Rationale

Nutritional interventions to optimise calf growth and well-being in the neonatal and transition periods can have a significant impact on their performance and productivity when they join the milking herd (Davis and Drackley, Reference Davis and Drackley1998). Limited research has been conducted on the effects of EE in dairy calves. Supplemental EE could enhance rumen development and the propagation of the rumen microbial ecosystem that enables calves to derive nutrients from solid feeds, which is vital for calf well-being and performance (Davis and Drackley, Reference Davis and Drackley1998). The incorporation of EE, typically of bacterial or fungal origin, into the diets of mature dairy cattle has been widely researched and found to often be an advantageous strategy to increase the hydrolytic capacity of the rumen and manipulate the rumen microbiome (Beauchemin et al., Reference Beauchemin, Colombatto, Morgavi and Yang2003). Sometimes, this leads to improved feed efficiency and favourable products of fermentation, which consequently produces favourable outcomes for cattle health, production and environmental sustainability (Beauchemin et al., Reference Beauchemin, Colombatto, Morgavi and Yang2003). Hundreds of studies have been published on the effects of EE in adult dairy cattle, which indicate that the use of EE for ruminant production is usually beneficial for feed efficiency and productivity (Arriola et al., Reference Arriola, Oliveira, Ma, Lean, Giurcanu and Adesogan2017; Beauchemin et al., Reference Beauchemin, Colombatto, Morgavi and Yang2003; Meale et al., Reference Meale, Beauchemin, Hristov, Chaves and McAllister2014; Sujani and Seresinhe, Reference Sujani and Seresinhe2015; Tirado-González et al., Reference Tirado-González, Tirado-Estrada, Miranda-Romero, Ramírez-Valverde, Medina-Cuéllar and Salem2021). However, inconsistencies in responses to treatment, which can be attributed to factors such as enzyme source, cultivation method, application technique, dietary interactions, varying dose rates, retention time, pH stability and ionic strength, have meant that the use of EE in the ruminant sector, although under intense research, has not yet become a commonplace feeding strategy (Sujani and Seresinhe, Reference Sujani and Seresinhe2015; Wang and McAllister, Reference Wang and McAllister2002). Undertaking a systematic review of research examining the effects of EE supplementation in dairy calves will allow for the identification of knowledge gaps and quantification of the strength of evidence in favour of their use.

Calf rearing in the dairy industry

Early weaning of dairy calves means that the transition from pre-ruminant to ruminant occurs at a young age, where the need for dairy calves to derive nutrients from solid feeds just weeks after parturition is much greater than their beef suckler counterparts (Drackley, Reference Drackley2008). Artificial rearing of dairy calves is standard practice for modern dairy systems. For a herd being milked through a parlour or robot, rearing calves artificially is undoubtedly more economical and practical than natural suckling, a practice where calves in beef herds or the wild could be left to nurse for up to 14 months (Reinhardt and Reinhardt, Reference Reinhardt and Reinhardt1981). However, being reared away from its dam is challenging for a calf, which is reflected in relatively higher levels of morbidity and mortality in artificial rearing systems (Windeyer et al., Reference Windeyer, Leslie, Godden, Hodgins, Lissemore and LeBlanc2014). Two of the main distinctions between natural and artificial rearing are the length of time the calf is fed milk or milk replacer, and the quantity of milk provided. In European dairy systems, calves are typically weaned from 6 to 12 weeks of age and are often fed a restricted quantity of milk, approximately 10% of their body weight (BW) (Drackley, Reference Drackley2008). In contrast, calves in cow–calf herds are usually weaned much later, from 6 to 14 months of age, and consume approximately 20% of their BW in milk until natural weaning when the dam begins to produce less milk and the solid feed intake of the calf increases to compensate (Enríquez et al., Reference Enríquez, Hötzel and Ungerfeld2011). Limiting the milk intake and weaning age of dairy calves is economically desirable, with solid feeds costing considerably less than whole milk and milk replacer. However, early weaning and restricted milk intake can have negative implications for calf performance; especially if their rumen is insufficiently developed to derive the necessary nutrients from solid feed for maintenance and growth at the point of weaning (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Bach, Weary and Von Keyserlingk2016). Hence, strategies that use EE to enhance feed digestion and rumen development could improve calf productivity and welfare in modern dairy systems.

Neonatal calves

Calves are born with a four-compartment stomach; however, the rumen, reticulum and omasum are underdeveloped and the abomasum makes up approximately 70% of the total digestive tract (Huber, Reference Huber1969). When calves suckle, the reticular groove delivers milk directly from the oesophagus to the omasum, bypassing the rumen and reticulum, enabling milk to be digested most efficiently in the abomasum by autoenzymatic digestion, predominantly by rennin and lactase. The diversity and abundance of enzymes found in the abomasum increase as the calf matures and its diet changes; these enzymes include pepsin, lipases and amylases (Huber, Reference Huber1969). When calves are in the pre-ruminant stage, their digestive physiology is analogous to monogastrics, relying on autoenzymatic digestion rather than the alloenzymatic digestion that occurs in a developed rumen. In contrast to the ruminant nutrition sector, where wide-scale industry uptake of EE as a feeding strategy has been limited by inconsistent responses to enzyme supplementation, EE have been successfully and widely used in monogastrics. This began with Hervey (Reference Hervey1925), who realised an increase in growth rates and final BWs of Leghorn chicks from the dietary inclusion of fungal enzymatic material. Their research acted as a springboard for innumerable studies finding beneficial outcomes for EE use in pigs, poultry and aquaculture, which has subsequently led to the wide-scale use of EE in the monogastric sector (Bedford and Schulze, Reference Bedford and Schulze1998). When considering why monogastric responses to EE are typically beneficial, and ruminant responses are more inconsistent, it is reasonable to postulate that a major factor is because monogastric animals are autoenzymatic digesters (Bedford, Reference Bedford2000). They have no access to the battery of endogenous enzymes provided by the rumen microbiome; therefore, increasing the hydrolytic capacity of their digestive system using EE has a much greater impact on nutrient utilisation and consequently animal performance (Asmare, Reference Asmare2014). Given the physiological similarities between pre-ruminant and monogastric digestive processes, EE supplementation in calves may have greater, and perhaps more consistent, effects than those observed when supplementing mature cattle.

Transitioning from pre-ruminant to ruminant

In calves, the transition from pre-ruminant to ruminant occurs from 4 to 12 weeks of age, when microbial fermentation is initiated in the rumen by the consumption of water and solid feed. Microbial fermentation produces large quantities of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) that stimulate the development of the absorptive epithelium lining the rumen. Increases in rumen volume and musculature occur in response to feed bulk consumed by calves (Drackley, Reference Drackley2008). Butyrate is a short-chain VFA produced by the anaerobic microbial fermentation of carbohydrates. It is considered the most important VFA for gastrointestinal (GI) tract development as it modulates tissue differentiation, function and proliferation, by providing energy to, and mediating the activity of, colonocytes (Leonel and Alvarez-Leite, Reference Leonel and Alvarez-Leite2012). Studies examining the effects of EE supplementation in cattle have found increased total VFA production including an increase in butyrate production (Ranilla et al., Reference Ranilla, Tejido, Giraldo, Tricárico and Carro2008; Tricarico et al., Reference Tricarico, Johnston, Dawson, Hanson, McLeod and Harmon2005; Zilio et al., Reference Zilio, Del Valle, Ghizzi, Takiya, Dias, Nunes, Silva and Rennó2019). If an increase in butyrate production is observed when supplementing dairy calves with EE, improvements in GI tract development, immunity and digestive capabilities could be achieved. Optimising the development of the rumen and post-ruminal tract is one of the greatest challenges when rearing calves and is key to ensuring that they can derive sufficient nutrients from forage and grain-based rations, rather than milk, following weaning.

During the pre-ruminant and transitional stages, the benefits of feeding forages to calves are disputed. The population of cellulolytic bacteria in the rumen cannot increase to sufficient numbers for effective hydrolysis of plant cell walls until the reticuloruminal pH rises to 6.0, which does not typically occur until 10 weeks of age (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Nagaraja, Morrill, Avery, Galitzer and Boyer1987). Before that point, the digestion of cellulose is severely limited, with forage intake potentially limiting voluntary intake via the accumulation of undigested material within the rumen. However, consuming small amounts of forages has been shown to stimulate the increase in rumen pH needed for effective microbial activity, to decrease the risk of subacute rumen acidosis in both pre- and post-weaned calves (Laarman and Oba, Reference Laarman and Oba2011), and to promote rumination and salivation (Pazoki et al., Reference Pazoki, Ghorbani, Kargar, Sadeghi-Sefidmazgi, Drackley and Ghaffari2017). Although microbial colonisation of the GI tracts of calves commences almost immediately after birth (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Fonty and Gouet1988), metagenomic analysis has indicated that microbial populations in the rumen do not stabilise at similar relative abundances to those seen in adult ruminants until 6–16 weeks of age, although this is affected by factors including weaning age and calf weight. However, populations are significantly more dynamic in the first year of life than the years following (Amin et al., Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf, Kinoshita, Tröscher-Mußotter, Dänicke, Camarinha-Silva, Huber, Frahm and Seifert2021). Thus, supplementing young ruminants with EE in the transition period, and the remainder of their first year of life, may have beneficial outcomes for forage digestion, given that the rumen microbiome would be expected to be less well equipped for alloenzymatic digestion than it is later in life (Guilloteau et al., Reference Guilloteau, Zabielski and Blum2009). Even in mature cattle, inefficient digestion of cell walls is one of the greatest limitations to their nutrition, with plant cell wall digestibility under ideal conditions less than 65%, leading to high levels of nutrient excretion given that cell walls comprise 40–70% of the dry matter (DM) content of forages (Van Soest, Reference Van Soest1994).

