The second part of this book focusses on Pater’s engagement with a number of major English writers. Appreciations covers all post-medieval centuries, excluding only the ‘Augustan’ period about which Pater was rather less than enthusiastic (though he did design, and perhaps complete, an essay on Dr Johnson). Pater is not normally thought of as a leading Shakespearean, but unsurprisingly Shakespeare was central to his idea of English literature, and at one point he may possibly have planned a whole volume on him; he was also at least sympathetic to the idea of undertaking a commentary for schoolboy use on Romeo and Juliet, whose ‘flawless execution’ he commended (‘Measure for Measure’, App., 170). Typically he did not write about the most celebrated plays (his own favourites also included Hamlet), but instead chose for treatment ones less popular in his day: Love’s Labour’s Lost (perhaps because of its reflections on language and style), Measure for Measure (arguably the finest of his three essays, centrally concerned with the way a work of art can profitably engage with ethics), and Richard II (the main focus of ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’, where Pater contributed to the idea of Richard as the ‘poet-king’ and added to the understanding of the deposition scene). Alex Wong examines all three essays in detail, and comments on the overall value and distinctive character of Pater’s view of Shakespeare.

Pater was part of a critical movement that gradually brought back into favour seventeenth-century writers of prose, neglected in the previous century. Kathryn Murphy explores Pater’s use of the word ‘quaint’ in ‘Sir Thomas Browne’ to examine the qualities in Browne’s prose that attracted him, despite any reservations he might have felt about a mode of writing that often fell short of classical precision. Through a careful reception history she shows that Pater develops the earlier positive estimates by Coleridge and Lamb, and anticipates the revaluation of the ‘metaphysical’ writers (so dubbed by Dr Johnson in critical vein) in the Modernist generation.

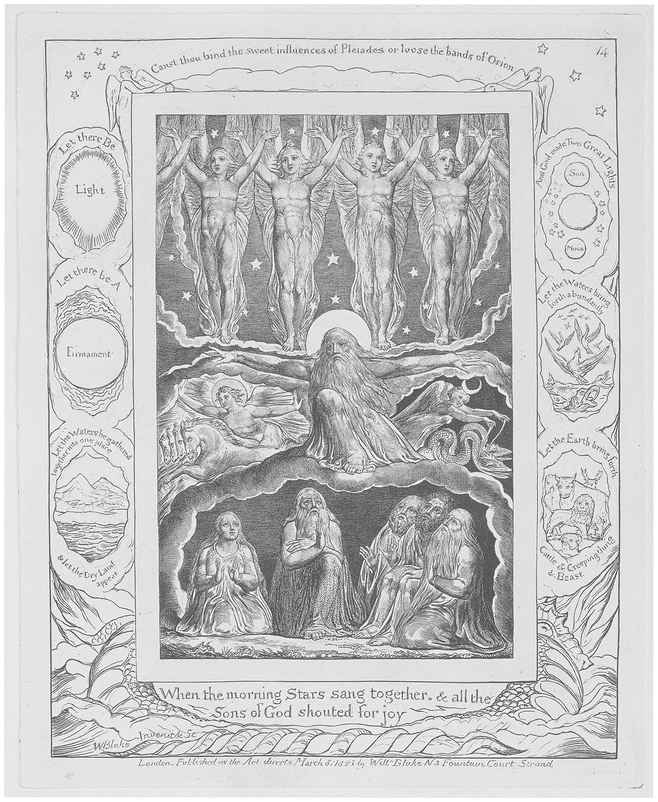

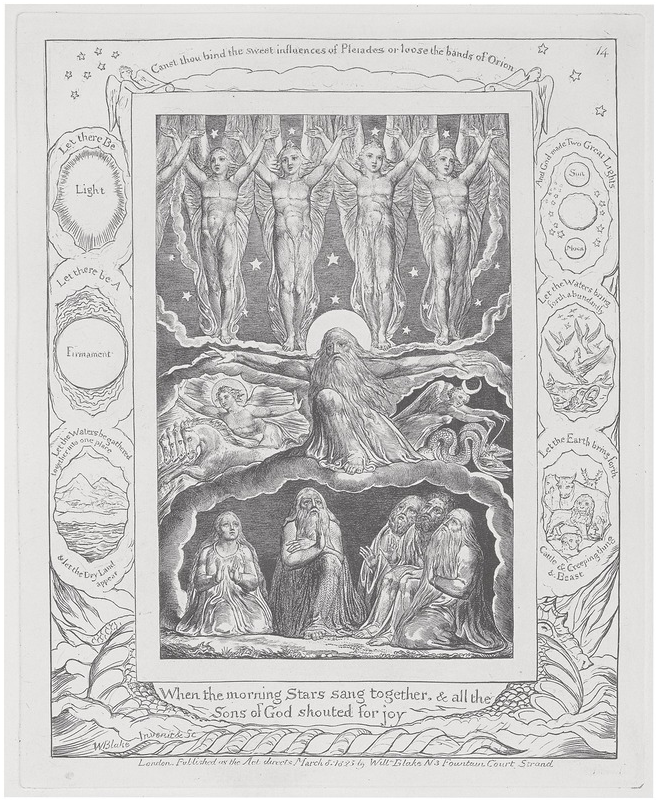

Pater was committed to stressing the importance across time of the ‘romantic’ tradition in English literary history, and included in Appreciations three essays on writers of the generation now generally described as Romantic. While Blake never became the subject of an essay, Pater refers to Blake on what is, for him, a quite unusual number of occasions, from the essay on Michelangelo (1871) onwards. This is doubtless partly because Blake is both a poet and a painter, and thus relevant to the issue of the relationship between the various arts discussed in ‘The School of Giorgione’, partly because Blake is a figure in some ways ‘out of his time’ or particularly relevant to other times (something that always fascinated Pater). Luisa Calè suggests that Pater’s interest may have been triggered by exhibitions in 1871 and 1876, at which he encountered Blake’s paintings The Spiritual Form of Pitt, of Nelson, and of Napoleon. It also seems likely that Pater’s interest throughout was fuelled by his still greater interest in the art and poetry of Rossetti, and in Pre-Raphaelitism and Aestheticism generally. Blake’s illustrations to Job were highly admired in these circles, especially ‘When the Morning Stars Sang Together’, mentioned by Pater more than once. Blake can readily be seen as a forerunner of Romanticism and of the Pre-Raphaelites, for example in his hostile annotations to Reynolds’s art theories, from which Pater quotes. Next Charles Mahoney demonstrates the ways in which Pater’s accounts of two of the great Romantic poets, Coleridge and Wordsworth, established new terms for their consideration (in Coleridge’s case in the context of his relative neglect; in Wordsworth’s, as an alternative to an already established pattern of reading his poetry), that in a number of important respects helped to evolve approaches that are still operative in our appraisal of their works. Of course Pater, like his contemporaries, did not use the designation ‘English Romantic poets’ in the current manner – for him Wordsworth and Coleridge were part of the ‘Lake School’ – but the word ‘romantic’ is used throughout the essay on Coleridge to characterise both the man and his work. In the last chapter on this group of writers Stacey McDowell explores Pater’s view that the writings of Lamb illustrate ‘the value of reserve’ in literature and examines what Pater meant by the term. Within the context of the Tractarian doctrine of reserve, Keble and Newman identify its poetic expression with verbal indeterminacy, indirectness, metaphor, and irony. By flaunting such qualities, Lamb’s openness becomes a form of deflection, his lightness valued in itself and for what it modestly conceals.

Finally, we come to the Victorians. Lewis R. Farnell, who was inspired by Pater’s lectures on Greek sculpture to become an archaeologist, records a dinner-party conversation in Oxford:

One of our best conversationalists was Walter Pater, who gave charming dinner-parties, where his talk had the delicate aroma of his writings, but with more ease and simplicity. … we were talking of the comparative merits of contemporary poets, Tennyson, Browning, Swinburne, Matthew Arnold and William Morris, each of whom had his champion, when Pater summed up with a gentle but emphatic decision that each of the others excelled Tennyson in some particular quality, but that generally and all round Tennyson excelled them all and would outlive them.

Characteristically Pater did not write about the acknowledged favourite (though he did review Arthur Symons’s book on the more controversial Browning). Instead, consonant with his especial interest in Pre-Raphaelitism and Aestheticism, he published essays on Morris and Rossetti (the latter not included in Farnell’s list, presumably because already dead). Marcus Waithe takes Pater’s engagement with Morris as a basis for thinking about his contribution to the development of English studies, exploring his evaluative criteria and methodology; what Pater values in Morris also envisions what he values in literature more generally. As a poet-painter, like Michelangelo and Blake, Rossetti was always a special point of reference for Pater; William Sharp recalls Pater describing him in 1880 as ‘the greatest man we have among us, in point of influence upon poetry, and perhaps painting’ (‘Reminiscences of Pater’, 1894, in Walter Pater: A Life Remembered, ed. R. M. Seiler, 81). Elizabeth Prettejohn argues not only that Pater’s densely intertextual essay plays a more important role in Pater’s overall critical project than previous scholars have recognised, but also that Pater’s treatment had a distinctive impact on the next generation of Modernist critics. Indeed, Pater’s essay may be most important for explaining to us a historical fact that may seem difficult to understand: the extraordinary influence of Rossetti on both painters and poets of his own and succeeding generations, an influence out of all proportion, some may think, to his actual achievement in either art form.

