1.1 Introduction

The Cycladic islands, which lie scattered in the centre of the Aegean (Map 1.1), have had periods of outstanding achievements, as in the Bronze Age and Hellenistic periods, which have put into sharp relief the supposed dispiriting lows in the Roman and Late Antique periods. Investigating the veracity of these assumed low periods is made challenging by a dearth of historical or literary evidence pertaining to the islands during these periods. When they are mentioned, it is largely in terms of their insularity – as havens for pirates, places of exile or targets for invasions. Islands are often the first to experience change and, while this can be both positive and negative, the positives tend to be overshadowed by the negatives. Furthermore, scholarship on the islands has commonly taken a top-down approach, in which they are viewed through a lens of passiveness and as pawns in wider machinations rather than as decision-making entities in themselves. However, as Baldacchino (Reference Baldacchino2008) warned, it is important not to overcompensate in attempting to move away from the top-down approach to the islands and place too much emphasis on their roles and importance in the broader context of study.

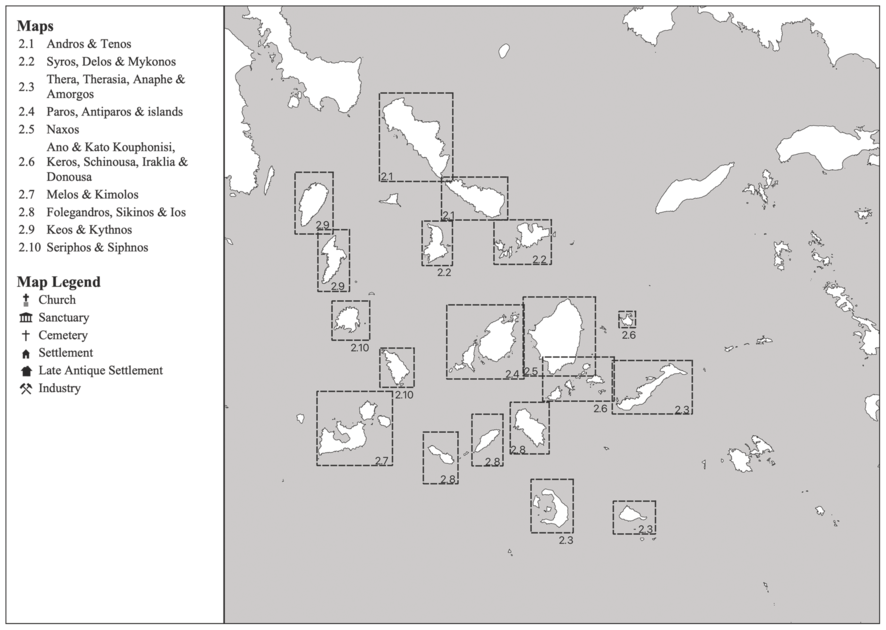

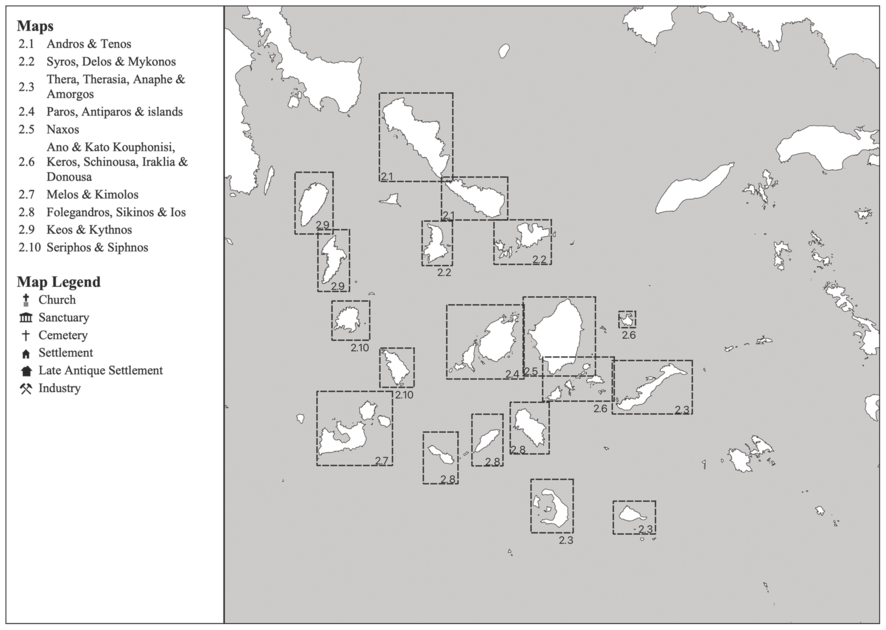

Map 1.1 Map of the Cyclades in the Aegean

The location of the Cyclades in the centre of the Aegean meant that they were often visited, although not always with the intention of staying. Strong winds regularly drove travellers to seek shelter on the islands or trapped them there for days on end. Two of those travellers were Cicero (Att. V. 12) and a pseudo-Nero, who accidentally wound up on Kythnos in a storm (Mendoni and Zoumbaki, Reference Mendoni and Zoumbaki2008, 26). Today, there are some thirty islands in the Cyclades that are substantial enough to be inhabited; the largest of these are Naxos (428 sq. km), Paros (195 sq. km), Andros and Tenos. Even though some of the islands are small, such as Schinousa (8.5 sq. km) and Kouphonisi (5.8 sq. km), their remoteness is mitigated by the fact that they are physically close to each other or to larger islands (Map 1.1). The most removed islands are Anaphe (S2) and Amorgos (S1) to the east and perhaps even Melos (S16) to the west. Although Delos was traditionally at the centre with the rest of the islands circling around it, according to the modern geographic designation, Paros is closer to the centre (Map 1.1).

The Cyclades are mountainous with varying sizes of coastal plains; while there were plenty of good harbours on Paros (S19) and Melos (S16), they were in short supply on the mountainous Sikinos (S24). As illustrated in Chapter 3, the larger islands had enough arable land to produce significant agricultural yields. However, large size does not always represent potential. For example, Tenos is so rocky that it is incredibly difficult to grow crops on the island, even on terraces. In fact, there is a note in Bernard Randolph’s (Reference Randolph1687) seventeenth-century account of the Cyclades of how Andros provided supplies to Tenos, suggesting that, in spite of its size, Tenos struggled to sustain its population. As Pliny and Strabo recount, the Cycladic islands had established reputations for different reasons; for example, Tenos was famed for its Sanctuary of Poseidon (S27), Anaphe for the Sanctuary of Apollo (S2) (Figure A.3) and Andros for the Sanctuary of Dionysus (S3) and the miracle of the wine-flavoured water in January. Keos (S11) and Kythnos (S15) were known for their ruddle and cheese, respectively, Siphnos (S25) and Seriphos (S23) for their defunct mines. Kimolos (S13) and Melos (S16) were notable for their clays and minerals, Naxos (S18) and Paros (S19) for their marble and wine and Thera (S28) for its agriculture. To what extent these traits endured in the Roman and Late Antique periods is a question that will be addressed in this work. The variety of islands, their size, landscape and locations will be explored in order to highlight their diversity and connectedness over time.

1.2 Islands: Scholarship, Travellers and Archaeology

In travellers’ tales, islands are commonly present, in mythic and/or real circumstances. They are seen as representative of the journey but are also depicted in contradictory ways – as welcoming and threatening, as places of calm and agitation, or as wild and civilized (Chamberlin, Reference Chamberlin2013, xiii). Just as individual islands have seemingly contrary characteristics so, too, do groups of islands. The Cyclades are often discussed as a monolithic group, with the result that individual islands are lost in generalizations of isolation.

Research on islands in the past was dominated by studies of ecology and evolution, and, even now, a brief skim through the Journal of Islands and Coastal Archaeology will reveal a striking preponderance of work on islands and their first settlers and prehistoric communities. In studies of boundaries as conduits and barriers, scholars have often turned to islands as naturally bound places (Ingold, Reference Ingold2000). Furthermore, there was a natural inclination to treat islands as laboratories for studies of cultural change and as marginal spaces (Di Napoli and Leppard, Reference Di Napoli and Leppard2018). However, this has sidelined both connectivity and the fluctuating nature of islands. While it is still the case that islands are used as case studies because of their defined spaces (e.g. Fitzpatrick, Rick and Erlandson (Reference Fitzpatrick, Rick and Erlandson2015), who note the potential for islands as a means of exploring diaspora), there is more value in examining islands for their accessibility and adaptability than has previously been recognized.

