Introduction

In 2024, German politics faced four major challenges: economic recession, immigration, the rise of the radical right, and growing instability within the governing coalition. The ongoing economic recession put pressure on the government, as the GDP shrank for the second consecutive year (Deutsche Welle 2024a). At the same time, immigration remained one of the most salient and divisive issues as debates on internal security intensified amid a series of terrorist attacks, some involving asylum seekers. The radical-right Alternative für Deutschland/Alternative for Germany (AfD) capitalized on these concerns, while parties across the spectrum increasingly shifted toward more restrictive immigration policies (Deutsche Welle 2024b).

The year 2024 was a major election year (Superwahljahr) with three state elections in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg as well as the election for the European Parliament (EP). The three parties of the federal “traffic light coalition” (Ampelkoalition),Footnote 1 the Social Democratic Party of Germany/Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), the Alliance 90/Greens (Bündnis90/Die Grünen), and the Free Democratic Party/Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP) lost votes and seats in all four elections, while the newly founded Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht/Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) and the AfD gained electorally.

Amidst a 40 per cent rise in politically motivated crimes, especially in the area of right-wing extremism (Bundesministerium des Inneren 2025; Foreign Policy 2024), the year also saw historic protests after reports have revealed that AfD politicians had met with radical-right extremists to discuss “remigration” policies, widely interpreted as mass deportation plans (Correctiv 2024). Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in what became some of the largest demonstrations in decades against the growing strength of the AfD, which continued to perform well in the polls and at elections (Deutsche Welle 2024c).

Faced with internal divisions over fiscal policy and general economic direction, the governing “traffic light coalition” of the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP continued to struggle after devastating losses in the EP and regional elections in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg (Financial Times 2024). The situation escalated when the FDP published an economic plan consisting of major budget cuts that were unacceptable to the coalition partners. In November 2024, Chancellor Olaf Scholz dismissed Finance Minister Christian Lindner and other FDP ministers, leading to the collapse of the coalition (Bundesregierung 2025). The German Bundestag was dissolved in December, and snap elections were scheduled for February 2025 (Deutscher Bundestag 2024a).

Another key development was the emergence of the BSW, which split from the Left Party/Die Linke in early 2024 (see also Political Party Report) and quickly gained electoral traction, particularly in eastern Germany. This further highlighted the changing dynamics of Germany's party system, which has become even more fragmented and polarized, making coalition-building increasingly difficult (see also Saalfeld & Lutsenko Reference Saalfeld, Lutsenko, Oswald and Roberson2022). This is evident in the breakdown of the traffic light coalition and the complex post-election negotiations in the East German Länder/states, where government formation proved nearly impossible, leading to two minority cabinets in Thuringia and Saxony. These developments highlight the erosion of the political center in Germany and the growing strength of the political fringes, trends that risk deepening polarization and challenges for cabinet formation and political stability (see also Angenendt & Brause Reference Angenendt, Brause, Poguntke and Hofmeister2024).

