1.1 The Problem

The shorelines of the world continue to be converted to artifacts through human actions such as eliminating dunes to facilitate construction of buildings and support infrastructure; grading beaches and dunes flat to facilitate access and create space for recreation; and mechanically cleaning beaches to make them more attractive to beach users. Beach erosion, combined with human attempts to retain shorefront buildings and infrastructure in fixed positions, can result in truncation or complete loss of beach, dune, and active bluff environments. The lost sediment may be replaced in beach nourishment operations, but nourishment is usually conducted to protect shorefront buildings or provide a recreational platform rather than to restore natural values (Figure 1.1). Sometimes nourished beaches are capped by a linear dune of uniform height alongshore designed to function as a dike against wave attack and flooding. Many of these dune dikes are built by earth-moving machinery rather than by aeolian processes, resulting in an outward form and an internal structure that differ from natural landforms. Dunes on private properties landward of public beaches are often graded and kept free of vegetation or graded and vegetated with a cover that may bear little similarity to a natural cover.

Figure 1.1 La Victoria Beach in Cádiz, Spain, showing lack of topography and vegetation on a nourished beach maintained and cleaned for recreation.

Transformation of coastal environments is intensified by the human tendency to move close to the coast (Smith Reference Smyth and Hesp1992; Wong Reference Wong1993; Lubke et al. Reference Lubke, Avis, Hellstrom, Salman, Berends and Bonazountas1995; Roberts and Hawkins Reference Roberts and Hawkins1999; Brown and McLachlan Reference Brown and McLachlan2002; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nordstrom, McLachlan, Jackson, Sherman and Polunin2008; Romano and Zullo Reference Romano and Zullo2014). The effects of global warming and sea level rise and increased impact of coastal storms are added to human pressures (FitzGerald et al. Reference FitzGerald, Fenster, Argow and Buynevich2008; Boon Reference Boon2012; Cazenave and Le Cozannet Reference Cazenave and Le Cozannet2013; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Kopp, Horton, Browning and Kemp2013; Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin and Plattner2013; Vousdoukas et al. Reference Vousdoukas, Bouziotas, Giardino, Bouwer, Voukoucalas and Feyen2018; Barnard et al. Reference Barbour and Davidson-Arnott2019; Fang et al. Reference Fang, Lincke and Brown2020; Mathew et al. Reference Mathew, Sautter and Ariffin2020), further amplifying the transformation. The most significant threat to coastal species is loss of habitat, especially if sea level rise is accompanied by increased storminess (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nordstrom, McLachlan, Jackson, Sherman and Polunin2008). Coastal development has already eliminated much natural beach and dune habitat worldwide (Defeo et al. Reference Deguchi, Ono, Araki and Sawaragi2009).

Sandy beach ecosystems could adapt to storms and sea level rise by retreating landward and maintaining structure and function over various spatial and temporal scales (Orford and Pethick Reference Orford and Pethick2006; Cooper and McKenna Reference Cooper and McKenna2008; Berry et al. Reference Berry, Fahey and Meyers2013). Retreat from the coast (managed realignment) would resolve problems of erosion and provide space for new landforms and biota to become reestablished. The advantages of adapting by retreat are acknowledged, but actual responses by removing human structures from developed ocean coasts are limited and often resisted by the public (Ledoux et al. Reference Ledoux, Cornell, O’Riordan, Harvey and Banyard2005; Abel et al. Reference Abel, Gorddard, Harman, Leitch, Langridge, Ryan and Heyenga2011; Luisetti et al. Reference Luisetti, Turner, Bateman, Morse-Jones, Adams and Fonseca2011; Morris Reference Morris2012; Niven and Bardsley Reference Niven and Bardsley2013; Cooper and Pile Reference Cooper and Pile2014; National Research Council 2014; Costas et al. Reference Costas, Ferreira and Martinez2015; Harman et al. Reference Harman, Heyenga, Taylor and Fletcher2015). Retreat appears unlikely except on sparsely developed shores (Kriesel et al. Reference Kriesel, Keeler and Landry2004). Most local governments and property owners would probably advocate management options that approach the status quo (Leafe et al. Reference Leafe, Pethick and Townend1998), even under accelerated sea level rise (Titus Reference Titus1990). The great value of land and real estate on coastlines and the level of investment on developed shores are too great to consider anything short of holding the line (Nordstrom and Mauriello Reference Nordstrom and Mauriello2001; Niven and Bardsley Reference Niven and Bardsley2013).

Post-storm evaluations reveal ample evidence of the vulnerability of shorefront houses and infrastructure to storm damage (Saffir Reference Saffir1991; Sparks Reference Sparks1991; Platt et al. Reference Platt, Salvesen and Baldwin2002; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Rogers and Sallenger2011; Hatzikyriakou et al. Reference Hatzikyriakou, Lin, Gong, Xian, Hu and Kennedy2016; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Liu, Wu and Gong2016; O’Neil and Van Abs Reference O’Neil and van Abs2016). Despite this destruction, strategies for reducing the number of people and buildings at risk and redistributing the risks, benefits, and costs among stakeholders are rarely implemented (Abel et al. Reference Abel, Gorddard, Harman, Leitch, Langridge, Ryan and Heyenga2011; Rabenold Reference Rabenold2013; National Research Council 2014). More often, buildings and support infrastructure destroyed by long-term erosion or major storms are quickly rebuilt in reconstruction efforts, and landscapes after the storm often bear a greater human imprint than landscapes before the storm (Fischer Reference Fischer1989; Meyer-Arendt Reference Meyer-Arendt1990; FitzGerald et al. Reference FitzGerald, van Heteren and Montello1994; Nordstrom and Jackson Reference Nordstrom and Jackson1995; Platt et al. Reference Platt, Salvesen and Baldwin2002). Market and policy incentives for development and redevelopment in coastal communities can overwhelm attempts of planners to discourage development (Andrews Reference Andrews, O’Neil and van Abs2016; Holcomb Reference Holcomb, O’Neil and van Abs2016).

Problems associated with conversion of coasts to accommodate human uses include loss of topographical variability (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom2000); loss of natural landforms and their habitats (Beatley Reference Beatley1991; Garcia-Lozano et al. Reference Garcia-Lozano, Pintó and Daunis-i-Estadella2018; Pérez-Hernández et al. Reference Pérez-Hernández, Ferrer-Valero and Hernández-Calvento2020); reduction in space for remaining habitat (Dugan et al. Reference Dugan, Hubbard, Rodil, Revell and Schroeter2008) or elimination of biota from those surfaces (Kelly Reference Kelly2014); fragmentation of landscapes (Berlanga-Robles and Ruiz-Luna Reference Berlanga-Robles and Ruiz-Luna2002; Masucci and Reimer Reference Masucci and Reimer2019); threats to endangered species (Melvin et al. Reference Melvin, Griffin and MacIvor1991; Maslo et al. Reference Maslo, Leu, Pover, Weston, Gilby and Schlacher2019); reduction in seed sources and decreased resilience of plant communities following loss by storms (Cunniff Reference Cunniff1985; Gallego-Fernández et al. Reference Gallego-Fernández, Morales-Sánchez, Martínez, García-Franco and Zunzunegui2020); loss of intrinsic value (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom1990); loss of original aesthetic and recreational values (Cruz Reference Cruz, Salman, Langeveld and Bonazountas1996; Demirayak and Ulas Reference Delgado-Fernandez, Davidson-Arnott and Hesp1996); and loss of the natural heritage or image of the coast, which affects appreciation of environmental benefits or ability of stakeholders to make informed decisions on environmental issues (Télez-Duarte Reference Télez-Duarte, Fermán-Almada, Gómez-Morin and Fischer1993; Golfi Reference Golfi, Salman, Langeveld and Bonazountas1996; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Vandemark2000; Gesing Reference Gesing2019; Lapointe et al. Reference Lapointe, Gurney and Cumming2020). Natural physical and ecological processes cannot be relied on to reestablish natural characteristics in developed areas without people allowing these processes to occur. Establishment of coastal preserves, such as state/provincial or national parks, helps maintain environmental inventories, but inaccessibility to these locations or restrictions on intensity of use do not provide the opportunity for many visitors to experience nature within them (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom and Dallmeyer2003). Natural enclaves near regions that are intensively developed may be too small to evolve naturally (De Ruyck et al. Reference De Ruyck, Ampe and Langohr2001). Natural enclaves near regions with shore protection structures are subject to sediment starvation and accelerated erosion that alter the character and function of habitat from former conditions (Roman and Nordstrom Reference Roman and Nordstrom1988). Natural processes may be constrained within areas managed for nature protection because of the need to modify those environments to provide predictable levels of flood protection for adjacent developed areas (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Jackson2007c). Designating protected areas to preserve endangered species may have a limited effect in reestablishing natural coastal environments unless entire habitats or landscapes are included in preservation efforts (Waks Reference Waks1996; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Kerley and McLachlan1997). Establishment of coastal preserves may also have the negative effect of providing an excuse for ignoring the need for nature protection or enhancement in areas occupied by humans (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom and Dallmeyer2003).

