Introduction

Portugal inaugurated the ‘third wave of democratisation’ in Europe in the mid-1970s, following four decades of authoritarian rule (Huntington Reference Huntington1991). The military coup that opposed the dictatorial regime inaugurated by Salazar (1932–68) and continued by Caetano (1968–74), along with its colonialist policies (Varela, Simões de Paço, Alcântara et al. Reference Varela, Simões do Paço, Alcântara and Ferreira2015), relied on widespread social mobilisation and engagement of civil society against the hierarchies that had dominated the political, economic, social, and cultural sectors (Bermeo Reference Bermeo, Collier and Berins Collier1997; Fishman Reference Fishman2019). Whereas the Carnation Revolution remains one of the most remarkable memories in Portuguese society (Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira et al. Reference Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira, Raimundo, Flores, Santana Pereira, Heyne, Cabrita, Manucci and Vicente2024), scholars continue to interrogate its legacies in the current sociopolitical landscape.

At the heart of this debate lies the way in which the transition from dictatorship to democracy unfolded. The break with the authoritarian past relied on the unprecedented strength of the coalition between self-organised civil society and institutions, which eventually imprinted, according to some scholars, an inclusive ethos in Portuguese democracy (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014; Cerezales Reference Cerezales2017; Fishman Reference Fishman2019). The inclusion and lasting presence of principles of participatory democracy in the 1976 Constitution – considered one of the most progressive in Europe – is taken by many as evidence of this. The inclusion of powerless voices in political debate also corroborates this foundational character of Portuguese democracy, which builds on strong elite–mass linkages and permeable institutions (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014; Fishman Reference Fishman2011; Reference Fishman2019).

Nevertheless, the sharp decline in political participation in the last few decades, widely discussed in the literature (de Sousa, Magalhães and Amaral Reference de Sousa, Magalhães and Amaral2014; Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014), is ‘particularly striking by the fact that the Portuguese transition to democracy involved massive levels of political mobilisation and activism, which seem to have all but disappeared’ (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2005, p. 988). Some argue that the magnitude of hopes raised during the brief revolutionary period in 1974–75 eventually led to pervasive disappointment (Hammond Reference Hammond1988). Others highlight the enduring legacy of the dictatorship, which imposed ‘[a]n omniscient state, the culture of passivity, the weakness of civil society, the values of “order”, the culture of deference, and the persistence of clientelism’ (Costa Pinto Reference Costa Pinto2006, p. 196). According to Ramos Pinto (Reference Ramos Pinto2013), the decrease in democratic participation can be attributed to either the perceived collapse of revolutionary ideals or the success of the ‘counterrevolution’ of mainstream political parties that eventually established liberal democracy. In fact, Santos and Arriscado Nunes (Reference Santos and Arriscado Nunes2004) contend that the progressive ethos embedded in the constitution has often remained unfulfilled, and participatory democracy has functioned more as a guiding principle than as a concrete set of institutional arrangements.

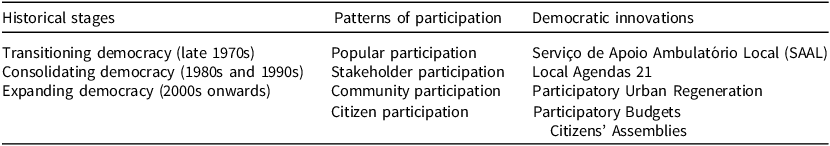

This paper departs from this contentious issue to interrogate practices of citizen participation beyond the ballot box, also known as ‘democratic innovations’ (Smith Reference Smith2009; Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019). By adopting a genetic approach (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Champagne, Lenoir, Poupeau, Rivière and Fernbach2024), the paper examines the state structures developed from the revolution onwards to comment on exemplary cases of democratic innovation, understood as specific fields of state–society relations. The examples are selected according to available documentation and do not aim to offer a comprehensive view of this type of practice. Rather, they serve to discuss the changing nature of democracy and democratic innovations by tracking different patterns of participation across three main stages, each chosen as representative of a crucial historical period.

In the first historical stage, as the military established the ‘Revolutionary Ongoing Process’ in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution, popular participation was claimed by base-level organisations seeking long-suppressed democratic rights towards open and free democratic elections. Simultaneously, movements, occupations, and self-management initiatives converged towards a sociopolitical milieu that, by compensating for lacking social services, reclaimed a new civic space. With the revolutionary period coming to an end in 1975, the second historical stage saw the consolidation of a Western liberal democracy through the adoption of the 1976 constitution (Costa Pinto Reference Costa Pinto, de Sousa and Magalhães2013; Papadogiannis and Pinto Reference Papadogiannis and Ramos Pinto2023). After joining the European Union in the mid-1980s, civil society organisations expanded (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014), alongside growing international expertise geared towards responding to calls for stronger citizen participation in policymaking (EU 2001; Chilvers Reference Chilvers2008). In the third and most recent historical stage, such calls have been accompanied by a constant decline in political participation and an effort to expand democracy through a range of diverse innovations (OECD 2023).

