Introduction

Coalition bargaining is a central feature in many parliamentary democracies. When no single party commands a majority of seats after an election, the party composition of the next government and its policies often depend on the outcomes of coalition talks. How do party supporters evaluate the outcomes of these talks? On the one hand, we know that voters are more satisfied with the political system when their party is in government (Anderson & Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Blais & Gelineau Reference Blais and Gelineau2007; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012), arguably because this increases the chances that government policy is closer to their own preferences (Kedar Reference Kedar2005; Bargsted & Kedar Reference Bargsted and Kedar2009). On the other hand, parties need to compromise to reach a coalition deal, and voters tend to punish parties for breaking their election pledges (Matthieß Reference Matthieß2020) and for compromising too much (Fortunato Reference Fortunato2019). How do voters solve this tension between power and compromise? On what issues should their party stand strong and under what conditions should the party leadership give in?

To shed light on these questions, in this article we explore the preferences of party supporters during government formation processes. We argue that supporters’ acceptance of policy compromise by the party leadership depends on the strength of their party attachment and the issue at stake in the negotiations: core party supporters should be less likely to accept policy compromises than voters with a weaker attachment to that party. Moreover, party voters should show less willingness to accept policy compromises during the negotiations if the issue is important to them personally. Making concessions on important issues should be particularly difficult for supporters of ‘challenger parties’ (De Vries & Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020) whose electoral appeal crucially depends on their defining issue as political entrepreneurs.

We test these expectations using original survey data collected immediately after the Spanish general election on 10 November 2019. Spain is a particularly suitable case for testing our hypotheses as it is one of the few consensual systems in which coalitions are a new phenomenon at the national level. This limits the risk that preferences for coalitions and coalition compromises are endogenous to coalition governments formed in the past (Guntermann & Blais Reference Guntermann and Blais2019). We fielded our survey immediately after the election, when government formation was salient in voters’ minds, but prior to the signing of the coalition agreement that in itself was likely to influence voter preferences. To examine whether voters prefer their party to compromise on specific policy issues, we confronted voters with a coalition alternative (including their most preferred party) and asked them to identify the most contentious issue in potential coalition talks. Our focus in this study is on whether voters prefer their party to make significant policy concessions to its coalition partners for the sake of forming a coalition government, or whether to stick to its policy positions no matter what.

Our findings reveal substantial variation in supporters’ willingness to accept policy compromises in coalition negotiations. In line with our expectations, the stronger one's party attachment, the less likely one is to accept policy compromises. Moreover, voters’ willingness to accept policy compromises is significantly lower if an issue is personally important to party supporters; this effect is stronger for supporters of challenger parties.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of political representation and government formation processes. They shed light on the linkage between citizens and political elites after election campaigns, highlighting that party supporters accept the necessity of making policy concessions to political competitors. We also identify conditions under which citizens grant their party more leeway in the negotiations and where they expect their party to stand firm on its policy proposals. These expectations at the outset of coalition negotiations additionally facilitate our understanding of which parties are more likely to pay an electoral price for their participation in government (e.g., Narud & Valen Reference Narud, Valen, K., Wolfgang C. and Torbjörn2008; Klüver & Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2020).

Furthermore, the results show that policy compromises in coalition negotiations are not necessarily zero‐sum. If the supporters of the negotiating parties prioritize different issues, the parties can find mutually beneficent deals by conceding on those issues that are relatively unimportant to their supporters (Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2020). Moreover, challenger parties should be particularly unwilling to accept compromises on their supporters’ most important issues, but in turn be more likely than mainstream parties to accept policy concessions on less important concerns. There is a correspondence between these expectations and the results of actual government formation processes, as parties are more likely to gain control over policy areas about which they care (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Schermann & Ennser‐Jedenastik Reference Schermann and Ennser‐Jedenastik2014).

The expectations of party supporters also create ‘red lines’ for parties in the coalition negotiations (Warwick Reference Warwick2006). Given that compromising on important issues may result in electoral punishment in the future, voters’ unwillingness to compromise may bind party leadership in ways similar to intra‐party constraints in the government formation process (Bäck Reference Bäck2008; Ceron Reference Ceron2016): the higher the share of party voters who are unwilling to compromise, the lower a party's chances of entering government. Nevertheless, once included in a formation attempt, the constraints posed by party supporters may serve as credible signals to potential coalition partners that a party cannot concede any further (for a similar argument with regard to intra‐party conflict, see Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Debus and Gross2017).