Alternatives that enhance the capacity of coastal systems to respond to perturbations by maintaining diverse landforms and habitats should supplement or replace alternatives that resist the effects of erosion and flooding associated with climate change (Nicholls and Hoozemans Reference Nicholls and Hoozemans1996; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Smit, Goosen and Hulsbergen1998; Nicholls and Branson Reference Nicholls and Branson1998; Orford and Pethick Reference Orford and Pethick2006; Cooper and McKenna Reference Cooper and McKenna2008). Restoring lost beach and dune habitat can compensate for environmental losses elsewhere, protect endangered species, retain seed sources, strengthen the drawing power of the shore for tourism, and reestablish an appreciation for naturally functioning landscape components (Breton and Esteban Reference Breton, Esteban, Healy and Doody1995; Breton et al. Reference Breton, Clapés, Marqués and Priestly1996, Reference Breton, Esteban and Miralles2000; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Vandemark2000). Ecologists, geomorphologists, and environmental philosophers point to the need to help safeguard nature on developed coasts by promoting a new nature that has an optimal diversity of landforms, species, and ecosystems that remain as dynamic and natural as possible in appearance and function while being compatible with human uses (van der Maarel Reference van der Maarel, Jefferies and Davy1979; Westhoff Reference Westhoff1985, Reference Westhoff, van der Meulen, Jungerius and Visser1989; Doody Reference Doody1989; Roberts Reference Roberts1989; Light and Higgs Reference Light and Higgs1996; Pethick Reference Pethick, Jones, Healy and Williams1996; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Vandemark2000). There is also a growing interest in trying to develop a new symbiotic, sustainable relationship between human society and nature (with its diversity and dynamism) and to value the natural world for the sake of relations between humans and nature (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Lopukhine and Hillyard1995; Cox Reference Cox1997; Naveh Reference Naveh1998; Higgs Reference Higgs2003; Gesing Reference Gesing2019).

1.2 Human Modifications

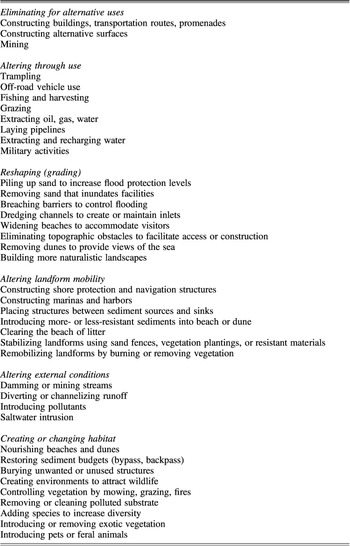

Coastal changes and economically driven human actions are now recognized as mutually linked, often in iterative cycles, such as erosion and mitigation (Lazarus et al. Reference Lazarus, McNamara, Smith, Gopalakrishnan and Murray2011, Reference Lazarus, Ellis, Murray and Hall2016; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Gopalakrishnan, McNamara and Smith2013; Gopalakrishnan et al. Reference Gopalakrishnan, Landry, Smith and Whitehead2016). The increasing pace of human alterations and the increasing potential for people to reconstruct nature for human use require reexamination of human activities (Table 1.1) in terms of the many ways they can be made more compatible with nature. Some environmental losses are associated with every modification, even the most benign ones, but the losses may be small and temporary. Human-modified landforms are often smaller than their natural equivalents, with fewer distinctive sub-environments, a lower degree of connectivity between sub-environments, and often a progressive restriction in the ability of the coast to adjust to future environmental losses (Pethick Reference Pethick, Bodungen and Turner2001). The challenge for restoration initiatives is to enhance the natural value of these landforms and increase their resilience through human actions.

| Eliminating for alternative uses Constructing buildings, transportation routes, promenades Constructing alternative surfaces Mining Altering through use Trampling Off-road vehicle use Fishing and harvesting Grazing Extracting oil, gas, water Laying pipelines Extracting and recharging water Military activities Reshaping (grading) Piling up sand to increase flood protection levels Removing sand that inundates facilities Breaching barriers to control flooding Dredging channels to create or maintain inlets Widening beaches to accommodate visitors Eliminating topographic obstacles to facilitate access or construction Removing dunes to provide views of the sea Building more naturalistic landscapes Altering landform mobility Constructing shore protection and navigation structures Constructing marinas and harbors Placing structures between sediment sources and sinks Introducing more- or less-resistant sediments into beach or dune Clearing the beach of litter Stabilizing landforms using sand fences, vegetation plantings, or resistant materials Remobilizing landforms by burning or removing vegetation Altering external conditions Damming or mining streams Diverting or channelizing runoff Introducing pollutants Saltwater intrusion Creating or changing habitat Nourishing beaches and dunes Restoring sediment budgets (bypass, backpass) Burying unwanted or unused structures Creating environments to attract wildlife Controlling vegetation by mowing, grazing, fires Removing or cleaning polluted substrate Adding species to increase diversity Introducing or removing exotic vegetation Introducing pets or feral animals |

Human actions are not always negative, especially if applied in moderation and with an awareness of environmental impacts. The effects of agriculture can range from “disastrous” to adding real ecological values (Heslenfeld et al. Reference Heslenfeld, Jungerius, Klijn, Martínez and Psuty2004). Intensive grazing can destroy vegetation cover and mobilize entire dune fields, but controlled grazing can restore or maintain species diversity (Grootjans et al. Reference Grootjans, Adema, Bekker, Lammerts, Martínez and Psuty2004; Kooijman Reference Kooijman, Martínez and Psuty2004). Many sequences of vegetation succession, now assumed to be natural, appear to have been initiated by human activity when examined more closely (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Lopukhine and Hillyard1995; Doody Reference Doody2001). Many changes, such as conversion of the Dutch dunes to recharge areas for drinking water, introduced a new landscape, with different species utilization and different uses for nature appreciation (Baeyens and Martínez Reference Baeyens, Martínez, Martínez and Psuty2004). The protection provided by beaches and dunes altered by humans to provide flood protection has allowed more stable natural environments to form that have developed their own nature conservation interest and may even be protected by environmental regulations (Doody Reference Doody, Salman, Berends and Bonazountas1995; Orford and Jennings Reference Orford, Jennings and Hooke1998). The messages are clear. Humans are responsible for nature, and human actions can be made more compatible with nature by modifying practices to retain as many natural functions as possible in modifying landscapes for human use. These two messages are increasingly applicable in natural coastal areas used as parks as well as developed areas.

1.3 Values, Goods, and Services of Beaches and Dunes

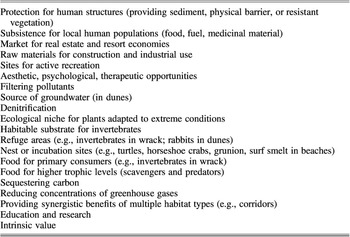

Beaches and dunes have their own intrinsic value, but they also provide many goods and services of direct and indirect benefit to humans (Table 1.2). In coastal environments, a good can range from nesting and incubation sites for commercial marine species to potable water supplied by dune fields. Services can include filtering of pollutants or natural beach accretion that provides recreational opportunities. The term “value” used in this book indicates human value (that assigned to the beach/dune system as a result of the goods and services produced) and the natural value inherent to the beach/dune system independent of human assignation (intrinsic value). The term “natural capital” is often applied as an alternative term for goods and services. Debates over the natural capital concept may occur because it appears to reduce nature to its monetary exchange or instrumental value and cannot be justified in arguments about preservation or intrinsic value (Daly Reference Damgaard, Thomsen, Borchsenius, Nielsen and Strandberg2020; Des Roches Reference Des Roches2020). For example, a wide beach and dune that provide storm protection to oceanfront property and recreation for tourists can be placed in economic terms (Lazarus et al. Reference Lazarus, McNamara, Smith, Gopalakrishnan and Murray2011; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Gibeaut, Yoskowitz and Starek2015), whereas the significance for a noncommercial species or the therapeutic use of a landscape is more challenging. Optimum designs for beaches and dunes that enhance these alternative uses can be quite different, as will be seen in subsequent chapters. The natural capital concept has many applications useful to economic or social arguments and philosophical debate but appears less convincing as a rationale for managing natural resources than the terms “values,” “goods,” or “services” without disciplinary contexts and subtexts. Accordingly, we use these terms, favoring the word “value” for general application.

Table 1.2. Values, goods, and services provided by coastal landforms, habitats, or species

| Protection for human structures (providing sediment, physical barrier, or resistant vegetation) Subsistence for local human populations (food, fuel, medicinal material) Market for real estate and resort economies Raw materials for construction and industrial use Sites for active recreation Aesthetic, psychological, therapeutic opportunities Filtering pollutants Source of groundwater (in dunes) Denitrification Ecological niche for plants adapted to extreme conditions Habitable substrate for invertebrates Refuge areas (e.g., invertebrates in wrack; rabbits in dunes) Nest or incubation sites (e.g., turtles, horseshoe crabs, grunion, surf smelt in beaches) Food for primary consumers (e.g., invertebrates in wrack) Food for higher trophic levels (scavengers and predators) Sequestering carbon Reducing concentrations of greenhouse gases Providing synergistic benefits of multiple habitat types (e.g., corridors) Education and research Intrinsic value |

Ecosystem services often exhibit spatial and temporal variation within a given landscape, and they can have weak association with other services (Biel et al. Reference Biel, Hacker, Ruggiero, Cohn and Seabloom2017). Not all goods and services can be provided within a given shoreline segment, even in natural systems, but many may be available regionally, given sufficient space and alongshore variation in exposure to coastal processes and sediment types. It may not be possible to take advantage of some of the goods and services, even where the potential exists. One or a few goods and services can be overexploited, resulting in the loss of others (Pérez-Maqueo et al. Reference Pérez-Maqueo, Martínez, Lithgow, Mendoza-González, Feagin, Gallego-Fernández, Martínez, Gallego-Fernández and Hesp2014). Mining and several forms of active recreation may be incompatible with use of beaches for nesting. Alternatively, beaches and dunes can have multiple uses, such as protecting property from coastal hazards while providing nesting sites, habitable substrate, and refuge areas for wildlife, if human uses are controlled using compatible regulations (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Kraus2011).

Not all uses that take advantage of the goods and services provided by beaches and dunes should be targets of practical restoration efforts. It makes little sense to restore minerals in a landform only to mine them later. Provision of new sources of fuel to a subsistence economy may be accommodated in more efficient ways than attempting to favor driftwood accumulation on a restored beach or planting trees on a dune. In these cases, restoration efforts may not be required to sustain a human use, but they may be required to reinstate the microhabitats and associated processes that were lost through previous exploitation. Components of ecosystems should not be seen as exchangeable goals that can be used and created again to suit human needs (Higgs Reference Higgs2003; Throop and Purdom Reference Throop and Purdom2006).

1.4 Approaches for Restoring and Maintaining Natural Landforms and Habitats

Coastal evolution may take different routes. The development process need not result in reshaping of beaches into flat, featureless recreation platforms (Figure 1.1) or totally eliminating dune environments in favor of structures. The trend toward becoming a cultural artifact can be reversed, even on intensively developed coasts, if management actions are taken to restore natural features (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Kraus2011). Creating and maintaining natural assemblages of landforms and biota in developed areas (Figure 1.2) can help familiarize people with nature, instill the importance of restoring or preserving it, enhance the image of a developed coast, influence landscaping actions taken by neighbors, and enhance the likelihood that natural features will be a positive factor in the resale of coastal property (Norton Reference Norton2000; Savard et al. Reference Savard, Clergeau and Mennechez2000; Conway and Nordstrom Reference Conway and Nordstrom2003). Tourism that is based on environmental values can extend the duration of the tourist season beyond summer (Turkenli Reference Turkenli2005). Restoration of natural habitats thus has great human-use value in addition to natural value.

Figure 1.2 Two views of Folly Beach, South Carolina, USA, showing the effect of beach nourishment in reestablishing dunes.

The reasons for restoration may be classified in different ways (Hobbs and Norton Reference Hobbs and Norton1996; Peterson and Lipcius Reference Peterson and Lipcius2003) such as (1) improving habitat degraded by pollutants, physical disturbance, or exotic species; (2) replenishing resources depleted by overuse; (3) replacing landforms and habitats lost through erosion; (4) allowing human-altered land (e.g., farms) to revert to nature; (5) compensating for loss of natural areas resulting from construction of new human facilities; and (6) establishing a new landscape image or recapturing lost environmental heritage. Restoration can be conducted at virtually any scale and used in a variety of ways.

The terms conservation and restoration have been distinct as policy directives, but programs for either will have elements of the other within them. Maintenance of the abundance and diversity of natural landforms and habitats depends on the adoption of several actions including (1) identifying remaining natural and semi-natural habitat; (2) establishing new nature reserves; (3) protecting existing reserves from peripheral damage; (4) making human uses in other areas compatible with the need for sustainability; and (5) rehabilitating degraded areas, including reinstating natural dynamic processes (Doody Reference Doody, Salman, Berends and Bonazountas1995). The first four actions may be defined as conservation, whereas the last action may be defined as restoration. This book addresses this last need in its many forms and scales, with special emphasis on regional and local actions. The goals for conservation and restoration become complementary in a changing world in which species are shifting distributions, communities are disassembling and reassembling in new configurations, extreme events are pushing systems beyond past thresholds, and outcomes of human actions are increasingly uncertain (Wiens and Hobbs Reference Wiens and Hobbs2015). Restoration of a lost habitat makes that habitat a target of future conservation; maintenance of habitat in a conservation area subject to degradation by human activities may require periodic restoration efforts; and successful evolution of a restored area may depend on the proximity of seed banks in a nearby conservation area. Many of the management principles appropriate to conservation or restoration will apply to the other and can be tailored to the specific context. Restoration goals can be compatible with conservation goals in improving degraded habitat. Alternatively, restoration goals can counteract conservation goals; for example, using restoration as compensation or mitigation for development of natural areas – a practice severely criticized because of the difficulty of replicating lost environments (Zedler Reference Zedler1991).

Many coastal environments are protected by international, national, and regional policies governing use of natural resources and establishment of nature reserves by governmental and nongovernmental organizations (Doody Reference Doody2001; Rhind and Jones Reference Rhind and Jones2009). The EU Habitats Directive and its designation of the Natura 2000 network of protected areas covering Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats is key to conservation and restoration in much of Europe. Natural habitat types and animal and plant species whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation are identified as are criteria for selecting eligible sites for inclusion. Natura 2000 sites are protected through a series of policy instruments put in place by the directives and subsequently translated into legislation by EU countries. For example, Article 6 of the Habitats Directive requires member states to take measures within Natura 2000 to maintain and restore the habitats and species in a favorable conservation status and avoid activities that could significantly disturb these species or result in damage or deterioration of their habitats or habitat types. Other EU initiatives provide impetus, rationale, and suggestions for maintaining and enhancing key environmental resources. The EUrosion study (European Commission 2004) promotes the need to work with natural processes; for coasts, this means working with the sediments and processes as the foundation for the habitats and the species they support (Rees et al. Reference Rees, Curson and Evans2015). Every country has numerous policies and regulations affecting management of coastal resources (e.g., the Wildlife and Countryside Act, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and Biodiversity Action Plan in the United Kingdom). About 83 percent of the dune area in the United Kingdom has been protected under legislation because of biological interest (Williams and Davies Reference Williams and Davies2001). The number of national regulations can be large. Ariza (Reference Ariza2011) lists twenty-nine legal texts for beach management in Spain alone. The number of regulations is not necessarily the answer to nature protection in some locations. Local actions can disregard the principles and guidelines developed at higher levels of government (Cristiano et al. Reference Cristiano, Portz, Nasser, Pinto, Silva, Barboza, Botero, Cervantes and Finkl2018; Jayappa and Deepika Reference Jayappa, Deepika, Botero, Cervantes and Finkl2018).

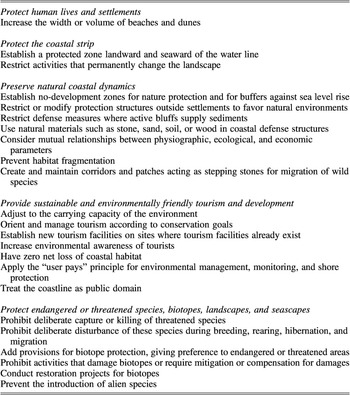

Evaluation of the significance of local legal provisions is beyond the scope of this book, but examples of international policy guidelines for conservation and restoration are presented here for perspective (Table 1.3). These guidelines can be applied at nearly any spatial and governmental level with minor changes in wording. The need to protect human lives and settlements is likely to be an overriding concern, but many activities taken to protect people can be made compatible with guidelines to allow natural dynamics, provide for sustainable development, and protect biotopes and landscapes (Table 1.3), and can be accommodated within traditional shore protection designs. Examples include (1) allowing dikes or protective dunes to erode to expose more land to episodic inundation by the sea while increasing the structural integrity of new dikes farther landward; (2) restoring sediment transfers from bluffs to adjacent shore segments; (3) increasing sediment transport rates through groin fields; and (4) replacing exotic vegetation with native species. New strategies are emerging for innovative nature-based coastal protection and management as an alternative or complement to hard solutions. New terms such as “ecoengineering,” “building with nature,” “green infrastructure,” and “living shorelines” reflect these softer approaches (Pontee and Tarrant Reference Pontee and Tarrant2017; Martínez et al. Reference Martínez, Chávez, Lithgow and Silva2019; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Konlechner, Ghisalberti and Swearer2019). These strategies include recreating natural habitats, enhancing existing habitats, using more organic materials for new hard structures, and enhancing existing hard infrastructure by favoring colonization by marine organisms or combined hard structures with natural features to form hybrid solutions (Firth et al. Reference Firth, Thompson and Bohn2014; Pontee and Tarrant Reference Pontee and Tarrant2017). Awareness of a landscape’s aesthetic appeal can lead to designs that are considered attractive as well as functional (Gobster et al. Reference Gobster, Nassauer, Daniel and Fry2007; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Giardino and Pranzini2016), with natural features providing much of the aesthetic appeal.

| Protect human lives and settlements Increase the width or volume of beaches and dunes Protect the coastal strip Establish a protected zone landward and seaward of the water line Restrict activities that permanently change the landscape Preserve natural coastal dynamics Establish no-development zones for nature protection and for buffers against sea level rise Restrict or modify protection structures outside settlements to favor natural environments Restrict defense measures where active bluffs supply sediments Use natural materials such as stone, sand, soil, or wood in coastal defense structures Consider mutual relationships between physiographic, ecological, and economic parameters Prevent habitat fragmentation Create and maintain corridors and patches acting as stepping stones for migration of wild species Provide sustainable and environmentally friendly tourism and development Adjust to the carrying capacity of the environment Orient and manage tourism according to conservation goals Establish new tourism facilities on sites where tourism facilities already exist Increase environmental awareness of tourists Have zero net loss of coastal habitat Apply the “user pays” principle for environmental management, monitoring, and shore protection Treat the coastline as public domain Protect endangered or threatened species, biotopes, landscapes, and seascapes Prohibit deliberate capture or killing of threatened species Prohibit deliberate disturbance of these species during breeding, rearing, hibernation, and migration Add provisions for biotope protection, giving preference to endangered or threatened areas Prohibit activities that damage biotopes or require mitigation or compensation for damages Conduct restoration projects for biotopes Prevent the introduction of alien species |

One of the impediments to restoration efforts is the cost of projects. Application of the “user pays” principle to the requirement of zero net loss of coastal habitat (Table 1.3) can make restoration feasible by defraying costs using funds required for compensation or mitigation of environmentally damaging actions elsewhere, such as construction of marinas (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Jackson2007c).

1.5 Definitions

Different approaches to restoration practice can occur depending on the balance sought between humans and nature or the disciplinary specialties of the parties conducting the restoration (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001; Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom and Dallmeyer2003). The word restoration implies ecological restoration to many managers and planners, but coastal restoration also includes reestablishment of sediment budgets and space for landforms to undergo cycles of erosion, deposition, and migration (Orford and Pethick Reference Orford and Pethick2006; Cooper and McKenna Reference Cooper and McKenna2008) as well as of previous human values, including cultural, historical, traditional, artistic, social, economic, and experiential (Nuryanti Reference Nuryanti1996; Higgs Reference Higgs1997; Wortley et al. Reference Wortley, Hero and Howes2013). Other terms may be used as synonyms or surrogates for restoration, including “nature development,” “rehabilitation,” “reclamation,” “enhancement,” “sustainable conservation” (that implies ongoing human input) among others introduced and defined in Corlett (Reference Corlett2016). Terms used in a cultural restoration context may be similar to some used for environmental restoration or include “renovation” and “reconstruction.” Like the related term “ecological engineering,” many synonyms can be used for restoration, and many subdisciplines can claim to practice it, with different emphases (Mitsch Reference Mitsch1998).

An ongoing discussion can be traced in the literature about the appropriate term to use for what practitioners of restoration do, and the meaning of terms may become vague, shift in their meaning, or fade from use (Halle Reference Halle2007). There seems to be little value in substituting an alternative general term for restoration, when that new term may itself be subject to reinterpretation, misinterpretation, or misuse. The vagaries associated with the term restoration can be eliminated for beach and dune restoration initiatives by identifying the goals and actions taken. These include (1) restoring the sediment budget to provide substrate for new environments or a seaward buffer against wave or wind erosion to allow landward environments to evolve to more mature states; (2) restoring a vegetation cover on a backshore to cause dunes to evolve to provide habitat, protect against flooding, or create a more representative image of a natural coast; or (3) restoring the process of erosion and deposition by removing shore protection structures or allowing them to deteriorate. Allowing an aging shore protection structure to deteriorate, rather than rebuilding it, is an example of use of the concept of restoration as a positive way to promote what is essentially a low-cost, do-nothing alternative.

Ecological restoration has been defined as an intentional activity that initiates or accelerates the recovery of an ecosystem with respect to its health, integrity, and sustainability (Society for Ecological Restoration 2002). Elements of this definition would be appropriate for restoration to establish non-living components of a degraded environment, but strict adherence to ecological principles would not be required. The goal of ecological restoration is understood to emulate the structure, function, diversity, dynamics, and sustainability of the specified ecosystem, but the requirement that it represent a self-sustaining ecosystem that is not reliant on human inputs would have to be relaxed for systems that remain intensively used by humans (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Floret, Le Floc’h, Ovalle and Pontanier1993). Ecological fidelity should be at the core of restoration, but successive layers of human context must be added to produce an expanded conception of good ecological restoration for locations where humans remain part of the system (Higgs Reference Higgs1997). Present underlying principles for ecological restoration (Table 1.4) recognize the importance of these socioeconomic inputs.

| Engage stakeholders Satisfy cultural, social, economic, and ecological values Foster a closer and reciprocal engagement with nature Lead to improved social and ecological resilience and human well-being Draw on many types of knowledge Traditional practitioner ecological knowledge Local ecological knowledge Scientific discovery through experiments and practitioner–researcher collaborations Be informed by native reference ecosystems while considering environmental change Use reference models, targets, and goals based on specific real-world ecosystems Account for temporal dynamics, including models of future change Anticipate multiple or sequential references to identify potential successional paths Acknowledge social/ecological histories and traditions in some areas Support ecosystem recovery processes Use remnant species to kick-start regeneration Consider additional treatments or research to overcome limitations to recovery Assess using clear goals and measurable indicators Use natural and social attributes Monitor progress over time (including former, restored, and subsequent conditions) Apply adaptive management to systematically improve restoration success Seek the highest level of recovery attainable Start at highest level in the partial recovery/full recovery continuum Adopt a policy of continuous improvement informed by sound monitoring Apply at large scales to gain cumulative value Include actions at landscape, reach/drift cell, and regional scales Address degradation from outside restored site (pollutants, sediment blockages, exotics) Enhance connectivity (e.g., wildlife corridors) Acknowledge broader stakeholder challenges or support Make part of a continuum of restorative activities Acknowledge the physical and social context Recognize the role of the project within a broad sustainability paradigm |

1.6 Categories of Restoration

Management options that can be implemented to achieve a more naturally functioning beach and dune system must be based on practices that are doable as documented by evaluations of topography, biota, and perceptions of stakeholders. General restoration goals for human altered areas include the following: (1) using active management to retain a desired characteristic; (2) getting a site off a human trajectory; or (3) restoring functions rather than restoring original conditions with all of the former species present (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Ambrose and Poff1997; White and Walker Reference White and Walker1997). The former goal (using a target species or landscaping approach) is designed to create a certain look quickly, whereas the second and third goals are designed to lead to a system that is self-sustaining, requiring no inputs of energy or materials from managers or, at the least, requiring minimal intervention (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Lopukhine and Hillyard1995). The first goal (using active management) is especially appropriate for restoring and maintaining stable backdune environments on private properties, where intensive actions at a local scale are feasible. The other two goals are more appropriate in areas managed by a government entity, where actions such as suspension of beach raking or use of symbolic fences can be undertaken over larger distances at low unit costs (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom and Dallmeyer2003). Total restoration may be untenable where too many side effects would conflict with the interests of many stakeholders, but a program of phased restoration may be advantageous (Pethick Reference Pethick, Bodungen and Turner2001).

Restoration approaches are often placed in three or more basic categories based on the degree of human input. Aronson et al. (Reference Aronson, Floret, Le Floc’h, Ovalle and Pontanier1993) use the terms restoration, rehabilitation, and reallocation to distinguish the increasing human role. Lithgow et al. (Reference Lithgow, Martínez and Gallego-Fernández2014) use the terms conservation, restoration, and rehabilitation. Swart et al. (Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001) use three categories they call wilderness, arcadian, and functional. Within each of these categories, stakeholders may have alternative perspectives on the way landscapes may be appreciated and valued, such as ethical, aesthetic, or scientific (van der Windt et al. Reference van der Windt, Swart and Keulartz2007). The key features in the wilderness approach are biological and physical processes such as erosion, sedimentation, decomposition, migration, and predation that operate in a self-regulating system with little or no human influence. This approach requires relatively large areas to allow the physical and biotic free interplay (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001). Although the overall goal may be to emulate aspects such as structure, function, and diversity, these components may not be part of the initial restoration effort, and direct management should be restricted as much as possible (Turnhout et al. Reference Turnhout, Hisschemöller and Eijsackers2004). On sandy coasts, the wilderness approach could be used to convert land covered in pine plantations back to dynamic nature preserves (van der Meulen and Salman Reference van der Meulen and Salman1996). The wilderness approach will be successful if functional interests do not compete and no opposition occurs, and it would need strong advocates or top-down steering methods requiring political ownership of land, finances, or authority if it is implemented in populated areas (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001).

The arcadian approach involves maintaining the landscape as semi-natural and extensively used, with human influence considered a positive element that can enhance biodiversity and create a harmonious landscape (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001). This approach would be appropriate in converting a graded and raked beach that lacks a dune into a more naturally functioning beach/dune system, with value for nature-based tourism rather than more consumptive forms of tourism. Aesthetic appreciation is important in this approach.

The functional approach involves adapting nature to the current utilization of the landscape, including urban functions, where nature is often characterized by species that follow human settlement (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001). The functional approach may be necessary where dunes occur on private properties, and successful restoration may require compatibility with resident conceptions of landscape beauty that may be based on patterns, lines, and colors rather than on the apparent disorder of nature (Mitteager et al. Reference Mitteager, Burke and Nordstrom2006). Horticulture, rather than restoration, may have to be accepted as the means to retain a desired image in spatially restricted environments (Simpson Reference Simpson2005). Economic considerations are critical in this approach.

The degree of rigor used to restore landforms and habitats and the metrics used to assess success will differ based on the approach taken. Ideally, criteria by which success of ecological restoration projects can be judged include (1) sustainability without continuous management; (2) productivity or increase in abundance or biomass; (3) recruitment of new species; (4) soil and nutrient buildup and retention; (5) biotic interaction; and (6) maturity relative to natural systems (Ewel Reference Ewel and Jordan1990). Some of these criteria (especially 1 and 6) may be unachievable in systems that have undergone considerable alteration by humans. One challenge in assessing the value of restored coastal resources is to determine the metrics that characterize the health and services provided by the ecosystem and the degree of departure from and rate of natural recovery to conditions that would have prevailed in the absence of the human modification (Peterson and Lipcius Reference Peterson and Lipcius2003). A major problem is that restored environments cannot be expected to evolve as they would have in a natural system that occurred in the past because conditions outside their borders have changed from that past state in response to continued human inputs.

1.7 The Elusiveness of a Time-Dependent Target State

Much attention is now focused on resilience. In a geomorphic sense, resilience can be defined as the ability of a geomorphic system to recover from disturbance and the degrees of freedom to absorb or adjust to disturbance (Stallins and Corenblit Reference Stallins and Corenblit2018). Resilience is used in many scientific fields, often ambiguously, causing confusion over terminology and leading to different interpretations, even within the same scientific discipline (Kombiadou et al. Reference Kombiadou, Costas, Carrasco, Plomaritis, Ferreira and Matias2019). Resilience of a dune can be defined as recovery to a pre-disturbance height and volume (Houser et al. Reference Houser, Wernette, Rentschlar, Jones, Hammond and Trimble2015), which is compatible with traditional engineering attitudes about stability (Stallins and Corenblit Reference Stallins and Corenblit2018). This definition is likely to be readily acceptable in developed communities, where stability is often the management goal (Jackson and Nordstrom Reference Jackson and Nordstrom2020). Resilience can also be defined as the potential to recover around a different set of interactions that may not result in a return to the original state (Stallins and Corenblit Reference Stallins and Corenblit2018). These two definitions represent alternative ways to manage developed systems, and the meaning of resilience must be better defined in geomorphic and ecologic terms before it can be operationalized in specific management strategies. It can be argued that recovery after perturbation should not be restricted to regaining pre-disturbance morphological dimensions but should be viewed in terms of reorganization and adaptation in order to regain or maintain functions (Kombiadou et al. Reference Kombiadou, Costas, Carrasco, Plomaritis, Ferreira and Matias2019). Unfortunately, arguments indicating that allowing natural processes to prevail makes coasts more resilient are relatively easy to document but may be of little value in guiding management efforts on developed coasts, where landform mobility places buildings and infrastructure at risk (Jackson and Nordstrom Reference Jackson and Nordstrom2020). Coastal resilience must refer to the capacity of the combined socioeconomic and natural systems to cope with disturbances, including sea level rise, extreme events, and human impacts, with enhancement of socioeconomic resilience often coming at the expense of natural resilience, and vice versa (Masselink and Lazarus Reference Masselink and Lazarus2019).

The landforms on low-lying coasts, such as barrier islands, are created and shaped by the very processes that threaten infrastructure on them, restricting options to provide protection to human structures using natural solutions (Jackson and Nordstrom Reference Jackson and Nordstrom2020). Framing small-scale soft coastal protection strategies as “working with nature” is also counterintuitive where the new landforms and habitats are temporary and cannot maintain themselves over time without ongoing human assistance (Gesing Reference Gesing2019). The implications are that restoration efforts in locations where natural dynamism is desired, such as dune reserves, may have to differ substantially from efforts in developed areas, where dynamism must be limited. We agree with Alexander (Reference Alexander2013) and Masselink and Lazarus (Reference Masselink and Lazarus2019) that resilience is a multifaceted concept that is adaptable to alternative uses and contexts in different ways but not one that is readily used as a model or paradigm or well defined in management contexts.

The many changes that occur to the coastal landscape through time make the selection of a target state for restoration difficult (Corlett Reference Corlett2016) and leave the appropriate restoration approach up for considerable debate (e.g., Delgado-Fernandez et al. Reference Del Vecchio, Jucker, Carboni and Acosta2019; Arens et al. Reference Arens, de Vries, Geelen, Ruessink, van der Hagen and Groenendijk2020; Creer et al. Reference Creer, Litt, Ratcliffe, Rees, Thomas and Smith2020; Pye and Blott Reference Pye and Blott2020). Reconstruction of beach and dune conditions in the past reveals a series of states (Piotrowska Reference Piotrowska, van der Meulen, Jungerius and Visser1989; Provoost et al. Reference Provoost, Laurence, Jones and Edmondson2011), all of which have characteristics that would be favored by a percentage of stakeholders. Human influence can be documented well into the past in Europe, and a target state for a natural system could be based on conditions many millennia ago or at a more recent time, such as just prior to the industrial revolution. In the Marche region of central Italy, many of the sandy barriers that are eroding and require shore protection efforts are not representative of the gravelly and sandy pocket beaches that alternated with active cliffs until about 2000 BC (Coltorti Reference Coltorti1997). The sandy barriers resulted from delivery of sediment following deforestation caused by human use of the hinterlands. A landscape prior to Roman influence would be different from either a landscape prior to the industrial revolution, when the sediment-rich beaches and foredunes were largely unaffected by human construction at the coast, or a modern landscape, when beaches and dunes are spatially restricted and eroding as a result of dam construction.

Studies of the Americas point out the problem of using the pre-Columbian landscape as the target state for a natural environment, given new evidence for the many alterations made by Native Americans (Denevan Reference Demirayak, Ulas, Salman, Langeveld and Bonazountas1992; Higgs Reference Higgs2006). Specification that restoration must resemble an original, pre-disturbance state can become an exercise in history or social science. Even if an initial state could be specified for a region, it is rarely possible to determine what the landscape or ecosystem looked like, how it functioned, or what the full species list looked like (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Floret, Le Floc’h, Ovalle and Pontanier1993). Historical data provides useful background information, but past states may not provide appropriate restoration goals for a contemporary dynamic environment subject to a new suite of processes (Falk Reference Falk1990; Hobbs and Norton Reference Hobbs and Norton1996; Wiens and Hobbs Reference Wiens and Hobbs2015). The reference model for restoration should describe the approximate condition the site would be in if degradation had not occurred; this is not the same as the historic state, which does not account for the system to change during intervening conditions (Provoost et al. Reference Provoost, Laurence, Jones and Edmondson2011: Gann et al. Reference Gann, McDonald and Walder2019). Analytical approaches must acknowledge past conditions but also future scenarios when key process drivers may change (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Doughty, Lowe, Cooper, Sloane and Liza2020).

Populations, communities, or ecosystems identified for restoration may now be in alternative states, and restoration targets are biased by shifting historical baselines (Peterson and Lipcius Reference Peterson and Lipcius2003). Adherence to specific standards based on native reference ecosystems may be an unattainable target for an increasingly large number of restoration sites (Higgs et al. Reference Higgs, Harris and Murphy2018), and restoration goals may need to include novel regimes because of changing environmental and socioeconomic conditions (Jentsch Reference Jentsch2007). Beaches and dunes vary greatly in size, location, and surface cover and they are inherently dynamic, undergoing cycles of complete destruction and rebuilding over periods of decades. This dynamism implies that adherence to a specific pre-disturbance state may be less important than the opportunity for these landscapes to achieve spatially and temporally diverse transitory states that need not be large.

The impacts of global climate change, sea level rise, and increases in number and intensity of coastal storms introduce a high degree of uncertainty in the way coastal zones will change, and suggestions for achieving desirable restoration states will have to address this uncertainty (Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin and Plattner2013; Wiens and Hobbs Reference Wiens and Hobbs2015; Corlett Reference Corlett2016; Kopp et al. Reference Kopp, Gilmore, Little, Lorenzo-Trueba, Ramenzoni and Sweet2019). The causes of potential coastal changes are reviewed elsewhere (FitzGerald et al. Reference FitzGerald, Fenster, Argow and Buynevich2008; Cazenave and Le Cozannet Reference Cazenave and Le Cozannet2013; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Kopp, Horton, Browning and Kemp2013; Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin and Plattner2013). Our concern is with finding ways to mitigate or adapt to these changes by restoring and managing coastal landscapes in ways that are compatible with ongoing changes introduced by natural processes and human actions. Sea level rise can be assessed through static inundation studies that flood existing topography with projected sea levels or dynamic response studies caused by anthropogenic, ecologic, or morphologic processes that drive coastal landscape evolution (Lentz et al. Reference Lentz, Thieler, Plant, Stippa, Horton and Gesch2016). Beaches and dunes are dynamic, and effects of inundation and erosion will be partly compensated by adjustments within the natural system and human attempts to favor or restrict these adjustments. Our premise is that uncertainty should not deter efforts to accept more dynamism in restoration solutions that allow natural processes some freedom to adjust to change.

Uncertainties may make it difficult to attain definitive goals, so initial goals may need to change as a restored landscape evolves. Adaptive management is a systematic “learning by doing” approach for improving restoration practice and is suggested as the standard approach for any restoration project (Gann et al. Reference Gann, McDonald and Walder2019). Adaptive management provides a formalized framework for moving from goals and objectives through the planning and implementation of management actions, followed by monitoring and analysis to see what happens, and then using what has been learned to adjust the management actions (Wiens and Hobbs Reference Wiens and Hobbs2015).

1.8 Types of Restoration Project

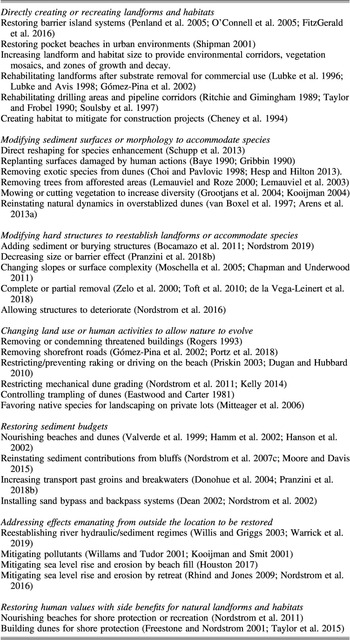

Landforms and habitats can be restored in many ways and at many scales in projects designed explicitly for the targeted environments or in projects that have other objectives, where the restored environments are by-products (Table 1.5). Restoration projects can be conducted where a natural environment has lost so much value that its restoration is considered cost effective or where the existing human environment has so little remaining value that efforts to enhance or protect existing uses are discontinued (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Jackson2007c). Many restoration efforts are attempts to overcome the more damaging actions identified in Table 1.1.

Table 1.5. Ways that landforms and habitats can be restored on beaches and dunes

| Directly creating or recreating landforms and habitats Restoring barrier island systems (Penland et al. Reference Penland, Connor, Beall, Fearnley and Williams2005; O’Connell et al. Reference O’Connell, Franze, Spalding and Poirier2005; FitzGerald et al. Reference FitzGerald, Georgiou and Kulp2016) Restoring pocket beaches in urban environments (Shipman Reference Shipman2001) Increasing landform and habitat size to provide environmental corridors, vegetation mosaics, and zones of growth and decay. Rehabilitating landforms after substrate removal for commercial use (Lubke et al. Reference Lubke, Avis and Moll1996; Lubke and Avis Reference Lubke and Avis1998; Gómez-Pina et al. Reference Gómez-Pina, Muñoz-Pérez, Ramírez and Ley2002) Rehabilitating drilling areas and pipeline corridors (Ritchie and Gimingham Reference Ritchie and Gimingham1989; Taylor and Frobel Reference Taylor, Frobel and Davidson-Arnott1990; Soulsby et al. Reference Soulsby, Hannah, Malcolm, Maizels and Gard1997) Creating habitat to mitigate for construction projects (Cheney et al. Reference Cheney, Oestman, Volkhardt and Getz1994) Modifying sediment surfaces or morphology to accommodate species Direct reshaping for species enhancement (Schupp et al. Reference Schupp, Winn, Pearl, Kumer, Carruthers and Zimmerman2013) Replanting surfaces damaged by human actions (Baye Reference Baye and Davidson-Arnott1990; Gribbin Reference Gribbin and Davidson-Arnott1990) Removing exotic species from dunes (Choi and Pavlovic Reference Choi and Pavlovic1998; Hesp and Hilton Reference Hesp, Hilton, Martínez, Gallego-Fernández and Hesp2013). Removing trees from afforested areas (Lemauviel and Roze Reference Lemauviel and Roze2000; Lemauviel et al. Reference Lemauviel, Gallet and Roze2003) Mowing or cutting vegetation to increase diversity (Grootjans et al. Reference Grootjans, Adema, Bekker, Lammerts, Martínez and Psuty2004; Kooijman Reference Kooijman, Martínez and Psuty2004) Reinstating natural dynamics in overstablized dunes (van Boxel et al. Reference van Boxel, Jungerius, Kieffer and Hampele1997; Arens et al. Reference Arens, Mulder, Slings, Geelen and Damsma2013a) Modifying hard structures to reestablish landforms or accommodate species Adding sediment or burying structures (Bocamazo et al. Reference Bocamazo, Grosskopf and Buonuiato2011; Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom2019) Decreasing size or barrier effect (Pranzini et al. Reference Pranzini, Rossi, Lami, Jackson and Nordstrom2018b) Changing slopes or surface complexity (Moschella et al. Reference Moschella, Abbiati and Aberg2005; Chapman and Underwood Reference Chapman and Underwood2011) Complete or partial removal (Zelo et al. Reference Zelo, Shipman and Brennan2000; Toft et al. Reference Toft, Cordell, Heerhartz, Armbrust, Simenstad, Shipman, Dethier, Gelfenbaum, Fresh and Dinicola2010; de la Vega-Leinert et al. Reference de la Vega-Leinert, Stoll-Kleemann and Wegener2018) Allowing structures to deteriorate (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Roman2016) Changing land use or human activities to allow nature to evolve Removing or condemning threatened buildings (Rogers Reference Rogers1993) Removing shorefront roads (Gómez-Pina et al. Reference Gómez-Pina, Muñoz-Pérez, Ramírez and Ley2002; Portz et al. Reference Portz, Manzolli, Alcántara-Carrió, Botero, Cervantes and Finkl2018) Restricting/preventing raking or driving on the beach (Priskin Reference Priskin2003; Dugan and Hubbard Reference Dugan and Hubbard2010) Restricting mechanical dune grading (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Kraus2011; Kelly Reference Kelly2014) Controlling trampling of dunes (Eastwood and Carter Reference Eastwood and Carter1981) Favoring native species for landscaping on private lots (Mitteager et al. Reference Mitteager, Burke and Nordstrom2006) Restoring sediment budgets Nourishing beaches and dunes (Valverde et al. Reference Valverde, Trembanis and Pilkey1999; Hamm et al. Reference Hamm, Capobianco, Dette, Lechuga, Spanhoff and Stive2002; Hanson et al. Reference Hanson, Brampton and Capobianco2002) Reinstating sediment contributions from bluffs (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Jackson2007c; Moore and Davis Reference Moore and Davis2015) Increasing transport past groins and breakwaters (Donohue et al. Reference Donohue, Bocamazo and Dvorak2004; Pranzini et al. Reference Pranzini, Rossi, Lami, Jackson and Nordstrom2018b) Installing sand bypass and backpass systems (Dean Reference Dech and Maun2002; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson, Bruno and de Butts2002) Addressing effects emanating from outside the location to be restored Reestablishing river hydraulic/sediment regimes (Willis and Griggs Reference Runyan and Griggs2003; Warrick et al. Reference Warrick, Stevens, Miller, Harrison, Ritchie and Gelfenbaum2019) Mitigating pollutants (Willams and Tudor Reference Williams and Feagin2001; Kooijman and Smit Reference Kooijman and Smit2001) Mitigating sea level rise and erosion by beach fill (Houston Reference Houston2017) Mitigating sea level rise and erosion by retreat (Rhind and Jones Reference Rhind and Jones2009; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Roman2016) Restoring human values with side benefits for natural landforms and habitats Nourishing beaches for shore protection or recreation (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Kraus2011) Building dunes for shore protection (Freestone and Nordstrom Reference Freestone and Nordstrom2001; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Gibeaut, Yoskowitz and Starek2015) |

Only a few references are provided here. Additional references are in appropriate chapters where themes are elaborated.

Direct creation of landforms and habitats (Table 1.5) usually involves reconstructing a landform to a specific design shape, followed by planting target vegetation to achieve an end state quickly or by planting pioneer vegetation where time and space are available to allow more mature habitats to evolve naturally at a slower rate. Modifying surfaces of existing landforms to accommodate species requires planting or removing vegetation. These actions can affect large areas and have great impact on the surrounding environment at a relatively low cost.

Changing land use to provide space for nature to evolve (Table 1.5) can result in fully functioning natural environments, especially where human structures that restrict natural processes are removed. This option may be difficult to implement because compensation for loss of previous uses may be costly, and previous users may be reluctant to relinquish control, regardless of compensation. Restoring sediment budgets may be a more palatable alternative to changing land use because it allows natural environments to form seaward of existing structures (Figure 1.2). The new environments will be spatially restricted unless the previous rate of sediment input is exceeded, allowing accretion to occur. Restoring sediment budgets can be the most environmentally compatible method of retaining environments on eroding shores where retreat is not an option, depending on the rate of introduction of the sediment and the degree to which the sediment resembles native materials. Maintaining natural rates of sediment transport can be costly because of the expense of maintaining permanent transfer systems and the difficulty of finding suitable borrow materials that are not in environmentally sensitive areas.

Restoration actions outside the coast (Table 1.5) can have windfall side benefits on beaches and dunes. Reestablishing hydraulic regimes in rivers by removing dams would increase the delivery of sediment to coasts (Warrick et al. Reference Warrick, Stevens, Miller, Harrison, Ritchie and Gelfenbaum2019). Reducing pollutant levels in runoff or in the atmosphere would favor return of vegetation to former growing conditions. Actions taken to restore human use values can have significant side benefits. Nourishing beaches for shore protection or recreation provides space for natural features to form, and building dunes for shore protection provides substrate that natural vegetation can colonize. The barrier against salt spray, sand inundation, and flooding provided by a foredune built to protect human infrastructure allows for survival of a species-rich backdune, even on spatially restricted dunes on intensively developed coasts.

Windfall benefits may accrue regardless of the rationale for the many projects that become de facto restorations. Making the goals of each project broader by identifying these benefits may attract the interest and support of a greater number of stakeholders. A case can be made for projects that restore ecosystem functions rather than a specific species or set of species or a cosmetic landscape surface (Choi Reference Choi, Choi, Park and Yang2007), but in developed systems any change toward a more naturally functioning coastal system that is compatible with human use is desirable.

1.9 Scope of Book

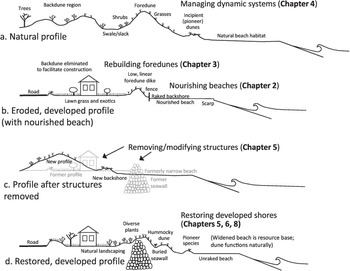

The focus of this book is on developed coasts, where restoration to a previously undisturbed state is not feasible, and arcadian and functional approaches (Swart et al. Reference Swart, van der Windt and Keulartz2001) are the most applicable. The differences between a natural beach (Figure 1.3a) and developed alternatives (Figure 1.3b–d) are obvious. The challenge is to maximize natural features to the extent allowed by natural processes and human demands. The working premise is that any attempt to return a natural system or system component to a more natural state or cause stakeholders to develop a natural landscape ethic is a good thing, unless the attempt is accompanied by more damaging side effects. Tradeoffs may be required in reinstating natural environments in the face of economic constraints, spatial restrictions, or the desires of conflicting interest groups. There may be a need to accept less-than-ideal states for restored environments or to conduct ongoing human efforts to maintain them where existing natural landforms are being altered to accommodate human uses.

Restoration activities can be conducted by participants in the public (government) and private sectors and at any level, from the highest government authority to an individual property owner. Within the private sector, coastal restoration often occurs as a result of mitigation requirements for construction projects that remove or alter coastal habitat. National, state/provincial, and local governments in countries set policies, regulations, and land use controls to guide actions that influence the morphology and ecology of coastal reaches. Funding for projects can be supplied by any participant, but is usually done by higher levels of government for large projects, such as regional beach nourishment operations. Nonprofit organizations have played an increasingly active role in the development of smaller projects to restore beaches and dunes that were lost to extreme events and restore ecological function. These groups can work together in coordinating and providing advice for restoration actions to meet multiple stakeholder interests (Kar et al. Reference Kar, Rhode, Snider and Robichaux2020), especially in lands that are only partially developed and have conservation interest. Private residents can initiate restoration activities on their properties, often guided by public and private sector expertise and self-help documents (Mitteager et al. Reference Mitteager, Burke and Nordstrom2006).

Coastal resources can be restored or maintained despite an ever-increasing human presence, if beach nourishment plays an increasing role (de Ruig Reference de Ruig, Salman, Langeveld and Bonazountas1996; Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Jackson and Kraus2011). Beach nourishment may be a contentious issue because of its cost, finite residence time, and potential detrimental effect on biota (Pilkey Reference Pilkey1992; Nelson Reference Nelson1993; Lindeman and Snyder Reference Lindeman and Snyder1999; Greene Reference Greene2002), but nourishment projects continue to increase in numbers and scope, requiring increased attention to their resource potential (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom2005). The nourished beaches depicted in Figures 1.1 and 1.3b are not ideal, but much can be done to enhance their restoration potential. The types of nourishment projects as currently practiced are identified in Chapter 2, along with evaluations of their advantages and disadvantages, the mitigating and compensating measures used to overcome objections to them, and alternative practices that can make nourishment more compatible with broader restoration goals.

Dune building practices for locations where dunes have been eliminated or reduced in size are identified in Chapter 3. Case studies are provided, including examples of locations where beaches and dunes modified to provide limited human uses have evolved into habitats with greater resource potential than envisioned in original designs. The resulting habitats provide evidence that the principles discussed in subsequent chapters can have achievable outcomes, especially on intensively developed coasts where beaches are narrow and dunes have great significance for shore protection.

Much of the problem of managing beaches and dunes is that a healthy natural coastal system tends to be dynamic (Cooper and McKenna Reference Cooper and McKenna2008; Hanley et al. Reference Hanley, Hoggart and Simmonds2014), but humans want a system that is stable to make it safe, maintain property rights, or simplify management (Nordstrom Reference Nordstrom and Dallmeyer2003; Bossard and Nicolae Lerma Reference Bossard and Nicolae Lerma2020). Managers are beginning to reevaluate the desirability of stabilizing coasts and are examining ways to make stabilized coastal landforms more mobile to enhance sand transfers from source areas to nearby eroding areas, reinitiate biological succession to increase species diversity, or return developed land to a more natural condition (Nordstrom et al. Reference Nordstrom, Lampe and Jackson2007c). Chapters 4 and 5 discuss the tradeoffs involved in restricting or accommodating dynamism in coastal landforms and identify human actions that can be taken to restore natural dynamism, expanding on some of the actions identified in Table 1.5. Chapter 4 evaluates options in locations where restoration efforts are not constrained by preexisting or planned shore protection structures, and many of the issues are in dune fields, such as depicted in Figure 1.3a. Issues in these locations include maintaining or restoring sand supply, encouraging localized destabilization, reducing the impact of nutrient enrichment, optimizing water supply, reinstating appropriate dune woodland, removing nonnative vegetation, recreating or reinvigorating slacks, controlling scrubs, and establishing appropriate levels of grazing (Rhind and Jones Reference Rhind and Jones2009). Human alteration of the landscape in many of these areas should be at a minimum and limited to locations that experience significant human impact (Pye et al. Reference Pye, Blott and Howe2014).

Chapter 5 evaluates options for accommodating natural processes where they have been severely restricted by human structures or where structural solutions would normally be considered appropriate. Accommodation includes altering the effects of shore protection structures to allow for shoreline features to migrate landward (as depicted in Figure 1.3c) or designing strategies that combine natural and structural solutions (as depicted in Figure 1.3d). Rethinking structural approaches is gaining increased attention given the predicted increases in sea level rise and impact of coastal storms and acknowledgment of the need to make coasts more resilient.

The dimensions of natural cross-shore gradients of topography and vegetation are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain as shorelines continue to retreat and people attempt to retain fixed facilities landward. The kinds of cross-shore environmental gradients achievable under spatially restricted conditions (e.g., Figure 1.3d) are identified in Chapter 6, along with a discussion of the tradeoffs involved in truncating, compressing, expanding, or fragmenting these gradients. Chapter 6 underscores the need for municipal governments and private property owners to develop strategies to maximize opportunities where human structures are a dominant feature and retreat from the coast is not presently considered an option.

Restored environments evolve by natural physical processes and by initial and ongoing human actions (Burke and Mitchell Reference Burke and Mitchell2007), and their use by humans will change because of changing human perceptions and needs. Assessments of restored landscapes must consider natural and human processes and landforms as integrated, coevolving systems (Gann et al. Reference Gann, McDonald and Walder2019) requiring integration of the needs of stakeholders and the physical constraints of coastal processes. Chapter 7 identifies differences in stakeholder preferences and some of the compromises required in resolving these differences, focusing on approaches by municipal managers, developers, property owners, environmental interest groups and agencies, engineers and scientists.

A program for beach and dune restoration should include a target state; environmental indicators and reference conditions to evaluate success; realistic guidelines for construction and maintenance; and methods for obtaining acceptance and participation by stakeholders. Chapter 8 discusses how these components can be implemented, with examples of actions that can be taken by municipal managers and private landowners.

A vast array of methods is available to address restoration needs at many different levels of management, from property owner to national government. The number of alternatives and the suitability of each are dependent on local constraints imposed by availability of sediment, space, technical expertise, money, and social and political will. Time is an important consideration because restored coastal environments are expected to change. Restoration plans should be living documents that allow for changing landscape trajectories. Site- and time-specific constraints make it impossible to prescribe a specific solution for individual sites, so we have concentrated on providing the rationale for restoration in generic terms. Local managers must employ concepts and strategies to suit stakeholder needs and capabilities. Despite the large literature on beach and dune restoration, many issues remain to be resolved in future studies. Chapter 9 identifies ongoing research needs.