Studies of the Mediterranean have helped to shape views of the Cyclades and have contributed to our understanding of the context for ideas of connectivity and isolation. Some scholars, such as Braudel (Reference Braudel1972, 1238–9), argued for stagnation and resistance to change in parts of the Mediterranean; more recent work by Horden and Purcell (Reference Horden and Purcell2000), Broodbank (Reference Broodbank2013) and Concannon and Mazurek (Reference Concannon and Mazurek2016) argue for connectivity while maintaining community identity. These developments apply to island studies more generally (Fitzpatrick and Anderson, Reference Fitzpatrick and Anderson2008).

In recent years, views of islands across disciplines have begun to change. Instead of the traditional views of islands as insular and behind the curve in terms of adoption of trends, they are now seen more positively, particularly in light of resilience and adaptability. Scholarship on individual islands is common, but research on large groups of islands can be more challenging because of their inherent diversity, making evaluation of material difficult. However, the return on any analysis of island groups is of significant value, particularly in terms of shedding light on the interplay between regional and local processes. When archipelagos are viewed as ‘assemblages’ of their structures and cultures, their ever-changing interactions and networks are visible as a reflection of actions on the part of their residents (Shellar, Reference Sheller2009).

The Cycladic islands are a particularly interesting archipelago because of their biogeographical diversity and continuous occupation from the Mesolithic period onward. In this work, the challenge of making sense of the diversity of the islands and their communities in the Roman and Late Antique periods, to offer meaningful insights, is met through a detailed study of the archaeology from each island and application of network analysis. A full analysis of all the archaeological data is required, as, while networks can show the potential for contact, it is not always possible to judge the degrees of interaction that are dependent on social and physical factors that are themselves variables. In this respect, a variety of approaches to the Mediterranean are followed here: the first is Braudel’s idea of connectivity but without the strict sense of unified character as presented by Horden and Purcell (Reference Horden and Purcell2000), who give weight to the importance of regions and micro-regions. Additionally, human agency is emphasized, as Horden and Purcell (Reference Horden and Purcell2000) and Broodbank (Reference Broodbank2013) have done in their Mediterranean studies, to avoid the behaviourist approach of Braudel (Reference Braudel1972).

A central challenge of this work is to examine the scale and diversity of interactions and communities based on disparate evidence in order to shed light on the ordinary everyday, as well as on extraordinary events. It is timely to undertake this work now as extensive publications of epigraphic material and increasing analysis of excavation and survey data make it viable. As we will see here, certain islands played different roles within the wider networks of trade, tourism and pilgrimage while others may not have participated directly but indirectly, through other islands. In this respect, a diachronic view of the Cyclades shows that they conform to the process of dialectical change, where apparent paradoxes are incorporated into society. Islands have a robustness that makes them strong enough to absorb change without impacting on the security of their own identity. This may come from the sense of uncertainty that island communities naturally live with (we can see this in contemporary islands facing climate change, for example) and is understood in terms of resilience.

Antiquarians began a long history of interest in the Cyclades in 1675, when the French archaeologist Jacob Spon visited the islands with the British botanist George Wheler, who made detailed descriptions of the archaeology of Delos. Randolph published a description of the islands in 1687, which included a note about the overriding importance of silk production on Andros. In his description of Paros, Randolph recounted the story of the master craftsperson of Ag. Sofia in Constantinople travelling to Katapoliani on Paros to inspect the work of his apprentice, who was himself a Parian. He was so jealous of the apprentice’s skills that apparently, he threw himself off the church. Another botanist, Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, travelled through the islands during 1700–2 while collecting specimens in the area of the Eastern Mediterranean. He described the islanders of Mykonos in the course of 1718 desperately trying to dispose of a vampire who would not stay dead (Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2006, 468–70). Charles Robert Cockrell also visited the islands, in 1811–12, and faced issues with mutinous sailors, as well as nearly losing his dog down a well (Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2006, 460). Ludwig Ross, the first professor of archaeology at the University of Athens and the first inspector of antiquities in Greece, undertook a series of explorations on the islands, recording sites such as the Mausoleum on Sikinos (S24) and publishing a booklet on the archaeology there (Palagia, Reference Palagia, Goette and Palagia2005). Theodore and Mabel Bent travelled extensively throughout the Cyclades, and Theodore published a seminal book on the islands, The Cyclades; or, Life among the Insular Greeks (Bent, Reference Bent1885a), and undertook some of the earliest excavations in the islands, on Antiparos. Here, his haphazard extraction of material was focused on two sets of graves. Mabel Bent’s diaries of their travels together were published in 2006 by the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies, London. Her Chronicle in the Cyclades starts with the word Υπομονή, translated as ‘patience’, which is revealing of her experiences through the archipelago. Her diaries set the scene of island life in the late nineteenth century and the difficulties they experienced there, such as bugs, bad rain and varying qualities and quantities of food. She describes visiting sites, for example, travelling to Grammata (Syros) (S26) on a mule; while there, her husband translated some of the inscriptions (Bent, Reference Bent and Brisch2006, 8–10). She also mentions that ‘quantities’ of things from the graves of Ellenika on Kimolos (S13) (Figure A.11) are in the British Museum (Bent, Reference Bent and Brisch2006, 17). The couple collected plenty of objects, such as Cycladic figurines, terracottas and pottery from islands such as Melos and Paros.

Later, in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, several histories and archaeologies of the islands appeared, including those by Lacroix (Reference Lacroix1853) and Ross (Reference Ross1912). Ferdinand Dümmler undertook some of the first excavations in the Cyclades, on Amorgos (S1), and Pollak worked especially in Siphnos (S25) and Syros (S26) (Vasilikou, Reference Vasilikou2006, 15–16). The earliest Greek excavations were focused on Rhenia (S21) and Delos (S5), which included the excavation of graves and the Shrine of Herakles (Vasilikou, Reference Vasilikou2006, 15–16). Tsountas dug at Amorgos (S1), Paros (S19), Siphnos (S25) and Thera (S28). A Greek archaeological team began work on Delos in 1837; this team was followed by the French, who began their focused research on the island in 1873 (Figure A.7). The British followed, starting work on Melos (S16) in the late 1800s. Deschamps began excavations in 1888 at Minoa, Arkesine and Aigiale on Amorgos (S1) (Marangou, Reference Marangou, Jentel and Deschênes-Wagner1994, 372). In 1903, Demoulin and Graindor, a Belgian team, began their excavations of the Sanctuary of Poseidon at Kionia on Tenos (S27), exposing the remains of the temple, fountain and mosaics (Figure A.42). By the time these systematic excavations had begun, many Cycladic sites had already been looted, random holes excavated by visitors and residents and considerable amounts of Cycladic material, especially figurines, exported or “gifted” abroad.

Since this early work, research excavations have been undertaken on sites that have had Roman occupation, such as the Sanctuary of Poseidon on Tenos (S27) (Étienne, Reference Étienne, Braun and Queyrel1986, Reference Étienne, Braun and Queyrel1990), Palaiopolis on Andros (S3) (Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa, Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa2007) (Figure A.4) and Ancient Thera (S28) (Von Gaertringen, Reference Von Gaertringen1899, Reference Von Gaertringen1904) (Figure A.44). Large-scale surveys were carried out on Keos (S11) (Mendoni and Papageorgiadou, Reference Mendoni and Papageorgiadou1989; Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani, Reference Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani1991), Keros (S12) (Renfrew et al., Reference Renfrew2022), Kythnos (S15) (Mazarakis Ainian, Reference Mazarakis Ainian, Mendoni and Mazarakis Ainian1998), Melos (S16) (Renfrew and Wagstaff, Reference Renfrew and Wagstaff1982) and Therasia (S29) (Palivou and Tzachili, Reference Palivou and Tzachili2015). Smaller or single-person surveys have been carried out on Andros (S3) (Koutsoukou, Reference Koutsoukou1992), Naxos (S18) (Érard-Cerceau et al., Reference Érard-Cerceau, Fotou, Psychoyos, Treuil, Dalongeville and Rougemont1993) and Paros (S19) (Bruno, Reference Bruno, Schilardi and Katsonopoulou2010). A survey of Anaphe has yet to be published. Many sites and buildings, such as Karthaia on Keos (S11) (Figure A.9), Ancient Thera (S28) and the Klima theatre on Melos (S16) (Figure A.13), have been the focus of recent conservation work. Rescue excavations in urban spaces dominate the recent archaeological work on the islands, and although there have been some new surveys (e.g. on Keros (S12) and Naxos (S18)), there is still less rural than urban data available.