Election report

European parliamentary elections

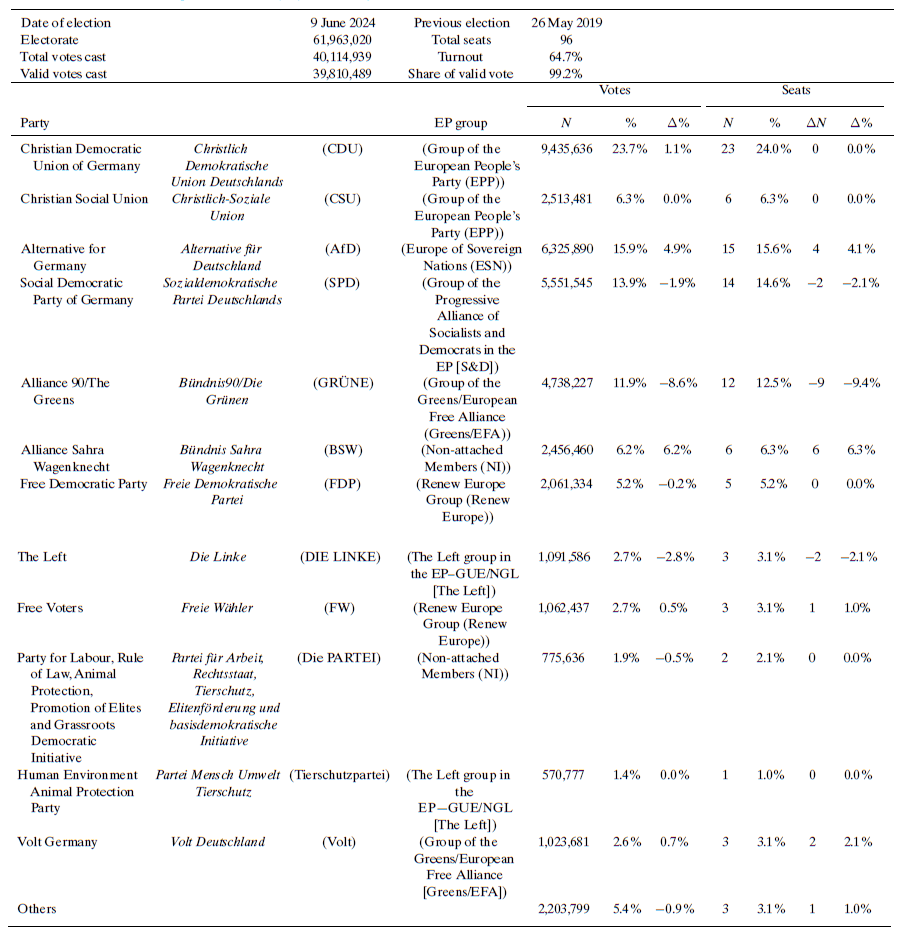

In the European elections held in Germany from 6 to 9 June 2024, voter turnout reached 64.7 per cent (Table 1). The Christlich Demokratische Union/Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and CSU (Christlich Soziale Union/Christian Social Union) alliance came in first with 30.0 per cent of the vote, followed by the AfD, which achieved its best result to date with 15.9 per cent. The SPD came in third, receiving its worst result in a nationwide election to date (13.9 per cent). The Greens suffered significant losses and placed fourth, while the FDP maintained a stable result. The newly founded BSW entered the EP for the first time with 6.2 per cent of the vote, while the Left lost two of its five seats. Several smaller parties were successful in entering parliament due to the absence of an electoral threshold in EP elections, including Volt (three seats), the Free Voters/Freie Wähler (three seats), the Party/Die PARTEI (two seats) and the Human Environment Animal Protection Party/Partei Mensch Umwelt Tierschutz (three seats) (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2024a). On 18 July 2024, Ursula von der Leyen (CDU) was elected European Commission President for a second term by the EP.

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament (EP) in Germany in 2024

Note: Parties listed under “other” received less than one per cent of the vote. The three seats went to Familien-Partei Deutschlands/Family Party of Germany (Familie), Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei/Ecological Democratic Party, and Partei des Fortschritts/Party of Progress (PdF).

Regional elections

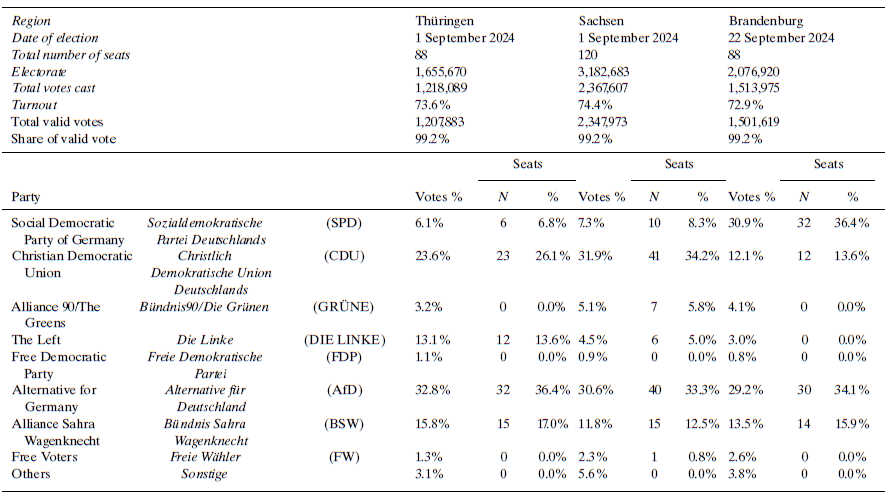

In 2024, there were three Land elections in the Eastern German states of Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg. All three elections took place in September (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of regional (Thüringen, Sachsen, Brandenburg) elections in Germany in 2024

Note: For Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia, total valid vote and share of valid vote refer to the second vote.

