1 Introduction

Fossils are a rich source of information about the history of the Earth and can be used to test hypotheses about mass extinctions, biogeography, the diversification of clades and communities, the effects of climate change on evolution and extinction, and the effects of evolution and extinction on climate. Fossils are also a finite natural resource, an important aspect of a nation’s natural heritage, and a didactic medium that engages public audiences in discourse about the history of life on Earth. The fossil record of the National Park System (NPS) exists precisely at the intersection between fossils as a body of scientific information and fossils as public natural heritage, and the National Park Service balances the multidimensional significance of federal fossil resources through its four core management activities: inventory, monitoring, research, and curation.

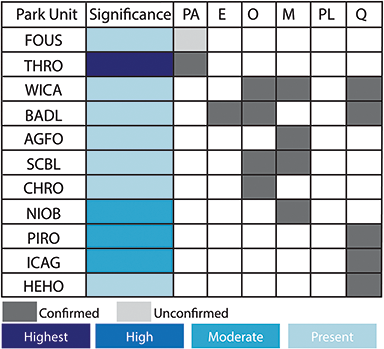

Here, we present a comprehensive inventory of Cenozoic paleobotanical resources that details the spatial, stratigraphic, taxonomic, and temporal scope and significance of fossil plants preserved in 74 of the 288 National Park Service areas with paleontological resources. This inventory is the first installment of a complete inventory of Cenozoic, Mesozoic, and Paleozoic paleobotany of the NPS, and the product of a collaborative effort among four student–mentor pairs and NPS scientists sponsored by the Paleontology in the Parks Fellowship Program of the National Park Service and Paleontology Society.

1.1 Cenozoic Paleobotany in North America

The Cenozoic paleobotanical record of North America preserves evidence of the modernization of plant families and terrestrial ecosystems, extinct plant lineages and plant communities without modern ecological analogs, and the response of plants to global events such as the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) mass extinction, Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), and climatic optima. This history has been written in part based on fossil plants now under the stewardship of the NPS, and provides a rich context for interpreting the significance of new or understudied NPS fossil plant resources. In this section, we summarize key patterns present in the Cenozoic paleobotanical record of the USA in relation to four themes with particular relevance for interpreting NPS resources: recovery from mass extinction, angiosperm diversification, climate change, and intercontinental dispersal. In doing so, we highlight the paleobotanical resources of NPS units that have contributed or have the potential to contribute to a greater understanding of the evolutionary, climatic, and physiographic history of North America.

1.1.1 Extinction Recovery

The collision of a bolide asteroid with the Yucatan Peninsula about 66 Ma prompted a restructuring of terrestrial ecosystems through instantaneous and widespread extinction of species followed by heterogeneous pathways of recovery (Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Alvarez, Asaro and Michel1980; McElwain and Punyasena, Reference McElwain and Punyasena2007; Nichols and Johnson, Reference Nichols and Johnson2008; Wilf et al., Reference Wilf, Carvalho and Stiles2023). Mass extinction among plants at the K–Pg boundary has been documented from latest Cretaceous and earliest Paleocene outcrops in the Williston Basin in North Dakota (Wilf and Johnson, Reference Wilf and Johnson2004), the Denver Basin in Colorado (Barclay et al., Reference Barclay, Johnson, Betterton and Dilcher2003; Lyson et al., Reference Lyson, Miller and Bercovici2019), and the Raton and San Juan basins in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico (Tschudy et al., Reference Tschudy, Pillmore, Orth, Gilmore and Knight1984; Wolfe and Upchurch, Reference Wolfe and Upchurch1986, Reference Wolfe and Upchurch1987; Flynn and Peppe, Reference Flynn and Peppe2019). Palynological sequences across the K–Pg boundary indicate a spike in fern spore abundance and paucity of angiosperm pollen immediately above the iridium anomaly that marks the boundary and extinction of 20–30% of pollen taxa (Tschudy et al., Reference Tschudy, Pillmore, Orth, Gilmore and Knight1984; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Nichols, Attrep and Orth1989; Barclay et al., Reference Barclay, Johnson, Betterton and Dilcher2003). Macrofloral assemblages offer greater taxonomic resolution than palynofloras, and comparison of latest Cretaceous and earliest Paleocene leaf assemblages indicates even higher plant extinction rates, around 50% (Wolfe and Upchurch, Reference Wolfe and Upchurch1986; Wilf and Johnson, Reference Wilf and Johnson2004; Lyson et al., Reference Lyson, Miller and Bercovici2019).

The North American forests that emerged in the first ca. 5 Ma ensuing the K–Pg mass extinction differed markedly in physiognomic and floristic attributes from the latest Cretaceous forests that they replaced, and showed geographic heterogeneity among themselves. Macrofossil evidence from the Raton and Williston basins suggests an increased importance of deciduous trees in Early Paleocene mid-latitude floras based on community-level shifts in leaf functional traits (Wolfe and Upchurch, Reference Wolfe and Upchurch1987; Blonder et al., Reference Blonder, Royer, Johnson, Miller and Enquist2014), and this inference meshes well with the prominence of families such as Betulaceae, Cornaceae, Juglandaceae, and Platanaceae, which are common in the temperate deciduous forests of the Northern Hemisphere today (Manchester, Reference Manchester2014). These lineages, alongside taxodiaceous conifers, Cercidiphyllaceae, and Hammamelidaceae, were the dominant components of backswamp and alluvial ridge habitats during the first several million years following the bolide impact (Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998), and have been interpreted to comprise a low-diversity and spatially homogenous flora spanning from southern Alberta to central Colorado (Johnson and Hickey, Reference Johnson and Hickey1990; McIver and Basinger, Reference McIver and Basinger1993; Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998; Barclay et al., Reference Barclay, Johnson, Betterton and Dilcher2003; Wilf and Johnson, Reference Wilf and Johnson2004; Manchester, Reference Manchester2014). However, recent reports from earliest Paleocene strata in the San Juan Basin and the Corral Bluffs site in the Denver Basin have documented higher diversity floras within the first million years of the Paleocene (Flynn and Peppe, Reference Flynn and Peppe2019; Lyson et al., Reference Lyson, Miller and Bercovici2019). These floras comprise a distinct set of taxa, including the earliest legume fossil, and have physiognomic attributes comparable to modern seasonal tropical forests.

Yukon–Charley Rivers National Preserve and Denali National Park and Preserve in central Alaska, and Big Bend National Park in southern Texas each include fossiliferous sequences of Upper Cretaceous and Lower Paleocene rocks (see Section 3 for further details). Increased monitoring, reconnaissance, and research in these units has the potential to further increase our understanding of the geographic heterogeneity in species’ responses to the extinction event and subsequent ecological recovery.

1.1.2 Angiosperm Diversification

The Cenozoic is a time interval characterized by diversification within extant families of flowering plants (Ramírez-Barahona et al., Reference Ramírez-Barahona, Sauquet and Magallón2020; Zuntini et al., Reference Zuntini, Carruthers and Maurin2024) and their rise to ecological dominance (Wing and Boucher, Reference Wing and Boucher1998; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Jarmillo and de la Parra2021). The Cenozoic strata of the USA contribute to our understanding of this diversification through documenting extinct genera with known (e.g., Florissantia; Manchester, Reference Manchester1992) or unknown (e.g., Palibinia; Manchester et al., Reference Manchester, Judd and Kodrul2024) familial affinities, and early occurrences of extant genera that persist (e.g., Alnus; Forest et al., Reference Forest, Savolainen and Chase2005) or have gone extinct (e.g., Pterocarya; Stults et al., Reference Stults, Tiffney and Axsmith2022) from the continent. Collectively, these occurrences illustrate that North American vegetation has been deeply affected by extinction, and that the extant flora is composed of families and genera with heterogeneous ages of origin and evolutionary histories.

Fossil plants provide insight into extinction by preserving combinations of morphological characters that cannot be observed today and by occurring beyond the geographic range of their nearest living relatives. Extinct genera with morphologies consistent with living angiosperm families but not matching any extant genus within them formed a prominent component of Paleogene North American floras and cooccurred with or in some cases predated the first occurrences of confamilial extant genera. Paleobowditchia, an extinct genus in the Fabaceae subfamily Papilionoideae, whose type locality is in the Lamar River Formation at Yellowstone National Park (Herendeen et al., Reference Herendeen, Cardoso, Herrera and Wing2022), attests to the latter pattern, and Cedrelospermum, an extinct genus of the Ulmaceae that cooccurs with Ulmus in the fossiliferous shales of Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument (Manchester, Reference Manchester1989a), attests to the former. Several extant families appeared and disappeared from the North American flora over the course of the Cenozoic, and others lost phylogenetic diversity (number of higher taxa below family rank) through the extinction of genera that persist outside of North America today. The Cercidiphyllaceae and Trochodendraceae, monogeneric families now restricted to eastern Asia, are represented by extant and extinct genera in the North American fossil record that grew as common components of Paleocene–Miocene floras of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and Pacific Northwest (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Manchester and Dilcher1991; Manchester et al., Reference Manchester, Crane and Dilcher1991), including those preserved in Paleocene strata of Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota (Fastovsky and McSweeney, Reference Fastovsky and McSweeney1991), and Eocene strata of Glacier National Park in Montana (Smith, Reference Smith2023). The Juglandaceae, represented in North America today by Juglans and Carya, were once represented by three additional extant genera that today occur only in Eurasia (Manchester, Reference Manchester1989b), as well as numerous extinct genera (Manchester, Reference Manchester1989b, Reference Manchester1991). Thus, despite its ecological importance in the extant North American flora, the Juglandaceae represent a prominent example of a lineage that lost phylogenetic diversity in North America over the course of the Cenozoic.

Extinction did not affect all lineages equally over the course of the Cenozoic, and the US fossil record also illustrates the capacity of plant families and genera to persist and diversify over multimillion-year timescales. Acer and Quercus are diverse and ecologically dominant genera today, with evolutionary roots deep in the Cenozoic: Occurrences in the Late Paleocene–Early Eocene Copper Lake Formation in Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska (Acer; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987) and the Middle Eocene (44 Ma) Clarno Nut Beds of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (Quercus; Manchester, Reference Manchester1994) are among the earliest records of each genus. At the family level, fossil histories of the Betulaceae and Rosaceae indicate a net accumulation of higher-level taxa throughout the Cenozoic, a marked contrast to the trajectory of phylogenetic diversity in the Juglandaceae. The Rosaceae today are among the most diverse families in North America (ca. 700 species), and appear to have first established this diversity during the Eocene (DeVore and Pigg, Reference DeVore and Pigg2007). Latest Early Eocene floras from the Okanogan Highlands of eastern Washington and British Columbia include the oldest known Prunus and Oemleria flowers (Benedict et al., Reference Benedict, DeVore and Pigg2011), along with early or first occurrences of other rosaceous taxa (Wolfe and Wehr, Reference Wolfe and Wehr1988), and the Late Eocene flora of Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument includes early occurrences of Rosa, Cercocarpus, and several additional rosaceous taxa (Manchester, Reference Manchester2001). In the Betulaceae, all five extant North American genera have persisted since the Paleogene (Crane, Reference Crane1989; Forest et al., Reference Forest, Savolainen and Chase2005), and some (e.g., Carpinus, Corylus) show a similar pattern of stratigraphic occurrence to the Rosaceae, with first occurrences in the Okanogan Highlands (Pigg et al., Reference Pigg, Manchester and Wehr2003; Pigg and DeVore, Reference Pigg and DeVore2010).

1.1.3 Climate Change

Global climate of the Cenozoic transitioned from a high-CO2 greenhouse world that lacked polar ice sheets in the Paleocene and Eocene to a low-CO2 world with southern ice sheets beginning in the late Eocene and northern ice sheets beginning in the Pliocene (Zachos et al., Reference Zachos, Dickens and Zeebe2008; Westerhold et al., Reference Westerhold, Marwan and Drury2020; Cenozoic CO2 Proxy Integration Project (CenCOPIP) Consortium, 2023). Superimposed on this general trend are rapid and transient warming episodes, such as PETM and other Early Eocene hyperthermal events, prolonged warm periods such as Early and Middle Eocene climatic optima and the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, and abrupt shifts in mean climate state such as the Eocene–Oligocene Transition (EOT), Middle Miocene Climatic Transition, and glacial–interglacial cycles of the Quaternary. Fossil floras of appropriate stratigraphic position document two principal patterns in the response of plants to this climatic history: (1) rapid or cyclic climate changes are matched by rapid plant migration, leading to large taxonomic turnover but low rates of extinction; and (2) prolonged or abrupt and directional climate changes are associated with long-term shifts in plant community composition mediated by immigration and/or local extinction and speciation.

