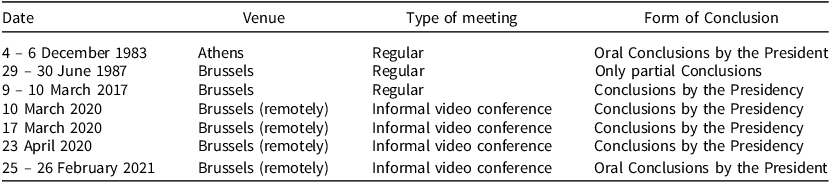

From an academic perspective, there is thus the need to put the Conclusions into an informed perspective. One way of doing this is to compare the wording of the Conclusions with the European Council’s agenda, which is usually published some days before the summit. Another way is to contrast the wording of the Conclusions with what the Heads communicate at their national press conferences. Of particular academic interest are those summits for which no collective Conclusions were adopted. While this regularly happens following an informal or special European Council, it is extremely rare that a regular meeting finishes without the adoption of Conclusions by all members. Table 1 presents some of the European Council meetings for which no Conclusions were published or for which only the President issued Conclusions.

Table 1. European Council meetings without formal Conclusions

Source: Own compilation.

Deficits also become evident in the European Council’s realization of its own deadlines and objectives. The latter often fall short of the expectations raised by the European Council itself through earlier announcements. This applies, for instance, to its role as constitutional architect for enlargement (widening) in combination with institutional and policy reform (deepening). Initiatives, ambitions, and, in some cases, decisions on internal reforms that were intended to improve the functioning of the European Communities, and later the EU, either failed to materialize or were only partially implemented (Kelemen, Menon, and Slapin Reference Kelemen, Menon and Slapin2014). This included, for instance, the intended reduction in the size of the College of Commissioners and the larger expansion of majority decisions in the Council of the EU.

The EU’s finances and, in particular, the multiannual financial framework provide another example of how the European Council fails to meet its own declared objectives. Although the EU treaties assign responsibility for key decisions to the Council of the EU, in practice it is the European Council who acts as the ‘master of the budget’ (Becker Reference Becker2025). It might be considered surprising and unsatisfactory that negotiations and decisions in the European Council on the multiannual financial framework are so time-consuming given that most national preferences and lines of conflict are fairly clear and have remained constant over time (Citi Reference Citi2015). The sums involved in these negotiations are often relatively small, especially when compared with the much larger scope of national budgets. Therefore, the time and political energy that the Heads spend on this subject is remarkable. It usually takes two years, including several European Council summits, considerable work by the European Commission, and the preparation of ‘negotiating boxes’ by up to four rotating Presidencies of the Council of the EU, for the Heads to eventually agree on the next multiannual financial framework (Becker Reference Becker2025).

Moreover, ever since the first agreement on the ‘British rebate’ in 1984, the European Council has been unwilling to break free from the ‘juste retour’ logic (Citi Reference Citi2015), whereby each member state would like to receive roughly the same amount from the EU budget as it has paid in. The most significant problem is that the European Council has not succeeded, despite repeated statements to the contrary, in providing the EU with larger and truly independent ‘own resources’. Recently, the decisions taken by the European Council in 2020 and 2021 regarding new own resources as part of the Recovery and Resilience Facility barely suffice to repay the loans taken out. Overall, it becomes obvious that the European Council regularly formulates ambitious projects – often based on expert reports that it had previously commissioned – but then falls well short of these ambitions in terms of decision-making and realization.

Finally, first-hand academic analysis of the European Council is challenging. More than with other EU actors, the data basis for this institution is extremely limited, particularly in the form of primary data (Wessels and Dieke Reference Wessels and Dieke2018). One access point is the memoirs of former European Council members. Some people who in the past were closely involved in the work of this institution or who analyzed it over decades have shared their insights in the form of books (Werts Reference Werts2021), chapters (van Middelaar and Puetter Reference Middelaar, Puetter, Hodson, Puetter, Saurugger and Peterson2021), or policy briefs (Cloos Reference Cloos2022; Reference Cloos2024). A small number of researchers have conducted interviews with former or current European Council members (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2008; Johannsson and Tallberg Reference Johansson and Tallberg2010). However, considering how biased memoirs can be and how difficult it is to conduct expert interviews on a large scale, other tools and approaches are necessary.

On a more positive note, there have been some encouraging developments: The scope and quality of media coverage in the run-up and during European Council summits has increased significantly. International media outlets such as the Financial Times, The Economist, Politico, or Euractiv provide detailed coverage and at times background reports of these summits. National media, too, tend to cover European Council meetings to a greater extent than in the past. Although laborious and time-consuming, the triangulation of different sources – the wording of the Conclusions, media coverage, and the national communication of individual Heads – can provide a balanced and more in-depth understanding of the European Council summits, the bargaining behind closed doors, and the following negotiation results.

Conclusions and outlook

Over the course of its 50-year existence, the European Council has played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of European integration. Its history is closely linked to the development of the European Communities and the EU. Compared with its initial phase, the number of European Council meetings has increased significantly, particularly over the past two decades. In recent years, the Heads of State or Government have often met eight or nine times, and as many as 13 times in the ‘Covid year’ of 2020, despite the treaty suggesting only four regular meetings per year. Clearly, there is a great need to discuss political issues of common concern, especially in times of crisis, and to establish a EU capacity to act. These developments have been accompanied by a steady expansion of topics on the European Council’s agenda. Sometimes, the European Council reacted to broader international developments. At other times, its own members moved topics from the national to the EU level.

Recently, it has become apparent that achieving consensus among the 27 national Heads of State or Government is difficult. This is particularly evident in the repeated vetoes exercised by the Hungarian Prime Minister Orbán on decisions regarding financial and military support for Ukraine in its defensive struggle against Russia. A key question for the coming years will be the extent to which the majority of Heads is willing and able to employ flexible instruments to circumvent the obstruction by individual members. In the past, this was occasionally done via treaties outside of EU law, for instance, during the Eurozone crisis when the then-British Prime Minister, David Cameron, threatened to veto the adoption of the Fiscal Compact and of the European Stability Mechanism (Smeets, Jaschke, and Beach Reference Smeets, Jaschke and Beach2019).

Today, issue linkages, which in the past had often been a fruitful way for the European Council to enable overall consensus, prove to be counterproductive, as individual members use them exclusively to extract national concessions rather than for contributing to EU-level package deals (Müller and Slominski Reference Müller and Slominski2025). As the institution’s history has shown, the European Council, which is intergovernmental in its composition and decision-making mode, risks becoming deficient if the intergovernmental logic – understood as the insistence on purely defined national preferences and zero–sum game calculations – becomes too strong. Therefore, a key question for the functioning and impact of the European Council is whether supranational-oriented approaches will also become visible in the future. Alternatively, some members might be increasingly prepared to form ‘coalitions of the willing’ to sideline recalcitrant members.

Financial support

No specific funding must be reported by the author.

Competing interests

The author does not report any conflicts of interest.