From Ostrogorski (Reference Ostrogorski1902) and Michels ([1915] Reference Michels1962) to Duverger (Reference Duverger1962), May (Reference May1973) and Katz and Mair (Reference Katz and Mair2009), the question of how grassroots members and party elites relate to one another has long been a concern of political science. In particular, whether it is Ostrogorski (Reference Ostrogorski1902, p. 596) lamenting Liberal Party activists in Britain being more extreme than the rest of the party, May (Reference May1973) putting forward his law of curvilinear disparity between leaders, members and voters or Katz and Mair (Reference Katz and Mair2009, p. 759) referring to members as ‘the ones most likely to make policy demands inconsistent with the “restraint of trade” in policy that is implied by the cartel model’, scholars have traditionally viewed the grassroots as an ideologically purist stratum of the party, sandwiched between more pragmatic leaders and centrist voters. This has been especially the case for young members, with party youth wings considered hotbeds of radicals that attempt to push their senior parties further to the Left or Right (Braunthal, Reference Braunthal1984; Svåsand, Reference Svåsand, Katz and Mair1994). However, despite the amount of attention devoted to the leaders‐members relationship, we still know little about the factors that fuel self‐perceived congruence and incongruence among party members in general, and young members in particular. Given that youth wings are a key entry point into party politics and many of those who join them will go on to be the activists, officials, candidates, representatives and leaders of tomorrow (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Nielsen, Pedersen and Tromborg2020; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Ohmura et al., Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018), studying how they view their ideological fit with the senior party can provide a unique window on intra‐party ideological and organizational dynamics. Using data from the YOUMEM project (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024), which surveyed members of 12 centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings in Australia, Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain and Sweden, we therefore ask in this article: What drives self‐perceived ideological congruence and incongruence among members of party youth wings?

We address our question through three main innovations. First, to understand better how people see themselves as fitting ideologically with their parties, we propose a typology of congruence which divides members into three groups: radicals (who place themselves further from the centre than they place the party), moderates (who place themselves closer to the centre than the party) and aligned (who place themselves the same as the party). Second, to understand why they view themselves in these ways, we propose a number of hypotheses for what might drive congruence and the different types of incongruence. We argue that congruence and incongruence are likely to be influenced by two factors related to people's political socialization, that is, the length of membership and ambitions to stand as a candidate, and by two factors related to the senior party context, namely whether the party is on the left or right, and whether it has won national office after the last general election. Third, we apply our typology and set of hypotheses to the YOUMEM project (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024), which is the first cross‐country comparative survey of party youth wing members.Footnote 1

Our results show that radicals account for over half of youth wing members. However, they are not evenly distributed between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings. In fact, in each country we examine, it is the centre‐left youth wings which contain the highest proportions of radicals, while centre‐right youth wings generally appear more balanced in their mix of radicals, aligned and moderates. We also uncover a couple of other distinguishing characteristics of radicals: first, they tend to have been in the youth wing for longer than members who are aligned, and second, they are under‐represented among those who joined with the intention of standing for election in the future.

Our study makes several theoretical and empirical contributions. Theoretically, we advance scholarship on ideological incongruence by going beyond the idea of party members as a monolithic block, and of non‐aligned members as a single ‘misfit’ category. Instead, we propose a typology incorporating directions of incongruence, in addition to a series of theoretical propositions for why members are congruent or not. This can help researchers to comprehend better the diversity of ideological positions and opinion structures within parties, along with the push and pulls that may be exerted on party elites. Empirically, ours is the first study to provide robust evidence that a sizeable component of those in youth wings are indeed radicals, at least in the sense that they consider themselves further from the centre than they view their parties. At the same time, it also shows that young people in parties are more varied in terms of ideological congruence than their traditional image suggests.

In the next section, we set out the theoretical background to our study, present our typology and develop a series of hypotheses regarding the factors that lead members to perceive themselves as ideologically aligned, radical or moderate. We then introduce our cases and discuss the original survey data used to test those hypotheses. In the results section, we present the findings of our empirical analysis. Finally, in the conclusion, we discuss the implications of our study and suggest paths for future research.

Ideological congruence and youth wings

For over a century, scholars have discussed whether grassroots memberships are more radical than party elites and what the implications of this might be for policies, intra‐party democracy and democracy itself (Butler, Reference Butler1960; Ostrogorski, Reference Ostrogorski1902; Putnam, Reference Putnam1976). In the past decades, this question has given rise to a body of work on May's law of curvilinear disparity (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989; May, Reference May1973; Norris, Reference Norris1995) and, more recently, on ideological incongruence (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012). While the two concepts are not entirely the same, they are similarly intent on understanding the ideological fit of grassroots members with their parties. Scholarship on May's law focuses on the objective ideological distance between grassroots members, party elites and voters, looking in particular at whether these three groups are more or less radical/moderate than one another (i.e., the direction of that ideological distance). The literature on ideological incongruence instead examines whether grassroots members perceive themselves as being aligned with their parties or not (without focusing on the direction of any eventual incongruence). With the exception of May's original (non‐empirical) contribution, however, none of the work on either disparity or incongruence has attempted to understand the factors that drive members in different directions.Footnote 2

In our study, we combine the van Haute and Carty approach (perceived congruence, without direction) and the May one (objective congruence, with direction) by examining the direction of perceived incongruence. To do so, we propose a new conceptualization of ideological incongruence which divides incongruent members into ‘radicals’ and ‘moderates’. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 1, we consider ‘radicals’ to be those who locate themselves closer to the extremes of the left‐right scale than where they place the senior party, and ‘moderates’ to be members who locate themselves closer to the centre than the senior party (with the ‘aligned’ being those who view themselves as congruent).Footnote 3 The distinction between incongruent members who are radical and those who are moderate has important practical implications. First, the direction of incongruence can have important effects on the party. The entry of more radical members into UK Labour that led to the election of Jeremy Corbyn as party leader in 2015 is often cited as an example of this. Indeed, it is also the case that many long‐standing ‘New Labour’‐type members likely considered themselves more moderate than their party after Corbyn took over (Bale et al, Reference Bale, Webb and Poletti2019, p. 54). More dramatically, the influx of radicals – and the marginalization of moderates – among the grassroots of the Republican Party across the United States in recent years has led to the selection of extreme candidates at all levels and fuelled polarization within that political system (Homans, Reference Homans2022). Second, perceived incongruence can have important effects on members’ behaviour. As van Haute and Carty (Reference Van Haute and Carty2012, p. 886) argue, identifying those that believe themselves to be ideologically incongruent in a party may provide ‘insight into the profile of those most susceptible to exit’. In line with this, empirical studies have demonstrated that perceived incongruence is a significant driver both of being inactive (van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Poletti and Bale2017) and of the decision to leave (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; Wagner, Reference Wagner2016). Relatedly, at least as far as MPs are concerned, research has shown that perceptions of incongruence matter more than objective distance in explaining dissent (Close & Núñez, Reference Close and Núñez2017). In short, the perception and the directions of incongruence matter to parties and to democracy.

