1. Introduction

South Asia, a region home to over one fifth of the global population, faces an increasingly complex challenge: achieving sustained economic growth while safeguarding environmental sustainability. With rapidly growing populations, accelerating urbanization and expanding industrialization, the region’s largest economies—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—are under mounting pressure to balance development imperatives with ecological preservation. Two external financial flows—migrant remittances and external debt—have become particularly significant in this context. Remittances, a relatively stable and counter cyclical source of foreign capital and external debt, a key financing mechanism for infrastructure and fiscal gaps, both play central roles in shaping macroeconomic trajectories. However, their environmental consequences remain less understood, particularly when examined in tandem.

In 2019, South Asia accounted for nearly one fifth of global remittance inflows, with remittances representing more than 7% of GDP in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Meanwhile, external debt liabilities in the region have risen sharply in recent years, accompanied by escalating debt-service burdens (World Bank, 2021, 2022; UNESCAP, 2023; IMF, 2024). While these financial flows are critical for economic resilience, especially in times of global shocks, their implications for carbon emissions and broader environmental quality have sparked growing scholarly and policy concern (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Ozturk and Majeed2022; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ajide and Elum2022; Beşe and Friday, Reference Beşe and Friday2022).

Remittances have long been associated with improvements in household welfare, education, health and small-scale entrepreneurship (Ratha, Reference Ratha2005; Adams and Cuecuecha, Reference Adams and Cuecuecha2013; Ratha et al., Reference Ratha, Plaza and Shaw2020). Within the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) framework, they are conceptualized as informal insurance that allows households to smooth consumption and invest in risk mitigation (Stark and Bloom, Reference Stark and Bloom1985; Taylor, Reference Taylor1999). However, the environmental implications of remittances are mixed. On the one hand, remittance-receiving households have been observed to invest in cleaner technologies such as solar energy and fuel-efficient stoves (Yang and Choi, Reference Yang and Choi2007; Bettin and Zazzaro, Reference Bettin and Zazzaro2018). On the other, higher disposable incomes often drive increased consumption of energy-intensive goods—vehicles, air conditioning and electronics—thereby raising household carbon footprints (Meyer and Shera, Reference Meyer and Shera2017). In South Asia, where weak environmental governance and regulatory enforcement persist, the adverse environmental effects of such consumption patterns may be particularly pronounced (Islam, Reference Islam2022; Jafri et al., Reference Jafri, Liu and Bashir2022; Dash et al., Reference Dash, Sen and Roy2024).

External debt also presents an environmental double-edged sword. While borrowing can fund vital infrastructure and public services, the quality and purpose of debt-financed projects determine their ecological impact. Productive debt can support sustainable infrastructure and green energy, but in many developing economies—including those in South Asia—debt is often used to finance fossil fuel projects or environmentally harmful industries to meet short-term growth targets and foreign exchange needs (Dabla-Norris et al., Reference Dabla-Norris, Brumby, Kyobe, Mills and Papageorgiou2012; Katircioğlu and Celebi, Reference Katircioğlu and Celebi2018; Carrera and de la Vega, Reference Carrera and de la Vega2024). Furthermore, the burden of external debt servicing can significantly constrain fiscal space, forcing governments to reallocate resources away from environmental protection, renewable energy or climate adaptation programmes (Hansen, Reference Hansen1989; Torras, Reference Torras2003; Freeland and Buckley, Reference Freeland and Buckley2010). In such cases, the opportunity cost of meeting external obligations may manifest as environmental degradation.

An emerging body of literature has begun to explore these dynamics in developing regions. For example, Sadiq et al. (Reference Sadiq, Saleem, Rjoub and Usman2022) report that external debt and energy intensity significantly increase environmental degradation in BRICS countries. Awad et al. (Reference Awad, Melesse and Bekun2024) demonstrate that remittances can reduce environmental harm in sub-Saharan Africa when mediated by strong institutional quality. In Turkey and China, Beşe et al. (Reference Beşe, Friday and Çoban2021) and Beşe and Friday (Reference Beşe and Friday2022) find non-linear relationships between debt and emissions, underscoring the importance of country-specific governance and financial contexts. Within South Asia, studies by Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Cai and Ahmad2023) and Dash et al. (Reference Dash, Sen and Roy2024) suggest that remittances can simultaneously facilitate clean energy transitions and exacerbate environmental harm, depending on financial and regulatory environments.

Despite these insights, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding the joint and interactive environmental impacts of remittances and external debt, especially when considering the role of debt servicing as a potential moderating variable. This omission is particularly salient for South Asia, where countries are simultaneously among the world’s largest recipients of remittances and face chronic challenges in managing rising debt obligations. These economies also display wide variation in environmental performance, fiscal governance and energy structures, warranting a comparative regional analysis.

To address this research gap, this study investigates the combined and interactive effects of remittances and external debt on environmental quality in South Asia, with a specific focus on how external debt servicing moderates these relationships. We focus on four of the region’s major economies—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—using country-level panel data and a multi-stage econometric approach. The study is organized around three primary objectives: (1) to assess the direct impacts of remittances and external debt on environmental degradation, measured by CO2 emissions; (2) to examine the moderating role of external debt servicing in these relationships and (3) to derive policy-relevant insights for fostering financial and environmental sustainability.

Methodologically, we employ a robust empirical strategy, beginning with pooled ordinary least squares (OLS), followed by Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to address cross-sectional dependence and autocorrelation (Driscoll and Kraay, Reference Driscoll and Kraay1998) and finally feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) to correct for heteroscedasticity and ensure the robustness of the results (Biørn, Reference Biørn2004). By introducing interaction terms between remittances, external debt and debt servicing, this study makes an original contribution to the finance–environment nexus literature, providing empirical evidence that is both regionally grounded and globally relevant.

Ultimately, the findings offer valuable implications for policy. They underscore the need to align remittance use with green investment strategies, promote sustainable borrowing through instruments like green bonds and integrate environmental considerations into debt management and fiscal policy frameworks. These insights are not only timely for South Asia, which is facing escalating climate risks and resource pressures, but also applicable to other developing regions grappling with similar financial and environmental challenges.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature and identifies the research gap. Section 3 outlines the data sources, model specification and estimation techniques. Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical findings, while Section 5 concludes with key policy implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical review

To analyse the interaction between financial flows and environmental outcomes in South Asia, this study integrates three complementary theoretical frameworks: the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM), debt overhang theory and the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis.

The NELM framework (Stark and Bloom, Reference Stark and Bloom1985; Taylor, Reference Taylor1999) highlights remittances as a vital mechanism for risk-sharing and income smoothing. Migrant remittances help households manage shocks and finance investments in productivity enhancing and potentially cleaner technologies. However, by easing liquidity constraints, remittances can also fuel increased consumption, including of carbon-intensive goods and services. Thus, their environmental effects are potentially dual—promoting sustainability through green investment, but contributing to pollution through higher resource use.

Debt overhang and crowding out theories (Krugman, Reference Krugman1988) suggest that high external debt and associated servicing obligations divert government resources from productive and public investment. This reallocation may suppress spending on environmental protection, regulatory enforcement or sustainable infrastructure. While external borrowing can spur growth by financing large-scale projects, the environmental trade-offs depend on how those funds are allocated and how burdensome repayment obligations become.

