Background

Thelaziasis, a parasitic ocular disease caused by Spirurid nematodes of the genus Thelazia, represents an important but frequently neglected veterinary concern in global cattle production (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). These worms, including clinically significant species such as T. rhodesi, T. gulosa, and T. skrjabini, inhabit the conjunctival sac and associated ocular tissues, leading to a spectrum of pathological manifestations (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). The disease is biologically transmitted by several flies such as Musca (family Muscidae), Phortica (family Drosophilidae), or Fannia (family Fanniidae) (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Riva, Mibradt, de Sarmiento, Oliva, Brombini, Teixeira, Filho and Okamoto2016; Mupper-san, Reference Mupper-san2023), which serve as IHs by depositing infective third-stage larvae during feeding activities (Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Soulsby, Reference Soulsby1982). Despite its widespread occurrence, thelaziasis often remains underdiagnosed due to nonspecific clinical presentation and limited diagnostic infrastructure in endemic regions, resulting in substantial underestimation of its true economic impact (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025).

The pathogenesis of bovine thelaziasis involves both mechanical trauma and immune-pathological responses induced by the parasites’ movement and feeding behaviour (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). Initial infection typically manifests as epiphora, blepharospasm, and conjunctivitis, which may progress to severe keratoconjunctivitis, corneal ulceration, and even permanent blindness if left untreated (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Coop and Wall2015). Chronic infections contribute to substantial economic losses through reduced weight gain, decreased milk yield, and impaired working capacity in draft animals (Radostits et al., Reference Radostits, Gay, Hinchcliff and Constable2007). Furthermore, secondary bacterial infections often complicate the clinical course (O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991), necessitating additional therapeutic interventions and increasing production costs (Brás, Reference Brás2012). The welfare implications of persistent ocular discomfort further compound the significance of this parasitic disease in cattle management systems (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025).

Epidemiologically, thelaziasis demonstrates distinct temporal and spatial patterns, with highest prevalence observed during warm seasons when vector fly populations peak (Otranto and Dutto, Reference Otranto and Dutto2008). Geographic distribution varies significantly, with well-documented endemic foci in Europe, Asia, and the Americas, particularly in extensive grazing systems (Giangaspero et al., Reference Giangaspero, Traversa and Otranto2004). Recent molecular studies have revealed greater genetic diversity among Thelazia species than previously recognized (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023), suggesting potential variations in pathogenicity and drug susceptibility (Ferroglio et al., Reference Ferroglio, Rossi, Tomio, Schenker and Bianciardi2008). Despite these advances, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding the precise transmission dynamics, risk factors, and long-term epidemiological trends, particularly in developing countries where surveillance systems are often inadequate (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025).

Current control strategies for bovine thelaziasis rely heavily on periodic anthelmintic administration, primarily using macrocyclic lactones such as Eprinomectin, Ivermectin and Doramectin (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Ahmed, Bordoloi, Sarma, Thakuria and Nath2021). Integrated pest management targeting vector flies, including environmental modifications and judicious insecticide use, shows promise but requires careful implementation to ensure sustainability (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Geden and Hogsette, Reference Geden and Hogsette2006). The recent identification of zoonotic potential in some Thelazia species, particularly T. gulosa, has added a new dimension to disease control, emphasizing the importance of One Health strategies (Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Breen, Bonura, Hoyt and Bishop2018, Reference Bradbury, Gustafson, Sapp, Fox, De Almeida, Boyce, Iwen, Herrera, Ndubuisi and Bishop2020).

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on bovine thelaziasis, addressing critical aspects of parasite biology, host-parasite interactions, diagnostic methodologies, and treatment and control approaches. By evaluating existing literature and identifying key research gaps, we aim to provide a foundation for future investigations toward more effective surveillance systems, novel therapeutic agents, and sustainable integrated management programs. Enhanced understanding of this parasitic disease is essential for mitigating its economic impact and improving cattle welfare in both intensive and extensive production systems worldwide.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

To conduct a comprehensive review on bovine thelaziasis, a systematic approach to literature search and selection is essential. The search utilizes a variety of databases and sources, including primary databases such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, alongside specialized databases like CAB Abstracts, Veterinary Sciences Database, and ProQuest. Additionally, grey literature will be considered, encompassing theses, dissertations, conference proceedings, and technical reports from veterinary institutions. The search employed specific keywords related to bovine thelaziasis, including ‘Bovine thelaziasis’, ‘Thelazia spp. in cattle’, ‘ocular nematodes in cattle’, ‘Thelazia infection’, and ‘bovine eye worm.’ Combined search terms were also used, such as ‘bovine thelaziasis AND epidemiology’, ‘Thelazia AND diagnosis’, ‘Thelazia AND treatment’, and ‘Thelazia AND life cycle’, along with species-specific terms like ‘Thelazia rhodesi’, ‘Thelazia gulosa’, and ‘Thelazia skrjabini.’ The search focuses on studies published in the last 20–30 years to ensure the inclusion of relevant and contemporary diagnostic and treatment methods, while also considering historical studies for contextual background. The primary focus is on English-language publications, although non-English studies with English abstracts included for those containing essential data.

Inclusion criteria

Research must concentrate on bovine thelaziasis attributed to Thelazia species, such as T. rhodesi, T. gulosa and T. skrjabini. Eligible publications include research articles, reviews, case studies, and epidemiological assessments. Studies should address aspects such as diagnosis, treatment, epidemiology, life cycle, and management of bovine thelaziasis. Additionally, research conducted in both endemic and non-endemic areas is required to ensure a comprehensive understanding.

Exclusion criteria

Articles lacking sufficient data, exhibiting poor research design, or not undergoing peer review were disregarded. Non-English language publications that do not have accessible translations were also not considered. Moreover, duplicate publications or those containing overlapping datasets were excluded.

The vision of cattle: anatomical and functional review

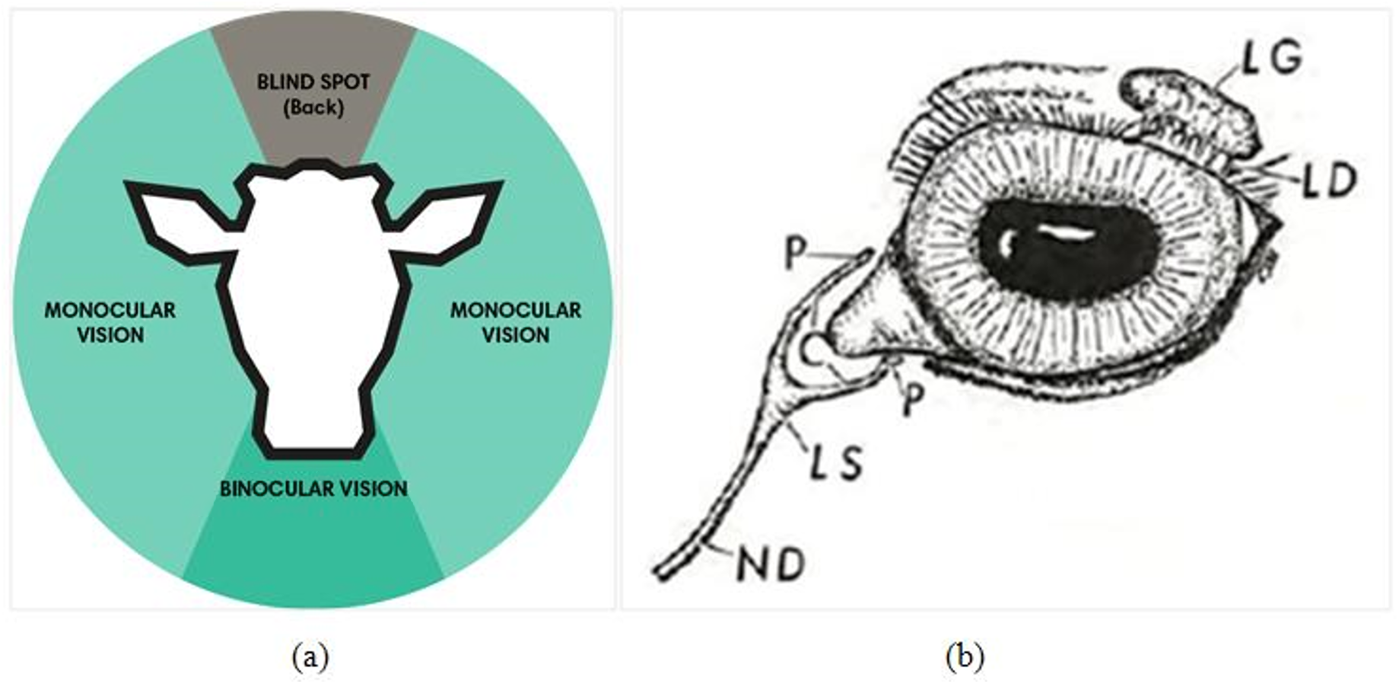

The organ of vision is formed by the eyeball and accessory structures, which include the eyelids, the conjunctiva, and the lacrimal and muscular apparatus. The eyeball is housed in the orbit, which in cattle is completely surrounded by bones. In cattle, the globe eye stands out beyond the orbital limit so that, with the help of eye movements, cattle have a visual field of approximately 360 degrees (Fig. 1a) (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Getty, Reference Getty1986; Gloobe, Reference Gloobe1989). Hence, the visual system plays a crucial role as a fundamental sensory modality in the perception of the environment (Brás, Reference Brás2012) (Fig. 1a and b).

Figure 1. Field of vision in cattle (a) and the lachrymal system (b). C = tear ducts; LD = lacrimal duct; LG = lacrimal gland; LS = lacrimal sac; ND = nasolacrimal duct. Adapted from: (a) van der Linden (Reference van der Linden2023) and (b) Gelatt (Reference Gelatt2007).

Veterinary ophthalmological pathology presents a wide variety of ocular conditions, and examination of the conjunctiva has high practical importance. The conjunctiva is a continuous structure; however, to facilitate its description, it is divided into palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva. The palpebral conjunctiva covers the inner surface of the eyelids and may be pigmented near the eyelid margin. The bulbar conjunctiva is continuous to the corneal epithelium over the eyeball, starting at the corneosclerotic junction or limbus; next to this area, the conjunctiva may present pigmentation. The junction between the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva occurs in the fornix. Therefore, when the eye is closed, the cornea and conjunctival mucosa form a cavity called the conjunctival sac (Gelatt, Reference Gelatt2007; Gloobe, Reference Gloobe1989).

In the medial angle of the eye, a fold of conjunctival mucosa forms that covers the nictitating membrane. This moves over the cornea in a dorsolateral direction and contains a T-shaped cartilage whose transverse part is parallel to the free margin of the membrane, which is normally pigmented. Surrounding the cartilage axis is glandular tissue arranged in a flat part and a rounded part, which together form the gland of the nictitating membrane or Harderian gland. Glandular tissue secretes tear fluid similar to that of the lacrimal gland through two to three ducts that open on the bulbar surface of the nictitating membrane (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Gelatt, Reference Gelatt2007; Getty, Reference Getty1986).

The lacrimal gland is the main ocular secretory gland and is found in the dorsolateral position of the orbit; it is generally surrounded by fat. In adults, it measures between 6 and 7 cm long, 1 cm thick and 3.5 cm wide and is compressed between the orbital wall and eyeball. With a lobulated appearance, the gland passes secretions from lacrimal ducts through six to eight larger ducts and several smaller ducts in the vicinity of the conjunctival fornix of the upper eyelid. Tear fluid is collected near the lacrimal caruncle, at the medial angle of the eye, through the tear ducts. These structures are 1–1.5 cm in length and converge into the lacrimal sac, which can measure between 5 and 8 mm in diameter. The nasolacrimal duct follows a straight path of 12–15 cm in length, opening on the lateral wall of the nostril (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Getty, Reference Getty1986).

History and discovery of thelaziasis

Early discoveries and genus establishment

The first description of ocular nematodes consistent with the genus Thelazia was made by Johannes Rhodes in 1676 (Brás, Reference Brás2012), who observed the parasite on the cornea of a bovine (Bos taurus). In 1819, Bosc created the genus Thelazius, alluding to these same nematodes, which were referred to as ‘Thelazia of Rhodes’ (Dictionary of Natural Sciences, 1828; as cited in Brás, Reference Brás2012). Since then, several species of Thelazia have been reported in mammals and birds in different parts of the world (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

One of the earliest species to be described was Thelazia lacrymalis, identified by Gurlt in 1831. This species was initially found in horses and became recognized as a significant parasite of equines across Europe, Asia, and the Americas (Skrjabin et al., Reference Skrjabin, Sobolov and Ivashkin1971; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Tian and Huang2007). Gurlt’s work laid the foundation for understanding the morphology and pathology of eyeworms in domestic animals.

Thelazia rhodesi was first described by Desmarest in 1827 and has since been recognized as a primary parasite of cattle and other bovids (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). It was later studied in detail by Skrjabin and others in the mid-20th century, who documented its life cycle and IHs (Musca species) (Deak et al., Reference Deak, Ionică, Oros, Gherman and Mihalca2021). Then, a landmark discovery came in 1910 when Railliet and Henry described T. callipaeda from the eyes of a dog in China (Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Lia, Cantacessi, Testini, Troccoli, Shen and Wang2005; Railliet and Henry, Reference Railliet and Henry1910). This species, often called the ‘Oriental eyeworm’, would later be recognized as the most common cause of human thelaziasis. By the year 2000, over 250 human cases had been reported worldwide, primarily in Asia but with increasing cases in Europe (Dolff et al., Reference Dolff, Kehrmann, Eisermann, Dalbah, Tappe and Rating2020; Otranto and Dutto, Reference Otranto and Dutto2008; Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Lia, Cantacessi, Testini, Troccoli, Shen and Wang2005). The unique aspect of T. callipaeda’s transmission was discovered much later—it is spread by male drosophilid flies (Phortica variegata in Europe and Phortica okadai in China) (Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Lia, Cantacessi, Testini, Troccoli, Shen and Wang2005), making it the only known parasite transmitted exclusively by male vectors (Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Cantacessi, Testini and Lia2006, Reference Otranto, Stevens, Cantacessi and Gasser2008).

Thelazia gulosa and T. skrjabini were both described in the early 20th century. Thelazia gulosa was identified by Railliet and Henry in 1910 as a cattle eyeworm, while T. skrjabini was described by Erschow in 1928 (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Tian and Huang2007). These species were initially considered veterinary parasites until 2018, when T. gulosa was identified in a human case in Oregon, USA—the first reported human infection by this species (Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Breen, Bonura, Hoyt and Bishop2018). Skrjabin’s work in the mid-20th century provided important taxonomic clarifications for these species. His studies helped distinguish between T. gulosa, T. skrjabini, and T. rhodesi in cattle, which often co-occur in the same geographic regions (Deak et al., Reference Deak, Ionică, Oros, Gherman and Mihalca2021; Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020). Also described in 1910 by Railliet and Henry, T. leesei was identified from the vitreous body of dromedary camels in Lahore, Pakistan and Punjab, India (Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Sazmand, Sadr, Said, Uni, Otranto and Borji2024). This species has since been reported in camels across its range from North Africa to Central Asia. Interestingly, historical records suggest T. leesei may have been observed as early as 1853 by Goubaux in France, though this was only recognized retrospectively (Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Sazmand, Sadr, Said, Uni, Otranto and Borji2024).

Additionally, T. californiensis was described by Price in 1930 from dogs in the western United States (Xue et al., Reference Xue, Tian and Huang2007). This species gained medical significance when it was identified as the cause of several human cases in North America, particularly in California. Price’s work helped establish the diversity of Thelazia species in the New World.

Mid-20th century advances

The mid-20th century saw significant advances in understanding thelaziasis, particularly through the work of Soviet parasitologists’ like Skrjabin. His comprehensive studies on Spirurid nematodes, published in the 1960s, provided detailed morphological descriptions and life cycle information for many Thelazia species (Deak et al., Reference Deak, Ionică, Oros, Gherman and Mihalca2021; Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020). During this period, researchers also identified the IHs for several Thelazia species, recognizing that various Musca, Fannia, and Phortica flies served as vectors by feeding on ocular secretions (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Otranto and Dutto, Reference Otranto and Dutto2008; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Tian and Huang2007). This discovery was crucial for understanding transmission dynamics and developing control measures.

Recent discoveries and molecular era

In recent decades, molecular techniques have revolutionized Thelazia taxonomy and epidemiology (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Cotuţiu et al., Reference Cotuţiu, Cazan, Ionică, Cârstolovean, Irimia, Aldea, Şerban, Chişamera, Haşaş and Mihalca2025; Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023). Genetic studies have confirmed species identities and revealed phylogenetic relationships. For instance, a recent study on T. leesei from Iranian camels provided the first molecular characterization of this species, showing it forms a sister clade to T. lacrymalis (Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Sazmand, Sadr, Said, Uni, Otranto and Borji2024). The 21st century has also seen expanding geographic ranges for some species, particularly T. callipaeda in Europe, and the recognition of new host species, including the first autochthonous cases of T. callipaeda in the United States in 2021 (Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Lia, Cantacessi, Testini, Troccoli, Shen and Wang2005).

General description of bovine thelaziasis

Thelaziasis, occasionally spelled ‘thelaziosis’, is the term for infection with parasitic nematodes of the genus Thelazia; Bosc, 1819 (Mupper-san, Reference Mupper-san2023; Bot, Reference Bot2021). These Thelazia nematodes are often referred to as ‘eyeworms’ (Mupper-san, Reference Mupper-san2023; Bot, Reference Bot2021); hence, bovine thelaziasis is an infection of the eye of cattle, buffaloes and bison by any of the Thelazia species.

Aetiology and taxonomic classification

The genus Thelazia is the causative agent of the disease thelaziasis, affecting a diverse range of hosts, including humans, canines, felines, equines, camels, and bovines (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Breen, Bonura, Hoyt and Bishop2018; Deak et al., Reference Deak, Ionică, Oros, Gherman and Mihalca2021; Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Sazmand, Sadr, Said, Uni, Otranto and Borji2024). Taxonomically, Thelazia belongs to the Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Nematoda, Class Secernentea, Order Spirurida, and Family Thelaziidae (Mupper-san, Reference Mupper-san2023). Members of the genus Thelazia are characterized by a cuticle exhibiting transverse striations in both sexes, which are sometimes well marked at the anterior end (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Naem, Reference Naem2011). The depth and overlap of cuticular edges assist in the attachment and movement of the parasite along the corneal surface of the host (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Janovy and Nadler2009; Brás, Reference Brás2012).

There are about 17 species of Thelazia, including T. callipaeda (Oriental eye worm), T. californiensis (California eye worm), T. gulosa (Cattle eye worm), T. lacrymalis (which mainly affects horses), T. rhodesi (found in cattle), T. leesei, T. alfortensis, T. skrjabini, T. ershowi, T. bubalis, and T. anolabiata, that have been reported to cause ocular infestations in animals (Do Vale et al., Reference Do Vale, Lopes, da Conceição Fontes, Silvestre, Cardoso and Coelho2019, Reference Do Vale, Lopes, da Conceição Fontes, Silvestre, Cardoso and Coelho2020; Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021) (Table 1), which tend to be specialized as definitive hosts (DHs) (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Among them, seven are quite common (T. rhodesi, T. gulosa, T. skrjabini, T. lacrymalis, T. callipaeda, T. californiensis, and T. leesei) and cause veterinary and/or medical concerns in various parts of the world (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). For the other ten species, there is still a lack of information regarding their morphology, biology, and epidemiology (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

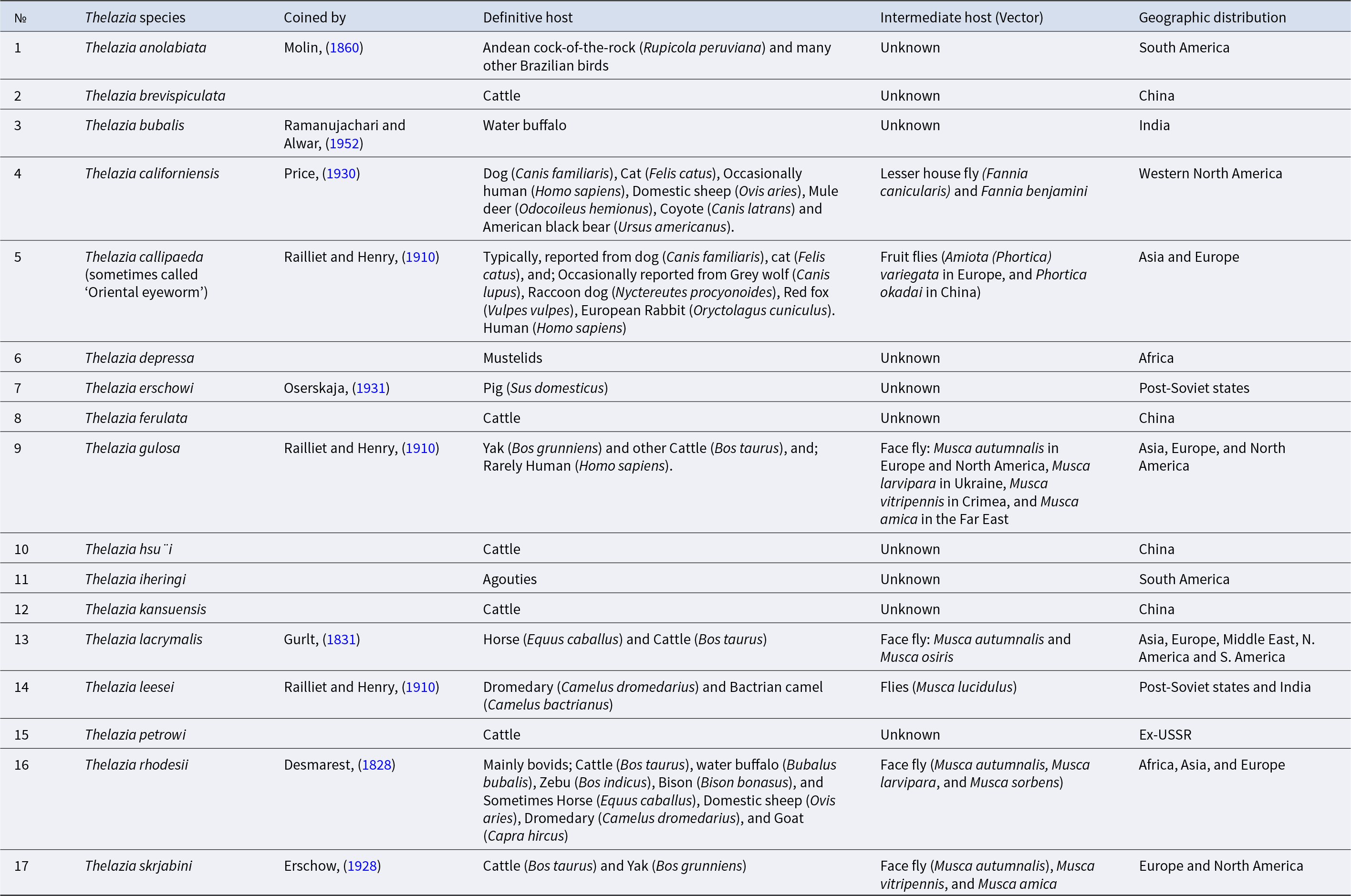

Table 1. Geographic distribution of Thelazia species and their vectors

Source: Otranto and Traversa (Reference Otranto and Traversa2005), and Mupper-san (Reference Mupper-san2023), complemented with Brás (Reference Brás2012).

Bovine thelaziasis is associated primarily with three species, namely, T. gulosa, T. skrjabini, and T. rhodesi (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Naem, Reference Naem2011), particularly in Africa, Asia and Europe, in which the latter is the most common and harmful to cattle in many countries (Naem, Reference Naem2011) (Tables 1 and 2). However, there are exceptions, which report the presence of T. lacrymalis in cattle, despite this species parasitizing primarily horses (Equus caballus) (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Naem, Reference Naem2011) (Table 1). Several authors have reported the occurrence of mixed infections in cattle with different species of Thelazia at the same time, which implies that specific species recognition is necessary (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Species are distinguished not only by DH and/or IH but also by the morphological differences they present, such as the appearance of the vulvar opening, the characteristics of transverse cuticular striations and the number of male caudal papillae (Naem, Reference Naem2011; Brás, Reference Brás2012; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014). Additionally, molecular differentiation plays a crucial role in distinguishing between species (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Sazmand, Sadr, Said, Uni, Otranto and Borji2024).

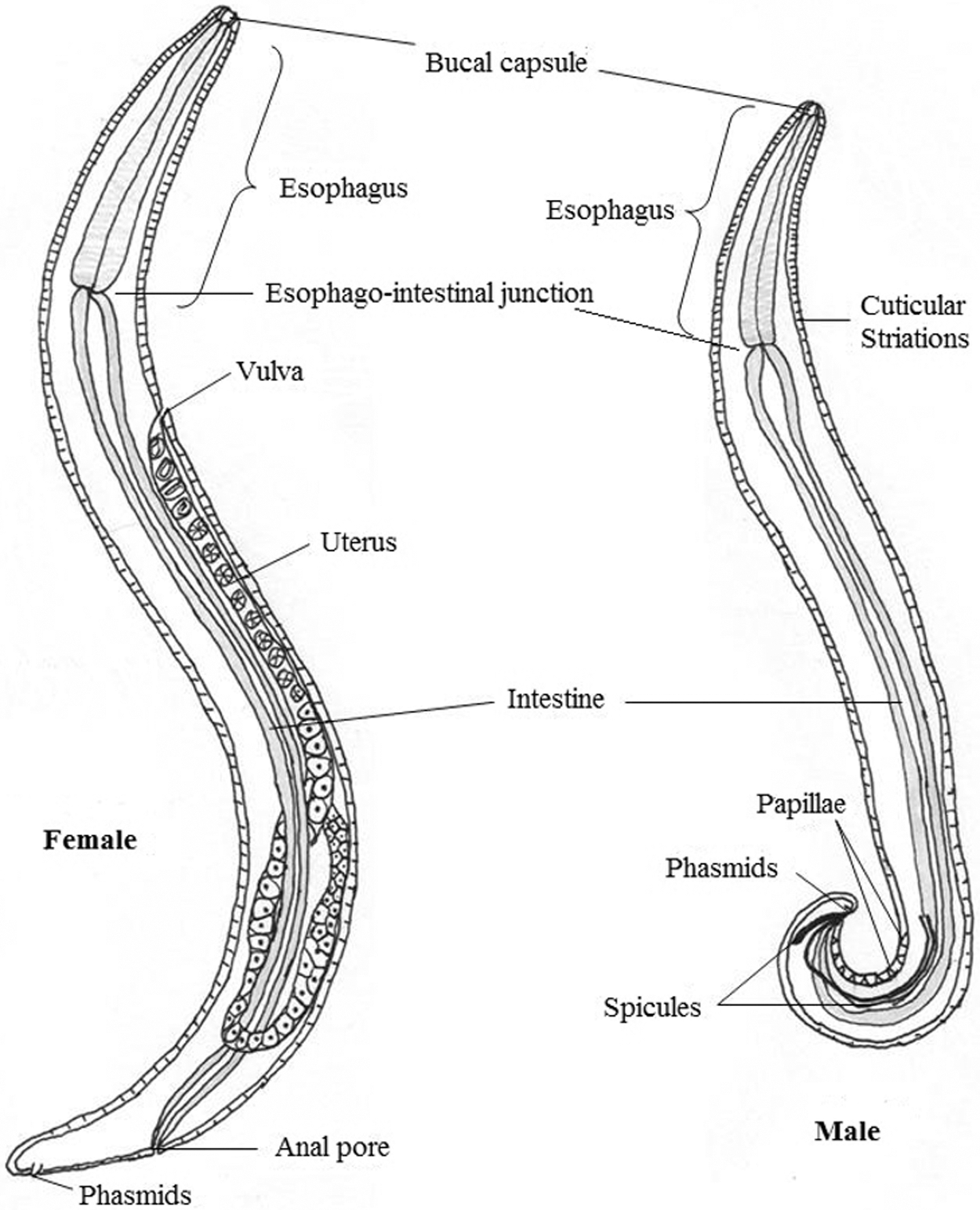

Table 2. Worldwide prevalence of the three Thelazia species in cattle

min = minimum; max = maximum.

a Result depicted is for both species of Thelazia.

b Overall prevalence.

Predilection site

The genus Thelazia is an endoparasite of the ocular orbit and associated tissues located in the conjunctival sac, under the nictitating membrane, within the eyelids, and in the tear glands and lacrimal ducts of various mammalian and bird hosts, including humans (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Do Vale et al., Reference Do Vale, Lopes, da Conceição Fontes, Silvestre, Cardoso and Coelho2020; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005; Bot, Reference Bot2021). However, it has the particularity, as Otranto and Traversa (Reference Otranto and Traversa2005) noted, of being exposed to the air and the external environment, like as any ectoparasite. In fact, the bovine eye looks like an organ that is rarely recommended as a habitat for parasites compared with the intestine. However, Thelazia spp. have adapted to the lacrimal environment and have achieved great success. Each species of Thelazia has developed, even reaching a predilection for different areas of the eye (Kennedy and MacKinnon, Reference Kennedy and MacKinnon1994). The nematode has developed protective mechanisms against lacrimal defense factors, such as lysozymes, complement and immunoglobulins. Thus, the supply of nutrients to the avascular cornea is increased by the tear, which contains concentrations of electrolytes and glucose similar to those in plasma (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

Morphology and identification

General morphology

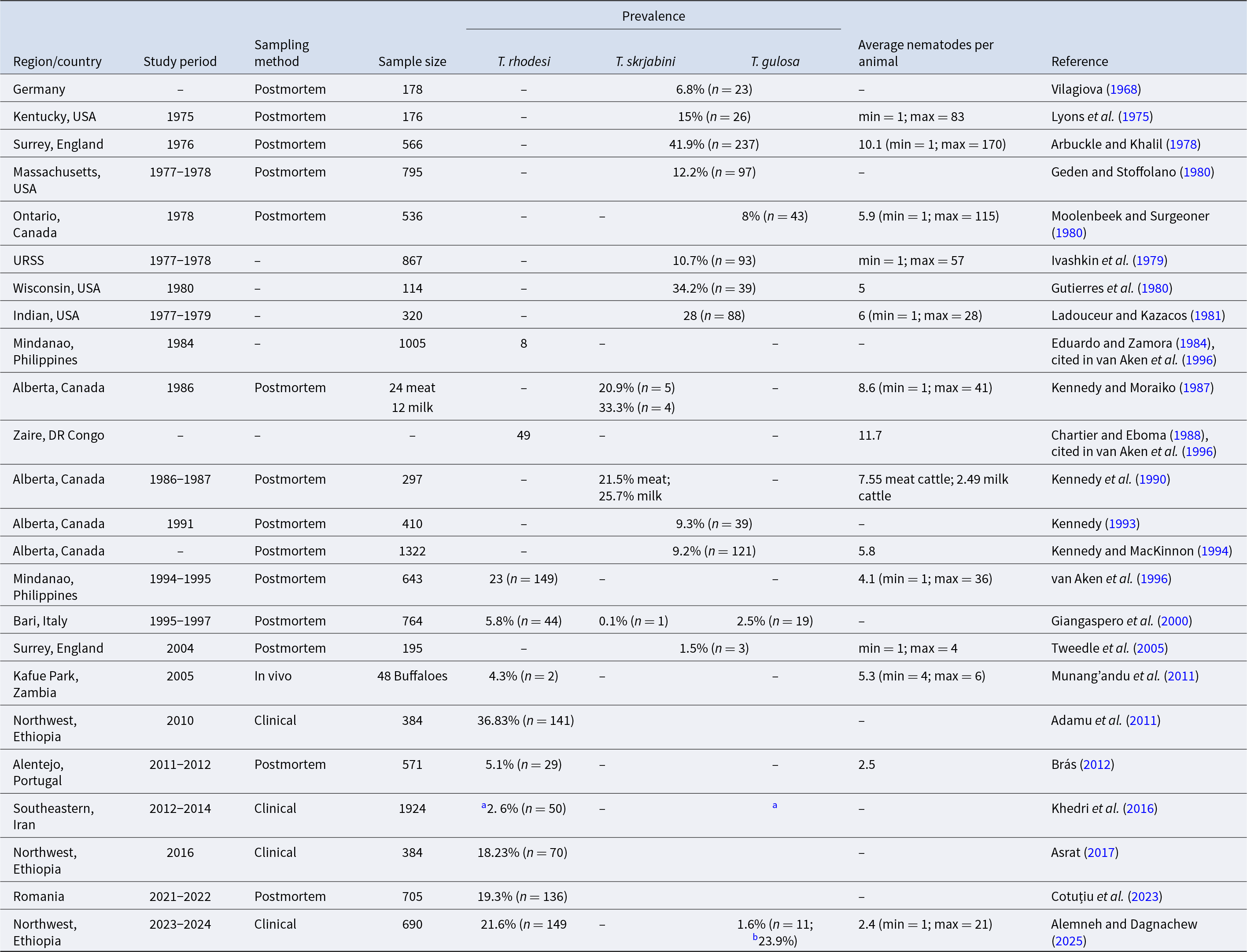

The descriptions by Bosc (1819) and F. Hopkinson (cited by Lee, Reference Lee1840, p. 287) broadly define nematodes of the genus Thelazia (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Adult nematodes are small, approximately 2 cm long, slender in shape and slightly transparently milky-white in colour (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Naem, Reference Naem2011). They have a tubular digestive system with two openings (Junquera, Reference Junquera2022) and a round tapering on both sides, in which the anterior sucker end and posterior excretory portions are tapered (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014). They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs or circulatory system, i.e., neither a heart nor blood vessels. The worm’s body is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough (Junquera, Reference Junquera2022). The cuticle bears prominent transverse striations (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014), which are characteristic features of these worms (Junquera, Reference Junquera2022) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Morphological features of adult Thelazia worms (female and male). Adapted from: Brás (Reference Brás2012) with modifications.

The cephalic region is similar between both sexes of this genus (Fig. 2). Nematodes of the genus Thelazia have a mouth without lips, and a well-shaped mouth capsule develops with thick walls (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Janovy and Nadler2009). The anterior end also has two lateral cervical papillae, simple and similar in shape, one on each side of the parasite. The cervical papillae are normally very small and inconspicuous, which may lead to erroneous conclusions, namely, that they are absent in some nematode species. Considering their structure and position, it is likely that they have a mechanoreceptor function, allowing the nematode to determine whether it can pass through narrow spaces. The posterior end of both sexes is blunt, with two nipple-shaped phasmids (Fig. 2). Phasmids are involved in assessing the intensity of a given stimulus, allowing the nematode to maintain itself in an appropriate environment (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

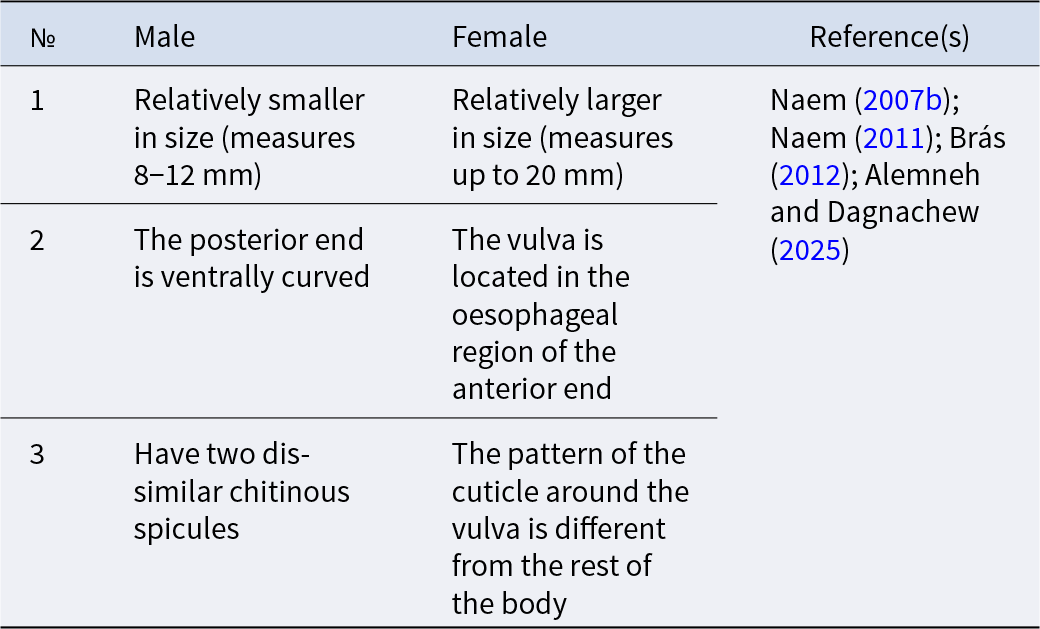

The male Thelazia measures 5–17 mm (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023), and is identified by ventral curving of the posterior end and by the number of pre- and postcloacal papillae (Junquera, Reference Junquera2022). The authors argued that the caudal papillae have chemoreceptor and mechanoreceptor functions. The number of papillae in the anal glands, particularly the preanal papillae, has taxonomic importance since the number of papillae varies depending on the species of the genus Thelazia (Gupta and Kalia, Reference Gupta and Kalia1978; Naem, Reference Naem2007a). The tail is without caudal wings or gubernaculum. Males have two dissimilar chitinous spicules that attach to females during copulation (Junquera, Reference Junquera2022). The length of the smaller spicules ranges from 0.092 to 0.191 mm, while the larger spicules measure between 0.453 and 0.699 mm (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023) (Fig. 2) (Table 3).

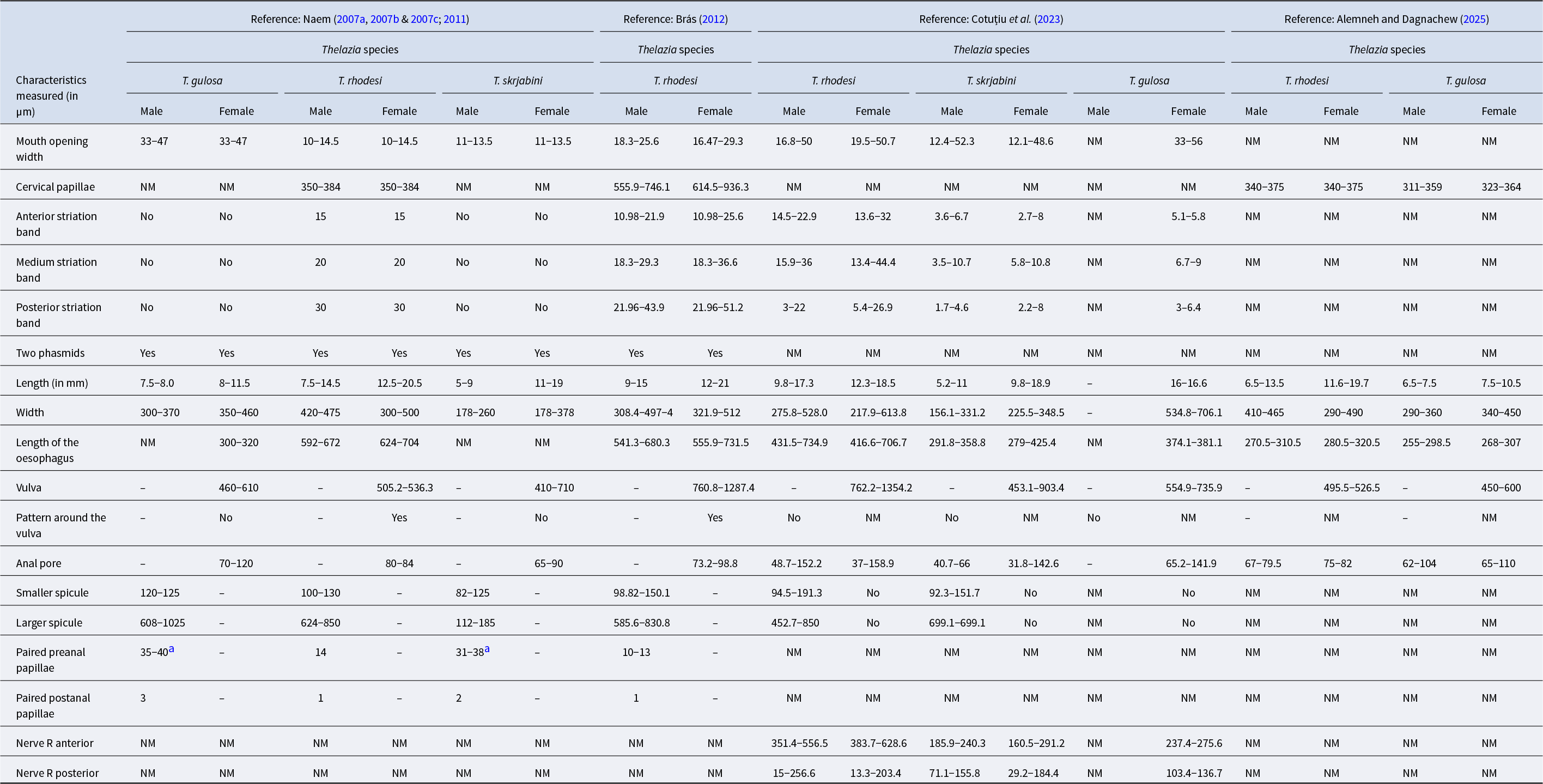

Table 3. Morphological identification keys between male and female Thelazia species

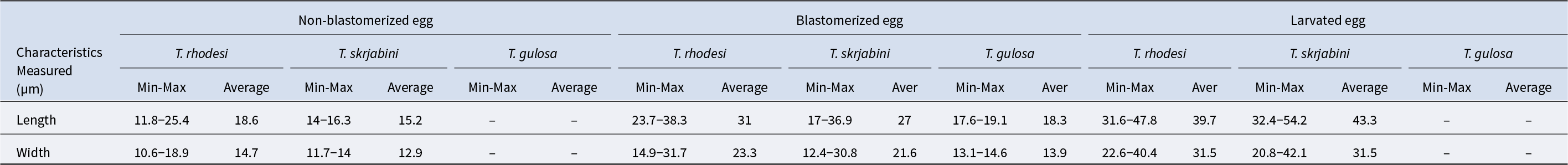

Female Thelazia species measure up to 21 mm (2.1 cm) in length (Brás, Reference Brás2012) and are distinguished from male Thelazia species by the position of the vulva and oesphago-intestinal junction (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014) (Fig. 2) (Table 3). In females, the vulva is located at the anterior end of the body, in the oesophageal region, whereas the anal pore is present at the posterior end. The uterus is directed caudally and contains eggs that are sometimes embryonated (Gorgot, Reference Gorgot1947; Brás, Reference Brás2012). The egg is very small and colourless; first-stage larvae (L1) form special structures, like lungworms inside the shell (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014). The egg morphology of Thelazia species varies by developmental stage: non-blastomerized eggs measure on average 15.2–18.6 µm in length and 12.9–14.7 µm in width, blastomerized eggs range from 18.3–31 µm in length and 13.9–23.3 µm in width, and larvated eggs are even larger, measuring 39.7–43.3 µm in length and 31.5 µm in width (Table 4) (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023).

Table 4. Morphometric characteristics of the eggs of Thelazia species in cattle (data source: Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023)

Min = minimum; Max = maximum.

Thelazia species can be differentiated by the appearance of the cuticular transverse striations, the depth and width of the buccal cavity, the placement of the vulval (vaginal) opening relative to the esophago-intestinal junction, the morphology of the tail and anal opening (the number of caudal papillae) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2019; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014), the medial body width, placement of the nerve ring relative to the oesophagus, and the size of the eggs (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023) (Fig. 2).

Larval morphology

The larval morphology of Thelazia species exhibits distinct measurements across its developmental stages. For L3 larvae, the average length ranges from 260.6 to 274.5 μm, with a width of 8.7–9.2 μm. In the case of L4 larvae, the average length significantly increases to between 9,429.6 and 9,997.9 μm, while the width varies from 235.4 to 319.1 μm. The L5 larvae show even greater dimensions, with an average length spanning from 12,408.2 to 16,479.4 μm and a width ranging from 359.1 to 629.8 μm (Table 5) (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023).

Table 5. Morphometric characteristics of the larval stages of Thelazia species in cattle (data source: Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023)

Data for L3 and L4 of T. gulosa is not available; Min = minimum; Max = maximum; Nerve R anterior = the distance between the midpoint of the Nerve ring and the proximal end of the oesophagus; Nerve R posterior = the distance between the midpoint of the Nerve ring and the distal end of the oesophagus.

Thelazia species morphology

Thelazia rhodesi Desmarest, 1827

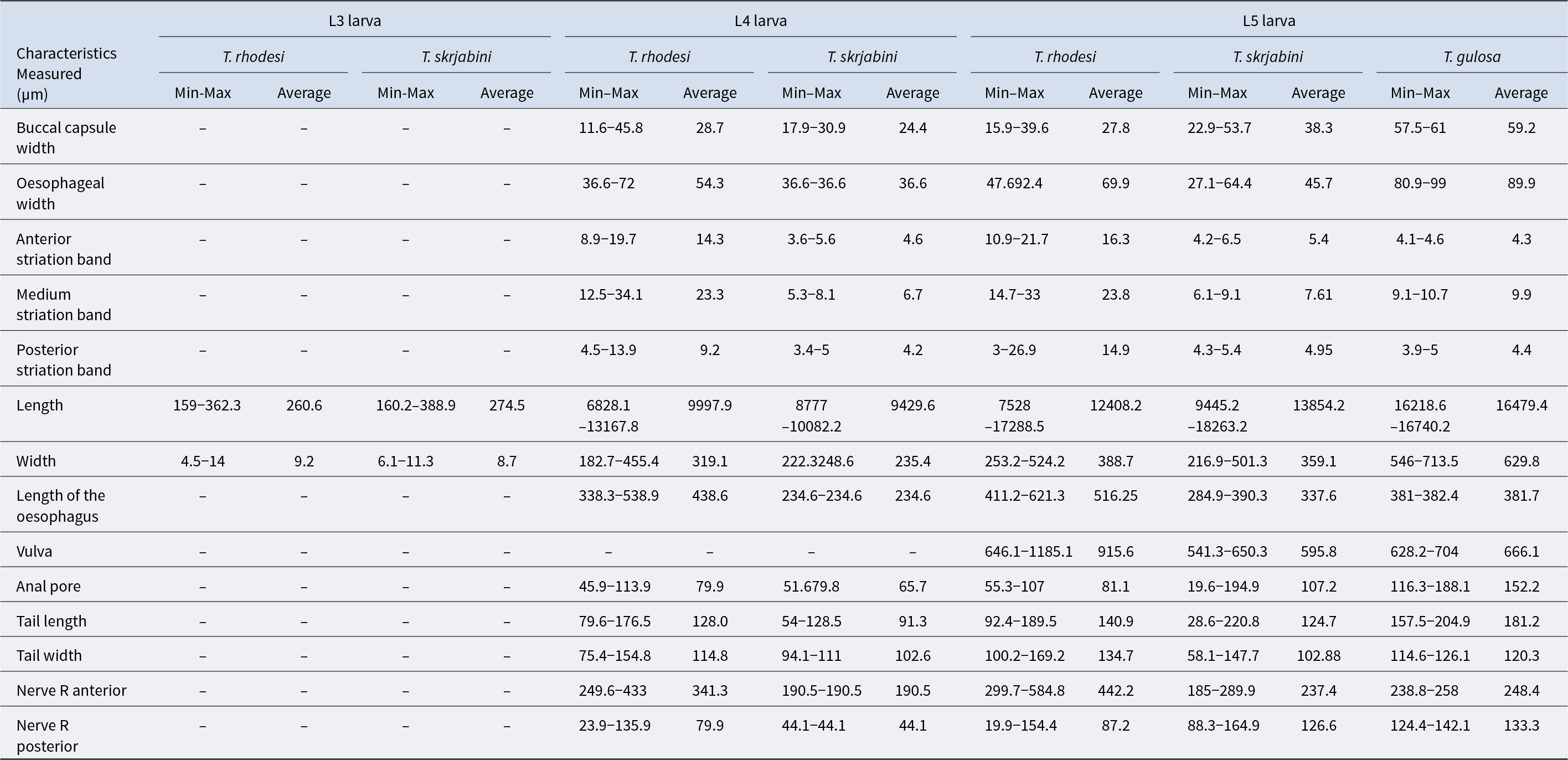

The body is milky-white, with thick, prominent transverse striations in both sexes, resulting in a serrated appearance. The spacing between these striated bands measures 15 μm in the anterior section, 20 μm in the middle section, and 30 μm in the posterior section. The cephalic region is similar in both sexes. The buccal capsule is short and broad, widest at the middle, and has no lips (Fig. 3). Around the mouth, four pairs of submedian small, conoidal cephalic papillae and two lateral amphidal apertures are observed. Additionally, there are two lateral cervical papillae, one on each side, 350–384 μm from the anterior end (Fig. 3f). At the anterior end of both sexes, an excretory pore is observed (Naem, Reference Naem2007b, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Morphology of male and female Thelazia rhodesi: (a) anterior region; (b) female posterior region; (c) male posterior region; (d) and (e) anterior region of female showing cervical papillae (CP), vulva (V), cuticular pattern around the vulva (*), and transverse striation of the cuticle (TS); (f) posterior region of male showing spicules (S), preanal papillae (PrCP), postanal papillae (PoCP) and phasmids (Ph). Adapted from: Brás (Reference Brás2012) and Naem (Reference Naem2011, Reference Naem2007c).

The females are 12–21 mm long (Brás, Reference Brás2012) and 217.9–613.8 μm wide (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023). At the anterior end of the body, the vulva is located in the oesophageal region, 762.2–1354.2 μm (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023) from the cephalic region (Fig. 3). The pattern of the cuticle around the vulva is different from that of the rest of the body (Fig. 3). At the posterior end, the anal pore is visible, and the tail end is stumpy with two phasmids near its extremity (Naem, Reference Naem2007b, Reference Naem2011). The eggs are initially 11.8–25.4 µm long, but when stretched by developing larvae, they are 31.6–47.8 µm long (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023).

The males are 9.8–17.3 mm long and 275.8–528 μm wide (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023). The tail is blunt and without caudal alae, with dissimilar and unequal spicules (Naem, Reference Naem2011) 452.7–850 and 94.5–191.3 μm long (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023), respectively, and no gubernaculum (Naem, Reference Naem2007b, Reference Naem2011). There are 14 paired preanal papillae, one single papilla directly anterior to the cloaca, one paired postanal papilla, and two phasmids at the posterior end (Naem, Reference Naem2007b, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 3) (Table 6). Thelazia gulosa Railliet and Henry, 1910. The mouth opening is rounder and larger than those of T. rhodesi and T. skrjabini. The buccal capsule is cupuliform, with its maximum diameter at the mouth opening and its minimum diameter at its base (Fig. 4). The cuticle is finely striated transversely; there is some uniformity in the distribution and shape of this striation along the surface of the parasite (Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020; Naem, Reference Naem2007a) (Fig. 4). The mouth is without lips and is surrounded by four cephalic papillae and two amphids. There are two lateral cervical papillae, one on each side (Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 4).

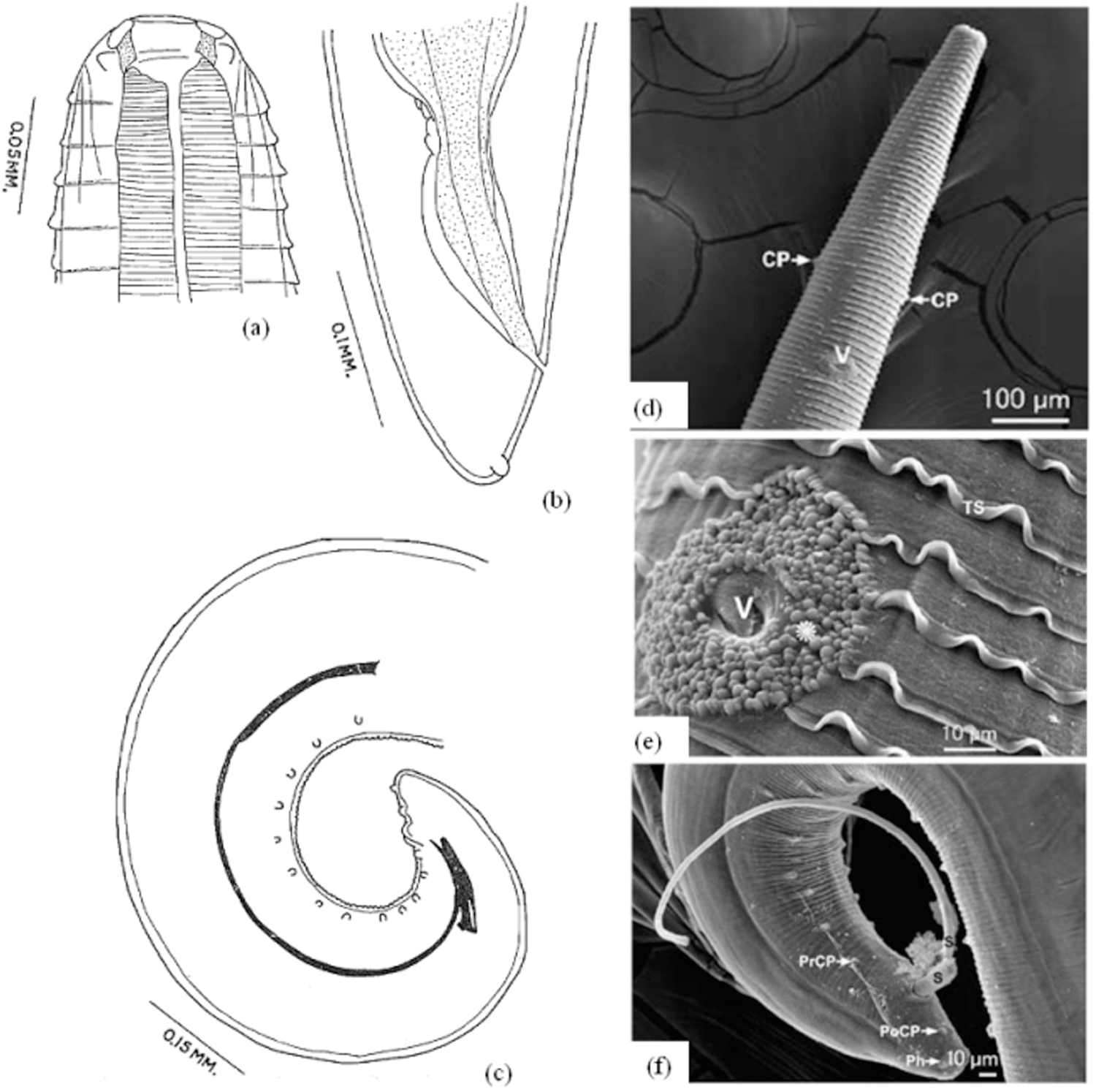

Table 6. Measured morphometric variations among the three Thelazia species in cattle

NM = Not measured;

a = Not paired (unpaired); Nerve R anterior = the distance between the midpoint of the Nerve ring and the proximal end of the oesophagus; Nerve R posterior = the distance between the midpoint of the Nerve ring and the distal end of the oesophagus.

Figure 4. Morphology of male and female Thelazia gulosa: (a) and (b) anterior region; (c) posterior region of male; (d) posterior region of male showing spicules (S), preanal (PrCP), postanal papillae (arrows), phasmid (arrowhead) and transverse striations (TS); (e) posterior region of female in ME showing anal pore (AP) and phasmids (Ph). Adapted from: Brás (Reference Brás2012) and Naem (Reference Naem2011, Reference Naem2007c).

The body of the female is thin, whitish, attenuated at ends, 16–16.6 mm long, and 534.8–706.1 μm wide at the maximum body width. The vulva is located 554.9–735.9 μm from the cephalic region, whereas the anal pore is located 65.2–141.9 μm from the posterior end of the body (Table 6). There is also one button-like subterminal phasmid on each lateral side of the female’s tail. (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023; Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 4).

The males are 7.5–8.0 mm long and 300–370 μm wide at the maximum body width (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2011). The tail is blunt, without caudal alae, and curved ventrally (Fig. 4). The number of preanal papillae ranges from 35 to 40. These papillae are unpaired, and one single papilla directly anterior to the cloaca is also present. Three pairs of postanal papillae are present (Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 4) (Table 6). The tail cuticle also has two small sensilla or phasmids (Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020). The spicules are unequal (608–1025 μm and 120–125 μm long, respectively), dissimilar and have a groove-like structure (Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2011). The nerve ring is located approximately 156–261 μm from the anterior end of the body (Demiaszkiewicz et al., Reference Demiaszkiewicz, Moskwa, Gralak, Laskowski, Myczka, Kołodziej-Sobocińska, Kaczor, Plis-Kuprianowicz, Krzysiak and Filip-Hutsch2020). There is no gubernaculum (Naem, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 4) (Table 6).

Thelazia skrjabini Erschow, 1928

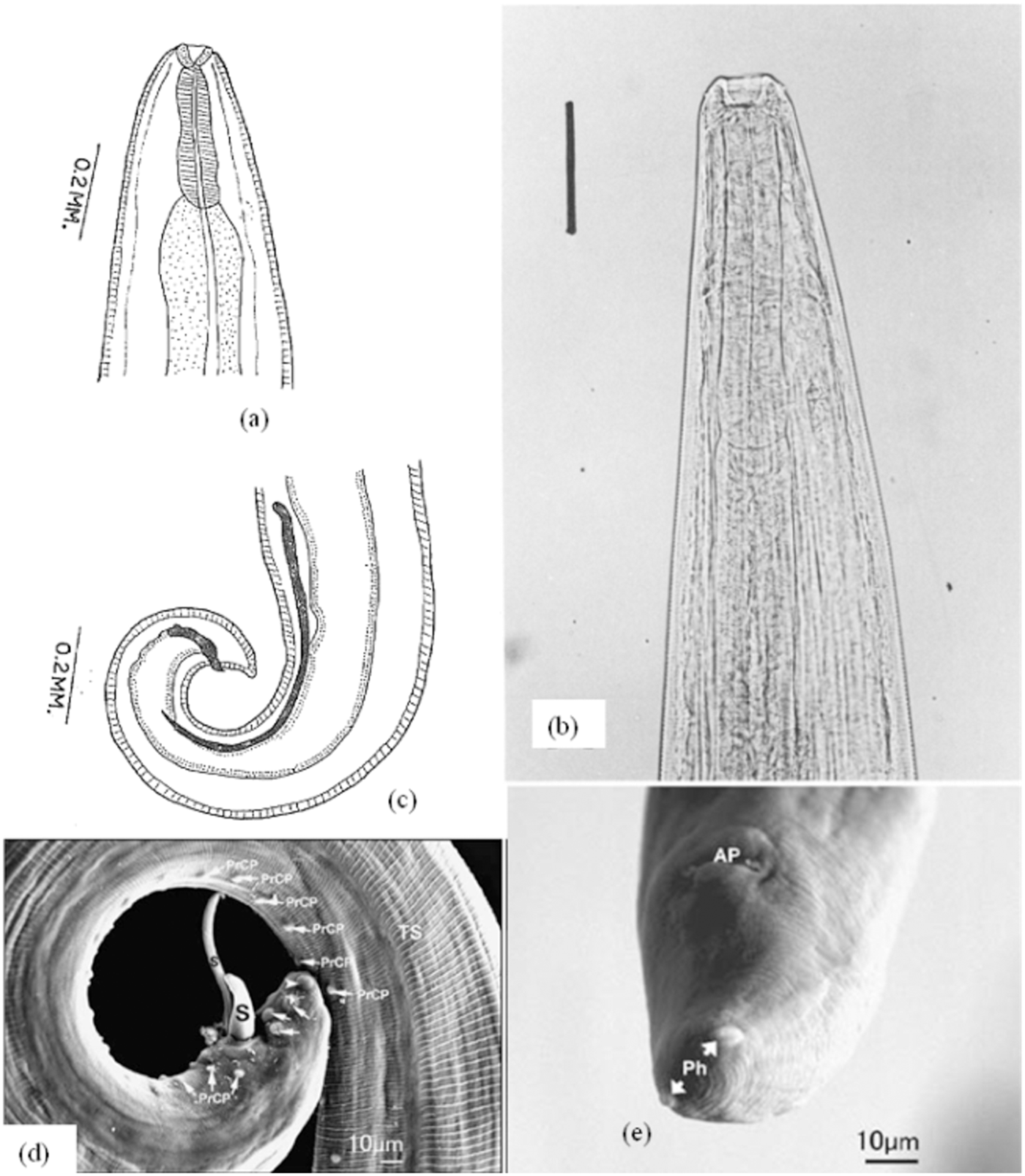

The cephalic region is similar in both sexes, and the buccal capsule is small (Brás, Reference Brás2012). The mouth is orbicular and has no lips with its anterior edge turned over and has six grooves. Around the mouth, two circles of cephalic papillae are visible: the inner circle with six papillae and the outer circle with four submedian cephalic papillae. Two amphids, one on each side of the head, are observed. The cuticle shows fine, scarcely visible transverse striations and two lateral cervical papillae (Naem, Reference Naem2007a, Reference Naem2007c, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Morphology of male and female T. Skrjabini: (a) and (b) anterior region of female; (c) female posterior region; (d) posterior region of male; (e) anterior region of female in ME showing vulva (V) and striation cuticle thin transverse (TS). Adapted from: Brás (Reference Brás2012) and Naem (Reference Naem2007c, Reference Naem2011).

The females are 9.8–18.9 mm long and 225.5–348.5 μm wide (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023) (Table 6). The vulva is located 453.1–903.4 μm from the cephalic region and protrudes. The anal pore is located 31.8–142.6 μm at the posterior end of the body, and the tail has two phasmids near the tip (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023; Naem, Reference Naem2007c, Reference Naem2011).

The males are 5.2–11 mm long and 156.1–331.2 μm wide (Cotuțiu et al., Reference Cotuțiu, Ionică, Dan, Cazan, Borșan, Culda, Mihaiu, Gherman and Mihalca2023) (Table 6). The tail is blunt, without caudal alae, and curved ventrally. There are 31–38 unpaired preanal papillae, two paired postanal papillae, and two phasmids at the posterior end. The pattern of the cuticle around the cloaca is different from that of the rest of the body (Naem, Reference Naem2007c, Reference Naem2011) (Fig. 5) (Table 6).

Transmission and vector (IH) biology

Thelazia spp. requires a vector, which also acts as an IH, to complete its life cycle (Brás, Reference Brás2012). The IHs of several Thelazia spp. are known, and in each case, they are non-penetrate secretophagic dipteran flies of the genera Musca (family Muscidae), Phortica (family Drosophilidae), or Fannia (family Fanniidae) (Mupper-san, Reference Mupper-san2023). These flies feed on tears or lachrymal secretions of their DHs, including humans (Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Nimir et al., Reference Nimir, Saliem and Ibrahim2012).

Musca autumnalis, also called the face fly, was the first to be identified as an IH and a vector of bovine thelaziasis (Klesov, Reference Klesov1950; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990; Brás, Reference Brás2012; Hicks and Lomond, Reference Hicks and Lomond2024). This has become recognized as the main responsible for the transmission of the nematode in various parts of the world, with significant documentation emerging from Russia, followed by southern Europe, and subsequently in North America and Australia (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Giangaspero et al., Reference Giangaspero, Traversa and Otranto2004; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990; Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997). The inevitable interspecific relationship between the genus Thelazia and the vector Muscida makes it advantageous to know the biology and phenology of this vector (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

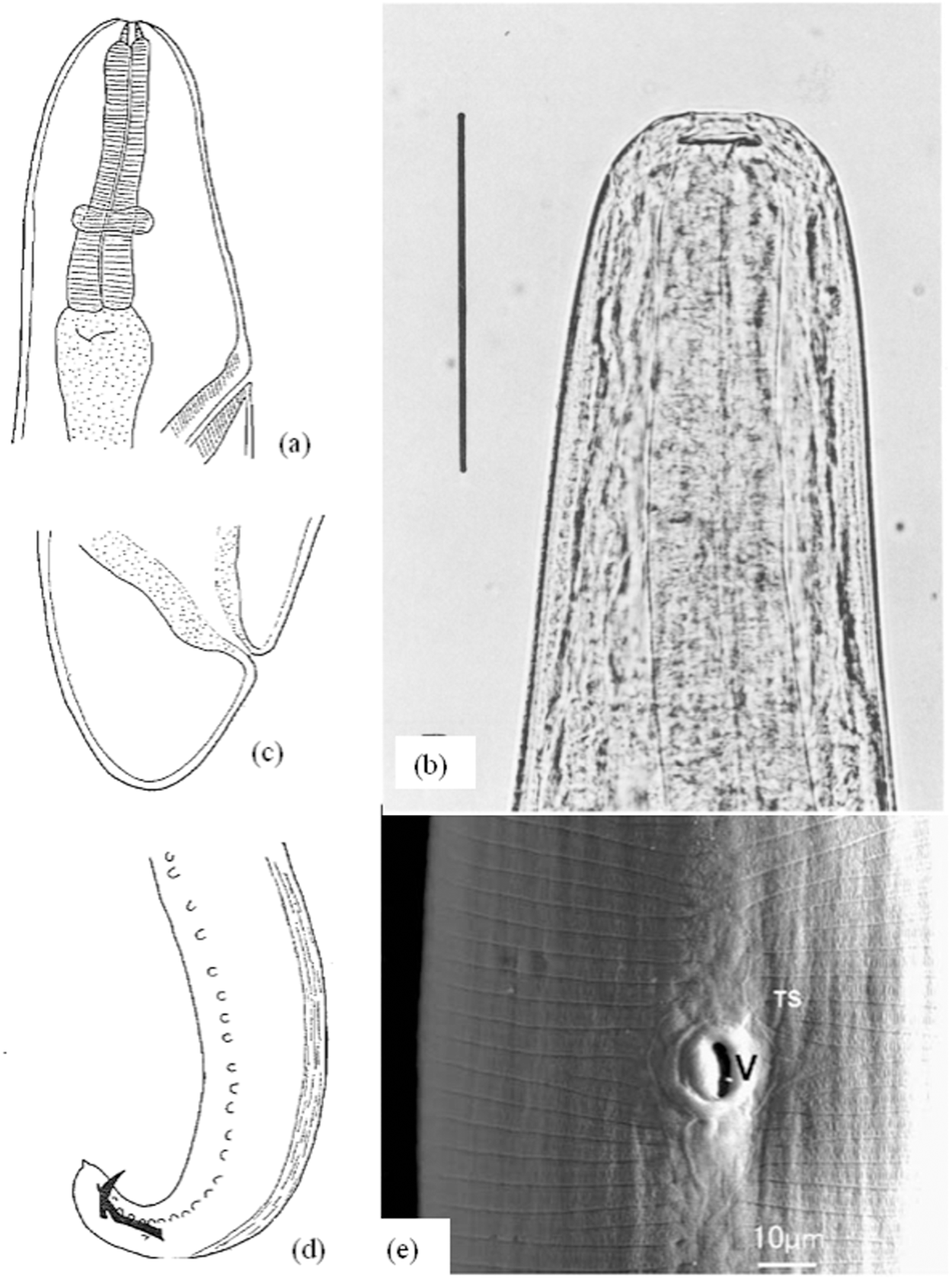

The face fly (Fig. 6a) is similar to its ‘relative’ house fly (Musca domestica), with a slightly larger and darker body. The predilection of M. autumnalis to congregate around the faces of grassland animals also helps distinguish them (Campbell, Reference Campbell1994; Zubairova and Ataev, Reference Zubairova and Ataev2010; Zurek, Reference Zurek2004) (Fig. 6b). In fact, unlike the house fly, which lives up to its name and prefers the interior of houses, adult M. autumnalis avoid buildings during the summer. This includes leaving the dairy cows when they enter the barn (shed) for milking, preferring to wait outside and crowding around the animals again when they appear (Bowman, Reference Bowman1999; Brás, Reference Brás2012).

Figure 6. Musca autumnalis (a) and face flies feeding on the eye of a cow (b). Adapted from: Otranto (Reference Otranto2024).

Face flies can hibernate by suppressing oogenesis in adults in a period called pre-reproductive diapause. The hibernating flies re-emerge in mass in the spring, at a time determined by the sum of hours in which the ambient temperature has remained above 12°C since the beginning of the year (Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021). After a short reproductive period, females disperse to pastures to obtain protein. Flies are capable of flying considerable distances, up to several kilometres; however, they tend to remain in the vicinity of cattle (Zubairova and Ataev, Reference Zubairova and Ataev2010; Zurek, Reference Zurek2004). This is because females prefer blood and eye secretions from animals as sources of protein, despite being able to support vitellogenesis from other substrates (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021). Eggs deposited in manure trails from cattle constitute the first generation of spring flies, occurring between March and May in North America. The gonadotropic cycle is completed in 1–4 weeks and is determined by the temperature (>12°C) and nutritional status of the females. Eggs are deposited on the surface of fresh manure left in cattle tracks, where they are vulnerable to thermal stress, drowning by heavy rains and predation by other insects. Development from eggs to adults takes at least 11 days, with an average of approximately 14 days, depending on the ambient temperature (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Lifecycle of the genus Musca. Source: Authors (2025).

The number of flies normally increases until it reaches a seasonal maximum in the final phase of the summer season, when the autumn diapause begins to manifest itself at the end of the reproductive season (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Chirico, Sandelin and Mullens2015; Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985). However, the timing of this phenomenon is region dependent, with some studies indicating it occurs in late spring and early autumn, while others suggest in early summer and mid-autumn (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Chirico, Sandelin and Mullens2015). Females live an average of 11 days in summer, and multiparous flies can be found until mid-October, although they have become increasingly rare since mid-September. Females destined for diapause become adults at the end of the summer, with no ovarian development occurring, but rather an accumulation of fat in preparation for hibernation (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Chirico, Sandelin and Mullens2015; Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985). These flies remain nulliparous throughout the winter, as diapause causes behavioural changes that lead to the absence of copulation, and consequently, they stop looking for cattle to feed themselves (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021).

Studies have demonstrated that any stage of a fly can survive brief exposures at temperatures between −7°C and 0°C, as can happen on frosty autumn mornings or spring. However, only adults in diapause can tolerate temperatures below −8°C for a few hours, and these adults are unable to survive more than a day at temperatures below −8°C (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997). Therefore, hibernation sites must have protective features from thermal extremes, such as barns, houses and other buildings, and protected areas abroad. In fact, flies tend to hibernate in the same locations year after year (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Campbell, Reference Campbell1994; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Chirico, Sandelin and Mullens2015).

In addition to the species of M. autumnalis, in some cases, M. domestica, M. larvipara and M. amica are thought to transmit bovine thelaziosis when they feed on the tears of cattle (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014) (Table 1). On the other hand, Phortica variegata and Phortica okadai are the primary IHs for T. callipaeda. Interestingly, only males of P. variegata were found to be infected with T. callipaeda under natural conditions. Musca domestica (a common fly) is not a vector of T. callipaeda (Das et al., Reference Das, Das, Deshmukh, Gupta, Tomar and Borah2018; Naem, Reference Naem2011; Otranto and Dutto, Reference Otranto and Dutto2008). Fannia spp. such as F. benjamini (canyon fly) and F. canicularis (lesser house fly) are IHs for T. californiensis in its DHs (Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Naem, Reference Naem2011; Otranto and Dutto, Reference Otranto and Dutto2008) (Table 1).

Biology and life cycle

The biological characteristics of these parasites suggest that thelaziasis is transmitted indirectly from an infected animal (source of parasites) to a healthy individual (receptive) (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

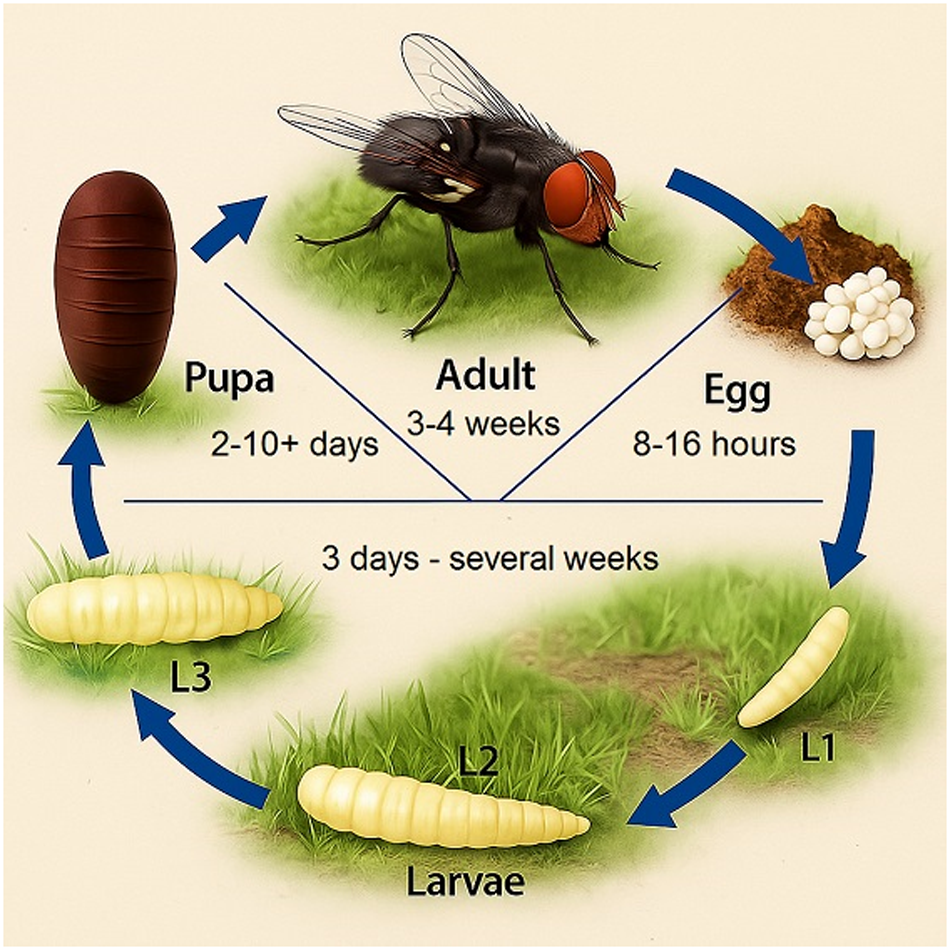

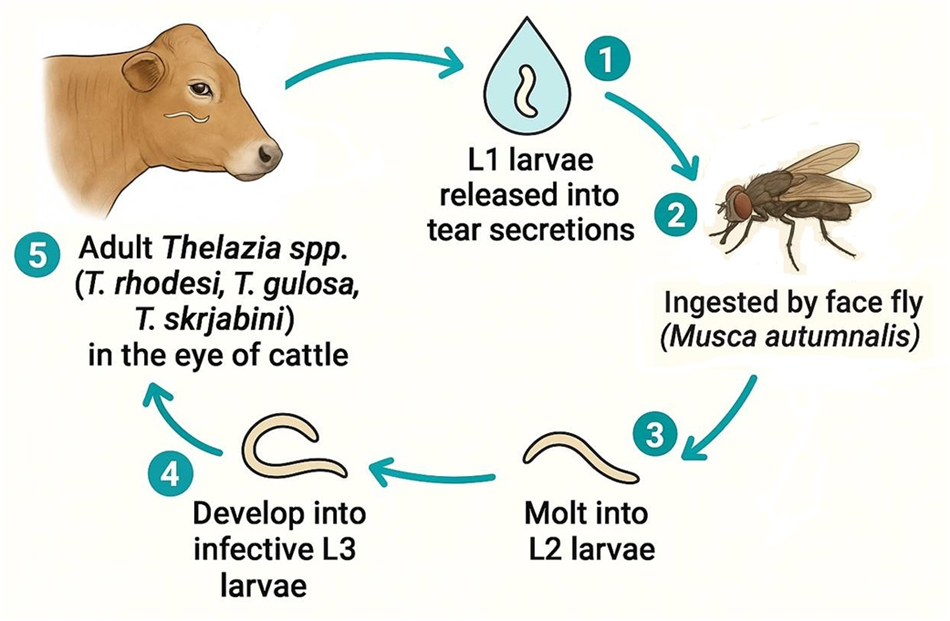

Adult nematodes of the genus Thelazia inhabit the eye socket, where they live and thrive (reproduce). Females are viviparous, producing many thin-shelled eggs that embryonate in utero, becoming L1 larva that are completely differentiated and active (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; CDC, 2019; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Euzéby, Reference Euzéby1961; Naem, Reference Naem2011; Neveu-Lemaire, Reference Neveu-Lemaire1936) (№ 1 of Fig. 8). Females deposit L1 larvae in host tear secretions, which are subsequently ingested by dipteran insects by feeding on the host’s ocular secretions, tears and conjunctiva (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Naem, Reference Naem2011; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2004) (№ 2 of Fig. 8). The first larval stage of Thelazia involves a very short survival time in tear secretions, only a few hours, so transmission depends on the continuous presence of vectors (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). Once ingested and in the digestive tract of the IH, L1 larvae become ex-sheathed and invade various host tissues, including the fat body, testis, and egg follicles, where they develop into capsules (CDC, 2019; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014). More specifically, L1 larvae penetrate the intestine within one to four hours post infection (PI) and enter the fly hemocoelium (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). The way in which this process occurs is unknown; however, Geden and Stoffolano (Reference Geden and Stoffolano1982) suggested the action of digestive enzymes, which appears to be supported by the characteristics observed by O’Hara and Kennedy (Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991) via electron microscopy. Later, the authors reported the presence of an opening in the cephalic end of L1 larvae of T. skrjabini under a ventral hook, whose function is unknown. However, they hypothesize that this opening leads to a secretory gland of enzymes that, together with the caudally directed hooks (two dorsal and one ventral), allow penetration of the intestine (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

Figure 8. Life cycle of Thelazia. Source: Authors (2025).

In the hemocoelium, L1 larvae invade certain abdominal sections, remaining there encapsulated and undergoing two molts until they become infective L3. The L1 larvae of T. rhodesi were documented to be encysted in the ovarian follicles of flies, reaching the infectious stage between 15 and 30 days PI (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). However, Miyamoto et al. (Reference Miyamoto, Shinonaga and Kano1974) detected active T. rhodesi infection of L3 at 60, 15 and 12 days PI at 20, 25 and 30°C, respectively (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). These results demonstrate how development inside the fly is temperature dependent. Thelazia skrjabini capsules are mostly found in the abdomen, more precisely, in body fat, requiring at least 9 days PI (average of 16 days) for infective larvae to form under experimental conditions of 27°C (O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991). For the species T. gulosa, the parasite’s capsules adhere closely to the abdominal wall of the vector (Geden and Stoffolano, Reference Geden and Stoffolano1982; O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991), with infective L3 developing within approximately 9 days PI under laboratory conditions maintained at 28–30°C.

The infective L3 break (№ 3 of Fig. 8), free from the capsule, and migrate anteriorly to the proboscis of the fly—so that when the fly feeds, the L3 larvae crawl from the proboscis to the eye of the new host, and continue the cycle (CDC, 2019; Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990) (№ 4 of Fig. 8). Compared with the L3 larvae of T. rhodesi, which measure 6.7–7.5 mm in length and 160–180 µm in width, the L3 larvae of T. skrjabini and T. gulosa, which are approximately the same length (2.1–2.86 and 2.1–2.5 mm, respectively) and are 89–110 µm wide for T. gulosa, are larger than the 64–82 µm wide for T. skrjabini (Kennedy and MacKinnon, Reference Kennedy and MacKinnon1994; O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991). The latter species exhibits distinct longitudinal striations, with cuticular ridges extending along approximately ½ to ⅔ of the body length. The oesophagus measures 180–220 µm in length and the genital primordium is located 47–76 µm from the anterior extremity (Naem, Reference Naem2011; O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991). Several authors report a predilection for certain locations on the eyeball specific to each species of Thelazia (Arbuckle and Khalil, Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978; Kennedy and MacKinnon, Reference Kennedy and MacKinnon1994; Naem, Reference Naem2011). The L3 larvae of T. rhodesi are likely too long and wide to penetrate ducts; hence, their location tends to be on the ocular surface. For T. gulosa and T. skrjabini, the factors that define the locations occupied by these nematodes are unknown; as they appear to develop equally well in any tear duct they can penetrate. Muscid vectors feed mainly in the medial corner of the eye; therefore, most L3 larvae are deposited medially rather than laterally. Thus, the displacement of larvae along the eye, i.e., the upper diameter of T. gulosa L3, probably makes it more difficult for them to move under the nictitating membrane than along the conjunctival sac. Thus, nematodes of the species T. gulosa are more prevalent in the tear ducts, whereas T. skrjabini is more prevalent in the ducts of the Harderian gland (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

When the cycle ends without further migration, L3 larvae molt to L4 and later reach the adult stage (L5) (Fig. 8) (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Humans may also serve as aberrant DHs following exposure to an infected fly IH in the same manner (CDC, 2019). The prepatent period for T. rhodesi varies between 20 and 25 days, whereas that for T. gulosa is only 7 days (Klesov, Reference Klesov1950).

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of bovine thelaziasis depends on the existence of a receptive (susceptible) DH; grazing pasture and animal management; the presence, biology, and aetiology of flies that act as IHs; and environmental variables and meteorological factors (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016).

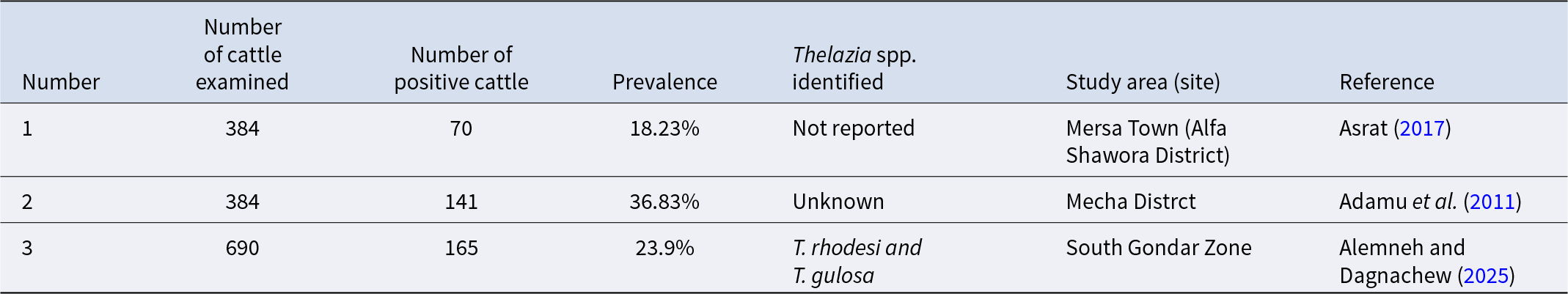

Distribution

Thelazia is a cosmopolitan parasitic genus; thus, the species responsible for bovine thelaziasis are widely distributed in parts of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North America and South America (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005; van Aken et al., Reference van Aken, Dargantes, Lagapa and Vercruysse1996) (Tables 1 and 2).

Molecular studies revealed a strong genetic affinity between T. skrjabini and T. gulosa, with their nucleotide sequences showing markedly greater similarity to each other than to those of T. rhodesi. These data suggest the existence of a close relationship between T. skrjabini and T. gulosa, which is consistent with the similarity of characteristic morphology between the two (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Furthermore, epidemiological studies have revealed a worldwide distribution of T. rhodesi, with a special emphasis on the Old World or Palearctic region, and have been reported from Japan, the USA, Canada, the UK, Italy, Afghanistan, Iran, Ghana, Zambia, and Ethiopia. On the other hand, T. skrjabini and T. gulosa are primarily found in the New World, with occurrences noted in the northern USA, Canadian provinces, Asia, Australia, and Europe (Adamu et al., Reference Adamu, Bogale, Chanie, Melaku and Fentahun2011; Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025; Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016; Naem, Reference Naem2011; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005; Bot, Reference Bot2021) (Table 1). However, recent findings have confirmed the existence of T. gulosa in Old World regions, notably in Iran (Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016) and Ethiopia (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025). The climate of the countries in which T. gulosa and T. rhodesi have been reported varies from tropical and subtropical in the Far East to temperate in the Russian Federation (Khedri et al., Reference Khedri, Radfar, Borji and Azizzadeh2016) (Table 1). In fact, T. gulosa and T. skrjabini were accidentally introduced to continental America after World War II with the introduction of one of its vectors, the facial fly M. autumnalis (Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Breen, Bonura, Hoyt and Bishop2018, Reference Bradbury, Gustafson, Sapp, Fox, De Almeida, Boyce, Iwen, Herrera, Ndubuisi and Bishop2020).

Like the other Spirurids, Thelazia spp. exist in all hot and temperate countries and favour the IH insect life cycle of the parasite. Musca autumnalis is endemic to temperate latitudes of Europe, North Africa, Central Asia and North America; subspecies of M. autumnalis are also isolated in East Africa. Miscellaneous Musca species, such as M. amita, M. osiris, M. sorbens, M. vitripennis and M. larvipara, which occur largely within the geographic range of M. autumnalis, are sympatric with face flies in temperate regions (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021).

According to Euzéby (Reference Euzéby1961), in tropical and subtropical countries, the parasite persists in all seasons, unlike temperate countries, where infection in cattle presents seasonal characteristics, tending to manifest itself in summer, a season with an abundance of flies. This notion appears to contradict findings from Zambia and Ethiopia—both countries in tropical high-altitude regions as well as the Philippines, which has a monsoon climate. In a study carried out in Zambia by Ghirotti and Iliamupu (Reference Ghirotti and Iliamupu1989), differences were documented between the total prevalence of T. rhodesi in cattle in the dry (3.1%, n = 223) and rainy (26.6%, n = 248) seasons. The authors attributed these observations to climatic conditions that are more favourable for the survival of IHs in the rainy season, between November and February, than in the dry season, when low relative humidity inhibits the development of Muscids. Similarly, in the Philippines, the incidence of infection was significantly greater in the period between May and July and was lower in the months from February to April and from August to October, although Muscids find suitable environmental conditions throughout the year (van Aken et al., Reference van Aken, Dargantes, Lagapa and Vercruysse1996). In Ethiopia, Alemneh and Dagnachew (Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025) also demonstrated seasonal variations in thelaziasis among cattle, with infection rates peaking sharply in autumn, even though humidity and temperature conditions remain conducive for IH survival and reproduction throughout most of the seasons.

At the regional level, several trials have demonstrated that the prevalence of Thelazia spp. in cattle is associated with topographic and environmental factors (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1993; Zubairova and Ataev, Reference Zubairova and Ataev2010). The regional occurrence of Thelazia in cattle and Muscids depends on the distribution of infected cattle, the dispersion of infected flies and the capacity of a region to support the fly population. The last two are, in turn, limited by the type of pasture or regional habitat, which affects the distribution and abundance of vectors, such as M. autumnalis (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1993). Adult flies are not randomly distributed throughout pastures but rather prefer valleys close to watercourses and up to 10 meters from places of rest for cattle (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1993; Pickens and Nafus, Reference Pickens and Nafus1982; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021). Notably, the flies visible on cattle at any given time are predominantly females, which represent less than 5% of the total female population in the vicinity of the herd. This value demonstrates how the length of stay in animals is short and the turnover is quite fast. The proportion of flies in cattle is influenced by gonadotropic status, meteorological weather, and the behaviour and location of cattle (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997).

In Canada, Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1993) reported a significantly greater number of cattle infected with Thelazia spp. in forest areas (18.4%) and coarse vegetation with some shrubs (11.3%), whereas cattle in open pastures of low and medium grass had the lowest prevalence of infection (0% and 1.5%, respectively). The cattle in open, dry pastures tend to have fewer flies than cattle in pastures with shade and water sources (tanks, lakes and streams). The presence of manure trails of cattle along watercourses or in the shade of vegetation will allow the fly’s life cycle to be completed; in contrast, on manure tracks in open areas, the manure will dry before the larvae complete their development to the adult stage (Campbell, Reference Campbell1994; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Chirico, Sandelin and Mullens2015; Trout Fryxell et al., Reference Trout Fryxell, Moon, Boxler and Watson2021).

The authors of Zubairova and Ataev (Reference Zubairova and Ataev2010) described cattle with decreasing levels of infection between plain (38%), sub-mountain (20%) and mountain (5%) zones in Russia. These results are in agreement with studies from the early 1960s (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1993; Világiová, Reference Világiová1968), which noted the association between wooded plains and a high prevalence of Thelazia spp. Additionally, recent LIDAR-based GIS studies by Sommerfeld et al. (Reference Sommerfeld, Crawford, Monahan and Bastigkeit2019) indicated that this association is primarily linked to altitude. Higher elevations and mountainous regions tend to experience increased wind speeds and turbulence, creating less favourable habitats for flying insects. Further, the lower temperatures found at these high altitudes typically result in reduced activity among flies, leading to a decrease in both the speed and direction of their flight patterns.

Thelazia species and intermediate host relationships

As already discussed, the presence of Thelazia spp. depends on factors that control the existence of IH, that is, the presence of suitable habitats and suitable environmental conditions. Several species of flies of the genus Musca have already been identified as suitable vectors, partly because they present risky eating behaviours, feeding on secretions of the eyes of animals or humans, as well as fruits and tree saps (Brás, Reference Brás2012). Depending on the geographical region and atmospheric conditions considered, certain fly species are involved in the transmission of bovine thelaziasis (listed in Table 1). Microscopic dissection of infected flies and morphological identification of the larvae collected have been the most commonly used techniques for detecting infection in vectors (O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). However, this technique presents constraints (for example, low sensitivity and the need for well-trained operators, among others), which, associated with the low prevalence and intensity of infection in flies, can lead to underestimation of the numbers of parasites present. The morphological identification of larvae in terms of the species of Thelazia is only possible by comparison with larvae collected from infected flies in the laboratory (Otranto et al., Reference Otranto, Tarsitano, Traversa, Giangaspero, De Luca and Puccini2001). Therefore, few epidemiological investigations of bovine thelaziasis under IH exist, and these few investigations have been carried out in North America and the former USSR (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Klesov, Reference Klesov1950; O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991).

The transmission of thelaziasis begins in spring and continues until autumn (in a temperate climate). In North America, flies that are in reproductive diapause or dedicated to diapause in autumn and winter do not exhibit Thelazia larvae; consequently, nulliparous post-diapause flies in spring also generally do not demonstrate any infection. Therefore, it can be inferred that Thelazia spp. do not hibernate in facial flies but that the infection persists in the eyes of cattle during the winter (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985).

The first capsules of larval forms of Thelazia in flies are detected with the appearance of flies that give birth in spring, and the proportion of infected flies then increases in proportion to the population of multiparous flies. It has been verified that only flies that have fed on bovine secretions and live to lay eggs are infected (Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985). Flies lay eggs every 1–4 weeks and feed on animal secretions repeatedly between egg depositions. Frequent feeding thus favours the dispersion of nematodes throughout the cattle herd, leading to older flies having more contacts with potentially infected cattle (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1994; Moolenbeek and Surgeoner, Reference Moolenbeek and Surgeoner1980). The authors of Krafsur and Moon (Reference Krafsur and Moon1997) reported a prevalence of infection in multiparous female flies of 1.8% in May and 3.8% in June, suggesting that Thelazia females in DH are excreting L1 larvae when post-diapause flies become active.

Infected flies are found until the end of September and October; however, these flies are multiparous breeders, old and unable to hibernate (Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985). The fact that L4 larvae of Thelazia are generally found in cattle between July and November indicates the cessation of transmission in autumn, which can be explained by the diapause that stops flies from feeding on cattle (Krafsur and Moon, Reference Krafsur and Moon1997; Moolenbeek and Surgeoner, Reference Moolenbeek and Surgeoner1980).

As already mentioned, the size of a Muscid population is influenced by changes in the environmental temperature. In fact, the analysis of any study must consider variations in average temperature during the hot season of the year prior to the study, which may influence the number of flies that hibernate and therefore the number of adult flies at the start of the following year. It follows that any reference to month-specific aspects of fly biology must be applied carefully in practice (Tweedle et al., Reference Tweedle, Fox, Gibbons and Tennant2005).

An investigation carried out by Giangaspero et al. (Reference Giangaspero, Traversa and Otranto2004) in Italy, using molecular techniques, allowed clear results without the constraints associated with dissection and identification of vectors and larvae. Using PCR, the authors specifically identified the presence of T. gulosa in M. autumnalis, M. larvipara, M. osiris and M. domestica and T. rhodesi in M. autumnalis and M. larvipara. The maximum average prevalence values of infection were obtained for M. autumnalis (4.46%) and M. larvipara (3.21%). However, Geden and Stoffolano (99) reported that M. domestica was infected with nematodes of Thelazia spp. and that there were no signs of a host immune response, indicating that this species is an inappropriate IH. This is an indication of the limitations of any PCR or molecular biology, in which, if the IH has come into contact recently with the larvae, particularly through ingestion, despite it not being a suitable IH for that larvae, it will come out positive in the PCR test. The average number of nematodes found is 2.3–3.1 larvae per infected fly (Geden and Stoffolano, Reference Geden and Stoffolano1981; Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985; Moolenbeek and Surgeoner, Reference Moolenbeek and Surgeoner1980), and the prevalence of Thelazia spp. estimated in fly populations varies between 0.4% and 13.2% (Geden and Stoffolano, Reference Geden and Stoffolano1981; Giangaspero et al., Reference Giangaspero, Traversa and Otranto2004; Klesov, Reference Klesov1950; Moolenbeek and Surgeoner, Reference Moolenbeek and Surgeoner1980).

Thelazia species and definitive host relationships

Bovine thelaziasis is the most prevalent type of thelaziasis, probably because of the susceptibility of cattle to parasitism and because animals in open pastures are more exposed to Muscid vectors compared to other animals, such as carnivores (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005).

The seasonality of infection by Thelazia spp. has been reported by several authors (Klesov, Reference Klesov1953; Arbuckle and Khalil, Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978; Brás, Reference Brás2012; Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025). Despite the presence of adult nematodes in cattle throughout the year, a pattern can be seen in the dynamics of parasitism, with a maximum prevalence at the end of summer (Arbuckle and Khalil, Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978; Brás, Reference Brás2012) or in autumn (Alemneh and Dagnachew, Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025) owing to the emergence of new adults from larval forms transmitted by vectors in early summer (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). This peak is sometimes preceded by a sharp decrease in parasitism due to the death of adult nematodes that reside in the DH eye during the winter (Klesov, Reference Klesov1953). Since Muscids are only active between spring and the end of summer, the opportunities for infection of cattle are limited to this period, implying that parasite longevity in DH is 6 months or more (Tweedle et al., Reference Tweedle, Fox, Gibbons and Tennant2005). In fact, Petrov et al. (Reference Petrov, Gaibov and Gagarin1940) report the survival of the nematode in cattle is approximately 9–10 months. To denote also the experiments carried out by Iamandi and Teclu (Reference Iamandi and Teclu1937), demonstrating that the survival of L1 larvae in physiological saline solution is very short (a few hours) and is likely equally short in DH tear secretions. Thus, transmission depends on the continuous presence of vectors in an infected environment to ingest L1 larvae before their natural death (Kasarla et al., Reference Kasarla, Adhikari, Ghimire and Pathak2021; Naem, Reference Naem2011; van Aken et al., Reference van Aken, Dargantes, Lagapa and Vercruysse1996). In this way, periods of the presence or absence of immature and adult nematodes in DH eyes may vary annually depending on whether climate conditions affect IH (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

In the United Kingdom, Arbuckle and Khalil (Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978) reported an increase in the prevalence of infection in cattle from the end of June, July and August. At the beginning of summer, the number of immature stages of Thelazia in cattle increased simultaneously with the disappearance of adults, suggesting that the development process of larval forms would cause death or expulsion of the adult population of the previous year (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

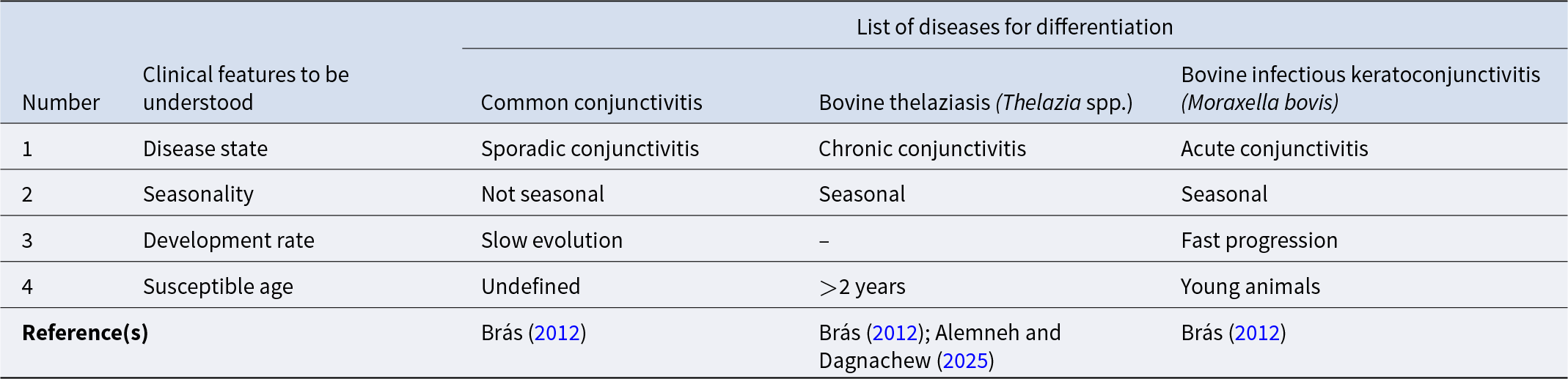

In Ukraine, Klesov (Reference Klesov1950) reported that conjunctivitis in animals infected by Thelazia coincides with the death of adult nematodes and infection by new individuals. Ikeme (Reference Ikeme1967) also speculating that the death of nematodes can lead to secondary bacterial infections which, associated with physical trauma produced by immature forms, would cause eye damage (O’Hara and Kennedy, Reference O’Hara and Kennedy1991). Similarly, in France, clinical signs of infection manifested themselves in June. The maximum extent of thelaziasis occurred from July to September, regressing in October and disappearing in winter (Euzéby, Reference Euzéby1961). The evidence thus points to an association between outbreaks of eye disease and fly activity in the warm season (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990). However, it is essential to rule out the possibility that other agents transmitted by flies, such as Moraxella bovis, are also involved in the observed ocular changes (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014).

Infection with Thelazia spp. depends on the existence of receptive DHs. Early studies demonstrate that the prevalence of infection does not appear to be affected by the sex, breed or function (e.g., meat vs. milk) of the animals (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990 ). However, a more recent study by Alemneh and Dagnachew (Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025) suggests that breed may indeed serve as a predictor factor for the disease. Surprisingly, researchers are very consistent regarding the correlation between the age of cattle and the presence of infection by Thelazia spp., although age groups show a divergent maximum prevalence. The authors van Aken et al. (Reference van Aken, Dargantes, Lagapa and Vercruysse1996) report a higher infection rate among animals older than 36 months, while Arbuckle and Khalil (Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978) report ages between 21 and 38 months with the highest infection rate. Additionally, Alemneh and Dagnachew (Reference Alemneh and Dagnachew2025) indicate that cattle older than two years exhibit a higher incidence of Thelazia infections. Furthermore, the consensus among researchers’ is that adult cattle, tending to be over 2 years of age, have a higher prevalence compared to young animals (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990; Krafsur and Church, Reference Krafsur and Church1985; Ladouceur and Kazacos, Reference Ladouceur and Kazacos1981). These findings seem to indicate that cattle do not develop resistance against this parasite. The increase in prevalence with age could be the result of increased opportunities for infection throughout the animal’s life, combined with a long period of survival of these nematodes in the eye and the likely absence of a protective immunological response of the host (Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005; van Aken et al., Reference van Aken, Dargantes, Lagapa and Vercruysse1996).

In terms of the intensity of infection, that is, the number of nematodes present in infected animals, age and sex do not appear to be significant sources of variation (Brás, Reference Brás2012). In contrast, Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Moraiko and Goonewardene1990) reported more nematodes in beef cattle (6.2 ± 1.35 nematodes) than in dairy cattle (0.27 ± 2.22 nematodes). The authors justify this finding with differences in management between beef and dairy cattle, as beef herds are normally more bothered by flies than are dairy cattle. This is partly justified by the absence of dairy cows from pastures twice a day due to milking. As M. autumnalis is rarely observed indoors, little transmission of Thelazia during milking is likely. One would expect that beef cattle would present more clinical signs than dairy cattle; however, the authors did not report the presence or absence of ocular changes in either group (Brás, Reference Brás2012).

The evolution of results obtained in studies carried out from 1975 to 2005 indicates a decreased prevalence of Thelazia spp. in cattle, as well as the maximum number of nematodes collected from infected animals or eyes (see Table 2). This was especially evident in two studies carried out at the same abattoir in Surrey, South England, with a 30-year interval (Arbuckle and Khalil, Reference Arbuckle and Khalil1978; Tweedle et al., Reference Tweedle, Fox, Gibbons and Tennant2005). The results obtained in 1976 revealed the presence of nematodes of the species T. gulosa and T. skrjabini in 41.9% (n = 237) of the cattle examined. The infected eyes hosted an average of 10.4 nematodes (between 1 and 170 nematodes), and ocular lesions were observed in 4.3% of the infected eyes. However, in the same slaughterhouse in 2004, 1.5% (n = 3) of the cattle of the same species of Thelazia were examined, a value significantly lower (P < 0.001) than that reported in 1976. In fact, infected eyes contained between 1 and 4 nematodes, and no ocular lesions were associated with the presence of this parasite. This marked decline in all fields investigated could be directly associated with the introduction and subsequent generalization of insecticides in cattle production since the early 1980s, especially considering that ivermectin and doramectin are highly effective against Thelazia species.

In contrast, epidemiological and molecular results from studies conducted between 2010 and 2025 show an increasing prevalence of Thelazia spp. in bovines, along with a rise in the maximum number of nematodes collected from infected animals or eyes, as well as greater infection severity (see Table 2). This trend is believed to be influenced by several factors, including rising environmental temperatures that favour IHs, the introduction of IHs into previously unaffected areas, and the movement of animals across international borders. Additionally, genetic drift among fly IHs, their ability to thrive at higher altitudes, and inadequate treatment protocols, such as the irregular use of macrocyclic lactones for deworming, contribute to the issue. The lack of effective disease and vector monitoring strategies, the rearing of genetically susceptible breeds, shared grazing areas with wildlife, and the sympatric presence of IH flies further exacerbate the situation. Moreover, increasing epidemiological studies in previously unexplored regions, along with the introduction and advancement of diagnostic methods such as molecular techniques, have played a role.

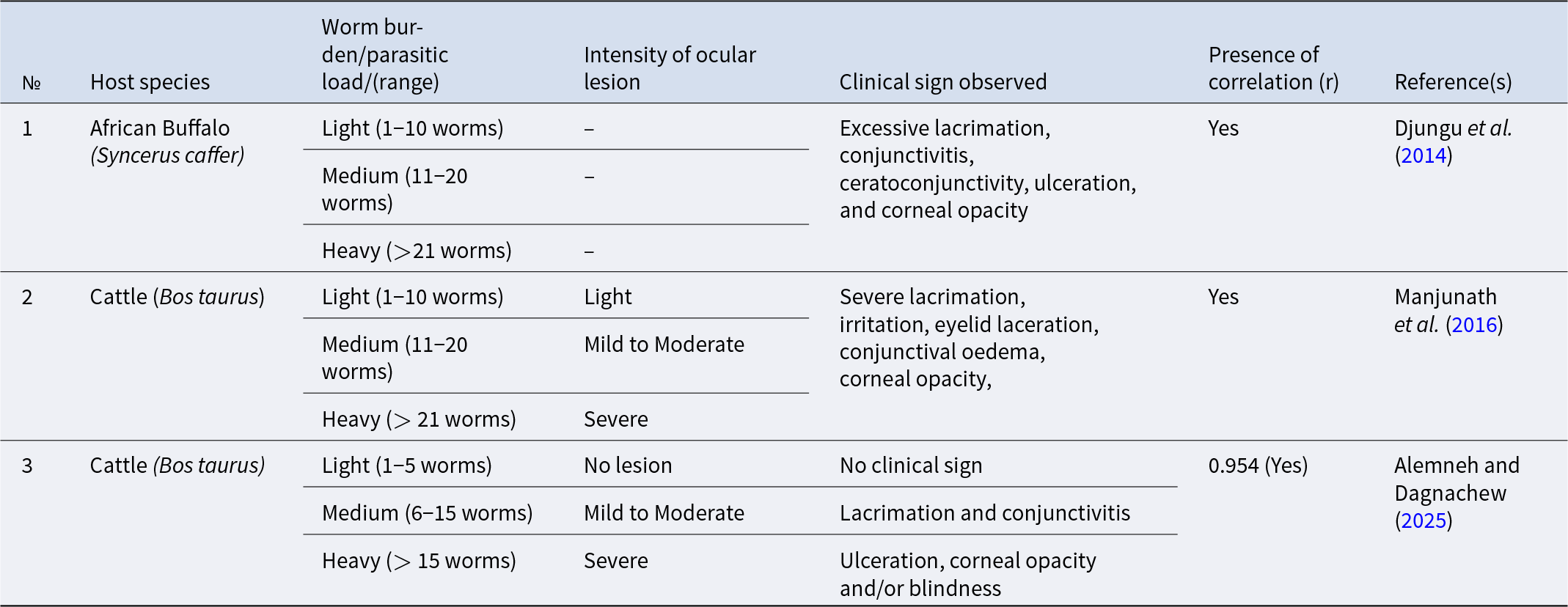

Pathogenesis and pathology

Although adult Thelazia species dwell in the orbital cavity (in the nictitating membrane, lacrimal and naso-lacrimal ducts and on the surface of the conjunctiva), in many cases, eyeworms have practically no pathogenic effect on the host, especially in larger animals. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that parasites cause disease of the eye (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014).

The pathogenic mode of action of the genus Thelazia is based on locomotory movements carried out by parasites on the surface of the conjunctiva, which are mainly mechanical and irritable to tissues (Brás, Reference Brás2012). The striated cuticle of Thelazia species causes mechanical trauma to the conjunctiva and corneal epithelium, resulting in excessive tear production, thus favouring the transmission of the parasite to attract Muscids that feed on tear secretions containing L1 larvae (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Otranto and Traversa, Reference Otranto and Traversa2005). Mechanical injuries, if present, may also be predisposing factors for secondary bacterial infections, such as Moraxella bovis, the causative agent of bovine keratoconjunctivitis, also called ‘pinkeye’ (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Junquera, Reference Junquera2022). Owing to their ability to function as entry points for microorganisms, nematodes can cause worsening of initially innocuous eye injuries. In this context, T. rhodesi, whose cuticle is coarse and has distinctly transverse striations, is naturally more pathogenic than the remaining species, whose cuticles are only slightly striated (Brás, Reference Brás2012; Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Otranto, Reference Otranto2024). However, invasion of the lacrimal gland and excretory ducts, typical of T. gulosa and T. skrjabini, can cause inflammation and necrotic exudates (Chanie and Bogale, Reference Chanie and Bogale2014; Deepthi and Yalavarthi, Reference Deepthi and Yalavarthi2012; Otranto, Reference Otranto2024).