Introduction

Economic inequality has been on the rise over the past decades in many countries around the world (Chancel et al., Reference Chancel, Piketty, Saez and Zucman2022; OECD, 2015). Influential theoretical models suggest that such rises in inequality should lead to growing popular support for redistribution. In the model of Meltzer and Richard (Reference Meltzer and Richard1981), the median voter should – out of economic self‐interest – become more supportive of redistribution when rising inequality leads to a larger gap between the median and the mean income. In models incorporating other‐regarding preferences, individuals’ concerns for the well‐being of others (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016) or their aversion to inequality (Fehr & Schmidt, Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999) should likewise trigger a growing demand for redistribution when inequality increases.

Yet, there is only limited empirical evidence supporting the expectation that increases in income inequality are associated with increases in public demand for redistribution. As a result, many studies understandably depart from the assumption that the expected relationship does not hold. For instance, in a recent review of the literature, Lupu and Pontusson (Reference Lupu, Pontusson, Lupu and Pontusson2023, p. 18) note an ‘apparent stability of demand for redistribution in the face of rising inequality’ as ‘survey data do not seem to lend much, if any, support for the intuitive idea that rising inequality has rendered low‐ and middle‐income citizens more supportive of redistribution’. Weisstanner (Reference Weisstanner2023, p. 551) points to the ‘well‐known’ but ‘unresolved’ ‘paradox that support for redistribution did not increase correspondingly with rising income inequality’. Similarly, Trump (Reference Trump2018, p. 931) sees us ‘returning to the same puzzle: why does inequality not lead to more popular dissatisfaction?’ In trying to make sense of this apparent puzzle, a vast literature asks what might explain the absence of an association between rising inequality and increasing demand for redistribution (e.g., Ahrens, Reference Ahrens2022; Gimpelson & Treisman, Reference Gimpelson and Treisman2018; Lübker, Reference Lübker2007; Mijs, Reference Mijs2021; Trump, Reference Trump2018).

In this research note, we take a step back and ask whether rising income inequality is indeed unrelated to changes in support for redistribution. While the question has been investigated before, the results have been mixed; and while some high‐quality studies (e.g., Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Curtis and Brym2021; Schmidt‐Catran, Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016) have found a link between rising inequality and increased support for redistribution, their results seem to have had only a limited impact upon the received wisdom. Most importantly, existing attempts to study the over‐time association between rising income inequality and changing support for redistribution have been hampered by the limited availability of empirical measures of the public's appetite for redistribution that are comparable across countries and time. We take advantage of the fact that data from the fifth round of the ISSP's Social Inequality module have recently become available. By pooling data from the module's all five rounds (1987, 1992, 1999, 2009, 2019), we are able to study the within‐country association between income inequality and support for redistribution for a reasonably large sample of countries over a period of more than 30 years. Crucially, we thereby cover a longer period than previous studies and one in which inequality increased substantially in many but not all countries.

Leveraging this variation, we obtain robust evidence that when income inequality rises in a country, public support for income redistribution increases. In a second step, we examine the reaction of income groups to rising inequality to adjudicate between different theoretical models of how rising inequality matters. We find that support for redistribution increases across all income groups, with a marginally stronger reaction among the rich. That the reaction is strongest among the rich corroborates the results in Dimick et al. (Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016, Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018) based on a different survey dataset that allows us to cover a longer time period and more countries.

Our study contributes new empirical evidence to the important and widely debated question of how income inequality relates to the public's demand for redistribution. By doing so, we contribute to a vibrant body of research that asks why governments do not redistribute more in the face of mounting inequality. Our findings suggest that insufficient policy responses to rising inequality may be less about absent demand and more about a failure to turn demand into policy.

