When the embassy of Greeks visits Achilles in Book 9 of the Iliad, they find him with Patroclus singing heroic song (9.186–9):

The passage certainly invites metapoetic reflection on a hero singing of heroes in a song about heroes.Footnote 2 And while it is surprising to encounter a leader of the Greeks singing at all, the final line contains, at least according to some definitions, an abnormality on a more formal level, namely, a break in the metrical phenomenon known as Hermann’s Bridge.Footnote 3 In 1805, Gottfried Hermann noted that Greek hexameter avoids placing a caesura between the two shorts of the fourth foot.Footnote 4 The narrator’s description of Achilles in line 9.189 appears to do just that, with a word break after the short ultima of ἄειδε and before the elided δ᾽ (< δέ ‘and’, ‘but’) and initial short syllable of ἄρα: ἄειδε || δ’ ἄρα κλέα ἀνδρῶν.Footnote 5 Is this anomalous caesura characteristic of Achilles? Or of other speakers, texts or authors? What are the consequences of irregular caesurae on the style and meaning of Greek epic?

This article argues that metrical patterns such as Hermann’s Bridge and their disruption provide valuable stylistic information about speakers, texts, authors and eras in ways that may amplify stylistic effects. Form, expectancy and meaning are intertwined in Homeric verse, but scholars have not yet been able to explore the ways in which patterns of expectancy gleaned from systematic study of the hexameter corpus might relate, amplify or produce cross-effects in the reading of a text. This article makes the case for reading metrical patterns and their disruption by offering the first stylometric survey of breaks in Hermann’s Bridge in the epic corpus. Paying more attention to how and where metrical anomalies concentrate in authors, texts or speakers not only illuminates epic style but also offers new possibilities for the interpretation of hexameter poetry more widely.

The goal of this article is to provide a stylistic methodology applicable to the variety of definitions for Hermann’s Bridge that have arisen since the early nineteenth century. Not every occurrence of a caesura between the two shorts of the fourth foot has counted as a break in the bridge. In the more than two centuries since Hermann’s observation, scholars have prescribed various criteria to decide which caesurae should be considered breaks.Footnote 6 Hermann identified three specifications that make the caesura more ‘tolerable’ (‘tolerabiliorem’, page 693) and thus exclude potential candidates: 1) an additional caesura after the first syllable of the fifth foot (for example, χαλκέου ἐκ τελαμῶνος· ὃ δ’ ὥς τε || νόημ’ || ἐποτᾶτο, Hes. [Sc.] 222); 2) non-amphibrachic words following the caesura (for example, the iamb in θρέψα τε καὶ ἀτίτηλα καὶ ἀνδρὶ || πόρον παράκοιτιν, Il. 24.60); and 3) monosyllables before the caesura (ὦ Κίρκη, τίς γάρ κεν ἀνήρ, ὃς || ἐναίσιμος εἴη, Od. 10.383). Hoekstra excludes all examples with monosyllables (for example, οἶος ἀπὸ προτέρων, Νότιον δέ || ἑ κικλήσκουσιν, Aratus Phaen. 388) and following elision (for example, πρωτίστην· λύσαιμι δ’, ἄναξ, ἐπ’ || ἀπήμονι μοίρῃ Ap. Rhod. Argon. 1.422).Footnote 7 West specifies that prepositives before the caesura (for example, πόντῳ ἐνεστήρικται· ὁ δ’ ἀμφί || ἑ πουλὺς ἑλίσσων, Callim. Hymn 4.13) and postpositives after the caesura (for example, Δήλῳ ἐν ἀμφιρύτῃ; ἑκάτερθε || δὲ κῦμα κελαινόν, Hom. Hymn 3.27) preclude a break;Footnote 8 Solomon adds that a final word of five syllables alleviates the breach (for example, … μετὰ πέντε || κασιγνήτῃσιν, Il. 10.317), presumably because the break is unavoidable if the word begins with a short syllable.Footnote 9 Most recently, Schein allows, with caution, monosyllabic enclitics that precede the caesura and follow a polysyllabic word (for example, μιμνάζειν παρὰ νηυσὶ γέρων περ || ἐὼν πολεμιστής, Il. 10.549 [with enclitic] and μοῦνον τηλύγετον πολλοῖσιν || ἐπὶ κτεάτεσσι, 9.482 [without enclitic]), and Abritta excludes most of the transgressions in the Iliad and Odyssey from the class of real violations for a variety of reasons, some prosodic, others syntactic.Footnote 10

This dispute over definition and lack of comprehensive data have prevented readers from exploring new developments in ways of interpreting potential stylistic, cognitive and interpretative effects of caesura at Hermann’s Bridge. Schein argues that the bridge generates a normative ‘pattern of expectancy’ in audiences that Homer can exploit in order to augment mythological themes and mimetic content within the poetry.Footnote 11 Solomon and Martin have shown that breaks in Hermann’s Bridge provide stylistic features with which poets could characterize speakers, as in the way Odysseus characterizes Thersites’ problematic speech in Il. 2.246–50.Footnote 12 And most recently, Ward has argued that the break in the bridge at Il. 9.394 (Πηλεύς θήν μοι ἔπειτα γυναῖκα || γαμέσσεται αὐτός) lays bare ‘Achilles’ attempt to rupture the normative tendencies of the Homeric hexameter’ in a way that ‘mirrors his attempt to break out of the organizing systems of the Homeric world itself’.Footnote 13 But we lack, as Martin has pointed out, ‘reliable statistics of the entire hexameter corpus, keyed to (any) definition’.Footnote 14 What we need are complete data and stylistic categories that allow readers to group and contextualize breaks, whatever the definition, and consider them more closely.