1.3 Methodology and Approach

The aim of this work is to present a synthetic study of life on the islands in the Roman and Late Antique periods from a bottom-up perspective. Central to this intention is the first-time compilation of all the archaeological data from the Cyclades in these periods. Network theory provides a means of combining the disparate types of surviving evidence to highlight a diachronic view of the life on individual islands that are also part of an archipelago in a wider Aegean context. Theories of globalization, Christianization and resilience, will be applied to give agency back to the people who lived and worked on the islands as part of the Mediterranean in this period.

Research on the Cyclades during the Roman period has seen a resurgence. Work on the islands by scholars noted earlier has inspired new considerations of the Cyclades’ roles in the broader context of the empire, with a focus on the epigraphic data. Nigdelis (Reference Nigdelis1990) and Raptopoulos (Reference Raptopoulos2014) have produced significant studies of the political and economic history of the islands: Nigdelis focused on the evidence for changing sociopolitical and religious structures; Raptopoulos focused on economic and political histories. Additionally, separate studies of onomastics (Mendoni and Zoumbaki, Reference Mendoni and Zoumbaki2008, Mendoni and Zoumbaki Reference Mendoni and Zoumbaki2023.) and Late Antique Greek inscriptions (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000) have been published. These volumes provide fundamental resources for the study of the populations of the islands. Le Quéré (2015) provides an extensive account of the islands in the Roman period, from the first century bce to the third century ce, with a focus on their relationship with Rome. Her book is a positive contribution to the idea of the renewal of the islands in the Roman period, helping to dispel some of the negative views of decline. Le Quéré dismisses some of the traditional ideas of deterioration on the islands through a re-examination of the archaeology (in particular architecture) and history. Her overarching focus is on civic structures, imperial cult and discussions of how the islands were treated as a unit (through economic factors, minting coins and imperial cult).

More recently, synthesis of Cycladic material from the Roman and Late Antique periods has begun, with work by Gaitanou (Reference Gaitanou, Bonnin and Le Quéré2014) on grave monuments, Zoumbaki (Reference Zoumbaki, Bonnin and Le Quéré2014) on traders and Stavrianopoulou (Reference Stavrianopoulou, Rizakis, Camia and Zoumbaki2017) on women, families and social mobility. Le Quéré has published on the Agorai of major cities such as Thera and Melos (Reference Le Quéré and Γιαννικουρί2011), on patronage in the Cyclades (Reference Le Quéré2014) and on Melos as an economic hub (Reference Le Quéré and Roselaar2015b).

Altogether, this work has made considerable contributions to countering the views of the islands as a single-entity, poverty-stricken backwater. However, the Late Antique period remains poorly understood and there are still significant questions that need to be addressed concerning the relationships between the islands themselves and Rome. While ceramic analysis is growing, with studies such as those of Bournias (Reference Bournias, Poulou-Papadimitriou, Nodarou and Kilikoglou2014) on lamps and Raptopoulos (Reference Raptopoulos2014) on pottery, there is still much more material to be followed up, particularly concerning topography, the nature of religious practice on the islands, craftspeople, networks and communications all across a diachronic period.

Increases in survey and excavation work on the islands facilitate more in-depth analysis of specific groups of material (pottery, mortuary data, etc.), as well as diachronic views, than have been possible before. The work of the Small Cycladic Islands Project (SCIP) which has surveyed all the inhabited islands of the Cyclades will add significantly to the diachronic knowledge of the occupation of the islands. Through a holistic examination of the archaeological data pertaining to the Roman and Late Antique periods, as presented in the gazetteer, it is possible to address some key questions concerning diachronic continuity and change.

The first step in this study is the compilation of the first ever gazetteer of archaeological sites in the Cyclades dating to the Roman and Late Antique periods based on original excavation and survey reports, travellers’ accounts and personal observation (Appendix 1). This will form a key element of data for analysis to gain new and enhanced insights into the economy, society and religion of the islands that, to date, have been largely based on epigraphic and historical data. This analysis, together with information on the topography and environment of each island will enable a foundational understanding of each in terms of resilience, networks and potential for economic development. The significantly uneven level of archaeological data for the Cyclades during this period was balanced somewhat by visiting all the sites with Roman and Late Antique evidence. As such, while it is not possible to provide a full and even account of, for example, mortuary data for every island, there is enough data from the detailed catalogue to address the bias. The analysis of this fundamental data enables a focus on connections within and between the islands and the empires in which they were active.

A thematic approach enables a broad and focused view of the islands as a whole and a way of bringing together the disparate types of evidence pertaining to different islands. This means that not every island will be considered in the discussion in an exhaustive way. Delos and Rhenia are included in the analysis, but it should be noted that both are somewhat atypical in their roles as sacred island and burial place respectively. The archaeological data will form the basis of the discussion, which means, for example, that while Melos and Paros will figure significantly in terms of economy, islands such as Tenos and Naxos will provide more data in terms of religious activity. Late Antique activity is particularly dense on Naxos, and even smaller islands such as Gyaros are discussed according to evidence pertaining to them – in this case, exile.

1.4 Insular Cyclades?

Preliminary analysis suggests that at least some of the Cycladic islands were precocious in their recovery following the collapse of Delos and the ensuing upheaval in the Aegean in the first century ce. Contrary to expectations of decline, many islands thrived as part of the Roman Empire. Moreover, the islands appeared to have been pivotal in trade networks and in the spread of Christianity to the Greek lands to the east. How and why this was the case can be seen through a detailed examination of the archaeological evidence of each individual island. By applying ideas of resilience, it is possible to see how, even with the inherent levels of uncertainty on the islands, they were able to flourish. Given the natural diversity of the islands and the inconsistencies of the archaeological records, the use of network analysis helps to examine the variety of relationships between the islands that underpinned their vitality. Furthermore, a detailed examination of the networks will reveal high levels of connectedness over time, contrary to views of insular isolation that have dominated understandings of these islands in these periods. An examination of the individual islands, particularly with consideration to the idea of islands as assemblages, within the wider Mediterranean context, helps to counter an assumed uniformity and expectations of change and decline on the islands.

1.4.1 Networks

Network analysis enables a means of investigating individual islands and groups of islands, as well as their connections over a diachronic period, from the bottom up. ‘Network analysis’ is something of an all-encompassing phrase for a wide range of analysis of relationships (Isaken, Reference Isaken and Knappett2013, 43). It is not always necessary to take computational approaches and, in many respects, the process of recognizing and establishing nodes and links is a means of generating concepts of connectivity through movement of material, people and ideas (Brughmans, Reference Brughmans2010).

Network connections can be organic or manufactured, individual or organizational, and they can be both static and dynamic (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman, Alcock, Egri and Frakes2016). Research, survey and excavation on the Cyclades has resulted in a significant amount of data covering primarily urban and some rural space becoming available. This makes an application of network analysis to the archaeology of the islands in the Roman and Late Antique periods not only possible but valuable.

In the Hellenistic period, Delos (S5) was the centre (hub) of a Mediterranean religious and commercial network. Widescale communication between locations would have helped to create nodes along the network known as phase transition. DeLanda (Reference DeLanda2011) uses the term phase transition to define a process of perceptible change that is the result of accumulated diverse interactions as opposed to a sudden change. Furthermore, phase transition explains the situation of neighbouring locations benefitting from the success of a hub. The economic vitality of islands such as Tenos, Paros and Naxos in the Hellenistic period is likely due, in part, to phase transition from Delos (Map 1.1). When a hub is destroyed, the impact on the network can cause it to shatter and the result is usually a number of smaller networks. The diachronic analysis of the islands in the Roman and Late Antique periods suggests that this was the case on the Cyclades. After the collapse of Delos, the islands’ resilience came into effect and islands such as Paros and Melos were able to form their own networks. Application of network analysis to the pottery will provide insights into relationships between islands and externally help to shed light on their economy in the Roman and Late Antique periods, as Nikolakopoulou and Knappett (Reference Nikolakopoulou, Knappett, Laffineur and Greco2005) did for the Bronze Age. Furthermore, network analysis enables a local perspective rather than the more common top-down approach, as Constantakopoulou (Reference Constantakopoulou2007) had, to enable a view of the islands independent from the more common Athenian perspective. This in-depth examination of Roman and Late Antique networks will complete our understanding of a number of complex changes in these periods, including the creation of a provincial system, economic growth and religious change.