Voters’ perceptions of government formation in multi‐party systems

There is extensive research showing how voters anticipate the formation of multi‐party governments after Election Day. Voters have opinions about the (expected) policy output for different coalition alternatives (Meffert & Gschwend Reference Meffert and Gschwend2012; Meyer & Strobl Reference Meyer and Strobl2016) and preferences for potential coalition alternatives (Falcó‐Gimeno Reference Falcó‐Gimeno2012; Plescia & Aichholzer Reference Plescia and Aichholzer2017). These coalition preferences also inform vote choices, as voters anticipate coalition bargaining (Kedar Reference Kedar2005, Reference Kedar2009) and tend to support parties that move coalition policy closer to their own policy preferences (Blais et al. Reference Blais, Aldrich, Indridason and Levine2006; Bargsted & Kedar Reference Bargsted and Kedar2009; Duch et al. Reference Duch, May and Armstrong2010; Meffert & Gschwend Reference Meffert and Gschwend2010; Indridason Reference Indridason2011).

Relatively little is known, however, about how voters evaluate the government formation process itself. One study by Plescia and Eberl (Reference Plescia and Eberl2019) asked voters to identify the party that, in light of the election results, should be included in the next government. The authors found stark differences across voters and in particular a tendency of voters with populist attitudes to rule out certain parties as potential coalition partners. Another study by Matthieß and Regel (Reference Matthieß, Regel, Kneip, Merkel and Weßels2020) looked into voters’ willingness to accept policy compromises between coalition partners, finding that supporters of challenger parties (without government experience) are the least likely to accept the necessity of coalition compromises. Nevertheless, many open questions remain. For example, we still do not know under what conditions party supporters are willing to accept policy concessions to coalition partners. Below, we develop a series of hypotheses explaining why party voters differ in their acceptance of policy compromises and concessions to coalition partners and test them with original data.

Evaluating policy compromises in coalition governments

Here we develop a theoretical framework explaining how party supporters evaluate potential outcomes of the government formation process. Our focus is on the necessary policy compromises during coalition bargaining. We assume that a key element of coalition negotiations is to resolve policy conflicts between potential coalition partners. Moreover, we assume that party supporters care about the decisions reached in the coalition negotiations and that they prefer their party's policy stands to those of potential coalition partners or to a compromised position.Footnote 1 The expected policy payoff for party supporters is maximized when their party rules alone or when it is the most successful in pushing its policy position during coalition talks. In this process, we focus on whether some party supporters are more willing than others to accept compromises and on whether certain issues are less likely to be ‘compromised’.Footnote 2

In the negotiation process, either party may be able to push through its policy position, or the potential coalition partners may agree on a policy compromise. Party supporters face a trade‐off when evaluating policy outcomes from such a bargaining process: while a coalition compromise implies policy concessions to those that were political competitors during the previous election campaign, such an agreement increases the chances of a smooth and successful government formation process. In turn, standing strong on an issue stance may reduce policy losses, but it also delays the government formation process and may eventually lead to a breakdown of the coalition talks and the exclusion of that party from the government.

We argue that whether party supporters are willing to accept a policy compromise depends on the strength of voters’ attachment to their party and the issue that is at stake in the negotiations. First, we expect a strong attachment to a party in order to render the acceptance of coalition compromises more difficult for party supporters. Multi‐party bargaining ‘activates’ citizens’ partisan identities, in turn ‘priming’ their in‐group versus out‐group policy benefits. Party attachment works as a ‘perceptual screen’ or judgmental shortcut, which provides citizens with efficient ways of organizing and simplifying political choices (Lau & Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001; Taber & Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006). This role is especially important during coalition talks when parties discuss complex issues, most of which are detached from voters’ everyday concerns. The stronger voters’ attachment to the party, the more their in‐group versus out‐group identities are likely to be activated during coalition negotiations. In the context of bipartisan compromise in the United States, Harbridge et al. (Reference Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison2014) have addressed the theoretically relevant distinction between general attitudes towards ‘compromise in the abstract’ and ‘specific compromise on certain policies’, finding evidence that while most people support the former, there is a consistent preference for partisan victories that often trump preferences for partisan agreement.