This article provides data and comprehensive stylistic analysis of breaks in Hermann’s Bridge within the epic corpus from Homer to Nonnus. To do so, it compiles a complete database of all caesurae at the Hermann’s Bridge position in a corpus of canonical Archaic, Hellenistic and Imperial Greek hexameter texts.Footnote 15 To generate this data, it uses the program SEDES keyed to Schein’s definition of Hermann’s Bridge.Footnote 16 This definition has been chosen both due to its prominence in recent publications, for example in Schein’s Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics commentary to Iliad 1, as well as for convenience; this article does not make claims as to its validity, whether syntactic or phonological, and researchers can substitute the data at will within the framework provided.Footnote 17 The article presents and analyses the data for their stylistic features and diachronic trends, including larger formulaic constructions that entail breaks and narratological analysis of character speech. The purpose of this article is thus to provide a thorough account of breaks in Hermann’s Bridge according to categories central to epic style (corpus, constructions and narrative) so that future work can better explore how they enrich our reading of epic poetry.

The first task in a comprehensive study of breaks in Hermann’s Bridge is to gather all caesurae after the fourth trochee using transparent means and then classify each instance as a break or not according to a single definition. To accomplish this, this project first isolates instances of caesurae between the two short elements of the fourth foot in the hexameter corpus, automatically, using the program SEDES that identifies the metrical position of words in Greek epic.Footnote 18 It then distinguishes all caesurae that are breaks according to the definition of Schein, that is, caesurae after the first short of the fourth foot that succeed a polysyllabic word or enclitic following a polysyllabic word.Footnote 19 The entire database is available online; the Appendix lists only the breaks.Footnote 20 And as even ‘quasi-breaks’ that do not meet Schein’s criteria can at times provide stylistic information, the article touches on these as well.Footnote 21 By using a documented computational method for producing the data, and by making the entire list of caesurae accessible, this project seeks to make transparent the means by which the information is gathered and to allow scholars to adapt, refine, or use its stylometry for further study. The survey treats the stylometry of breaks in (§1) texts, authors and books or individual poems; (§2) repeated lines and constructions; (§3) character speech; (§4) relation to quasi-breaks; and (§5) concludes with a summary of the findings and directions for subsequent research.

1. TEXTS, AUTHORS, BOOKS

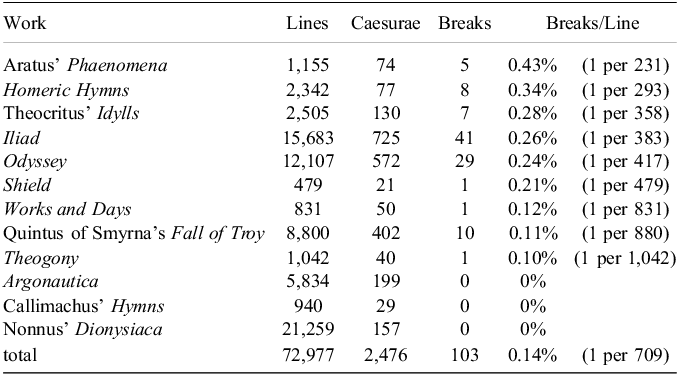

In the corpus, 103 lines break Hermann’s Bridge according to Schein’s definition (see Appendix). For 36 of these, a monosyllabic enclitic precedes the caesura; otherwise, a polysyllabic word precedes the caesura 67 times.Footnote 22 The statistics by text and frequency of breaks per line are found in Table 1 (the ‘Caesurae’ column refers to all caesurae between the two shorts of the fourth foot).

Table 1. Breaks in Hermann’s Bridge by text from highest fraction to lowest

The rate of breaks per line ranges from a low of 0% to a high of 0.43% across works, with a mean of 0.14% across all lines of all works. Homer uses breaks at a consistent rate across the Iliad and the Odyssey in each text, around 0.25% of lines. The rate in the Hymns is slightly higher and the Hesiodic Shield is slightly lower than Homer, whereas Hesiod’s corpus otherwise has fewer breaks. Certain Hellenistic authors, namely Apollonius of Rhodes and Callimachus, never break the bridge, whereas Aratus does more than others (0.43%), and Theocritus about as much as Homer (0.28%). Of the two Imperial hexameter texts, Quintus of Smyrna maintains fewer breaks than Homer but slightly more than the figures of the Theogony and Works and Days. Perhaps most striking is that in all 21,259 lines of his Dionysiaca, Nonnus never breaks the bridge. There is thus a general diachronic trend towards avoidance of the break, but inconsistently so.Footnote 23 Although all Archaic poets break the bridge at some point, some Hellenistic and Imperial poets do, but others do not.

Breaks are not distributed evenly across books or poems. On average, in the Archaic corpus 0.25% of lines break the bridge (1 per 401 lines); in the Hellenistic and Archaic corpus, 0.22% (1 per 461 lines); and in the corpus overall, 0.14% of lines break the bridge (1 per 709 lines). For the corpus, if breaks were randomly distributed, with every line having an independent and identical probability of breaking the bridge, then the number of breaks in a stretch of lines would follow a binomial distribution with p = 0.0014.Footnote 24 As mentioned above, certain works do not break the bridge at all. Under the assumption of independent random distribution, the odds that a number of lines equal to the length of the Dionysiaca would have zero breaks are less than one in a trillion. For the 5,834 lines of the Argonautica, the odds would be approximately one in 3,700. Only in the case of Callimachus’ Hymns is it plausible that the total lack of breaks was the result of chance; as there is one break every 709 lines on average, having none in 940 is not out of the question. The number of breaks in the subdivisions (individual books or hymns) of the remaining works is mostly as would be expected under the random binomial assumption, with a couple of outliers. About half of books (for example, of the Iliad) and individual poems (for example, the Idylls of Theocritus) have no breaks at all, which is not inconsistent with random distribution given the low overall rate of bridge breaks. The two outliers are the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and Odyssey 20, which have an unusually high number of breaks for their length. If breaks were randomly and evenly distributed over lines with p = 0.0025 (that is, the probability of breaks in the Archaic corpus), there would be only a 0.17% chance of a sequence of lines as long as the Homeric Hymn to Demeter having at least as many breaks as it does (6 out of 498). Similarly, Odyssey 20 would yield a 0.33% chance for 5 or more breaks in 394 lines. Apart from these two texts, and the long poems with no breaks, the remaining subdivisions are in the realm where the distribution of breaks is consistent with chance.Footnote 25