Besides the many scattered references that appear throughout his writing, Pater’s Shakespearean criticism is contained in three published essays, all finally included in Appreciations. At one time, however, they may have been intended for parts in a larger whole.

‘A Fragment on Measure for Measure’ was the earliest, printed in the Fortnightly Review in November 1874. Pater may have intimated that it was to be the first of several such pieces: that very month, the ‘Notes and News’ section of the Academy reported that he meant ‘to continue his short aesthetic studies of Shakspere’s plays’, building up a ‘series that will some day make a book’. A note in December added: ‘we understand that Mr Pater’s next Shakespeare “study” for the Fortnightly Review will be on Love’s Labour’s Lost’.1 But the essay ‘On Love’s Labours Lost’ did not appear in print until December 1885, almost exactly eleven years later, and not, as promised, in the Fortnightly, but in Macmillan’s Magazine.

A brief letter survives from Pater to the scholar F.J. Furnivall (1825–1910), founder in 1873 of the ‘New Shakspere Society’. It is dated only ‘May 18’. ‘I should like much to edit a play of Shakspere, e.g. Romeo and Juliet, for schoolboys,’ Pater writes, ostensibly replying to an invitation from his correspondent, ‘but see no prospect of my having time to do so for a long while to come, so must deny myself the pleasure of saying and fancying that I will do so.’2 He also remarks that he has ‘not yet had time to read over again [his] notes on L.L.L.’. Lawrence Evans plausibly dates the letter to 1875, supposing that Furnivall had been prompted to write to Pater by the Measure essay and the notes in the Academy. If this is correct, then Furnivall was kept waiting three years for the piece on Love’s Labour’s Lost: Society records indicate that a paper of Pater’s on that play, probably an early version of the essay, was read (we do not know by whom) at a meeting on 13 April 1878. Six months later, apparently willing to give up the idea of a whole book on Shakespeare, we find Pater listing both of the then completed essays in a list of proposed contents for a book, pitched to Macmillan, to be called The School of Giorgione, and Other Studies.3 That book never came into being, but neither was any notion of a Shakespeare volume ever practically revived. Pater sat on his study of Love’s Labour’s Lost for seven more years before seeing it into print, and the third of his Shakespeare essays, ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’, did not appear until April 1889 in Scribner’s Magazine, not long before its inclusion in Appreciations in the following November.4

The three plays to which Pater substantially attended were relatively unpopular in his own day, and rarely if ever performed. Richard II, the main focus of ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’, he had seen as a schoolboy, after which it was not performed again in commercial English theatres until after Pater’s death. Measure he could never have seen professionally performed before writing about it, though a production was mounted at the Haymarket Theatre in April 1876, the sole London production in Pater’s adult life. Having missed it, presumably, at Sadler’s Wells in 1857, he could not have seen Love’s Labour’s Lost acted either.5 As Adrian Poole notes, Pater ‘fastened on plays that had been caviar to the general’.6 Not only to the ‘general’, theatre-going public, however, but also to most critics of his own day and of preceding decades. Measure had been branded ‘painful’ by Coleridge, and Swinburne speaks of ‘the relative disfavour’ in which the play had ‘doubtless been at all times generally held’.7 Richard II, though the Romantic critics brought some new appreciation, had been relatively neglected since the early seventeenth century, save for some periods in which current affairs reactivated its political valency. Love’s Labour’s Lost, meanwhile, had more consistently been regarded as Shakespeare’s first and worst play. Pater’s appreciations were supplied where they were needed.

Measure for Measure

Of the three essays, the study of Measure for Measure has had the least effect on later Shakespearean criticism. It is, however, the most obviously revealing of Pater’s own values. His reading of the play is unusual, turning the familiar moral complaints of most other nineteenth-century critics virtually inside out. Coleridge’s famous objections to Measure, for example, with which many have concurred, are squarely moral. He finds the comedic aspects of the play ‘disgusting’ and the tragic aspects ‘horrible’, but really it is the play’s ending that makes it so obnoxious to him, for ‘the pardon and marriage of Angelo not merely baffles the strong indignant claim of justice’ but is furthermore ‘degrading to the character of woman’.8 Swinburne, writing a little later than Pater’s essay, pays more attention to the aesthetic character of the play, but considers its merits essentially tragic, and so returns to an ethical criterion: the ‘evasion of a tragic end’ is ‘ingenious’ in its management, but unworthy of Shakespeare ‘in a moral sense’.9 Yet for Pater, Measure for Measure is ‘an epitome of Shakespeare’s moral judgments’:

The action of the play, like the action of life itself for the keener observer, develops in us the conception of this poetical justice, and the yearning to realise it, the true justice of which Angelo knows nothing, because it lies for the most part beyond the limits of any acknowledged law. The idea of justice involves the idea of rights. But at bottom rights are equivalent to that which really is, to facts; and the recognition of his rights therefore, the justice he requires of our hands, or our thoughts, is the recognition of that which the person, in his inmost nature, really is; and as sympathy alone can discover that which really is in matters of feeling and thought, true justice is in its essence a finer knowledge through love. … It is for this finer justice, a justice based on a more delicate appreciation of the true conditions of men and things, a true respect of persons in our estimate of actions, that the people in Measure for Measure cry out as they pass before us …

Poetical justice is ‘true justice’, truer than the law’s inflexible approximations. It has for its objects the facts of human lives and selves, ‘that which really is’ – the facts that must be found out through sympathy; a knowledge that comes from love, which, to those who can apprehend it, confers ‘rights’ which are ethically imperative. It has to do with a ‘finer’ estimate of reality – ‘life itself’ – and not only reality as simulated by a work of poetic creation.

But the ethical appeal of a play like Measure is reliant on its being, to sensitive minds, ‘like the action of life itself’ – more like reality than a simpler or more reductively moralistic play might be. And, as Pater will confirm with his passionate final sentence, it may be that the moral exercise of attending keenly to such works of literature can make us keener observers in the real world too, perhaps not only through the simulation of moral situations, but through the discriminating activities of mind always required and rewarded by poetry, in which intellectual understanding of subtle language is connected naturally to feelings and values:

It is not always that poetry can be the exponent of morality; but it is this aspect of morals which it represents most naturally, for this true justice is dependent on just those finer appreciations which poetry cultivates in us the power of making, those peculiar valuations of action and its effect which poetry actually requires.

‘Actually’, the penultimate word in the essay, has the effect here of dissolving the boundary between reading and reality. Poetry and the actual world may not be identical, but poetry is part of our actual lives and ‘actually’, really, makes demands upon us, which in turn may modify our habits of mind and conduct. The ‘finer appreciations’ which the reader or critic of poetry is called upon to make are offered as the basis for true justice beyond the limits of literature. It is fitting that the essay finally found a place in a volume called Appreciations. The kind of criticism Pater writes is ‘appreciative’, and, while the word implies evaluation, and could in one sense be glossed as the setting of prices on things, Pater is particularly in the habit of raising, not lowering, the accepted price. Taking another etymological route, we might think of his appreciations as contributions towards the ‘prizing’ of things of value, often things undervalued or ignored by others but for which he feels a special affinity or sympathy. In this sense it is a process of ‘finer knowledge through love’.

This theme of taking care over what others neglect is obliquely suggested in Pater’s striking choice of illustrative quotation:

Earlier, Pater has said that ‘it is Isabella with her grand imaginative diction … who gives utterance to the equity, the finer judgments of the piece on men and things’; she is one of the women in Shakespeare whose ‘intuitions interpret that which is often too hard or fine for manlier reason’ (179; emphasis added). But these lines on the jewel, the ones he actually quotes, are spoken not by the virtuous Isabella, nor by the philosophical Duke, but by Angelo, the play’s chief villain. Inclining to be rigid in exercising legal justice in the case of Claudio (held guilty of pre-nuptial fornication), he has just been advised by Escalus to consider whether he himself, Angelo –

– might not by some imaginable chance have ‘erred’ in a like manner. What Escalus puts to Angelo is an ethical urging of the very point Pater stresses in various parts of the essay: his conviction that Shakespeare ‘inspires in us the sense of a strong tyranny of nature and circumstance’, the tyranny of chance ‘over human action’ (174, 180). In fact, those lines from Escalus, which he does not otherwise quote, Pater echoes closely in his own elaboration of the point, taking the character of Angelo as his example:

The bloodless, impassible temperament does but wait for its opportunity, for the almost accidental coherence of time with place, and place with wishing, to annul its long and patient discipline, and become in a moment the very opposite of that which under ordinary conditions it seemed to be, even to itself.