Against this backdrop, the trajectory of democratic innovations in Portugal calls for a critical understanding of the patterns of participation that have developed in this young democracy. While acknowledging the crucial role played by elections and direct mechanisms of participation – such as referendums, petitions, consultations, and local councils (de Almeida Reference Almeida2022) – this paper fills a knowledge gap on democratic innovations and their connections to the revolution. Therefore, this study helps unpack whether and how the progressive and inclusive ethos celebrated by some in Portuguese democracy, but seen with scepticism by others, has underpinned patterns of participation throughout the first 50 years of democracy.

The main argument of this paper is that the revolution played a crucial role in establishing social democratic values, which have been appropriated and reshaped since 1974. Rather than ‘children of the revolution’, the practices analysed appear to be ‘children of their time’ – a time that changes, but that does not erase the lessons learned in the past. To present this argument, the article first outlines its conceptual framework and approach, introduces the main features of the Carnation Revolution, and explores exemplary democratic innovations associated with three main historical stages.

Democratic innovations: A genetic approach

The scholarly debate on the key features of citizen participation has been intense and long-standing in modern history. Some scholars have viewed with scepticism the implementation of practices beyond the election of representatives, which they regard as the primary mechanism for ensuring stable regimes (Schumpeter Reference Schumpeter1976). In contrast, participatory democrats have advocated for stronger democracies based on expanding citizen engagement beyond the ballot box, aiming to ensure more inclusive political participation (Barber Reference Barber1984). Building on similar assumptions, deliberative democrats have emphasised the value of fostering thoughtful citizen reflection on key public issues alongside state action, within settings characterised by equality, inclusivity, and mutual respect (Habermas Reference Habermas1992).

While participatory and deliberative democrats share a common concern with the role of citizens in the democratic system, their approaches have often diverged in operational terms, though they may at times be complementary. Participatory approaches typically promote broad engagement aimed at empowering social groups directly affected by specific issues (Pateman Reference Pateman1970). Deliberative approaches, by contrast, tend to involve smaller samples of participants, often randomly selected, with minipublics among the most well-known examples of this model (Bächtiger and Goldberg Reference Bächtiger and Goldberg2020). The diffusion of participatory and deliberative approaches has attracted increasing scholarly attention, culminating in Smith’s (Reference Smith2009) conceptualisation of democratic innovations as institutions that deepen the role of citizens in decision-making. More recently, Elstub and Escobar (Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019) have argued that democratic innovations help to reimagine the role of citizens in democratic governance.

Democratic innovations are thought to enhance the overall quality of representative democracy and to help bridge the gap between institutions and citizens (Newton and Geißel Reference Newton and Geißel2012). This argument has gained traction in recent years, particularly in light of widely discussed trends of democratic backsliding, spurred by multiple, simultaneous crises and growing public disaffection with political institutions (Warren Reference Warren2017). In response, scholars have argued that democratic innovations may increase political trust and the legitimacy of decision-making by creating a positive feedback loop between institutions and their constituencies (Dryzek and Hendriks Reference Dryzek, Hendriks, Fischer and Gottweis2020). Indeed, such efforts hold the potential to transform power relations within society and to address long-standing injustices (Wright Reference Wright2010). This suggests that civil society organisations and movements can play a crucial role as partners of the state within democratic innovations, provided they have equitable access to decision-making on issues of public concern (della Porta and Felicetti Reference della Porta and Felicetti2022).

Innovative practices that bring together institutional and social actors around matters of public concern rest on the premise that democracy is far from monolithic and does not self-replicate through time. Therefore, innovation can be historically and contextually situated through Bourdieu’s genetic approach.

Bourdieu conceptualises the state as the exercise of symbolic imposition that shapes institutions and practices (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977). State structures become naturalised within society and are embodied through individual habitus, which in turn shape and signify the structures themselves. Through genetic analysis, Bourdieu contends that the state – and everything that derives from it – can be understood as a historical construct, since we, along with our ways of thinking, are ‘inventions of the state’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Champagne, Lenoir, Poupeau, Rivière and Fernbach2024, p. 115). By striving to free ourselves from preconstructed mental categories, the universal forms of the state within specific fields can be uncovered, and the logic of historical change made visible.

