Two recent assessments of the governance of fiscal arrangements in the United Kingdom came up with scathing verdicts. Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Leslie, Pacitti and Smith2019: 13), writing just months before the pandemic struck, opined that the ‘UK was a pioneer in the development of fiscal rules but does not currently have an effective framework for fiscal policy’. Four years later, Tetlow et al. (Reference Tetlow, Bartrum and Pope2024: 40) came to the stark conclusion that ‘the original purpose of our fiscal framework—to embed a clear and comprehensive fiscal strategy and to force difficult trade-offs—has been lost’. They add: ‘even the existence of meaningful rules seems to have lost its significance: meeting their letter but not their spirit through trickery and games has become routine’.

Both articles concentrate on the flaws in the fiscal rules adopted by successive governments and embodied (over the last 15 years) in successive versions of the Charter for Fiscal Responsibility (CFR), the most recent dating from January 2025, offering explanations and proposing new approaches. Others have been even more forceful, including former Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell, who wrote prior to the autumn 2024 budget: we ‘should ditch the last government’s absurd debt rule’. Chadha (Reference Chadha2024) could scarcely have been more blunt, declaring that the UK’s current set of fiscal rules is ‘not fit for purpose’. He coined the phrase ‘Budgetarians’ to describe the defenders of focusing on a distant target based on unreliable forecasts, especially when the focus is on a parliamentary cycle that is unlikely to match an economic cycle.

This article takes the analysis further in two respects. First, it examines practice elsewhere, notably in countries that have had much greater success in keeping debt and deficit ratios well below those in the United Kingdom. Second, it broadens the scope of the analysis by looking at features of the fiscal framework other than the fiscal rules. On both counts, the study agrees with Hughes et al. and Tetlow et al. that the United Kingdom needs a wide-ranging recasting of its approach.

The next section of the article offers a short overview of fiscal frameworks. A comparative discussion of fiscal performance, as measured by debt ratios, follows for a selection of advanced economies, among which the United Kingdom is one of several where the fiscal arithmetic has deteriorated. The next section looks at two core areas for the fiscal framework: rules and scrutiny, then attention turns to wider governance considerations. The last section includes conclusions and a ‘menu’ of potential changes for the United Kingdom to consider.

1. Features of fiscal frameworks

Fiscal policy is much more than the choices governments make on taxation and public expenditure. It affects the economic performance of countries, has distributive consequences and affects politics in many ways (Chadha et al., Reference Chadha, Kucuk and Pabst2021; Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer2021). Governments can use discretionary fiscal policy to boost their electoral prospects, but also have to be alert to longer-term obligations to ensure the sustainability of the public finances. The latter calls for discipline aimed at curbing the well-documented tendency of governments to favour the short term, which is extensively addressed in the academic literature.

Fiscal policy is also a tool governments can use to counter an economic downturn, as many did in response to the global financial crisis of 2007–10 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Being able to respond in this way relies on having room for manoeuvre resulting from careful management of the public finances in ‘good times’ and an ability to convince financial markets of the creditworthiness of the state. Countries that markets deem lacking in this respect (as several European Union (EU) countries did during the sovereign debt crises of the 2010s) or that badly misjudge market reactions (as the short-lived Truss government in the United Kingdom did) can quickly find themselves in trouble.

The rationale for a fiscal framework is to embed government choices in an institutional and legal setting conducive to sound fiscal policy. It has to reconcile competing objectives while respecting democratic processes and, as a result, be sensitive to different influences at the same time as assuring credibility. A succinct definition proposed in an explainer by Begg and CicakFootnote 1 is:

‘The institutional framework and legal provisions governing how budgetary policy is planned, decided, implemented, constrained by rules and scrutiny processes, monitored and evaluated’.

Tying the hands of government is about inhibiting resort to riskier budgetary policies aimed at securing electoral advantage. Two overlapping interpretations of ‘risky’ can be put forward. The first is that public debt rises to levels at which the interest burden becomes excessive and, as a first call on public accounts, crowds out spending on public services and investment. Second, if markets take fright at higher debt (especially if the government lacks the will or the means to contain it), the national treasury will have to offer higher interest rates than more fiscally robust competitors. The extreme risk from high debt is a progressive loss of confidence by financial markets, leading to problems in funding the national debt or even insolvency.

While fiscal frameworks unavoidably need a degree of flexibility, including having formal escape clauses to suspend rules and other provisions in exceptional circumstances, two further considerations arise. First, compliance and, if necessary, enforcement matter. A government that ‘marks its own homework’ and, as has occurred with the many iterations of the United Kingdom’s CFR, is able to change the essay question, is bound to weaken commitment. Second, a robust framework should be able to prescribe an economically sound fiscal path, not just proscribe a suboptimal one (Buti, Reference Buti2015). In the United Kingdom, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Parliament, financial markets and the media all contribute to holding the government to account, but these channels need to be nourished.

2. Comparative fiscal performance of advanced economies

The difference between government income and expenditure (the fiscal balance—usually a deficit) and the stock of public debt are the two parameters most used to judge fiscal performance. Debt, above all, is the indicator most directly linked to fiscal sustainability. Trends in these indicators provide valuable insights into the quality of fiscal frameworks.

