1. Introduction

Magnesium is a macronutrient absorbed by plants in its ionic form Mg2+, playing fundamental physiological roles in plants and all other living organisms. It is the eighth most abundant element on Earth and the most abundant divalent cation in all living cells (Culkin & Cox, Reference Culkin and Cox1966; Fleischer, Reference Fleischer1954; Maguire & Cowan, Reference Maguire and Cowan2002; Senbayram et al., Reference Senbayram, Gransee, Wahle and Thiel2015). Today, Mg2+ deficiency in soils is an increasingly worrying problem, which limits crop yields and affects human nutrition, as plants are our main source of Mg2+. For many years, this element has been under-investigated, therefore earning the name of the ‘forgotten element’ (Broadley & White, Reference Broadley and White2010; Cakmak & Yazici, Reference Cakmak and Yazici2010; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Zhao, Fairweather-Tait, Poulton, Dunham and McGrath2008; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Conn, Chen, Xiao and Verbruggen2013; Shaul, Reference Shaul2002). Up to 30% of adults in Europe and North America fail to meet the Estimated Average Requirement for Mg2+ (Rosanoff, Reference Rosanoff2013). More recent assessments confirmed chronic low dietary Mg2+ is widespread and linked to public health risks (Adomako & Yu, Reference Adomako and Yu2024; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Gong, Liu, Yu, Gao and Zhao2025). Symptoms of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.75 mmol/L) include extreme fatigue, muscle dysfunction, more risk of cardiovascular disease, arrhythmia, cardiac death, insulin resistance and hypertension (Rosanoff, Reference Rosanoff2013; Al Alawi et al., Reference Al Alawi, Majoni and Falhammar2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Gong, Liu, Yu, Gao and Zhao2025).

In this review, we briefly outline the main physiological and biochemical roles of Mg2+ and we provide an overview of the key components involved in Mg2+ transport and homeostasis. In addition, we examine how Mg2+ homeostasis intersects with broader cellular signalling networks and metabolic processes. Of particular interest are the interactions between Mg2+ homeostasis and circadian clocks, raising important questions about how temporal control mechanisms influence nutrient fluxes and how Mg2+ dynamics, in turn, feed back into the circadian clock. By coordinating key physiological processes that influence crop yield and resource efficiency, the circadian clock holds great potential for ‘chronoculture’, an approach to agriculture that harnesses biological timing to optimize practices, such as applying nutrients at the time of day when they are most effective (Gerhardt & Mehta, Reference Gerhardt and Mehta2025; Ogasawara et al., Reference Ogasawara, Hotta and Dodd2025; Steed et al., Reference Steed, Ramirez, Hannah and Webb2021).

2. Main physiological and biochemical roles of Mg 2+ and symptoms of deficiency

The physiological importance of Mg2+ has been most extensively characterized in the context of photosynthesis. As the central atom of chlorophyll, Mg2+ directly participates in light capture. It also stabilizes pigment-protein complexes in Photosystems I and II and contributes to the maintenance of thylakoid membrane architecture. Because thylakoid membranes carry a negative surface charge, Mg2+ plays a crucial role in counteracting these charges, promoting the appression of adjacent membranes and ultimately driving grana stacking. When Mg2+ becomes limiting, electrostatic repulsion increases and grana becomes unstacked or disorganized. As a result, chlorophyll content is reduced and interveinal chlorosis develops, predominantly in older mature leaves, accompanied by a decrease in photosynthetic rate (Cakmak & Yazici, Reference Cakmak and Yazici2010; Levitt, Reference Levitt1954; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012; Pandey, Reference Pandey, Hasanuzzaman, Fujita, Oku, Nahar and Hawrylak-Nowak2018). Notably, however, chlorosis is a late symptom of Mg2+ shortage (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004; Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Hermans, Ichihashi, Shibata, Shirasu, Aoki, Sugita, Ogawa, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2020)

Beyond photosynthesis, Mg2+ is essential for ribosome biogenesis and translation. It stabilizes ribosomal subunits and facilitates the binding of messenger RNA (mRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA) (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Moore and Steitz2004; Kobayashi & Tanoi, Reference Kobayashi and Tanoi2015; Sperrazza & Spremulli, Reference Sperrazza and Spremulli1983). When Mg2+ is deficient, these processes are impaired, leading to reduced protein synthesis (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021; Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016). This effect is especially pronounced in chloroplasts, which house more than 25% of total cellular proteins (Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Qi, Lee, Yang, Guo, Jiang and Chen2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Peng, Li and Liao2018).

In addition to its function in translation, Mg2+ serves as an essential cofactor and allosteric modulator for more than 300 enzymes involved in respiration, glycolysis, nucleic acid metabolism, chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthetic carbon fixation (De Bang et al., Reference De Bang, Husted, Laursen, Persson and Schjoerring2021; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Conn, Chen, Xiao and Verbruggen2013). Key examples include ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase, underscoring the central role of Mg2+ in carbon assimilation (Andreo et al., Reference Andreo, Gonzalez and Iglesias1987; Lorimer et al., Reference Lorimer, Badger and Andrews1976; Walker & Weinstein, Reference Walker and Weinstein1994; Willows, Reference Willows2003). Mg2+ is also indispensable for energy metabolism as the binding partner of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Between 50% and 90% of cytosolic Mg2+ is complexed with ATP, and Mg2+ scarcity impairs Mg-ATP formation, thereby compromising energy-dependent reactions across metabolic pathways (Maguire & Cowan, Reference Maguire and Cowan2002; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012; Shaul, Reference Shaul2002). Moreover, ATP synthesis itself is highly dependent on Mg2+, since ATP synthase requires Mg2+ as a cofactor to catalyse the phosphorylation of ADP (Gout et al., Reference Gout, Rébeillé, Douce and Bligny2014; Lin & Nobel, Reference Lin and Nobel1971).

A key outcome of Mg2+ deficiency is impaired phloem loading. Reduced activity of H+-ATPases in phloem companion cells compromises the proton motive force and restricts sucrose export from source to sink tissues in species relying on apoplastic loading of photoassimilates (Bush, Reference Bush1989; Cakmak & Yazici, Reference Cakmak and Yazici2010; Vaughn et al., Reference Vaughn, Harrington and Bush2002). Experimentally, Mg2+ deficiency has been shown to induce carbohydrate accumulation in source leaves, increase the shoot-to-root dry weight ratio (Cakmak et al., Reference Cakmak, Hengeler and Marschner1994; Cakmak & Kirkby, Reference Cakmak and Kirkby2008; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004), repress photosynthetic gene expression and further reduce the activities of CO2-assimilating and photosynthetic enzymes (Cakmak & Kirkby, Reference Cakmak and Kirkby2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Peng, Li and Liao2018).

At the structural level, prolonged Mg2+ deficiency leads to swelling and disorganization of chloroplasts, as well as damage to the photosynthetic electron transport chain (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004; Laing et al., Reference Laing, Greer, Sun, Beets, Lowe and Payn2000). These alterations promote overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Cakmak, Reference Cakmak1994; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Nazim, Liang and Yang2016), which in turn exacerbate disturbances in source-sink dynamics, growth and biomass allocation (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004, Reference Hermans, Conn, Chen, Xiao and Verbruggen2013; Kobayashi & Tanoi, Reference Kobayashi and Tanoi2015; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Qi, Lee, Yang, Guo, Jiang and Chen2015; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Winkelmann, Hasler, Pawelzik and Naumann2020). High-light environments amplify these detrimental effects by accelerating photooxidative stress and further enhancing ROS production (Cakmak & Kirkby, Reference Cakmak and Kirkby2008; Kumar Tewari et al., Reference Kumar Tewari, Kumar and Nand Sharma2006; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Gao, Xu, Li, Ren, Li, Cong, Lu, Cakmak and Lu2024).

The distribution of Mg2+ within leaves also reflects its nutritional status. Depending on Mg2+ availability, up to 35% of total leaf Mg2+ is found in chloroplasts, with up to 25% associated to chlorophyll; this percentage is increased by Mg2+ deficiency or low-light conditions (Broadley & White, Reference Broadley and White2010; Cakmak & Yazici, Reference Cakmak and Yazici2010; Dorenstouter et al., Reference Dorenstouter, Pieters and Findenegg1985; Scott & Robson, Reference Scott and Robson1990). The remainder is distributed among the vacuole (the main storage site), the cell wall and the water-soluble cytoplasmic pool (Leigh & Wyn Jones, Reference Leigh and Wyn Jones1986; Maguire & Cowan, Reference Maguire and Cowan2002; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012). The vacuole’s strong Mg2+ retention capacity limits both deficiency and toxicity (Shaul, Reference Shaul2002; Stelzer et al., Reference Stelzer, Lehmann, Kramer and Lüttge1990).

Finally, accumulating evidence indicates that Mg2+ supplementation can enhance plant resistance to both abiotic stresses, such as high light, cold, drought and heat, and biotic stresses, including fungal and bacterial infections (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Li, Gao, Sun, Hu, Ullah, Gao, Li, Liu, Jiang, Cao, Tian and Dai2021; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Leibman-Markus, Anand, Rav-David, Yermiyahu, Elad and Bar2022; Li et al., Reference Li, Muneer, Sun, Guo, Wang, Huang, Li and Zheng2023). For example, Mg2+ oxide (MgO) application in tomato induces immunity against Fusarium wilt by activating the jasmonic acid signalling pathway (Fujikawa et al., Reference Fujikawa, Takehara, Ota, Imada, Sasaki, Kajihara, Sakai, Jogaiah and Ito2021), and overall Mg2+ fertilization can improve crop yield (Wang, Hassan, et al., Reference Wang, Hassan, Nadeem, Wu, Zhang and Li2020). Consequently, Mg2+ deficiency not only disrupts photosynthesis and carbohydrate allocation but also alters broader nutrient homeostasis (see Section 3), plant stress responses and immunity, thereby reinforcing a feedback loop of physiological decline. Understanding these interdependencies is therefore critical for optimizing fertilization strategies, particularly in soils with variable pH, texture and ionic composition.

3. Magnesium availability in soils and interactions with other nutrients

In soils, adequate Mg2+ concentrations range between 0.12 and 8.5 mM to sustain optimal plant growth (Karley & White, Reference Karley and White2009; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012). Levels outside this range can cause deficiency or toxicity, both of which impair photosynthesis, carbohydrate partitioning and biomass accumulation (Farhat et al., Reference Farhat, Elkhouni, Zorrig, Smaoui, Abdelly and Rabhi2016; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Nazim, Liang and Yang2016). Therefore, understanding the geochemical, physiological and competitive factors regulating Mg2+ availability is critical to improve yield in agricultural systems. Importantly, soil and plant Mg2+ concentrations are shaped by numerous chemical, mineralogical and environmental factors (Senbayram et al., Reference Senbayram, Gransee, Wahle and Thiel2015).