The unusual use of ‘coherence’ helps to mark the echo. But Angelo’s own airing of the jewel metaphor, which Pater does quote – though without reminding us of the context or the speaker – is all the more powerful in Pater’s hands for being an ironic reflection on that very ‘tyranny’ of chance. Angelo replies to Escalus by emphasising the difference between temptation and the actual commission of ‘error’: no simple distinction in cases such as his own will turn out to be, though he little suspects it at this moment. He acknowledges that the jurors may well be guiltier than Claudio, but sees this as no impediment. ‘What’s open made to justice, / That justice seizes’ (II.1.21–22). The lines about the jewel, almost immediately following this, are meant to convince Escalus that it’s no use worrying about the jewels, or the crimes, you can’t see: what is obvious is what one has to deal with, even if it becomes obvious only by chance. When Pater repurposes the lines, they become – with an ironic edge for those who recall the context – a moving exhortation, without exhorting, to look for the unnoticed jewels trodden underfoot: to ‘see’ more, and so ‘tread’ more carefully. Angelo subverts the essential, commonplace meaning of the lines, by making jewels stand for crimes; but in restoring Angelo’s chosen maxim (for it is produced as a piece of conventional wisdom) to something closer to its basic sense, Pater has allowed it to retain the dramatic irony it has accrued through Angelo’s use of it, and through its applicability to his later actions and experience in the plot. The sentiment is given a renewed humaneness, not only by its having been sullied by Angelo first, but by the breadth of moral meaning which Pater’s whole interpretation of the play gives to it.

In its ‘finer’ details, that interpretation is Pater’s; but it has one important forerunner and inspiration in Hazlitt’s book, The Characters of Shakespear’s Plays (1817). In the first place, several critics and surely many readers have been struck by the prominence given by Pater to the character of Claudio, and his claim that ‘the main interest in Measure for Measure is not … in the relation of Isabella and Angelo, but rather in the relation of Claudio and Isabella’ (177). But this is where Hazlitt also fixed his focus, calling the scene in which Isabella visits her condemned brother in his cell ‘one of the most dramatic passages’ in the play, and then quoting from it extensively.10 It is on just that exchange between brother and sister that Pater focuses his own attention. As with Angelo, he is exercised by the way in which, under the stress of unexpected circumstance, each character’s nature is revealed in a new way. Isabella, a ‘cold, chastened personality’, is exposed in the drama to ‘two sharp, shameful trials’ which ‘wring out of her a fiery, revealing eloquence’ (177–8) – and this is the second of those trials. She becomes ‘the ground of strong, contending passions’, undergoing a ‘tigerlike changefulness of feeling’; her angry indignation at Claudio’s apparent willingness to sacrifice her honour (perhaps her soul) in order to live, leaves her ‘stripped in a moment of all convention’, revealing her in a new light, or atmosphere – ‘clear, detached, columnar’ (178). But, as in Hazlitt, it is the offending eloquence wrung out of Claudio in the same scene that strikes Pater most forcefully.

Called upon suddenly to encounter his fate, looking with keen and resolute profile straight before him, he gives utterance to some of the central truths of human feeling, the sincere, concentrated expression of the recoiling flesh. Thoughts as profound and poetical as Hamlet’s arise in him; and but for the accidental arrest of sentence he would descend into the dust, a mere gilded, idle flower of youth indeed, but with what are perhaps the most eloquent of all Shakespeare’s words upon his lips.

Adrian Poole has paid tribute to Pater’s ‘deep feeling’, in this essay, ‘for the force of words that can take us by surprise, for better or worse, revealing capacities in us we did not know we had and the absence of others we supposed that we did’.11

But Pater’s closeness to Hazlitt goes further than this. Like Pater, Hazlitt too rises from specific criticisms of Measure to broader comments on the moral significance of Shakespeare’s work. ‘In one sense,’ Hazlitt says, ‘Shakespear was no moralist at all: in another, he was the greatest of all moralists.’ That what he provides to us is ‘like the action of life itself for the keener observer’, and thus able, as Pater thought, to develop in us a ‘finer’ sense of justice, is implied by Hazlitt’s comment that Shakespeare was ‘a moralist in the same sense in which nature is one’. Unlike the ‘pedantic moralist’, he does not seek out ‘the bad in every thing’, but the opposite: his talent, according to Hazlitt, ‘consisted in sympathy with human nature, in all its shapes, degrees, depressions, and elevations’.12 Pater’s emphasis on ‘sympathy’ seems clearly indebted to Hazlitt’s memorable chapter on the same play, though it is also highly characteristic of himself. Inman makes a telling comparison when she notes that the argument here about Shakespeare recalls Pater’s earlier essay on Botticelli: ‘His morality is all sympathy’ (Ren., 43).13

Strangely enough, before arriving at his formulation of Shakespearean ‘sympathy’, Hazlitt has already, in the same brief chapter, made the seemingly contradictory point that in this particular play there is ‘a general system of cross-purposes between the feelings of the different characters and the sympathy of the reader or the audience’. ‘Our sympathies’, he says, ‘are repulsed and defeated in all directions.’14 How, then, does a consideration of this play, which he seems to find defective in the very quality for which he lauds Shakespeare as a moralist in general, lead Hazlitt shortly into those grand statements about Shakespeare’s sympathetic morality? In fact, he arrives there by way of a discussion of the minor ‘low’ characters – Barnardine, Lucio, Pompey, Master Froth, Abhorson. He thinks Schlegel too ‘severe’ on such characters in calling them ‘wretches’; Shakespeare himself does not look at them with such contempt.15 Pater will be still more apologetic, and he sympathises with them all the more because they do so with one another:

The slightest of them is at least not ill-natured: the meanest of them can put forth a plea for existence—Truly, sir, I am a poor fellow that would live!— … they are capable of many friendships and of a true dignity in danger, giving each other a sympathetic, if transitory, regret—one sorry that another ‘should be foolishly lost at a game of tick-tack.’

For him too the ‘low’ characters are important to a moral reading of the play, but he brings them into closer proximity to at least some of the major characters (and their weaknesses), and so for him the Shakespearean sympathy is not limited to the peripheries of the drama but extended to its whole purview. They belong to the ‘group of persons’ powerfully portrayed by Pater as ‘attractive, full of desire, vessels of the genial, seed-bearing powers of nature, a gaudy existence flowering out over the old court and city of Vienna, a spectacle of the fulness and pride of life which to some may seem to touch the verge of wantonness’ (173–4). Pater is ‘pleasantly unshocked’, says Poole, suggestively, ‘by the seedier aspects’ of the play.16 Seedy or, as Pater has it, seed-bearing. He places himself on the side of ‘life’. It is Claudio’s horror of death that seems to move him most. The ‘low-life’ characters are united with Claudio in their vitality – not only their ‘vivid reality’ (174), but their earthiness and alliance with what is generative and vibrant in human experience, even unto the ‘verge of wantonness’. They are among ‘the children of this world’, though not among ‘the wisest’.17

As Mark Hollingsworth simply puts it, ‘Pater has found a moral in Shakespeare’s play—but it is not a moral of which certain of his contemporaries would approve’.18 Largely avoiding the main ethical cruces of the plot – totally neglecting, above all, to make any explicit comment on its ending – Pater’s reading relies on an appreciation of Shakespeare’s treatment of the material as being true to life in its multiplicity: not only in the moral implications of the action itself, but through the presentation of characters, the sentiments put into their mouths, the seeming gratuitousness of small details. Though, via its source in Whetstone, the play inherits some evolved qualities of the older morality plays, it achieves its moral significance by implicitly denying the validity of that tradition’s didactic clarity:

The old ‘moralities’ exemplified most often some rough-and-ready lesson. Here the very intricacy and subtlety of the moral world itself, the difficulty of seizing the true relations of so complex a material, the difficulty of just judgment, of judgment that shall not be unjust, are the lessons conveyed.

In the words of Philip Davis, the Victorian period was ‘full of commentators anxiously concerned about the work of Shakespeare being no more than (as it were) the world all over again, lacking an extrapolatable morality or an external philosophy that could give extra meaning to the universe’.19 These are the commentators who might have been less willing to ‘approve’, as Hollingsworth says, of Pater’s interpretation. Arnold is one of the chief critics of the period who are troubled by Shakespeare’s putative lack of interest in committing to a distinct governing conception to which details are subservient, and the antagonism between his and Pater’s approaches to Shakespeare has been helpfully emphasised by Poole.20 But Pater was far from alone in adhering to a rather different tradition, reaching back into the prehistory of Romanticism: the vision of Shakespeare as specially endowed to recreate reality itself. He was ‘Nature’s darling’, as Gray had famously called him, to whom ‘the mighty Mother did unveil / Her awful face’, conferring upon him the pencil to ‘paint’, like her, the natural world, and the ‘golden keys’ to open human experience: joy, horror, fears – and ‘sympathetic tears’.21 Hazlitt is invoking the same notion in his notes on Measure when he calls Shakespeare ‘a moralist in the same sense in which nature is one’, adding, in a movement not unlike Gray’s: ‘He taught what he had learnt from her. He shewed the greatest knowledge of humanity with the greatest fellow-feeling for it.’22 From this to ‘finer knowledge through love’ is a small but Paterian step.

