Introduction: beyond technology adoption – reframing AI in entrepreneurship

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognized as a transformative force in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurs are leveraging AI for tasks ranging from product design (Garbuio & Lin, Reference Garbuio and Lin2019) and customer engagement (Chatterjee, Rana, Tamilmani & Sharma, Reference Chatterjee, Rana, Tamilmani and Sharma2021), to funding evaluation (Pumplun, Fecho, Wahl, Peters & Buxmann, Reference Pumplun, Fecho, Wahl, Peters and Buxmann2021) and market intelligence (Fountaine, McCarthy & Saleh, Reference Fountaine, McCarthy and Saleh2019). This growing integration of AI into entrepreneurial processes reflects broader trends in digitalization and data-driven decision-making that are reshaping the nature and pace of venture creation (Neumann, Guirguis & Steiner, Reference Neumann, Guirguis and Steiner2024). Beyond operational efficiency, AI is progressively shaping how entrepreneurs interpret information, evaluate opportunities, and make strategic judgments under uncertainty. As a result, scholarly interest at the intersection of AI and entrepreneurship has expanded rapidly over the past decade, producing a diverse and increasingly fragmented body of research. Despite this momentum, the academic literature on AI in entrepreneurship remains conceptually fragmented and dominated by technocentric perspectives. A large proportion of studies focus on technology adoption (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Rana, Tamilmani and Sharma2021; Vedapradha, Gupta & Sharma, Reference Vedapradha, Gupta and Sharma2024), digital transformation (Mikalef & Gupta, Reference Mikalef and Gupta2021), or firm-level performance (Delen, Kuzey & Uyar, Reference Delen, Kuzey and Uyar2013), often drawing on models such as TAM or UTAUT. While these frameworks are valuable for explaining adoption intentions, they offer limited insight into the cognitive mechanisms through which entrepreneurs engage with AI-enabled information. These models, while analytically useful, tend to oversimplify the entrepreneurial context, neglecting how AI is actually interpreted, trusted, or resisted by entrepreneurs (Andrade-Valbuena, Olavarrieta & Torres, Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Olavarrieta and Torres2024; Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Mohseni, Najafi & Nilashi, Reference Mohseni, Najafi and Nilashi2021).

In particular, the literature pays limited attention to the cognitive (how entrepreneurs process and evaluate AI-generated outputs), emotional (how confidence, anxiety, or trust shape engagement), and interpretive (how meaning is constructed from algorithmic recommendations) processes through which entrepreneurs engage with AI. Constructs such as opportunity confidence (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Olavarrieta and Torres2024; Haynie, Shepherd, Mosakowski & Earley, Reference Haynie, Shepherd, Mosakowski and Earley2009), algorithmic aversion (Dietvorst, Simmons & Massey, Reference Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey2015), and mental modeling (Weick, Reference Weick1995) are seldom applied to this domain, even though entrepreneurial decision-making often unfolds under uncertainty and incomplete information (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Simon, Reference Simon1947). This omission represents a critical theoretical gap, given that AI increasingly acts as a decision-shaping technology rather than a neutral analytical tool. As a consequence, existing frameworks struggle to explain why entrepreneurs facing similar AI technologies frequently arrive at divergent judgments and decisions. This cognitive blind spot reduces the explanatory power of existing frameworks and limits their ability to account for heterogeneity in entrepreneurial responses to AI. In this article, these cognitive, emotional, and interpretive elements do not operate as empirically measured constructs; rather, they function as conceptual lenses that guide our synthesis of the literature and structure our assessment of how entrepreneurs engage with AI-mediated decision environments.

Rather than attributing this fragmentation to a lack of empirical evidence, this study argues that it reflects the absence of an integrative theoretical synthesis capable of linking technological, cognitive, and contextual perspectives on AI-enabled entrepreneurship. Against this backdrop, this study addresses a fundamental question: how has existing research conceptualized the relationship between AI and entrepreneurial decision-making, and how can these fragmented perspectives be systematically integrated into a coherent explanatory framework?

To address these gaps, this article systematically maps the intellectual structure of the AI–entrepreneurship literature and develops an integrative synthesis that connects dominant research streams with their underlying theoretical assumptions. Rather than empirically modeling entrepreneurs’ cognitive processes, the study adopts a hybrid review design that combines bibliometric co-word analysis with qualitative thematic synthesis to examine how existing research conceptualizes AI and entrepreneurial decision-making. Using a systematically curated corpus of 372 peer-reviewed articles indexed in the WoS Core Collection between 2001 and 2025, we conduct a co-word analysis and thematic mapping to identify dominant research streams, theoretical disconnections, and conceptual absences across levels of analysis.

This integrative approach allows the review to reconstruct the conceptual architecture of the field rather than merely cataloging prior findings. Specifically, the analysis identifies four thematic quadrants – core entrepreneurial applications, transversal foundations, isolated specializations, and peripheral or emerging futures – providing a structured representation of how AI has been theorized in relation to entrepreneurial processes (Callon, Courtial & Laville, Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991; Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma & Herrera, Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011). By explicitly linking these quadrants to the presence – or absence – of cognitively informed theorizing, the review clarifies where cumulative theory building is occurring and where important conceptual gaps remain.

This article makes three key contributions. First, it provides a systematic overview of thematic fragmentation, showing that even high-frequency themes like digital innovation and performance often lack deep conceptual integration (Cho, Lee & Lee, Reference Cho, Lee and Lee2023; Tominc, Rebernik & Rus, Reference Tominc, Rebernik and Rus2024). Second, it demonstrates that the literature remains largely anchored in instrumental and techno-centric perspectives, with limited engagement with theories of entrepreneurial cognition, judgment, and interpretation. As a result, constructs central to entrepreneurial decision-making are often overlooked in favor of structural or functional explanations of technology use (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Trope & Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010). Third, building on these insights, it proposes a five-part research agenda focused on cognitive framing, human–AI interaction, inclusion and ethics, methodological pluralism, and the integration of behavioral theory into AI tool design and usage (Grandori, Reference Grandori2020; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011).

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the review methodology and thematic mapping approach. Section 3 presents the descriptive mapping of the field. Section 4 develops the thematic landscape across four quadrants. Section 5 provides a cross-quadrant integrative discussion that connects these quadrants to theoretical, methodological, and cognitive gaps. Section 6 offers a forward-looking research agenda centered on cognitive mechanisms. Section 7 concludes with theoretical contributions and implications for future research.

Methodology: systematic review and thematic mapping of AI–entrepreneurship literature

Research design and review protocol

This study adopts a hybrid literature review design that integrates bibliometric mapping with qualitative thematic synthesis. Rather than estimating effect sizes or conducting a meta-analysis, the objective is to combine a quantitative mapping of the intellectual structure of the field with a theoretically informed interpretation of its dominant and peripheral themes. Hybrid review designs of this kind are increasingly recommended for synthesizing complex and fragmented bodies of literature, particularly in management and entrepreneurship research where conceptual heterogeneity limits the applicability of purely quantitative aggregation techniques (Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey & Lim, Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015). This approach is particularly suitable for emerging and fragmented research domains, such as the intersection of AI and entrepreneurship, where constructs, methods, and levels of analysis remain heterogeneous.

Procedurally, the review follows the SPAR-4-SLR protocol (Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews) proposed by Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani (Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021), which was specifically developed for systematic reviews in business and management research. SPAR-4-SLR structures the review process into three interrelated stages: Assembling, which involves defining the research domain, research questions, source quality, and data acquisition; Arranging, which focuses on screening, organizing, and refining the corpus through explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria; and Assessing, which encompasses the analytical evaluation of the literature and the transparent reporting of findings and future research directions (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). The adoption of SPAR-4-SLR enhances methodological transparency, replicability, and coherence across review stages, addressing common limitations identified in prior review studies (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). The overall review process is summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. SPAR-4-SLR review protocol and analytical workflow.

