7.1 Introduction

What do investment banker Tessa Tennant, former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, European Commission official Jos Delbeke and former London mayor Ken Livingstone have in common? They are all climate governance entrepreneurs. Drawing on academic studies of these and other entrepreneurs, this chapter argues that an entrepreneurship approach can help analysts to understand why some actors, in some situations, seem able to significantly accelerate, stall or shift climate policy and governance. Moreover, the shift towards more polycentric climate governance potentially affords governance entrepreneurs an even more important role as drivers or inhibitors of new governance developments.

Governance entrepreneurship is by no means a phenomenon that pertains only to polycentric governance. Over the years, political scientists and sociologists have explored how entrepreneurship plays out in a wide variety of contexts (e.g. Huitema and Meijerink, Reference Huitema and Meijerink2009; Green, Reference Green2014; Jordan and Huitema, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014; Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). The rapidly expanding literature on environmental and climate governance focuses on entrepreneurship at many different levels and in many different sites of governing: local and regional (Brouwer, Reference Brouwer2013; Anderton and Setzer, Reference Andonova2017; Maor, Reference Maor2017), national (Huitema and Meijerink, Reference Huitema and Meijerink2009; Boasson, Reference Boasson2015; Hermansen, Reference Hermansen2015), supranational (Buhr, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) and transnational (Green, Reference Green2014; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). This chapter seeks to add to the more nuanced picture of entrepreneurship that these authors have painted, avoiding the trap of heralding entrepreneurs as heroic figures. This chapter neither defends nor questions the development of more polycentric forms of governance. Rather, it uses polycentric governance as an explanatory concept to help explain the role of entrepreneurship in climate governance.

This chapter explores three main questions. First, how should climate governance entrepreneurship be understood, defined and operationalised? Second, to what extent and how may we expect entrepreneurship to play out in polycentric governance as compared to monocentric governance? Third, what are the potential limitations of applying an entrepreneurship lens to the analysis of climate governance?

7.2 Defining Climate Governance Entrepreneurship

Political scientists have a long tradition of studying actors that aim to achieve extraordinary things. Yet there is still confusion about what entrepreneurship actually means, how to apply it as an analytical tool in empirical research and how to perform entrepreneurship studies in a way that fosters cumulative research. Let us therefore first explore how climate governance entrepreneurship can be understood, defined and operationalised.1

Back in 1961, Dahl argued that policy entrepreneurs are especially ‘skilful or efficient in employing the political resources at their disposal’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1961: 272, emphasis in original). Polsby (Reference Polsby1984: 171) emphasised a different aspect, regarding entrepreneurs as actors ‘who specialize in identifying problems and finding solutions’. However, it was Kingdon who offered a more detailed theorisation and conceptualisation. He held that entrepreneurs are characterised by their ‘willingness to invest their resources – time, energy and sometimes money – in the hope for a future return’ (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2011: 122).