Other experimental studies have confirmed that strong partisanship consistently predicts anti‐deliberative attitudes; that is, partisans are consistent in their pursuit of partisan goal seeking, ‘[standing] fast and [rejecting] middle‐ground compromises’ (MacKuen et al. Reference MacKuen, Wolak, Keele and Marcus2010: 440; see also Gervais Reference Gervais2019). There is now substantial evidence both in the United States and elsewhere consistent with theories in political psychology on partisan goal seeking and partisan social identities; compromise is often interpreted as a ‘loss’ for the party and, given partisanship attitudes to cheerleading for one's own party, partisans tend to display the greatest resistance to conceding any ground.

Arguably, in a multi‐party context, in‐ and out‐group dynamics are even more complex, because coalition talks may bring a variety of parties together with diverse prior coalition experiences. It is plausible that the out‐group perceptions against another party are weaker if that party has governed with one's preferred party in the past and stronger if that party has not previously formed government coalitions with one's preferred party. In any case, given that core supporters have the strongest ties to a party and its ideology and issue positions, they should be less likely to accept policy concessions than other party voters. Hence, we expect:

H1: The more attached supporters are to a party, the less willing they are to accept a coalition compromise.

Voters’ willingness to accept policy compromises should also vary across issues. In particular, we argue that party supporters are less likely to accept policy compromises if an issue is important to them. Coalition negotiations are concerned with multiple issues where parties have conflicting issue stances. However, party supporters are unlikely to care about all of these issues equally. Previous studies in political psychology have shown that ‘people do not pay attention to everything’ (Iyengar & Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987: 64) and the knowledge and attention they pay to each issue is strongly moderated by the amount of significance they ascribe to it (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Bizer and Krosnick2006). Voters also evaluate a party's competence (Bélanger & Meguid Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008) and positions (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006), particularly on those issues that are personally important to them. When evaluating the coalition bargaining process, party supporters should likewise attribute a higher value to a party's negotiation success on issues that matter most to them and be less likely to accept concessions to coalition parties on these issues.

When the issue preferences of party supporters differ across party lines, this also creates incentives for the negotiating parties to logroll policy in the negotiation process (de Marchi & Laver Reference Marchi and Laver2020): pushing through a party's issue stance on issues that are important to its supporters and conceding on other issues which the (potential) coalition partner's supporters care (more) about. Indeed, several studies (e.g., Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Schermann & Ennser‐Jedenastik Reference Schermann and Ennser‐Jedenastik2014) have shown that parties tend to do well in negotiations on issues that are central to their agenda. In sum, we expect:

H2: The more important an issue is to party supporters, the less willing they are to accept a coalition compromise.

Finally, we hypothesize that the trade‐off between compromising and pushing through positions is different for supporters of mainstream and challenger parties. Challenger parties act as issue entrepreneurs who aim to disrupt the power of established parties (De Vries & Hobolt 2020). They are relatively new and, in contrast to their mainstream counterparts, are ‘unconstrained by the responsibilities of government’ (Hobolt & Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016: 972). Challenger parties thus have more ‘room for manoeuvre’ when talking about policy issues, because they do not need to be responsible to the (national and international) policy constraints typically faced by mainstream parties (Mair Reference Mair and Mair2014).

Challenger parties are likely to focus on ‘new politics’ issues and often use anti‐establishment rhetoric to mobilize electoral support (De Vries & Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). For instance, they may use issues such as immigration or European integration to divide (government) parties or coalition governments (Van de Wardt et al. Reference Van de Wardt, Vries and Hobolt2014). As these ‘wedge issues’ are their designing feature, challenger party supporters care deeply about them (De Vries & Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Marchi and Laver2020; Hobolt & Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016). This means that when they approach the coalition negotiation table, challenger parties are in the uncomfortable position of staying strong on the issues on which they have campaigned (Van de Wardt et al. Reference Van de Wardt, Vries and Hobolt2014). At the same time, however, these parties are more flexible on issues that are not closely related to their raison d'être.

Once challenger parties become viable coalition partners, they (and their supporters) need to deal with a substantial trade‐off. On the one hand, they have ample room for manoeuvre and because they are usually regarded as junior coalition partners and contribute fewer resources (e.g., seats) to the coalition (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello and Ennser‐Jedenastik2017), they are willing to accept less influence on many government policies. On the other hand, however, their electoral base holds strong policy preferences on a selected number of issues. If such a party enters a coalition government (and thus enters the ‘mainstream’), its supporters are expected to be less likely to accept coalition compromises on their core issues than are supporters of mainstream parties.

