Introduction

The year 2023 was one of political polarisation emerging in a country where traditionally there are three large power-sharing parties and industrial relations are characterised by tripartite negotiations. After Finland's North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) membership was ratified, the Finns went to the polls in an election that provided the highest support and number of Members of Parliament (MPs) to right-wing parties in modern Finnish politics (Oikeusministeriö 2023). The elections brought in a new government with an agenda to change working life, restrict migration and, crucially, to cut the national debt. This led to a very polarised start for the new government, with tight discussions about racism in the summer of 2023 and a threat of strike action looming for 2024 by the end of the year. This is in quite a contrast to the consensual process of Finland's membership application to the NATO.

Election report

The year 2023 was a general election year in Finland, and the campaign was polarised. The opposition campaigned on public distrust in the sitting Marin I government, which, nevertheless, had historically strong support, especially considering the tendency in Finnish politics to change Prime Ministers (PMs) at every election (Arter Reference Arter2023). The debate on the increase in public debt had become more salient since the end of 2023, and the coalition government was internally torn (Palonen Reference Palonen2024). This had consequences in the candidate-oriented electoral system of Finland (von Schoultz & Strandberg Reference von Schoultz and Strandberg2024), with the elections shifting political power to the right (Grönlund & Strandberg Reference Grönlund and Strandberg2023). However, government formation was difficult, as the winning margin was tight and four parties were needed to form a government. At the end of the year, campaigns for the presidential elections in January 2024 were already starting.