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) (World Bank, 1992; Grossman and Krueger, Reference Grossman and Krueger1995) provides a framework to understand how economic development shapes environmental degradation. The EKC posits that emissions initially rise with income but decline once a threshold is crossed, as societies can afford cleaner technologies and stricter environmental policies. Remittances can help accelerate this transition, but debt servicing may delay it by constraining the fiscal capacity needed for green investments.

These theories are brought together in a conceptual framework (see Figure 1) that explains how remittances, external debt and debt servicing interact to influence CO2 emissions. Remittances may reduce emissions when used for sustainable investments, but may increase them through higher consumption. External debt may raise emissions via development spending on carbon-intensive infrastructure. Yet, high debt servicing could moderate this effect by limiting future borrowing. Similarly, the interaction between remittances and debt servicing can shape their combined environmental impact: heavy debt obligations may restrict the green uses of remittances, shifting household spending away from sustainable practices.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

The framework also incorporates broader macroeconomic conditions such as GDP growth and urbanization, consistent with EKC logic. These factors influence a country’s position along the development–environment trade-off and condition the effectiveness of financial inflows in promoting sustainability. For instance, urban expansion can amplify emissions unless accompanied by green planning and investment.

In sum, this integrated theoretical framework supports the hypothesis that financial flows—particularly when combined with fiscal constraints and development pressures—have complex and conditional effects on environmental sustainability in South Asia. By modelling interaction effects and linking household-level remittance behaviour with public finance constraints, the study provides a nuanced foundation for the empirical analysis and subsequent policy recommendations.

2.2. Empirical review

2.2.1. External debt, debt servicing and environmental sustainability

The relationship between external debt and environmental quality has attracted increasing scholarly attention, particularly within developing and heavily indebted countries. While early literature focused on normative concerns, recent empirical studies provide a more nuanced yet inconclusive picture of how debt dynamics influence environmental outcomes. A central argument in this debate is that external borrowing, especially when tied to structural adjustment programmes, has historically led to environmental degradation. Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Markandya and Barbier1995) contend that policy conditionalities imposed by international financial institutions—such as fiscal austerity and export-led growth—have pressured resource-dependent economies to exploit their natural capital in order to meet debt obligations, often at the expense of ecological sustainability.

This view finds empirical support in the work of Akam et al. (Reference Akam, Efobi and Osabohien2022), who employed the augmented mean group estimator to examine South Africa, Algeria, Nigeria and Egypt. They find that economic growth and energy consumption are key drivers of environmental degradation, with external debt worsening ecological outcomes in South Africa and Algeria. These results suggest that high debt burdens can undermine state capacity for environmental governance by diverting fiscal resources away from sustainability focused public investments. However, the extent to which this negative association holds across different contexts remains contested. In a study of Turkey spanning 1960–2013, Katircioğlu and Celebi (Reference Katircioğlu and Celebi2018) confirmed the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis—whereby environmental degradation first rises and then falls with income—but found no significant long-term impact of external debt on environmental quality. This implies that debt is not inherently detrimental to the environment; its effects are conditional on how funds are allocated and the institutional context in which they are managed.

Further complicating this narrative are findings from China and Turkey. Beşe et al. (Reference Beşe, Friday and Çoban2021) report that external debt contributes to CO2 emissions in China, where post-2008 debt-financed growth disproportionately supported emissions-intensive industries. In contrast, Beşe and Friday (Reference Beşe and Friday2022) identify a non-linear relationship in Turkey, where external debt increases pollution up to a threshold, beyond which its marginal environmental impact declines. These studies highlight that the debt-environment link is not necessarily linear and may depend on debt levels, sectoral investment patterns and institutional absorptive capacity.

To address methodological limitations in cross-country analysis, Carrera and de la Vega (Reference Carrera and de la Vega2024) introduce international liquidity shocks as instruments to tackle endogeneity in assessing the debt–environment relationship. Their results, based on 78 developing and emerging economies, show that a 1% increase in debt-to-GDP correlates with a 0.5% rise in greenhouse gas emissions. This finding reinforces concerns that governments under fiscal stress may deprioritize environmental regulation in favour of short-term macroeconomic stability.

Some researchers argue that external debt, if properly channelled, can support environmental improvement. Sadiq et al. (Reference Sadiq, Saleem, Rjoub and Usman2022) show that in BRICS economies, external debt contributes positively to environmental quality when paired with strategic investments in cleaner energy, such as nuclear power. However, they also note that financial globalization—unlike targeted debt—tends to exacerbate environmental degradation, underscoring the importance of debt composition and oversight.

Similarly, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Zhang and Yang2022) opined that Turkey, like many other countries, is grappling with escalating environmental and ecological issues, largely driven by fossil fuel dependence and shifting consumption patterns. In response, there is a growing emphasis on promoting renewable energy and sustainable economic growth. This study examines how external debt, energy consumption and real income have influenced Turkey’s ecological footprint from 1985 to 2017. Employing the Bootstrap ARDL approach and Granger causality analysis, the findings reveal that external debt significantly affects environmental quality in both the short and long terms. Meanwhile, energy use and real income are associated with environmental degradation across both time horizons. The causality analysis indicates a one-way causal relationship from external debt, economic growth and energy consumption to environmental quality. Based on these outcomes, the study recommends that Turkey should pursue debt consolidation strategies—such as tax reforms and expenditure reductions—to create fiscal space for long-term environmental sustainability initiatives.

Conceptual perspectives further enrich the debate. The notion of ‘ecological debt’, advanced by Torras (Reference Torras2003) based on Martinez-Alier’s work, suggests that high-income nations owe an environmental liability to the Global South due to historical ecological exploitation. While largely theoretical, this idea has influenced calls for mechanisms such as debt-for-nature swaps and green finance initiatives. On a more optimistic note, Freeland and Buckley (Reference Freeland and Buckley2010) argue that external borrowing, if prudently managed, can be leveraged for environmental gains by financing low-emission technologies and sustainable infrastructure. This dual perspective—that debt can be both an environmental risk and a financing tool for sustainability—reflects the importance of governance, accountability and policy design.

An important yet underexplored dimension in this literature is the role of debt servicing. While much of the existing research focuses on total debt stock, servicing obligations may impose a more immediate constraint on environmental spending. Drawing from debt overhang theory (Krugman, Reference Krugman1988; Sachs, Reference Sachs and Boughton1989), several studies argue that high debt-servicing burdens crowd out public investment in sectors like health, education and environmental protection. Dabla-Norris et al. (Reference Dabla-Norris, Brumby, Kyobe, Mills and Papageorgiou2012) provide evidence that debt servicing limits investment in renewable energy, pollution control and sustainable agriculture. Empirical research from Latin America (Arezki and Ramey, Reference Arezki and Ramey2012) and sub-Saharan Africa (Coulibaly, Reference Coulibaly2025) shows that spikes in debt servicing are associated with reduced conservation spending and increased reliance on biomass fuels, worsening both air quality and deforestation.

Cohen (Reference Cohen2022) also highlights that debt-financed infrastructure projects in South Asia, such as hydropower and highways, often proceed without adequate environmental assessments, leading to ecosystem disruption. Similarly, Pattillo et al. (Reference Pattillo, Poirson and Ricci2002, Reference Pattillo, Poirson and Ricci2004) argue that once debt-service ratios exceed 20% of exports, countries experience slower improvements in environmental indicators like air quality and water access. More recently, Fosu et al. (Reference Fosu, Eshun and Ankrah Twumasi2025), using dynamic panel data techniques, find that a one-percentage-point rise in the debt-service-to-exports ratio results in a 0.5% increase in CO2 emissions within 2 years. These findings point to the fiscal squeeze effect of debt servicing, which can delay or suppress the implementation of environmental regulations and green public investments.