Data collection and search strategy

Data collection was conducted using the WoS Core Collection, which was selected due to its recognized selectivity, rigorous indexing standards, and suitability for bibliometric analysis (Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl & Olavarrieta, Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019). WoS is widely used in bibliometric and systematic review studies in management and entrepreneurship because it provides standardized metadata, high-quality journal coverage, and compatibility with advanced bibliometric techniques (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015).

To ensure comprehensive coverage of the AI–entrepreneurship domain, the search strategy followed an iterative two-step process, as recommended for emerging and conceptually heterogeneous research fields (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021).

First, an exploratory search was conducted using broad keywords related to AI and entrepreneurship. Preliminary search terms included ‘Artificial Intelligence’, ‘AI’, and ‘Entrepreneurship’. The resulting records were exported to VOSviewer to conduct an initial co-occurrence analysis of keywords. This exploratory mapping enabled the identification of recurrent and conceptually relevant terms used within the literature and supported the refinement of the final search strategy. Such iterative refinement procedures are consistent with best practices in bibliometric content analysis, particularly when addressing terminological dispersion and conceptual ambiguity (Andrade-Valbuena, Baier-Fuentes & Gaviria-Marín, Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Baier-Fuentes and Gaviria-Marín2022; Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011; Klarin, Reference Klarin2024).

Based on this exploratory phase, the final search string was defined as follows:

(‘Artificial Intelligence*’ OR ‘Machine Learning*’ OR ‘Deep Learning*’ OR ‘Natural Language Processing*’) AND (‘Entrepreneur*’ OR ‘Startup*’ OR ‘New Venture*’).

The refined search was applied to the WoS Core Collection, specifically within the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED) and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), ensuring coverage of high-impact journals in both technological and entrepreneurial research domains (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019).

Screening and corpus definition

The refined search was limited to publications categorized under Management, Business, Operations Research & Management Science, and Business Finance. Document types were restricted to Research Articles, Review Articles, Early Access articles, and Proceedings Papers. The temporal scope covered publications from 2001 to 2025. This search yielded an initial corpus of 933 documents.

The screening and eligibility assessment were conducted using Rayyan, a web-based application designed to support systematic literature reviews through collaborative and blinded screening procedures (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz & Elmagarmid, Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016). Rayyan has been widely adopted in systematic reviews due to its capacity to enhance transparency, reduce selection bias, and facilitate consensus-building among reviewers (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). Each publication was evaluated based on its title, keywords, and abstract to assess relevance to both AI (or closely related techniques such as machine learning, deep learning, or natural language processing) and entrepreneurial phenomena, including startups, new ventures, entrepreneurial ecosystems, or opportunity-related processes.

Publications focusing on general innovation or management topics without explicit reference to AI were excluded due to insufficient alignment with the research scope. Ambiguous cases were discussed jointly by the reviewers until consensus was reached, thereby enhancing methodological rigor and inter-reviewer reliability, as recommended in systematic review protocols (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). Following this screening process, the corpus was reduced to 372 documents, which formed the empirical basis for both the bibliometric mapping and the subsequent thematic synthesis. Descriptive statistics of the final corpus are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the final corpus

Bibliometric and thematic analysis

Bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Bibliometrix package and its graphical interface, Biblioshiny, implemented in R version 4.3.2 (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). Biblioshiny enables the execution of bibliometric analyses without programming while providing dedicated modules for defining analytical fields, setting frequency thresholds, applying clustering algorithms, and generating thematic and temporal maps. This platform has been widely adopted in management and entrepreneurship research for mapping intellectual structures and identifying thematic patterns in large bodies of literature (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015).

Author Keywords were used as the analytical unit to enhance internal validity and ensure that the resulting thematic structures reflected authors’ conceptual framing of the field. Prior to analysis, a customized thesaurus was manually developed to harmonize terminology, consolidate orthographic variants, and unify acronyms across the corpus, thereby reducing noise in the co-word network and improving interpretability.

In the first stage, a co-word analysis was performed based on Author Keywords, as keywords capture authors’ intentional conceptual positioning within a research domain (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991; Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011). A co-occurrence matrix was constructed by applying a minimum threshold of three co-occurrences, thereby focusing the analysis on recurrent and conceptually meaningful terms. The matrix was normalized using the association strength index, which is commonly recommended to control for differences in keyword frequency and enhance comparability across themes (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2009).

A co-word approach was preferred over co-citation analysis because AI–entrepreneurship constitutes an emerging and conceptually heterogeneous research field. In such contexts, citation networks tend to be relatively sparse and conceptually lagged, whereas keywords provide a more direct representation of contemporaneous thematic proximities and evolving research agendas (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991; Klarin, Reference Klarin2024).

Based on the normalized co-word network, a thematic map was generated using the centrality–density framework proposed by Callon et al. (Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991), which allows for the classification of themes into motor themes, basic and transversal themes, emerging or declining themes, and peripheral topics.

To identify coherent thematic clusters, the Louvain community detection algorithm was applied to the normalized network. This algorithm optimizes modularity by grouping keywords that co-occur more intensively with one another than with the rest of the network, thereby revealing clusters that can be interpreted as thematically coherent research streams. Louvain-based clustering is widely used in bibliometric research due to its efficiency and robustness in detecting community structures in large-scale networks (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017; Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte & Lefebvre, Reference Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte and Lefebvre2008).

Clusters were generated algorithmically through modularity optimization and subsequently interpreted through an iterative validation process. This involved examining dominant keywords, representative articles, and the conceptual coherence of each cluster before assigning final thematic labels. Accordingly, the identified clusters should be interpreted as thematic configurations reflecting patterns of conceptual co-occurrence, rather than as causal or process-based models.

In addition, the temporal evolution of themes was analyzed using the ‘Thematic Evolution’ module in Biblioshiny. The observation period was divided into three sub-periods (2010–2020, 2021–2023, and 2024–2025), enabling examination of how thematic clusters emerged, persisted, or transformed over time within the AI–entrepreneurship literature. Temporal thematic analysis is particularly suitable for capturing shifts in research focus and conceptual development in rapidly evolving domains (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019; Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011).

Qualitative thematic synthesis and robustness

Following the bibliometric mapping, a qualitative thematic synthesis was conducted to interpret the identified clusters in greater depth. This synthesis followed an inductive–deductive approach, whereby core articles within each cluster were systematically reviewed to refine thematic labels, interpret conceptual boundaries, and identify dominant assumptions and theoretical orientations. Such hybrid interpretive strategies are commonly recommended in bibliometric reviews to complement quantitative mapping with theoretically informed sensemaking and to avoid purely descriptive interpretations of clusters (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991; Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). Iterative discussions among the reviewers supported the validation and adjustment of thematic interpretations, thereby enhancing analytical rigor and reflexivity.

To enhance robustness and transparency, a customized thesaurus was manually prepared to normalize terminology, integrate spelling alternatives, and standardize acronyms within the dataset. This preprocessing step is consistent with best practices in co-word analysis, as variations in terminology and acronyms can introduce artificial fragmentation and noise in semantic networks (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017; Klarin, Reference Klarin2024). By reducing semantic dispersion, this procedure strengthened the interpretability and internal coherence of the resulting thematic structures.

While this hybrid approach offers a comprehensive and structured overview of the AI–entrepreneurship literature, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Bibliometric analyses are inherently dependent on the quality and scope of the underlying database, and this study is restricted to WoS-indexed publications and English-language articles. As noted in prior reviews, such constraints may lead to the exclusion of relevant contributions published in other databases or linguistic contexts (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). These limitations are revisited in the concluding section.