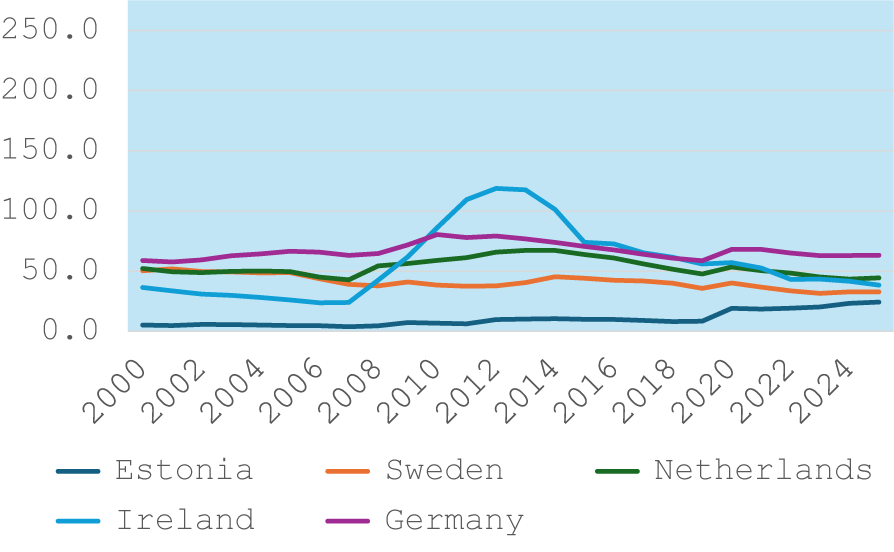

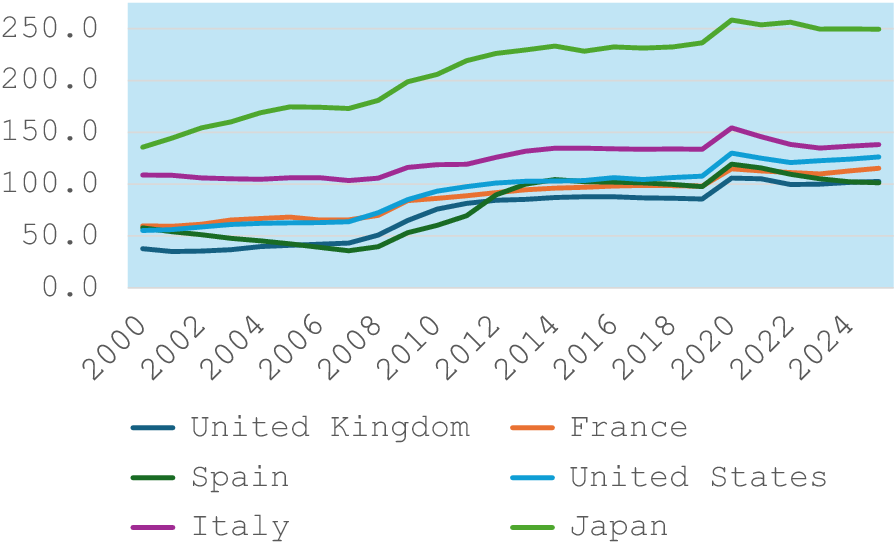

Figures 1 and 2 show the debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratios—using the definition of debt employed by the EU for assessing excessive deficits (sometimes referred to as ‘Maastricht’ debt)—for a selection of advanced economies, with the first chart covering low(er) debt countries and the second those where debt has trended upwards.

Figure 1. Debt to GDP ratios: Low to moderately indebted countries, 2000–2024.

Source: EU Ameco database

Figure 2. Debt to GDP ratios: Higher debt countries, 2000–2024.

Source: EU Ameco database

Among the low-debt group, Ireland’s trajectory is interesting, because although the debt surged as a result of the Irish sovereign debt crisis of 2010, it was rapidly reduced not only to under the EU’s 60% benchmark, but also returned to close to where it had been when the euro was launched.Footnote 2 For Germany, the downward trend in the decade prior to the pandemic is noteworthy, coinciding with a new approach (the ‘Schuldenbremse’, which translates as debt brake), while strong constitutional constraints in Estonia are behind its low debt levels (the same is true of Poland and Slovakia). Two other countries that transformed their fiscal frameworks after periods of instability are Sweden and Denmark, both of which saw debt ratios decline during the 2010s. Plainly, in all cases, the pandemic saw an increase in debt, but it was soon redressed.

Except for Germany, growth rates in the lower debt countries have tended to outpace the United Kingdom in recent years, but the fluctuations in growth associated with the sequence of crises, since the global financial crisis, make an explicit link to their fiscal frameworks difficult to demonstrate. Moreover, while the United Kingdom has been a country of net immigration, adding substantially to the labour force, others have not been or have seen fewer immigrants. Consequently, GDP per capita can tell a different story from headline growth.

In the higher debt group, Japan is an evident outlier with the relentless rise over two decades when the economy faced stagnation. In mitigation, Japanese debt is almost entirely held by its citizens, and, over most of the period, interest rates were negligible. However, what is striking in the others displayed is the steady increase throughout the 2010s, as well as the debt in 2023 remaining above pre-pandemic levels.

Key questions are what role fiscal frameworks have (or have had) in determining these trends in public debt. In some countries, wide-ranging reforms in frameworks have been adopted, often in response to previous episodes of acute fiscal crises. Following the massive fiscal packages to counter the effects of the pandemic, the fiscal position of many countries deteriorated, leaving a legacy of higher debt and, in the short term, increased debt service burdens that crowd out other expenditure priorities. As a recent article from the international monetary fund (IMF) observes, risks to debt sustainability have grown. The upshot is that ‘the breadth of challenges and risks argues for enhancing medium-term fiscal frameworks (MTFFs) that combine more flexible rules with stronger institutions to promote sound public finances’ (Caselli et al., Reference Caselli, Davoodi, Goncalves, Hong, Lagerborg, Medas, Nguyen and Yoo2022: 1).

Plainly, after the succession of crises since 2007, the challenges for UK fiscal policy have changed, while also becoming tougher. The first has been the ratcheting up of debt, initially because of the global financial crisis, then throughout the 2010s, and subsequently because of the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis. Pressure has come, second, from the normalisation of interest rates, after the prolonged period of near-zero rates from 2009.