A major determinant of soil Mg2+ concentration is the mineral composition and degree of weathering. Primary silicates like olivine and augite contain more Mg2+ than highly weathered minerals such as muscovite (Guo, Reference Guo, Hossain, Kamiya, Burritt, Tran and Fujiwara2017; Maguire & Cowan, Reference Maguire and Cowan2002; Mayland & Wilkinson, Reference Mayland and Wilkinson1989). In addition, due to its large hydrated ionic radius and low binding affinity for negatively charged soil colloids, Mg2+ is highly mobile and easily leached, particularly in sandy or acidic soils (Guo, Reference Guo, Hossain, Kamiya, Burritt, Tran and Fujiwara2017; Maguire & Cowan, Reference Maguire and Cowan2002). Acidic soils, which represent nearly 70% of global arable land, often have low cation exchange capacity, limiting Mg2+ retention. This problem is exacerbated under high rainfall or irrigation, further increasing the risk of Mg2+ deficiency (Aitken et al., Reference Aitken, Dickson, Hailes and Moody1999; Mengel et al., Reference Mengel, Kirkby, Kosegarten and Appel2001; Senbayram et al., Reference Senbayram, Gransee, Wahle and Thiel2015).

However, Mg2+ availability is not determined solely by its absolute concentration but also by its interactions with other ions in the rhizosphere and plant tissues. Such interactions can influence uptake, transport or utilization through precipitation, complexation or competition for binding and transport sites (Epstein & Bloom, Reference Epstein and Bloom1972; Fageria, Reference Fageria2001; Marschner & Marschner, Reference Marschner and Marschner2012). For instance, Mg2+ forms insoluble Mg2+ carbonate (MgCO3) in alkaline or calcareous soils (Broadley & White, Reference Broadley and White2010) and often competes with cations of similar properties, including Ca2+, K+, Na+ and NH4 +, to maintain electrochemical and osmotic balance (Gransee & Führs, Reference Gransee and Führs2013; Lasa et al., Reference Lasa, Frechilla, Aleu, González-Moro, Lamsfus and Aparicio-Tejo2000; Peuke et al., Reference Peuke, Jeschke and Hartung2002). This mutual antagonism is especially relevant in the context of modern agriculture, where unbalanced use of nitrogen–phosphorus–potassium (NPK) fertilizers contributes to progressive Mg2+ depletion in soils (Cakmak & Yazici, Reference Cakmak and Yazici2010; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Conn, Chen, Xiao and Verbruggen2013; Kobayashi & Tanoi, Reference Kobayashi and Tanoi2015).

Mg2+ interactions with other ions can also be synergistic, enhancing physiological functions or antagonistic, where excess of one ion inhibits the uptake of others. The effects depend on soil properties, nutrient ratios, plant species, plant tissues, developmental stage and environmental conditions (Chaudhry et al., Reference Chaudhry, Nayab, Hussain, Ali and Pan2021; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Conn, Chen, Xiao and Verbruggen2013). At low to moderate concentrations, Mg2+ uptake shows synergistic or neutral interactions with Ca2+ and K+ but becomes antagonistic when Ca2+ or K+ are present in excess. Under Mg2+ limitation, antagonism is usually observed, although findings for K+ remain inconsistent (Heenan & Campbell, Reference Heenan and Campbell1981; Fageria, Reference Fageria1983; Lasa et al., Reference Lasa, Frechilla, Aleu, González-Moro, Lamsfus and Aparicio-Tejo2000; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Luo and Xu2006; Tang & Luan, Reference Tang and Luan2017; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Miles and Hughes2018; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Cakmak, Wang, Zhang and Guo2021; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Crusciol, Rosolem, Bossolani, Nascimento, McCray, Reis and Cakmak2022). Interactions with micronutrients such as Mn2+, Zn2+, Fe2+ and Cu2+ are context-dependent: high concentrations of these metals can inhibit Mg2+ uptake, whereas Mg2+ deficiency may induce their accumulation or have little effect (Heenan & Campbell, Reference Heenan and Campbell1981; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Bhatia and Shukla1981; Agarwala et al., Reference Agarwala, Chatterjee, Gupta and Nautiyal1988; Le Bot et al., Reference Le Bot, Goss, Carvalho, Van Beusichem and Kirkby1990; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liang, Lakshmanan, Guan, Liu and Chen2021; Sadeghi et al., Reference Sadeghi, Rezeizad and Rahimi2021; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Liu, Gu, Zhan, Li, Zhou, Zhang and Zou2024). Mg2+ generally supports P acquisition, while deficiency reduces or has little impact on tissue P content (Fageria, Reference Fageria1983; Skinner & Matthews, Reference Skinner and Matthews1990; Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Hermans, Ichihashi, Shibata, Shirasu, Aoki, Sugita, Ogawa, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2020; Weih et al., Reference Weih, Liu, Colombi, Keller, Jäck, Vallenback and Westerbergh2021). The form of N also affects Mg2+ uptake: NH4 + tends to inhibit it, whereas NO3 − promotes acquisition. Conversely, Mg2+ fertilization can enhance NO3 − uptake by upregulating nitrate transporter genes such as NRT2.1 and NRT2.2 (Mayland & Wilkinson, Reference Mayland and Wilkinson1989; Lasa et al., Reference Lasa, Frechilla, Aleu, González-Moro, Lamsfus and Aparicio-Tejo2000; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Qi, Nie, Xiao, Liao and Chen2020; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Liu, Xu, Xing, Liu, Lyu, Feng, Zhang, Qin, Jiang, Zhu, Jiang and Ge2023). Finally, Mg2+ often mitigates toxic ions such as Al3+, Cd2+, Na+ and Li+, exerting protective effects by competing for transporters, stabilizing membranes, promoting organic acid exudation and maintaining cytoplasmic pH or metal homeostasis. For example, the overexpression of Mg2+ transporters genes (AtMGT1 and OsMGT1) increases cytosolic Mg2+ and enhances tolerance to Al3+ stress (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Luo, Li, Zheng, Wei, Smith, Thammina, Lu, Li and Pei2006; de Wit et al., Reference de Wit, Eldhuset and Mulder2010; Chou et al., Reference Chou, Chao, Huang, Hong and Kao2011; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Chen, Coppens, Inzé and Verbruggen2011; Rengel et al., Reference Rengel, Bose, Chen and Tripathi2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yamaji, Horie, Che, Li, An and Ma2017; Lyu et al., Reference Lyu, Liu, Xu, Liu, Qin, Zhang, Tian, Jiang, Jiang, Zhu and Ge2023; Garcia-Daga et al., Reference Garcia-Daga, Fischer and Gilliham2025).

Taken together, the multiple cellular roles of Mg2+ emphasize the need for strict control of its concentration and distribution within plant tissues and organelles. These functional requirements have driven the evolution of specialized transport systems and regulatory networks that ensure Mg2+ homeostasis.

4. Magnesium transport systems in plants

While Mg2+ concentration in plants is estimated at 25 mM, most of it is tightly bound to nucleotides, ribosomes, chlorophyll or stored in vacuoles, making only a small fraction (0.2–5 mM) available for metabolism. This free Mg2+ pool is dynamically regulated by Mg2+ transporters and the binding of Mg2+ to nucleotides involved in cellular reactions (Kleczkowski & Igamberdiev, Reference Kleczkowski and Igamberdiev2021, Reference Kleczkowski and Igamberdiev2023).

Mg2+ transport in plants involves coordinated uptake, long-distance translocation and intracellular partitioning, ensuring proper allocation across tissues and organelles. The core Mg2+ transport system in higher plants is formed by the Mitochondrial RNA Splicing 2 (MRS2)/Mg2+ transporter (MGT) family, the Mg2+/H+ exchanger (MHX) and members of the Magnesium release (MGR)/Cyclin M (CNNM)/Cation Outward Rectifier C (CorC) family, which are more recently identified key players of Mg2+ transport. Additional systems like cyclic nucleotide–gated ion channels (CNGCs) contribute in specific contexts.

4.1 Uptake from soil and transport in the root

Mg2+ uptake begins at the root–soil interface, where Mg2+ is absorbed predominantly as a free ion. Transport across the plasma membrane of root epidermal cells, particularly root hairs, is mediated mainly by members of the MRS2/MGT family. This family comprises three subfamilies, the CorA-like (CorA is the name of the family in prokaryotes because of mutants exhibiting Co2+ resistance), the Nonimprinted in Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome (NIPA), and the membrane Mg2+ transporters (MMgT), based on conserved-motifs distribution. The major group of Mg2+ transporters in plants is characterized by CorA-like domains and is named MRS2/MGT, while the physiological roles of NIPA and MMgT homologs in plants remain to be experimentally validated (Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Akhtar, Aleem, Aleem, Razzaq, Alamri, Raza, Sharif, Iftikhar, Naseer, Ahmed, Rana, Arshad, Khan, Bhat, Aleem, Gaafar and Hodhod2025; Mohamadi et al., Reference Mohamadi, Babaeian Jelodar, Bagheri, Nematzadeh and Hashemipetroudi2023). MRS2/CorA are homopentameric channels with two transmembrane (TM) helices in each monomer. They are characterized by a conserved Gly-X-Asn (GxN) motif, of which the X represents hydrophobic amino acids Met, Val or Ile, that forms part of the ion-conducting pore and is critical for Mg2+ selectivity and transport activity (Moomaw & Maguire, Reference Moomaw and Maguire2008; Ishijima et al., Reference Ishijima, Shiomi and Sagami2021; Franken et al., Reference Franken, Huynen, Martínez-Cruz, Bindels and De Baaij2022; Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Wallerstein, Villones, Huang, Lindkvist-Petersson, Meloni, Lu, Steen Jensen, Liin and Gourdon2025). MGT/MRS2 transporters are functionally conserved across plant species, and members have been identified among others in Arabidopsis, rice, wheat, maize, tomato and cucumber, highlighting both conservation and diversification of roles in Mg2+ homeostasis. These transporters exhibit varying affinities and selectivities, enabling plants to efficiently absorb Mg2+ across a wide range of external concentrations.