Results: bibliometric and thematic structure of AI–entrepreneurship research

Historical roots and intellectual trajectory of the field

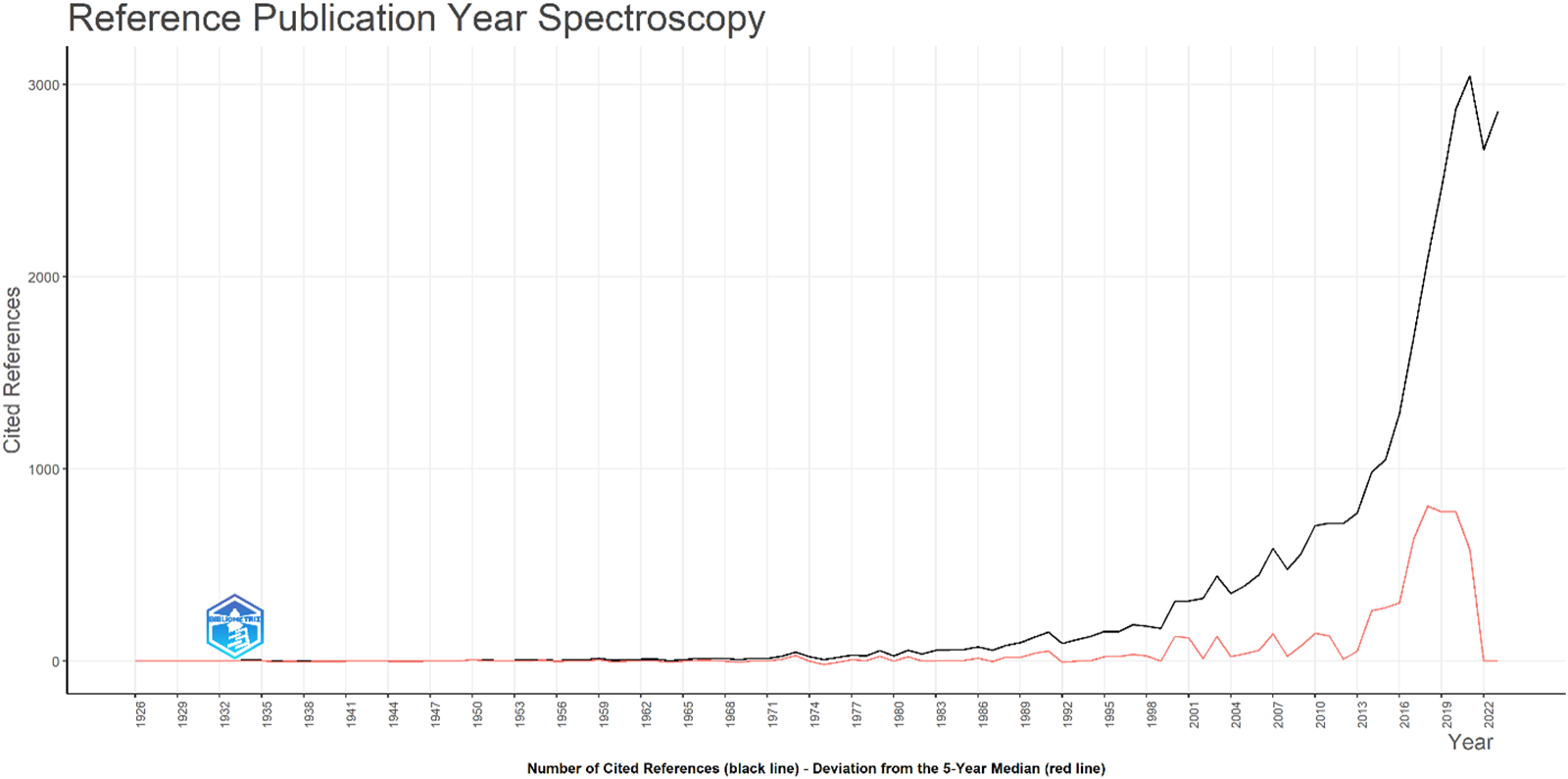

To identify the historical foundations of AI–entrepreneurship research, a Reference Publication Year Spectroscopy (RPYS) analysis was conducted. RPYS enables the detection of influential publication years by examining the temporal distribution of cited references and identifying peaks associated with seminal works that have shaped the development of a research field (Marx, Gans & Hsu, Reference Marx, Gans and Hsu2014; Thor, Bornmann & Marx, Reference Thor, Bornmann and Marx2016). This technique has been widely applied to uncover the intellectual roots and formative knowledge bases of emerging and interdisciplinary research domains.

As shown in Fig. 2, the citation landscape remains relatively flat until the mid-2010s, indicating limited consolidation during the early stages of the field. From approximately 2016 onwards, citation intensity increases markedly, with a pronounced acceleration after 2020. Similar temporal patterns have been observed in other technology-driven research domains, where early exploratory phases are followed by rapid expansion once enabling technologies mature and diffuse across applied contexts (Ardito, Scuotto, Del Giudice & Petruzzelli, Reference Ardito, Scuotto, Del Giudice and Petruzzelli2019). This pattern suggests that AI–entrepreneurship research has transitioned from a nascent and exploratory phase to a period of rapid expansion and conceptual diversification.

Figure 2. Reference Publication Year Spectroscopy (RPYS) of AI–entrepreneurship research.

The RPYS curve shows a gradual increase in cited references up to the early 2000s, followed by a sharp rise from around 2015 onward. This pattern indicates that much of the intellectual influence shaping AI–entrepreneurship research derives from relatively recent publications, coinciding with the broader acceleration of AI and data-driven innovation. Consistent with prior observations that entrepreneurship research frequently draws on advances generated in adjacent disciplines (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019; McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Shane & Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000), the concentration of influential references in this period suggests that developments in AI, innovation management, and information systems have increasingly informed entrepreneurial inquiry.

Rather than revealing a single, stable foundational canon, the RPYS distribution points to the progressive consolidation of AI-related scholarship as a core reference base for entrepreneurship research. Overall, the results highlight both the recency and the cross-disciplinary nature of the knowledge on which AI–entrepreneurship currently builds, providing historical context for the thematic structures and conceptual imbalances identified in the subsequent analyses.

Thematic landscape of AI–entrepreneurship research

To examine the conceptual structure of the field, a thematic map was generated based on the co-word analysis described in Section 2.4, using the centrality–density framework proposed by Callon et al. (Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991). This approach positions themes according to two structural dimensions: internal cohesion (density) and degree of interaction with other themes in the field (centrality). As such, the thematic map provides a relational representation of how concepts co-occur within the literature, rather than a causal or process-based model of relationships.

The thematic structure visualized in Fig. 3 is derived from the application of the Louvain community detection algorithm to the normalized keyword co-occurrence network. Each cluster represents a group of Author Keywords that frequently co-occur across publications, reflecting shared conceptual emphases within the AI–entrepreneurship literature. The centrality–density framework has been widely applied in bibliometric studies to assess thematic development and structural positioning within research fields (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011).

Figure 3. Thematic landscape of AI–entrepreneurship research generated with Biblioshiny (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017) and adapted by the authors.

The resulting thematic map, presented in Fig. 3, reveals four distinct thematic quadrants that characterize AI–entrepreneurship research.

Themes located in the upper-right quadrant (high centrality–high density) represent the core of the field. These themes are both conceptually well developed and highly interconnected with other research streams. In this map, this quadrant is dominated by research on technological innovation, fintech, and – more recently – generative AI and large language models. These themes primarily relate to AI-enabled value creation, digital business models, and performance outcomes, reflecting a strong emphasis on functional and application-oriented uses of AI within entrepreneurial and organizational contexts. Similar concentrations of performance-focused themes have been observed in other technology-driven management domains, where empirical expansion often precedes deeper theoretical integration (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021).

The upper-left quadrant (low centrality–high density) contains well-developed but relatively isolated themes. These topics exhibit strong internal coherence but limited integration with the broader thematic structure of the field. In the present analysis, these niche clusters include ecosystem-oriented perspectives, sustainability-focused entrepreneurship, and cognitive–strategic lenses such as effectuation, causation, and uncertainty. This pattern suggests parallel research streams that evolve independently from the dominant core, a configuration frequently associated with thematic specialization in fragmented and rapidly evolving fields (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011).