His definition is very broad: it could conceivably apply to all actors aiming to influence policy development. Roberts (Reference Roberts1992: 56) argued that it was difficult to evaluate the state of entrepreneurship research because there was no consensus on what entrepreneurship was. This challenge persists, despite the substantial empirical and theoretical contributions published since the early 1990s. For entrepreneurship studies to prosper, it is important to develop a clearer understanding, starting with clear definitions. Various scholars define entrepreneurs by their skills. For instance, Fligstein (Reference Fligstein2001: 107) has argued that entrepreneurs are skilled societal actors who will be ‘more skilful in getting others to cooperate, manoeuvring around more powerful actors, and generally knowing how to build coalitions in political life’. In a similar way, Dahl argues that ‘[s]kill in politics is the ability to gain more influence than others, using the same resources’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1961: 307). Fligstein, Dahl and Polsby also indicate that creativity is a key skill, because it enables entrepreneurs to find new paths to influence. The assumption that skills are the most important defining feature is intuitively appealing. Indeed, some actors are better at assessing the political context than others. Sometimes their influence may extend far beyond what could be expected on the basis of their formal position or role. One problem here, however, is that the identification of superior abilities and personal character is difficult to operationalise. How can a person’s intrinsic skills and qualities be measured? Moreover, skills are not likely to translate into actions in all situations and at all points in time. In identifying entrepreneurship, it is thus more fruitful to focus on entrepreneurial strategies and actual actions. Ackrill and Kay (Reference Ackrill and Kay2011: 78) suggest that entrepreneurship should be regarded ‘as a general label for a set of behaviours in the policy process, rather than a permanent characteristic of a particular individual or role’. Sheingate (Reference Sheingate2003: 198) actually argues that in the study of entrepreneurship, it is a mistake to focus on the personal qualities of individuals, ‘for this … limit[s] the utility of the concept to the study of “great men”’. Instead, Fligstein and McAdam (Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012) argue that the position of entrepreneur is a role that becomes available under certain social conditions. It is up to the actors involved in the process to seize the moment and exert entrepreneurship.

In this chapter, I understand entrepreneurship as acts performed by actors who seek to ‘punch above [their] weight’ (Green, Reference Green2017). By contrast, actors who merely ‘do their job’ and do what is ‘appropriate’ cannot be considered entrepreneurs. Two different categories of entrepreneurship can be identified (see Boasson, Reference Boasson2015; Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017). Institutional-cultural acts are aimed at enhancing influence by altering the distribution of authority and information. They require scholars to pay close attention to the use of decision-making procedures and venues (Roberts and King, Reference Roberts and King1991; Schneider and Teske, Reference Schneider and Teske1992; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1999; Leca, Battilana and Boxenbaum, Reference Leca, Battilana and Boxenbaum2006; Hardy and Maguire, Reference Hardy, Maguire, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby.2008; Mintrom and Norman, Reference Mintrom and Norman2009; Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie2010; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2011; Fligstein and McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012). By contrast, structural acts aim at altering or diffusing norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews and institutional logics. It requires scholars to explore activities such as framing, image-making and persuasion (Goffmann, Reference Goffmann1974; Snow and Benford, Reference Snow, Benford, Klandermans, Kriesi and Tarrow1988; Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Goodin, Rein and Moran, Reference Goodin, Rein, Moran, Goodin, Rein and Moran2006; Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009).

Many entrepreneurship scholars have been interested in entrepreneurship as a vehicle for change (i.e. the entrepreneur as a disruptive agent). Even if many entrepreneurial acts aim at producing change, and even if the most common criterion for successful entrepreneurship is achieving change, it is important to be open to the possibility that an entrepreneur can also block change (Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017). Moreover, given the complexity of the contemporary climate governance landscape (see Chapter 1), it is not always clear which governance measures will work and which will be counterproductive. Hence, we should include all kinds of entrepreneurial motivations when we study polycentric climate governance.

Moreover, we should take into account that governance entrepreneurship is a broader term than policy entrepreneurship. Governance covers traditional forms of public policy as well as private, and public-private initiatives aimed at influencing, steering and coordinating behaviour (see Chapter 1). Hence, entrepreneurship aimed at influencing private and public, as well as public-private, decision-making should be taken into account.

7.3 The Role of Governance Entrepreneurship in Polycentric Governance

Back in 1997, many regarded the signing of the Kyoto Protocol as the first step on the path towards a monocentric global regime. Instead, climate governance subsequently adopted many more characteristics that can be described as polycentric. Changes in the basic landscape of climate governance have important implications when it comes to understanding the actual and potential roles of entrepreneurship. To shed light on this, I explore entrepreneurship under two simplified but contrasting conditions: polycentric and monocentric climate governance. Monocentric and polycentric governance differ in at least two respects (see Chapter 1):

(1) Whether steering and coordination is induced top down from global, intergovernmental agreements or bottom up from a variety of countries, sectors and domains.