The response of North American plant communities to climatic perturbations lasting less than a million years is best known from two time intervals: the PETM, a period of ca. 200,000 years beginning at the Paleocene–Eocene boundary (56 Ma) that was characterized by 4–8°C of greenhouse warming (McInerney and Wing, Reference McInerney and Wing2011); and the last ca. 800,000 years, characterized by large fluctuations in polar ice volume and atmospheric CO2 levels (Petit et al., Reference Petit and Raynaud1999; Lüthi et al., Reference Lüthi, Le Floch and Bereiter2008). Floral records from the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming indicate that the predominant response of woody plants to the climate changes of the PETM was through reversible range shifts; however, local extirpations and immigrations occurred as well, giving forth to novel earliest Eocene plant associations (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Harrington and Smith2005; Wing and Currano, Reference Wing and Currano2013; Korasidis and Wing, Reference Korasidis and Wing2023). A similar response of eastern North American vegetation to cycles of icesheet expansion and retraction during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene has been documented from pollen cores taken from a large network of glacial lakes, including one within Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts (Winkler, Reference Winkler1985). Collectively, these records illustrate that the formation and dissolution of plant associations reflect individualistic interactions between species and climatic factors (Jackson and Overpeck, Reference Jackson and Overpeck2000).

In contrast, plant responses to climatic changes occurring over multimillion-year timescales are characterized by widespread extinction and directional shifts in floristic composition and/or vegetation structure. This pattern is well-documented in the Eocene floras (Leopold and MacGinitie, Reference Leopold, MacGinitie and Graham1972; Wing, Reference Wing1987) of the Rocky Mountain Region that record a progressive loss of Late Paleocene and Early Eocene taxa, many with East Asian biogeographic affinities (e.g., Metasequoia; Wing, Reference Wing1987) and influx of taxa with neotropical biogeographic affinities (e.g., Myrtaceae; Manchester et al., Reference Manchester, Dilcher and Wing1998). This shift in floristic composition has been correlated with regional drying in the Rocky Mountain Region and differs from the Eocene record of the Pacific Northwest, which retained a wetter climate and tropical to subtropical “East Asian” lineages up until the Late Eocene–Early Oligocene (Leopold and MacGinitie, Reference Leopold, MacGinitie and Graham1972; DeVore and Pigg, Reference DeVore and Pigg2010). The Middle Eocene (44 Ma) Clarno and Early Oligocene (33 Ma) Bridge Creek floras from Oregon, preserved in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, illustrate major changes in the makeup of the Pacific Northwest flora associated with a gradual trend of climatic cooling and drying in the Middle–Late Eocene, punctuated by the abrupt climatic deterioration of the EOT (Retallack, Reference Retallack, Prothero and Berggren1992; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe, Prothero and Berggren1992). This period of climate change has been interpreted as a major factor in the regional replacement of evergreen angiosperms by deciduous angiosperms and conifers, and the regional extinction of numerous taxa that persist today in the eastern USA and eastern Asia (MacGinitie, Reference MacGinitie1953; Meyer and Manchester, Reference Meyer and Manchester1997).

1.1.4 Intercontinental Dispersal

Three land connections influenced the potential for intercontinental dispersal via biogeographic corridors during the Cenozoic in North America: the Bering Land Bridge (BLB) between Alaska and Russia; the North Atlantic Land Bridge (NALB) between eastern North America and Western Europe; and the Isthmus of Panama that connected the Americas. The BLB lay at high northern latitudes, likely between 60 and 80°N, and served as a viable corridor throughout the Cenozoic, despite variability in the degree of continuity and local climate of land across the Bering Strait (Tiffney and Manchester, Reference Manchester2001). Migration across the NALB is hypothesized to have occurred across a northern pathway, Svalbard to Greenland to Ellesmere Island (McKenna, Reference McKenna1975, Reference McKenna, Bott, Saxov, Talwani and Thiede1983), and a southern pathway, Scotland to the Faroe Islands to Iceland to Greenland to North America (Tiffney, Reference Tiffney1985; Tiffney and Manchester, Reference Manchester2001; Denk et al., Reference Denk, Grímsson, Zetter, Símonarson, 96Landman and Harries2011). Current tectonic and paleobotanical evidence (reviewed by Denk et al., Reference Denk, Grímsson, Zetter, Símonarson, 96Landman and Harries2011) suggests that migration via the southern NALB occurred up until the Late Miocene (10–6 Ma). The Isthmus of Panama formed a persistent terrestrial landscape between Central and North America around 3.5 Ma, and was the result of a complex sequence of events, beginning with the formation of a large island in the Late Eocene (Jaramillo, Reference Jaramillo, Hoorn, Perrigo and Antonelli2018). The geologic history of the land bridge and the frequency of biotic interchange prior to its formation is an active area of debate (Montes et al., Reference Montes, Cardona and Jaramillo2015; O’Dea et al., Reference O’Dea, Lessios and Coates2016).

The inference of migration routes for taxa that now or once occurred on multiple Laurasian (North America, Europe, Asia) continents are based on the geo-stratigraphic distribution of fossil taxa and the present distribution of their living relatives (Manchester, Reference Manchester1999). The fossil record of North America includes immigrant taxa with earliest stratigraphic occurrences in Europe or Asia (e.g., Betula), supporting dispersal into North America by the NALB or BLB, as well as migrant taxa with earliest occurrences in North America that subsequently occur in Asia and Europe (e.g., Cornus). Among extant lineages, legacies of intercontinental dispersal have contributed to modern Holarctic distributions (e.g., Acer), and Asian–North American disjunctions (e.g., Nyssa). Differential extinction following range expansion via past dispersal corridors has also produced patterns of paleo-endemism among taxa that were widespread as fossils but only persist on one continent (e.g., Eucommia in Asia, Comptonia in North America), and “range-reversal” for taxa that persist on a different continent from their earliest fossil occurrence (e.g., Cyclocarya).

Early and Middle Eocene floras preserved in several Alaskan national parks provide insight into the vegetation structure near the migration corridor of the BLB and provide the opportunity to catch modern Holarctic taxa in the act of migration. Early Eocene plants from Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve include lineages that are mainly tropical and evergreen today, such as the Icacinaceae, Lauraceae, and Annonaceae (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1966, Reference Wolfe1977), implying that the greenhouse climate of the Early Cenozoic allowed some members of these families to reach high latitudes despite the increased seasonality of insolation. Further systematic and paleoecological study of the floras within Alaskan national parks has the potential to improve our understanding of the origin of modern biogeographic patterns among Northern Hemisphere plants and of ecosystem function within non-analog high-latitude evergreen floras.

2 Scope of the Review

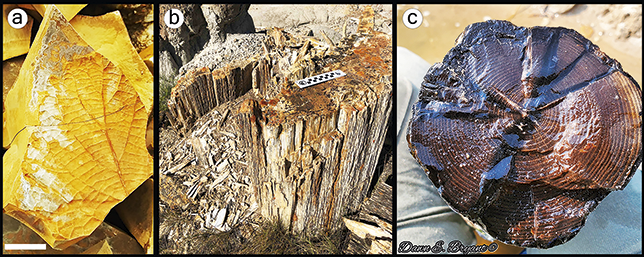

Our inventory focuses on occurrences of plant macrofossils (megafossils) in Cenozoic sedimentary rock formations and unlithified sediments that fall within the boundaries of national parks, historical parks, scenic and heritage trails, monuments, preserves, recreation areas, and other types of units administered by the National Park Service. We define plant macrofossils as macroscopic physical evidence of past plant life (Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Tweet, Visaggi and Hodnett2024) and include permineralizations, charcoalifications, and compressions and impressions of leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, stems, branches, and wood. In addition, we selectively include records of plant microfossils, such as pollen, spores, phytoliths, and dispersed cuticle from cores and outcrops and plant ichnofossils and related sedimentary structures, such as root traces and other rhizoliths. The microfossil and ichnofossil records are here reported in instances where their presence indicates potential for macrofossil discovery or has contributed to paleoenvironmental interpretation of plant macrofossil assemblages. We exclude macrofossil occurrences documented from packrat middens (reviewed by Tweet et al., Reference Tweet, Santucci and Hunt2012a) and provide less thorough coverage of the substantial body of literature devoted to the Quaternary pollen record.

To compile the NPS Cenozoic plant fossil inventory, we searched peer-reviewed scientific journals, NPS archives (internal park communications, internal reports, etc.), geologic maps, paleontological inventory reports, USGS internal memos (“E&R reports”), popular science articles, museum collection databases, and other relevant databases such as the Alaska Paleontological Database (www.alaskafossil.org/) and the Florissant Fossil Database (https://flfo-search.colorado.edu/). Potential records were checked against NPS boundaries to determine whether a given occurrence was within or outside a given park unit, and for confirmed fossils, we conducted a secondary literature search to the best of our abilities to find associated geochronologic, stratigraphic, taphonomic, and taxonomic information. We present park-wide summaries for the Quaternary and each epoch of the Paleogene and Neogene in Supplementary Tables 1–6 (Supplementary Tables are available to access online at www.cambridge.org/matel-et-al). Text summaries are presented later, organized geographically by the seven NPS legacy regions, and within regions by the 32 Inventory and Monitoring networks.

3 Park Inventories

3.1 Alaska Region

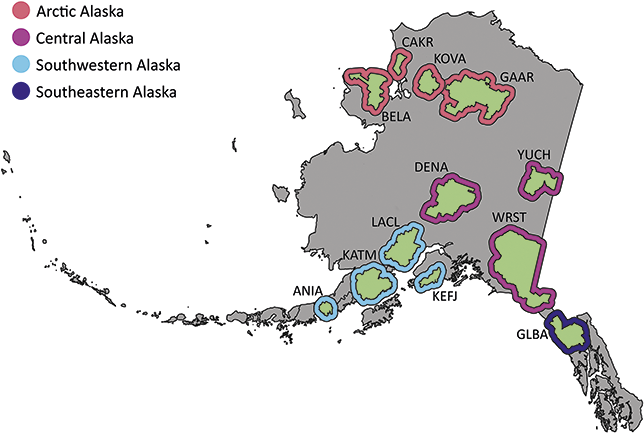

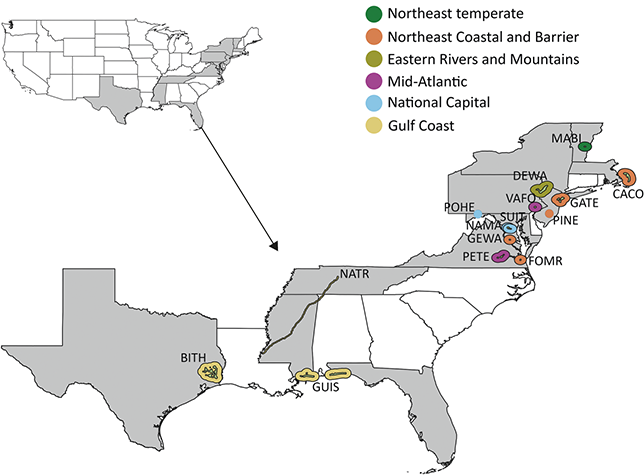

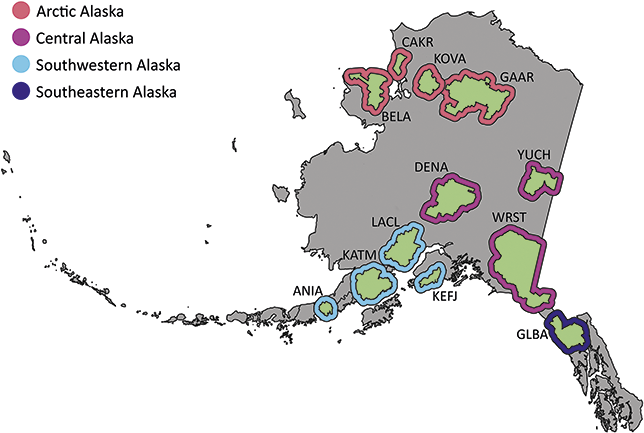

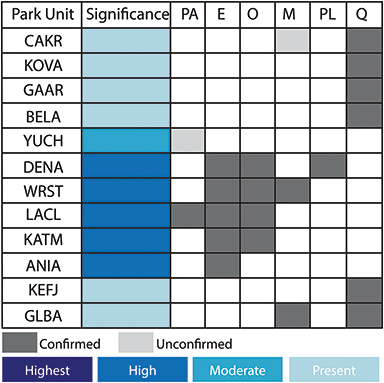

The Alaska Region includes 16 NPS units divided among four inventory and monitoring networks and encompasses 54 million acres, approximately two-thirds of the land area managed by the NPS (Figure 1). Of these 16 parks, 11 contain confirmed records of Cenozoic plant macrofossils, and Yukon–Charley Rivers National Preserve likely contains undocumented Cenozoic plant macrofossils (Kenworthy and Santucci, Reference Kenworthy and Santucci2003; Santucci and Kenworthy, Reference Santucci and Kenworthy2008; Elder et al., Reference Elder, Santucci, Kenworthy, Blodgett and McKenna2009; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011).