This measure of concentration according to probability is only one way to explore the data, but it is helpful in a few respects. It differentiates total occurrences within a poem from distributions within given books or poems often with similar length. On rare occasions, breaks concentrate within certain books or poems, a fact that can be assessed through probability measurements. Likewise, a point in favour of statistical analysis, such as comparison to a binomial distribution, is the fact that the books and poems with the least likelihood under the random distribution assumption are not necessarily those with the lowest rate of breaks: the fragmentary Homeric Hymn to Dionysus has a higher rate (4.67% of breaks per line), but at only 21 lines, its 1 break is more likely to have happened by chance than the 6 breaks of the Hymn to Demeter. The literary significance of breaks within an entire poem or concentrations of breaks in individual books or poems depends on closer inspection within each of their given poetic and narratological contexts, some of which will be explored below in relation to repeated verses, traditional constructions and the narratology of breaks.

2. REPEATED LINES AND CONSTRUCTIONS

Repetitions of whole lines account for some, but not most, of the breaks in Hermann’s Bridge. Thirteen lines both contain breaks and are repeated elsewhere (12.5% of total breaks).Footnote 26 These lines and their respective themes consist of: occlusion of a mortal by divine epiphany (Il. 3.380–1 ≈ 20.443–4);Footnote 27 Achilles’ spear (16.143 = 19.390 [16.141–5 = 19.388–91]); Odysseus shouting (Od. 5.400 = 9.473 = 12.181);Footnote 28 Telemachus rebuking suitors (17.399 = 20.344); rapacity of stormwinds (1.241, 14.371); and damage of a spear (Il. 4.460 = 6.10). The latter line displays notable chiastic structure (ἐν δὲ μετώπῳ πῆξε, πέρησε || δ’ ἄρ’ ὀστέον εἴσω), with a locative preposition and adverb at the beginning (ἐν) and end (εἴσω) enclosing body parts (μετώπῳ, ὀστέον) and the juxtaposed alliterative verbs (πῆξε, πέρησε). The repetitions above notably occur within the same poems; lines that break Hermann’s Bridge do not cross over between the Iliad and Odyssey.

Constructions, however, account for more instances and span texts, authors and time periods. As Bozzone has shown, Greek hexameter poets often composed segments of lines according to phonetic, syntactic and metrical patterns that resemble what linguists call ‘construction grammar’.Footnote 29 The concept of constructions, which stems from studies of language acquisition, is ‘meant to capture the generalizations that language learners draw over their set of data’ to create ‘further expressions’.Footnote 30 Although constructions share certain characteristics with what Parry, Lord and others define as the epic formula, they are less tied to particular words or phrases and instead can encompass syntactic units along with phonemes in particular metrical positions.Footnote 31

Two constructions entail a break in Hermann’s Bridge.Footnote 32 The first is found in the second half of lines such as that which began this article: τῇ ὅ γε θυμὸν ἔτερπεν, ἄειδε || δ’ ἄρα κλέα ἀνδρῶν (‘With this he was delighting his heart and singing indeed the glories of men’, Il. 9.189).Footnote 33 This construction begins after the primary caesura with a verb of three to four syllables that ends with a trochee (– ⏑) (most often having the metrical shape ⏑ – ⏑, but also ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ or – – ⏑); is followed by an elided δέ (δ᾽); the particle ἄρα (most often elided to ἄρ᾽); and a noun phrase (most often as predicate, but sometimes as subject): | [× – ⏑]V4b || δ᾽ ἄρ[–] [⏑ ⏑ – –]Pred.NP.Footnote 34 The construction has a significant degree of flexibility, both in the content of the verb and noun phrases and in the optional elision of ἄρα, but it centres around the verb and δέ with ἄρα, which do not occur in this metrical position in other constructions.Footnote 35 The break in Hermann’s Bridge occurs through the trochaic ending of the initial verb (× – ⏑) and the elision of δέ, which lacks vocalic content in all instances and thus combines with the particle ἄρ(α) (⏑[ –]) and allows it to constitute the break in Hermann’s Bridge. Construction analysis helps identify this regularity better than traditional formulaic analysis of lexical phrases, and it illuminates an important point: just as the repetition of certain lines necessitates repeating a break in Hermann’s Bridge, so too does the repetition of this construction. To use the [verb] δ᾽ ἄρα construction is to also break the bridge.Footnote 36

The second construction with a break in Hermann’s Bridge also centres around two smaller words flanking the break. It consists of two types. The first type begins most often with a two syllable adjective of the shape ⏑ – followed by the enclitic particle περ, participle ἐών usually ‘in agreement with the word on which περ leans back’, an agentive noun at line end, and often a proper noun at line beginning: [⏑ –]ADJ4a περ || ἐών [⏑ ⏑ – –]Agen.N.Footnote 37 Variants of this type substitute different parts of speech, including verbs, in each of the syntactic slots, and at the most extreme they drop the περ while keeping an ἀγορευ- stem.Footnote 38 The other type of this construction declines the participle ἐών into the accusative ἐόντ᾽ and has more syntactic variety in its peripherals: [⏑ –] περ || ἐόντ᾽ [⏑ ⏑ – –].Footnote 39 As seen in some of its variants, the construction at times takes on a formulaic life of its own tied to a word’s stem, especially in its ability to substitute the agentive noun ἀγορητής (‘speaker’ Il. 2.246, 19.82; Od. 20.274) with its verb ἀγορεύεις (‘you speak’ Il. 16.627, Od. 17.381). And as its prevalence shows, it is a productive construction.Footnote 40 Most of all, as with the [verb] δ᾽ ἄρα construction above, this construction too prescribes a break in Hermann’s Bridge.Footnote 41