Themes located in the lower-right quadrant (high centrality–low density) correspond to transversal and foundational topics that connect multiple research areas but remain conceptually underdeveloped. This quadrant is characterized by broad constructs such as AI, digital transformation, dynamic capabilities, and digital entrepreneurship – often anchored in systematic literature reviews and conceptual work. While such themes are widely referenced across studies, their low density indicates limited theoretical elaboration or integration. This configuration is characteristic of bridging themes that serve as common reference points across the literature without constituting fully consolidated research streams (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015).

Finally, the lower-left quadrant (low centrality–low density) captures peripheral and emerging themes. These topics are weakly developed and marginally connected to the core literature. In this map, this quadrant includes machine learning, natural-language processing, and crowdfunding, reflecting early-stage – and often method-driven – applications of AI to entrepreneurial finance and digital platforms. Such peripheral positioning is typical of nascent themes that have yet to be systematically theorized or empirically consolidated within a research field (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011).

Temporal evolution of research themes

To complement the static thematic map, the temporal evolution of themes was examined using the ‘Thematic Evolution’ module in Biblioshiny. This technique allows the longitudinal tracking of how thematic clusters emerge, persist, or diverge across different time periods, and is commonly used to identify structural changes in evolving research domains (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017; Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011). For this analysis, the observation window was divided into three sub-periods (2010–2020, 2021–2024, and 2025–2026), allowing for a fine-grained exploration of thematic shifts over time. The resulting structure is presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Thematic evolution of AI–entrepreneurship research across time periods.

In the earliest period (2010–2020), the thematic landscape is dominated by broad technological categories – particularly AI, innovation, and machine learning. These themes appear as relatively undifferentiated and weakly connected clusters, reflecting an exploratory stage in which AI is primarily conceptualized as a general technological capability rather than being embedded within specific entrepreneurial processes. During this phase, explicitly entrepreneurial constructs remain largely implicit and are often incorporated within broader innovation and technology-management discussions, a pattern commonly observed in the early stages of knowledge development in emerging technological fields (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019).

A clearer thematic differentiation becomes visible in the intermediate period (2021–2024). Machine-learning remains a central node but becomes increasingly linked to more application-oriented themes such as digitalization, venture capital, crowdfunding, and bibliometric analysis. At the same time, AI operates as a transversal category that connects technological progress with managerial and entrepreneurial discourse. This configuration indicates a phase of thematic consolidation in which AI is progressively framed not only as a technical tool but also as a strategic enabler of new entrepreneurial initiatives, financing mechanisms, and innovation-driven business models. Similar consolidation patterns have been documented in other technology-intensive research fields, where initial technological experimentation is followed by contextualization within specific organizational and strategic domains (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011).

The most recent period (2025–2026) is characterized by further specialization and conceptual refinement. Machine-learning persists as a stable and recurrent theme across periods, while new clusters – including generative AI, textual analysis, dynamic capabilities, technological innovation, and digital transformation – emerge with increasing clarity. These developments suggest a transition toward more sophisticated analytical techniques and toward theoretically informed perspectives that view AI as a capability integrated into entrepreneurial strategy, opportunity development, and innovation management. At the same time, innovation-oriented themes remain present, although their connections become more differentiated and distributed across AI-related applications rather than concentrated within a single overarching node.

Overall, the temporal evolution reveals a progressive shift from broad, technology-centered discussions toward more context-specific, analytically nuanced, and entrepreneurship-focused accounts of AI. This trajectory reflects both thematic maturation and a closer alignment between technological advances in AI and theoretically grounded inquiry within entrepreneurship research.

Summary of bibliometric findings

Taken together, the bibliometric results depict a research field that has expanded rapidly in recent years, accompanied by growing thematic diversity and a strong technological orientation. These patterns are consistent with other emerging, technology-driven research domains, where early growth is often accompanied by conceptual dispersion and parallel streams of inquiry (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). Within this landscape, AI–entrepreneurship research displays a recognizable core centered on innovation, digitalization, machine learning, and performance-oriented applications. However, the thematic map and temporal evolution analysis also reveal persistent fragmentation and uneven integration across research clusters.

Despite the increasing sophistication of AI-related methods and applications, the evidence indicates that theoretical integration has not progressed at the same pace as technological development. In particular, there is limited cross-fertilization between technologically anchored themes and research grounded in behavioral, cognitive, or entrepreneurship theory. This pattern mirrors observations in adjacent digital entrepreneurship and innovation literatures, where technologically driven conversations frequently evolve separately from theory-building traditions (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011; Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova & Invernizzi, Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022).

Most notably, constructs related to entrepreneurial cognition, judgment, interpretation, and decision-making remain weakly connected to dominant AI-related themes. Although these constructs are central to understanding how entrepreneurs evaluate AI-enabled information, manage uncertainty, and form opportunity-related beliefs, they occupy a marginal position within the current thematic structure. This disconnect suggests the existence of a structural cognitive gap in the intellectual organization of the field.

These patterns provide the empirical foundation for the integrative synthesis and research agenda developed in the following sections, which seek to more explicitly connect AI-focused research in entrepreneurship with theory-informed perspectives on how entrepreneurial actors interpret and engage with AI in practice.

Quadrant-specific thematic synthesis

Building on the thematic map in Fig. 3, this subsection provides a quadrant-specific synthesis of the main themes identified in the co-word analysis. Whereas Section 3 described the structural positioning of clusters in terms of centrality and density, here we qualitatively interpret the substantive content of each quadrant by examining representative articles and recurring conceptual patterns. This quadrant-level synthesis complements the cross-quadrant discussion that follows by clarifying what kinds of questions, methods, and assumptions dominate within each thematic area.

Core entrepreneurial applications (motor themes)

Motor themes occupy the upper-right quadrant of the thematic map and represent the most mature and influential research streams at the intersection of AI and entrepreneurship. These themes combine high centrality and high internal coherence, meaning that they both structure the field and show sustained theoretical and empirical development. Within this quadrant, AI is predominantly conceptualized as a strategic and operational capability that enhances innovation, digital transformation, value creation, and firm performance.

Early contributions in these clusters emphasized how AI-enabled analytics and related digital technologies strengthen strategic renewal, product innovation, and competitive positioning in entrepreneurial firms and digital ventures, particularly through data-driven decision-making and platform-mediated business models (Kohli & Melville, Reference Kohli and Melville2019; Zhai, Yang, Chen & Zhang, Reference Zhai, Yang, Chen and Zhang2023). Sector-specific work further illustrates how AI is embedded within broader digital transformation initiatives and Industry 4.0 infrastructures, reshaping opportunity spaces and entrepreneurial models in areas such as transport and logistics (Popkova, Sergi & Rzaev, Reference Popkova, Sergi and Rzaev2021).

More recent research frames AI explicitly as a firm-level strategic orientation and capability. Studies on AI orientation in entrepreneurial firms, for instance, show that AI-oriented strategies foster broader and deeper collaboration across value chains and are positively associated with internationalization and performance outcomes (Wang, Pan & Wang, Reference Wang, Pan and Wang2025). Complementary evidence indicates that AI orientation can enhance operational efficiency, although these benefits depend on broader strategic conditions and environmental dynamism (Li, Liu & Zhou, Reference Li, Liu and Zhou2020; Li, Ring, Jin & Bajaba, Reference Li, Ring, Jin and Bajaba2025). Taken together, this work portrays AI as an integral element of dynamic capabilities that enable experimentation, process optimization, and market expansion in entrepreneurial settings.