Theoretical models of inequality and support for redistribution

Political economy's workhorse models expect higher economic inequality to cause greater demand for redistribution. There are, at least, four influential accounts of how rising inequality may lead to more demand for redistribution. First, the Meltzer–Richard model theorizes redistribution within a median voter model in which voters are purely motivated by economic self‐interest (Meltzer & Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). As higher inequality results in a larger gap between the mean and the median income, individuals positioned around and below the median would benefit more from redistribution and, hence, ask the government to deliver respective policies. Second, in the income‐dependent altruism model (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016) individuals’ concerns for overall social welfare trigger an increased demand for redistribution when inequality rises. In this model, rising inequality reduces overall social welfare because, given decreasing marginal returns to income, the rich derive less utility from additional income than the poor. Partly altruistic individuals will therefore demand redistribution to counteract this reduction in social welfare. Third, in the difference aversion model (Fehr & Schmidt, Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999), individuals are inherently averse to inequality. Because of this aversion, they will demand more redistribution when inequality rises (cf. Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018, p. 446). Fourth, individuals might be worried about the ‘externalities of inequality’ (Rueda & Stegmueller, Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016), like increased crime. To counteract such negative consequences of rising inequality, individuals prefer more redistribution.

While these models similarly predict overall demand for redistribution to grow with inequality, they hold divergent implications for how different income groups, particularly the rich, react to rising inequality. According to the common reading of how rising inequality matters for preferences in the Meltzer–Richard model, it is primarily the middle‐income groups, that is, the median voter, who should demand more redistribution when inequality rises (e.g., Andersen & Curtis, Reference Andersen and Curtis2015; Kenworthy & McCall, Reference Kenworthy and McCall2008). When the income of the median income voter falls further below the mean income due to rising inequality, they will benefit more from redistribution and demand more of it. While the same could be said of those with incomes further below the median, the rich have nothing to gain from redistribution, and even more to lose when inequality is high. Thus, their opposition to redistribution should even increase when inequality rises. Models incorporating other‐regarding concerns (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016, Fehr & Schmidt, Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999), in contrast, expect inequality to be positively related to preferences for redistribution across all income groups. The contrast to the Meltzer–Richard model is strongest in the income‐dependent altruism model (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016). Here, it is especially the rich who should demand more redistribution in response to rising inequality. This follows from the model's assumption that income has a diminishing marginal utility. Accordingly, because the rich value additional income less than the poor, they would be more willing to spend that money on redistribution than the less well‐off, and thus be more responsive to increasing inequality.

Previous empirical evidence

Notwithstanding its prominence, the expectation that higher economic inequality causes greater public support for redistribution has received limited empirical support. In the Supporting Information Appendix A, we provide a detailed overview of previous cross‐national studies on this question. To begin with, several studies observe that citizens of unequal countries do not consistently demand more redistribution than citizens living in countries with more balanced income distributions (e.g., Dallinger, Reference Dallinger2010; Lierse, Reference Lierse2019; Lübker, Reference Lübker2007). However, this cross‐sectional association could reflect the impact of stable confounders or be driven by common causes. It is therefore better to identify the effect of inequality from how the public reacts to changes in inequality within countries over time.

Yet, studies that analyze attitudinal change over time also provide only mixed evidence of a positive impact of income inequality on attitudes towards redistribution. While some longitudinal studies do find rises in inequality to be positively associated with increased demand for redistribution (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Curtis and Brym2021; Jæger, Reference Jæger2013; Schmidt‐Catran, Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016), others report insignificant effects (Breznau & Hommerich, Reference Breznau and Hommerich2019; Kenworthy & McCall, Reference Kenworthy and McCall2008; Trump, Reference Trump2023). Methodologically, existing longitudinal studies suffer from two limitations. First, not all studies which have longitudinal data at hand also focus on identifying the effect of income inequality solely from longitudinal within‐country variation in inequality. Second, the coverage of the underlying samples is limited, particularly when it comes to the crucial longitudinal variation. This is true even for some of the broadest and most convincing studies such as Andersen et al. (Reference Andersen, Curtis and Brym2021), based on World Values Survey (WVS) data for 1990–2014, or Schmidt‐Catran (Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016), based on European Social Survey (ESS) data for 2002–2010. Accordingly, we suspect that data limitations go some way in accounting for heterogenous findings.