Given their particular situation, supporters of challenger parties should be more likely to trade off their willingness to compromise depending on the issue's saliency than are supporters of mainstream parties: challenger party supporters may be more willing to compromise on issues that are not important to them. However, they are likely to be less willing to accept policy compromises on their most important issue concerns. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3: The effect of issue saliency on one's willingness to compromise (Hypothesis 2) is stronger for supporters of challenger parties than for those supporting mainstream parties.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we collected original data in the immediate aftermath of the general election held in Spain on 10 November 2019. Spain is a particularly suitable case to test our expectations. Coalition governments formed in the past tend to affect voters’ current coalition preferences (Guntermann & Blais Reference Guntermann and Blais2019) and may likewise affect how willingly party supporters accept policy compromises. Given that Spain is one of the few parliamentary systems in Europe where coalitions are a new phenomenon at the national level, this risk is minimized.

Interviews were conducted in the time window between the end of Election Day and the start of coalition negotiations; specifically, interviews started on 11 November (i.e., the day after the election) and finished on 19 November, the overwhelming majority being conducted before 16 November.Footnote 3 Embedding the survey in a real election context and government formation process rather than a fictitious scenario has two advantages. First, studying real elections means that the external validity of our study is much higher than, for instance, convenience samples or laboratory experiments (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Kuklinski, Quirk, Peyton and Verkuilen2007). Second, surveys embedded in real‐world elections give us the opportunity to tap into and use the actual party preferences of participants compared to purely fictional election campaigns (Meffert & Gschwend Reference Meffert and Gschwend2011). Election campaigns activate voters’ interests and partisan preferences, so we expect coalition compromise to matter especially when parties begin engaging in coalition talks.

Respondents were selected (quota sample) based on the following key demographics: age, gender, region and educational level based on census data. The quota sample was structured to closely represent the Spanish population (see Supporting Information Appendix, Table A1). We identified party supporters using the following survey question: ‘Using the scale from 0 “not at all likely” to 10 “very likely”, how likely is it that you would ever vote for each of the following parties?’ The list of parties included the five main parties in Spain, namely the People's Party (PP), the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Podemos (UP), Citizens (Cs) and VOX. This information allowed us to identify each respondent's most preferred party.Footnote 4

The party composition of the next government was rather uncertain after the 2019 November election: no single party and no bloc had reached a majority in parliament and ‘very difficult government negotiations’ were the expected consequence.Footnote 5 PSOE and UP had tried to form a coalition after the general election in spring earlier that year, but the failed bargaining attempt eventually led to the 2019 November election. Cs suffered at the polls, but its leader resigned after Election Day, possibly to clear the way for a cooperation with PSOE.Footnote 6 PSOE had ruled out forming a coalition with PP before the election, but given the lack of clear alternatives with a majority in parliament, this option was at least theoretically still on the table. Finally, VOX doubled its seat share in the 2019 November election. Despite gaining electoral support, its coalition potential was limited, however.Footnote 7

Amid the uncertainty surrounding the party composition of the next government, we considered four alternative coalitions discussed by the media both during the election campaign and in the aftermath of the election: (1) the grand coalition between PP and PSOE; left‐leaning coalitions between (2) PSOE and UP and between (3) PSOE and Cs; and (4) a right‐leaning coalition between PP, VOX and Cs. Respondents answered two questions concerning a coalition government including their most preferred party. If the most preferred party had several reasonable coalition options, we randomly selected one of the coalition alternatives. For example, PP supporters were randomly assigned to a coalition government with PSOE or with VOX and Cs.Footnote 8

First, we asked respondents to identify the most contentious issue in these negotiations.Footnote 9 Thus, in our survey, respondents identified the most contentious issue themselves to avoid the risk of asking for non‐attitudes (e.g., if voters do not see an issue as particularly divisive among the coalition partners). Respondents could choose among seven issues, which differed substantially in terms of the relevance they had during the election campaign. The list of issues was as follows: ‘Economy/taxation’ (chosen by 23.1 per cent of the respondents), ‘The state of the autonomies/the territorial issue’ (chosen by 32.6 per cent), ‘Redistribution of wealth/social assistance’ (chosen by 17.7 per cent), ‘Immigration’ (chosen by 11.7 per cent), ‘Climate change and environmental protection’ (chosen by 3.9 per cent), ‘European integration’ (chosen by 1.9 per cent) and ‘Rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people’ (chosen by 9.1 per cent). These issues also differed in terms of their relevance for specific party supporters. For example, immigration was a much more salient issue for VOX supporters than all the other party supporters.