(2) Whether climate mitigation relies on a few intergovernmental measures or a whole variety of measures adopted in international, transnational, national, subnational and private domains.

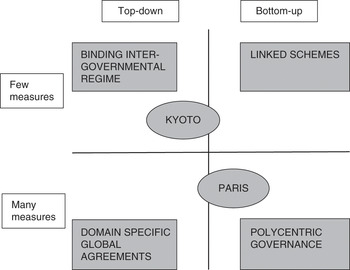

Figure 7.1 combines the two dimensions and shows that – depending on the degree of top-down steering and the number of measures in use – we are likely to find different modes of climate governance. Strong top-down steering combined with few measures and instruments would produce monocentric climate governance, while bottom-up developments combined with a great number of diverse measures and instruments would result in polycentric governance. For the sake of simplicity, I rely on the definition of polycentric governance outlined in Chapter 1.

Figure 7.1 Possible climate governance patterns.

Figure 7.1 aims to illustrate that the two dimensions (top down versus bottom up, and few versus many policies and measures) can exist in various degrees, and that polycentric governance and monocentric governing are ideal types that can guide the analysis but that will not be found as such in reality. Nevertheless, climate governance following the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol (from 1997 until around 2009) can be considered closer to the monocentric ideal than climate governance after the Paris Agreement. The Kyoto Protocol had important monocentric traits: it was based on binding commitments, targets and timetables for emissions reductions and detailed rules pertaining to collaborative efforts to reduce emissions, such as the Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation (Andresen and Boasson, Reference Andresen, Boasson, Andresen, Boasson and Hønneland2012). The Paris Agreement does away with most of these monocentric features, has weak central steering and follows a more bottom-up form of governance, in which countries make pledges to address climate change, which are subsequently subject to review (see Chapter 2).

Analytically, distinguishing between the two ideal types – polycentric and monocentric climate governance – can help us to develop more tangible expectations and predictions as to what role entrepreneurship can and will play in climate governance in the years ahead. Next, I discuss what implications these two forms of governance may have for climate governance entrepreneurship, paying particular attention to differences relating to (1) the number of measures and instruments; (2) policy windows; and (3) coordination across levels and domains.

Starting with the first of these, ever since the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated, actors that have promoted monocentric climate governance have sought to put a price on greenhouse gas emissions. I thus assume that this measure will play a superior role in this type of governance (see Andresen and Boasson, Reference Andresen, Boasson, Andresen, Boasson and Hønneland2012; Boasson and Lahn, Reference Boasson, Lahn, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2016). Under more polycentric conditions, the greater willingness and ability to experiment will probably lead to multiple parallel and partly overlapping measures (see Chapters 1, 6 and 14). This will again tend to create multiple parallel and partly overlapping policy and governance patterns at different domains and at various levels (local, national, international and transnational).

The entrepreneurship literature indicates that many overlapping decision-making venues at various levels can be a valuable asset for entrepreneurs (Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017), as it creates more entrepreneurial opportunities. One may argue that climate governance will in any event be complex – given the many sectors and actors involved in mitigating emissions – but a polycentric governance model will arguably increase this degree of complexity. I assume that polycentric climate governance will entail more, and more varied, entrepreneurship across levels of decision-making and societal domains, while a reversal towards more monocentric climate governance will reduce the volume and diversity of entrepreneurship. This assumption is rooted in existing research on how entrepreneurs respond to complexity. Newman (Reference Newman2008: 121) shows that duplication of authority structures in the European Union (EU) offers increased possibilities for societal groups to exert entrepreneurship (see also Börzel and Risse, Reference Börzel, Risse, Featherstone and Radaelli2003: 67). Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie2010: 383), studying Australian policy development, observes that a multiplicity of policy forums in the federal political system in Australia provides ‘policy entrepreneurs with more avenues through which to pursue their innovations’. According to Sheingate (Reference Sheingate2003: 187, 191), heterogeneity creates uncertainty that can be exploited by entrepreneurs.