The Land election in Thuringia on 1 September 2024 led to significant political realignment. As early as 2019, Thuringia had come close to the ideal type of polarized pluralism, a party system characterized by a weakening political center, the strengthening of parties at the political extremes, and increasing difficulties in forming stable governments (Angenendt & Brause Reference Angenendt, Brause, Poguntke and Hofmeister2024: 82). For the first time, the AfD emerged as the strongest party in the state parliament with 32.8 per cent of the vote. The CDU came in second at a considerable distance (23.6 per cent), while the newly founded BSW reached 15.8 per cent, becoming the third strongest party. The Left Party, previously the leading governing party, suffered massive losses. The SPD only narrowly cleared the electoral threshold, while both the Greens and the FDP failed to enter the state parliament. Forming a government proved extremely difficult due to the strong polarization in parliament. Ultimately, the CDU, BSW, and SPD agreed to form a coalition with Mario Voigt (CDU) elected as Minister-President (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2024b).

In Saxony, the Land election on 1 September 2024 saw the CDU defend its position as the strongest party (31.9 per cent), with the AfD following closely behind with 30.6 per cent. BSW placed third with 11.8 per cent. The SPD remained almost stable (7.3 per cent), while the Greens narrowly cleared the 5 per cent threshold with 5.1 per cent. The Left Party failed to reach this threshold but was still able to enter parliament winning two direct mandates.Footnote 2 The Free Voters achieved 2.3 per cent yet also secured a direct mandate. Following the election, the fragmented party system made it impossible to form a majority coalition. The CDU and SPD ultimately agreed on a minority coalition, once again led by Michael Kretschmer (CDU) as Minister-President (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2024c).

In the Brandenburg state election on 22 September 2024, the SPD under Minister-President Dietmar Woidke secured a narrow victory with 30.9 per cent of the vote, narrowly ahead of the AfD. The BSW again achieved a strong third-place result, surpassing the CDU, which came in at only 12.1 per cent. The FDP, the Greens, the Left, and the Free Voters all clearly failed to enter the state parliament. The Greens (−6.7 percentage points) and the Left Party (−7.7 percentage points) experienced particularly significant losses, compared to the previous election. Following intense coalition negotiations, the SPD and BSW agreed to form a government, with Dietmar Woidke re-elected as Minister-President (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2024d).