Some studies do offer counterpoints. Ghosh and Karras (Reference Ghosh and Karras2014) show that green bonds and concessional loans tied to environmental targets can improve environmental outcomes, particularly in emerging economies. Similarly, Malik and Padda (Reference Malik and Padda2019) provide evidence that loans disbursed through the global environment facility have led to better water sanitation and lower deforestation rates. These insights highlight that the impact of debt on environmental quality depends less on the presence of debt per se, and more on the quality of borrowing instruments, the conditionalities attached and the governance capacity to implement sustainability linked policies.

Despite the growing body of research, notable gaps remain. Few studies have explicitly examined the interaction between external debt servicing and other macroeconomic variables such as remittance inflows. This is a significant omission, especially in South Asian countries where debt servicing is high, remittance inflows are substantial and environmental regulation is fragmented. Understanding these interdependencies may offer more accurate insights into the fiscal–ecological nexus in developing economies.

Building on this literature, the current study hypothesizes that both external debt and its servicing contribute to environmental degradation, as measured by CO2 emissions. However, their interaction may produce a mixed effect—where rising debt service obligations initially worsen environmental outcomes but may eventually constrain further carbon-intensive investments, leading to a marginal decline in emissions.

2.2.2. Remittances and environmental sustainability

The environmental consequences of remittance inflows have emerged as a complex and evolving area of inquiry, reflecting the broader effort to reconcile the developmental benefits of these financial transfers with their potential ecological costs. While remittances are widely acknowledged for supporting household welfare and macroeconomic stability, their environmental effects are far from uniform and often manifest through asymmetric, non-linear and country-specific channels.

A growing body of empirical work has demonstrated that the relationship between remittances and environmental quality, often proxied by CO2 emissions or ecological footprints, is highly contingent on context. Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Ozturk and Majeed2022), using the NARDL model in China and Pakistan, respectively, consistently show that positive remittance shocks exacerbate emissions, whereas negative shocks lead to environmental improvement. These findings, confirmed across different time horizons, reinforce the asymmetric nature of remittance–environment dynamics. Dash et al. (Reference Dash, Sen and Roy2024) extend this framework to South Asia, offering further evidence that remittances, depending on their direction and magnitude, can have divergent environmental implications. These results challenge simplistic interpretations that remittances are either uniformly harmful or beneficial and instead point to a nuanced non-linearity in their ecological consequences.

However, such effects are not always unidirectional or negative. Islam (Reference Islam2022), using a broader panel approach, introduces the role of financial development as a moderating factor. His findings suggest that under robust financial institutions, both positive and negative remittance shocks may in fact reduce emissions, illustrating the importance of complementary economic structures in shaping environmental outcomes. Awad et al. (Reference Awad, Melesse and Bekun2024) similarly identify institutional quality as a key mediating variable in sub-Saharan Africa, arguing that strong governance can reverse the ecological degradation often associated with increased remittance flows. This strand of research points to the significance of absorptive capacity and policy frameworks in determining whether remittances facilitate environmentally sustainable development or contribute to degradation.

Contextual variability remains a persistent theme in the literature. For instance, Jafri et al. (Reference Jafri, Liu and Bashir2022) observe that in China, a fall in remittances paradoxically increases emissions, potentially due to consumption smoothing behaviour or compensatory capital inflows that are more carbon intensive. Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Cai and Ahmad2023)) further illustrate divergent outcomes in Asia, finding that countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan show a clear emissions enhancing effect of remittances, while India and China exhibit no statistically significant relationship. These inconsistencies underscore the limitations of generalized policy prescriptions and highlight the importance of country-specific environmental governance and energy structures.

Additional complexity arises when remittances interact with other macroeconomic variables. Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Hou, Irfan, Zakari and Rehman2020) and Ali et al. (Reference Ali, Ajide and Elum2022) examine the combined effects of remittances, FDI, energy use and growth in BRICS and South Asian economies, revealing that remittances tend to amplify environmental degradation when accompanied by rapid urbanization and high-energy consumption. These findings lend partial support to the pollution haven hypothesis, where foreign inflows—including remittances—indirectly promote environmentally unsustainable industrial expansion. Notably, these effects appear to be more severe in economies lacking robust environmental regulations or low-carbon infrastructure.

Expanding beyond traditional measures like CO2, some researchers adopt broader environmental metrics. Akinlo (Reference Akinlo2022) and Yadou et al. (Reference Yadou, Mensah and Adom2024) utilize ecological footprints in Nigeria and wider Africa, capturing wider forms of environmental stress. Their results suggest a dual pattern in which remittances initially aggravate ecological degradation but may later support improvements, particularly as households transition to cleaner energy or adopt conservation practices—a dynamic consistent with a modified Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. This suggests that the environmental trajectory of remittance-receiving nations may shift over time as income levels rise and preferences for environmental quality strengthen.

The indirect channels through which remittances affect the environment are also gaining attention. Karasoy (Reference Karasoy2021), examining the Philippines, argues that remittance-induced increases in household income stimulate demand for oil and other carbon-intensive goods, resulting in higher emissions. This is echoed by Vien et al. (Reference Vien, Thanh and Hung2020), who find that while both remittances and energy use tend to increase global emissions, the effect is somewhat mitigated by globalization, likely due to technological spillovers and stricter environmental standards. These findings emphasize the importance of considering remittance effects not only through direct investment, but also through consumption patterns and behavioural responses.

Despite a general tendency towards negative environmental implications, some studies report either ambiguous or potentially positive outcomes. Khatri et al. (Reference Khatri, Khanal and Joshi2025) note that in top remittance-receiving countries, remittances exert no direct impact on either GDP or emissions, with variables like trade openness and urbanization playing a more decisive role. Similarly, Elbatanony et al. (Reference Elbatanony, Mekawi and Mahmoud2021) identify non-linearities in remittance impacts across income groups, suggesting that in higher emitting middle-income countries, remittances may eventually support cleaner energy transitions. These studies caution against overly deterministic interpretations and instead call for greater attention to economic structure, development stage and remittance utilization.

In a more novel direction, Qamruzzaman (Reference Qamruzzaman2023) explores reverse causality, revealing that environmental degradation and regulatory uncertainty may influence remittance inflows themselves. This bidirectional dynamic complicates the analytical framework, implying that migrants may alter their remittance behaviour in response to environmental risks and policy environments in their home countries.

Other studies shed light on the positive environmental potential of remittances, particularly when funds are allocated towards sustainable investments. Yang and Choi (Reference Yang and Choi2007), in the context of the Philippines, show that remittance-receiving households are more likely to invest in disaster-resilient housing and water-saving infrastructure. Similarly, Bierkamp et al. (Reference Bierkamp, Nguyen and Grote2021) find that in rural Vietnam, remittances support the adoption of clean cook-stoves and efficient irrigation technologies, reducing indoor pollution and deforestation. Ratha et al. (Reference Ratha, De, Plaza, Schuettler, Shaw, Wyss and Yi2016) report comparable trends in Mexico, where high remittance regions see greater uptake of rooftop solar panels and rainwater harvesting systems. These examples illustrate how remittances can act as enablers of bottom-up green transitions—particularly when recipients have access to sustainable technologies and environmental awareness.