Exogenous enzyme production and classification

Exogenous enzymes (EE) commonly used in ruminant nutrition can be split into three categories: fibrolytic, amylolytic and proteolytic. Fibrolytic enzymes include cellulases (endoglucanase, exoglucanase, β-glucosidases) and hemicellulases (endoxylanase, β-1,4 xylosidase, glucuronidase, β-mannosidase, galactosidase), which catalyse the hydrolysis of the polysaccharides cellulose and hemicellulose, respectively (Beauchemin et al., Reference Beauchemin, Colombatto, Morgavi and Yang2003). Amylolytic enzymes catalyse the hydrolysis of starch into glucose and include α-, β- and gluco-amylases (Tricarico et al., Reference Tricarico, Johnston and Dawson2008), and proteolytic enzymes (proteases) catalyse the hydrolysis of protein into amino acids (Eun and Beauchemin, Reference Eun and Beauchemin2005). Other EE used in ruminant nutrition include pectinases (esterases, protopectinases, depolymerases), which catalyse the hydrolysis of pectin (Murad and Azzaz, Reference Murad and Azzaz2011), and phytases that catalyse the hydrolysis of phytate to release phosphorus and other phytate-bound molecules such as amino acids and calcium (Humer and Zebeli, Reference Humer and Zebeli2015). The two leading methods of EE production are solid-state fermentation (SSF) and submerged fermentation (SmF), both methods of biotransformation where bacteria (typically Bacillus spp.) or fungi (typically Aspergillus spp., Saccharomyces spp. or Trichoderma spp.), are cultivated on a substrate to produce specific enzymes or mixed fermentation products (Sujani and Seresinhe, Reference Sujani and Seresinhe2015). SSF and SmF can be differentiated by water requirements, with SSF occurring in the absence of free-flowing water and SmF requiring free-flowing water. SSF typically has higher yields than SmF, produces less waste, has lower production costs and has a lower risk of contamination (Jonathan et al., Reference Jonathan, Tania, Tanjaya and Katherine2021). Advances in bioengineering have enabled improved efficiency and decreased cost of enzyme production. Genome editing has allowed for the enzyme producing capacity of microbes, such as Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma reesei to be enhanced. In A. niger, the insertion of the glucose oxidase gene at glaA and α-amylase loci, using CRISPR-HDR, has quadrupled enzymatic production (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Zheng, Yu, Wang and Pan2019), and T. reesei strain AR-766 has been genetically modified to produce large quantities of phytase (EFSA, 2025). Notably, genome editing can produce strains with deleterious characteristics, such as mycotoxin production, which are harmful to both humans and livestock, highlighting the need for robust screening before novel strains are used in food processing or for enzymatic production (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Zheng, Yu, Wang and Pan2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Du, Chen, Takahashi and Liu2020). To obtain enzymes from SSF or SmF, filtration, solvent extraction and purification steps are required, with the enzyme profile of the fermentation products determined by the microbe strain, cultivation method and substrate composition (Jonathan et al., Reference Jonathan, Tania, Tanjaya and Katherine2021). Alternatively, the entire fermentation media including substrate, fermentation products and microbes can be harvested and used as feed additives. However, obtaining a homogenous mixture of these components can be challenging, and when recommended inclusion rates of these types of products are low, varying responses from treatments could be caused by a lack of homogeneity, with the actual concentration of enzymes highly varied throughout the product (Krishna, Reference Krishna2005). This is particularly challenging in SSF, where the lack of water makes agitating the fermentation bed difficult, resulting in a heterogenous physical and chemical environment in the fermentation chamber (Krishna, Reference Krishna2005). The activity of enzymatic products is usually quantified by measuring the amount of product produced by the biochemical reaction that the enzyme catalyses, enabling enzyme activity to be expressed as product produced per unit time, although manufacturers of mixed fermentation products often do not declare enzyme activities (Meale et al., Reference Meale, Beauchemin, Hristov, Chaves and McAllister2014; Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Patel, Usadadia, Rathwa and Prajapati2019). However, the highly controlled laboratory conditions under which enzyme activities are measured are not representative of the conditions of the rumen (Meale et al., Reference Meale, Beauchemin, Hristov, Chaves and McAllister2014). A fibrolytic enzyme that has cellulase activity of 1500 μmol/ml/min at 20°C and pH 7 may have a completely different activity in a rumen at 38°C and pH 6. To overcome this, testing of enzymatic products using the in vitro gas production (GP) technique (Menke et al., Reference Menke, Raab, Salewski, Steingass, Fritz and Schneider1979) can be employed, where the effect of enzyme treatments on digestive efficiency through GP and fibre degradation is measured under conditions similar to those found in the rumen (Meale et al., Reference Meale, Beauchemin, Hristov, Chaves and McAllister2014).

Justification

Research exploring methods to improve dairy calf performance is not novel. There is an abundance of literature examining biological additives including probiotics, prebiotics and secondary plant metabolites, for the propagation of rumen development and digestive tract health in calves in their pre-ruminant and transitional stages (Diao et al., Reference Diao, Zhang and Fu2019). The effects of these have sometimes been beneficial, but they are inconsistent (Diao et al., Reference Diao, Zhang and Fu2019; Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Elghandour, Salem, Yasaswini, Reddy, Reddy and Hyder2020). It is possible that pre- and probiotic additives have similar effects as EE, since microbial propagation increases the endogenous enzyme production in the rumen (Uyeno et al., Reference Uyeno, Shigemori and Shimosato2015). However, if conditions such as pH and rumen outflow are not favourable to microbes in probiotics, their capacity to produce desirable enzymes would be limited or non-existent (Frizzo et al., Reference Frizzo, Zbrun, Soto and Signorini2011). EE supplementation as a feeding strategy for calves, either as a stand-alone treatment or in combination with other additives, may increase the hydrolytic capacity of the rumen, whilst bypassing the need for favourable conditions for microbial colonisation required for probiotics to be efficacious; potentially enhancing the health, welfare and performance of calves. Thus, examination of existing research measuring the effects of EE supplementation in calves will identify any benefits that have already been realised and highlight future research that could be undertaken to further knowledge on the subject.

