3.1 A Classic of Democratic Theory

If asked which text on democracy can claim the status of a global classic, one will accord a place – perhaps even first place – to the second edition of Hans Kelsen’s (1881–1973) Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (The Essence and Value of Democracy), published in German in 1929.Footnote 1 Neither before nor subsequently has a theory of modern liberal democracy – of constitutional democracy – been presented that can compete with Kelsen’s as a classic or in its overarching coherence and consistency. Kelsen’s political theory of modern mass democracy is characterised both by the fact that it partly modernises, partly recalibrates and partly corrects the older concepts of democracy and by the fact that it still retains, in many aspects, an enduring timeliness marked by its singular originality.Footnote 2 These distinctive facets are the consequence and expression of the coincidence of two factors, the first of which concerns the contemporary historical context and the second of which concerns the author of the theory. On the one hand, the theory is a considered response to the challenges facing the young democracies in Central Europe of the 1920s and 1930s that had only adopted republican forms of government after their defeat in the First World War. On the other hand, Kelsen, perhaps the most creative legal scholar of ideology-critical scientific modernism, was at the same time one of the protagonists in the so-called Weimarer Richtungs- und Methodenstreit (Weimar controversy on the essence and the role of the constitution). The controversy concerned the legal and extralegal significance of the constitution in general and, more concretely, how the sociopolitical and ideological conditions and effects of the constitution could be formulated within a rigorous, juridical conceptual framework.

However, Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, published in 1929 during the Great Depression, is not the great work of a lonely genius in an ivory tower or the intellectual product of a single ingenious moment. Rather, the work has a history, a prehistory and an aftermath, which presents itself as an iterative process influenced by numerous factors, spanning several decades and reflecting Kelsen’s personal experiences in Austria, the German Reich, Switzerland, and the United States of America. This story will be told here in three intertwined threads: First, it concerns Kelsen’s career, which takes place between academia and legal practice in the decade after the First World War; second, it relates to the different stages of development of his concept of democracy; and third, it involves the influence of his other scientific oeuvre on his theory of democracy.

3.2 Main Characteristics of Kelsen’s Theory of Democracy

However, before considering these different strands of development, it would be appropriate to briefly indicate the basic elements of the 1929 edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie. It is not within the scope of this article to present and analyse Kelsen’s classic theory of democracy in detail. It must suffice to concisely summarise the essential characteristics that distinguish Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie from contemporaneous attempts to theorise democracy. Six aspects should be mentioned in this respect:

First, the realism underlying Kelsen’s theory of democracy, that is, its orientation towards real, concrete conditions, should be emphasised. Kelsen and his Pure Theory of Law are widely reproached for an empirically resistant and entirely abstract, if not empty, formal constructivism. In sharp contrast, Kelsen’s theory of democracy encompasses the concrete, sociocultural factors of modern large-scale and mass democracies in a particularly direct and assertive manner. Kelsen emphasises several times that the ideal or ideology of democracy must be conceived, understood and realised in light of the existing social, psychological, cultural, and political conditions for the realisation of democracy. The consideration of real, concrete sociocultural factors as well as the ideological relativism of modern democracy can be understood as positioned against democratic universalism.

Second, the central determining value of democracy is freedom, which is self-determination. However, Kelsen shows that freedom and self-determination in liberal democracies do not occur in the singular but in a twofold sense. The consequence and expression of this is that two concepts of freedom and two subjects of freedom must be distinguished from and related to each other: The individual is confronted with the public collective and with collective self-determination; from the point of view of the individual, self-determination sub specie of democracy mutates into co-determination. This ‘metamorphosis of freedom’ is fundamental to the conceptualisation of the majority principle and the protection of minorities.Footnote 3 Moreover, the distinction and juxtaposition of the two freedoms prevents the polar legitimisation of the rule of the collective (the people) on the one hand and the freedom of the individual on the other from being fused into a collectivist whole that absorbs the freedom of the individual.

Kelsen, third, does not conceive of the people in terms of any kind of substantial homogeneity, of a ‘we’ that unites all. Having been born in Prague, to Jewish parents, then a city of the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire, with the family subsequently moving to the multiethnic, urban microcosm of the Imperial capital, Vienna, Kelsen does not exaggerate the nation mythically but takes it seriously in its heterogeneity and amorphousness. Accordingly, the political unity that a nation needs to understand itself as such is neither a given nor a permanent feature but a unity that must always be fought for anew in negotiation and compromise.

Fourth, Kelsen’s theory of democracy is pluralistic, accounting for the pluralism of associations and the social dynamics in which political integration can succeed but also fail. He frees parliamentary democracy from the internecine ideological conflict arising from myths of identity and representation – Kelsen unmasks the identity theorem and the idea of representation as fiction. Parliamentary democracy, with its specifically adversarial-dialectical procedure, proves to be the ‘only real form in which the idea of democracy can be fulfilled within the social reality of today’ in view of the heterogeneity, complexity and intricacy of modern, large-scale societies.Footnote 4

Fifth, Kelsen defines majority rule, which is essential for the democratic decision-making process, as based not primarily on equality, but on – equal – freedom: if not everyone can be free, that is, only subject to the rules they have agreed to establish through self-determination, then at least the majority should be. What is decisive for Kelsen, of course, is that the democratic act of decision-making is not thought of as a singular, static event but as a dynamic process in which an act of decision-making is situated within a continuum of past, present, and future decisions. This dynamic procedural view makes it apparent why the simple absolute majority is the most democratic decision-making quorum and why the majority principle is intimately connected with the protection of minorities. Majority rule presupposes the minority as a constitutive element. Kelsen’s advocacy of proportional representation, which best reflects the different political interests of the people and the interplay between majority and minority, is an essential aspect of this relationship. ‘The power of social integration’, which is inherent in the majority principle as tempered by the protection of minorities, is essentially attributed by Kelsen in parliamentary democracy to the social technique of compromise, that is, mutual yielding for the sake of togetherness. He thus rejects, from the outset, the intelligibility of the notion of an absolute majority – the impossibility of the absence of a minority – within democracy.Footnote 5

Last, his theory of democracy integrates both the political parties and the constitutional jurisdiction (with the competence of judicial review), in contrast to prevailing trends, especially in the Weimar theory of constitutional law. Kelsen’s conceptualisation holds these actors to be without either an essential or necessary opposition to popular rule; by contrast, these actors exist as facilitators of the continued stability of democracy. Additionally, in marked contrast to a significant body of political theory and jurisprudence, which advocates for a ‘democratisation of administration’, Kelsen pleads for an ‘autocratic’ administration, which is bound to – and dependent on – the will shaped by democratic legislation.