The usefulness of the [verb] δ᾽ ἄρα and περ ἐών constructions persisted into Hellenistic and Imperial epic. These constructions provided Theocritus and Quintus of Smyrna language that they could adapt and mold to new contexts, all while retaining the break. Theocritus uses the περ ἔων construction (24.102),Footnote 42 with added variation and anaphora (μαίνετο … μαίνοντο, 26.15), similar to the syntactic variation found in Quintus of Smyrna (3.336, 9.393). In a more substantial variation, Quintus adapts the [verb] δ᾽ ἄρα construction by maintaining the first verbal element [⏑ – ⏑]V4b, elided δέ and initial ἀ- of ἄρα, but otherwise replaces the portion after the break:

Similarly, elsewhere Quintus retains the participle ἐόντ᾽ while substituting περ for οὐκέτ᾽, a word that initiates the break at Od. 20.223 (ἐπεὶ οὐκέτ’ || ἀνεκτὰ πέλονται) (Quint. Smyrn. 3.185, 7.40). Moreover, in an unrelated testament to his compositional versatility with breaks in Hermann’s Bridge, Quintus substitutes syntax and semantics in an adaptation of a line from a speech by Antilochus:

This ‘formulaic’ substitution is clever in its antithesis of νεώτερος (‘younger’) with γεραίτερος (‘older’) and is entirely of Quintus’ own making, since νέος + εἰμί does not occur in this sedes elsewhere.Footnote 43 And given the shared context of funeral games in Iliad 23 and Posthomerica 4, here Hermann’s Bridge serves as a site of intertextual creativity.Footnote 44 What these later adaptations of constructions and lines that break Hermann’s Bridge show is that the break in form proved useful and persisted in certain authors at certain times, even when there was opportunity to avoid or amend it.

The constructions above embody an apparent contradiction. They are at once traditional, appearing in different texts and authors with a flexible syntax, as well as abnormal, entailing a metrical anomaly. One might thus suppose that its conventionality makes its metrical break more expected. But a construction’s traditionality does not alienate it from larger patterns of expectancy that arise from repeated exposure to caesurae in epic poetry. Most of the epic poetry audiences heard and poets composed consisted of constructions without breaks. Concerning caesurae, only 103 lines out of 72,977 in the corpus break the bridge. Audiences would have experienced the typical rhythm of the bridge so frequently that they would have plausibly experienced a caesura at the bridge position as rhythmically unexpected despite the traditionality of the constructions themselves. The above constructions have a special status as both being useful in the composition of hexameter and for entailing a transgression in the typical rhythm of caesurae in the line. By focussing on the constructions responsible for certain phrases, including ones that are irregular and metrically anomalous, we can detect unforeseen stylistic consistencies in poetic composition between phrases, lines, passages, authors and eras.