Materials and methods

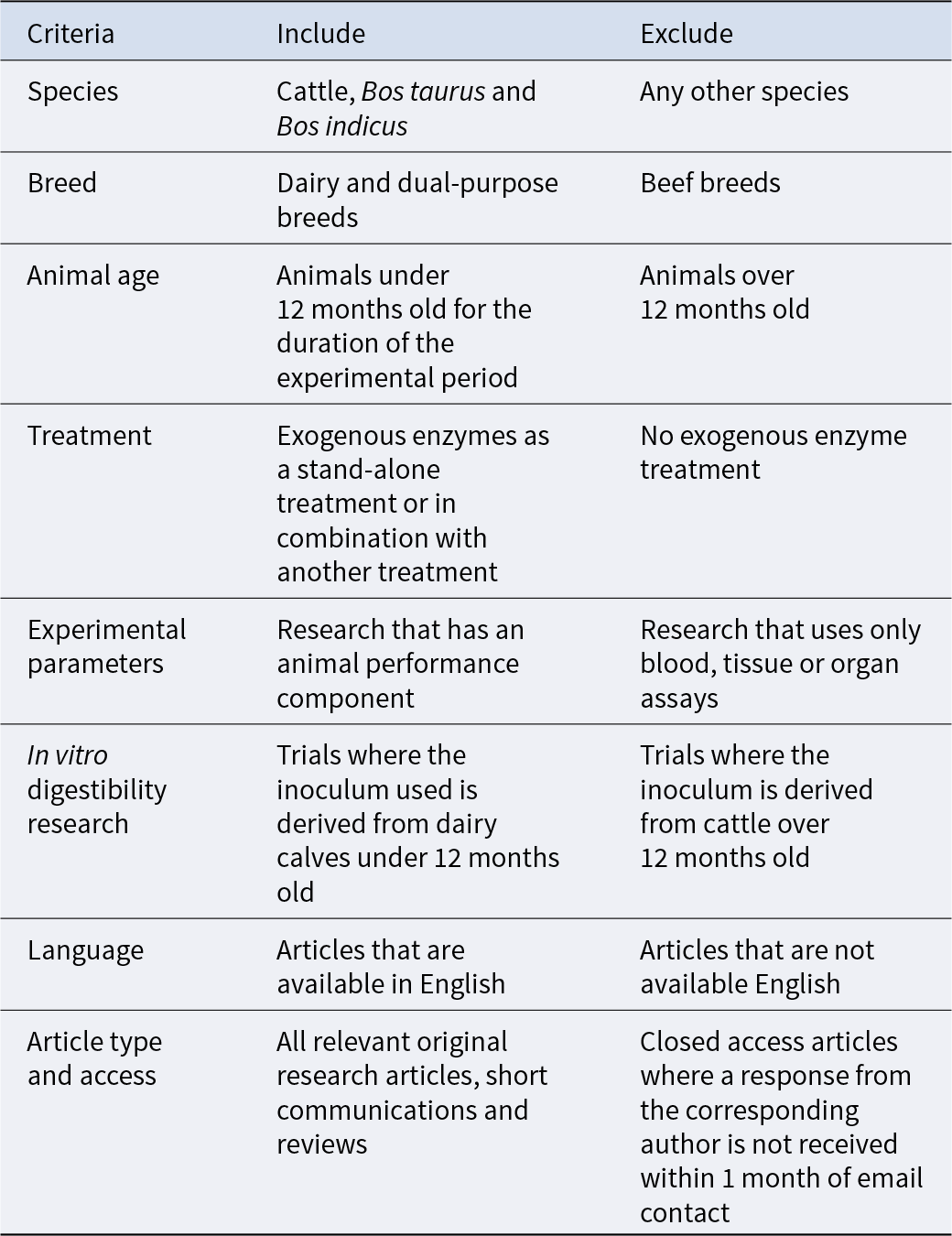

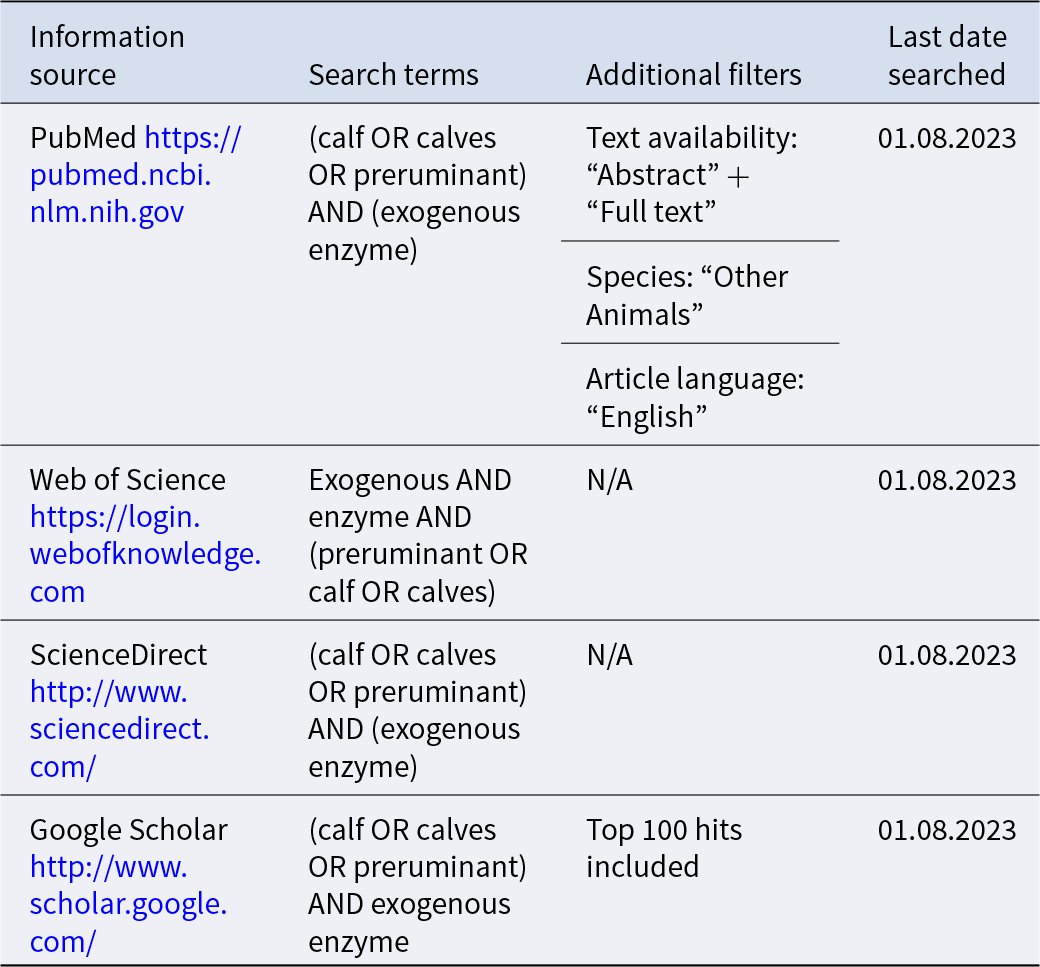

This systematic review has been conducted following the standards set out in the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl and Brennan2021). Prior to database searches, the eligibility criteria listed in Table 1 were selected for the inclusion and exclusion of literature in this review. The information sources, search terms and additional filters used to identify literature are listed in Table 2. Initial literature searches were conducted by the primary reviewer and all articles were imported into EndNote (EndNote X9, 2018). Using the ‘Find Duplicates’ function, duplicate articles were identified and removed from the reference catalogue. The remaining articles were imported into a Microsoft Excel workbook. The primary reviewer screened all papers according to the selection criteria, and 20% of articles were selected using a random number generator and imported into a blank Excel workbook for title screening by the secondary reviewer. The reviewers agreed on 100% of the papers to be included, indicating a robust set of selection criteria and a low risk of bias from the primary reviewer. Whole text screening of all papers selected from title screening was performed by the primary reviewer, with 20% of those randomly selected and imported into a blank workbook for screening by the secondary reviewer. There was 100% agreement between both reviewers on papers to be included in the review, allowing the primary reviewer to proceed with critical analysis. The full dataset for this review, including rejected papers, can be viewed in the supplementary file here: https://doi.org/10.5525/gla.researchdata.1791.

Table 1. Selection criteria for the inclusion of literature in a systematic review of exogenous enzyme use in dairy calves

Table 2. Information sources and search terms used to identify literature for a systematic review of exogenous enzyme use in dairy calves

