Introduction

America is secularizing. By 2040 the majority of Americans will identify not with a centuries old religious tradition but none at all (Nadeem Reference Nadeem2022). Furthermore, the decline in religious identification is not confined to any one group (St Sume and Wong Reference Sume and Janelle2022).Footnote 1 Across racial and ethnic backgrounds, a new multiracial and intersectional secular America is emerging. The sheer number of Americans who identify as nonreligious justifies renewed study of the group’s political beliefs and cleavages. The group’s diversity points to an intersectional approach and existing work on racial distinctions among the nonreligious (St Sume and Wong Reference Sume and Janelle2022) bolster the case.

Importantly, the newly ascendant nonreligious demographic has grown rapidly through widespread disaffiliation from Christianity. For decades, churches have been emptying out as congregants disaffiliate from religious institutions and beliefs. However, because disaffiliation has been taking place for many decades, there are now tens of millions of multi-generational nonreligious Americans whose parents or even grandparents were also nonreligious. Yet each year there are also still millions leaving religion and become newly nonreligious. Sustained disaffiliation has thus created a division in the nonreligious community between those who were never affiliated with any religious tradition and those who have left religion behind as adolescents or adults. This paper examines divergent political attitudes between Americans who have left Christian traditions and those raised nonreligious intersectionaly across racial groups.Footnote 2

The distinction between the never affiliated and the disaffiliated has been labeled “nones” vs “dones” in psychology and sociology literature (Schwadel et al. Reference Schwadel2021). Furthermore, the lingering effects of religious identification on behavior among religious dones has been dubbed religious residue. Such residual effects have been found to influence implicit and explicit feelings towards deities (Van Tongeren et al. Reference Van Tongeren2021), scores on Haidt’s moral foundations (Schwadel et al. Reference Schwadel2021), and even some consumer decisions (Van Tongeren, DeWall, and Van Cappellen Reference Van Tongeren, Nathan DeWall and Van Cappellen2023). Most relevant to this paper is the finding that dones experience higher levels of social alienation and exhibit higher levels of identity concealment than lifelong nonbelievers (Mackey et al. Reference Mackey2021; Mackey, Van Tongeren, and Rios Reference Mackey, Van Tongeren and Rios2023).

However, less attention has been given to examining distinctions in political and policy attitudes between nones and dones. This paper examines the politically relevant differences between those who are lifelong nonbelievers and those who disaffiliated from Christianity.Footnote 3 Furthermore, we examine distinctions across intersectional lines. Drawing on data from the 2020 wave of the Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), which surveyed 17556 respondents between April 2 and October 2, 2021, we focus on the 3594 individuals who identified as “atheist,” “agnostic,” or “none.” We document divergent attitudes across a set of social justice related policy issues and find that disaffiliated nonbelievers are more likely to support left wing policies, identify as highly liberal, and are generally more left wing in their political preferences. Then, we propose and present preliminary evidence suggesting that social identity threat and negative associations with conservative religion driven beliefs might be the forces driving disaffiliated nonreligious Americans further left than lifelong nonbelievers. The proposed theory builds on existing work that suggests religious organizations association with right wing politics has driven believers with left wing beliefs away from both religion and right-wing politics (Baker and Smith Reference Baker and Smith2015; Braunstein Reference Braunstein2022; Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018; Vargas Reference Vargas2012). Finally, we examine our findings intersectionaly across racial groups to determine how race interacts with the nones vs dones cleavage. Here we find that White, Black, and Latino religious dones are significantly less likely to endorse conservative positions conditional on perceiving conservative Christianity as threatening. Whereas, our results for Asian religious dones are directionally consistent with our hypothesis but insignificant, likely due to a low sample size for Asian religious dones. Importantly, our findings are not causal and we do not claim to show that differences in attitudes are caused by identity threat. Rather, we present preliminary findings that suggest a promising path for future work.

Nones, Dones, and the Social Identity of Religion

As research on nonreligious individuals has grown (Smith and Cragun Reference Smith and Cragun2019) a significant body of work examining the differences between formerly religious members of the nonreligious community and lifelong nonbelievers has been published. This work has largely taken place in psychology but is not absent in sociology and anthropology. Researchers have coined the term religious “dones” for those who have disaffiliated and “nones” for those who have never had a religious affiliation (Van Tongeren et al. Reference Van Tongeren2021). The literature has identified residual effects of religious identification on variables such as implicit and explicit feelings towards deities (Van Tongeren et al. Reference Van Tongeren2021), scores on Haidt’s moral foundations (Schwadel et al. Reference Schwadel2021), and consumer decisions (Van Tongeren, DeWall, and Van Cappellen Reference Van Tongeren, Nathan DeWall and Van Cappellen2023).

Tongeren et al. (Reference Van Tongeren, Nathan DeWall and Van Cappellen2023) examine currently religious, former, and never religious. They find that former religious identifiers differed from the never religious and currently religious in cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes such as prosocial behavior (charitable donations and a self-rated measure). They find religious individuals are the most pro social, former members retain some of the prosociality associated with religion and never religious respondents have the lowest prosocial ratings (Van Tongeren, DeWall, and Van Cappellen Reference Van Tongeren, Nathan DeWall and Van Cappellen2023).

Most important to this paper is the work examining identity threat among the nonreligious. Newer work in this area examines the degree to which concealment is affected by the distinction between nones and dones (Mackey et al. Reference Mackey2021; Mackey, Van Tongeren, and Rios Reference Mackey, Van Tongeren and Rios2023). This research points to a potential causal explanation for divergent ideology and political expressions between the nones and the dones: Identity Threat. Former Christian identifiers experience social alienation, a loss of belonging, and often feel the need to conceal their nonreligious identity at far greater rates than religious nones (Mackey et al. Reference Mackey2021; Mackey, Van Tongeren, and Rios Reference Mackey, Van Tongeren and Rios2023). We propose that this social pain alongside Christianity’s association with right wing politics drives former identifiers to left wing identification and beliefs. A Potential Mechanism of Disaffiliation and Political Ideology

Key to our theory are the forces driving Americans away from religious beliefs and institutions. Scholars have proposed many reasons for the rapid and sustained losses religious institutions have suffered. First and oldest is secularization theory, which posits that modernization should necessarily make religion irrelevant and thus disappear (Latré, and Vanheeswijck Reference Latré, Vanheeswijck and James2015). A second explanation posited is that the systematic enabling of and concerted efforts to cover up decades of appalling sexual abuses by religious leaders and institutions has driven Americans away from religious identity (Ballard Reference Ballard2023).