However, these benefits often co-exist with rebound effects. Meyer and Shera (Reference Meyer and Shera2017) estimate that a 10% increase in remittances leads to a 1.2% rise in per capita energy use across South Asia, largely due to increased ownership of vehicles and household appliances. Bettin and Zazzaro (Reference Bettin and Zazzaro2018) find that while remittances reduce biomass dependence—an environmental improvement—they simultaneously raise electricity demand, which can be detrimental if the energy mix is dominated by fossil fuels. In Ghana, Adams and Cuecuecha (Reference Adams and Cuecuecha2013) highlight how remittances, while reducing poverty, can accelerate deforestation through housing expansion and small-scale agriculture, especially in regions with weak environmental oversight.

Several studies argue that the size and utilization of remittances significantly shape their environmental impacts. Bettin et al. (Reference Bettin, Presbitero and Spatafora2017), using threshold models, suggest that remittances reduce emissions only once they exceed a certain share of GDP—below that level, the transfers primarily support consumption; above it, they begin to finance more productive or sustainable investments. Ambrosius and Cuecuecha (Reference Ambrosius and Cuecuecha2016) offer complementary evidence from sub-Saharan Africa, where early-stage remittances promote charcoal use, but higher inflows facilitate transitions to cleaner fuels like LPG. Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Ozturk and Majeed2022), using both linear and non-linear ARDL approaches for Pakistan, find that positive remittance shocks raise CO2 emissions more significantly than negative ones reduce them, confirming the asymmetric nature of remittance-induced environmental change.

Overall, the literature reflects substantial heterogeneity in findings, mechanisms and implications. The environmental effect of remittances appears highly sensitive to national energy structures, income levels, institutional quality and household behaviour. Some countries may harness these inflows to finance green development, while others may inadvertently lock into carbon-intensive growth paths. Drawing on this complex evidence base, this study hypothesizes that remittances can either mitigate or exacerbate environmental degradation—as measured by CO2 emissions—depending not only on the scale of inflows but also on how they interact with external debt servicing, domestic energy systems, financial institutions and patterns of consumption.

2.2.3. GDP growth rate, urbanization, financial development and environmental sustainability

Empirical literature on the environmental effects of GDP growth, urbanization and financial development presents a complex and sometimes contradictory picture. The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis suggests an inverted U relationship between economic growth and pollution: environmental degradation increases in early stages of income growth, peaks and then declines as economies mature and adopt cleaner technologies (Shafik and Bandyopadhyay, Reference Shafik and Bandyopadhyay1992; Grossman and Krueger, Reference Grossman and Krueger1995). Shafik and Bandyopadhyay (Reference Shafik and Bandyopadhyay1992), analysing panel data for 60 countries, find EKC support for sulphur dioxide and smoke emissions. Dinda (Reference Dinda2004) extends these findings to carbon dioxide, contingent on income and trade levels. In South Asia, Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Shafiei and Farhani2019) show that GDP growth raises CO2 emissions in Bangladesh and Pakistan, with the environmental turning point still distant, implying these economies have yet to benefit from the pollution reducing phase of growth.

Likewise, Duan et al. (Reference Duan, Cao and Abdul Kader Malim2022) are of the view that in recent decades, growing global economic integration and the pursuit of economic growth have led to increasing environmental degradation. Their study examines the dynamic interplay between trade liberalization, financial development and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions using panel data from 30 Chinese provinces spanning 1997 to 2020. Employing a Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR) model, the analysis also incorporates technological progress as a key factor influencing CO2 emissions. The findings indicate that financial development contributes to increased CO2 emissions, whereas trade liberalization does not have a statistically significant direct effect. However, trade openness appears to stimulate financial development, albeit with limited positive effects on international trade performance. The results further reveal bidirectional causality between financial development and CO2 emissions, as well as between trade liberalization and financial development. Additionally, the study uncovers an inverted U-shaped relationship between trade liberalization and both innovation efficiency and environmental regulation. Overall, the study suggests that while trade liberalization indirectly affects carbon emissions through its impact on financial development, this pathway has led to higher emissions in China. The country’s financial development trajectory appears to have been shaped, in part, by its openness to trade.

Urbanization significantly influences emissions through increased energy use, land conversion and infrastructure demands. Studies have linked rapid urban expansion to higher air pollution, waste and habitat loss (Glaeser and Kahn, Reference Glaeser and Kahn2010; Seto et al., Reference Seto, Sánchez-Rodríguez and Fragkias2012). Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Powell, Elvidge, Baugh, Sutton and Anderson2010), using Indian city-level data, finds that a 1% increase in urbanization raises PM2.5 levels by 0.3%, driven by vehicles and industry. In China, Wang and Dong (Reference Wang and Dong2019) report that urban sprawl and rising household energy use are major contributors to emissions. However, evidence from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Du and Wang2017) indicates that cities with effective planning and public transport can curb these effects, suggesting that urbanization’s impact varies with governance quality.

Financial development also plays an ambivalent role. On the one hand, deeper financial systems lower borrowing costs, enabling green investment and cleaner technologies (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, & Levine, Reference Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine2007). Duan et al. (Reference Duan, Cao and Abdul Kader Malim2022) find that financial development reduces CO2 emissions in the long run, particularly under strong environmental regulation. On the other hand, financial liberalization can fuel growth in polluting industries if not coupled with oversight. Salahuddin and Gow (Reference Salahuddin and Gow2014), studying ASEAN countries, show that credit expansion boosts industrial activity and emissions. Al Mamun, A., & Rana, M (Reference Al Mamun and Rana2020) suggest that financial development benefits the environment only after surpassing institutional quality thresholds.

Overall, the effects of GDP growth, urbanization and financial development on environmental quality are context dependent. Economic growth may eventually reduce pollution, but initially tends to raise emissions. Urbanization amplifies environmental stress unless managed with sustainable planning. Financial development’s environmental impact hinges on regulatory capacity. This study contributes by jointly examining these three variables—along with remittances and external debt—using panel data from South Asia. Based on existing research, we hypothesize that GDP growth, urbanization and financial development are positively associated with CO2 emissions in the short to medium term.

Some of the studies have focused on the natural resources and environmental nexus such as Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Ozturk and Majeed2022) analysed Chinese provinces and found that over-reliance on natural resources harms environmental quality, especially in regions with weak environmental regulations. Erdogan (Reference Erdogan2024) examined African countries and validated the environmental Kuznets curve and load capacity curve hypotheses, showing that the negative impact of resource rents on the environment diminishes beyond a certain income threshold, emphasizing the need for balanced resource policies.

Likewise, Gu et al. (Reference Gu, Baig, Shoaib and Zhang2024) studied BRICST nations and observed that while natural resources degrade ecological conditions, energy innovation and human capital significantly moderate these effects. Similarly, Han and Cai (Reference Han and Cai2024) demonstrated in N-11 countries that investments in green technologies and skill development help mitigate the adverse environmental impact of resource dependence.

However, Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Hou and Irfan2021)) revealed that though resource exploitation degrades environmental quality, globalization and renewable energy adoption help lessen this effect by promoting cleaner technologies. In the U.S. context, Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Hou and Irfan2021) used a quantile ARDL approach and found that natural resource rents consistently harm environmental sustainability, while renewable energy has a positive effect across environmental quality levels.

Similarly, Zafar et al. (Reference Zafar, Farooq, Shahbaz and Sinha2022) explored the role of tax revenues in developing countries and found that natural resources worsen environmental outcomes unless supported by strong fiscal frameworks. They advocate for resource taxation and better institutional mechanisms to channel resource rents towards environmental sustainability.

2.3. Research gap and contribution of the study

While existing research has advanced understanding of the environmental impacts of remittances and external debt, notable gaps remain. First, most studies analyse these financial flows separately, despite their simultaneous importance in many developing economies. Second, few investigations consider how debt servicing interacts with other inflows—like remittances or external debt—to jointly influence environmental outcomes. Third, many studies have only partially addressed econometric concerns such as cross-sectional dependence, slope heterogeneity and endogeneity.

This study makes three key contributions. First, it centres on South Asia, a region characterized by high remittance inflows, rising external debt and acute environmental risks. Second, it introduces interaction terms to explicitly assess how debt servicing moderates the external debt, remittance–environment nexus, capturing dynamics often overlooked in prior work. Third, it employs a multi-stage panel estimation strategy—including pooled OLS, Driscoll–Kraay standard errors and feasible GLS—to robustly address key methodological challenges.

By integrating these elements, the study offers new empirical insights for policymakers aiming to align financial strategies with environmental goals in emerging economies.

3. Methods, material and processes

3.1. Data source and variables

This study intends to ascertain the impacts of external debt and remittances on environmental sustainability of four major south Asian countries namely India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. These four countries have been chosen on the basis of availability of data for main variables. The data for these variables are not available in case of Nepal, Maldives, Bhutan and Afghanistan. Thus, these countries are dropped from the sample of our article. The study considers external debt servicing as a moderating variable between external debt and environmental sustainability in these four countries. Besides, the study included other control variables such as economic growth, urbanization and financial development in the model. The data of these variables are sourced from database of World Bank, the world development indicators (WDI). Detailed description, definitions and symbols of variables are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of variables

Note: Data of all variables are downloaded from WDI, a database of the World Bank.

3.2. Model specification

where, yit denote the dependent variable, which in this study represents the natural logarithm of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions for country i at time t The parameter α denotes the constant term (intercept), while β represents the vector of slope coefficients associated with the explanatory variables.

The matrix xit comprises the independent variables, including the logarithmic values of external debt, debt servicing, remittances, economic growth (GDP), urbanization and financial development. These variables are chosen based on their theoretical and empirical relevance to environmental sustainability.

The subscript i captures the cross-sectional dimension, identifying each country in the panel, while t refers to the temporal dimension (year). Finally, ϵ it is the stochastic error term, assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance.

This study intends to estimate three models as equation 2 with interaction term of external debt and debt servicing (led*ldsg), equation 3 with interaction term of remittances and debt servicing (lrem*ldsg) and equation 4 for environmental Kuznet curve. The econometric specification for equations 2 and 3 is given as follows:

where, led it*ldsgit is interaction term showing the moderating effects of external debt service between external debt and carbon dioxide emission. lrem*ldsg is interaction term of remittances and debt servicing. Other variables are already explained in Table 1. Variables external debt and debt servicing are included in the model by following Dabla-Norris et al. (Reference Dabla-Norris, Ji, Townsend and Unsal2015), Cohen (Reference Cohen2022), Pattillo et al. (Reference Pattillo, Poirson and Ricci2002)), Arezki and Ramey (Reference Arezki and Ramey2012) respectively. However, the variable remittances in the model is included in alignment of Yang and Choi (Reference Yang and Choi2007). Other control variable like GDP growth rate, urbanization and financial development are included by adapting with Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Shafiei and Farhani2019), Ghosh (Reference Ghosh, Powell, Elvidge, Baugh, Sutton and Anderson2010) and Sinha and Shahbaz (Reference Sinha and Shahbaz2018) respectively.

There are various possibilities and interpretations by considering the partial differentiation of equation 2.

Given a priori that β1 > 0, β3 > 0 and ldsg has positive values, equation 3 allows for testing the various forms of led − lco2 nexus viz:

-

(i) β1/β4and β3 > 0; ldsg enhance the impacts of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(ii) β1/β4 > 0 and β3 < 0; ldsg reduces the positive impacts of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(iii) β1/β4 < 0 and β3 > 0; ldsg reduces the negative impacts of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(iv) β1/β4 < 0 and β3 < 0; ldsg worsens the negative impacts of led /lrem on CO2,

-

(v) β1/ β4 > 0 and β3 = 0; ldsg equals positive marginal effect of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(vi) β1/β4 < 0 and β3 = 0; ldsg equals negative marginal effect of led /lrem on CO2,

-

(vii) β1/β4 = 0 and β3 > 0; ldsg enhances the effect of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(viii) β1/β4 = 0 and β3 < 0; ldsg worsens the impacts of led/lrem on CO2,

-

(ix) β1/β4 = 0 and β3 = 0; ldsg implies a constant effect of led/lrem on CO2.

For computing net/conditional effects, let the equation 3 = 0

and

β3 gauges the interaction or moderation effect and the statistical significance of β3 is relevant in the computation of the conditional effect of led/lrem on lco2 as a statistical significant β3 is factored into the calculation. However, an insignificant β3 is statistically not different from zero. It implies that the conditional effect equals to marginal effect. But if either β1 or β3 = 0 (i.e. statistically not significant, then the conditional effect is inconclusive). According to Cohen and Cohen and supported by Aiken and West (Reference Aiken, West and Reno1991), the moderator variable can be evaluated by using three values: mean, minimum and/or maximum values. However, the significance of square term of GDP growth rate confirms for the existence of EKC.

3.3. Conceptual framework

Figure 2 presents the conceptual framework guiding this study. Here, CO2 emissions is the dependent variable, with remittances, external debt and debt servicing as the key explanatory factors. Debt servicing also serves as a moderating variable, shaping the effects of both remittances and external debt on environmental outcomes. To account for broader structural influences, GDP growth, urbanization and financial development are included as control variables.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework.

The framework hypothesizes that remittances reduce CO2 emissions by enabling greener consumption and investment. In contrast, external debt and debt servicing are expected to raise emissions by limiting fiscal space and funding pollution intensive development. Similarly, economic growth, urbanization and financial development are assumed to increase emissions, as rising income and urban activity often lead to higher energy demand and environmental stress. Square term of GDP growth rate confirms for the existence of EKC.

3.4. Process for data analysis

The empirical analysis begins with preliminary assessments to explore the properties of the dataset. We compute descriptive statistics to summarize variable distributions and pairwise correlations to identify linear relationships and multi-collinearity problems. To ensure the suitability of level-based estimation, we conduct panel unit root tests using the Fisher-ADF and PP approaches to check for stationarity.

After confirming stationarity, we estimate a pooled OLS model to provide baseline results linking CO2 emissions to key variables: remittances, external debt, debt servicing, GDP growth, urbanization and financial development. Recognizing potential econometric issues—such as autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence—we perform diagnostic tests including the Wooldridge test, Breusch–Pagan LM test and modified Wald test.