Figure 1. A typology of ideological congruence.

While our tripartite conceptualization can shed light on the ways in which party grassroots are incongruent, there remains the question of what drives congruence and incongruence. So far, May's is still the only study that proposes an account of the mechanisms behind these positions by taking into consideration the direction of incongruence. In particular, he argues that members will be more radical than party elites because of two factors related to their political socialization (May, Reference May1973, pp. 148–151). First, according to May, elites are said to be more motivated by electoral concerns and are thus closer to the centre (where the median voter is said to reside), than their more ideologically pure grassroots members. Second, party elites will have more opportunities to interact with officials from other parties, which leads them to moderate their views. By contrast, grassroots members will inhabit ‘closed’ circles of like‐minded people, which fosters their radicalism. For May, party organizations thus consist of two relatively homogeneous groups: moderate elites and radical members.

We take a different approach to explaining members’ incongruence, which stems from Kitschelt's critique of May that ‘leaders and followers [members] are not internally homogenous groups but comprise individuals with highly diverse motivations and aspirations, rendering it questionable whether any single dominant motivation can be attributed to each group’ (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989, p. 403). In other words, to understand incongruence requires looking at individual members’ political socialization and the aspirations that derive from this. Moreover, following Kennedy et al (Reference Kennedy, Lyons and Fitzgerald2006), we need to consider the party contexts in which those members find themselves, since inter‐party electoral competition dynamics can shape members’ perceptions of where they and the party stand ideologically. With these two considerations in mind, we propose a set of hypotheses which do not treat memberships as monolithic blocks but instead take account of the roles played by individual and party‐level factors in driving feelings of congruence and incongruence. Specifically, reflecting May's arguments on political socialization, at the individual level we focus on the length of time that members have been in the organization and on their ambitions to one day stand for election. As for the party context, we examine how party ideology and government/opposition status influence members’ perception of themselves as being aligned with, more moderate, or more radical than their parties.

We study ideological incongruence in youth wings, which are a party sub‐organization for young people and have long been considered hotbeds of radicalism (Braunthal, Reference Braunthal1984; Svåsand, Reference Svåsand, Katz and Mair1994).Footnote 4 Youth wings are a key recruiting channel for parties and an important part of the pipeline for elected representatives in Western parliamentary democracies (Binderkrantz et al, Reference Binderkrantz, Nielsen, Pedersen and Tromborg2020; Hooghe et al, Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Ohmura et al, Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018). As Trimithiotis (Reference Trimithiotis, Charalambous and Christophorou2015, p. 167) puts it, youth wings ‘spearhead efforts to renew the membership base of their parties, by bringing young people into their fold, socialising and educating them in both ideological and practical terms, before promoting them to the party ranks’. Despite their importance, youth wings have been largely overlooked by researchers, with only a small number of single‐country (e.g., de Roon, Reference Roon2020; Ohmura & Bailer, Reference Ohmura and Bailer2022; Rainsford, Reference Rainsford2018) and comparative studies (Ammassari et al, Reference Ammassari, McDonnell and Valbruzzi2023; McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024) having been published on them. In terms of our objectives, what we do know is that young members have traditionally been considered the radical vanguards of their parties (Russell, Reference Russell2005, p. 566; Weber, Reference Weber2017, p. 387). For example, in late 1960s and 1970s West Germany, the Jusos (youth wing of the Social Democrats) were described as attempting ‘to “march through the institutions” of the party and the State as a means of moving them in a socialist direction’ (Braunthal, Reference Braunthal1984, p. 47). Similarly, young Conservative organizations in the UK in the 1970s were considered more right‐wing than their party (Pickard, Reference Pickard2019, p. 202). Overall, therefore, the youth wing‐party relationship can be characterized as Svåsand (Reference Svåsand, Katz and Mair1994, p. 311) observed about the case of Norway: ‘Although most of the top leadership in the parties emerged from the various youth branches, the relationship between the two organizations is often conflictual, with the youth organization being frequently more radical than the main party’.

In this article, we not only assess the ideological congruence of youth wing members to see whether they do indeed consider themselves more radical than the senior party but investigate what might influence the likelihood of them being radical, moderate or aligned. In line with our discussion above about the relevance for congruence and incongruence of members’ socialization (May, Reference May1973), their individual aspirations (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989) and the party context in which they are embedded (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Lyons and Fitzgerald2006), we propose a set of hypotheses that investigate the effects of these factors on both congruence and incongruence. We begin by examining whether members’ feelings of ideological proximity to the senior parties vary according to two individual‐level factors related to their socialization in the youth wing. Specifically, we focus on the length of time members have been in the youth wing and their political ambitions.