For Pater, Shakespeare’s moral intelligence is that of an ‘observer’, a ‘spectator’, who ‘knows how the threads in the design before him hold together under the surface’, in hidden complexities or complications. He is also a ‘humourist’, ‘who follows with a half-amused but always pitiful sympathy, the various ways of human disposition, and sees less distance than ordinary men between what are called respectively great and little things’ (184). These terms, taken from the final paragraph of the essay, are very similar to those in which he will later describe and celebrate Montaigne, and indeed the connection between the two writers is explicitly made: ‘Shakespeare, who represents the free spirit of the Renaissance moulding the drama, hints, by his well-known preoccupation with Montaigne’s writings, that just there was the philosophic counterpart to the fulness and impartiality of his own artistic reception of the experience of life’ (Gast., 83, ch. 4; CW, iv. 80). Again what is stressed is a fullness of receptivity to reality as experienced. Thinking of Montaigne brings Pater close, again and again, to his thoughts on Measure. When he speaks of Montaigne’s apprehension of ‘the variableness, the complexity, the miraculous surprises of man, concurrent with the variety, the complexity, the surprises of nature, making all true knowledge of either wholly relative and provisional’, we are reminded of the interplay of nature and circumstance, the tyranny of their chance ‘coherence’, that he sees in Shakespeare: ‘coherent’, borrowed from Escalus, becomes ‘concurrent’ (89; CW, iv. 83). A few pages later, another version of the same thought, and two more Latinate words in substitution: here we have the ‘collision or coincidence, of the mechanic succession of things with men’s volition’ (Gast., 101, ch. 5: CW, iv. 90). Montaigne, like Shakespeare, has ‘many curious moral variations’ to show us, unsettling easy judgements on human conduct (94; CW, iv. 86).

But for the reader of Appreciations, the closing paragraphs on Measure are most likely to recall Pater’s study of Charles Lamb, placed earlier in the same volume. Shakespeare’s ‘half-amused but always pitiful sympathy’ (‘Measure’, App., 184) is that of the ‘humourist’, a type exemplified in Pater’s work most obviously by Lamb. In both writers, the ‘laughter which blends with tears’, humour as distinguished from wit, proceeds from a ‘deeply stirred soul of sympathy’ (‘Charles Lamb’, App., 105). The latter phrase is applied to Shakespeare, but ‘a sort of boundless sympathy’ belongs also to Lamb (110). He too attends closely to life’s ‘organic wholeness, as extending even to the least things in it’ (116). He ‘can write of death, almost like Shakespeare’ (120). And perhaps Pater is thinking in part of Elia’s love for life and ‘recoil’, like that of Claudio, from death. Both are genial natures who find they must, in Elia’s phrase, ‘reluct at the inevitable course of destiny’.23

Love’s Labours Lost

The humour of Lamb finds interest and significance, not mere trivialising or scoffing mirth, in ‘fashions’, ‘tricks’, and ‘habits’, the trappings and ephemera of a time and place – including one’s own, which the humourist can see with an uncommon ‘understanding’, amounting to a ‘refined, purged sort of vision’. The humourist sees any instance of such ‘outward mode or fashion, always in strict connexion with the spiritual condition which determined it’ (‘Lamb’, App., 114–15). It is in similar terms, and from the same perspective, that Pater was able in his study of Love’s Labours Lost [sic] to make an important defence of one of Shakespeare’s least popular works. ‘Shakespeare brings a serious effect’, he says, ‘out of the trifling of his characters’ (App., 161–2). Reminding us of the theoretical distinction with which he had opened his essay on Lamb, Pater tells us that the play contains ‘choice illustrations of both wit and humour’ (161); but the implication of the essay as a whole, especially in the light of the essays on Lamb and Measure, appears to be that the ‘wit’ is part of the material with which the ‘humour’ is dealing. Pater asks us to see the wit not, as earlier critics had done, as a youthful author’s fashionable vice in an age of witty conceit and modish artificialities, but as an object we are to regard through the essential humour of the treatment.

Modern critics and editors of Love’s Labour’s Lost, in contrast with those of Measure, have been much readier to recognise Pater’s importance in the critical tradition. The play’s unmistakable ‘foppery’ of language, as Pater calls it, had seemed off-putting to most of its earlier critics, as well as to theatre companies. His essay is an early and innovative insistence that a concern with style and ‘euphuism’, with fashions and modes, was a sophisticated and self-conscious theme in the play; and this is an idea that most later critics have taken for granted. One recent editor comments that Pater, exceptionally before the 1920s, ‘does justice’ to the play’s ‘curious foppery of language’ and also to Shakespeare’s own ‘ambivalent attitude towards it’.24 Most others, in going over the reception of the play, have felt at least the obligation to register in a passing mention Pater’s voice in the wilderness.

For Pater it is the humourist’s peculiar gift to be able to see the modes of contemporary life, including its small details and fribbling aspects, with something of the vision that hindsight will later give to others (‘Lamb’, App., 114–16). Shakespeare, in Pater’s view, was actively reflecting on current and recent literary styles, including his own. His true subject was ‘that old euphuism of the Elizabethan age’,25 –

that pride of dainty language and curious expression, which it is very easy to ridicule, which often made itself ridiculous, but which had below it a real sense of fitness and nicety; and which, as we see in this very play, and still more clearly in the Sonnets, had some fascination for the young Shakespeare himself. It is this foppery of delicate language, this fashionable plaything of his time, with which Shakespeare is occupied in Love’s Labours Lost.

‘Play is often that about which people are most serious’, Pater says, ‘and the humourist may observe how, under all love of playthings, there is almost always hidden an appreciation of something really engaging and delightful’ (164). Shakespeare can show this, and we ought to be engaged, delighted – to appreciate the appreciation. Pater himself, whether a humourist or not, is certainly a literary aesthete willing to give hints of his own predilection for this ‘foppery’ of language, which ‘satisfies a real instinct in our minds—the fancy so many of us have for an exquisite and curious skill in the use of words’ (166).

John Kerrigan is unusual among the more recent editors in his having taken Pater’s ‘magnificent but flawed essay’ seriously enough as to argue with it. In identifying the theme of linguistic foppery and showing how the play displays it to us in various degrees of ‘sophistication’, Pater was the first ‘to unite’, in Kerrigan’s words, ‘the high and low’, the courtiers and the commoners, explaining the ‘dramatic function’ of the latter and bringing into focus an overarching thematic cohesion. ‘In one sense’, Kerrigan judges, ‘Pater did not go far enough, though in another he went too far’. If Pater had focused less exclusively on the language theme, he might have found other things to say. ‘He overestimated the unifying power of the language theme, because he was unresponsive to the other integuments which hold the play together. Sex, for instance.’ (Unresponsive or not, it is true that Pater has nothing to say on the sexual themes or their structural import.) On the other hand, Kerrigan argues, had he thought further about the language theme, he might have been led to recognise the centrality of another theme: ‘fame’, the prize at which all the fancified talking is aimed, and a ‘more radical and inclusive principle of unity’ than the one Pater identified. The vow of studious homosocial retirement from the world (and especially from female company) made by the King and his male companions at the start of the play was not, in Kerrigan’s view, acknowledged by Pater as ‘both the lynch-pin of the action and a recurring centre of dramatic interest’. To Kerrigan it is clear that the oath belongs with the vulgar or extravagant language of the ‘low characters’, sharing with them the purpose of attracting admiration.26 What seems to be suggested here is that Pater’s silence on the theme of ‘fame’ is at least in part the consequence of a lack of interest in the sequence of events and their dramatic handling.

In one of Anne Barton’s very early essays, Pater serves as a point of reference in another discussion of the play’s ‘unity’. His ‘beautiful’ essay on ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’ provides her with a useful maxim: ‘into the unity of a choric song the perfect drama ever tends to return, its intellectual scope deepened, complicated, enlarged, but still with an unmistakable singleness, or identity, in its impression on the mind’ (App., 203–4). In her opinion, such a unity is ‘evident throughout’ Love’s Labour’s Lost, in spite of Pater’s remarks (which she also quotes) about its composition into ‘pictorial groups’:

The grouping of the characters into scenes would appear, however, to have been dictated by a purpose far more serious than the mere creation of such patterns; it is one of the ways in which Shakespeare maintains the balance of the play world between the artificial and the real, and indicates the final outcome of the comedy.27

She disagrees with Pater’s evaluation of the dramatic cohesion of Love’s Labour’s Lost by insisting that his more general comments elsewhere should be held relevant here too. She defends the play as drama by using Pater against himself. But the essay’s debts to Pater go far beyond the explicit discussion of him. ‘Often, beneath ornament and convention the Elizabethans disguised genuine emotion’, she writes, reminding us of Pater’s own defence.28 ‘Mannered and artificial, reflecting an Elizabethan delight in patterned and intricate language, Navarre’s lines at the beginning of the play are nevertheless curiously urgent and intense’: the diction, even the syntax could not be more Pateresque, but these are Barton’s words; and it is so again when she talks of the song of the Owl and the Cuckoo from the play’s end, ‘a song into which the whole of that now-vanished world of Love’s Labour’s Lost seems to have passed, its brilliance, its strange mingling of the artificial and the real, its loveliness and laughter gathered together for the last time to speak to us in the form of a single strain of music’.29 Slight touches recall some of Pater’s most famous passages: the beauty of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, ‘into which the soul with all its maladies has passed’ (Ren., 98); the ‘strange dyes, strange colours’ and human ‘brilliancy’ of the ‘Conclusion’ (Ren., 189). The phrase ‘a single strain of music’ appears verbatim in ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’ (App., 203).

