1 Introduction

A decade into the Xi Jinping era, China has become a full-throated proponent at home and abroad of what it refers to as “green development” (lüse fazhan). Until recently, it would have been common to hear Chinese officials explain why China was not yet ready to engage in environmental protection or emphasize that developed countries had the responsibility to solve the problem first. It now takes a very different tack on the environment, presenting itself as the “indispensable nation” in environmental affairs – an essential contributor to our most pressing global environmental issues. China’s turn towards the environment is evidenced by extensive environmental governance reforms, world-leading manufacturing and deployment of clean energy and electric vehicles, and greater protection of domestic ecosystems that serve as carbon sinks and home to biodiversity. Some have argued that these reforms have allowed China to go from “zero to hero” on the environment (Wang Reference Wang2020).

This positive image of China as an environmental leader runs up against continuing critiques of China’s environmental performance. Despite China’s move towards green development, it remains the largest absolute source of many pollutants. This is true for greenhouse gases (GHGs), traditional air, water and soil pollutants, ozone-depleting substances, and more. As Chinese society has grown wealthier, the country’s imports of raw materials, soft commodities, and endangered biodiversity have skyrocketed, placing extraordinary pressure on the global environment and resources. As Chinese companies have increasingly “gone global” to invest in infrastructure projects and acquire natural resources in countries around the world, environmental and social impacts have soared. Even as China has moved to address these problems with such measures as a domestic “war on pollution” and a major industrial policy push into clean energy, concerns have emerged about the efficacy and sincerity of China’s efforts, the country’s illiberal governance style, and the risks of excessive reliance on China for key energy and transportation technologies. More fundamental concerns that green development will enable China to surpass the US and Europe are ever more prominent. These perspectives see China not as a hero but as an existential threat to the natural environment and the existing global order.

This Element examines these debates over Chinese green development and the ways in which China is attempting to shape the discourse to be more favorable to its interests. Green development offers a powerful lens through which to examine China’s efforts to bolster its global reputation and to understand the opportunities and challenges China faces in doing so. Green development is becoming an important pillar of China’s case that it is a viable alternative to the dominant liberal democratic model represented by the US and Europe, and an indispensable contributor to the good of the global community. This is green development as a wide-ranging economic and political strategy to unsettle traditional views of China and bolster the legitimacy of Chinese power at home and abroad.

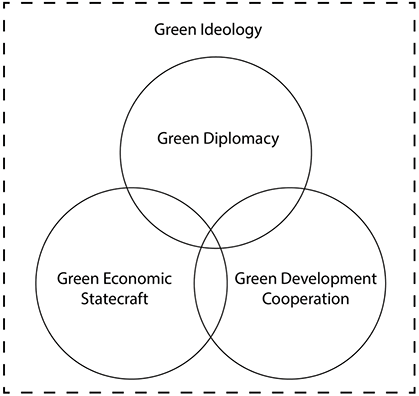

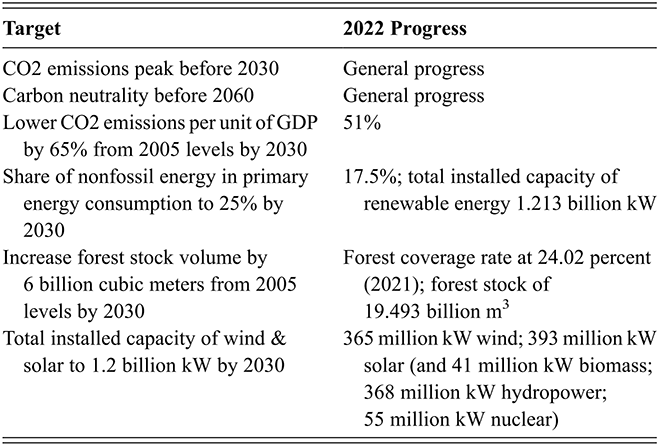

China’s turn toward green development is being carried out through four overlapping component parts, which I will refer to collectively as Chinese global environmentalism. These are: (i) an ideology of Chinese environmentalism, (ii) green diplomacy, (iii) green economic statecraft, and (iv) green development cooperation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Components of Chinese Global Environmentalism

These efforts are taking place in the context of polarized perceptions of China, its impact on the environment, and its place in the global world order. As this context both informs and is being shaped by Chinese global environmentalism, this introductory section outlines the most prominent discourses concerning China’s relationship with (and impact on) the environment.Footnote 1

Section 2 then offers a brief overview of the historical origins of Chinese global environmentalism, highlighting the iterative way in which Chinese domestic environmental governance and its international environmental engagements have evolved over time. This history sheds light on the developmental and political motives that dominate China’s environmental moves at home and abroad.

This section concludes by unpacking the characteristics of China’s emerging green ideology and its close connections to these core Chinese policy objectives of economic development and security. Such an approach has appeal to many audiences in developed and developing countries; however, the developmental focus of China’s green ideology also raises important unresolved questions about the relationship of man and nature (or development and the environment) that continue to generate controversy globally.

Section 3 discusses Chinese green diplomacy with detailed examinations of the Montreal Protocol and UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) contexts. In each instance, China can point to actions that support global environmental norms. In other instances, China is actively involved in shaping emerging environmental norms or engaged in vigorous contention over emerging environmental norms. China’s move from more defensive positions towards an embrace of affirmative diplomacy and participation in global environmental governance has garnered it accolades. Even so, weaknesses in environmental compliance and tensions over political rights and economic and security risks continue to raise concerns in some quarters.

Section 4 examines Chinese green economic statecraft. The focus here is on China’s efforts to “green” its outbound investment and trade. China has belatedly aligned itself with the global trend against overseas investment in coal plants, eliminating a major contradiction in Chinese overseas investment and its stated commitment to global climate goals. It has also, in a relatively short span of time, become the global leader in the manufacture and deployment of clean technologies. These moves can be understood as part of a strategy to gain economically from green industries, to reduce environmental risk, to position China as a supporter of global environmental and sustainable development goals, and to strengthen ties with countries in all parts of the world. The US and EU to varying degrees have come to see China’s growing dominance in the manufacture of clean technologies as an economic and security threat that should be countered through strategies of “derisking” or “decoupling.” This section also presents a case study of Chinese green development in Chile to illustrate one country’s pragmatic response to green competition among the leading global hegemons.

Section 5 discusses the emergence of Chinese green development cooperation. This is a rapidly evolving area in which China has moved from being a recipient of Western aid toward acting as a provider of assistance to the Global South (so-called “South–South” cooperation). It includes government, corporate, and civil society initiatives that serve as sites of technical exchange, relationship building, and image shaping. This section presents the cases of the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED) and the Belt & Road Initiative Green Development Coalition (BRIGDC), the Kenyan Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), and the Lancang-Mekong Environmental Cooperation (LMEC). The CCICED and the BRIGDC show the evolution of China from recipient to provider of green development assistance. The Kenyan SGR case sheds light on the conditions under which Chinese state-owned enterprises are more likely to respond to local environmental objections to Chinese development. The LMEC case shows how a Chinese-led regional cooperation institution manages environmental controversy over hydropower projects in the context of broader developmental and security priorities.

Section 6 concludes with implications of this study for our understanding of China’s rise and the future of the global environment.

Overall, Chinese global environmentalism has developed into a strategy aimed at several key objectives. It is an economic strategy to mitigate environmental risks of Chinese foreign investment and trade, obtain necessary raw materials, and seek markets for domestic overcapacity in clean technologies. It is a political strategy to build closer relations with Global South countries (“South–South” cooperation) and to present China as a peer great power on par with the US and the EU. It is further a legal and normative strategy to reshape international law and global norms in ways that support China’s interests. These strands all coalesce as a strategy to shape global understandings of China and bolster acceptance of Chinese power at home and abroad.

1.1 Discourses of Chinese Green Development

China is now seen in an unfavorable light in much of the developed world. Global polling shows highly negative views of China and Xi Jinping in liberal democratic countries (Silver et al. Reference Silver2022a, Reference Silver2022b). In the US, nearly eight-in-ten Americans have an unfavorable view of China, according to polling (Huang et al. Reference Huang2024, Reference Huang2025). Moreover, 89% of Americans see China as either an “enemy” (33%) or “competitor” (56%) (Huang et al. Reference Huang2025). While views of China are more favorable in middle-income countries, China still trails the US in favorability even in these countries (Silver et al. Reference Silver2023). Negative global perceptions are contributing to material consequences for China as other countries increasingly take trade, security, and other actions.

