1.1 Early Influences

King’s radical and transnational consciousnesses intersected with and were framed early in his life by three significant influences: his fundamentalist Christian identity; his father, Martin Luther King Sr. (Daddy King); and American racism and poverty. One might argue that King’s upbringing was unremarkable for an upper-middle-class, Black, Baptist child in a racially stratified Atlanta, Georgia. Still, his socio-economic class in and of itself may in fact be remarkable when considering the economic conditions of most Black Atlantans in the early twentieth century. In the 1920s and 1930s, most Black people in Georgia and throughout the United States were poor.Footnote 1 King was privileged. He grew up in what he referred to as a deeply religious community of “average income” and “ordinary in terms of social status.”Footnote 2 Perhaps King’s definition of ordinary was modest, as he was raised in a largely middle-class, upwardly mobile area called Sweet Auburn. King’s father was a “prosperous young pastor” who “never lived in a rented home.”Footnote 3 Indeed, King enjoyed the privilege and comforts Daddy King provided.Footnote 4

Comprising only about two square miles in size, Sweet Auburn was not just a Black middle-class and upper-middle-class Christian community; it was the gathering place of a generation of men and women who rose above Georgia’s legacy of enslavement and Black codes and were devoted to defeating Jim Crowism. In 1956, Fortune magazine described Sweet Auburn and Auburn Avenue, specifically, as the “richest Negro Street in the world.”Footnote 5 It was the political, cultural, social, spiritual, and commercial center of Black life in Atlanta; it was also the home of Ebenezer Baptist Church, where three generations of Kings served as pastors. Sweet Auburn was a national beacon of light for African American business, entrepreneurship, and civic engagement. Auburn Avenue hosted offices for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Odd Fellows, the Prince Hall Masons, the National Urban League, Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Atlanta Daily World (one of the nation’s oldest Black-owned newspapers), and a host of restaurants and clubs. Racial segregation forced Sweet Auburn to birth its own values-based culture. It was an amalgam of diverse types of Black folk – inclusive of experienced business owners, radical preachers, civil rights activists, and artisans – along with the struggles they endured atop a harsh brand of Jim Crowism.

Sweet Auburn had a sense of its own history and values. King flourished in it. Though surrounded by the brutalities of Jim Crow America, the community provided King with a racial safety net – physically and intellectually – like most segregated communities. Professor Samuel Livingston argues that, in this context, “it is not possible to overstate the influential role of location, in King’s case, Sweet Auburn as a site of cultural memory and identity formation.”Footnote 6 Livingston notes:

Sweet Auburn and Black Atlanta throbbed with the ideas and energy of its local activists, including the leading Pan-Africanist and African Methodist Episcopal Bishop, Henry McNeal Turner, the intellectual force that was Du Bois and, interestingly, the world’s most successful Pan-Africanist proselytizer, the Honorable Marcus Mosiah Garvey. Rev. A. D. Williams and Bishop Turner both shared a childhood shadowed by the harsh reality of enslavement and its vestiges, which fostered a radical commitment to Africans in America born of resistance.Footnote 7

This was the environment that cultivated King. His early consciousness can be traced to his upbringing in Sweet Auburn.