In Arabidopsis, MRS2-4/MGT6, which localizes to the plasma membrane of root hairs, functions as a major high-affinity Mg2+ uptake system under Mg2+ limitation (Mao et al., Reference Mao, Chen, Tian, Liu, Yang, Tang, Li, Lu, Yang, Shi, Chen, Li and Luan2014; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Yan, Mao, Yuan, Wang, Zhao and Luan2022; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Mao, Yang, Qi, Zhang, Tang, Li, Tang and Luan2018). Loss-of-function mgt6 mutants exhibit strong growth defects and chlorosis under low Mg2+, while overexpression enhances Mg2+ uptake capacity, confirming its central role in root Mg2+ acquisition. MRS2-7/MGT7, localized in the endomembrane system of root cells, is proposed to contribute to intracellular Mg2+ partitioning and homeostasis (Gebert et al., Reference Gebert, Meschenmoser, Svidová, Weghuber, Schweyen, Eifler, Lenz, Weyand and Knoop2010). Combined loss of MGT6 and MGT7 led to exacerbated phenotype compared with single mutants under both Mg2+-deficient and Mg2+-excess conditions (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Mao, Yang, Qi, Zhang, Tang, Li, Tang and Luan2018). In rice, the orthologue of AtMGT6, OsMGT1, has been demonstrated to mediate root Mg2+ uptake: knockout plants display decreased root Mg2+ uptake, lower tissue Mg2+ content and reduced biomass under Mg2+ deficiency, whereas overexpression increases Mg2+ under low Mg2+ supply (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yamaji, Motoyama, Nagamura and Ma2012; Zhang, Peng, et al., Reference Zhang, Peng, Li, Tian and Chen2019). Orthologous genes have also been identified in tomato (SlMGTs; Regon et al., Reference Regon, Chowra, Awasthi, Borgohain and Panda2019; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Khan, Tong, Hu, Yin and Huang2023), though their functional roles remain less well characterized.

A novel functional gene, LOC_Os03g04360, annotated as a putative inorganic phosphate transporter belonging to the OsPHT1 gene family, controlling Mg2+ uptake and translocation in rice was identified using QTL analysis (Zhi et al., Reference Zhi, Zou, Li, Meng, Liu, Chen and Ye2023). Overexpression of LOC_Os03g04360 could significantly increase the Mg2+concentration in rice seedlings, especially under the condition of low Mg2+ supply, but it decreased Mg content ratio of shoot to root.

Once absorbed, Mg2+ is transported to different tissues in the roots through the apoplastic and symplastic pathways.

4.2. Loading into and transport via the Xylem and Phloem

After entering root cells, Mg2+ must be loaded into the xylem for delivery to aerial tissues. In Arabidopsis, four plasma membrane-localized transporters, MGR4-MGR7, are essential for root-to-shoot Mg2+ allocation by mediating its release into the xylem (Meng, Zhang, Tang, et al., Reference Meng, Zhang, Tang, Zheng, Chen, Liu, Jing, Ge, Zhang, Chu, Fu, Zhao, Luan and Lan2022).

Additional evidence implicates the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 10 (CNGC10). CNGC proteins are non-specific ligand-gated Ca2+-permeable channels (Talke et al., Reference Talke, Blaudez, Maathuis and Sanders2003). Suppression of AtCNGC10 resulted in altered shoot ion profiles, with decreased Ca2+ and Mg2+ but elevated K+, suggesting that this channel contributes to long-distance cation transport, potentially through roles in xylem loading/retrieval and/or phloem loading (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Babourina, Christopher, Borsic and Rengel2010). AtCNGC10 is more highly expressed in roots than in leaves (Christopher et al., Reference Christopher, Borsics, Yuen, Ullmer, Andème-Ondzighi, Andres, Kang and Staehelin2007), the channel is in the plasma membrane, but its precise tissue localization and specific transport function remain unresolved today.

Beyond xylem transport, the phloem plays a central role in redistributing Mg2+ between source and sink tissues, particularly during deficiency or senescence. Because Mg2+ is phloem-mobile, deficiency symptoms characteristically develop first in mature fully expanded leaves, rather than in young leaves (De Bang et al., Reference De Bang, Husted, Laursen, Persson and Schjoerring2021; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004; Hermans & Verbruggen, Reference Hermans and Verbruggen2005; Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Hermans, Ichihashi, Shibata, Shirasu, Aoki, Sugita, Ogawa, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2020).

4.3. Subcellular transport

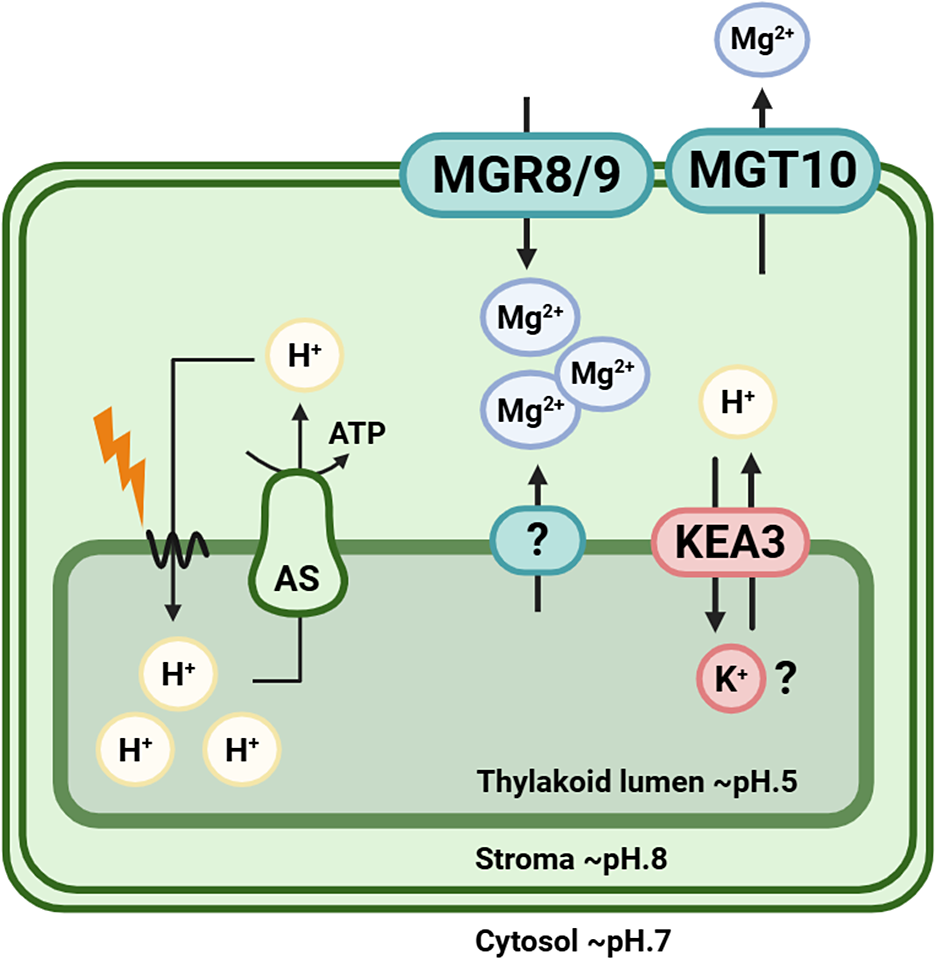

Mg2+ is vital at the subcellular level, and its transport has been especially studied in chloroplasts where it is the central atom of chlorophyll and participates in photosynthetic enzyme function and thylakoid stacking. Internal Mg2+ concentration can be measured by using an Mg2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator, mag-fura-2. Upon illumination, release of Mg2+ from thylakoid membranes has been observed in intact chloroplasts, and Mg2+ concentration typically increases from 0.5 mM to 2.0 mM in the stroma (Ishijima et al., Reference Ishijima, Uchibori, Takagi, Maki and Ohnishi2003). Stromal ion homeostasis depends on the activity of both thylakoid and envelope ion channels. While the identity of the Mg2+ transport system across the thylakoid membrane is unknown, transport across chloroplast inner envelope is mediated by AtMRS2-11/AtMGT10 in Arabidopsis (with OsMGT3 as its orthologue in rice) and the MGR family members MGR8 and MGR9 (ACDP/CNNM/CorC-related) (Figure 1). These three transporters have different roles, as evidenced by distinct phenotypes of their respective mutants (Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, Van Maldegem, Shaikh, Fukuda, Töpel, Solymosi, Hellsten, Hansen, Husted, Higgins, Sano, Ishijima and Spetea2023). For instance, thylakoid stacking is disrupted in mgt10 mutants but remains largely unaffected in mgr8 or mgr9. Conversely, grana size is reduced in the mgr8 mgr9 double mutant (Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, Van Maldegem, Shaikh, Fukuda, Töpel, Solymosi, Hellsten, Hansen, Husted, Higgins, Sano, Ishijima and Spetea2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang, Tang, Zheng, Zhao, Fu, Lan and Luan2022) but increased in mgt10 plastids (Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, Van Maldegem, Shaikh, Fukuda, Töpel, Solymosi, Hellsten, Hansen, Husted, Higgins, Sano, Ishijima and Spetea2023; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Yang, Li and Huang2017). In Arabidopsis, AtMRS2-11/MGT10 has been shown to mediate Mg2+ export from chloroplasts using dye-based Mg2+ imaging, whereas MGR8 and MGR9 are responsible for Mg2+ import into the stroma (Ishijima et al., Reference Ishijima, Shiomi and Sagami2021; Kunz et al., Reference Kunz, Armbruster, Mühlbauer, De Vries and Davis2024). In addition to these envelope transporters, the thylakoid cation/H+ antiporter KEA3 may also contribute to Mg2+ movements within the chloroplast. KEA3 exports protons from the lumen in exchange for another cation, most likely K+, yet transport of Mg2+ cannot be excluded (Uflewski et al., Reference Uflewski, Mielke, Correa Galvis, Von Bismarck, Chen, Tietz, Ruß, Luzarowski, Sokolowska, Skirycz, Eirich, Finkemeier, Schöttler and Armbruster2021).

Figure 1. Schematic overview of chloroplastic Mg2+ flux under illumination in Arabidopsis.

Upon illumination, photosynthetic electron transport drives proton pumping from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen, generating a steep trans-membrane proton gradient (lumen ~ pH 5; stroma ~ pH 8). This proton motive force powers ATP synthase (AS), which restores H+ to the stroma while producing ATP. Lightning symbol indicates light-driven reactions of the photosynthetic electron transport chain. The resulting stromal alkalinization triggers Mg2+ release from the thylakoid lumen into the stroma, thereby increasing stromal Mg2+ concentration. At the chloroplast inner envelope, Mg2+ import from the cytosol into the stroma is mediated by transporter proteins MGR8 and MGR9, supporting Mg2+ requirements for ATP stabilization, enzyme activation, chlorophyll-binding protein function and other chloroplastic-related functions. The AtMGT10/OsMGT3 channel is likely responsible for Mg2+ efflux or exchange across the inner envelope, maintaining charge balance during light-dependent H+ movements. After a sudden light decrease, KEA3-driven H+ export from the lumen to the stroma in exchange for another cation, most likely K+, is required for the prompt relaxation of non-photochemical quenching. Since the substrate of KEA3 has not been demonstrated in plants, transport of Mg2+ via the antiporter KEA3 cannot be excluded (Uflewski et al., Reference Uflewski, Mielke, Correa Galvis, Von Bismarck, Chen, Tietz, Ruß, Luzarowski, Sokolowska, Skirycz, Eirich, Finkemeier, Schöttler and Armbruster2021) (figure created with BioRender.com).