Second, we measured respondents’ willingness to accept policy compromise on the issue at hand on a 0−10 scale, where 0 indicated that ‘the [most preferred party] should be true to its principles no matter what’ and 10 indicated that ‘the [most preferred party] should make significant concessions to reach a compromise with [coalition partner(s)] to get things done’.Footnote 10 Higher values on this 0−10 scale indicated a higher willingness to compromise. This was the dependent variable of our study.

Our key independent variables were strength of party identification, issue saliency and challenger party supporters. The measurement of the former relied on a commonly employed survey question asking respondents first, whether there was a party to which they felt close and, if so, to indicate first the party and then how attached they felt to it using a scale from ‘not very close’ to ‘very close’, with an intermediate value ‘somewhat close’. Using these questions, we built a variable of party identification strength that took a value of ‘0’ if respondents did not identify with any of the parties in the coalition, ‘1’ if they identified with one of the parties and answered that they did not feel very close, ‘2’ if they felt somewhat close and ‘3’ if they felt very close. We measured issue saliency with a question asking respondents how important on a scale from ‘0’ ‘not at all important’ to ‘10’ ‘very important’ was the issue they mentioned as being the most contentious in coalition negotiations. Another respondent‐specific variable was whether they were supporters of a challenger party. Following De Vries and Hobolt (Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Marchi and Laver2020), we classified UP, Cs and VOX as challenger parties, as these parties have not been in government (at the national level) so far.

Besides controlling for standard variables like age (in years), gender (dummy variable for female respondents) and education (from lowest coded as 1 to highest coded as 8), we controlled for negative partisanship for the coalition partner(s). Our justification for the inclusion of the latter variable is that while our theoretical interest is on in‐group bias (Hypothesis 1), willingness to compromise with a coalition partner may also be a matter of out‐group perceptions. Following previous research (Rose & Mishler Reference Rose and Mishler1998; Medeiros & Noël Reference Medeiros and Noël2014; Spoon & Kanthak Reference Spoon and Kanthak2019), we measured negative partisanship based on voters’ intentions to ‘never vote for a party’. Specifically, we took the propensity to vote (PTV) score for the coalition partner (the mean score weighted by their seat strength in the case of more than one coalition partner) and reversed the 0−10 scale, so that higher values indicated more negative partisanship. We also added issue fixed effects and coalition fixed effects in our regression models. The former aimed to capture any issue‐specific heterogeneity because some issues might genuinely make compromise more difficult due to their nature as ‘principled issues’ (Tavits Reference Tavits2007). The coalition fixed effects aimed to control for any unmeasured confounders at the coalition level; this enables us to assess the effect of our independent variables of interest ‘net’ of the influence of coalition‐specific utility. Using party‐specific coalition fixed effects instead of coalition fixed effects led to identical conclusions (see Table A6 in the Supporting Information Appendix). Table A3 in the Supporting Information Appendix shows descriptive statistics for all our variables.

Testing the hypotheses on coalition compromise

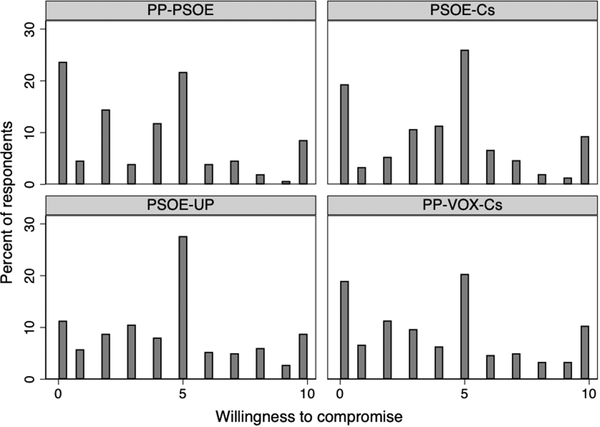

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of our dependent variable for each of the four coalitions. As the figure shows, there was considerable variation across respondents in their willingness to compromise. Respondents chose the full range of values, including the two extremes. Across all coalitions, about half of the respondents showed a willingness to compromise between 5 and 10. On average, willingness to compromise was highest for the PSOE–UP coalition (mean: 4.54, SD: 2.88) and lowest for the grand coalition PP–PSOE (mean: 3.58, SD: 2.95). All in all, however, the distribution of the dependent variable across coalitions was rather similar and the only difference that reached conventional levels of statistical significance was the one between PP–PSOE and PSOE–UP (see also Table A5 in the Supporting Information Appendix).