Polls of Chinese citizen satisfaction with the government suggest more stable public opinion in China’s domestic context, but this has not stopped Chinese officials and state media from attempting to bolster domestic support by highlighting Chinese global successes and promoting narratives of US decline (Carothers & Freedman Reference Carothers and Freedman2025).

Enter Chinese green development. The environment is an area in which China has traditionally been seen as a laggard and poor performer, but where active policy engagement, governance implementation, and manufacturing innovation have begun to reshape impressions of China in ways both dramatic and subtle. The struggle over what China stands for with respect to the environment, or its social construction in the eyes of global and domestic audiences, is a central focus of this Element.Footnote 2

In explaining the concept of constructivism in international relations theory, Alexander Wendt famously noted that “500 British nuclear weapons are less threatening to the United States than 5 North Korean nuclear weapons” because “the British are friends and the North Koreans are not” (Wendt Reference Wendt1995, p. 73). In other words, who states are understood to be matters in international relations. Consider instead the contrast between Western and Chinese framings of air pollution in China. Western commentators have commonly attributed China’s air pollution problems to its authoritarian political system, whereas Chinese experts more frequently treat it as a problem of development stage. Alternatively, consider the different responses to Korean or Chinese electric vehicles in the US. The former are seen as unthreatening export products, whereas the latter are associated with security risks, job losses, unfair trade practices, overcapacity, intellectual property theft, and undue political influence. In each of these examples, we can see who is considered a friend and who is not.

The following section delineates the contours of the debate about China and the environment, including critical and positive perspectives as well as the audiences likely to hold these views.Footnote 3 This clarification of discourses will set the stage for our discussion of the history of Chinese global environmentalism and the mechanisms of the Chinese global environmentalism playbook. It will also help to sharpen our sense of the ways in which China is attempting to reshape understandings of the country globally and at home through its pursuit of green development.

1.1.1 Critiques

Critical constructions of China and the environment have evolved over time with shifting emphasis as China has become more serious about (and more capable at) tackling its environmental problems. These are perspectives that the Chinese state has sought to counter or neutralize.

Weak Policy Formulation and Implementation. A prominent and long-standing critique holds that infirmities in China’s governance model hinder effective environmental policy formulation and implementation. Mao promoted the idea that “Man Can Conquer Nature” (rending shengtian) and China proceeded largely in defiance of the natural world in the early decades of the People’s Republic of China post-1949 (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001). Maoist China’s abuse of nature was closely linked to the political system’s abuse of people. This seeming disregard for the environment continued under the Reform Era push for economic development at all costs, despite ever more frequent official policy pronouncements of support for the environment (Smil Reference Smil1984; Economy Reference Economy2004). In a study of Chinese climate governance prior to the Xi era, Gilley argues that China’s environmental governance model was “more effective at producing policy outputs than outcomes” and that a more participatory approach might improve policy formulation and implementation (Gilley Reference Gilley2012 at 295, 298). In some instances, this has been framed more bluntly as greenwashing, or Chinese officials or firms saying one thing but doing another on the environment. This basic concern that China operates without much consideration for environmental priorities has only grown as Chinese companies have increasingly “gone out” into the world in search of natural resources, markets, and investment opportunities (Simons Reference Simons2013; Economy & Levi Reference Economy and Levi2014).

These accounts have in common a concern about the lack of institutional checks and democratic accountability within China’s authoritarian system. Scholars have long associated authoritarian systems with weak environmental protections and seen censorship, limits on political participation and civil society, and corruption as drivers of environmental degradation (Brain & Pal Reference Brain and Pál2019). The logic here is not difficult to understand. Environmental histories in democratic contexts such as the US, Europe, and Japan have emphasized the role of democratic processes, civic demand, or republican moments in bringing about modern environmental regulatory regimes (Schreurs Reference Schreurs2009). Where the channels for public participation are limited, one would expect government action to address environmental protection more slowly, if at all. Although scholars have more recently identified cases where developmental or reputational concerns have motivated environmental action in authoritarian states (Brain & Pal Reference Brain and Pál2019), the sense that environmental governance requires a system that responds to democratic demand remains strong.

Weak environmental performance also undermines China’s claims to legitimacy from economic performance. If the costs of environmental degradation amount to 6–8% of China’s GDP as World Bank studies have found, then Chinese economic growth looks less impressive than advertised (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson1997, p. 23; World Bank & PRC Govt. 2007).

“Bad” Authoritarian Environmentalism. As I will document in Section 2, Chinese officials began to take environmental issues more seriously during and after China’s 11th five-year plan beginning in 2006. As officials started to push for stronger environmental governance and to achieve demonstrable policy outcomes, a line of critique has shifted focus to China’s “state-led, coercive, authoritarian style” of environmental governance (Li & Shapiro Reference Li and Shapiro2020, p. 23). The most sustained argument in this vein has come from Yifei Li and Judith Shapiro in a book entitled China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet. They say that “there are admirable elements in the decisiveness of Communist Party policy makers on environmental issues, but there is also much to fear.” (Li & Shapiro Reference Li and Shapiro2020, p. 22). They argue that the “crackdowns, targets and technological surveillance tools used to implement environmental protection are also being used to assert and consolidate the hand of the state over the individual and over citizens groups … Not only are individual and social freedoms sharply curtailed by China’s approach but even the environmental successes are not always what they seem.” (Li & Shapiro Reference Li and Shapiro2020, p. 23). Examples cited include Shanghai’s recycling program, botched implementation of a switch from coal to natural gas in northern China, afforestation by monoculture, forcible resettlement of local populations in the name of ecosystem restoration, and even China’s one-child policy. Human rights groups have joined in this criticism of authoritarian environmentalism, arguing that “the Chinese government harnesses its vast surveillance power to enforce environmental rules,” and severely restricts “what citizens and civil society groups can say or do” on environmental issues (Wang Reference Wang2022). Other scholarly accounts in this vein include Denise van der Kamp’s (Reference van der Kamp2020) research on China’s “blunt force” regulation through which “officials forcibly shutter or destroy factories to reduce pollution, at immense cost to local growth and employment.” Under this view, the Chinese government is wielding authoritarian means to achieve environmental ends and is further using environmental goals to justify tighter political control and weakened civil liberties.

As China has prioritized green development and built substantial clean energy industries, newer critiques have emerged concerning the economic and security risks of Chinese green development and the broader geopolitical risks associated with China’s rise. I address each of these in turn next.

Economic & Security Risks. China’s growing dominance in key clean energy industries – solar, wind, electric vehicles, and so on – has raised concerns over a surprisingly broad range of economic and security risks. These include concerns about espionage, intellectual property theft, job losses, resource competition, risk of geopolitical conflict, supply chain disruption, price shocks, critical infrastructure vulnerability, and dual use (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson2022). The empirical basis for these economic and security risks is hotly contested. Nonetheless, it is beyond dispute that policymakers in the US, EU, and elsewhere have framed clean energy industries as strategic pillar industries that cannot be ceded to China, and have begun to implement a host of tariffs, security measures, and industrial policy initiatives designed to compete with and constrain Chinese green development growth. As further discussed in Section 4, Global South countries, on the other hand, who stand to benefit from strong trade relationships or access to low-cost, high-quality clean energy technologies, have tended to view Chinese green development more as an opportunity than a risk.

Hegemonic Displacement Risk. Underlying these debates over economic and security risks is perhaps a more fundamental concern – that green development will enable China to displace the US as the leading global hegemon. Realist international relations scholar John Mearsheimer has, for example, criticized US engagement policies that “created a geopolitical rival” and argued that the US should have instead begun to check Chinese economic growth early in the Reform Era (Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2021). His basic argument is structural – that the scale of China’s population and economic growth will lead to growing military power that the US must counter in some way, by developing more quickly itself or slowing down Chinese growth. On this view, green development is among a group of industries, including quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and semiconductors, that will determine which country dominates the world in the future, economically, technologically, and militarily. Hegemonic displacement risk is of particular concern in “within the Beltway” discourses in the US, but is also salient in other jurisdictions that support or prefer a US-led world order.

1.1.2 Positive Perspectives

These negative critiques are tempered by more positive perspectives that have also evolved over time as China increasingly embraces green development and aligns its domestic political economy with global environmental norms. These sometimes track official Chinese rhetoric but have also developed independently and in relation to the perspectives of particular audiences (e.g., environmental experts and advocates; Global South countries; and actors disillusioned by existing Western approaches to environmental protection).