Indeed, scholars have increasingly identified how climate governance entrepreneurs have targeted many different venues of decision-making. Cities and states play an increasingly important role in climate governance, and several authors have argued that this is partly a result of entrepreneurship. For instance, Anderton and Setzer (Reference Andonova2017) show that entrepreneurship played a key role when São Paulo and California developed stronger climate polices. Biedenkopf (Reference Biedenkopf2017) shows that entrepreneurial governors have been instrumental in the adoption of emissions trading in several US states. Maor (Reference Maor2017) and Mintrom and Luetjens (Reference Mintrom. and Luetjens2017) show how entrepreneurial activities and strategies have resulted in transnational city climate networks.

Entrepreneurship may also play an important role in national climate policy development. For instance, Boasson (Reference Boasson2015) and Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015) explore how entrepreneurship has been key at certain moments in the development of Norwegian climate policy. Significant entrepreneurial activities have also influenced EU climate policy. Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) find that entrepreneurship has been important for the EU’s policies on emissions trading, renewable energy and carbon capture and storage. Buhr (Reference Buhr2012) shows that entrepreneurship was central for the inclusion of aviation in the EU’s emissions trading system. This literature indicates that institutional as well as structural entrepreneurship plays out at all levels. However, it is biased towards acts of entrepreneurship that seek to strengthen mitigation; it is less clear regarding how much counter-entrepreneurship (i.e. acts aimed at defending carbon-intensive practices and/or hindering the adoption and implementation of climate measures) we may see as the world moves towards more polycentric forms of climate governance.

While entrepreneurship can be a cause of polycentric development, it can also be understood as a consequence of weak monocentric steering (see also Chapter 9). Green (Reference Green2014: 16) argues that weaknesses in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) created a vacuum that allowed non-state, entrepreneurial actors to launch their own governance measures. If these experiments prove successful, they may be adopted by states. It is easier to initiate new policy ideas when no policy already exists than in a landscape crowded with other activities. In particular, scholars have highlighted entrepreneurship as an explanation for the upsurge in transnational governance (Green, Reference Green2014; see also Chapter 4). Andonova (Reference Andonova2017) explores entrepreneurship in international public-private partnerships. Pattberg (Reference Pattberg2017) shows that the entrepreneurial activities will change during the lifetime of transnational governance initiatives, and specifies what activities we may expect in different phases. There is an emerging literature on the role entrepreneurship plays in international private governance; much less is known about its role in national, regional and local private and/or private-public initiatives.

We may expect that as a more polycentric governance pattern is established, entrepreneurship may contribute to strengthen it further. After all, policies tend to determine politics (Lowi, Reference Lowi1964, Reference Lowi1972). A range of historical institutional studies have taught us that once a path of development has been created, subsequent policy tends to continue along that path (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Accordingly, we may expect each of the many policies and measures adopted across scales and domains to develop along idiosyncratic paths, fostering multiple policy constituencies and decision-making venues. This will again create many opportunities for entrepreneurship, but it will become increasingly hard to know in advance which decision-making opportunities will be important. These multiple path dependencies may also contribute to hinder coherent and well-coordinated climate action (see in more detail later in this chapter).

In a monocentric regime, public decision-makers will seek to select one or a few of the best available instruments; the potentially important decision-making situations will be relatively few, and it will be relatively easy to differentiate important from unimportant decision-making opportunities. The competition for influence at these moments may, however, be very intense, so it may be harder for entrepreneurs (of all kinds) to succeed.