Preliminary studies have shown the different roles that islands can play in the wider network, either through voluntary (such as tourists or pilgrims)Footnote 1 or forced (such as exiles)Footnote 2 participation (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman, Alcock, Egri and Frakes2016). In this project, these studies will be developed through analysis of the epigraphic data (Mendoni and Zoumbaki, Reference Mendoni and Zoumbaki2008) to try to establish personal, economic and political connections. Analysis of portable objects – including lamps, amphorae and imported and local pottery for ceramic supply patternsFootnote 3 – will contribute to defining evidence for small-world (local) and scale-free (imperial participation) networks.

The Cycladic assemblages do not provide enough data in one element of material culture to make the application of statistical analysis beneficial. However, it is through the application of network analysis to Cycladic material culture that this work challenges the common view that the islands became more insular over time; it will be used as a means of countering the usual history written from anecdotes about pirates and exiles. Network analysis helps to reveal the key factors that determined the Cyclades’ distinctive trajectory in the Roman and Late Antique periods. As such, this approach provides a useful means of examining the data, within its topographic context, and providing a framework for more detailed analysis of economy, religion and individuals, from local elites to craftspeople.

Detailed analysis of settlement patterns (Chapter 2) and island economy (Chapter 3) will allow an understanding of the extent to which islands (such as Paros and Melos) were equipped to, and did, participate in the wider imperial financial networks. Topographic data, along with the archaeological evidence for production and processing, will be drawn on to present a picture of island economies. Imported ceramics found on the islands will provide more specific corroboration for external network connections. In the Hellenistic period, religious and economic networks went hand in hand with Delos as the hub. In the Roman period, the sanctuaries of Poseidon and Amphitrite at Tenos (S27) (Figure A.42), Apollo and Athena at Keos (S11) (Figure A.9), Dionysus on Naxos (S18) (Figure A.23) and of Dionysus on Andros (S3) were renowned, and the evidence of investment there is indicative of the range of foreign visitors these islands attracted as a result (Chapter 4). The prosopographical evidence is particularly apposite for shedding light on network connections between islands, as well as beyond, created by individuals (Chapter 5). The visible families and individuals are normally from the elite classes, exiles, tourists, officials, businesspeople, and so on; where possible, evidence for a wider representation of Cycladic society will be drawn on to include women, craftspeople, freedmen and even slaves.

It is clear from the epigraphic, literary and archaeological data that the islands continued to be well networked in the religious context, which may help to explain why they were home to some of the earliest Christian communities in the Aegean. A diachronic view shows how well connections between the islands and with the empire were sustained or not, from the early imperial period to the seventh century. Furthermore, such an analysis sheds light on the relationships between urban and rural spaces in the Roman and Late Antique periods.

When the islands are examined through a framework of network analysis, they can be viewed as discrete entities (micro view) as well as the archipelago (macro view) while at the same time viewing both the micro and macro participation (or not) in the wider Roman and Christian empires. It is likely, as will be seen from the final analysis, that multiple network connections contribute to the resilience of an island or archipelago. Network analysis allows a textured view of the Cyclades as part of the Roman Empire; one that sees some islands (like Melos) actively participating, others being forced to engage (for example, through accommodating exiles), while others may have been passively disinterested. Understanding network connections as manifested through church officials, local population or foreign pilgrims enables a fresh understanding of Christianization processes. Analysis of the material culture allows us to see whether connections were made through networks or a more pervasive presence. This analysis then sheds light on the impact of globalization and Christianization, which are entangled with concepts of connectedness.

1.4.2 Resilience

Resilience is both a process and theory, and several disciplines now work on areas of individual and community resilience. The lack of attention given to the Cyclades in the Roman and Late Antique periods is partly because of mistaken assumptions that they went into significant decline in the first century bce and, because they were so inconsequential, they could not have been of any value in the wider Roman Empire. However, when the islands are viewed with resilience in mind, quite a different hypothesis is open. Resilience theory focuses on the way in which an individual or a community deals with challenges and not the type or strength of adversity. While psychologists have moved forward discussions of resilience in individuals, it is clear that much of the individual resilience was dependent on communities and other external factors, such as culture (Fleming and Ledogar, Reference Fleming and Ledogar2008). Attention to community resilience has proved particularly important to ecologists, who were among the first to apply the concept of resilience to understand how swiftly disasters, as well as long-term events, are dealt with (Rose, Reference Rose2017, 19). In this respect, islands are well known for their resilience, particularly in the face of climate change.

Definitions of resilience vary considerably (Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2015, 543). However, across most disciplines, there is fundamental agreement that it signifies ‘to rebound’ and the ability to absorb and adapt to change. Adaption is often viewed in negative terms, that is to say, with a focus on what is lost rather than what is gained (Pelling, Reference Pelling2010, 9). Petzold (Reference Petzold2017, 25) notes that resilience is a complex system and one that is active and liberal. Although some scholars argue that repeated incidents (both natural and manufactured) could make islands more vulnerable (Cutter et al., Reference Cutter, Barnes, Berry, Burton, Evans, Tate and Webb2008, 599), a more positive view of ‘resilience reintegration’, in which experience of challenges results in a positive growth development (Fleming and Ledogar, Reference Fleming and Ledogar2008), is now more commonly held. Cultural resilience, as defined by Holtorf (Reference Holtorf2018), refers to the ability of a ‘cultural system’ to absorb and adapt to change and for that cultural system to be sustained by the embracing of continuity and change. In this respect, aspects of resilience resonate with complexity theory, which is applied in this study (and before) to argue for the smooth adoption of Christianity, and particularly at busy locations such as ports (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman2015a).

An inherent resilience exists on islands that makes them strong enough to absorb change without impacting the security of their own identity. This may come from the sense of uncertainty with which island communities naturally live, making them prepared for adversity while at the same time having a propensity to absorb and make the most of change. Furthermore, different agents (local and global) can be identified in building resilience (Olwig, Reference Olwig2012, 112). This is particularly pertinent in the Cyclades, which were part of a wider imperial system, but maintained strong local identities, which echoes processes of globalization (discussed in Section 1.4.3).

In this study, resilience theory is used as an approach to the archaeological data. Rather than reading change as negative or even in terms of decline, concepts of resilience help to show how the archaeology can be read in terms of vitality. In turn, this enables to us to see how individual communities were able to thrive and absorb change, even after something as significant as invasion or religious change, and sometimes even show signs of growth.

1.4.3 Globalization

As noted earlier, the traditional view of the Cyclades is one of disconnect, that these islands had little agency or autonomy in the Roman Empire and as such they were not active participants within the empire. This out-dated view arises in part because of past misapprehensions of the Roman provinces as Romanized. Romanization implies a top-down imposition of control and cultural preferences without choice (Sweetman Reference Sweetman2007, 65). This has led to out-dated ideas of forced participation if it was of benefit to the empire and side-lining if it was not.

While traditional views of romanization generate a sense of imposition, theories of globalization have been seen as a more inclusive approach, in which cities and provinces have agency to make choices about their participation or not in the globalized empire. The application of globalization theory to available archaeological and literary data still needs advancement, in part because of the lack of uniformity of meaning and application in this context or indeed even in contemporary terms (Pitts and Versluys, Reference Pitts and Versluys2014). In 2006, MacGillivray noted that without even considering other languages, there are ‘3,300 books in English in print on the subject of globalization’. Furthermore, some scholars argue that it is too modern a phenomenon to be appropriate to an ancient context (Giddens, Reference Giddens1990).Footnote 4 However, this has been effectively challenged Hingley (Reference Hingley2005), Pitts and Versluys (Reference Pitts and Versluys2014) and Morley (Reference Morley, Pitts and Versluys2014). Even in terms of economic and sociological studies, globalization has a variety of definitions. For example, Jones (Reference Jones2006, 112) has suggested that it is ‘the growing interconnectedness and integration of human society at a planetary scale’. Scholars such as Hitchner (Reference Hitchner2008) and Gordon (Reference Gordon, Concannon and Mazurek2016, 135) agree with Jones’ definition. Ritzer (Reference Ritzer2007) focused on elements of consensus, of which there were more than at first appeared; in his edited volume, contributors noted accelerating efficiency of connection, interconnectivity, and encompassing of space. Often, scholars refer to globalization in terms of universal connectedness, and in doing so express the result of globalization rather than the motivation or process. The focus of this present work is on the active part of globalization; that is to say, the creation of connections and networks on a variety of levels.