When it comes to the question of how different income groups respond to rising inequality, the findings are again divided. Studies variously suggest that either the middle class increases its support for redistribution the most (Kevins et al., Reference Kevins, Horn, Jensen and Van Kersbergen2018), that inequality stimulates support especially among the well‐off (Andersen & Curtis, Reference Andersen and Curtis2015; Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018; Finseraas, Reference Finseraas2009), or that income groups change their redistribution preferences in parallel (Gonthier, Reference Gonthier2017; Romero‐Vidal & Van Hauwaert, Reference Romero‐Vidal and Van Hauwaert2022)—with some single‐country studies even reporting that rising inequality decreases support for redistribution in all income groups (Kelly & Enns, Reference Kelly and Enns2010; Luttig, Reference Luttig2013). Other studies approach the interaction from the perspective of the effect of income on support for redistribution: Based on cross‐sectional variation in inequality, they report that income makes less of a difference for redistribution support in high inequality contexts (e.g., Dion & Birchfield, Reference Dion and Birchfield2010; Schmidt‐Catran, Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016). This is consistent with the expectation that high inequality increases redistribution support especially among the rich, thus levelling out differences in redistribution support between the rich and the poor.

In sum, theoretical models agree that rising income inequality should lead to growing public demand for redistribution but hold different expectations regarding the reaction of the rich. Existing empirical research, however, provides neither clear‐cut findings regarding aggregate nor regarding income group‐specific reactions to rising income inequality. A crucial limitation of existing studies, and one that may account for their mixed findings, is that longitudinal within‐country variation, from which the effects of interest can best be identified, has been sparse due to the often short time periods covered.

Data and methods

To contribute new evidence on how attitudes towards redistribution are affected by changes in income inequality (across income groups), we use pooled data from the ISSP Social Inequality module. With the recent addition of the latest round, we can now draw on five waves, spanning the years 1987 to 2019 (ISSP, 1989, 1994, 2002, 2017, 2022). Covering these last three decades, the pooled data allow us to look at a longer time period than previous studies and one in which inequality rose in many countries. Overall, 35 countries, most of them established liberal democracies, have been included at least twice in the ISSP Social Inequality survey.

Our (main) dependent variable support for redistribution asks for agreement with the statement that ‘It is the responsibility of the government to reduce the differences in income between people with high incomes and those with low incomes’ on a five‐point scale. We recoded the item to range from 0 to 4. This item has been most commonly used to measure people's support for redistribution in previous studies (see Supporting Information Appendix A). As shown by the histograms in Figure C1 of the Supporting Information Appendix, most people agree with the statement: Overall, only 16 per cent (strongly) disagree with it, 15 per cent neither disagree nor agree, and 69 per cent (strongly) agree with it. Mean redistribution support varies from 1.7 (USA in 2010) to 3.6 (Russia in 2019) across country‐years observed, with an overall mean of 2.8 and a standard deviation of 0.40. The four country‐years observed for the US constitute the only cases (out of 123) in which mean redistribution is below the midpoint of the scale (= 2).

Following common practice (see Supporting Information Appendix A), we measure income inequality through the Gini coefficient of disposable (i.e., post‐taxes, post‐transfers) household incomes. We sourced the Gini data from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) (Solt, Reference Solt2020). These data combine Ginis from a variety of sources into one estimate per country‐year based on a Bayesian latent variable model. To take the resulting uncertainty in the estimated Ginis into account, we use the dataset containing 100 draws from the posterior distribution and estimate our models using multiple imputation, as recommended in Solt (Reference Solt2020). We merged the Gini data, and other covariates mentioned below, to the year in which the ISSP survey actually took place in a given country, which can be 1 or 2 years later/earlier than the official year of the ISSP wave. While there are alternatives, the Gini coefficient is the most widespread and publicized summary measure of income inequality. Like previous studies, we look at disposable income, rather than market income, as citizens should care about the degree of inequality that obtains after governmental taxes and transfers. The Gini has a theoretical range from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximum inequality). Empirically, its estimated posterior mean varies from 0.19 (Slovakia in 1992) to 0.63 (South Africa in 2009) in our sample.

We analyze the association between rising inequality and support for redistribution in two sets of models, both of which identify the effect of inequality solely from within‐country variation over time. First, we run first‐difference regressions on aggregate‐level data, regressing the difference in mean support for redistribution between two consecutive ISSP waves on the difference in the Gini computed over the same time period, with robust standard errors clustered by country. We believe this simple and transparent model is most adequate for probing how the public overall reacts to increases, or decreases, in income inequality.

Second, we turn to multilevel models with individuals nested in country‐years to assess the reaction to rising inequality across income groups. To this end, we code respondents into income quintiles based on their equivalized household incomeFootnote 1 and include random slopes for the income quintiles as well as cross‐level interactions between income quintiles and the Gini.Footnote 2 To identify the effects of interest solely from within‐country variation in the Gini over time, we include country dummies, limiting the analysis to countries covered at least twice in the Social Inequality module. To ease computation, interpretation, and comparability to the aggregate‐level results, we estimate linear models. Further covariates and robustness checks are discussed below.

Aggregate‐level results

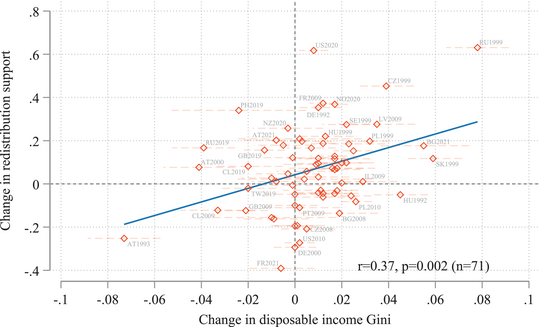

We first present a scatterplot plotting changes in redistribution support against changes in the Gini in Figure 1.Footnote 3 Across the 71 observations, there is a clear tendency of redistribution support to increase when inequality rises, and vice versa.

Figure 1. Changes in income inequality versus changes in support for redistribution

Note: The y‐axis shows the first difference in mean redistribution support between two consecutive ISSP waves. The x‐axis shows the first difference in the (posterior mean of the) Gini coefficient measured over the corresponding time period. The spikes show the uncertainty around the estimated difference in the Ginis (‐/+ 1 standard error).

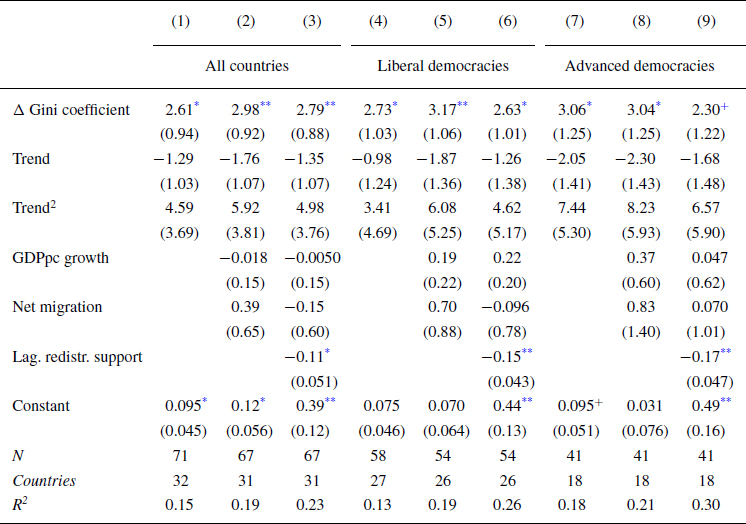

Turning to our main aggregate‐level regressions, we present results for three specifications in Table 1: A specification controlling for time trends, a specification adding two substantive controls and a specification further adding the lagged level of redistribution support from the previous Social Inequality survey to account for potential ceiling effects. The substantive controls are: The growth rate of real GDP per capita, as redistribution support has been argued to decrease when a country becomes richer (Dion & Birchfield, Reference Dion and Birchfield2010); and net migration as a share of the country's population, as redistribution support has been suggested to decrease with the arrival of immigrants (Brady & Finnigan, Reference Brady and Finnigan2014). The latter two variables are sourced from the World Bank (2023a, b) and measured over the time period corresponding to the first differences in redistribution support. We estimated these specifications across three samples: The full sample with all available observations, a sample limited to all country–years classified as liberal democracies by Varieties of Democracy (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann and Neundorf2023), and a sample limited to those countries often considered to constitute the group of ‘advanced’ democracies.Footnote 4 While we see theoretical reasons for why the relationship might be different for less democratic countries due to, for example, restrictions in media freedoms that prevent the public from forming accurate perceptions of inequality, the distinction between liberal and advanced democracies is just introduced to facilitate comparison to previous studies with similarly limited samples.