Developmental Perspectives. One way to understand China’s environmental challenges is not as a problem of political model, but rather as a consequence of development stage. The Environmental Kuznets Curve predicts an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic development and environmental degradation. That is, environmental degradation increases with per capita GDP at lower levels of development until a tipping point, after which environmental degradation decreases as incomes rise. This is hypothesized to happen because rising incomes increase public demand for environmental amenities, provide the resources for investment in pollution control, and lead the economy to shift toward less polluting industries (including through pollution export).

Such a view puts less emphasis on political differences and sees China as following a path already trodden by the US, Europe, Japan, and other developed countries in some instances and engaging in governance innovation in others. Once again consider China’s air pollution problems. For a time, severe air pollution in China received intense negative attention from the international community, and Beijing became a global symbol of bad air pollution and weak environmental governance. After China’s extensive “war on pollution” and a national air pollution action plan, air pollution has improved markedly throughout the country, and Beijing is no longer even in the top 100 of most polluted cities in the world (Myllyvirta & Howard Reference Myllyvirta and Howard2018). Beijing’s elimination of the “airpocalypse” has become a symbol of Chinese environmental success. Previously a marker of regulatory failure, it will now likely go down in history as a dark yet ultimately fleeting moment in Chinese environmental history and development akin to famous environmental incidents in the US (the 1948 smog incident in Donora, PA or Cuyahoga River fires in the 1960s), England (the 1954 London “fog”), and Japan (Minamata mercury poisoning, cadmium pollution and itai-itai disease).

Chinese officials often point out that China has been going through a period of environmental troubles much like what the developed world experienced at earlier stages of development. At times, they have even used the comparison to suggest that China is tackling more serious environmental problems in a shorter span of time than other countries. These arguments gain much of their force from the fact that China is not unique in facing serious environmental consequences of industrialization and is arguably performing “no worse than” or even “better than” its peer rivals at similar stages of development. I elaborate on this idea in the discussion of “relational perspectives” in Section 1.1.3.

“Good” Authoritarian Environmentalism. Chinese global environmentalism also draws on positive impressions of Chinese environmental governance that have emerged in recent years, particularly as China has made some environmental progress and rapidly developed clean energy technologies. An influential view sees China as a productive authoritarian environmentalism characterized by “its ability to produce a rapid, centralised response to severe environmental threats, and to mobilise state and social actors” (Gilley Reference Gilley2012). What’s more, given the severity of global environmental degradation, a “‘good’ authoritarianism, in which environmentally unsustainable forms of behaviour are simply forbidden, may become not only justifiable, but essential for the survival of humanity in anything approaching a civilised form” (Beeson Reference Beeson2010).

Official Chinese rhetoric in the Xi era has emphasized the value of “top-down design” (dingceng sheji) and contrasted China’s approach with liberal democratic approaches that are seen as excessively contentious or deliberative, too slow, or captured by industry (Qiu Reference Qiu2024). Put another way, China is more able to “get things done” in infrastructure development, manufacturing, and policy implementation than its democratic counterparts. The empirical basis for these claims is hotly contested, but demonstrable Chinese successes in the Xi era (e.g., air pollution reduction, clean energy deployment, high-speed rail) have offered support for this point of view.

China’s top-down, state-driven approach to global environmental governance has influenced norms concerning environmental governance globally. This can be seen, for example, in the turn toward green industrial policy in the US and EU. The US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan have emerged as countermeasures to China’s industrial policy push for green development. Particularly in the US, such measures would have been politically untenable in past years. Although Republicans still largely oppose such measures, the success of Chinese industrial policy has dramatically shifted the Overton window on green industrial policy in the US.

Beyond global debates about the merits of authoritarian environmentalism, China’s rise has also spawned some intellectual interest outside of China in Chinese ideologies of ecological civilization. Philosopher Arran Gare has, for example, praised Chinese ecological civilization in a series of books and articles (see, e.g., Gare Reference Gare2017). Anna Lake Zhu has explored the idea of different Chinese notions of environmentalism in a study of Chinese import of rosewood from Madagascar (Zhu Reference Hu2022). Although these do not reflect mainstream views, they are nonetheless examples of engagement with Chinese ideologies within intellectual communities outside of China that grapple with Chinese ideas as possible alternatives to dominant Western modes of thinking.

Pragmatic Perspectives. Outside of the developed world, China’s push for green development has received more nuanced reception. China has become an important source of investment in renewable energy and clean technologies. It is an important export market for countries producing critical minerals and other raw materials necessary to clean energy supply chains. It now manufactures the clean energy technologies and electric vehicles that countries need to meet green development objectives. These contributions to economic growth and clean energy transition offer other countries a pragmatic reason to engage with China and to resist the politicization of China’s rise. Even though these investments and economic engagements have not been without controversy in these other countries, they are nonetheless being met with greater openness than in the US and EU. The US and EU have increasingly sought to counter closer Chinese ties in the Global South, warning countries of the risks of Chinese debt trap diplomacy, inadequate environmental protections, weak labor practices, and the like. At least in some jurisdictions, these warnings have not had their intended effect and have been viewed as hypocritical or merely politically motivated, rather than genuine reflections of risks on the ground.

As a structural matter, China’s engagement in global green development has also spurred a competition for the favor of Global South countries among China and its chief rivals in the US and Europe. As with so-called “vaccine diplomacy” during the COVID-19 pandemic, Global South countries may garner greater aggregate benefits as the major powers attempt to outdo one another. In the green development context, for example, the US and Europe have competed with China to offer Global South countries greater support for green development and a chance to move up the value chain. Chinese companies have built or offered to build manufacturing or processing facilities in countries that previously only served as sources of raw materials. China has introduced a South–South Climate Cooperation Fund, although the fund has been criticized for disbursing very little since its inception. The US, Japan, and EU countries have countered with programs like the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), meant to facilitate clean energy transition in South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam, Senegal, and other countries. The US, however, exited the partnership in March 2025 at the beginning of the second Trump administration.

1.1.3 Relational Perspectives

China’s reputation is not assessed in a vacuum. There is a relational component as well. That is, Chinese standing is influenced in important ways by how China is seen in relation to its chief rivals, for better or worse.

Western observers may take some comfort in studies showing that China remains less popular than the US in much of the world. Pew polls have shown a more than 50 percentage point difference in favorability ratings of the US and China among those surveyed in the US, Japan, South Korea, and Poland and more than 30–40 percentage points in western European countries, Canada, Australia, India, and Israel (Silver et al. Reference Silver2023). Allan et al. (Reference Allan2018) have argued that “China is unlikely to become the hegemon in the near term” because, unlike the US, it is not backed by an ideology that appeals to elite and mass audiences within major countries. The four critiques of China described previously have all arisen in contexts where China is seen as inferior to Western models of rule (e.g., democratic, rights- and market-oriented) as a matter of values or performance.

I nonetheless argue though that China’s standing may be enhanced in at least three potential ways connected to how China is seen in relation to its competitors.

First, China may simply gain in standing by performing better than its rivals in tackling environmental problems. China’s dominance in clean technology manufacturing and deployment is an example of an area in which China is making gains relative to the US and Europe (see, e.g., Lewis Reference Lewis2012; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2014; Nemet Reference Nemet2019; Nahm Reference Nahm2021).

Second, China may get a boost in standing if its rivals begin to perform worse than expected. The Trump administration’s multiple withdrawals from the Paris Agreement and aggressive attacks on renewable energy and electric vehicles, for example, give China an easy opportunity to present itself as a global climate leader, despite extensive criticisms of China’s absolute level of emissions, continued domestic expansion of coal-fired power plants, and shifting of emissions abroad.

Third, China may be viewed in a more positive light if its actions are seen as “no worse than” what the US and other rival countries have done. It matters, for example, that the US, European countries, and Japan all experienced similarly dire bouts of pollution and environmental degradation during the most intense periods of industrialization. Chinese green development may be seen as a more viable alternative to dominant Western notions of sustainable development despite its imperfections if sustainable development is also seen as fraught with contradictions or problems. It makes a difference if Chinese companies are performing no worse than developed country multinational corporations on environmental impacts in global investments.

Alternatively, China will arguably need to do more to enhance its global standing if its chief rivals are performing well on the environment or achieving results in ways that the relevant audiences find preferable.

* * * * *

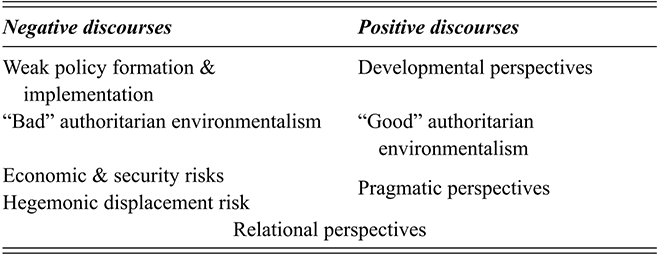

The various perspectives discussed earlier are summarized in Table 1. Relational perspectives can temper or strengthen the effect of any of these other discourses on Chinese standing. China’s efforts to promote green development play out against this backdrop.