When working with interpretations of archaeological material, I favour Waters’ (Reference Waters1995, 3) definition who notes that it is a social process where geographical restrictions on social and cultural life begin to erode and there is an increasing awareness of the erosion amongst the population: ‘A social process in which the constraints of geography on social and cultural arrangements recede and in which people become increasingly aware that they are receding.’ While connectedness remains fundamental, the sense of awareness reinserts the element of choice in the process. The interconnectedness that globalization brings means that events in one area will result in unavoidable impact in another. However, individuals have different ways of integrating with, acknowledging or avoiding it, depending on a range of geographical, social, economic and political factors. It should be stressed that globalization is not a uniform practice and nor are its outcomes, even if that is the objective (Macgillivary, Reference Macgillivary2006, 10).

Furthermore, Gray (Reference Gray, Lechner and Boli2004, 22–4) notes that, for some, the idea of inclusivity easily morphs into the imposition of a ‘universal civilization’ based on Western ideals. Although later proponents of the Enlightenment like Marx and Jefferson believed that cultural diversity would naturally come to an end with increasing connectedness, this is markedly not the case. Contrary to their beliefs, a single market creates a sense of insecurity and rivalry, in part because of the way inequalities are highlighted. As Gray (Reference Gray, Lechner and Boli2004, 24) further argues, one of the results of globalization is the formation of ‘indigenous types of capitalism’ that promote diversity.

Globalization can create opportunities for people to participate directly or indirectly, or not at all. Globalization processes allow for multiple communities to occupy the same kinds of spaces, be they individual islands, archipelagos or land masses, without necessarily conforming to all aspects of the cultural, social or economic activities. Waters’ (Reference Waters1995) definition is particularly appropriate in terms of the idea of awareness of the potential or threat, and, as such, individuals can contribute to shaping the process. Furthermore, it is a useful means of understanding the multifarious relationships that islands, with all their dichotomies, could have. Island groups are made up of contrasting spaces – between and within individual islands. Islands can be isolated and connected, local and global, as well as traditional and innovative. Visitors to the islands may be there intentionally (tourists or pilgrims) or unintentionally (exiles or castaways). Some islands had sustained connections (trade), others temporary (exiles), and some only had indirect associations (through other islands) with Rome and the wider empire. Although islands are often mistakenly seen as isolated (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman, Alcock, Egri and Frakes2016), it is frequently the case that they are the first to experience change, either positive (new trends) or negative (impact of war). For example, the Cyclades were the first places in the geographical region of the modern Greek state to be Christianized (Sweetman et al., Reference Sweetman, Devlin, Piree Iliou, Angliker and Tully2018). Fundamental to this discussion is the fluidity of connections. Island relationships were significantly more complex than a simply linear connection between each individual island and Rome. There were direct and indirect correlations between islands that, at various times, might include Rome and/or other parts of the empire.

Some of the reasons the islands were so successful in the Roman period must be to do with the fact that at least a few of them, particularly Melos and Paros, were particularly responsive to becoming part of the globalized Roman Empire, resulting in positive phase transition for surrounding or even connected islands. When taken together, studies of religion, economy and people provide a clear indicator that the islands were directly connected with the east in a range of ways, but linksto the west were less obvious. Contrary to the view of seclusion in the Roman Empire, globalization gave those islands with the resources and aspirations to benefit from being part of the Empire through access to Mediterranean-wide networks and imperial investment.

Application of globalization studies helps to support a much more nuanced view, in which some places actively wanted to be part of the wider networks facilitated by the empire and, as a result of their participation, changes (positive and negative) are perceptible; others may have chosen to remain on a similar level of participation (or not) and therefore incurred little transformation in their daily lives. This holds true not just for differences between islands but for individual communities on the islands themselves. To highlight this point, as much data as exists on individuals, through epigraphic and mortuary data, and drawing on studies of social mobility, will be included in the overall study. This enables questions about settlement patterns and populations to be answered, such as whether there are perceptible changes on becoming part of the Roman Empire or following the conversion to Christianity. Evidence for change like this might be seen in fluctuating settlement patterns or mortuary practices and in religious topography and practice.

1.4.4 Christianization

Studies of the islands in the Roman period often begin with discussions of the Cyclades in the Hellenistic period, but they rarely reach beyond the fourth century ce. Although in recent years more attention has been paid to the Cyclades in the Roman period, the Late Antique period is still largely unexplored. Theoretically, one of the most impactful changes in the Cyclades would have been the adoption of Christianity as state religion. Preliminary work already suggests that this is not actually the case, and that there are significant degrees of continuity of everyday life and even cult. Christian populations are visible in the archaeological record from the second century ce, but it is not until the late fourth century that Christianization efforts begin to be seen monumentally, in the form of churches. Christian churches were constructed for a range of reasons by different protagonists, from local populations to imperial Constantinopolitans, and the earliest examples are found in well-networked areas through complexity processes (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman2015a).

Christians actively sought to convert others; there is a dynamic sense of purpose to conversion, and the term Christianization refers to both the means and consequence of this conversion. While the results are often discussed in contemporary scholarship, theorizing the practical process still lags behind. The consequence of this has been that although a great deal has been done to counter traditional views of the negative elements of conversion, such as destruction of temples, and even highlight the more positive aspects, such as a peaceful transition, it is not always possible to see why it was so successful. Analysis of the archaeological data will enable key questions concerning the fourth century to be addressed, such as how and why the islands were among the earliest places to be Christianized and whether all islands were similarly precocious. Evidence of the pottery and architecture will help to shed light on the various conduits for the agents of transition. In terms of economy, the islands appear to have flourished in the Late Antique period (in spite of earlier narratives suggesting otherwise). The reasons for this will be explored in the final chapter, based on the evidence of the archaeological data in the context of wider change, such as the foundation of Constantinople as the new capital.

As with globalization and network analysis, Christianization theories enable a means of approaching the archaeology of the Cyclades with a different perspective to the norm, including: evidence of contemporaneous practices of polytheistic cult and Christianity; perceptions of the islands as early in the adoption of Christianity; and insights into active decision-making processes on the part of local communities and Christian officials.

1.5 Discussion Chapters

Drawing on the evidence presented in Appendix 1, the first discussion chapter (Chapter 2) focuses on the topographic and environmental context. Settlement patterns are assessed based on the available data, of which survey evidence is the most coherent. However, a combination of research and rescue excavation data (primarily in urban spaces) can also afford an understanding of the city through analysis of the topography of burials, settlement and industrial spaces. This is a fundamental requirement to understanding the potential change in settlements (if any) between the Hellenistic and Roman and Late Antique periods. An examination of settlement patterns and mortuary practices provides an understanding of people at a fundamental level: how they interacted with each other and the landscape; and how this may have developed over time. As environment was a reasonable constant (at this time), the diachronic view of the archaeology in this context can signal events that may otherwise not be so obvious when top-down approaches are taken.

Chapter 3 draws on the synthesis of the settlement and mortuary data to highlight the economic success and resilience of many of the islands by looking at the resources and trade on the islands. Portable material culture is the key focus along with epigraphic data enabling an understanding of the islands’ exploitation of resources as well as emphasizing their exports and imports. As will be shown, the profile of the islands’ imports is reasonably generic in both Roman and Late Antique periods following a common repertoire of imports in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, application of network analysis to this material, enables both micro and macro views to highlight the islands’ changing rather than declining economy. This is particularly salient in relation to the Delian collapse; when a hub collapses, the network reforms into smaller networks and this is what can be seen in the Cyclades. The micro view highlights long-term changes on an island while the macro view shows that islands follow different patterns of different economic cycles to each other and when some islands prosper it can be seen that it is sometimes as a result of change in others (indicative of resilience) or because of participation in the globalized empire.

Building on the evidence of economic networks, in Chapter 4, a study of religious networks enables a wider view of the islands’ communication links over time. The (largely) epigraphic evidence for visitors to Cycladic sanctuaries is indicative of a wide range of connections from across the Aegean that are not necessarily driven by economic or resource requirements. They tend to be personal connections and of varying intensity and longevity. Not all the Cyclades have the same connections; some such as Paros and Melos have connections with Samothrace through the cult of the Theoi Megaloi. It is telling that for many of the islands that their religious places do not change significantly on becoming part of the Roman Empire. The majority of sanctuaries continue in use from the Hellenistic period, sometimes with the addition of cults such the imperial cult. Becoming part of the globalized empire may have helped grow the numbers and profile of the visitors to the islands and this is seen in the epigraphic data. Many of the Cycladic temples are perched in highly visible locations, emphasizing, in particular, visibility from the sea. In some cases, temples are focal points around which land extent is defined and controlled, for example, the Temple of Demeter at Naxos (Figure A.22). As the Cyclades saw the emergence of some of the earliest significant Christian populations and churches in the Greek East, the extent to which there was continuity of the importance of place sheds light on the nature of the Christianization process; which of the islands embraced Christianity promptly and how this relates to their network connections (both religious and economic). While the domestic evidence for the islands in the Late Antique period is not extensive, the topography of the churches should provide enough evidence to enable a reasonable understanding of settlement patterns during this period.