It is a Paterian conception of ‘Renaissance’ that Barton evokes, too, even as she reveals what Pater leaves out of his own discussion of the play. The academic oath springs ‘from a recognition of the tragic brevity and impermanence of life that is peculiarly Renaissance’, she says, grazing Pater’s own phrase, ‘awful brevity’, in the ‘Conclusion’ (Ren., 189). She connects the humanist cult of ‘fame’ with the fact that, as she puts it (or Pater might have put it himself), ‘the thought of Death was acquiring a new poignancy in its contrast with man’s increasing sense of the value and loveliness of life in this world’. And if the other primary theme left out in Pater’s study is sex, this train of thought leads there as well. The oath, an ‘elaborate scheme which intends to enhance life, … would in reality, if successfully carried out, result in the limitation of life and, ultimately, in its complete denial’.30 It is partly because Barton’s critical idiom is in such close contact with Pater’s at this point that she allows us to see what may be behind Pater’s tight-lipped comment that the votaries are ‘of course soon forsworn’ (164), and how it might connect with his view of the ‘genial, seed-bearing’ vitality of Claudio and the ‘low’ characters in Measure, ranged on the side of life and worldly experience. The oath and the King’s judicial strictures, like Angelo’s in Measure, represent a misguided attempt to keep life at bay.

Another striking aspect of Pater’s reading of this play is his overwhelming preoccupation with the character of Biron (Berowne). He is the ‘perfect flower’ of that foppery in which Pater would like us, with Shakespeare, to see the ‘really delightful side’ and hidden depths. In him such a manner, which is merely ‘affected’ in others, ‘refines itself … into the expression of a nature truly and inwardly bent upon a form of delicate perfection’; the outward fashion ‘blends with a true gallantry of nature and an affectionate complaisance and grace’ (166). He sees things clearly, is sensitive to the feelings and conduct of social intercourse, and – as the ‘Conclusion’ to The Renaissance seems to persuade us to do – he trusts more in ‘actual sensation’ than in ‘men’s affected theories’. He ‘delights in his own rapidity of intuition’, such as ‘could come only from a deep experience and power of observation’ (167). The passage in which his qualities are described reads at times like an apologia, and Biron seems to have many of the ideal qualities of the Paterian aesthetic critic.

‘Power of observation’ is not the endowment only of the critic, but also of the ‘humourist’, and so of Shakespeare himself – an ‘observer’ and ‘spectator’ of life (‘Measure’, App., 184). Implied there is a quality of detachment. In the final sentence of the Love’s Labours Lost essay we are presented with a Biron who, though peculiarly sensitive and intelligent, is ‘never quite in touch, never quite on a perfect level of understanding, with the other persons of the play’ (169). This, together with another brief passage a little earlier, is as close as Pater comes to grappling with the more rebarbative qualities that modern critics have been much readier to see in Biron, a cynical, embittered character taken unawares by his depth of feeling. Yes, ‘that gloss of dainty language is a second nature with him: even at his best he is not without a certain artifice’ (167); but one might have expected Pater to go further, to show the glossy, defensive, and deflective reliance on tricks of ‘wit’ as a kind of irony or ‘reserve’, such as he identifies in Lamb. Shakespeare, ‘in whose own genius there is an element of this very quality’, is a sympathetic painter of it, and the essay all but overtly invites us to infer that Pater, in his emphasis on Biron, is also displaying a natural sympathy (168). He was known as a defensive, provocative conversationalist himself. Here, as in the essay on Lamb and the Montaigne chapters of Gaston de Latour, he takes it for granted that there is ‘something of self-portraiture’ in Shakespeare’s Biron, ‘as happens with every true dramatist’ (168) – but also, as in the case of Lamb and Montaigne, with the essayist.

Shakespeare’s English Kings

Biron is a figure with ‘that winning attractiveness which’, Pater says, perhaps betraying another aspect of what seems throughout a delicate and speculative identification with him, ‘there is no man but would willingly exercise’ (168). He has gallantry and grace; he is ‘the flower’ of the play’s precious euphuism (166). Claudio, in the Measure essay, was a ‘flowerlike young man’, ‘a mere gilded, idle flower of youth’, raised, in his revolt from death, to a height of Shakespearean eloquence (180–1). Both are attractive young men to whom floral imagery is applied. In ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’ we find Pater again exercised particularly by a winning and flowerlike young man, Richard II, ‘that sweet lovely rose’ (App., 189, quoting Hotspur’s line in 1 Henry 4, I.3.175). In Richard’s case there is more overt and sustained emphasis on his personal beauty, ‘that physical charm which all confessed’, and on his attractive ‘suavity of manners’ (197, 194). He is ‘graceful’, ‘amiable’ – possessed of ‘those real amiabilities that made people forget the darker touches of his character’ (195). Richard’s ‘fatal beauty, of which he was so frankly aware’, and which Pater thinks Shakespeare has dwelt upon with particular attentiveness (194), is potent in its effect:

it was by way of proof that his end had been a natural one that, stifling a real fear of the face, the face of Richard, on men’s minds, with the added pleading now of all dead faces, Henry [Bolingbroke] exposed the corpse to general view; and Shakespeare, in bringing it on the stage, in the last scene of his play, does but follow out the motive with which he has emphasised Richard’s physical beauty all through it—that ‘most beauteous inn,’ as the Queen says quaintly, meeting him on the way to death—residence, then soon to be deserted, of that wayward, frenzied, but withal so affectionate soul.

‘Affectionate’, like Biron. Readings of Richard’s character have rarely been so affectionate.

Richard II had been a set text in Pater’s school days, forming part of the Sixth Form examination in July 1858.31 At his school’s Speech Day in the same year, the part of Richard in an extract from the play was played by Pater’s close friend Henry Dombrain, with whom Pater and a third friend, John Rainier McQueen, had a year earlier at the same event performed a scene from Henry IV, Part I – Pater playing Hotspur, and very probably speaking the line about the old King Richard as a ‘sweet lovely rose’.32 Unlike the other plays, moreover, Richard II is one Pater had seen professionally performed. It was in the same year, 1858, that he saw Charles Kean’s magnificent production at the Princess’s Theatre, an experience he recalls evocatively in the essay, three decades later. ‘In the hands of Kean the play became like an exquisite performance on the violin’ (195).

In Pater’s reading, Richard is an aesthete, a poet by nature, who happens to be a king. Shakespeare’s English Kings are ‘a very eloquent company’, Pater says, ‘and Richard is the most sweet-tongued of them all’ – ‘an exquisite poet if he is nothing else, from first to last, in light and gloom alike, able to see all things poetically, to give a poetic turn to his conduct of them’ (194). He is the spin-doctor of his own downfall, even if, in the final analysis, the spin is mainly for his own benefit. But, just as Kean’s performance could resemble an ‘exquisite performance on the violin’, so Richard’s performance of himself, as he ‘throws himself into the part’ that Fate and his enemies have assigned him, and so ‘falls gracefully as on the world’s stage’ (198), is compared with wordless music: ‘As in some sweet anthem of Handel, the sufferer, who put finger to the organ under the utmost pressure of mental conflict, extracts a kind of peace at last from the mere skill with which he sets his distress to music’ (200). This is not only the comfort of poetry as reinterpretation, poetry as rhetoric; it implies the comfort of the aesthetic more narrowly defined, of aesthetic form in itself as soothing, or perhaps of the capacity of verbal artistry to accommodate one to circumstance by enacting, through a beautified and rhetorically controlled and contrived speech, the nature, as speaker, of a role with which one must identify: the role made acceptable through the fashioning of the speech which delineates it, imaginatively, creatively, in a way to which one can adjust one’s own sense of self. In Pater’s words, Richard in his ordeal ‘experiences something of the royal prerogative of poetry to obscure, or at least to attune and soften men’s griefs’ (200). Poetry can console by reinterpreting circumstance, by obscuring certain facts, which might amount to a softening of grief; but it can also soften by attuning the feelings. Attunement, as accommodation, may be of self to circumstance, as in Richard’s poignantly self-indulgent speech about ‘worms and graves and epitaphs’ (III.2.144–77). But attunement is more than accommodation; it suggests harmony as judged by aesthetic instinct.