Parliamentary elections

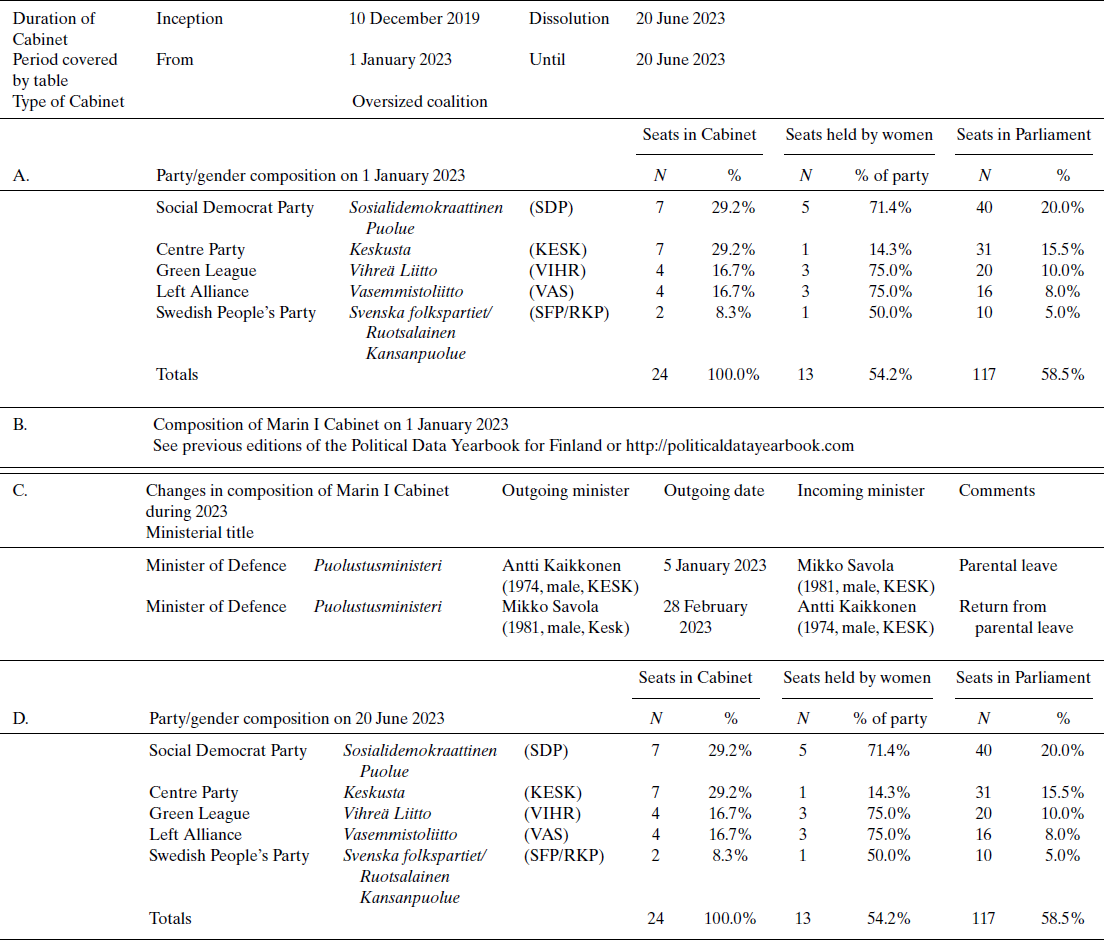

The parliamentary elections were held on 2 April 2023, with victory to the opposition parties (see election results in Table 1). The National Coalition Party/Kokoomus (KOK) and the Finns Party/Perussuomalaiset (PS) made significant gains during these elections, gaining, respectively, 10 seats and seven seats in the Parliament, with 20.8 per cent of the vote (a 3.8 percentage-point increase) for KOK and 20.1 per cent (a 2.6 percentage-point increase) for PS. Riding on Sanna Marin's leadership, the popular but divisive PM since late 2019, the Social Democratic Party/Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen puolue (SDP) also made small gains, with three more seats in the Parliament (YLE 2023).

Table 1. Elections to the Parliament (Eduskunta) in Finland in 2023

Note: Muut/other groups according to codebook criteria N = 87,444, 2,8%, change% =, seats N = 1, 0.5%. This is attributed to Harry Harkimo (LIIK) setting up his own party, added separately for 2023. För Åland sits with SFP/RKP,

Source: (https://tulospalvelu.vaalit.fi/). Ministry of Justice (2024). Parliamentary Elections 2023. https://tulospalvelu.vaalit.fi/EKV-2023/en/, last accessed 1 November 2024.

Despite the popularity of the Marin I government in the pandemic years, with between 46 per cent and 71 per cent of voters supporting it in 2020–2022 (Teivainen Reference Teivainen2024), and a record-breaking pre-election popularity of 55 per cent prior to the elections, the Marin government coalition partners made significant losses in the elections, with the Centre Party/Suomen Keskusta (KESK) losing eight seats. Considering that, only in 2015, they were the largest party, subsequently losing 18 seats in 2019 after the austerity government of Juha Sipilä (KESK) was discredited, this was a further blow to the party, leading critics to think that its participation in the left-wing government was the key problem. The Centre had been in the middle of a polarised debate where, since the autumn of 2022, they had presented an opposition within the government that was unable to fix their own lines of activity. This benefitted the PS and KOK. Indeed, while, in the past, the three largest parties were KOK, SDP and KESK, in 2023, the PS overtook the role of KESK in the contest for the three largest parties (YLE News 2023a).

The Green League/Vihreä Liitto (VIHR) lost seven seats in the election, their support falling by 4.5 percentage points. They lost more votes than any other party had lost or gained, ending up with 7 per cent of the vote. Also in the government coalition, the Left Alliance/Vasemmistoliitto (VAS) lost five seats, but only 1.1 percentage points of vote share (at 7.1 per cent). Only the Swedish People's Party/Svenska folkspartiet/Ruotsalainen kansanpuolue (SFP/RKP) managed to maintain its existing nine seats in the Parliament. The SDP ran on the popularity of Sanna Marin and the argument—particularly during the campaign and advance voting period—on the need to vote for the PM, given that the largest party would be able to lead the negotiations to form a new government. In the candidate-oriented political system of Finland, people vote for a candidate on a party list (von Schoultz & Strandberg Reference von Schoultz and Strandberg2024). In her own electoral district, Pirkanmaa, Marin received 35,628 votes, three times as many as the second most popular candidate, Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (KOK, 11,428), former Mayor of Tampere (the leading city in the region). This was a testament to Marin's personal appeal despite remaining a divisive figure in Finland (Palomaa Reference Palomaa2023).