Chapter 5 examines the evidence, primarily epigraphic, for individuals on the islands and the networks they created and how they changed over time. For example, individuals and families created connections within Cycladic islands such as the Babullii and between the islands and Asia Minor such as the Cossutii or between individual islands such as Thera and Ephesus such as the Frontonianus and Kleitosthenes families. This helps to bring the economic and religious ideas to life. In doing so, this highlights the administrative, political and social aspects of life on the Cyclades and demonstrates areas of variation in these aspects. Looking at individuals in this way enables the macro and micro view of the islands, which can be sometimes eclipsed in such a wide study. As such, social mobility, particularly of women, is visible on the islands, arguably more so than in other areas which is indicative of the resilience of the Cyclades.

After the context has been examined in detail, the application of network analysis will deliver an enhanced understanding of how the supposedly isolated archipelago actively participated in the wider Roman Empire, using theories of globalization, and how it became one of the most advanced areas in terms of the processes of Christianization. This work will go beyond showing that the islands were not backwaters; through an examination of their connectedness, it will show that the islands displayed economic efflorescence throughout the Roman era and into the Late Antique period, when other regions of the Aegean were showing signs of abatement, and precocious Christianization, well in advance of Crete and mainland Greece.

1.5.1 Sources

The earliest mention of the archipelago’s name ‘Cyclades’ belongs in the fifth century bce (Thucydides and Herodotus). Various writers, from Pseudo Scylax to Strabo, include various islands as part of the Cycladic archipelago.

Off Attike are the islands called Cyclades, with the following cities in the islands: Keos – this one is four-citied (Poieessa, a city) with a harbor; Koressia, Ioulis, and Karthaia Helene; Kythnos island, with a city; Seriphos island, with a city and a harbor; Siphnos; Paros with two harbors, one closed; Naxos; Delos; Rhene; Syros; Mykonos.

Now at first the Cyclades are said to have been only twelve in number, but later several others were added.

Strabo (Geography 10.5) also divides the modern Cyclades between the Sporades and the Cyclades. He included Keos, Kythnos, Seriphos, Melos, Siphnos, Kimolos, Delos, Paros, Naxos, Syros, Mykonos, Tenos, Andros and, of course, Delos as the Cyclades, with Thera, Ios, Sikinos, Folegandros, Amorgos and Anaphe as part of the Sporades.

Near it are both Anaphê and Therasia. One hundred stadia distant from the latter is the little island Ios, where, according to some writers, the poet Homer was buried. From Ios towards the west one comes of Sicinos and Lagusa and Pholegandros, which last Aratus calls ‘Iron’ Island, because of its ruggedness. Near these is Cimolos, whence comes the Cimolian earth. From Cimolos Siphnos is visible, in reference to which island, because of its worthlessness, people say ‘Siphnian knuckle-bone.’ And still nearer both to Cimolos and to Crete is Melos, which is more notable than these and is seven hundred stadia from the Hermionic promontory, the Scyllaeum, and almost the same distance from the Dictynnaeum. The Athenians once sent an expedition to Melos and slaughtered most of the inhabitants from youth upwards. Now these islands are indeed in the Cretan Sea, but Delos itself and the Cyclades in its neighbourhood and the Sporades which lie close to these, to which belong the aforesaid islands in the neighbourhood of Crete, are rather in the Aegean Sea.

Strabo provides quite extensive detail of some of the islands; for example, he mentions the temple of Aegletan Apollo at Anaphe, the poverty of Gyaros, the poets such as Simonides from Keos and Archilous from Paros and the prevalence of baldness on Mykonos (Geography 10.5).

Tenos has no large city, but it has the temple of Poseidon, a great temple in a sacred precinct outside the city, a spectacle worth seeing. In it have been built great banquet halls – an indication of the multitude of neighbors who congregate there and take part with the inhabitants of Tenos in celebrating the Poseidonian festival.

In addition to a brief ‘history’ of the creation of the islands (NH 2.89), Pliny outlines what islands were included in the Cyclades (NH 4.22) and some of the Cycladic islands that he includes as part of the Sporades (NH 4.23) (Schinousa, Folegandros, Ios, Gyaros, Donousa, Sikinos, Kimolos, Melos, Amorgos, Thera and Therasia). While mentioning some of the islands as places used by the Romans for exiles, Pliny also recounted some of the more fanciful elements, such as Mucianus’ description of the spring at the Sanctuary of Dionysus at Paliopolis running with water that had the flavour of wine during January (NH 2.106).

Keos, Sikinos, Siphnos, Seriphos, Rhenea, Paros, Mykonos, Syros, Tenos, Naxos, Delos, and Andros are called the Cyclades, because they lie in a circle.

The Cyclades are nine islands – namely, Andros, Mykonos, Delos, Tenos, Naxos, Seriphos, Gyarus, Paros, Rhenia.

Throughout all the discussions of the islands, only Mykonos, Naxos, Paros and Seriphos are consistently mentioned as being part of the Cyclades. Just as there is confusion about what islands belong to the Cyclades, simply snapshots of political and economic life on the islands are attainable from the occasional references in historical texts and epigraphic sources. Writers such as Cicero described some of the islands from a visitor’s perspective in his letters to Atticus (Cic., Att. V. 12). Catallus mentions the islands in Carmina 4 and some argue that this poem, while being allegorical, also describes an actual journey he made back from Bithynia (Griffith, Reference Griffith1983).Footnote 5 Ovid refers to the Cyclades in his Metamorphoses, mixing myth and description together; for example, in Book 7, he describes campaigns in the Aegean that King Minos may have undertaken. He includes many of the individual islands, but in random order, highlighting the mythical nature of the poem. Ovid also mentions the variability of the winds between the islands in Epistle 21, 64–84.

References to the islands by other writers overwhelmingly relate to exile, piracy and being trapped there by bad weather. For example, Juvenal likened imprisonment to being between Seriphos and Gyaros, and described Gyaros as a vile place. Tacitus regularly mentions the names of those exiled to the islands, including Vibius Serenus on Amorgos (S1) (Ann IV. 13.2), Vistilia and Cassius Severus on Seriphos (S23) (Ann II, 85 and Ann IV, 21), and Publius Glitius Gallus on Andros (S3) (Ann XV, 71). Cicero and Plutarch discuss the problems of piracy in the Cyclades, with particular reference to the destruction of Delos by the pirates of Athenodorus, allies of Mithridates in 69 bce (Cicero, Leg. Man 55). Plutarch also refers to more general disturbances with reference to the reasons for Pompey’s aims to rid the Aegean of pirates (Plutarch, Pomp. 24). Strabo (Geography 7.7.5) and Appian also noted increasing issues with pirates (de Souza, Reference de Souza2002, 164) and there is plenty of epigraphic evidence for piracy too. The Roman banker L. Aufidius Bassus forgave the Tenians interest on loans in the first century bce as they were constantly under attack from pirates (IG XII 5,860) (TEN 5 & 6) as was Siphnos (IG XII 5, 653). Most of this data pertains to the first century bce, and it may be the case that the problems were diluted later. However, the trope for the Cyclades as desolate, pirate-infested places for exiles persisted. For example: ‘This year has been to me like steering through the Cyclades in a storm without a rudder; I hope to have a less dangerous and more open sea the next…’ Thomas Sheridan to his friend Dean Jonathan Swift (1735–6) (Swift, Reference Swift1768, 153).

1.6 Short History of the Islands

During the so-called Dark Ages, which impacted on much of the Greek mainland (marked by loss of writing and permanent settlement), sites such as Xobourgo on Tenos (S27) (Kourou, Reference Kourou, Karageorghis and Morris2001) and Zagora on Andros (S3) show prolonged domestic occupation and cult practice (Cambitoglou et al., Reference Cambitoglou, Coulton, Birmingham and Green1971), which continues into the Geometric period, likely to be in part due to island resilience. In many respects, the islands are remarkable for their settlements at a time when, in other parts of Greece, permanent habitation seems to have been in decline. This period of buoyancy in the Cyclades continued into the Archaic period (eighth–sixth century bce) when the islands were at the forefront of innovations, particularly in art and coinage, which can be seen in the foundation of their colonies, for example, the Theran colony at Cyrene and the Parian colony at Thasos. During the fifth century, the islands were pivotal in Athenian power struggles and by the Hellenistic period their economic and trade skills were reinvigorated, with Delos at the centre.