Vacuolar sequestration of Mg2+ is another important aspect of intracellular Mg2+ partitioning. The MHX transporter, a vacuolar metal/H+ exchanger, contributes mainly to detoxification and buffering of excess Mg2+, along with other divalent cations such as Zn2+ and Cd2+ (Shaul, Reference Shaul2002). Conn et al. (Reference Conn, Conn, Tyerman, Kaiser, Leigh and Gilliham2011) suggested that MGT2/MRS2-1 and MGT3/MRS2-5 might contribute to vacuolar accumulation of Mg2+ in the mesophyll cells, especially under serpentine conditions (high Mg2+/Ca2+ ratio in the soil) (Conn et al., Reference Conn, Conn, Tyerman, Kaiser, Leigh and Gilliham2011). However, subsequent work rather showed that MGT2 functions in Mg2+ efflux from the vacuole (as detailed below), whereas the tonoplast MGR1 mediates Mg2+ sequestration into the vacuole (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Yan, Mao, Yuan, Wang, Zhao and Luan2022).

The remobilization of Mg2+ from the vacuole to the cytoplasm is another key step in Mg2+ homeostasis. This process is mediated by MRS2-10/MGT1 and MRS2-1/MGT2 in Arabidopsis, two redundant vacuolar transporters (only the double mutant displays a phenotype) (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Yan, Mao, Yuan, Wang, Zhao and Luan2022). Note that AtMGT1 was initially mislocalized in the plasma membrane (Li et al., Reference Li, Tutone, Drummond, Gardner and Luan2001). Mg2+ efflux via MGT1 and MGT2 constitutes a rate-limiting step in Mg2+ remobilization from old leaves to young tissues such as seeds (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Yan, Mao, Yuan, Wang, Zhao and Luan2022).

5. Magnesium homeostasis signalling pathways

Magnesium homeostasis ensures that plants maintain an optimal internal Mg2+ concentration, supporting metabolic processes while preventing excessive accumulation that could become toxic. The main mechanisms contributing to Mg2+ homeostasis include regulated uptake by roots, controlled long-distance transport and tissue partitioning, dynamic storage and remobilization from intracellular compartments and signalling pathways that adjust transporter activity according to both internal and external Mg2+ status.

Regulation of Mg2+ transporters operates at multiple levels, including transcriptional control (Franken et al., Reference Franken, Huynen, Martínez-Cruz, Bindels and De Baaij2022). However, unlike other macro-nutrients, Mg2+ deficiency generally induces only limited transcriptional regulation of the Mg2+ transporter genes involved in root uptake (Gebert et al., Reference Gebert, Meschenmoser, Svidová, Weghuber, Schweyen, Eifler, Lenz, Weyand and Knoop2010; Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, Inzé and Verbruggen2010; Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Hermans, Ichihashi, Shibata, Shirasu, Aoki, Sugita, Ogawa, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2020). While Ogura et al. (Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2018) showed that Mg2+ uptake system was up-regulated in roots within 1 h in response to low Mg2+, this induction was not seen in mgt6 or mgt7 mutants, and the expression of AtMRS2-4/AtMGT6 and AtMRS2-7/AtMGT7 was not responsive to this condition (Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2018). In rice, OsMGT1 was only induced in shoots but not in roots under Mg2+ deficiency (Zhang, Peng, et al., Reference Zhang, Meng, Li, Zhou, Ma, Fu, Schwarzländer, Liu and Xiong2019). However, differences between species or experimental conditions may occur, as illustrated in tomato, where Mg2+ deficiency led to a clear transcriptional induction of several Mg2+ transporter genes (SlMGT1, SlMGT6, SlMGT7, and SlMGT10) in roots (Ishfaq et al., Reference Ishfaq, Zhong, Wang and Li2021). Overall, this suggests that Mg2+ uptake is primarily controlled by post-transcriptional or post-translational mechanisms or by changes in transporter activity and localization rather than gene induction.

A key regulation is by Mg2+ or Mg-ATP binding. CorA/MRS2/MGT channels constitute the major Mg2+ uptake system in plants and are believed to be regulated similarly as their prokaryotic ancestors. Electrophysiological, electronic paramagnetic resonance and molecular-dynamics studies of bacterial CorA show that cytoplasmic Mg2+ acts as a ligand gating the pentameric channel (Dalmas et al., Reference Dalmas, Sompornpisut, Bezanilla and Perozo2014). CorA crystal structures revealed that Mg2+ binds to both the central pore and the intracellular region rich in acidic residues. When intracellular Mg2+ is high (i.e., >5 mM), binding to sensor sites induces a closed conformation by increasing inter-subunit contacts. Conversely, when internal Mg2+ drops and unbinding occurs, the channel undergoes asymmetric domain rearrangement, opening to allow Mg2+ influx. In eukaryotic MRS2 (yeast or human), with resolved crystal structures, Mg2+-sensing sites have been confirmed (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Sponder, Sjöblom, Svidová, Schweyen, Carugo and Djinović-Carugo2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Wallerstein, Villones, Huang, Lindkvist-Petersson, Meloni, Lu, Steen Jensen, Liin and Gourdon2025). Plant homologs show structural similarity suggesting a comparable architecture, though direct functional gating studies (e.g., patch-clamp or conformational assays) are limited. Therefore, Mg2+ regulation is likely, but experimental confirmation in plants is less extensive than in bacteria or human mitochondria.

Members of the CNNM/CorC family (including plant MGR proteins) carry cytosolic CBS-pair domains that in other systems bind Mg-ATP and trigger conformational changes that regulate transporter activity. Structural and functional work on bacterial/archaeal CorB/CorC and on animal CNNMs supports Mg-ATP as a regulatory ligand. High-resolution structures (apo and Mg-ATP-bound) of archaeal CorB/CorC reveal an ATP-binding site in the cytosolic domain and conformational differences between ligand-free and Mg-ATP-bound states. Binding induces a conformational rearrangement of the CBS dimer, which is communicated to the transmembrane DUF21 domain and alters the transporter’s conductive or regulatory state (promoting or inhibiting Mg flux depending on the system). Functional assays indicate that Mg-ATP binding is important for Mg2+ transport/export activity in these proteins (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kozlov, Moeller, Rohaim, Fakih, Roux, Burke and Gehring2021). For plant MGRs, homology, domain architecture and physiological data strongly suggest similar regulation, but direct biochemical demonstration of Mg-ATP binding controlling plant MGR activity is absent in the peer-reviewed literature so far. MGRs have been mainly studied in Arabidopsis (9 members) and in wheat (15 members). In wheat, all 15 MGR genes contain conserved ABA-responsive elements in the promoter region (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhao, Liu, Zhao, Xu, Wang, Zong, Zhang, Ji, Ma, Zhao and Li2025) although direct regulation by ABA remains to be demonstrated. This observation is reminiscent of the clear overlap between Mg-deficiency-induced genes and ABA-responsive genes described by Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, et al. (Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, Harren, Inzé and Verbruggen2010).

Additional regulation derives from proton-motive forces that drive antiporters such as MHX and from crosstalk with Ca2+ signalling pathways that modulate transporter expression and ion channel activity. In Arabidopsis, tonoplast-localized Ca2+ sensors, CBL2 and CBL3, contribute to Mg2+ homeostasis via a V-ATPase-independent mechanism (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhao, Garcia, Kleist, Yang, Zhang and Luan2015). CBL2 and CBL3 recruit a set of four functionally redundant CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPK 3/9/23/26) to the tonoplast, establishing a CBL-CIPK signalling module that regulates vacuolar Mg2+ sequestration in response to elevated cytosolic Mg2+ (as seen in plants living on serpentine soils characterized by high Mg2+ content and low Ca2+/Mg2+ ratios). The targets at the tonoplast of CIPK3/9/23/26 remain unidentified. Since the mutants of MHX or MGT2/3 showed wild-type response to high Mg2+, those transporters are not involved in this CBL-CIPK regulation. Because tolerance to high Mg2+ was dependent on external Ca2+ (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhao, Garcia, Kleist, Yang, Zhang and Luan2015), Ródenas and Vert (Reference Ródenas and Vert2021) proposed that TPC1 (a slowly activated, non-selective, Ca2+-activated vacuolar channel) is the target of CBL2/3-CIPK3/9/23/26. In strong support, the activity of TPC1 is modulated by high Mg2+. In addition, the sucrose non-fermenting-1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) has recently been implicated in Arabidopsis high-Mg2+ response (Mohamadi et al., Reference Mohamadi, Babaeian Jelodar, Bagheri, Nematzadeh and Hashemipetroudi2023).

Genetic evidence reinforces the Mg2+-Ca2+ relationship: loss-of-function cax1 mutants, lacking a major vacuolar H+/Ca2+ antiporter, exhibit enhanced tolerance to serpentine soils, likely because reduced vacuolar Ca2+ sequestration increases cytosolic Ca2+ available to counteract excess Mg2+ (Bradshaw, Reference Bradshaw2005). Conversely, low external Ca2+ supply can partially rescue Mg2+-deficiency phenotypes in mutants lacking Mg2+ transporters (Lenz et al., Reference Lenz, Dombinov, Dreistein, Reinhard, Gebert and Knoop2013).

Besides, Mg2+ transporter activity can also be modulated by the ionic context of the environment. Mg2+ flux inside chloroplasts illustrates how Mg2+ transport operates within a broader ionic network (Figure 1). In illuminated chloroplasts, proton pumping into the thylakoid lumen during photosynthetic electron transport acidifies the lumen and generates a proton gradient between the stroma and the lumen. To maintain electrochemical balance, Mg2+ and other cations (e.g., K+) move from the lumen to the stroma, causing a rapid and reversible increase in free stromal Mg2+. This process is pH-dependent, as light-induced stromal alkalinization is required for Mg2+ release (Ishijima et al., Reference Ishijima, Uchibori, Takagi, Maki and Ohnishi2003). Because several chloroplast enzymes, including Rubisco, depend on Mg2+ for activation, this light-driven redistribution likely helps coordinate photosynthetic metabolism with light availability (Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, Van Maldegem, Shaikh, Fukuda, Töpel, Solymosi, Hellsten, Hansen, Husted, Higgins, Sano, Ishijima and Spetea2023). In addition, Mg2+ flux affects the ΔpH across the thylakoid membrane and contributes to the regulation of non-photochemical quenching (NPQ). Mg2+ influx into the stroma may lower stromal pH through reversible cation/H+ exchange across the chloroplast envelope (Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, Van Maldegem, Shaikh, Fukuda, Töpel, Solymosi, Hellsten, Hansen, Husted, Higgins, Sano, Ishijima and Spetea2023). KEA3-driven H+ export from the thylakoid is also critical for rapid NPQ relaxation after a sudden decrease in light, and a potential Mg2+ transport function of KEA3 would further link this process to stromal Mg2+ dynamics (Uflewski et al., Reference Uflewski, Mielke, Correa Galvis, Von Bismarck, Chen, Tietz, Ruß, Luzarowski, Sokolowska, Skirycz, Eirich, Finkemeier, Schöttler and Armbruster2021).