Figure 1. Distribution of dependent variable by coalition

Notes: Data unweighted.

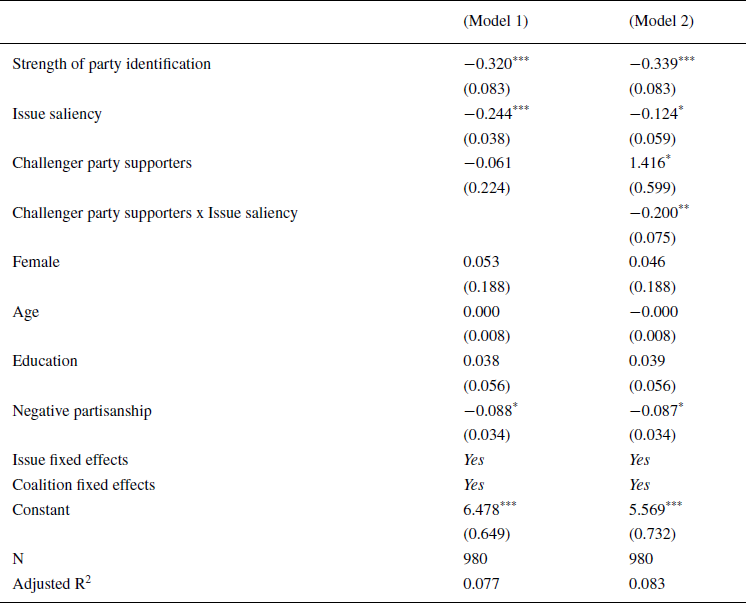

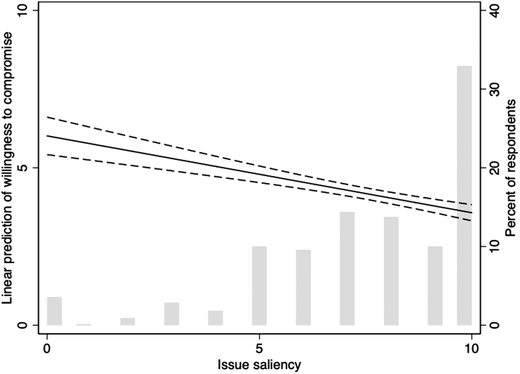

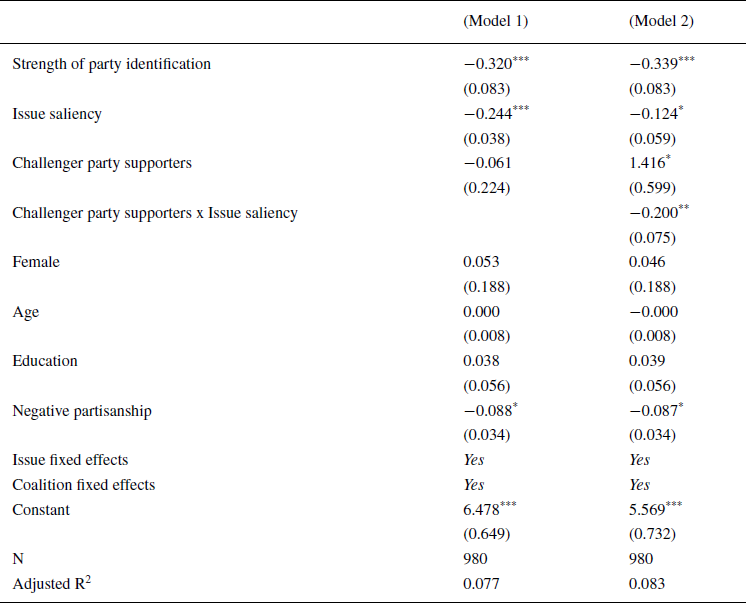

Given that our dependent variable ranged from 0 to 10, we treated it as continuous and ran ordinary least square regression models.Footnote 11 In Model 1 in Table 1, the effect of strength of party identification was negative and significant, indicating that party identification is an obstacle to conceding ground during negotiation talks, as implied by Hypothesis 1.Footnote 12 A one‐unit increase in the party identification variable was associated with a decrease of about 0.3 points on the 11‐point willingness to compromise scale; in other words, those without party identification were on average about one point more willing to compromise than strong party supporters. The results also indicate that issue saliency is consistently and negatively associated with willingness to compromise: the more important an issue, the less likely party supporters are to concede ground on that issue, in line with Hypothesis 2. The expected values of willingness to compromise across the entire range of issue saliency are shown in Figure 2. As apparent from the scheme, increasing the saliency of the issue at stake from 6 (1st quartile) to 10 (3rd quartile) decreased respondents’ willingness to concede ground by one scale point. By contrast, the effect of challenger party supporters in Model 1 was negative but not statistically significant; this suggests that willingness to compromise does not differ for supporters of mainstream and challenger parties.Footnote 13

Table 1. Effects partisanship, issue saliency and challenger party support on willingness to compromise

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 2. The effect of issue saliency on willingness to compromise

Notes: The plot shows linear predictions for willingness to compromise and 95 per cent confidence intervals. The plot is based on Model 1 in Table 1 and depicts average adjusted predictions. Grey bars denote the relative frequency of voters’ perceived issue importance.

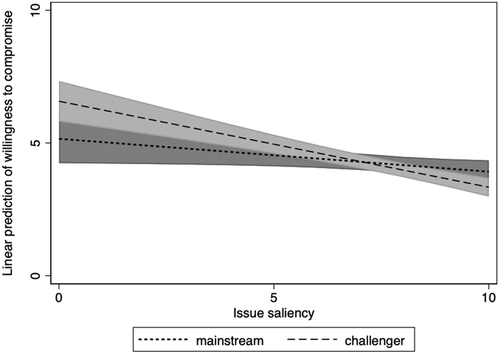