Episodes of decline are commonly purported after periods of prosperity; there is a similar bias in interpretation for the fourth century as there is with the supposed challenges of the Roman period, which followed the prosperity of the Hellenistic. However, the assumed fourth-century decline has been challenged recently by Constantakopoulou (Reference Constantakopoulou2007), Rutishauser (Reference Rutishauser2012) and Tully (Reference Tully2013). Constantakopoulou (Reference Constantakopoulou2007) suggests that the Cyclades were doing so well in terms of agricultural production in the fourth century that this may have been its peak period. Rutishauser argues that the second half of the fourth century saw an important period of temple building on the islands, which is often underrated by the focus on the Archaic period. The sense of vitality at the end of the fourth century is reflected in the resurgence of local mints (Tully, Reference Tully2013). This is clearly indicative of a level of resilience that is arguably seen in the Roman period but has been obscured by preconceived expectations of what the islands should be like during this time. By the Late Antique period, little is known about the islands and they are frequently dismissed as desolate places – abandoned and degraded as a result of attacks by pirates, Slavs and Arabs.

These fluctuating times are reflected in the way in which poets and writers wrote about the islands. In the midst of the highs of the Hellenistic period, Callimachus wrote: ‘Surely all the Cyclades most holy of the isles that lie in the sea, are goodly theme of song’ (Callimachus, Hymn to Delos, 1). However, after the Mithridatic and Civil Wars, Seneca, in the mid first century ce, wrote: ‘So there are only mountain tops that appear like islands above the water, and increase the number of the scattered Cyclades … all was sea; to the sea there was no shore’ (Seneca, Natural Questions 3.27).

The islands of the Cyclades were ruled by different powers in the Hellenistic period and in spite of (or perhaps because of) the vibrant economy, numerous watchtowers constructed on the islands, such as those on Seriphos (S23), Siphnos (S25), Andros (S3) and Amorgos (S1), reflect somewhat unsettled times. The Macedonians held Siphnos, Seriphos, Ios, Paros, Tenos, Syros, Melos, Amorgos and Naxos. They lost Naxos and Amorgos to the Ptolemies in the third century, and Siphnos and Paros to Rome in 146 and 100 bce, respectively. Keos and Thera were both under Ptolemaic rule and Andros was part of the Attalid kingdom. Andros was taken by the combined powers of Attalos I and Rome in 199 bce and, according to Livy (31.45), the city was destroyed and the population required to leave for Boeotia (Grabowski, Reference Grabowski2016, 93). However, the Attalids convinced the population to return, highlighting the importance placed on Andros as a pivotal point between Asia Minor and Euboea (Grabowski, Reference Grabowski2016, 92). Evidence of the continued connections is seen in the dedications to the Attalid kings and the cult of Eumenes II on the island (Grabowski, Reference Grabowski2016, 93). Furthermore, Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa (Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa2018a, 72) suggests that some of the Stoas at Palaiopolis (S3) reflect the Pergamian connection. The involvement the Ptolemies had with the islands are expressed in the numerous cults to Egyptian gods (Thera) (S28), Isis (Delos) (S5), Arsinoe Philadelphos (Minoa and Arkesine, Amorgos (S1)), Isis (Aigiale, Amorgos), Serapis (Arkesine, Amorgos) and Serapis, Isis and Anubis (Minoa) (S1) (Marangou, Reference Marangou, Jentel and Deschênes-Wagner1994, 373).

In the early second century, many of the Cyclades are believed to have been governed by Rhodes; however, Tully (Reference Tully2013, 565–9) suggests that rather than a single hegemony, the various Hellenistic powers continue to be involved in different islands at a variety of times. After the Battle of Pydna (168 bce) and the fall of the Macedonians, Athens was put in charge of Delos (167 bce). The Roman colony was established, with clear epigraphic evidence, for Italian merchants. In 166 bce, the port was made free (in part, to take away power from Rhodes). In terms of their administration, to reward them for their support after the First Mithridatic War, Sulla gave some of the islands to Rhodes. During the Hellenistic period, the islands were controlled by different powers: the Attalids had Andros; the Macedonians had Siphnos, Seriphos, Ios, Paros, Tenos, Syros, Melos, Amorgos and Naxos; the Ptolemies controlled Amorgos and Naxos after Macedonia, as well as Keos and Thera. Although Marcus Antonius gave many of the islands to Rhodes, this was reversed under Augustus, when many of the islands became part of Achaea – although some, at least, stayed with Asia. In the first century bce, with the exception of Delos and Keos, most of the islands were part of the province of Asia.

The Cycladic islands flourished during the Hellenistic period in spite of the changing rulers. Naxos and Paros thrived due to their natural resources (Rustishauer, Reference Rutishauser2012, 5–7). Delos (Figure A.7), as an emporium, was a hub in the economic network of the Eastern Mediterranean, and nearby islands such as Andros and Tenos profited as a result of phase transition from Delos. The hub at Delos meant that there was a regular flow of commercial and religious traffic around the Cyclades (Rutishauser, Reference Rutishauser2012, 5). In turn, this created jobs and financial opportunities, attracted an international community to reside on the islands and enabled access to products that might otherwise have been unreachable. External powers and individuals were attracted to the islands because of the potential of the trade and religious networks running through them. Furthermore, the extensive pilgrimage traffic encouraged sanctuaries to be constructed on both marine and inland routes (Rustishauer, Reference Rutishauser2012).

Studies of numismatics (Sheedy, Reference Sheedy, Drougou, Evgenidou and Kritzas2010; Tully, Reference Tully2013) and architecture (Lodwick, Reference Lodwick1996) indicate an independence of production that was unrelated to the islands’ numerous rulers during the Hellenistic period. Each island had its own polis; indeed, Keos had four poleis and Amorgos had three. Types of settlements on the islands included urban, rural and periurban. The settlements were dynamic and evolving, as demonstrated by the synoecism of the cities on Keos and the abandonment of Minoa in favour of Katapola on Amorgos (S1). The Cycladic cities had their own boule and demos (evidence from inscriptions) and on some islands such as Thera, the bouleterion or the agoranomion have been located (S28) (Gaitanou, Reference Gaitanou, Bonnin and Le Quéré2014, 203).Footnote 6 Tully (Reference Tully2013) notes that too often the islands have been seen from the perspective of the major powers, like Athens and Rhodes, that controlled them in the Hellenistic period. This has masked the evidence for individual island identity in the same way that the idea of the Roman Empire has in the later period.

The first century bce was a tumultuous time, with the Mithridatic Wars and escalating piracy. The islands were hit by a series of crises and the archipelago became the inadvertent setting of a series of attacks and retributions, such as the Mithridatic and then Rome’s Civil Wars (Tselekas and Papageorgiadou-Banis, Reference Tselekas, Papageorgiadou-Banis, Papageorgiadou-Banis and Giannikouri2008, 165–7). Individual islands supported different sides, and some suffered the consequences; for example, Delos supported Rome and was destroyed by Mithridates (Tully, Reference Tully2013); it was later attacked by pirates (de Souza, Reference de Souza2002, 58).

During this time, the islands changed administrative hands frequently. To reward the island for its support of Rome, after the First Mithridatic War, Sulla gave Rhodes its freedom in addition to land in the form of some of the Aegean islands (Pawlak, Reference Pawlak2016, 189–90). Later, it is more certain that Marcus Antonius gave Andros, Tenos and Naxos to Rhodes, to offset the brutal impact of their stand against Cassius (Pawlak, Reference Pawlak2016, 198–200). It is likely that Octavian freed the islands from Rhodes under the pretext that it was a harsh master (Pawlak, Reference Pawlak2016, 197). At this time, Athens had control of Keos and Delos and retained this until at least until the time of Septimius Severus. Although it is known that Augustus reformed the administrative structure of the islands with the creation of the new provinces, it is not always clear whether they belonged to the province of Asia or Achaea (Nigdelis, Reference Nigdelis1990, 220; Le Quéré 2015, 53–8).

It is notable that that Claudius made Achaea and Macedonia senatorial provinces (having been imperial provinces) in 44 ce and then in 66 the province of Achaea was made free, meaning that it was immune from tribute (although this was later revoked by Vespasian). Consequently, for a short period, some of the Cycladic islands were not liable for tax. Before that, the cities seem to have been taxed with little escape. For example, in 29 bce, Gyaros sent an ambassador to Octavian to have its tax of 150 drachmas reduced (Mendoni and Zoumbaki, Reference Mendoni and Zoumbaki2008, 31).