Table 1. First‐difference regressions of support for redistribution

Note: OLS regressions regressing the first difference in mean redistribution support between two consecutive ISSP waves on the difference in the Gini coefficient of disposable household income computed over the corresponding period. Estimation based on multiple imputation to take the uncertainty in the estimated Ginis into account. Trend starts at 0 in 1992 (the first year observed) and increases by 0.01 every year. Standard errors (clustered by country) in parentheses; + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Across all nine models, we obtain a statistically significant coefficient for the change in the Gini coefficient of disposable household income.Footnote 5 While the effect becomes less precisely estimated in the smaller samples, remaining only significant with p < 0.10 in model 9 for the advanced democracies, effect sizes are similar across specifications and samples. The coefficients indicate substantively meaningful effects. According to model 6, for example, a large increase in the Gini of 0.055, like the one that took place in Bulgaria between 2008 and 2021 (posterior mean estimates of the Gini), is associated with an increase in mean redistribution support by about 0.13. This corresponds to about two‐thirds of the standard deviation (= 0.19) in the first difference of mean redistribution support.

We carried out several additional tests, listed in Supporting Information Appendix D, to probe the robustness of our main result that rising inequality in disposable income is associated with an increased demand for redistribution. First, we get similar results when simply using the posterior means of the Ginis, which also hold for wild cluster bootstrapping (Table D2). Second, we introduce first differences in the inflation rate, unemployment rate and tax revenue as additional substantive control variables, arriving at similar results (Table D3). Third, we also obtain largely similar results when replicating Table 1 with the lagged level of the Gini as an additional control (Table D4), despite its substantive correlation with the change in the Gini (r = −0.48). Fourth, we re‐estimated model 3 leaving out individual ISSP waves (Figure D1). The coefficients are consistent with one another, but we cannot reject the null hypothesis when excluding ISSP 1999; and when dropping the latest wave from 2019, we arrive at a somewhat larger effect. This suggests that the association is not driven by any particular wave, but that the ability to estimate the effect precisely increases with the number of waves covered. The coefficient remains highly stable when excluding individual countries from the specification of model 3 in turn (Figure D2). Fifth, we ran country fixed effects (FE) models regressing the level of redistribution support on the level of inequality (and control variables measured in levels as well). Like our main model, the country FE model focuses solely on within‐country variation – while not linking changes in redistribution support to changes in inequality over the corresponding period as directly. The results accord with the evidence from the first‐difference regressions, though the effect of the Gini is a bit weaker and does not reach statistical significance with the smallest sample (Table D5).Footnote 6

In addition, we conducted two supplementary analyses. First, we formally tested whether the effect of the Gini differs across groups of countries by interacting the Gini with a variable distinguishing between advanced democracies, Eastern European countries, and the remaining countries. We cannot reject the null hypothesis that the effect is the same across these three groups of countries (Table D6).

Second, we considered two measures of income inequality before taxes and transfers – the Gini coefficient based on market incomes (Solt, Reference Solt2020) and the pre‐tax income share that goes to the top 10 per cent of income earners from the World Inequality Database (Alvaredo et al., Reference Alvaredo, Atkinson, Piketty and Saez2023) – and re‐ran models 1 to 9. While all coefficients are positive, only some are statistically significant (Tables D7 and D8). That these results are weaker than for inequality based on disposable household incomes suggests that citizens ultimately care about the amount of inequality that accrues after governmental taxes and transfers. When we consider both the change in market Ginis and in the amount of redistribution (i.e., the difference between disposable and market Ginis), evidence that increases in market Ginis are associated with increased demand for redistribution becomes more consistent (Table D9). At the same time, we find that demand for redistribution tends to increase when governmental redistribution has decreased – in line with the idea of policy preferences being ‘thermostatic’ (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien1995). Overall, our results thus suggest that demand for redistribution goes up when inequality in disposable income has increased, no matter whether this increase is a result of rising market inequality or of a decrease in redistributive effort by the state.