Second, the volume as well as the success of climate entrepreneurship is related to the existence of policy windows (e.g. Burh, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014; Hermansen Reference Hermansen2015). This is probably the single most dominant contextual condition cited in the entrepreneurship literature. Kingdon (Reference Kingdon2011: 165) regarded a policy window as ‘an opportunity for advocates of proposals to push their pet solutions, or to push attention to their special problems’. He further stated that ‘a window opens because of change in the political stream (e.g. change in the administration, a shift in the partisan or ideological distribution of seats in Congress, or a shift in national mood); or it opens because a new problem captures the attention.’ A substantial number of subsequent studies have shown that open policy windows permit enhanced entrepreneurial activities and sometimes also entrepreneurial success (e.g. Corbett, Reference Corbett2005; Ugur and Yanjaya, Reference Ugur and Yanjaya2008; Bakir, Reference Bakir2009; Zito, Reference Zito2011).

In the following, I argue that polycentric climate governance will tend to entail the emergence of many climate policy windows, but not all windows will be utilised and thus contribute to the success of entrepreneurs. In more monocentric forms of governance, there will be fewer but more important policy windows that lend themselves to entrepreneurial exploitation. Climate policy research shows that open policy windows have made climate policy and governance entrepreneurs more successful than they would have been without such a window. For instance, Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) identify an open climate policy window in the EU from about 2006 to 2009, created by the preparations for the 2009 UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) in Copenhagen. Many actors in several different climate policy areas seized this opportunity. This had implications not only for EU policy but also for national policy in the EU; however, we lack systematic research on how this window influenced national policy development (for an exception, see Hermansen Reference Hermansen2015). Moreover, Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014), as well as Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015) and Buhr (Reference Buhr2012), argue that policy windows are not merely a result of exogenous forces; entrepreneurs themselves seek to open windows and subsequently to keep them opened for as long as possible. Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015: 933) argues that ‘[a] political wave comes from somewhere and involves some form of agency; it does not just appear out of the blue.’ Several authors have shown that institutional-cultural entrepreneurship and framing is key when it comes to the very creation of windows (Buhr, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014; Hermansen, Reference Hermansen2015). Structural entrepreneurship can be important to prolong the period the window is open (Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014).

Preparations for important UNFCCC COPs (such as COP15 in 2009 and COP21 in 2015) create more important domestic policy windows in some countries than in others, but we have little systematic and comparative research on this (but see Chapter 3). We also lack systematic knowledge about the relative importance of policy windows in private or private-public governance processes. Existing research indicates that such windows primarily strengthen the positions of actors that champion more and stronger climate polices. This may, however, result from a research bias, as there are far fewer studies that analyse actors who seek to obstruct climate policy initiatives (for an exception see Kibaroglu, Baskan and Alp, Reference Kibaroglu, Baskan, Alp, Huitema and Meijerink2009).

There are good reasons to expect that the character and volume of potential policy windows will differ between polycentric and monocentric climate governance, and work on Chinese policy change processes (te Boekhorst et al., Reference te Boekhorst, Smits and Yu2010) lends support to this notion. A centralised system will probably produce rather few, but potentially more important, policy windows. The fact that national climate policy adoptions tend to peak in the year or two before and after major global climate summits, such as those held in Rio de Janeiro (1992), Kyoto (1997) and Copenhagen (2009), indicates that intergovernmental summits help to create windows of opportunity that entrepreneurs can exploit (Townshend et al., Reference Townshend, Fankhauser and Ayabar2013). However, it is important to acknowledge that a range of other factors may also have contributed to producing this pattern. The future regular ‘global stocktakes’ of the nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement may ensure that the global regime continues to open up policy windows. If the ratcheting-up logic works, then the five-year cycle of ‘pledge and review’ could create regular, global policy windows. Moreover, increasingly polycentric governance patterns will probably ensure that many more policy windows are opened across decision-making levels and domains, created by local and regional conditions, sector-specific conditions, summits held by non-state actors and so forth. Yet, it may be that these policy windows will be less dramatic and be open for shorter periods than the windows relating to major intergovernmental summits. Moreover, this development may also reduce the importance of UNFCCC COPs as events that create windows of opportunity.