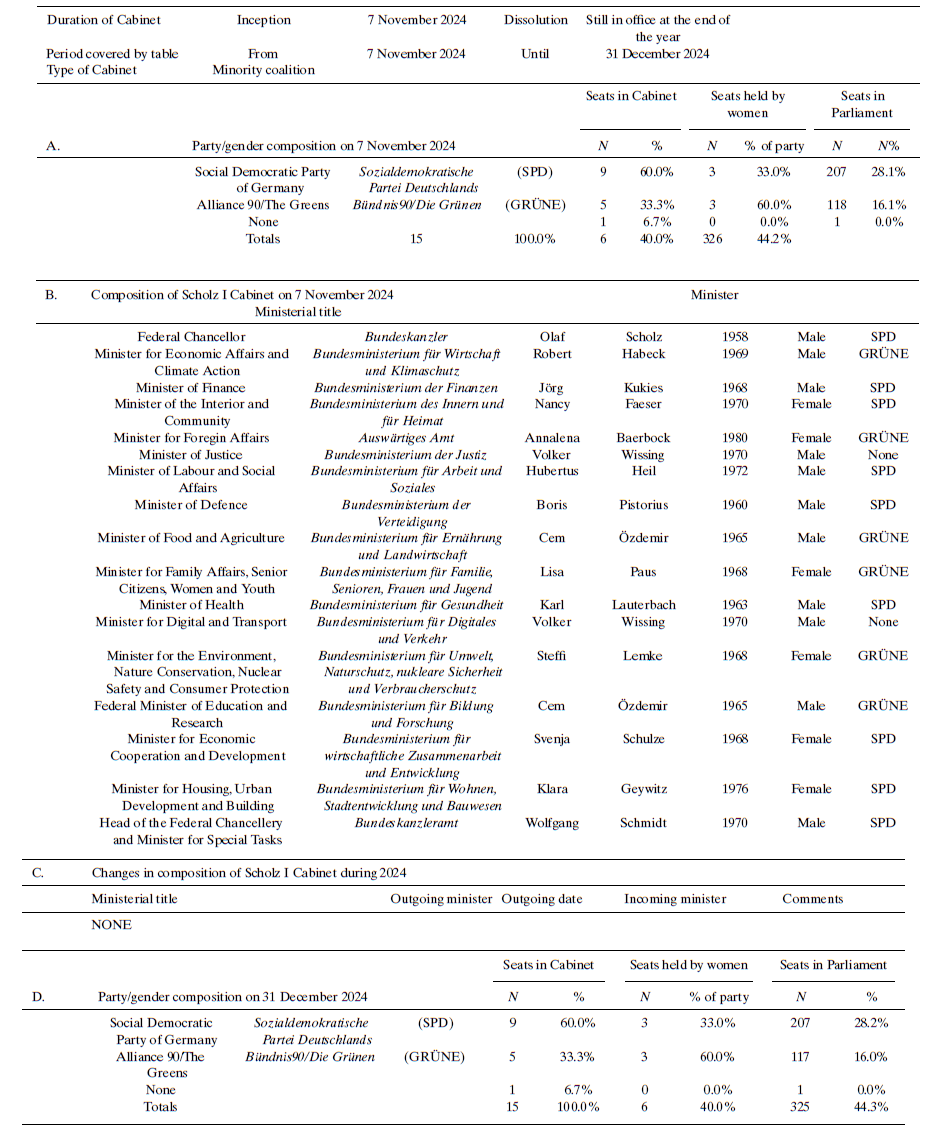

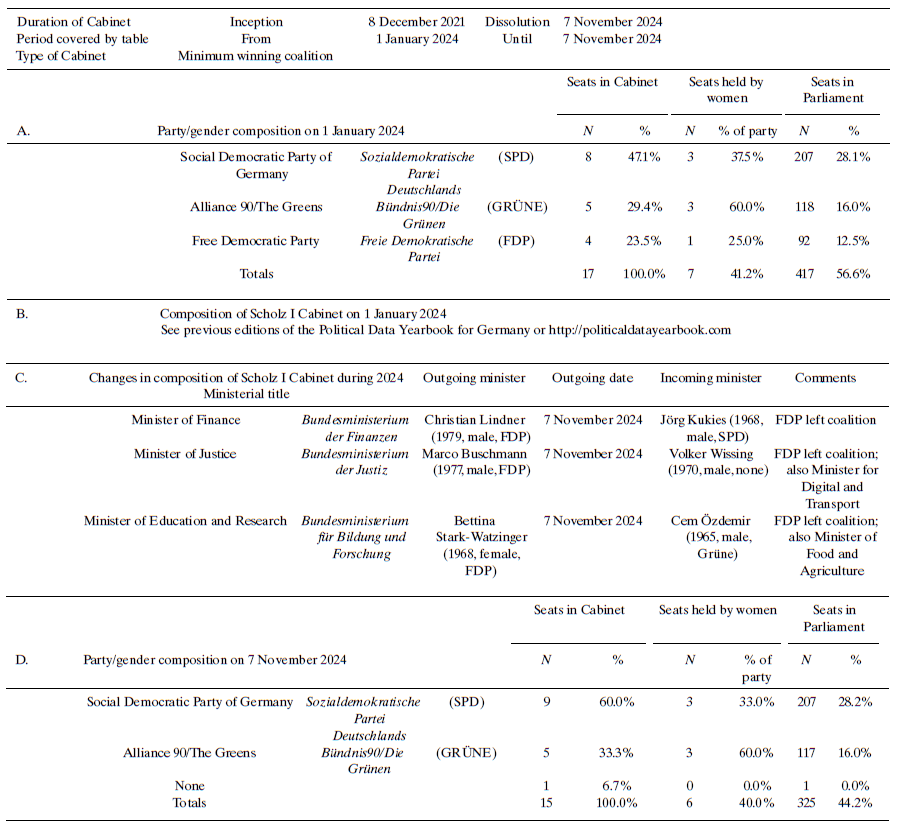

Cabinet report

Due to the dissolution of the traffic light coalition in November 2024, the composition of the cabinet changed significantly (Tables 3 and 4). Christian Lindner (FDP) was dismissed as Finance Minister on 6 November, and two other FDP ministers, Minister of Education and Research, Bettina Stark-Watzinger, and Minister of Justice, Marco Buschmann, left the coalition on 7 November. This marked the end of the coalition, leading to the formation of a minority government consisting of the SPD and the Greens. Volker Wissing, Minister for Digitalization and Transport, left the FDP and remained in government, also assuming the role as Minister of Justice. Cem Özdemir (Greens), in addition to his role as Minister of Food and Agriculture, took over the Ministry of Education and Research. Chancellor Olaf Scholz appointed Jörg Kukies (SPD) as the new Minister of Finance (Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung 2025).

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Scholz I in Germany in 2024 (until 31 December)

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Scholz I in Germany in 2024 (until 7 November)

Parliament report

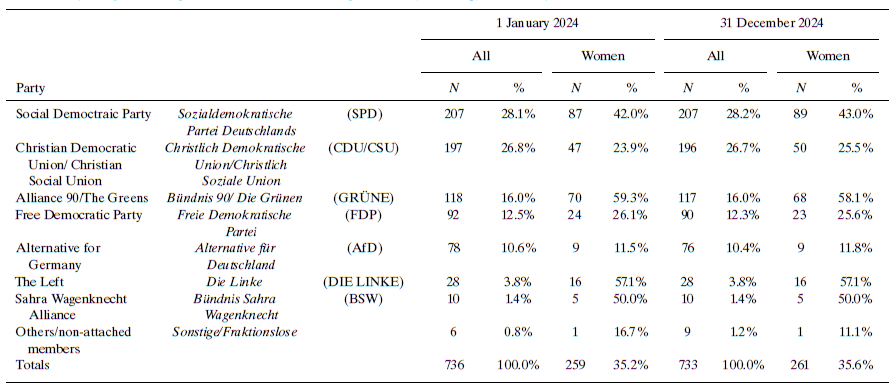

This section outlines significant changes in the composition of the Bundestag in 2024 (Table 5), presented in chronological order.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house of parliament (Bundestag) in Germany in 2024

Following Sahra Wagenknecht's departure from the Left parliamentary party group (Fraktion), along with nine other members at the end of 2023 (Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2024), and the formal establishment of the BSW as a political party on 8 January 2024 (see Political Party Report below), the Bundestag decided on 2 February to grant so-called Gruppenstatus (group status) to both the Left and BSW. The resolution was adopted by a majority of the governing coalition against the votes of the CDU/CSU and AfD (Deutscher Bundestag 2024c).

Members of Parliament who share a political affiliation but do not meet the minimum requirement of 37 members for forming a parliamentary party group (Fraktion) may instead form a parliamentary group (Gruppe). Recognition of such a group is subject to approval by the plenary. Unlike full parliamentary party groups, these groups are not entitled to financial or material resources from the federal budget (ibid.).

Another important development was the partial repeat election of the 2021 federal election in Berlin. Due to irregularities during the 2021 federal election and the simultaneous election to the Berlin House of Representatives (Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2022), it was decided in 2022 that the entire House of Representatives election and the federal election in some electoral districts in Berlin had to be repeated (for details, see Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2023). While the repeat election for the Berlin House of Representatives took place in 2023 (Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2024), the partial rerun of the federal election in Berlin was held on 11 February 2024. On 1 March, the Federal Electoral Committee officially confirmed a shift in the seat distribution, compared to 2021. As a result of these losses in votes, four Members of Parliament, Lars Lindemann (FDP), Pascal Meiser (The Left), Nina Stahr (Greens), and Ana-Maria Trăsnea (SPD), lost their mandate; a decision that must be taken by the Council of Elders (Ältestenrat) of the Bundestag as stipulated by the Federal Elections Act. However, the recalculated seat distribution led to the SPD in Lower Saxony, the Greens in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the Left in Hesse each gaining one seat, while Lars Lindemann's (FDP) lost seat was not reassigned (Deutscher Bundestag 2024d). The three Members of Parliament were replaced by Angela Hohmann (SPD, Lower Saxony), Franziska Krumwiede-Steiner (Greens, North Rhine-Westphalia), and Jörg Cezanne (The Left, Hesse) (Das Parlament 2024).

In July, Melis Sekmen left the Greens to join the CDU/CSU parliamentary party group (Deutscher Bundestag 2024e). After the dissolution of the traffic light coalition, Volker Wissing, following his resignation from the FDP, became a non-attached member (Deutscher Bundestag 2024f). Additionally, two members of the AfD became non-attached members: Thomas Seitz and Dirk Spaniel, the latter had joined the newly formed party Union of Values/WerteUnion (see also Political Party Report below) (Deutscher Bundestag 2024g, 2024h).

Political party report

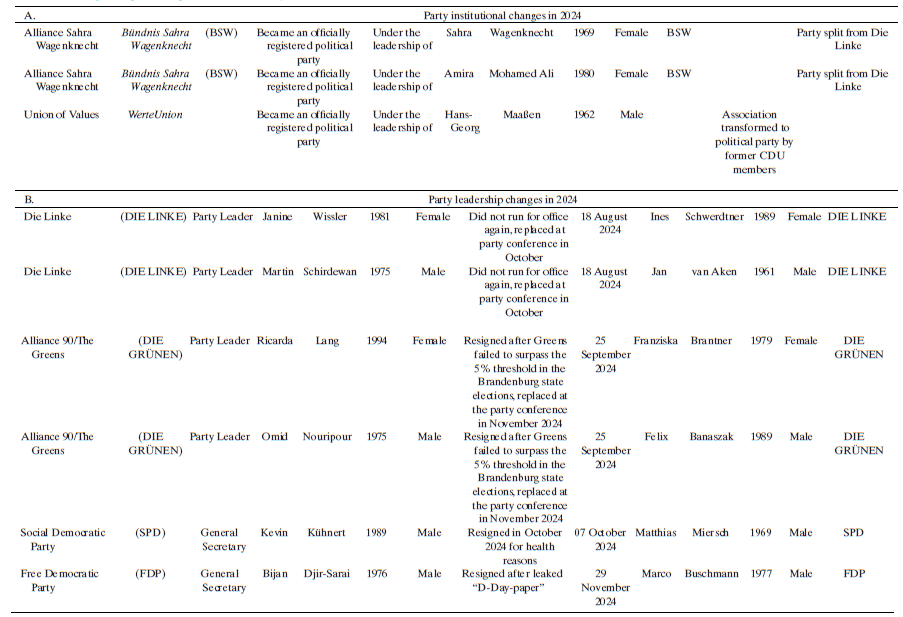

The following section discusses the formation of two new parties and the changes in party leadership. New party formations are rare in Germany, but 2024 even saw two cases. Following the founding of the BSW at the end of 2023 (for discussion, see Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2024), the alliance officially established itself as a political party on 8 January 2024 with 44 members under the name Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – für Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit (for Reason and Justice) (tagesschau.de 2024a). Sahra Wagenknecht and Amira Mohamed Ali became the party's co-leaders. Shervin Haghsheno was named deputy chair while Christian Leye took on the position of general secretary (Deutsche Welle 2024d). The party may be called left-conservative, with economically left and culturally right positions (e.g., regarding immigration and national identity) (Herold & Otteni Reference Herold and Otteni2025). However, the label of the party is still contested (Bitschnau Reference Bitschnau2024), with some calling the party left-authoritarian (Heckmann et al. Reference Heckmann, Wurthman and Wagner2025: 2–4), populist (Thomeczek Reference Thomeczek2024), or left-nationalist (Steiner & Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2025).

The right-wing conservative association WerteUnion (Deutschlandfunk 2024) was transformed into a political party on 17 February 2024, spearheaded by Hans-Georg Maaßen, the former head of the German Office for the Protection of the Constitution. After expulsion proceedings were initiated against him in 2023, Maaßen pre-emptively left the CDU in January 2024. The Office had stored information about him in connection to radical right extremism (tagesschau.de 2024b).

For the CDU/CSU, there were no leadership changes in 2024. Friedrich Merz was re-elected as party leader of the CDU on 6 May.

Following the Green party's poor performance in the Land elections in September, all members of the party's executive committee resigned (Deutsche Welle 2024e). In addition, the executive board of the party's youth wing also stepped down and simultaneously announced their departure from the party (tagesschau.de 2024c). In November, Franziska Brantner and Felix Banaszak were elected as the new party co-leaders with Pegah Edalatian appointed as general secretary.

The general secretary of the SPD, Kevin Kühnert, resigned on 7 October due to health issues. He was replaced by Matthias Miersch, the former vice chair of the SPD parliamentary party group (Deutsche Welle 2024f).

The Left came under enormous pressure following the BSW split. In response, party leaders Janine Wissler and Martin Schirdewan announced they would not seek re-election (Deutsche Welle 2024g). On 19 October, Ines Schwerdtner and Jan van Aken were elected as the new co-leaders (Deutsche Welle Reference e2024h).

After the release of documents confirming that the FDP had long planned the end of the traffic light coalition—using military terminology such as “D-Day” and “open field battle”—and revealing that senior party figures had been dishonest, the party's general secretary, Bijan Djir-Sarai, and its Bundesgeschäftsführer/executive director, Carsten Reymann, resigned at the end of November (Euronews 2024). Marco Buschmann was appointed the new FDP general secretary on 2 December. Table 6 summarizes all these changes.

Institutional change report

On 19 December 2024, the Bundestag passed an amendment to Articles 93 and 94 of the German Basic Law (Grundgesetz) with the required two-thirds majority. The amendment clarifies the Federal Constitutional Court's (Bundesverfassungsgericht) institutional framework, enshrining key structural principles of the Federal Constitutional Court in the Basic Law, like its autonomy to regulate internal affairs and the number of senates and judges as well as the term length and age limit for judges. The reform is intended to strengthen the Court's independence and protect its structure against attempts to control it politically.

A second legislative proposal to amend the Federal Constitutional Court Act (Bundesverfassungsgerichtsgesetz) was adopted that introduces a replacement mechanism for judicial appointments in cases of political deadlock, ensuring the continued functionality of the Constitutional Court in the event of gridlock in the judge selection process. Judges are appointed by the German Bundestag and Bundesrat (the German second chamber) with a two-thirds majority. In the past, compromises on candidates were always possible. However, increasing fragmentation and growing divisions between the parties make such agreements on appointees less likely. The new mechanism allows judges to be appointed by a two-thirds majority in either the Bundestag or Bundesrat in case of political gridlock. This reform aims to strengthen judicial stability and prevent prolonged vacancies in Germany's highest court, in the wake of strengthened political fringes, which could block the nomination of judges of the Constitutional Court. Both legislative proposals were tabled by the SPD, CDU/CSU, Greens, FDP, and a non-attached member from the Südschleswigscher Wählerverband (SSW). The group, the Left, also voted in favor of both proposals (Deutscher Bundestag 2024l, 2024m).

Issues in national politics

In 2024, the economy and immigration dominated the political debate in Germany. The economy faced persistent challenges, with GDP shrinking for the second consecutive year. Although inflation gradually decreased from its 2023 peak, high energy prices, rising company insolvencies, and growing public uncertainty kept the economic outlook bleak (Deutsche Welle 2024a). The car industry struggled with increased competition and plummeting foreign demand (Deutsche Welle 2025b). The government attempted to counteract these issues with subsidy programs, but internal coalition disputes hindered a coherent economic policy. Structural problems, such as demographic changes, high energy costs, and a slow transition to a climate-neutral industry, compounded the difficulties (Deutsche Welle 2024a). In light of these economic challenges, discussions on reforming the debt brake intensified, especially after a November 2023 ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court disrupted the government's financial planning (Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2024). While the SPD and Greens advocated for loosening the rule to boost investment, the FDP opposed it, leading to further tensions within the coalition (Deutsche Welle 2024k).

Immigration remained a central political issue throughout the year. In January, the government passed the Return Improvement Act (Gesetz zur Verbesserung von Rückführungen), aimed at facilitating the deportation of criminal offenders and expanding authorities’ search powers. In April, the prepaid card for asylum seekers was introduced to replace cash benefits, intended to prevent welfare fraud and limit the transfer of funds abroad. The debate intensified after multiple violent crimes, some committed by asylum seekers. CDU/CSU called for stricter migration laws, while the government sought to advance a broader security package that included benefit cuts for rejected asylum seekers, expanded investigative powers by the executive, and stricter regulations on carrying knives (Deutsche Welle 2024b). Following the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime, debates over the return of Syrian refugees intensified, with the AfD and parts of the CDU calling for an immediate revocation of asylum rights, while human rights organizations and parts of the governing coalition warned of the dangers (Deutsche Welle 2024l).

Tensions peaked in December after a terrorist attack at Magdeburg's Christmas market by a Saudi Arabian national, which left five dead and hundreds injured (The Guardian 2024). Radical right groups exploited the event for anti-Islamic purposes, leading to racist attacks in the city (Bayerischer Rundfunk 2024). In response, the CDU submitted a Bundestag motion titled “Policy Shift for Germany–Stop Illegal Migration, Fulfill Humanitarian Responsibility,” prompting the SPD to accuse the party of populism (Deutscher Bundestag 2024n).

Another major issue in 2024 was the growing strength of the AfD, sparking widespread protests and renewed calls for a party ban. Central to the public outcry was a report by Correctiv revealing a meeting in Potsdam between AfD politicians and radical right extremists, where plans for so-called “remigration”—understood as the mass deportation of migrants—were discussed (Correctiv 2024). The revelations triggered nationwide protests, with hundreds of thousands taking to the streets across the country (Deutsche Welle 2024c). Legal scrutiny of the party also intensified. It was ruled that the AfD's youth wing could officially be classified as a radical right extremist organization and that the AfD itself could be monitored as a “suspected radical right extremist case” by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Politico 2024). In the public and the parliamentary debate on the party's success, some advocated for stronger ideological confrontation, while others pushed for legal and institutional measures to curb its influence, like a motion to initiate a ban procedure (Deutsche Welle 2024m).

The wars on Ukraine and Gaza continued to be key issues in German politics. While public debate over arms deliveries became less pronounced, support for Ukraine remained high. Nonetheless, the topic served as a major mobilizing issue for the BSW, and the AfD also sought to capitalize on it (Deutsche Welle 2024n). Regarding the war on Gaza, the public support for Israel is high in Germany relative to other European countries. Accordingly, Germany remains the second-largest arms supplier to Israel. At the same time, the conflict sparked protest camps, including at universities, and led to debates over freedom of speech in Germany (Deutsche Welle 2024o, 2024p).

Finally, the ongoing conflicts within the governing coalition were a much-debated issue. Internal divisions, particularly over the debt brake and budget policies, had already weakened the coalition by 2023 (Angenendt & Kinski Reference Angenendt and Kinski2024: 171). The FDP's insistence on strict austerity measures, with Finance Minister Christian Lindner using his position to block several major coalition initiatives, exacerbated tensions. As discussed above, the coalition ultimately collapsed in November 2024 after a leaked policy paper from Lindner proposed economic measures deemed unacceptable by his partners (Deutsche Welle 2024k). The FDP faced heavy criticism after the leak of its “D-Day paper”, which revealed strategic plans to upend the coalition (Deutsche Welle 2024q). On 16 December, Scholz lost a confidence vote in the Bundestag with 394 votes against him. He then requested President Frank-Walter Steinmeier to dissolve parliament (Deutscher Bundestag 2024o). The Bundestag was officially dissolved on 27 December, and snap elections were scheduled for 23 February 2025 (Deutscher Bundestag 2024a).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jil Altmann, Paul Sax and Lina Schirmer for their helpful research assistance and the anonymous reviewer and the editors for their constructive feedback.