Within this framework, democratic innovations can be understood as embodiments of the state–society relation, underpinned and shaped by patterns of participation specific to different historical stages. In Bourdieu’s terms, democratic innovations can be seen as fields in which the state has acted according to specific rules – provided that these ‘games’ are capable of transforming the rules themselves through the action of society. This dynamic reveals the tension at the heart of democracy’s evolving nature, as democratic innovations – and state–society relations more broadly – simultaneously reflect and reshape that evolution. In a similar vein, Baiocchi (Reference Baiocchi2005) refers to ‘state–civil society regimes’ as the creation of specific logics that sustain practices of citizen engagement, redefining the balance of power and the role of the past in shaping the present.

Setting the scene: The Carnation Revolution

The dictatorial regime in Portugal maintained a combination of overt repression and ‘enforced apathy’ that – despite Caetano’s late attempt to introduce limited liberalising reforms – proved incapable of reforming itself and was ultimately overthrown on 25 April 1974 (Hammond Reference Hammond1988). Fascist ideology had deeply permeated state institutions, and the fall of the dictatorship is still widely regarded as the most significant event in the country’s modern history (Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira et al. Reference Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira, Raimundo, Flores, Santana Pereira, Heyne, Cabrita, Manucci and Vicente2024). Among the key drivers of the military coup that precipitated this collapse were enduring public discontent with forced labour and the immense economic and human costs of the colonial wars in Portugal’s former African territories (Varela, Simões de Paço, Alcântara et al. Reference Varela, Simões do Paço, Alcântara and Ferreira2015). As the Portuguese Empire disintegrated, calls for decolonisation were accompanied by demands for development and democratisation.

The military forces garnered extraordinary support from civil society during the transition to democracy, making this social revolution a key reference point for historians and political scientists alike (Ramos Pinto Reference Ramos Pinto2013). As Fishman (Reference Fishman2019) put it, ‘[f]rom its first moments, the revolution created new symbols, forms of discourse, understandings, meanings, and practices’ (ibid., p. 46). The revolution liberated people from (self-)imposed privacy and suspicion; outdated institutions were swiftly excluded from the process of change, and marginalised social groups were actively encouraged to take part in the moment of state (re)invention (Hammond Reference Hammond1988). The rapid and complex developments of the ensuing revolutionary period remain, to this day, at the centre of public debate.

Transitioning to democracy in the mid-1970s

The Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas, MFA), composed of veteran captains from the wars in the African colonies, played a pivotal role in the Carnation Revolution. The MFA quickly evolved into the key political force that established the Revolutionary Ongoing Process (Processo Revolucionário em Curso, PREC) between 1974 and 1975. In tandem with the MFA, the Communist Party and far-left groups collaborated in the monumental effort to eliminate the authoritarian legacy from state and society. The introduction of a specific form of council socialism was intended to place civil society at the centre (Costa Pinto, de Sousa and Magalhães et al. Reference Costa Pinto, de Sousa and Magalhães2013). Society welcomed the MFA’s plan to restore civil liberties and implement an economic policy, alongside the nationalisation of banks, insurance companies, and industries. As Bermeo (Reference Bermeo, Collier and Berins Collier1997) observed, there was a strong focus on the working class, with mass mobilisation playing a significant role in the emancipation of society. Progressive urban movements, particularly those involving students (Accornero Reference Accornero2019) and the Catholic Church, also contributed to the democratic transition (Papadogiannis and Ramos Pinto Reference Papadogiannis and Ramos Pinto2023).

As granularly examined by Hammond (Reference Hammond1988), the appropriation of the revolution by civil society laid the basis for what the author calls the ‘popular power model’, one that aimed to expand and deepen political participation for the people. Likewise, García-Espín (Reference García-Espín2025) has recently examined how nonelitist public discussions have significantly influenced historical transitional moments in neighbouring Spain and other regions. The specific type of participatory culture or atmosphere established through targeted mobilisation demonstrates a clear effort to include underrepresented social groups. In Portugal, popular participation was based on the reestablishment of social ownership over neighbourhoods, workplaces, and land.

People self-organised spontaneously at the local level through neighbourhood commissions composed of volunteers and officials appointed by the Ministry of the Interior to manage administration and direct popular participation (Ramos Pinto Reference Ramos Pinto2013; de Almeida Reference Almeida2022). These commissions advocated for stronger social welfare and the collective management of facilities and services, sometimes evolving into formal organisations and housing cooperatives (Ramos Pinto Reference Ramos Pinto2013). By working side by side with the authorities, commissions played a pivotal role in defining housing, water distribution, sewerage, transportation, medical, and childcare support policies (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014). In fact, these commissions were seen as a means of practising direct democracy within a new political system based on collective decision-making and the expansion of individual consciousness. Most commissions were constituted by a first interim group that announced a public meeting in the neighbourhood, followed by the election of members by all residents (Hammond Reference Hammond1988). Initially focussed on immediate necessities and the improvement of housing conditions, many commissions later called for new housing and, in some cases, supported occupations.

