The Confucius Institute initiative – one of China's key state-sponsored channels to promote Chinese language and culture overseas – has recently come under increasing scrutiny in the West. In the United States, 45 Confucius Institutes (CIs) have been shut down in recent years.Footnote 1 In August 2020, the US Department of State designated the Confucius Institute US Center that oversees all CIs and Confucius Classrooms (CCs) in the US as a foreign mission of the People's Republic of China (PRC).Footnote 2 In March 2021, the US Senate passed a new measure which would cut federal funding for universities and colleges that don't establish full oversight and authority over CIs.Footnote 3 CIs now face similar resistance in parts of Europe and Australia.Footnote 4 What has been presented as a benign mission of cultural promotion by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese state is increasingly interpreted by some Western audiences as a hard-edged ideological campaign that aims to dominate rather than entice. Partly in response to these negative developments, on 5 July 2020, the Ministry of Education of China announced the establishment of the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF) – a new organization in charge of CIs and CCs.Footnote 5 Western politicians, however, have reacted with cynicism. “And so they become GONGOs, right – government-organized nongovernmental organizations. That's so communist,” remarked David Stilwell, the assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs in August 2020.Footnote 6

These policy narratives about CIs echo a wider scholarly consensus about China's soft power deficit. According to some scholars, China's large-scale investment into soft power (estimates put it at US$10 billion per year) at best translates into “partial power.”Footnote 7 China's image promotion, studies suggest, is hindered by its defensive approach, top-down communication practices and autocratic political system. Scholars depict China's soft power strategy as reactive, centred on reducing Western dominance in “discourse power” (huayu quan 话语权) – a term widely used by Chinese policymakers.Footnote 8 Others point to China's “transmission” view of communication – aimed primarily at message delivery rather than at interactive communication.Footnote 9 Others argue that China's autocratic political system and coercive strategies diminish its moral appeal.Footnote 10

The majority of scholarly assessments about China's soft power, however, primarily engage with Western contexts, where China faces the harshest obstacles. Moreover, the current analyses tend to adopt a top-down approach to examining China's soft power initiatives, emphasizing political discourses, policies and investments, but pay less attention to the implementation of these initiatives in different cultural contexts. As a result, we are left with a narrow grasp of China's global image work and, as such, of its approach towards external credibility building in the Xi era.

This study is the first to examine the most controversial of China's soft power exports – the CIs – within a political and economic context that appears as especially predisposed for China's effective public outreach – Ethiopia. Ethiopia is the second largest recipient of Chinese loans in Africa,Footnote 11 one of China's closest diplomatic partners on the continentFootnote 12 and a long-time student of China's strategies of economic development.Footnote 13 Through grounded in in-country fieldwork, this article presents the workings of China's CIs and CCs by explaining how they are marketed and received by key stakeholders. The Ethiopia case demonstrates that in the context of significant economic dependency and limited external competition, the practical offerings associated with CIs and CCs appeal to the major co-participants in these initiatives, including high-level university administrators and co-directors, Chinese language students, as well as Chinese directors and “teacher volunteers” (zhongwen jiaoshi zhiyuanzhe 中文教师志愿者) (hereafter volunteers; although “teacher volunteer” is the term used by the CIs and CCs, as will be discussed below, they do receive remuneration in the form of a stipend). At the same time, the Ethiopia case shows that even in a highly favourable context, these initiatives are likely to face sustainability challenges, as the “desire” for China is embedded in its persistent and expansive positioning of itself as an economic opportunity, and the intent to work in Ethiopia (for the teachers) is contingent upon Ethiopia remaining a safe and stable destination.

Confucius Institutes: Grand Ambitions, Ambivalent Results

The scholarship on CIs tends to adopt Joseph Nye's conceptualization of soft powerFootnote 14 to evaluate whether these institutesFootnote 15 contribute to or hinder China's quest for soft power. Namely, scholars examine whether the expansion of CIs increases the popularity of Chinese culture, independently from China's coercive and monetary engagements. Scholarly evaluations of these institutes, from Australia to Europe to parts of Africa, underscore a disconnect between China's grand ambitions and their ambivalent effects.

The limitations highlighted in the existing works are both ideological and practical. As for the former, some scholars point to the perceived coerciveness,Footnote 16 often manifested in the self-censorship of CI participants.Footnote 17 The expansion of these initiatives, especially in the West, some argue, elicits a “China threat” narrative rather than a welcoming embrace of Chinese culture.Footnote 18 The political concerns for (and subsequent resistance to) CIs are documented in diverse case studies, from VietnamFootnote 19 and FinlandFootnote 20 to KenyaFootnote 21 and South Africa.Footnote 22 Some scholars further unpack these political fears by suggesting that, at least in Western contexts, they are rooted as much in inherent ideological “othering” of China as in lived realities of political interference.Footnote 23

As for practical implementation, studies point to the problematic execution of, and financial challenges faced by, CIs. Scholars highlight the shortage of experienced teachers in the case of Australia,Footnote 24 as well as limited international cultural training provided to new teacher recruits dispatched to Nairobi.Footnote 25 Others point to an emphasis on the global expansion of CIs rather than on the quality of student–teacher interaction, as documented in the case of CIs in South Africa.Footnote 26 The long-term financial vulnerability of CIs is noted as another operational limitation.Footnote 27