A main strategy to study regulation of mineral homeostasis is to expose plants to nutrient deficiency. Understanding how plants sense and signal Mg2+ deficiency remains challenging because stress signalling networks are inherently complex and often overlap with other physiological responses (Wilkins et al., Reference Wilkins, Matthus, Swarbreck and Davies2016). Transcriptomic analyses under Mg2+ starvation have identified numerous differentially expressed genes (DEGs), providing a global view of adaptive responses (Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, Inzé and Verbruggen2010; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Lin, Wu, Ye, Qu, Xie, Lin, Gao, Wang, Ke, Li, Guo, Lu, Tang, Chen and Li2024; Ogura et al., Reference Ogura, Kobayashi, Hermans, Ichihashi, Shibata, Shirasu, Aoki, Sugita, Ogawa, Suzuki, Iwata, Nakanishi and Tanoi2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhou, Wang, Wu, Ye, Guo and Chen2019). Although these DEGs do not directly reveal the molecular identity of Mg2+ sensors, they highlight early-responding candidates potentially involved in deficiency signalling. Mg2+ deficiency responses are spatially and temporally asynchronous, typically appearing first in roots before shoots (Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, Harren, Inzé and Verbruggen2010). Notably, Ca2+ has emerged as a likely secondary messenger in Mg2+ deficiency signalling. Several Ca2+ transporter genes are upregulated during Mg2+ starvation, and cytosolic Ca2+ levels increase, consistent with the known Mg2+-Ca2+ antagonism (Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, Inzé and Verbruggen2010; Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, Harren, Inzé and Verbruggen2010). Supporting this model, Wiesenberger et al. (Reference Wiesenberger, Steinleitner, Malli, Graier, Vormann, Schweyen and Stadler2007) showed in yeast that Mg2+ deficiency rapidly elevates cytosolic free Ca2+, triggering the activation of Ca2+-binding proteins (CaBPs), suggesting a central role for Ca2+ in mediating Mg2+-deficiency responses. Similar Ca2+-dependent mechanisms appear to operate under Mg2+ excess with the CBL-CIPK module (see above, Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhao, Garcia, Kleist, Yang, Zhang and Luan2015; Tang & Luan, Reference Tang and Luan2017).

Beyond indirect signalling effects, Mg2+ directly modulates the activity of several ion channels, highlighting its dual role as nutrient and signalling regulator. At the tonoplast, cytosolic Mg2+ activates slow vacuolar (SV) channels while inhibiting fast vacuolar (FV) channels, reducing K+ leakage and supporting ionic stability (Lemtiri-Chlieh et al., Reference Lemtiri-Chlieh, Arold and Gehring2020). Mg2+ also inhibits outward non-selective cation channels (NSCCs), such as MgC in guard and subsidiary cells of broad bean and maize, and participates in NH4 +/NH3 transport across the peribacteroid membrane in N2-fixing plants, often coordinated with Ca2+- signalling. At the plasma membrane, Mg2+ further regulates Ca2+ influx through hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels (HACCs), believed to correspond to cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs). Physiological concentrations of cytosolic Mg2+, mainly in the form of Mg–ATP, strongly inhibit HACC activity in guard cells at highly negative voltages (≤ −200 mV), via interaction with a conserved diacidic Mg2+-binding motif (Lemtiri-Chlieh et al., Reference Lemtiri-Chlieh, Arold and Gehring2020). Thus, Mg2+ not only competes with Ca2+ for permeation but also seems to fine-tune Ca2+-dependent signalling.

Taken together, these findings reveal a tight interplay between Mg2+ and Ca2+ homeostasis, potentially involving shared transporters, regulatory sites and signalling components, although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Beyond its effects on Mg2+-related pathways, Ca2+ appears to act as a general mediator of nutrient signalling, influencing plant responses to K+, NO3 −, B3+ and possibly PO4 3− (Behera et al., Reference Behera, Long, Schmitz-Thom, Wang, Zhang, Li, Steinhorst, Manishankar, Ren, Offenborn, Wu, Kudla and Wang2017; Matthus et al., Reference Matthus, Wilkins, Swarbreck, Doddrell, Doccula, Costa and Davies2019; Quiles-Pando et al., Reference Quiles-Pando, Navarro-Gochicoa, Herrera-Rodríguez, Camacho-Cristóbal, González-Fontes and Rexach2019; Wilkins et al., Reference Wilkins, Matthus, Swarbreck and Davies2016; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Chen, Wang, Liu, He and Wu2006).

Parallels can also be drawn with animal systems, where Mg2+ functions as a second messenger regulating diverse cellular processes. For example, Li et al. (Reference Li, Chaigne-Delalande, Kanellopoulou, Davis, Matthews, Douek, Cohen, Uzel, Su and Lenardo2011) showed that defective Mg2+ flux underlies human T-cell immunodeficiency, while Stangherlin and O’Neill (Reference Stangherlin and O’Neill2018) demonstrated that Mg2+ dynamics modulate signal transduction. Collectively, these studies support the emerging view that Mg2+, beyond its metabolic and structural roles, contributes to the fine-tuning of cellular signalling pathways in plants.

6. Interactions of magnesium with the circadian clock

Recent findings have revealed a dynamic role for Mg2+ as a temporal regulator in plants. Mg2+ appears to modulate the circadian clock, and reciprocally, the clock influences Mg2+ homeostasis.

6.1. Overview of the plant circadian clock

Plants possess endogenous circadian clocks that generate ~24-hour rhythms, aligning internal processes with daily and seasonal environmental cycles. In Arabidopsis, up to 40% of the transcriptome exhibit rhythmic expression under constant conditions, highlighting the broad regulatory role of the clock (Covington et al., Reference Covington, Maloof, Straume, Kay and Harmer2008; Rivière et al., Reference Rivière, Raskin, de Melo, Boutet, Corso, Defrance, Webb, Verbruggen and Anoman2024; Romanowski et al., Reference Romanowski, Schlaen, Perez-Santangelo, Mancini and Yanovsky2020; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Seki, Satake and Caldana2019). These rhythms can be described by a sine wave function defined by three parameters: amplitude (the difference between the mean and peak height of the rhythm), phase (a fixed point in the cycle, relative to the external light and dark cycle) and period (the duration between two fixed points in the cycle, e.g., successive peaks). The core circadian oscillator is governed by clock genes forming interconnected transcriptional and post-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) driving downstream rhythmic growth and physiological outputs. The central oscillator is entrained by external cues (= zeitgebers) such as light and temperature, as well as internal signals, including ions and metabolites (Hsu & Harmer, Reference Hsu and Harmer2014; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Seki, Satake and Caldana2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Steed and Webb2022). Key components of the central oscillator include morning-expressed genes CIRCADIAN CLOCK-ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) and LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY), morning-to-afternoon PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS (PRRs), PRR9, PRR7 and PRR5, which are expressed sequentially throughout the day, and evening-expressed genes such as TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 (TOC1/PRR1), the Evening Complex (EARLY FLOWERING 3 or ELF3, ELF4, and LUX ARRHYTHMO or LUX), as well as GIGANTEA (GI) and ZEITLUPE (ZTL) (Greenwood & Locke, Reference Greenwood and Locke2020; Hsu & Harmer, Reference Hsu and Harmer2014; McClung, Reference McClung2006).

Through these interconnected feedback loops, the circadian clock orchestrates key physiological processes, including stomatal opening and aquaporin activity, which regulate transpiration, the main driver of xylem nutrient transport, and photosynthesis, which produces sugars exported to the phloem to redistribute nutrients throughout the plant (Caldeira et al., Reference Caldeira, Jeanguenin, Chaumont and Tardieu2014; Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Salathia, Hall, Kévei, Tóth, Nagy, Hibberd, Millar and Webb2005; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Román and Arshad2015; Noordally et al., Reference Noordally, Ishii, Atkins, Wetherill, Kusakina, Walton, Kato, Azuma, Tanaka, Hanaoka and Dodd2013; Westgeest et al., Reference Westgeest, Dauzat, Simonneau and Pantin2023). These rhythmic sugars, in turn, feedback to entrain the clock, primarily via PRR7, a strong inhibitor of CCA1, which is repressed by photosynthetically derived sugars. Under low-energy conditions, exogenous sucrose shortens the circadian period in a PRR7-dependent manner, maintains oscillations in continuous darkness, and advances or delays clock phase depending on the timing of sugar application, whereas prr7 mutants are largely insensitive to these effects (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Thomson and McWatters2008; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Mielczarek, Robertson, Hubbard and Webb2013; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Carlsson, Takeuchi, Newton and Farré2013; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Matiolli, Viana, Hearn, Kusakina, Belbin, Wells Newman, Yochikawa, Cano-Ramirez, Chembath, Cragg-Barber, Haydon, Hotta, Vincentz, Webb and Dodd2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Steed and Webb2022). Notably, approximately 40% of sugar-responsive genes exhibit circadian rhythmicity (Bläsing et al., Reference Bläsing, Gibon, Günther, Höhne, Morcuende, Osuna, Thimm, Usadel, Scheible and Stitt2005).

6.2. Circadian regulation of ion homeostasis

Historically, circadian rhythms were hypothesized to arise from feedback loops involving ion gradients and membrane transporters (Nitabach et al., Reference Nitabach, Holmes, Blau and Young2005; Njus et al., Reference Njus, Sulzman and Hastings1974). While the gene-centric model now dominates in circadian research, ion fluxes remain a critical interacting layer, that both modulate and is modulated by transcriptional and non-transcriptional feedback loops (Henslee et al., Reference Henslee, Crosby, Kitcatt, Parry, Bernardini, Abdallat, Braun, Fatoyinbo, Harrison, Edgar, Hoettges, Reddy, Jabr, von Schantz, O’Neill and Labeed2017; Mihut et al., Reference Mihut, O’Neill, Partch and Crosby2025). Mineral nutrients are now attracting renewed interest for their ability to influence circadian timing and improve crop productivity through chronoculture (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Maywood and O’Neill2008; Ogasawara et al., Reference Ogasawara, Hotta and Dodd2025; Steed et al., Reference Steed, Ramirez, Hannah and Webb2021).