In parallel, a key role was played by labour movements, which had contributed to the crisis of state power during the final years of the dictatorial regime and immediately afterwards through strikes and mobilisations (Noronha Reference Noronha2023). During the transition to democracy, factories became key sites of struggle and occupation, supported by newly formed workers’ committees (Pérez Suárez Reference Pérez Suárez, Cabreira and Varela2020). Workers demanded wage increases and pay equalisation between men and women, while officers who had collaborated with the old regime were replaced by workers’ commissions, elected through assemblies that produced ‘notebooks of collective claims’ (cadernos reivindicativos) detailing workers’ grievances (Lima Santos, Pires de Lima and Matias Ferreira Reference Lima Santos, Pires de Lima and Matias Ferreira1977; Hammond Reference Hammond1988). Self-management essentially aimed to preserve jobs and, as Varela and colleagues (Reference Varela, Simões do Paço, Alcântara and Ferreira2015) describe, was tolerated by state actors as a means of supporting countercyclical measures and recovering profits amid the global economic crisis that began in the early 1970s. Above all, the state sought to prevent political unrest by facilitating meetings between workers, emerging unions, and the Ministry of Labour.

The democratic transition also had a profound impact on rural areas, particularly through a sweeping agrarian reform aimed at expropriating large estates and democratising land ownership, especially in the southern regions of the country (de Almeida Reference Almeida2013). In some cases, farmworkers occupied uncultivated land to maintain their employment, eventually leading to the formation of cooperatives managed by elected commissions composed of union members, occupiers, and smallholders (Hammond Reference Hammond1988). Additionally, the self-management of land within specific administrative districts was consolidated in the central and northern regions. The practice of the so-called baldios had largely been discontinued following the 1938 Forestry Population Law, which imposed afforestation on wastelands and ended the collective possession of land (Skulska, Pacheco, Colaço et al. Reference Skulska, Pacheco, Colaço, Sequeira, Rego and Acácio2023). However, in 1976, community lands were returned to local shareholders, encouraging a renewal of rural activities.Footnote 1

Popular participation: SAAL

Under the PREC, a pattern of popular participation emerged in support of regime change. The radical transformation of the state apparatus and the participation it entailed were rooted in civic determination for the collective management of neighbourhoods. One of the most documented forms through which citizens actively engaged in improving living conditions and/or (re)constructing their homes was the Local Ambulatory Support Service (Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local, SAAL). This democratic innovation effectively aligned the state’s response with grassroots activism led by residents to address the lack of social welfare. SAAL was established as a national programme by the Secretary of State for Housing and Urbanism, designed to support residents with the assistance of brigades composed of architects, drafters, social and clerical workers, and students. Neighbourhood commissions were responsible for requesting financial and technical support from the state, often evolving into cooperatives or associations responsible for maintaining housing under collective ownership.

Between 1974 and 1976, approximately 150 SAAL ‘operations’ were carried out across the country. According to Portas (Reference Portas1986), the political leader behind the programme, there was an attempt to provide structured responses while defending citizens’ rights to remain in their communities. As Rodrigues (Reference Rodrigues2015) put it, ‘Revolutionary in spirit, [SAAL] entailed a significant transfer of decision-making and executive power to self-organised neighbours, allowing them to have an effective influence on their own resettlement processes’ (ibid., p. 88). Pereira (Reference Pereira2016) similarly notes that SAAL was part of a broader social transformation, focussing on greater popular power, with the state intending the programme to be fundamentally grassroots in nature. Drago (Reference Drago2024) has recently highlighted the programme’s potential for politicising the urban condition by placing popular organisations at its core.

Despite criticisms regarding its practical contribution to addressing the severe housing shortage in the country (Mota Reference Mota2015), SAAL exemplifies how the state was being structurally (re)imagined at the time. The democratisation of the state and its expertise significantly contributed to the international debate on popular movements and rights (Bandeirinha Reference Bandeirinha2007). Importantly, the active participation of communities was oriented towards a new political model of citizenship (Hammond Reference Hammond1988).

Consolidating democracy in the 1980s and 1990s

The PREC was, and continues to be, a praised and contested phase in Portugal’s democratic history. Countermovements among small farmers in the centre and north of the country, along with the echoes of the global economic crisis and the lack of raw materials from former colonies, ultimately brought the revolutionary period to an end on 25 November 1975. This epilogue demonstrates that, while the main political and military forces were inclined towards the establishment of a socialist regime (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter, O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986), a wide diversity of beliefs about the future of the Portuguese state persisted (Cerezales Reference Cerezales2017). With the suspension of all collective bargaining and the gradual disappearance of most base-level organisations, a Western liberal democracy was eventually established with the support of the Socialist and Social Democratic parties (Costa Pinto Reference Costa Pinto, de Sousa and Magalhães2013).