3. Rethinking fiscal frameworks—rules and scrutiny

In considering how to recast fiscal frameworks, the rationale for having them and an understanding of how they can contribute to sound fiscal management need to be clear. Writing about the reforms of EU-level fiscal governance, Haroutunian et al. (Reference Haroutunian, Bankowski, Bischl, Bouabdallah, Hauptmeier, Leiner-Killinger, O’Connell, Arruga Oleaga, Abraham and Trzcinska2024: 4) suggest three overarching objectives that could be applied to fiscal frameworks more generally:

‘First, it needs to promote a realistic, gradual and sustained adjustment of public debt towards sound and sustainable levels. Second, it should support fiscal policy in becoming sufficiently countercyclical. Third, it should foster sound incentives for growth-friendly economic policies’.

The demands on fiscal frameworks are bound to be affected by the fiscal arithmetic; as Haroutunian et al. (Reference Haroutunian, Bankowski, Bischl, Bouabdallah, Hauptmeier, Leiner-Killinger, O’Connell, Arruga Oleaga, Abraham and Trzcinska2024: 4) observe: ‘there is no easy, one-size-fits-all solution to ensuring fiscal sustainability, stabilisation, and growth-friendliness’. However, debt sustainability will also be harder to achieve when debt is high, even if financial markets remain confident about a government with a relatively high level of debt. Who owns the debt, its term structure and the country’s growth potential are just some of the factors that make a difference.

3.1. Fiscal rules

All these considerations are germane to debates on fiscal rules. Resort to such rules has proliferated in recent decades and, as the database constructed by the IMF shows, many countries now have several rules in place. In describing the database, Davoodi et al. (Reference Davoodi, Elger, Fotiou, Garcia-Macia, Han, Lagerborg, Lam and Medas2022) note that the average number per country rose from two to three in the last two decades. Although budget balance or debt rules are still the most common, more countries (especially among the richer ones) now have expenditure rules, and more are embedding their rules in statutes, such as fiscal responsibility acts. The pandemic proved to be challenging for compliance with fiscal rules, but Davoodi et al. assert that the use of escape clauses demonstrated that fiscal rules can function flexibly.

Fiscal rules aim to provide simple constraints on the presumed deficit bias of governments, while also assuring the sustainability of the public finances. Various attributes of rules have to be taken into account:

-

• Ease of measurement and monitoring, including having aggregates that are regularly updated and not unduly subject to estimation or projections;

-

• Economic characteristics, ranging from avoiding pro-cyclicality, having enough flexibility to allow for responses to unforeseen circumstances and building up buffers in good times, in anticipation of longer-term calls on public expenditure (e.g., ageing or climate action);

-

• Support for quality of public spending, which can be interpreted narrowly as enabling sufficient public investment, but could also encompass other dimensions, such as being growth-enhancing or assuring good ‘performance’.

-

• Transparency not only vis-à-vis financial markets and administrative agencies but also legislators and the public;

-

• Being sufficiently firm to steer government choices, while having provisions for ensuring compliance and maintaining credibility.

No rule can easily meet all these criteria, and difficult trade-offs abound. Even so, the UK rule on having the debt fall at the end of a 5-year rolling forecast period does not fare well on these broad criteria. It relies on a double estimation, namely of the expected trends in both government revenue and spending, and on the trajectory of the economy. It is, as so many critics have argued, surprisingly loose insofar as the deadline always in the future does not preclude slippage in the short term. Nor is it an easy rule for the public to grasp, precisely because it is predicated on economic and budgetary projections. The rule can easily be changed at the discretion of the Treasury and, from this perspective, can be considered flexible, but this very flexibility (employed eight times since 2011) undermines credibility.

The OECD’s Spending Better Framework (OECD, 2023: 5) roots its prescriptions in 10 principles, of which 4 relate to what the organisation refers to as ‘medium-term and top-down’ budgeting. The first two concepts are defined, respectively, as:

-

• Budgeting for multiple years (usually 3–5 years), as opposed to focusing solely on the upcoming fiscal year.

-

• Defining spending limits based on the economic forecast, estimates of future spending on current policies (the baselines) and the government’s fiscal objectives.

In addition to having clear fiscal objectives and medium-term projections based on objective assumptions (something the OBR and fiscal councils elsewhere provide), the other two principles are instructive for the United Kingdom. They are having ‘multi-year expenditure baselines’ and ‘top-down expenditure ceilings’.

Denmark, Sweden and Finland have expenditure ceilings that are, arguably, the core elements of their fiscal frameworks. For the first two, these are legally based, whereas for Finland, the ceiling is based on convention. There are some differences in the definitions of expenditure, such as excluding debt interest, but the main focus is on the central government, which, in practice, approximates to general government because local governments in all the Nordic countries are supposed to maintain a balance (Calmfors, Reference Calmfors2020). Some autonomous welfare-related funds do, nevertheless, complicate the picture.

Evidence from Spain suggests that the expenditure rule led to better control of public spending, and similar effects were found for two comparators: Austria and Italy (Herrero Alcalde et al., Reference Herrero Alcalde, Martin Roman, Tranchez Martin and Moral Ace2024). Park and Kim (Reference Park and Kim2025) find, too, that expenditure rules in EU countries have been better at reducing debt-to-GDP ratios than balanced budget rules or debt rules. They note the importance of the stringency of such expenditure rules and of having an institutional framework that makes deviation from the rules politically costly for the government—this reinforces the message from Nordic countries and the Netherlands.