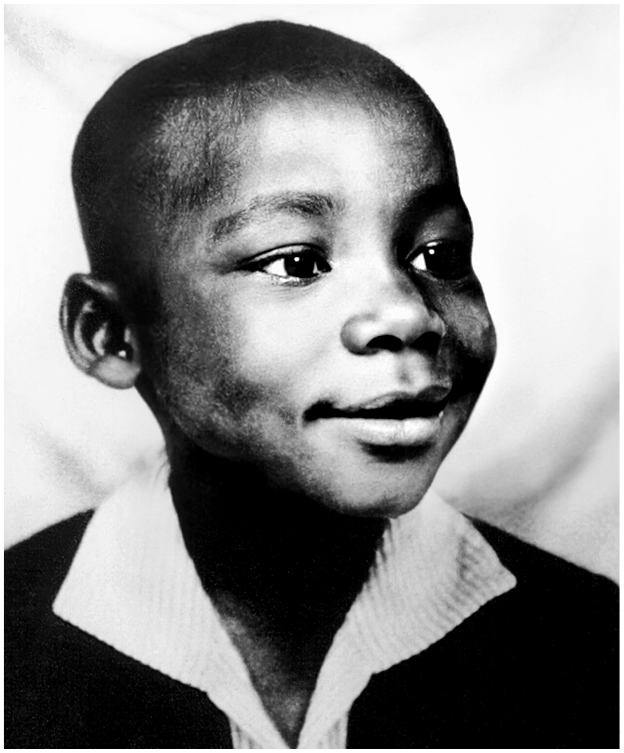

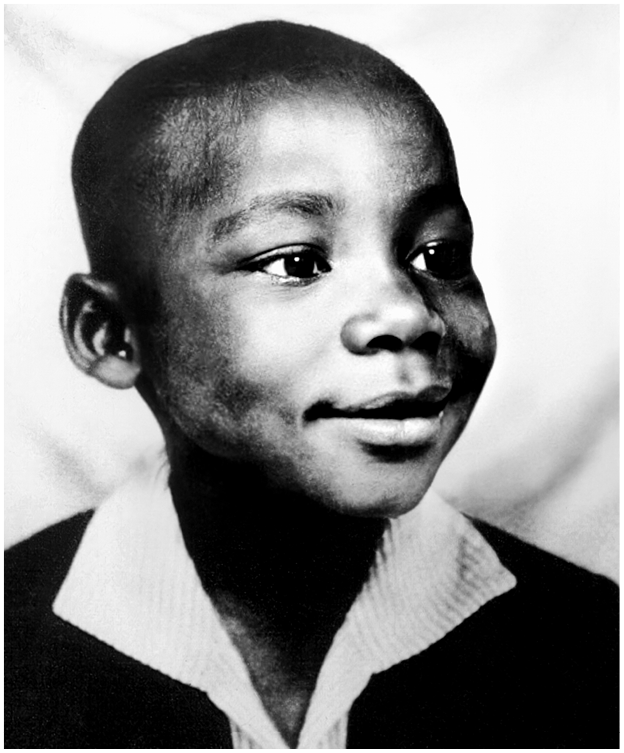

King’s intellectual and cultural environment inside the home was, arguably, even more profound than that outside of it. According to King, his family dressed and ate well, and enjoyed considerable respect in the greater Atlanta community. He was a physically healthy and psychologically strong child, which he credited to his hereditary line (Figure 1.1). King believed that his home life was idyllic; he asserts that his parents did not argue or have significant conflicts.Footnote 8 For King, life was comfortable because his parents provided him with love, stability, and security from the cradle into adulthood. He later remarked that his life “had been wrapped up for me in a Christmas package.”Footnote 9 King noted that it was “quite easy for me to think of a God of love mainly because I grew up in a family where love was central and lovely relationships were ever present.”Footnote 10 Because of his fortunate “childhood experiences,” King was an eternal optimist who viewed the universe and the world as sociable and innocent.Footnote 11

Figure 1.1 1935: the Afro-American politician and leader for the civil rights movement Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) when he was six years old.

By all accounts, King inherited his “strong determination for justice” from his father and his gentleness, sense of self-worth, and ethics from his mother.Footnote 12 His inclination for racial justice, Black pride, and self-respect was rooted in his psychology. This may explain why, in part, King’s conscience was so extraordinary and deeply rooted in what Cedric Robinson referred to as the Black Radical Tradition long before it was an idiom.Footnote 13 King’s mother, Alberta Williams King (Mother King), was his first teacher, educating him in the art of confidence, dignity, and bravery. She imprinted him early with an authentic historical education about slavery, the Civil War, and racial segregation, with all of its limitless normative inequalities.Footnote 14 King’s radical consciousness was seeded by his mother’s early historical, social, and political teachings, which aimed to protect his innocence from inferior thinking by bolstering his self-esteem, motivation, and pride before Jim Crowism emblazoned itself upon him. Mother King was formidable. Her pioneering father (King’s maternal grandfather), Reverend A. D. Williams, had fortified her profound awareness of racial inequities. Williams was a stalwart anti-racist, a human rights activist, and perhaps one the most courageous men of his time in the King family sphere. He served as the first President of the NAACP in 1910, which was a perilous position to hold due to the prevalence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and white citizenry violence against Blacks. This dangerous reality was institutionalized by the KKK’s marriage with local and state law enforcement as well as municipal governments across the South. Williams’s daughter, Mother King, equipped King with the confidence and the will to fight. Meanwhile, Daddy King, who was by far the most influential force in shaping King’s activist consciousness, taught him who, where, and how to fight.

Daddy King was one of Atlanta’s most prominent preachers, ensuring the King family’s economic, social, and political mobility inside and outside Atlanta’s segregated places and spaces. As a result of his father’s prominence, King was certainly more upwardly mobile than the Black masses he would eventually lead. In fact, King was a fourth-generation preacher; all the men on his father’s side were preachers, starting with his great-grandfather and including his brother and uncle. As a Black man raised in the late 1920s and 1930s during the Great Depression and the height of Jim Crowism, it was King’s God-centered and ancestral epistemological foundation that laid the brick and mortar for what would evolve into an uncompromising African and transnational consciousness. His father’s influence in this respect was paramount.

While King ultimately found his spiritual favor and anointing fighting American brokenness in the form of racism, poverty, and war, little about his early life in the segregated South predicted his development into a prophetic, Black, militant, global leader who would reshape the racial and sociopolitical landscape of the US, influence freedom movements in Africa, and continue to inspire civil rights campaigns around the world. Yet the enormous contradictions between God’s law and the evils of racial caste in America stirred King’s soul at an early age. He first articulated his understanding of this contradiction in relation to the issue of poverty when, at the age of five, in the midst of the Great Depression, he asked his parents about the massive breadlines. He later attributed his “anticapitalistic feelings” to first-hand knowledge of American poverty during the Great Depression, with all its racialized suppositions and disparities.Footnote 15

King’s African consciousness was influenced by his development in the Black church tradition – encompassing Judeo-Christian theology interpreted through Black fundamentalist tradition – from birth through adulthood. One can only assume that King’s early empathy and compassion toward persons in poverty were inspired by his father’s liberation-orientated preaching and the benevolent mission of the Black church. Daddy King’s sermons and activities lit a slow-burning fire in King’s consciousness. King’s early training and introduction to Ebenezer’s emphasis on social justice – “to feed the poor, liberate the oppressed, and welcome the stranger”Footnote 16 – profoundly impacted his thinking and theological development. The racial justice education he received from Ebenezer influenced his human rights cosmogony and, arguably, rooted his notion of the three evils of racism, poverty, and war.Footnote 17 When taken together, these focal nodes created nesting dualities with Ebenezer’s core tenets: to liberate the oppressed from racism; feed the poor to end poverty; and welcome the stranger to mitigate war. The symmetry between King’s three evils and Ebenezer’s social justice principles is thought-provoking; Ebenezer defined its three-pronged social justice mission, and King demarcated the three evils that sought to undermine it.