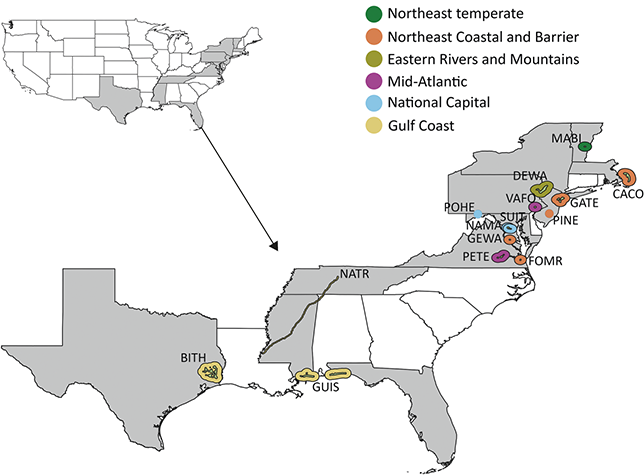

Figure 1 Map of the 11 NPS units with confirmed Cenozoic paleobotanical resources in the Alaska Region and one unit (YUCH) with potential resources. Interior green shading illustrates the area enclosed by the perimeter of park boundaries plus a 3 km buffer, and exterior shading colored by inventory and monitoring represents the area enclosed by the perimeter of park boundaries plus a 30 km buffer. Unit acronyms are generally formed from the first four letters of one-word unit names (e.g., Katmai National Park and Preserve = KATM) and the first two letters of the first two words for multiple-word unit names (e.g., Bering Land Bridge National Preserve = BELA).

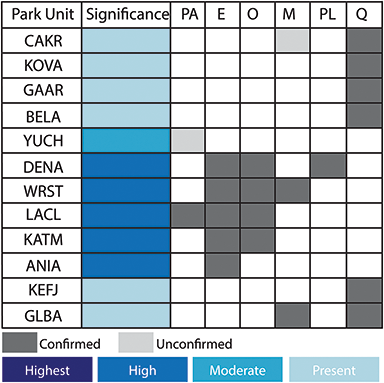

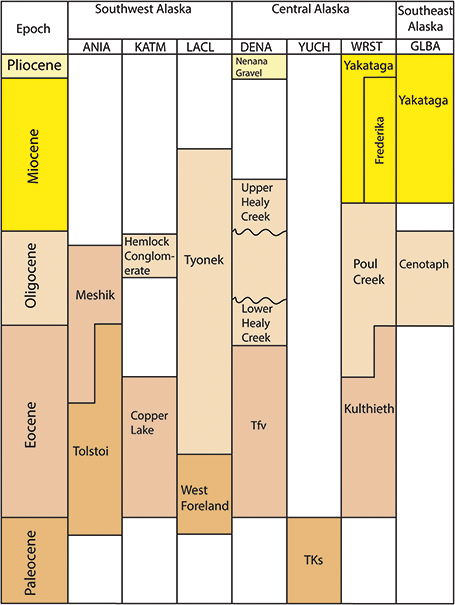

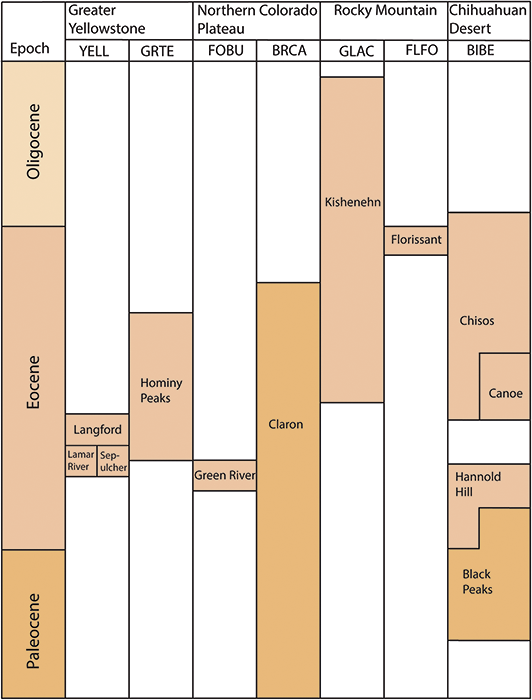

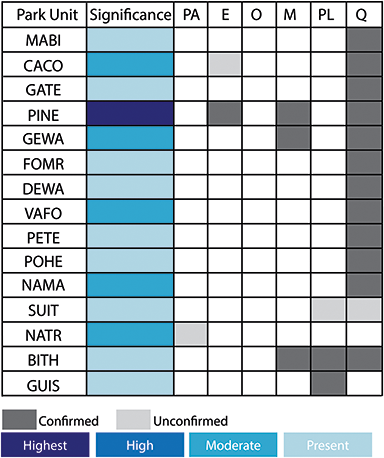

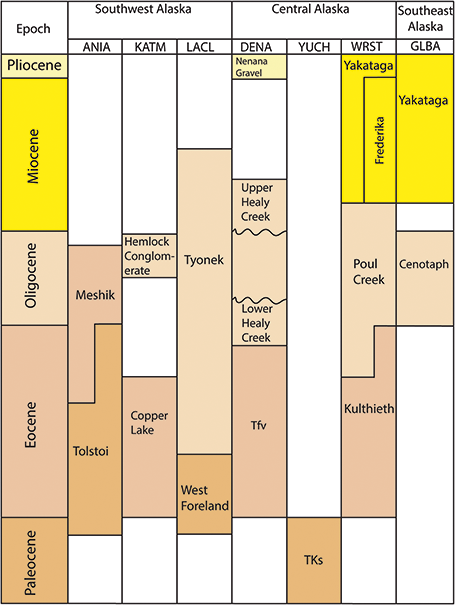

Alaskan national parks preserve highly significant paleobotanical resources that provide insight into the evolution of the Alaskan flora over the whole of the Cenozoic (Figure 2) but have especially enriched the paleobotanical understanding of arctic floras during the Eocene and Oligocene (Figure 3). Early Eocene floras from the Kulthieth Formation in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve as well as floras from the Kushtaka Formation to the south document “boreotopical” forests, a non-analog vegetation type characterized by rainforest-like leaf physiognomy and the presence of some lineages now restricted to the tropics and subtropics of Asia (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977, Reference Wolfe, Boulter and Fisher1994a, Reference Wolfe1994b; Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998; Graham, Reference Graham1999). Middle and Late Eocene floras are known from Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve and Katmai National Park and Preserve on the Alaskan Peninsula (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1966), as well as from the Katalla and Rex Creek floras of Central Alaska (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe, Prothero and Berggren1992), and illustrate a step in the modernization of the flora, with an increased presence of the broadleaf deciduous lineages (e.g., Betulaceae) characteristic of modern North American forests. Oligocene and Miocene floras, known from NPS units on the Alaskan Peninsula and Central Alaska as well as a number of sites outside of park boundaries (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977; Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998), represent further modernization of the flora by complete loss of broadleaf evergreen lineages and their replacement by broadleaf deciduous plants and conifers, with an apparent peak in the diversity of the broadleaf deciduous component during the Early Miocene (Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1980).

Figure 2 Summary of the temporal distribution and significance of Cenozoic paleobotanical resources in the Alaska Region. The significance rating of individual parks represents the aggregate significance of all resources within that park and was scored based on criteria such as holotype specimens, plant fossil abundance and preservation quality, and number of publications referencing primary paleobotanical data from the park.

Figure 3 Stratigraphic chart of Tertiary plant-fossil–bearing formations in the Alaska Region.

Numerous additional Alaskan paleofloras are preserved outside of the NPS and add important context for interpreting and managing park resources. Much of the primary documentation of these resources comes from the monographic works of Swiss paleobotanist Oswald Heer and USGS paleobotanists Arthur Hollick and Jack Wolfe (Heer, Reference Heer1869; Hollick, Reference Hollick1930, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1966, Reference Wolfe1977; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966), and the Tertiary (used here for convenience for pre-Quaternary Cenozoic) record in Alaska has been reviewed several times (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe and Graham1972; Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998; Graham, Reference Graham1999).

3.1.1 Arctic Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network

Cape Krusenstern National Monument

Cape Krusenstern National Monument contains approximately 650,000 acres of land along the northwestern coast of Alaska (Figure 1). The monument was established in 1978 to protect a series of beach ridges along the southern coast (Lanik et al., Reference Lanik, Swanson and Karpilo2019). Unidentified fossil wood recovered from these ridges is the only report of paleobotanical material within the park (Mason and Ludwig, Reference Mason and Ludwig1990).

Kobuk Valley National Park

Kobuk Valley National Park preserves approximately 1.75 million acres of the Kobuk River Valley and borders Noatak National Preserve to the north (Figure 1). The only report of Cenozoic paleobotanical material within the park comes from Epiguruk Bluffs, a locality on the Kobuk River containing fossil vertebrates, mollusks, and wood. Wood samples used for radiocarbon dating constrain the age of the deposits to 37,000–14,000 years before present (ybp) (Hamilton and Ashley, 1983; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Ashley, Reed and van Etten1984, Reference Hamilton, Ashley, Reed and Schweger1993; Lanik et al., Reference Lanik, Swanson and Karpilo2019).

Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve

Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve (GAAR) lies entirely north of the Arctic Circle and is the nation’s second largest national park, encompassing nearly 8.5 million acres (Figure 1). Paleobotanical material collected from GAAR includes plant fragments from unnamed lacustrine sediments on the north side of Noatak Valley just north of Okturak Creek (Forester, Reference Forester1979) and fossil wood from overbank deposits of the west bank of the Killik River (Repenning, Reference Repenning1974).

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve (BELA) covers 2.8 million acres of tundra on the Seward Peninsula of Alaska (Figure 1). Quaternary paleobotanical resources within BELA have been discovered in eroding permafrost sediments (pingo deposits), tephra deposits of the Devil Mountain maar exposed on banks of thermokarst lakes, and in gravel deposits along the banks of the Noxapaga River (Spackman, Reference Spackman1951; Goetchus and Birks, Reference Goetcheus and Birks2001; Wetterich et al., Reference Wetterich, Grosse and Schirrmeister2012). Just east of BELA in the vicinity of Lava Camp Mine, is a volcanic lava flow dated to 5.7 ± 0.2 Ma (Late Miocene) that preserved a forested floodplain (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Matthews, Wolfe and Silberman1971). The museum collection at BELA holds a fossil leaf and fossil liverwort specimen, but these are not linked to locality or age information (Lanik et al., Reference Lanik, Swanson and Karpilo2019).