Multilevel results

In the multilevel analysis, we continued to estimate separate models for the full sample and the liberal democracies. In addition to the disposable income Gini, respondent's income quintile and their interaction, the models control for gender, age group and education. We additionally include an interaction between education and the Gini, alongside random slopes for education. We thereby aim to distinguish variation in the effect of rising inequality that is due to income from variation that may result from differences in information levels as proxied for by education. At the macro level, we control for the time trend (linear and squared) and the country dummies, but we do not include the further substantive controls from above, as they turned out to be insignificant and contain missing values.

Full regression tables are displayed in Table E1 of the Supporting Information Appendix, including, for comparison, models without the cross‐level interactions. In both samples, the Gini coefficient is positively associated with support for redistribution, and the interactions indicate that this association is statistically significantly larger for the top quintile as compared to the lowest quintile. The effect of the Gini on support for redistribution also increases with an individual's level of education, which may reflect that higher‐educated individuals are on average better informed about changes in inequality.

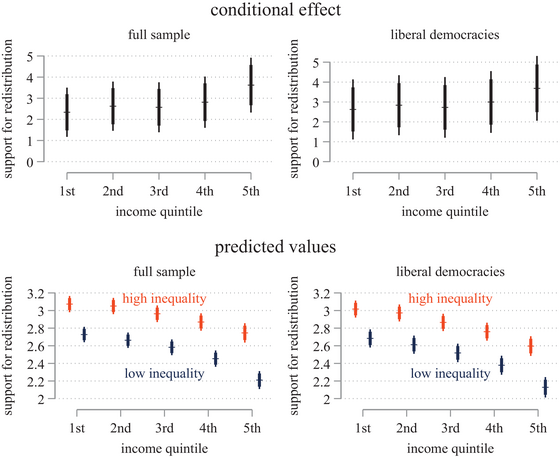

In the upper part of Figure 2, we plot the marginal effect of the Gini conditional on income. The first thing to note is that the positive effect of rising inequality on support for redistribution holds for all income groups. At the same time, the effect tends to be somewhat larger for the top 20 per cent of income earners than for the rest and especially compared to the bottom 20 per cent. The lower part of Figure 2 shows predicted values across income quintiles for a low and high inequality scenario. Predicted values of redistribution support are higher in the high inequality scenario for all income groups, and the increase is marginally stronger among the rich. This also results in the differences in redistribution support across income quintiles narrowing a bit when inequality rises. Still, there is a sizable income gradient even when inequality is high.

Figure 2. Inequality, income quintile and support for redistribution

Note: Upper panels: Conditional marginal effects of the Gini coefficient on support for redistribution at different values of income quintile. Lower panels: Predicted values for different values of Gini coefficient and income quintile. Estimations are based on the multilevel models 3 and 6 from Table E1 in the Supporting Information Appendix. High inequality corresponds to the 90th percentile value (= 0.393/0.372) observed in the estimation sample, and low inequality corresponds to the 10th percentile value (= 0.245).

Overall, these results are clearly inconsistent with the view inspired by the Meltzer–Richard model that rising inequality would increase demand for redistribution only among the middle and the poor; rather it does so across all income groups. If anything, these results accord with the income‐dependent altruism model in that the rich are a bit more sensitive to increases in inequality – whereas redistribution support among the poor is already relatively high when inequality is low and does not increase as much when inequality rises.Footnote 7

Results for a broader measure of support for redistribution

Finally, we repeated the analysis for an alternative outcome variable: A composite mean index of individuals’ support for redistribution, combining the redistribution item from above with an item on whether income differences are too large and one on whether the rich should pay higher taxes than the poor (see Supporting Information Appendix F). These three items have all been used in previous studies (see Supporting Information Appendix A) and they load well on a single scale (see Table F1). Aggregate‐level changes in these variables correlate strongly with one another, and they all correlate positively with first differences in the disposable income Gini (Table F2). For the composite mean index, we obtain results similar to those presented above for both the aggregate‐level (Figure F1 and Table F3) as well as the multilevel analysis (Table F4 and Figure F2).