In the opposition, there were no changes for the Christian Democrats/Suomen Kristillisdemokraatit (KD) despite significant regional support for the party leader, Sari Essayah. Movement Now/Liike Nyt (LIIK), a populist splinter from KOK, got one seat in the Parliament with the election of party leader Harry Harkimo who had previously run as an intependent for his seat in the Uusimaa region. The PS was credited for having many young candidates active in the social media, who also made it to the Parliament. Among them were Miko Bergbom and Joakim Vigelius (PS), who ended fourth and fifth in the aforementioned Pirkanmaa (with 10,525 and 10,113 votes, respectively).

The COVID-19 pandemic had been handled by the Marin government, and the recovery measures had led to an increasing public debt. Since the autumn of 2022, the opposition parties ran on the issue of public debt. Historically, this has been a sensitive issue in Finland, a country that paid its war debt to the Soviet Union and refused aid from the Marshall Plan (Pesonen & Riihinen Reference Pesonen and Riihinen2002: 19), which suffered an economic downturn in the 1990s, when trade links to their eastern neighbour were cut off with the fall of the USSR, and which had been opposing increases in European Union debt. Discourses on the need to improve national finances fell on fertile ground, and this ended up as the main election topic. Considering the paradox of popular support for the government, on the one hand, and the opposition gains on the other, the elections could be claimed to be an expression of post-pandemic fatigue. They also followed a typical Finnish pattern of electing a new coalition government in each consecutive election.

The campaign was polarised in an unprecedented way between the right-wing opposition and what the right called the ‘green-left’ (vihervasemmisto). It ended with a tight victory for the right (Kestilä-Kekkonen et al. Reference Kestilä-Kekkonen, Rapeli and Söderlund2024: 33). What followed were historically long government coalition negotiations.