Results

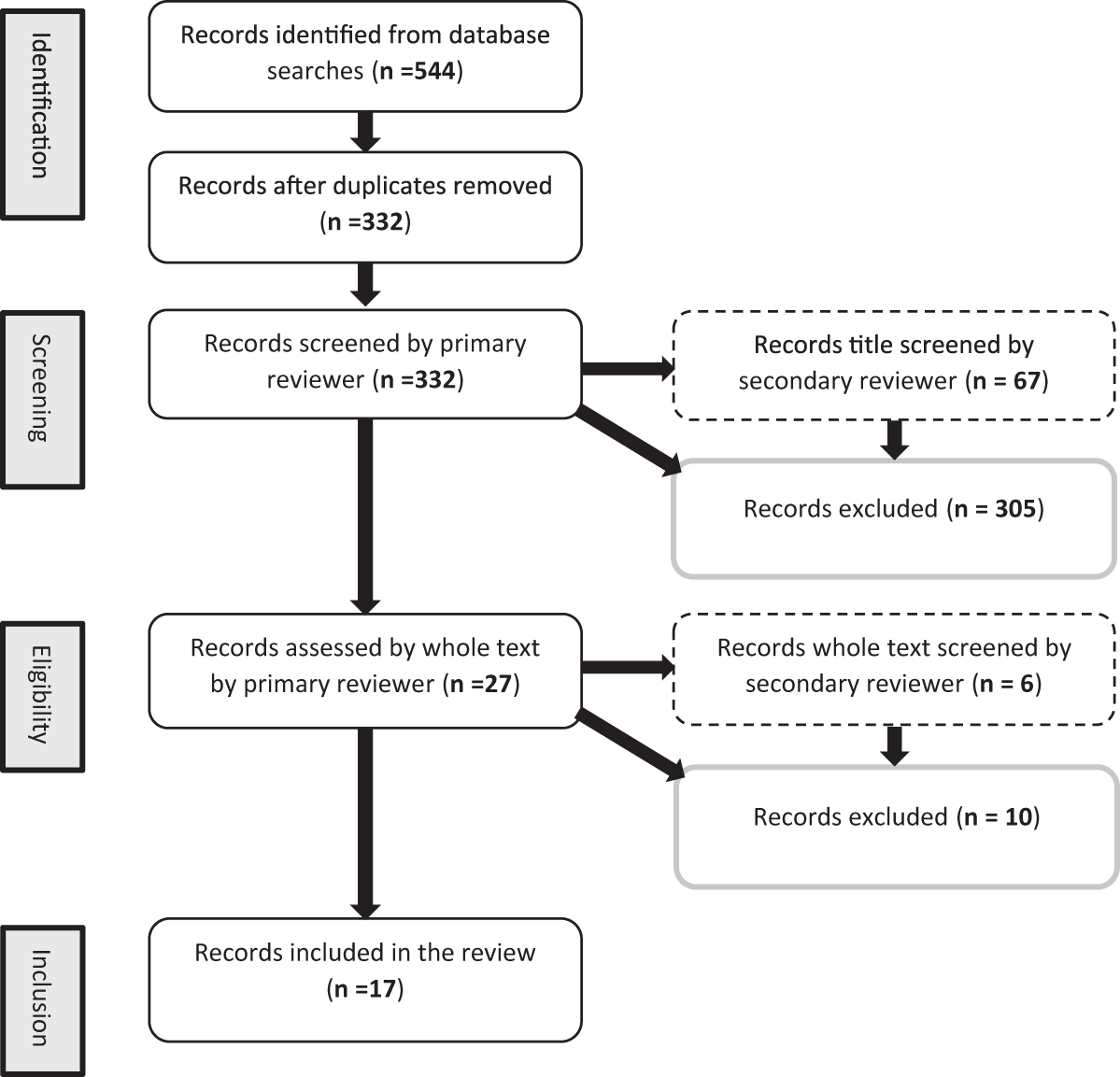

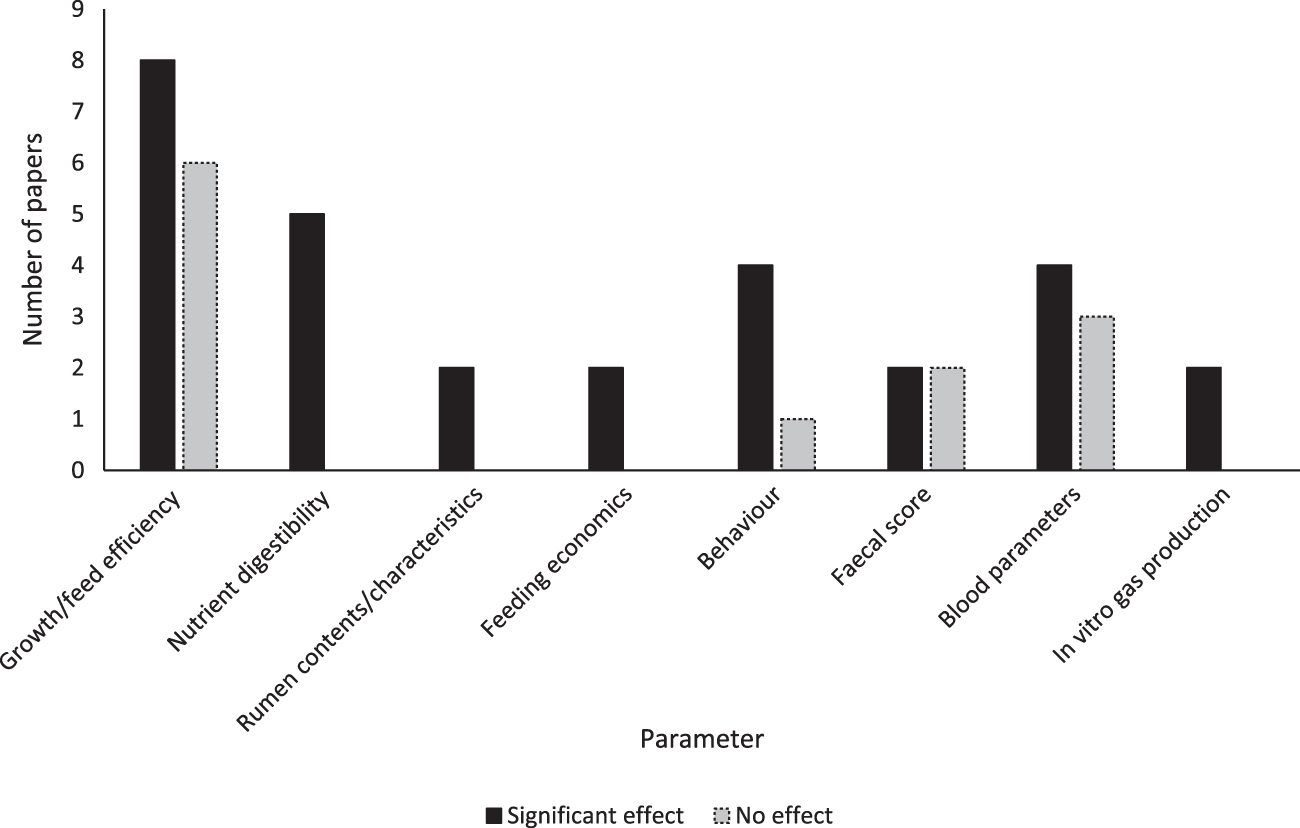

The number of research articles qualifying for each of the identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion stages of this review are shown in Fig. 1. Of the 17 studies that met the eligibility criteria, 15 found a significant effect of EE as an individual treatment, or in combination with another treatment. These effects are summarised in Fig. 2. The treatments used in studies were: four doses of a fungal-derived amyloglucosidase (Diazyme) (Morrill et al., Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970); two mixed enzyme products containing 1437 exo-cellulase, 788 endo-cellulase and 7476 xylanase activities (μmol/ml/min) and 1446 exo-cellulase, 1350 endo-cellulase and 5091 xylanase activities (μmol/ml/min) (Ghorbani et al., Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007); two doses of Bacillus lentus fermentation product containing β-mannanase (Nabte-Solis, Reference Nabte-Solis2008); two doses of phytase (Buendía et al., Reference Buendía, González, Pérez, Ortega, Aceves, Montoya, Almaraz, Partida and Salem2014); two doses of EE + DFM containing 52,000 μmol/g amylase, 28,000 μmol/g protease, 14,000 μmol/g cellulase, 2000 μmol/g lipase, 1000 μmol/g pectinase, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactobacillus spp. (Kocyigit et al., Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Diler, Avci and Ozyurek2016, Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Guler, Diler, Tuzemen, Avci, Ozyurek, Hirik and Kabakci2015); two doses of xylanase (A Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b); two doses of xylanase + S. cerevisiae (Agustín Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b); xylanase at 1.2 UL/ml and xylanase, Aspergillus spp. and Escherichia spp. (Kapadiya et al., Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Patel and Pandya2019b, Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Patel and Pandya2019b); EFE containing 160 μmol/g cellulase and 4000 μmol/g xylanase and EFE and branched chain VFA (BCVFA) containing isobutyrate, isovalerate and 2-methylbutyrate (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020); two doses of EE + DFM containing protease, cellulase, amylase, lipase, pectinase, Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus spp., Enterococcus faecium and Aspergillus oryzae (İlhan and Yanar, Reference İlhan and Yanar2021); an additive containing proteases, lipases, sodium butyrate, organic acids, sorbic acids and silicon dioxide (Szacawa et al., Reference Szacawa, Dudek, Bednarek, Pieszka and Bederska-Łojewska2021); EFE containing 6 × 106 μmol/kg cellulase and 1 × 107 μmol/kg xylanase, and EFE + DFM containing S. cerevisiae, Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium bifidium, Pediococcus acidilactici, Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium (Khademi et al., Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022); two doses of a feed additive (RumEest) containing cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase and S. cerevisiae (Harani et al., Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022); two EFE containing 8000 IU/kg cellulase and 16,000 IU/kg xylanase, and 12,000 IU/kg cellulase and 24,000 IU/kg xylanase (Anil et al., Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022); and products containing 0.055 mg/min/mg xylanase, 0.88 mg/min/mg cellulase and Lactobacillus fermentum, and xylanase, cellulase, L. ferementum and Pediococcus acidilactici (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022). Table 3 presents all variables measured in experiments, experimental treatments and animals, and individual effects realised for each study.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram displaying the number of articles assessed and included in systematic review of exogenous enzyme use in dairy calves.

Figure 2. Variables measured, and significant effects realised in studies examining the effects of exogenous enzymes in dairy calves. Papers were identified by systematic review following the PRISMA (2020) framework.

Table 3. Summary of papers included in a systematic review of exogenous enzyme use in dairy calves

Abbreviations: ADG, average daily gain; EFE, exogenous fibrolytic enzymes; DFM, direct-fed microbials; FE, feed efficiency; BW, bodyweight; PUN, plasma urea nitrogen; XYL, xylanase; GP, gas production; DMD, dry matter disappearance; GPT, glutamic pyruvic transaminase; BCVFA, branched-chain volatile fatty acids; VFA, volatile fatty acids; GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; GHR, growth hormone receptor; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; HMGCS1, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1; NNOB, non-nutritive oral behaviour; DM, dry matter; OM, organic matter; CHO, carbohydrates; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, acid detergent fibre; CP, crude protein; CF, crude fibre; DMI, dry matter intake; OMI, organic matter intake; CPI, crude protein intake.

Discussion

In vitro studies

This review identified two papers that explored the effects of EE in dairy calves in vitro, both measuring environmental and digestibility outcomes. Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Lugo-Coyote, Elghandour, Cipriano, Rodríguez, Odongo and Salem2017a) measured the effect of two doses of xylanase (3 and 6 μL/g DM) on the digestibility, GP and GP kinetics of calf starter concentrates incubated with rumen inoculum obtained from 60-day-old Holstein calves, using the Theodorou et al. (Reference Theodorou, Williams, Dhanoa, McAllan and France1994) pressure transducer technique. Neither dose significantly affected the total GP from incubation nor the GP kinetics. Xylanase treatments of 3 and 6 μL/g DM reduced methane production by 29.4 and 33.9 ml/g DM degraded, respectively, compared with controls over a 72-h incubation, but the difference was non-significant. The higher dose of xylanase significantly decreased CO2 production by 3.77 ml/g DM degraded compared with controls. When performing in vitro GP experiments, it is standard practice to adapt the donor animals to the treatments being trialled for at least 14 days prior to inoculum being collected (Yáñez-Ruiz et al., Reference Yáñez-Ruiz, Bannink, Dijkstra, Kebreab, Morgavi, O'Kiely, Reynolds, Schwarm, Shingfield and Yu2016). The calves used as inoculum donors for the trial of Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Lugo-Coyote, Elghandour, Cipriano, Rodríguez, Odongo and Salem2017a) were not adapted to the treatments, potentially limiting the reliability of the results. In the second in vitro study included in this review, the same group, Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b), trialled the same doses of xylanase as well as two doses of xylanase in combination with two doses of S. cerevisiae (3 μl/g XYL + 2 mg/g SC and 6 μl/g XYL + 4 mg/g SC) using the Theodorou et al. (Reference Theodorou, Williams, Dhanoa, McAllan and France1994) GP technique. In this study, ten Holstein calves were adapted to each treatment from birth for 60 days prior to inoculum collection, and a significant reduction in methane production was found for all doses of xylanase, and the combination of xylanase with S. cerevisiae yielded the lowest proportional methane production of 9% of total gas produced. A significant increase in the rate of GP was realised from xylanase addition, indicating enhanced digestion speed. Xylanase in combination with S. cerevisiae significantly decreased total GP without decreasing the DM disappearance of feedstuffs compared to controls, suggesting a more efficient fermentation pathway. Agustín Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b) postulates that the proportional reduction in methane achieved by treatments could be due to the stimulation of reductive acetogens producing acetate from hydrogen and CO2, limiting the availability of hydrogen for methane production by methanogens. Confirmation of this theory would have been possible if the VFA profile of fermentation fluid post-incubation had been analysed. The results of Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b) suggest that EE might enhance feed digestibility and reduce the environmental impact of dairy calves, although in vivo validation would be required to verify this.