3. NARRATOLOGY

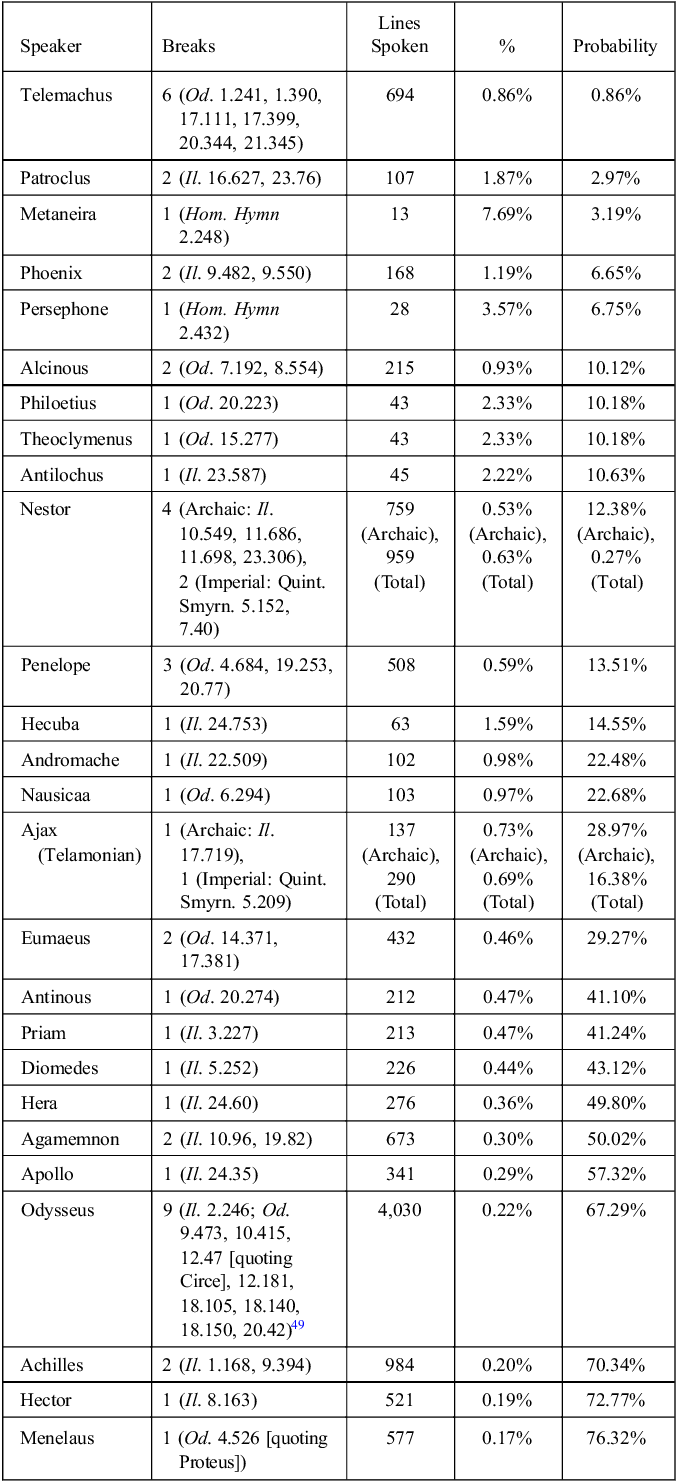

Of the 103 breaks according to Schein’s definition, about half are in character speech and half are in narrator speech; of the caesurae that do not qualify as a break, about 1,000 are in character speech and 1,350 in narrator.Footnote 45 Table 2 provides statistics for speakers in order of probability.Footnote 46

Table 2. Breaks in Hermann’s Bridge in character speech by probability

In the epic corpus, twenty-six speakers break the bridge. Only two instances are in direct speech by a god (Apollo and Persephone), with two more in divine speech quoted by a mortal (Circe by Odysseus, Proteus by Menelaus); the rest are by mortals.Footnote 47 Eight instances are by female speakers, with eighteen by male speakers. Characters break the bridge slightly more than the narrator overall relative to their total amount of speech in most texts. For example, 51.5% of breaks are in character speech, but character speech accounts for only 45% of the Iliad (7,054 lines), and even less so in Quintus of Smyrna’s Fall of Troy (23.6% character speech [2,073 lines]).Footnote 48

As with the density of breaks within individual books, probability disambiguates the number of breaks and the frequency of breaks from the probability of that number of breaks within that number of opportunities. Characters who break the bridge the most, such as Odysseus and Achilles, are not necessarily the least likely to do so. If they speak enough lines, it becomes more probable that they break the bridge, given an overall likelihood of breaking the bridge 1 in 401 lines in the Archaic corpus. What is perhaps more surprising is the extremely low probability of certain characters. Telemachus and Patroclus both break the bridge a different number of times (6 and 2 respectively) within a different number of lines (694 to 107), but they are almost equally unlikely of all characters to break the bridge as often as they do for the number of lines they speak. In 694 lines, we would expect Telemachus to break the bridge only around 1.7 times. He breaks it 6 times. This is why his probability score is 0.86% compared, for example, to his father’s 67.29% (9 in 4,030 lines). Once again, probability helps identify potential stylistic traits that we might not expect otherwise from raw counts or frequencies alone.

But breaks within direct speech do not tell the whole story of characterization here. At times, characters or narrators employ a break in the bridge in reference to the speech of another character.Footnote 50 This occurs in Odysseus and Menelaus’ quotation of gods (Od. 12.47 and 4.526 respectively) but also in more pertinent examples. Although Odysseus breaks the bridge eight times in the Odyssey, the only time he breaks it in the Iliad is when he criticizes the notorious speech practices of Thersites (Il. 2.246–7):

As Martin has argued, Thersites’ epithet akritomythe, along with the related but not synonymous ametroepês (‘having unmeasured utterance’, Il. 2.212), characterizes him as a subpar hero whose language reflects his lack of social standing.Footnote 51 He has bad style, slurs his speech through excessive correption (shortening of long vowels and diphthongs) and synizesis (combining two separate vowels into one). As Solomon points out, Odysseus breaks Hermann’s Bridge in the same breath with which he criticizes Thersites’ way of speaking as ‘an ironic mimicry of Thersites’ crude speech’.Footnote 52 This criticism incorporates the περ ἐών construction discussed above (§2), whose other most prominent variation interchanges ‘fighter’ (πολεμιστής, Il. 5.571, 10.547, 15.585) for ‘speaker’ (ἀγορητής); if the break in the construction did in fact register with an audience, perhaps this formulaic variation is likewise felt all the more behind the pronouncement and contributes to the internal audience’s response to Thersites as a poor speaker but to Odysseus as one who both ‘leads good counsel and marshalls for battle’ (βουλάς τ’ ἐξάρχων ἀγαθὰς πόλεμόν τε κορύσσων, Il. 2.273).Footnote 53 When assessing the narrative stylistics of breaks in Hermann’s Bridge, one must also take into account their narratival contexts.

4. QUASI-BREAKS

Quasi-breaks in Hermann’s Bridge can be defined as caesura after the fourth trochee that do not qualify as breaks under Schein’s definition, that is, the caesura is either not preceded by a polysyllabic word or is otherwise preceded by a prepositive or followed by a postpostive.Footnote 54 The corpus has 2,373 quasi-breaks (out of 72,977 lines), which is 95.8% of total caesurae after the fourth trochee. Even when not meeting the definition of a break, caesurae appear at this position in the line less frequently than at any other, less than the runner-up position immediately before the final syllable, and far less than the position of Meyer’s Bridge, between the two shorts of the second foot.Footnote 55 While a thorough survey of the statistics is beyond the confines of this article, it is possible to gesture towards a way that the more complete dataset can assist in studying the stylistics of quasi-breaks. For example, Martin has argued that καί with correption and synizesis positioned before caesura characterizes Hesiodic more than Homeric poetry (for example, ἀθανάτοις διέταξεν ὁμῶς καὶ ¦¦ ἐπέφραδε τιμάς Theog. 74, with ¦¦ denoting a quasi-break).Footnote 56 The survey of breaks in this dataset confirms this and specifies it further. 18 out of 2,352 lines of Hesiodic poetry (Theog., Op., [Sc.]) contain a quasi-break preceded by καί—thus, 0.77% or once every 131 lines; this contrasts with 108 out of 27,790 lines in Homer (Il., Od.), that is, 0.39% or every 257 lines. Hesiod employs the καί before the caesura twice as much as Homer, and as Martin argues, this stylistic point allows us to extrapolate into the possible agonistic composition of Delos and Delphic sections of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo.Footnote 57 The database accompanies this article to allow additional linguistic and stylistic study of these lines which do not break the bridge according to Schein but come close enough to be noteworthy under certain circumstances.