Government report

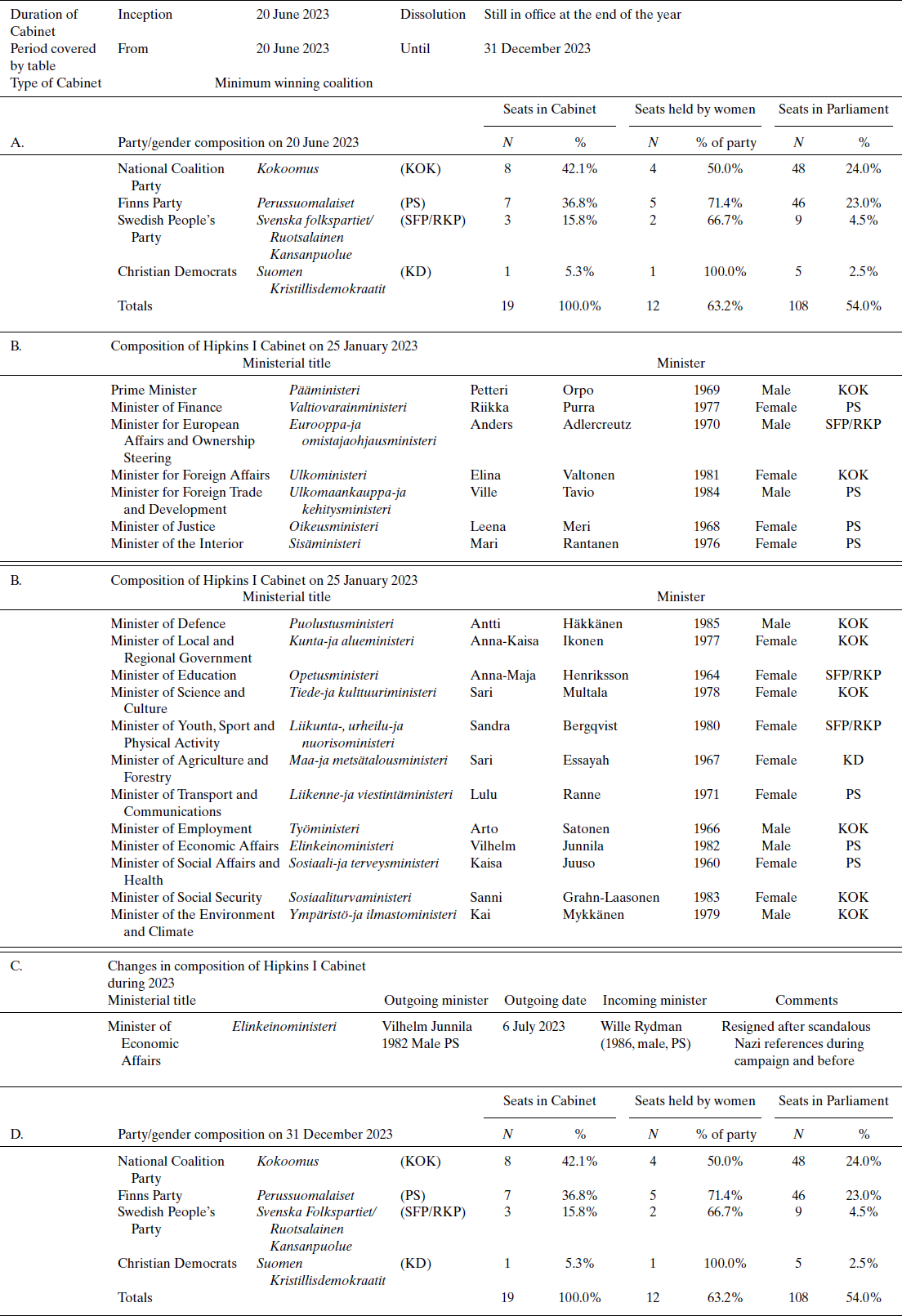

At the beginning of 2023, the forthcoming general elections burdened the Marin I government, as the coalition partners competed over potential voters. PM Sanna Marin (SDP) depicted the contestation as one to choose the prime ministerial party, while the junior coalition partners sought to become more visible and raise their profile, also in distinction to the SDP. Major reforms such as NATO membership were, however, pushed through consensually. The composition of the Marin I government is shown in Table 2.

The Orpo I government was built in what became a record for the longest government formation negotiations in Finland. The negotiations started on 3 April 2023 and ended on 20 June 2023, taking 79 days in total, and were preceded by questions on whether the involved parties would be willing to commit to budget cuts on a scale of millions of euros. The partners, KOK, PS, SFP/RKP, and KD, reached an agreement based on the ideas of reducing public debt and the need to renew the economy. This paved the way for the most right-wing government in Finland's history, headed by PM Petteri Orpo (KOK) alongside Deputy PM Riikka Purra (PS). The fragmentation of the party system allowed the parties to form a government without the centrist KESK. The government programme focused on austerity measures to put the Finnish economy on a track to growth by reversing the trend of debt-taking (Finnish Government 2023; Valtioneuvosto 2023a).

As each of the parties involved in the negotiations was needed for a parliamentary majority, the discussion focused on the role of the SFP/RKP, which was internally divided about entering the government. Much of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland, which the SFP/RKP aims to represent, was familiar with the ideas of cordon sanitaire practised in Sweden, where the populist radical right was kept out of the government. However, the SFP/RKP wanted to secure the Swedish minority access to services, reinforce the status of their language (contested by the PS) and maintain the regional hospital in Vaasa, which had been a key target of the party leader Anna-Maja Henriksson (SFP/RKP). The liberal Helsinki-region wing of the party and the more rural and regional wing had different ideas, and many were appalled by the historical situation created by the KOK. In this polarised atmosphere, the SFP/RKP did not want to join forces with the SDP, as this would have meant turning their back on the more conservative rural and regional voters, who are more united by language than ideology.

There was little ministerial expertise, as the leadership of the PS had changed dramatically in 2017, and all the sitting ministers had joined the splinter group and the short-lived party Blue Reform/Sininen tulevaisuus. When choosing Cabinet ministers, Riikka Purra, leader of the PS, held her line (Palonen Reference Palonen2021). However, several scandals concerning members of the PS broke out shortly after the formation of the Cabinet. The first scandal was the appointment of Vilhelm Junnila, the Minister of Economic Affairs, who was forced to resign after a month (20 June to 6 July 2023) due to various Nazi references both before and during the election campaign (Aaltonen Reference Aaltonen2023). He was replaced by Wille Rydman, a controversial figure himself, having previously been forced to leave the KOK following a sexual harassment scandal within the party, with investigations being pursued. Rydman, who had given up membership of the KOK parliamentary group in June 2022, joined the PS at the beginning of 2023 to run on their list in the April elections. Even though the KOK party leader, Orpo, had indicated their lack of trust in Rydman, he was trusted by the PS to run as an MP and was then proposed as a minister. This choice evidenced Purra's independence from PM Orpo (Mäntysalo Reference Mäntysalo2023). Other PS ministerial choices were also controversial, as the media uncovered that they had previously and repeatedly shared their endorsement of the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory in the context of Finland, and expressed other racist views in their writing or commentary.