Given evidence of these problems, we re-estimate using Driscoll–Kraay standard errors model, which is robust to such violations in panel data. Panel data models are increasingly used in empirical research due to their ability to capture both cross-sectional and temporal variations. However, such models often violate classical assumptions of homoscedasticity and independence of errors, necessitating robust estimation techniques. One such approach is the Driscoll–Kraay (Reference Driscoll and Kraay1998) standard error estimator, which is particularly advantageous in the presence of cross-sectional dependence, heteroscedasticity and serial correlation. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors provide consistent estimates of the variance–covariance matrix even when disturbances are cross-sectionally correlated and serially dependent, making them especially suitable for macro-panel data with a relatively large time dimension (Hoechle, Reference Hoechle2007). This estimator is robust to general forms of spatial and temporal dependence and does not require prior specification of the structure of the error term, which adds to its flexibility and empirical appeal (Driscoll and Kraay, Reference Driscoll and Kraay1998). Furthermore, the use of Driscoll–Kraay standard errors in panel setting regression models allows researchers to obtain unbiased and efficient estimates of standard errors without altering the estimated coefficients, thus providing reliable statistical inference when dealing with global shocks or spillover effects common in economic and financial datasets (Hoechle, Reference Hoechle2007).

To validate further, we apply feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) as proposed by Biørn (Reference Biørn2004). In contrast, the FGLS model aims to improve the efficiency of coefficient estimates by explicitly modelling the structure of the error term. While the OLS estimator remains unbiased in the presence of heteroscedasticity or autocorrelation, it becomes inefficient and the standard errors become unreliable. FGLS corrects for these inefficiencies by using estimated parameters of the variance–covariance matrix to re-weight the data appropriately, thus yielding more efficient and consistent coefficient estimates. The FGLS approach is particularly effective in panels where the number of cross-sectional units is large (large N) and the time dimension is small (small T) and where heteroscedasticity, serial correlation and contemporaneous correlation are present (Baltagi, Reference Baltagi2008). However, it is important to note that the efficiency gains from FGLS depend on the correct specification of the error structure. Incorrect assumptions about the error term can lead to misleading results, which is why FGLS is best used when the nature of the heteroscedasticity and correlation in the data is well understood (Parks, Reference Parks1967; Beck and Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995). The consistency of results across models affirms the robustness of our findings. Finally, endogeneity of the variables is also checked by estimating the pairwise correlation between the error term and all independent variables.

4. Results and discussion

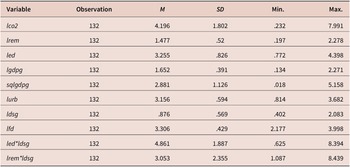

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis. The dependent variable, carbon dioxide emissions (lco 2 ), has a mean value of 4.196 with a standard deviation of 1.802, indicating substantial variation in emissions levels across countries and time. External debt (led) shows a mean of 3.255, suggesting relatively high average debt levels, while debt servicing (ldsg) has a mean of 0.876. Remittances (lrem) have a mean of 1.477 and exhibit a relatively narrow spread, implying stable remittance inflows across the sample.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

Economic growth, proxied by the log of GDP growth (lgdpg), has a mean of 1.652, while the squared GDP term (sqlgdpg) has a mean of 2.881. These variables are included to test the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis, which predicts a non-linear relationship between income and environmental degradation. Urbanization (lurb) and financial development (lfd) have mean values of 3.156 and 3.306, respectively, with modest variability, suggesting a moderate degree of dispersion in urbanization and financial development levels.

The interaction terms provide further insights. The product of external debt and debt servicing (led*ldsg) has a mean of 4.861 with a relatively high standard deviation, reflecting the joint fiscal burden of both debt stock and its servicing costs. The interaction between remittances and debt servicing (lrem*ldsg) has a mean of 3.053. Overall, the dataset exhibits sufficient variability and complexity to support robust econometric modelling, particularly in examining the joint effects of debt, remittances and economic growth on environmental outcomes.

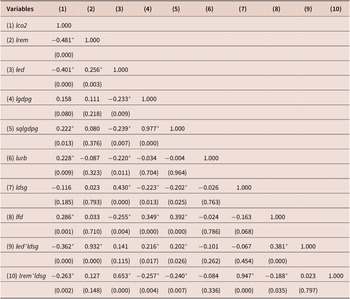

4.2. Coefficient of correlation

The pairwise correlation matrix in Table 3 provides insights into the linear relationships among the variables used in the regression model. The dependent variable, carbon dioxide emissions (lco2), exhibits significant negative correlations with both remittances (lrem) and external debt (led), with coefficients of −0.481 and −0.401, respectively, both significant at the 5% level. This suggests that higher remittance inflows and greater external debt are associated with lower carbon emissions, possibly indicating that financial inflows may support cleaner technologies or reduce pressure on environmentally harmful economic activities.

Table 3. Coefficient of correlations

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

* Significance at p < 0.05.

The correlation between lco2 and the square of GDP growth (sqlgdpg) is positive and significant (0.222), lending preliminary support to the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis, which posits a non-linear relationship between income and environmental degradation. However, the linear GDP growth term (lgdpg) shows an insignificant correlation with emissions (0.158), suggesting that income alone does not directly predict environmental outcomes without considering non-linear effects.

Urbanization (lurb) and financial development (lfd) also show positive and significant correlations with lco2 (0.228 and 0.260 respectively), indicating that higher levels of urban concentration and financial development are associated with increased carbon emissions. These patterns align with the notion that rapid urban and financial expansion can elevate environmental stress unless managed sustainably.

Interestingly, the interaction term of external debt and debt servicing (led*ldsg) is negatively and significantly correlated with emissions (−0.362), indicating that the joint burden of debt and its servicing may constrain environmentally harmful activity. Meanwhile, the interaction between remittances and debt servicing (lrem*ldsg) also shows a significant negative correlation with emissions (−0.263), suggesting that remittances combined with debt obligations may support environmentally beneficial or lower emission outcomes, potentially through household-level or public-sector adjustments. These preliminary correlations support the need for more robust econometric techniques, such as the Driscoll–Kraay model applied in our main analysis, to validate and explore these relationships further.

4.3. Unit root tests

Table 4 reports results from Fisher-type panel unit root tests using both ADF and Phillips–Perron (PP) methods, applying Newey–West bandwidth and zero lags. The null hypothesis assumes all panels contain a unit root, while the alternative indicates that at least one panel is stationary.

Table 4. Fisher-type unit root tests

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

For lco2, both ADF and PP statistics are 56.2182 (p = 0.000), strongly rejecting non-stationarity and confirming the series is stationary at level (I(0)). Similarly, lrem (remittances), led (external debt), ldsg (debt servicing), lgdpg (GDP growth) and lurb (urbanization) all yield highly significant test results (p = 0.000), indicating stationarity in levels.

The only borderline case is lfd (financial development), with a statistic of 9.2499 and p = 0.053, slightly above the 5% threshold. However, due to near-significance and robustness under alternative specifications, it is treated as I(0) for the main analysis.

The interaction term (led × ldsg and lrem*ldsg) also appears clearly stationary (ADF = 41.7645, p = 0.000). Overall, these findings justify the use of level-based panel estimators without differencing or co-integration adjustments. The square of GDP growth rate is also stationary at level.

