Introduction

Burkholderia (B.) cepacia complex (Bcc) is a species complex of closely related gram-negative, catalase-producing, lactose-nonfermenting betaproteobacteria. Reference Mahenthiralingam, Urban and Goldberg1 Bcc belong to a group of organisms termed “opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens” as they are natural inhabitants of water, show relative resistance to chlorine and require minimal nutrients. Reference Falkinham2 The Bcc has been implicated in nosocomial outbreaks linked to various contaminated aqueous medicinal and hygiene products. Reference Alvarez-Lerma, Maull and Terradas3–Reference Vonberg, Weitzel-Kage, Behnke and Gastmeier11 Contamination of such products with Bcc species during manufacture can be persistent and challenging to address because they have natural tolerance to a range of biocides and preservatives, and are adept at biofilm formation. Reference De Volder, Teves and Isasmendi12,Reference Rose, Baldwin, Dowson and Mahenthiralingam13 Bcc species rarely cause clinical infection in the immunocompetent host, though may colonize and cause infection in immune-compromised individuals. Reference Mahenthiralingam, Urban and Goldberg1,Reference Kenna, Lilley and Coward14 The Bcc is of most clinical relevance to patients with cystic fibrosis, where infections can lead to “cepacia syndrome,” with high associated morbidity and mortality. Reference Horsley, Jones and Lord15–Reference Ganesan and Sajjan17

In December 2020, a cluster of eight B. contaminans cases was identified by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) reference unit, based on typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of isolates submitted by hospitals in England. Proactive case finding and examination of held isolates indicated a concurrent substantial increase in cases of another long-standing Bcc cluster, of B. cepacia, first identified in 2010 and previously investigated without resolution. Reference Kenna, Lilley and Coward14 As both clusters were Bcc species with overlap in stakeholders and hypothesized sources, the clusters were investigated concurrently.

This report describes two outbreaks in the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland associated with products contaminated by Bcc species and provides recommendations for investigation and control, based on our experience.

Methods

Initial outbreak investigation

A national “enhanced incident” was declared and an Incident Management Team established with representation from all four nations of the UK overseeing simultaneous investigation of B. cepacia and B. contaminans outbreaks. 18 We hypothesized that a medicinal or hygiene product used in healthcare facilities was the source of each outbreak.

Case definitions

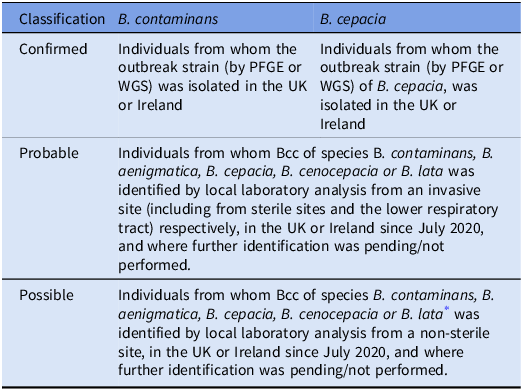

Table 1 describes the case definitions for each cluster based on PFGE typing profile and/or Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) at the AMRHAI national reference laboratory. The probable case definition was chosen to account for variable species identification in local diagnostic laboratories. Cases from the UK and Ireland were included in the investigation as the AMRHAI reference unit also type isolates from hospitals in Ireland if requested.

Table 1. Case definitions for individuals with confirmed, probable, and possible B. contaminans and B. cepacia infections

* These species were chosen based on the Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) identifications for the national clusters

Case detection

Probable cases were identified prospectively from December 2020 to September 2023 through daily interrogation of the UKHSA national Second-Generation Surveillance System (SGSS), with retrospective identification to July 2020. Communications were issued to hospitals in England requesting routine submission of first-time isolates of Bcc from any patient specimen to the AMRHAI and reporting of any cases of Bcc from sterile sites. The investigation team engaged clinicians from hospitals with probable cases to request submission of isolates. In addition, international communications were issued to investigate for a potentially associated cluster or source.

Epidemiological investigation

A trawling questionnaire informed by literature review and expert opinion was designed and deployed to Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) teams from hospitals with probable or confirmed cases to capture clinical history, procedures undertaken, and patient exposures to a range of non-sterile, non-alcohol, aqueous-based medical and hygiene products. Hospitals were requested to list any supply issues or recent changes in products used. Meetings with IPC teams were held to populate, detail, or verify information.