Pater’s essay instigated what might be called the ‘aesthetic’ reading of the play, associated later with C.E. Montague and W.B. Yeats.33 The aesthetic approach was vigorously repudiated by Edward Dowden and others of a more ‘moralistic’ persuasion, who ‘tended to stress Richard’s contemptible weakness and want of virility’.34 Yeats pleaded for Richard’s ‘fine temperament’ and ‘contemplative’ nature, calling him ‘an unripened Hamlet’: ‘I cannot believe that Shakespeare looked on his Richard II. with any but sympathetic eyes, understanding indeed how ill-fitted he was to be King, at a certain moment of history, but understanding that he was lovable and full of capricious fancy, “a wild creature” as Pater has called him.’35 Denis Donoghue frames matters in a more politicised way when he writes that ‘Pater started a little fashion of saying that Shakespeare’s imagination was ashamed of its duty’ – the duty, that is, of legitimising and celebrating the Tudor dynasty and its antecedents – ‘and insisted on giving the defeated kings the most touching lines’.36

A.C. Bradley, whose influence on twentieth-century Shakespearean criticism and pedagogy was perhaps pre-eminent, offers a middle-ground reading of Richard. In a lecture given in 1904 he classes him among those, like Romeo and Orsino, of an ‘imaginative nature’, but draws attention also to the ‘weakness’ inherent in such natures.37 Like Pater, and Hazlitt before him, Bradley was particularly responsive to, and has sometimes been held accountable for others’ overemphasis upon, subtleties of ‘character’. In his non-Shakespearean lectures, he speaks of Pater admiringly, even citing him as an ‘authority’.38 The fact that Bradley in his monumental writings on Shakespeare focused mainly on characters and plays that Pater did not (or not substantively) discuss, leaves us to wonder whether Pater’s place in the background of mainstream twentieth-century Shakespearean studies might have been easier to see had Bradley chosen any of the same few plays for his prime examples. But Pater directed his appreciative efforts onto jewels that others tended to tread over without stooping, and the refined alterity of his reading of Shakespeare was not Bradley’s way.

More modern critics and editors of Richard II, though they sometimes recall, as an extreme example, Pater’s sympathetic reading of its protagonist, have generally been more mindful of one particular passage in the essay:

In the Roman Pontifical, of which the order of Coronation is really a part, there is no form for the inverse process, no rite of ‘degradation,’ such as that by which an offending priest or bishop may be deprived, if not of the essential quality of ‘orders’, yet, one by one, of its outward dignities. It is as if Shakespeare had had in mind some such inverted rite, like those old ecclesiastical or military ones, by which human hardness, or human justice, adds the last touch of unkindness to the execution of its sentences, in the scene where Richard ‘deposes’ himself, as in some long, agonising ceremony …

Pater’s phrase ‘inverted rite’ is still regularly quoted, especially by editors, though few now seem interested in returning to the essay in detail. An editor who did was John Dover Wilson in 1939. First declaring that Pater’s essay on Love’s Labour’s Lost was ‘the only critique with any understanding of that play which appeared during the nineteenth century’, Dover Wilson expresses his agreement with Pater’s emphasis on the ‘simple continuity’ of Richard II, and his estimation of the style’s appropriateness to the matter. Pater is ‘the one writer to see’ that the play has more in common with the Catholic Mass than with a play by Ibsen or Shaw, and ‘ought to be played throughout as a ritual’. Pater’s commentary on the deposition scene ‘goes to the heart of the play, since it reveals a sacramental quality in the agony and death of the sacrificial victim’.39 Pater’s insight in this regard was also acknowledged by the historian Ernst Kantorowicz in his important study of medieval ‘political theology’, The King’s Two Bodies (1957), containing his own brilliant reading of the relevant scene. ‘Walter Pater has called it very correctly an inverted rite, a rite of degradation and a long agonizing ceremony in which the order of coronation is reversed.’40

‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’ is significant more generally in its emphasis on ‘the irony of kingship’ as a unifying theme in the history plays, with Richard ‘the most touching of all examples’ (189). ‘The irony of kingship—average human nature, flung with a wonderfully pathetic effect into the vortex of great events’: this is the side of kingship Shakespeare has made ‘prominent’ in his histories, making ‘the sad fortunes’ of these pre-eminent individuals ‘conspicuous examples of the ordinary human condition’ (185–6). Pater’s is the classic critical expression of this idea: ‘No! Shakespeare’s kings are not, nor are meant to be, great men: rather, little or quite ordinary humanity, thrust upon greatness, with those pathetic results, the natural self-pity of the weak heightened in them into irresistible appeal to others as the net result of their royal prerogative’ (199). ‘No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be’, says Eliot’s Prufrock, remembering, perhaps ironising, Pater, but also using Pater’s ‘irony of kingship’ in his effort to ironise himself. He is no king, no prince, not thrust upon greatness, with no great momentous decisions to make – only ordinary human nature in an ordinary condition, or thrust upon petty banalities which, being the material of a life, have a trick of feeling weighty.41 As Eliot’s echo registers, Pater’s focus is again on personal experience, the single nature in contact with circumstance. The sense of this irony, which Pater makes us feel, elicits sympathy with the individual.

Richard oscillates between eloquent meditations on his frailty and precariousness – as of any other person, though with further to fall and stronger enemies – and proud declarations of his divine sanction as anointed monarch. He takes rhetorical hold of the glimpses he has of his own ironic situation. ‘And in truth’, Pater says, ‘but for that adventitious poetic gold, it would be only “plume-plucked Richard”’ (199). His is the ‘ordinary human condition’, heightened by a streak of the poetic that is itself only adventitious. The ‘strong tyranny’ of chance here becomes, in another variation on the notion Pater raises in all his Shakespeare studies, ‘the somewhat ironic preponderance of nature and circumstance over men’s artificial arrangements’ (188). Arrange a system to choose you a king, and you may well end up the fool of those ironists, Nature and Circumstance, whose unpredictable concurrences and cohesions Pater finds so powerfully portrayed in the works of Shakespeare.

Conclusion

Christopher Ricks is particularly impatient with the preoccupation with finesse in the Shakespeare essays. Pater wanted something ‘finer than fineness’, says Ricks, and was attracted to Measure mainly because it showed Shakespeare reworking a rougher source to ‘finer issues’ – Pater’s own phrase, but borrowed, as Ricks reminds us, from the play: ‘Spirits are not finely touch’d, / But to fine issues’ (I.1.35–36). Shakespeare refines. Pater, in a critical response that is itself ‘creative’ (for Ricks not a term of praise), refines further.42

Cognates of ‘fine’, however, are not the only central or repeated words across these essays. In Measure we have, in close connection with them, justice and the just; also ‘grace’ – but not another word which might have seemed salient, ‘mercy’. What would Pater have made of The Merchant of Venice? ‘Grace’, unlike ‘mercy’, has both moral and aesthetic senses, its spiritual or theological meaning contributing potentially to the aura of both. In an essay so clear about the intertwining of ethics and aesthetics, that slippage or ambivalence is both useful and suggestive. ‘Fine’ may seem better suited to aesthetics than to ethics, but when allied with ‘justice’ it again helps to make the essential connection; while ‘just’, as in the phrase le mot juste, can have its aesthetic applications too; and the basically moral idea of justice is not insignificant to Pater’s frequent use of ‘just’ as a modifier implying critical or artistic discrimination: just here, just there, just that, in just this way. In ‘Love’s Labours Lost’, Pater’s emphasis on styles of language might seem to tip his vocabulary towards more clearly aesthetic terms or senses – grace, delicacy, daintiness, refinement; but his insistence on the depths underlying ostensibly superficial fashions encourages us to see the moral correlatives of these qualities, and the essay gravitates towards a consideration of the connections between manner and temperament. ‘Intuition’ is a moral quality; Biron’s attractiveness is more than a surface appearance but a matter of conduct and appeal to sympathy. In all three essays, poetry, style, eloquence, and beauty are shown in their relations to the inner life – especially in Biron and Richard – and with the moral faculties, whether in a wide or, as in Measure, even in a narrow sense: the matter of justice and judgment.

What, in sum, does Shakespeare seem to have meant to Pater? Large sympathies; a sensitivity to difficulties of ‘moral interpretation’; a ‘finer justice’, in part manifested through a commitment to the many-sidedness of real life and the avoidance of simple lessons. Pater’s Shakespeare does not sympathise only with the refined, but also with the coarse ‘low’ characters in their ‘vivid reality’ and ‘pride of life’. He is a poet of the ‘tyranny’ of chance, of life’s ironies in the junctures of ‘nature and circumstance’; but also a humourist who can see the real significance of apparently small or trivial things. And the fineness of his work, as a workman, cultivates in appreciative readers a fineness of judgment which is of a piece with the sympathetic morality he offers. Love’s Labour’s Lost, especially in the person of Biron, offers, in Pater’s words, ‘a real insight into the laws which determine what is exquisite in language, and their root in the nature of things’ (166). Fineness and delicacy in poetry do not exist in a sealed-off world of art: their roots are in reality, where we live as practical, moral agents, however far some may withdraw to the position of spectator or observer.