As regards the former, the literature presents mixed indications concerning what we might expect to find. On the one hand, it is plausible that the more familiar you become with politics, the less you will rely on the ideological cognitive shortcuts offered by your party (Baldassarri, Reference Baldassarri2013; Lupia, Reference Lupia1994). In addition, grassroots members who have spent longer in an ideologically purist ‘closed circle’ of rank‐and‐file (Duverger, Reference Duverger1962, p. 101) – or as May (Reference May1973, p. 150) puts it, a ‘smallish, clannish group’ of radicals – might see themselves as less moderate than their party elites. While some of these radicals may remain in the party due to a desire to shift it towards their views (or because they have more salient social or material reasons to stay), others of course may choose to leave. In fact, some studies have shown that incongruent senior party members are those most likely to quit (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; Wagner, Reference Wagner2016). On the other hand, it could also be the case that the more time people remain in the party, the more they internalize its values and identify fully with its positions. For example, de Vet et al (Reference Vet, Poletti and Wauters2019) find that longer‐standing Flemish and British party members are less inclined to cast a defecting vote than those who have joined more recently. Similarly, Rehmert (Reference Rehmert2022, p. 1,087) observes that the longer German MPs have been in their parties, the more likely they are to support it during free votes in parliament. Given the above considerations, we therefore propose the following competing hypotheses:

H1a The longer members have been in the youth wing, the more likely they are to be radical than moderate or aligned.

H1b The longer members have been in the youth wing, the more likely they are to be aligned than radical or moderate.

Our second individual‐level expectation concerns political career aspirations. In terms of our typology, we would envisage the aligned to be over‐represented among youth wing members who say that running for office in the future was a reason for joining. First, we would expect them to be disproportionately aligned rather than radical and moderate since, if they aspire to stand for election and defend the senior party's platform, they should be more inclined to say that their ideological stance matches that of the party. Second, if we look at the ideological self‐placement of actual candidates (which is what ambitious youth wing members aspire to be one day), we find that they do tend to be less radical than ordinary grassroots members of their respective parties (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989; Polk & Kölln, Reference Polk, Kölln, Demker, Heidar and Kosiara‐Pedersen2020). Similarly, party elites have been shown to favour candidates who are less radical and are therefore believed to be more attractive to voters (La Raja & Schaffner, Reference La Raja and Schaffner2015). This gives rise to the following hypothesis:

H2 Youth wing members with candidate aspirations are more likely to be aligned than radical or moderate.

In addition to the political socialization of individual youth wing members, we look at the party contexts in which they are embedded. Specifically, we consider two senior party‐level factors that might drive incongruence: the party's ideology and whether it has been successful in securing national office at the most recent general election. As regards the former, left‐wing parties have long offered their members greater internal democracy and opportunities for discussion – and disagreement – than right‐wing ones (Bolin et al, Reference Bolin, Aylott, dem Berge, Poguntke, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017; Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015, p. 182–183). Therefore, it is likely that grassroots members on the left will feel more comfortable in voicing positions which are not aligned with those of the senior party. Furthermore, in most contemporary Western democracies there are electorally stronger parties on the radical right than on the radical left, with many of the former having acquired government experience and developed strong party organizations (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015). This means there is usually a more attractive exit option for dissatisfied radicals in centre‐right parties than for those on the centre‐left. Supporting our argument, Kölln and Polk (Reference Kölln and Polk2017) find that the most incongruent members in Sweden are in the centre‐left Social Democrats, while the least are in the centre‐right Christian Democrats. Moreover, in their study of curvilinear disparity among Dutch party members, MPs, and voters, Van Holsteyn et al (Reference Van Holsteyn, Ridder and Koole2017) observe that members of parties on the left are more likely to perceive themselves as being closer to the extremes than their respective parties’ MPs. Given the above, we expect to find the following pattern across youth wings:

H3 Youth wing members of the centre‐left are more likely to be radical than those of the centre‐right.

The second party‐level factor we examine is whether the parties of youth wing members ended up in government or opposition immediately after the most recent general election. This is particularly relevant for centre‐left and centre‐right parties, which have been the main parties of government in Western democracies. We envisage that, when mainstream parties have secured national office, their members are more likely to be satisfied with the senior party's trajectory, and feel that its ideological position is a winning one. This is consistent with Whiteley and Seyd (Reference Whiteley and Seyd1998), who find in the case of the UK Conservatives and Labour that electoral success increases support for party policies among grassroots activists. By the same token, we expect that when mainstream parties fail to enter government, their members are more inclined to express their dissatisfaction by displaying incongruence (i.e., placing themselves as more radical or more moderate than the senior party). Our last hypothesis investigates this mechanism:

H4 Members of youth wings whose senior party came into power following the last general election are more likely to be aligned than radical or moderate.

Cases, method and data: Youth wing members in six countries

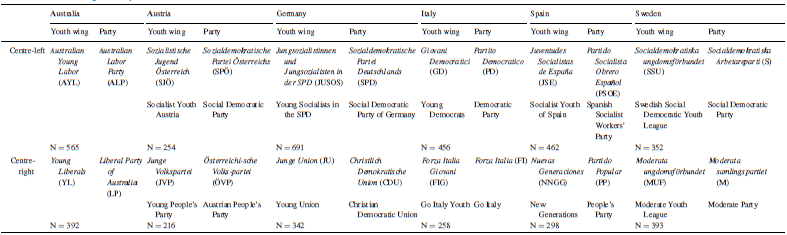

This study is based on data from the YOUMEM project (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024), which surveyed members of the 12 main centre‐right and centre‐left party youth wings in Australia, Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain and Sweden (see Table 1 below).Footnote 5 To investigate ideological congruence, we draw upon responses from 4,679 members. The selection of countries represent ‘typical’ (Gerring, Reference Gerring2006) cases of Western parliamentary democracies which have traditions of strong centre‐left and centre‐right parties alternating as the major parties in government and opposition.Footnote 6 In addition to providing an environment in which future grassroots members are politically socialized, youth wings are often the training grounds for future political careers in these countries.Footnote 7 Given our case selection strategy, we would expect our findings to hold widely for mainstream youth wings in Western democracies (Ibid, p. 89).

Table 1. Youth wings surveyed.