A defining characteristic of the most recent wave of work in these core clusters is the explicit examination of generative AI and large language models as operational tools within entrepreneurial processes. Empirical research documents a ‘double-edged sword’ pattern: generative AI can heighten opportunity recognition and digital entrepreneurial intention, while also increasing overload and dependence risks if not carefully managed (Nguyen, Nguyen, Le, Duong & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Le, Duong and Nguyen2025). Related studies using stimulus–organism–response perspectives show that tools such as ChatGPT enhance entrepreneurial knowledge, opportunity recognition, and digital self-efficacy, reinforcing entrepreneurial intentions among nascent entrepreneurs and students (Duong & Nguyen, Reference Duong and Nguyen2024). These studies move beyond abstract references to ‘AI’ and begin to unpack concrete usage patterns of GenAI in ideation, problem-solving, and venture development.

Parallel research streams within these motor themes focus on AI as a knowledge and learning infrastructure inside organizations, highlighting its role in knowledge discovery, recombination, and decision support. AI systems are shown to augment human and structural capital by enhancing search, pattern recognition, and learning processes, with positive implications for innovation and strategic alignment in entrepreneurial and SME contexts (Chatti & Argoubi, Reference Chatti and Argoubi2025; Popkova et al., Reference Popkova, Sergi and Rzaev2021; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Yang, Chen and Zhang2023).

Across these studies – both foundational and contemporary – AI is consistently positioned as a strategic and operational enhancer of entrepreneurial activity. Methodologically, the literature in this quadrant is dominated by quantitative approaches such as panel regressions, PLS-SEM, large-scale bibliometric mapping, and increasingly hybrid machine-learning methods (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Liu and Zhou2020, Reference Li, Ring, Jin and Bajaba2025; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan and Wang2025; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Yang, Chen and Zhang2023). Theoretically, the cluster is anchored in dynamic capabilities, digital transformation, firm-performance logics, and entrepreneurial orientation, while cognitive and behavioral perspectives on entrepreneurial judgment remain comparatively under-represented.

Thus, while motor-theme research convincingly demonstrates that AI improves efficiency, flexibility, innovation capability, and growth in entrepreneurial settings, it largely assumes – rather than explicitly examines – the cognitive and affective processes through which entrepreneurs interpret, trust, evaluate, and appropriate AI-enabled tools. The microfoundations of judgment, belief formation, learning, meaning-making, and emotional regulation therefore remain only partially theorized. This omission creates a natural bridge to the cognitively informed research agenda developed in Section 6.

Transversal foundations (basic themes)

The lower-right quadrant contains basic themes that exhibit high centrality but relatively low internal density. These clusters provide transversal conceptual foundations for the field by articulating broad constructs such as AI, AI capability, machine learning, big data, digital transformation, and digital entrepreneurship, which cut across multiple research streams. Because these topics operate as shared reference points rather than self-contained research niches, they are widely cited but remain theoretically under-consolidated (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017; Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015).

A substantial share of the work in this quadrant is conceptual, integrative, or review-based. Studies on digital transformation and AI capability, for instance, synthesize how AI-enabled analytics and data infrastructures contribute to value creation and competitive advantage across organizational contexts, including entrepreneurial settings (Kohli & Melville, Reference Kohli and Melville2019; Wamba, Akter, Bresciani & Rahman, Reference Wamba, Akter, Bresciani and Rahman2021; Mikalef & Gupta, Reference Mikalef and Gupta2021). Similarly, reviews of digital entrepreneurship and AI-enabled business transformation map how platformization, analytics, and automation reshape business models and innovation processes, without necessarily focusing on individual entrepreneurial judgment or decision-making (Kraus, Palmer, Kailer, Kallinger & Spitzer, Reference Kraus, Palmer, Kailer, Kallinger and Spitzer2021; Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Yang, Chen and Zhang2023).

Other contributions in this quadrant comprise bibliometric syntheses and technology-domain mappings – for example, work on robotic process automation, AI-driven retail interactions, and AI strategy – which catalogue emerging themes, methodological patterns, and technological trajectories relevant to entrepreneurship and innovation (Fernandez, Uman, Yadav & Hernandez, Reference Fernandez, Uman, Yadav and Hernandez2024; Kraus, Pereira, Corvello, Zardini & Bresciani, Reference Kraus, Pereira, Corvello, Zardini and Bresciani2024; Marinova, de Ruyter, Huang, Meuter & Challagalla, Reference Marinova, de Ruyter, Huang, Meuter and Challagalla2022; Patil, Kamble, Belhadi & Sharma, Reference Patil, Kamble, Belhadi and Sharma2023). These publications play a boundary-spanning role, translating developments in AI, analytics, and digital infrastructures into the language of management and entrepreneurship research.

Taken together, these basic themes serve as the horizontal scaffolding of the field: they establish terminology, delineate broad research gaps, and connect AI to digital transformation, innovation management, and strategic renewal. However, because of their breadth and orientation toward synthesis rather than micro-level theorizing, they seldom develop deep, internally coherent sub-streams. As a result, entrepreneurs often appear as generalized ‘users’ of AI-enabled systems rather than as agents whose beliefs, heuristics, and mental models mediate technology effects, leaving cognitive and behavioral mechanisms largely implicit.

Isolated specializations (niche themes)

Niche themes occupy the upper-left quadrant of the thematic map. They are dense but peripheral: internally cohesive research streams that demonstrate strong conceptual or methodological development, yet remain only weakly connected to the core conversations structuring AI–entrepreneurship research. In this quadrant, AI is typically applied as an analytic, predictive, or classificatory tool within specific entrepreneurial contexts, rather than examined as a broader sociotechnical or cognitive phenomenon.

A particularly prominent and rapidly maturing niche concerns AI-enabled analysis of entrepreneurial finance and crowdfunding. Studies in this stream employ techniques such as natural-language processing, topic modeling, computer vision, and multimodal learning to examine how textual, visual, and behavioral cues shape funding outcomes. For example, research on speech-act portfolios in crowdfunding narratives shows that entrepreneurs who vary the communicative acts embedded in their campaign text achieve greater funding success (Oo, Jiang, Sahaym, Parhankangas & Chan, Reference Oo, Jiang, Sahaym, Parhankangas and Chan2023). Multimodal approaches demonstrate that combining textual, linguistic, and visual features through machine-learning architectures substantially improves the prediction of crowdfunding performance relative to traditional venture characteristics (Kaminski & Hopp, Reference Kaminski and Hopp2020). Other work shows that entrepreneurs’ facial trustworthiness – quantified through ML-based facial-detection systems – is positively associated with pledge amounts and backer participation, with stronger effects observed among female entrepreneurs (Duan, Hsieh, Wang & Wang, Reference Duan, Hsieh, Wang and Wang2020).

A related specialization applies AI-driven topic modeling and text analytics to token-based entrepreneurial finance and blockchain ecosystems. For instance, analyses of security-token-offering (STO) white papers identify thematic structures – such as environmental and healthcare orientation – that are systematically associated with funding success, highlighting the informational role of AI-assisted disclosure analysis in highly uncertain digital investment markets (Bongini, Osborne, Pedrazzoli & Rossolini, Reference Bongini, Osborne, Pedrazzoli and Rossolini2022).

Other niche AI–entrepreneurship applications also appear as distinct but relatively unconnected clusters. One focuses on algorithmic bias and gendered experiences of AI systems, using natural-language processing of large-scale social-media data to uncover how women discuss and contest unfair AI outcomes – including those affecting entrepreneurial work and digital labor participation (Fraile-Rojas, De-Pablos-Herdero & Méndez-Suárez, Reference Fraile-Rojas, De-Pablos-Herdero and Méndez-Suárez2025). Another examines AI-based credit-scoring and fintech lending, developing enhanced classification models to address unstable or imbalanced datasets in startup-lending contexts and showing that modified binning approaches can improve both predictive stability and interpretability (Anggodo & Girsang, Reference Anggodo and Girsang2024). Additional studies explore AI-enabled business-model development and service innovation in healthcare and technology-intensive entrepreneurship, where big-data, IoT, or automation technologies reshape reliability management and value creation.