3.2. Scrutiny: Fiscal councils and parliamentary budget offices (PBOs)

Scrutiny is a vital component of any fiscal framework. Fiscal councils have a formal influence, as do parliamentary committees (in the United Kingdom, the Treasury and Public Accounts Committees have the most direct roles), and print and broadcast media also contribute. Provision of information is central to such scrutiny, placing a premium on transparency. New Zealand is a prominent example, putting transparency at the heart of its fiscal frameworks: a 2015 explainer from the country’s Treasury states that its fiscal framework ‘is based on transparency. It emphasises disclosure of information rather than compliance with detailed rules set out in law’.Footnote 3

The relationship between the government and independent fiscal institutions (often referred to as fiscal councils) differs markedly among EU countries, all of which are formally committed to having them. An important function they have is to redress the asymmetry of information between policymakers and other interests (including voters; Jankovics and Larch, Reference Jankovics and Larch2024). In doing so, in principle, they add to transparency, although it is striking that New Zealand, where transparency is at the heart of the fiscal framework, has resisted calls to create an IFI. Some IFIs (notably the OBR and the Dutch Centraal Planbureau) are responsible for official forecasts, and there are variations in access to data, obligations to appear before parliaments and what happens if governments do not fully comply with IFI recommendations.

The interplay between parliaments and the fiscal council varies, with some, as in Italy, being directly connected, but in others, the link is only through appearances at Committee hearings. Fasone (Reference Fasone2022) distinguishes between those which she considers to be within the executive branch (certainly the case for the OBR in the United Kingdom) and those at least partly answerable to the parliament. She argues that a potential role is to overcome the information asymmetry between the executive and the legislature in shaping fiscal policy.

An approach in some countries has been to supplement the fiscal council with a PBO, although as Berger (Reference Berger2023) observed, the latter have been more common outside Europe. Austria and Ireland are recent examples in the EU, and such bodies were created earlier in Greece and Portugal. Outside Europe, PBOs are often the principal external entity, as for those in the United States and Canada. The key feature of PBOs (as the adjective signals) is that they directly support parliamentarians in analysing fiscal matters. An argument in favour of them, as opposed to fiscal councils, could be that they would more directly inform (and thus empower) legislators.

Australia’s PBO offers three main services: responding to requests from members on the costing of policies or related fiscal matters; reporting after elections on the fiscal impact of party programmes; and carrying out research aimed at enhancing public understanding of fiscal policy. In Ireland, the rationale for a new entity was to provide expert assistance to members of parliament on fiscal and budgetary matters. It also conducts research on its own initiative and publishes its findings. Austria’s PBO has a broadly similar role, answering to the lower chamber of parliament (the Nationalrat Footnote 4 ), offering advice to members and committees, and producing reports. The Budget Office is non-partisan and arose from a 2012 five-party agreement to create it, and it makes a virtue of having staff from several disciplines, not just economics. In both the Irish and Austrian cases, informal discussions with practitioners do not indicate problems around confusion of roles with the separate fiscal councils.

There has also been debate in recent years in New Zealand (a richer country, which is now a rarity in not having an independent fiscal entity or watchdog) on whether opting for a PBO rather than a fiscal council would be preferable. While expressing some scepticism, Ball et al. (Reference Ball, Irwin and Scott2024) suggest there would be benefits in a country where, as they see it, the quality of fiscal management has been eroded, especially in reducing debt in ‘good times’. They see enhanced scrutiny as a potential solution to raise the quality of public debate on fiscal policy; this would be consistent with the transparency dimension of fiscal responsibility.

Are there lessons for the United Kingdom? The OBR rapidly acquired a strong reputation, but as it is appointed by the government, its role has been challenged of late and its forecasts of both economic growth and the public finances—especially for the medium term, so central to the approach in successive iterations of the Charter for Budget Responsibility—have often been questioned. No forecaster can be immune from inaccuracy; however, when decisions on tweaking public spending (as occurred in March 2025) to meet fiscal rules 5 years hence are predicated on forecasts likely to be out of date within months, the interaction between the OBR and the government warrants scrutiny. It can be uncomfortable, but it may be too cosy.

The OBR has conducted its own evaluation of its forecasting record (Atkins and Lanskey, Reference Atkins and Lanskey2023), noting particularly that it has been prone to overestimate productivity growth and to underestimate growth in public spending, the latter leading to an underestimation of the government deficit. Its shorter-term forecasts are more accurate than peers, but longer-term ones are less so. Chadha (Reference Chadha2023) argues that the way the OBR is set up does not pay enough attention to public investment and its potential impact on growth or public borrowing. Atkins and Lanskey (Reference Atkins and Lanskey2023: 1) further observe that the OBR is constrained by a ‘legal requirement to condition our central forecasts on stated (rather than anticipated) Government policy’. Other IFIs avoid this risk by having more distance between themselves and the government.

More broadly, while the OBR is respected by insiders, it is open to the criticism that ‘many of its key and consequential assumptions are obscured from democratic debate and oversight’ (Clift, Reference Clift2025: 33). While the OBR is transparent in the sense of publishing its work, assumptions and models, its normative stance is conditioned by its mandate and other elements of the fiscal framework, notably the prevailing fiscal rules. Clift (Reference Clift2025) draws attention to the sidelining of the OBR by the Truss government, which wanted to change the fiscal paradigm. Yet, a reaction to the Truss period was for the incoming government in 2024 to confer still greater authority on the OBR, giving it a form of veto on government policy. This is now enshrined in the 2025 iteration of the Charter for Budget Responsibility.

A more explicit role for parliament could be seen as adding to institutional complexity without concomitant advantages. However, the watchdog function of fiscal councils has to be stressed, as it has to go beyond validating government decisions to encompass warnings of risks to fiscal sustainability. Small, but trusted, fiscal councils, as in Denmark or Ireland, can provide this separation from government, possibly more so than the OBR because of how its role interacts with budgetary decisions. A possible change to how the OBR feeds into fiscal policy could be an obligation on the government to ‘comply or explain’, rather than always to accept the OBR analysis. A PBO, supporting parliamentary committees and facilitating scrutiny by members, could help by having still greater institutional independence.

4. Wider governance considerations

For many countries, episodes of budgetary turmoil have been highly influential in stimulating major reforms of fiscal frameworks (Begg et al., Reference Begg, Kuusi and Kyllianen2023). The Nordic countries in the 1990s and Ireland during the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis exemplify the influence of the narrative of ‘never again’ in recasting frameworks. Similarly, the Budget Responsibility Bill put forward in July 2024 by the incoming Labour government is, at least in part, a reaction to the fiscal turmoil of the short-lived Truss government—albeit only addressing one facet of the UK framework—by requiring an independent assessment (‘fiscal lock’) on future major fiscal announcements.Footnote 5

The balance between rigidity, credibility and flexibility is central, because there has to be scope for reacting to new economic circumstances, offset by sufficient discipline to deter inappropriate policy while avoiding adverse market sentiment. However, over-reliance on rules can be counter-productive. A broader approach has to overcome a bias towards pro-cyclicality that inhibits the building of fiscal buffers and takes account of variations in borrowing conditions, but also needs to move beyond annual budgeting and insufficient transparency (Caselli et al., Reference Caselli, Davoodi, Goncalves, Hong, Lagerborg, Medas, Nguyen and Yoo2022). They note that ‘Australia and New Zealand combine well-developed fiscal frameworks with broad principles (e.g., on debt sustainability) with more flexible numerical rules or guidelines. Chile and Norway also rely on more flexible guidelines and rules supported by strong institutions and transparency on fiscal plans’. The longer term is bound to feature more prominently if only because of known pressures looming over future expenditure from higher pension and health spending linked to ageing.

4.1. Reviews of spending plans

Spending reviews are an important means of correcting the mix of public spending. An OECD article (Tryggvadottir, Reference Trygvadottir2023) puts forward a series of principles for such reviews. It notes that in response to the global financial crisis, savings of public outlays were top of the agenda, but that subsequently the focus shifted to trying to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public spending, with little or no emphasis on reducing aggregate spending. Ireland is cited as a country that has broadened its approach and is notable for having a separate government department responsible for public expenditure, with revenue raising situated within the Department of Finance.

Reviews have to be seen as a process and need to allow adequate time for successive stages to be undertaken convincingly. For this reason, reviews should not be too frequent and should allow time for recommendations to be implemented. The interplay between political and administrative inputs can be crucial. In the Netherlands, the cabinet makes political decisions about the areas to be reviewed, the terms of reference of the review and approval of recommendations. However, a non-partisan working group (coordinated by the Ministry of Finance) is responsible for the analyses underpinning the review. Transparency is assured by releasing all decisions publicly. Norway also has a working group approach, with membership drawn from ministries and agencies, but also including external experts.

Canada and Ireland exemplify evolving approaches to spending reviews. The OECD briefing (Tryggvadottir, Reference Trygvadottir2023: box 1, p 4) notes that the scope of Ireland’s reviews had broadened ‘to encompass policy analysis and evaluation in addition to the focus on expenditure re-prioritisation’. Similarly, Canada’s approach has shifted from expenditure control to, initially, more on the results of spending, then most recently to the more strategic question of explaining how outcomes are realised. Both point to the integration of performance-based budgeting as a means of adapting spending in light of information on how past programmes performed.

The OECD assessment is relatively sanguine about the UK approach, notably praising its approach to monitoring, guidance for spending departments and the process of developing departmental plans. However, although an initial limited review was undertaken by the incoming government in 2024, the more extensive one in 2025 was the first since 2021. As illustrated in an Institute for Government explainerFootnote 6, the approach in the preceding decade was to alternate between more extensive reviews and lighter touch spending rounds. The reviews are not binding, illustrating the rather ad hoc approach, relying on the government initiating it, rather than being systematic.

The 2025 review again favoured spending on health, as well as more for defence, local government, justice and public investment, while overseas aid was cut to enable more to be spent on defence. The Institute for Government gave a cautious welcome to the 2025 review, but expressed reservations about it being a strategic shift.Footnote 7 As Paul Johnson observed, there might be quibbles ‘over precise allocations, but what we saw was a perfectly reasonable set of prioritisations’.Footnote 8 However, he also stressed that it ‘was not a “fiscal event” in the sense that total spending levels had already been announced’.

4.2. Escape clauses

Escape clauses and possible revisions of fiscal rules pose dilemmas. Overly rigid rules and strict adherence to them when economic logic suggests different policies can become counter-productive, but if escape clauses are too easily triggered or changes in rules are too easy and resorted to too often, their impact on stabilisation risks being eroded. To forestall risks of loss of credibility, repeated sidelining or revision of rules should be avoided. Equally, rules have to be understood as a means to an end, not an end in themselves: some of the criticisms of the UK approach suggest this message has been neglected.

How much flexibility to build into a fiscal framework (not just fiscal rules) and a reasoned process for deciding how to implement any formal escape mechanisms are crucial matters. Weise (Reference Weise2023: 7) finds that about half of the national rules (bearing in mind that many countries have several rules) have escape clauses, but also that many are linked to the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact. He also observes that the rules lacking escape clauses largely concerned ‘government levels (local government) or budgetary elements (long-term targets, revenue rules, etc.), which were less sensitive to the shock or because other flexibility elements could be used’. Weise also notes that IFIs were involved in the decision on triggering the escape clauses of around a quarter of fiscal rules. In a few cases, the IFI had the sole responsibility, but more often the IFI contributed mainly alongside the Ministry of Finance, and sometimes other bodies, such as the central bank or the national court of auditors.

An IMF note on MTFFs asserts that they ‘need to be an integral part of fiscal and budgetary decision-making and reporting. Without this, the MTFF can remain a paper exercise’ (Curristine et al., Reference Curristine, Adenauer, Alonso Albarran, Grinyer, Tee, Wendling and Moretti2024: 2). Yet, as Weise (Reference Weise2023) finds, a link from the MTFF to annual budgets is weak in many EU countries, despite a steady strengthening of such frameworks. As Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Leslie, Pacitti and Smith2019: 22) imply, this is linked to the political economy of rules, and they observe that ‘what gets excluded gets exploited’. How to provide flexibility while maintaining discipline is, therefore, an enduring challenge for fiscal frameworks.

Exit from escape clauses is also challenging. Given that an escape period will have increased debt-to-GDP ratios, the options are to set a pathway to end the derogation when the immediate emergency ends, or, as Caselli et al. (Reference Caselli, Davoodi, Goncalves, Hong, Lagerborg, Medas, Nguyen and Yoo2022) suggest, to recalibrate the rules. Caselli et al. note that in Canada and Australia, a factor taken into account is whether labour market evidence supports an end to the escape.

Germany’s recent experience illustrates the complications: What the Constitutional Court decreed in its 2023 decision rebuffing the government was interpreted to mean that the conditions no longer justified emergency action. Moreover, the ‘judgement states that the budgetary principles of yearly budgeting (Jährlichkeit) and annuality (Jährigkeit) also apply to the exception clause of the debt brake’ (German Council of Economic Advisers, 2024: 1). Nevertheless, the start of 2025, Germany has emerged as an instructive case (Box 1).

Box 1. A German revolution?

The decision by the outgoing Bundestag on 18th March 2025Footnote 9, following the February election, to overturn the constitutional basis of the debt brake was significant. It was done by relying on the lower house’s pre-election membership, which had just enough votes to attain the required two-thirds majority, thereby excluding the populist parties, which had done well in the election. In essence, the new provisions allow for the debt-to-GDP ratio to rise, to enable both higher military spending and increased infrastructure investment.

Before this change, the lesson to take from Germany was negative: Do not tie fiscal policy to so stringent a debt rule. It had kept the debt-to-GDP ratio around the EU benchmark of 60% of GDP, but at the expense of a shortfall in public investment, aggravated by rather convoluted arrangements—notably regarding how depreciation is accounted for—for publicly owned entities (such as the deutsche bahn (DB) rail company) deemed to have commercial activity. The need for a viable means of increasing military spending was an immediate reason for overturning the debt brake, but there had been growing dissatisfaction with it (German Council of Economic Advisers, 2024), exacerbated by a Constitutional Court ruling on the legitimacy of government’s resort to emergency lending. The Bundesbank (2025), too, offered a cogent analysis of why a new approach was needed to ensure higher public investment.

The new arrangement in Germany can be thought of as a cautious return to a golden rule, in place up to 2009. The German version had come in for criticism because of the well-known problem of departments and agencies seeking to bend the rules on what constitutes investment (Reuter, Reference Reuter2020). It can also serve as a negative lesson on the perils of excessive rigidity, given the adverse impact it had on public investment.

While the new approach in Germany will undeniably loosen the fiscal shackles, there are practical problems to be solved. A first is the interplay with EU rules, which, although notionally binding on all Member States, are in practice more so for euro area members. In a careful analysis, Steinbach and Zettelmeyer (Reference Steinbach and Zettelmeyer2025) note that, even exploiting the various flexibility mechanisms in the recently revised EU economic governance framework, Germany could easily fall foul of the conditions under which Member States are allowed to neglect the level of debt. They argue that the proposed new infrastructure fund, in addition to higher military spending, would be in breach of EU rules, which continue to use a debt ratio of 60% of GDP as a benchmark. Raising the threshold to, say, 90% could alleviate the risk, but the political economy implications would be awkward, although the European Commission has - so far - opted to allow Germany (and other Member States) to deviate from EU rules in view of defence imperatives. Even so, the lesson for the United Kingdom is to be wary of a rigid debt threshold.

Second, Germany is notorious for submissions to its constitutional court resulting in decisions that stymie fiscal initiatives. Indeed, a decision by the court rejecting the government’s contention that a pandemic-related relaxation of the debt brake could continue prompted the revision just enacted. For the United Kingdom, a possible tension is between calls for a strengthening of the legal basis of the fiscal framework and the potential for judicial reviews, which call into question government decisions.

Source: Own elaboration.

4.3. Debt ceilings, targets or benchmarks

Whether to have a ceiling or a reference value for public debt is an awkward question. The regular battles in the US Congress over raising the debt ceiling, sometimes accompanied by a shutdown of the federal government while the wrangling continues, signal what not to do. However, the use of a ceiling appears to be valuable elsewhere. Debt limits in constitutions potentially impose a very hard budget constraint—for example, in Poland. For members of the Eurozone, 60% of GDP is a longstanding threshold, albeit with generally weak enforcement. Where, as in Slovakia, the national debt ceiling coincides with the EU threshold, it is the national one that bites: in Slovakia, there are graduated sanctions as the debt level comes closer to the ceiling.

In his overview of the five Nordic countries, Calmfors (Reference Calmfors2020) explains that Iceland and Sweden have targets of 30% and 35% of GDP, respectively, for public debt, although for Sweden, the target has no operational role. However, there is a link to the long-run aim to maintain a small public sector surplus to provide for future calls on the public finances, notably from demographic trends, a goal revised every 8 years. Denmark has a debt ceiling, but it is set at a high level of some three times the actual debt. Another approach, notably in Australia and in New Zealand, is to have net public debt as a goal to be pursued, but without attaching a specific numberFootnote to the level. Rather, it is about fiscal sustainability in a more qualitative sense.