Table 1Long description

Four negative discourses are listed: weak policy formulation & implementation; bad authoritarian environmentalism; economic & security risks; and hegemonic displacement risk. Three positive discourses are listed: developmental perspectives; good authoritarian environmentalism; and pragmatic perspectives. Relational perspectives is listed as a discourse that could be either negative or positive towards China.

We next turn to a brief history of domestic developments that presage Chinese global environmentalism. The picture that emerges differs from both official Chinese narratives and the more critical takes on Chinese environmental governance. Rather, what we find is a fragmented and imperfect process that has nonetheless moved incrementally over time toward the achievement of some environmental policy goals while falling short on others. This history sets the stage for a discussion of the emerging ideology of Chinese global environmentalism.

2 Chinese Global Environmentalism: Origins & Ideology

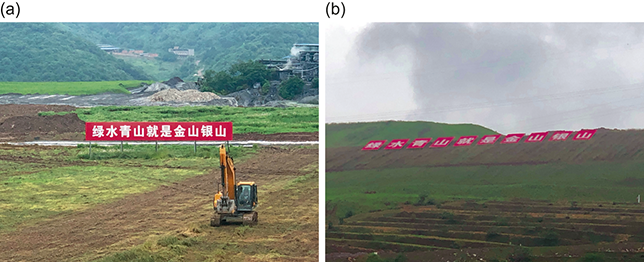

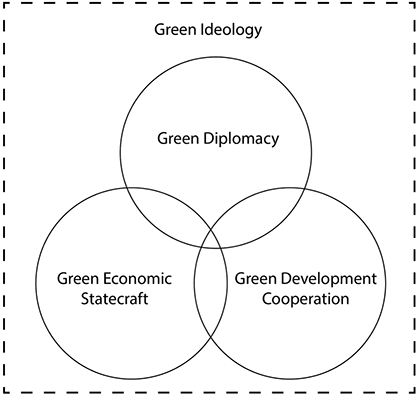

In May 2019, I found myself at a toxic soil remediation site in the far western Chinese municipality of Chongqing. The site was operated by a subsidiary of Sinochem Corporation, one of the largest chemical companies in the world. Nestled among rolling hills near the banks of the Yangtze River in the town of Fuling, the site was a showcase for the increased priority of environmental protection under Xi Jinping. Prominently placed on top of a mountainous waste pile in characters the size of the Hollywood sign was a phrase that could be loosely translated as “green is gold (see Figure 2).” This is the key slogan associated with Xi Jinping’s concept of ecological civilization and the company was making it clear that the signals from Beijing had been well-received.

Figure 2(a) and 2(b) “Green is Gold (lüshui qingshan jiushi jinshan yinshan),” Fulin District, Chongqing (May 2019, author photos).

When I first began working on environmental issues in China in the late 1990s, this sort of remediation site would have been unimaginable. In a rural place like this, local government officials would have had little interest in environmental protection amidst the country’s relentless push for economic growth. If we were able to speak to local villagers, their stories would often sound in hopelessness: damaged crops, cancer villages, unchecked pollution, and unresponsive local officials.

The remediation site here was meant to signal a new Chinese direction on the environment. Billboards highlighted some forty high-level visits to the site from central and provincial Party and government officials, suggesting the importance of the site as a showcase for China’s environmental turn. Our small group of “foreign experts” touring the site was in Chongqing to speak at a regional training for Chinese judges on legal methods for handling soil pollution disputes. The very fact that judges were engaging in discussions on such technical environmental issues suggested that China was in a more environmental place than even just a few years before. The following history seeks to explain this evolution.

2.1 China’s Long March toward Green Development

State legitimacy and the natural environment have long been connected in Chinese governance philosophy since as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty (1045–771 bce). Natural disasters, like floods, droughts, and earthquakes, were seen as signs that the Heavens were dissatisfied with a ruler and that the ruler was losing the “Mandate of Heaven” (Zhao Reference Zhao2009). Environmental problems thus were associated with dynastic collapse and could bolster the position of those seeking to rebel against existing rulers. The collapse of the Tang Dynasty in 907 ce has been attributed to prolonged drought, a cooling climate, and a weakened monsoon that harmed agricultural output and produced widespread famine (Gao et al. Reference Gao2021). The Ming Dynasty’s end in 1644 ce has been tied to a Little Ice Age, several periods of severe drought, locust plagues, flooding, and volcanic activity that likewise caused famine, infrastructure destruction, and social unrest (Zhang Reference Zhang2010). Given this history, the connection between environmental problems and regime stability cannot be far from the minds of present-day Chinese rulers.

Nonetheless, under the CCP, China paid little attention to environmental protection prior to the commencement of Deng Xiaoping’s Reform Era in 1978 (Smil Reference Smil1984; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001). This was a period of resource-intensive growth driven by Mao-era policy and “output-oriented state planners and production ministries” (Ross Reference Ross1992, p. 628). Internationally, China participated in the 1972 Stockholm conference, but its interventions at the time were combative and ideological. The head of the Chinese delegation blamed environmental problems on capitalism and US imperialism and focused his public remarks on criticizing US involvement in the Vietnam War. Nonetheless, Chinese preparations for the Stockholm meeting led to the creation of the first Chinese environmental institutions. China’s State Council convened a first National Conference on Environmental Protection in 1973 and established a Leading Group on Environmental Protection in 1974 (Xie Reference Xie2020). But consumed by political turmoil and with a per capita gross national product of only US$75, the environment was simply not a priority during this period (Cai & Voigts Reference Cai and Voigts1994).

When the country emerged from the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, China was a broken and impoverished nation and environmental matters were hardly top of mind. In December 1978, the decision of the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the CCP marked the commencement of China’s post-Mao Reform Era. This was a period of dramatic economic reform and growth averaging more than 10% per annum. Rapid economic expansion brought with it increasingly severe environmental problems. Perhaps surprisingly, construction of an environmental regulatory regime commenced at the very start of this period. Contemporaneous accounts attribute this to elite awareness of the social costs of pollution and ecological damage (Ross Reference Ross1992). This environmental regulatory activity could also be seen as part of the broader effort at the time to rebuild a legal system and bureaucracy that had been decimated during the Cultural Revolution.

In 1979, the National People’s Congress passed a framework Environmental Protection Law. Over the next two decades China would pass environmental laws on marine environmental protection (1983), forestry (1984), water pollution (1984), air pollution (1987), water resources (1988), and water and soil conservation (1991), solid waste (1995), and noise pollution (1997), among others. Nonetheless, these legal authorities tended to be weak with vague and hortatory provisions, and environmental authorities were subordinate players within the bureaucracy with limited power (Alford & Shen Reference Alford and Shen1997).

At the national level, China’s lead environmental institution progressively gained bureaucratic status in successive governance reforms but continued to be subordinate to powerful development-oriented actors within the system, such as the State Planning Commission, the Ministry of Finance, and production-oriented ministries. At the local level, environmental protection bureaus faced fundamental limits on their enforcement powers. They reported to development-oriented local governments that controlled their budgets and staffing (Jahiel Reference Jahiel1998; Ma & Ortolano Reference Ma and Ortolano2000). This structural dynamic contributed to persistent local protectionism and weak environmental enforcement within China.

During this period, China made certain advances in environmental protection. The legal, policy, and institutional foundations established during this period would pave the way for later reforms. Indeed, one contemporaneous account called post-Mao environmental reforms “an extraordinary turnaround, dispensing with revolutionary rhetoric in favor of a more pragmatic approach to contemporary problems” (Ross & Silk Reference Ross and Silk1987). Moreover, rapid expansions of light industry and a shift toward greater market orientation led to efficiency increases and reductions in pollution intensity. But China’s evolving environmental regulatory regime could hardly keep up with the pace of rising environmental degradation. Although Li Peng declared environmental protection to be a basic state policy in 1983 and senior leaders repeatedly stated that environmental protection should proceed in tandem with economic development, in practice environmental priorities would continue to take a backseat to economic objectives.

The economic focus was hardly surprising, given China’s relative poverty and the importance of rapid development to the Party’s hold on power. Chinese leaders saw economic development as a key to stability in the wake of Tiananmen Square crackdown and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Underpowered environmental laws and weak environmental regulatory agencies were arguably a feature of the system at this time, rather than a bug. Environmental protection had its supporters at the elite levels, but rapid economic development remained the overwhelming priority.