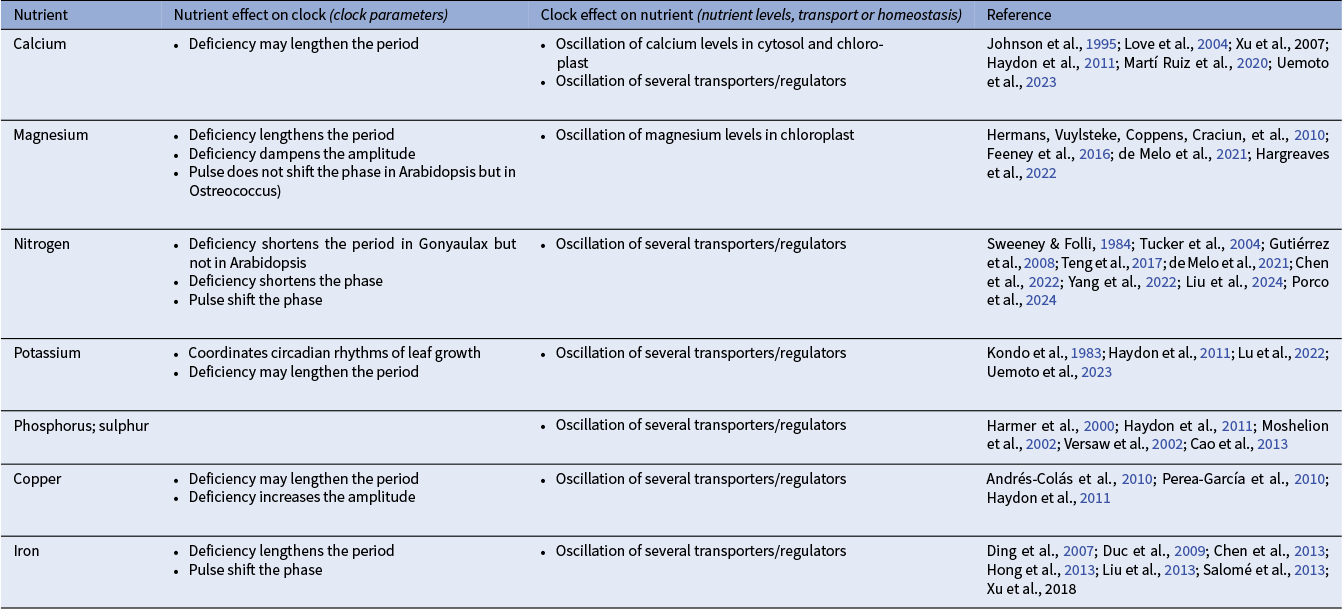

Nutrient availability can affect clock dynamics in diverse ways (Table 1). Nitrogen deficiency shortens the circadian period in the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polyedra (Sweeney & Folli, Reference Sweeney and Folli1984), and NO3 − pulses entrain circadian gene expression in Arabidopsis, where clock components regulate many nitrogen-responsive genes (Covington et al., Reference Covington, Maloof, Straume, Kay and Harmer2008; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Stokes, Thum, Xu, Obertello, Katari, Tanurdzic, Dean, Nero, McClung and Coruzzi2008; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Bell and Webb2011; Porco et al., Reference Porco, Yu, Liang, Snoeck, Hermans and Kay2024). Transcripts associated with transport and homeostasis of K+, PO4 3− and SO4 2− are also circadian regulated (Lebaudy et al., Reference Lebaudy, Vavasseur, Hosy, Dreyer, Leonhardt, Thibaud, Véry, Simonneau and Sentenac2008; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Bell and Webb2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shi, Ng, Battle, Zhang and Lu2011; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wang, Wirtz, Hell, Oliver and Xiang2013; Uemoto et al., Reference Uemoto, Mori, Yamauchi, Kubota, Takahashi, Egashira, Kunimoto, Araki, Takemiya, Ito and Endo2023). In Arabidopsis, cytosolic and chloroplastic Ca2+ display circadian oscillations, peaking between midday and dusk in mesophyll cells (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Knight, Kondo, Masson, Sedbrook, Haley and Trewavas1995; Love et al., Reference Love, Dodd and Webb2004; Martí Ruiz et al., Reference Martí Ruiz, Jung and Webb2020; Sai & Johnson, Reference Sai and Johnson2002). Although some Ca2+ channels and transporters exhibit rhythmic transcription, these oscillations are thought to be primarily driven by post-transcriptional regulation (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Gardner, Hotta, Hubbard, Dalchau, Love, Assie, Robertson, Jakobsen, Gonçalves, Sanders and Webb2007; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Bell and Webb2011, Reference Haydon, Román and Arshad2015).

Table 1 Interactions between nutrients and the plant circadian clock. Information is for Arabidopsis unless specified.

Among micronutrients, Cu2+ and Fe2+ transport and homeostasis are under circadian regulation (Duc et al., Reference Duc, Cellier, Lobréaux, Briat and Gaymard2009; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kim, Guerinot and McClung2013; Perea-García et al., Reference Perea-García, Andrés-Colás and Peñarrubia2010). Transcripts for Cu2+ transporters show circadian rhythms and their promoters contain conserved circadian elements (Covington et al., Reference Covington, Maloof, Straume, Kay and Harmer2008; Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Gardner, Hotta, Hubbard, Dalchau, Love, Assie, Robertson, Jakobsen, Gonçalves, Sanders and Webb2007; Perea-García et al., Reference Perea-García, Andrés-Colás and Peñarrubia2010). Excess Cu2+ reduces clock amplitude and may lengthen circadian period, likely through GI-dependent pathways (Andrés-ColÁs et al., Reference Andrés-ColÁs, Perea-García, Puig and Peñarrubia2010; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Bell and Webb2011).

Similarly, genes involved in Fe2+ transport and storage, including ferritin-encoding genes are regulated by both Fe2+ availability and circadian components such as PRR7 and TIME FOR COFFEE (TIC) (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Millar, Davis and Davis2007; Duc et al., Reference Duc, Cellier, Lobréaux, Briat and Gaymard2009; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Carlsson, Takeuchi, Newton and Farré2013). Fe2+ deficiency lengthens the circadian period by ~1–2 hours in a light-dependent manner, requiring evening components such as GI and ZTL, while morning components CCA1 and LHY directly regulate Fe2+ uptake genes (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang, Shin, Wu, Shanmugam, Tsednee, Lo, Chen, Wu and Yeh2013; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kim, Guerinot and McClung2013; Salomé et al., Reference Salomé, Oliva, Weigel and Krämer2013; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Jiang, Wang and Lin2019).

6.2.1. Magnesium oscillations and clock function

Magnesium is currently the nutrient with the most well-characterized connection to the circadian clock (Siqueira et al., Reference Siqueira, Zsögön, Fernie, Nunes-Nesi and Araújo2023). Oscillations in intracellular Mg2+ levels have been observed across multiple organisms, including the green unicellular alga Ostreococcus tauri, the fungus Neurospora crassa and human U2OS cells (Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016), as well as at the subcellular level in rice chloroplasts (Li et al., Reference Li, Yokosho, Liu, Cao, Yamaji, Zhu, Liao, Ma and Chen2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tian, Li, Bai, Zhang, Li, Cao and Chen2022). These oscillations influence global translational activity by modulating ATP stability and ribosomal function (de Barros Dantas et al., Reference de Barros Dantas, Eldridge, Dorling, Dekeya, Lynch and Dodd2023; Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016). Mg2+ rhythms peak around dusk in Ostreococcus but at dawn in rice chloroplasts, suggesting that Mg2+ regulation differs among species and subcellular compartments (Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016; Li et al., Reference Li, Yokosho, Liu, Cao, Yamaji, Zhu, Liao, Ma and Chen2020).

In cyanobacteria, Mg2+ directly modulates the KaiC-based oscillator, and artificial Mg2+ cycles can drive rhythmic gene expression even in the absence of core clock genes KaiA and KaiB, highlighting the importance of non-transcriptional circadian regulation (Rust et al., Reference Rust, Golden and O’Shea2011; Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Dias, Diekman, Brochon, Kim, Kaur, Kim, Jang and Kim2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Buckley and Haydon2022). Similarly, in Ostreococcus, intracellular Mg2+ rhythms persist without transcriptional activity in constant darkness, supporting post-translational control of Mg2+ transport and Mg2+ oscillations (Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016). These observations emphasize the importance of non-gene-centric mechanisms in circadian regulation.

In mammals, the Mg2+ transporter TRANSIENT RECEPTOR POTENTIAL CATION CHANNEL SUBFAMILY M MEMBER 7 (TRPM7) exhibits rhythmic expression that affects intracellular Mg2+ levels, linking Mg2+ homeostasis to the mammalian circadian clock (Uetani et al., Reference Uetani, Hardy, Gravel, Kiessling, Pietrobon, Wong, Chénard, Cermakian, St-Pierre and Tremblay2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lahens, Yue, Arnold, Pakstis, Schwarz and Sehgal2021).

In Arabidopsis, Mg2+ deficiency consistently lengthens the circadian period and dampens oscillation amplitude, a response also conserved in Ostreococcus and human U2OS cells (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021; Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016; Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Craciun, Inzé and Verbruggen2010). This effect is amplified under long-day photoperiods and in the presence of sucrose, suggesting that both light and metabolic status modulate the interaction between Mg2+ and the clock (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021; Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, Harren, Inzé and Verbruggen2010). Mg2+ also interacts with light-perception pathways, notably phytochromes, feeding back to regulate the clock (Rivière et al., Reference Rivière, Xiao, Gutsch, Defrance, Webb and Verbruggen2021). However, unlike NO3 −, Mg2+ pulses fail to reset circadian phase, suggesting that Mg2+ does not act as an entrainment signal in Arabidopsis (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021).

In rice, chloroplast Mg2+ oscillations are directly circadian-regulated via OsMGT3 (AtMGT10), which exhibits rhythmic expression peaking around dawn (J. Li et al., Reference Li, Yokosho, Liu, Cao, Yamaji, Zhu, Liao, Ma and Chen2020), and is repressed by two PRR proteins (OsPRR59, OsPRR95) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tian, Li, Bai, Zhang, Li, Cao and Chen2022). OsMGT3 rhythmic expression generates diel fluctuations of Mg2+ in rice chloroplasts, influencing Rubisco activity and photosynthetic carbon fixation rates (C.-Q. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tian, Li, Bai, Zhang, Li, Cao and Chen2022). Knockout mutants osmgt3 show reduced chloroplast Mg2+ rhythms and photosynthetic efficiency, while mesophyll-specific overexpression enhances growth and carbon assimilation (Li et al., Reference Li, Buckley and Haydon2022). This remains the only confirmed example of a clock-controlled Mg2+ transporter in plants.

