Introduction

After the remarkable year of 2020, during which New Zealand (hereafter used interchangeably with Aotearoa) successfully adopted a COVID-19 elimination strategy, and consequently elected the first single-party majority government since the introduction of the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system in 1996, politics in Aotearoa in 2021 involved fewer major political events. The year was notable for the new Labour government's attempts to make progress on elements of its reform agenda in health, housing, water and some social areas. However, policy reforms had to be balanced with the continuing demands of managing the response to the ongoing pandemic, including the vaccine roll-out, especially with the long-term viability of the elimination strategy looking increasingly uncertain. The tight regulation of the border as part of the country's COVID-19 response, emerging debates about vaccination mandates and public weariness with lockdowns all contributed to the first signs of discontent with, and protest actions against, the government's COVID-19 policies.

Election report

There were no major elections in New Zealand in 2021.

Cabinet report

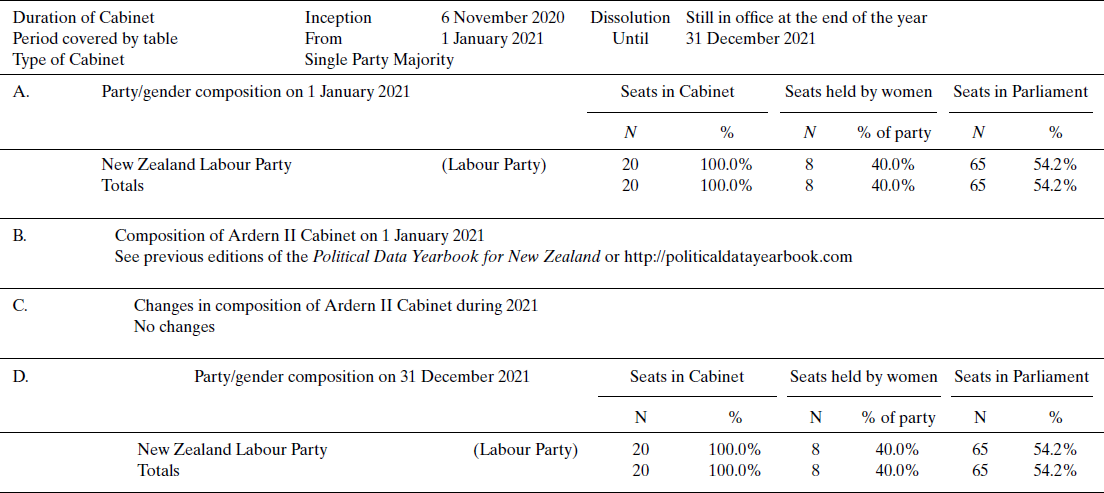

The Labour Party single-party majority government formed after the 2020 General Election occupied all seats around the Cabinet table and the composition of the Cabinet remained unchanged throughout 2021. It is important to recall, however, that under the Labour–Green Party Cooperation Agreement the two co-leaders of the Green became ministers outside Cabinet – James Shaw as Minister of Climate Change and Associate Minister for the Environment (Biodiversity), and Marama Davidson as Minister for the Prevention of Family and Sexual Violence and Associate Minister of Housing (Homelessness) (Table 1). The Cooperation Agreement allowed the Green ministers significant scope for voicing disagreement and noting where Cabinet decisions deviated from Green policy, even as they were bound by collective responsibility to implement these decisions in their portfolio areas (NZ Labour Party and Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand 2020).

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Ardern II in New Zealand in 2021

Note: The Cabinet does not include Green ministers and there are no formal coalition agreements between Labour and the Greens, which, however, share executive power.

Source: Department of Cabinet and Prime Minister (2022), https://dpmc.govt.nz/our-business-units/cabinet-office/ministers-and-their-portfolios/ministerial-list.