4.4. Decision-making

Fiscal rules ought to constrain governments, but should not deter them from adopting rational economic policies. In the United Kingdom, the decisions taken by Rachel Reeves in her spring 2025 statement would, in a favourable scenario, mean that she would not only meet her fiscal rules but also maintain the small amount of ‘headroom’ planned a few months previously. Notably, the revised plans would deliver this outcome to the second decimal place, yet the fact that the previous plans had so quickly become unattainable should have shown the absurdity of this position. Martin Sandbu of the Financial Times, citing Ben Zaranko of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, writes that ‘policy is over-responding’, accentuating the volatility of budget policy.Footnote 10

Instead, the question should be how to render fiscal frameworks less exposed to the inevitable changes—be they cyclical or geopolitical—in the backdrop to fiscal decision-making. One answer is to have fewer fiscal ‘events’: once a course is set, it should (in the absence of an extreme event) be maintained. Another is, as in several other countries, to entrench a medium- to longer-term approach, in which the government faces political condemnation if it reneges. The objection that governments need to be able to adapt to dramatically new circumstances is disingenuous: yes, they need to retain flexibility, but that is not the same as being able to make frequent, often politically rather than economically motivated, changes.

In this context, the Swedish and Dutch approaches have distinctive features. They (and various other countries) aim to set expenditure paths over an extended period, favouring the duration of the parliamentary period. This approach still allows for annual budgets and for flexibility in responses to the unexpected, but it also pushes governments to be more strategic about planned expenditure. While the United Kingdom does plan for the medium term, the annual budget remains very much the central decision-making point.

In Sweden, as set out succinctly in an explanatory document from the RiksdagFootnote 11, there is a two-stage process. First, the parliament votes on the expenditure ceiling for the next 3 years, as well as the total expenditure to be allocated in year t + 1; then a second vote allocates the spending among headings of expenditure. The expenditure is set in nominal terms with a margin built in to allow for either cost inflation or other contingencies.

In the Netherlands, the government sets out expenditure plans for the 4-year term of office in real terms, distinguishing between central government, social security and care. According to a Ministry of Finance explainer, budgetary ‘policy is determined by the government’s expenditures and revenue plans, and expected national and international economic developments over the next 4 years’.Footnote 12 The underlying principle in budget management is a trend-based fiscal policy in which revenue plans are made to meet the agreed expenditure. Deviations in revenue or unemployment related expenditure are allowed, providing a degree of macroeconomic stabilisation, but revenue windfalls may not be used to finance additional spending. This conjunction means fiscal policy is less likely to be pro-cyclical.

Other countries, such as Finland or Denmark, also plan in real terms, but there are respectable arguments for either the real or nominal approach. With longer-term pressures from ageing and the green transition, as well as the more immediate imperative of raising defence expenditure, strategic shifts in public spending are bound to loom larger in decision-making. Denmark has also been a leader in projecting budgetary expenditure in the longer term, and the Centraal Planbureau in the Netherlands regularly produces similar analyses with 8-year horizons. The OBR, too, explores the long-term demands on public expenditure in its Fiscal Sustainability Reports, stretching 50 years into the future, but its impact on current fiscal debates is not very visible.

4.5. Net worth

The public sector’s net worth is advocated by some commentators as a better way of looking at fiscal sustainability than public debt, which, by definition, is only one side of the balance sheet. Net worth can be measured in various ways, each with differing properties and implications for policy, as a 2021 note by the Office of National Statistics explains.Footnote 13 The arguments for and against using net worth are set out in a polemical exchange between John Crompton and Ben Zaranko.Footnote 14 The former stresses that net worth is a measure of financial health and also helps to shed light on the inter-generational consequences of public investment. Zaranko, while not against the concept, worries that it could be used to drive borrowing too high, posing risks for fiscal sustainability. He, therefore, concludes that it would not make a good fiscal rule or target.

Yet, it is undeniable that some countries find it helpful. As Buckle (Reference Buckle2018: Table 1, p. 11) explains, one of the recent additions to the principles underpinning New Zealand’s (well-regarded) fiscal framework is ‘achieving and maintaining levels of total net worth that provide a buffer against factors that may impact adversely on total net worth in the future’. However, Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Leslie, Pacitti and Smith2019) show that, by international comparison, the United Kingdom has a relatively low net worth, partly as a consequence of previous decades of selling off public assets. Norway (obviously boosted by its management of oil and gas revenues) is a global leader, but Australia could also be an example for the United Kingdom.

Even without an explicit rule or focus on net worth, innovation in the implementation of public investment can potentially provide answers as part of a broader recasting of the fiscal framework. Providing incentives for pension funds and other major investors of funds could offer win-win solutions. Bakker et al. (Reference Bakker, Beetsma and Buti2024: 103), again in the EU context, stress the need for ‘a commitment of public authorities to create predictable policies and complete envisaged investments’. However, care is needed to ensure that the quality of public investment is assured; in this context, a key consideration is whether the investment contributes to growth (Begg and Cicak, Reference Begg and Cicak2024).

Germany’s about turn on the debt brake is motivated by the need to boost public investment in infrastructure and can equally be applied to the United Kingdom after years of under-investment in public assets and its legacy in, notably, inadequate infrastructure. Clearly, public investment alone cannot be expected to fill the gap, and past UK experience with public-private funding arrangements has been far from an unalloyed success (Sheppard and Beck, Reference Sheppard and Beck2025), although the same authors argue that, post-COVID, Ireland has succeeded in making effective use of such partnerships. They attribute the latter to various features of the Irish approach from which the United Kingdom could learn, notably what they call ‘consensualism’ and a culture of openness, as well as greater pragmatism.