At this historical juncture, Portugal focussed its efforts on integration into the European Union, whose prospects played a key role in democratic consolidation alongside the adjustment of domestic political forces (Costa Lobo, Costa Pinto, Magalhães et al. Reference Costa Lobo, Costa Pinto and Magalhães2016). Approximately one-third of social welfare entities were established after the fall of the dictatorship in 1974, providing collective responses to the new state’s limited capacity through various cooperation programmes and funding schemes.Footnote 2 The sector was significantly strengthened by the 1983 recognition of new public service providers under the Statute of Private Institutions of Social Solidarity, which formalised their relationship with the state.Footnote 3 According to Fishman (Reference Fishman2019), when the new political formation introduced a constitutional reform at the end of the 1980s, the reprivatisation of nationalised firms marked the definitive shift in the revolution’s social legacy from public ownership of enterprises to the consolidation of the welfare state.

Civil society organisations now emerged as essential interlocutors of the state within a rapidly changing international landscape, which facilitated knowledge transfer and access to funding. The pluralisation of these organisations and the expansion of the third sector were not driven solely by international factors but also by the capacity for civic action demonstrated during the democratic transition (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014). Nevertheless, the repositioning of civil society as a ‘stakeholder’ represented a significant departure from the role it had played during the revolutionary period. Branco (Reference Branco2017) contends that state–private partnerships carry inherent risks, as the creation of privileged and parallel communication channels may increase the likelihood of civil society’s instrumentalisation.

During the 1990s, Portugal embraced the rising enthusiasm for new governance models that placed nonelected, organised actors at the centre of decision-making processes, aiming to reduce the burden on the state (EU 2001). Participation increasingly came to involve associated rather than individual citizens, in line with international trends of professionalisation among practitioners and the consolidation of networks in this field (see also Chilvers Reference Chilvers2008). Similar to neighbouring Spain, state–civil society ties in Portugal may have generated a ‘double asking effect‘, retrofitting benefits for decision-makers and associational members strategically positioned within participatory processes (Navarro and Font Reference Navarro, Font, Geißel and Joas2013).

Within the broader landscape of Western democracies, Portugal benefitted from the growing role of civil society organisations while also undergoing a significant transformation in its sociopolitical fabric. Public dissatisfaction with the political class, coupled with perceptions of widespread corruption, increased sharply (de Sousa, Magalhães and Amaral Reference de Sousa, Magalhães and Amaral2014; de Sousa and Maia Reference de Sousa, Maia, Ferrão and Delicado2017). Santos and Arriscado Nunes (Reference Santos and Arriscado Nunes2004) interpret this trend as a gradual erosion of the revolutionary legacy, which has slowly diminished the intensity of Portuguese democracy.

Stakeholder participation: Local Agendas 21

The consolidation of Portuguese democracy brought to the fore a new pattern of participation that placed civil society organisations centre stage. The engagement of such stakeholders can be exemplified by the “Local Agendas 21”. This was the name given to initiatives by local governments aimed at aligning with the “Global Agenda 21” (UNCED 1992), through the collaboration of public authorities, public and private organisations, as well as citizens. Officially endorsed by the European Union, Local Agendas 21 were designed to empower civil society by providing access to information and inclusion in decision-making processes related to sustainable development. In Portugal, these democratic innovations were integrated into the National Sustainable Development Strategy, helping to translate the 1992 agreement into specific initiatives promoted by local authorities – across the political party spectrum – that were expected to establish participatory forums with stakeholders and appoint working groups responsible for action plans ultimately validated by all participants.

Pinto and colleagues (Reference Pinto, Macedo, Macedo, Almeida and Silva2015) identify three main stages in the dissemination of the Local Agendas 21 in Portugal: first, slow dissemination marked by limited political awareness (1992–2002); second, significant implementation driven by EU funding and agenda transfer (2003–2006); and third, a decline in momentum because of the financial crisis (2007–2011). As Guerra, Schmidt, and Lourenço (Reference Guerra, Schmidt and Lourenço2019) confirm, by 2002, only 1% of Local Agendas had been implemented, although this figure rose sharply in subsequent years, peaking at 47% by 2011. Financial and technical resources played a major role in enabling some municipalities to maintain long-term commitments. However, the debt crisis had a detrimental impact, as evidenced by the drop in numbers and a reduced potential for meaningful participation.

Another factor that may explain the decline of Local Agendas 21 was the emergence of participatory budgeting, which appeared as a ‘more concise, focused, and cheaper’ (Guerra, Schmidt and Lourenço Reference Guerra, Schmidt and Lourenço2019, p. 362) practice offering greater political visibility. This intuition is corroborated by evidence: ‘of the municipalities with a participatory budget, 15% came from a LA21 background, while only 8% were non-LA21 adopters’ (Pinto, Macedo, Macedo et al. Reference Pinto, Macedo, Macedo, Almeida and Silva2015, p. 78). Scholars contend that there was a metamorphosis shaped by prevailing public trends. The dilution of Local Agendas 21 did not, however, diminish the scope of the sustainable development debate, which has remained strong in the country, as evidenced by current efforts to involve communities in shaping local policies.Footnote 4

Expanding democracy from the 2000s onwards

In the last two decades, public perception of corruption has grown considerably, accompanied by increasing feelings that the democratic system is inefficient and unaccountable (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2005). Notwithstanding this, recent signs of increased satisfaction with democracy have revealed emerging trends in political participation, including a significant expansion of the party system on the right (Cancela and Magalhães Reference Cancela and Magalhães2024; Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira et al. Reference Magalhães, Ramos, Madeira, Raimundo, Flores, Santana Pereira, Heyne, Cabrita, Manucci and Vicente2024).

One reason why Portuguese citizens feel detached from political institutions and seek new forms of participation is rooted in deep socioeconomic cleavages, with disparities in public services between rural and urban areas, as well as between coastal regions and the interior (OECD 2023). Cabral (Reference Cabral, Cabral, Vala and Freire2000) argues that the decline in political participation stems from the growing distance between citizens and centres of power, entrenched in socioeconomic divisions and political alienation. On top of this, the 2010s were marked by a severe financial crisis that led Portugal to impose an economic adjustment programme and significant procyclical fiscal consolidation measures, which exacerbated social hardship and further fuelled disaffection with the political class. One consequence was that electoral abstention peaked among those with lower income and education levels (de Sousa and Maia Reference de Sousa, Maia, Ferrão and Delicado2017), while protests and square occupations increased in opposition to austerity measures (Baumgarten Reference Baumgarten2013).

According to Fishman (Reference Fishman2019), protests had positive effects on the political and economic system, demonstrating that openness to social pressure from below is a strong legacy of the revolution. The election of the Socialist Party in 2015, which expressed reluctance to accept external pressures to implement austerity, paved the way for a remarkable economic recovery, driven by booming real estate and tourism sectors in major cities and coastal areas. In recent years, however, serious concerns have emerged regarding the rising cost of living, which has sparked discontent and incentivised social activism around housing rights (Tulumello, Kühne, Frangella et al. Reference Tulumello, Kühne, Frangella, Silva and Falanga2023), as well as environmental and climate justice. In parallel, there has been an increase in the number of citizens reporting collaboration with civil society organisations (Lisi Reference Lisi2022), all of which demonstrates sustained efforts to expand democracy through multiple practices beyond the political party system.

Overall, while Portuguese democracy remains robust according to international evaluators,Footnote 5 the decline in political participation and citizen engagement raises concerns (Costa Lobo, Costa Pinto, Magalhães et al. Reference Costa Lobo, Costa Pinto and Magalhães2016). The OECD (2023) recently noted that a limited culture of participation and a persistent divide between citizens and public institutions may hinder efforts to sustain and diversify democratic innovations. To contrast these trends, some practices of community participation have drawn on the values of political inclusion that characterised popular engagement during the revolutionary period, alongside the role of civil society organisations that emerged during the 1980s and 1990s. In parallel, individual participation based on one-to-one interaction with public authorities has become dominant through participatory budgeting and is beginning to incorporate deliberative principles as citizens’ assemblies start to spread.

Community participation: Participatory urban regeneration

The right to participate in spatial planning, guaranteed by Article 65 of the Portuguese constitution, reflects the importance of local self-government and community involvement in economic, social, and territorial transformation, a legacy preserved since the revolution (Campos and Ferrão Reference Campos and Ferrão2015). Additionally, and in line with goals of local development, citizens have had opportunities to engage in the regeneration of critical urban areas through state programmes at national and local levels.

A notable example of this type of democratic innovation is the ‘Critical Neighbourhoods Initiative’ (CBI), launched in 2005 and officially closed in 2012, where local community engagement was driven by an integrated approach in three neighbourhoods within the Lisbon and Porto metropolitan areas (Ferrão Reference Ferrão2010). Inspired by the community engagement aspirations of SAAL, the CBI helped transpose participatory values into other policy programmes, such as the local BipZip programme (an acronym for priority intervention zones), launched in Lisbon in 2011, and the ‘Healthy Neighbourhoods Programme’, launched in 2020 by the central government. Both initiatives have been based on funding schemes for local partnerships among civil society organisations. The former has funded partnerships in specific urban areas to develop solutions to socioeconomic, urban, and environmental challenges (Falanga Reference Falanga2020). The latter aimed to build on and scale up the knowledge generated, and mechanisms promoted by BipZip, to support local communities and the third sector across the country.Footnote 6

Citizen participation: Participatory budgeting

A second exemplary democratic innovation promoted over the last two decades is participatory budgeting, which aims to give citizens a voice in the allocation of a portion of the public budget (Cabannes Reference Cabannes2004). In this practice, citizens are invited to participate in open meetings and submit their proposals, which are then publicly voted on. In Portugal, participatory budgeting began to spread in the early 2000s, inspired by pioneering practices in Brazil (Avritzer Reference Avritzer2006). As Falanga and Lüchmann (Reference Falanga and Lüchmann2020) point out, the primary goal has been to restore citizens’ confidence in democratic institutions. It has been primarily driven by political leaders on the left of the political party spectrum, with the support of the third sector and academia, but with limited involvement from social groups and movements, reflecting general trends in southern Europe (Font, della Porta and Sintome Reference Font, della Porta and Sintomer2014).

According to Bogo and Falanga (Reference Bogo and Falanga2024), participatory budgeting in Portugal has become highly diversified across territorial and thematic areas, as well as levels of governance and political affiliations. Despite this diversity, however, participatory budgeting has faced criticism for its limited impact on social and political change. Looking back at its fluctuations, the absence of a regulatory framework has made participatory budgeting highly dependent on electoral cycles and the political agendas of elected governments (Alves and Allegretti Reference Alves and Allegretti2012). Falanga and Ganuza (Reference Falanga and Ganuza2025) recently criticised the limited presence of participatory budgets on the political agenda, adding to concerns about the weak integration of such processes within the administrative apparatus and the scant interest in evaluating policy outcomes. Despite its wide dissemination, the International Budget Partnership has raised some concerns on the small budget allocation dedicated to participation and the limited opportunities available to monitor the implementation of proposals (OECD 2023).

Citizen participation: Citizens’ assemblies

Finally, while the dissemination of deliberative practices has been relatively limited compared with other Western and neighbouring countries, it is worth noting the recent implementation of local citizens’ assemblies, a specific form of deliberative minipublic. Notable examples include the development of the Citizens’ Council in Lisbon from 2022, promoted by a right-wing coalition (Falanga Reference Falanga, Carmelo, Pimenta, de Lima and Hanenberg2023), and the implementation of a local climate assembly in Vila Franca de Xira, a small city in the Lisbon region governed by the Socialist Party.Footnote 7 Moreover, the adoption of deliberative mechanisms in other policy processes, such as the sustainable mobility plan of the Lisbon metropolitan area,Footnote 8 may signal an emerging trend aligned with the so-called deliberative wave (OECD 2020). What these practices have in common is the random selection of relatively small samples of participants, aimed at fostering in-depth discussion and enhancing citizens’ thoughtfulness regarding specific policy issues, ranging from climate change to local service provision and welfare.

Discussion

In a relatively short period, Portugal transitioned from dictatorship to democracy through a revolution that challenged authoritarian hierarchies and called for a politically inclusive path to democracy. In the years that followed, the adoption of liberal democracy within a rapidly changing international context contributed to a repositioning of Portugal among Western consolidated democracies. During this time, civil society organisations became key stakeholders of the state in the provision of public services. More recently, efforts to expand democracy through multiple channels of participation have built on a diversification of participatory patterns (see Table 1). The genetic approach proposed by Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977; Reference Bourdieu, Champagne, Lenoir, Poupeau, Rivière and Fernbach2024) enables an exploration of state–society relations as a key layer shaping the meanings and forms of participation embodied in democratic innovations, thereby revealing differences and similarities across historical stages that help to unpack the legacy of the revolution.

In the aftermath of the revolution, democratic innovations claimed civic rights and liberties previously repressed by the dictatorial regime. Popular participation during the revolutionary period demonstrated the unprecedented capacity of civil society for self-organisation and the strong convergence between institutional and social actors around socialist-oriented values (Costa Pinto Reference Costa Pinto2006; Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014). As Fishman (Reference Fishman2011; Reference Fishman2019) contends, openness in communication and education systems, as well as the permeability of institutions to powerless voices, are evidence of the inclusive ethos imprinted during those years. Other scholars are more sceptical, arguing that the rapid political turn and the establishment of a Western liberal democracy probably provoked widespread disillusionment, eventually helping to explain the current decline in political participation (Ramos Pinto Reference Ramos Pinto2013).