Overall, with a few exceptions, the existing studies treat CI expansion as an ambitious manifestation of China's soft power push but emphasize the persistent challenges.Footnote 28 Even the most optimistic assessments conclude on a cautionary note. One author suggests that CIs’ effectiveness should be judged by China's growing international visibility in the higher education sector, rather than by winning the hearts and minds of foreigners, thus limiting China's ambition to a narrower pursuit.Footnote 29 Another author praises the joint-venture system of CI operations but notes that China's political image would overshadow the potential success of this institutional design.Footnote 30

The current literature on CIs offers important insights about their political and operational constraints, but its scope is theoretically and empirically limited. As for the former, most studies analyse how CIs measure up to Nye's idea of soft power and explain why in most cases they fail to do so, emphasizing China's lack of universally attractive political values as a key factor. A critical reading of Nye would acknowledge his conceptualization as rooted in the American context, with American values, such as freedom and democracy, associated with universal attractiveness. Echoing other scholars who advocate building theory from the Global South, a critical inquiry into Chinese soft power should analyse Chinese efforts on their own terms rather than as “negative imprints of ‘the West’.”Footnote 31 The ethnographic approach is especially apt for such inquiry as it helps us to grasp the elusive effects or implications of the CI initiative by explaining its significance from the perspective of individuals and groups that directly take part in shaping these projects. Detailed observations and interviews also help to illuminate potential contradictions in Chinese soft power implementation, which complicate the binary narratives of its success or failure.

The current studies of China's soft power, including those on CIs, however, tend to draw primarily on secondary sources on Chinese policies and depict CIs as monolithic tools of the CCP, while telling us little about how CIs actually operate. The empirical studies thus far tend to focus on a selective subcategory of participants, such as students (as in the case of Nairobi) or administrators (as in the cases of South Africa and Germany). One important exception is Hubbert's recent ethnographic study of CIs in the US,Footnote 32 but her work primarily analyses how Americans perceive CIs and “conceptualize global hierarchies,” rather with the workings of CIs per se.Footnote 33 The cases analysed in the existing literature also tend to be situated in “difficult” contexts for success, including the US, Western Europe and Australia. Of the African countries analysed, Kenya and South Africa have relatively long histories of Western styles of schooling and educational exchange with the West. How CIs operate in contexts where pro-Western worldviews are less apparent and where more unequal economic relations with China create a more favourable playing field for CIs has not been sufficiently addressed in the literature.

This study departs from the existing scholarship by focusing on the attraction of CIs for different participants in a context that is more receptive to China's soft power outreach. The case study of Ethiopia demonstrates that China's conception and implementation of soft power is distinct from Nye's widely adopted version in deliberately fusing tangible or practical rewards with cultural initiatives. The CIs and the smaller-scale CCs represent an approach to soft power that I describe as “pragmatic enticement,” with different actors attempting to reinterpret and take advantage of Chinese culture for institutional, professional and personal advancement. The practical elements of China's soft power, especially its economic enticements, while more pronounced in Ethiopia, are not unique.Footnote 34 However, unlike Western liberal contexts in which China's practical enticements don't appear to extensively transform the sentiments towards China amongst the participants,Footnote 35 this study shows that in contexts of significant economic and political dependency on China the spectacle of economic development that characterizes CIs and CCs holds a wider emotional appeal or attraction, at least in the short term. However, in the long term, the entanglement of practical and cultural domains challenges the sustainability of these initiatives.

Ethiopia Case Study: In the Shadow of a “Model Relationship”

Ethiopia's close economic, political and diplomatic ties with China make it a path-breaking case for examining the potential and the limitations of China's soft power outreach in Africa and the Global South. The Ethiopia–China relationship has been referred to as one of the “model relationships” of South–South collaboration by Ethiopian officials and the Chinese press.Footnote 36 On the economic front, since 2000, Ethiopia has accrued US$12.1 billion in Chinese loans (making it the second largest loan recipient on the continent),Footnote 37 received US$4 billion in Chinese investmentsFootnote 38 and managed to attract nearly 700 Chinese companies to operate in Ethiopia.Footnote 39 The Chinese media also link Ethiopia's rapid GDP growth to successful learning from China.Footnote 40 Ideologically, the revolutionary democracy and developmental state orientation of Ethiopia's governing coalition, the EPRDF (which became the Prosperity Party in 2019), has fuelled bilateral affinity, with party-to-party relations flourishing in the past two decades.Footnote 41

As part of strengthening and expanding of its relations with Ethiopia, China has embarked on an extensive charm offensive, including large-scale training programmes for societal elites and media outreach and higher education initiatives. This study focuses on the field of education as CI and CC initiatives engage Ethiopian youth, and thereby have immediate implications for the future of China–Ethiopia relations. The recent history of Chinese cultural centres in Ethiopia dates back to 2010 when the first CI was inaugurated at the Ethio-China Polytechnic College in Addis Ababa,Footnote 42 enrolling over 250 students into compulsory Mandarin classes, followed by the launch of a CI at Addis Ababa University (AAU) in 2013. A few years later, CCs were opened at universities in Hawassa, Mekelle, Bahir Dar, Arsi and Jimma. All, except the CC in Jimma which is overseen by the CI at AAU, are coordinated by the head of the CI at the Federal Technical and Vocational Education and Training Institute (FTVETI). The initiatives at AAU, Hawassa, Mekelle and Arsi have grown into full-scale Chinese language bachelor's degree programmes, while others offer certificate programmes. Chinese language is also now being taught at the Adama Boarding School in the Oromia region, with two volunteers sent from the CI at AAU. It is important to note that while officially Ethiopian deans co-direct CIs and CCs, unofficially, most of the work is handled by the Chinese directors, including curricula planning and events organizing.