Parliament report

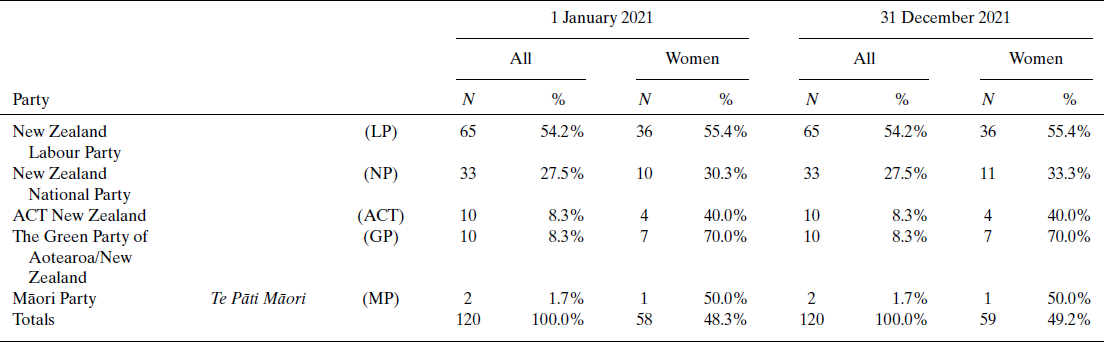

Parliament was also stable in this first full year of the 2020–23 legislative term, with just one change of note (Table 2). National Party MP Nick Smith resigned his seat on 10 June 2021, ending an almost 31-year parliamentary career. Smith, who had lost his electorate at the 2020 election and entered Parliament as a List MP, resigned after being erroneously advised that details of a Parliamentary Services inquiry into bullying allegations against him had been leaked to the media and would be made public (Trevett Reference Trevett2021). Smith was replaced two days later by the next candidate on the National Party list, Harete Hipango, who had previously served as MP for Whanganui (2017–20).

Table 2. Party and gender composition of Parliament (House of Representatives) in New Zealand in 2021

Source: New Zealand Parliament (2022), https://www.parliament.nz/en/mps-and-electorates/members-of-parliament.

The functioning of Parliament continued to adapt to the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. During a nationwide Alert Level 4 lockdown in August 2021, the government suspended Parliament's sitting for one week. In contrast to 2020, when a bespoke Epidemic Response Committee was established, in 2021 regular Select Committees continued to meet online. Given the suspension of the usual opportunities for scrutiny of the Executive via Question Time, the Prime Minister directed ministers to make themselves available to Select Committees. However, while the decision to suspend Parliament followed advice from the Director-General of Health, opposition political parties nonetheless criticized the move, arguing that without the return of the Epidemic Response Committee it constituted an ‘overreach of power’ (RNZ, 2021a). Following the short suspension, Parliament resumed, after ACT and National rejected a proposal to run Parliament virtually. However, for a time Parliamentary sessions were adapted with the agreement of the Business Committee of the House – rules requiring a certain number of MPs to be present were waived and a maximum of 10 (out of the usual 120) MPs were allowed in the House at any one time (Cooke Reference Cooke2021).