5. CONCLUSION: STYLISTICS OF HERMANN’S BRIDGE

The sections above provide a framework for analyzing the stylistic contexts of breaks in Hermann’s bridge by corpus, construction and narrative. By applying a single definition of the break, it is possible to build this analytical structure and explore ways to understand where breaks occur and who employs them. This exploration provides necessary supplements to existing applications in previous scholarship and identifies several heretofore unknown tendencies.Footnote 58 Αlthough there is a general trend from allowance to avoidance of breaks over the millennium of active hexameter production, Hellenistic authors such as Aratus and Theocritus and the Imperial author Quintus of Smyrna all employ breaks in non-trivial amounts. Conversely, Apollonius of Rhodes and especially Nonnus are fastidious in their maintenance of the bridge, the latter of whom does so against all probability. Sometimes breaks concentrate in particular poems or sections of poems, namely in Odyssey 20 and in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Attention to repeated lines and constructions reveal that lines containing a break are not repeated across poems, but stylometry of breaks uncovered constructions of phoneme, syntax and metre—that is, the [verb] δ᾽ ἄρα and περ ἔων constructions—that regularly employ the break in various authors and time periods. These formulaic constructions have a special status as both traditional as well as arhythmic in their break of the bridge, a difference from other constructions that may have been felt by an audience. Such constructional analysis shows the extent that the irregularity of the break could be incorporated into units of composition.

The narratological context of breaks in particular opens up new possibilities in analysis of characterization in epic. By measuring not only the number and frequency of breaks in character speech—facts which themselves were previously unknown and made possible by computational examination of the corpus—but also the probability of the attested breaks given the frequency of breaks in the corpus, we can now identify a spectrum of characters that break the bridge with more or less likelihood. Although the amount to which metrical anomalies characterize speakers remains to be seen, for characters such as Telemachus, metrical behaviours may play a larger role in defining what kind of hero he is, one still in the process of learning the rhetoric of heroes and the command of mythos among men.Footnote 59 This study provides both data and the likelihood measure so that scholarship can proceed in its scrutiny of the metrical behaviour of character speech, of both epic’s most celebrated as well as its less studied characters.

Future studies of Hermann’s Bridge will benefit from the stylistic frame, statistical approach and compendium of caesurae between the two shorts of the fourth foot, but the goal of this article has not been to settle arguments concerning the break’s definition. Rather, the data allow us to begin to construct stylistic categories that can accommodate definitional revision, as well as basic information for prosodic and linguistic debate, with the aim to read the passages in which the breaks occur more closely. This methodological chassis could also be applied to other trends in caesurae, such as propensities for certain primary caesurae or diaereses in discursive types, characters, authors or eras. In general, we need to be sensitive to ruptures in metrical patterns, including irregular caesurae, and how they can affect our reading of Greek hexameter texts. The rhythms of Greek hexameter are composed of a variety of normative patterns, be they of caesurae, cola, metrical shapes, lemmata, elisions, correption, bridges or otherwise. These patterns and their stylistic effects can uncover new modes of attention that are not only statistically informed but also leverage computation for the close reading and appreciation of Greek epic.

APPENDIX: BREAKS IN HERMANN’S BRIDGE (AS DEFINED BY SCHEIN [N. 6], INCLUDING ENCLITICS) IN HEXAMETER CORPUS

Iliad

1.168 ἔρχομ’ ἔχων ἐπὶ νῆας, ἐπεί κε || κάμω πολεμίζων.

2.246 Θερσῖτ’ ἀκριτόμυθε, λιγύς περ || ἐὼν ἀγορητής,

2.475 ῥεῖα διακρίνωσιν ἐπεί κε || νομῷ μιγέωσιν,

3.227 ἔξοχος Ἀργείων κεφαλήν τε || καὶ εὐρέας ὤμους;

3.381 ῥεῖα μάλ’ ὥς τε θεός, ἐκάλυψε || δ’ ἄρ’ ἠέρι πολλῇ,

4.460 ἐν δὲ μετώπῳ πῆξε, πέρησε || δ’ ἄρ’ ὀστέον εἴσω

5.252 μή τι φόβον δ’ ἀγόρευ’, ἐπεὶ οὐδὲ || σὲ πεισέμεν οἴω.

5.571 Αἰνείας δ’ οὐ μεῖνε θοός περ || ἐὼν πολεμιστὴς

6.2 πολλὰ δ’ ἄρ’ ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθ’ ἴθυσε || μάχη πεδίοιο

6.10 ἐν δὲ μετώπῳ πῆξε, πέρησε || δ’ ἄρ’ ὀστέον εἴσω

8.163 νῦν δέ σ’ ἀτιμήσουσι· γυναικὸς || ἄρ’ ἀντὶ τέτυξο.

9.189 τῇ ὅ γε θυμὸν ἔτερπεν, ἄειδε || δ’ ἄρα κλέα ἀνδρῶν.

9.394 Πηλεύς θήν μοι ἔπειτα γυναῖκα || γαμέσσεται αὐτός.