6.3. Magnesium, metabolism and circadian integration

Magnesium's regulation of circadian rhythms is deeply intertwined with its role in cellular energy metabolism. As the physiological cofactor of ATP, Mg2+ is required for most energy-dependent reactions, including photosynthesis, ATP synthase activity and translation (Kleczkowski & Igamberdiev, Reference Kleczkowski and Igamberdiev2021; Ko et al., Reference Ko, Hong and Pedersen1999). In chloroplasts, ATP synthesis increases with external Mg2+ supply in a light-dependent manner (Lin & Nobel, Reference Lin and Nobel1971; Ishijima et al., Reference Ishijima, Uchibori, Takagi, Maki and Ohnishi2003; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Peng, Li and Liao2018), whereas Mg2+ deficiency causes ADP accumulation, impaired respiration and growth arrest (Gout et al., Reference Gout, Rébeillé, Douce and Bligny2014).

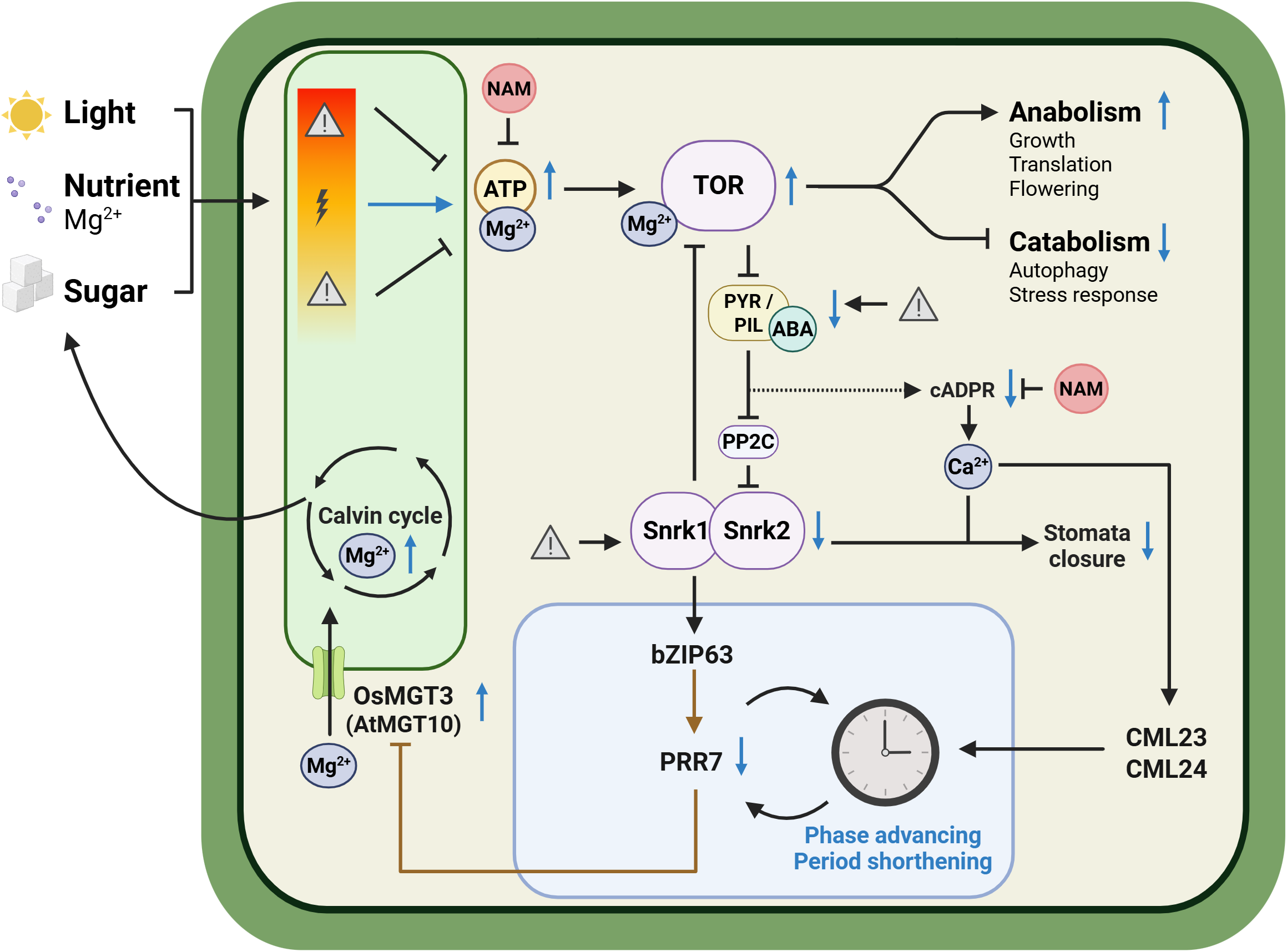

Through its tight coupling with adenylate metabolism, Mg2+ functions upstream of the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) pathway, a conserved kinase energy-sensor complex that modulates the circadian clock and integrates nutrient, hormone and environmental signals to promote growth and translation while repressing autophagy in both mammals and plants (Khapre et al., Reference Khapre, Patel, Kondratova, Chaudhary, Velingkaar, Antoch and Kondratov2014; Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Shi, Li, Fu, Liu, Xiong and Sheen2019; Zhang, Meng, et al., Reference Zhang, Meng, Li, Zhou, Ma, Fu, Schwarzländer, Liu and Xiong2019; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Zhang, Fu, Zhou, Long, He, Yang, Li and Peng2021; Meng, Zhang, Li, et al., Reference Meng, Zhang, Li, Shen, Sheen and Xiong2022; Urrea-Castellanos et al., Reference Urrea-Castellanos, Calderan-Rodrigues, Artins, Musialak-Lange, Macharanda-Ganesh, Fernie, Wahl and Caldana2025). Mammalian TOR activity is highly Mg2+-dependent, since MgATP functions as its substrate and an additional Mg2+ ion binds the active site to enable target phosphorylation (Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016; Kleczkowski & Igamberdiev, Reference Kleczkowski and Igamberdiev2023). TOR form an antagonistic regulatory module with the Sucrose non-fermenting-Related protein Kinase 1 (SnRK1). TOR inhibits SnRK1 signalling under energy-replete conditions, whereas SnRK1 suppress TOR activity during energy-deplete conditions, shifting metabolism from growth towards conservation, autophagy and stress responses. Activated SnRK1 phosphorylates and activates the transcription factor basic leucine Zipper 63 (bZIP63), which in turn binds to the PRR7 promoter to increase its transcription. Elevated PRR7 expression delays circadian phase and is required for sugar-induced shortening of the circadian period (Figure 2) (Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Mielczarek, Robertson, Hubbard and Webb2013; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Matiolli, Viana, Hearn, Kusakina, Belbin, Wells Newman, Yochikawa, Cano-Ramirez, Chembath, Cragg-Barber, Haydon, Hotta, Vincentz, Webb and Dodd2018).

Figure 2. Hypothetical working model linking magnesium homeostasis, metabolism, calcium signaling, stomatal regulation and circadian clock in plants.

Under optimal conditions of light, sugar and nutrient availability, TOR is activated. TOR promotes anabolic processes while repressing catabolic pathways, partially through inhibition of abscisic acid (ABA) signalling. TOR-mediated suppression of ABA signalling inhibits SnRK1 and SnRK2 kinases, which modulate the bZIP63-PRR7 regulatory module. This module feeds back to the circadian clock, resulting in phase advancement and period shortening.

TOR also represses SnRK2 and cADPR-dependent Ca2+ signalling pathways, promoting stomatal opening under favourable growth conditions. Oscillations in Ca2+ are sensed by Ca2+-binding proteins CML23 and CML24, which in turn feed back to the circadian clock.

In rice, the rhythmically expressed Mg2+ transporter gene OsMGT3 (AtMGT10 in Arabidopsis) is transcriptionally repressed by PRR proteins; disruption of this regulation diminishes Mg2+ oscillations, photosynthesis and overall growth.

Arrow codes: Black solid arrows, established regulation; brown solid arrows, established transcriptional regulation; black dashed arrows, proposed or indirect regulation requiring further validation; blue arrows, upregulation or downregulation under optimal growth conditions. Lightning bolt = optimal growth conditions, warning sign = stress conditions (e.g., energy or nutrient limitation) and NAM = nicotinamide (figure created with BioRender.com).

In human and algal cells, TOR inhibition lengthens the circadian period and abolishes the Mg2+-depletion lengthening effect, indicating that Mg2+ regulates the clock, at least in part, via TOR signalling (Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Hansen, Putker, Olivares-Yañez, Day, Eades, Larrondo, Hoyle, O’Neill and van Ooijen2016; Rubin, Reference Rubin2007; van Ooijen & O’Neill, Reference van Ooijen and O’Neill2016). In Arabidopsis, TOR inhibition similarly lengthens the circadian period in a dose-dependent manner (Zhang, Meng, et al., Reference Zhang, Meng, Li, Zhou, Ma, Fu, Schwarzländer, Liu and Xiong2019; Wang, Qin, et al., Reference Wang, Qin, Li, Zhang and Wang2020; Urrea-Castellanos et al., Reference Urrea-Castellanos, Caldana and Henriques2022). Restoration of sugar under low-energy condition reactivates TOR and normalizes/shortens period length, whereas this recovery is lost when TOR is silenced. Conversely, nicotinamide, a precursor of NAD+, inhibits sugar-driven ATP production, suppresses TOR activity, and lengthens the circadian period. Together, these observations demonstrate that both sugar-induced period shortening and nicotinamide-induced period lengthening are TOR-dependent (Figure 2) (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Gardner, Hotta, Hubbard, Dalchau, Love, Assie, Robertson, Jakobsen, Gonçalves, Sanders and Webb2007; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Mielczarek, Robertson, Hubbard and Webb2013; Zhang, Meng, et al., Reference Zhang, Meng, Li, Zhou, Ma, Fu, Schwarzländer, Liu and Xiong2019; de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021). Mg2+ deficiency also delays the phase of PRR7 expression, which may relate to the finding that prr7-11 mutation abolishes nicotinamide- and sugar-induced clock adjustments (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021; Farré & Weise, Reference Farré and Weise2012; Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Mielczarek, Robertson, Hubbard and Webb2013; Mombaerts et al., Reference Mombaerts, Carignano, Robertson, Hearn, Junyang, Hayden, Rutterford, Hotta, Hubbard, Maria, Yuan, Hannah, Goncalves and Webb2019). The convergent period-lengthening effects of Mg2+ deficiency, sugar deprivation and nicotinamide, along with their shared TOR-dependent influence on circadian timing, indicate that Mg2+ most likely modulates the circadian clock, at least in part, upstream of TOR signaling through conserved regulatory pathways in plants (Figure 2).