Political party report

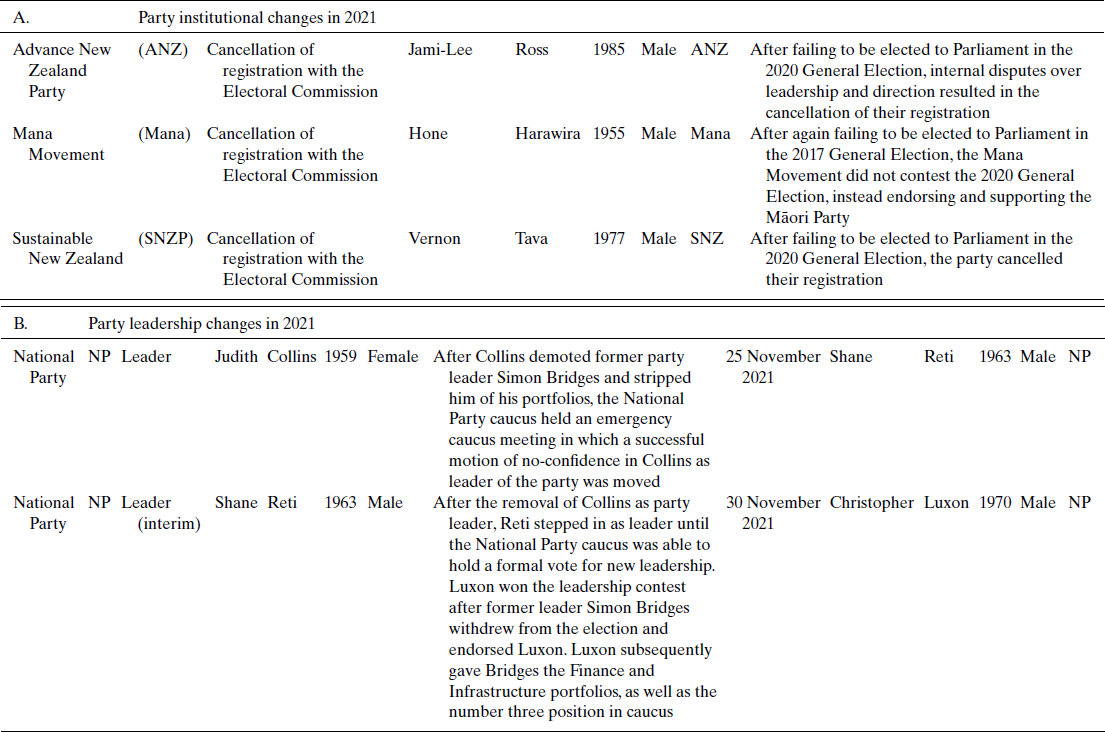

After its tumultuous year in 2020, which saw, before the General Election, two leadership changes in the space of two months, the National Party continued to experience instability during 2021. An internal review into the party's disastrous results in the 2020 election reportedly showed multiple failings in leadership and candidate selection practices, commitment to diversity, campaign messaging, and functioning of the party board (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2021). Nonetheless, long-time National Party President Peter Goodfellow was re-elected to the position in 2021.

The party's political leadership was less resilient. On 25 November, Judith Collins, who had herself replaced the previous leader a little more than a year prior, was removed as leader of the National Party. Throughout 2021, Collins faced persistently low opinion poll results for the party and in the preferred Prime Minister ratings, as well as criticism for her performance. Her removal was precipitated by an example of her sometimes unpredictable behaviour. After her sudden late-night demotion of senior National Party MP and former leader Simon Bridges for apparently spurious reasons related to an ill-advised comment made to a colleague many years prior, which had been addressed at the time, the National caucus quickly passed a vote of no confidence in Collins's leadership (Patterson Reference Patterson2021). Following a short period during which her deputy, Shane Reti, was acting leader, on 30 November 2021 Christopher Luxon was elected leader and Nicola Willis as deputy leader. Luxon, an evangelical Christian and well known for his previous role as chief executive officer (CEO) of Air New Zealand, was a newcomer to politics; he first entered Parliament (as MP for the safe National electorate of Botany) only at the 2020 General Election. However, even before his election to Parliament, he had been touted as a future party leader, in the style of former leader and Prime Minister (2008–16) John Key. Luxon became the fifth National Party leader in the space of four years. No other parties represented in Parliament experienced leadership changes in 2021.

During 2021 three minor political parties, none of which had been elected to Parliament in 2020, requested that their registration with the Electoral Commission be cancelled. One of these parties was Advance New Zealand (ANZ), the COVID-19 conspiracy party that brought together disgraced former National MP Jami-Lee Ross and guitarist Billy Te Kahika Jr in the lead up to the 2020 election.

For data on changes in political parties, see Table 3.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in New Zealand in 2021

Note: Reti was Collins’ deputy, and was interim leader.