For the B. contaminans outbreak, a unidirectional case-crossover study was undertaken to explore associations between procedures or products and confirmed cases. The case and control periods were defined as 0–9 days and 13–22 days preceding the earliest specimen date for each confirmed case, respectively. Reference Maclure19 A 10-day period was selected based on expert opinion of the incubation period of Bcc infections. Reference Lewis and Torres20 As most infections were invasive, exposure was hypothesized to be direct inoculation or contamination of portals of entry, and it was considered that for the majority the incubation period would be shorter than for individuals with isolates retrieved from non-invasive sites. A “wash-out” period of 3 days was included to minimize risk of misallocation bias. Univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression models were used to calculate crude and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) with a significance level set to 0.05 (see Supplementary Information for detail).

Product testing

Products of potential interest were requested to be submitted for testing at the UKHSA Porton Food Water and Environmental (FW&E) Laboratory. Within the FW&E laboratory, a 27 g aliquot of each sampled product (or less where samples were of a smaller total volume) was aseptically weighed out and sufficient Buffered Peptone Water (BPW) added to provide a 10-1 dilution to reduce the impact of any disinfectant, preservatory, or other inhibitory substance. Swabs were immersed in 100 ml of BPW. Following homogenization in a stomacher for 1 minute, 0.5 ml of the preparation was used to inoculate a blood agar plate which was incubated at 30°C for 48 hours. The remaining sample/BPW homogenate was incubated at 30°C for 5 days before sub-culturing 10 µl onto a cephaloridine fucidin cetrimide agar plate. Oxidase positive colonies were further identified using a Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometry instrument (Bruker). Representative isolates from each sample giving identifications as Burkholderia species were sent to the AMRHAI for species confirmation and typing.

In total, 463 samples of products were tested between December 2020 and July 2021. Samples included ultrasound, lubricating and other gel products, personal care products, products for medicinal or surgical use (including irrigation solutions and surgical scrubs), wipes, electrode pads, transducer probe covers and swabs of equipment, and tap water.

Molecular analysis

Bcc isolates submitted to AMRHAI underwent species-level identification by recA gene sequence clustering. Sequence data were analyzed using BioNumerics software and compared with those of known Bcc type and reference strains using the Neighbor-Joining Method. Reference Kenna, Lilley and Coward14,Reference Turton, Arif, Hennessy, Kaufmann and Pitt21 PFGE for strain characterization was conducted following restriction with XbaI. Reference Turton, Kaufmann, Mustafa, Kawa, Clode and Pitt22 BioNumerics software (v6.1) was used to calculate percentage similarity using the Dice coefficient, with isolates clustered by Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean. Isolates were characterized by comparison with more than 3000 profiles on the UKHSA national database.

Representatives from both clusters were submitted in duplicate to the UKHSA Central Sequencing Service for WGS on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument following QIASymphony extraction and Nextera® XT paired-end library preparation. The resulting FASTQ files were used to a generate a Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)-based analysis using an assembled sequence of one of each cluster (respectively) as a reference strain. Genome assemblies were generated using SPAdes v3.15.2. Multi-locus sequence types (STs) were identified using the scheme of Baldwin et al Reference Baldwin, Mahenthiralingam and Thickett23 , hosted on the PubMLST website (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/burkholderia-cepacia-complex). Sequences of isolates are deposited on the Sequence Read Archive. 24,25

Local investigations

Several hospitals with cases undertook local investigations and independently tested products.