The unsettled political designation of the islands continued during the Roman period. In the second century, according to Ptolemy, many of the Cyclades were part of Achaea (Thera, Keos, Ios, Poliagos, Therasia, Delos, Kythnos, Rhenia and Mykonos (Ptolemy, Geographia III.15.26–29)). Andros, Tenos, Syros, Naxos, Paros, Siphnos, Seriphos, Folegandros and Sikinos are grouped under the Cyclades with two subgroups (Ptolemy, Geographia III.15.30, 32). Seriphos, Folegandros and Sikinos are noted separately under the heading Mesiogion and the rest are termed Kalomenos. Even more distinct are Kimolos and Melos, which, as ‘islands near Crete’, are included in a separate chapter (Ptolemy, Geographia III.17.11). Amorgos appears in a separate book with Asia (Ptolemy, Geographia IV.2.33). While it could be argued that these divisions are simply geographical, Poliagos is noted as being deserted and is included with the Achaean islands. It is unclear why it was not grouped with its direct neighbours, Melos and Kimolos. Scholars have different views based on a variety of evidence. Accame (Reference Accame1946, 241) and Le Quéré (2015, 49–70) believed that some of the islands were included with Achaea, that others were free and that Delos and Keos belonged to Athens. Amorgos is likely to have been part of the province of Asia (Ptolemy, V.2, 31) and Aigiale had communities from Miletus living there (Liampi, Reference Liampi2004). The island remained part of Asia until it became part of the provincia insularum. Based on Ptolemy’s Geographia and the Cosmographia, Mommsen considered the Cyclades to be part of Achaea.Footnote 7 Étienne argued that the honorific inscriptions to Asian proconsuls (P. Vinicius and L. Calprurnius) on Andros and Delos indicated direct connections with Asia (Étienne, Reference Étienne, Braun and Queyrel1990, 150–56; Pawlak, Reference Pawlak2016, 200). When asked to attest the right of asylia, according to Tacitus, the Tenians’ petition to Tiberius was heard with a group of Asian cities (Tacitus, The Annals 3.63). Although this has persuaded Étienne of the Asian provincial designation, the evidence is ambiguous. The island had clear connections to Achaea and Asia at different times, but current evidence is principally of Cycladic origin. Neither from the Asian nor Achaean perspective is there significant evidence to indicate an administrative relationship with the Cyclades. It is not particularly unusual to have a one-way relationship; for example, Chevrollier (Reference Chevrollier, Francis and Kouremenos2016, 11–26) noted the limited data for different types of connections between the two parts of the joint province of Crete and Cyrenaica. Epigraphic evidence for officials travelling from Cyrenaica to Crete, particularly in the first century ce, is in contrast to the paltry evidence for Cretans in Cyrenaica. In terms of economic connections, Cretan lamps were exported to Cyrenaica, but there is little evidence of Cyrenaican material exported to Crete. In other aspects, such as religion, there is little evidence for areas of shared practices or traditions. Ironically, in spite of the negative views of imperialism in modern scholarship (Le Quéré, 2015, 19–20), as part of the Roman Empire, for the first time in history, the islands were united under one leadership. The administration of the islands was of concern to Rome and it took some time before the province of the islands could be established. For example, Marcus Aurelius sent two imperial legates, C. Vettius Sabinianus Iulius Hospes and L. Saevinius Proculus (later to become governor of Crete and Cyrene), in 164 and 166, respectively, to the Cyclades to assess the administration of the islands by Asia Minor (Buraselis, Reference Buraselis2000, 144–5).

In the fourth century, Sextus Rufus in the Breviarium (Ita Rhodus et insulae primum libere agebant, postea in consuetudinem parendi Romanis clementer prouocationibus peruenerunt et sub Vespasiano principe Insularum provincia facta est) made the only surviving reference to Vespasian combining the islands into a single province in the late first century. Pawlak (Reference Pawlak2016, 201) rightly notes the problems associated with this, given that it is the only reference to the islands forming a single province until Diocletian created the province of the islands later in the third century. At this point, Rhodes is in both political and ecclesiastical control of the praeses insularum. This was with the exception of Keos, Kythnos, Seriphos, Syros, Delos and Mykonos (Nigdelis, Reference Nigdelis1990, 223), which were under control of the eparchy of Achaia led by Corinth. This lasted until 536, when Justinian created a new political organization, the quaesture exercitus, which included all of the islands. The shared administration did not necessarily create bonds or collective identities between the islands but there were naturally commonalities, which will be explored here in addition to the nature of the islands’ external relations.

Between the fourth and the seventh centuries, the Cyclades are barely mentioned in the sources. This may be due to a number of reasons, including a lack of interest on the part of bigger players, a loss of written sources or perhaps the islands were so quiet that they were not worth writing about (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000, 14–17). The dearth of sources and lack of scholarly attention in the past has led to generalizations about the decline and abandonment of the Cyclades after the Gothic raids in 268 ce (Kulikowski, Reference Kulikowski2007, 19–20). However, as presented here, the archaeological and epigraphic data clearly show an expansion in terms of both economy and culture with evidence from the inscriptions at Grammata on Syros (S26) (Figure A.40) of a wide trade network and increased amphorae production on Naxos and Paros (Chapter 3). Contrary to the traditional beliefs of a rather violent imposition of Christianity on the local population, recent studies have shown a much more organic and peaceful Christianization. In fact, recent analysis of the material suggests that the Cyclades were Christianized much earlier than other locations, such as Crete and the Peloponnese, and this will be discussed in Chapter 4. It is known that Paros, Siphnos and Amorgos were Episcopacies. A variety of graves and monuments prove that Christianity became known on the islands during the second century ce. After the Gothic raids of the third century, quietness prevailed in the wider region until the end of the seventh century, when the Slavs attacked Greece from the north, reaching the Cyclades in 675 ce and apparently destroying Paros.

Throughout these unsettled times, each island retained its independence with its own polis, demos and boule (Nigdelis, Reference Nigdelis1990). Nigdelis (Reference Nigdelis1990) suggested a continuation of life on the islands throughout the late Hellenistic and imperial periods, with the most significant changes happening in the late second and early third centuries, when women and children begin holding some offices and certain posts become inherited, not elected, positions. He believed that this reflected a move by the elite to places such as Ephesus for more economic potential (Nigdelis, Reference Nigdelis1990, 416). However, it will be argued here that an examination of more data counters this suggestion of change.

As in other areas, the local governments were Greek and self-governing. While the idea of the democratic constitution continued, Roman rule introduced new elements (in tandem with the old). Although magistrates were present, it is unlikely that they could propose measures. Nigdelis (Reference Nigdelis1990) has shown that the local existing offices, such as basileous and nomografoi, continued throughout the Roman period and that any new offices were specifically established to deal with new tasks, such as the imperial cult or the office of the dekaprotoi. A wide range of officials are known from the epigraphic data, especially tax collectors and religious officials (discussed in Chapter 5). The names of the majority of high priests show that they were Roman citizens (with the exception of an example, Theoteles son of Theoteles from Keos (Zoumbaki and Mendoni Reference Zoumbaki, Mendoni, Mendoni and Mazarakis Ainian1998, 670)).Footnote 8 Both property and land tax seem to have been assessed together, which meant that only one tax collector was required, and the assessment was supervised by Roman officials (Nigdelis, Reference Nigdelis1990, 455). Many of the new laws and offices concerned new administration and religious needs. Other new offices such as the logistis created a sense of hierarchy within the administrative and political structure. This gave people, usually elites, more opportunity for social mobility (discussed in Chapter 5). In the Late Antique period, small numbers of inscriptions mention military or administrative personnel and it is unlikely that the majority of officials were resident long-term on the islands (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000, 24). A kentarchos and an archon from Bithynia (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000, 24) passed through Syros. But some few residents are known, such as an actuarius from Amorgos (S1) and a land-holder from Thera (S28) (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000, 24). More titles are known from the church sphere, including bishops, priests and deaconesses.

As Šašel Kos (Reference Šašel Kos1977) noted, Latin inscriptions appear in greater quantities in the earlier imperial period than later. However, Šašel Kos (Reference Šašel Kos1977, 205) also remarked that Latin inscriptions appear in greater quantities on the islands than would be expected. Even if Latin inscriptions are not found as often after the first century, Latin names are still regularly found throughout the islands, for example, Marcus Aurelius Capito’s funerary inscription dating from the third century (MEL 5). In the Late Antique period, Greek, including local dialects, continues in the majority (Kiourtzian, Reference Kiourtzian2000, 24).

1.7 Conclusions