Conversely, there is growing evidence that the circadian clock exerts feedback on TOR signalling. In bzip63 mutants, rhythmic expression of Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) – a key downstream effector of TOR that phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6 to stimulate translation and cell growth – is disrupted, indicating that TOR signalling is at least partly under circadian control (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Matiolli, Viana, Hearn, Kusakina, Belbin, Wells Newman, Yochikawa, Cano-Ramirez, Chembath, Cragg-Barber, Haydon, Hotta, Vincentz, Webb and Dodd2018; Urrea-Castellanos et al., Reference Urrea-Castellanos, Caldana and Henriques2022). Moreover, PRR proteins (specifically PRR5, PRR7 and PRR9) repress the transcription of TANDEM ZINC FINGER 1 (TZF1); this repression prevents TZF1-mediated destabilization of TOR mRNA, thereby maintaining TOR signalling (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Zhang, Tian, Chong, Jang and Wang2019; Wang, Qin, et al., Reference Wang, Qin, Li, Zhang and Wang2020).

Sucrose influences the plant circadian clock in a context-dependent manner. Under low-energy conditions, sucrose shortens the circadian period, but has little impact in energy-repleted condition. Likewise, TOR signalling is activated by sugar availability but is repressed during sugar starvation or sugar excess, reflecting the complex integration of cellular energy status, sugar specificity, and stress signals in plants. Together, these observations highlight the intricate interplay between ionic cues, metabolic cues and circadian regulation (Haydon et al., Reference Haydon, Mielczarek, Robertson, Hubbard and Webb2013; Han et al., Reference Han, Hua, Li, Qiao, Yao, Hao, Li, Fan, De Jaeger, Yang and Bai2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Steed and Webb2022; Pereyra et al., Reference Pereyra, Parola, Lando, Rodriguez and Martínez-Noël2023). Therefore, the stronger impact of Mg2+ deficiency under sucrose-supplemented and long-day conditions (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Gutsch, Caluwé, Leloup, Gonze, Hermans, Webb and Verbruggen2021) likely arises from interactions between nutrient limitation and cellular energy status. Importantly, Mg2+ also plays a critical role in sucrose transport, further linking Mg2+ availability to carbon metabolism.

Mg2+ status, metabolism and circadian regulation also influence stomatal movement. TOR negatively regulates abscisic acid (ABA) signalling by phosphorylating Pyrabactin Resistance 1/PYR1-Like/Regulatory Component of ABA Receptor (PYR/PYL/RCAR) receptors, favouring growth over stress responses. Upon stress, ABA accumulates and binds to PYR/PYL receptors, inhibiting type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs), and activating SnRK1 and SnRK2 kinases, which phosphorylate downstream targets and inhibit TOR (Figure 2) (Baena-González & Hanson, Reference Baena-González and Hanson2017; Belda-Palazón et al., Reference Belda-Palazón, Adamo, Valerio, Ferreira, Confraria, Reis-Barata, Rodrigues, Meyer, Rodriguez and Baena-González2020, Reference Belda-Palazón, Costa, Beeckman, Rolland and Baena-González2022).

Mg2+ deficiency upregulates numerous ABA-responsive genes (Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Johnson, Strasser and Verbruggen2004; Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, et al., Reference Hermans, Vuylsteke, Coppens, Cristescu, Harren, Inzé and Verbruggen2010), whereas Mg2+ excess activates a subclass of SnRK2 kinases in an ABA-dependent manner which, together with Ca2+-binding proteins, contributes to the maintenance of Mg2+ homeostasis, likely via vacuolar transport (Mogami et al., Reference Mogami, Fujita, Yoshida, Tsukiori, Nakagami, Nomura, Fujiwara, Nishida, Yanagisawa, Ishida, Takahashi, Morimoto, Kidokoro, Mizoi, Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki2015).

Upon ABA perception, activated SnRK2s activate slow anion channel-associated 1 (SLAC1) and related ion channels, promoting anion efflux and membrane depolarization, a key step in stomatal closure (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Li, Hsu, Liu, Fu, Hou, Du, Xie, Zhang, Gao, Cao, Huang, Zhu, Tang, Wang, Tao, Xiong and Zhu2018; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Peng and Zhou2025). ABA also triggers cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR)-mediated Ca2+ release, generating transient cytosolic Ca2+ spikes that reinforce stomatal closure (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kuzma, Maréchal, Graeff, Lee, Foster and Chua1997; Leckie et al., Reference Leckie, McAinsh, Allen, Sanders and Hetherington1998). Notably, stomatal movement is known to be modulated by sugar, nicotinamide and TOR activity. TOR inhibition impairs light-induced stomatal opening, while nicotinamide, an inhibitor of both cADPR synthesis and TOR activity, inhibits ABA-induced stomatal closure in a dose-dependent manner (Han et al., Reference Han, Hua, Li, Qiao, Yao, Hao, Li, Fan, De Jaeger, Yang and Bai2022; Kottapalli et al., Reference Kottapalli, David-Schwartz, Khamaisi, Brandsma, Lugassi, Egbaria, Kelly and Granot2018; Leckie et al., Reference Leckie, McAinsh, Allen, Sanders and Hetherington1998; Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Xue, Murata, Yang, Nishimura, Wang and Schroeder2009). In addition, cytosolic Mg2+ levels, regulated in part by the tonoplast-localized Mg2+ transporter MGR1, are essential for stomatal opening, with vacuolar Mg2+ sequestration particularly important under high Mg2+ conditions (Inoue et al., Reference Inoue, Hayashi, Huang, Yokosho, Gotoh, Ikematsu, Okumura, Suzuki, Kamura, Kinoshita and Ma2022).

Cytosolic and stromal Ca2+ levels display circadian rhythmicity, peaking around dusk in mesophyll cells, and feed back to the clock via Calmodulin-Like proteins 23 and 24 (CML23 and CML24), which are upregulated by ABA and darkness (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Knight, Kondo, Masson, Sedbrook, Haley and Trewavas1995; Love et al., Reference Love, Dodd and Webb2004; Delk et al., Reference Delk, Johnson, Chowdhury and Braam2005; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Hubbard, Gardner, Jung, Aubry, Hotta, Mohd-Noh, Robertson, Hearn, Tsai, Dodd, Hannah, Carré, Davies, Braam and Webb2018; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Happeck, Meier, Hoang, Stribny, Hause, Ding, Morsomme, Baginsky and Peiter2019). These oscillations are thought to depend on cADPR-mediated Ca2+ release from internal stores, as in animals, although the plant cADPR-sensitive channel and cADPR cyclase remain unidentified (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Gardner, Hotta, Hubbard, Dalchau, Love, Assie, Robertson, Jakobsen, Gonçalves, Sanders and Webb2007; Ikeda et al., Reference Ikeda, Sugiyama, Wallace, Gompf, Yoshioka, Miyawaki and Allen2003). Strikingly, sucrose starvation and nicotinamide, which inhibit Mg2+-sensitive TOR signalling, not only lengthen the circadian period and alter stomatal movement but are also known to abolish Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 2) (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Gardner, Hotta, Hubbard, Dalchau, Love, Assie, Robertson, Jakobsen, Gonçalves, Sanders and Webb2007; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Knight, Kondo, Masson, Sedbrook, Haley and Trewavas1995; Martí Ruiz et al., Reference Martí Ruiz, Jung and Webb2020).

Together, these findings support a model in which Mg2+, Ca2+, NAD+, sugars and TOR form an integrated metabolic–ionic network that couples cellular energy status to circadian regulation (Figure 2). Mg2+ acts as a metabolic integrator, connecting adenylate pools to TOR signalling and circadian timing. Daily fluctuations in nutrients and metabolites, including Mg2+, Ca2+ and sugars, provide a direct mechanism by which changes in cellular energy are mirrored into circadian adjustments, feeding back to modulate clock function, stomatal dynamics, and stress responses. This framework highlights a complex non-transcriptional layer of circadian regulation, in which ionic and metabolic cues converge to coordinate temporal control of growth, metabolism, and environmental responses.

7. Conclusion and perspectives

Mg2+ plays a pivotal role in plant physiology, acting both as a structural element and as a versatile regulatory cofactor. It is essential for chlorophyll coordination, activation of ATP-dependent enzymes and maintenance of ion homeostasis and signalling processes. Beyond these classical roles, recent findings have revealed that Mg2+ also influences circadian regulation, positioning it as an integrator of temporal, metabolic and nutritional cues in plants.

Despite its broad functional spectrum, Mg2+ remains comparatively understudied relative to other macronutrients. Considerable progress has been made in identifying Mg2+ transporters, yet major questions remain regarding their regulation, subcellular dynamics and integration into whole-plant nutrient allocation strategies. The complex interactions of Mg2+ with other ions, such as K+, Ca2+, NH4 + and transition metals, represent another underexplored frontier, both at physiological and molecular scales.

In agronomic contexts, Mg2+ deficiency remains a widespread and often overlooked issue, particularly in acidic or intensively cultivated soils. Improving crop resilience and nutrient use efficiency will require a deeper understanding of how Mg2+ uptake, redistribution and sensing are modulated under stress and throughout plant development. Such knowledge will be instrumental for optimizing fertilization practices and guiding breeding strategies towards genotypes with enhanced Mg efficiency.

The recently established link between Mg2+ and circadian regulation opens promising research directions. Mg2+ may contribute to adaptive rhythmicity, fine-tuning metabolic and physiological processes in response to nutrient availability and environmental fluctuations. Investigating how Mg2+ homeostasis interacts with diurnal cycles and metabolic rhythms could uncover new regulatory mechanisms relevant to growth, yield and stress adaptation.

Future research should focus on the post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation of Mg2+ transporters, including the identification of upstream regulators such as kinases, phosphatases, small RNAs and protein interactors. Understanding how these components integrate into broader nutrient signalling and environmental response networks, such as those governed by circadian cues, light quality, or abiotic stress, will be key to grasping the dynamic control of Mg2+ homeostasis. Finally, exploring natural variation in transporter regulation across species or genotypes adapted to contrasting soils may reveal evolutionary strategies for Mg2+ acquisition and utilization, providing valuable targets for sustainable crop improvement.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/qpb.2025.10036.

Acknowledgements