Nevertheless, PM Orpo stuck with these choices, and with the stances on migration that followed from them (Paananen Reference Paananen2023). The government programme proposed restrictions to migration policy, ranging from cancelling work permits in the event of unemployment lasting longer than three months to reducing access to welfare benefits for students and migrants, halving the quota for refugees, issuing asylum for a maximum period of three years and extending the requirements for permanent residence and citizenship (Jäärni et al. Reference Jäärni, Karppi and Komulainen2023).

Under the Orpo I government, notable policy proposals made in 2023 included stricter conditions for unemployment benefits and changes that would involve a reduction in housing allowance for many in the upcoming year. These changes are thematic to the Orpo government programme, which planned reductions and changes to various social benefits as well as weakening employees’ protection against dismissal (Valtioneuvosto 2023a). The composition of the Orpo I cabinets is shown in Table 3.

Parliament report

By the end of the parliamentary year, the Parliament had passed 107 of the 109 government proposals. Five of these proposals were signed by the Marin Government, and the remaining 104 by the Orpo government.

Before the parliamentary elections of 2023, the Parliament voted on one major issue related to national politics: Finland's accession to NATO, which passed with 184 votes to seven on 1 March (Eduskunta 2023a). The Parliament of 2023 saw the passing of various government proposals related to NATO, such as an information security agreement, base and troop placement and an invention and patent agreement (Eduskunta 2023a).

At the end of the parliamentary session of 2023, government proposals 82 and 100 were still under consideration. The first one concerned discipline and crime prevention in the Finnish military, and the second concerned changing laws related to the Sámi Parliament. A polarising rhetoric was evident from the start of the year, including debates on the legitimacy of the government.

Parliamentary elections were held on 2 April 2023. After the elections, Jussi Halla-aho (PS) was elected Speaker of the Parliament, a role usually reserved for the second-largest party. There was some criticism regarding his suitability for this role, as he had been convicted of hate crimes previously, but he appealed to his freedom of speech (Jantunen Reference Jantunen2023). The existence of a right-wing government with the PS in power also generated discord in Eduskunta (the Parliament of Finland).

A first no-confidence vote against Orpo's government programme, in general, was held on 28 June. The vote united the ranks of the coalition government parties, who won comfortably with 106 to 78 votes. The opposition also called a no-confidence vote against Minister Wilhelm Junnila (PS), who was accused of being a racist or even fascist. However, on this occasion, all SFP/RKP MPs either voted against Junnila or abstained (Eduskunta 2023b). Eventually, Minister Junnila survived the motion with a vote of 95 to 86. Junnila resigned a week later, but it was significant that the SFP/RKP voted with the opposition, breaking the government line.

On 6 September, the Orpo government faced another no-confidence vote, this time concerning a government's press release about equality and non-discrimination in Finland. The vote was called by the opposition parties VAS, VIHR and SD, who took issue on Purra, Rydman and the Orpo I government, respectively. The government survived the motions with 106 for Purra and Rydman and 104 for the Orpo I government to 65 votes; the KESK MPs were absent, breaking away from the polarising confrontation between the government and the red-green opposition (Eduskunta 2023c).

The last vote of no-confidence of the year, held on 20 October, was put forward by the parliamentary groups of KESK and LIIK after an interpellation related to securing local social and healthcare services and funding for county well-being services. The opposition did not think the government had given enough assurances that these policies would be secured. The government survived the no-confidence motion with 101 to 85 votes (Eduskunta 2023d).

Many of the newly elected MPs were known mostly from social media, which also shaped the communication style within the Finnish Parliament. Also noteworthy was the fact that Sanna Marin, the PM of the previous government, was re-elected as an MP but announced her resignation as the chairperson/leader of the SDP, and later in the year, in September, also resigned as MP. This resulted in some discussion on the accountability of politicians, as she had received a record number of votes in the Tampere region, while shortly after the elections deciding to pursue an international career as a world-famous (former) politician (YLE News 2023b).