Pater’s ‘Sir Thomas Browne’ begins by observing the lawlessness and lack of classical balance in early modern English prose. While ‘English prose literature towards the end of the seventeenth century’, Pater writes, ‘was becoming … a matter of design and skilled practice, highly conscious of itself as an art, and, above all, correct’, the earlier literature was ‘singularly informal’ and ‘eminently occasional’, marred by ‘unevenness, alike in thought and style; lack of design; and caprice’. A few early exceptions, like Hooker, Latimer, and More, instituted a ‘reasonable transparency’, ‘classical clearness’. Otherwise, before Dryden and Locke, English prose was wayward. Of such writers, Browne was, Pater tells us, ‘[t]he type’ (App., 124–5).

And yet. Despite these faults, there are compensations to be found. Pater writes:

in recompense for that looseness and whim, in Sir Thomas Browne for instance, we have in those ‘quaint’ writers, as they themselves understood the term (coint, adorned, but adorned with all the curious ornaments of their own predilection, provincial or archaic, certainly unfamiliar, and selected without reference to the taste or usages of other people) the charm of an absolute sincerity, with all the ingenuous and racy effect of what is circumstantial and peculiar in their growth.

Pater’s inverted commas abstract ‘quaint’ from the flow of his prose and distance him from its use, an effect compounded by the parenthesis stalling the sentence’s progress in mimicry of the distractible prose of the seventeenth century, with its habits of self-annotation and erudite display.1 Reluctantly, Pater finds a charm in quaintness. Something in Browne beguiles.

This chapter aims to expose what ‘quaint’ means for Pater, and the work it does in his criticism. Despite the inverted commas, it is a word which appears frequently – a tic of Pater’s critical prose. Its meaning, however, is never directly addressed: the closest Pater gets to a definition is his parenthesis on ‘coint’. It is nonetheless, as I hope to show, a keyword, marking a simultaneous discomfort with and interest in the lingering appeal of outmoded aesthetic objects which connects it to Pater’s broader theoretical statements on style, and on the relationship between classicism and romanticism. Pater’s use of ‘quaint’ is idiosyncratic, but connected to a wider pattern in criticism: on the one hand, the attempt of his predecessors and contemporaries to account for Browne’s peculiarity, what Coleridge called his ‘Sir-Thomas-Browne-ness’; on the other, a vogue for the word as a critical term which, as we will see, has strong and ambivalent associations. The later part of this chapter shows how Pater’s quaintness fits in the longer history of the reception of Browne, a history which traces changing attitudes to difficulty, Latinity, and ‘metaphysical’ style. These qualities were associated with forms of religion and philosophical education which were rejected in the later seventeenth century, just as ‘classical clearness’ became the ideal of prose, and they have remained variously embarrassing, threatening, or appealing ever since: a complex of aesthetic effects which ‘quaint’ works both to name and conceal.

Quaintness of Mind

What does ‘quaint’ mean? Derived ultimately from Latin ‘cognitus’ – a person or thing known, acknowledged, approved – it comes into English in the thirteenth century from the Anglo-Norman cointe: astute, clever, fashionable, devious, ingenious. Its earliest appearances in English fall under this rubric; over the centuries, it slips from associations with cunning, craftiness, and ingeniousness to ornament and elaboration, and thence into affectation, daintiness, fastidiousness, whether applied to persons, speech, or style.2 Of the nine main definitions offered by the OED, only three are not now marked as obsolete. The last citation for the sense most relevant to writing – ‘carefully or ingeniously elaborated; highly elegant or refined; clever, smart; (in later use also) affected’ – is from 1841. What survives is what the dictionary now deems to be the ‘usual sense’: ‘attractively or agreeably unusual in character or appearance; esp. pleasingly old-fashioned’, first registered in 1762.3

The word ‘quaint’ is thus now itself quaint. That its senses related to ingeniousness, cunning, and ornament should obsolesce, leaving only today’s faint residue as a mark of the quirkily old-fashioned, is ironic. In ‘Sir Thomas Browne’, Pater foregrounds both the obsolescence and the irony. His account is deliberately archaic: the ‘quaint’ writers are quaint not only in a contemporary sense, but ‘as they themselves understood the term’. Pater’s gloss supplies not quite a definition of ‘quaint’, but a characterisation: adorned, but strangely or excessively so, with ‘curious ornaments’ idiosyncratic to the writer, pursued with a kind of blind determination which ignores the taste of the generality. Pater’s italics and inverted commas present the words ‘quaint’ and ‘coint’ as specimens. ‘Coint’ offers the Anglo-Norman spelling; it is an archaic fossil in Pater’s own prose. Whether Pater knew it or not, it also had an air of the antique for Browne: in the seventeenth century, the French form appears only in editions of Chaucer, etymological notes on Milton, and dictionaries of French or older English. Coint was marked as either foreign or archaic. This doubleness, in which ‘quaint’ and ‘coint’ at once characterise obsolete styles of language and exemplify them, is typical of the word’s ambivalence.

‘Quaintness’ recurs in the Browne essay particularly in connection with Browne’s Hydriotaphia, or Urne-Buriall (1658): a treatise in five chapters which takes as a prompt the discovery of urns buried in a field near Walsingham, Norfolk. Browne’s initial displays of antiquarian erudition on the sepulchral and funereal practices of the ancients transform into arias of ornate prose on the inevitability of oblivion, the futility of monuments, and the necessity of trust in the Resurrection. That the work’s subject is the more literal resurrection of the artefacts of antiquity and the relics of long-dead people keys it closely to Pater’s double quaintness, and the antiquarian revivification of the obsolete.

It is therefore no surprise that ‘quaintness’ is important in Pater’s discussion of Hydriotaphia. It is a composition, he writes, which ‘with all its quaintness we may well pronounce classical’ (154). Pater expands:

Out of an atmosphere of all-pervading oddity and quaintness—the quaintness of mind which reflects that this disclosing of the urns of the ancients hath ‘left unto our view some parts which they never beheld themselves’—arises a work really ample and grand, nay! classical … by virtue of the effectiveness with which it fixes a type in literature …

This is a tonally and rhythmically sympathetic sentence, working out its sense with the echo of Browne in the ear. The period style steals out from the quotation to render Pater’s ‘hath’ archaic; the interjection of ‘nay!’ has just the touch of simultaneous oddity and amplitude which he diagnoses, poised between quaint and grand. As a review of Appreciations claimed, ‘Pater really renders [Browne] for us, conveying to us the finest inflexions of his voice as if by some eclectic telephone’.4 If Pater’s essay is a technology which revives Browne’s long-dead voice, then his sympathetic and emulative criticism performs its own quaint archaisms.

The passage also registers Browne’s mixture of grandeur and bathos: his ability to generate multum ex parvo, to take the negligible or minute and derive from it sublimity, to spin from the uncovered urns both reams of erudite lore, and splendid passages of elegant writing on oblivion. Samuel Johnson wrote of Browne that ‘it is a perpetual triumph of fancy to expand a scanty theme, to raise glittering ideas from obscure properties, and to produce to the world an object of wonder to which nature had contributed little’.5 The Garden of Cyrus, the companion piece to Hydriotaphia, takes the quincunx (a pattern of five dots arrayed as a square with one in the middle), and makes it the leitmotif of God’s creative energy discovered in nature. ‘Quaintness’ here marks the oxymoron of something at once triflingly oblique and monumental.

In the opening of ‘Sir Thomas Browne’, Pater makes it sound as if ‘quaint’ is a strange word, a foreign and archaic fossil lodged in the purer classical throat of the language. But this is the only place where he holds ‘quaint’ gingerly in the prophylactic tweezers of inverted commas; elsewhere, the word is unostentatiously a feature of his own critical vocabulary. Though Browne is the type of the quaint writer, it is a word which peppers Appreciations, The Renaissance, Greek Studies, and Imaginary Portraits, as well as the novels. Across Pater’s work, it becomes possible to discern contours of the quaint and its siblings. It is collocated with antiquity and antiquarianism, oddity, heterogeneity, curiosity, conceits, the grotesque, remoteness, foreignness, barbarity, and the medieval. It appears differently in different media. In literature, in regard to content, it is antiquarianism, an interest in minute discriminations, and an erudite assembly of disparate material; in style, elaborate, recondite, or archaic vocabulary and syntax. In art, it is attention, or over-attention, to ornament and decoration, varying the texture of fabric or pavement or sward with repetitive patterns or floral motifs. It fetishises archaism. We hear, for example, that Sir Thomas More wrote a life of Pico della Mirandola in ‘quaint, antiquated English’ (‘Pico della Mirandola’, Ren., 27). That near-anagram of ‘quaint’ and ‘antiquated’ stresses the sense the word always carries, in Pater, of historicity.