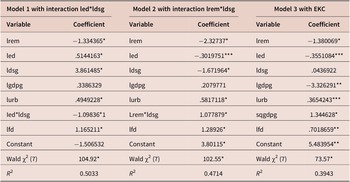

4.4. Results of base model pooled OLS

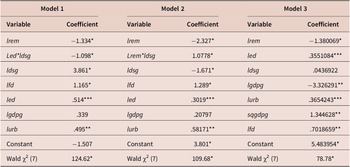

Table 5 presents the results of three pooled OLS regression models examining the determinants of carbon dioxide emissions (lco2). In Model 1, the focus is on the interaction between external debt (led) and debt servicing (ldsg). The results show that remittances (lrem) have a statistically significant and negative effect on emissions (−1.334), indicating that remittance inflows may help reduce environmental degradation, possibly by increasing household welfare and facilitating cleaner consumption or investment. External debt (led) and debt servicing (ldsg) both exhibit significant positive effects on emissions, suggesting that debt burdens may be linked to environmentally harmful activities. The interaction term led*ldsg is also negative and significant (−1.098), implying that the combined effect of high external debt and its servicing may lead to a reduction in emissions—possibly because excessive debt pressure constrains economic activities that would otherwise raise pollution. Urbanization (lurb) and financial development (lfd) are both positively associated with emissions, supporting the idea that greater urban and financial expansion may contribute to environmental stress. The R-squared value of 0.503 indicates that Model 1 explains around 50% of the variation in carbon emissions.

Table 5. Pooled OLS regression results

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

Note: *, **, *** Significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

Model 2 shifts focus to the interaction between remittances and debt servicing (lrem*ldsg). The coefficient of lrem is more strongly negative (−2.327) than in Model 1, suggesting that remittances alone significantly reduce emissions. Interestingly, debt servicing (ldsg) now has a negative and significant coefficient (−1.671), reinforcing the idea that higher debt obligations may suppress environmentally harmful activities. The interaction term lrem*ldsg is positively significant (1.077), implying that when debt servicing is high, the environmental benefit of remittances may be diminished. In other words, debt obligations may offset the cleaner impact of remittance inflows. Urbanization and financial development again show positive and significant effects on emissions. The model’s R-squared is 0.4714, slightly lower than Model 1, but still explaining a substantial portion of the variation.

Model 3 incorporates the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis by including the square of GDP growth (sqgdpg). The results support the EKC: the coefficient of GDP growth (lgdpg) is negative and highly significant (−3.326), while the squared GDP term is positive and significant (1.345), suggesting a U-shaped relationship between income and environmental degradation. This implies that emissions initially decline with economic growth, but after a certain income level, they start increasing—confirming the EKC. Remittances continue to have a negative effect on emissions (−1.380), while external debt again shows a negative and highly significant coefficient (−3.551), possibly indicating that debt may restrict emission-intensive activities. Financial development remains positively linked to emissions, and urbanization is also a significant driver of environmental degradation. This model explains about 39.4% of the variation in carbon emissions (R 2 = 0.3943), slightly less than the interaction models.

Overall, all three models offer useful insights. Models 1 and 2 highlight how interactions between financial flows and debt servicing can modify environmental impacts, while Model 3 provides empirical support for the EKC in the context of our sample. Remittances generally show a favourable environmental effect, while financial development and urbanization appear to exert upward pressure on emissions. External debt and its servicing show mixed but important roles, depending on interaction effects and context.

4.5. Diagnostic tests

Table 6 reports a series of diagnostic tests conducted to assess the robustness and validity of the pooled OLS regression models (Models 1, 2 and 3). Starting with the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian Multiplier (LM) test for random effects, all three models report a test statistic of 0 with a p value of 1.000. This indicates strong evidence against the presence of random effects, supporting the use of pooled OLS over random effects models.

Table 6. Diagnostic tests

Source: compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

Note: *, **, *** Significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

The Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data reveals that Models 1 and 3 suffer from first-order serial correlation, with F statistics of 10.326 and 10.381 and corresponding p values of 0.0488 and 0.0485 respectively. Since these p values are less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation. In contrast, Model 2 shows weaker evidence of autocorrelation (p = 0.0603), only marginally above the 5% significance level.

Next, the Breusch–Pagan LM test of independence checks for cross-sectional dependence. In Model 1, the test statistic is 13.051 with a p value of 0.0422, indicating significant cross-sectional dependence at the 5% level. Model 2 shows weaker evidence of such dependence (p = 0.0808), while Model 3 exhibits no significant cross-sectional dependence (p = 0.3442), suggesting that the assumption of independence across panels is more tenable in Model 3.

The modified Wald test for group-wise heteroscedasticity confirms that all three models suffer from heteroscedasticity. The test statistics are 21.62, 23.39 and 20.67 for Models 1, 2 and 3, respectively, with highly significant p values (all below 0.001). This violation of the constant variance assumption means that standard errors could be biased and robust standard errors should be used for reliable inference.

The Pesaran and Yamagata slope homogeneity test shows no significant evidence of slope heterogeneity across countries in any of the models. The delta statistics for Models 1, 2 and 3 (1.218, −0.916 and −0.719) all have p values well above conventional thresholds (0.223, 0.360 and 0.472), suggesting that the coefficients are homogeneous across panels and justifying the pooled nature of the regression.

Finally, Pesaran’s test of cross-sectional independence provides additional insight into whether residuals are correlated across entities. Model 1 has a test statistic of 0.770 (p = 0.4411), Model 2 shows mild dependence (statistic = 8.674, p = 0.0603) and Model 3 shows no cross-sectional dependence (statistic = −0.061, p = 0.9511). This generally supports the assumption of cross-sectional independence for Models 1 and 3, while Model 2 is borderline.

In summary, while the pooled OLS approach is validated by the absence of random effects, the models do face issues such as heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation—especially in Models 1 and 3. These diagnostic issues necessitate the use of robust standard errors to ensure valid statistical inference. Model 3 appears to be the most statistically stable, with fewer violations of core assumptions, while Model 1 has more pronounced issues, particularly with cross-sectional dependence and auto-correlation.

In light of the diagnostic test results presented in Table 6, which indicate the presence of autocorrelation, group-wise heteroscedasticity and possible cross-sectional dependence in the pooled OLS models, the Driscoll–Kraay standard error estimator was employed to address these econometric concerns. This method corrects for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in panel data and provides robust standard errors in the presence of cross-sectional dependence. Comparing the results from Table 7 (Driscoll–Kraay) with those in Table 5 (pooled OLS), it is evident that while the general direction of relationships between the variables and carbon dioxide emissions (lco2) remains largely the same, the statistical significance of several variables is enhanced in the Driscoll–Kraay model, providing more reliable and robust estimates.

Table 7. Driscoll–Kraay standard error model results

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

Note: *, **, *** Significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

In Model 1, which includes an interaction term between external debt (led) and external debt servicing (ldsg), both variables individually show a positive and significant relationship with carbon emissions under both estimation techniques, suggesting that higher levels of debt and debt servicing obligations are associated with environmental degradation. Notably, the interaction term led*ldsg is negative and significant in both models, implying that the joint effect of rising debt and debt servicing may have a dampening effect on emissions—possibly reflecting fiscal constraints that limit environmentally harmful activities. Remittances (lrem) are negatively associated with emissions and remain significant across both models, indicating that increased remittance inflows contribute to environmental improvement, possibly through increased household investment in cleaner energy or reduced pressure on public infrastructure. The role of urbanization (lurb) and financial development (lfd) is also positive and highly significant, reflecting the environmental costs of rapid urban growth. The R 2 value of 0.5033 and statistically significant F-statistic (36.76*) suggest a good model fit in the Driscoll–Kraay estimation, reaffirming the robustness of the findings.