In any event, it is important to acknowledge that not all actors will be able, or have the resources required, to understand that a window has opened, and thus not all windows will be exploited to the same extent. Mintrom and Norman (Reference Mintrom and Norman2009: 852) argue that entrepreneurs need to ‘display high levels of social acuity, or perceptiveness’ to exploit such windows. Such actors are not always around, and thus only some of the ensuing political potential will be tapped (Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). Moreover, polycentric governance creates a more murky political landscape that may make it harder for entrepreneurs to detect, trigger and influence policy windows. Hence, the growth in the number of potential policy windows under polycentric conditions may not necessarily translate into more successful climate policy entrepreneurship and hence more ambitious climate policies.

Third and last, coping with climate change is a true global challenge, and thus we need a certain degree of coordination in order to solve the issue effectively and efficiently. The polycentric and monocentric models of governance rely on different modes of cooperation. The polycentric approach highlights self-organisation or mutual adjustment, often resulting from mere interaction and learning (see Chapter 1). By contrast, coordination in the more monocentric approach relies on what Scott (Reference Scott2014: 59–64) terms regulative steering: hierarchically designed, formal requirements that prescribe how information is to be disseminated and compliance monitored. There are also likely to be coercive sanctions to address any shortfalls in compliance. I argue that while coordination in the monocentric approach relies on intergovernmental political agreement and the agreed system of enforcement, coordination in a polycentric governance system is more reliant on entrepreneurship.

Coordination will not be a task that gains much entrepreneurial attention in monocentric governance. Rather, this will primarily be ensured by top-down steering. The situation is likely to be radically different in polycentric governance. For coordination mechanisms to emerge in the first place, these will need to be initiated and developed by actors other than the intergovernmental regime. Some of the polycentric governance authors suggest that mutual adjustment is a key feature of polycentricity, but I do not a priori assume that this will occur (see Chapter 1). Rather, I expect climate governance entrepreneurs to primarily mobilise to influence development of rules and practices, and to a lesser extent engage to ensure adjustments of measures across levels and domains.

The pledge-and-review system introduced by the Paris Agreement combines polycentric and monocentric governance elements (see Chapter 2). It requires countries to regularly submit a nationally determined contribution, but it is largely up to the countries to set their own ambitions and choose their own reporting format. Thus, it is a relatively weak top-down steering mechanism, ‘creating a framework for making voluntary pledges that can be compared and reviewed internationally, in the hope that global ambition can be increased through a process of ‘naming and shaming’ (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016: 1107). Whether this will develop into a system that truly facilitates behavioural change depends on whether and how country representatives, business actors, international environmental organisations and so forth respond to it. Put differently: whether actors will engage in entrepreneurial ways to ensure a ‘race to the top’.

The radical increase in private carbon disclosure can be understood as an entrepreneurially induced attempt to increase climate information sharing, particularly amongst private actors (Maor, Reference Maor2017; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). Carbon disclosure implies carbon reporting which denotes reporting of carbon emissions by companies, but also a broader societal purpose, increasingly understood as an instance of informational governance (Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). Hence, mechanisms of transparency and accountability may eventually influence the behaviour of actors, leading to processes of mutual adjustment. Pattberg (Reference Pattberg2017) shows that while several carbon disclosure systems initially resulted from entrepreneurship, the activity has since become institutionalised. This indicates that coordination under polycentric governance can eventually be sustained by institutional-cultural social features, and is not completely reliant on entrepreneurship. It is, however, important to note that while disclosure may ensure that information is disseminated, actual behavioural change may not happen unless some actors use the information that is disclosed in an entrepreneurial way, for instance to nudge or pressure other actors to adjust their behaviour. Moreover, we have not (yet) witnessed such elaborate systems of carbon reporting from governmental units, such as municipalities, regions and countries (with the notable exception of the C40 reporting from cities). The pledge-and-review system under Paris may, however, trigger the emergence of more streamlined pledge-and-review procedures from a larger number of actors.