The low yield of studies this review has identified that employ in vitro methods to investigate EE highlights the limitations of such techniques in calves. In vitro digestibility trials are common and valuable methods to explore the utility of feed additives prior to in vivo studies in ruminants. Although laboratory-based, the techniques require donor animals for microbial inoculum. In mature cattle, these donor animals are typically fistulated, meaning they can be used to collect rumen contents for innumerable in vitro studies. However, for in vitro studies examining the effects of feed additives in calves, fistulation of donor animals is problematic given the rapidly changing physiology of calves, which leaves euthanasia and stomach tubing as options for obtaining rumen contents from calves, making such studies less accessible both ethically and practically. The study of Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b) had a robust design, adapting ten calves per treatment as donor animals for in vitro trials. However, in vitro effects do not always translate into animal studies and Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Kholif, Elghandour, Camacho, Cipriano, Salem, Cruz and Ugbogu2017b) concludes that further in vivo trials are required. Considering the number of calves adapted to each treatment in the study, the sample size would have been large enough to obtain meaningful results for in vivo parameters during the 60-day period the calves were fed EE, prior to inoculum collection. Unfortunately, research resources are not infinite and there may have been no scope to collect extra data in this study.

Growth and feed intake

EE as single treatments

This review identified eight studies that measured the effect of EE as a stand-alone treatment on the growth and feeding performance of dairy calves, with five of these studies using exogenous fibrolytic enzymes (EFE) as a treatment. Supplementing calves with EFE early in life could enhance their physiological capacity for plant polysaccharide digestion and be beneficial for growth and performance in both pre- and post-weaning stages. However, Ghorbani et al. (Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007) trialled two EFE products neither of which had an effect on calf weight gain, feed intake or feed efficiency. EFE1 was trialled at an inclusion rate of 0.6 ml/kg DM starter and contained exo-cellulase, endo-cellulase and xylanase activities of 1437, 788 and 7476 μmol/ml/min, respectively; EFE2 trialled at an inclusion rate of 1.9 ml/kg DM starter and contained exo-cellulase, endo-cellulase and xylanase activities of 1446, 1350 and 5091 μmol/ml/min, respectively. Kapadiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Patel and Pandya2019b) measured the effect of feeding calves xylanase with enzyme activity of 1.2 U/ml at an inclusion of 50 ml/kg feed and Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) measured the effect of feeding an EFE with cellulase and xylanase activities of 6 × 106 U/kg and 1 × 107 U/kg respectively at an inclusion of 2 g/d. Neither study realised a significant effect on calf weight gain, feed intake or feed efficiency from treatments and calves treated with EFE in the study of Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) had significantly decreased heart girth and body barrel measurements.

In the trial of Ghorbani et al. (Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007), where the effects of two EFE products were measured using six Holstein calves per treatment, from birth for an experimental period of 84 days; enzyme treatments containing cellulase and xylanase at doses of 0.6 and 1.9 ml/kg DM feed were administered in starter concentrates from birth, and both EFE treatments ceased at day 56. Given that neonatal calves will consume little to no concentrate in the first 2 weeks of life, a more reliable method to ensure each calf consumes its treatment would be to administer the EE with milk, at least until the calf is eating consistent amounts of starter. Ghorbani et al. (Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007) do not justify cessation of enzyme treatments at weaning; since calves rely solely on the effective digestion of solid feeds when milk is withdrawn, more pronounced effects of enzymes could be observed in the post-weaning period. The authors suggest the lack in efficacy of the treatments could be due to the enzyme actions being solely against cell wall components. Indeed, cellulases and xylanases predominantly hydrolyse cellulose and hemicellulose; however, calves in this study were not offered forage throughout and the starter concentrate fed was barley and soy based, meaning there was limited dietary fibre for EFE to enhance the digestion of.

Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) also administered EFE to neonatal Holstein calves in starter feed for a period of 84 days. Wheat straw was soaked in water containing EFE prior to being included in the starter ration. This is a novel method of enzyme application, whilst moisture is required for enzyme activation, soaking a substrate may limit enzyme attachment, as well as cause some of the sparse soluble nutrients present in the straw to be lost, potentially decreasing its nutritive value. The study found no effect of EFE treatment on average daily gain (ADG) or feed intake but observed a significant decrease in heart girth and body barrel of calves fed EFE-treated straw. Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) suggest that increased retention time of EFE-treated straw may have limited the absorption of minerals required for skeletal growth, causing a decrease in body variables. However, the experimental procedure states that all calves were fed a basal starter containing 7% chopped wheat straw; it would be expected that calves fed straw that had been treated with EFE would have higher rumen outflow rate from increased neutral detergent fibre (NDF) digestibility. Calves can sort their feeds, so it is possible that soaking wheat straw with EFE increased its palatability leading to increased intake, although composition of daily orts would be required to investigate this. Regardless, feeding young calves structural carbohydrates can aid in rumen development and prevent acidosis from excess non-structural carbohydrate intake. The fibrolytic microbial community in the rumen develops later than the sugar and starch digesting microbes, limiting the ability of calves to clear forages from the rumen (Drackley, Reference Drackley2008). Thus, feeding EFE in a diet containing straw should increase outflow rather than retention time, providing that the treatment and control calves had the same intake of straw; hence, the finding of decreased body barrel could be linked to lower rumen fill.

Kapdiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Lunagariya and Patel2019a) measured the effect of pretreating Napier grass with xylanase before feeding it to 5-month-old Friesian × Kankrej calves, and a non-significant increase was observed for feed efficiency. Notably, Kapdiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Lunagariya and Patel2019a) used only four calves per treatment. A power analysis by Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) estimates that a sample size of 12 calves per treatment, α = 0.05 and power = 0.80, is required to identify changes in primary response variables including growth and feed intake in calf trials. Thus, the number of calves used by Kapdiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Lunagariya and Patel2019a) would have limited the likelihood of detecting changes in calf performance, should they have been present.

The studies of Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) and Anil et al. (Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022) both found positive effects of EFE supplementation on the growth performance of dairy calves. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) found significant increases in ADG and feed efficiency from supplementing 15-day-old Holstein calves with 1.83 g/d EFE containing cellulase and xylanase activity of 160 and 4000 U/g, respectively, over a 75-day period. Distinct from other studies included in this review, treatments were administered to calves in capsules via oesophageal tube. Although this method of administration would not be tenable in most commercial calf rearing units; for scientific studies, it is a more reliable way to ensure each calf receives its designated dose, rather than by applying EE to starters or forage. The post-weaning diet of calves in this study was also made up of 60% alfalfa hay, meaning the EFE had ample dietary fibre on which to work. The enzyme application method and calf diet in this trial offered optimum conditions for EFE to enhance calf performance and, as such, beneficial outcomes were realised. The study of Anil et al. (Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022) measured the effect of EFE on more mature dairy calves than those of Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020). Two preparations of powdered Aspergillus-derived EFE with xylanase and cellulase activities were trialled: EFE1 had xylanase and cellulase activities of 8000 and 16,000 U/kg DM, respectively, and EFE2 had xylanase and cellulase activities of 12,000 and 24,000 U/kg DM, respectively. The powdered enzymes were applied to a total mixed ration (TMR) made up of chaffed rice paddy straw, oat fodder and concentrates, before feeding to 7-month-old crossbred Jersey heifers. Both EFE significantly increased the voluntary feed intake and feed efficiency of calves over a 75-day growth trial. The composition of the TMR fed to calves in this study was predominantly by-product feeds; if EFE can be utilised to increase the digestibility of such feeds, the sustainability of calf production can be improved through efficient use of crop residues from other food production systems.

A single study examining the effect of phytase supplementation in calves was found. Unlike EFE, the action of phytase is well defined; hydrolysing phytate, the main storage form of phosphorus in cereal grains. Dietary phosphorus has been linked to calf growth rates; however, rumen microbial enzymes do not enable the complete hydrolysis of phytate-bound phosphorus, which can lead to poor phosphorus absorption in the small intestine (SI) (Humer and Zebeli, Reference Humer and Zebeli2015). Phytase is regularly used in the diets of monogastrics to enhance animal performance, GI health and nutrient availability (Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Boyd, Koehler, Gould, Li and Patience2019). Increased nutrient availability from phytase supplementation is not limited to phosphorus, with increased bioavailability of other nutrients trapped in phytate-complexes, such as calcium and amino acids, also contributing to improved animal performance (Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Boyd, Koehler, Gould, Li and Patience2019). Buendía et al. (Reference Buendía, González, Pérez, Ortega, Aceves, Montoya, Almaraz, Partida and Salem2014) investigated the effects of applying two doses of phytase, 0.012 and 0.024 g/kg feed, to a sorghum-based ration for Holstein calves. The highest dose of phytase caused a significant increase in ADG of calves, and neither dose affected DM intake (DMI) or feed efficiency, whilst both doses decreased faecal excretion of phosphorus. This highlights the influence of effective phytate hydrolysis, and consequent phosphorus utilisation, on calf growth performance, as well as reducing the amount of phosphorus excreted, which is advantageous given phosphorus can have negative environmental consequences such as eutrophication.