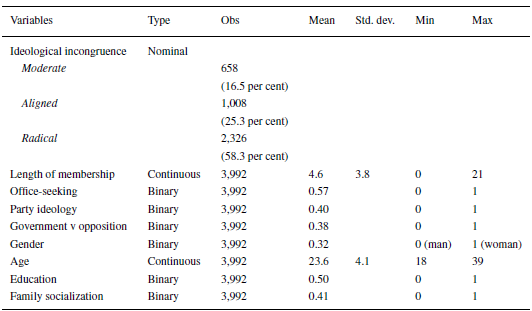

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Note: We employ list‐wise deletion, that is, we use only individuals about whom we have information for all variables of interest and exclude individuals who did not answer these questions (e.g., no answer, don't know, etc.).Footnote 13

The YOUMEM project surveyed the 12 youth wings between 2018 and 2022. The questionnaire was available in English, German, Italian and Spanish on the online platform LimeSurvey, and in Swedish on the Qualtrics system. The Australian survey was launched in March 2018 and concluded in November that year, the Spanish and Italian ones took place between March 2020 and April 2021, the Swedish survey was fielded in September‐October 2020, while the Austrian and German ones were conducted in the second half of 2021 and first half of 2022.Footnote 8 The long timeframe for most of the surveys was due to the difficulties of securing distribution among the youth wing memberships in all countries except Sweden. In Australia, Italy and Spain, going through the national level was either not feasible or produced few results, so we asked youth wing leaders in all states (Australia), regions (Italy) and autonomous communities (Spain) to distribute the link to their local members. In Austria and Germany, we had better cooperation from national youth wing leaders, but it still took a long time to achieve good distribution among the state level branches. For the Swedish survey, contact was first established with each youth wing's national leadership. These distributed a link to the survey via e‐mail to all members who had provided them with an e‐mail address.

While the YOUMEM project's survey is the largest conducted to date on youth wings, it is worth acknowledging a few inevitable limitations. First, since some of the youth wings were unwilling to share precise information about how many members they have (or how many received the survey link), we do not know the proportions of members from all 12 youth wings that responded to our survey.Footnote 9 That said, according to what we know about party members (both young and old) more generally, our sample is representative of these populations since our respondents tend to be male, well‐educated, politically ambitious, and with a higher‐than‐normal level of family background in parties (see Table 2) (Bruter & Harrison, Reference Bruter and Harrison2009; van Haute & Gauja Reference Van Haute and Gauja2015). Second, although we were eventually able to secure good geographical coverage, with at least three quarters of all regions, states and counties in each country being represented, ours is a non‐random sample, and so we should be careful when generalizing our findings.Footnote 10 Third, it could be objected that not all youth wing members are obliged to also be enrolled in the senior party and, as such, it might be problematic to ask about their congruence with the senior party (compared to youth wing members who are in the latter). Indeed, as explained in Appendix A, in 6 of our 12 cases (JVP and SJÖ in Austria, JU and Jusos in Germany, JSE in Spain, SSU in Sweden), it is possible to be an adult member of the youth wing without formally being a member of the senior party. In practice, however, the vast majority of our respondents from those youth wings are also senior party members and only in one case (JSE) does that proportion fall below two‐thirds. Moreover, even when youth wing members are also officially members of the senior party, they are still members of an organization that is bound to accept the senior party's ideology and rules.

The survey first asked demographic information, followed by questions about political interest, issues that mattered to the respondents, their family and friends’ political involvement and reasons for joining. Most importantly for this article, respondents were asked to use integers to place both themselves and their senior parties on a 1–10 left‐right scale.Footnote 11 To understand different types of ideological incongruence among youth wing party members, we created a categorical dependent variable from the two survey questions about respondents’ ideological self‐placement and perceptions of the senior party's left‐right position. Since we placed these two questions next to each other in the survey, respondents were able to make a direct comparison between the two placements. Thus, we interpret those respondents who place themselves and the senior party on the same left‐right value as clearly aligned. Respondents who choose to place themselves at a different point on the left‐right dimension have identified themselves as being incongruent. We define those respondents who place themselves closer to the theoretical mid‐point of the scale than the senior party as ‘moderates’, and those who place themselves closer to the extreme of the scale than the senior party as ‘radicals’. Mathematically, we centre both left‐right scales by collapsing them at their midpoints, meaning that higher values denote greater distance to the centre, no matter whether it was closer to the left‐ or right‐end of the scale. We then subtract the senior party position from the self‐placement.Footnote 12 The resulting value is zero for the aligned, when both positions are the same. The result is smaller than zero for the moderates, as the senior party has a greater value, and thus a more extreme perceived position, than the respondent. Conversely, results greater than zero indicate that the respondent placed themselves further to the extreme than the senior party, making them a ‘radical’.

Our independent variables are based on two individual‐level and two party‐level factors that, we argue, should influence ideological congruence. As regards the former, we calculate the respondents’ membership length based on the year they joined. To gauge their political ambitions, we look at the extent to which, when asked about the reasons they joined, they agreed with the following statement: ‘I wanted to stand as a candidate one day’. We measured the agreement on a four‐point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, as well as ‘don't know’), which we recode into a binary agree (1) and disagree (0). In terms of the two party‐level factors, the first variable measures party ideology by distinguishing between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings, while the second indicates whether, following the most recent general election (prior to the survey), the party had entered government or opposition.

For the control variables, we focus on four socio‐demographic characteristics drawn from the literature. First, we use the self‐identification of respondents as women and men for gender, since previous studies have found that men are more likely to be ideologically incongruent (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; Lisi & Cancela, Reference Lisi and Cancela2017; van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012). Second, we calculate respondents’ age by their birth year, with the expectation that the older youth wing members are, the more likely they are to perceive themselves as ideologically incongruent with the senior party (van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012). Third, we recode the educational levels of youth wing members into a binary variable which distinguishes between tertiary education and below‐tertiary education, given the low numbers of people in our sample with only a primary education (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024). The evidence on the relationship between education and ideological incongruence is mixed, with some studies showing that higher‐educated members tend to be more aligned (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017), but others finding the opposite (Lisi & Cancela, Reference Lisi and Cancela2017). Fourth, we measure family socialization with a question about whether anyone in the respondent's immediate family has ever been a party member. If family socialization serves as a proxy for political sophistication, we would expect youth wing members with politically engaged parents to display greater incongruence (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017).