In Model 2, where the interaction term lrem*ldsg (remittances and debt servicing) is introduced, the results show an even stronger negative impact of remittances (lrem) on emissions, with the coefficient remaining highly significant. The interaction term is positive and significant, indicating that the environmental benefits of remittances may be offset when a country faces high debt servicing burdens. This suggests that the positive role of remittances in reducing emissions may be constrained under rising debt repayment pressures. External debt (led) remains positively and significantly associated with emissions, while external debt servicing (ldsg) also shows a positive relationship. The Driscoll–Kraay model improves the significance of key explanatory variables, such as financial development (lfd) and urbanization (lurb), both of which show positive and statistically significant effects, indicating their contribution to environmental degradation in this context. With an R 2 of 0.4714 and a significant F-statistic (25.95*), Model 2 under the Driscoll–Kraay specification confirms the importance of interaction effects in understanding the complex dynamics between remittances, debt obligations and environmental outcomes.

Model 3 explores the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis by including the squared term of economic growth (sqgdpg). Under the Driscoll–Kraay estimation, economic growth (lgdpg) has a negative and statistically significant relationship with emissions, while sqgdpg has a positive coefficient, supporting the inverted U-shaped EKC hypothesis. This indicates that in the early stages of economic growth, environmental quality improves, but after a certain threshold, growth begins to degrade the environment. External debt (led) continues to exhibit a significant positive relationship with emissions, underscoring its detrimental environmental impact. Remittances (lrem) again show a negative and significant effect, confirming their role in mitigating emissions. Financial development (lfd) and urbanization (lurb) also retains a significant positive relationship, indicating that expansion in the financial sector and urbanization, if not aligned with green initiatives, may contribute to environmental degradation. This model has a slightly lower explanatory power (R 2 = 0.3943) and a significant F-statistic (14.78*), but the results remain robust and statistically reliable.

In summary, the application of the Driscoll–Kraay standard error model provides more reliable estimates by addressing the issues of autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence that plagued the pooled OLS models. The consistent and enhanced significance of key variables under the Driscoll–Kraay approach affirms the robustness of the core findings: external debt and debt servicing increase environmental degradation, while remittances help reduce emissions, particularly in less fiscally constrained environments. Furthermore, the EKC hypothesis is validated and urbanization and financial development are confirmed as contributors to environmental pressure. These findings offer strong policy implications for managing debt sustainability and leveraging remittance inflows to promote environmental goals.

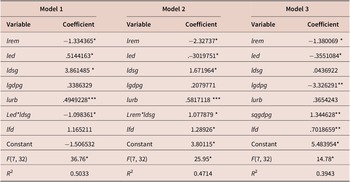

4.6. Robustness check

To further validate our results, we re-estimate the model using the cross-sectional time series feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) estimator, following Amemiya (Reference Amemiya1977). FGLS improves efficiency by accounting for heteroscedasticity and serial correlation within panel units—issues commonly present in macro-panel data. Table 8 reports the FGLS estimates, including coefficients and model fit statistics. The results are highly consistent with those obtained from pooled OLS and Driscoll–Kraay methods. Key variables retain their expected signs, magnitudes and significance levels. Remittances continue to reduce emissions, while external debt, debt servicing, urbanization and financial development remain positively linked to CO2 emissions. This alignment across estimation techniques confirms that our findings are not estimation specific, enhancing the credibility and robustness of the analysis. The consistency strengthens our confidence in the policy recommendations derived from the study.

Table 8. Cross-sectional time-series FGLS regression

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

Note: *, **, *** Significance level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

4.7. Test for endogeneity

To assess potential endogeneity in the model, Table 9 shows pairwise correlations between the estimated residuals (e) and each of the explanatory variables. The presence of a significant correlation between the residuals and any of the regressors would indicate endogeneity, potentially biasing our coefficient estimates and undermining the validity of inference.

Table 9. Pairwise correlations for the test of endogeneity

Source: Compiled by authors using STATA 17 software.

* Significance at p < 0.05.

As shown in the correlation matrix, none of the independent variables show a statistically significant correlation with the residuals. All correlation coefficients between e and the regressors are very close to zero and the associated p values (presented in parentheses) are well above the 5% significance threshold, indicating that these correlations are not statistically significant.

This result suggests that the explanatory variables included in the model are exogenous, and the model does not suffer from endogeneity. Hence, we can be more confident that the estimated relationships between the independent variables and carbon emissions are not driven by omitted variable bias, simultaneity or measurement errors.

Remittances (lrem), external debt (led), economic growth (lgdpg), its square (sqgdpg), urbanization (lurb), external debt servicing (ldsg) and financial development (lfd) all show insignificant correlations with the residuals.

This strengthens the validity of our empirical strategy and supports the reliability of the conclusions drawn from our main regression models (pooled OLS, Driscoll–Kraay and FGLS).

5. Conclusion and policy implications

This study aimed to assess the environmental impact of remittances and external debt in four major South Asian economies—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—while examining the moderating role of debt servicing. Using panel data from 1991 to 2023 sourced from the World Bank and employing robust econometric techniques, we find that remittances significantly reduce CO2 emissions, suggesting that recipient households tend to adopt cleaner energy sources and environmentally friendly lifestyles. In contrast, both external debt and its servicing are linked to increased emissions, indicating that borrowed funds are often directed towards pollution intensive sectors. High debt servicing also limits fiscal space for green investments, exacerbating environmental degradation.

Crucially, the negative and significant interaction between external debt and debt servicing implies a moderating effect—when debt is used primarily for re-payment, less is available for new, emission-heavy infrastructure. Urbanization and financial development also positively and significantly impact CO2 emissions, while EKC also exists in case of these four Asian countries. GDP growth and square of GDP growth have negative and positive effect on CO2 emission respectively.

These findings offer several key implications for South Asian policymakers. First, the negative association between remittances and emissions suggests that these inflows can support environmentally sustainable development. Governments should introduce green remittance programmes and incentives that promote investment in renewable energy and sustainable farming. Second, as external debt and servicing worsen environmental outcomes, borrowing strategies should prioritize green financing tools—such as climate bonds and loans with environmental conditions. Third, the observed interaction effects underscore the need for coordinated fiscal and environmental planning. Ministries of finance, planning and environment must work together to ensure that debt servicing does not limit investments in climate resilience.

In summary, financial flows have complex and interrelated effects on environmental sustainability. While remittances offer opportunities to reduce emissions, the burden of external debt—particularly debt servicing—poses environmental risks. Our findings reinforce the need for integrated policy approaches that align fiscal strategies with environmental goals. Future research should explore these interactions further, including how different financial instruments and institutional settings shape the environmental effects of capital flows in emerging economies.

5.1. Limitations and future research dimensions

This study is conducted in case of the four South Asian countries, hence the results and findings of this study cannot be generalized. Similar type of the study can be conducted in other contexts or regions.

Data availability statement

Data are openly available on depository of the World Bank WDI.

Funding statement

Authors have not obtained any type of funding from any organization.

Competing interest

None of the author of this article have either monetary or non-monetary and explicit or implicit conflict of interest in the publication of this research.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval is not applicable for this manuscript.

Consent to participate

This is not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors are willing to publish this research.