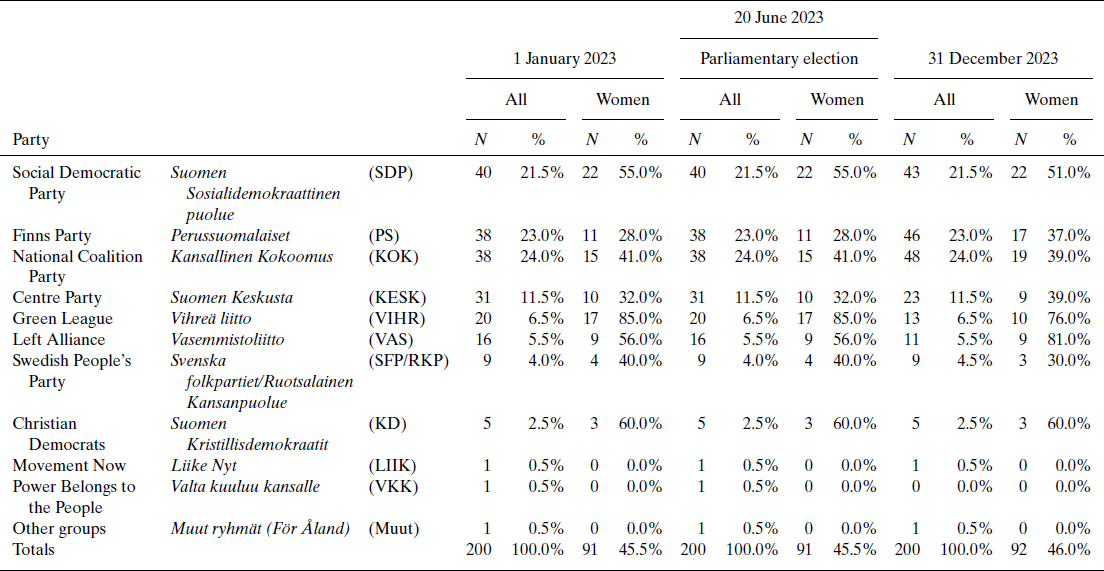

Table 4 shows the composition of the Finnish Parliament in 2023.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Eduskunta) in Finland in 2023

Source: Eduskunta (2024) (www.eduskunta.fi/FI/naineduskuntatoimii/tilastot/kansanedustajat/Sivut/hex8160_Kansanedustajien%20sukupuolijakauma.aspx). Counted in Other groups För Åland sits with SFP/RKP.

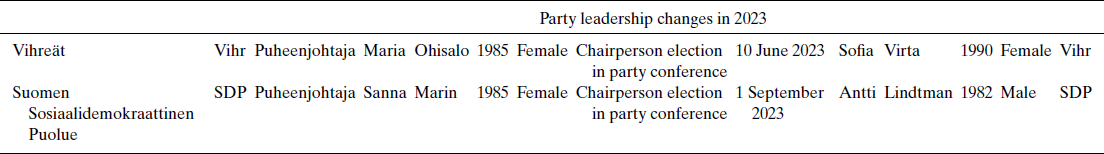

Political party report

After their electoral downturn, and also following the tradition of swift leadership terms, VIHR held a party convention on 10 June 2023 and elected Sofia Virta as the new party leader, replacing the previous party leader, Maria Ohisalo. Virta is known for her activity on social media, and has a background in social services, but was also tipped to be taking the social-liberal party slightly more to the right on economic issues, in contrast to Ohisalo, who has a background as an academic focused on poverty. With the solid right-wing austerity politics in the government, the Greens have pursued a critical line (Vihreät 2023).

The SDP had been unable to secure an extension to their prime-ministerial mandate and also saw their leader stepping down when Sanna Marin announced her resignation as the party leader/chairperson in the spring. On 1 September, the party convention elected Antti Lindtman as the new party leader/chairperson. Lindtman had originally run against Marin in December 2019 as the party sought a replacement for Antti Rinne, who stepped down as PM. This time, however, there was little contest. Lindtman, a young but less colourful persona than Sanna Marin, was expected to move the party towards the right (SDP 2023).