Youth wing members’ ideological congruence

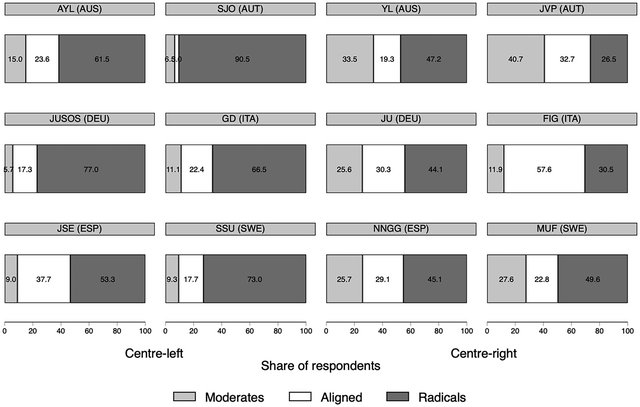

In this section, we present the results of our empirical analysis, beginning with the distribution of youth wing members according to our tripartite typology. Over half (58.3 per cent) of the young people we surveyed place themselves closer to the extremes than they place the senior party, and therefore are radicals. Conversely, moderates are a small minority among youth wing members, representing 16.5 per cent of our sample, while the aligned account for 25.3 per cent. Within this general picture of youth wings predominantly composed of radicals, however, we can see clear differences in the size of our three ideological types across the 12 cases. For example, as Figure 2 shows, the Austrian centre‐left SJÖ has the highest proportion of radicals (90.5 per cent), the Italian centre‐right FIG has the largest percentage of aligned members (57.6 per cent) and the Austrian centre‐right JVP has the biggest share of moderates (40.7 per cent).Footnote 14

Figure 2. Moderates, aligned and radicals, by youth wing.

Note: Based on the numbers of moderates, aligned and radicals, reported for each youth wing in Table C2 in Appendix C. The six centre‐left youth wings are in the left half, while the six centre‐right ones are in the right half. In each half, the order is according to country and is the same on both sides, e.g., Australian Young Labor (AYL) is in the top left corner of the centre‐left youth wings, while the Australian Young Liberals (YL) are in the equivalent position on the right half of the figure. Country abbreviations in each label are as follows: AUS (Australia); AUT (Austria); DEU (Germany); ITA (Italy); ESP (Spain); SWE (Sweden).

Figure 2 reveals clear patterns distinguishing the two party families from one another. In all countries, centre‐left youth wings have a higher proportion of radicals than their centre‐right counterparts, providing preliminary support for our third hypothesis. In fact, while the six centre‐left youth wings each contain a clear majority of radicals, none of the centre‐right ones do so. The largest percentages of radicals are in the Austrian and German centre‐left youth wings, the SJÖ and Jusos. This may reflect the fact that these organizations explicitly place themselves further to the left than their senior parties even in their choice of names, with both including the term ‘socialist’ while the senior parties are simply labelled ‘social democratic’ (see Table 1). By contrast, the centre‐right youth wings appear more balanced ideologically as, in four of the six cases, moderates, radicals, and aligned all represent at least 20 per cent of members.

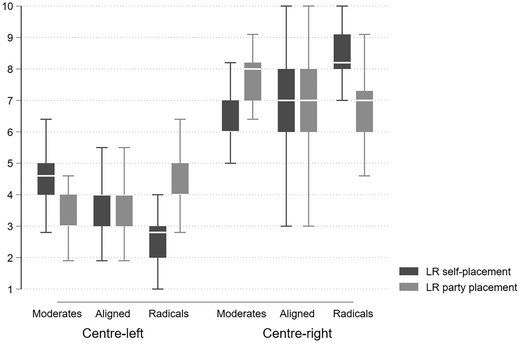

To provide more analytical insights into our tripartite categorization, Figure 3 shows the distributions of self‐placement and party placement by ideological type and party family. From this, we can see several differences between party families. For example, moderates on the centre‐left are nearer to the mid‐point of our scale than moderates on the centre‐right. In addition, moderates and aligned on the centre‐left agree in their perception of the senior party placement, while radicals perceive it as being closer to the centre. In centre‐right parties, it is the other way around: radicals and aligned agree on the senior party placement, while moderates see it as closer to the extreme. Thus, both self‐placement and party placement play a role in determining incongruence. Interestingly, despite party family differences, it is the moderates in both centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings who seem furthest away from their senior parties. This may point to greater perceived polarization between left and right, with those who feel close to the centre feeling less at home in mainstream parties.

Figure 3. Distribution of self‐placement and party placement by ideological type and party family.

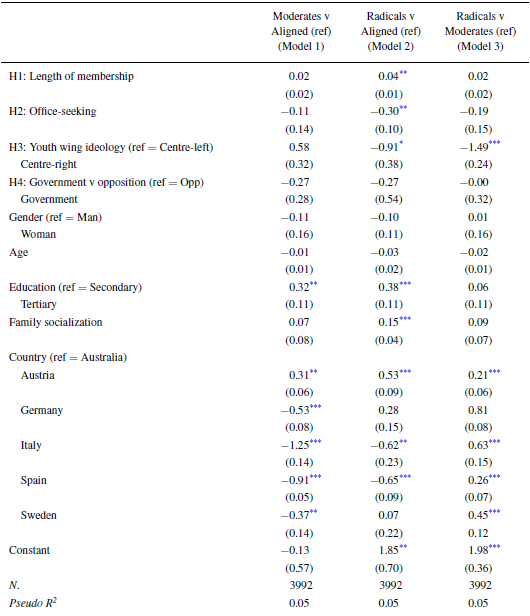

Table 3 reports the results of our statistical analysis. Since we measure ideological congruence with a three‐level categorical variable, we performed a multinomial logistic regression to test our hypotheses. This included our individual‐level and party‐level independent variables discussed earlier (length of membership, office ambitions, party ideology, and government vs opposition status) and our controls (gender, age, education, family socialization). Models 1 and 2 in Table 3 report the regression coefficients for moderates and radicals, respectively, using the aligned members as the reference category. In the third model, we compare moderates and radicals, with moderates as the reference category. Each coefficient therefore needs to be interpreted as the effect of the independent variable on the likelihood that a respondent falls into the target instead of the reference category.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression predicting ideological congruence and incongruence.