3.3 The Author: Constitutional ‘Architect’ and Constitutional Judge, Professor of Public Law, and Public Intellectual

In 1929, the year of publication, the author of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie was probably by far the most famous jurist in Austria. Kelsen, who came from a modest Jewish background, had made an unprecedented career for himself in the previous decade and gained a significant reputation both within and outside academia.Footnote 6

Kelsen’s rapid rise began with the end of the First World War. He had been a Privatdozent since 1911 and an associate professor at the Vienna Faculty of Law and Political Science since 1918. He witnessed the end of the war as the assistant (Referent) of the last Imperial and Royal (k.u.k.) Minister of War, Colonel General Rudolf Stöger-Steiner (1861–1921). At the beginning of November 1918, at age thirty-seven, he was engaged by the first State Chancellor of the Republic of German Austria (Deutsch-Österreich), the Social Democrat Karl Renner (1870–1950), to be his constitutional advisor. Kelsen’s main task was to help draft the definitive constitution of the Republic of Austria. This rightly earns him the title of ‘architect’ of the so-called B-VG, the Federal Constitutional Law of 1 October 1920. In 1919, two decisive career steps followed: he succeeded his late teacher Edmund Bernatzik (1854–1919) as a member of the recently established Constitutional Court (Verfassungsgerichtshof) and became a full professor of constitutional and administrative law at the University of Vienna; he held both posts in parallel until 1930, when he left Vienna for Cologne as a result of the rapidly deteriorating political conditions, which especially affected him personally. However, until then, Kelsen experienced golden Viennese years. He was probably the most active and effective judge of the Verfassungsgerichtshof, the Austrian Constitutional Court. He saw his Vienna School of Legal Theory grow and flourish. Its diversity fostered the ideal intellectual environment for the development of the Pure Theory of Law. Important legal scholars emerged from his circle of students, such as Adolf Julius Merkl (1890–1970) and Alfred Verdross (1890–1980). Kelsen became the star of the Viennese law faculty and maintained contact with Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and the Austro-Marxists Max Adler (1873–1937) and Otto Bauer (1881–1938). In general, the Vienna School of Legal Theory entertained diverse contacts with other Viennese circles, such as the Psychoanalytic Society around Sigmund Freud, the Viennese circle of logical empiricists around Moritz Schlick (1882–1936) and Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970) or the Austrian School of Economics around Carl Menger (1840–1921) and Friedrich von Wieser (1851–1926), to which Kelsen’s classmate Ludwig Mises (1881–1973) also belonged. Kelsen’s broad range of nonacademic engagement earned him the reputation of a public intellectual.

In 1922, the Staatsrechtslehrervereinigung, the Association of German Scholars of Public Law, was founded – the first of its kind in the German-speaking world – on the initiative of the renowned public law scholar Heinrich Triepel (1868–1949). It provided a forum for senior scholars of public law who taught constitutional or administrative law at German and Austrian universities, as well as at the German University of Prague to initiate sustained debate on contemporaneous and foundational aspects of the law in annual meetings from 1924 onwards. The Association established a community of discourse that, although dominated by German public law scholars, always encompassed the entire German-language domain of discourses on public law and was important for the development of the discipline. Here, Kelsen, who was dismissed from the Austrian Constitutional Court in 1930 and went to Cologne for three years, encountered the anti-positivists Heinrich Triepel, Carl Schmitt (1888–1985), Rudolf Smend (1882–1975), Hermann Heller (1891–1933) and Erich Kaufmann (1880–1972), as well as representatives of traditional legal positivism such as Gerhard Anschütz (1867–1948) and Richard Thoma (1874–1957). As the main representative of a critical legal positivism, Kelsen clashed with them in the Weimarer Richtungs- und Methodenstreit, in which the essence, the function, the interpretation and the application of the constitution were at stake. Kelsen’s positions included adherence to the parliamentary system and to the indispensable role of political parties and the democratic compatibility of the constitutional jurisdiction with parliamentary democracy founded on the rule of law. These stances brought him into opposition with a popular strand of Weimar constitutional jurisprudence that was critical of parliamentarism, the role of parties, and the compatibility of democracy and constitutional jurisdiction, and, ultimately, he also conflicted with the main political currents in Austria and Germany. In 1933, as a result of the introduction of the National Socialist racist law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums), he was one of the first academics to be suspended from the University of Cologne. From then on, Kelsen had to live in exile, from 1933 in Switzerland, then from 1940 to his death in 1973 in the United States of America, whose citizenship he acquired in 1945.

3.4 The Essence and Value of Democracy in Kelsen’s Oeuvre

In contrast to Carl Schmitt, who is distinguished by a predominantly aphoristic style and situational mode of thinking, Kelsen was an emphatically systematic thinker. Rejecting the exception as leitmotif, he focused on the surrounding order as the orientation for his thought. He ran, if one may say so metaphorically, not an intellectual sprint but, rather, an intellectual marathon. It would perhaps be even more pertinent to designate Kelsen as a thinker who ‘acquired’ a definite position on topics in several stages. That is, Kelsen tended to deal with topics several times and developed the views expressed in his first works in light of recent developments and opposing views, visibly shaping them into a body of thought of high clarity, systematic coherence, and argumentative resilience. In this way, he progressively improved and perfected his views over time.