Lava Camp Mine: The Lava Camp Mine locality (USGS 11190) in the Imuruk River Valley just east of the park boundary preserves plant macrofossils in alluvial deposits that were buried under an upper Miocene (5.7 Ma) basaltic lava flow (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Matthews, Wolfe and Silberman1971). The macrofossil assemblage represents a floodplain forest composed largely of Picea and Betula. Its taxonomic composition is similar to approximately contemporaneous deposits from the Cook Inlet Region, and together these floras represent the Clamgulchian (Late Miocene–Pliocene) Alaskan time-stratigraphic stage (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Matthews, Wolfe and Silberman1971). Macrofossil types include needle leaves, ovulate cones, and seeds; taxa include Picea (three spp.), Pinus, Tsuga, Betula, Symphoricarpos, Vaccinium, Carex, and Cyperus (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Matthews, Wolfe and Silberman1971). The locality also preserves a diverse insect and arachnid assemblage consisting of at least 83 species (Elias et al., Reference Elias, Kuzmina and Kiselyov2006). Parts of the southeast corner of the park contain upper Tertiary (Neogene) volcanic deposits (map unit Qtv; NPS, 2015 [unpublished digital geologic map]), which might preserve similar communities.

Noxopaga River: Fossil wood identified as Populus and Picea was recovered from a 12 m (40 ft) section of Quaternary gravel deposits exposed on the west bank of the Noxopaga River, between Goose and Bussard creeks (Spackman, Reference Spackman1951).

Pingo Deposits: Wetterich et al. (Reference Wetterich, Grosse and Schirrmeister2012) collected samples of pingo deposits from Whitefish maar, Devil Mountain maar, and North and South Killeak maars in the Cape Espenberg lowlands (within BELA) of the Seward Peninsula and from nine other localities (outside BELA) in Arctic and Central Alaska. The combined age range of these samples spans 46,615–8,986 ybp, and the oldest sediments containing identifiable plant macrofossils were constrained to 32,870 ± 220 ybp. The macrofossil assemblage includes twigs, leaves, seeds, and fruits representing gymnosperms and woody and herbaceous angiosperms. Common plant genera include Betula, Carex, Hippuris, Potamogeton, Potentilla, and various members of the Ericaceae.

Devil Mountain Lake Tephra: The Devil Mountain Lake tephra buried approximately 2500 km2 (970 mi2) of land surface, reaching a maximum thickness of 1 m (3 ft) over an approximately 1200 km2 (460 mi2) region (Goetchus and Birks, Reference Goetcheus and Birks2001). The tephra was subsequently capped by loess, preserving an in situ tundra landscape, and the sequence has recently become exposed along the banks of thermokarst lakes. Plant macrofossils and organic material used for radiocarbon dating were sampled from twelve different localities in the Cape Espenberg–Devil Mountain area and produced an age range of 18,260–17,700 radiocarbon ybp (ca. 21,500 calendar ybp). This age range places the deposits within the thermal minimum of the Last Glacial Maximum (28,000–14,000 ybp). The macrofossil assemblages are interpreted to represent a sedge-dominated, herb-rich tundra grassland based on the relative ground cover of moss, graminoids, forbs, and shrubs in point-transect collections and the composition of seeds and fruits isolated from sieved sediment. Representative taxa include Carex, Salix, Papaver, and Potentilla (Goetchus and Birks, Reference Goetcheus and Birks2001).

3.1.2 Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network

Yukon–Charley Rivers National Preserve

Yukon–Charley Rivers National Preserve (YUCH) encompasses approximately 2.5 million acres (Figure 1). This area protects about 161 km (100 mi) of the Yukon River and the entire Charley River basin. The park’s geology spans nearly 1.3 billion years of Earth’s history, from the Precambrian to the Cenozoic (Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). The park does not contain any confirmed Cenozoic paleobotanical resources; however, it does contain exposures of Upper Cretaceous and Paleocene rocks (map unit TKs; Figure 4), which have yielded Paleocene plant fossils just outside of the park’s southern boundary (Hollick, Reference Hollick1930, Reference Hollick1936; Mertie, Reference Mertie1942) and Cretaceous plant fossils from within the park (Knoll, Reference Knoll and Young1976; Tiffney, Reference Tiffney and Young1976; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Fanti, Hults and Hasiotis2014).

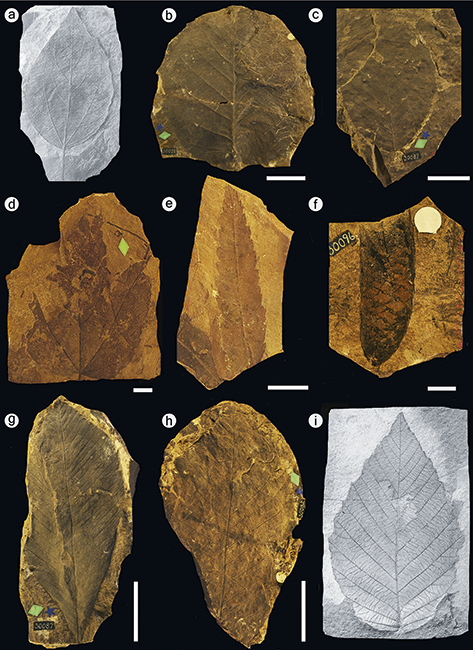

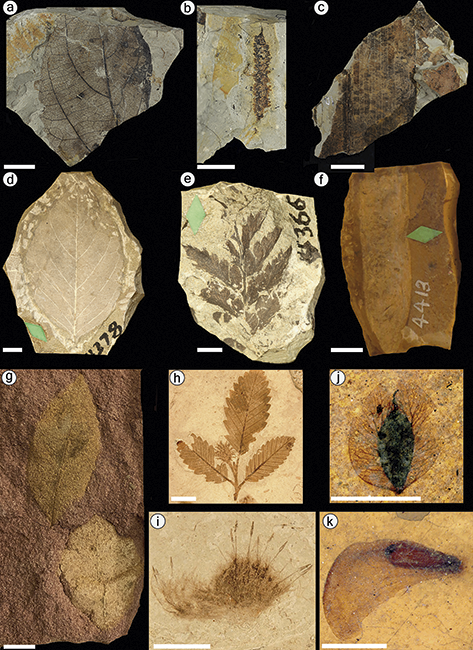

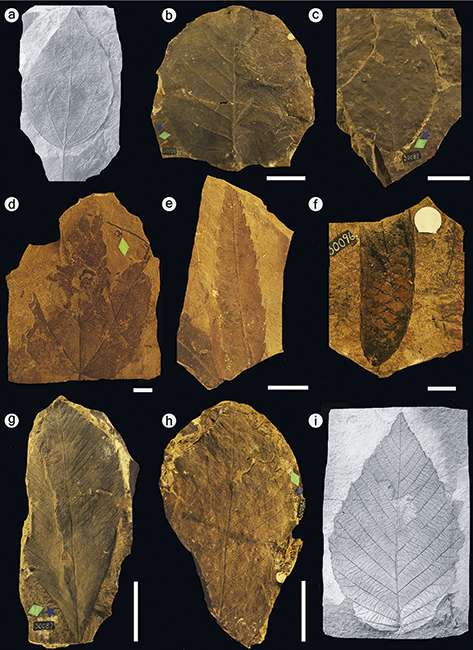

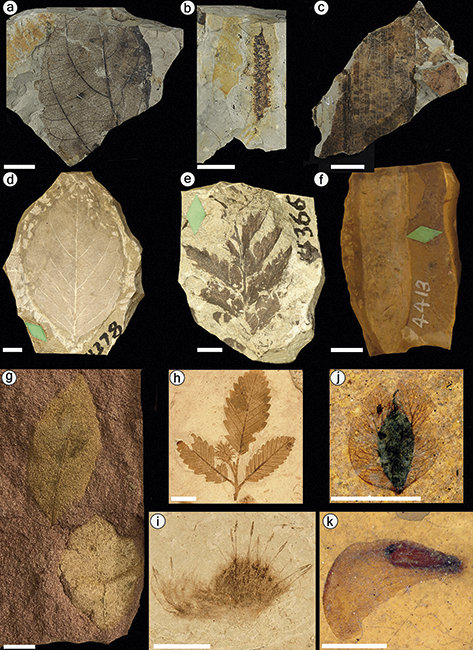

Figure 4 Fossil plants from the Alaska Region. (a) Paratinomiscium conditionalis, a leaf belonging to the Menispermaceae recovered from the Yakutat Bay locality in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve. Image from Hollick (Reference Hollick1936). (b) Corylus harrimani Knowlton collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 5 cm. (c) Ptermospermites alaskana collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 5 cm. (d) Holotype of Acer disputabilis collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 1 cm. (e) Myrica banksiaefolia var. curta collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 1 cm. (f) Specimen of Picea harrimani collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 1 cm. (g) Holotype specimen of Aesculus arctica collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 5 cm. (h) Holotype specimen of Hicoria magnifica collected from Katmai National Park and Preserve. Scale bar = 5 cm. (i) Alnus evidens, recovered from the Kukak Bay locality in Katmai National Park and Preserve. This taxon was formerly placed in the genus Corylus. Image from Hollick (Reference Hollick1936).

Unnamed unit (TKs): Plant macrofossils and palynomorphs are preserved in a continuous Upper Cretaceous to lower Cenozoic depositional sequence mapped as unit TKd (Foster, Reference Foster1976) or, more commonly, as TKs (Mertie, Reference Mertie1930; Knoll, Reference Knoll and Young1976; Dover and Miyaoka, Reference Dover and Miyaoka1988; Miyaoka, Reference Miyaoka1990). This unit is laterally continuous from the southeast corner of the park (near Eagle, Alaska) to the northwest of the park (south of Circle, Alaska). It forms a belt approximately 145 km (90 mi) long and parallel to the course of the Yukon River, and its Paleogene deposits are thickest and most laterally extensive in its southern and eastern regions (Mertie, Reference Mertie1942; Tiffney, Reference Tiffney and Young1976). The subdivision of the sequence represented by map unit TKs into smaller stratigraphic units is likely warranted but has been hindered by the unit’s large areal extent, variable lithology, and widely spaced fossil localities (Tiffney, Reference Tiffney and Young1976).

At least 28 plant macrofossil localities are documented from TKs in the Eagle–Circle district (Mertie, Reference Mertie1942). Many of the early discoveries of fossil localities from this formation occurred in the southeastern region of YUCH and just outside the park’s southern boundary (Hollick, Reference Hollick1930, Reference Hollick1936; Mertie, Reference Mertie1942). Among these localities are several Early Cenozoic sites along the banks of Seventymile Creek and one of its tributaries, Bryant Creek, which have yielded well-preserved angiosperm leaf fossils, several of which were described as new species (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936). Geologic maps indicate that there is significant potential to find similar localities within the southeastern region of YUCH, which is approximately 8 km (5 mi) to the north.

Denali National Park and Preserve

Denali National Park and Preserve (DENA), encompasses approximately 6 million acres and protects the large glaciers of the Alaska range as well as a diverse megafauna (Figure 1). The park’s geology is complex, and study and interpretation by the NPS, USGS, and academic researchers are ongoing (Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986; Tomsich et al., Reference Tomsich, McCarthy, Fowell and Sunderlin2010; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). Cenozoic paleobotanical material has been recovered from at least three different formations within DENA: an unnamed Lower Eocene map unit labeled unit Tfv, the Upper Oligocene Healy Creek Formation, and the Upper Miocene to Pliocene Nenana Gravel (Figure 4; Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). The Cantwell Formation, once considered to be Paleocene in age, has also yielded plant fossils within DENA; however, recent studies (Tomisch et al., Reference Tomsich, McCarthy, Fowell and Sunderlin2010) indicate a Late Cretaceous age for the Cantwell Formation.

Fluviatile and subordinate volcanic rocks (Eocene?), unit Tfv: While developing a geologic map for the Healy Quadrangle, Csejtey et al. (Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986) documented two plant fossil localities within DENA that are ascribed to an unnamed map unit labeled Tfv. These localities are in the eastern-central area of the park between Costello Creek and the western fork of the Chulitna River (see Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986, for further details). The proposed Eocene age of this unit is based only on its sparse plant fossils and correlation with other Early Cenozoic Alaskan fossil assemblages. Plant fossils from this unnamed unit were found in a shale interbed within conglomerate and include needles of Metasequoia occidentalis and fragments of broad-leaved dicotyledons (Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986). This sample was studied by paleobotanist Jack Wolfe, who suggested that the dicotyledonous component represented a plant community younger than the Cantwell Formation, which he then believed to be Paleocene in age (J. A. Wolfe, pers. comm. in Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986).

Healy Creek Formation: The Healy Creek Formation is the basal unit of the Usibelli Group (also known as the Tertiary coal-bearing group, or map unit Tcu of Nenana Coalfield), which encompasses five formations that span from the Oligocene to Miocene (Figure 4; Wahrhaftig et al., Reference Wahrhaftig, Wolfe, Leopold and Lanphere1969). A collection of plant fossils assigned to this group was made at the top of the section exposed at Dunkle Coal Mine, in the same east-central region of DENA, which also yielded plant fossils from the unnamed unit (unit Tfv) already discussed (Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen and Cox1986). This assemblage includes twelve species described from leaf compressions and impressions. Cercidiphyllum crenatum and Alnus evidens are notable from a biostratigraphic standpoint and suggest that the assemblage belongs to the Angoonian (Late Oligocene) Alaskan time-stratigraphic stage (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966). Other taxa present in this collection include the fern Onoclea, the gymnosperm Metasequoia cf. glyptostroboides, and broad-leaved angiosperms such as Betula, Salix, Populus, and Corylus. Elsewhere in DENA, Bruce Reed collected an assemblage including Metasequoia cf. glyptostoboides, Alnus evidens, “Carya” magnifica, Equisetum, and undetermined species of Alnus and Populus at USGS localities 11123–11125. The localities are assigned to an unnamed unit composed of conglomerate, sandstone, and siltstone interpreted as Oligocene in age on the basis of its plant fossils (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1968). It is possible that this assemblage was recovered from unmapped exposures of the Healy Creek Formation.

Outside of DENA, in the Nenana Coalfield, the Healy Creek Formation has yielded similar assemblages to those recovered from the park; these assemblages also include Ulmus and Quercus (Wahrhaftig et al., Reference Wahrhaftig, Wolfe, Leopold and Lanphere1969). In the Nenana Coalfield, the Healy Creek deposits are in conformable contact with other paleobotanically productive formations of the Usibelli Group, and there is potential to discover similar sequences in the northeastern region of DENA where the Usibelli Group is exposed in the Savage River drainage and near Sable Pass.

Nenana Gravel: The Nenana Gravel includes conglomerate, sandstone, claystone, and lignite that accumulated during uplift and erosion of the Alaska Range in the Pliocene. The unit is exposed along portions of the park road in the park’s northeast corner (Csejtey et al., Reference Csejtey, Mullen, Cox and Stricker1992; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dover and Bradley1998; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). Within DENA, the only paleobotanical materials recovered from the gravel to date are a Picea cone and carbonized wood in bajada deposits (Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). Leopold and Liu (Reference Leopold and Liu1994) reported carbonized plant fragments and fossil fruits of Trapa from probable deposits of the Nenana Gravel northeast of the park near Ferry, Alaska.

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve (WRST) in southeast Alaska is the largest national park in the USA, encompassing more than 13 million acres (Figure 1). The park was established to conserve a region that includes three major mountain ranges – the Chugach, St. Elias, and Wrangell mountains – numerous glaciers, and wildlife habitat ranging from temperate rainforest to tundra. The park also contains significant Cenozoic paleobotanical resources. In 1905, R. S. Tarr was the first to collect plant fossils within what is now WRST, from outcrops of the Paleocene–Eocene Kulthieth Formation along Esker Stream near Yakutat Bay. The collection from this locality was later studied by USGS paleobotanists Arthur Hollick and Jack Wolfe, yielding type specimens of several species (Figure 4; Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Later collecting efforts, also led by the USGS, yielded plant specimens from three additional formations: the Eocene–Miocene Poul Creek Formation, the Miocene Frederika Formation, and the Miocene–Pleistocene Yakataga Formation (Figure 4; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977; Fremd et al., Reference Fremd, Dunn, Rickabaugh, Graham and Rosenkrans2003; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011).

Kulthieth Formation: Fossil plants from the Kulthieth Formation were recovered in a calcareous sandstone layer at USGS paleobotanical locality 3879 along Esker Stream, which flows into Yakutat Bay in the southeast corner of the park (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936). The stratigraphic position of this locality within the Kulthieth Formation is uncertain. Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1977) initially referred the Kulthieth Formation to the Middle Eocene based on mollusk fossils occurring in intertonguing marine rocks (Marincovich and McCoy, Reference Marincovich and McCoy1984), but its planktonic microfossils indicate an Early Eocene age, potentially within the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe, Boulter and Fisher1994a). The fossil assemblage collected at Esker Stream includes ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms represented by leaf compressions and impressions and one fossil endocarp (Figure 4). This locality produced type specimens of several species that belong to angiosperm families that do not occur in Alaska today: Celastrus comparabilis Hollick in the Celastraceae, Paratinomiscium conditionalis in the Menispermaceae (Figure 4), and Paleophytocrene elytraeformis in the Icacinaceae; it also produced the lectotype specimen of an extinct species of wood fern, Dryopteris alaskana. Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1977) considered the fossil flora collected from the Kulthieth Formation to represent “Paratropical Rainforests” based on its high proportion of large and entire-margined leaves and the presence of the families Annonaceae and Icacinaceae, which mainly occur in the tropics today. Climate reconstructions based on leaf physiognomy of 54 species from the Kulthieth Formation estimate that the assemblage lived under the warmest climate of any Alaskan Paleogene flora, with a mean annual temperature of 19.4°C (66.9°F) (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe, Boulter and Fisher1994a).

Poul Creek Formation: Fossil plants from the Poul Creek Formation were collected from USGS paleobotanical locality 11185, which occurs near Marvine Glacier in the southeast corner of the park (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Molluscan biostratigraphy of the Poul Creek Formation suggests that its sediments were deposited between the Late Eocene and Early Miocene (Figure 3), and the presence of Alnus evidens at USGS 11185, an indicator of the Angoonian (Late Oligocene) floral stage in Alaska, suggests an Oligocene depositional age for the formation’s fossil-plant–bearing strata (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977; Marincovich and McCoy, Reference Marincovich and McCoy1984; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). Elsewhere, the Poul Creek Formation is known as a marine unit, but USGS 11185 occurs along a fault in which no marine fossils were found (Stoneley, Reference Stoneley1967; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). The plant remains recovered from the Poul Creek Formation are fossil leaves assigned to the angiosperms Alnus evidens and Cercidiphyllum crenatum and the gymnosperm Metasequoia glyptostroboides (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Outside of WRST, a well-preserved permineralized walnut, Juglans lacunosa, was illustrated from Poul Creek locality USGS 11182 (figure 48 p, q, in Manchester, Reference Manchester1987).

Frederika Formation: The Frederika Formation occurs in the Wrangell Volcanic Fields, and outcrops extend into the northern and eastern regions of the park (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Preller, Labay and Shew2006). The valley walls of a westward-flowing tributary of Frederika Creek (Skolai Creek) are the type area of the Frederika Formation and the location of USGS localities 9933, 9935, and 9927, each of which falls within park boundaries (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987). The Frederika Formation preserves paleobotanical material in a variety of depositional contexts, including paleosol sequences, thick coal beds, lacustrine deposits, and silty tuffaceous sandstones (Fremd et al., Reference Fremd, Dunn, Rickabaugh, Graham and Rosenkrans2003). The plant fossils recovered from the Frederika Formation in the Skolai Creek area include angiosperms common in temperate deciduous forests, such as Acer, Alnus, Betula, and Populus, as well as the conifers Pinus and Metasequoia (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1966; Santucci et al., Reference Santucci, Blodgett, Elder, Tweet and Kenworthy2011). Collectively, this assemblage suggests a Miocene age (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1966). Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1964) remarked that the Pinaceae are better represented in the Frederika Formation than in contemporaneous floras of Cook Inlet and speculated that the difference in plant composition could be linked to the greater topographic relief and elevation of the Wrangell Mountains during the Miocene.

Yakataga Formation: The Yakataga Formation mainly comprises marine sequences but includes two paleobotanical localities (USGS 11183 and 11184) established in strata that have a similar lithology to the marine beds (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Both localities are in the southeastern area of the park, near Yakutat Bay. The locality USGS 11183 occurs in exposures near Haenke Glacier and USGS 11184 occurs in the Pinnacle Hills area. Floral and faunal biostratigraphy of the Yakataga Formation exposures that produced the plant-fossil–bearing horizons suggest that they were deposited in the Miocene (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Respectively, USGS 11183 and 11184 were referred to the Seldovian (Early to Middle Miocene) and Homerian (Middle to Late Miocene) floral stages based on the presence of Alnus appsii and Carpinus cobbii (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1970, Reference Wolfe1977; Addicott et al., Reference Addicott, Winkler and Plafker1978). Fossil leaves of the fern Osmunda and the gymnosperm Metasequoia glyptostroboides were also recovered from the Yakataga Formation in WRST, and a fossil Fagus leaf was recovered from the Yakataga Formation in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve (see Section 3.1.4) (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977).

3.1.3 Southwest Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network

Lake Clark National Park and Preserve

Lake Clark National Park and Preserve (LACL) encompasses 4 million acres of a dynamic natural landscape renowned for its coastline along Cook Inlet, glaciers, glacial lakes, rugged mountain peaks, and two active volcanoes, Mount Iliamna and Mount Redoubt (Figure 1). The park preserves one of the most important Mesozoic marine fossil localities in Alaska at Fossil Point, located on the Cook Inlet coast in Tuxedni Bay (Kenworthy and Santucci, Reference Kenworthy and Santucci2003). Younger rocks of the Paleocene–Lower Eocene West Foreland Formation and the Oligocene–Middle Miocene Tyonek Formation also crop out along the Cook Inlet coast and contain plant macrofossils (Figure 3; Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966).

West Foreland Formation: Exposures of the West Foreland Formation on the north shore of Chinitna Bay in the Iniskin-Tuxedni Region have produced fossil wood and leaves from locality USGS 3505 (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Ruga et al., Reference Ruga, Lanik and Hults2020). The West Foreland Formation is considered to be Late Paleocene–Early Eocene in age based on its plant fossils (Magoon et al., Reference Magoon, Adkison and Chmelik1976a, citing an oral comm. with Wolfe). Calderwood and Fackler (Reference Calderwood and Fackler1972) considered it to be the basal formation of the Kenai Group, a sequence of botanically fossiliferous terrestrial deposits spanning the Upper Paleocene to the Pliocene. The holotype specimen of Ginkgo reniformis var. conformis Hollick was collected from USGS 3505, and other taxa also found at this locality include Ginkgo biloba, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, and Taxodium tinajorum (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966). Fossil tree stumps exposed on the north shore of Chinitna Bay were discovered in 2019. They have not been studied taxonomically (or otherwise) and should be a management priority because they are at high risk of being lost to erosion (Ruga et al., Reference Ruga, Lanik and Hults2020). An additional macrofossil locality of the West Foreland Formation has been found just north of the park boundary near Redoubt Point (Magoon et al., Reference Magoon, Adkison and Egbert1976b), and there is potential to find additional localities in the Iniskin-Tuxedni Region within LACL.

Tyonek Formation: USGS paleobotanical localities 9760, 9887, 11344, 11355, and 11367 were established from exposures of the Tyonek Formation within park boundaries at Redoubt Point (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987). Like the Kukak Bay localities in Katmai National Park and Preserve (see below), these deposits are considered to be Upper Oligocene based on the presence of taxa characteristic of the Angoonian floral stage, such as Alnus evidens and Corylus harrimanii (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hopkins and Leopold1966; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1980). Other taxa collected from the Redoubt Point flora include the conifers, Glyptostrobus europaeus and Metasequoia glyptostroboides, and angiosperms, Vaccinium, Populus cf. kenaina, Carpinus cappensis, and the holotype specimen of Acer kenaicum. Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1994b) included seventeen leaf morphotypes from the Redoubt Point assemblage in a foliar physiognomy-based paleoclimate reconstruction and concluded that the assemblage grew in the coolest climate of any Paleogene Alaskan flora, with a mean annual temperature of 9°C (48.2°F).

Katmai National Park and Preserve

Katmai National Park and Preserve (KATM) encompasses approximately 4 million acres on the Alaska Peninsula (Figure 1). It is about 160 km (100 mi) northeast of Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve and about 240 km (150 mi) southwest of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. The park contains a multitude of paleontological resources and has rich Mesozoic marine and Paleogene terrestrial records (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Lanik, Hults and Druckenmiller2023). Fossil plants were first discovered from what is now KATM in exposures at Kukak Bay, now mapped as the Upper Oligocene Hemlock Conglomerate. This collection was made by DeAulton Saunders, a member of the June–July 1899 Harriman Expedition funded by E. H. Harriman, and was studied by the paleobotanist F. H. Knowlton (Knowlton, Reference Knowlton, Emerson, Palache, Dall, Ulrich and Knowlton1904). Continued exploration of the region has led to the discovery of dozens of other plant fossil localities inside KATM, belonging to the Hemlock Conglomerate and the Paleocene–Lower Eocene Copper Lake Formation (Magoon et al., Reference Magoon, Adkison and Egbert1976b; Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996).

Copper Lake Formation: Fossiliferous exposures of the Copper Lake Formation have been found in the northeastern area of the park near Cape Douglas and at Dumpling Mountain in the western region of the park (Blodgett et al., Reference Blodgett, Santucci and Tweet2016). The fossil flora at Cape Douglas is preserved in sandstone and siltstone layers that overly a basal conglomerate. The age of the plant-fossil–bearing horizons is interpreted as Early Eocene on the basis of its taxonomic composition (Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996, citing a written comm. from J. A. Wolfe). The plant fossils recovered from the Copper Lake Formation at Cape Douglas are leaf compressions and impressions that include three species of ferns, the gymnosperm Sequoia langsdorfii, and six species of angiosperms. Taxa named from this flora include the fern Osmunda dubiosa and the angiosperms Myrica banksiaefolia var. curta, Crataegus alaskensis, and Acer douglasense (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987; Figure 4).

The assemblage of fossil leaves and wood recovered at Dumpling Mountain is also interpreted to date from the Late Paleocene or Early Eocene, and its minimum age is constrained to the Late Eocene based on an intruding diorite dike dated to 39.63 ± 0.17 Ma (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Fiorillo, Jacobs, Currano and Wheeler2010). Twelve distinct leaf morphotypes were identified from 45 collected specimens and include several species – such as Cercidiphyllum genetrix, Glyptostrobus europaeus, and Platanus raynoldsii – that were widespread in Alaska and the western USA during the Paleogene (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Fiorillo, Jacobs, Currano and Wheeler2010). Notably, none of the morphotypes described from Dumpling Mountain represent species identified from the Cape Douglas localities that occur about 160 km (100 mi) to the east, raising the intriguing possibility that the two assemblages represent compositionally distinct but contemporaneous ecological communities. The fossil wood specimens discovered at Dumpling Mountain are well preserved and belong to four species of conifers, including a new species of Pinus Section Parrya, and the platanaceous wood genus Platanoxylon (Parrish et al., Reference Parrish, Fiorillo, Jacobs, Currano and Wheeler2010).

Hemlock Conglomerate: Fossil plants from the Hemlock Conglomerate have been collected from several localities along the southeastern coast of KATM, including the historical Kukak Bay locality (Knowlton, Reference Knowlton, Emerson, Palache, Dall, Ulrich and Knowlton1904) and a reference section of the Hemlock Conglomerate measured at Cape Nukshak (Keller and Reiser, Reference Keller and Reiser1959). These collections include leaves of ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, as well as conifer and angiosperm reproductive structures (Knowlton, Reference Knowlton, Emerson, Palache, Dall, Ulrich and Knowlton1904; Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987). Common taxa include the gymnosperms Picea, Pinus, Sequoia, and Taxodium and the angiosperms Acer, Aesculus, Corylus, and Alnus (Figure 4). The collections also include holotypes of 12 taxa (Supplementary Table 7).

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve (ANIA), located on the Alaskan Peninsula, was established to preserve Aniakchak Caldera and its surrounding lands (Figure 1). The park contains 600,000 acres and is rich in paleontological resources from the Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Paleogene (Kenworthy and Santucci, Reference Kenworthy and Santucci2003). The Paleogene resources include plant fossils of the Tolstoi and Meshik formations (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980).

Tolstoi Formation: The Tolstoi Formation crops out widely on the Alaska Peninsula, and the age of its strata ranges from Early Paleocene to Middle Eocene (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980; Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996). At its type section near Pavlof Bay, about 240 km (150 mi) southwest of ANIA, the Tolstoi Formation represents a warm to subtropical shallow marine environment and contains marine mollusks and dinoflagellates indicative of a Middle Eocene age (Marincovich, Reference Marincovich, Filewicz and Squires1988; Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996). At its reference section near Ivanof Bay, about 135 km (85 mi) southwest of ANIA, and in exposures to the northeast (including those in the park), the Tolstoi Formation represents fluvial floodplain and delta sequences and contains a diverse flora indicative of a Paleocene–Eocene age and a warm, wet environment (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1981; Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996). The plant fossil localities of the Tolstoi Formation within ANIA occur throughout the formation’s stratigraphic range and are widely spaced, from the southeastern boundary near Elephant Head Point to the northeastern boundary, where the park borders the Alaskan Peninsula National Wildlife Refuge along Pumice and Painter creeks (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980; Kenworthy and Santucci, Reference Kenworthy and Santucci2003).

In the northeastern area of the park, plant macrofossil localities occur near Painter and Pumice creeks. Sample P-23 was collected by W. R. Smith in 1922 from a mountain southwest of Pumice Creek and yielded the lectotype of the fern Dryopteris meyeri, the holotype specimen of Acer disputabilis (Figure 4), and other angiosperm leaves assigned to Ulmus braunii, Populus arctica, and Zizyphus hyperboreus (Hollick, Reference Hollick1936). The USGS paleobotanical localities 11577–11580 were discovered in several intervals of a stratigraphic section near Painter Creek and yielded an assemblage including a tree fern, Cyathea inequalateralis; a conifer, M. occidentalis; and the angiosperms Pterocarya nigelloides, Viburnum variabilis, and undetermined species of Acer and Platycarya (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980). Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1980) suggested that these localities are Early to Middle Eocene in age and represent the youngest strata of the Tolstoi Formation. Two more localities are present in the central region of the park near Jaw Mountain. Sample P-25 was collected by W. R. Smith in 1922 and includes leaf fossils of the angiosperm family Rhamnaceae (Z. hyperboreus and Paliurus colombi) and a fossil flower of an extinct species of Hydrangea (Hydrangea alaskana). Locality USGS 11632 was established near a peak 4.0 km (2.5 mi) south of Jaw Mountain and yielded a leaf belonging to a member of the Menispermaceae (Cocculus flabella) and needles of the conifers Metasequoia and Glyptostrobus. This assemblage is characteristic of the lower Tolstoi deposits and interpreted to be late Paleocene in age (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980). Exposures of the Tolstoi Formation near Elephant Head Point on Cape Kumlik in the southeastern region of ANIA produced a small collection of plant fossils, which includes undetermined species of Alnus and Vitis (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1980).

Meshik Formation: The Meshik Formation or Meshik Volcanics is a volcanic unit that contains intervals of volcaniclastic sedimentary rock (Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Miller, Yount and Wilson1981). One such interval, comprising sandstone and water-deposited tuff, is the source of USGS paleobotany locality 11640. These beds, exposed near Aniakchak Crater in the western region of Aniakchak National Monument, have yielded a diverse, angiosperm-rich flora including Metasequoia, Cercidiphyllum, Quercus, Pterocarya, Ulmus, Cornus, various Rosaceae, and the holotype specimen of an extinct species of maple, Acer dettermanii (USNM 396014) (Wolfe and Tanai, Reference Wolfe and Tanai1987; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe, Boulter and Fisher1994a). Wolfe (Reference Wolfe1980) interpreted this assemblage as Middle Eocene in age, an estimate that falls in the early part of the age range suggested by K-Ar dates of the tuff (43.1 ± 1.3 to 24.9 ± 0.49 Ma; Detterman et al., Reference Detterman, Case, Miller, Wilson and Yount1996). Wolfe (Reference Wolfe, Boulter and Fisher1994a) used 34 leaf morphotypes from this site to estimate its paleoclimate based on leaf physiognomy and characterized the assemblage as a notophyllous broad-leaved evergreen forest with a mean annual temperature of 13.7°C (56.7°F). Detterman et al. (Reference Detterman, Miller, Yount and Wilson1981) also reported well-preserved petrified logs, some occurring in original growth position, in exposures of the Meshik Formation on the south shore of Kujulik Bay just south of the southern park boundary.

Kenai Fjords National Park

Kenai Fjords National Park (KEFJ) is located on the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska, preserves about 600,000 acres, and includes the 780 km2 (300 mi2) Harding Ice Field, one of four ice caps in North America (Figure 1). Potentially in situ logs and woody debris were discovered near Exit Glacier, about 20 km (12 mi) northwest of Seward, Alaska. Initial radiocarbon dating of the woody material from KEFJ indicates an age of 900 years, suggesting that it may represent a forest community buried by an advancing glacier (Kenworthy and Santucci, Reference Kenworthy and Santucci2003).

3.1.4 Southeast Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve (GLBA), located in the northeastern part of southeastern Alaska, preserves about 3.3 million acres of land rich in floral and faunal biodiversity and is home to globally recognized tidewater glaciers (Figure 1). Although the area of the park is extensively glaciated, plant macrofossils have been discovered from outcrops of the Oligocene Cenotaph Formation and Miocene–Pleistocene Yakataga Formation on Cenotaph Island, and abundant subfossil Holocene wood has been discovered from Muir Inlet (Figure 3).

Cenotaph Formation: The Cenotaph Formation is an Oligocene volcanic unit interbedded with marine and terrestrial sedimentary rocks that crops out in the Lituya Bay Region, including on Cenotaph Island and on the mainland south of the bay. The plant fossil locality 75-Apr-37 occurs in horizons of the type section of the Cenotaph Formation on Cenotaph Island and has produced angiosperm leaves attributed to Macclintockia pugetensis, Magnolia reticulata, and undetermined species of Pterocarya and the Lauraceae (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1976). M. pugetensis, an extinct species of uncertain familial affinity, is restricted to the Kummerian (Oligocene) floral stage in Alaska, and therefore provides strong biostratigraphic correlation with other plant-fossil–bearing units from the Gulf of Alaska (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1977). Plafker (Reference Plafker1967) included the Cenotaph Formation within the Topsy Formation, which consists of Middle Oligocene–Upper Miocene shallow marine deposits that are conformably overlain by the Yakataga Formation.

Yakataga Formation: Within GLBA, the Yakataga Formation is exposed along the coast between Lituya Bay and Icy Point, on Cenotaph Island in Lituya Bay, and north and south of Fairweather Glacier (Santucci and Kenworthy, Reference Santucci and Kenworthy2008). Exposures on the south shore of Cenotaph Island (USGS paleobotany locality 11186) produced a single leaf fossil assigned to Fagus (beech) and are the only source of paleobotanical material from the Yakataga Formation within GLBA. Elsewhere within and beyond the boundaries of GLBA, the Yakataga Formation is known as a marine unit and has produced fossils of foraminifera, bivalves, and gastropods that suggest a Middle Miocene–Pleistocene age (MacNeil et al., Reference MacNeil, Wolfe, Miller and Hopkins1961; Santucci and Kenworthy, Reference Santucci and Kenworthy2008).

Muir Inlet: An early reference to the sub-fossil wood and standing stumps present in what is now called Muir Inlet was made by the naturalist John Muir in the book Travels in Alaska (Reference Muir1915). Tree-ring cores and radiocarbon age estimates from these trees have been compiled with records from living trees in GLBA to reconstruct forest succession and paleoclimate in the region over about the past 10,000 years (Lawson et al., Reference Lawson, Wiles and Finnegan2007; Lawson and Wiles, Reference Lawson and Wiles2009).