Across these streams, the empirical emphasis lies on signal extraction and predictive accuracy, often using platform-level or digital-trace data. Methodologically, this quadrant is highly innovative, pushing forward the use of deep-learning architectures, multimodal analytics, explainable-AI techniques, and hybrid human–AI pipelines in entrepreneurship research. Conceptually, however, these contributions tend to remain thematically siloed. Their linkages to foundational debates about entrepreneurial judgment, cognition, opportunity evaluation, learning, uncertainty, or human–AI interaction remain underdeveloped. Entrepreneurs are therefore often treated as data sources, signal generators, or platform actors, rather than as reflective decision-makers whose beliefs, heuristics, emotions, and sensemaking mediate AI’s effects on entrepreneurial action.

Thus, while niche-theme research generates powerful analytic tools and deep insights into specific contexts – particularly entrepreneurial finance – its potential to inform broader cognitive and behavioral theories of AI-enabled entrepreneurship remains only partially realized. Strengthening conceptual integration between these specialized domains and mainstream theorizing represents an important opportunity for future work.

Peripheral and emerging futures (emerging/declining themes)

The lower-left quadrant contains themes that are both weakly developed and weakly connected to the rest of the field. In the thematic map, this quadrant includes small clusters associated with natural-language-processing applications, crowds and platforms, SME-level adoption, trust and fairness concerns, and algorithmic investment or scoring tools. Some of these topics reflect earlier research lines that have lost centrality, whereas others represent nascent trajectories that are only beginning to consolidate.

A first subset of emerging work examines how AI and big-data technologies are being adopted by SMEs and entrepreneurial firms across different industries. Bibliometric and review-driven syntheses of digital entrepreneurship, robotic process automation, and AI-enabled transformation show that AI-related technologies are becoming increasingly embedded in SME innovation processes and business models, although empirical research on entrepreneurial decision-making remains thin, fragmented, and largely descriptive (Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022; Patil et al., Reference Patil, Kamble, Belhadi and Sharma2023; Petrescu, Krishen, Gironda & Fergurson, Reference Petrescu, Krishen, Gironda and Fergurson2024). Complementary work on AI-mediated retail and consumer ecosystems highlights how algorithmic service environments reshape interactional contexts, stakeholder well-being, and value co-creation – developments that inevitably affect entrepreneurial firms operating on data-driven platforms (Marinova et al., Reference Marinova, de Ruyter, Huang, Meuter and Challagalla2022).

A second subset of themes looks forward to the broader societal, behavioral, and institutional implications of AI for entrepreneurship. Editorial reflections on the creator economy emphasize how AI- and platform-enabled content production is transforming entrepreneurial livelihoods, monetization logics, and power distributions in digital ecosystems (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Goldenberg, Libai, Liberman, Muller and Thorson2024). Likewise, work contrasting randomization-based decision tools with expert judgement in AI-mediated organizational environments raises foundational questions about trust, human–machine complementarity, and decision sovereignty – issues that are directly relevant for entrepreneurs operating under uncertainty and ambiguity (Felin, Koenderink, Krogh, Longo & Teece, Reference Felin, Koenderink, Krogh, Longo and Teece2023).

Finally, a growing body of research on algorithmic bias, fairness, and inclusion has begun to connect AI adoption with equity concerns in digital entrepreneurial ecosystems. Studies analyzing women’s discourse on AI bias, for example, reveal how perceptions of technological injustice shape participation, legitimacy, and motivation in AI-mediated labor and innovation contexts (Fraile-Rojas et al., Reference Fraile-Rojas, De-Pablos-Herdero and Méndez-Suárez2025). Although much of this work is not exclusively focused on entrepreneurs, it signals a critical – and underexplored – frontier regarding how trust in AI, fairness perceptions, discrimination risks, and transparency concerns influence entrepreneurial engagement and opportunity access.

Because of their peripheral position, these themes have not yet crystallized into stable, theoretically integrated research streams. However, they collectively point toward future directions in which AI–entrepreneurship scholarship may evolve – particularly around questions of inclusion, responsibility, institutional governance, and the distributional consequences of AI-driven decision systems for different types of entrepreneurs and ventures. At the same time, cognitive and behavioral mechanisms remain largely implicit: entrepreneurs are rarely analyzed as judgement-makers navigating uncertainty, trust calibration, fairness trade-offs, and moral responsibility in AI-enabled environments. This gap provides a natural conceptual bridge to the cognitively informed research agenda developed in Section 6.

Cross-quadrant synthesis: fragmentation, imbalances, and missing links in AI–entrepreneurship research

The combined bibliometric and thematic analyses reveal a research field characterized by rapid growth but marked conceptual and structural imbalances. While AI–entrepreneurship research has developed a recognizable core centered on innovation, performance, and data-driven decision-making, the cross-quadrant synthesis highlights persistent fragmentation across themes, levels of analysis, and theoretical perspectives. Similar patterns of rapid expansion accompanied by weak theoretical integration have been documented in other emerging technology-driven domains, particularly within digital innovation and data-centric research streams (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019).

Across the four thematic quadrants identified in Fig. 3, two dominant patterns emerge. First, themes with high centrality tend to emphasize technological capabilities and functional applications of AI, such as machine learning, predictive analytics, and digital transformation. This orientation reflects the strong influence of information systems, operations research, and analytics-driven traditions, which typically prioritize efficiency, optimization, and performance outcomes (Mikalef et al., 2020 a; Wamba et al., Reference Wamba, Akter, Bresciani and Rahman2021).

Second, themes that address entrepreneurial processes, judgment, or contextual embeddedness appear either weakly connected to the core or relegated to peripheral positions. This finding is striking given that entrepreneurship research has long emphasized judgment under uncertainty, opportunity evaluation, and sensemaking as defining features of entrepreneurial action (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Shepherd, Williams & Patzelt, Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015). The marginal positioning of such themes suggests that the field has evolved primarily through the extension of AI tools into entrepreneurial settings, rather than through the development of entrepreneurship-specific theoretical lenses tailored to AI-enabled contexts. Comparable concerns have been raised in adjacent literatures on digital entrepreneurship, where technological affordances often outpace advances in behavioral and cognitive theorizing (Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022; Nambisan, Siegel & Kenney, Reference Nambisan, Siegel and Kenney2019a).

Absence of entrepreneurial cognition and behavioral theory

One of the most salient findings emerging from the cross-quadrant analysis is the limited presence of cognitive and behavioral constructs central to entrepreneurship research. Despite entrepreneurship being fundamentally concerned with judgment under uncertainty, opportunity evaluation, and decision-making (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Busenitz, Bird, Marie Gaglio, McMullen, Morse and Smith2007), such constructs are largely absent from the dominant thematic clusters identified in the AI–entrepreneurship literature.

Themes located in the motor and basic quadrants focus predominantly on adoption, optimization, and performance outcomes, often implicitly assuming rational or instrumental decision-making processes. This orientation reflects the strong influence of technology-adoption and information-systems traditions, which typically emphasize efficiency, usage intentions, and outcome variables (Davis, Reference Davis1989; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis, Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis2003). In contrast, constructs related to entrepreneurial cognition – such as opportunity beliefs, confidence, sensemaking, heuristics, or algorithmic trust – remain weakly represented or entirely disconnected from the central research streams. This gap persists even in recent work that explicitly examines AI as a tool for entrepreneurial activity, where attention remains largely on capabilities, digital transformation, and performance effects rather than on the micro-foundations of judgment and belief formation (e.g., Mikalef et al., 2020 a, b; Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022). This absence is particularly striking given the growing role of AI systems as decision-support or decision-shaping technologies in entrepreneurial contexts (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Raisch & Krakowski, Reference Raisch and Krakowski2021).