This systematic thinking can be particularly impressively observed in Kelsen’s main academic interest, legal theory: Kelsen already laid the foundation for his approach in his habilitation thesis Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre from 1911.Footnote 7 The basic rudiments, if they may be described as such, of the concept of law that would later be called ‘Pure Theory of Law’ were formed in this text. However, a whole series of elements that are today associated with the Pure Theory of Law were still missing, such as the hierarchical structure of the legal order (Stufenbau der Rechtsordnung), the doctrine of the basic norm, or the monistic concept of the interplay of legal systems. Kelsen develops these only in the following decade. He did so in collaboration with a circle of young scholars who gathered around him, known as the Vienna School of Legal Theory. At the beginning of the 1920s, the theoretical edifice was so well differentiated and consolidated that Kelsen dared to write the first complete exposition of his critical legal positivism, even though it did not yet bear the title Reine Rechtslehre; this theory emerged in Allgemeine Staatslehre (General Theory of the State) published in 1925 at the zenith of his Viennese period.Footnote 8 The much shorter first edition of Reine Rechtslehre,Footnote 9 published nine years later, was written after Kelsen had been forced to leave Nazi Germany in April 1933. The text was a compact summary of his new style of thinking condensed to the essentials. After stopovers in various places, Kelsen, who had been forced into exile, found a new home in Berkeley, California. Here, in 1945, the year of his naturalisation as a U.S. citizen, he wrote the General Theory of Law and State,Footnote 10 adapted to legal thinking in the Anglophone world. The greatest developmental thrust since 1925 came in the second edition of Reine Rechtslehre,Footnote 11 written in German in 1960. This work can be regarded as Kelsen’s mature masterpiece. However, Kelsen, by now over eighty years old, continued to tinker with his edifice of ideas and expanded the theory of law into a theory of norms; the posthumously published work Allgemeine Theorie der Normen (General Theory of Norms) bears witness to this development.Footnote 12 Accordingly, Kelsen developed and modified his critical legal positivism over more than half a century, i.e. from 1911 to 1968 (1979).

A similar approach can be demonstrated, although perhaps not quite as spectacularly, in Kelsen’s contributions to democratic theory. Here, too, a consistent, if not quite so stringent, development can be seen. It is advisable not to focus too narrowly since connections are not only conveyed via the subject sensu stricto, that is, democracy as a concept of government, but also via related topics, the underlying theoretical approach and, finally, the methodology. In this respect, three categories of relevant contributions can be distinguished, with admitted overlaps: first, writings that deal with democracy as a phenomenon in its entirety; second, those that have a direct thematic reference to democracy but only address partial aspects; and third, those that lack this direct thematic reference but that are important for Kelsen’s specific conception of the theory of democracy for other reasons – namely, methodological and epistemological reasons.

The first group can be stated quite precisely; it consists of a total of sixteen contributions written by Kelsen over three and a half decades (1920–1955). It is therefore hardly an exaggeration to say that Kelsen made a lifelong scholarly effort to explore the nature and value of democracy. The following publications are listed in chronological order:

- 1920

Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (The Essence and Value of Democracy), 1st ed.Footnote 13

- 1921

Demokratisierung der Verwaltung (Democratisation of the Administration)Footnote 14

- 1924

Marx or LassalleFootnote 15

- 1925

Allgemeine Staatslehre (General Theory of the State)Footnote 16

- 1925

Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (The Problem of Parliamentarism)Footnote 17

- 1926

Staatsform als Rechtsform (Form of Government as Legal Form)Footnote 18

- 1926

Soziologie der Demokratie (Sociology of Democracy)Footnote 19

- 1926

Demokratie (Democracy)Footnote 20

- 1927

Demokratie (Democracy)Footnote 21

- 1929

Geschwornengericht und Demokratie. Das Prinzip der Legalität (Jury Court and Democracy. The Principle of Legality)Footnote 22

- 1929

Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (The Essence and Value of Democracy), 2nd ed.Footnote 23

- 1932

Verteidigung der Demokratie (Defence of Democracy)Footnote 24

- 1937

Wissenschaft und Demokratie (Science and Democracy)Footnote 25

- 1937

Die Parteidiktatur (The Party Dictatorship)Footnote 26

- 1955

Democracy and SocialismFootnote 27

- 1955

Foundations of DemocracyFootnote 28

It is not only in quantitative terms that Kelsen’s Viennese years, or more precisely, the years when he served as both a professor at the University of Vienna and a member of the Austrian Constitutional Court (1919–1930), clearly stand out: In the 1920s, alone, Kelsen wrote ten articles on the theory of democracy. The short, 119-page monograph Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (On the Nature and Value of Democracy) from 1929 forms the conclusion and climax both chronologically and in terms of content. This can be easily explained both in general historical and biographical terms: Democracy in the First Republic (as it is called in Austria) still has to be explained, practiced and affirmed in its essence and value from a scholarly perspective. Numerous contributions arise from Kelsen’s lectures that were never intended solely for a professional legal audience but for wider circles. Accordingly, they reflect the sociopolitical responsibility that Kelsen may have felt as a jurist, constitutional judge, and constitutional advisor to the State Chancellor. In his writings on democratic theory, one can observe how Kelsen unites his political commitment to liberal (‘constitutional’) democracy with his strict academic demands. At the same time, it becomes clear that Kelsen saw himself challenged by the circumstances of the timeFootnote 29 to establish, through rigorous methodology, a scientific foundation and encapsulation for democracy – a scientific theory that Kelsen further reshaped and perfected according to subsequent political experiences and challenges.

Whoever seeks to explain the emergence and evolution of Kelsen’s writings on the theory of democracy, however, must also consider at least two other strands of development from an earlier origin. These do not focus on the development of a theory of democracy but rather explorations towards a theory of democracy. On the one hand, there is Kelsen’s preoccupation with topics that deal with partial aspects of democracy. These contributions extend back to even the beginnings of Kelsen’s scholarly publishing activity: The first to be mentioned here are Kelsen’s contributions on questions of electoral law. His second and third publications, from 1906 and 1907, when Kelsen had only just completed his studies, were on electoral law.Footnote 30 In 1907, Kelsen presented an extensive commentary on the so-called Reichsratswahlordnung. Until 1918, the Reichsrat was the parliament of the Cisleithanian, that is, the Austrian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, consisting of two chambers, the Herrenhaus, the upper chamber, and the Abgeordnetenhaus, the lower chamber. The Reichsratswahlordnung regulated the election of the members of the Abgeordnetenhaus. Questions of electoral law would occupy Kelsen again in the early years of the Republic (1918–1920) and repeatedly thereafter. Kelsen regularly expressed his views in response to political events of the time, advocating for a consistent system of proportional representation.Footnote 31 The second thematic strand concerns the connection between political education and the democratic form of government. Kelsen, who became involved in workers’ education in the form of the Wiener Volksbildung (Viennese People’s Education) shortly after his habilitation, realised early on the importance of the political education of the broad masses for the functioning of a liberal mass democracy.Footnote 32 The third thematic aspect is Kelsen’s critical examination of (Austro-)Marxism and socialism, which at the time claimed to represent the new model of society and could be sure of attracting attention after the October Revolution in Russia; Kelsen summarised the most important results of his critical engagement and analysis in the monograph Sozialismus und Staat (Socialism and State), published in 1920Footnote 33 – at the same time as the first edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie. In the same year, a third treatise by Kelsen was published: Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (The Problem of Sovereignty and the Theory of Public International Law), subtitled Beitrag zu einer reinen Rechtslehre (Contribution to a Pure Theory of Law).Footnote 34 In it, Kelsen deconstructs the concept of sovereignty preceding law. From the late 1920s onwards, Kelsen’s preoccupation with the theory of constitutional jurisdiction and its compatibility with a representative democracy is particularly important.Footnote 35

This already facilitates a connection to the second strand of development, namely, Kelsen’s contributions to legal theory, in which he deconstructs numerous underlying presuppositions, conceits, and theorems that conventional democratic theory had fallen back on (and still falls back on today). In this respect, one might associate the papers in which Kelsen shows, for example, that the will of the state (Staatswillen) or of the people (Volkswillen) must not be understood as a real-psychic entity;Footnote 36 Kelsen’s work on how to deal with fictions – with representation as a fictionFootnote 37 – also comes to mind. Alternately, as mentioned previously, Kelsen’s arguments on the concept of sovereignty are also pertinent, as he stresses sovereignty is not suitable as a basis for a theory of democracy.Footnote 38

Considering Kelsen’s theory of democracy, as presented in 1929 in Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, in the context of the rest of his scholarly work and output, it becomes clear that it is, to a certain extent, the mature fruit of many years of endeavours – an endeavour that is animated by considerations directly related to democracy but also by those that initially have no direct thematic nexus with democracy. At the same time, the interplay of the theoretical writings on democracy with those on legal theory provides an interpretative path to understand how the political theorist and the legal theorist are intertwined in the person himself.Footnote 39

3.5 Comparing the First and Second Editions of The Essence and Value of Democracy

In the international, mostly English-language discourse, it is easily overlooked that the 1929 version of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie is the greatly expanded second edition of an article that was published originally in 1920 in Volume 47 of the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, whose original animating force and editor was Max Weber (1864–1920). For that volume, Emil Lederer (1882–1939) had assumed editorship. This misperception can easily be explained by the markedly different linguistic dissemination of the first and second editions: While the second edition of 1929 has been translated sixteen times into a total of twelve languages, namely, in chronological order, into French (1932), Japanese (1932, 1966, 2015), Czech (1933), Spanish (1934, 2006), Polish (1937), Turkish (1938), Korean (1958, 1961), Italian (1955), Portuguese (1993), Hebrew (2005), Ukrainian (2013), and English (2013), the first edition of 1920 experienced just three translations, into Italian (1932), Japanese (1977), and Serbian (1999). In Kelsen’s lifetime, the first edition was translated only once, viz. into Italian; translations into English, French, and Spanish, that is, widely spread languages, are still missing. The situation is different for the second edition: By the time of Kelsen’s forced emigration to the United States in 1940, there had already been eight translations into six languages, including French, Japanese, and Spanish. A translation into English, however, took place only very late: after a partial translation appeared in 2000, the complete translation into English followed only a decade ago, that is, eighty-four years after the German edition and forty years after Kelsen’s death.Footnote 40

If we place the first and second editions, which appeared in German at intervals of just about nine years, side by side, the development of Kelsen’s thoughts in these very turbulent times for the Republic of Austria and the Weimar Republic, as well as for Kelsen himself, can be traced quite well. In terms of size, the two editions differ considerably: the first edition contains approximately 86,200 characters (including spaces; approximately 12,000 words); the second edition, with 218,900 characters (including spaces; approximately 30,000 words), is approximately two-and-a-half times as extensive – and thus more than a mere new edition within the conventional parameters of essentially minor alterations and amendments. In the outline, too, the original seven sections in 1920 become ten in the second edition, supplemented by a preface. However, despite these apparently remarkable changes, the similarities in content are so striking that it seems justified, even in retrospect, for Kelsen to have explicitly emphasised the 1929 version as the second edition of the contribution published in 1920. This is all the more so because Kelsen based the 1929 version on the text of the 1920 version, revised it stylistically, rearranged it in a few passages, omitted only a few aspects entirely, fleshed out and developed it in numerous sections, and supplemented it in other parts with entirely new content. Kelsen only revises his 1920 opinion in two rather subordinate aspects, but there are no substantial changes.

First, it is noteworthy that Kelsen more strongly emphasises the contrast between democracy as an ideal and democracy as a real form of government. The sociopolitical conditions of the realisation of a modern mass democracy are repeatedly emphasised and put up against democratic ideologies and ideals; democracy must show its essence and value through them. The most striking additions are the greatly expanded remarks on parliamentarism and related questions. Although he emphasises the fictional character of representation – thus seemingly depriving the concept of parliamentary democracy of important support – he considers parliamentarism to be ‘the only realistic from of government capable of putting the democratic ideal into practice under today’s social conditions’.Footnote 41 Both in the extraparliamentary and in the parliamentary sphere, he recognises an indispensable role for political parties – in opposition to the strong and enduring reservations against political parties as a whole that prevailed in a significant part of contemporaneous constitutional law theory and doctrine. In comparison with the first edition, compromise is accorded a significantly enhanced position as a system-stabilising element that establishes an equilibrium between political differences in a democracy based on the majority principle and the protection of minorities; it virtually becomes the foundational background. Kelsen responds to the growing criticism of parliamentarism in the 1920s – widespread discourse on a ‘crisis of parliamentarism’ – with two new chapters, namely, Die Reform des Parlamentarismus (Reforming Parliamentarism) and Die berufsständische Vertretung (Corporative Representation).Footnote 42 With greater clarity than in 1920 and with reference to a central work by his most important student, Adolf Julius Merkl,Footnote 43 Kelsen opposes the demand for comprehensive ‘democratisation’ of the administration – with the argument that the democratically formulated will of the legislature is more faithfully and reliably realised by an ‘autocratic’ ministerial hierarchy than by a ‘democratic’ decision by elected collegial bodies. In this context, Kelsen mentions both administrative jurisdiction and constitutional jurisdiction as modes for securing the legality embodied in democratic law (although without detailed elaboration). There is also an intensified discussion of the new (Austro-)Marxist ideas of the time; the Bolshevik approaches already dealt with in the first edition are newly juxtaposed with the concepts of Italian fascism – which was not yet known beyond Italy in 1920. In general, Kelsen now emphasises the ideological aspects more strongly and accordingly elaborates in more detail on what he had already stated in the first edition: ‘Der Relativismus ist daher die Weltanschauung, die der demokratische Gedanke voraussetzt’. (‘Relativism is therefore the ideology that democratic thought presupposes’.)Footnote 44

Among the few deletions Kelsen made in relation to the first edition are the critical references to the electoral provisions of the Constitution of the Russian Soviet Socialist Federative Republic of 10 July 1918.Footnote 45 Lenin’s (1870–1924) antiparliamentary remarks, which were prominent in the main text of the first edition,Footnote 46 are now shifted to a long endnote.Footnote 47 One would not be mistaken to understand this as the reflection of increasing distance of the Soviet Union, in parallel with the ascendancy of Stalin (1878–1953) within the Communist Party, from Western and Central Europe during the 1920s. It was precisely in connection with the Bolshevik developments in Russia that Kelsen referred five times to the contribution by Max Weber, whom he held in high esteem, to Parlament und Regierung im neu-geordneten Deutschland (Parliament and Government in Reorganised Germany) in the first edition.Footnote 48 This contribution is no longer mentioned in the second edition. Admittedly, this is unlikely to be because Kelsen would have seen Weber’s theses in a different light in 1929 than he did in 1920;Footnote 49 rather, the deletion could be explained by the fact that Weber’s writing stood out differently in the year of upheaval in 1918 than it did a good decade later. Max Weber is only referred to once in the second edition with the concept of autocephaly, a concept that Kelsen presents as familiar and unremarkable without further extended discussion or demonstration.Footnote 50

The extent to which the contexts diverged in 1920 and 1929 is also evident in Kelsen’s manner of dealing with literature: In 1920 – or more precisely, at the end of 1919, when the manuscript was completed – Kelsen could not yet draw on any contribution to democratic theory from constitutional doctrine. His main references – apart from the classics Plato, Cicero, Montesquieu, Kant and, again and again, Rousseau on the one hand and Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky on the other – are contemporary economists and social science scholars who had each published German-language monographs on modern democracy shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, such as the German Wilhelm Hasbach (1849–1920),Footnote 51 the Swede Gustav Frederik Steffen (1864–1929)Footnote 52 and the Ukrainian David Koigen (1879–1933).Footnote 53 Kelsen continues to refer to these three authors in the second edition. However, German-language literature from constitutional law and political science published in the years after the First World War is also included. This is undertaken in a peculiar way: With one exceptionFootnote 54 – to be specified immediately and easily explained – Kelsen does not mention the names of his antagonists in constitutional law. Nowhere in the text is there a reference to the names of Erich Kaufmann, Rudolf Smend, Carl Schmitt, or Hermann Heller. In contrast, he positions himself critically against their doctrines by referring to his own recently published writings in which he had explicitly dealt with the views of his opponents. In this regard, he refers in particular to his main work, the Allgemeine Staatslehre (General Theory of the State).Footnote 55 Of his critics, however, he only names Heinrich Triepel who had published a contribution, which, in conformity with the predominant orientation of constitutional law at the time, critically reflects on the role of political parties.Footnote 56 For his part, Kelsen treats Triepel’s position very critically in four detailed endnotes.Footnote 57 Kelsen conferred the honour of mentioning only Triepel by name in the treatise, probably because Triepel’s article was published in time for Kelsen to know it before he wrote his manuscript in mid 1928 but not in time for Kelsen to have been able to refer to it in an earlier contribution, such as his paper on democracy at the German Sociologists’ Conference.Footnote 58

The situation was different from the main works by Carl Schmitt – Verfassungslehre (Constitutional Theory) – and Rudolf Smend – Verfassung und Verfassungsrecht (On Constitution and Constitutional Law) – which were published in 1928:Footnote 59 Both books appeared too late for Kelsen to include them in the 1929 version of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie. A year after the publication of the second edition, Kelsen wrote a detailed and devastating substantive critique of Smend’s On Constitution and Constitutional Law.Footnote 60 At the end of the Weimar Republic, a literary controversy that was important for the entire Weimarer Richtungs- und Methodenstreit arose between Carl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen on the issue of who should be the guardian of the constitution and, in particular, whether a constitutional court could play this role. While Schmitt considered the idea of a genuine constitutional court that could declare laws null and void for violating the constitution to be a contradictio in adiecto,Footnote 61 Kelsen comprehensively defended this idea.Footnote 62 In the second edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, the question of the compatibility of parliamentary democracy and constitutional jurisdiction is already addressed but not yet as elaborately as in the following years.Footnote 63

Moreover, Kelsen cited his own works to a much greater extent in the second edition than in the first edition. Whereas in 1920 Kelsen drew on only two of his own writings in four of a total of fifty footnotes, in the second edition he referred to his own works eighteen times in a total of forty-five endnotes. This self-citation was undertaken with the consistent purpose of addressing current issues that he had already dealt with in earlier writings. The eleven contributions are as follows: Kelsen’s very first publication, a small monograph on Dante Alighieri,Footnote 64 Gott und Staat (God and State),Footnote 65 the second edition of his habilitation thesis (1923), the second edition of Sozialismus und Staat (Socialism and the State) (1923),Footnote 66 a review of a work by the Austro-Marxist Otto Bauer,Footnote 67 the Allgemeine Staatslehre,Footnote 68 Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (On the Problem of Parliamentarism),Footnote 69 his paper to the German Sociologists’ Conference,Footnote 70 the second edition of Der juristische und der soziologische Staatsbegriff (The Legal and the Sociological Concept of the State),Footnote 71 Die philosophischen Grundlagen der Naturrechtslehre und des Rechtspositivismus (The Philosophical Foundations of Natural Law Doctrine and Legal Positivism)Footnote 72 and the lecture on constitutional jurisdiction at the Institut international de droit public in Paris.Footnote 73 The majority of new arguments in the second edition that extend beyond the first are attested to by Kelsen’s own works. This method of self-reference corresponds to Kelsen’s approach to his work and thought, which can be described as a building-block approach and which we will discuss in more detail below.

To summarise the findings of the comparison of the first and second editions of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, both editions strongly reflect the respective spirit of their chronological position in the decade of the 1920s. In 1919/1920, the states of Central Europe that had converted to democratic republics had hardly any experience with a democracy – in Austria, the monarchy had been abolished for only one year, and the new definitive constitution of 1 October 1920 had not even come into force. The focus of the time was on the confrontation with Marxist, Bolshevik, and socialist ideology. At the end of the decade, 1928/1929, democracy as a form of government was exposed to completely different challenges and dangers after years of practical experiences. Liberal democracy had to be defended against rampant anti-parliamentarism, compromise had to be upheld as the mode of balance between majority and minority groups, political pluralism had to be strengthened against an essentially authoritarian emphasis upon a form of thought oriented to homogeneity, and constitutional legality had to be made plausible as a democratic instrument of checks and balances. Accordingly, the second edition occasionally has a mode of presentation that has a more detailed focus upon social and legal technicalities than the first edition, but this reflects a realist intention: to thematise more directly the political reality of democracy. However, despite all the differences between the two editions, their tenor and underlying orientation remain essentially the same. Thus, the second edition appears as a version of the first edition from 1920 that has matured through numerous, subsequent experiences and insights.

The comparison could be extended at this point: we could compare Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, which Kelsen wrote in one of his last years in Vienna, with his contribution Foundations of Democracy,Footnote 74 which appeared approximately a quarter of a century later in exile in the USA. This, however, would exceed the scope of this contribution. Nevertheless, this much can be said: The 1955 article differs from the 1929 paper in almost everything – in its style, in the topics taken up, and in its juxtapositions. The completely different contexts, expectations, conditions, and challenges immediately after the Second World War shape this Kelsenian text. In the USA, the justification of a social order based on freedom does not have to figure as prominently as in the young democracies after the First World War. Nor does the defence of parliamentarism or the discussion of electoral structures play a significant role here. The focus, as the title unmistakably expresses, is on the foundations – meaning the ideological foundations – of democracy. Whereas the 1929 version of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie had in an explicitly pronounced manner turned to the sociopolitical, that is, the practical conditions for the realisation of modern liberal democracies, the 1955 contribution represents a certain shift back to the 1920 version, given that fundamental ideological questions shape the style of the contribution and sociotechnological perspectives recede into the background.Footnote 75 The relationship of democracy to philosophy, religion and economics determines the structure, style, and content of the contribution.Footnote 76 In contrast to the 1929 text, Foundations of Democracy contains detailed discussions of then-current concepts by scholars as diverse as Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992), Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883–1950), Jacques Maritain (1882–1973), Emil Brunner (1889–1966), Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971), and Kelsen’s former student Eric Voegelin (1901–1985). Thus, the insights of this study are more significantly bound to the zeitgeist of the 1950s than to that of the 1929 classic. In addition, Kelsen does not deny his relativist, liberal credo, which is directed towards social balance; in other words, the author of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie remains recognisable in this text as well. But this is not only because Kelsen, remaining true to his style of work (see below), occasionally transposes passages from Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie verbatim into the text from 1955.

3.6 Kelsen’s Building Block Approach

Kelsen’s working method can be characterised as a building block approach congenial to his style of thinking, which was aimed at perfecting his own concepts. Kelsen developed his ideas further in new publications by taking over numerous formulations, sometimes even entire passages, by directly transposing them from earlier publications. Previous lines of thought were upheld in new publications and only formulated anew when they were additions or modifications of the preceding framework. The literal quotations were not labelled as such; rather, they were amalgamated with the additions to form a uniform and coherent new text. This method of production allowed him to publish a great amount very quickly. Moreover, it corresponded to Kelsen’s understanding of scientific discourse, which develops dynamically and dialectically and in which the recognisability and reactivity of positions are of particular importance. This building block approach can be paradigmatically demonstrated in the 1929 version of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie.

Although the second edition, as has been seen, is more than twice the length of the 1920 edition and contains numerous new topics and theses, it can only be qualified as partially and selectively original in the context of Kelsen’s oeuvre. The second edition can certainly claim originality in composition and arrangement. Threads of thought and formulations, however, are clearly in a different situation. Kelsen’s building block approach is exemplified in Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie. The text draws on five sources, which are listed in chronological order below:

First, there is the 1920 edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie.Footnote 77 The first edition not only serves as the basic structure of the second edition but is also reflected in specific literal formulations. Changes in structure and wording are found, as described in detail above, in those passages where Kelsen accounts for more recent developments and insights. Above all, Kelsen rewrites in the new edition the passages on proportional representation, parliamentarism, the Soviet constitution, the separation of powers, the selection of leaders, and the relationship between democracy and bureaucracy.