In their party convention on 12 August 2023, the PS changed their party secretary, with Arto Luukkanen, an academic and long-term activist, being replaced by Harri Vuorenpää (Hakahuhta & Aaltonen Reference Hakahuhta and Aaltonen2023).

KOK held a party convention to nominate Professor Alexander Stubb for presidential candidate in the January 2024 election, which would see the replacement of Sauli Niinistö, whose two terms were coming to an end (Kokoomus 2023).

KESK changed their party secretary to Antti Siika-aho, and their vice-chairs, and nominated the Governor of the Bank of Finland, Olli Rehn, as their presidential candidate, who also ran as an independent (Keskusta 2023). Annika Saarikko (KESK) remained the party leader. She argued that the two parliamentary terms in very different governments had taken a toll on the identity of the party. While she rejected the left as outdated, she also contested the way in which the Minister of Finance, Riikka Purra (PS), lacked a sense of justice by cutting the well-being of the poorest and lowering the taxes of the richest. This, from the perspective of the long history of the PS, was a major policy shift, as their predecessor, the Finnish Rural Party/Suomen maaseudun puolue, was originally a splinter group from the KESK representing the poorer rural population (Cazes Reference Cazes2024).

On the far-right fringe of the spectrum, the Ministry of Justice initiated the removal of the Blue Black Movement/Sinimusta liike from the party register due to their fascist programme, which had already been noted in the registration period (STT 2023). The party ran in the parliamentary elections of 2023, receiving 0.1 per cent of the vote, and was preparing for the European Parliamentary elections in 2024.

Changes in Finnish political parties are shown in Table 5.

Institutional change report

The biggest institutional change in 2023 was that Finland officially joined NATO as its 31st member on 4 April, after Turkey ratified Finnish membership. Finland had initially applied for NATO membership in May 2022, and its accession doubled NATO's direct border with Russia. For Finland, it meant having a new permanent delegation in the headquarters of NATO in Brussels, together with particular political, economic and military requirements issued to member states. The Brussels agreement was signed on 17 November and was approved by the government on 30 November 2023 (Ulkoministeriö 2023). Discussion about the NATO troops on the Finnish soil also evoked concern regarding the shared use of the lands in traditional activities of berry picking fishing, reindeer herding in the Finnish Lapland among the local populations, even the indigenous Sámi community (Junka-Aikio Reference Junka-Aikio2024).

Issues in national politics

Most of the issues that were salient in 2023 have already been discussed in the Election Report. Besides restricting residence and work permits for the foreign workforce and making cuts to the services available to the whole workforce, the government programme included plans to limit the right to strike. This motivated various member-organisations of the Central Organisation of Finnish Trade Unions to organise a number of single-day political strikes over the course of the autumn of 2023 (Korkala et al. Reference Korkala, de Fresner and Särkkä2024). Threats of longer strikes occurring in the following spring hung in the air (Sundman 2023). The polarised atmosphere meant that there was support for both sides of the debate.

The Finnish economy slid into recession in 2023, speeded by higher interest rates, decline of domestic demand and weak consumer confidence (Bank of Finland 2024). The inflation rate for consumer prices was 6.2 per cent, somewhat less than the year before. The continued Russian attack war had caused some instability in energy supply, but the electricity prices were going back to normal due to newly opened power plants. Some industries suffered from lack of materials or collaboration with Russian companies, and Finnish firms’ continued existence in Russia was popularly criticised.

The Ukrainian refugee population continued to be well-received in Finland in public life. In a survey among the Ukrainian population, respondents indicated relative content: ‘The majority (82 per cent) of Ukrainians who responded to the survey planned for the next six months to remain living in the same place where they were residing in Finland. Of the respondents, 12 per cent intended to return to Ukraine once the security situation in the country has stabilised, 35 per cent were unsure and 51 per cent said they wanted to settle in Finland permanently’ (Koptsyukh & Svynarenko Reference Koptsyukh and Svynarenko2024: 3). While there were Ukrainian and Russian speaking residents in Finland already before, many shrinking rural communities experienced a boost from the new arrivals, who, nevertheless, appeared not to be quite settled.