Daddy King pastored at Ebenezer Baptist Church for forty-four years (1931–1975), seeding King’s racial justice and transnationally oriented theology. Daddy King was far more than an Atlantan preacher. By 1934, when King was only five years old, Daddy King had already traveled to Europe (France, Italy, and Germany), Africa (Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt), and the British Mandate for Palestine. On his return, he attended the 1934 World Baptist Conference in Berlin, Germany, and heard the explosive “discourses” of Adolf Hitler on the radio. He witnessed first-hand the militarization of Germany, with the “march of jackboots” and the “unfurling flags with swastikas emblazoned on them.”Footnote 18 Motivated by the Holy Land and nourished spiritually by the “new worlds” he visited, Daddy King continued the fight against racial inequality, inequity, and injustice in the United States.Footnote 19 With this background, one can only surmise that these transnational experiences, combined with his understanding of racial tyranny in the US, awakened new insights that Daddy King shared with his son, emboldening his knowledge, understanding, and interconnectedness with the world outside the US. In fact, in 1935, less than a year after Daddy King’s sojourn in the Global South and Europe with ten other ministers, he claimed to have uncovered the “mysteries of the South’s racial arrangement,” which he described as a dehumanizing system.Footnote 20 One can only wonder what mysteries he shared with King and the impact such understandings had on his son’s development.

In the foreword to Daddy King: An Autobiography of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr., the Honorable Andrew Young opined that Daddy King “laid a firm foundation from which his son could build the civil rights movement in the Sixties” because the younger King “grew up hearing his father preach against the injustices of a segregated society.”Footnote 21 King’s racial awareness and global consciousness were thus birthed at home and in church. As Young put it, “speaking out against injustice was a way of life in Martin’s family.”Footnote 22 Daddy King was a serious person, an “upright Black man” and “change leader” long before such phrases were commonplace. In his confrontations with institutionalized racism and white power structures, Daddy King harkened back to the nightmarish experiences that his own father, James Albert King, had under the tyranny of Jim Crow. He believed that white people did not view Black people as human beings and thus were shameless in their cruelty and savagery toward them.Footnote 23 From Reverend A. D. Williams and Daddy King to Alberta Williams King, Martin Luther King Jr. was thus nurtured into the theology of the Black radical tradition and naturally viewed the plight of Black people, from Atlanta to Addis Ababa, as one people struggling to combat and transform the evils of white domination worldwide.

Daddy King’s truth-telling clearly influenced King. Like father, son, and grandson, their legacy reveals a shared racial history of confrontation and resistance. Daddy King’s penchant for negotiating with the “top man” in charge would also be adopted by King himself, a get-it-done Servant Leader not interested in wasting time dealing with whites who held no real power or authority. Andrew Young argues that King’s bravery was fortified by witnessing Daddy King’s “own determination to fight fearlessly for freedom and justice.”Footnote 24 King witnessed his father fight for racial justice and human equality on the front lines of Jim Crowism in Georgia, firmly believing that there would be “great combat” wherever the Negro lived. Indeed, Daddy King thought that the racialized nature of the American Civil War had never really ended and that, by the 1940s, it would be need to be “fought on several fronts: moral, legal, social, and political.”Footnote 25 He believed that his sons, including King, would “be needed in an ongoing, ever-difficult battle” to free America from its racist past and present.Footnote 26 For Daddy King, Blacks had to struggle because there was “no place to surrender to, no place where people could be spiritually alive. If anything were to give, it would have to be on the white side, where there was room to budge or space to change.”Footnote 27

In his autobiography, Daddy King recollected a painful memory from when, at the age of six, the father of Jay, one of his white friends, referred to him as “just one of my niggers” after being asked who was playing with his son. Being called a nigger by Jay’s father, “reached inside and twisted” young Daddy King up.Footnote 28 He felt dehumanized, not unlike his son King felt when, at the impressionable age of six, the father of two white playmates whose family owned the community store in front of King’s house ordered their sons not to play with him anymore. Like Daddy King, the younger King had been shocked and saddened. For both father and son, the cruel realities of American racism conveyed through the multi-generational impacts of anti-Black racism outraged them and vandalized a vital part of their innocence. In fact, from that moment forward and for years to come, King “was determined to hate every white person” until redirected by his parents not to “hate the white man.”Footnote 29 It was a struggle with an age-old question: “How could I love a race of people who hated me and who had been responsible for breaking me up with one of my best childhood friends?”Footnote 30 The duality of father and son, wrestling with the same indignities of racism as children of distinct generations, nurtured a shared resentment for America’s system of racial segregation and its dangerous impacts on Black life and liberty.

Unfortunately, Daddy King and his son also witnessed other grave injustices. Daddy King witnessed the robbery, beating, and torturous lynching of an innocent Black man for allegedly grinning – a crime perpetrated by jealous white men who worked at a local mill.Footnote 31 This tragedy caused Daddy King to vehemently hate whites, not unlike the sentiments expressed by King decades later after witnessing the “Klan actually beat a Negro” and seeing “spots where Negroes had been savagely lynched.”Footnote 32 King recounted another grim, soul-breaking act of discrimination that he described as one of his angriest moments: At the age of eight, a white woman slapped him in the face and called him a nigger for allegedly stepping on her foot.Footnote 33 White-on-black violence sorely molded father and son when they were children and shaped their perceptions of America, whites, racism, violence, and justice more generally.