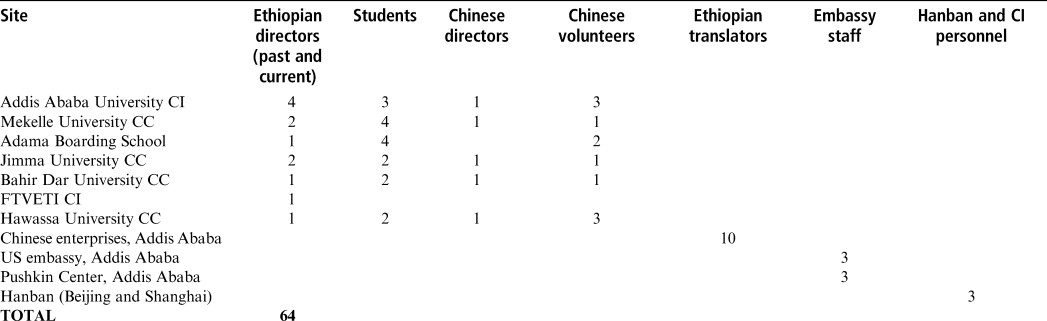

Considering the growing sensitivity surrounding CIs in the West, access to these spaces in Ethiopia was uneven and at times challenging. The author managed to visit and interact with different stakeholders at most of the CCs and at the CI in AAU (see Table 1 for details on the interviews), including observations of Chinese language classes, interviews with Chinese directors and volunteers, past and current deans that co-direct the CIs and CCs, as well as students and graduates of Chinese language programmes, including Chinese scholarship recipients and former students who are now translators in Chinese enterprises. During a trip to Beijing in the summer of 2019, the author has also visited and interviewed representatives of Office of Chinese Language Council International (the former CI headquarters, colloquially referred to as Hanban; its name was changed in July 2020 to the Center for Language Education and Cooperation, or CLEC). The article draws on 64 interviews conducted over a period of eight months across Ethiopia in April–May 2018 and February–May 2019; and in Beijing in the summer of 2019.Footnote 43

Table 1: Distribution of Interviewees

To University Administrators: The Varied Inducements behind CI Initiation

The initiation of CI/CC programmes has involved a series of inducements from the Chinese side, including a free trip to China for university leaders to introduce the CI project and China's economic accomplishments, as well as the marketing of the study of Chinese as lucrative for future graduates. The official launch of CI/CC programmes has been accompanied by an invitation for top administrators, including university presidents and humanities deans who co-manage CIs and CCs, to visit China. These trips have included an induction training, introducing the CI project as a channel for internationalizing Ethiopia's education system and partaking in economic modernization. Interviews with trip participants reveal that the CI conference, held at the Hanban headquarters,Footnote 44 exposed them to the global scope of the initiative. The former humanities dean at Mekelle University, who launched the university's CC programme, shared that while in China he realized that Ethiopia was “already late into the game” when it came to studying the Chinese language.Footnote 45 At this event, he learned that Kenya was introducing Chinese into its secondary schools, and that Britain had 30 CIs. After returning to Ethiopia, he immediately submitted a 12-page application to host a CC programme. “Whether you like it or not, we need to be connected,” he remarked.Footnote 46 A former dean and co-director of a CI at AAU, who attended a similar event, was left impressed with “how serious the Chinese are about promoting their language,” noting the vast international expansion of their activities, something he remarked on as “a good thing.”Footnote 47 The annual Global Confucius Institute Conference (changed to the Confucius Institute Forum in 2020) framed participation in CI/CC initiatives as akin to globalization – something initially alien but unavoidable.

The university administrators were also invited to partake in and consume China's economic modernity on a vivid tour of China's economic achievements, from modern infrastructure to technological advancements. One Ethiopian participant was left in awe with Chinese cities, comparing Shanghai to New York, and noting that “even the smallest Chinese cities are enormous, and have everything.”Footnote 48 In describing Chinese urbanization, he used a cooking metaphor: “It's as if they closed the door and were cooking quietly and then they opened the door for the world to witness the feast.”Footnote 49 Many participants also described China as “aspirational,” attributing its success to hard work.

The trips sparked an emotional affinity towards China for university administrators, but the appeal of CIs/CCs was further cemented by the practical offerings embedded in these initiatives. Namely, whereas the launch of the first two major CIs was likely a product of a mix of factors, including diplomatic allegiances, the subsequent establishment of CCs, and especially the introduction of a Chinese language degree programme at four Ethiopian universities, had to do with rewards presented to, and envisioned by, the university administrators. For instance, the rationale for establishing a bachelor's degree programme in Chinese language at Hawassa University, found in a Chinese language degree programme curriculum designed by the CI, starts with the following statement:

With the great increase of Chinese economy and growth in international trade and business, the need in Chinese language speakers is becoming greater and greater. China and Ethiopia have a long and traditional friendship. The communication in economy, culture and other fields between [the] two countries has been enhanced in recent years with a large number of Chinese companies coming into Ethiopia to invest and research, which necessitates badly for more Ethiopian or local translators.Footnote 50