However, a third theory of disaffiliation is both the most referenced and the most relevant to our findings. Scholars such as Hout and Fisher (Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Reference Hout and Fischer2014), Evans (Evans Reference Evans2016), and (Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018) have proposed the Christian Right’s prominent involvement in politics as an explanation for American’s disaffiliation from religion generally. The association of religious belief and institutions with right wing political ideology, beliefs, policy, and movements as a driving force behind disaffiliation has widespread support in the literature (Baker and Smith Reference Baker and Smith2015; Braunstein Reference Braunstein2022; Campbell, Layman, and Green Reference Campbell, Layman and Green2020; Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018; Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Margolis Reference Margolis2018; Vargas Reference Vargas2012). This work has found that disaffiliation increases in states where religious institutions involve themselves in politics (Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018). In particular, more visible Christian Right activism is associated with increased identification as nonreligious. Furthermore, the effects appear to be linked to issue specific disagreements such as same sex marriage wherein the involvement of religion in politics produces not just organized opposition to conservative positions, but disaffiliation from religion (Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018). Moreover, this effect is likely to function across intersectional lines such as race. In light of this work the meteoric increase in nonreligious identification can be seen as a reaction to the right-wing politics of many Christian denominations in the United States. In other words, disaffiliation may be a backlash that also pushes dones further left ideologically than nones.

This theory fits well with findings in psychology that religious dones experience social alienation from their previous faith and higher levels of social identity threat from religion (Mackey et al. Reference Mackey2021; Mackey, Van Tongeren, and Rios Reference Mackey, Van Tongeren and Rios2023). If religious dones’ primary reason for disaffiliation is related to politics and they perceive religion as threatening, we should expect them to have distinct political views from religious nones. Theoretically, the perception of conservative religion as threatening would be driving a backlash that leads to disaffiliation and left-wing beliefs. Consequently, disaffiliation driven by religious institutions’ association with right wing politics generates our expectation that dones will take more progressive attitudes across a set of social justice policies and positions as well as have increased opposition to reactionary policies. Stated formally here:

H1 Nonreligious American’s raised in religious households will hold policy and ideological views further to the left than nonreligious American’s raised in nonreligious households.

H2 Perception of religious conservatism as threatening will moderate the relationship between nonreligious American’s upbringing and their policy and ideological views, such that higher perception of threat will increase the strength of the relationship.

Dataset and Measures

To examine the political differences between religious nones and dones, we draw upon the 2020 wave of the Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS). The CMPS 2020 includes 17,556 respondents who were surveyed between April 2 and October 2, 2021. For our analysis, we focus on the 3,594 respondents who answered the question, “When it comes to religion, do you consider yourself to be…” with “atheist,” “agnostic,” or “none.” The CMPS offers distinct advantages for our study. It includes items on both past and current religious affiliation, perceived threats posed by conservative Christians, and views on key ideological and policy issues, while also allowing for analysis across racial and ethnic groups. Crucially, no other existing dataset includes the combination of variables necessary to address our two central research questions:Footnote 4 (1) Does the religious past of nonreligious individuals shape their ideological positions? and (2) Do perceptions of threat from conservative Christians mediate that relationship?

Explanatory and Moderating Variables

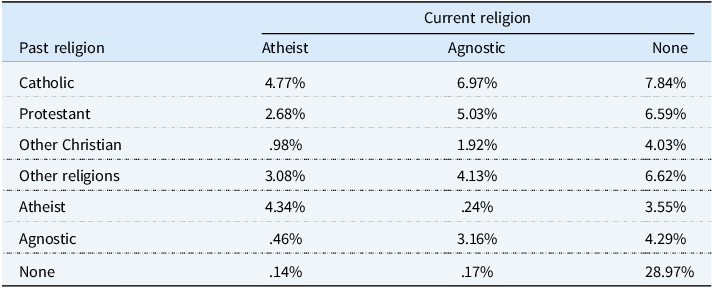

Table 1 presents the previous religious affiliations of nonreligious individuals. Our main explanatory variable is respondents’ past religious affiliation. To identify nonreligious individuals with religious backgrounds, we first generated a religion variable based on sixteen subcategories in the dataset. Respondents were asked, “When it comes to religion, do you consider yourself to be?” Those who selected “atheist,” “agnostic,” or “none” were grouped together and categorized as “nonreligious.”

Table 1. Past religious affiliation among nonreligious respondents (CMPS Sample)

We then created a variable capturing past religious affiliation based on responses to the question, “What primary religion, if any, did your family practice or follow when you were raised?” Using this information, we divided nonreligious individuals into two groups: those with a religious upbringing and those without. The first group, referred to as “dones,” includes nonreligious individuals who were raised in a Christian tradition. We only focus on Christian past because nearly 41% of nonreligious respondents reported that they have been raised in a Christian household, as shown in Table 1. The second group, referred to as “nones,” includes respondents who are nonreligious and were not raised in any religious tradition (45%).

To explore a possible explanation for differences in policy attitudes between nones and dones, we examine perceptions of threat as a moderating variable. We use a measure from the CMPS that asks respondents to evaluate whether various groups are supportive of or threatening to their vision of American society. Responses range from 1 (“strongly supports”) to 7 (“strongly threatens”), with higher scores indicating a greater perceived threat. We focus on respondents’ evaluations of conservative Christians, based on the premise that perceived threat linked to this group may shape the political attitudes of nonreligious individuals, particularly in distinguishing dones from nones. Finally, we accounted for several control variables, including gender, education, age, income, political affiliation, and race (White, Black, Latino, Asian, Other).

Outcome Variables

We constructed our dependent variables using a set of questions related to support for or opposition to socially and politically contested issues. First, we measured support for voting rightsFootnote 5 using the question: “Do you think the Voting Rights Act is necessary today to make sure that Blacks are allowed to vote, or do you think the Voting Rights Act is no longer necessary?” Respondents selected either “necessary today” or “no longer necessary.”

Next, we assessed attitudes toward immigration policies enacted under the Trump administration, particularly regarding the deportation and detention of asylum seekers. Respondents indicated whether they supported or opposed these policies.Footnote 6 Both the voting rights and immigration items were coded as binary variables.

We also evaluated support for abortion rights and criminal justice reform using reverse-coded 5-point Likert scale items, where higher values reflect stronger support for more liberal positions. Support for abortion rights was measured using respondents’ level of agreement with the statement, “Abortion should remain a legal option in the United States.” Support for criminal justice reform was assessed using the statement, “Law enforcement and the criminal justice system need to be completely reformed.”

Additionally, to measure attitudes toward same-sex marriage, we included a question asking respondents to indicate whether this issue should be a high or low priority for their communities, measured on a 4-point scale. To facilitate interpretability and comparability across outcomes, all variables were standardized to a 0–1 scale. Finally, we used the standard ideology scale included in the CMPS and recoded it as a conservatism scale, where higher values indicate more conservative ideological self-placement.