Second, Kelsen draws on passages from the first complete exposition of the Pure Theory of Law three times, namely, in relation to the metamorphosis of the concept of freedom, the majority principle, and the connection between the form of government and a Weltanschauung. This treatise sees him at the zenith of his Viennese work and reputation in Weimar constitutional law: the 1925 Allgemeine Staatslehre.Footnote 78

Third: Except for remarks on the majority principle, the relationship between parliamentarism and liberalism, and relativism as a Weltanschauung of democracy, that is, topics on which he can refer to other writings, Kelsen includes almost the entire text of Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (On the Problem of Parliamentarism) in the second edition.Footnote 79 With this short monograph, published in 1925, Kelsen responded to the then-current debate on the so-called crisis of parliamentarism, for which Carl Schmitt’s 1923 Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus (The Intellectual-historical Condition of Contemporary Parliamentarism) can be cited as a representative.Footnote 80

Fourth: The text of the lecture on democracy given at the German Sociologists’ Congress in 1926 and published in 1927 is also largely included in the second edition.Footnote 81 Only Kelsen’s general remarks at the beginning on the dualism of ideology and reality, which Kelsen held to be especially challenging for sociology, were omitted in 1929.

Fifth and finally, Kelsen’s supplements, newly formulated especially for the second edition, are the connecting links between the other textual transpositions. However, they account for hardly more than 10 per cent of the total volume.

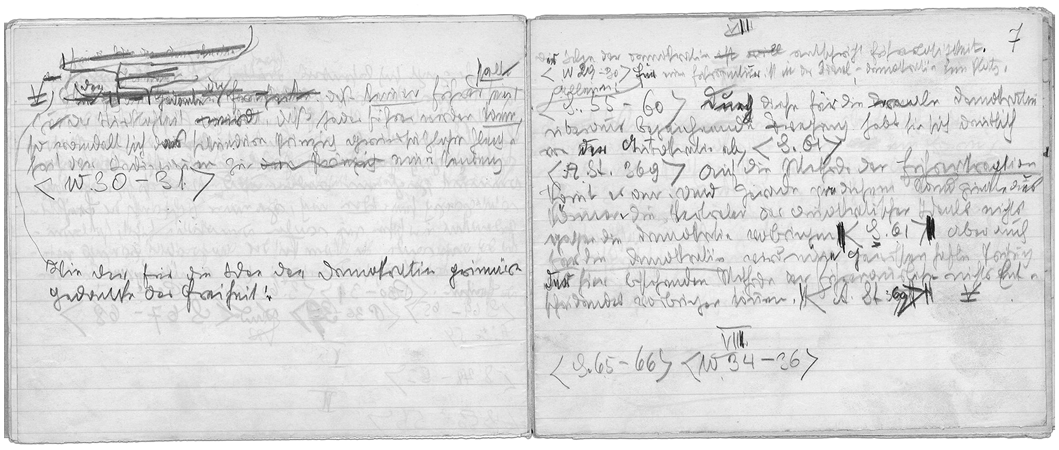

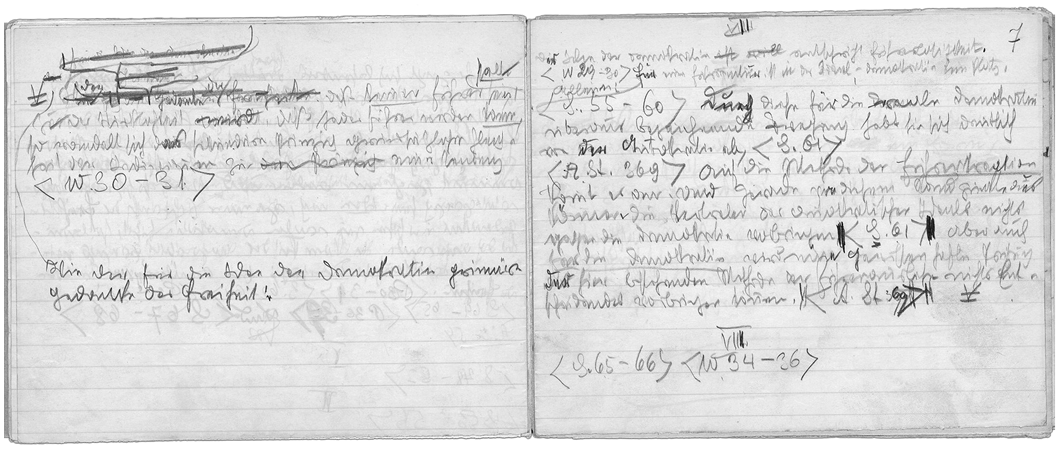

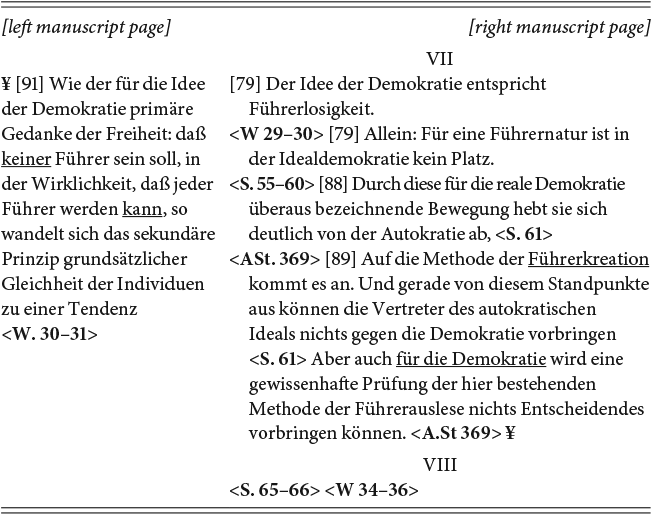

Kelsen’s working methods can be clearly studied in the original manuscript of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, one of the very few manuscripts by Kelsen that have been preserved from the time before his move to the USA in 1940. The manuscript pages reproduced here contain the text of VIII. Die Führerauslese (Eight. The Selection of Leaders)Footnote 82 and IX. Formale und soziale Demokratie (Nine. Formal versus Social Democracy) and Social Democracy.Footnote 83 The running text is on the right hand manuscript page; Kelsen used the left hand manuscript page for insertions. The abbreviation W stands for the first edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie,Footnote 84 the abbreviation ASt for the Allgemeine StaatslehreFootnote 85 and the abbreviation S for the paper on democracy at the German Sociologists’ Congress;Footnote 86 with P Kelsen abbreviated Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (On the Problem of Parliamentarism),Footnote 87 which is not referred to on the manuscript page reproduced below (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 A double-page spread from the autograph of Hans Kelsen’s Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, second edition, 1929.

Figure 3.1Long description

Image shows double-page spread from handwritten manuscript with dense German text written in pencil. Left page contains multiple crossed-out lines, underlines, and short marginal marks, with remaining text written across lined paper. Right page presents more crowded writing, including inserted words, corrections, arrows, and vertical strokes indicating revisions. Both pages show uneven handwriting, layered edits, and page markers at bottom center denoting manuscript structure.

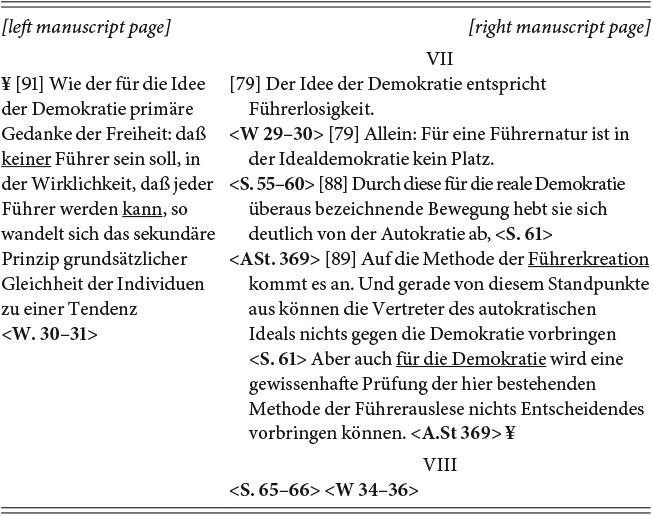

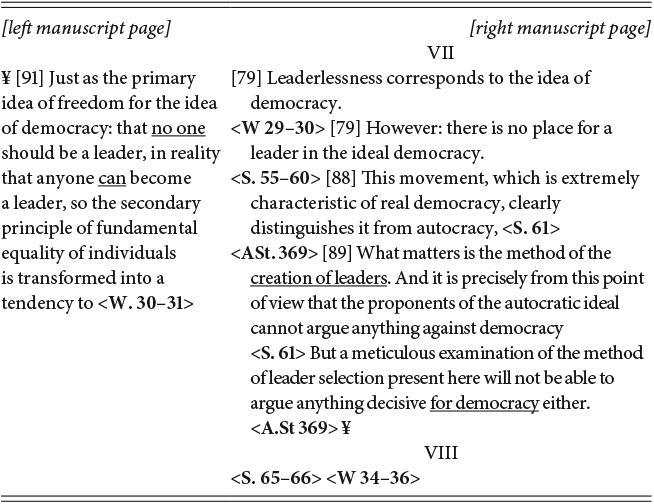

In the transcription, the text in the German original reads as follows (the pages of the original print are added in square brackets, crossed-out text is not reproduced):

Figure 3.101Long description

Table displays two-column comparison of manuscript pages. Left column titled “left manuscript page” lists note number 91, German sentences about Idee der Demokratie, Führer, and Gleichheit, with multiple page and marker references. Right column titled “right manuscript page” begins with Roman numeral VII, followed by numbered German text passages discussing Demokratie, Führerrolle, Führerkreation, Prüfung bestehender Methode, and additional page markers. Table ends with Roman numeral VIII at bottom right.

In the English translation, this reads as follows:

Figure 3.102Long description

Image shows double-page spread from handwritten manuscript with dense German text written in pencil. Left page contains multiple crossed-out lines, underlines, and short marginal marks, with remaining text written across lined paper. Right page presents more crowded writing, including inserted words, corrections, arrows, and vertical strokes indicating revisions. Both pages show uneven handwriting, layered edits, and page markers at bottom center denoting manuscript structure.

Kelsen is able to cover twenty pages of the printed version on a single (double) page of the manuscript. He achieves this by proceeding as follows: separated by newly formulated interlinear sentences, he strings together passages (marked by pointed brackets) from earlier writings. For the chapter Die Führerauslese (The Selection of Leaders) (in print, VIII, in the manuscript, VII), these passages first appeared in the 1920 edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (pp. 29–30). They are followed by excerpts from the paper on democracy at the German Sociologists’ Congress (pp. 55–60 and 61), extracts from Allgemeine Staatslehre (p. 369) with an insertion once again from the paper on democracy at the German Sociology Conference (p. 61) and finally another passage from the first edition (pp. 30–31). For the remarks on Formale und soziale Demokratie (Formal versus Social Democracy) (in print, IX, in the manuscript, VIII), Kelsen refers to larger blocks of text from the first edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (pp. 65–66) as well as from the conference paper on democracy (pp. 34–36).

Kelsen’s building block approach correlates with the way he documents his remarks in the endnotes. Except for six detailed endnotes in which he deals in particular with opposing views,Footnote 88 the endnotes are kept quite brief. They contain, in no small part (to be precise, in eighteen of forty-five cases) references to his own earlier works, whereby the Allgemeine Staatslehre stands out with seven mentions.Footnote 89 Kelsen uses the reference to his own works, as already mentioned above, to indicate that the relevant question and the position formulated in relation to it had already been subjected to consideration. Accordingly, he refrains from replicating these references again to alleviate the annotation apparatus. Although the Weimarer Richtungs- und Methodenstreit is already underway, one therefore searches in vain for the explicit designation of Kelsen’s main opponents (except for Triepel).

3.7 Conclusion

The second edition of Hans Kelsen’s The Essence and Value of Democracy (Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie), which has been translated into a dozen languages, is certainly his best-known and most important text on the theory of democracy. This text is probably the most canonical formulation of his theory of democracy; it is certainly the most consistent version, and it can rightly be said to be of continued relevance in contemporary debates on democracy. However, it was neither born of a moment of genius nor is it a philosopher’s precise declination of a central theorem. Rather, it is the result of an iterative and deliberative process spanning a decade that was fundamentally shaped by Kelsen’s experiences with democracy as a form of government both in Austria and in Weimar Germany.