This promotion of the Chinese language as grounded in employment potential (albeit wrapped in references to cultural closeness) reflects the CI's localization efforts that were encouraged by Hanban. A former director of a CI in Botswana, currently a faculty member at Shanghai Normal University, shared that Hanban endorses “CIs with local characteristics.” In practice, this means aggressive adaptation to local contexts. “If there is a need for agricultural development, we can try to help with that, if there are many Chinese enterprises, we would emphasize translation,” he explained.Footnote 51 King's insightful analysis of CIs similarly underscored responsiveness to local needs as a feature of CIs’ operations.Footnote 52 In this case, the presentation of Chinese language study as complementary to China's economic activities in Ethiopia and as advantageous for university students spoke to the expectations of Ethiopian university officials. The deans of Ethiopia's top universities see the introduction of Chinese language and culture primarily in instrumental terms – as a key to better job prospects for their graduates who often struggle to secure employment.Footnote 53 Some Ethiopian administrators (co-directors of CIs and CCs) even conducted their own studies into employment prospects. The former dean at AAU shared that while conducting his inquiry he found that Chinese language translators in Ethiopia get paid more than associate professors at his university.Footnote 54 Other administrators noted that the first batch of Chinese language graduates had managed to secure nearly full employment. The positive data about recent graduates’ employment prospects influenced other Ethiopian institutions to participate. The president of Jimma University submitted his application for a CC programme after visiting the CI at AAU.Footnote 55 The principal of the Adama Boarding School, inspired by university-level initiatives, launched a two-year Chinese language course to make his students more competitive for Chinese scholarships and jobs at Chinese companies.Footnote 56

Other than being marketed to administrators as conduits to employment, CIs and CCs have been presented as financially advantageous. Up until 2020, the majority of funding for CIs had come from the Chinese side, including provision of teaching materials and payment of Chinese directors’ and volunteers’ salaries. Institutions on the Ethiopian side have provided classroom space and housing for teachers (in buildings already owned by the institutions, and which therefore don't constitute an additional cost). At the 2020 Confucius Institute Forum, the chairman of the CIEF, Yang Wei 杨卫, announced that the foundation would raise money for CIs and pay for training of CI leaders and marketing materials. Partner institutions are to provide the necessary facilities and help co-fundraise.Footnote 57 How the proportions of co-funding will play out in practice is not yet clear, but there have been no publicly announced budget-related closures of CIs and CCs in Ethiopia, or in Africa as a whole, in 2020–2022. Chinese language classes on Ethiopian campuses are also free for all members of the academic community and are largely managed by the Chinese side – requiring limited effort from the Ethiopian co-directors and staff. Up until 2020, the co-directors also received a modest financial bonus from the Chinese side (an average of US$39 per month). Taking into account several of the factors outlined above (tours of China for CI/CC directors, the promotion of Chinese as a lucrative language and the bearing of the majority of the costs in establishing and sustaining the programmes), the introduction of CIs and CCs is an option most university administrators have readily embraced thus far.

For the Students: Chinese Language Wrapped in Material Rewards

Convincing Ethiopian administrators to launch a CI or a CC initiative is a critical starting point, but attracting students is important in justifying and expanding the programmes. The success metric as articulated by Hanban has included hosting a large number of events, receiving media coverage and launching a Chinese degree programme.Footnote 58 Under the new leadership of the CIEF, these metrics are unlikely to change, as the emphasis is still placed on showcasing traditional cultureFootnote 59 and on localizing Chinese language teaching by embedding it more into local education institutions.Footnote 60 The third ambition, launching a degree programme, has been frequently brought up as a challenge by Chinese directors – something they have to work up to by attracting more students over time. This section demonstrates how the marketing of Chinese language study to students is wrapped up with material rewards. CIs motivate students to join and to remain in the programme by presenting China as a unique experience or as accessible to Mandarin speakers, as well as by selling Chinese as a ticket to the Chinese job market in Ethiopia.

China as an experience

The most immediate attraction of the Mandarin that is presented to CI/CC students is the possibility of securing a scholarship to study in China. “Study in China with a scholarship,” “Join a summer camp to visit China,” “Join a Chinese Bridge competition!” – these are some of the slogans found on advertising banners for CIs and CCs in Ethiopia. The summer camp was accessible to a few top students from each CI programme in the country, whereas a scholarship to spend a semester or a year studying Chinese in China was available to anyone scoring at the intermediate level (level 3) or above on the HSK Chinese proficiency test.Footnote 61

The promotion of Chinese language as a real-life experience resonated with the students surveyed in this study. Asked why they chose to study Chinese, first-year students in Mekelle University said: “I like China! I want to go to China!” When asked why or what about Chinese culture intrigued them, most were unable to go into detail, but they were eager to get a scholarship. Some students explained that they were motivated by the sheer monetary value that these scholarships represented. “My teacher translated the costs of the summer camp trip into birr, and it turned into a huge sum – more than one thousand dollars! This made me really excited to go for it!” shared a graduate from the Hawassa CI programme who ended up winning a place at the summer camp.Footnote 62 Teachers also at times offered to wave the fee for the HSK exam required for the scholarship application, if students got a high score. “Every little bit counts for us, even 300 birr was a big motivation to study harder,” shared another former student from Hawassa.Footnote 63 The material incentives were also helpful in appeasing the worried parents of students. At the Adama Boarding School in the Oromia region, where Chinese has been introduced as a required subject, parents were at first dismayed by the idea of their children learning Chinese, according to the school vice-principal, as they didn't initially envision any practical benefit for learning such a difficult language. “Once they heard about the summer camp possibility and other scholarships in China, however, they were put at ease,” shared the principal, who himself was considering taking Chinese classes.Footnote 64 Of course, the parents’ agreement to allow their children to learn Mandarin does not necessarily translate into overall support for this endeavour. In routine conversations with university faculty and lay citizens about Chinese language learning, China's ability to teach its own language and culture in Ethiopia was also at times associated with wielding power or attempting to shape the perceptions of the Ethiopian public. Many, however, still saw it as beneficial if it yielded direct and practical gains to students and educational institutions.