The multi-generational impacts of discrimination would inevitably ensnare father and son together when a white clerk tried to force Daddy and a young King to move from sitting in the front of a shoe store to the rear to receive service. The ensuing struggle profoundly affected King and underscored his disdain for racial segregation. He claimed that his conscience was framed during this encounter, as Daddy King refused to sit in the rear and walked out of the store rather than buy Jim Crow shoes.Footnote 34 It was a nonviolent, financial protest of sorts from a man who would not submit to institutionalized racism. One can only infer that at the ages of six and eight, King’s resentment of white supremacy and racial injustice hardened because of these experiences.

Daddy King’s courage did not end with contesting racial segregation in public spaces; he also contested racism by law enforcement. King recounts when his father was pulled over in his vehicle and was pejoratively referred to as “Boy” by a police officer. In response, Daddy King boldly admonished the officer with a stern gaze. He told him that he was “not a boy” before driving away, instilling in King the will and courage to fight structural and interpersonal racism as a social evil.Footnote 35 Needless to say, Daddy King’s actions were taboo and risky in the American South in the 1920s, constituting dangers that King would also challenge head-on in the future.

These childhood experiences prepared King to endure racial segregation with great resilience. From Atlanta’s segregated public parks and YMCAs to its segregated restaurants and theaters, King’s contempt for Jim Crowism was growing, and his willingness to confront it was ripening. For example, when King was fourteen, he traveled from Atlanta to Dublin, Georgia, to compete in an oratory or debate competition, which he won. His speech, “The Negro and the Constitution,” was a sophisticated indictment of Jim Crow and American democracy – realities that he vividly experienced during his bus ride home to Atlanta.Footnote 36 King and his teacher, Mrs. Sarah Grace Bradley, were ordered to move to the back of the bus and stand to accommodate white passengers.Footnote 37 After being cursed at by the bus driver, King was resolved not to move until his teacher persuaded him to do so in obedience to segregationist law.Footnote 38 They stood in the aisle for ninety miles until reaching Atlanta. King felt dehumanized and stated that the experience, which was the “angriest” he had ever been, would never leave his memory.Footnote 39

Daddy King’s example and a raw set of childhood experiences shaped King’s sense of racial justice long before the civil rights movement. Having personally experienced and endured racialized violence, verbal abuse, and dehumanizing bus rides, as well as witnessing KKK violence, economic injustice, police brutality, and racial injustice in the courts, King abhorred racial segregation and its battery of repressive and savage performances. In his autobiography, he wrote, “I had grown up abhorring not only segregation but also the oppressive and barbarous acts that grew out of it.”Footnote 40 This burning desire for equity, equality, and justice inspired him. In a 1967 speech to the American Psychological Association, he argued:

If the Negro needs social sciences for direction and self-understanding, the white society is in even more urgent need. White America needs to understand that it is poisoned to its soul by racism, and the understanding needs to be carefully documented and consequently more difficult to reject. The present crisis arises because although it is historically imperative that our society take the next step to equality, we find ourselves psychologically and socially imprisoned. All too many white Americans are horrified not with the conditions of Negro life but with the product of these conditions – the Negro himself.Footnote 41

These thoughts and hardships were consistent in his consciousness for most of his life, providing King with an uncanny ability to empathize with human suffering in his late teens. This ability deepened during two summers of work in a racially integrated plant, where he “saw economic injustice firsthand, and realized that the poor white was exploited just as much as the Negro.”Footnote 42 This experience made him aware of the interracial complexities of economic inequality and injustice in American society.Footnote 43

His new understanding appears to have broadened his unitary conceptions of racism, which greatly expanded after spending his post-high school summer working on racially integrated tobacco farms in Simsbury, Connecticut.Footnote 44 It was here that he attended his first multiracial church, led an integrated Sunday school class of 107 boys, and socialized in racially mixed restaurants without Jim Crow’s architecture dictating social relations. King’s freedom from openly hostile racism in Simsbury permitted him to socialize with whites in ways unforeseen in the segregated South.Footnote 45 When he returned home after his “freedom summer,” King recounts his bitterness about the incomprehensible and dehumanizing feeling of riding the train from New York to Washington as a freeman and being forced to travel in a segregated “Jim Crow car” from the nation’s capital to Atlanta.Footnote 46 That summer of 1944 proved to be a watershed moment in King’s social consciousness and development. The evils of racial segregation adversely affected his “growing personality” and cemented his dedication to fighting racial injustice to preserve his young sense of “dignity and self-respect.”Footnote 47

1.2 Morehouse College

At the age of fifteen, King entered Morehouse College, which had a dual enrollment program that accepted 11th graders in the wake of the negative impact of the wartime draft on college enrollment among Black people during World War II. He was a legacy student, as his father and maternal grandfather had also attended Morehouse, one of America’s finest historically Black universities and only all-Black men’s college. It is worth noting that, in 1944, King was a third-generation university student, which is remarkable given that only 29 percent of Black Americans hold bachelor’s degrees today. The physical and intellectual safety of Morehouse College allowed King to discuss racialized topics, among others, without retribution. Morehouse professors nurtured a transparent and politically incorrect learning environment where students could imagine “solutions to racial ills.”Footnote 48 This approach was consistent with its motto: “And there was light,” or the Latin Et Facta Est Lux.

Morehouse offered the ideal learning environment for King, who had already developed a “substantial” concern for racial justice issues.Footnote 49 At Morehouse, he was introduced to many scholarly works, such as Henry David Thoreau’s classic essay “On Civil Disobedience.”Footnote 50 King found Thoreau’s willingness to be imprisoned rather than pay taxes that would be used to support war and slavery liberating. The notion that nonviolent resistance could be employed against evil and racist systems fit King’s moral epicenter and eventually rooted his belief in nonviolent resistance. Notably, as King studied the theory of nonviolence in collaboration with whites as a racial justice worker with the Intercollegiate Council,Footnote 51 his resentment of the white race softened. A new spirit of cooperation sprouted in his heart as more whites demonstrated their interest in being allies in the fight against racial segregation.