9.482 μοῦνον τηλύγετον πολλοῖσιν || ἐπὶ κτεάτεσσι,

9.550 ὄφρα μὲν οὖν Μελέαγρος ἄρηι || φίλος πολέμιζε,

10.96 ἀλλ’ εἴ τι δραίνεις, ἐπεὶ οὐδὲ || σέ γ’ ὕπνος ἱκάνει,

10.317 αὐτὰρ ὃ μοῦνος ἔην μετὰ πέντε || κασιγνήτῃσιν.

10.549 μιμνάζειν παρὰ νηυσὶ γέρων περ || ἐὼν πολεμιστής·

11.463 τρὶς δ’ ἄϊεν ἰάχοντος ἄρηι || φίλος Μενέλαος.

11.686 τοὺς ἴμεν οἷσι χρεῖος ὀφείλετ’ || ἐν Ἤλιδι δίῃ·

11.698 καὶ γὰρ τῷ χρεῖος μέγ’ ὀφείλετ’ || ἐν Ἤλιδι δίῃ

15.585 Ἀντίλοχος δ’ οὐ μεῖνε θοός περ || ἐὼν πολεμιστής,

16.143 Πηλιάδα μελίην, τὴν πατρὶ || φίλῳ πόρε Χείρων

16.347 νέρθεν ὑπ’ ἐγκεφάλοιο, κέασσε || δ’ ἄρ’ ὀστέα λευκά·

16.627 Μηριόνη τί σὺ ταῦτα καὶ ἐσθλὸς || ἐὼν ἀγορεύεις;

17.406 ἂψ ἀπονοστήσειν, ἐπεὶ οὐδὲ || τὸ ἔλπετο πάμπαν

17.719 νῶϊ μαχησόμεθα Τρωσίν τε || καὶ Ἕκτορι δίῳ

19.82 ἢ εἴποι; βλάβεται δὲ λιγύς περ || ἐὼν ἀγορητής.

19.390 Πηλιάδα μελίην, τὴν πατρὶ || φίλῳ πόρε Χείρων

20.444 ῥεῖα μάλ’ ὥς τε θεός, ἐκάλυψε || δ’ ἄρ’ ἠέρι πολλῇ.

21.549 φηγῷ κεκλιμένος· κεκάλυπτο || δ’ ἄρ’ ἠέρι πολλῇ.

21.575 ταρβεῖ οὐδὲ φοβεῖται, ἐπεί κεν || ὑλαγμὸν ἀκούσῃ·

21.597 ἀλλά μιν ἐξήρπαξε, κάλυψε || δ’ ἄρ’ ἠέρι πολλῇ,

22.509 αἰόλαι εὐλαὶ ἔδονται, ἐπεί κε || κύνες κορέσωνται

23.76 νίσομαι ἐξ Ἀΐδαο, ἐπήν με || πυρὸς λελάχητε.

23.306 Ἀντίλοχ’ ἤτοι μέν σε νέον περ || ἐόντ’ ἐφίλησαν

23.587 ἄνσχεο νῦν· πολλὸν γὰρ ἔγωγε || νεώτερός εἰμι

23.760 ἄγχι μάλ’, ὡς ὅτε τίς τε γυναικὸς || ἐϋζώνοιο

24.35 τὸν νῦν οὐκ ἔτλητε νέκυν περ || ἐόντα σαῶσαι

24.60 θρέψά τε καὶ ἀτίτηλα καὶ ἀνδρὶ || πόρον παράκοιτιν

24.753 ἐς Σάμον ἔς τ’ Ἴμβρον καὶ Λῆμνον || ἀμιχθαλόεσσα

Odyssey

1.241 νῦν δέ μιν ἀκλειῶς ἅρπυιαι || ἀνηρείψαντο·

1.390 καί κεν τοῦτ’ ἐθέλοιμι Διός γε || διδόντος ἀρέσθαι.

4.526 χρυσοῦ δοιὰ τάλαντα· φύλασσε || δ’ ὅ γ’ εἰς ἐνιαυτόν,

4.684 μὴ μνηστεύσαντες μηδ’ ἄλλοθ’ || ὁμιλήσαντες

5.272 Πληϊάδας τ’ ἐσορῶντι καὶ ὀψὲ || δύοντα Βοώτην

5.400 ἀλλ’ ὅτε τόσσον ἀπῆν ὅσσον τε || γέγωνε βοήσας,

6.294 τόσσον ἀπὸ πτόλιος, ὅσσον τε || γέγωνε βοήσας.

7.192 μνησόμεθ’, ὥς χ’ ὁ ξεῖνος ἄνευθε || πόνου καὶ ἀνίης

8.554 ἀλλ’ ἐπὶ πᾶσι τίθενται, ἐπεί κε || τέκωσι, τοκῆες.

9.473 ἀλλ’ ὅτε τόσσον ἀπῆν, ὅσσον τε || γέγωνε βοήσας,

10.415 δακρυόεντες ἔχυντο· δόκησε || δ’ ἄρα σφίσι θυμός

12.47 ἀλλὰ παρεξελάαν, ἐπὶ δ’ οὔατ’ || ἀλεῖψαι ἑταίρων

12.181 ἀλλ’ ὅτε τόσσον ἀπῆμεν ὅσον τε || γέγωνε βοήσας,

14.371 νῦν δέ μιν ἀκλειῶς ἅρπυιαι || ἀνηρείψαντο.

15.277 ἀλλά με νηὸς ἔφεσσαι, ἐπεί σε || φυγὼν ἱκέτευσα,

17.111 ἐνδυκέως ἐφίλει, ὡς εἴ τε || πατὴρ ἑὸν υἱόν

17.381 Ἀντίνο’, οὐ μὲν καλὰ καὶ ἐσθλὸς || ἐὼν ἀγορεύεις·

17.399 μύθῳ ἀναγκαίῳ· μὴ τοῦτο || θεὸς τελέσειε.