Results

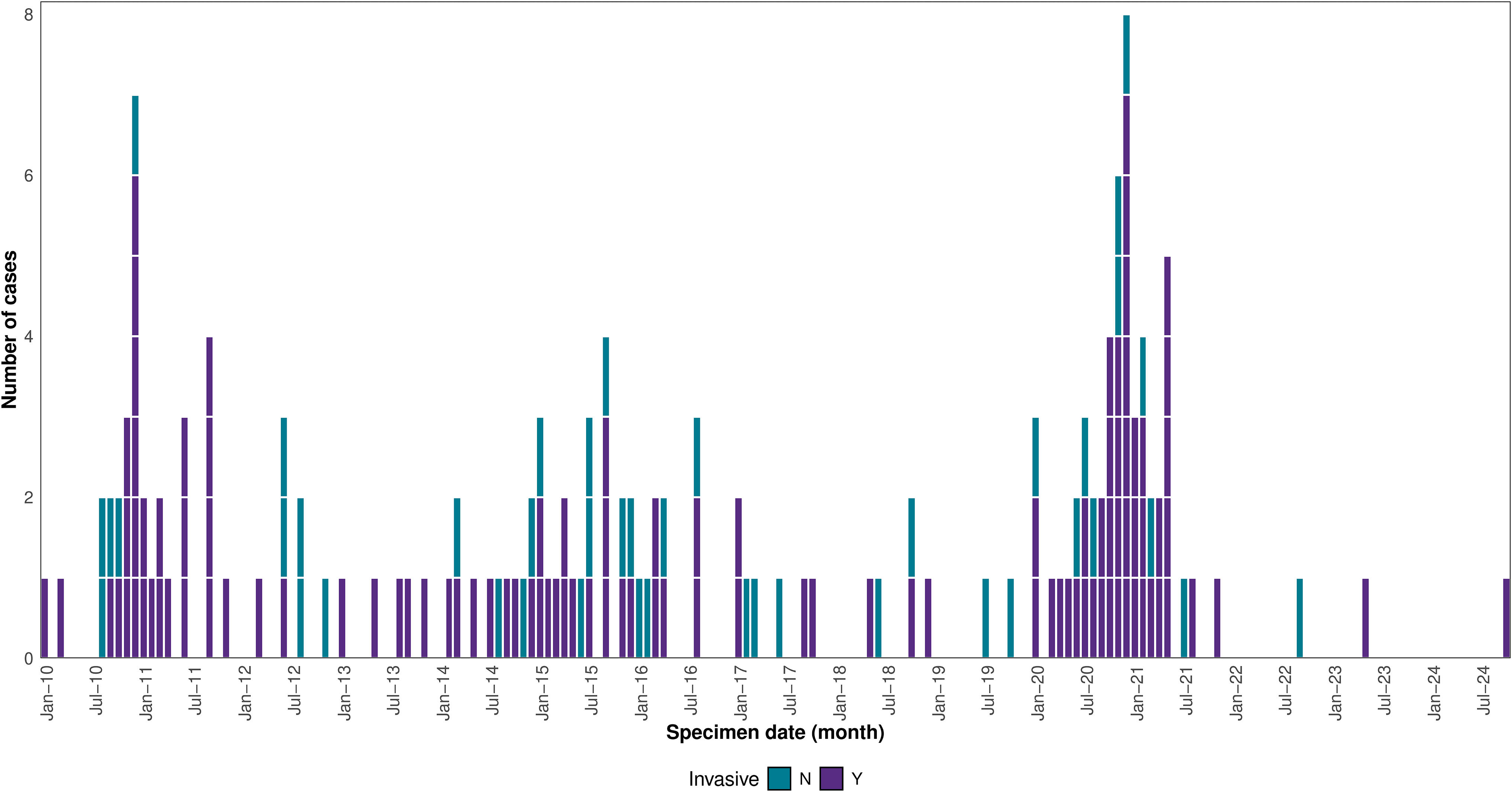

SGSS data demonstrated an increase in Bcc cases during the latter months of 2020, compared to case numbers in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution by specimen date of invasive isolates of relevant species belonging to the Burkholderia cepacia complex, United Kingdom, 01 January 2018–31 November 2024 (n = 354). Data source: UKHSA Second-Generation Surveillance System (SGSS).*

*Data extracted from the UKHSA SGSS Communicable Disease Reports (CDR) module on 5 December 2024. Reports are de-duplicated by CDR Organism-Patient-Illness-Episode identifier; the earliest specimen within this window is retained. 11 suspected environmental or quality assurance isolates were removed from the dataset. Reports only include specimens taken from sterile sites and lower respiratory tract. Bcc species included were B. contaminans, B. aenigmatica, B. cepacia, B. stabilis, B. cenocepacia and B. lata.

B. cepacia cluster

In total, 153 confirmed B. cepacia cases were identified between January 2010 and October 2024, peaking during November-December 2020 (Figure 2). Confirmed cases were predominantly hospitalized. Half of cases (n = 79, 52%) were male. Cases were of a wide age range (0–89 years, median 54 years), and 10 (7%) were aged under 1 year. There was a wide geographical distribution, with cases identified from isolates submitted by 70 hospitals. Isolates for 110 (72%) confirmed cases were from sterile sites or were otherwise considered invasive. Twenty-three cases died within 28 days of the date of the isolate (data unavailable for 17 cases) though no deaths were directly attributed to B. cepacia infection.

