MORAL PHILOSOPHY AND PSYCHOLOGY IN BIOETHICS AND BUSINESS ETHICS

Bioethics and business ethics are two of the most established areas of applied ethics, distinguished by ancient roots (e.g., Dittmer, Reference Dittmer2024), recent disciplinary origins (e.g., Callahan, Reference Callahan1973; DeGeorge, Reference DeGeorge2024), the emergence of formal bodies of scholarship (e.g., Bowie, Reference Bowie2000; Jonsen, Reference Jonsen and Khushf2004), and recognition in practice (e.g., Ethics and Compliance Initiative, 2024; The Hastings Center, 2024). Both disciplines have foundations in moral philosophy (e.g., Beauchamp & Bowie, Reference Beauchamp and Bowie1979; Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress1979) but also involve moral psychology in recognition that it is one thing to know what is right and quite another to act upon moral knowledge. In bioethics, the practical tension between moral philosophy and moral psychology can lead to moral distress, or “when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action” (Jameton, Reference Jameton1984: 6). In business ethics, that tension more stereotypically involves moral rationalization, including the experience of being unwilling to do what one ought to know is right (Bazerman & Tenbrunsel, Reference Bazerman and Tenbrunsel2011).

Although bioethics and business ethics are united by the common problem of turning moral knowledge into moral action, they have largely operated as two distinct disciplines with little conversation between them (e.g., Arnold, Reference Arnold2009). Their differences are reinforced by fundamental assumptions about human nature, the respective moral communities in which work is done, and the moral agency of workers within them. Healthcare practitioners, especially nurses, are often stereotyped to be selfless (Tierney, Bivins, & Seers, Reference Tierney, Bivins and Seers2019), whereas business actors, especially owners of capital, are expected to advance their self-interest (Smith, Reference Smith2003). Archetypal bioethics cases about moral distress tend to focus on the experience of front-line providers who are morally distressed when impediments hinder them from acting on their moral convictions (e.g., Jameton, Reference Jameton1993), while business ethics cases more commonly depict managers who may be the source of those very impediments that can interfere with doing the right thing (e.g., Beauchamp, Reference Beauchamp1983). As a result, when the right course of action is not self-evident, moral agents in healthcare may be perceived to be constrained by competing goods, whereas those in business may be seen to be compromised by competing motivations.

The primary purpose of this article is to examine moral distress—a concept with origins in bioethics—as a concept that has value for, yet is curiously missing from, scholarship within business ethics. We will argue that moral distress is useful for understanding important problems of business ethics but also that there are mechanisms for managing business ethics that may also be useful in bioethics contexts. We will go even further to claim that moral distress may well be an existential condition of working in modern business and healthcare organizations, the resolution of which requires us to rethink how we work together to advance a shared moral purpose to cultivate morally supportive communities.

A secondary purpose of this article is to develop a taxonomy of types of moral problems, or what we call “moral conditions” common to bioethics and business ethics, including moral distress. In doing so, we shed new light not only on the relationship between moral knowledge, action, and desire that ethicists have puzzled over since ancient times, but also on the potential for morally supportive communities to cultivate the right desires.

MORAL DISTRESS IN BIOETHICS

The term “moral distress” is widely regarded to have been introduced by Jameton (Reference Jameton1984), in a book about ethical issues in nursing practice. Although the term appears sparingly in the book, it later developed a life and literature of its own. The first time it appears in the book is in a brief aside distinguishing between moral uncertainty, moral dilemmas, and moral distress. Moral uncertainty arises “when one is unsure what moral principles or values apply, or even what the moral problem is”; moral dilemmas are present “when two (or more) clear moral principles apply, but they support mutually inconsistent courses of action”; and moral distress is defined as “when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action” (Reference Jameton1984: 6). In a later article, Jameton (Reference Jameton1993: 542) provides two opening examples of moral distress which manifest that tension between knowledge and action imposed by constraints hindering the decision-maker’s efforts to do what they believe is right. The first involves a nurse’s frustration with a patient’s refusal to comply with postoperative therapies. The second involves a female nurse’s concern that a male physician is not adequately informing a patient about the risks of a cesarean procedure, “but organizational and interprofessional customs make it difficult for the nurse to stop and share” her perspective.

These early accounts demonstrate how moral distress exists at the intersection of philosophy and psychology. Moral reason stereotypically involves the philosophical, deductive application of moral principles to particular questions of action to yield moral knowledge about what to do. Moral distress, by contrast, additionally involves psychological cognition and induction that sometimes interferes with acting on moral knowledge. Based on her first-hand experience as a nurse, Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson1987: 16) characterizes moral distress as involving “psychological disequilibrium … when a person makes a moral decision but does not follow through by performing the moral behavior indicated by that decision.” In later work reflecting on and refining his concept of moral distress, Jameton—a philosopher by training—also increasingly emphasizes the psychological dimension of moral distress. Jameton’s Reference Jameton1993 article collects a series of moral distress narratives from the field in which “different and important values conflict,” entailing the lived experience in which practical reason is incompatible with practical options for action. In 2017, he noted that “standard bioethics texts at the time [when he began studying moral distress] emphasized cognitive moral reasoning and appeals to abstract moral theories,” whereas “nurses’ ethical concerns were heartfelt,” pertaining to “the emotional side of moral problems” (Reference Jameton2017: 618). He also enlarged the application of moral distress well beyond the bedside, to the tension between resource-intensive medical practice and the problem of climate change (Reference Jameton2013, Reference Jameton2017). A 2019 review article concludes that “moral distress” has been interpreted differently over the years but, used correctly, it involves three “necessary and sufficient” conditions: “(1) the experience of a moral event, (2) the experience of ‘psychological distress’ and (3) a direct causal relation between (1) and (2)” (Morley, Ives, Bradbury-Jones, & Irvine, Reference Morley, Ives, Bradbury-Jones and Irvine2019: 646).

By any measure, moral distress has been an impactful concept in bioethics theory and practice. The initial search of the literature for the same 2019 review article yielded over 2,000 items under the terms “moral distress in nursing” and “moral distress in medicine,” and almost 2,000 more under the additional terms “moral distress in social work” and moral distress in education,” before narrowing the review to 152 papers for the study. The book in which “moral distress” first appeared had more than 3,000 scholarly citations as of this writing, while Jameton’s Reference Jameton1993 collection of narratives garnered nearly 1,000 more.

Much of the scholarly study of moral distress has sought greater conceptual clarity, a sign of both its potential value and its potential to be misunderstood. Indeed, as the accounts above assert, it involves a particular kind of distress resulting from tensions between moral knowledge and possibilities for action, not the same psychological distress (e.g., McCarthy & Deady, Reference McCarthy and Deady2008) that may result from being faced with moral uncertainty and dilemmas. Moral distress has been declared to be “the source of endless debate” (Peter, Reference Peter2013: 293), “ambiguous” (Nassehi, Charghi, Hosseini, Pashaeypoor, & Mahmoudi, Reference Nassehi, Cheraghi, Hosseini, Pashaeypoor and Mahmoudi2019: 1048), vulnerable to conceptual “confusion” (Fourie, Reference Fourie2015), and in need of “rethinking” (Tigard, Reference Tigard2018: 479), “expanding” (Crane, Bayl-Smith, & Cartmill, Reference Crane, Bayl-Smith and Cartmill2013: 1) “a broader [feminist] definition” (Morley, Bradbury-Jones, & Ives, Reference Morley, Ives, Bradbury-Jones and Irvine2019: 61), “a broader understanding” (Campbell, Ulrich, & Grady, Reference Campbell, Ulrich and Grady2016: 2), or of “discrete, definable boundaries” (Epstein, Hurst, Mahanes, Marshall, & Hamric, Reference Epstein, Hurst, Mahanes, Marshall and Hamric2016: 17).

Moral distress is usually presented in a negative light, as a problem to be solved. It has even been posited to be an unavoidable “symptom of dirty hands” (Tigard, Reference Tigard2019a: 353), in which no available alternative satisfies the moral claims of everyone involved. However, Jameton originally conceived of it as a problem faced by nurses who had limited power to act on their convictions rather than a problem created by immoral agents in healthcare. Indeed, moral distress may also “reveal and affirm some of our most important concerns as moral agents … [including] honorable character” (Tigard, Reference Tigard2019b: 601).

During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, moral distress was studied as contributing among nurses to feelings of “powerless, worthlessness, anger, sadness, guilt, and helplessness” (Lemmo, Vitale, Girardi, Salsano, & Auriemma, Reference Lemmo, Vitale, Girardi, Salsano and Auriemma2022: 1) as well as a factor associated with physician burnout (Powell & Butler, Reference Powell and Butler2022). Another pandemic-era study of US internists found significant mental health impact among those who experienced high levels of moral distress (Sonis, Pathman, Read, & Gaynes, Reference Sonis, Pathman, Read and Gaynes2022: 2).

In recent years, the related concept of moral injury has been appropriated from military scholarship into healthcare practice. Moral injury in military practice refers to the deleterious psychosocial consequences that may come from being involved in “perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations” (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). It is similar to moral distress in that both posit a tension between a moral agent’s reasonable moral convictions and a psychological response to professional pressures to contravene those convictions. Some claim that moral injury can be used interchangeably with moral distress (e.g., Atuel et al., Reference Atuel, Barr, Jones, Greenberg, Williamson, Schumacher and Castro2021), but others suggest that moral injury can be the consequence of repeated incidences of moral distress (e.g., Reynolds, Owens, & Rubenstein, Reference Reynolds, Owens and Rubenstein2012). During the COVID-19 pandemic, moral injury was increasingly invoked to describe the experience of healthcare professionals who may have been overwhelmed by the scale of the pandemic, their inability to cure every patient, and the enforced isolation of dying patients, among other traumas (e.g., Čartolovni, Stolt, Scott, & Suhonen, Reference Čartolovni, Stolt, Scott and Suhonen2021). Abadal and Potts (Reference Abadal and Potts2022) distinguish between “chronic moral injury” and “acute moral injury” to account for the cumulative effects of injurious experiences experienced by healthcare workers at Theranos, the infamous health technology company that misrepresented the efficacy of its devices.

As with this article’s contention that moral distress is a bioethics term that has value to business ethics, it has been proposed that moral injury has value to business ethics (Nielsen, Agate, Yarker, & Lewis, Reference Nielsen, Agate, Yarker and Lewis2024). We agree that moral injury and moral distress are related; indeed, a recent article by VanderWeele et al. (Reference VanderWeele, Wortham, Carey, Case, Cowden, Duffee, Jackson-Meyer, Lu, Mattson, Padgett, Peteet, Rutledge, Symons and Koenig2025) proposes that they coexist on a “moral trauma” spectrum. However, our focus on moral distress concerns the ongoing experience of tension between moral reason and action rather than the potential consequences of that experience, which may include but are not limited to moral injury. Like most of the other conditions with which we contrast moral distress in this article, moral distress is most often experienced during the process of determining what is right and deciding what action to take. Moral distress has the potential to be mitigated and resolved before it results in wrong action—indeed, we hope this article represents progress toward those outcomes—whereas moral injury typically can only be repaired and compensated after the injury has occurred.

Generally, as might be expected for a relatively new concept, the literature on moral distress tends more often to identify it as a problem than to offer solutions. As the foregoing examples suggest, in healthcare moral distress tends to arise most often in moral communities in which there are institutionalized power imbalances between decision-makers and front-line caregivers who feel constrained from acting on their moral convictions. It has been observed that effective strategies for addressing it should occur across the patient, team, and organization levels and may include the very act of acknowledging it, cultivating conversations about it, and making consultation services available (Hamric, Epstein, & White, Reference Hamric, Epstein, White, Filerman, Mills and Schyve2013). In addition, moral distress-related “burnout can be mitigated by increasing perceived organizational support … [and] deep emotional labor and problem-focused coping” (Powell & Butler, Reference Powell and Butler2022: 6066).

MORAL DISTRESS AS A PROBLEM OF KNOWLEDGE AND ACTION—AND DESIRE

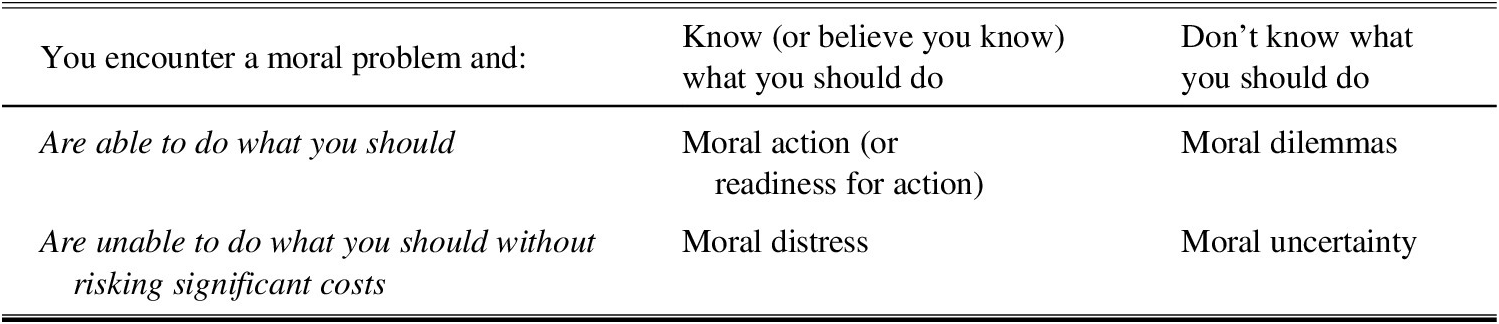

The relationship between moral knowledge and action has long been recognized by philosophers and is fundamental to Jameton’s original distinction between moral uncertainty, moral dilemmas, and moral distress, as shown in Table 1. Although Jameton’s initial accounts of each type of moral problem or condition are brief and incomplete, they capture an essential tension between knowledge and agency to act on one’s knowledge. Moral uncertainty involves not only lack of knowledge but also indecision about how or whether to act—a sort of moral confusion all around. In this case, limitations on agency may come from one’s own internal incapacity to recognize the problem or from external limitations on one’s capacity to solve it. Jameton’s framing of moral dilemmas focuses on the difficulty of knowing how to prioritize among conflicting principles that yield incompatible possible courses of action, resulting either way in a perceived violation of moral duty. Historically, some philosophers (e.g., Ross, Reference Ross1930) have denied the possibility of genuine moral dilemmas, contending that with sufficient information an adequate moral theory can resolve such conflicts—though this position does not preclude the possibility of perceiving there to be moral dilemmas in ordinary experience. Those who acknowledge moral dilemmas in theory and practice suggest more generally that they involve a complex interplay between knowledge and action: we are able to do one action or another, but we are unable to do both, and we are unable to decide whether one option overrides the other (e.g., Sinnott-Armstrong, Reference Sinnott-Amstrong1988).

Table 1: Moral Distress as a Tension Between Knowledge and Agency to Act

In Jameton’s framing, which we follow for the main arguments and examples in this article, moral distress is the exact converse. One knows the solution—or has moral conviction, which is the belief that one knows the solution (about which one may or may not be mistaken). However, one has limited agency because there are constraints that impede acting upon one’s moral knowledge or conviction without incurring negative consequences. As noted previously, Jameton’s account of moral distress, though original, is not conclusive. For example, Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Ulrich and Grady2016) recommend “a broader understanding of moral distress” that considers several nuances that Jameton’s definition does not explicitly contemplate. They include the fact that our moral convictions imply knowledge but we may be wrong or uncertain about those convictions, variation in the degree or intensity of moral distress, the possibility of moral distress by association, and so on. Tigard’s (Reference Tigard2018) call for greater conceptual clarity notes that the constraints on workers’ moral agency may come from extra-institutional sources such as social pressures and expectations. Morley et al.’s (Reference Morley, Bradbury-Jones and Ives2021) “feminist” redefinition of moral distress focuses on the meaning of “constraint,” suggesting that moral distress need not only be institutional imposed from outside but may also arise from internal puzzlement and regret. As these alternative accounts of moral distress suggest, Jameton’s original definition is regarded by some theorists as narrow. The debate, however, is about whether the boundaries of moral distress are more expansive than Jameton’s narrow definition allows—not about whether Jameton’s definition captures genuine instances of moral distress. For the purposes of this article, we use Jameton’s definition because if we successfully establish that Jameton’s account of moral distress has value for business ethics then it stands to reason that other accounts of moral distress that are broader than but inclusive of Jameton’s may also have value for business ethics.

However, the experience of “distress” suggests that moral distress is more than a problem of knowledge and action, that there is a psychological dimension of moral distress arising from limited agency to enact the desire to carry out one’s moral convictions. In this vein, philosophers from Aristotle to Hume have maintained that moral knowledge does not alone motivate moral action but must be accompanied by the right desires (e.g., Hudson, Reference Hudson1981). Research on moral distress has generally presupposed that healthcare workers desire to do what is in the best interest of the patient or other party whose moral welfare is at issue. In most of the research reviewed above, moral distress is a condition experienced by a well-intentioned healthcare worker—usually a nurse—who is constrained by forces beyond her control—more often than not the nurse is a woman—from acting upon her moral convictions. This distress may arise from disagreement about treatment between patient and provider, dissent within the provider team, resource limitations, conflicts between private and public goods, and so on. Moral distress entails feelings of powerlessness, worthlessness, anger, sadness, guilt, and helplessness—to repeat some of the sentiments quoted previously.

In business ethics, advances in social and organizational psychology, especially in the relatively new field of behavioral ethics (e.g., Bazerman & Tenbrunsel, Reference Bazerman and Tenbrunsel2011), have made scholars and practitioners increasingly aware of the relationship between moral desire and action. Social psychologists have challenged the traditional philosophical understanding of moral decision-making as proceeding from general principles to particular cases, arguing instead that moral decision-making begins with moral intuitions that reason serves to rationalize (e.g., Haidt, Reference Haidt2001). Behavioral ethics seeks to explain “why we fail to do what’s right” (Bazerman & Tenbrunsel, Reference Bazerman and Tenbrunsel2011) even when we know it. To explain our failure to act on our moral knowledge and desires, these moral psychologists appeal to classic experiments in social psychology concerning the pressure to conform (Asch, Reference Asch1955) and obey authority (Milgram, Reference Milgram1974) as well as contemporary developments in our understanding of blind spots (Bazerman & Tenbrunsel, Reference Bazerman and Tenbrunsel2011).

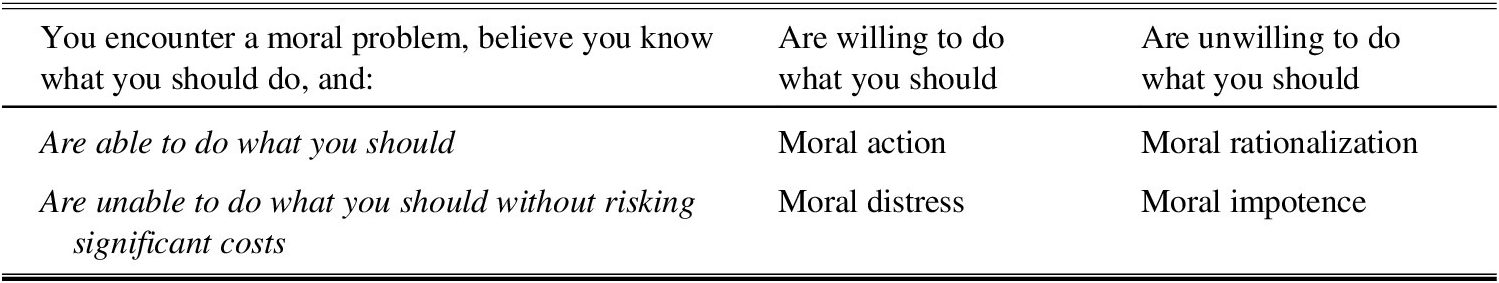

If we take moral knowledge as a given but consider moral distress to be a psychological tension between agency and desire to act, this yields a somewhat different set of outcomes represented in Table 2 than we saw in Table 1. Moral distress is still the consequence of the right knowledge and desires with limited agency to act upon them. But whereas moral action is still the consequence of the right knowledge, agency, and desires, moral rationalization is the radically different consequence of the right knowledge and agency combined with the wrong desires. And, apropos for an article that involves bioethics, we refer to the combination of the right knowledge with lack of agency and desire as moral impotence.

Table 2: Moral Distress as a Tension Between Agency and Desire to Act

Thus, the account of moral distress that we will use to distinguish it from related conditions is that it involves not only a tension between moral knowledge and action but also the psychological experience of distress that comes from the insufficient ability to act in accordance with the right desires.

THE ROOTS OF MORAL DISTRESS IN BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT RESEARCH

Although a robust body of bioethics scholarship has developed around the origins of moral distress in healthcare practice, its roots come perhaps surprisingly from economics. Jameton appropriated the idea of moral distress from Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, political economist A.O. Hirschman’s book (Reference Hirschman1970) that focuses primarily on consumer and employee dissent in business (though it is relevant to other organizations and institutions as well).

The term “moral distress” does not occur anywhere in Hirschman’s treatise. Nor, for that matter, are matters of morality his primary concern. Rather, the book originated in the author’s study of the dynamics of classic economic forces of supply and demand, particularly his curiosity about the niche question of why the Nigerian railway system hauling cargo had not responded more effectively to new competition from trucks. In a perfectly efficient economic system, transportation customers dissatisfied with the railways would either exit—switching suppliers from trains to trucks—or express their voices—seeking improvements or other redress from the railways in order to justify their continuation as customers. Thus would the railways either protect their market share through a combination of better service and perhaps lower prices, or gradually bow out of the market. Loyalty intervenes as a form of nonrational behavior that inhibits perfectly efficient markets, leading customers against their rational economic interest to stick with the status quo despite compelling reasons to switch transportation providers.

Hirschman also observes these dynamics at play in cases in which “members” (as Hirschman refers to employees), not customers, are the primary protagonists, choosing whether to leave, protest, or remain loyal to employers. Labor markets are typically less efficient than consumer markets, rendering switching costs high enough to deter exit or voice. This, of course, is the connection between economics and moral distress. In healthcare organizations, when nurses or other employees confront the psychological anxiety of not being able to uphold their moral convictions in carrying out their work, when exit (quitting one’s job) or voice (objecting to expectations, or escalating concerns about them) are too risky, they are left with the morally distressing experience of remaining loyal to an employer or an authority figure with whose moral judgment they disagree.

Research on moral distress has shown that such experiences are prevalent in healthcare. According to Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Ulrich and Grady2016: 3), “the phrase [moral distress] has had life almost exclusively within the medical and bioethics literature.” It has also held sway in related humanitarian professions, including social work (Morley et al., Reference Morley, Ives, Bradbury-Jones and Irvine2019) and disaster response (Gustavsson, Arnberg, Juth, & von Schreeb (Reference Gustavsson, Arnberg, Juth and von Schreeb2020).

But an examination of the business ethics and business management literatures reveals little uptake. We performed EBSCO keyword and all-text searches for “moral distress” in three top management journals (Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Journal, and Administrative Science Quarterly), two top business ethics journals (Business Ethics Quarterly and the Journal of Business Ethics), and the Journal of Applied Philosophy, and we searched the tables of contents of two leading encyclopedias of business ethics (Wiley Encyclopedia of Management—Business Ethics Volume and Sage Encyclopedia of Business and Society). Among decades of scholarship and, collectively, thousands of papers, the keyword searches yielded one article (Prottas, Reference Prottas2013), the all-text searches yielded sixty-four hits, and the encyclopedia searches yielded two entries, one on “Moral Distress” (Sage) and one on “Organizational Moral Distress” (Wiley). Among those results, most were false positives, containing both words but not the term itself; others mentioned “moral distress” incidentally in relation to other concepts, such as “moral stress” (e.g., Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Owens and Rubenstein2012) and “moral injury” (noted above); a few involved incomplete accounts of moral distress, characterizing it as “values misalignment” (Mills & Werhane, Reference Mills, Werhane and Cooper2014) or “against my conscience” (Prottas, Reference Prottas2013: 54); one characterized it accurately but treated it in a cursory manner as part of a literature review (Cullen, Reference Cullen2022); and another considered the possibility that a market for organ donation should entail moral distress at a societal level (Rivera-López, Reference Rivera-López2006). One encyclopedia entry also characterized moral distress accurately and even suggested it might be experienced in professions outside of healthcare, but it was regrettably brief and lacking specifics on how it applied to business (Piazza, Reference Piazza and Kolb2018). Perhaps promisingly, an additional search also uncovered a paper in an obscure, regional management journal that focuses on expanding the definition of “moral distress” in ways that would increase the applicability of the term to occupational settings beyond nursing (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Bayl-Smith and Cartmill2013).

Although specific occurrences of moral distress are scarce in business ethics and management scholarship, searching those same journals for studies of nursing yields insight on phenomena that may be contributors to, consequences of, or otherwise associated with moral distress. Potential contributors include, for example, work-related distress (e.g., George, Reed, Ballard, Colin, & Fielding, Reference George, Reed, Ballard, Colin and Fielding1993), lack of decision-making participation (e.g., Connor, Reference Connor1992), social isolation (e.g., Fairhurst & Snavely, Reference Fairhurst and Snavely1983), and emotional influence (e.g., Fulmer & Barry, Reference Fulmer and Barry2009). Consequences include, for example, job dissatisfaction (e.g., Lyon & Ivancevich, Reference Lyon and Ivancevich1974), burnout (e.g., Cordes & Dougherty, Reference Cordes and Dougherty1993), and emotional response (e.g., Gaudine & Thorne, Reference Gaudine and Thorne2001). Other associated phenomena include, for example, social identity (e.g., Pratt & Rafaeli, Reference Pratt and Rafaeli1997), professional identity (e.g., DiBenigno, Reference DiBenigno2022), care ethics (e.g., Au & Stephens, Reference Au and Stephens2023), and, apropos to Jameton’s understanding of Hirschman, voice and exit (e.g., Lam, Loi, Chan, and Liu, Reference Lam, Loi, Chan and Liu2016).

MORAL DISTRESS IN BUSINESS ETHICS

In 1978, Dr. William Campbell, a scientist for the pharmaceutical company Merck, approached the head of Merck research labs, Dr. Roy Vagelos, with a proposal to fund research and development on a cure for an ailment whose patients would be unable to pay for it (Hanson & Weiss, Reference Hanson and Weiss1991). Campbell had read about onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, caused by a parasitic worm that produced infection, intolerable itching, and sometimes blindness. The description of how the disease manifested in human beings reminded him of a similar condition afflicting cattle for which Merck had developed a remedy. Although the story of the Mectizan Donation Program—as it came to be known—has a happy ending, enabled by Vagelos’s decision to fund research and development and the subsequent successful production and distribution of the drug, the seeds of moral distress—the potential for misalignment among knowledge, desire, and action—were present. First, Campbell was aware that his organization was uniquely positioned to alleviate this particular form of human suffering (knowledge). Second, Campbell wanted Merck to invest in researching a cure even though the patients who needed help would not be able to pay for a cure (desire). Third, it was not fully within his power to decide whether to do so (action). Had Campbell been unable to persuade his boss, he might have experienced moral distress. Fortunately, instead, he was supported, patients were served, and Merck secured the loyalty of and even became an employer of choice for many research scientists.

The story is well known among bioethicists and business ethicists because it is remarkable. Barely a decade removed from the publication of Milton Friedman’s famous essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” (Reference Friedman1970), it was exceptional to prioritize the welfare of non-paying patients ahead of shareholder value maximization. In the years since, corporate social responsibility initiatives have become more commonplace and even attached to reputation enhancement strategies (e.g., Malik, Reference Malik2014), but Merck did not and has not heavily marketed the program in search of reputation benefits. Frankly, it is easier to imagine Campbell’s proposal being denied than to contemplate the success that actually ensued. Had this hypothetical alternative to the real story played out, Campbell’s scientific hunch, combined with his humanitarian inclination, would have been thwarted by the institutional pursuit of profit. Even though they were both healthcare professionals working for a business, in such circumstances, Campbell’s disappointment might have been described by bioethicists as moral distress. Vagelos’s decision might have been rationalized by business ethicists appealing to economic constraints. And the outcome would have been unremarkable for the profit-maximizing morality of business communities of that era.

These different takes on the same hypothetical ending suggest at least one possible explanation for why moral distress is a familiar term in bioethics and not in business ethics. Our interpretations of healthcare behavior may be informed by different assumptions about human nature than our interpretations of business behavior. Whereas healthcare providers are stereotypically presumed to have moral desires, business professionals are stereotypically presumed to be motivated by material desires. Had Merck not gone forward with seeking a cure to river blindness, the bioethical culprit for Campbell’s moral distress—caused by the inaction on his knowledge of a possible cure coupled with his desire to cure it—would have been the institutional constraint of profit. As in Table 2, the combination of moral knowledge, moral desire, and limited agency to bring about moral action yields moral distress.

By contrast, the business ethics account of inaction in this hypothetical alternative would have been less likely to point to Campbell’s limited ability to bring about his desired outcome and more likely to point to Vagelos’s unwillingness to do so brought on by the wrong desires. That is, the material desires attributed to business professionals are taken as moral rationalization to justify why business actors sometimes fail to act on moral knowledge even when they are able to do so. The combination of moral knowledge, immoral desire, and agency to bring about moral action yields moral rationalization rather than moral distress.

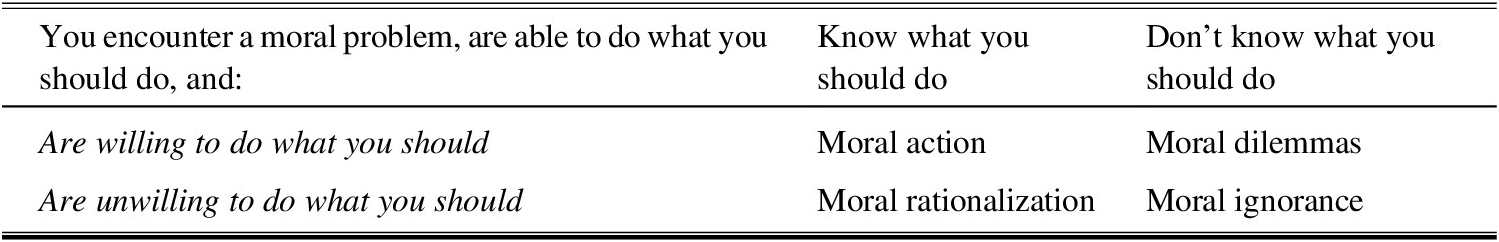

In summary, one narrative that may explain why moral distress is a bioethics phenomenon and not a business ethics phenomenon comes down to diverging accounts of human nature attributed to healthcare providers and business actors. According to this narrative, the former experience moral distress when they are unable to act upon the right desires without risking negative repercussions. Meanwhile, the latter engage in moral rationalization when they are unwilling to act upon the right knowledge, as shown in Table 3. Meanwhile, this combination of possibilities also yields a novel combination of neither knowing nor desiring to do what is right despite being able to do it, which we refer to as moral ignorance.

Table 3: Moral Rationalization as a Tension Between Knowledge and Desire to Act

MORAL RATIONALIZATION AND MORAL DISTRESS IN BUSINESS

Hypotheticals aside, a more recent and also iconic business ethics case not only brings these assumptions about business actors into sharper relief but also highlights the influence of institutional constraints on individual behavior. In 2016, Wells Fargo admitted that thousands of its employees had for years been opening accounts for customers that the customers did not request, yet for which they sometimes paid and/or incurred risk (Premachandra & Filabi, Reference Premachandra and Filabi2018). Internal and external investigations into the matter suggested when senior management sought to deepen customer relationships by setting goals to increase the number of accounts each Wells Fargo customer had with the bank, those goals were translated into performance expectations that employees perceived as impossible to meet without cheating. Seeing that their peers who challenged these metrics or who did not meet their numbers sometimes lost their jobs, sales agents knowingly forged account registration documents, opening unauthorized customer accounts and perpetuating the fraud. The profitability goals that unleashed the growth strategy were passed down the institutional hierarchy, from senior managers who set the strategy, to middle managers who translated it into performance targets, to branch managers who pressured their employees to meet those targets, to rank-and-file employees who opened the accounts.

This case too shows the familiar tension in business ethics between moral knowledge (the duty to serve customers) and immoral action (opening unauthorized accounts). Soon after the scale and systemic nature of the fraud was discovered, many employees were fired for participating in the scheme. This outcome seems to reinforce familiar assumptions about those business actors’ desires: they rationalized knowing violations of the code of conduct in order to serve their own material interests of performance bonuses or job security.

Later, however, the bank reversed course. The company quietly hired back many of the lower-level employees who had been thwarted when they tried to voice their concerns to their superiors (Rucker, Reference Rucker2017). Meanwhile, the CEO stepped down (Glazer, Reference Glazer2016) and other executives who imposed the pressures that led to it were let go (Merle, Reference Merle2017). These decisions may be taken to imply that at least some business actors in this case were not motivated by the wrong desires but rather—like some healthcare actors—they may have been vulnerable to moral distress: knowing what is right and desiring but unable to enact it without risking negative repercussions because of institutional constraints.

Two more well-known cases reinforce that moral distress is not only present in business but go further to suggest that it may be ever-present. The infamous Enron failure (McLean & Elkind Reference McLean and Elkind2003) was the first of a wave of major financial accounting scandals to occur after the US economy had already been challenged by the bursting of the Internet bubble and 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001. In October of that year, headlines announced that Enron was taking a massive charge against earnings to account for debt that had been hidden off of its balance sheet, and by December, Enron had become the biggest bankruptcy in American history. The Enron “whistleblower,” Sherron Watkins, had sent an anonymous letter (2001) expressing concerns about Enron’s accounting methods to the company’s CEO, Ken Lay, in August, and when the letter went unaddressed, Watkins resent it with her name. The letter—along with testimonials by Watkins and some of her colleagues in the aftermath of Enron’s bankruptcy—contain the characteristic tension between knowledge and action. First, Watkins’s memo shows her awareness of hidden debt which inflated Enron’s value on paper but that, because of a perfect storm of economic circumstances, was coming due and would destroy shareholders’ equity while costing employees their jobs and retirement accounts. Second, Watkins and others worried that they would be punished or fired for challenging management, hence her original anonymous memo.

A moral rationalization take on the Enron story would emphasize that Watkins herself was arguably not selfless in her desires. In her memo, she presented a “best case” option to “clean up [the accounting misdeeds] quietly” if “the probability of discovery is low enough,” even though generally accepted accounting principles would have demanded that a fraud this large be disclosed publicly. In her “worst case,” she recommended that the company “quantify [and] develop P.R. [public relations] and I.R. [investor relations] campaigns.” By the time Watkins (Reference Watkins2002) testified before Congress, nearly six months after her internal memorandum, Enron was already bankrupt (Watkins, Reference Watkins2001). Many of Watkins’s superiors were indicted and sentenced to prison terms for rationalizing the accounting fraud as a means to the end of temporarily increasing shareholder value to the tune of building the world’s fifth largest company on paper. By contrast, Watkins has been mostly hailed as a heroic if ineffectual whistleblower. In this morally distressing version of the story, Watkins may have desired to come clean but was constrained by institutional pressures from doing so, hence her proposal to compromise.

In one more iconic and particularly tragic case in contemporary business ethics, more than 1,000 laborers at the Rana Plaza textile factory in Bangladesh were killed when the building collapsed (Centre for Policy Dialogue, 2013). The day before the incident, some workers had been informed of cracks in the facade of the building. Ordered to return to work or lose their jobs, they were faced with a choice between voicing their concerns that could lead to unemployment and silencing their concerns about their safety. The apparel supply chain had a history of human rights abuses, imposing long hours and poor working conditions on mostly women workers—and sometimes children—for meager wages, leading to factory audits to detect and remediate abuses. However, after the collapse, several well-known Western brands discovered that, previously unbeknownst to them, some of their orders had been subcontracted to Rana Plaza by their contractors of record. In the world of fast fashion, contractors routinely accepted orders from their customers knowing that they could not possibly fulfill them. One explanation for this practice involved the moral rationalization that they would lose the business altogether if they refused the orders, relying for extra production capacity on a hidden network of subcontractors whose employees were not granted the same protections as those of the contractors of record that were subjected to auditing standards. This version of the story paints factory owners as greedy profit maximizers willing to sacrifice employee safety for money. A morally distressing version of the story, however, suggests that those factory owners were faced with the vexing choice of forgoing the business—which would impose economic harm not only upon them but especially the lowest-paid laborers—or fudging their capacity along with safety standards in order to retain the business.

Which telling of these tales is more plausible: the ones that attribute moral rationalization to bad actors motivated by the wrong desires, or the ones that attribute moral distress to business actors with good intentions who feel powerless to resist institutional pressures for profitability? We are not naively ignorant of the possibility that there are bad actors in business, nor of the possibility that these stories could involve some of each. However, we think it may also be naïve to discount the possible presence of moral distress in business. Since our main purpose in this article is to examine the potential value of moral distress to explain and address business ethics problems, our present aim is to posit the plausibility of these morally distressing versions of each story: that the protagonists of the Wells Fargo, Enron, and Rana Plaza stories may have had the right desires thwarted by institutional constraints rather than the wrong desires of stereotypical business bad actors. That is to suggest the possibility that Wells Fargo customer service staff may have been trying to alleviate their moral distress when they opened unwanted accounts, perhaps at the same time morally rationalizing that what the customers did not know would not hurt them. And that Sherron Watkins did not speak up sooner or send her memorandum to external regulators because she was—like a morally distressed nurse caught between the patient’s well-being and putting her own job at stake—morally distressed by her powerlessness to support shareholders’ rights and preserve the security of her position—both of which, not incidentally, lost out. That factory owners who outsourced work to unaudited subcontractors may have hoped against hope that they would not come to regret their failure to act upon the moral distress they experienced at the possibility that those subcontractors did not look out for the safety and well-being of their employees.

To be clear, we cannot test which account of each case tells a truer story—the morally rationalizing or the morally distressing one. Moreover, whether in fact workers in healthcare and business have diverging desires—moral and material, respectively—is an empirical question that is not within the scope of this article to study. However, it is within our scope to question stereotypical assumptions about human nature that seem to imply that behavior that contravenes moral knowledge is brought on by moral distress in healthcare but not in business. Our point is that business actors may sometimes be caught between knowledge, action, and desire not for stereotypically self-interested, material motivations but rather for moral ones. And that, conversely, healthcare providers may not always be as selfless as we might idealize and might sometimes suppress their voices in service to institutional goals and personal job security. That is to suggest that neither the stereotypical attributions of benevolent human nature that we may wish to attribute to healthcare providers nor the self-interested if not malevolent stereotypes we hold about business persons are fully or even fairly representative.

MORAL DISTRESS AS AN EXISTENTIAL CONDITION OF MORALLY DISTRESSING COMMUNITIES

The conventional telling of these business tales, from which the language and logic of moral distress is absent, holds that business persons have the wrong desires that render them sometimes unwilling to act in accordance with what they know to be right, using the profit motive and other institutional pressures to rationalize immoral behavior. Our alternative telling of these tales contends that business persons are not born with the wrong desires but rather sometimes work in morally distressing communities that impose the wrong desires upon them. After all, we do not know, desire, and act as disembodied individuals but rather as members of moral communities. We contend that this alternative telling warrants greater consideration, challenging preconceptions about both the human nature of business actors and the nature of business communities. It suggests businesses have the potential to be morally distressing communities that impose institutional constraints that render business actors not unwilling but rather unable to enact their moral knowledge without risking negative consequences.

According to Liaschenko and Peter (Reference Liaschenko, Peter, Deem and Lingler2024), the concept of moral communities has appeared with more frequency in the nursing ethics literature in recent years. Informed by Margaret Urban Walker’s conception of morality as grounded in our “personal relationships … institutional roles … and interactions between them” (Reference Walker1997: 38), a moral community—or what we will call a morally supportive community—is “a group of people working toward a common moral end” or purpose. Such communities exemplify three practices: (1) “supporting relationships,” (2) managing conflict, and (3) moral communicative work” (Traudt, Liaschenko, & Peden-McAlpine, Reference Traudt, Liaschenko and Peden-McAlpine2016: 207) that plausibly map to Hirschman’s three options of exit, voice, and loyalty, respectively. We could say that a morally supportive community ought to enable conflict management as an alternative to exit, provide communication channels to voice and discuss concerns, and cultivate loyalty through supporting relationships and shared purpose. We will refer to a morally distressing community as one in which the absence of effective conflict management entails no options to alleviate conflict except for exit, the use of voice poses a risk to job status and security, and there is tension between the moral ends of the community and the individual’s moral convictions. In other words, a moral distressing community contributes to the potential for moral distress.

This claim helps to explain why moral distress has not historically been recognized in business when business itself is the constraint. Moral distress is endemic to business as an institution that has historically been economically conceived as the pursuit of profit maximization (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970) between competitors amid scarce resources (Porter & Kramer, Reference Porter and Kramer2011). To be clear, this is not to assert that profit-making is inherently immoral. Rather, it is to suggest that one way in which a business community can impose a constraint is when the pursuit of profit is an impediment to higher moral purposes. For example, if business professionals are moral agents who are pressured by the institution in which they work to prioritize becoming agents of profit, it should not be surprising that they would experience moral distress when profit-making is at cross purposes with such alternative moral ends as curing disease, serving customers, following generally accepted accounting principles, and providing healthy and safe working conditions for employees. Even when the pursuit of profit and associated goals of innovation and economic growth are seen as morally worthy ends, business communities can introduce moral distress when competitive dynamics and regulatory loopholes render success more challenging without moral compromise. It is not that moral distress is not anywhere in business; to the contrary, it is potentially everywhere. That is to say that, paradoxically, we tend not to recognize the presence of moral distress in business because of its very pervasiveness, because to be morally distressed is an existential condition of business.

Though the business examples we have provided are famous for reasons including the scale of success (Merck) and failure (the others), we do not believe that the pattern of the morally distressing stories they tell is exceptional. Rather, they illustrate routine tensions that are well-recognized in business as something other than moral distress: between meaning and money (Michaelson, Pratt, Grant, & Dunn, Reference Michaelson, Pratt, Grant and Dunn2014), personal and professional expectations (Gentile, Reference Gentile2010), professional and public responsibilities (Davis & Stark, Reference Davis and Stark2001), ethics and economics (Anderson, Reference Anderson1995; Sen, Reference Sen1988), and stakeholders and stockholders (Freeman, Martin, & Parmar, Reference Freeman, Martin and Parmar2020). Indeed, that pattern of these stories is remarkably similar to that in the nurses’ stories to which Jameton’s original formulation of moral distress attempted to give voice. They pose a tension between knowledge—“when one knows the right thing to do,” as Jameton put it—and action—when “institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action,” and the desire to do the right thing. In other words, they give us reason to believe that some of the most iconic business ethics cases in recent memory bear the classic markers of moral distress.

However, we do not contend that every business is a morally distressing community, only that the dominant conception of business in recent history as a profit-maximizing machine is likelier to impose moral distress. Moreover, we do not claim that business is the only kind of morally distressing community. Rather, we recognize the research that shows that healthcare organizations also have the potential to be moral distressing communities. Moreover, healthcare workers today are arguably more constrained by stereotypical business pressures than they were when Jameton introduced moral distress and managed care was quite new. Some of the time, moral distress is imposed by the profitability pressures within healthcare businesses that experience the stereotypical tensions between margin and mission. As we have seen in the bioethics examples involving moral distress, however, other institutional pressures—including but not limited to providers’ lack of agency to follow through on patient care, and power and often gender dynamics between physicians and nurses—can cultivate moral distressing communities within healthcare organizations. Indeed, just as our thesis about moral distress in business challenges assumptions about the moral nature of business actors and business communities, these institutional pressures in healthcare organizations challenge assumptions about the moral nature of healthcare actors and healthcare communities. That is to say that healthcare workers may be often, though not always, steered by the right desires toward healthcare work where they sometimes, though not always, experience morally distressing tensions between the right desires and pressures that constrain them from acting upon them.

MORALLY SUPPORTIVE COMMUNITIES AND OTHER RESEARCH DIRECTIONS IN BIOETHICS AND BUSINESS ETHICS

Business apologists might be inclined to accuse us of replacing one set of stereotypes—that business actors are self-interested and healthcare providers are selfless—with another—that business is an immoral pursuit and that healthcare is a moral one. Either set of stereotypes might reinforce the real divide between the scholarship and practice of business ethics and bioethics. However, one purpose of this article has been to use those stereotypes to disabuse us of them, in part by showing how the bioethics phenomenon of moral distress has value also in the context of business and management ethics. While research on moral distress in healthcare suggests that it may be even more pervasive than it is recognized to be, part of the reason that it is noteworthy is that it ought to be exceptional. In other words, we recognize that there is something wrong when healthcare professionals are constrained from doing what is right. By contrast, part of the reason that moral distress is not noteworthy in business is that we expect business sometimes to put its professionals in morally compromising positions that they have limited agency to adjudicate without risking adverse consequences. However, the lines between medicine and business are increasingly blurry. Methods of business management are exercising greater influence over medical institutions (e.g. Barrett, Reference Barrett2019). Meanwhile, more business organizations are trying to claim, akin to the medical professions, a social purpose beyond profit-making (e.g., Michaelson, Lepisto, Pratt, Hedden, & Brown, Reference Michaelson, Lepisto, Pratt, Hedden and Brown2020). As in the Merck example, business and healthcare often coexist within the same enterprise, and profits and purpose have the potential to be mutually distressing or mutually supportive. Recognizing the presence of business motivations in medicine and the possibility of moral distress in business is one essential step toward addressing the sources of moral distress and preventing the most dramatic of the outcomes of moral distress that Jameton appropriated from Hirschman: exit. Thus, we hope one research direction of this article is to use bioethics scholarship on moral distress to better understand and address moral distress in business. This may include, but is not limited to, empirical research on moral distress in business. We recognize that our article has established the possibility that moral distress exists, perhaps everywhere, in business, but this opens the potential for more work to be done to prove and better understand its causes and consequences in business.

While moral distress is the primary focus of our article, we hope that this article stimulates further inquiry into the potential for the study of bioethics research to inform the study of business ethics. This includes, for example, comparative studies of how moral distress operates in bioethics and business ethics. Furthermore, although we have primarily focused on Jameton’s original account of moral distress in this article, we believe it is worth considering how broader accounts of moral distress may also be of value not just to bioethics research on moral distress but to business ethics research. For example, Campbell et al.’s (Reference Campbell, Ulrich and Grady2016) “broader understanding” of moral distress opens up new possibilities to understand how different degrees of moral distress intensity and how direct and indirect association with moral distress may influence the experience of moral distress in business organizations. Tigard’s (Reference Tigard2018) claim that some constraints that contribute to moral distress come from extra-institutional sources implies that the social expectations and pressures on business may be felt by business managers and workers. Corley, Elswick, Gorman, and Clor’s (Reference Corley, Elswick, Gorman and Clor2001) moral distress scale measure provides further insight into the broad context in which moral distress can arise, composed of thirty items that may contribute to conditions of moral distress, some of which may be present in business and other nonhealthcare organizations—such as insufficient staffing, safety concerns, pointless procedures, and circumstances beyond the worker’s control, among others. In general, these nuances in bioethics research on moral distress are also worth considering for business ethics research on moral distress.

Continuing with Hirschman’s framework, a second research direction we hope this article stimulates involves using business scholarship on voice to better address moral distress in bioethics settings. After all, business organizations are arguably more advanced than healthcare organizations in the management of organizational ethics, including providing communication mechanisms to voice ethical questions and concerns. Organizational ethics consists of the systems and processes that support ethical behavior and compliance with established standards (e.g., Fiorelli, Reference Fiorelli2004), as distinguished from clinical ethics, which more typically involves analyzing and resolving matters of patient care regarding which established standards may be ambiguous (e.g., Foglia & Pearlman, Reference Foglia and Pearlman2006). In the parlance of this article, organizational ethics more often pertains to matters of action whereas clinical ethics more often pertains to questions of knowledge. The first so-called ethics officers originated in business organizations (Josephson, Reference Josephson2014), and in the ensuing decades, organizational ethics and compliance has grown into a veritable profession, supported by dedicated educational programs and professional networks (Ethics and Compliance Initiative, 2024; Society for Corporate Compliance and Ethics, 2024). The conventional elements of an effective organizational ethics and compliance program include procedures for escalating concerns without fear of retaliation when violations are observed (United States Sentencing Commission, 2018). The profession routinely surveys workers on questions of concern to anyone interested in studying moral distress, from observed misconduct to reporting observations to experiencing retaliation (Ethics and Compliance Initiative, 2023). Organizational ethics offers communication paths for escalating and addressing moral distress that may be absent or obfuscated in healthcare contexts.

Of course, studying the efficacy of escalation and whistleblowing mechanisms in healthcare contexts is just one way in which the study of business ethics has the potential to benefit the study of bioethics. Another particularly relevant area of business ethics and organization studies that has grown in recent years is the study of meaningful work. Meaningfulness is a source of attraction to the healthcare professions but has less well-understood perils for workers’ well-being and job security (e.g., Lysova, Tosti-Kharas, Michaelson, Fletcher, Bailey, & McGhee, Reference Lysova, Tosti-Kharas, Michaelson, Fletcher, Bailey and McGhee2023). A more general way in which understanding business ethics may be of value to those who study bioethics has to do with the tension between market and moral values—expressed in long-standing concerns about how the business of healthcare introduces financial risk to providers and patients (e.g., Mariner, Reference Mariner1995) and professional tensions between market imperatives and professional moral obligations of healthcare providers (e.g., Relman, Reference Relman1992). Since the turn of the century, business ethics has arguably made progress toward balancing these tensions by exploring the prospect of business as a profession like medicine (e.g., Khurana, Reference Khurana2010) and considering how to reconcile the interests of stockholders and stakeholders rather than seeing them as fundamentally at odds to each other (e.g., Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Martin and Parmar2020)—developments that may be instructive to bioethicists who may have limited exposure to business and markets. Broadly, as the lines between healthcare and business organizations blur, there are opportunities to apply business ethics thinking in key domains of moral agency, stakeholder relationships, and social responsibility (e.g., Moriarty, Reference Moriarty2021) to thinking in bioethics about how individuals and healthcare organizations interact to serve societal well-being. Furthermore, Fisher (Reference Fisher2001) observes that the dominant ethical theories in bioethics and business ethics overlap but with different points of emphasis, raising further potential to consider how such theories apply to the different types of relationships that exist in healthcare and business between, for example, patients and customers, employees and managers, providers and payers, and so on.

The third piece of Hirschman’s framework is loyalty, and it is notable that the nurses in the Traudt et al. (Reference Traudt, Liaschenko and Peden-McAlpine2016) study of moral communities had worked in the same critical care unit for an average of seventeen years. This is not to say that longevity is a necessary feature of moral communities but it is to suggest that moral communities cultivate loyalty to the community and their members. The distinctively feminist origins of the concept of moral communities is telling because moral distress has historically been studied in bioethics as a predominantly female experience in which caring motives are impeded by institutional hierarchies, and also because the profit motive in business has often been associated with “macho myths and metaphors” depicting masculine strength (Solomon, Reference Solomon1993: 22). We hope an associated effect of our research is to promote morally supportive communities in healthcare, business, and other organizations that articulate a common moral end beyond profit. One way in which to promote those morally supportive communities is to remove those constraints that impede workers’ duty to act on their moral convictions, consistent with Young’s (Reference Young2011) claim that we have socially connected responsibilities to address structural injustices for which we may not be personally to blame.

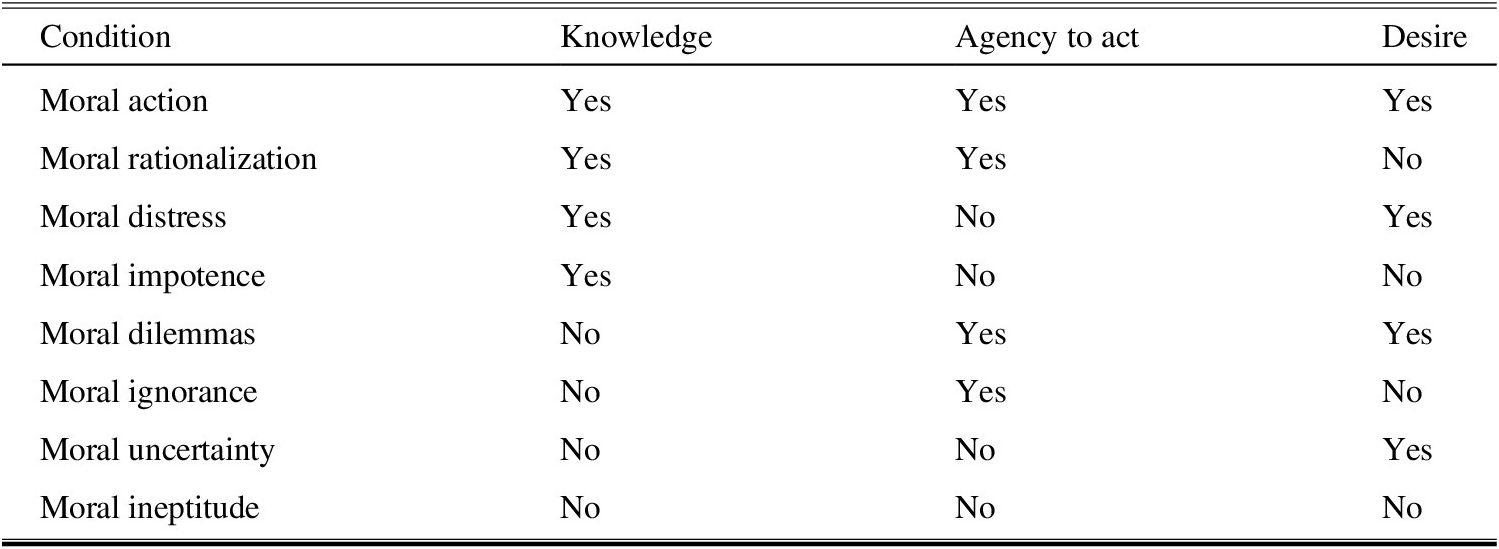

One ancillary contribution of this study is that its analysis of the relationship between moral knowledge, desire, and action might contribute to a better understanding of morality itself. The three foregoing tables in this study have yielded a taxonomy of conditions (summarized in Table 4) resulting from the eight possible relationships between them—including an eighth combination not represented in the previous tables: moral ineptitude, the absence of moral knowledge, agency, and desire. This taxonomy suggests the potential for morally supportive communities to cultivate the right desires and to align them with moral knowledge and action in bioethics, business ethics, and other domains of moral practice.

Table 4: Moral Conditions Resulting from the Relationship Between Moral Knowledge, Agency, and Desire

Acknowledgements

Christopher Wong Michaelson and Joan Liaschenko dedicate this article to our colleague, mentor, and friend, Andy Jameton, who passed away while we were working together on this article. Andy was integral to the formation and foundations of this article, contributing ideas, examples, review, and commentary, and we thank his widow, Marsha Sullivan-Jameton, for permission to include him posthumously as a coauthor. We are also grateful to Deb DeBruin, Joel Wu, and other colleagues at the University of Minnesota Center for Bioethics for providing insights and commentary on the ideas in the article and to the organizers and attendees of a seminar at Fordham University. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers and handling editor at Business Ethics Quarterly who challenged and encouraged us and the journal’s managerial and production staff who helped bring the article to publication.

Christopher Wong Michaelson (cmmichaelson@stthomas.edu, corresponding author) PhD, is the Barbara and David A. Koch (“coach”) Endowed Chair of Business Ethics, University of St. Thomas, and Affiliate Faculty, Center for Bioethics, University of Minnesota.

Andrew Jameton, PhD, was professor emeritus, Department of Health Promotion, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Affiliate Faculty, Center for Bioethics, University of Minnesota.

Joan Liaschenko, PhD, RN, HEC-C, FAAN, is professor emeritus, Center for Bioethics, University of Minnesota, where she was professor in the School of Nursing, and professor and director of the Ethics Consult Service for the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Fairview.