18.105 ἐνταυθοῖ νῦν ἧσο σύας τε || κύνας τ’ ἀπερύκων,

18.140 πατρί τ’ ἐμῷ πίσυνος καὶ ἐμοῖσι || κασιγνήτοισι.

18.150 μνηστῆρας καὶ κεῖνον, ἐπεί κε || μέλαθρον ὑπέλθῃ.

19.253 νῦν μὲν δή μοι, ξεῖνε, πάρος περ || ἐὼν ἐλεεινός,

20.42 εἴ περ γὰρ κτείναιμι Διός τε || σέθεν τε ἕκητι,

20.77 τόφρα δὲ τὰς κούρας ἅρπυιαι || ἀνηρείψαντο

20.223 ἐξικόμην φεύγων, ἐπεὶ οὐκέτ’ || ἀνεκτὰ πέλονται·

20.274 παύσαμεν ἐν μεγάροισι, λιγύν περ || ἐόντ’ ἀγορητήν.

20.344 μύθῳ ἀναγκαίῳ· μὴ τοῦτο || θεὸς τελέσειεν.

21.345 κρείσσων, ᾧ κ’ ἐθέλω, δόμεναί τε || καὶ ἀρνήσασθαι,

22.501 κλαυθμοῦ καὶ στοναχῆς, γίγνωσκε || δ’ ἄρα φρεσὶ πάσας

Homeric Hymns

1.5 ἄλλοι δ’ ἐν Θήβῃσιν, ἄναξ, σε || λέγουσι γενέσθαι,

2.17 Νύσιον ἂμ πεδίον, τῇ ὄρουσεν || ἄναξ Πολυδέγμων

2.20 ἦγ’ ὀλοφυρομένην· ἰάχησε || δ’ ἄρ’ ὄρθια φωνῇ,

2.208 πίνειν οἶνον ἐρυθρόν· ἄνωγε || δ’ ἄρ’ ἄλφι καὶ ὕδωρ

2.248 τέκνον Δημοφόων, ξείνη σε || πυρὶ ἔνι πολλῷ

2.432 πόλλ’ ἀεκαζομένην· ἐβόησα || δ’ ἄρ’ ὄρθια φωνῇ.

2.452 ἑστήκει πανάφυλλον· ἔκευθε || δ’ ἄρα κρῖ λευκόν

3.36 Ἴμβρος τ’ εὐκτιμένη καὶ Λῆμνος || ἀμιχθαλόεσσα

Hesiod

Theog. 319 ἣ δὲ Χίμαιραν ἔτικτε πνέουσαν || ἀμαιμάκετον πῦρ,

Op. 751 παῖδα δυωδεκαταῖον, ὅτ’ ἀνέρ’ || ἀνήνορα ποιεῖ,

[Sc.] 373 τῶν δ’ ὕπο σευομένων κανάχιζε || πόσ’ εὐρεῖα χθών.

Aratus, Phaenomena

186 αὐτὰρ ἀπὸ ζώνης ὀλίγον κε || μεταβλέψειας

585 κεῖναί οἱ καὶ νύκτες ἐπ’ ὀψὲ || δύοντι λέγονται.

634 καμπαὶ δ’ ἂν Ποταμοῖο καὶ αὐτίκ’ || ἐπερχομένοιο

903 εἰ δὲ μελαίνηται, τοὶ δ’ αὐτίκ’ || ἐοικότες ὦσιν

1023 νύκτερον ἀείδουσα, καὶ ὀψὲ || βοῶντε κολοιοί,

Theocritus, Idylls

14.70 λευκαίνων ὁ χρόνος· ποιεῖν τι || δεῖ, ἇς γόνυ χλωρόν.

15.25 ὧν ἴδες, ὧν εἶπες καὶ ἰδοῖσα || τὺ τῷ μὴ ἰδόντι.

18.15 κεἰς ἔτος ἐξ ἔτεος Μενέλαε || τεὰ νυὸς ἅδε.

23.3 μίσει τὸν φιλέοντα καὶ οὐδὲ || ἓν ἅμερον εἶχε,

24.1 Ἡρακλέα δεκάμηνον ἐόντα || πόχ’ ἁ Μιδεᾶτις

24.102 Τειρεσίας πολλοῖσι βαρύς περ || ἐὼν ἐνιαυτοῖς.

26.15 μαίνετο μέν θ’ αὕτα, μαίνοντο || δ’ ἄρ’ εὐθὺ καὶ ἄλλαι.

Quintus of Smyrna, Fall of Troy

3.185 ὣς Τρῶες φοβέοντο καὶ οὐκέτ’ || ἐόντ’ Ἀχιλῆα.

3.336 ἤρκεσαν ἱεμένῳ· ἐκέχυντο || δ’ ἄρ’ ἄλλυδις ἄλλοι

4.287 αἰδόμενοι ὑπόειξαν, ἐπεί ῥα || γεραίτερος ἦεν.

5.152 ἀλλ’ ἄγ’ ἐμοὶ πείθεσθον, ἐπεί ῥα || γεραίτερός εἰμι

5.209 δαῖτα κυσὶ σφετέροισι, καὶ οὐκ ἂν || ἐμεῖο μενοίνας

7.40 μύρεσθ’ οἷα γυναῖκα παρ’ οὐκέτ’ || ἐόντι πεσόντα·

7.390a τηλόθι κεκλόμενος φίλου ἀνδρὸς || ἐς ἀλλότριον δῶ.

9.393 ἰῶν πεπληθυῖα· πέλοντο || δ’ ἄρ’ οἱ μὲν ἐπ’ ἄγρην,

11.96 φοίνικες θαλέθουσι, φέρουσι || δ’ ἀπείρονα καρπόν,

14.642 ἐκλύσθη δὲ θάλασσα καὶ εἰσέτ’ || ἴσαν κελάδοντες