Institutional change report

One significant reform launched in 2021 by Minister of Local Government Nanaia Mahuta affected electoral institutions at the level of local government. On 24 February, the Local Electoral (Māori Wards and Māori Constituencies) Amendment Bill was passed by Parliament, under urgency, with the support of the Green Party and Te Pāti Māori (Scotcher Reference Scotcher2021). A 2002 law had previously empowered local authorities to establish Māori wards (constituencies), which would enable voters of Māori descent who were registered on the Māori electoral roll to directly elect representatives on regional and territorial authorities, in a similar way to the dedicated Māori representation provided by the Māori seats in New Zealand's Parliament. However, up until 2021 only three Māori wards existed around Aotearoa.

Many attempts to establish such dedicated Māori representation in local government had foundered due to ‘voter-veto’ power (Geddis Reference Geddis2021). Where 5 per cent of voters signed a petition requesting a referendum on any proposal to establish a Māori ward, a binding referendum had to be held and these, often carrying the will of the Pākehā (non-Māori) majority, generally blocked this dedicated indigenous representation at the local level. The 2021 Act provided a temporary measure enabling territorial authorities to establish Māori wards in time for the 2022 local government elections by removing the ‘voter-veto’ and ignoring any prior local referendum results on the matter (Mahuta Reference Mahuta2021). In total, 35 councils established Māori wards ahead of the 2022 local body elections. This law, with its focus on the representation of Māori in local government, fed into ongoing, and at times acrimonious, debate in Aotearoa about the rights Māori should exercise in the country's system of representation and governance by virtue of their status as Tangata Whenua (People of the land).

Issues in national politics

If 2020 was the year of the COVID-19 elimination strategy, 2021 was, according to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, the year of the vaccine rollout (Ardern Reference Ardern2021). It was also the year that saw an awkward transition away from elimination as the primary tool in the pandemic response towards a suppression strategy. Over the course of 2021, a range of tools to manage the pandemic was deployed, including mandatory isolation, contact tracing, pre-departure testing for travellers, saliva/RAT testing, mask use, vaccinations, vaccine passes and vaccine mandates. The year began without community transmission and a Trans-Tasman Quarantine Free Travel Bubble with Australia was launched. However, the periodic recurrence of new COVID-19 cases led to repeated Alert Level changes and regional lockdowns, and the termination of the travel bubble.

Medsafe, the country's medicine regulator, gave provisional approval to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine on 3 February (Ardern Reference Ardern2021), paving the way for the launch of the largest immunization programme in the country's history. A phased approach was taken to the vaccine rollout, beginning with border workers, health workers and the elderly, before eventually offering the vaccine to everyone over the age of 12 years.

A prolonged outbreak of the Delta variant in mid-August reminded New Zealanders that vaccines would not automatically lead to a return to normality. On 17 August the Prime Minister placed the whole country into an Alert Level 4 lockdown for seven days. While most regions moved to Alert Level 3 and then Level 2 by 7 September, the Auckland region remained in a strict lockdown until 21 September. The much longer time that residents of New Zealand's largest city spent in lockdown began to take its toll and public weariness with the use of lockdowns as a COVID-19 management strategy was evident.

Stalling vaccination rates were a barrier to the desired move away from the use of lockdowns. Large-scale immunization campaigns were therefore launched, including a ‘Super Saturday Vaxathon’ in October that saw around 2.5 per cent of the population (130,000 people) vaccinated in a single day at events organized by health authorities, sports clubs, religious organizations, gangs and other community groups around the country, accompanied by day-long coverage on major television networks (RNZ 2021b). After several months of the campaign, in mid-December the government was able to celebrate reaching the target of 90 per cent of New Zealanders aged 12 years and over being fully vaccinated (Pearse et al. Reference Pearse, Tan and Tapaleao2021). Concerns remained, however, about delays in acquiring vaccines and about inequity in the vaccine rollout. In particular, lower rates of vaccination among Māori meant parts of the country were more vulnerable to the risks of COVID-19 spread.