Conclusion

In this research note, we have reconsidered the link between growing income inequality and redistribution support. Utilizing all of the now five rounds of the ISSP's Social Inequality module, we were able to rely on cross‐national public opinion data covering a longer time period than previous studies. Our results are in line with the prediction from standard political economy models that the public grows more supportive of redistribution when inequality increases. Notwithstanding the mixed evidence from previous research overall, we thereby confirm the conclusion from some cross‐national studies which also focused on the within‐country effects of rising inequality but utilized different data sources and covered a shorter time period – such as Schmidt–Catran's (Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016) analysis of ESS data or Andersen et al.’s (Reference Andersen, Curtis and Brym2021) examination of WVS data. With more and more data having become available to render robust longitudinal studies feasible, evidence thus appears to accumulate that rising inequality is indeed associated with growing demand for redistribution.

Additionally, we have studied how income groups respond to inequality. We find that rising inequality matters for redistribution support in all income groups, and even a bit more among high‐income earners. Again, despite mixed evidence overall, these results are in line with the cross‐national studies by Dimick et al. (Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018) and Schmidt‐Catran (Reference Schmidt‐Catran2016) based on ESS data for 2002–2013 and 2002–2010, respectively and Andersen and Curtis (Reference Andersen and Curtis2015) based on WVS data for 1990 to 2005. Theoretically, while clearly inconsistent with the canonical Meltzer–Richard model, the results accord with the income‐dependent altruism model (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016). More broadly, they are in line with the notion that while poorer individuals have good reasons to always support redistribution out of material self‐interest, support for redistribution among the rich is more elastic and thus responds more to the broader consequences of increasing inequality, be it on overall social welfare (Dimick et al., Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018) or in terms of negative externalities like crime (Rueda & Stegmueller, Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016).

Given the growing evidence of rising inequality being associated with increasing demand for redistribution, future research should intensify its efforts to discover why political systems apparently fail to respond with redistributive policies that overcome the rise of inequality that took place in many countries over the past decades. In closing, we highlight three potential explanations (also see: Lupu & Pontusson, Reference Lupu, Pontusson, Lupu and Pontusson2023). First, it might be the case that while most citizens share an abstract preference for redistribution in response to rising inequality, this does not necessarily coincide with supporting specific policy changes that would lead to a reduction in inequality (cf. Margalit & Raviv, Reference Margalit and Raviv2024). One possibility is that citizens are ill‐informed when it comes to the consequences of specific redistributive policy changes, like tax reforms (Bartels, Reference Bartels2005). Second, within an increasingly multidimensional political space (Hillen & Steiner, Reference Hillen and Steiner2020; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), supporting redistribution does not necessarily result in voting for parties that support redistribution. When non‐economic issues are salient, pro‐redistribution majorities that exist among voters may not be reproduced at the party level as lower‐income voters vote for right‐wing parties based on their cultural preferences (Gidron, Reference Gidron2022; Hillen, Reference Hillen2023; Stegmueller, Reference Stegmueller2013). A third explanation points to the role of political inequality, and specifically the finding that policy outcomes are systematically closer to the preferences of the rich than to those of the poor (Elsässer & Schäfer, Reference Elsässer and Schäfer2023). Somewhat puzzlingly though, we find that support for redistribution increases in response to rising inequality even among the well‐off – though possibly not the few super‐rich that are hard to survey (Hecht, Reference Hecht2022), and notwithstanding that the well‐off remain less supportive of redistribution than the poor even in high‐inequality contexts. A related mechanism then might be that legislators are overall less in favour of redistribution than citizens (Helfer et al., Reference Helfer, Giger and Breunig2023; Lupu & Warner, Reference Lupu and Warner2022). In any case, our findings indicate that to solve the puzzle of why redistribution does not keep pace with mounting inequality, we need to look not only at the demand but at the supply side as well and consider how citizens’ preferences (do not) get translated into policies.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented in research seminars at JGU Mainz. We are grateful for the constructive feedback we received from the participants. We would also like to thank EJPR's three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Larissa Henkst provided excellent research assistance.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability statement

Reproduction materials for this article are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/T5F8RR

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: