Introduction

Visual impairment poses a significant global economic burden, with the annual loss of productivity estimated to be approximately US$411 billion worldwide in purchasing power parity. This figure far surpasses the cost shortfall of addressing the associated unmet needs, estimated at around US$25 billion (WHO, 2019). Cataracts represent a leading cause of visual impairment, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where they constitute the primary source of reversible blindness. Data from Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) and the National Population Council (CONAPO) indicate that approximately 39% of individuals between 50 and 80 years of age may develop some form of cataract (Cruz González, Reference Cruz González2017). Surgery, particularly techniques like phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation, remains the sole proven treatment. Patient selection for cataract surgery typically considers not only visual acuity but also an assessment of their visual function and quality of life (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Fraser and Gray2007). Research has demonstrated that cataract surgery not only enhances the former but also yields significant benefits for the latter (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Karimova, Hildreth, Crabtree, Allen and O’connell2006).

Limited resources in the Mexican public healthcare sector present significant challenges, as demonstrated by Contreras-Loya et al. (Reference Contreras-Loya, Gómez-Dantés, Puentes, Garrido-Latorre, Castro-Tinoco and Fajardo-Dolci2015), who assessed waiting times in public hospitals for seven surgical procedures, including cataracts. They revealed an average waiting time of 14 weeks for surgeries, in addition to 11 weeks for diagnostic procedures. These delays have critical implications for patient well-being. Addressing these deficiencies requires increased human and physical resources. According to economic theories of the third sector, nonprofit organizations can serve as vital supplements or complements to address societal needs (Young, Reference Young2000, Reference Young, Boris and Steuerle2006). They can fill gaps in the quality and quantity of public goods provision (Kingma, Reference Kingma1997; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod and Phelps1975), expand service offerings (Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman1996, Reference Rose-Ackerman1997), promote training and research (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Mattingly and Ludden1997), or provide alternative solutions to market failures, such as challenges in monitoring public or private for-profit providers through contractual arrangements due to information asymmetry (Hansmann, Reference Hansmann1980, Reference Hansmann and Fuchs1994).

IMO, located in Querétaro, central Mexico, is a nonprofit healthcare institution. Established in 1997, its primary mission is to provide comprehensive diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of eye diseases for the low-income population. It boasts a multidisciplinary team of professionals, including ophthalmologists, anesthesiologists, internists, optometrists, assistants, nurses, and administrative staff, all dedicated to improving patients’ eyesight and overall quality of life. IMO offers a wide range of ophthalmological services, to cover all the pathology for sight threatening diseases. It is equipped with state-of-the-art diagnostic facilities, an optical department, a pharmacy, clinical laboratories, pathology services, and internal medicine and anesthesiology departments specialized in restoring sight. Furthermore, IMO serves as a hub for education and research.

When the public sector’s response is inadequate and requires assistance from the private sector, understanding the costs and benefits of nonprofit organizations’ activities becomes essential for several reasons. First, it can help them demonstrate accountability to stakeholders (OECD, 2003). Second, identifying actions that yield the most significant benefits and those that are costlier can enable nonprofits to optimize resource allocation and enhance decision-making processes, strengthening organizational efficiency and increasing their chances of receiving grants from funding organizations (Hwang & Powell, Reference Hwang and Powell2009). Third, comprehending costs and benefits can help nonprofits compare their performance to industry standards, facilitating the identification of best practices and opportunities for improvement (LeRoux & Wright, Reference LeRoux and Wright2010; Poister, Reference Poister2003). Moreover, measuring and communicating costs and benefits are crucial for knowledge creation, as they generate valuable insights into the social value and effectiveness of nonprofit organizations. This knowledge informs decision-making, improving service delivery, enhancing accountability, and promoting transparency (Lettieri et al., Reference Lettieri, Borga and Savoldelli2004; Nonaka & Takeuchi, Reference Nonaka and Takeuchi1995).

Considering the above, this study employs the Social Return on Investment (SROI) approach to evaluate the costs and benefits of cataract surgery at IMO. SROI is a well-established principle-based framework that aims to capture a wide range of non-financial outcomes and values, including social well-being, environmental sustainability, and community developmentFootnote 1 (Nicholls et al., Reference Nicholls, Lawlor, Neitzer and Goodspeed2012). It is often used by organizations to understand and communicate their social and environmental impact beyond traditional financial measures. SROI has been extensively applied across various topics and contexts, including tourism (Ariza-Montes et al., Reference Ariza-Montes, Sianes, Fernández-Rodríguez, López-Martín, Ruíz-Lozano and Tirado-Valencia2021); visual arts programs in residential care homes (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Windle and Edwards2020b); sport and physical activity in community facilities (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Taylor, Ramchandani and Christy2020); rail services renovation plans (Venezia & Pizzutilo, Reference Venezia and Pizzutilo2020); social entrepreneurship (Cordes, Reference Cordes2017; Valdés Medina, Reference Valdés Medina2019); recruitment, training and management of volunteers (Manetti et al., Reference Manetti, Bellucci, Como and Bagnoli2015); and even the World Bank’s performance in delivering aid to the least developed countries (Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2017).

There are also numerous examples of SROI analysis within the context of health-related issues. For instance, Merino et al. (Reference Merino, Ivanova, Lorenzo and Hidalgo-Vega2022) estimated the value created by a series of proposals to improve the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Spain. Drabo et al. (Reference Drabo, Eckel, Ross, Brozic, Carlton, Warren, Kleb, Laird, Porter and Pollack2021) conducted an assessment of an affordable housing program designed to address the social and environmental determinants of community health in Baltimore, Maryland. Jones et al., (Reference Jones, Hartfiel, Brocklehurst, Lynch and Edwards2020a, Reference Jones, Windle and Edwards2020b) conducted an evaluation of a community hub for people with chronic conditions in North Wales. Banke-Thomas et al. (Reference Banke-Thomas, Madaj and Van Den Broek2019) assessed the results of emergency obstetric care training aimed at reducing maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in Kenya. Fanselow and Hellesoe (Reference Fanselow and Hellesoe2019) analyzed the effects of a state-funded service designed to prevent mental health illnesses among 10–13-year-olds in New Zealand. Willis et al. (Reference Willis, Semple and de Waal2018) evaluated the outcomes of dementia peer-support groups in South London, the UK. Clifford et al. (Reference Clifford, Jones, Solomon-Moore, Kok and Kimberlee2017) assessed the results of a community-based diabetes prevention and management education program in the UK. Additionally, the Report Database of the Social Value Network UK comprises more than 100 reports related to health and well-being, including those by Wistreich (Reference Wistreich2022), who forecasted the SROI for the services provided by the charity Crann to people with neuro-physical disabilities in Ireland; or Philipson et al. (Reference Philipson, Thornton Snider, Chit, Green, Hosbach, Tinkham Schwartz, Wu and Aubry2017), who quantified the health effects of routine vaccination for 14 diseases in the USA.

Despite all these examples, to our knowledge there is to date no study that assesses the social return on investment of cataract surgery services provided by nonprofit organizations. Thus, in addition to contributing to the existing literature by pioneering the application of SROI methodology in this context, this paper is also innovative in two other ways. First, we take a holistic approach by considering not only patients but also their caregivers as direct beneficiaries of the intervention. Second, we estimate the SROI at various levels of aggregation: individual, patient–caregiver pairs, and cumulative for all patients and caregivers. This methodological innovation enables a comprehensive exploration of the broader implications of the findings. Our primary data source consists of interviews with a sample of patients and caregivers who underwent cataract surgery in both eyes at IMO between January and November 2022. Through their investments in time and money for the procedure, patients regained autonomy and assurance to perform instrumental activities of daily living. Caregivers also benefited from increased patient autonomy and the relief that followed. The analysis of these costs and benefits reveals improvements in quality of life and autonomy for both groups of stakeholders. These results carry theoretical implications, shedding light on the potential synergy between nonprofit organizations and public policies. Nonprofits can play a pivotal role in delivering essential public goods and services, either in an independent role from the state or as complementary partners through contractual relationships, but with a cost-effective economic rationality.

The evidence presented contributes to the debate surrounding the suitability of the SROI methodology for assessing the broader value and outcomes of nonprofit organizations (Hyndman & McConville, Reference Hyndman and McConville2016; Manetti, Reference Manetti2014; Mook & Richmond, Reference Mook and Richmond2003). Like any evaluation and assessment tool, SROI has both advantages and limitations. On the positive side, it has proven effective for communication, helping legitimize nonprofits in the eyes of donors, governments, and the public. It also aids in more efficient and effective resource allocation (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schober, Simsa and Millner2015). However, the methodology has been criticized for its complexity and resource-intensive nature, as well as its reliance on various assumptions and judgments. For instance, monetization of social outcomes through financial proxies can introduce subjectivity and biases (Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Lyon, McKay and Moro2010; Manetti, Reference Manetti2014). To mitigate these concerns, we document the assumptions made, including those related to monetary valuations, timeframes, and attribution of outcomes to the intervention. We also actively engaged stakeholders, incorporating their perspectives to validate and refine our assumptions, while ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of the intervention’s impacts. Additionally, we conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings, testing different scenarios and assumptions to gauge the potential range of outcomes, further enhancing the reliability of our results.

Nonprofits exist to achieve social or environmental goals, and the SROI methodology is designed to measure their performance in this regard. It allows nonprofits to demonstrate their effectiveness to stakeholders while identifying areas for improvement. SROI also has an important role as a means of generating knowledge. Its estimation requires involving stakeholders in the identification and assessment of outcomes. The data collected through this process can yield fresh insights and guide future program designs. Thus, by embedding the SROI methodology into their practices, nonprofits can continuously learn and adapt to achieve greater positive change in society.

Theory of Change, Data and Methods

How Does Cataract Surgery Benefit People?

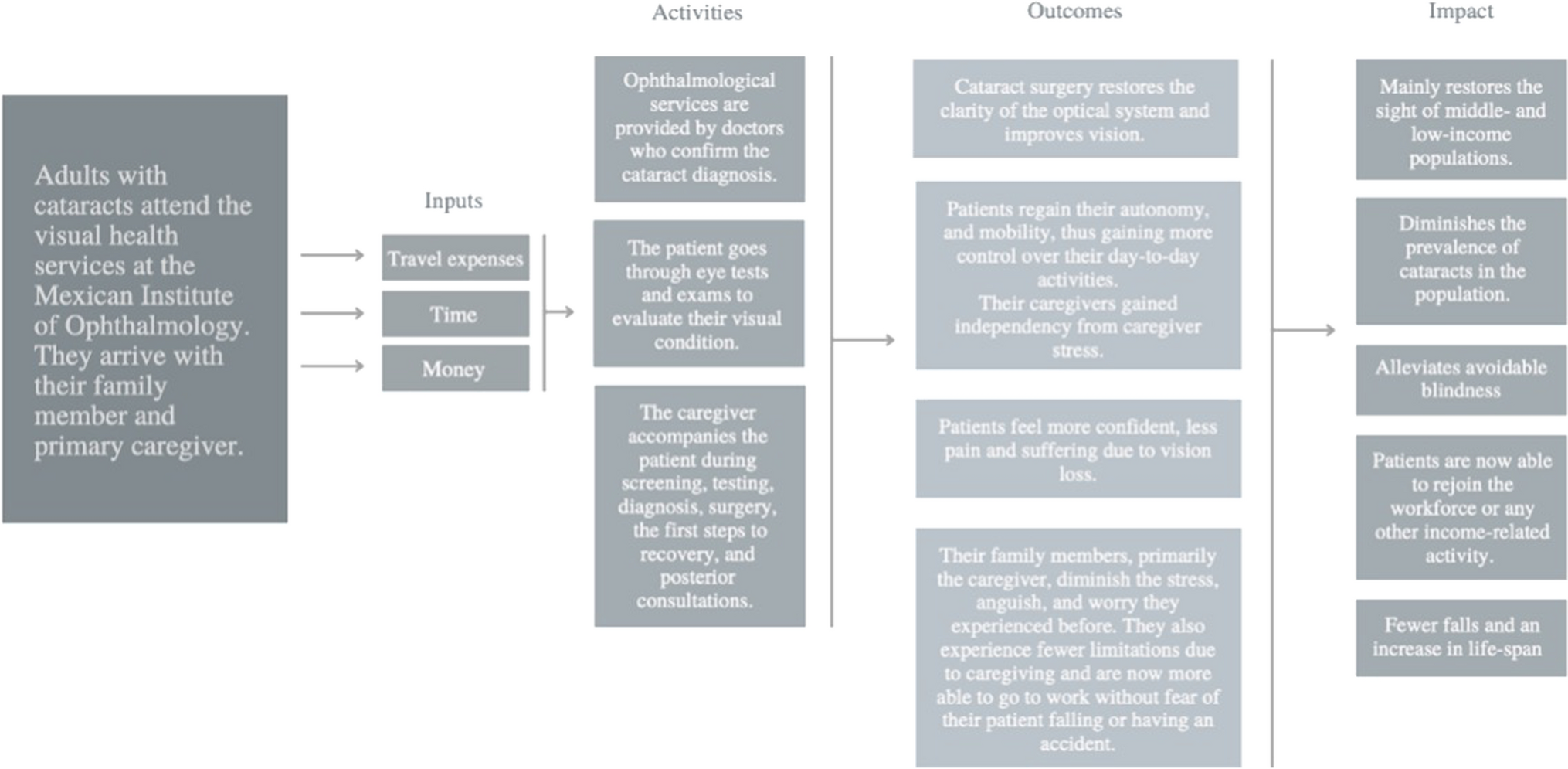

Cataract surgery has been found beneficial not only for improving vision-related quality of life (Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Bernabei, Schiavi and Giannaccare2020; To et al., Reference To, Meuleners, Bulsara, Fraser, Van Duong, Van Do, Huynh, Phi, Tran and Do Nguyen2014; Zitha & Rampersad, Reference Zitha and Rampersad2020) but also various poverty-related indicators such as the number of working household members or the rate of engagement in income-generating activities (Finger et al., Reference Finger, Kupitz, Fenwick, Balasubramaniam, Ramani and HolzGilbert2012). However, significant barriers to accessing cataract surgery exist, including the cost of the procedure, lack of patient awareness about their condition, and transportation difficulties (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Zheng, Ting, Lamoureux, Cheng and Wong2013). Moreover, since cataracts can vary in severity, progression, and impact on vision among individuals, the benefits of surgery may also vary depending on the specific case. Figure 1 outlines the theory of change for cataract surgery at IMO. These low-cost surgeries primarily benefit low-income individuals seeking ophthalmic healthcare. The main stakeholders directly affected by the intervention are the patients and their caregivers.

Fig. 1 Theory of change from cataract surgery at IMO

Data

Between January and November 2022, IMO conducted 2100 cataract surgeries, 470 of which involved 235 patients who underwent surgery on both eyes. From this subgroup, we successfully assembled a sample of 65 patients and their caregivers. Our initial inclusion criteria encompassed patients aged at least 50 years, accompanied by their caregivers during both the surgery and the recovery period. However, our sample was also constrained by factors beyond our control: limited resources at IMO for conducting surveys, necessitating telephone-based interviews; difficulties in recontacting patients and caregivers, many of whom reside in remote rural areas; and a notable frequency of refusals to participate in the study. Importantly, all respondents consented to have their interviews recorded, and we ensured their confidentiality through data anonymization.

Focusing on bilateral cataract surgery cases offers several advantages that enhance the feasibility and reliability of the SROI methodology. First, it ensures consistency, as all patients in the sample underwent the same procedure. Second, bilateral surgery often results in a more significant improvement in patients’ vision and quality of life. Furthermore, this approach minimizes potential confounding factors that could arise when comparing patients who had one-eye surgery with those who had two-eye surgery. Lastly, it aligns with the practical reality that many patients with advanced cataracts undergo bilateral surgery.

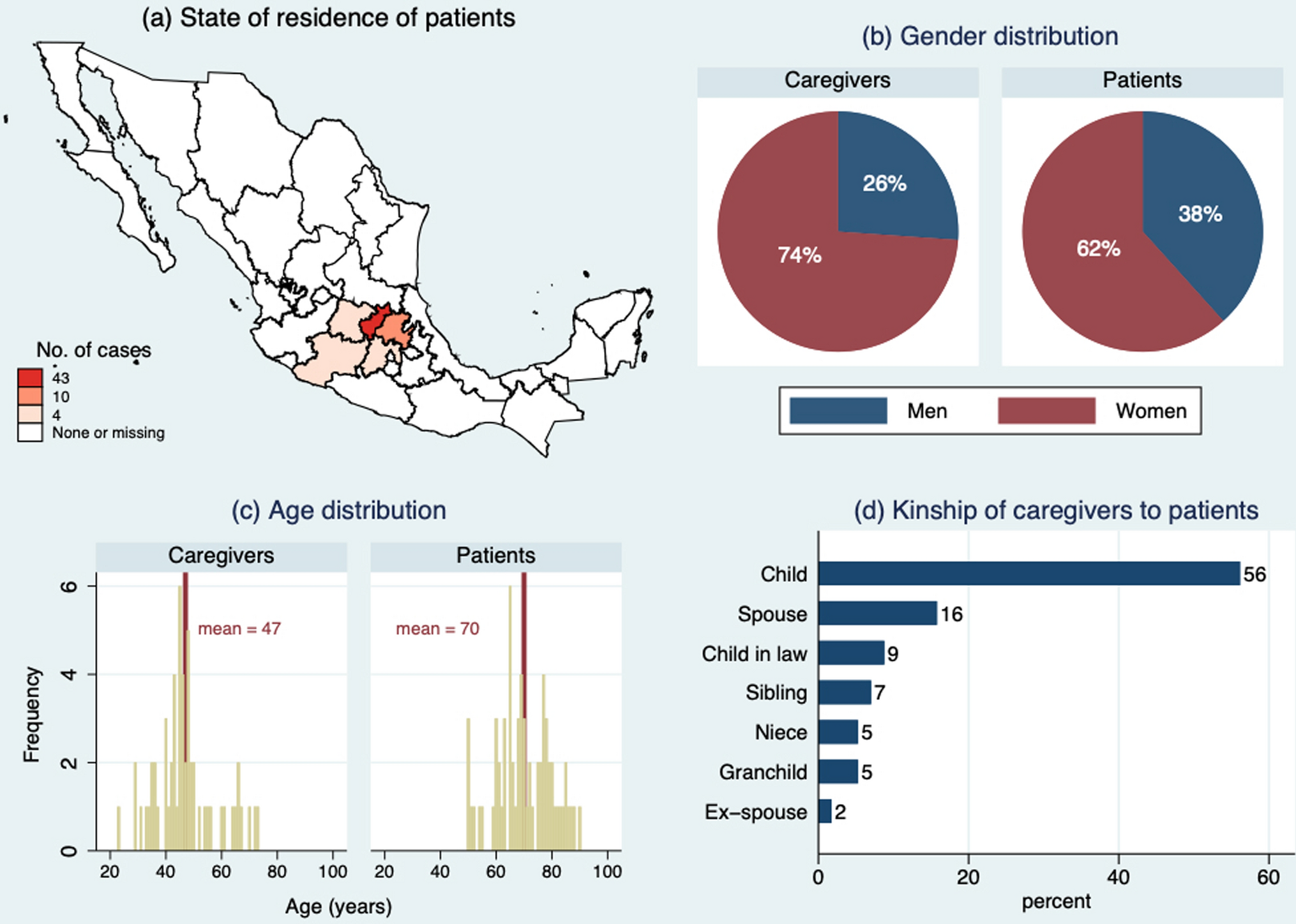

Figure 2 summarizes the individual characteristics of interviewees. Panel (a) shows that 66% of patients reside in Querétaro, 15% in Hidalgo and the remaining 19% are equally distributed among the states of Mexico, Michoacán, and Guanajuato. Panel (b) displays the gender composition, with women representing 62% of patients and 74% of caregivers. Panel (c) contains the age distributions, with mean ages of 70 for patients (range from 50 to 90) and 47 for caregivers (range from 23 to 73). Finally, panel (d) tabulates kinship frequencies, with 56% of caregivers being children of their patients, 16% spouses, 9% children in law, 7% siblings, 5% nieces, 5% grandchildren, and 2% ex-spouses.

Fig. 2 Individual characteristics of stakeholders

Inputs

The cataract surgery process begins with the patient’s initial consultation, in which ophthalmologists assess visual acuity, refraction, and pupil dilation. Subsequent consultations are scheduled to confirm the diagnosis and determine if the patient is a surgical candidate. Pre-surgery studies and clinical analyses are also conducted. After the first-eye surgery, there are three follow-up appointments. The same process is repeated for the second-eye surgery, with some analyses being optional if performed within 30 days of the first-eye surgery. Both patients and caregivers contribute time and money to the intervention, estimated as follows:

• Time We first calculated the total hours incurred on the intervention. Patients spent 21 h on consultations, examinations, and the first-eye surgery. For the second eye, the time was also calculated at 21 h if more than a year had passed since the first-eye surgery, or 16.5 h otherwise. Additionally, we considered a total recovery period of 7 days. Caregivers are required to accompany patients at all times, so they dedicated the same number of hours to consultations, examinations, and surgeries. We also factored in one full day of care during the recovery period. To value the stakeholders’ time, we used the 2022 general minimum wage of 172.87 Mexican pesos per day (approximately 8.6 US dollars), as set by the National Minimum Wage Commission (CONASAMI, 2021). This wage serves as a proxy for the opportunity cost of time, representing the baseline income forgone by stakeholders while engaged in the intervention.

• Pecuniary costs In addition to the cost of consultations, medical examinations, and surgical procedures, stakeholders may incur in transportation, food, and lodging expenses when they undergo cataract surgery.Footnote 2 To estimate the travel expenses, we used a previous mobility study from a sample of patients that used IMO’s ophthalmological services on a monthly basis. This data allowed us to estimate transportation and lodging costs for each patient and caregiver individually, taking into account their places of residence and a total of 7 visits for the complete two-eye intervention. Food expenses were estimated based on the cost of two meals per person per visit in the IMO facilities.

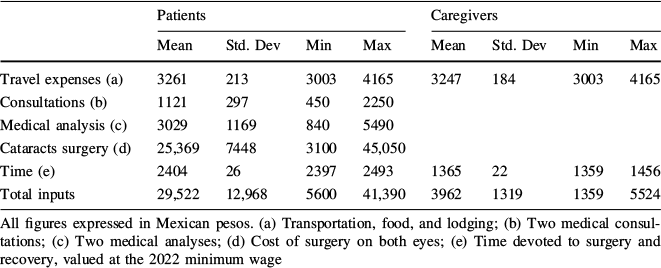

Table 1 reports the summary statistics for the inputs from stakeholders. On average, a patient–caregiver pair invests 33,484 pesos (about 1664 dollars) in bilateral cataract surgery at IMO. In the absence of more detailed information about the allocation of expenses among stakeholders, we assumed that patients cover the costs of consultations, medical examinations and surgeries, as they are the primary beneficiaries of the intervention. Under this assumption, patients cover, on average, 88% of the costs.

Table 1 Summary statistics of inputs by stakeholders

Patients |

Caregivers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean |

Std. Dev |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Std. Dev |

Min |

Max |

|

Travel expenses (a) |

3261 |

213 |

3003 |

4165 |

3247 |

184 |

3003 |

4165 |

Consultations (b) |

1121 |

297 |

450 |

2250 |

||||

Medical analysis (c) |

3029 |

1169 |

840 |

5490 |

||||

Cataracts surgery (d) |

25,369 |

7448 |

3100 |

45,050 |

||||

Time (e) |

2404 |

26 |

2397 |

2493 |

1365 |

22 |

1359 |

1456 |

Total inputs |

29,522 |

12,968 |

5600 |

41,390 |

3962 |

1319 |

1359 |

5524 |

All figures expressed in Mexican pesos. (a) Transportation, food, and lodging; (b) Two medical consultations; (c) Two medical analyses; (d) Cost of surgery on both eyes; (e) Time devoted to surgery and recovery, valued at the 2022 minimum wage

Outcomes

Open-ended questions and interviews gathered stories of change from patients and caregivers.Footnote 3 Each testimony highlighted and documented all reported effects, including changes in attitudes, capacities, behaviors, and feelings. We identified the frequency of specific phrases and words, sorting them by relevance in accordance with the principle of materiality. Outcomes were delineated through a chain of events, considering stakeholder statements and creating a path from their prior conditions to what they gained or lost after the intervention. Three main outcomes emerged: First, patients regained assurance and confidence, which they reported lacking due to pain, suffering, fear related to their low vision, and motor limitations. Second, caregivers experienced reduced stress and worry about their patients, as they had previously reported concern and fear, along with work limitations when providing care. Third, both patients and caregivers enjoyed increased autonomy, understood as freedom to engage in personal activities. Specifically:

• Autonomy Experienced by both patients and caregivers. Patients gained freedom and independence to perform instrumental activities of daily living, while caregivers noted that their patients no longer required assistance for these tasks. The indicators used to assess its validity as an outcome were divided into three evaluation blocks: a) autonomy in household chores, b) patient dependency on caregiver for household and manual activities, and c) self-reported improvements in various activities, including reading, manual labor, and embroidery.

• Assurance Experienced by patients. It refers to assurance and confidence to perform basic activities of daily living such as walking, climbing stairs, and avoiding accidents due to improved vision. The indicators used to assess its validity as an outcome were divided into three evaluation blocks: a) enhanced safety and confidence, b) reduced dependency on assistance for household activities, and c) self-reported improvements in activities and confidence to perform household tasks independently.

• Alleviation Experienced by caregivers. It refers to the reduction in worry and stress related to their patients, attributed to increased independence and optimism following surgery. The indicators used to assess its validity as an outcome were categorized into four evaluation blocks: a) reduced dependency on caregiver for daily activities, b) reported improvement in caregiver’s ability to work and engage in personal activities, c) the state of mental well-being of the caregiver, and d) self-reported changes.

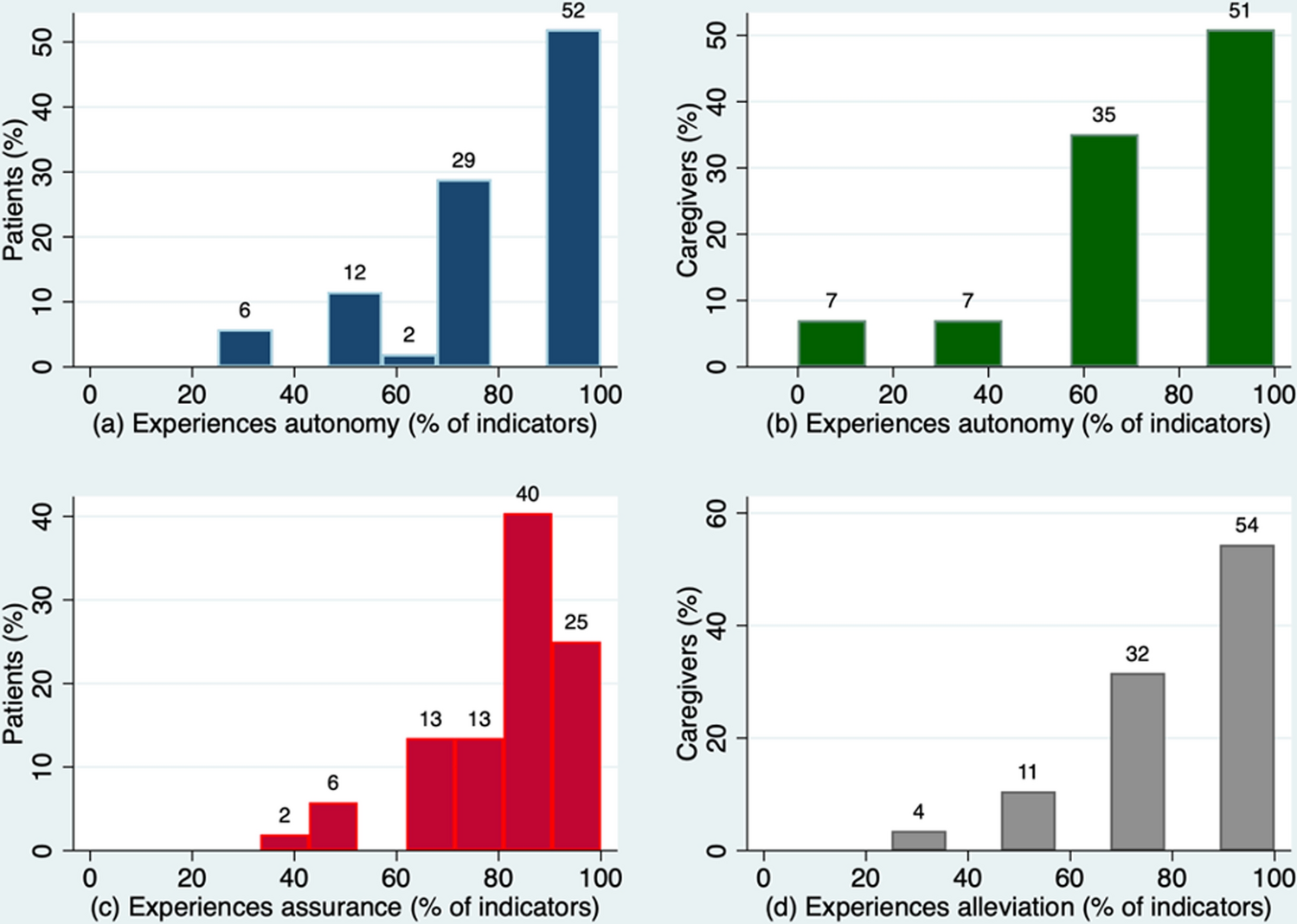

Figure 3 displays the distribution of outcomes among stakeholders. Each graph’s horizontal axis represents the percentage of evaluation indicators where stakeholders indicated agreement, either “agreed” or “strongly agreed,” using the Likert scale. Specifically, 81% of patients indicated agreement with at least 3 out of 4 (75%) autonomy indicators (panel a), while 86% of caregivers indicated agreement with at least 2 out of 3 (67%) autonomy indicators (panel b). In the case of assurance, 78% of patients indicated agreement with at least 6 out of 8 (75%) indicators (panel c), and 86% of caregivers indicated agreement with at least 3 out of 4 (75%) indicators for alleviation (panel d). These thresholds were utilized to determine whether stakeholders experienced the respective outcome in the baseline scenario.

Fig. 3 Outcomes experienced by stakeholders

Duration and Prioritization of Outcomes

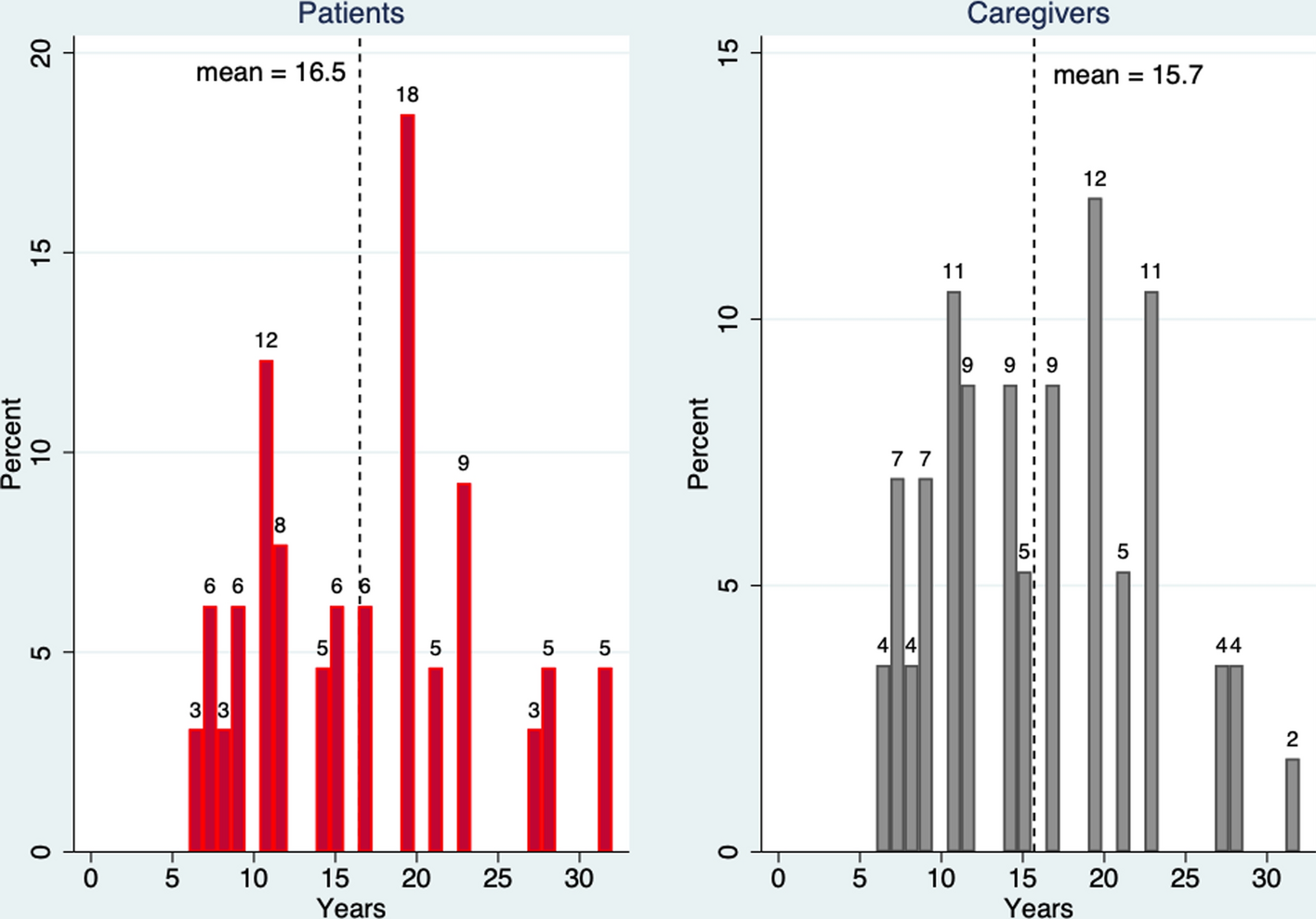

A follow-up interview was conducted to determine the duration of outcomes and their priority for stakeholders. Regarding duration, patients and caregivers were asked how long they believed the changes experienced after cataract surgery would last. The majority responded that they would last for the rest of the patient’s life. Therefore, to establish the baseline scenario’s duration of outcomes for patients, their remaining years of life were calculated by subtracting their age from the 2020 life expectancy by age group for Mexicans, as obtained from the World Health Organization’s life tables by country (WHO, 2020). For caregivers, their remaining years of life were compared to their patient’s expected duration of outcomes, leading to two possibilities: a) If caregivers were expected to live longer than their patients, the duration of their outcomes was set equal to that of their patients. b) If their estimated remaining years of life were shorter than that of their patients, the duration of their outcomes was set equal to their remaining life expectancy. Figure 4 presents the distributions of duration of outcomes. Among patients, the average expected duration of autonomy and assurance is 16.5 years, whereas among caregivers, the average expected duration of autonomy and alleviation is 15.7 years.

Fig. 4 Duration of outcomes experienced by stakeholders

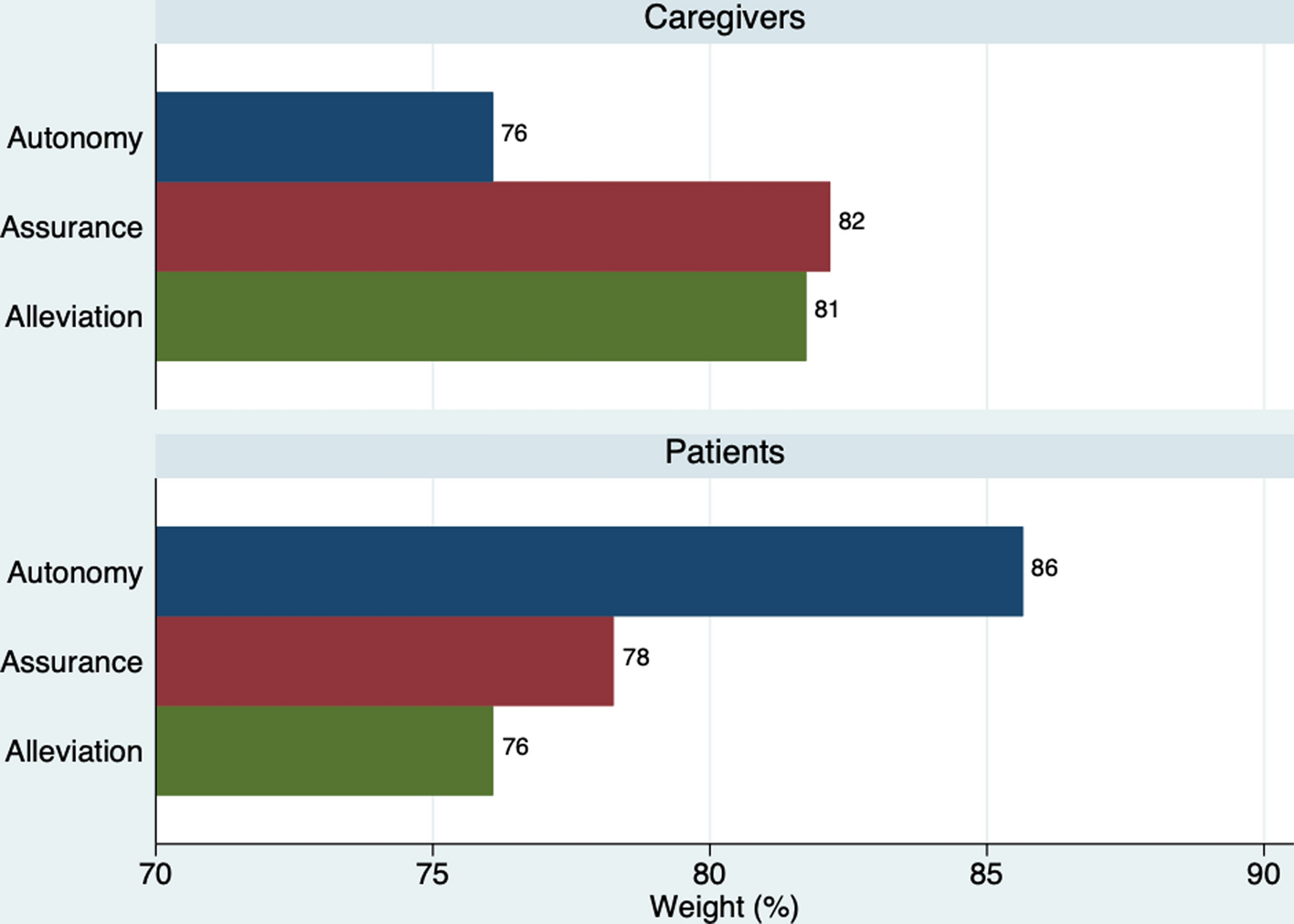

Regarding prioritization, patients and caregivers were asked to rank outcomes on a scale from 1 (most relevant) to 3. These rankings were converted into percentage to reflect the relative importance of each outcome in the evaluation of the intervention. For the baseline scenario, the conversion percentage used were 100% for the most relevant outcome, 80% for the second, and 60% for the third. Figure 5 presents the average weights of outcomes by each group of stakeholders. Among caregivers, the most crucial outcome is their patients’ assurance, followed very closely by the alleviation experienced after cataract surgery. In contrast, patients place a higher priority on regaining their autonomy.

Fig. 5 Prioritization of outcomes experienced by stakeholders

Deadweight and Drop-off

The follow-up interviews also aided in identifying the deadweight and drop-off components of the intervention. Initially, stakeholders were asked to envision what would have occurred if the surgery had not been performed. All expressed that their quality of life would have deteriorated, leading to consequences such as loss of eyesight, increased falls, and emotional distress. This is in line with the findings in Hodge et al. (Reference Hodge, Horsley, Albiani, Baryla, Belliveau, Buhrmann, O’Connor, Blair and Lowcock2007), who observed negative consequences of waiting more than 6 months for cataract surgery. Therefore:

• Deadweight Stakeholders were asked about their ability to seek cataract surgery from another healthcare provider if they had not chosen IMO. Only 11% of patients and 15% of caregivers indicated that they could have sought treatment elsewhere, primarily at the Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS). However, considering the significant waiting times, the likelihood of patients experiencing an improvement in vision in such instances was estimated at 89.7% compared to IMO (Powe, Reference Powe1994).

• Drop-off Benefits from cataract surgery are expected to diminish gradually over time. To account for this, a constant annual reduction of 1.7% for men and 1.3% for women was applied to the outcomes. These percentage correspond to the 2022 death rates per 10,000 inhabitants for Mexicans aged over 65 years (INEGI, 2022a).

Results

Value of Outcomes

For the baseline scenario, outcomes are valued under the following assumptions:

• Autonomy For patients, we calculate the opportunity cost of cataracts as the income they could earn, assuming they worked a maximum of 48 h per week at the prevailing general minimum wage rate of 172.87 pesos per day. This calculation is further adjusted by factoring in the probability of labor force participation by gender and age groups, obtained from the 2020 Population and Housing CensusFootnote 4 (INEGI, 2021c). For caregivers, their opportunity cost is approximated by the income they might earn if they were compensated as domestic personal care workers, also adjusted by their corresponding labor force participation rate. INEGI (2020, 2021b) data indicate that individuals engaged in this type of work typically earn the general minimum wage, working 3.5 days a week if they are men, or 3.7 days a week if they are women. Similar approaches for estimating the value of time have been previously used (e.g., Bhattarai et al., Reference Bhattarai, Carabin, Proaño, Flores-Rivera, Corona, Flisser and Budke2015).

• Assurance and Alleviation To estimate the value of assurance for patients and of alleviation for caregivers, we employ an opportunity-cost measurement approach based on the average quarterly household healthcare expenditures in Mexico, which amount to 1266 pesos. These encompass medical services, medicines, hospital care, orthopedic and therapeutic devices, and medical insurance (INEGI, 2021a). In the case of assurance, we consider that if patients had not undergone surgery, their healthcare-related expenses would likely have remained stable or even increased. This would have placed an economic burden on them, particularly since elderly individuals often contend with progression of visual disabilities and concurrent health issues (Granados-Martínez & Nava-Bolanos, Reference Granados-Martínez and Nava-Bolanos2019). The opportunity cost here represents the potential savings and financial relief that patients experience by choosing to undergo surgery. Concerning alleviation for caregivers, their healthcare-related spending may also be connected to heightened stress and anxiety resulting from their patients’ deteriorating visual conditions. Consequently, the opportunity cost in this context signifies the potential reduction in healthcare-related costs that caregivers gain when their patients opt for surgery.

The monetary value of outcomes is adjusted by the deadweight, and the resulting figures are summed up to obtain the total value per person at the year of the intervention.

SROI Ratio

The total benefit per person from cataract surgery is calculated as the present value of outcomes, which in this case can be computed as a decreasing annuity (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Westerfield and Jaffe1999: 103–106). That is, for each stakeholder

![]() , the benefit is:

, the benefit is:

Here,

![]() is the total value created from cataract surgery at the year of the intervention,

is the total value created from cataract surgery at the year of the intervention,

![]() is the negative of the drop-off rate,

is the negative of the drop-off rate,

![]() is duration of outcomes, and

is duration of outcomes, and

![]() is the discount rate, which in our baseline scenario is equal to the social discount rate of 10% fixed by the Mexican Ministry of Finance and Public Credit for evaluation of investment programs and projects (SHCP, 2022).

is the discount rate, which in our baseline scenario is equal to the social discount rate of 10% fixed by the Mexican Ministry of Finance and Public Credit for evaluation of investment programs and projects (SHCP, 2022).

The individual SROI ratio is then calculated as:

where

![]() is the value of inputs incurred by stakeholder

is the value of inputs incurred by stakeholder

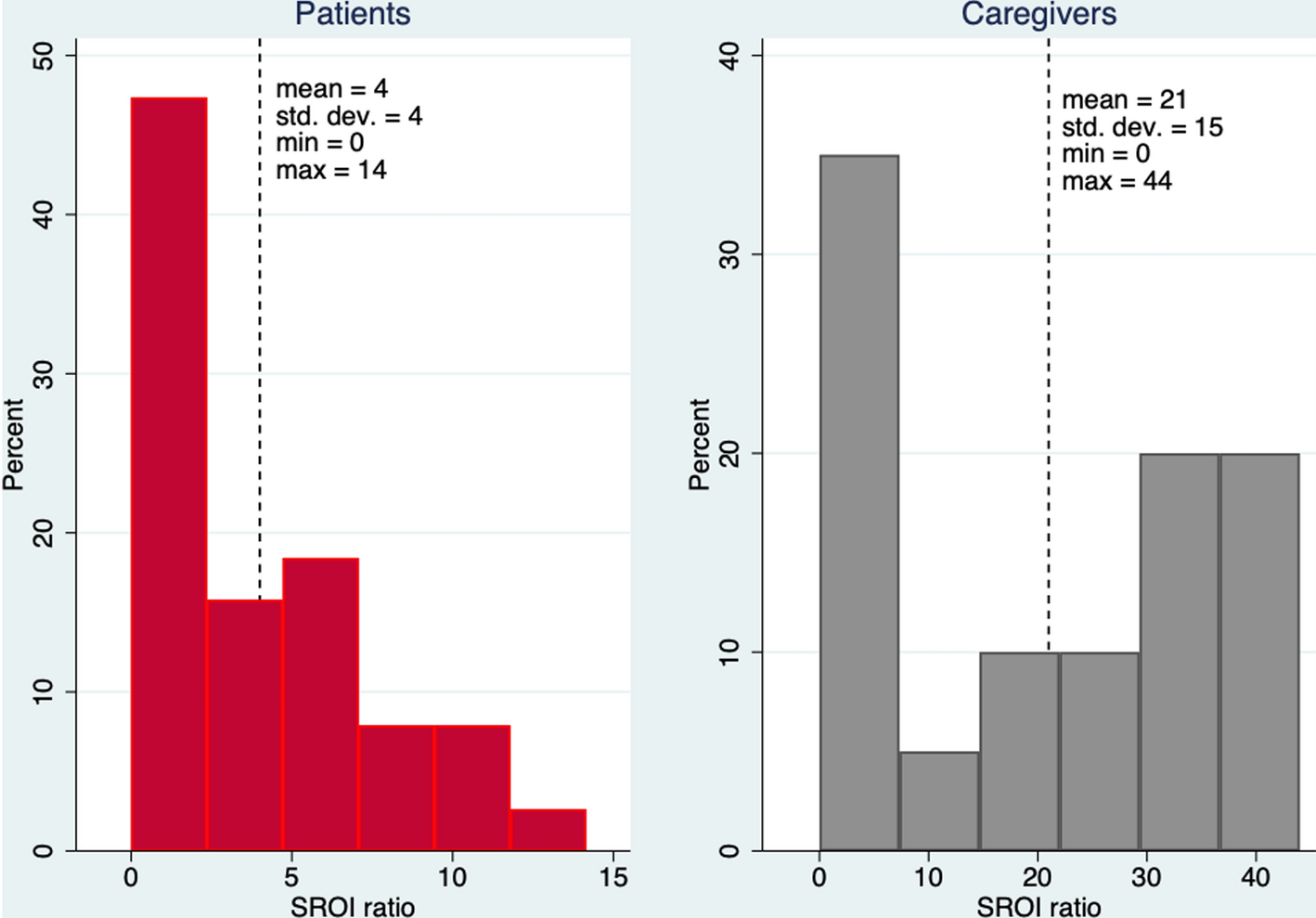

![]() . Figure 6 presents the distribution of individual SROI ratios for patients and caregivers. On average, for every peso invested, patients and caregivers get 4 (or 4:1) and 21:1, respectively, in the form of increased autonomy, assurance, and alleviation. Among patients, 57% of SROI ratios above 4:1 correspond to men aged 54–77 years. Among caregivers, 86% of SROI ratios greater than 21:1 correspond to women aged 23–64 years, who mostly reside in Querétaro and are daughters of their patients. The average SROI ratio among both patients and caregivers is equal to 12:1, with a standard deviation of 14.

. Figure 6 presents the distribution of individual SROI ratios for patients and caregivers. On average, for every peso invested, patients and caregivers get 4 (or 4:1) and 21:1, respectively, in the form of increased autonomy, assurance, and alleviation. Among patients, 57% of SROI ratios above 4:1 correspond to men aged 54–77 years. Among caregivers, 86% of SROI ratios greater than 21:1 correspond to women aged 23–64 years, who mostly reside in Querétaro and are daughters of their patients. The average SROI ratio among both patients and caregivers is equal to 12:1, with a standard deviation of 14.

Fig. 6 Distribution of SROI ratios by group of stakeholders

Another method to calculate the SROI ratio involves aggregating benefits and costs for each patient–caregiver pair

![]() :

:

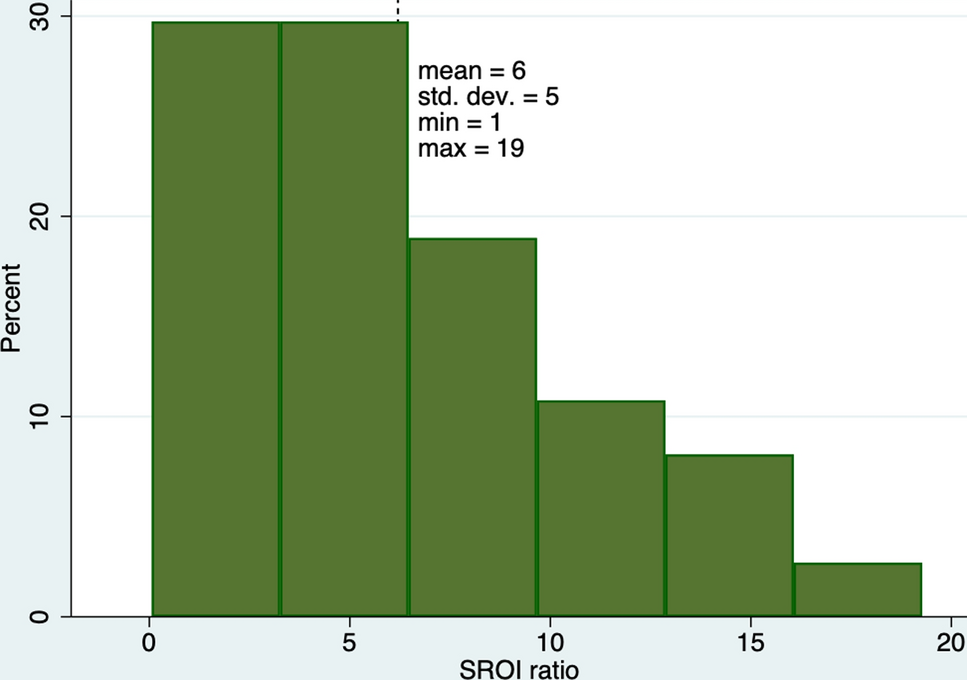

Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of patient–caregiver SROI ratios for pairs in which both stakeholders provided full input and outcome information. On average, each pair generates a return of 6 pesos for every peso invested. Among patients in pairs with ratios exceeding 6:1, the average age is 64 years, 50% are women, and 75% reside in Querétaro. Among the corresponding caregivers, average age is 44 years, 81% are women, 75% are daughters of their patients, and 81% live in Querétaro. Finally, Eq. (3) can also be used for computing aggregated SROI ratios for subgroups

![]() consisting of all patients, all caregivers, and the entire sample combined. In these cases, the estimated social returns for each peso invested in bilateral cataract surgery at IMO are 4:1, 20:1, and 6:1, respectively.

consisting of all patients, all caregivers, and the entire sample combined. In these cases, the estimated social returns for each peso invested in bilateral cataract surgery at IMO are 4:1, 20:1, and 6:1, respectively.

Fig. 7 Distribution of SROI ratios for patient–caregiver pairs

Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of these results concerning key parameters, variables, or criteria, we conduct the following sensitivity analyses:

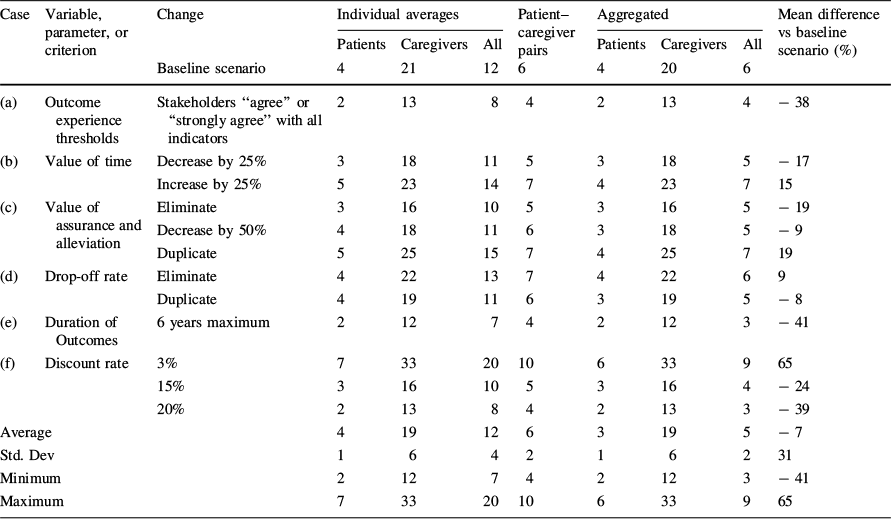

• Outcome experience thresholds As explained in Sect. 2.4, the baseline scenario assumes that stakeholders experience an outcome if they declare to “agree” or “strongly agree” with at least 3/4 autonomy indicators for patients and 2/3 for caregivers, 6/8 for patients’ assurance, and 3/4 for caregivers’ alleviation. We make these criteria stricter, requiring that an outcome is experienced only when the person “agrees” or “strongly agrees” with all its indicators. The results are presented in Table 2 case (a). The SROI ratios decrease on average by 38% compared to the base scenario.

• Value of time As mentioned in Sects. 2.3 and 3.1, the time allocated by stakeholders to cataract surgery and the autonomy recovered after the intervention are valued at the 2022 minimum daily wage of 172.87 pesos. We now adjust this reference value by ± 25 percent. The results are shown in case (b) of Table 2. Modifying the opportunity cost of time induces average changes in SROI ratios of −17% and + 15%, respectively, compared to the baseline scenario.

• Value of assurance and alleviation We described in Sect 3.1 that the value of these two outcomes is proxied using the 1266 pesos that the average Mexican household spends quarterly on healthcare. To determine the sensitivity of our estimates to this parameter, we eliminate, halve, and double its amount. Results are reported in case (c). When assurance and alleviation are ignored, the SROI ratios decrease by 19% on average. When the reference value is halved, the ratios decrease by 9%, whereas they increase by 19% when such value is doubled.

• Drop-off rate As explained in Sect. 2.6, the baseline scenario used the death rates per 10,000 inhabitants for Mexicans over 65 years of age (1.7% for men and 1.3% for women) as drop-off rates for benefits in future years. We eliminate and double these rates, reporting the corresponding results in case (d). SROI ratios change on average by + 9% and −8%, respectively.

• Duration of outcomes It was mentioned in Sect. 2.5 that the duration of outcomes for patients and caregivers is determined by their remaining years of life, estimated from the WHO’s,2020 life expectancy tables. In case (e) of Table 2, we restrict the duration of outcomes to 6 years, including year 0 when the intervention takes place. This aligns with some practical considerations, such as funding cycles (organizations often plan and fund interventions based on multi-year cycles, making a 6-year duration more relevant), or communication of results (a 6-year duration may be preferred by decision-makers, as it provides a reasonable long-term perspective without extending too far into the future). On average, SROI ratios decrease by 41% compared to the baseline scenario.

• Discount rate Finally, we also evaluate the effect of changing the discount rate. Under the baseline scenario it is set at 10 percent, in line with the rate for socio-economic evaluation of investment programs and projects established by SHCP. We now change it to 3, 15, and 20 percent, reporting the results in case (f). The average changes in SROI ratios are + 65%, − 24% and − 39%, respectively.

Table 2 Sensitivity analysis

Case |

Variable, parameter, or criterion |

Change |

Individual averages |

Patient–caregiver pairs |

Aggregated |

Mean difference vs baseline scenario (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Patients |

Caregivers |

All |

Patients |

Caregivers |

All |

|||||

Baseline scenario |

4 |

21 |

12 |

6 |

4 |

20 |

6 |

|||

(a) |

Outcome experience thresholds |

Stakeholders “agree” or “strongly agree” with all indicators |

2 |

13 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

4 |

− 38 |

(b) |

Value of time |

Decrease by 25% |

3 |

18 |

11 |

5 |

3 |

18 |

5 |

− 17 |

Increase by 25% |

5 |

23 |

14 |

7 |

4 |

23 |

7 |

15 |

||

(c) |

Value of assurance and alleviation |

Eliminate |

3 |

16 |

10 |

5 |

3 |

16 |

5 |

− 19 |

Decrease by 50% |

4 |

18 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

18 |

5 |

− 9 |

||

Duplicate |

5 |

25 |

15 |

7 |

4 |

25 |

7 |

19 |

||

(d) |

Drop-off rate |

Eliminate |

4 |

22 |

13 |

7 |

4 |

22 |

6 |

9 |

Duplicate |

4 |

19 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

19 |

5 |

− 8 |

||

(e) |

Duration of Outcomes |

6 years maximum |

2 |

12 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

12 |

3 |

− 41 |

(f) |

Discount rate |

3% |

7 |

33 |

20 |

10 |

6 |

33 |

9 |

65 |

15% |

3 |

16 |

10 |

5 |

3 |

16 |

4 |

− 24 |

||

20% |

2 |

13 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

3 |

− 39 |

||

Average |

4 |

19 |

12 |

6 |

3 |

19 |

5 |

− 7 |

||

Std. Dev |

1 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

31 |

||

Minimum |

2 |

12 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

12 |

3 |

− 41 |

||

Maximum |

7 |

33 |

20 |

10 |

6 |

33 |

9 |

65 |

||

In summary, the sensitivity analyses reveal that the SROI ratio is particularly sensitive to outcome experience thresholds, duration of outcomes, and the discount rate. As shown in Table 2, the average individual SROI ratio across all stakeholders and alternative scenarios is 12:1, with values ranging between 7:1 and 20:1. The average for patient–caregiver pairs is 6:1, with a minimum of 4:1 and a maximum of 10:1. The cumulative ratio for all stakeholders is 5:1, with values ranging between 3:1 and 9:1. Lastly, the overall average SROI ratio across all cases in Table 2 is 10:1, with values between 2:1 and 33:1. Thus, under the most restrictive scenario stakeholders obtain a return of at least 2 times their investment, while this gain can be 33 times higher under the most optimistic scenario.

Conclusions

Cataract surgery is a rapid visual improvement procedure (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wilkins, Kim, Malyugin and Mehta2017) with minimal complications that has proven effects on quality of life (Lamoureux et al., Reference Lamoureux, Fenwick, Pesudovs and Tan2011), vision restoration, and amelioration of psychosocial impairments (Zitha & Rampersad, Reference Zitha and Rampersad2020). In this study, we have undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the Social Return of Investment (SROI) of bilateral cataract surgery at IMO, a Mexican nonprofit organization. Our research aimed to assess the social value created by this intervention and provide insights for both practitioners and policymakers in the nonprofit sector.

We quantified outcomes experienced and reported by patients and caregivers, including increased autonomy, assurance, and alleviation of caregiving burdens. Our results have substantial implications, extending beyond the boundaries of nonprofit healthcare provision. The analysis showed that nonprofit bilateral cataract surgery services have positive effects for both stakeholders. Our baseline setting yielded an average SROI ratio of 12:1 at the individual level, 6:1 for the average patient–caregiver pair, and 6:1 at the cumulative level for all patients and caregivers in our sample. We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of changes in key parameters and criteria, underscoring the robustness of our results and the versatility of the SROI methodology for nonprofit impact assessment.

Our study provides insights into the economic theories of the third sector. Nonprofits may operate along with the public and for-profit private sectors to address complex societal challenges, enhancing the effectiveness of initiatives by addressing gaps and unmet needs. Our findings reaffirm the relevance of the complementary role of nonprofits in the healthcare ecosystem. Likewise, nonprofits can step in to supplement public services and mitigate market failures. IMO also exemplifies this, since it bolsters healthcare accessibility for vulnerable populations, particularly low-income individuals with no access to social security.

A salient revelation of our study pertains to its implications for labor force participation among young female caregivers. Our results suggest that alleviating their caregiving responsibilities through successful cataract surgeries can enhance their economic prospects. As these caregivers experience reduced stress and work limitations, it is conceivable that more young women may be encouraged to participate in the labor force. This observation aligns with broader efforts to promote gender equality and female workforce engagement, emphasizing the transformative potential of nonprofit interventions in addressing labor market dynamics.

We must nonetheless acknowledge the limitations of our study. While we have designed our research to ensure the reliability and validity of our findings, there may be inherent limitations stemming from factors such as sample representativeness. This study focused on bilateral cataract surgery at the IMO, a specific intervention within a defined context, and while it provides valuable insights, generalizing these results to broader nonprofit initiatives necessitates caution. Future research should consider larger samples and diverse contexts to further enhance the robustness and applicability of results.

Overall, measuring the SROI of bilateral cataract surgery can contribute to ongoing efforts to gain support and reduce the prevalence of this and other diseases. Public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries face significant challenges in delivering timely and adequate care to patients. Nonprofits can help address this gap by offering affordable and effective eye care services. Understanding the costs and benefits of their actions is essential for optimizing resource allocation while improving their social value and financial sustainability. SROI offers a valuable approach to assess the broader effects of nonprofit interventions, informing decision-making, enhancing service delivery, contributing to knowledge sharing, and improving management accountability and transparency.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by POR and DEV. Analysis and interpretation of the data were performed by BA, POR, and EMLS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by BA and POR, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data are not publicly available due to ethical, legal, or other concerns.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no funding, financial, non-financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work. While the corresponding author has been engaged as an external collaborator by the IMO for this project, this does not affect the impartiality and independence of the research presented in this paper. The co-authors also declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the findings and conclusions of this study.

Human or Animal Right

This study was approved by the IMO’s Ethics Committee (registration code CONBIOETICA 22-CEI-003-2016215), in accordance with Mexican regulation NOM 012-SSA3-2012 and the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.