Note: Standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

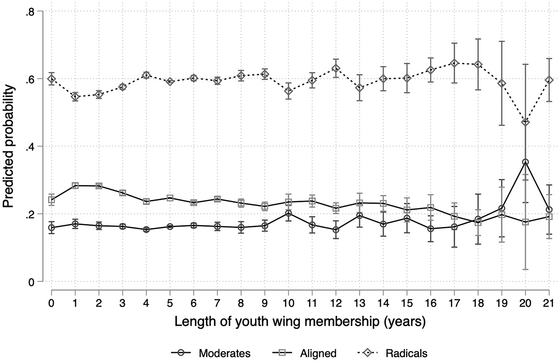

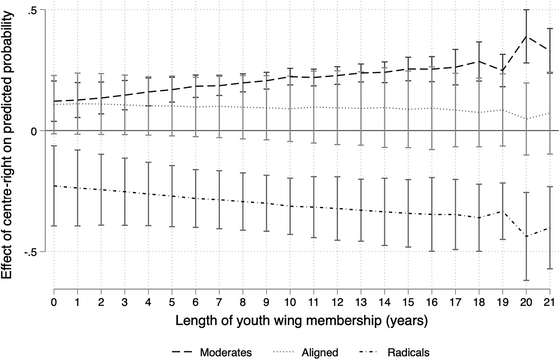

Hypotheses 1a and 1b investigate the effect of time spent in the youth wing on incongruence. The results in Table 3 show partial evidence for H1a. Model 2 indicates that the relative probability of being radical rather than aligned increases with time. The effect size is fairly small, with the chance of being radical rather than aligned for each membership year increasing by 0.04. As membership length ranges from 0 to 21 years, the maximum effect is an increase of 0.84, which nevertheless is comparable to the effect of being in a centre‐left youth wing instead of in a centre‐right one. These results speak to the contradiction highlighted previously regarding the effects of length of membership on incongruence and the decision to leave. As we can see, at least in the case of youth wings, incongruent members do not necessarily choose exit. One possible reason for members being more likely to be radical than aligned the longer they have been in the youth wing is that they come to rely less on party cues over time (Baldassarri, Reference Baldassarri2013; Lupia, Reference Lupia1994). Another is that a self‐reinforcing mechanism may be at work – namely, the longer a young person is politically socialized among fellow radical youth wing members, the more likely they are to see themselves as being closer to the positions of those peers than of the senior party. At the same time, people who have been members of the youth wing for longer are no more inclined to be radical than moderate (or to be moderate rather than aligned). The corresponding predicted probability plot, displayed in Figure 4, indicates that this is because the difference in likelihood of being a radical rather than a moderate is broadly stable over the length of membership.Footnote 15 In terms of our proposed mechanism that youth wing socialization is linked to members being more radical, it only appears to work if the member initially takes their cues from the senior party, by being aligned.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of being moderate, aligned or radical, depending on respondents’ length of membership.

Note: Based on Table 3.

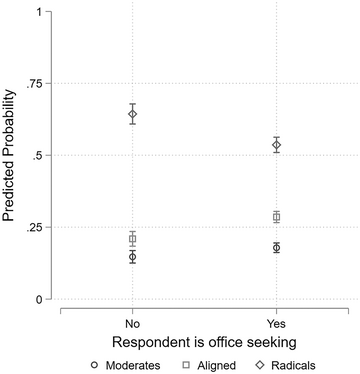

Hypothesis 2 focuses on the relationship between the candidate ambitions of youth wing members and their likelihood to be aligned, as opposed to radical and moderate. As Model 2 in Table 3 shows, those who would like to run as candidates are more likely to be aligned than radical, but are not more likely to be aligned than moderate. To investigate this further, Figure 5 illustrates the predicted probabilities of being office‐seeking or not according to ideological congruence/incongruence type. We see that the gap in predicted probabilities between radicals and aligned reduces significantly when we consider those who do not wish to run compared to those who do, while this is less the case when we compare aligned and moderates. The predicted probability of being radical is substantially higher for those who are not office‐seekers, at around 70 per cent, compared to 50 per cent for office‐seekers. By contrast, the predicted probability of being aligned is significantly higher for office‐seekers, at over 25 per cent, while it is around 20 per cent for those who are not office‐seekers. Our findings therefore partially support H2 in that having the aspiration to run for office influences members’ likelihood to identify as aligned compared to radical (but not compared to moderate). This fits with the mechanism proposed in our theoretical discussion, namely that those with aspirations for a political career would profess an ideological profile that makes them appear more in line with the senior party.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of being moderate, aligned or radical depending on whether the respondent is office‐seeking.

Note: Based on Table 3.

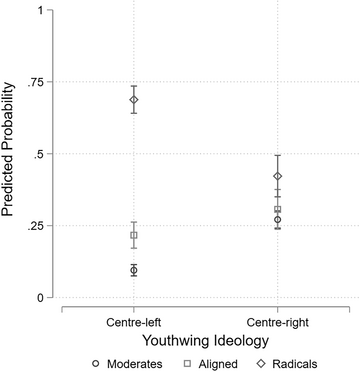

Moving on to our party‐level factors, Figure 2 already indicated that centre‐left youth wing members are more likely to be radicals than their counterparts on the centre‐right. Model 2 in Table 3 provides further evidence for this. As we can see, centre‐right youth wing members are significantly less likely to be radicals than aligned, compared to centre‐left youth wing members. They are also less likely to be radicals than moderates, again compared to those in centre‐left youth wings. Thus, we find strong support for H3. As this effect is the strongest in our models, we further explore the differences between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wing members in Figure 6. This shows that the predicted probability of being radical is almost 75 per cent among centre‐left youth wing members, while it is below 50 per cent among centre‐right ones.

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities of being moderate, aligned or radical depending on whether the respondent is member of a centre‐left or centre‐right youth wing.

Note: Based on Table 3.

The final hypothesis to be tested (H4) relates to the impact of the party having entered government or opposition following the most recent general election in each country before our survey. The models in Table 3 show that our three ideological types seem unaffected by whether the party achieved government or went into opposition. H4 is therefore not supported. It is interesting to note, however, that, although the coefficients are not statistically significant, their sign is negative among both moderates and radicals (relative to the aligned reference category), meaning that youth wing members seem to perceive themselves more as aligned when their party is in government.