Internationally, China was active in environmental diplomacy during the first two decades of the Reform Era. Between 1978 and 2000, China acceded to some thirty-one international environmental agreements (Cai & Voigts Reference Cai and Voigts1994, pp. S-24; Ross Reference Ross1998, p. 815). Its early environmental diplomacy was part of an overall effort across issue areas to rejoin the international community and to limit Taiwan’s participation in these spaces. China’s environmental diplomacy in the early years was in significant part also aimed at fending off limits on development, blocking potential threats to state sovereignty, and obtaining funds and capacity-building assistance for domestic environmental work.

Although China’s historical contribution to global environmental problems at the beginning of the Reform Era was limited in comparison to that of the US or European economies, rapid economic growth brought about substantial increases in Chinese emissions of ozone-depleting substances, GHGs, and other pollutants. China’s expanding global environmental impacts brought with it greater international scrutiny and Chinese concern about the potential for international restrictions (Economy Reference Economy1998, p. 270). This led to a push, commencing in the late 1980s, to develop Chinese “environmental diplomacy” (huanjing waijiao) and to train a cadre of environmental specialists to take part in international meetings and to represent Chinese interests (Ross Reference Ross1998).

In 1990, a cross-agency process led to the creation of a set of negotiating principles for Chinese environmental diplomacy. These were, perhaps unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly developmental, although some voices within the system hoped to emphasize China’s responsibilities to the international community and the potential for environmental problems to harm China itself. Among the participants in these debates, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the State Planning Commission pushed for developmental positions, whereas the National Environmental Protection Administration (NEPA) and the powerful State Science and Technology Commission (SSTC) supported more environmental positions (Economy Reference Economy1998, pp. 270–272).

China publicly aired its support for these principles at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio. Premier Li Peng’s speech at Rio emphasized development and sovereignty. China offered full-throated support for the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR), which emphasized the role of developed countries in causing global environmental problems and their responsibility to move first and to offer support for global action. The concept of CBDR would also appear in the UNFCCC and in substance in the Convention on Biological Diversity. The principle was reflected notably in the bifurcated structure of the Kyoto Protocol, under which developed countries had binding emissions targets and developing countries, like China and India, did not.

Although China’s most pro-environmental actors did not succeed in setting a more environmental agenda for the country at the diplomatic bargaining table, they were highly successful in obtaining funding, technology, and capacity building through environmental diplomacy and international cooperation in this period. These efforts were led by legendary environmental figures like Qu Geping – head of NEPA (1987–1993); Song Jian – head of the SSTC; and Xie Zhenhua – head of China’s environmental agency from 1998 to 2005 and later China’s lead climate negotiator (Economy Reference Economy1998).

An early success came from the 1990 negotiations of the London Amendments to the Montreal Protocol, where China successfully pushed for the creation of a multilateral fund (MLF), with China and India receiving substantial amounts through the fund. During this period, China received billions of dollars (USD) in funding from international institutions, including the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility, the Asian Development Bank, and the United Nations Development Program and bilateral sources (Economy Reference Economy1998). China received 80% of its environmental budget from foreign sources at one point (Economy Reference Economy1998).

By the turn of the millennium, Chinese environmental protection had made some progress but was still stymied by low political priority relative to the economy, weak laws and institutions, bureaucratic fragmentation, insufficient funding, and limited public participation.

2.2 Initial Moves to Green Development

As China joined the WTO in 2001, it was a country that had experienced unprecedented economic growth over two decades. But this growth also produced extraordinary environmental problems in air, water, soil, and ocean pollution; land degradation, deforestation, and erosion; and biodiversity loss (Liu & Diamond Reference Liu and Diamond2005). Environmental devastation generated high levels of economic losses, such as from water shortages, sandstorm damage, agricultural damage from acid rain, and the cost of combatting harmful invasive species. Recognition of the health costs of pollution was growing. An influential 1997 World Bank study examined health, ecosystem, and agricultural costs of air and water pollution, and estimated that environmental costs were 8% of GDP (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson1997, p. 23). Another study put losses from pollution and ecological damage at 7–20% of GDP (Liu & Diamond Reference Liu and Diamond2005). Social conflicts due to environmental problems in the form of protests, disputes, lawsuits and the like were on the rise.

In 2001, Chinese leaders introduced, at the highest levels of the system, the idea that environmental concerns could be a potential limit on economic development. In remarks announcing China’s 10th five-year plan, Premier Zhu Rongji commented that resource limits (fresh water, farmland, energy, and strategically important minerals) and environmental degradation would limit China’s ability to continue in the “crude manner of growth” that the country had embraced in prior decades. These statements are consistent with Jiang Zemin’s remarks a few years earlier at the 1996 fourth National Environmental Protection Conference, which marked the first time a top leader had noted that environmental protection “could not be subordinated without affecting long-term development” (Ross Reference Ross1998). Senior environmental officials like Qu Geping had much earlier called for greater constraints on development in the name of environmental protection, but the idea had now been taken up by China’s most senior leadership.

Entry into the WTO would slingshot China’s economy to further growth, increasing demand for energy and resources and placing ever greater pressure on the environment. China’s economy would grow by more than ten times, and Chinese exports would expand by more than five times in the next fifteen years. During the 10th five-year plan (2001–05), in addition to worsening pollution, China suffered from nationwide power shortages, and, between 2002 and 2005, economy-wide energy intensity (the amount of energy expended to produce a given unit of GDP) increased for the first time since the early 1980s. These developments exacerbated leadership concerns about energy security and ecological limits on development and spurred greater interest in energy efficiency and pollution reduction programs.

During the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao administration from 2002 to 2012, officials considered environmental policy under broader Hu-era political framings that emphasized “scientific development” (kexue fazhan) and “people at the center” (yiren weiben). As a concept, “scientific development” was meant to convey the need for higher-quality, efficient growth, a contrast to the “development at all costs” approach that had been the norm. In the eyes of many within the system, a December 2005 State Council Decision on Implementing Scientific Development and Strengthening Environmental Protection (the “Decision”) marked a turning point in the priority of environmental protection as a Party-state political priority (PRC State Council 2005). The document was frank in its assessment of China’s environmental problems. The official characterization of China’s environmental crisis now acknowledged “huge economic losses, threats to public health, social stability and environmental safety” as potential consequences.

The Decision explained the motivations for Chinese environmental policy:

The strengthening of environmental protection is beneficial to such activities as economic restructuring; transformation of growth mode and better and faster growth; the development of environmental industry and its relevant industries; fostering of new growth engine and increase of employment; the rise of environmental awareness and moral level of the whole society to promote the development of socialist cultural and ideological progress; guarantee of public health, raising living standard and longevity; the long-term interests of the Chinese Nation and pass on a good environment for our future generations.

Released just three months after the Decision, China’s 11th five-year plan (2006–11) reflected an “environmentalist worldview,” and marked “the first time that the national government has been so strongly committed to the environment” (Naughton Reference Naughton2005). The 11th five-year plan contained for the first time binding environmental and energy targets, instead of non-mandatory guidance targets. These “energy saving, pollution reduction” targets (jieneng jianpai mubiao) were designed to promote greater economy-wide energy efficiency and reductions in air and water pollution. In my field research, local officials in multiple cities described this as a turning point on the environment. They openly admitted to ignoring the pollution targets in the first year of the five-year plan (because such targets had never previously been important), but also reported that the central government made concerted efforts over the next few years to signal to local officials that these targets were now to be taken more seriously (Wang Reference Wang2013).

A panoply of policies and laws emerged during this period to implement the targets. In 2006, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) launched the “Top 1,000” enterprises program to improve energy efficiency at the country’s largest companies. The NDRC also announced a ban on inefficient “backward production capacity” (luohou channeng) in the most energy-intensive industries, including steel, cement, and non-ferrous metals. China’s legislature passed the 2005 Renewable Energy Law, which would lay the groundwork for the subsequent development of Chinese solar, wind, battery, and other clean energy industries.

This was also a period of public ferment over environmental issues, with increased public awareness, burgeoning public protest, an invigorated civil society and growing global attention to China’s environmental woes. On the ground, observers noted that the Decision and the 11th five-year plan emerged amidst ferocious sandstorms in Beijing that dumped some 300,000 tons of sand on the capital (Xinhua 2006). Large-scale environmental accidents, like the 2005 Songhua River benzene spill, occurred with regularity. Environmental protests increased by 29% per year between 1996 and 2011 (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2012).

Environmental civil society groups experienced a golden age not seen before or since. China’s earliest environmental groups, such as Friends of Nature, Wang Yongchen’s Green Earth Volunteers, and Liao Xiaoyi’s Global Village of Beijing, pushed for conservation of charismatic megafauna and wild places. Others like former reporter and activist Ma Jun and lawyer Wang Canfa brought attention to pollution with Ma’s book China’s Water Crisis and Wang’s law school-based legal organization, the Center for Legal Assistance to Pollution Victims (CLAPV). Smaller regional or local NGOs like Yun Jianli’s Green Hanjiang, Huo Daishan’s Huai River Defenders, Yu Xiaogang’s Green Watershed, and Wu Dengming’s Green Volunteer League of Chongqing acted as local monitors of pollution.

Chinese officials experimented with public participation and transparency mechanisms during this period. Laws like the Administrative Licensing Law set forth procedural rights to participation in administrative hearings. China’s State Council passed a regulation on open government information in 2007, with China’s environmental agency the first to create implementing measures.

Despite this progress, a yawning gap remained between “laws on the books” and “law in practice.” Local protectionism of industry remained a persistent problem. Local firms and protective government officials colluded on data falsification and looked the other way at illegal dumping. Environmental lawsuits encountered unsympathetic local judges. The 11th five-year plan ended chaotically. Officials reported that environmental and energy targets had largely been met. At the same time, the head of NDRC issued a public apology about widespread cheating among localities struggling to meet their goals (Wang Reference Wang2013, pp. 421–422, 431). Some officials shut down power to hospitals and stop lights to conserve energy. Firms used highly polluting, off-grid diesel generators to obtain power without registering the energy use in official statistics. China’s turn toward the environment had begun, but its initial implementation was fraught.

2.3 The Rise of Ecological Civilization

As the 11th five-year plan concluded and the Hu-Wen administration prepared to step down, it was not at all clear that China would continue to build on its fledgling environmental and climate reforms. Yet, as Xi Jinping ascended to power, China broadened its domestic environmental reforms and took aggressive steps to deepen the ideological and institutional foundations of these reforms under the rubric of ecological civilization. This included expansion of binding environmental and energy targets, a proliferation of new environmental and energy laws and policies, and institutional reforms aimed at centralization of regulatory authority and tightening of enforcement and implementation. These moves suggested that China’s environmental measures were more than merely symbolic. Observers have argued that these reforms were motivated by a complex mix of factors, including concerns about continued economic development and energy security, popular demand for reduced pollution, technocratic response to potential impacts of climate change on China, international normative pressures, and a strategic interest in getting ahead of shifts in energy structure and technology demanded by global climate agreements (see, e.g., Boyd Reference Boyd2012; Wang Reference Wang2018b).

The concept of ecological civilization was elevated domestically through leadership speeches; incorporation into party doctrine, policy, and law; and campaign-style promotion. The concept was folded into core Chinese Communist Party ideology in 2012 with the announcement of the CCP’s so-called “five-in-one” development ideology (wuwei yiti). This placed the environment on par with economic, political, cultural, and social construction as core CCP objectives. The concept of eco-civilization was added to the CCP Constitution in 2012 and the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China in 2018. Moreover, the idea of ecological civilization was linked to overarching CCP centenary goals of achieving a moderately prosperous society (xiaokang shehui) and solving extreme poverty by 2021 (the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP) and building “a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious” by 2049 (the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)), with an interim goal to “basically realize socialist modernization” and a “Beautiful China” by 2035. In 2023, China’s National People’s Congress designated August 15 as National Ecology Day. Each of these moves signaled an increase in the political priority of environmental governance.

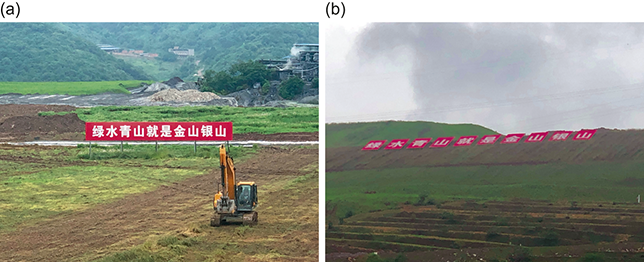

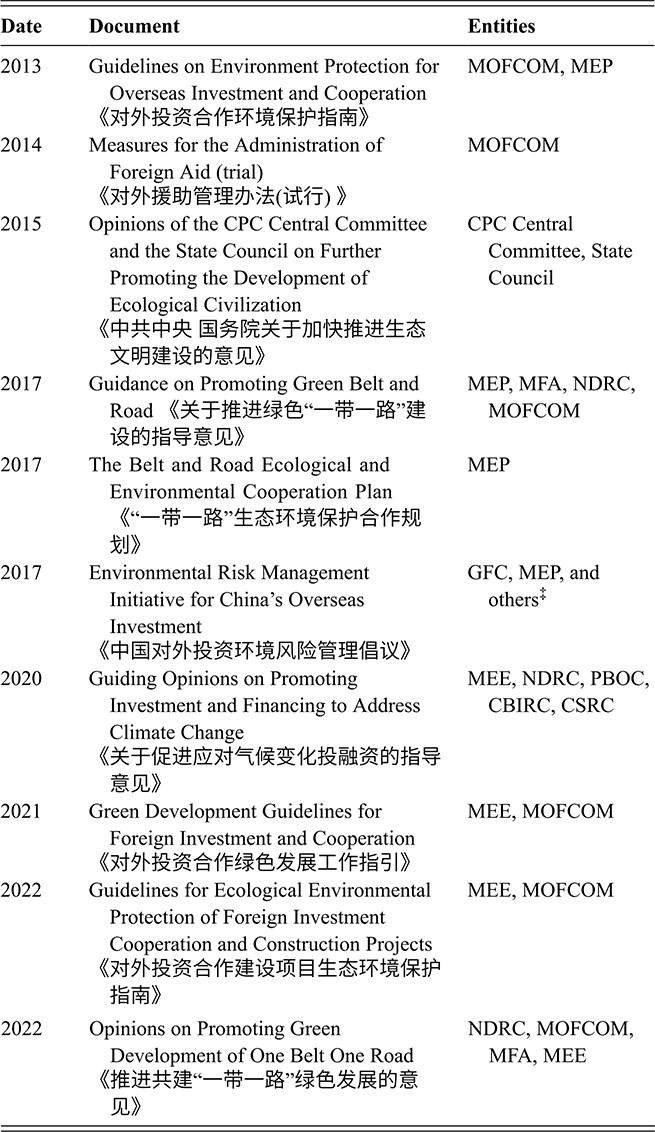

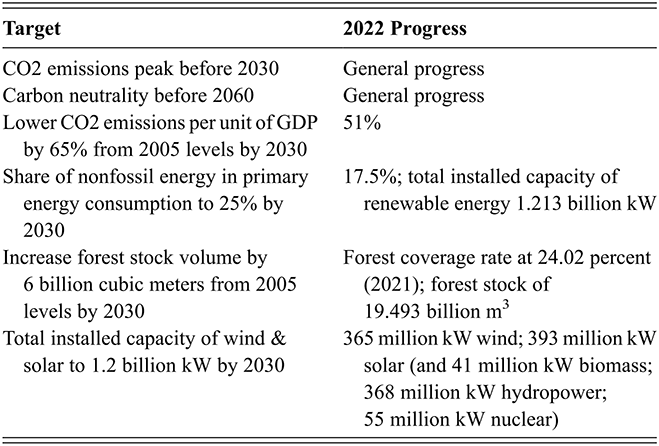

Targets. China continued to elaborate on its system of environmental targets after 2011. The 12th five-year plan (2011–15) contained binding carbon intensity targets for the first time. Environmental and energy targets made up half of all mandatory targets in the 13th five-year plan (2016–20). In 2020, Xi Jinping announced China’s “dual carbon” (shuangtan) targets at the UN General Assembly – goals to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

Implementation Measures. The party and government enacted a host of laws, policies, and enforcement campaigns to promote the achievement of these targets. The national legislature amended the Environmental Protection Law and laws on air pollution, water pollution, solid waste pollution, and marine environmental protection. It passed a new law on soil pollution in 2018. The government launched a much publicized “war on pollution” campaign between 2013 and 2016 to implement pollution action plans for air, water, and soil pollution. The CCP designated pollution control as one of three key governance “battles” (gongjianzhan) in 2017, along with the battle to reduce major risks (huajie zhongda fengxian) and the battle to alleviate poverty (tuopin). China would combine bureaucratic targets and tournament-style competition among officials and jurisdictions, campaign-style enforcement, and a blend of legal, economic, and policy carrots and sticks to drive environmental action.

Institutional Reforms. A range of institutional reforms sought to improve governance and signal the increased priority of environmental protection. Several existing agencies were combined to create the Ministry of Environment & Ecology (MEE) as a “superministry” capable of reducing problems of horizontal fragmentation. Bureaucratic reforms aimed to centralize environmental enforcement through central inspection teams, provincial management of environmental monitoring and inspections, and Party-state joint responsibility. Other measures sought to mobilize the bureaucracy to join in environmental governance through high-level leading groups and the recruiting of banking, securities, and other regulators to enforce environmental rules. Yet others increased public supervision through environmental information disclosure and public interest litigation (Wang Reference Wang2018a, Reference Wang2018b).

2.4 Ecological Civilization as Ideology

The maturation of domestic environmental policies, programs and institutional capacity has contributed to the emergence of an ideology of Chinese global environmentalism that China has begun to deploy globally. This is a top-down, state-led developmental version of environmentalism that is beginning to put pressure on global environmental norms forged in the US and Europe.

Just days before Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping levied a not-so-subtle criticism of the US in a keynote speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos. “As the Chinese saying goes, people with petty shrewdness attend to trivial matters, while people with vision attend to governance of institutions.” Moments later, he added: “We should honor promises and abide by rules … The Paris Agreement is a hard-won achievement which is in keeping with the underlying trend of global development. All signatories should stick to it instead of walking away from it as this is a responsibility we must assume for future generations” (Xi Reference Xi2017).

The remark was a reference to Trump’s campaign promise to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement, and Xi’s point could not have been clearer. China was a responsible nation and a leader on environmental matters. The US was not. Western and Chinese media amplified the message, never mind China’s staggering level of GHG emissions or its continued buildout of coal-fired power plants. This marked an intensification of what former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd has called the “new geopolitics of China’s climate leadership” (Rudd Reference Rudd2020).

The official doctrine of Chinese environmentalism has been elaborated predominantly for China’s domestic context. A 2022 People’s Daily article, for example, spelled out the content of “Xi Jinping Thought on Ecological Civilization” in some detail.Footnote 4 A few things stand out. This is a vision that first and foremost is led by the CCP (rather than the people or private sector). It speaks in civilizational terms; that is, civilizations flourish when ecology flourishes and civilizations have fallen when nature falters. The goal is harmonious coexistence of man and nature, although the exact definition of this remains unclear. This connects Xi Jinping Thought directly to early Chinese notions of “harmony between man and nature” (tianren heyi), “the Way (Tao) follows nature,” (daofa ziran), and “take things in moderation” (quzhi youdu). The environment is a source of economic prosperity. Eco-civilization has a notion of collective justice because a healthy environment contributes to the welfare of all people. Xi Jinping Thought expressly recognizes eco-civilization as a “profound revolution in development concept” and a radical move away from earlier, coarser concepts of development. It includes a specific call for “coordinated management of mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes, grasslands, and sand systems,” which has manifested itself within China in the so-called “ecological redline” (shengtai hongxian) program – a massive nationwide zoning project. It calls for “systems,” “rule of law,” and individual action from Chinese citizens to help implement eco-civilization.

Western scholars have begun to theorize ecological civilization in the Chinese domestic context. For example, Hansen et al. (Reference Hansen2018) write that “[e]co-civilization is best understood as a sociotechnical imaginary … constructed as a … Communist Party led utopia in which market economy and consumption continue to grow, and where technology and science have solved the basic problems of pollution and environmental degradation.” Yeh (Reference Yeh2022) writes that “[a]s an ideological framework, ecological civilization draws selectively on reductionist interpretations of China’s traditional philosophies while maintaining a long-standing focus on economic growth and on the need for scientific and technological solutions to ecological crises … ” Rodenbiker (Reference Rodenbiker2023a) states that “the Chinese state wields ecology to shape nature, society, and space.” Goron (Reference Goron2018) and Geall & Ely (Reference Geall and Ely2018) have made interventions in a similar vein.

On the global stage, the ideology of eco-civilization is arguably even more abstract and inchoate. Quotes attributed to Xi – such as “ecological civilization is the historical trend of the development of human civilization” or “building a green home is the common dream of mankind” – are typical. In 2023, China’s State Council released a white paper entitled China’s Green Development in the New Era, which discussed China’s domestic green development program at length but offered only modest guidance on China’s global green objectives. These included “participating in global climate governance,” “building a green Belt and Road,” and “carrying out extensive bilateral and multilateral cooperation.”

From Chinese statements and actions in these spaces, we can nonetheless divine a few broad themes.

First and foremost, Chinese global environmentalism is a developmental concept. It was initially concerned with environmental limits on development and then evolved into an idea of green development as a vehicle for “higher quality growth.” The “core idea” of Chinese ecological civilization is Xi’s “two mountains theory.” While the concept has some historical resonance within China, its international translation – green is gold – comes across as purely developmental. That is, the environment is a source of prosperity. One high-profile platform for the slogan was a UN Environmental Program (UNEP) report by Chinese authors entitled “Green is Gold: The Strategy and Actions of China’s Ecological Civilization” in which ecological civilization is presented as a Chinese contribution to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UNEP 2016).

Chinese leaders have incorporated this green rhetoric into Xi-era foreign policy language. Thus, Xi has promised to “make green a defining feature of Belt and Road cooperation” (China’s key Xi-era outbound investment strategy) with “cooperation on green infrastructure, green energy and green finance.” Green framings mesh seamlessly with China’s general foreign policy language about promoting a “community of shared destiny” and providing the world with “shared benefits” and “global public goods.” These core concepts are qualified with reference to a hodge-podge of values such as “extensive consultation,” “joint contribution,” “policy coordination,” “infrastructure connectivity,” “unimpeded trade,” “connectivity,” “financial integration,” and “people-to-people bonds.” This is a gauzy invocation of green values as a way to pursue a broader panoply of positive Chinese virtues.

Beyond this, China continues to position itself as a defender of Global South interests and to characterize the country as “the largest developing country in the world” (PRC SCIO 2021a). This includes continued invocation of the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities” and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. These emphasize sovereignty and the right of developing countries to take more time in meeting global environmental goals while also obtaining help from developed nations. These arguments also draw strength from postcolonial discourses that see aspects of Western environmentalism as hypocritical or self-interested (i.e., that Western nations are asking the Global South to “do as we say, not as we do”). Chinese official rhetoric has also begun to emphasize the “civilizational” aspects of Chinese governance through programs like the Global Civilization Initiative, launched in 2023. The ostensible purpose of the initiative is to emphasize the importance of diversity of civilizations and discourses and to suggest that the Western “rules based international order” is only one acceptable approach among others (Xi Reference Xi2023).

Underlying all of this is the notion that the steadying Leviathan of Chinese state power at the helm of a broader Chinese civilization is essential to achieving the utopian, win-win visions of Chinese global environmentalism.

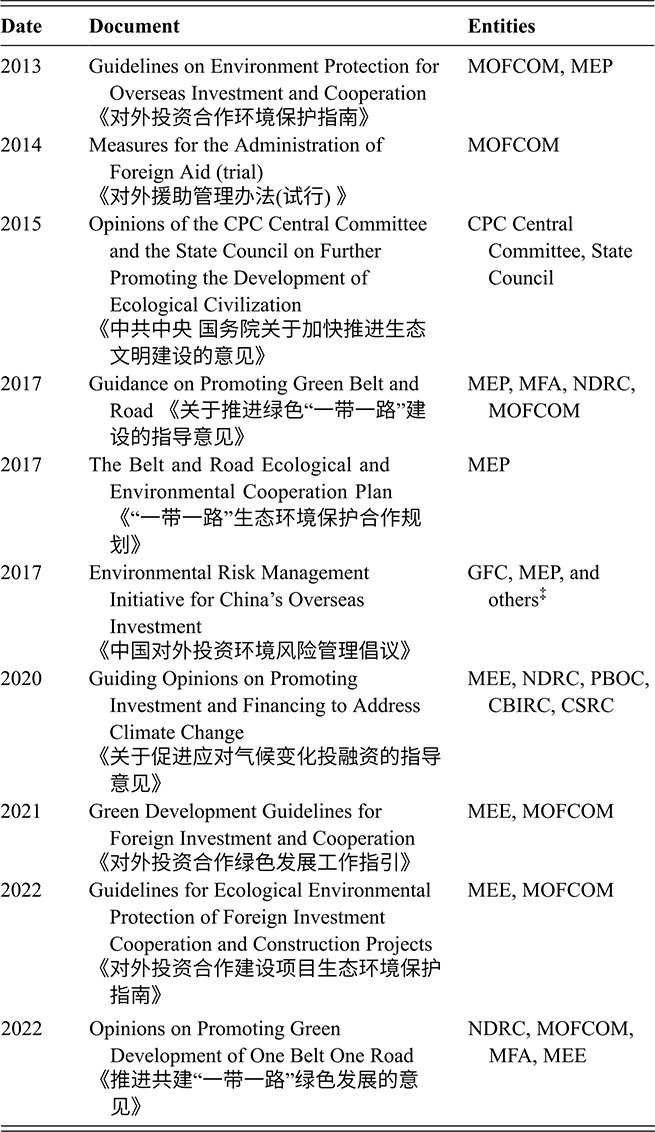

These ideational aspects of Chinese global environmentalism are spelled out in an ever-growing body of policy and guidance documents (Coenen, et al. Reference Coenen, Bager, Meyfroidt, New and Challies2020; Hale, et al. Reference Hale2020; Gallagher & Qi Reference Gallagher and Qi2021). China’s strategic aims for its outbound green activities appeared for the first time in the April 2017 document “Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road,” issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), NDRC, and Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), to promote “the ecological civilization philosophy” and to build a “community with a shared future for mankind.” Key normative documents concerning China’s global environmental governance are listed in Table 2.

† Entity Abbreviations: Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM); Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP, 2008–2018); Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA); National Development & Reform Commission (NDRC); Green Finance Committee (GFC) of China Society for Banking and Finance; People’s Bank of China (PBOC); China Banking & Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC); China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC); and Ministry of Ecology & Environment (MEE, 2018–present).

‡ In addition to the Green Finance Committee (GFC) of China Society for Banking and Finance and the Foreign Economic Cooperation Office (FECO) of MEP, involved entities include the Investment Association of China, China Banking Association, and others.

Table 2Long description

Ten policy documents, dated from 2013 to 2022, are listed in chronological order by issuance date. The three columns list: date, document title (in English and Chinese), and issuing entities. What follows is listed information for each document. Entity name acronyms are explained in a footnote that will be described at the end of this long description.

In 2013, M O F C O M and M E P issued the Guidelines on Environmental Protection for Overseas Investment and Cooperation《对外投资合作环境保护指南》.

In 2014, M O F C O M issued the Measures for the Administration of Foreign Aid (trial)《对外援助管理法(试行) 》.

In 2015, the C P C Central Committee and the State Council issued the Opinions on the C P C Central Committee and the State Council on Further Promoting the Development of Ecological Civilization 《中共中央国务院关于加快推进生态文明建设的意见》.

In 2017, M E P, M F A, N D R C, and M O F C O M issued the Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road 《关于推进绿色“一带一路”建设的指导意见》.

In 2017, M E P issued the The Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan《“一带一路”生态环境保护合作规划》.

In 2017, G F C, M E P, and others issued the Environmental Risk Management Initiative for China’s Overseas Investment《中国对外投资环境风险管理倡议》.

In 2020, M E E, N D R C, P B O C, C B I R C, and C S R C issued the Guiding Opinions on Promoting Investment and Financing to Address Climate Change《关于促进应对气候变化投融资的指导意见》.

In 2021, M E E and M O F C O M issued the Green Development Guidelines for Foreign Investment and Cooperation《对外投资合作绿色发展工作指引》.

In 2022, M E E and M O F CO M issued the Guidelines for Ecological Environmental Protection of Foreign Investment Cooperation and Construction Projects《对外投资合作建设项⽬⽣态环境保护指南》.

In 2022, N D R C, M O F C O M, M F A, and M E E issued the Opinions on Promoting Green Development of One Belt One Road《推进共建“⼀带⼀路”绿⾊发展的意⻅》.

The first footnote lists entity abbreviations: M O F COM is the Ministry of Commerce; M E P is the Ministry of Environmental Protection, which existed from 2008 to 2018; M F A is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; N D R C is the National Development and Reform Commission; G F C is the Green Finance Committee of China Society for Banking and Finance; P B O C is the People’s Bank of China; C B I R C is the China Banking & Insurance Regulatory Commission; C S R C is the China Securities Regulatory Commission; and M E E is the Ministry of Ecology & Environment, which was created in 2018 and still exists as of this writing.

The second footnote notes that the “others” reference for the Environmental Risk Management Initiative for China’s Overseas Investment includes the Investment Association of China, China Banking Association, and others. It also clarifies that the reference to M E P is to the Foreign Economic Cooperation Office (F E C O) of M E P.

The Xi era has also been marked by a growing proliferation of foreign language materials designed to convey Chinese ideas on global environmentalism to international audiences. These ideas are now regularly advanced through leadership speeches at the highest levels, official foreign policy statements, state-run media, and other publications. The four-volume set of Xi Jinping’s speeches, The Governance of China, published between 2013 and 2022, contains more than two dozen speeches on global and domestic environmental matters. The China Pavilion at annual UNFCCC climate negotiations is replete with books such as Xie Zhenhua’s China’s Road of Green Development, and Zhou Dadi’s Toward a Green and Low-Carbon Future: China’s Energy Strategy. The magnum opus of Chinese outbound messaging may be a 775-page English-language edited volume featuring essays from more than 70 leading Chinese scholars and researchers, entitled Beautiful China: 70 Years Since 1949 and 70 People’s Views on Eco-civilization Construction.

Overall, the gist of the message is that China’s approach to governance and its pursuit of its own self-interest will benefit the rest of the world in developmental and environmental terms. The most powerful idea here remains the notion that Chinese governance can deliver outcomes that other systems cannot. The subtext is that a Chinese-style approach to governance – with top-down, technocratic party-state leadership, marketization within bounds, and emphasis of economic over civil rights, among other things – is better suited to deliver these results. While some commentators have argued that China is in a more ideological age with the ascent of Xi Jinping, the global message here is a pragmatic one as old as politics itself – come with me and I will give you the things that you desire.

A central question is what practical role green ideology plays in Chinese global activity. Does it do any real work or is it mere rhetoric? What is clear is that this is a massive effort to transform Chinese thinking about what constitutes “development” and the proper relationship of man and nature. Less resource intensive or polluting forms of growth are now prized in a way that they were not just a few decades ago. Whereas clean technologies are being presented as a “green scam” at the outset of the second Trump administration in the US (US White House 2025), they are seen as desirable “higher quality” development in China (Qiu Reference Qiu2024; People’s Daily 2025). The Chinese ideology also neatly creates a framework for China to take advantage of political economy dynamics that play in the country’s favor. Thus, China is seeking to escape the middle-income trap by aggressively cultivating advanced clean technology industries. This strategy helps to mitigate energy security risks, reduce strains on the environment and public health, and bolster China’s global reputation through contributions to global development and environmental goals. Most of all, it is a strategy for China to capture the benefits of what it sees as an inevitable global transition to clean energy technologies (Boyd Reference Boyd2012).

Yet many questions remain as to what these general principles mean for action on the ground. How will contradictions between man and nature, development and the environment, or China and the rest of the world be resolved in practice? The doctrine of eco-civilization is beginning to have real bite domestically where it is altering China’s economic structure, industrial behavior, and land use patterns. However, there is no guarantee that this will continue, say, if the economy falters or leadership changes. Even if ideology translates into praxis domestically, it is likely to play out differently abroad. Might Chinese green ideology, for example, demand greater ecological protection at home, while tolerating greater environmental impacts globally in the name of development or simply due to weaker global governance capacity or concern?

These are the ideational aspects of Chinese global environmentalism and the questions they raise. Our brief survey here of the ideology of Chinese global environmentalism shows at minimum how China would like the world to understand the country’s push for global green development. Sections 3–5 examine how the other aspects of the Chinese global environmentalism playbook are emerging in practice. We turn first to China’s use of green diplomacy.

3 Green Diplomacy

China’s environmental diplomacy offers a useful lens through which to observe the nuances of Chinese strategy over time. We survey two different treaty contexts: (i) the Montreal Protocol and (ii) the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The Montreal Protocol helps us to understand conditions under which Chinese actors are willing to take on and comply with environmental obligations, both in the initial stages of the treaty’s history and with the more recent Kigali Amendment. In many ways the Montreal Protocol has been a positive story for Chinese green diplomacy and environmental performance. Yet recent enforcement problems with certain banned substances (CFCs and HFC-23) offer a more complex picture – for CFCs, sometimes defensive or combative official Chinese responses, along with aggressive enforcement campaigns that appear to have resolved the problem; for HFC-23, domestic policy responses with incomplete resolution to date of illegal emissions likely emanating from China.