Results

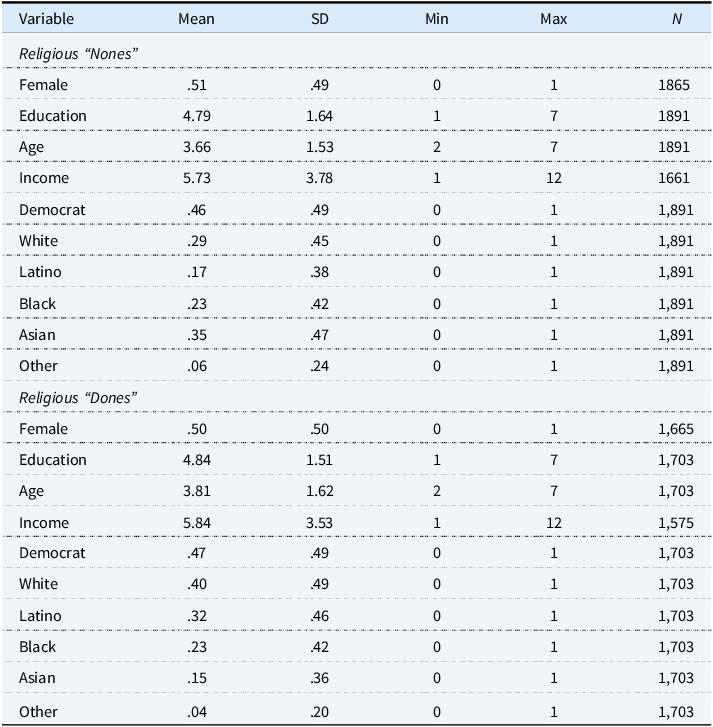

The results presented in Table 2 compare the demographic characteristics of nonreligious individuals with a religious past (“dones”) and those with no religious past (“nones”). Both groups display a balanced gender distribution, with roughly equal proportions of male and female respondents. The analysis reveals that nones and dones share similar demographic profiles: most have at least some college education, are typically between 30 and 39 years old, and report low-income status. Notably, 46–47% of individuals in both groups identified their political affiliation as Democrat.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for nonreligious respondents

Racial distribution is a particularly important aspect of the analysis, given that the sample is not nationally representative and we also elaborate on intersectional effect of race and ethnicity. As shown in Table 2, nones are most likely to identify as Asian (35%), followed by White (29%), Black (23%), Latino (17%), and other racial backgrounds (6%). In contrast, dones are more likely to identify as White (40%), followed by Latino (32%), Black (23%), Asian (15%), and other racial categories (4%).Footnote 7

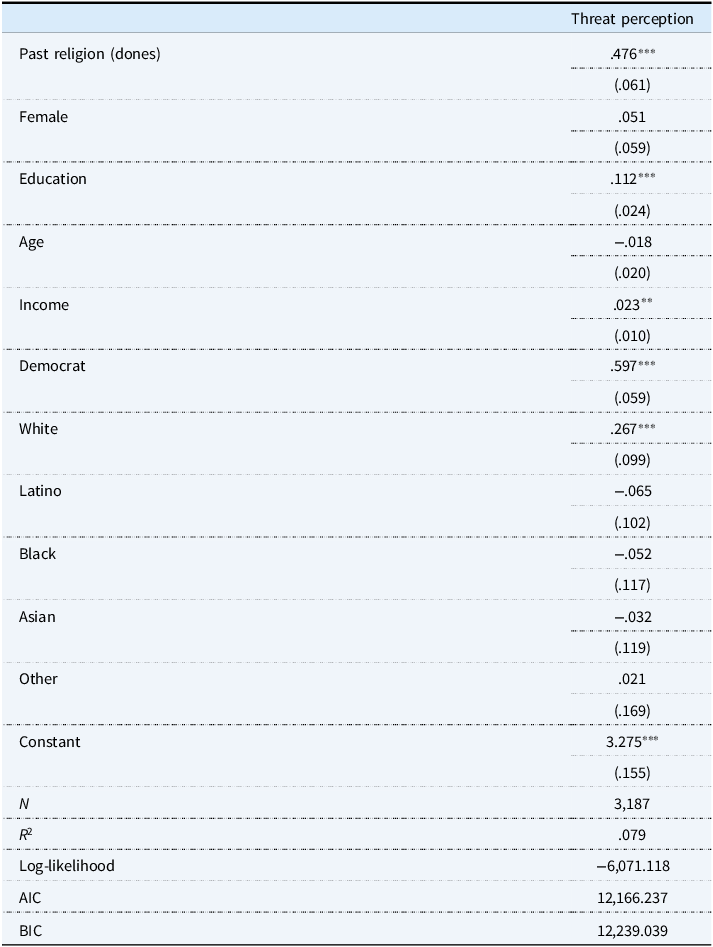

We next assess whether the religious past of nonreligious individuals influences how they perceive conservative Christian groups. As shown in Table 3, nonreligious respondents who were previously affiliated with Christianity are more likely to view conservative Christians as a threat to American society.