Turning to the socio‐demographic controls, Table 3 shows that women are no more or less likely to be aligned, moderate or radical than men. This is an interesting result, since it goes against other studies which found that men are more likely than women to be ideologically incongruent (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; Lisi & Cancela, Reference Lisi and Cancela2017; van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012). Regarding age, we see no indication that younger members are more or less likely to be moderates, radicals or aligned. However, having completed tertiary education increases the likelihood of being more radical or moderate compared to aligned (Models 1 and 2), which might signal an effect of university education making individuals less likely to use information shortcuts offered by the party. Relatedly, those who have party members in their immediate families are more likely to be radicals than aligned, which again supports the idea that the more familiar you are with politics, the less you will rely on party cues (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017).

Our most striking finding is thus the difference between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings. To explore this and ascertain whether the other hypothesized effects are different depending on ideology, we re‐estimate our multinomial regression model interacting the youth wing ideology with the variables capturing length of membership (H1), office‐seeking attitude (H2) and party government status (H4) (see Tables C3‐C5 in Appendix C). Figure 7 plots the marginal effects of the interaction between length of membership and youth wing ideology, showing the effect of being in a centre‐right youth wing with centre‐left youth wings as the reference category. This provides a different perspective on our results. The longer members stay in centre‐left youth wings, the more likely they are to be radicals than moderates. In centre‐right youth wings, however, members who remain longer are more likely to consider themselves moderate than aligned. While it would require further investigation beyond the scope of this article to say with confidence why we find these differences, one possible explanation based on our other results is that, since centre‐left youth wings contain significantly more radicals than centre‐right ones, it may be the case that, if you spend a long time surrounded by a high proportion of radicals, it is more likely that you too will identify as a radical.

Figure 7. Marginal effect of youth wing ideology (H3) in interaction with length of membership (H1).

Note: Based on the models interacting youth wing ideology with the length of membership (see the full model in Table C3 in Appendix C). The full models interacting youth wing ideology with office‐seeking (H2) and government status (H4) can be found in Tables C4 and C5 in Appendix C, respectively.

At the same time, we do not find any distinct patterns pertaining to the career aspirations of youth wing members. The relationship between office‐seeking motivations and ideological congruence does not differ between members of centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings. Similarly, we do not find any significant differences between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings regarding H4, which concerned the government vs opposition status of the party after the most recent general election.

To corroborate the robustness of our findings, we performed several checks under different variable specifications and controlling for alternative explanations, all of which can be found in Appendix D. First, to ensure that our results are not sensitive to the operationalization of the dependent variable, we re‐ran the main analysis in the following ways: by adopting a different cut‐off point to delineate the aligned, allowing for a difference of 1 point on the scale (Tables D1 and D2); by measuring incongruence with a continuous variable which runs from ‐4.5 (self‐placement is perfect centrist, party placement is at the most extreme) to 4.5 (self‐placement is at the most extreme, party placement is perfect centrist) (Table D3); by measuring incongruence with a dummy variable distinguishing between aligned and incongruent youth wing members (Table D4); and by using dummy variables for the three ideological congruence/incongruence types as dependent variables (Table D5). Overall, these tests provide further support for our key findings: namely, members of centre‐left youth wings, as well as those who have spent longer in the youth wing and/or did not join because of office aspirations, are more likely to view themselves as radical.

Second, we computed a series of robustness tests concerning our main independent variables. Since length of membership and office‐seeking aspirations are individual‐level variables, we tested H1 and H2 including only individual‐level predictors and using party‐fixed effects rather than country‐fixed ones (Table D6). We also re‐ran the main model by keeping the variable measuring office‐seeking ambition as a four‐level categorical variable, to make sure that our results are not driven by the variable's dichotomization (Table D7). The main results hold across these models. To further probe our findings concerning H3, we re‐computed the analysis by substituting our variable measuring whether the youth wing is centre‐left or centre‐right with new variables: one which uses the left‐right party position of the senior party based on the CHES and the Global Party Survey (see Figure C1 in Appendix C) (Table D8); and two variables which gauge the level of intra‐party democracy of the senior party, based on the Political Party Database Project (Scarrow et al., Reference Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017) (Table D9). In line with our results, the first model shows that the more right‐wing a senior party is, the less likely it is that its youth wing members will perceive themselves as radicals rather than as moderates. The second model provides some support for the theoretical mechanism underpinning H3: youth wing members whose senior parties have greater assembly‐based intra‐party democracy are more inclined to consider themselves radicals (the same does not hold, however, when we examine plebiscitary‐based intra‐party democracy). To assess the robustness of our findings for H4, we re‐ran the main model by using a variable which measures whether the senior party's vote share had increased or decreased at the last election before the survey (compared to the prior election), instead of using the variable on government vs opposition status (Table D11). In line with our main results, this variable is not a significant predictor of ideological incongruence.

Third, to ensure the robustness of our results against party competition effects, we re‐computed the main regression by controlling for the vote share of the senior party (Table D12); and by controlling for the combined vote share of all other parties except the senior party, first on aggregate (Table D13) and then only for those parties in the same ideological camp (left or right) (Table D14). We also re‐ran the analysis by controlling for the degree of autonomy of the youth wing. We gauged this by taking whether youth wing members are not automatically members of the senior party as a proxy measure for ‘autonomy’ (Table D15). In addition, to examine whether our results are robust depending on the extent to which young people vote for the senior party, we re‐computed our models by including two controls: one measuring the share of young people among the senior party's voters (Table D16), and one measuring the share of senior party voters amongst young people (Table D17).Footnote 16 Our main findings are further corroborated by these tests. Finally, as length of membership and office‐seeking ambition are individual‐level characteristics that might be related, we checked for endogeneity issues by computing two new models with length of membership and office‐seeking ambition as our dependent variables. Table D18 in Appendix D shows that these two variables are not explanatory factors for each other, therefore there is no endogeneity problem.