It was at this stage that King envisioned himself “playing a part in breaking down the legal barriers to Negro rights.”Footnote 52 This urge to fight racial injustice was reflected in a letter to the editor titled “Kick Up Dust,” published in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper,Footnote 53 which he penned during his sophomore year. In challenging the contradictions of white men on the issue of racial integration, King noted that the various advocates of separation and racial purity were also the leaders of “the total mixture in America,” harkening back to the forced rape and subjugation of Blacks during enslavement, particularly of women.Footnote 54 In a tone reminiscent of Marcus Garvey, King’s essay reminded readers that Black men were not “eager to marry white girls, and we would like to have our own girls left alone by both white toughs and white aristocrats.”Footnote 55 He then turned his attention to challenging the innumerable racial injustices plaguing African-Americans. That same year, King also wrote an article titled “The Purpose of Education” in Morehouse’s literary journal, the Maroon Tiger. He argued that one of the aims of education was to give people “unbiased truths,” not “half-truths,” prejudices, and propaganda. He advocated for the importance of critical thinking and suggested that the “goal of true education” should be “intelligence plus character.”Footnote 56

As King’s social consciousness widened, he began to question his faith-calling in ministry, as his studies stirred doubts in his mind about his faith, Negro emotionalism in the church, and religious fundamentalism. He opined that his studies demonstrated that science and religion were often at odds, making him more skeptical about Christianity. He began questioning whether traditional religious predilections “could serve as a vehicle to modern thinking,” commenting that “if we, as a people, had as much religion in our hearts and souls as we have in our legs and feet, we could change the world.”Footnote 57 Such youthful contemplations were not unusual for a sixteen-year-old developing himself as a man and thinker. During this time, King was intellectually curious and a critical Christian thinker but did not initially distinguish himself at Morehouse despite excelling in oratory and debate.Footnote 58 And, after immersing himself in a Bible course likely taught by Dr. George Kelsey, who instructed him in philosophy and religion, King discovered profound truths that caused him to snap back into the greater ecclesiastical understanding of the world.

This growth was also profoundly influenced by Dr. Benjamin Mays, president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967, whom King referred to as a family friend, spiritual and intellectual mentor, and “one of the great influences in my life.”Footnote 59 Mays understood the value and power of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and challenged King and other “Morehouse students to struggle against segregation rather than accommodate themselves to it.”Footnote 60 Like many Black leaders, Mays was influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, whom he befriended. Mays studied Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence and activism years before King became familiar with him. Mays likely first introduced King to Indian freedom movements, including Gandhi’s nonviolent living philosophy of Satya (truth) and ahimsa (nonviolence). When taken together, King’s radical consciousness paralleled Mays’s pro-Black, antiracist, and nonviolent social psychology.

The intellectual giants who influenced King during his time at Morehouse were ministers, scholars, leaders, and learned men “of all of the trends in modern thinking.”Footnote 61 Within this balance between traditional and modern, King sought guidance and, in many ways, deliverance. His years at Morehouse were also the first time he was taught and mentored by men of significant stature and intellectual standing other than his father. His hunger for ministry grew during his senior year at Morehouse College, as did his interest in seminary school.

1.3 Crozer Theological Seminary

In September 1948, at nineteen years old, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, to identify a theological basis to “eliminate social evil.”Footnote 62 He immersed himself in the social, ethical, and philosophical literature of Europe’s preeminent ancient and modern philosophers, including Plato (Greek), Aristotle (Greek), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Genevan), Thomas Hobbes (English), Jeremy Bentham (English), John Stuart Mill (English), and John Locke (English). He also studied and was influenced by the writings of Walter Rauschenbusch (American), whom he credits for ingraining in him a “theological basis for the social concern” at an early age.Footnote 63 One might argue that King’s early philosophical education and mindfulness were framed, in part, by the scholarly works of these renowned intellectuals, who offered a smorgasbord of social ethics rooted in ancient Africa (Egypt) and purloined and acculturated by leading Greek intellectuals and their progeny in Europe and the United States. For example, Aristotle credits Egypt for providing him with advanced knowledge and wisdom, declaring that “Egyptians are reputed to be the oldest of nations, but they have always had laws and a political system.”Footnote 64 Similarly, Plato spent thirteen years in Egypt studying with the African Horite priest Sechnuphis, as did other leading Greek scholars, including Pythagoras, who studied with the Kemetian arch-Prophet Sonches. Thales, Hippocrates, and Socrates also studied in Egypt. All learned Kemetic (Egyptian) knowledge and spirituality at the temple universities of Waset and Ipet Isut (The Most Select of Places) in ancient Egypt. Hence, King reappropriated what the Greeks misappropriated and mistook – African knowledge and philosophy, particularly the MA’AT concept from ancient Egypt – and applied it to help liberate persons of African descent in the United States.Footnote 65

King’s transcendental or global thinking quickly evolved at Crozer, and his convictions grew even more quickly. His human rights-centered perspectives were derived from lived experiences – a pregnant combination of Black Baptist doctrine, pastoral inheritance, academic training, and imprint, on the one hand, and American racism, poverty, and war on the other. King’s societal critiques were domestic and global; not even the church escaped criticism. For example, he argued that “any religion that professes concern for the souls of men and is not equally concerned about the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them, and the social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion only waiting for the day to be buried.”Footnote 66 King’s human rights sensibilities were thus fortified at Crozer, where he employed the Gospel of Jesus as his guiding framework and charter. In the same way that human rights and civil rights attorneys employ the United Nations Charter and the US Constitution, respectively, to advance the more significant moral imperatives of civilized society, King’s foundational doctrine was rooted in the biblical New Testament teachings of Jesus Christ.