Other than complaining about the overly intensive study schedule and the extreme weather, most interviewees spoke of their trips to China with fondness, describing the exotic sites and hospitality of Chinese people. For these students, China was the first and the biggest adventure in their lives – their first international flight and the first experience outside of Ethiopia. In contrast to Hubbert's account of American students in China associating intensive and over-planned trips with propaganda and a lack of authenticity, Ethiopian students, like their deans, saw it as their escape into the “global.” China, for them, was primarily an adventure into a more developed world rather than an encounter with autocracy. Chinese teachers in Ethiopia, who stay in touch with their students over WeChat, shared that the students were “generally satisfied.” It is worth noting, however, that student feedback is often relatively brief and superficial, as students might be cautious to express critical thoughts to their teachers who prepared them for these opportunities. Teachers are also motivated to seek positive feedback, including smiling photos of their Ethiopian students in China that they can turn into collages and large posters to hang up on campus and advertise the Chinese language programme as an exciting travel experience.

China as an employer

Other than marketing China as an accessible global adventure, CIs and CCs also cater to Ethiopian students’ employment aspirations. On a poster listing the reasons to study Chinese at Mekelle University, the first reason is purely opportunistic: “The relationship & friendship between Ethiopia and China are getting better and better, so many Chinese companies invest here and the amount is increasing dramatically.”Footnote 65 To attract more students, some CI/CC programmes around the country host large-scale promotion events that fuse culture with strategic business narratives. The Chinese director of the CC at Mekelle University, for instance, shared that the university had done little to promote the Chinese language degree programme, and that the CC did its own advertising via cultural events, such as celebrations of Chinese holidays that involved representatives from Chinese companies, and at times alumni that tell students about their experience of working at Chinese companies.Footnote 66 According to the director, such monthly events can attract up to 500 participants.

Those initially intrigued by some facets of China's traditional culture, like martial arts, were ultimately motivated to keep up with Chinese for practical reasons. “I noticed Chinese actively involved in [the] construction of the city and other major projects, and also read media reports about China's infrastructure projects. I am a civil engineer and I thought Chinese would be useful in my work,” shared a graduate of the AAU CI programme, who now serves as a consultant for Chinese construction projects.Footnote 67 Another graduate of the same programme was initially lured in by Chinese martial arts, something he already practised before going to university, but he ended up switching to the Chinese language degree programme after realizing that it carried strong job potential.Footnote 68 Another interviewee explained that he saw opportunities in the communication gaps between Chinese and Ethiopians that he wanted to take advantage of: “I observed lots of miscommunication between Chinese employers and Ethiopian workers around Hawassa Industrial Park, with locals not listening to Chinese bosses; as well as at the airport where Chinese were frequently cheated by local drivers. I thought that if I learned Chinese, I could help fix this problem, so I embarked on studying it.”Footnote 69 During in-class discussions with students at different institutes, most anticipated landing a job at a Chinese company – an opportunity they learned about from their teachers.

In practice, CIs and CCs are conduits for employment at Chinese companies by fusing cultural and professional networking, as well as by preparing students directly and indirectly for the Chinese job market. Other than inviting Chinese company representatives on campus during major cultural events, some CI and CC directors also regularly take Chinese language students to Chinese companies to celebrate holidays, eat Chinese food and network with potential future employers. “They gave us food and said ‘come work for us!’” shared an enthusiastic student at Mekelle University.Footnote 70 The CC at Bahir Dar University even hosted job interviews, directly serving as an employment centre for Chinese companies.Footnote 71 The Chinese directors were transparent about their close ties with Chinese enterprises, and described these relationships as mutually beneficial. “The companies occasionally help us with logistical operations of Chinese language programmes by donating computers or providing meals for the holidays, and we train their future Chinese-speaking labour force,” shared the former Bahir Dar University CC director, enthusiastically.Footnote 72 Collaboration with Chinese enterprises was encouraged by Hanban as part of CIs’ improvised localization, introduced earlier. But it is up to the directors on the ground to build these networks and to take advantage of them in expanding their programmes.

Other than direct job networking, Chinese teachers also attempt to equip students with practical skills, in addition to spoken Chinese, to facilitate their adaptation to the Chinese work environment, including punctuality and social media networking. In scolding students for showing up late for Chinese classes, some teachers try to motivate timely arrival by warning students about heavy repercussions they would face for tardiness at Chinese companies. And Chinese language students are also encouraged to join WeChat, improving students’ digital literacy – critical for navigating modern Chinese society and workspaces.

Interviews with former CI/CC students who secured employment at Chinese companies showed that employment at Chinese companies is a relatively realistic prospect and such roles are fulfilling, legitimizing the efforts of CIs/CCs. While the university administrators did not offer exact statistical data on employment of former Chinese language students, their own selective surveys of and conversations with former graduates suggest that the majority do get employed thus far. Chinese speakers tend to start out as translators at Chinese companies, earning on average US$500 per month – a lofty sum in comparison to an average entry salary of US$35–40 a month in Ethiopia.Footnote 73 Those who spent time studying and practising the language in China enjoyed better job prospects. Employment with Chinese companies includes free housing and meals at company compounds. Current and former translators interviewed for this study, moreover, treat these jobs as an entry point into the Chinese business world. They regularly negotiate with government ministries, and at times even guide workers in their native language on production processes. After the initial immersion into the Chinese business culture, translators tend to branch out into freelance work, still serving Chinese businesses, but on their own terms. Practical aspirations of Ethiopian students in learning Chinese, therefore, inspired and sustained by their Chinese teachers, shift into long-term professional ties with Chinese business communities, and dreams of personal enrichment from those ties. Initiation trips to China, and even more so, translation jobs at Chinese companies, turn into life-changing experiences for Ethiopian students, elevating them into an entrepreneurial class and bringing them into the orbit of China's modernity as co-participants. A former Hanban official for Africa noted that in Africa CIs can really change people's destiny (mingyun 命运) – a transformational effect not achieved to the same extent anywhere else.Footnote 74 Not surprisingly, enrolment in Chinese language courses are still on the rise, in contrast to those in European languages.Footnote 75 When asked why European languages are no longer popular, the registrar at AAU responded curtly, “There are no jobs.”Footnote 76 At the same time, the availability of translator jobs is subject to economic fluctuations, and translators have limited opportunities for upward mobility at Chinese companies, as will be explained in more detail later in this article.

For the teachers: Ethiopia as self-realization

Pragmatic enticement has also been at the heart of convincing directors and especially volunteers to work in Ethiopia, and in Africa more broadly. Prior to the organizational transition, Hanban officials shared that they enticed volunteers to go to Africa with material benefits, as well as by presenting the Africa experience as professionally advantageous and personally enriching.Footnote 77 The widespread public perceptions of Africa as dangerous and underdeveloped make it a relatively unattractive destination for volunteers. Hanban treats Africa as a hardship post, offering higher compensation (interviewees estimated it at US$1,000 a month for volunteers). Volunteering in Africa has also been presented as a career boost – an indicator of professional experience under duress. Hanban officials and university professors also appealed to volunteers’ sense of higher purpose (or meaning) and a quest for adventure. The stipends of volunteers and their distribution has not been made public, but the positioning of Africa as a hardship destination is likely to persist.Footnote 78

Interviews with Chinese directors and volunteers in Ethiopia reveal that they treat their time there as primarily a multifaceted professional opportunity. For the volunteers, but also for some directors, Ethiopia is the first chance to practise teaching Chinese to foreigners. A volunteer teacher at AAU explained her choice to come to Ethiopia in dispassionate terms:

Most of us volunteers are graduates of Chinese as a foreign language major. For us it's the first work experience, the first chance to apply our skills in a classroom. Our university has a partnership with Ethiopia, and our teachers encouraged us to go, so I signed up. The decision to come here for most of us, is a practical one. It has little to do with interest in Africa or in Ethiopia in particular. If I were told to go elsewhere, I similarly wouldn't hesitate.Footnote 79

This demonstrates how Ethiopia represents a fungible work destination. Similar reflections were shared by Chinese volunteers stationed across Ethiopia. Some mentioned that it was a chance to discover whether they would want to teach foreigners or Chinese students in the long run. “I wanted to check out the process of teaching Chinese to foreigners and compare it to that of teaching Chinese to Chinese. So, I came here to have a look [chulai kan yixia 出来看一下],” shared a recent graduate stationed in Jimma, who subsequently decided that he wanted to be based in China.Footnote 80

Others were driven by a general ambition of gaining experience abroad and practicing English. Similar to Ethiopian students treating China as their first encounter with the global, Chinese teachers use Ethiopia as their channel for seeing the world. Only two directors interviewed had extensive overseas experience prior to coming to Ethiopia, and for most volunteers Ethiopia was their first time outside the country. Improving one's English skills was noted as an important part of the international experience, with some directors sharing that they speak more freely in Ethiopia than they would in the West, where they feel self-conscious about making mistakes. The author's observation of Chinese language classes found that many teachers have limited English skills – a complaint often voiced by Ethiopian staff and students. In a way, Ethiopia is a testing ground for Chinese teachers – a place to experiment, make mistakes and hone skills for other (more desired) destinations.

The volunteers and directors didn't express a particular enthusiasm for Ethiopia as a destination, and most had not done any research about the country before departure. Those who did, like the director of the CC in Mekelle University, were reassured by the apparent similarities between Ethiopia and China, including rapid economic development and relative safety.Footnote 81 The superficial understanding of Ethiopia is not surprising given that pre-departure training sessions delivered by Hanban only offered a basic introduction to the African continent, with little to no training on specific countries they are assigned to, according to the participants. (While overseas teacher training is now carried out by CLEC, these trainings are unlikely to see significant transformations.)