Finally, there is reason to expect that it will be challenging to ensure coordination in a polycentric system given the ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’ nature of bottom-up governance. Many initiatives can sometimes be good, but it may also hamper effectiveness and efficiency. There is indeed a danger that having too many cooks involved in polycentric climate governance can spoil the broth. That is to say, the more actors that have authority over an issue area, the harder it may be to ensure coordination (Gulick, Reference Gulick, Gulick and Urwick1937; Egeberg, Reference Egeberg, Peters and Pierre2003).

Against this backdrop, I assume that polycentric climate governance may entail emergence of entrepreneurially induced coordination, but that this will probably primarily ensure the dissemination of information and to a lesser extent ensure mutual adjustment of action. A reversal to more monocentric governance will reduce the entrepreneurial activities aimed at ensuring coordination.

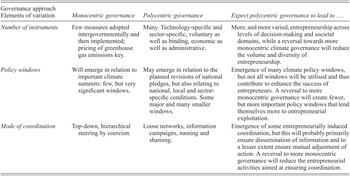

Table 7.1 summarises the differences between the nature and volume of entrepreneurial activities under the two governance modes. We should expect entrepreneurship to be a more important driver of climate action in a polycentric than in a monocentric climate governance situation, but also that entrepreneurship will take on different roles depending on which form of governance dominates. However, entrepreneurship is a rather quixotic factor – one that is highly dependent on a range of other variables. As not all entrepreneurs will be interested in more ambitious climate rules and practices, more room for entrepreneurship also means more room for actors aiming to resist climate governance.

7.4 The Role of Entrepreneurship in Climate Governance Studies

Thus far, I have argued that we should expect to see systematic differences in the role and magnitude of entrepreneurship depending on the type of climate governance mode. However, it is important to keep in mind that entrepreneurship is only one piece of the climate governance puzzle. There are clear limitations of applying an entrepreneurship lens to the assessment of climate governance.

Few studies have examined how entrepreneurship will fare when challenging powerful segments or sectors in society. It is, however, not very daring to suggest that entrepreneurship will have a smaller chance of succeeding when challenging economically and/or politically powerful actors. Social scientists that only focus on entrepreneurship may easily overlook entrenched power relationships relating to economic as well as social and cultural sources of influence. Wilson (Reference Wilson1989: 77) suggested that entrepreneurial action is key to ensuring environmental regulation, arguing that the cost of mitigating most environmental issues will be ‘heavily concentrated on some industry, profession, or locality and the benefits are spread over many if not all people’. He argued that the actors that experience costs relating to environmental action will mobilise all the political powers at their disposition to oppose these measures, while those in favour of a cleaner environment will tend to only overcome collective action dilemmas when they perform skilled entrepreneurship. Moreover, while such entrepreneurship can be very important in certain decision-making situations, it will often be challenging to create a long-lasting entrepreneurial counterweight to stronger social forces (Wilson, Reference Wilson1989: 80).

In addition to the economic interests highlighted by Wilson, several other factors may also counter the effect of entrepreneurship. Entrenched institutional-cultural features, for instance relating to energy use, modes of transportation (‘car culture’) or dietary habits (i.e. meat consumption), may thwart the adoption of stronger climate practices and governance. Moreover, public administrative units and businesses that have little to gain from climate mitigation often have superior formal authority and the ability to control information. For instance, a study of carbon capture and storage in the Norwegian petroleum industry shows that scientists, environmentalists and politicians succeeded only to a very limited degree, despite having applied a whole range of entrepreneurial strategies. The resistance from the structurally powerful petroleum segment was too strong (Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). This created a paradox: since it took more to succeed when the resistance was strong, entrepreneurs ended up being very active when they encountered strong opposition, while paying little attention to areas where the potential counterforces were much weaker. Thus, many opportunities remained unexploited.