‘Nothing’, writes Grace Lavery in her recent study of fin-de-siècle japonisme, ‘is quaint from the get-go; an object, text, body, or event acquires the quality of quaintness as it becomes historical—or, more precisely, as it fails to become historical’. The oddity of quaintness, for Lavery, is of something which has persisted beyond its time, which comes trailing its history into the present.6 Pater shares this sense of quaintness as marking a temporal residue, but with a subtle difference. Pater’s quaint is not a measure of how far a work differs in its aesthetic protocols and canons from his present, but a detection of a work’s internal anachronisms and incongruities. Some things, contra Lavery, are quaint from the get-go, carrying within themselves a temporal differentiation of surplus historicity even before they have retreated into the past. This is obvious in Pater’s comments on the archaisms of Coleridge’s ‘Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner’. It is not just overt pastiche, however, which Pater calls ‘quaint’. As Uttara Natarajan remarks of the Lamb essay, ‘Pater declares that Lamb endows the present itself with the quality of past-ness’.7 Pater finds in Lamb an ability to see a future-perfect quaintness – what will have become quaint – in the present. Lamb, as Pater puts it, ‘anticipates the enchantment of distance’. He preserves ‘[t]he quaint remarks of children which another would scarcely have heard’ like ‘little flies in the priceless amber of his Attic wit’ (‘Charles Lamb’, App., 115, 110). Like the urns of Hydriotaphia, Lamb’s essays are a medium preserving quaint ephemera.

Modern discussions of quaintness account differently for this fossilised persistence of a previous era in the art of the present. Daniel Harris suggests that quaintness is what happens to the tools of work and forms of labour of prior periods when they have been technologically superseded, and are used aesthetically or ironically in the present: a typewriter deployed as an ornament; artificially distressed furniture; fashions for artisanally produced food and clothing.8 This is not what Pater registers, however. While the opposite of Harris’s quaintness is the modern, the consumerist, the new, the opposite of Pater’s is the classical, the regular, the orderly: the timeless. In Pater’s quaintness, it is not that the aesthetic object is appealing because obsolete, but that its appeal is troubling because it manifests historical inconcinnity, a persistence of superseded styles.

This is closer to Lavery, for whom ‘quaint temporality’ is ‘an aesthetic and elliptical feeling of historicalness’ which at the same time refuses to conform to the ‘more muscular historical explanations’ of historicism; ‘what finally defines the quaint’, she writes, is ‘its irretrievability by any major history’.9 It is historical while refusing to be typical, maintaining its minor irrelevance. That Pater, too, is interested in the relation of the quaint to historicism is explicit in ‘Two Early French Stories’, where he addresses the appeal of the antique, and its relation to aesthetic anachronism. ‘To say of an ancient literary composition that it has an antiquarian interest’, he writes, ‘often means that it has no distinct aesthetic interest for the reader of today’. This is not to say that it does not have its pleasures, but the appeal involves an anachronistic posture: ‘Antiquarianism, by a purely historical effort, by putting its subject in perspective, and setting the reader in a certain point of view, from which what gave pleasure to the past is pleasurable for him also, may often add greatly to the charm we receive from ancient literature.’ There is no point, however, unless there is ‘real, direct, aesthetic charm in the thing itself’: ‘no merely antiquarian effort can ever give it an aesthetic value, or make it a proper subject of aesthetic criticism’. The critic takes pleasure in the attempt to ‘define, and discriminate’ this real charm from the ‘borrowed interest’ of antiquarianism (Ren., 14–15).

‘Quaint’ then sits for Pater at a point of crisis, in that word’s etymological sense. It marks a point of decision, where the critic determines between what is purely antiquarian, and what is of enduring and transcending aesthetic value. Sometimes, ‘quaint’ names the first pole of that opposition: those things which have historical charm but not beauty, which are merely curious. This critical sifting is clear in the Browne essay, which repeatedly attempts to separate Browne’s beauties from ‘what is circumstantial and peculiar’ (126), the classical from the quaint. But Pater finds them perplexingly inextricable. Peculiarity and strangeness are not burned off in the flame of aesthetic criticism. When Pater writes that, in Hydriotaphia, ‘a work really ample and grand’ arises ‘[o]ut of an atmosphere of all-pervading oddity and quaintness’, or that ‘with all its quaintness we may well pronounce [it] classical’, the initial sense is surprise and concession (156, 154). But the suspicion that oddity and quaintness are the materials out of which the grandeur emerges, that it is classic not despite but with quaintness, still lurks.

The essay on Botticelli in the Renaissance addresses this problem directly. For Pater, Botticelli’s Venus typified his strange combination of ‘classical subjects’ with realism in depiction of the Italian landscape and its people. Pater is again attuned to stylistic anachronism: in the painting, ‘the grotesque emblems of the middle age, and a landscape full of its peculiar feeling, and even its strange draperies, powdered all over in the Gothic manner with a quaint conceit of daisies, frame a figure that reminds you of the faultless nude studies of Ingres’. Pater strikes nearly every adjective in his repertoire of quaint collocations: grotesque, medieval, peculiar, strange, Gothic, conceited. What makes the quaintness remarkable is its anachronism: the jarring effect of its yoking with something classical, something recognisably of a different aesthetic order. Pater harps on the word. ‘At first, perhaps’, he writes, ‘you are attracted only by a quaintness of design, … afterwards you may think that this quaintness must be incongruous with the subject’. Quaintness is attractive but inappropriate, and a mature aesthetic sense must surely reject it. But eventually, when ‘you come to understand what imaginative colouring really is, … you will find that quaint design of Botticelli’s a more direct inlet into the Greek temper than the works of the Greeks themselves’ (‘Sandro Botticelli’, Ren., 45–6). If ‘quaint’ registers anachronism, here the usual temporal relation is reversed: rather than the uncanny or unexpected survival of the antique into the present, Botticelli manifests the spirit of Greek style more vividly than it was realised in the place or period for which it was named.

Pater’s insistence on Botticelli’s quaintness reflects one of the main resonances of the term in the late nineteenth century: its association with the Pre-Raphaelites, for whom Botticelli was a particular model. In David Masson’s early critical assessment, published in the British Quarterly Review in 1852, a ‘studied quaintness of thought, most frequently bearing the character of archaism, or an attempt after the antique’ is the ‘third peculiarity of the Pre-Raphaelite painters’, after their disregard for established aesthetic canons and ‘fondness for detail, and careful finish’.10 The Pre-Raphaelites were thereafter so persistently linked with quaintness that Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in a letter of 2 August 1871 to fellow artist and poet William Bell Scott, bewailed the revival of ‘that infernal word “quaint”’. ‘I cannot see the faintest trace of this adjective in either of your etchings … nor in the design of your mantelpiece’, Rossetti consoled Scott, ‘though I suppose … it might be described as peculiar, if that is one meaning of the hellish “quaint”’.11 Rossetti’s oxymoron, applying the sulphuric terms ‘infernal’ and ‘hellish’ to the belittling ‘quaint’, indicates both his frustration with a term which does not seem to take its subject seriously, and quaintness’s own typical incongruity.

Masson’s ‘attempt after’ suggests that quaintness is an unsuccessful pastiche of the antique – the opposite of what Pater finds in Botticelli. This is not the only distinction in their use of the term. Although Masson introduces it as a ‘peculiarity’ of painters, he turns to the writing of the Pre-Raphaelites for examples. The desire to be true to nature, he argues, results in ‘a kind of baldness of thought and expression, a return to the most primitive style of thinking and speaking; a preference … for words of one syllable’. Masson’s immediate example is Wordsworth – whom Pater only once, and glancingly, designates ‘quaint’, for his use of ‘a certain quaint gaiety of metre’ (‘Wordsworth’, App., 58). Quaintness for Masson leads away from ‘artificiality and rhodomontade’, towards ‘an affected simplicity often offensive to a manly taste’.12 Neutral description tips into implicit critique: there is something juvenile and artificial about the quaint.

Though Pater frequently uses the phrase ‘quaint simplicity’, this is not what he finds in Browne, whom no one could accuse of being simple. Browne’s quaintness is complexity, overwroughtness, involution. Nonetheless, Masson’s discussion of the Pre-Raphaelites links with the roots of the vogue for quaint in nineteenth-century criticism. To object to ‘quaint’ as infernal and hellish seems an escalation of register. But it fits with what I will argue, later in this chapter, is the apotropaic role that ‘quaint’ has for some of Pater’s contemporaries.

The Quaintness of Sir-Thomas-Browneness

Opening a review of a new edition of Thomas Browne in 1923, Virginia Woolf lamented its limited scope and its high price, despite the editors’ claim of ‘a great revival of interest in the work of Sir Thomas Browne’. ‘But why fly in the face of facts?’ she went on: ‘Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne, but those who do are of the salt of the earth.’13 Woolf’s suggestion of coterie connoisseurship sits with Pater’s remarks on historicism in ‘Two Early French Stories’. A passion for Browne, Woolf implies, is at once a minority interest, and a litmus of cultivated taste.