The marginal positioning of cognition-related themes suggests that AI is predominantly conceptualized as an exogenous technological input, rather than as an interactive agent that reshapes how entrepreneurs perceive, interpret, and act upon information. Put differently, the field has advanced substantially in explaining what AI does for entrepreneurship, but much less in explaining what AI does to the entrepreneurial mind. From a cognitive perspective, this framing overlooks the interpretive processes through which individuals make sense of algorithmic outputs, especially under conditions of uncertainty and ambiguity (Andrade-Valbuena & Torres, Reference Andrade-Valbuena and Torres2018; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Weick, Reference Weick1995). As a result, existing research offers limited insight into why entrepreneurs differ in their responses to AI recommendations, how algorithmic outputs are cognitively processed, or under what conditions AI augments versus constrains entrepreneurial judgment (Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey2015; Logg, Minson & Moore, Reference Logg, Minson and Moore2019).

Thematic and theoretical fragmentation

Beyond the absence of cognitive perspectives, the thematic map reveals substantial fragmentation across theoretical traditions. Even within high‐density clusters, conceptual integration remains limited. For example, studies examining digital innovation and performance frequently draw on disparate frameworks from information systems, operations research, or strategic management, with little cross‐fertilization with entrepreneurship theory. Similar patterns of theoretical borrowing without integration have been observed in other technology‐driven research domains, where empirical sophistication often advances faster than conceptual coherence (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019).

This fragmentation is further reinforced by the coexistence of multiple levels of analysis – individual, firm, and ecosystem – without explicit articulation of how these levels interact. While entrepreneurship research has long emphasized the importance of linking individual-level cognition and action to firm-level outcomes and broader contextual conditions (Foss & Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015), such multi-level integration remains largely absent in the AI–entrepreneurship literature. Individual-level phenomena, such as entrepreneurial decision-making and judgment, are rarely connected to organizational capabilities or performance outcomes, while ecosystem-level analyses often abstract away from the cognitive mechanisms through which entrepreneurs engage with AI-enabled infrastructures (Nambisan, Wright & Feldman, Reference Nambisan, Wright and Feldman2019b). Recent AI–entrepreneurship studies continue this tendency, offering rich descriptions of digital capabilities, platforms, or data-driven processes, yet seldom theorizing how these dynamics are filtered through the beliefs, heuristics, and interpretive schemas of entrepreneurs themselves (Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022; Mikalef et al., 2020 a, b).

As a result, the literature is characterized by parallel research streams that advance in relative isolation, limiting cumulative theory development and the consolidation of shared explanatory frameworks. This theoretical dispersion weakens opportunities for cumulative knowledge building and makes it difficult to compare findings across studies, contexts, and methodological designs (Cobo et al., Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011). This lack of integration constrains the field’s ability to move beyond descriptive accounts of AI adoption toward deeper explanations of how and why AI reshapes entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes. The cross-quadrant synthesis thus indicates that fragmentation in AI–entrepreneurship research is not merely thematic, but also theoretical and methodological in nature (Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Schiavone, Pluzhnikova and Invernizzi2022).

Methodological imbalance and limited multi-level integration

The results also reveal a methodological concentration around quantitative, technology-centric approaches, particularly those emphasizing adoption models, performance metrics, and secondary data analyses. While such approaches have contributed to identifying broad patterns of AI use, they offer limited explanatory depth regarding the cognitive and behavioral processes that shape entrepreneurial engagement with AI technologies. This methodological orientation reflects the strong influence of information systems and analytics traditions, where predictive accuracy and outcome variables often take precedence over process-oriented explanation (Davis, Reference Davis1989; Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis2003; Mikalef et al., 2020 b).

Notably, experimental designs, configurational approaches, and mixed-method strategies remain underrepresented within the identified thematic clusters. This imbalance constrains the field’s ability to capture heterogeneity in entrepreneurial behavior, examine non-linear relationships, and identify equifinal pathways through which AI influences entrepreneurial outcomes. Prior research in entrepreneurship has emphasized the value of experiments, configurational methods, and process-oriented designs for studying judgment, decision-making, and opportunity evaluation under uncertainty (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015; Woodside, Reference Woodside2013), yet these approaches have been only marginally adopted in AI–entrepreneurship research.

Moreover, the lack of multi-level integration further exacerbates this limitation. Few studies explicitly connect individual-level cognitive processes with organizational capabilities or ecosystem-level dynamics, resulting in analytical silos that mirror the thematic fragmentation observed in the bibliometric maps. This omission is particularly problematic given longstanding calls within entrepreneurship and strategic management to link micro-level cognition and action to meso- and macro-level outcomes (Foss & Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012; Nambisan et al., Reference Nambisan, Siegel and Kenney2019a; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015). Without such integration, existing research remains limited in its capacity to explain how AI reshapes entrepreneurial behavior across levels of analysis.

Implications for research integration

Taken together, the cross-quadrant synthesis suggests that AI–entrepreneurship research has reached a stage where further progress requires conceptual integration rather than additional descriptive expansion. Similar dynamics have been observed in other rapidly growing technology-oriented fields, where early phases of empirical accumulation eventually give way to the need for theory consolidation and integrative frameworks (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Merigó-Lindahl and Olavarrieta2019). While technological capabilities and applications of AI in entrepreneurial settings are now well documented, the field still lacks a coherent framework for understanding how these technologies are interpreted, trusted, and enacted by entrepreneurs across different contexts.

The systematic absence of cognitive and behavioral perspectives, combined with persistent thematic and methodological fragmentation, limits the explanatory power of existing research and constrains its relevance for both theory and practice. Prior work in entrepreneurship and decision-making has long emphasized that technologies do not operate independently of human judgment, beliefs, and sensemaking processes (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015; Weick, Reference Weick1995). However, these insights remain weakly integrated into current AI–entrepreneurship research, which continues to privilege functional and outcome-oriented explanations.

These gaps provide a clear empirical basis for advancing a cognitively informed research agenda that reconnects AI technologies with the entrepreneurial mind, decision processes, and contextual embeddedness. Such an agenda aligns with recent calls in the human–AI interaction and strategic management literatures to move beyond adoption-centric models toward frameworks that account for interpretation, trust, and agency in algorithmically mediated environments (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Raisch & Krakowski, Reference Raisch and Krakowski2021).

The following section builds on these findings to propose a structured research agenda aimed at addressing these limitations and advancing a more integrated and cognitively grounded understanding of AI in entrepreneurship.

A research agenda for cognitively informed AI–entrepreneurship studies

Building on both the quadrant-specific analysis (Section 4) and the cross-quadrant synthesis (Section 5), this section proposes a research agenda aimed at advancing a cognitively informed understanding of AI in entrepreneurship. The quadrant-level findings reveal distinct thematic emphases – from performance-oriented motor themes to specialized niche applications and still-emerging domains – while the cross-quadrant synthesis highlights broader structural imbalances, weak theoretical integration, and a limited presence of cognitive and behavioral constructs in the core of the field.

Rather than calling for additional descriptive studies of AI adoption or performance outcomes, the agenda therefore emphasizes the need to integrate cognitive, behavioral, and contextual perspectives into the study of AI-enabled entrepreneurial processes. This shift responds to longstanding calls within entrepreneurship research to move beyond surface-level explanations and toward deeper accounts of judgment, interpretation, and action under uncertainty (McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Busenitz, Bird, Marie Gaglio, McMullen, Morse and Smith2007; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015).

The proposed agenda is structured around five interrelated research directions that respond directly to the gaps identified within and across the four thematic quadrants. These directions are informed by advances in entrepreneurial cognition, decision-making, and sensemaking research (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Weick, Reference Weick1995), as well as by emerging work on human–AI interaction and algorithmic decision systems, which emphasizes the importance of trust, interpretation, and agency in algorithmically mediated environments (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Raisch & Krakowski, Reference Raisch and Krakowski2021).

Taken together, this agenda aims to support cumulative theory development by reconnecting AI technologies with the cognitive processes through which entrepreneurs perceive opportunities, evaluate uncertainty, and enact strategic choices. In doing so, it aligns with broader recommendations for theory-building in emerging and fragmented research fields, where conceptual integration is essential for moving from descriptive proliferation toward explanatory coherence (Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015).

From technology adoption to opportunity judgment

A first priority for future research is to move beyond technology adoption frameworks toward a deeper examination of entrepreneurial judgment and opportunity evaluation in AI-enabled contexts. While adoption models such as TAM and UTAUT have been widely applied to explain whether entrepreneurs use AI tools, they provide limited insight into how AI influences the formation, validation, and revision of opportunity beliefs (Davis, Reference Davis1989; Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis2003). As a result, much of the existing literature captures usage decisions but overlooks the cognitive processes through which entrepreneurs interpret and act upon algorithmic information.

Future studies should therefore investigate how entrepreneurs cognitively process algorithmic outputs when evaluating opportunities under uncertainty. This includes examining how AI-generated information shapes opportunity confidence, perceived feasibility, expected returns, and the willingness to commit resources. These issues are central to entrepreneurship research, which conceptualizes opportunity evaluation as a judgmental process grounded in beliefs rather than objective probabilities (Andrade-Valbuena et al., Reference Andrade-Valbuena, Olavarrieta and Torres2024; Haynie et al., Reference Haynie, Shepherd, Mosakowski and Earley2009; McMullen & Shepherd, Reference McMullen and Shepherd2006). Integrating theories from entrepreneurial cognition – such as opportunity belief formation, sensemaking, and bounded rationality – would enable a more nuanced understanding of AI as a decision-shaping technology rather than a neutral informational input (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Simon, Reference Simon1947; Weick, Reference Weick1995).

Such a shift would also allow researchers to systematically explore heterogeneity in entrepreneurial responses to AI. Prior research has shown that individuals differ markedly in how they rely on, trust, or resist algorithmic advice (Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey2015; Logg et al., Reference Logg, Minson and Moore2019). Applying these insights to entrepreneurial settings would move the field beyond average adoption effects and toward explanations of why similar AI tools lead to divergent opportunity judgments and strategic choices across entrepreneurs. In doing so, future research can better account for variation in entrepreneurial cognition, experience, and context when examining AI-enabled decision-making.

Human–AI interaction and the entrepreneurial decision process

A second research direction concerns the interaction between entrepreneurs and AI systems during decision-making. Existing research frequently treats AI as an autonomous, deterministic, or purely instrumental system, overlooking the relational and interactive nature of human–AI collaboration. This tendency has been widely critiqued in the human–AI interaction literature, which emphasizes that algorithmic systems are embedded in social and cognitive processes rather than operating independently of human judgment (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Raisch & Krakowski, Reference Raisch and Krakowski2021).

Future work should therefore examine how entrepreneurs develop trust in AI systems, how algorithmic recommendations are weighted relative to intuition, experience, and prior beliefs, and how phenomena such as algorithmic aversion or overreliance emerge in entrepreneurial settings. Prior studies have shown that individuals often discount algorithmic advice after observing errors, even when algorithms outperform human judgment on average (Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Simmons and Massey2015), while others document systematic tendencies toward algorithmic reliance under conditions of uncertainty or complexity (Logg et al., Reference Logg, Minson and Moore2019). Extending these insights to entrepreneurial contexts is particularly important given the high-stakes, uncertain, and time-pressured nature of entrepreneurial decision-making.

Attention should also be given to the role of explainability, transparency, and feedback in shaping entrepreneurs’ willingness to rely on AI outputs. Research on explainable AI suggests that the interpretability of algorithmic recommendations significantly affects trust, perceived legitimacy, and learning, especially in decision-support environments (Guidotti et al., Reference Guidotti, Monreale, Ruggieri, Turini, Giannotti and Pedreschi2018; Miller, Reference Miller2019). In entrepreneurial settings, where decisions often involve subjective judgment and forward-looking evaluation, these factors may critically influence how AI is integrated into ongoing decision processes.

By focusing on human–AI interaction, researchers can better capture the dynamic and iterative nature of entrepreneurial decision-making, in which AI systems not only provide information but also shape attention, framing, and learning over time. Such an interactional perspective aligns with process-oriented views of entrepreneurship, which conceptualize decision-making as an evolving sequence of interpretations and adjustments rather than as isolated choice events (Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015; Weick, Reference Weick1995).

Methodological expansion: experiments and configurational designs

The bibliometric results indicate a strong concentration of correlational and secondary-data approaches within the AI–entrepreneurship literature. While such methods are useful for identifying associations and broad empirical patterns, they offer limited leverage for theory development when the phenomena of interest involve judgment, interpretation, and context-dependent decision-making (Shaver, Reference Shaver2007; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Williams and Patzelt2015). To advance cumulative and explanatory theory, future research would therefore benefit from greater methodological diversity.

Experimental designs, particularly vignette-based experiments, offer promising avenues for isolating causal mechanisms and examining how variations in AI characteristics, information presentation, or contextual cues influence entrepreneurial judgment. Vignette experiments are especially well suited to entrepreneurship research, as they allow scholars to simulate decision contexts under uncertainty while systematically manipulating theoretically relevant conditions (Aguinis & Bradley, Reference Aguinis and Bradley2014; McKelvie, Haynie & Gustavsson, Reference McKelvie, Haynie and Gustavsson2020). In AI-enabled settings, such designs can be used to examine how features such as algorithmic transparency, confidence scores, or recommendation framing affect opportunity evaluation and decision confidence.

Similarly, configurational approaches, such as fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), are well suited for capturing equifinality and complex causal patterns that are poorly represented in linear models (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). fsQCA allows researchers to identify multiple combinations of conditions leading to similar outcomes, thereby reflecting the heterogeneity and non-linearity inherent in entrepreneurial processes (Woodside, Reference Woodside2013). Applying configurational logic to AI–entrepreneurship research would enable scholars to examine how cognitive, technological, and contextual factors jointly shape entrepreneurial judgments and strategic choices.

Combining experimental and configurational approaches with traditional survey or archival methods would further support multi-method research designs capable of capturing both causal mechanisms and real-world complexity. Such methodological pluralism has been widely advocated in entrepreneurship research as a means of strengthening internal validity while preserving contextual richness (Shepherd & Gruber, Reference Shepherd and Gruber2021). By expanding the methodological toolkit, future studies can generate more robust insights into the cognitive and contextual contingencies of AI use in entrepreneurial decision-making.

Inclusion, ethics, and cognitive inequality in AI-enabled entrepreneurship

A fourth research direction addresses the marginal positioning of ethical, inclusive, and societal themes identified in the thematic maps. While these issues have gained increasing prominence in the broader AI literature, particularly in relation to fairness, accountability, and transparency, they remain underdeveloped within AI–entrepreneurship research. This imbalance mirrors earlier stages of other technology-driven fields, where ethical considerations tend to lag behind functional and performance-oriented concerns (Floridi et al., Reference Floridi, Cowls, Beltrametti, Chatila, Chazerand, Dignum and Vayena2018; Mittelstadt, Russell & Wachter, Reference Mittelstadt, Russell and Wachter2019).

Future studies should examine how AI systems may amplify or mitigate cognitive inequalities among entrepreneurs, such as differences in expertise, experience, technological literacy, or access to complementary resources. Prior research suggests that algorithmic systems can differentially benefit users depending on their prior knowledge and ability to interpret outputs, potentially reinforcing existing inequalities rather than reducing them (Eubanks, Reference Eubanks2018; Kalluri, Reference Kalluri2020). In entrepreneurial contexts, such dynamics may shape who benefits from AI-enabled decision support and under what conditions.