Two studies identified by this review explored the effects of EE with the inclusion of additional ingredients in calf milk replacers on calf growth and performance. Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970) trialled the inclusion of 15 ml Diazyme, a fungal-derived amyloglucosidase, combined with gelatinised corn starch or expanded sorghum grain as an alternative energy source to glucose in milk replacer. Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008) examined the effect of replacing 50% of whey protein in calf milk replacer with soy protein and β-mannanase. Both studies found that the growth performance of calves was not affected by the combination of specific nutrients with EE that are expected to hydrolyse them. Starch is a considerably more economical energy source compared with glucose or lactose; however, it cannot be utilised efficiently by pre-ruminant calves due to limited amylase production in the abomasum and SI. Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970) found that when including an amylolytic enzyme resistant to denaturation by the pH of the abomasum, with corn starch or sorghum that had been processed to expose intermicellar regions for enzyme action in milk replacer, comparable calf growth performance to that of calves fed conventional milk replacer was achieved. Soy protein is a considerably more economical protein source than whey protein; however, it contains antinutritional factors, such as β-galactomannans, an insoluble non-starch polysaccharide that can inhibit the absorption of nutrients in the SI (Castanon et al., Reference Castanon, Flores and Pettersson1997). Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008) found that replacing half of the whey protein in conventional milk replacer with soy protein and two doses of β-mannanase, 20,000 and 50,000 U/kg, derived from the fermentation products of Bacillus lentus, had no negative effect on feed intake, ADG or skeletal parameters of Holstein calves, compared with calves fed milk replacer containing 100% whey protein. Calves fed soy protein in milk replacer had significantly increased feed intake in the post-weaning period; however, this was independent of enzyme treatment.

The majority of studies utilising EE as a stand-alone treatment found beneficial effects for calf growth or feeding performance, this includes the studies of Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970) and Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008) where equal calf performance to the control can be considered a positive outcome. These trials have demonstrated that EE can be used efficaciously in calves, when an enzyme with known actions is selected to target a specific substrate, for a specific purpose.

EE in combination with another treatment

This review identified nine studies that measured the effect of EE in combination with another treatment on calf growth and performance. Of these studies, six examined the effect of feeding calves EE with direct fed microbials (DFM). Although EE treatment has been shown to positively manipulate the rumen microbiome of mature cattle (Meale et al., Reference Meale, Beauchemin, Hristov, Chaves and McAllister2014), the inclusion of DFM might influence the size and direction of the effects, which could be advantageous in calves, given the impact of rumen development and overall gut health on calf performance. However, four of the six studies measuring the effect of EE + DFM did not find any significant effect of treatment on calf growth or feed intake.

İlhan and Yanar (Reference İlhan and Yanar2021) measured the effect of feeding Brown Swiss calves two doses: 10 and 20 g/d, of a powdered product containing enzymes and DFM. Enzymes included protease, cellulase, amylase, lipase and pectinase; however, their activities were not declared. DFM contained Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus spp., Aspergillus oryzae and Enterococcus faecium. Treatments were administered from birth until six months of age. Calves treated with both doses of EFE + DFM had numerically higher ADG and feed efficiencies, with calves on the lower dose achieving a feed efficiency 64.2% higher than control calves. However, this was not statistically significant suggesting that the study was underpowered.

As well as in the stand-alone EFE treatment trialled in the study of Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022), the effect of EFE + DFM containing S. cerevisiae, Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium bifidium, Pediococcus acidilactici, Bacillus subtilis and Enerococcus faecium on calf growth and feed intake was measured. No increases in ADG, feed intake or efficiency were observed. However, calves fed EFE + DFM did not have the significantly decreased heart girth or body barrel that was observed in calves fed only EFE-treated straw. Interestingly, Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) trialled DFM without EFE as a treatment, which resulted in significant increases in ADG, total BW and feed efficiency. These results suggest that the effects of EFE when combined with DFM might inhibit beneficial growth and feeding performance outcomes from DFM treatment. Calves fed EFE and EFE + DFM had numerically lower feed intakes, which could have caused poorer growth performance. The results of Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) indicate that feeding dairy calves DFM and straw pretreated with EFE is not beneficial for calf growth or feed efficiency. Kapadiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Patel and Pandya2019b) also trialled the effect of combining an EFE treatment with DFM containing Aspergillus spp. and Escherichia spp. on the growth and feed efficiency of 5-month-old Friesian × Kankrej calves. Similar to the outcomes of the stand-alone EFE treatment, EFE + DFM led to numerical improvements in calf ADG and feed efficiency. Had the trial used more than four calves per treatment, greater evidence for the efficacy of treatments would be available.

Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Guler, Diler, Tuzemen, Avci, Ozyurek, Hirik and Kabakci2015) trialled the effects of two doses of EE + DFM on the growth and feed efficiency of Brown Swiss and Holstein Friesian calves, from birth until 6 months of age. The EE used in this trial is referred to as fibrolytic; however, its activity was predominantly amylolytic and proteolytic: 52,000 U/g amylase; 28,000 U/g protease; 14,000 U/g cellulase; 2000 U/g lipase; 1000 U/g pectinase; the DFM contained S. cerevisiae and Lactobacillus spp. Calves were split unevenly between control (n = 11), 10 g/d (n = 7) and 20 g/d (n = 8). This uneven allocation to treatment is not clarified; calf mortality is a plausible cause. The study used 16 Brown Swiss and 10 Holstein Friesian calves, and the author states that calves were randomly allocated to treatment; however, the breed of calves in each treatment is not declared. Unsurprisingly, significant differences were found between BWs and measurements of Holstein Friesian and Brown Swiss calves. However, no significant differences for ADG, body measurements or feed efficiency were observed from treatments. Calves fed 10 g of EE + DFM had numerically higher weight gains and body measurements than control calves throughout the trial. However, without knowing the breeds of calves in each treatment, it is impossible to know whether these increases were due to breed or treatment. Although obtaining a sufficient number of calves close enough in age may have been the cause of using two breeds in this study, breed differences between Holstein Friesian and Brown Swiss calves make ascertaining any conclusions about the efficacy of EE + DFM difficult. However, in a further study, Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Diler, Avci and Ozyurek2016) goes on to trial the 10 g/d EE + DFM on a uniform sample of calves – Brown Swiss × Eastern Anatolian Red, from birth until 3 months of age. In this study calves fed EE + DFM had significantly greater weights at weaning and 3 months old, significantly improved feed efficiency between birth and weaning, and a significant increase in front shank circumference compared with control calves. Given the numerical increases in weight gain and body measurements observed by Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Guler, Diler, Tuzemen, Avci, Ozyurek, Hirik and Kabakci2015), it is likely the EE + DFM treatment was effective, but breed differences confounded the result. When utilising calves of the same lineage, Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Diler, Avci and Ozyurek2016) observed significant improvements in the growth and feed efficiency of calves fed 10 g/d EE + DFM. This highlights the importance of minimising variations, such as breed in calf trials, whereby confounding factors can mask the efficacy of experimental treatments.

Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022) trialled the effects of two doses of RumEest-ESF (Neospark drugs and chemicals ltd), a product containing active S. cerevisiae at 5 × 109 CFU/g and cellulase, xylanase and β- glucanase, on the growth and feed efficiency of 5-month-old Jersey × Sahiwal calves. Eight calves per treatment were fed 0, 10 or 15 g/d RumEest-ESF, applied to concentrate feed an hour before feeding, whilst calves had ad lib access to hybrid Napier grass. A positive dose–response from treatment was observed, with calves administered RumEest-ESF having significantly increased ADG and total weight gain. There was a non-significant improvement in feed efficiency with increasing dose, suggesting that the combination of yeast and EFE may improve the digestibility of feedstuffs, possibly through the propagation of the rumen microbiome and release of cell-bound sugars and proteins, leading to the significant improvements observed for calf growth.

This review identified a single study that used EFE as a component of a silage additive. Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022) ensiled sugar cane tops with EFE containing xylanase and cellulase activities of 0.055 and 0.88 mg/min/mg respectively, and two types of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) inoculum from Lactobacillus fermentum and Pediococcus acidilactici, for 30 days prior to feeding to 8-month-old Karan × Friesian calves. The use of EE as silage additives for forages fed to mature cattle has been reviewed by Taye and Etefa (Reference Taye and Etefa2020), with positive outcomes for growth and milk production in cattle observed from pre-treating silage with EE. Notably, using EE as a silage additive allows for a considerably longer timeframe for enzyme action, compared with direct feeding of EE, allowing for improved hydrolysis of plant polysaccharides and potential synergism between EE and LAB in the anaerobic fermentation phase of ensiling. Thus, positive performance outcomes from enhanced silage quality could be expected. However, in the study of Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022), although EFE + LAB treatments made better silage with a significantly lower pH and higher NDF and acid detergent fibre (ADF) digestibilities, this did not affect the growth or feed intake of calves, compared with control calves fed a silage treated with urea, molasses and NaCl. Unfortunately, EFE and LAB were not trialled as individual treatments in this study, so it is impossible to discern if the beneficial outcomes for silage quality were from the EFE or LAB or synergy between them.

Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) measured the effect of 1.83 g/d EFE, containing 160 U/g cellulase and 4000 U/g xylanase, in combination with BCVFA on calf growth and feed efficiency. The BCVFA contained 2-methylbutyrate, isobutyrate and isovalerate. The production of VFA from feed degradation by microbes stimulates rumen development in calves, with butyrate playing a key role in rumen epithelial cell proliferation, pH homeostasis and ketogenesis (Niwińska et al., Reference Niwińska, Hanczakowska, Arciszewski and Klebaniuk2017). Thus, supplementing calves with EFE to stimulate microbial propagation and feed degradation, and BCVFA to enhance rumen development, could have synergistic effects for calf performance. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) observed that supplementing Holstein calves with EFE + BCVFA through the pre- and post-weaning stages significantly improved DMI, ADG and the feed efficiency of calves. With the results for DMI and ADG numerically higher, and feed conversion ratio numerically lower, than results from calves administered BCVFA or EFE as a stand-alone treatment. A statistical interaction was not observed between BCVFA and EFE, suggesting an additive response. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) demonstrated that supplementing calves with EFE alone or in combination with BCVFA can lead to significant improvements in calf performance. This study yielded more beneficial results than most studies that combined EFE with DFM, suggesting that EFE + BCVFA might be more advantageous for calf performance than EFE + DFM.