While treating Ethiopia as an ambivalent destination, some volunteers and directors embrace it as an adventure. Volunteer Gui, for instance, extended her stay beyond the one-year commitment and switched to working for a well-known Chinese entrepreneur in Addis Ababa. For others, Ethiopia offers an introspective journey – a break from work and life pressures in China. Akin to other Chinese communities in Ethiopia, like that of the construction workers depicted vividly in Driessen's work,Footnote 82 Chinese teachers lead an ascetic communal lifestyle, rarely mixing with their Ethiopian colleagues or students outside of official work hours, or independently exploring the country. On most days, they return to their apartments by 5 p.m. for safety reasons and socialize largely among themselves. Some even managed to bring seeds from China to grow their own vegetables in the gardens – a process narrated with amusement.

This somewhat isolated lifestyle was described as a mix of boredom and enchantment. Despite relatively harsh living conditions, including frequent water and electricity cuts and scattered internet service, the volunteers and directors interviewed described their time in Ethiopia as peaceful (anjing 安静) and relaxed (qingsong 轻松). When asked what they liked the most about Ethiopia, they complimented the good air quality and nice climate – drawing contrasts with polluted, fast-paced Chinese cities. The fixed temporality of Chinese teachers’ encounters with Ethiopia may explain their relatively positive outlook on what appears as a somewhat mundane experience. Unlike construction workers, many of whom are pushed into Ethiopia due to material insecurity, and who intend to remain there until they earn enough to build a stable life in China,Footnote 83 the Chinese directors have stable jobs awaiting them at their partner university in Tianjin, and volunteers are likely to get hired as high school teachers or apply to graduate school upon their return.

Interestingly, the attraction of Ethiopia for Chinese directors, and especially for volunteers, is largely self-centred – whether it concerns professional motivations, novelty or escape. Some directors and teachers, namely those encountered in Bahir Dar and Jimma, practised genuine devotion to their profession, adapting to students’ schedules, preparing home-cooked Chinese dishes and initiating introductions to professional opportunities. A meeting with a director at Jimma University, for instance, was frequently interrupted by WeChat messages from students seeking help. “When I see that a student is behind, especially in spoken Chinese, I always offer individual mentorship and adjust to the students’ schedules,” shared the director.Footnote 84 The majority of the directors and especially of the volunteers interviewed in this study, however, seemed to treat their job more as a bearable routine than as a full-on commitment. Observations of classes revealed that some Chinese volunteers were reluctant to correct students’ pronunciation. In one drama class attended by the author, the pronunciation of Chinese tones was so egregious that the content was entirely lost on the listeners, but the teacher persisted with the course plan, not correcting a single student. In the end, the director was too embarrassed to let the author sit through the entire class and cut the visit short. The self-driven rationales of Chinese teachers in coming to Ethiopia, therefore, might translate into mixed degrees of teaching commitment and quality on the ground, something that thus far is overshadowed by the practical offerings of the CI programmes – the global encounters and employment opportunities. In particular, recent graduates shared that they experienced the most improvement in their Chinese language abilities during their stays in China, and as part of their work at Chinese companies where some employers would hand out vocabulary lists and correct their pronunciation.

Pragmatic Enticement: Opportunities and Limitations

This article has demonstrated the workings of China's most controversial soft power export in a national context that is favourably predisposed to its effectiveness. The analysis underscored the practical opportunities bringing together the different participants. For Ethiopian directors, CIs and CCs present job placement opportunities for their graduates, as well as channels for the symbolic alignment of their institutions with the global education community and modernity. For students, the Chinese language allows for a possibility to experience China as a destination and as an employer. And Chinese directors and volunteers treat their CI/CC postings in Ethiopia as professional and personal growth opportunities.

China's embedding of practical, and especially economic, inducements into cultural outreach presents a distinct approach when compared to soft power practices by other major powers in Ethiopia, including the US and Russia. The author's observations of the workings of the American CornersFootnote 85 in Ethiopia revealed that the US approach on the ground emphasizes promotion of political values but offers limited immersive educational opportunities. In contrast to China's improvised response to local demands, the US authorities adhere to the “survival of the fittest” motto whereby the very best would make it to America regardless of the struggle.Footnote 86

Russian cultural promotion in Ethiopia via the Pushkin Center for Science and Culture, run by the Russian embassy, inspires nostalgia for the golden era of Ethiopia–Soviet Union friendship. The newly appointed director noted his intent to build stronger ties with the Ethiopian diaspora who studied in the Soviet Union.Footnote 87 While Russia provides some scholarships to Ethiopian students, Russian directors admit that they cannot compete with the scale of Chinese engagement. “We all know who the winner is here,” noted a former Russian director.Footnote 88

Thus far, the pragmatic nature of China's soft power in Ethiopia – a result of extensive local improvisation – appears to be relatively effective in enticing Ethiopian counterparts. The Ethiopian university administrators who co-direct CIs and CCs, for instance, combine their admiration for Chinese economic development with a practical calculus of domestic job creation. And many Ethiopian students enjoy Chinese culture alongside the material opportunities. Rather than viewing the economic narrative embedded into CI/CC activities as simply a form of co-optation, we can interpret it as localization of China's cultural export to a society that is most concerned with economic development. We can also see it as part of a broader conception of Chinese culture that incorporates economic practices including work ethic and enterprising creativity. The Ethiopian Chinese language translators interviewed for this study, for instance, shared their admiration for how Chinese people do business, including their strong adaptive skills and ability to find business openings in the most difficult environments.

However, the nexus of practical–cultural attraction carries a number of limitations for China's image-building in Ethiopia and beyond in the long term. Specifically, CIs and CCs may face a sustainability crisis due to their dependency on strong China's economic presence in Ethiopia, the relatively limited placement opportunities for Chinese language graduates, the growing expectations from the Ethiopian side and the transient attraction of Ethiopia for Chinese teachers.