In Model 2 in Table 1 we added an interaction between issue saliency and type of party supporters to provide a test of Hypothesis 3.Footnote 14 The results indicate that if issue saliency is low, challenger party supporters are – all else being equal – more willing to compromise than supporters of mainstream parties. As issue saliency increases, however, they become significantly less willing to compromise. Figure 3 plots the interaction effect, showing how willingness to compromise (y‐axis) changes for different levels of issue saliency (x‐axis) separately for supporters of challenger and mainstream parties. In line with Hypothesis 3, it indicates that the effect of issue saliency on willingness to compromise is stronger for supporters of challenger parties than for those supporting mainstream parties.Footnote 15

Figure 3. The heterogeneous effect of issue saliency on willingness to compromise for challenger and mainstream party supporters

Notes: The plot shows linear predictions for willingness to compromise and 95 per cent confidence intervals for supporters of mainstream and challenger parties separately. The plot is based on Model 2 in Table 1 and depicts average adjusted predictions.

Conclusion

Delays and difficulties in the formation of coalition governments increasingly characterize party politics in multi‐party systems. For example, in Israel, the failure of the coalition negotiations in May 2019 led Benjamin Netanyahu to call new elections for September 2019 and then again in March 2020. There were similar delays in the government formation process in Ireland in 2016, in Germany in 2017 and in Italy and Sweden in 2018. In Spain, eventually, after the November 2019 election, PSOE and UP formed a coalition government following an almost year‐long election campaign and a failed formation attempt after the previous general election held in April 2019.

Although parties may have several reasons for walking away from the negotiation table, coalition bargaining often revolves around parties’ unwillingness to concede ground on key policy issues. In this paper, we have focused on party supporters and their evaluation of the government formation process. We have found that party supporters are willing to accept concessions made in coalition talks, but less so if they have a strong party identification and care about the issue at stake. Moreover, supporters of challenger parties differ from those supporting a mainstream party: on issues that are not important to them personally, supporters of challenger parties are more likely to accept policy concessions to coalition partners. However, on the most important issues, challenger party supporters are less forgiving than those supporting a mainstream party.