Szacawa et al. (Reference Szacawa, Dudek, Bednarek, Pieszka and Bederska-Łojewska2021) measured the effect of a feed additive containing microbial-derived proteases and lipases, sodium butyrate, organic and sorbic acids, and silicon dioxide, on the ADG of Holstein Friesian calves, and concluded that the additive might promote digestive tract maturation and health. A large, but non-significant increase in ADG observed from treatment suggests the study was likely underpowered. Six calves were randomly allocated into control and treatment groups, and each group was housed in a single pen for 7 weeks; the age range of calves at the beginning of the trial was between 4 and 8 weeks old. As calves do not have linear growth curves, having such a large age gap confounds results. Control calves had an ADG of 20 ± 167 g compared with the 231 ± 130 g of calves treated with the feed additive. This result was non-significant, likely caused by the study being underpowered, with growth confounded by age and treatment. The author does not declare individual ages of calves, so it is unclear whether the treatment had an effect or if the calves in that group were just older. A more robust experimental design is required to explore any effect this additive may have on calf performance.

Of the nine studies trialling the effect of EE in combination with another treatment, three found a significant improvement in the growth and or feed efficiency of dairy calves. Notably, most studies observed non-significant improvements in calf performance from treatment, and no reductions in growth or feed efficiency were declared.

Nutrient digestibility

Five of the papers identified by this review measured the effect of EE alone or EE in combination with another treatment, on nutrient digestibility in calves. All papers utilised fibrolytic enzymes and all of them reported significant improvements in the digestibility of NDF. Given that the primary mode of action of EFE is to hydrolyse plant polysaccharides, this indicates that the EFE were performing their intended function, although this did not always translate into improved calf performance. Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) realised an increase in NDF digestibility from feeding calves wheat straw treated with EFE and EFE + DFM, but treatments did not significantly affect the digestibility of ADF, DM, ether extract (EE) or crude protein (CP). Dietary non-fibre carbohydrate levels increased from soaking wheat straw with EFE, suggesting the partial hydrolysis of hemicellulose. The weakening of lignin–cellulose–hemicellulose complexes can facilitate enhanced fibre digestion by rumen microbes, providing greater opportunity for microbial attachment to substrates. However, in the study of Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022), increased NDF digestibility did not enhance calf performance. Similarly, the pretreatment of sugarcane top silage with EFE and two types of LAB inoculum in the study of Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022) significantly increased the NDF and ADF digestibilities of the silage, whilst having no effect on DM, organic matter (OM), CP or EE digestibilities. However, the increase in NDF and ADF digestibility did not significantly affect the feed intake or growth performance of calves. The addition of one of the two types of EFE to neonatal calves starters led to increased NDF digestibility at week 4 in the trial of Ghorbani et al. (Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007). However, this effect was transient and was not observed at week 8. The other EFE trialled, which had higher cellulase and lower xylanase activity, did not affect NDF digestibility for the first 8 weeks of the trial, but when treatment was withdrawn a significant decrease in NDF digestibility was observed. Both Ghorbani et al. (Reference Ghorbani, Jafari, Samie and Nikkhah2007) and Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) used spot faecal sampling for analysis of the digestibility of nutrients. The different digestibilities and passage rates of feeds through the digestive tract make spot sampling an unreliable method of faecal collection for digestibility analysis, especially given the small amount of faeces that can be obtained from manual stimulation of a neonate rectum. Total faecal collection is the gold standard; however, this is not always feasible (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Rebelo, Dieter and Lee2018).

Anil et al. (Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022) found that supplementing weaned calves with two doses of xylanase and cellulase significantly increased the digestibility of OM, DM, ADF, NDF, cellulose and hemicellulose but had no effect on EE or CP. The addition of EFE to a TMR fed to calves increased the voluntary intake of CP, DM and OM, leading to an increase in feed efficiency. This highlights the benefits that can be realised from increasing the hydrolytic capacity of the rumen and stimulating feed intake from the addition of EFE in calf diets. The calves in this trial were weaned, so the utility of enhanced fibre digestion may have been more impactful than in pre-weaned calves on milk and high starch starter feeds. Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022) measured the effect of two doses of EFE in combination with S. cerevisiae, on the digestibility of nutrients in weaned calves. Significant increases were observed in the digestibility of OM, CP, NDF and crude fibre. No effect was observed for the digestibilities of DM, EE, ADF, cellulose or nitrogen-free extract. The preferential hydrolysis of hemicellulose by EFE is highlighted by these results, and fibre degradation may have been enhanced by yeast promoting cellulolytic microbial growth in the rumen. The increased digestibilities from treatments led to significantly higher total digestible nitrogen and digestible CP in the diets of calves whilst DMI was unaffected, indicating that calves fed EFE + S. cerevisiae received a higher plane of nutrition compared to control calves. Both Anil et al. (Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022) and Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022) measured nutrient digestibility using the robust method of total faecal collection over periods of 6 and 7 days, respectively, meaning the results obtained from these trials are more reliable representations of digestibility than studies that use spot sampling of faeces for analysis.

Regardless of application method, dose rate or combination of EFE with a microbial treatment, all papers identified by this review that measured nutrient digestibilities observed a significant increase in NDF digestibility from EFE treatment. This provides strong evidence that EFE are effective at hydrolysing plant cell walls; however, it is difficult to conclude how useful this is in calf diets, given that increased NDF digestibility often did not significantly improve calf growth or feed efficiency. Studies being underpowered could mean that a small effect on growth and feed efficiency from increased NDF digestibility was statistically undetectable.

Rumen characteristics and contents

A successful transition from pre-ruminant to ruminant can be characterised by the development of the rumen and the microbial community that resides therein, enabling VFA and microbial protein production from plant materials, for the growth and maintenance of the weaned calf. Assessing calf rumen contents and characteristics is invasive, requiring stomach tubing or euthanasia, which can be problematic ethically and might explain why only two studies identified by this review quantified these parameters. Nonetheless, these measurements can provide explanations for responses to treatments and are especially valuable for evaluating the effects of EFE, given their proposed mechanism of action is on the hydrolytic capacity of the rumen. Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) stomach tubed neonatal calves fed EFE and EFE + DFM and found a significant increase in molar acetate and the acetate to propionate ratio from both treatments; EFE + DFM also significantly increased propionate concentration. Increased acetate is in accordance with the improved NDF digestibility observed from treating wheat straw with EFE, as acetate is the main product of fibre digestion. Acetate is positively associated with rumen volume increases; however, excessive amounts can negatively affect rumen papillae growth (Kazana et al., Reference Kazana, Siachos, Panousis, Petridou, Mougios and Valergakis2022). Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) found that administering neonatal calves both EFE and EFE + BCVFA significantly increased total rumen VFA concentrations, and the molar concentrations of acetate, propionate and butyrate. EFE and EFE + BCVFA significantly increased the length and width of papillae in the anterior dorsal blind sac. Notably, BCVFA treatment increased papillae length and width elsewhere in the rumen, as well as total rumen weight, but no interaction between EFE and BCVFA was observed for those parameters. Analysis of functional gene expression revealed significant increases in mRNA expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor and growth hormone (GH) receptor in the rumen mucosa of calves treated with EFE and EFE + BCVFA. These results demonstrate that treatments enhanced rumen function and development and are explanatory factors for the improved growth rates and feed efficiencies of calves treated with EFE and EFE + BCVFA.

Feeding economics

The use of feed additives to enhance cattle health and performance is intrinsically linked to farm economics, with producers unlikely to invest in additives that do not provide a return. Replacement heifer rearing is expensive in dairy operations; cost analysis by Boulton et al. (Reference Boulton, Rushton and Wathes2017) demonstrates that the average cost of rearing a heifer from birth to first calving is £1819, with the daily cost of rearing between birth and weaning calculated at £3.14 compared to £1.65 in the post-weaning period. The increase in feed efficiency and performance that has been realised by some studies in this review should lead to improvements in the economics of calf rearing. However, only two studies performed cost analyses. Anil et al. (Reference Anil, Chatterjee, Singh, Yadav and Mohammad2022) found the inclusion of two doses of EFE to a post-weaned calf TMR increased the feed intake and efficiency of crossbred Jersey heifers. This led to a decrease in feed cost of 4.73% and 3.56%, with the lower dose of enzyme causing the greatest decrease in cost, although the authors did not perform statistical analysis on those figures. Considering that plant cell wall digestibility is less than 65% under ideal conditions (Van Soest, Reference Van Soest1994), and developing calf rumens are unlikely to provide ideal conditions for cell wall digestibility, EFE may be used as a method to unlock nutrients in plant polysaccharides, increasing nutrient availability per kg feed, leading to improvements in both performance and the economics of feeding. Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008) found that replacing 50% of whey protein in conventional milk replacer with soy protein and β-mannanase had no negative affect on calf performance and significantly decreased the cost of calf rearing by 30%. This demonstrates the potential efficacy of EE to enhance the nutritive value of alternative feedstuffs for calves, and the economic benefit that can achieve. Performing cost analyses develops the utility of research outcomes to producers and helps relate academic findings into industry applications; however, such analyses would require more robust datasets than the majority of the studies included in this review have produced.