A contentious aspect of the vaccine programme in the second half of 2021 was the introduction of vaccine mandates and certificates (My Vaccine Pass) in many employment and community settings, notably in jobs at the border, and in healthcare, education, police, military and in the prison system. The vaccine rollout and mandates were unsuccessfully challenged in High Court cases in 2021 and the government pressed ahead with its objectives. The replacement, in December, of the Alert Level System with the new COVID-19 Protection Framework (dubbed the ‘Traffic Light System’) meant the ability to run and participate in business and community activities could vary depending on local vaccination rates, use of vaccine certificates and mask-wearing requirements.

While there was generally high support for vaccines and compliance with mask rules in 2021, emerging disquiet about the lockdowns and vaccine mandates received significant media attention. Opposition solidified around a few figures in the small but vocal anti-vax movement, which further highlighted the fraying of the national consensus that had underpinned the pandemic response in 2020. Nascent protests also drew in rural groups (e.g., Groundswell) protesting the government's water, climate change and vehicle emissions policies, religious groups opposing social reforms such as the liberalization of abortion, and fringe, internationally inspired anti-state groups pushing COVID-19 and other conspiracy theories (e.g., QAnon, 5G). Building on anti-lockdown protests organized by the new Freedom and Rights Coalition in Auckland in October, a significant protest took place outside Parliament in November ‘ostensibly’ to protest vaccine mandates, but ‘in reality the signs and shouts illustrated a heady potpourri of issues’ (Smith Reference Smith2021). These protests began to find a growing audience and a much more disruptive protest and occupation of Parliament grounds was to come in early 2022.

An additional challenge for the government throughout 2021 was the growing challenge of maintaining essentially closed borders in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The economic ramifications of the border regime were especially significant for the tourism, hospitality and international education sectors, as well as for industries suffering labour shortages. Beyond these economic impacts, the requirement that all those entering spend 14 days in Managed Isolation and Quarantine facilities (MIQ) sparked growing and, at times, vitriolic debate about whether New Zealanders were adequately able to exercise their citizenship right to enter the country. With demand for MIQ rooms consistently far outstripping supply, a new ‘virtual lobby’ system for allocating travellers to rooms was rolled out on 20 September. This did little to ease pressure on the system; at its peak, a queue of over 30,000 in the ‘virtual lobby’ attempted to secure MIQ vouchers in the first release of just 3000 rooms (MIQ 2021). Anger was high among New Zealanders abroad who felt locked out of their own country, and groups such as Grounded Kiwis were formed to lobby and challenge the government's MIQ policies.

Immigrants without residency status also faced severe challenges. Those stranded outside New Zealand experienced separation from their jobs and sometimes families, while thousands of immigrants inside New Zealand lived with uncertain status, given a policy in flux and major processing backlogs at Immigration New Zealand. In the face of growing numbers of skilled immigrants leaving Aotearoa due to their unresolved immigration status, and at a time of significant labour shortages, on 30 September Minister of Immigration Kris Faafoi finally announced a one-off 2021 Resident Visa. Around 165,000 migrants and family members holding a range of work-related visas qualified for this residency visa, provided they had lived in New Zealand throughout the pandemic, were in the country when the visa was announced and earned above the median wage or worked in areas of occupational shortages (Faafoi Reference Faafoi2021).

While pandemic management continued to dominate the day-to-day political agenda, during 2021 Jacinda Ardern's government sought to make progress on major policy reforms. In health, the government announced that it would disband the existing 20 locally controlled district health boards and replace them with a single agency, Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora), to reduce discrepancies in care and system performance across regions. Alongside it, a national Māori Health Authority (Te Aka Whai Ora) was planned to take responsibility for improving Māori health outcomes and providing health services from a Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview) perspective (Quinn Reference Quinn2021).