Voters’ willingness to accept concessions in Spain is somewhat surprising given the lack of experience of coalition governments in Spain at the national level. It is possible that electoral fatigue after two snap elections in 2019 increased voters’ willingness to accept policy concessions to finally have a government and ‘get things done’. This might be the case in other countries as well where coalition talks have failed many times (e.g., in Israel 2019−2020) or after unusually long coalition talks like in Germany after the 2017 election or in Italy in 2018. In any case, we believe the basic theoretical propositions and empirical patterns uncovered in this paper should be applicable to, at least, consolidated Western democratic regimes with similar political developments. Nevertheless, it is worth studying such propositions in comparative perspective. For example, we know little about the contextual factors that might affect party supporters’ willingness to accept policy compromises, including the party's previous experiences with coalition governments: voters might be less likely to accept concessions to parties that abandoned previous coalition governments and more willing to give in to coalition partners with whom they have governed successfully. Testing these propositions, however, requires comparative data on voters’ expectations of coalition policy compromises.

Supporters with strong party ties have been found to display the greatest resistance to conceding to coalition partners. This may put parties in odd situations when they lose electoral support and when the share of core voters in the remaining electorate is high. In line with Schelling's (Reference Schelling1960) ‘paradox of weakness’, such a party's bargaining position is strong in the sense that its core supporters are the least forgiving and the party leadership is bound by these supporters’ policy preferences (for a similar argument, see Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Debus and Gross2017).

It is unclear whether the party leadership is aware of and responsive to the preferences of its supporters. The vast majority of studies on government formation have ignored party supporters as distinct factors that might affect the bargaining process. Rather, these studies have explained the party composition of coalition governments based on factors such as the coalition's majority status, ideological homogeneity and incumbency and the broader institutional environment (e.g., Martin & Stevenson Reference Martin and Stevenson2001; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Martin and Thies2005; Döring & Hellström Reference Döring and Hellström2013; Klüver & Bäck Reference Klüver and Bäck2019). A noteworthy exception is Debus and Müller (Reference Debus and Müller2013), who have shown that voters’ coalition preferences affect the party composition of future governments. Accounting for other coalition characteristics such as a coalition's majority status and ideological proximity, Debus and Müller (Reference Debus and Müller2013) demonstrate that party leaders are more likely to form coalition governments that have more support among their party supporters.

Nevertheless, much of this leader‐supporter linkage remains unclear. It is uncertain how party leaders obtain information about their supporters’ preferences: they may respond to heuristics and beliefs about their supporters’ preferences, or act based on direct feedback from within or outside the party. Moreover, it is unclear whether party leaders’ perceptions of supporters’ preferences are actually accurate. For example, the public opinion backlash against the Liberal Democrats after their broken promise to vote against any increase in university tuition fees in the United Kingdom in 2010 indicates that party leaders might have been ill‐informed about their voters’ preferences (Butler Reference Butler2020). While the present study has shed light on voters’ expectations of coalition bargaining, we hope future research will narrow this gap by analyzing party elites’ perceptions of their supporters’ preferences during the government formation process.

We also need a better understanding of the breaking point after which supporters punish their parties for compromising as well as what party supporters care about the most. Following part of the existing literature (e.g., Debus & Müller Reference Debus and Müller2014), our paper has focused on policies and policy payoffs during coalition talks, but it is possible for voters to additionally care (or even more so) about other bargaining outcomes, such as portfolio allocation (see Greene et al. Reference Greene, Henceroth and Jensen2020). Given the central role of ministerial portfolios, if voters understand specific party responsibilities within the coalition – and there is some evidence that they do (Duch et al. Reference Duch, Przepiorka and Stevenson2015) – voters should want their party to gain control of more salient portfolios. Vignette experiments may come in useful in this regard to disentangle the importance of policies from that of portfolios.

In sum, we have shown that party supporters vary systematically in terms of their willingness to compromise, a key aspect of pluralist democracies and an often‐necessary step of government formation in multi‐party systems.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the internal seminar series at the Department of Government, University of Vienna 2019. We would like to thank all the participants for their useful comments. We would also like to thank Theres Matthieß, Christina Gahn, and Werner Krause for their useful feedback on previous versions of this paper. Alejandro Ecker gratefully acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project number 418728321.

Funding

Data collection for this project has been sponsored by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (T997‐G27).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Material