Indeed, King’s foundational training at home and in Sweet Auburn’s greater community, as well as at Morehouse College, evolved into liberation fruit during seminary school at Crozer, where he authored a research paper titled “Light on the Old Testament from the Ancient Near East.”Footnote 67 The 1948 paper, which is indicative of King’s “Afro-centric” thinking at the early age of nineteen, was written for Professor James Bennett Pritchard’s class on the Old Testament. It provides insight into King’s thinking about Africa’s role in biblical history through the Hebrew Prophets and in relation to Near East or Ancient Egyptian literature and wisdom. King’s understanding of the connection between Black Egyptian literature and biblical psalms and the spiritual ethos of the modern world was remarkable. For example, he argued that the “composing of proverbs were begun in Egypt” and credited their emergence to Ptah-Hotep, whom he regards as one of the “greatest proverb writers to appear on the Egyptian scene: during the 5th Dynasty (2675 BCE).”Footnote 68 Ptah-Hotep was vizier (chief adviser and administrator) to Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi and is known as one of ancient Egypt’s leading literary figures. He noted elements that were “strikingly” similar to the “Biblical book of Proverbs.”Footnote 69 In the paper, King further examines the influences of King Amenemope III’s (1390–1354 BCE) thinking about “honesty, integrity, self-control and kindness” to the Hebrews, particularly in “Jeremiah, Psalms, and Proverbs.”Footnote 70 These Ma’at-like principles would later serve as the cornerstone of King’s African ministry.

The reclamation and return of biblical history to its African roots was not unique among Pan-African thinking clergy during this period. King followed suit. For example, quoting J. H. Breasted, King also examined the impact of Amenhotep IV, also known as King Akhenaton (1570–1150 BCE), for being “the first individual of history” because he offered a “new idea of God” and birthed monotheism while his empire was predominated by polytheism.Footnote 71 King accurately opines that Akhenaton composed the two hymns of Aton, which he argues are like the 104th Psalm of Hebrews “in thought and sequence” and thus tremendously influenced biblical writers. Referring to the Old Testament and its Black Egyptian roots, King argues that, if accepted as truth, the hymns of Aton are “one of the most logical vehicles of mankind’s deepest devotional thoughts and aspirations, couched in language which retains its original vigor and moral intensity.”Footnote 72 King’s awareness of Africa’s significant influences on biblical history was inimitable and reflective of his African consciousness. One might argue that his research on Africa’s determinative influences on biblical history radicalized him. Egypt’s authoritative role in biblical antiquity emboldened King’s African awareness and the historical and spiritual ethos that cultivated and nurtured it long before he emerged as a national and global human rights leader and icon. King remained a prolific student of ancient and modern Black history and theology in Africa, the Near East, and North America, eventually amassing a personal library of over 1000 books by his early thirties.

From an early age, his access to prominent African American literary works framed his consciousness. In the first part of the twentieth century, only a few mainstream publishers distributed scholarly books by Black scholars. In the segregated South, access to such works was even more difficult; some were even banned. Poor Blacks had virtually no way to obtain the pioneering works of Black scholars; however, King was a fourth-generation pastor and civil rights activist from an upper-middle-class background. There was a library in Daddy and Mother King’s home. Coretta and Martin built a formidable collection of books in the 1950s that included groundbreaking works incorporating various topics, including enslavement, slavery, racism, Africa, poverty, and Christianity. King appeared to have been significantly influenced by David Walker’s Appeal, Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited, Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana: Autobiography, and the teachings and writings of Benjamin Mays. In addition, several classical works on Africa, Pan-Africanism, religion in Africa, and Black reparations informed his library and seemingly his thinking, such as Louis E. Lomax’s 1960 classic, Reluctant African; Mahatma Gandhi’s 1928 Satyagraha in South Africa; Ralph Korngold’s 1945 biography Citizen Toussaint; Ralph Ellison’s 1945 masterpiece Invisible Man; George Padmore’s 1956 masterpiece, Pan-Africanism, or Communism? The Coming Struggle for Africa; and the Civil Rights Congress’s bold 1951 We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government against the Negro People. King likely read most of these texts before the age of twenty-five and developed notable expertise on the intersections of racism, colonialism, and Apartheid on Africa and Black Americans.

Likewise, King’s study and reflections on the predominant global economic theories and systems, such as capitalism and communism, was bold. He patently rejected the works of Karl Marx and other communist theorists despite being accused of having socialist leanings, a typical smear levied by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). He shunned communism’s “secularistic and materialistic” orientation, unethical means-to-an-end relativism, proclivity for political totalitarianism, and deprivation of individual freedoms. King argued, “Man is not made for the state; the state is made for man,” and, “Man must never be treated as a means to an end of the state, but always as an end within himself.”Footnote 73 In his view, communism had “no place for God,” and, thus, he could never accept it. King considered communism “basically evil,” a system comprised of “false assumptions and evil methods.”Footnote 74 He also prophetically opined that capitalism raised vital concerns “about the gulf between superfluous wealth and abject poverty” and too often inspired people to “be more concerned about making a living than making a life.”Footnote 75 King questioned the moral foundations of capitalism, God, and profit. He valued people above profit, human development over economic development, and “service and relationship to humanity” over the profit motive matrix.Footnote 76 He argued that capitalism might evolve into a practical materialism that would be as “pernicious as the materialism taught by communism.”Footnote 77