Several Ethiopian directors noted a concern that the demand for translators in Ethiopia was a bubble that might eventually burst.Footnote 89 The same employment considerations that drew university leadership towards CIs and CCs are also making some wary of the possibility of the long-term redundancy of a large cadre of Chinese language speakers. These concerns are in part a reflection of the narrow opportunities for Mandarin speakers at Chinese enterprises and in Ethiopian government agencies. If the number of translator jobs was to shrink, there would be a shortage of alternative possibilities. While translators often evolve into small-scale entrepreneurs, very few manage to get promotions within Chinese companies as civil engineers or as managers. During an in-class discussion with Ethiopian students about their work aspirations at Mekelle University, one student after another repeated the word “translator.” Finally, one female student carefully asked: “Are there any other jobs for us?” The Chinese director immediately jumped in, offering awkward reassurances: “Of course there are other jobs, yes, yes,” not elaborating with any examples, and switching topics immediately. This vignette illustrates the awkwardness surrounding the discussion of broader job possibilities for Ethiopian graduates at Chinese enterprises. Current translators interviewed for this study also confirmed that as civil engineers in Chinese companies their salaries would be lower than those of translators, dissuading them from even attempting the pursuit.

These limited possibilities for upward mobility within Chinese companies for Ethiopian employees symbolize the larger unequal power dynamics or asymmetries in the China–Ethiopia relationship and in Sino-African encounters more broadly.Footnote 90 At the same time, these limitations should not be readily framed as a manifestation of neocolonialism – a contentious term often used to depict China's presence in Africa in Western policy narrativesFootnote 91 – associated with deliberate exploitation and indirect control over political and economic systems by an external power.Footnote 92 Chinese companies are not direct conduits of the policies of the Chinese party-state, but rather exercise their own policies on employment and labour relations that vary across sectors.Footnote 93 And Ethiopian translators, as explained earlier, exercise agency in their engagements with Chinese employers and Chinese companies. They tend to see these jobs as temporary launching pads for entrepreneurial careers and as channels for improving their Chinese language and negotiation skills. Upward mobility is limited within these companies, but Ethiopian translators tend to step out of company structures to negotiate better terms, including job flexibility and more competitive salaries.

Moreover, the potentially volatile status of translator jobs is also a result of the constrained job market for Chinese speakers in Ethiopia. While the Chinese language bachelor's degree programme curricula suggest that Chinese speakers could work for Ethiopian government agencies, the author's interactions with key ministries that deal with China, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Finance, found an absence of Mandarin speakers among the current staff. Unlike Western societies where the Chinese language can be seen as a channel to working “with” China, and less “for” China, in Ethiopia there is thus far little connection made between the need for intellectual capital to negotiate better conditions with China and the attendant resource that the Chinese language graduates represent.

Another sustainability concern that might emerge is that of expectation management. Rather than perceiving Chinese efforts as a generous gift, most Ethiopian directors interviewed in this study adopt the attitude of what one former dean described as “getting the most out of them.”Footnote 94 The material roots of enticement translate into escalating demands over time. The Ethiopian director of the FTVETI CI shared that he was pushing his Chinese counterparts to grant more PhD fellowships to his staff and students by threatening to shrink the CI programme.Footnote 95 A Jimma University Ethiopian CC director was frustrated by not getting a bonus payment for his work – something he was aware was provided to his counterparts at other universities.Footnote 96 Expectation management may also become a challenge with students. China will only be attractive insofar as it remains an accessible resource for young Ethiopians by continuing to offer generous educational opportunities.

Finally, the continuous recruitment of Chinese teachers to Ethiopia may come under pressure in the long run. Several CCs in Ethiopia investigated by the author are already experiencing teacher shortages that result in heavy workloads for the existing teachers. In Hawassa, for instance, only four teachers remained out of an initial seven in the Chinese language degree programme. In Jimma, after one teacher left, it took a year to hire a replacement. The teacher shortages need further investigation, but this problem is likely to be exacerbated as Ethiopia becomes a riskier destination for volunteers. In the past four years since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power, and especially during the recent and ongoing armed conflict in the Tigray region, Chinese residents in Ethiopia complained about security concerns, with some imposing an earlier curfew. The pandemic has also resulted in some volunteers returning to China, though CI and CC activities have proceeded online, and have recently resumed in person.Footnote 97 Considering the lack of deeper incentives motivating their work and limited cultural connection to the Ethiopian people, if safety concerns become more acute, Chinese volunteers could easily forgo Ethiopia for another destination. As with Ethiopian university administrators and students, China's cultural ambassadors are primarily motivated by their own interests. Thus far, all sides seem generally satisfied, but the future prospects remain uncertain.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for funding support and feedback received as part of the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) Transregional Research Junior Scholar Fellowship and the Wilson Fellowship. The manuscript was also greatly improved from generous comments from Jeremy Dell, Alexander Dukalskis, Daniel Mattingly, as well as from the participants of the Global China in Comparative Perspective workshop led by Ching Kwan Lee (Taipei 2019). The author is also grateful to Wing Kuang, Luwen Qiu and Tensae Haile for excellent research assistance.

Biographical note

Maria REPNIKOVA is an assistant professor of global communication at Georgia State University.