Park Collections: The park collections include three pieces of basal peat deposits and two pieces of petrified wood. The peat was collected from a terrace above Echo Creek north of Lituya Bay and dated to 40,000 ybp. Wood specimens were collected by C. V. Janda from the west side of Adams Valley and from the beach at Dundas Bay and identified as belonging to a conifer and an angiosperm, respectively (Santucci and Kenworthy, Reference Santucci and Kenworthy2008).

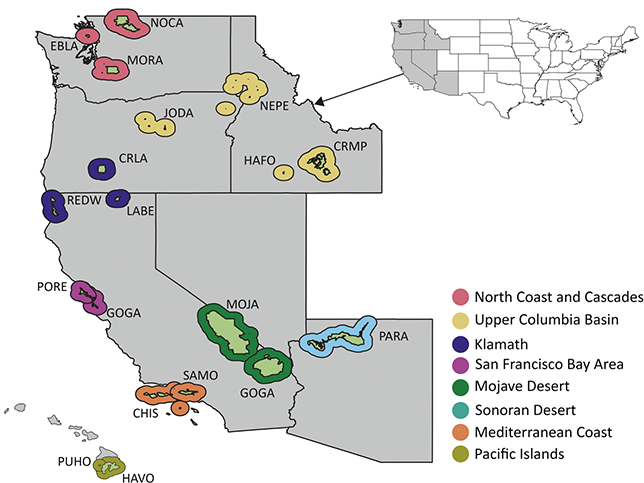

3.2 Pacific West Region

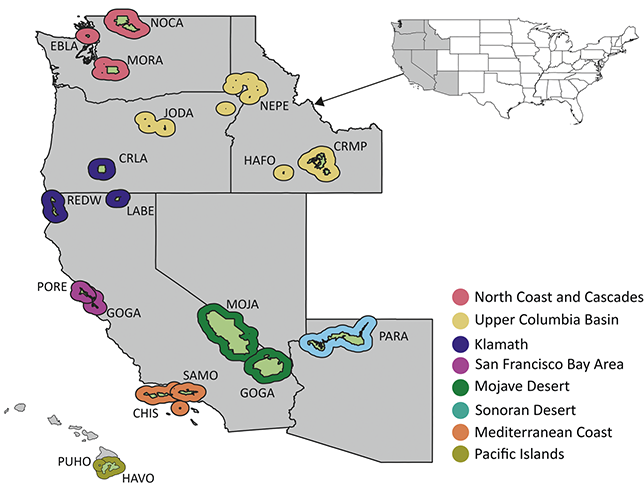

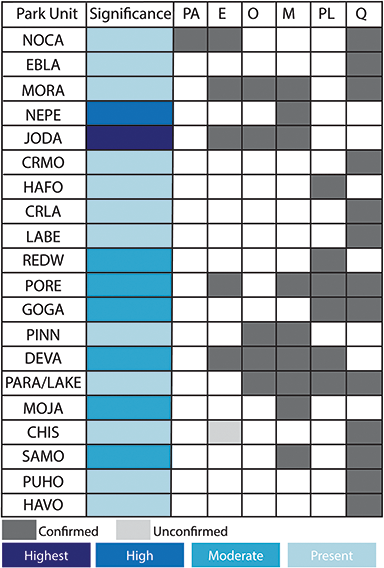

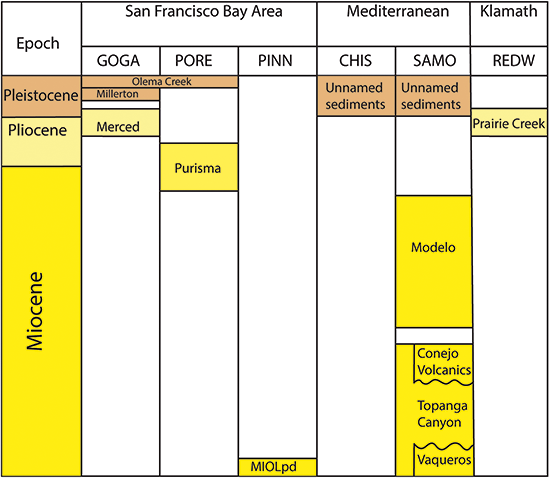

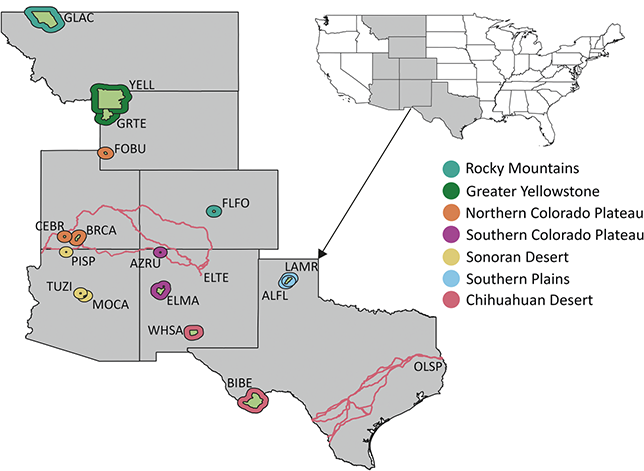

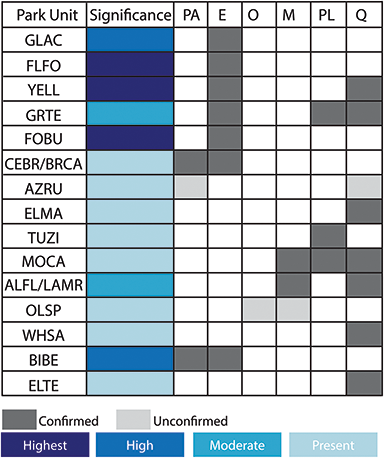

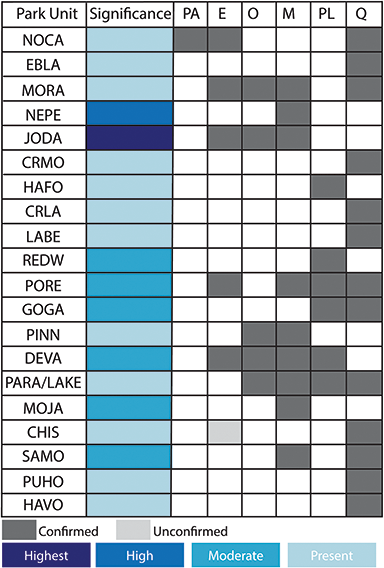

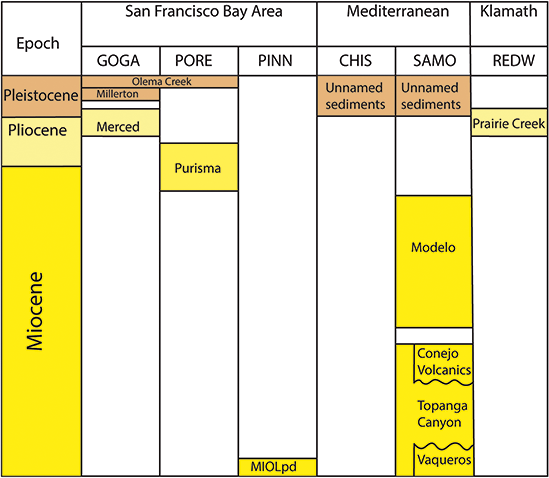

The Pacific West Region includes 64 NPS units in the states and territories of American Samoa, California, Guam, Hawai’i, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. The parks of this region are clustered in seven inventory and monitoring networks (Figure 5): the Klamath Network (KLMN), the Mediterranean Coast Network (MEDN), the Mojave Desert Network, the North Columbia and Cascades Network, the Pacific Islands Network, the San Francisco Bay Area Network (SFAN), and the Upper Columbia Basin Network. More than 25 geologic formations spanning the Paleocene to Holocene from 20 park units in the Pacific West Region have confirmed paleobotanical resources.

Figure 5 Map of NPS units with Cenozoic paleobotanical resources in the Pacific West Region, colored by inventory and monitoring network. See Figure 1 legend for details on the park symbology and acronyms.

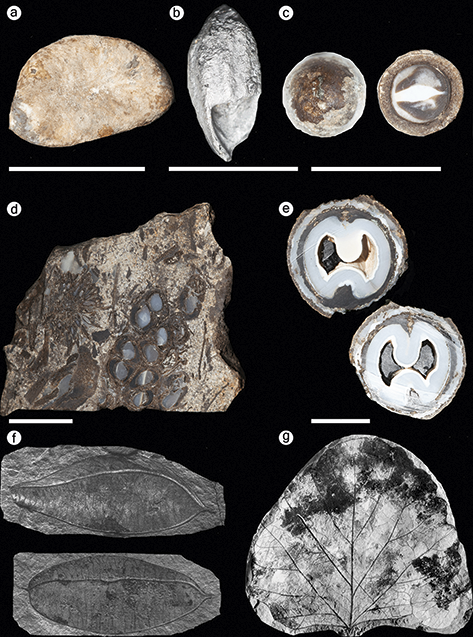

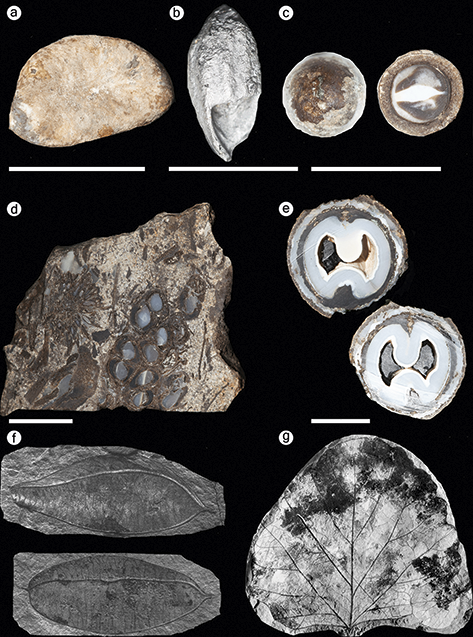

Significant resources from the Pacific West Region include classic paleobotanical localities such as the Eocene Clarno Nut Beds in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument and the Miocene Whitebird site of Nez Perce National Historical Park, as well as a number of lesser-known Plio–Pleistocene sites in the KLMN, MEDN, and SFAN networks of coastal California (Figure 6). The anatomically preserved fruits and seeds of the Clarno Nut Beds represent a phase in the vegetational history of the Pacific Northwest when the flora included a mixture of plants with familial affinities to groups mainly known from tropical and subtropical areas today (e.g., Icacinaceae, Menispermaceae) as well as to lineages characteristic of temperate North American forests (e.g., Platanaceae). The insight into the Eocene vegetational history of the Pacific West provided by the Clarno Nut Beds is complemented by assemblages preserved outside of NPS units, such as the floras of the Puget Group (Burnham, Reference Burnham1994) and Chuckanut Formation (Mustoe and Gannaway, Reference Mustoe and Gannaway1997) in Washington state and the Goshen and Comstock floras of Oregon (see Wing, Reference Wing, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998; Graham, Reference Graham1999; and DeVore and Pigg, Reference DeVore and Pigg2010 for reviews of Eocene Pacific Northwest floras).

Figure 6 Summary of the temporal distribution and significance of Cenozoic paleobotanical resources in the Pacific West Region. See Figure 2 legend for explanation of significance ratings.

The Miocene Whitebird site, deposited ca. 30 million years later in western Idaho, includes a greater proportion of broadleaf deciduous angiosperms and conifers characteristic of the extant North American flora, though not necessarily of the Pacific Northwest. Miocene floras from the Columbia Plateau occurring outside of NPS areas are well-documented (Chaney and Axelrod, Reference Chaney and Axelrod1959; Graham, Reference Graham and Graham1965), and recent work has placed them into a stratigraphic context to illustrate changes in floral composition during the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (Lowe, Reference Lowe2024).

Fossil plants from the Plio–Pleistocene are preserved in Redwood National Park, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Point Reyes National Recreation Area, Channel Islands National Park, and Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. These assemblages mainly include genera and species that still occur along the California coast today and have been used to trace the evolutionary history of regional vegetation types such as the California closed-cone pine forest (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod and Philbrick1967).

3.2.1 North Coast and Cascades Inventory and Monitoring Network

Northern Cascades National Park Service Complex

The Northern Cascades National Park Service Complex (NOCA) is situated in the state of Washington (Figure 5) and was established to facilitate recreational enjoyment of the North Cascade Mountains and associated glaciers, watercourses, and ecosystems. Cenozoic paleobotanical resources are preserved in NOCA in three contexts: lower Cenozoic sandstones, Quaternary lake sediments, and Quaternary mass wasting deposits.

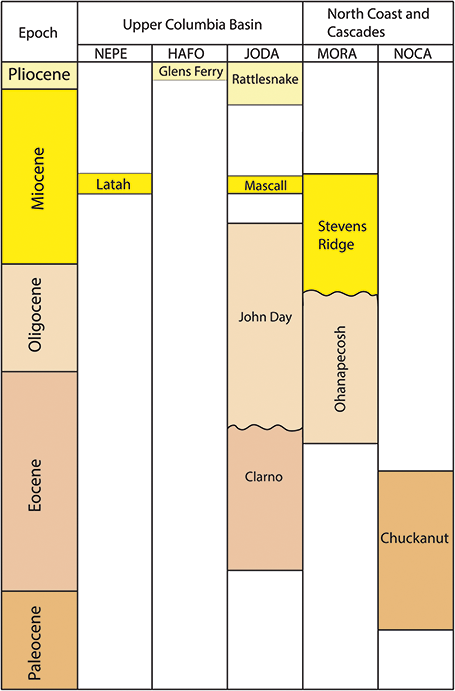

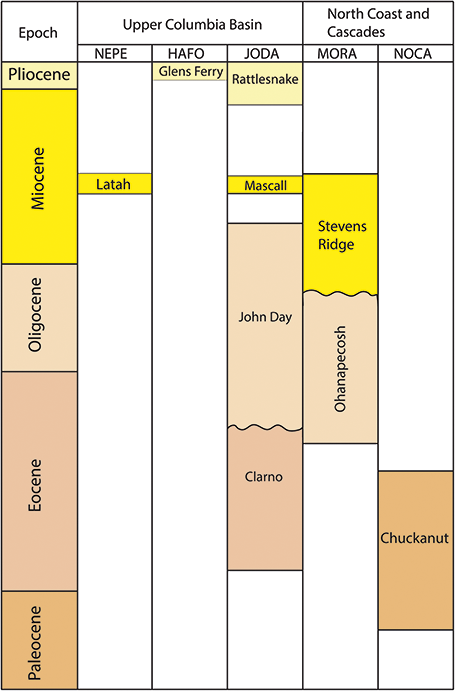

Chuckanut Formation/Tertiary Sandstones: Sediments of the Chuckanut Formation were deposited in a coastal plain during the Paleocene and Eocene and are well-exposed throughout northwestern Washington and southwestern British Colombia (Figure 7; Mustoe et al., Reference Mustoe, Dillhoff and Dillhoff2007; Fay et al., Reference Fay, Kenworthy and Santucci2009). Within NOCA, non-diagnostic plant fragments and a fossil log have been found in strata that are variously included within the Chuckanut Formation (Staatz et al., Reference Staatz, Tabor and Weis1972) or within an informal sedimentary unit comprised of sandstones and conglomerates (Tabor et al., Reference Tabor, Haugerud, Hildreth and Brown2003). Outside of NOCA, in Chuckanut outcrops near Bellingham, Washington, the formation has produced abundant plant fossils, including palm leaves and foliage of tree ferns, gymnosperms, and woody angiosperms (Mustoe and Gannaway, Reference Mustoe and Gannaway1995; Mustoe et al., Reference Mustoe, Dillhoff and Dillhoff2007; Mustoe, Reference Mustoe2019). These fossil assemblages are preserved in three different members of the Chuckanut Formation and the stratigraphic succession of plant communities they represent is interpreted to reflect a local transition from a warmer and wetter climate to a dryer and cooler climate, potentially related to the climatic deterioration of the EOT or episodes of local mountain-building (Mustoe and Gannaway, Reference Mustoe and Gannaway1997). Well-preserved plant fossils come from fine-grained portions of the Chuckanut Formation, and if such strata are present within NOCA, they are likely stratigraphically close to the fossiliferous sandstone.

Figure 7 Stratigraphic chart of Tertiary plant-fossil–bearing formations in the Upper Columbia Basin and Northern Coast and Cascades Inventory and Monitoring Networks.

Quaternary sediments: Plant macrofossils, pollen, and charcoal have been recovered from Ridley and Thunder lakes and Skagit Valley, all located in the northeastern corner of the park. The cores from Ridley and Thunder lakes preserve a paleoenvironmental record of the past 14,000 years, and their floras include many plants that inhabit the region today such as Abies, Chamaecyparis, Picea, Pinus, Tsuga, Alnus, Betula, and Fraxinus (Spooner et al., Reference Spooner, Brubaker and Foit2008; Fay et al., Reference Fay, Kenworthy and Santucci2009). The macrofossils from Skagit Valley document vegetational changes between 24,000 and 17,110 radiocarbon ybp (Riedel, Reference Riedel2007; Fay et al., Reference Fay, Kenworthy and Santucci2009). Older sediments of this interval are dominated by conifer foliage of Pinus albicaulis, Picea engelmannii, and Abies lasiocarpa, and leaves of Salix and fragments of Selaginella become more abundant in the younger sediments. Finally, trees buried in growth position are preserved in ca. 7,000-year-old lake deposits that formed after a landslide dammed the Upper Skagit River (Riedel et al., Reference Riedel, Pringle and Schuster2001).

Ebey’s Landing National Historical Reserve

Ebey’s Landing National Historical Reserve (EBLA), located on Whidbey Island of the San Juan Archipelago in Washington state, encompasses about 20,000 acres and includes two state parks and the historic town of Coupeville (Figure 5). The surficial geology of EBLA is dominated by unconsolidated Quaternary sediments that were deposited by glacial and fluvial processes (Fay et al., Reference Fay, Kenworthy and Santucci2009). The paleobotanical material preserved in these sediments is limited to a few minor occurrences. Sediments accumulated during the Olympia nonglacial interval (ca. 60,000–20,000 ybp) preserve pollen, pinecones, branches, leaf prints, and in situ tree roots (Troost, Reference Troost2002); wood found in an estuary, possibly of Douglas fir, was radiocarbon dated to 1740–1790 or 1810–1960 CE (Polenz et al., Reference Polenz, Slaughter, Dragovich and Thorsen2005a, Reference Polenz, Slaughter and Thorsen2005b).

Mount Rainier National Park

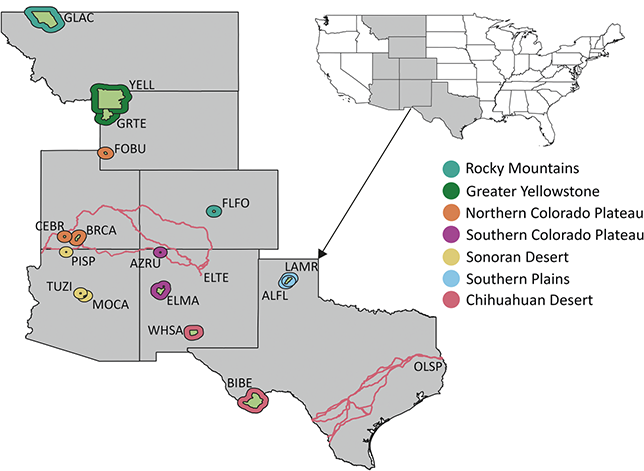

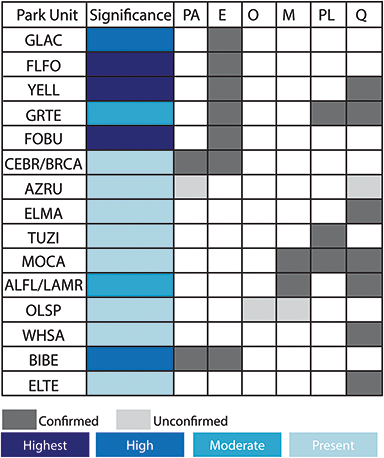

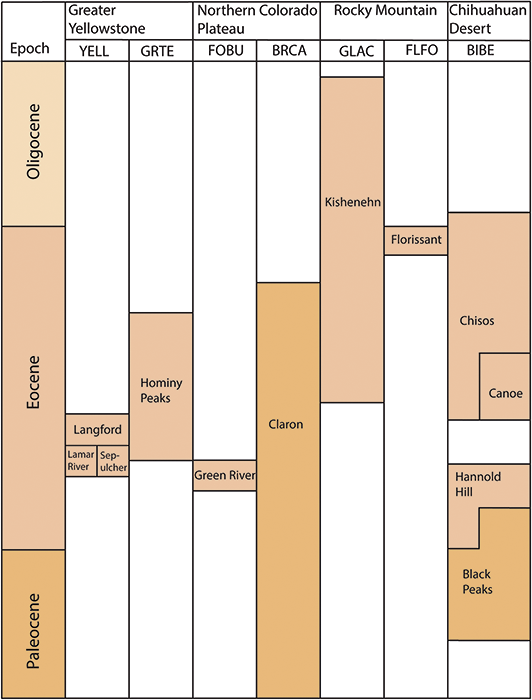

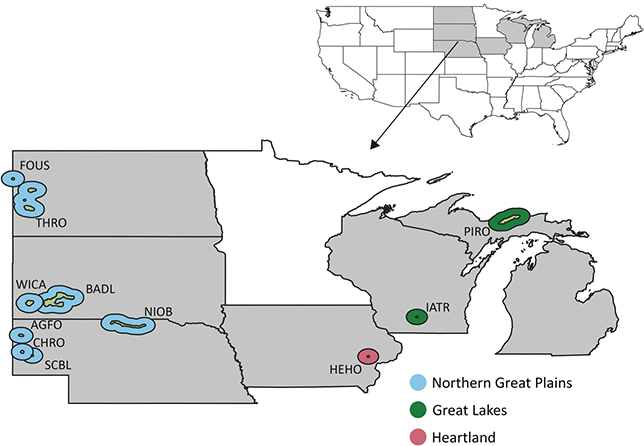

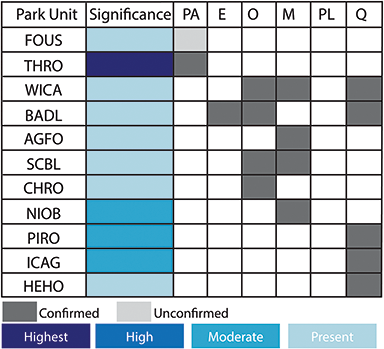

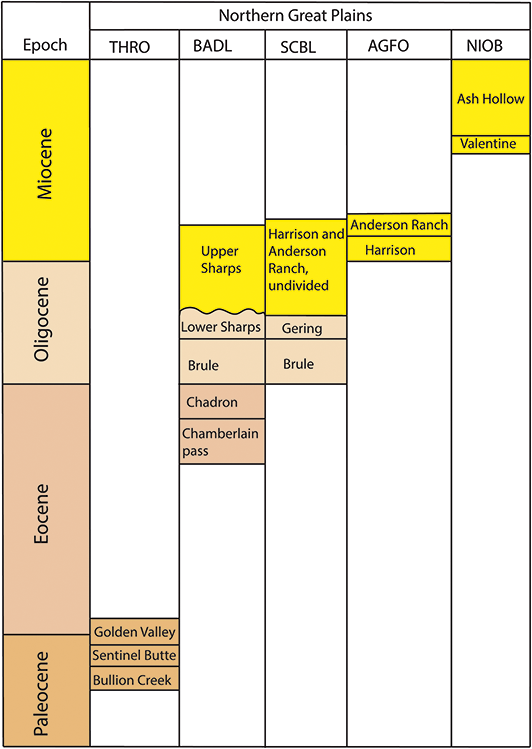

Mount Rainier National Park (MORA) preserves approximately 235,000 acres of land surrounding the peak of Mount Rainier or Tahoma, in the central portion of the Cascade Range of southwestern Washington (Figure 5). The park contains paleobotanical resources in volcaniclastic strata of the Ohanapecosh and Stevens Ridge formations deposited between the Eocene and Miocene and in Holocene lake sediments and mass-wasting deposits.