Conclusion

In this article, we have addressed a question that has interested political scientists for over a century, namely whether grassroots members of parties ideologically align with their leadership (Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair2009; May, Reference May1973; Ostrogorski, Reference Ostrogorski1902; van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012). Traditionally, it was believed that the grassroots constituted the radical core of parties, unlike the more pragmatic elites who would seek to win elections by taking positions closer to the alleged median (and more moderate) voter. As Butler (Reference Butler1960, p. 3) put it over 60 years ago, this incongruence represented ‘the essential dilemma of party leaders in Britain, and elsewhere: their most loyal and devoted followers tend to have more extreme views than they have themselves, and to be still farther removed from the mass of those who actually provide the vote’. While empirical studies on curvilinear disparity (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989; Norris, Reference Norris1995) and on ideological incongruence (Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017; van Haute & Carty, Reference Van Haute and Carty2012) have broadly agreed that members are usually not in line with their party elites, ours is the first to investigate ideological congruence and incongruence by examining the latter's direction (towards the extremes or towards the centre).

To do so, we proposed a new typology, dividing members into ‘radicals’, ‘moderates’ and ‘aligned’, and set out a set of theoretical expectations for what shapes these positions based on members’ political socialization and party context. We then tested our hypotheses, using YOUMEM project survey data on over 4,000 youth wing members in six countries (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Ammassari, Valbruzzi, Bolin, Werner, Heinisch, Jungar and Wegscheider2024). In line with long‐standing beliefs about party members, and especially young members, our results showed that the majority of people in youth wings consider themselves more radical than the senior party. However, we are not dealing with a homogenous group either within or between party families. Notably, centre‐left youth wing members consider themselves more radical compared to the senior party than centre‐right ones do. In addition, we identified two individual‐level factors that differentiate radical members from the aligned. Those who perceive themselves as radical tend, first, to have spent longer in the youth wing, and second, they are less likely to have joined with office ambitions than those who consider themselves congruent with the senior party. In this sense, radicals and aligned appear as the most distinct groups among youth wing members, according to the individual and party‐level drivers of incongruence we considered. Moderates and aligned seem to be the most alike, while radicals and moderates differ primarily in terms of whether they are members of centre‐left or centre‐right youth wings. Finally, recent national election successes do not influence self‐perceptions of ideological congruence and incongruence.

Our research has several implications for understanding the ideological relationship between ordinary members and party elites. First, we have shown that members are not a homogenous group of radicals, but are divided into three ideological types, driven by different individual‐level and party‐level factors. This is at odds with depictions of party memberships as being more moderate and pliant groups than in the past (Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair2018). For example, in their last work on party organizations, Katz and Mair (Reference Katz and Mair2018: 68) departed from their earlier view of the more radical party on the ground to contend that ‘no longer ideologically disparate, as originally hypothesized by May (Reference May1973), and no longer necessarily enjoying conflicting interests and ambitions […] the membership is unlikely to challenge the primacy of the party in public office’. Yet, as we have shown, grassroots members remain ideologically disparate, and it thus does not so easily follow that they are unlikely to challenge the party in public office. For example, even allowing for the popular belief that people become more conservative as they get older (Peterson et al, Reference Peterson, Smith and Hibbing2020), if our results reflect a cohort effect rather than a life cycle one, then the relationship between future centre‐left party grassroots and elites in particular will be characterized by ideological incongruence. On this point, it would be worth looking at other party families to see whether our results apply also to them. For example, in more radical parties, there is presumably more space to be moderate and less to be radical than is the case in parties like ours, which are closer to the centre. In addition, future research could conduct surveys of youth wing and senior party members contemporaneously and use our tripartite typology to determine how older cohorts of party members on both left and right compare to their younger counterparts. This would provide us with valuable insights into how different generations of members align ideologically with their party.

Along with helping us better understand congruence and incongruence, our survey has also offered a unique perspective on the young people that participate in contemporary centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings. Given that many elected representatives come through their parties’ youth wings (Binderkrantz et al, Reference Binderkrantz, Nielsen, Pedersen and Tromborg2020; Hooghe et al, Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Ohmura et al, Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018), it would be worth looking further at the characteristics of those young members who are politically ambitious, to see whether they constitute a distinctive group beyond their greater congruence. Conversely, researchers could examine, especially through qualitative methods such as interviews, why those young people who do not align with the senior party nonetheless remain in them, and do not favour other ways of pursuing their political goals beyond party activism, as many of their contemporaries do (Sloam, Reference Sloam2014). Following on from the latter point, it would also be interesting to see how those who are incongruent participate in their parties. For example, are radicals and moderates as active as those who are aligned? Do they become dissatisfied with the party since they do not align with it and therefore participate less, or, like the Jusos members of the 1960s and 1970s (Braunthal, Reference Braunthal1984), does their incongruence lead them to participate more since they believe the senior party can be moved in their direction? On this point, future work might examine the role of individual youth wing leaders in shaping attitudes towards the senior party among their young members. For example, when youth wings leaders are more prominent and charismatic, their views of the senior party might be more impactful on members’ perceptions of congruence and incongruence.

Finally, we have investigated perceptions of ideological incongruence by asking youth wing members to locate themselves and their senior parties on a left‐right scale. Another approach to understanding this relationship would be to measure both youth wing members’ and the broader party membership's attitudes on specific policy issues, to see if they match what they think are their senior parties’ positions on those same areas. This could reveal which policy areas lead younger and older members to perceive themselves as congruent or not. For example, it may be the case that if youth wing members perceive themselves as aligned with their senior parties in most policy positions except the ones they really care about, that could still be enough to make them self‐identify as radicals or moderates. On the other hand, if they feel incongruent on one or more issues that they do not consider salient, they may still place themselves and their parties on the same position of the left‐right scale. Moreover, looking at specific policy issues could shed light on why the distribution of radicals, aligned, and moderates differs so noticeably between centre‐left and centre‐right youth wings. In sum, while our study has sought to delve deeper than the binary congruent‐incongruent framework in order to explore directions and features of incongruence, there remain many aspects to uncover in the complex relationship between members and their parties.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following colleagues for comments on previous versions and presentations of the paper: Max Grömping, Oskar Hultin Bäckersten, Ferran Martinez i Coma and Ariadne Vromen.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report there are no conflict of interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The YOUMEM project dataset on which this article is based will be published on Harvard Dataverse in January 2026.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: