Introduction

The ongoing tensions over migration that shifted Irish party support in 2023 looked likely to spill over into 2024. Opinion polls at the start of the year showed that Sinn Féin, once a seeming shoo-in to lead the next government, was in deep trouble as its electoral coalition had split on the issue of migration. A poll at the start of the year had Sinn Féin at 25 per cent, about 10 points lower than where it had been regularly polling. It was to be a year in which the Irish people would go to the polls three times for five separate elections and referendums. The most important one would happen at the end of the year, but the first trip to the polls for constitutional referenda would be consequential.

Election report

Referendums

Late in 2023, the government indicated that it would hold two referendums on 8 March 2024, International Women's Day, that would give effect to the recommendations of an earlier citizens’ assembly on gender equality and a subsequent Oireachtas (parliamentary) committee report on aspects of family life. These were seen by the government as ‘progressive’ changes to the constitution. One referendum—the Family amendment—was to change the definition of a family, which was based on marriage in the existing constitution to one that says a family could be based on marriage or ‘other durable relationships’. The other referendum—the Care amendment—was to remove the reference to a woman's place in the home and to remove the recognition of the essential role of mothers in the support of the family.

The existing provisions, particularly that which referred to a woman's life within the home, were widely regarded as anachronistic and symbolically problematic, even if there was no real substantive effect to them. When the proposed wordings for the referendums were released, there was less enthusiasm than might have been hoped, though early opinion polls suggested that the two amendments would pass comfortably. In response to this lack of enthusiasm, the minister sponsoring the amendments warned publicly funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that they would have to explain why they did not support these referendums (Bray Reference Bray2024). This veiled threat worked as some of those NGOs, such as the National Women's Council, stepped up their campaigning in response. With all the parties in the Oireachtas, bar one, indicating their support for the amendments, there seemed little fear of any surprises.

Referendum campaigns in Ireland require each side to be given equal access to broadcast media, and the state cannot spend money promoting any particular outcome. As such, despite the elite support for the amendments, the opposing viewpoint received plenty of attention. The opposition mainly came down on two aspects. One was the definition of ‘durable relationships’ in the Family amendment. The government struggled with a clear definition of this, and there was a lack of clarity as to whether it would have implications for those claiming asylum based on ‘family reunification’. While the government insisted there would not be implications, leaked advice from officials in the Department of Justice suggested that there would be. A second issue was the decision to remove mothers from the constitution through the Care amendment. It was viewed by many as a tokenistic gesture that devalued the vital role of mothers in society, while offering no new protections to replace the outdated language it sought to remove. On the left, those activists for better care also saw the Care amendment as weak, offering nothing concrete in terms of new rights for those in need of care or their carers.

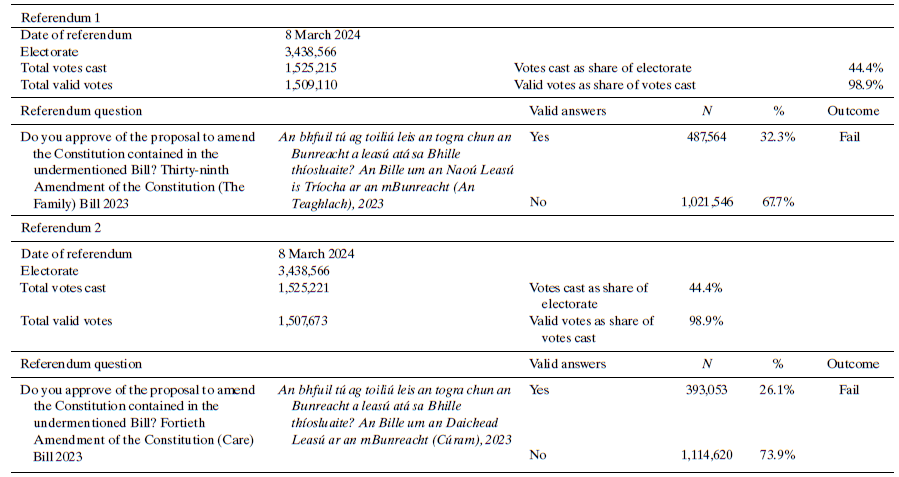

In response to the criticisms, the government moved from proclaiming that these were important amendments to arguing that they were textual ones with limited impact. It left voters wondering what the point was, except perhaps as an exercise in virtue signalling. On a turnout of less than 45 per cent, the two amendments were comprehensively rejected, with almost 68 per cent voting No to the Family amendments and a record defeat of almost 75 per cent voting No to the Care amendment (see Table 1). The defeats shocked the government, and the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, admitted his government ‘got it wrong’ and that he would ‘reflect’ on the outcome. Less than two weeks later, Varadkar announced his resignation as leader of Fine Gael and that he would step down as Taoiseach when his replacement was chosen by his party .

Table 1. Results of two referenda held on 8 March 2024 in Ireland

Source: Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage (2024) 1937 - 2024 Referendum Results https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of-housing-local-government-and-heritage/publications/1937-2024-referendum-results/

European parliamentary elections

The European Parliament elections took place on 7 June, the same day as local elections. Both are generally thought of as second-order elections. Local elections are seen as a useful way for parties to test out would-be Dáil candidates, whereas the European Parliament elections are often a route for senior politicians who feel they have little chance of moving up the political ladder in domestic politics. As a second-order election, Government parties should have been under more pressure, especially as other elections in 2024 showed incumbent governments being punished for cost-of-living increases, pressures as a result of immigration, and crises in housing.

Sinn Féin might have been expected to benefit more than other parties, especially as it had performed so poorly in 2019. Housing, which had been key to Sinn Féin's electoral success in 2020, was still unresolved. Nor had the government done or offered anything imaginative or radical to address the housing crisis. But with the breaking up of its electoral coalition largely because of immigration (see Arlow & O'Malley Reference Arlow, O'Malley, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025), Sinn Féin was under more pressure than it would have expected to be. There were candidates for several small parties usually described as ‘far right’ but perhaps more usefully thought of as conservative ethnonationalist parties. The mainstream parties called for better integration of immigrants, but Sinn Féin pivoted somewhat by calling for an end to ‘open borders’.

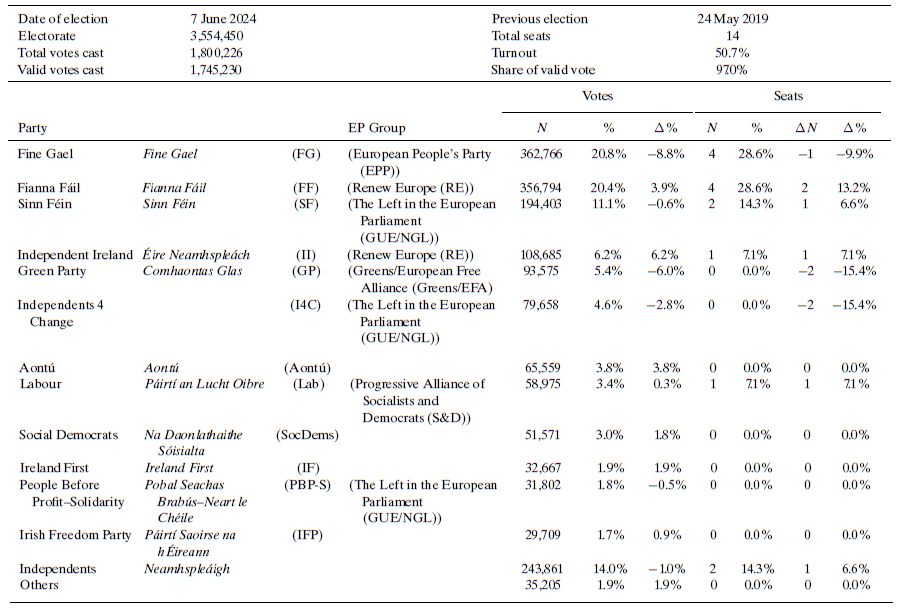

The election was also used by the government parties to criticise each other. In particular, the Green Party came in for criticism from Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael candidates. The Green Party was under considerable pressure in part because it had done so well in 2019 and mainly because entering government had not been popular for many of its erstwhile supporters. The results saw Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil receive just over 20 per cent of the vote each (see Table 2). While this was not a particularly good result, because of expectation management, both parties could claim to be pleased with the result. Fianna Fáil doubled its representation to four MEPs (Members of the European Parliament), but Fine Gael lost a seat. Sinn Féin gained a seat, but its vote tally of just 11 per cent was seen as disastrous given where it had been in the polls just a year earlier. The Green Party lost its two seats, and a new political party, Independent Ireland, a conservative populist party that espoused a tougher stance on immigration, won a single seat. None of the more extreme anti-immigrant parties polled particularly well, though collectively these micro-parties and candidates polled about 7 per cent, and this was also reflected in the local elections. None of the smaller moderate left parties did particularly well. The performance of the two main government parties, though hardly stellar, was significantly better than the main party of opposition, Sinn Féin. This outcome immediately heightened expectations of an autumn general election, which indeed came to pass.

Table 2. Elections to the European Parliament in Ireland in 2024

Notes:

1. Others include the National Party, Rabharta and The Irish People.

2. When Solidarity had a MEP (in 2009), they were part of the same group.

Source: Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage- election results, 2024 European Parliament Election Results, 7 August 2024 https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of-housing-local-government-and-heritage/publications/2024-european-parliament-election-results/

Parliamentary elections

In the autumn, there was an expectation that an election would be called after the legislation giving effect to the 2025 Budget had been passed. That budget could be characterised as an election budget with large increases in current and capital spending, combined with tax cuts, largely delivered through increases in tax band thresholds. These policies were possible because the Irish economy was still performing well, with high employment levels and strong growth, though worryingly, Ireland was highly dependent on corporate tax receipts from a small number of foreign, usually United States, multinationals. In advance of the election, a decision by the European Court of Justice forced Apple to pay €13 billion in tax to Ireland on foot of an earlier European Commission ruling. This meant that the Irish government had plenty of money to spend in advance of the election, and none of the opposition parties were under any pressure to explain how they would finance extra public spending. No party facing the electorate was explicitly calling for cuts in state spending.

However, it might have been a strategic mistake for the government parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, to engage in such high spending. Few voters take much notice of admonishment by the budgetary watchdog, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, which said pumping so much money into an already booming economy risked a repeat of the mistakes made in advance of the economic crash in 2008. But government parties, in particular Fine Gael, had campaigned in earlier elections on the basis that opposition parties could not be trusted with the state's finances and that it alone was responsible enough to manage the economy. In turn, Fine Gael was the party most voters thought best placed on that issue, followed by Fianna Fáil (Cunningham & Dornschneider-Elkink Reference Cunningham, Dornschneider-Elkink, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025). There was a series of minor scandals on public spending including a bike shelter at Leinster House, the seat of the national Parliament, that cost over €360,000. While this was a small amount in terms of the country's budget, it was indicative of waste in public spending. A bigger spending problem was the National Children's Hospital, which was by the end of 2024 years late and billions of euros over budget. It implicated the Taoiseach, Simon Harris, as he had been the Minister for Health when the contract was signed.

Still, Fine Gael went into the election full of hope and expectation. The replacement of Leo Varadkar as leader (see below) and the perception of successful local and European elections meant the new leader and Taoiseach, Simon Harris, had an air of electoral competence. Before this, there was concern within Fine Gael at the number of sitting TDs choosing to retire in that election—almost half the TDs that had been elected in 2020 (Reidy Reference Reidy, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025). Given the importance of incumbency, this was thought likely to be a significant drag on Fine Gael's electoral prospects.

When Simon Harris told the nation on 6 November that he would shortly request the dissolution of the Dáil for an election on 29 November, it put an end to months of speculation. Simon Harris was energetic and ubiquitous, and Fine Gael was on the front foot. Before the election, Harris was known in the media as the ‘TikTok Taoiseach’ due to his perceived communication skills, and the party centred its campaign on Harris as leader. The other parties’ campaigns were more low key, but opposition parties tried to emphasise government waste. Sinn Féin hoped that voters had forgotten or discounted the series of scandals that had caused problems for the party in the early autumn. Immigration also did not seem to come up as frequently at the doorsteps as it had in the early summer. So, it went into the final weeks with some optimism. Fianna Fáil made a virtue of its centrism and claimed that it was a party that could be trusted. The campaign itself was surprisingly uneventful, and there were no game-changing events. Yet Fine Gael's focus on Harris clearly failed. Though the party slogan was ‘a new energy’, Harris could not maintain that energy in the final weeks of the campaign, and he was found to be irritable at times. In what became one of the stand-out incidents of the campaign, Harris failed to show compassion to a distraught care worker while canvassing in Kanturk (County Cork), and this interaction was recorded by one observer and received millions of views on social media. As a result, Harris had to apologise for his behaviour. The party then pivoted back to the economy and focused on other senior figures, such as Paschal Donohoe, the Minister for Public Expenditure, in the last week of the campaign (McGee Reference McGee, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025).

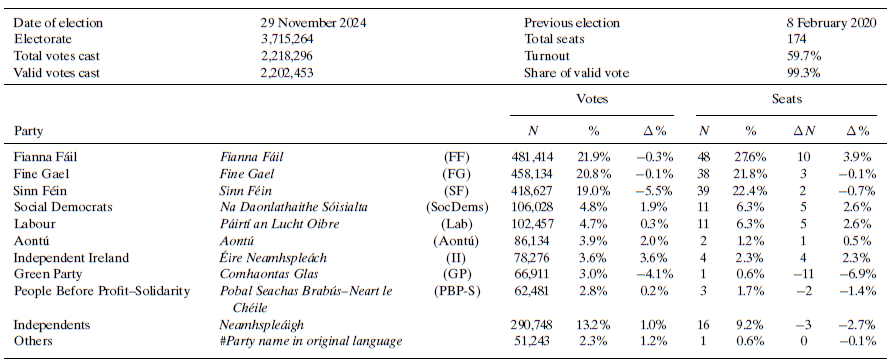

As with 2020, the election results were indecisive. For the first time since 2007, the status quo was broadly maintained. The two main government parties saw small losses in vote share, but as the largest party, Fianna Fáil garnered a seat bonus. The increase in the size of the Dáil—to 174 seats from 160—gave each party the sense that it had performed better. Even though nobody ‘won’ the election, each of the parties could claim a sort of victory. Sinn Féin recovered from its disastrous showing in June to return 39 deputies (see Table 3). Fianna Fáil on 48 seats was the largest party. Fine Gael with 38 seats did not implode at the last minute and recovered most of the seats of those incumbents who had stood down. Labour (11 seats) and the Social Democrats (11 seats) made modest gains, where each had potentially faced wipe-out. The Social Democrats’ popular leader, Holly Cairns, was unable to partake fully in the election campaign and leaders’ debate due to her pregnancy, and she gave birth on polling day. The gains for Labour and the Social Democrats mainly came from the Green Party and so remained within the ‘soft-left’. However, within weeks of the election, one of the Social Democrat TDs—Eoin Hayes—was suspended from the party for misinforming both the party and the public about the timing of his sale of shares in a former employer. Notably, the company in question was Palantir Technologies, a US multinational with close ties to the Israel Defence Force. Aontú (two seats) and Independent Ireland (four seats), two small conservative parties, both gained a seat. The radical left group, People Before Profit-Solidarity (three seats), lost two seats despite a slight increase in its vote share, primarily as a result of Sinn Féin's more effective constituency vote management. Independent candidates won 16 seats. Except for the Green Party, which lost all but one of its 12 seats, nobody ‘lost’ the election.

Table 3. Elections to the lower house of Parliament (Dáil Éireann) in Ireland in 2024

Notes:

1. The number of seats increased from 160 to 174.

2. Fianna Fáil's seat total includes the Ceann Comhairle (Speaker), who is automatically returned.

3. Others include: Irish Freedom Party, The Irish People, 100% Redress, National Party, Independents 4 Change, Ireland First, Right to Change, Liberty Republic, Party for Animal Welfare, Rabharta, Centre Party.

Source: Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025).

Though the results were as inconclusive as they had been in 2020, when it took 140 days to form a government, even before the final results had been declared, the shape of the new government was clear. Before the Christmas recess, the new Ceann Comhairle (speaker), Verona Murphy, was elected in a deal that Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael had done with a group of independent TDs. The negotiations on the formation of that government went into 2025, but at the end of 2024, the pubic knew the basic shape of the new government, a Fianna Fáil–Fine Gael government swapping out Green Party support for the support of independent TDs (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025). The level of fragmentation as measured by the effective number of parties was at a historic high (ENEP was 7.3). This seemed to reflect what might be the new normal in Irish politics (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025).

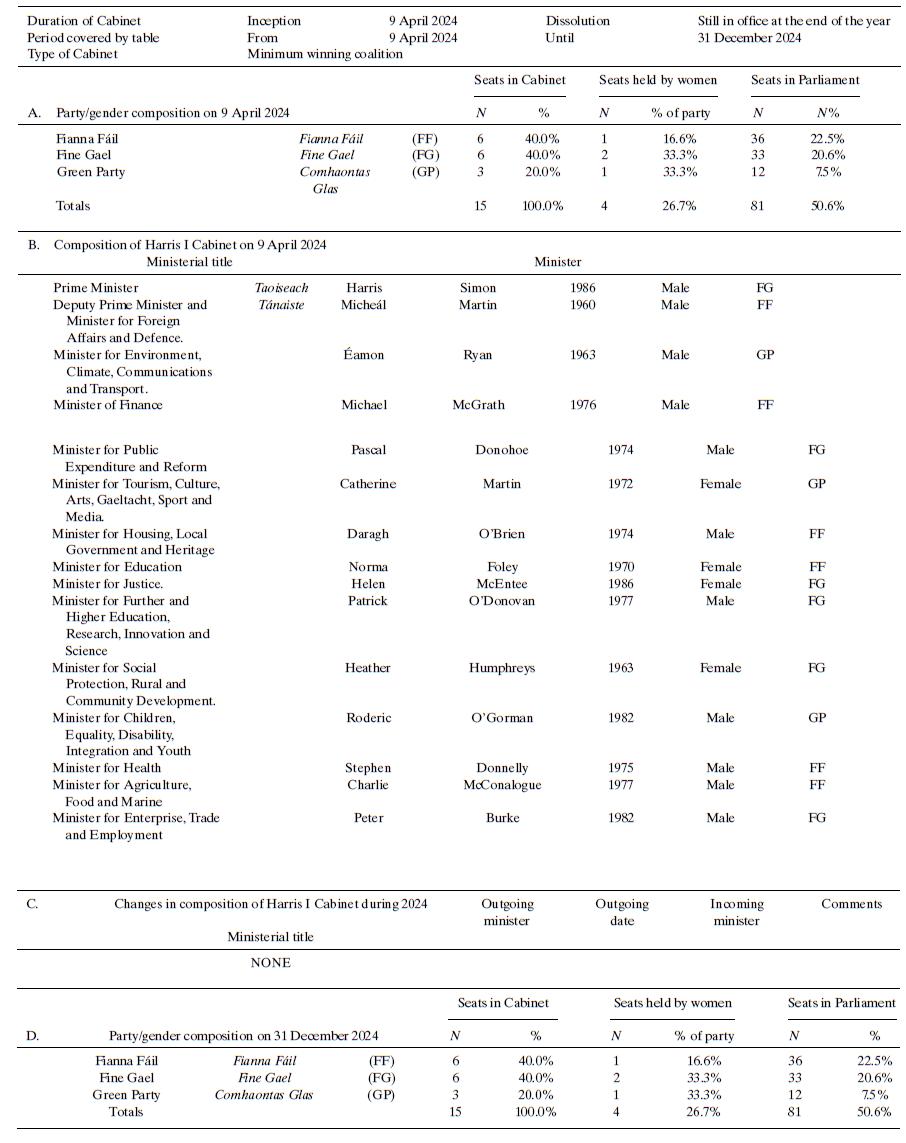

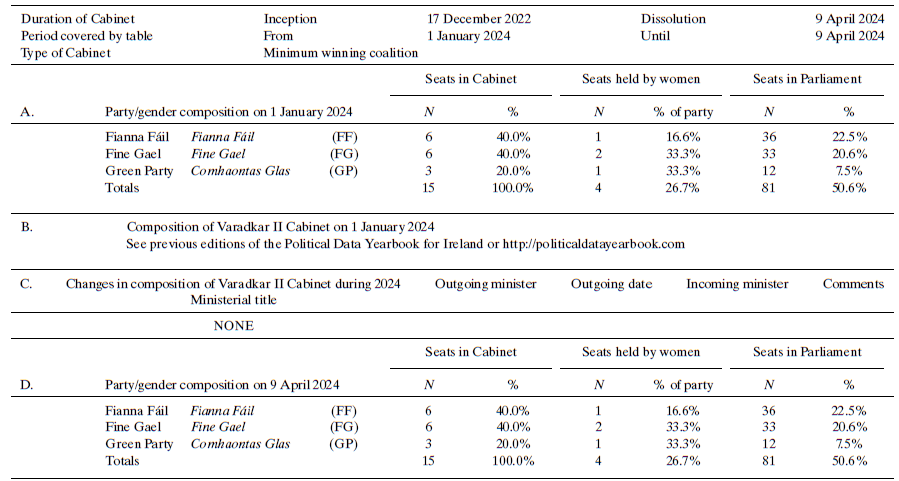

Cabinet report

As a result of the resignation of Leo Varadkar in March (Table 4), a new government was formed on 9 April with Simon Harris as Taoiseach. With Varadkar's resignation, another experienced minister, Simon Coveney, also indicated that he did not wish to be considered for appointment. Harris's new government made no changes beyond these two replacements, and all other ministers remained in the role they held under Varadkar II. This was largely a continuation of the existing government. This might have been surprising as Harris had emphasised that he wanted ‘to bring new ideas, a new energy and a new empathy to public life’ (Harris Reference Harris2024), but with so little time before the next election, Harris perhaps thought that shifting ministers might not yield any practical changes. One change came about as a result of the new European Commission. The Minister for Finance, Michael McGrath, was Ireland's nominee for the Commission, and he resigned his ministry on 26 June. He was replaced by his Fianna Fáil colleague, Jack Chambers (Table 5).

Table 5. Cabinet composition of Harris I in Ireland in 2024

Notes: Following the November general election, a new Dáil was convened on 18 December 2024. However, until a new government is formed, the previous Cabinet (Harris I) remains in office while coalition negotiations continue.

Source: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites, accessed on 18 May 2025.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Varadkar II in Ireland in 2024

Source: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites, accessed on 7 May 2025.

For the Cabinet composition of Varadkar II on 1 January 2024, see Arlow and O'Malley (Reference Arlow and O'Malley2023).

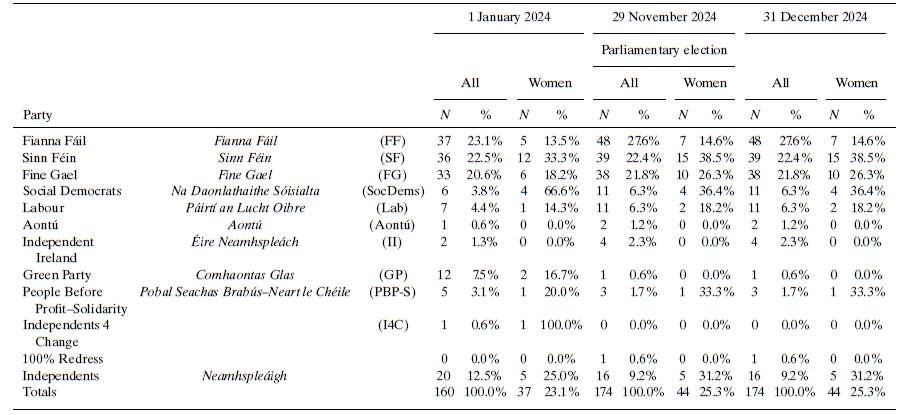

Parliament report

This election saw an increase in the gender quota, requiring every party to run at least 40 per cent women candidates. As a result, 44 women TDs were elected (see Table 6)—representing 25.3 per cent of the Dáil—a modest rise of just 2.8 percentage points, compared to the 2020 election when the quota was set at 30 per cent. Although all parties that qualified for state funding met the quota requirements, some parties appeared to adhere to the letter rather than the spirit of this law, often fielding new female candidates just to meet the quota rather than as genuinely competitive candidates (see Buckley & Galligan Reference Buckley and Galligan2020). Consequently, there is significant variation in gender balance among the mainstream parties in Dáil Éireann. For example, Sinn Féin leads with women comprising 38.5 per cent of its TDs, while Fianna Fáil trails behind with only 14.6 per cent of women TDs (see Table 6). Additionally, incumbency remains influential in elections, and most incumbent TDs are male. There are plans to introduce similar gender quotas in local elections, which may help to increase the number of women candidates advancing into the national Parliament.

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the lower house (Dáil Éireann) of Parliament (Oireachtas) in Ireland in 2024

Notes:

1. Fianna Fáil's seat total includes the Ceann Comhairle (Speaker), who is automatically returned.

2. The number of seats increased from 160 to 174 in the November election.

Source: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites, accessed on 7 May 2025.

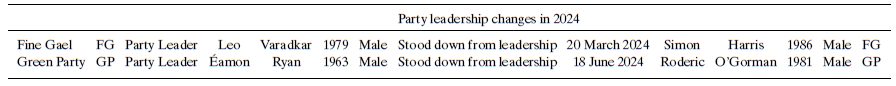

Political party report

On 20 March 2024, less than two weeks after the results of the referendums on Family and Care were confirmed, the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, made an emotional statement on the steps of Government Buildings flanked by his party colleagues. He said his reasons for stepping down were both personal and political but that he felt that he was no longer the best person to lead Fine Gael into the local and European elections taking place that June and the general election that had to occur within a year of his resignation. Though Varadkar had contested and won the leadership as the candidate best placed to expand Fine Gael's electoral coalition, this failed to materialise in the 2020 election and, with the exception of a Covid-19 bump, Fine Gael support was consistently below its support before he took over, and by 2024 was consistently polling at just about 20 per cent (Murphy Reference Murphy, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2025). The leadership election in Fine Gael did not materialise, as one candidate, Simon Harris, had amassed so many declarations of support from within the parliamentary party that, by the time the nominations closed on 24 March, no other candidate had entered the race. And so, the 37-year-old Harris became the party's leader and two weeks later was elected Taoiseach (see above). Harris was not seen as clearly aligned to any particular ideological position in a party that traditionally had both a conservative and social democratic wing. Thus, his choice was one for electoral success rather than any obvious directional shift in policy.

In the wake of the disastrous local and European elections for the Green Party, its leader, Éamon Ryan, announced his resignation (see Table 7). This was less of a shock as he had earlier hinted he might not be a candidate at the subsequent election. There were two candidates for the Green Party leadership. One candidate, Roderic O'Gorman, was a long-time party activist, a first-term TD (MP) and a government minister. As the sponsoring minister, he had been associated with the referendum defeats. Against him was a senator and junior minister, Pippa Hackett. What was more surprising was that Catherine Martin, the party's deputy leader, and once popular among the ‘fundi’ wing of the Greens, chose not to stand. In a vote of the party's membership, O'Gorman narrowly won, by 984 votes to 912.

Table 7. Changes in political parties in Ireland in 2024

Source: Electoral Commission website, May 2025.

There was another change in party compositions in the Dáil just weeks in advance of the general election when a prominent Sinn Féin TD, Brian Stanley, the chair of the high-profile Public Accounts Committee, resigned from the party. He claimed he was a victim of a ‘kangaroo court’ and was critical of party leader, Mary Lou McDonald, for her handling of an internal disciplinary process arising from a complaint from a party member. This was just another of a series of scandals enveloping Sinn Féin in the early autumn relating to internal party discipline.

With the election of the new European Parliament, three TDs resigned their seats in the Dáil to take up seats in Brussels. Kathleen Funchion of Sinn Féin, Aodhán Ó Riordáin of the Labour Party and Fianna Fáil's Barry Cowen all did so on 11 July. TDs are normally replaced through by-elections that must be called within six months of the vacancy arising, but the general election was called before this was required.

Institutional change report

In Limerick city and county, at the same time as the local elections, a mayor was directly elected by the denizens for the first time. This is a trial of what might be a solution for the weak local government system across the country.

Issues in national politics

The elections dominated the year, and it was in these that the main issues of housing, health and immigration were aired (see Election Report). Another issue that was important, though it did not feature heavily in the electoral campaign, was the ongoing war in Gaza. While the Irish government took what Israel regards as a hard-line against the country for its reaction to the 7 October attacks (including by recognising the state of Palestine), for some on the left in Ireland, the Irish government had not gone far enough. There were demands also to pass an Occupied Territories Bill to boycott goods from areas occupied by Israeli settlers, though this did not happen before the election.