Behaviour

Behaviour is a key indicator of calf health and welfare. Four studies measured the effect of EE supplementation on behavioural parameters, three of which found positive effects. İlhan and Yanar (Reference İlhan and Yanar2021) found a significant increase in the percentage of time Brown Swiss calves fed EFE + DFM spent in recumbency. Rest is an inelastic behavioural requirement for the health and productivity of all cattle, regardless of maturity. Limited resting time and poor growth rates are highly correlated, with healthy calves spending approximately 16 h/d laying down (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Terosky, Stull and Stricklin1999). Thus, the increased recumbency observed from EFE + DFM treatment is positive and could be indicative of calves experiencing positive affective states. If the rumen of calves is not sufficiently developed to derive the nutrient requirements of calves at weaning, they are more likely to experience the negative affective state of hunger and associated behavioural responses, which include decreased resting (Scoley et al., Reference Scoley, Gordon and Morrison2019). Although İlhan and Yanar (Reference İlhan and Yanar2021) did not realise significant improvements in calf growth or feed efficiency, EFE + DFM may have enhanced rumen development, allowing for a smoother transition from milk to solid foods, indicated by increased resting time of calves. Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) also realised an increase in recumbency of calves fed EFE, and both EFE and EFE + DFM treatments decreased the amount of non-nutritive oral behaviour (NNOB) displayed by calves. Calves are highly motivated to suckle, and unrewarded feeding behaviour, such as sucking pen fixtures or cross suckling other calves can be indicative of negative affective states (Jensen, Reference Jensen2003). Cross suckling can also have damaging consequences for the udder health of other animals, especially if the behaviour persists into adulthood (Jensen, Reference Jensen2003). Measuring the amount of time calves spend performing NNOB is a valuable welfare indicator that can readily be performed on farm and in research. The study of Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) was the only trial identified by this review that measured NNOB in calves; their results provide evidence that EFE and EFE + DFM can reduce unrewarded feeding behaviours.

Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Diler, Avci and Ozyurek2016) found that supplementing Brown Swiss × Eastern Anatolian Red calves with EFE + DFM numerically increased the amount of time calves spent in recumbency, although this was non-significant, and no effects were observed for time spent standing, feeding or drinking water. Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022) found no effect of supplementing EFE + S. cerevisiae on the amount of time calves spent recumbent; however, a significant increase in the amount of time calves spent ruminating was observed. In mature cattle, both EFE and yeast treatments have increased rumination time (Salvati et al., Reference Salvati, Júnior, Melo, Vilela, Cardoso, Aronovich, Pereira and Pereira2015; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Takiya, Vendramini, de Jesus Ef, Zanferari and Rennó2016). Rumination is the most readily available marker of rumen function, with the increase in rumen activity from EFE + S. cerevisiae treatment likely correlated with the increases in ADG and BW observed by Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022). Unlike the studies of İlhan and Yanar (Reference İlhan and Yanar2021), Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) and Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Diler, Avci and Ozyurek2016), where calves were enlisted into experiments as neonates, the calves used by Harani et al. (Reference Harani, Van Suryanarayana, Devasena, Reddy and Venkateswarlu2022) were 5–6 months old, so it is not possible to draw conclusions as to the effect of EFE + S. cerevisiae on rumen development from these results. Notably, all studies used visual observations to collect behavioural data, although considerably cheaper than remote monitoring technology, visual observation protocols are vulnerable to human error and subjectivity, as well as the risk of altered animal behaviour caused by a human presence and extrapolating data collected in discrete timeframes over an entire experimental period. Visually collected behaviour data are valuable; however, greater insights into calf behaviour can be achieved using sensors, though the cost of such technology can be prohibitive.

The majority of studies that measured the effect of EE on calf behaviour discovered beneficial outcomes. Calf welfare is an increasingly important topic across social and economic agendas, with consumer concerns surrounding dairy calf rearing frequently featuring in the media. Although further research is required, the studies identified by this review suggest that EFE supplementation could be an effective strategy to improve calf comfort, especially around weaning.

Calf health status

Faecal and respiratory health

Dairy calves are highly susceptible to disease whilst their immune systems are developing. Diarrhoeal diseases, which can be caused by infectious and non-infectious factors, are the most important diseases of neonatal dairy calves, negatively affecting calf performance and welfare, and being responsible for more than half of neonatal calf mortality (McGuirk, Reference McGuirk2008). Four studies identified by this review measured the effect of EE or EE + DFM on the faecal score of calves, a single study measured the effect of EE on respiratory score. Kocyigit et al. (Reference Kocyigit, Aydin, Yanar, Guler, Diler, Tuzemen, Avci, Ozyurek, Hirik and Kabakci2015) and İlhan and Yanar (Reference İlhan and Yanar2021) found a significant reduction in the faecal scores of calves fed EFE + DFM, indicating a lower incidence of diarrhoea. Whilst Khademi et al. (Reference Khademi, Hashemzadeh, Khorvash, Mahdavi, Pazoki and Ghaffari2022) did not find a significant effect of EFE or EFE + DFM on calf faecal score. The probiotic effects of DFM might positively influence the colonisation of microbiota in the calf digestive tract, decreasing its susceptibility to pathogens. The use of DFM as prophylactic and therapeutic treatments for calf diarrhoea has been widely investigated, frequently finding positive effects that suggest they may be a suitable alternative for antibiotics in treating diarrhoeal diseases in calves (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Esposito, Villot, Chevaux and Raffrenato2022). However, the utility of EE, which may also promote gut health and the actions of DFM, whilst improving nutrition allowing for the maintenance of a healthy immune system, has not been thoroughly investigated and requires further research. In the study of Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008), replacing 50% of whey protein in milk replacer with soy protein and β-mannanase did not affect calf faecal or respiratory scores. The anti-nutritional factors present in soy protein can cause nutritional diarrhoea in calves, thus improving their digestion using EE could reduce this risk. Notably, calves fed soy protein without β-mannanase did not have significantly different faecal or respiratory scores, so it is not possible to conclude that enzyme inclusion had a positive impact on calf health.

Blood biochemistry and haematology

Of the seven papers identified by this review that measured blood biochemistry and haematology variables, four found that EE or EE in combination with another treatment, had a significant effect on blood parameters in calves. When determining optimal amylase dose and processing method for starch to be included as an alternative energy source in calf milk replacer, Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970) found that all doses (6, 12, 18 ml Diazyme) induced significant increases in blood glucose levels for several hours when sorghum was gelatinised. Amylase treatment did not significantly affect blood glucose when unprocessed and steamed sorghum were fed to calves. This preliminary experiment enabled Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Abe, Dayton and Deyoe1970) to ascertain that Diazyme was most effective at enhancing the digestibility of gelatinised starch, leading to positive outcomes for calf performance in the subsequent growth trial. Nabte-Solis (Reference Nabte-Solis2008) found that calves fed β-mannanase and soy protein in milk replacer had significantly higher plasma urea nitrogen (PUN), indicative of increased protein availability. Soy protein can cause inflammatory responses; however, haptoglobin levels between calves were similar, indicating that treatment did not induce inflammation.

Kapadiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Patel and Pandya2019b) measured a significant increase in phosphorus and a significant decrease in glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) in the plasma of Holstein × Kankrej calves fed EFE, and a significant decrease in GPT in calves fed EFE + DFM. However, all blood parameters were within normal ranges, and the author states that this means treatments had no adverse effects on the performance of calves. Notably, treatments had no effect on animal performance, as described by Kapdiya et al. (Reference Kapadiya, Shah, Lunagariya and Patel2019a). Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022) did not realise any significant differences in the blood GPT, PUN, calcium, glucose, creatinine or glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase in calves fed sugarcane top silage inoculated with LAB + EFE. In research where by-product feeds with low nutritional content are fed, measuring blood metabolites is a valuable method to identify deficiencies. No such deficiencies were observed by Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Tyagi, Yadav, Sharma and Chauhan2022). In the study of Buendía et al. (Reference Buendía, González, Pérez, Ortega, Aceves, Montoya, Almaraz, Partida and Salem2014), phosphorus retention was increased by feeding Holstein calves phytase. However, this did not affect serum levels of phosphorus; hyperphosphatemia is rare in calves, as phosphorus homeostasis is achieved at greatly varying levels of phosphorus availability (Challa et al., Reference Challa, Braithwaite and Dhanoa1989). The feed additive containing protease, lipase, butyrate, acidifiers and silicon, trialled by Szacawa et al. (Reference Szacawa, Dudek, Bednarek, Pieszka and Bederska-Łojewska2021) did not modulate haematological parameters in calves. No effect on leukocytes, lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes, were observed. It is possible that one or more of the components in the feed additive could influence calf immunity, but the small (n = 3) sample size, and 4-week age disparity between calves, was likely prohibitive for measuring the effects of treatment. Calves administered EFE and EFE + BCVFA in the study of Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) had significantly higher levels of GH and IGF-1 in their blood. This corresponds with the increased gene expression in rumen mucosa and can be associated with the improvements in ADG and higher concentration of rumen VFA, which can positively affect the amount of GH and IGF-1 produced. The study of Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Liu, Guo, Huo, Zhang, Pei and Zhang2020) demonstrated positive effects on calf performance with EFE and EFE + BCVA, and performed thorough analysis to determine treatment actions and interactions. Economic limitations do not always allow such extensive investigations. However, comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of EE at cellular, tissue, organ, organ system and organism levels, will enhance their utility in calf rearing, as well as allowing for more targeted approaches for the development of novel products.

Conclusion

This review highlights the broad spectrum of actions that EE supplementation can have in dairy calves. Papers identified by this review realised beneficial outcomes for calf growth, feed intake, digestibility, behaviour, health, development and the economics of rearing. However, mirroring the research into EE use in mature cattle, there are inconsistencies in the findings of research that has taken place in calves. Although these differences could be caused by lack of statistical power, heterogenous outcomes from EE treatment will not encourage industry uptake, and further research is required to define outcomes from treatments, and the mechanisms of action that underpin these outcomes. Given the need for enhanced sustainability in the dairy industry, the findings of this review suggest that further research to define the efficacy of enzymatic products in calves is warranted.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the University of Glasgow and Alltech as part of a PhD studentship.

Competing interests

No conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was purely desk based so did not require ethical approval.

Data and model availability statement

Full data sets from this experiment are deposited in the University of Glasgow Enlighten repository: https://doi.org/10.5525/gla.researchdata.1791.