King’s ability to grasp the theoretical and practical aspects of Cold War politics, economics, and theatrics in the late 1940s was extraordinary, as was his ability to use Black Christian values to critique them. To King, “The Kingdom of God is neither the thesis of individual enterprise nor the antithesis of collective enterprise, but a synthesis which reconciles the truths of both.”Footnote 78 He embraced the biblical belief that the life and death of Jesus Christ were intended to give people peace with God and themselves, which is why King taught his disciples and followers to turn the other cheek when assaulted by evil, to resolve conflicts peacefully, to be peacemakers in society, and that all happenings in the world occur when God chooses. He appears to have grasped onto the sacred biblical principle reflected in the Book of Matthew: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.”Footnote 79 King understood that Jesus sends his disciples into an ugly, violent, and hateful world to make peace between God and men, among nations, and among the people themselves.

Crozer Theological Seminary greatly influenced King’s thinking and approach to American racism. And while his philosophical approach was derived from the Gospel of Yehoshua, his thinking received fortification while attending a lecture by Dr. A. J. Muste, executive director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). FOR was “an international pacifist organization that drew on Gandhi’s philosophy of peaceful resistance,” as Jonathan Eig notes.Footnote 80 He continues, “FOR’s leading voice was A. J. Muste, a minister who called for the conscious violation of unjust government laws and actions and encouraged his followers to go to jail for their beliefs.”Footnote 81 Muste believed that incarceration and aggression were necessary to awaken the public’s conscience, a tactical position that became the cornerstone of King’s philosophy of nonviolence.

King sought to expose the violence and brutality of those opposing racial equality, using his enemies’ violence as a negative good. While King was acutely aware that war couldn’t serve a “positive or absolute good,” he opined that “it could serve as a negative good” by halting an “evil force” such as regimes predicated on Apartheid and other forms of totalitarianism such as Racism, Nazism, Fascism, or Communism.Footnote 82 Interestingly, this “negative good” logic underscored the rationale for the creation of the UN’s first large-scale and heavily armed peacekeeping operation in the Congo in 1960, where it used defensive violence for an adverse good. King supported this UN action. At this juncture, though vacillating on the “power of love to solve social problems,” King provisionally believed that the “only way” to defeat segregation was through “armed revolt,”Footnote 83 a theoretical position akin to many Pan-Africanist and Black Nationalist thinkers and activists at the time. He believed that the “Christian ethic of love was confined to individual relationships” and not applicable to social evils; he did not yet know how love could be employed to combat social conflict.Footnote 84 However, his thinking shifted after attending a sermon by Dr. Mordecai Johnson, president of Howard University. Johnson, a mentor to King, preached about the life, teachings, and legacy of Mahatma Gandhi, leaving an enduring impression on King.Footnote 85 From this point forward, King immersed himself into the Gandhian philosophy of nonviolent resistance, which influenced his approach to fighting social evil for the rest of his life.

Gandhi’s transcendental philosophy of nonviolence was not simply theoretical but a way of life. It was and is aggressive, used as a “moral weapon” that relies on “soul force over physical force.”Footnote 86 It seeks to win the “enemy through love and patient suffering.”Footnote 87 Derived from the Satyagraha philosophy, which means “soul force,” not “brute force,” Gandhi originated his philosophy of nonviolent resistance to combat white South African repression in South Africa and British domination in India.Footnote 88 Satyagraha is predicated on three concepts: Satya (truth), Ahimsa (nonviolence, or refusing to injure others), and Tapasya (self-sacrifice). Although the cosmogony of Satyagraha had Indian roots, its birthplace was in Johannesburg, South Africa, where Gandhi fought for the civil rights of Indians. Gandhi later employed it in India to engage in massive civil disobedience, leading to the renowned 1930 Salt March against British colonial domination. Ironically, King’s adoption of Satyagraha philosophy and tactics as a strategy and approach to combat racial segregation in the US reflected the reclamation of strategies that originated in his ancestral homeland, Africa. King commented, “It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking.”Footnote 89

Initially, King struggled with the power of love as a vehicle for social change outside of the context of interpersonal conflict, and he questioned Christianity’s “turn the other cheek” and “love your enemies” philosophies.Footnote 90 Initially, he did not believe that love was a potent weapon against racial conflict or interstate disputes; however, through Gandhism, his skepticism diminished when he discovered love’s power in the “area of social reform.”Footnote 91 King remarked, “Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale.”Footnote 92 Indeed, Satyagraha’s effectiveness against racism in South Africa and Jim Crowism in the US validated its bona fides as a potent antiracist Indo-African philosophy and methodology. Despite being sixty years apart in age and advocating in different eras and regions of the world, Gandhi and King employed nonviolent resistance for the same reasons: racial segregation in public transportation, including buses and trains, as well as equal voting rights with whites.

Simply put, King’s eyes opened at Crozer. He enjoyed his spiritual pilgrimage there and sharpened his critical thinking and analytical skills. Ultimately, he fully embraced Gandhism not only to upend racism but to address theological liberalism. He was especially drawn to “its devotion to the search for truth, its insistence on an open and analytical mind, and its refusal to abandon the best light of reason.”Footnote 93 King went so far as to suggest that the “Gandhian approach” may “bring about a solution to the race problem in America.”Footnote 94 This enormous intellectual pronouncement steered King’s approach to America’s race dilemma until his untimely death. Ultimately, Crozer helped fortify and influence King’s intellectual and spiritual awareness through its diverse intellectual voices and its introduction to transnational philosophical criticisms and interpretations of biblical literature and social change. While at Crozer, the works of luminaries such as A. J. Muste, Gandhi, and Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (American), nourished King’s growing consciousness and spiritual solutions to America’s entrenched race problem.

1.4 Boston University School of Theology

In September 1951, King began his doctoral studies at Boston University’s School of Theology (BU). He was interested in attending BU because of the scholarly writings and pursuits of faculty members like Edgar S. Brightman (an American philosopher), with whom he desired to study, and because George W. Davis, one of his choice professors at Crozer, had studied there and supported his admission.Footnote 95 King’s intellectual sojourn evolved to the next level at BU, particularly his thinking about nonviolent movements. BU provided King with access to various scholars, practitioners, and domestic and international student practitioners of nonviolent resistance, pacifism, and social justice. King seemed particularly fond of Dean Walter Muelder and Professor Allen Knight Chalmers because of their profound concern for the human condition. Their teachings encouraged him to deepen his understanding of the philosophy and theory of nonviolence as it related to the challenges of liberalism as a cure for social evils and the relevance of neoorthodoxy to racial justice.Footnote 96 Overall, BU allowed him to build and expand on his interests in the ecclesiastical intersections between racial justice and nonviolence.

King’s heightened interests in the symbiotic relationship between social justice and pacifism expanded under professors Brightman and Lotan Harold DeWolf (an American Minister and Theologian).Footnote 97 King credits Brightman for giving him “the metaphysical and philosophical grounding for the idea of a personal God.”Footnote 98 This meant that an individual’s personal experience centered their faith because, in Brightman’s view, “all religion is of, by, and for persons. Religion ascribes a unique value to persons and has a unique interest in their welfare and their salvation.”Footnote 99 Brightman heavily influenced King’s philosophy, particularly his belief in Personalistic philosophy – the notion that reality was, in the long run, found in personality. This approach reinforced King’s belief in a personal God with whom one could be in a vertical relationship. It was, in King’s words, “a metaphysical basis for the dignity and worth of all human personality,”Footnote 100 which itself is a core human rights principle enshrined in the United Nations Charter (1945) and the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (1948).Footnote 101 For example, the Preamble of the United Nations Charter reaffirms “faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.”Footnote 102 Furthermore, Article 1 of the United Nations Charter states, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”Footnote 103 Articles 2 and 3 build on this foundation by prohibiting racial segregation and other forms of discrimination and by codifying the right to life, liberty, and security for every living being.Footnote 104 King was aware of the UN’s human rights doctrine, and, intuitively, his belief in one’s upright relationship with God and the natural dignity of every human being became the cornerstone of Kingsian thinking. These beliefs specifically influenced the direction of his doctoral dissertation. Titled “A Comparison of the Conception of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman,” it provides a sojourn into the “central place” God “occupies in any religion” as well as the need for people to “interpret and clarify the God-concept.”Footnote 105

Interestingly, when King prepared his dissertation, “America’s” most prominent and recognized theologists and philosophers of mainstream religion were white Americans and Europeans, as were the theoretical constructs of God that influenced King. It is remarkable, therefore, that in Stride Toward Freedom, King did not refer to Howard Thurman, the Black theological luminary who was a friend and former classmate of Daddy King at Morehouse College and who served as the first Black Dean of Boston University’s Marsh Chapel for at least one year during King’s tenure as a doctoral student.Footnote 106 Unlike King, Thurman met with and developed a relationship with Mahatma Gandhi (1936), who, despite having a questionable history of supporting Black liberation in South Africa, demonstrated a keen interest in the African-American freedom struggle. He even prophetically opined to Thurman that “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”Footnote 107 King’s failure to reference Thurman is puzzling given that Thurman deepened King’s understanding of Gandhi, served as his spiritual mentor, and laid the groundwork for King thirty years before his ascendency as a global leader. Thurman was among the first African Americans to study and adopt Gandhi’s Satyagraha approach to nonviolent resistance, and he had extensive experience traveling and working in Africa, particularly in Egypt (1935), Djibouti (French Somaliland, 1935), and Nigeria (1960), where he taught at the University of Ibadan. Despite not appropriately recognizing him in his works, King clearly embraced Thurman’s teachings and was undoubtedly influenced by his transnational theology, as evidenced by his strong embrace of Thurman’s seminal work, Jesus and the Disinherited, during his doctoral studies. Significantly, King carried Thurman’s book with him during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Still, King’s omission of Thurman and others in his biographical works is disconcerting because it deprives the reader of learning more about the diverse and even radical intellectual influences on King’s thinking and theology. On this point, Clayborn Carson notes that “[rather] than citing these African American influences, King presented himself in Stride as a black leader familiar with European America [and European] intellectual trends.”Footnote 108 One can surmise that he did not reference any towering Black figures as influences because he maintained personal relationships with them, particularly Mays, Johnson, and Thurman, whom he corresponded with for several years after graduating from Boston University. Nevertheless, the Anglicized and Europeanized concepts King gravitated toward were built upon the Black radical tradition of interpretive preaching that originally rooted his thinking and racial justice analytics. King’s mother, father, and the world that was Sweet Auburn and Ebenezer Baptist Church seeded his “conviction that nonviolent resistance was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their quest for social justice.”Footnote 109 King embraced Daddy King’s liberating theology and philosophy before being baptized by the thinking of white theologians and scholars, but he employed knowledge from both quarters to inject moral ethics and liberation theology into his fight against white supremacy or the dominant culture. He was committed to uprooting social evil in society even without, at this stage, knowing how “to organize it in a socially effective situation.”Footnote 110