Table 3. Predicting perceived conservative Christian threat by past religion

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

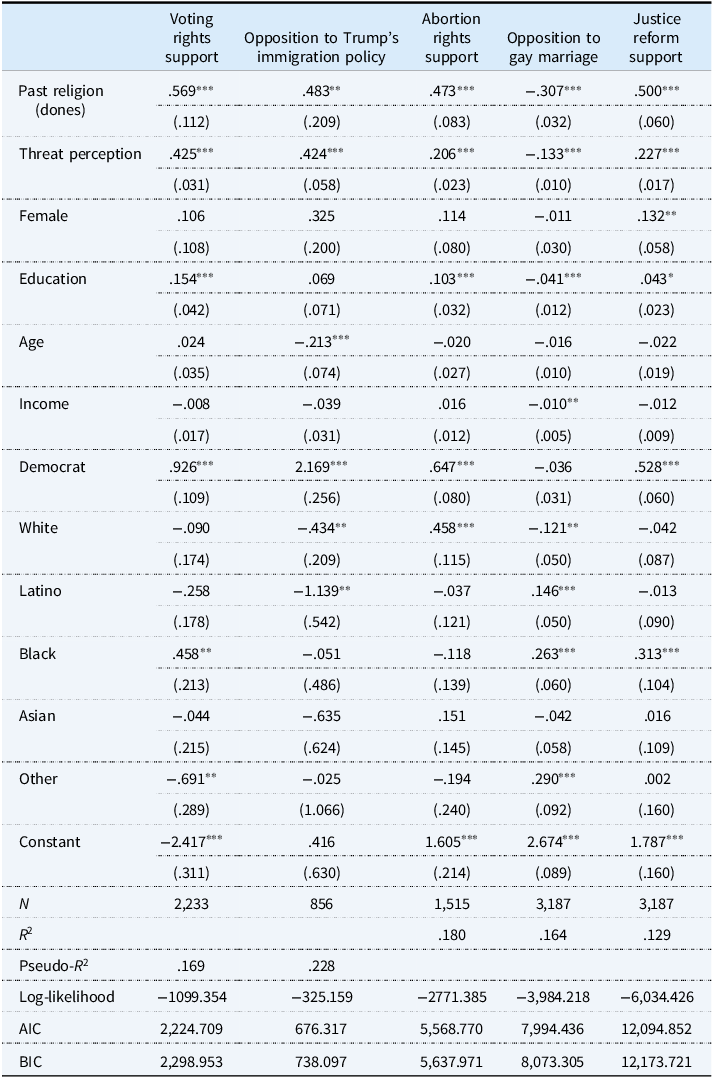

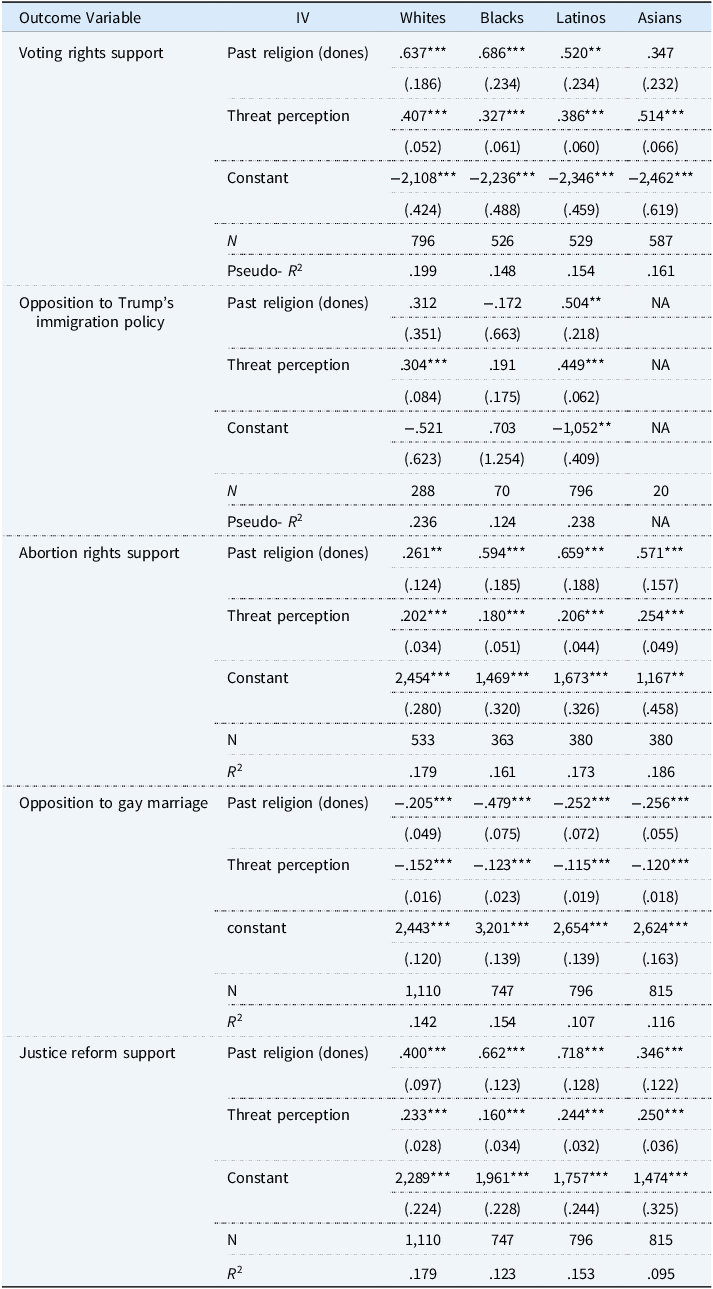

We then test how the religious past of nonreligious individuals shapes their attitudes toward salient ideological issues in U.S. politics. Table 4 presents robust logistic regression estimates for support of voting rights and opposition to Trump’s immigration policies. The findings indicate that nonreligious individuals with a religious past (“dones”) are more likely to support the Voting Rights Act and to oppose restrictive immigration measures.

Table 4. Predicting policy attitudes by past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

Table 4 also includes robust OLS estimates examining the relationship between the religious past and threat perceptions, and a range of policy preferences. Our findings provide evidence that a having Christian past is positively associated with support for abortion rights and criminal justice reform among nonreligious respondents. In addition, identifying as a religious done is a negative and statistically significant predictor of considering same-sex marriage as a societal issue. Taken together, these findings indicate that individuals who identify as religious “dones” exhibit more liberal tendencies regarding contentious policy issues.

Other respondent characteristics also shape variation in policy preferences on these contentious issues. Education consistently predicts support for liberal positions across most domains, although its association with opposition to Trump’s immigration policies is not statistically significant. Table 4 further shows that identifying as a Democrat significantly increases the likelihood of supporting liberal positions on voting rights, immigration, abortion rights, and criminal justice reform.

Racial and ethnic identity demonstrate nuanced effects on ideological policy preferences. White respondents are more likely to support abortion rights and same-sex marriage but also more likely to endorse Trump’s immigration policies. Surprisingly, Latino respondents exhibit comparatively higher support for restrictive immigration policies and opposition to same-sex marriage, suggesting more conservative leanings. Black respondents tend to support voting rights and justice reform, but are also more likely to oppose same-sex marriage.

While the previous analyses included race and ethnicity as control variables, the next section examines these characteristics through the lens of intersectional identities. This approach offers a more nuanced understanding of how intersectional identities jointly shape political attitudes.

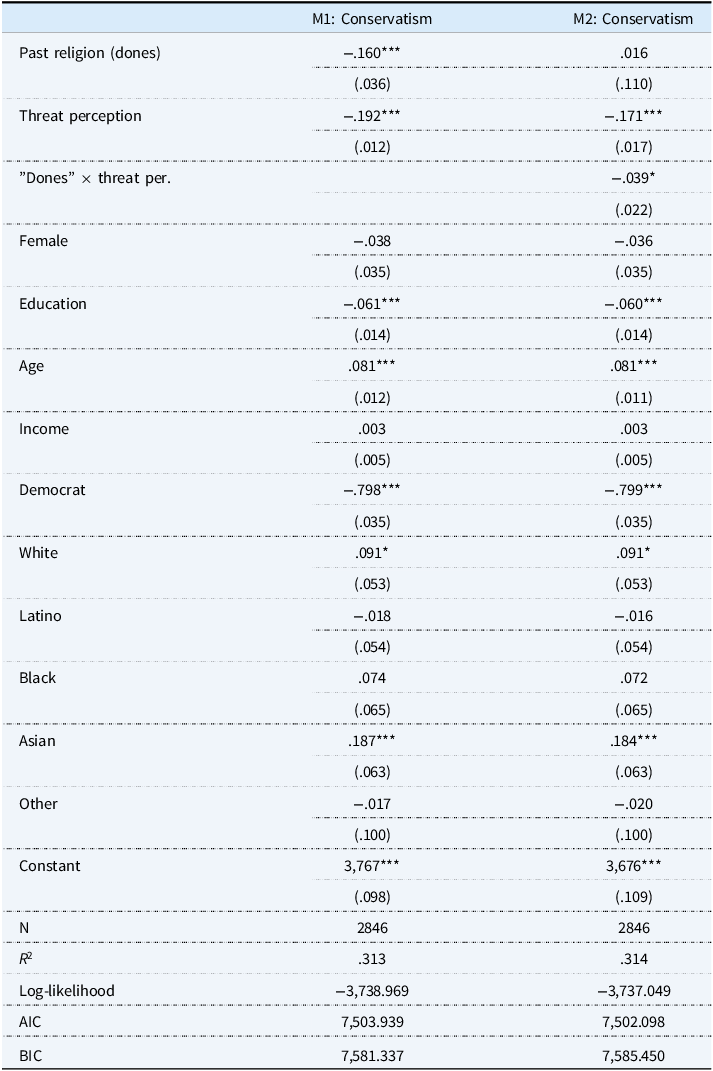

Finally, we examine how the overall level of conservatism among nonreligious individuals is predicted by their religious past, conditional on their perceived threat linked to conservative Christians. Table 5 presents robust OLS estimates showing that both religious past and perceived threat are negatively and significantly associated with conservatism (Model 1). This suggests that nonreligious individuals with a Christian past, as well as those who perceive conservative Christians as more threatening, are less likely to identify with conservative ideological positions. See appendix items A1–A5 for aditional model specifications.

Table 5. Predicting conservatism by past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

However, in Model 2—where the interaction between religious past and threat perception is explicitly modeled—the main effect of religious past is no longer statistically significant. This indicates that, in the absence of threat perception (i.e., when perceived threat is zero), being a religious “done” is not significantly associated with conservatism. In contrast, the main effect of threat perception remains negative and significant among respondents without a religious past (i.e., when Past Religion = 0).

Crucially, the coefficient for the interaction term is negative and statistically significant, providing evidence of conditionality. This indicates that perceived threat modifies the effect of religious past on conservatism, and conversely, that religious past modifies the effect of perceived threat. In other words, the relationship between religious past and ideological conservatism varies depending on levels of perceived threat linked to conservative Christians.

More specifically, Figure 1 indicates that for nonreligious individuals, their religious past does not significantly predict their level of conservatism when perceived threat associated with conservative Christians is low. However, as threat perception increases, religious dones become distinguishable from religious nones, showing significantly lower levels of conservatism. Furthermore, the marginal effects illustrated in Figure 2 clarify this relationship, indicating that differences in conservatism between these groups become apparent when perceptions of threat exceed a score of three.

Figure 1. The interactive effect of past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat on conservatism.

Figure 2. The marginal effect of past religion on conservatism across levels of perceived conservative Christian threat.

Intersectional Identities: Religious Past and Racial and Ethnic Identities

While the previous results indicate that both religious past and perceived threat linked to conservative Christians significantly predict how nonreligious individuals approach controversial policy issues, we also aim to assess whether these patterns hold across subgroups within this population. Racial and ethnic identity is another salient identity in the United States, frequently shaping political attitudes and behavior. One of the key strengths of the CMPS is its ability to provide high-quality data on diverse racial and ethnic groups, allowing us to explore how the intersection of religious past and racial/ethnic identity influences policy preferences among nonreligious individuals. Given the available sample sizes, our analysis focuses on four major racial and ethnic groups in the United States.: Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians.

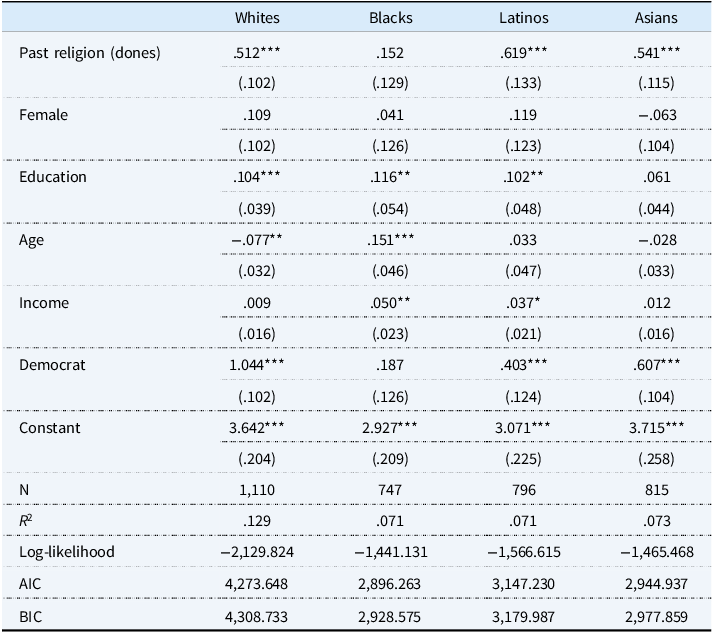

Before turning to the evaluation of outcome variables, we first examine whether the effect of religious past on perceived threat posed by conservative Christians varies across racial and ethnic groups. Table 6 shows that identifying as a religious “done” is positively associated with higher levels of threat perception among all groups except Black respondents. Among Whites, both higher education and Democratic Party affiliation are positively associated with threat perception, while age is negatively associated, suggesting that older White respondents are less likely to perceive conservative Christians as a threat.

Table 6. Predicting perceived conservative Christian threat by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

For Black respondents, higher levels of education, income, and age are all positively associated with perceived threat, indicating a different pattern from Whites. Among Latino respondents, both education and Democratic affiliation predict greater threat perception. In contrast, among Asian nonreligious individuals, the only significant predictor of threat perception, aside from religious past, is Democratic Party affiliation.

Table 7 demonstrates that both being a religious “done” and perceiving conservative Christians as a threat are important predictors of support for voting rights across all racial and ethnic groups. Although the effect of religious past for Asian nonreligious individuals does not reach statistical significance (p = .13), the estimated effect is substantively meaningful and aligns with the liberal positions that Asian religious dones show on other policy issues. We also assess whether the previously observed effects of religious past and threat perception on opposition to conservative immigration policies under the Trump administration hold across racial and ethnic subgroups. Due to limited sample size, Asian respondents were omitted from this analysis.Footnote 8 Robust logistic regression results indicate that nonreligious Latinos raised in Christian households are more likely to oppose Trump-era immigration policies. The results are statistically significant only for religious dones with Latino backgrounds. Although white religious dones show a similar pattern of support, the association does not reach statistical significance, possibly due to limited sample size. The number of Black respondents is also very small because of subsampling within a subset of the sample, leading to low statistical power and likely causing null results.

Table 7. Predicting policy attitudes by past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat, by racial and ethnic subgroups

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses. Full models are presented in the appendix.

While findings for immigration policy are not strong across groups, the effects of religious past and threat perception are more consistent for other contested issues, including abortion rights, same-sex marriage, and criminal justice reform. Across all racial and ethnic subgroups, both being a religious “done” and perceiving conservative Christians as a threat are positively associated with support for abortion rights. Moreover, nonreligious individuals in all groups maintain liberal positions on same-sex marriage and justice reform. Specifically, both religious past and threat perception are negatively associated with opposition to same-sex marriage and positively associated with support for criminal justice reform across all racial and ethnic groups.

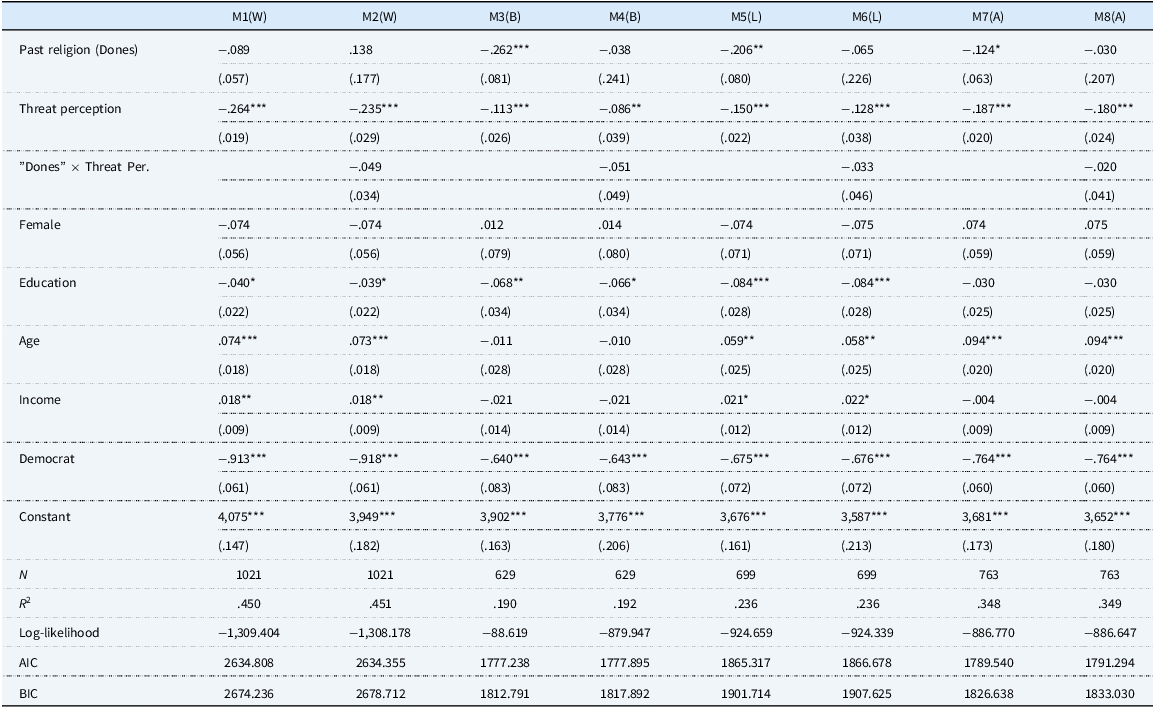

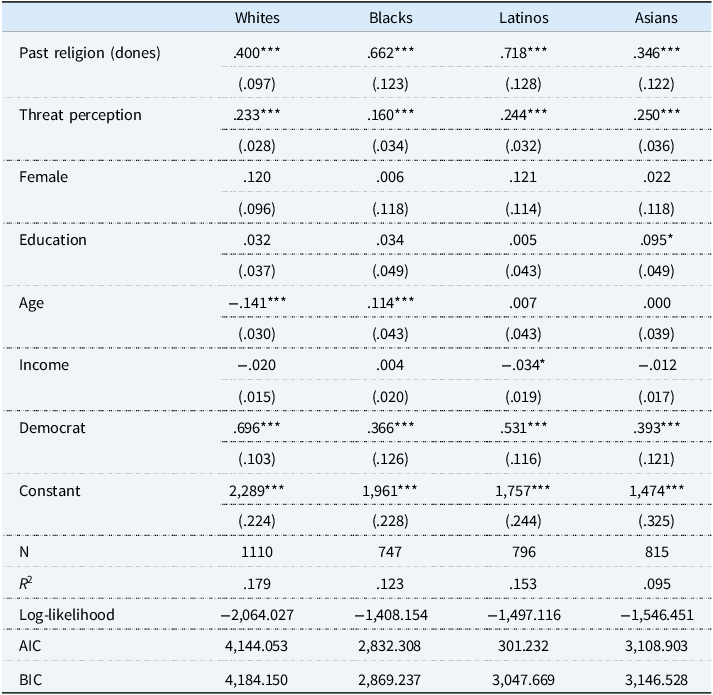

Finally, we assess how conservatism among nonreligious individuals is predicted by their religious past, conditional on perceived threat linked to conservative Christians, across racial and ethnic groups. Table 8 presents OLS estimates for each group, including models with main effects and interaction terms.

Table 8. Predicting conservatism by past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat, by racial and ethnic subgroups

Model 1 shows that among Whites, both religious past and perceived threat are negatively associated with conservatism, although the effect of religious past is not statistically significant. Model 2 includes an interaction term between religious past and threat perception. In this model, being a religious “done” has no significant effect on conservatism when perceived threat is absent (i.e., Threat Perception = 0), while threat perception significantly decreases conservatism among religious “nones” (Religious Past = 0). The interaction term is negative, indicating the expected direction of conditionality, but it does not reach statistical significance.

Among Black respondents, Model 3 shows that both religious past and threat perception are significantly and negatively associated with conservatism. Model 4 adds the interaction term and reveals a similar pattern: threat perception significantly reduces conservatism among religious nones, while being a religious done has no effect when threat perception is absent. However, the interaction term remains statistically insignificant, indicating no evidence of conditionality in this group.

Models 5 and 7 show that religious past has no direct effect on conservatism among Latino and Asian nonreligious individuals, respectively, while threat perception continues to have a significant negative effect. In Model 6, we find that among Latinos, being a religious done does not affect conservatism in the absence of perceived threat, but threat perception significantly decreases likelihood of conservatism among religious nones. As in previous models, the interaction term is negative but not statistically significant. Model 8 follows the same pattern for Asian respondents: being a religious done has no effect when threat perception is absent, while threat perception itself is associated with lower conservatism. Again, the interaction term is not significant.

Taken together, interaction models across all four racial and ethnic groups (Models 2, 4, 6, and 8) do not provide statistical evidence for conditionality between religious past and threat perception in predicting conservatism. However, Figures 3 and 4 suggest more nuanced dynamics. In particular, the visualizations indicate that differences in conservatism between dones and nones become more pronounced as perceived threat increases for some groups, offering suggestive evidence of an interaction effect that is not easily observed in the regression models.

Figure 3. The interactive effect of past religion and perceived conservative Christian threat on conservatism, by racial and ethnic subgroups.

Figure 4. The marginal effect of past religion on conservatism across levels of perceived conservative Christian threat, by racial and ethnic subgroups.

Figure 3 presents results from the analysis across racial and ethnic groups and shows no significant effect for the interaction of religious past and threat perception on conservatism. However, Figure 4 highlights a conditional relationship: religious dones become significantly less conservative than religious nones as their perceived threat from conservative Christians increases—though this pattern emerges only for some groups.

More specifically, the marginal effects illustrated in Figure 4 show that religious past has no meaningful effect on ideological orientation when individuals perceive conservative Christians as posing little or no threat. However, when perceived threat is high, White, Black, and Latino religious dones are significantly less likely to endorse conservative positions compared to those reporting lower levels of threat perception. In contrast, Asian religious dones do not exhibit variation in conservatism across different levels of perceived threat.

Discussion

Nonreligious Americans are now such a large group that the political beliefs and distinctions between those who themselves left religion behind and those raised nonreligious has the potential to be relevant to politics. Subgroup differences such as the nones vs dones distinction will become even more important as the nonreligious grow into a majority. Furthermore, the nonreligious are a diverse group that can and should be studied intersectionaly across categories such as race. Distinctions are likely to emerge across among the nonreligious as the old stereotype of a young white male atheist becomes ever less accurate. The group is accurately described as a diverse multiracial one with a variety of backgrounds, including the distinction between nones and dones.

Our findings indicate that disaffiliated nonbelievers tend to lean towards left-wing policies, self-identify as highly liberal, and generally align more with left-wing political preferences across a range of social justice-oriented issues. However, we also find significant differences between nonreligious Americans from diverse racial backgrounds. Attention to subgroup differences remains an important area for further research as the nonreligious become a larger and broader group. Our findings suggest that among White, Black, and Latino nonreligious Americans, the distinctions between nones vs dones is more relevant. While the distinction produces null results among Asian Americans. This result may be due to a smaller sample size for Asian American dones, however, new data is needed to make such a determination.

We propose, and offer preliminary evidence for, the theory of social identity threat and negative associations with conservative religious beliefs as the driving forces behind the leftward shift of disaffiliated nonreligious Americans, compared to lifelong nonbelievers. Importantly, our findings are only preliminary. We are limited by data availability and can only speak to the questions present in the 2020 CMPS. Our evidence is not causal, nor enough to assert that our theory is true. This proposed theory builds upon existing research suggesting that the alignment of religious organizations with right-wing politics has alienated believers with left-wing inclinations, pushing them away from both religion and conservative political ideologies (Baker and Smith Reference Baker and Smith2015; Braunstein Reference Braunstein2022; Djupe, Neiheisel, and Conger Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Conger2018; Vargas Reference Vargas2012). Further study and better evidence are needed to fully explain the causal mechanisms driving divergent attitudes present among nonreligious Americans.

Despite not showing causality, our findings have clear implications for electoral politics, disaffiliated nonreligious Americans represent a huge voting block that is even more liberal than the lifelong nonreligious and perceives Conservative Christianity as threatening. Given ample evidence that identity threat can motivate turnout and voting behavior (Avery, Fine, and Marquez Reference Avery, Fine and Marquez2017; Heller-Sahlgren Reference Heller-Sahlgren2023; Major, Blodorn, and Major Blascovich Reference Major, Blodorn and Major Blascovich2018; Valenzuela and Michelson Reference Valenzuela and Michelson2016) it is likely that religious dones are receptive to messages framed against the Christian right. Such messages could be used to motivate this rapidly growing segment of the population to increase their participation in political activities. Our findings suggest that the Christian Right’s involvement in politics is not only driving disaffiliation, a finding established by other scholars (Baker and Smith Reference Baker and Smith2015), it may be generating a population highly motivated to oppose its policy aims.

Future work further examining the political distinctions between nones and dones should seek to establish a causal connection. Experimental work related to threat perceptions paired alongside open-ended qualitative data will likely be of particular use. The results presented here are suggestive and point to identity threat but cannot establish for certain what drives dones towards more liberal beliefs vs nones. Furthermore, additional work is needed to understand how race interacts with the effects of religious backgrounds among the nonreligious. Our findings outline patterns and can serve as a starting point. However, the available data does not allow us to answer questions of causality. Why the nones vs dones distinction is statistically insignificant for Asian Americans is an interesting question answerable only with further data. Likewise, the different effects sizes between racial groups are interesting and warrant further study.

Additionally, future work could address questions of political involvement. Does identity threat motivate nonreligious Americans to engage in political activity and does it function differentially for nones vs dones? Overall, there is minimal work examining subgroup differences among America’s rapidly growing nonreligious population so the area is a promising one for further investigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10055

APPENDIX:

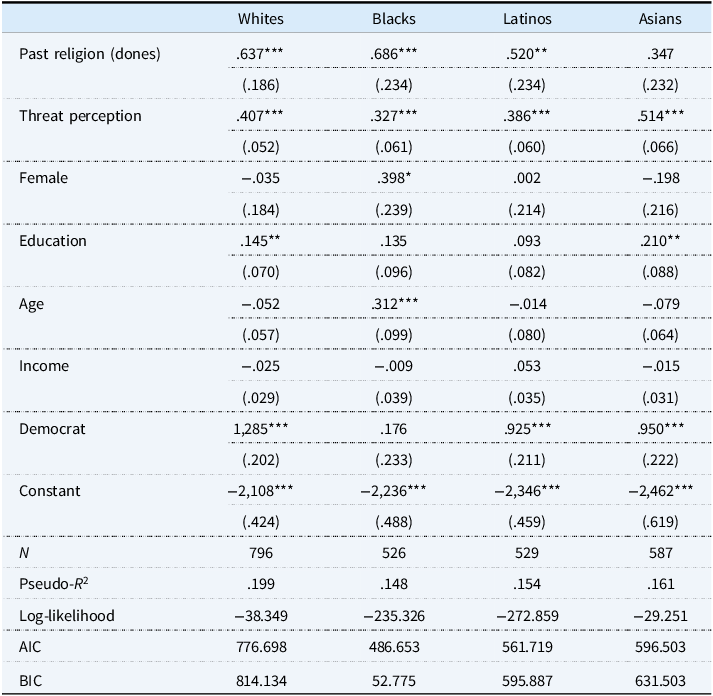

Table A1. Predicting support for voting rights by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups (full model)

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

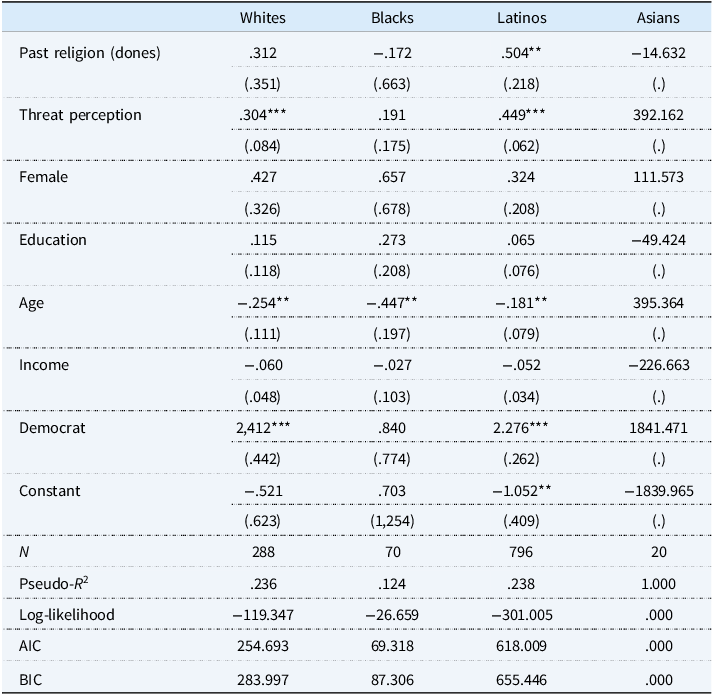

Table A2. Predicting opposition to trump’s immigration policy by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups (full model)

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

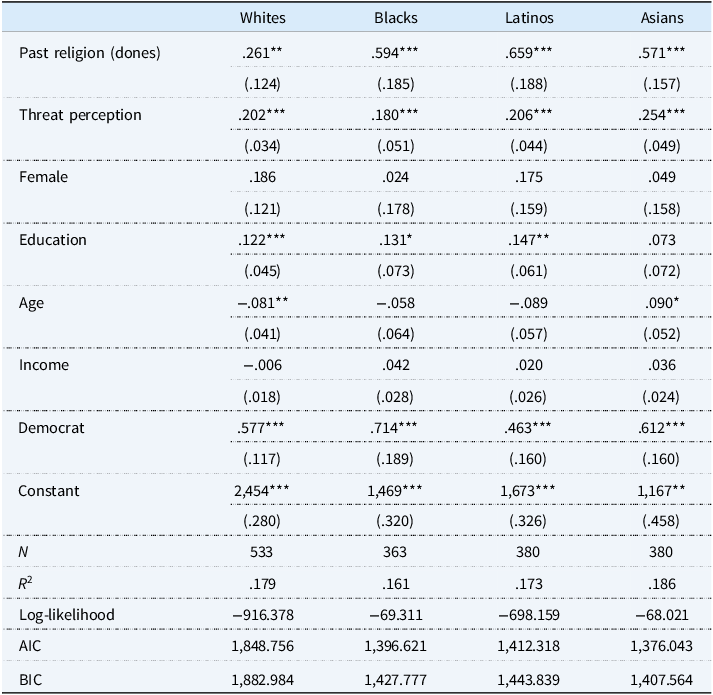

Table A3. Predicting support for abortion rights by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups (full model)

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

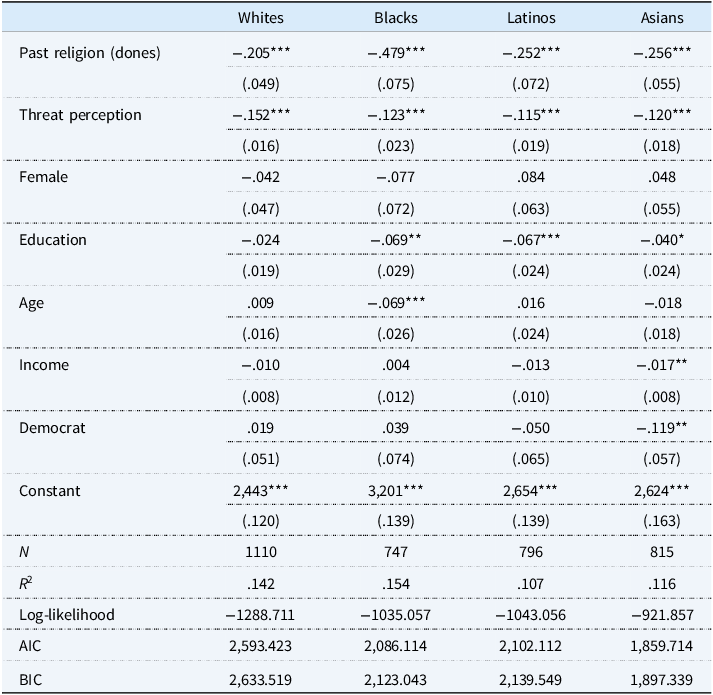

Table A4. Predicting opposition to same-sex marriage by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups (full model)

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.

Table A5. Predicting support for justice reform by past religion, by racial and ethnic subgroups (full model)

∗ p < .1, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗∗∗ p < .01. Standard errors in parentheses.