4.6. Transparency

New Zealand is also noteworthy for putting transparency at the heart of its fiscal framework, along with fiscal responsibility. There is a debt anchor, but not a formal fiscal rule, and successive governments have debated but eschewed introducing one. Caselli et al. (Reference Caselli, Davoodi, Goncalves, Hong, Lagerborg, Medas, Nguyen and Yoo2022) report that New Zealand committed, after the pandemic, to a return ‘to a measure of operating balance to a surplus and aiming for small surpluses thereafter, and a net debt ceiling to ensure a sufficient fiscal buffer to address economic shocks or natural disasters’. In practice, as Blanchard et al. (Reference Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer2021) observe, the New Zealand model is about fiscal standards rather than explicit rules, and the level of transparency is the mechanism to make it effective. It is an open question whether such transparency could work well in a country like the United Kingdom.

5. Conclusions and a menu for change

The stark conclusion of the Institute for Government assessment is that ‘the original purpose of our fiscal framework—to embed a clear and comprehensive fiscal strategy and to force difficult trade-offs—has been lost’ (Tetlow et al., Reference Tetlow, Bartrum and Pope2024: 40). They believe change needs to go well beyond tweaking the current fiscal rules to include governance changes, better separation of investment and current spending and more systematic spending reviews. In much the same vein, Chadha asserts ‘that the post-2010 fiscal settlement has failed’, going on to bemoan being ‘in thrall to arbitrary rules that do not match society’s broader demands’ (Chadha et al., Reference Chadha, Kucuk and Pabst2021: xvii). Among others, Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Leslie, Pacitti and Smith2019) and the various contributors to Chadha et al. (Reference Chadha, Kucuk and Pabst2021) put forward a plethora of suggestions for how to enhance the UK approach.

Since coming to power in the summer of 2024, the Labour government has taken steps to improve the fiscal framework, but it has also proved to be reluctant to be more radical. In some respects, the government faces a (familiar) trap: having campaigned on promises of fiscal discipline, it would be roundly condemned if it sought to recast the very rules it professes to be ironclad. Yet in other respects, to invert a well-known aphorism: ‘if it’s broke, fix it’. In doing so, the United Kingdom should aim to learn from practices elsewhere, even if it is accepted that adopting what works in one jurisdiction might not be straightforward. The case for looking at public assets has been recognised, and public investment will be a greater priority. However, the much-criticised ‘rolling’ fiscal rule remains (though tweaked), the interplay between the OBR and the government is unsatisfactory, and the very limited expenditure rule covering the welfare budget—consistently overshotFootnote 15—imposes no genuine constraint.

Although the United Kingdom is some way from being bottom of the class, the evidence from countries that have much better fiscal indicators is, or should be, persuasive in stimulating a new approach. Fiscal governance must be grounded in a robust institutional framework and long-term perspective. It is therefore essential that rules are not just legislated, but embedded in historical or constitutional contexts, with trust, accountability and transparency as watchwords to stress. In what follows, feasibility may be in doubt in some cases, and what is advocated is not a wholesale adoption of a model in another country; they all face criticisms. Yet, the United Kingdom could benefit from a selective approach to the adoption (or adaptation) of elements that deliver results elsewhere; hence, what is offered is more a menu of proposals for change than firm recommendations. These are:

-

• Even if politically difficult, the first is to change the fiscal rules to put more emphasis on setting a pathway for aggregate expenditure and providing incentives for growth-related public spending.

-

• Giving priority to public investment by, in effect, restoring a golden rule in the 2025 version of the Charter for Budget Responsibility ought to favour investment: this separate rule for investment is to be welcomed, despite the same insistence as for the current balance on a rolling target years ahead. But instead of relating it narrowly to public investment, with the attendant problems of definitions of what to include, introduce a test of whether the spending is growth-promoting, to be validated by independent assessment. This could be either through the OBR or a specialised body, thereby reducing the scope for governments to game the system.

-

• Reduce the frequency of major fiscal events, maybe aiming for a strategic one at the start of a new parliament, with annual updates. In the Netherlands, there is a single annual decision-making event on spending in the spring, within the multi-annual framework of the expenditure rule, while decisions on taxes and social contributions are taken in the late summer.

-

• Revamp the National Infrastructure Commission to include a mandate to bring together funding packages, as in New Zealand, where the mandate is to advise the government on planning and implementing major projects, including by combining public and private funding.Footnote 16

-

• Fix the roof while the sun is shining by institutionalising the building of fiscal buffers when the economy is buoyant. Generating fiscal space is politically difficult, and the inevitable tendency is to treat any improvement in fiscal arithmetic as an opportunity to boost spending or cut taxes. Here, the Dutch rule on not increasing spending when there is a revenue windfall should be considered.

-

• The tentative steps by the government in the 2024 budget to pay attention to public sector net worth should be further developed, learning lessons from New Zealand, Australia and other countries with longer experience of this metric.

-

• While the OBR comes out well by comparison with many fiscal councils, the shift in its role to give it a de facto veto on government decisions risks becoming counter-productive, a concern accentuated by its embedding within the executive. Instead, its watchdog role should be enhanced and efforts made to boost its wider visibility and links with parliament.

-

• Tetlow et al. (Reference Tetlow, Bartrum and Pope2024) set out a range of recommendations for how the OBR mandate could evolve, including having a role at the start of a new parliament in determining the fiscal space an incoming government has, assessing escape clauses and whether the government’s approach is consistent with fiscal sustainability, not just the letter of fiscal rules.

-

• To complement the OBR and to provide greater independent scrutiny, explore the creation of a PBO.

This article has drawn attention to many options in fiscal frameworks elsewhere that appear to foster better fiscal policy. Not all can be easily grafted into the UK system, or should be, but many offer viable solutions to the problems that have plagued UK fiscal policy, the evident threats to fiscal sustainability of public debt stubbornly close to 100% of GDP and crowding out of public expenditure by interest payments. Iron-clad adherence to fiscal rules has its political virtues, especially for a left-of-centre governing party, and there are bound to be political risks in recasting the fiscal framework. But boldness can also be a virtue: What about now?