In the area of local government and infrastructure, the government pressed ahead with its previously announced Three Waters Reform Programme that sought to address historical under-investment in ageing water infrastructure that had resulted in recent problems of water contamination, low-quality drinking water and sewage overflows. The reform proposed four nationwide public entities to govern and regulate the ‘three waters’ of drinking water, wastewater and storm water, with the stated goal of increasing investment in water infrastructure and improving water quality. While existing water entities would technically remain in local government ownership, decision-making would be mostly taken over by the four entities, with these governance bodies including mana whenua (local tribal) representatives in decision-making roles. Touted by the government as ensuring better coordination, economies of scale and improved outcomes, the centralizing thrust of both health and water reforms was nonetheless strongly criticized by opponents as removing local control of local affairs.

The fact that ‘co-governance’ mechanisms, which supported enhanced Māori decision-making power and self-determination, were associated with these projects sparked significant pushback from the Opposition in Parliament and from interests in local government. Around the same time, the National Party and ACT were also mounting opposition to a report, He Puapua, commissioned by the Labour-led government during the previous parliamentary term to advise on a plan to meet the aims of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The report, which proposed expanding the currently small area of Māori governance over ‘people and places’ to achieve stronger self-determination (rangatiratanga) and strengthening co-governance between Māori and the government in areas such as health, education, criminal justice and the political system (O'Sullivan Reference O'Sullivan2021), was seized on by National and ACT as representing a ‘separatist’ or ‘racist’ agenda (Johnson Reference Johnson2021). While He Puapua did not represent government policy, and indeed the government sought to distance itself from many of the proposals, the publicization of this report, alongside organizational and policy reforms that did make provision for greater Māori autonomy in policymaking and implementation, enabled Opposition parties to construct a counter-narrative. The government, while taking some steps forward in the space of indigenous self-determination, seemed unwilling throughout 2021 to take a narrative lead on reforms such as the Māori Health Authority or Three Waters, which opened up space for attack and fearmongering.

In addition to reforms in health and water, the government increased its efforts to tackle the housing affordability crisis by reforming aspects of the Resource Management Act, establishing a NZ$3.8 billion housing acceleration fund, and passing legislation (with the support of the National Party) that required local councils to facilitate the intensification of housing in urban and suburban areas, notably around public transport corridors.

Less controversial were significant moves in various areas of social policy, including the establishment of a Ministry for Disabled Peoples and a Ministry for Ethnic Affairs, and the government's landmark apology for the Dawn Raids, a dark period of New Zealand's history in the 1970s that involved the arrest and deportation of immigrants from the Pacific Islands. Fulfilling a 2020 election promise, the government announced the dates for the new public holiday of Matariki, which marks the start of the Māori new year as the Matariki star cluster (also known as Pleiades) rises, and work continued on changes to the Aotearoa New Zealand Histories curriculum to expand the teaching of the country's history in schools. LGBTQIA+ rights were further progressed with the passage of a gender self-identification law and the introduction of a Bill to ban conversion therapy, while work continued on labour rights, including an increase in the minimum sick leave entitlement to 10 days from July 2021, further increases in the minimum wage and assurance of a living wage for government contractors.

To conclude, despite the passage of some important pieces of legislation that moved forward its progressive social agenda, the inability of the Labour government to get early buy-in for several of its major policy reforms, notably Three Waters and responses to climate change (including transport), signalled choppy waters ahead for the government. The economy continued to show resilience in the face of pandemic-driven international instability, decimated tourism and international education sectors, and disruption to key sectors (such as construction) due to major supply-chain problems. However, the waning public support for the ‘go hard, go early’ approach of the early pandemic response, growing impatience with masking and vaccine rules, and uncertainty about when the country's border would open fully, meant not only that the path to ‘normal’ post-pandemic life was unclear, but also that the previous extraordinary levels of support for Jacinda Ardern and her government started to decline.

Acknowledgments

Open access publishing facilitated by Victoria University of Wellington, as part of the Wiley - Victoria University of Wellington agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.