Figure 2. Distribution of confirmed B. cepacia ST767 outbreak strain cases by date of earliest specimen, UK and Ireland, January 2010–July 2024 (data correct as of October 2024), (n = 153).

Several hospitals conducted product testing, and one hospital identified an association between patient infections and an ultrasound gel product. B. cepacia was subsequently isolated by UKHSA from 29 samples of the same ultrasound gel from 9 different hospitals. All isolates were therefore suspected to be derived from a single non-sterile ultrasound gel product.

The isolates of the B. cepacia cluster over an 11-year period showed some diversity in PFGE profile, but were highly similar, with isolates from patients and ultrasound gel clearly related irrespective of which hospital they were from.

WGS of 14 isolates of the B. cepacia cluster, of which nine were from patients and six from ultrasound gel, showed that isolates belonged to ST767 and differed by 1–31 SNPs. Isolates from gel from three hospitals showed a similar extent of diversity (2–23 SNPs apart) as isolates from patients (12–31 SNPs apart) from five different hospitals and those from gel and patients from the same hospital (1–25 SNPs apart); one patient isolate differed by only one SNP from a gel isolate from that hospital, whilst gel isolates from two different hospitals were only two SNPs apart.

B. contaminans cluster

Between August 2020 and October 2022, 66 confirmed B. contaminans cases were identified (Figure 3) from 36 hospitals across England and Wales. The majority had specimen dates from mid-October 2020 to mid-February 2021, with apparent peaks in early December 2020 and late January-early February 2021, followed by a marked reduction from March 2021. Of the 64 cases for whom data was available, 33 (52%) were male. Cases had an age range of 0–90 years (median of 55.5 years). Most isolates (47/66, 71%) were from sterile sites or considered invasive, with 35/47 (53%) of these retrieved from blood. Isolates were also retrieved from sputum (n = 9, 14%) and urine (n = 2, 3%). Where focus of infection was reported, line infection (typically long-standing central intravenous catheter) was the most frequent (n = 20, 38%). Two thirds (n = 39, 67%) of cases received specific antibiotic treatment for clinically significant B. contaminans infection. Of the 66 confirmed cases, nine deaths occurred within 28 days of their specimen date, although no deaths were directly attributed to B. contaminans infection.

Figure 3. Distribution of confirmed B. contaminans ST1891 cluster cases by date of earliest specimen, United Kingdom, July 2020 to November 2024 (n = 66).

Fifty-two of 62 (84%) questionnaires deployed for confirmed B. contaminans cases were returned. All 52 cases had significant comorbidities, including malignancy (19%), diabetes mellitus (12%), cardiac failure (6%), and renal failure (4%). A total of 48 (92%) were inpatients during the 30 days before the specimen date and 36 (69%) spent time in intensive care units.

During the case period in the unidirectional case-crossover study (23 days prior to specimen date), 46 (88.5%) cases were exposed to either an ultrasound procedure (including ultrasound-guided line insertions, ultrasound scans, and echocardiograms). When refining the denominator to sterile or invasive isolates only (n = 38), 29 (76%) patients were exposed to an ultrasound procedure during the case period, which far exceeded other reported exposures, and 12 (32%) patients were exposed during the control period.

Logistic regression models (Supplementary Table S1) demonstrated that in comparison to the control period, exposure to an ultrasound-guided procedure during the case period was associated with B. contaminans infection (aOR: 5.7, 95% CI: 1.6–20.9, p = 0.009). However, testing of disinfectant wipes by the product manufacturer revealed contamination with Bcc. The outbreak strain of B. contaminans was isolated from an opened pack of disinfectant wipes submitted to UKHSA by a hospital with a confirmed case in July 2021.

Isolates from the 66 confirmed cases of the B. contaminans cluster shared identical PFGE profiles. WGS of 15 B. contaminans isolates, each from a different patient, from ten hospitals showed that these isolates all belonged to ST1891 and had 0–4 SNP differences between them. The patient isolates within the cluster had 0–3 SNP differences compared with isolates from the implicated wipes, confirming contaminated disinfectant wipes as the source for the B. contaminans cluster. Interview findings supported a link between the two hypotheses, suggesting it was common practice to use disinfectant wipes to decontaminate ultrasound probes, machines, keyboards, and gel bottles.

There was no evidence of polymicrobial contamination or of additional organisms identified using non-selective culture associated with either cluster.

Outbreak control measures

To raise awareness of the outbreaks and facilitate investigation and implementation of mitigation and control measures, UKHSA issued three briefing notes to the healthcare system. International alerting communications were sent via the Early Warning and Response System and the Epidemic Intelligence Information System for antimicrobial resistance and healthcare-associated infections to alert international institutions to the risk, facilitate detection in their territories and to request information if experiencing similar outbreaks. 26,27

B. cepacia

In light of the multiple practice issues with the use of ultrasound gel discovered during the investigation, an expert working group comprising stakeholders from multiple organizations and societies was established to produce comprehensive guidance on the safe use of ultrasound gel, to mitigate risks associated with contamination (later updated in 2025). 28 A National Patient Safety Alert was issued by UKHSA in November 2021 to reinforce and mandate recommendations within this guidance. 29

UK ultrasound gel suppliers voluntarily suspended supply of affected products and the outbreak investigation findings informed the decision to suspend central procurement of implicated gel products for the health system. The contaminated ultrasound product was not withdrawn, however, as no regulatory requirements were breached.

B. contaminans

The manufacturer of the implicated wipes issued a Field Safety Notice in May 2021, and relevant batches of this product were recalled. 30 An update was published in August 2021 to advise of an additional four contaminated batches. The manufacturer suspended production of the product at the affected factory, which was subsequently closed.

Discussion

We report two national outbreaks of Bcc infections associated with contaminated non-medicinal products in the UK and Ireland. These outbreaks involved hospitalized patients, many of whom had spent time in intensive care and had clinically significant infections. The outbreaks were complex to investigate, requiring national coordination and leadership, which occurred in one multidisciplinary team. This combined approach was more efficient, although there was the potential for confusion between clusters during investigation and written communications.

There were three key challenges to highlight. Firstly, the detection of Bcc outbreaks is challenging because Bcc isolates are not routinely speciated at hospital laboratory level nor routinely submitted for typing or sequencing, and Bcc species are not notifiable organisms. They are usually submitted to AMRHAI for typing when a cluster is suspected, there is an unusual resistance profile, or where results may impact on clinical management, such as for patients with cystic fibrosis. In addition, the request for hospitals in England to send first-time isolates of Bcc to the AMRHAI have been restated in communications associated with investigation of other Bcc clusters since these outbreaks. Detection may have improved with the use of Maldi-ToF; however, it remains difficult to detect clusters, especially if not suspected at local level or widely distributed. The scale and impact of the outbreaks are likely to be underestimated.

Secondly, it was difficult to confirm the source of infection. It was suspected that the outbreaks were caused by exposure to a contaminated product; however, there was a vast range of potential sources including medical devices and cosmetic products. We found that patients were exposed to so many products that it was difficult to prioritize which to sample. Many of the potential sources were ubiquitous in healthcare environments, with little documentation of product use. It was difficult to capture relevant, accurate information on exposures and use of products and to access product samples from hospitals in a timely manner, especially given the pressures on clinical teams during the COVID-19 pandemic. Questionnaire completeness was often poor, especially concerning exposure to products, details of procedures and brands or batches of products used; therefore, telephone interviews were required to gather further information. Identification of exposures often relied on recall or was extrapolated from knowledge of products in use rather than written records, which may have led to recall bias.

It is not always practical to conduct analytical epidemiological studies in outbreaks associated with contaminated products. Descriptive epidemiology using questionnaires and interviews, local team investigation, product testing (by manufacturer and UKHSA), and use of WGS and PFGE profiling were conducive to identifying the contaminated products and produce strong evidence of a common source for each cluster to facilitate timely public health action. Furthermore, in the B. contaminans outbreak, the case-crossover study inferred ultrasound gel as the source; however, product sampling subsequently revealed the source to be disinfectant wipes. As these wipes were used ubiquitously and use is not recorded, it is unlikely there would be any meaningful difference in exposure in case and control periods, and differential use would not be detected. The case-cross over design was therefore not appropriate, and arguably any analytical approach would have limited ability to differentiate association for a product used so commonly in healthcare environments. Many cases were likely to have had invasive procedures such as line insertion under ultrasound guidance, and interviews suggested use of disinfectant wipes to decontaminate equipment used for ultrasound imaging which might explain the observed association. The multidisciplinary investigation facilitated the identification of outbreak sources and clinical practice factors associated with transmission.

Thirdly, there were limited options for intervention for the B. cepacia outbreak. Interviews with hospitals highlighted clinical practice issues relevant to outbreak propagation including use of non-sterile ultrasound gel on procedure sites prior to invasive procedures and decanting of gel from large volume containers to small bottles, followed by repeated refilling of those same bottles over prolonged periods in clinical areas. However, the contaminated ultrasound product was not required to be withdrawn as no regulatory requirements had been breached. Therefore, control measures for the B. cepacia outbreak required multifaceted interventions including supplier and customer suspensions, dissemination of new national guidance, and a National Patient Safety Alert. Furthermore, the lead time between contamination and cluster detection is a barrier to timely public health actions, although such interventions remain necessary to prevent further cases.

UKHSA frequently investigate outbreaks linked to contaminated products, which can include products not designed to be specifically used in healthcare settings or on vulnerable patients, and products distributed internationally. Reference Somani, Fauzi and Sridhar31 The propensity for contamination and weaknesses in regulation present ongoing risk and there is clear need to pursue initiatives to prevent such incidents and better protect patients and the public. Reference Food and Administration32 This could include strengthening regulatory and product standards, for example, to improve the microbiological quality of water used in manufacture 33,34 . Furthermore, risk associated with use of these products can be reduced through increasing awareness of infection risk amongst clinicians, reinforcement of good IPC practices, clear NHS guidance for product procurement, and guidance on the use of sterile and non-sterile products for high-risk settings and patient groups.

We recommend close surveillance of Bcc, and the maintenance of a low threshold for investigation of clusters given the propensity for contamination incidents. We recommend adopting a multidisciplinary approach and close involvement of local microbiology and infection control teams for investigation, multi-stakeholder collaboration including internationally where relevant, and behavioral-focused interventions addressing clinical practice to ensure patient safety especially where regulatory actions are limited. Enhanced surveillance of Bcc was not in place at the time of the two clusters; however, our experience increased alertness in the system and facilitated timely outbreak detection and response to other Bcc clusters, which also involved multi-stakeholder communication and product recall. 35

Outbreaks from contaminated non-medicinal products represent an evolving public health threat and demands on public health institutions to respond to such outbreaks are likely to increase with improvements in access to higher resolution diagnostic methods facilitating their detection.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2025.10232

Data availability statement

Sequences of representative isolates from the B. cepacia and B. contaminans clusters are deposited respectively on the Sequence Read Archive under projects PRJNA1076694 and PRJNA688030.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the staff in participating hospitals who contributed to the study. In addition, the authors would like to thank all members of the Incident Management Team for their valuable input and advice throughout the incident. We would also like to extend gratitude to all staff involved in the investigation at the laboratories and national reference laboratories. We are also very grateful to Professor Peter Vandamme and Dr Eliza Depoorter (Laboratory of Microbiology, Ghent University, Belgium) for confirmation of the species-level ID for the B. contaminans cluster, to David Williams, David Lee and Ulf Schaefer for their bioinformatic expertise, to Ashley Popay for epidemiological review of B. contaminans isolates, and to Dr Marina Morgan and Dr Melissa Baxter for their initial work in identifying the link between patient infections and ultrasound gel. YW is a research fellow funded by the David Price Evans Endowment (grant number: UGG10057) at the University of Liverpool and was an Imperial Institutional Strategic Support Fund Springboard Research Fellow, funded by the Wellcome Trust and Imperial College London (grant number: PSN109). Authors YW and CSB are affiliated with the National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London in partnership with the UKHSA, in collaboration with, Imperial Healthcare Partners, University of Cambridge and University of Warwick (grant number: NIHR200876). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UKHSA, the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author contributions

JD & JE developed the study protocol with input from all other authors. JD conducted the epidemiological analysis. JT, DK & YW conducted the molecular characterization. CW conducted the product testing. DE and AW produced figures. JD, CF, NC, JE, and MS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to edits, reviews and/or revisions.

Financial support

No funding was required.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

This work was conducted as part of routine outbreak investigation led by the UKHSA and ethical approval was not required. The UKHSA has legal permission, provided by Regulation 3 of The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002, to process patient confidential information for national surveillance of communicable diseases and as such, individual patient consent was not required.

Collaborators

The authors fulfill all four ICMJE authorship criteria.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

Artificial intelligence tools were not used in the writing of this manuscript.

Preprint

This manuscript has not been submitted for preprint.