Despite this bleak example, other parts of the climate entrepreneurship literature show that entrepreneurship can have long-lasting effects, and this gives us reason to be a bit more optimistic than Wilson (e.g. Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013; Biedenkopf, Reference Biedenkopf2017; Green, Reference Green2017; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). To understand the potential expansive effects of entrepreneurship, we need to combine the entrepreneurship approach with other social science frameworks and theories. Green (Reference Green2017) argues: ‘Considering the expansive effects of entrepreneurship means looking beyond the specific goal or target of an individual entrepreneur. Rather, it examines the extent to which entrepreneurship influenced a larger set of actors than originally intended, or helped catalyze broader effects.’

Drawing on various social science literatures, Green highlights three types of expansive effects. First, demonstration effects, where entrepreneurs, perhaps through forms of experimentation, ensure that some climate action is tested. When an action has been proven to work, this will help make the measure more legitimate. Second, policy entrepreneurship might give rise to normative changes. For instance, we have seen that entrepreneurship related to carbon disclosure has contributed to a broader corporate norm of more transparent measurement and reporting. Third, entrepreneurship might have the expansive effect of changing governance practices, leading governments to align with or adopt practices initiated by entrepreneurs. It can be challenging to determine analytically when the effects of entrepreneurship end and other causal forces take over, but skilful combinations of different theories and frameworks can help us capture important expansive and long-term effects of entrepreneurship.

To gain a better understanding of the role of entrepreneurship under polycentric climate governance, we need more cumulative and comparative research. Hopefully, the increased interest we have seen in entrepreneurship in the area of climate governance will lead more scholars to base their research on similar understandings of this concept, enabling us to contrast how entrepreneurship may play out under different conditions and the short- as well as long-term effects of entrepreneurial activities.

7.5 Conclusions

Drawing on policy, governance and institutional entrepreneurship literatures, this chapter concludes that entrepreneurship should be understood as acts performed by actors who seek to ‘punch above their weight’. By contrast, actors who merely ‘do what is appropriate’ should not be considered entrepreneurial. Two different, more operational categories of entrepreneurship were identified: institutional-cultural entrepreneurship, understood as acts aimed at enhancing governance influence by altering distribution of authority and information; and structural entrepreneurship, understood as acts aimed at altering or diffusing norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews or institutional logics.

This chapter has explored when – and to what extent – entrepreneurship plays out in conditions of polycentric and monocentric climate governance respectively. The upshot is that the role and importance of entrepreneurship will probably differ between polycentric governance and monocentric governance; entrepreneurship will probably be a more important driver of climate action in polycentric than in monocentric climate governance situations. We will also rely on entrepreneurship to ensure a broader range of tasks in the former than the latter governance mode. Moreover, entrepreneurship is a rather quixotic and unpredictable causal factor – whether entrepreneurship will be performed is not only a result of the prevailing mode of governance. It depends on the skills and experience of the persons involved, but other factors may be just as important, such as the distribution of economic and structural resources and prevalent institutional-cultural understandings. Ideally, research on climate governance entrepreneurship should combine this analytical lens with analytical frameworks that highlight other causal factors, such as path dependency, exogenous shocks, socialisation and diffusion.

There is no reason to expect that climate policy entrepreneurship will mushroom in all domains and offer a quick fix to the daunting climate governance challenge outlined in Chapter 1. Actors that aim to hamper climate governance may be just as empowered by more polycentric governance as actors that aim to induce ambitious measures. If we had been in a monocentric governance situation, we could have expected non-entrepreneurial factors, such as coercion, to produce climate governance irrespective of entrepreneurial activity. However, we are not in such a situation and it seems safe to conclude that strong monocentric climate governance will not emerge anytime soon. Hence, both researchers and practitioners should try to enhance their understanding of the promise and the limits of governance entrepreneurship.