From the 1980s and 1990s onwards, citizen disaffection with democracy became more evident (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2005). After the attempt to place popular participation at the heart of a new political structure, as demonstrated by SAAL, Portugal repositioned civil society within new state–private collaborations. During those years, intermediated state–society relations for the welfare system were crafted and reflected in associative forms of participation reliant on active civil society (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2014), yet disclosing risks of state co-optation (Branco Reference Branco2017). By bringing the international debate on sustainable development to the domestic political forefront, Local Agendas 21 provided an opportunity to experiment with new arrangements for participation that privileged interlocution with civil society organisations. Unequal resource allocation and the risks of elite capture, along with the negative effects of the financial crisis, eventually had a negative impact on this practice (Guerra, Schmidt and Lourenço Reference Guerra, Schmidt and Lourenço2019). Interestingly, however, scholars comment on the metamorphosis of Local Agendas 21 into new local efforts (Pinto, Macedo, Macedo et al. Reference Pinto, Macedo, Macedo, Almeida and Silva2015).

Table 1. Historical stages, patterns of participation and democratic innovations in Portugal

Source: author’s own work.

From the 2000s onwards, the rise of nonorganised citizen participation took centre stage with participatory budgets. In light of the sharp decline in citizen affection towards democratic institutions (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2005), this practice was seen as a possible means to restore trust in constituencies (Falanga and Lüchmann Reference Falanga and Lüchmann2020). Risks of self-selected participation – where citizens in more privileged positions are more likely to take part – have motivated the parallel implementation of community participation programmes, thus reviving issues of political inclusion and fleshing out the role of the third sector, as well as the gradual emergence of alternative recruitment techniques based on random selection within citizens’ assemblies. Time will tell whether deliberative minipublics will pave new ways of understanding political inclusion for future developments in the country.

By situating democratic innovations historically within specific patterns of participation, this paper has delved into structural changes in state–society relations (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977; Reference Bourdieu, Champagne, Lenoir, Poupeau, Rivière and Fernbach2024). While the practices presented in this paper have pursued the overarching goal of making political engagement more inclusive (Pateman Reference Pateman1970; Barber Reference Barber1984; Habermas Reference Habermas1992) and of (re)imagining the role of society (Smith Reference Smith2009; Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019) to improve democracy (Newton and Geißel Reference Newton and Geißel2012; Warren Reference Warren2017), they also demonstrate that there is no single, all-inclusive underpinning ethos imprinted by the revolution. Essential in the inscription of social democratic values, the revolution should not be considered the sole inspiration for democratic innovations. Such an interpretation would underestimate the highly complex field of international and domestic forces at play that have redefined state–society relations and political participation. The succession of different patterns of participation reflects the shift from popular demand for participation to a more sophisticated set of democratic innovations, more often than not promoted by the state.

Therefore, rather than being understood as ‘children of the revolution’, democratic innovations in Portugal are ‘children of their time’. They demonstrate the capacity to respond, not without controversy, to the challenges and political aspirations of specific moments in history, as well as the capacity to learn from the past and adapt lessons under new guises.

Concluding remarks

This paper aims to situate Portuguese democratic innovations within three main historical stages to explore the legacy of the revolution over time. The country provides a particularly valuable case study, offering an in-depth examination of the relatively short period from the establishment of democracy in the mid-1970s to the present. Accordingly, the main contributions of this paper can be summarised as follows:

First, it offers theoretical and empirical insights into the interconnected and evolving nature of democracy and democratic innovations. Neither democracy nor democratic innovations reproduce themselves unchanged over time; rather, they evolve in ways that can be better understood by situating specific fields of practice within their historical contexts.

Second, closely related to the first point, the changes observed through democratic innovations have been shaped by distinct patterns of participation, influenced by varying state–society relations. The interplay of international and domestic forces in the design and implementation of democratic innovations is a central aspect of their development.

Third, the context-specific nature of emerging patterns of participation allows for a longitudinal appreciation of democratic innovations, acknowledging the potential for learnings from the past to remain latent and reemerge at different times in history, thus requiring an examination beyond siloed frameworks.

The main limitation of this paper lies in the scarcity of documentation on democratic innovations in Portugal, which significantly hinders further in-depth investigation. Despite some efforts by public authorities and organisations to provide accessible information, future research would benefit from a more robust set of primary data. While this paper contributes to a critical reflection on democratic innovations in Portugal, several questions remain open and warrant further inquiry. Among other questions, data should offer a realistic picture of the contribution made by democratic innovations to mainstream mechanisms of representative democracy, as well as the magnitude and reach of participants within the electorate, to elucidate their actual role in promoting political inclusion. Therefore, it is hoped that the insights provided here will support continued exploration of the trajectories of democratic innovations in Portugal, and beyond.

Funding statement

Horizon Europe grant agreement 101094258.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.