Introduction

The democratic character of voluntary organizations in Norway (and Scandinavia) is highly valued for providing members from all social backgrounds opportunities to participate in governance and acquire democratic competencies. Board volunteering is particularly important, as it ensures direct representation of members (Reference Torpe, Ferrer-Fons, Maloney and RoßteutscherTorpe & Ferrer-Fons, 2007). Yet this model is challenged by rising social inequality in society and managerialization within voluntary organizations (Reference Steen-Johnsen, Enjolras, Wijkström and ZimmerSteen-Johnsen & Enjolras, 2011). Although most voluntary organizations maintain democratic structures (Reference Elstad and LadegårdElstad & Ladegård, 2009; Reference Grendstad, Selle, Stromsnes and BortneGrendstad et al., 2006), socioeconomic differences in participation have become more pronounced (Reference EimhjellenEimhjellen, 2023; Reference Eimhjellen and FladmoeEimhjellen & Fladmoe, 2020). These trends raise concerns about a democratic deficit, as voluntary organizations may less often serve as “schools in democracy” that provide opportunities for member influence.

Existing research on social inequality in volunteering has been guided by a resource-theory model that emphasizes individuals' economic, cultural, and social resources as explanatory factors (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007). While still important, this model has come under scrutiny for overlooking how volunteering in post-industrial societies is stratified by social hierarchies and organizational dynamics that privilege middle-class forms of participation (Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and ShacharHustinx et al., 2022). In this article, we argue for social class analysis as an alternative approach that can move beyond resources alone by analyzing volunteering as embedded in social class (see e.g., Andersen & Reference Andersen and BakkenBakken, 2019; Reference EimhjellenEimhjellen, 2023; Reference van den Bogaard, Henkens and Kalmijnvan den Bogaard et al., 2014). Unlike resource theory, which explains participation through the accumulation of resources, a class perspective emphasizes relational positions in systems of stratification. In particular, an occupation-based class analysis provides a potentially useful lens for analyzing board volunteering, as recruitment hinges on skills and expertise that are linked to employment relations that determine class positions.

What makes Norway a particularly compelling context for examining social class in board volunteering is the tension between a tradition of member participation in governance and administrative demands for specialized expertise among board members as organizations seek to navigate complex institutional environments (Reference Sivesind, Arnesen, Gulbrandsen, Nordø, Enjolras, Enjolras and StrømsnesSivesind et al., 2018; Reference Steen-Johnsen, Enjolras, Wijkström and ZimmerSteen-Johnsen & Enjolras, 2011). Boards are key arenas for member representation, and there is a norm that members take turns serving (Reference WoxholthWoxholt, 2020), meaning that the threshold for participation traditionally has been low in line with an egalitarian culture (Reference Torpe, Ferrer-Fons, Maloney and RoßteutscherTorpe & Ferrer-Fons, 2007). At the same time, heightened demands for expertise imply that the configuration of skills and resources, and not only the volume, is important for recruitment to boards. A social class approach is apt to evaluate this expectation, as it can capture aspects that influence board volunteers’ eligibility and motivation, for instance, administrative expertise, ties to politics and business, and work autonomy and flexibility. As such, it can complement a resource-theory-based approach to board volunteering. Against this backdrop, the article addresses two questions: (1) How does class position influence board volunteering? (2) To what extent are class differences explained by individuals’ economic, social, and cultural resources?

We use data from a comprehensive, nationally representative population survey on volunteering conducted in Norway in 2019. Social class is operationalized using the Oesch (Reference Oesch2006) occupational social class scheme, based on data regarding individuals’ occupation and employment relations. This scheme differentiates social classes along a vertical lower-to-upper dimension that reflects the volume of individual resources and along a horizontal dimension according to the skill-based work logics of distinct types of occupations. We use data on income, education, social relations, and personal trust to control for economic, cultural, and social resources. We find that board volunteering varies not only between higher-level and lower-level class positions but also horizontally according to whether positions entail technical, managerial, or sociocultural work logics, and that these class differences are only partly accounted for by individuals’ economic, cultural, and social resources.

Explaining Social Inequality in Nonprofit Governance: The Resource-Theory Model

Boards of voluntary and nonprofit organizations differ from those of public and market sector institutions. Anheier (Reference Anheier2005, p. 182) notes that “nonprofits are primarily accountable to their members who vest operational control into the governing board of the organization.” Members are the primary stakeholders of the organizations, but the elected board with its chairperson forms the core (Reference Heitmann, Selle, Grønlie and ReveHeitmann & Selle, 1993). Serving on the board of a voluntary organization represents a distinct form of volunteering that involves a more active role and greater obligations than regular membership. Boards have many responsibilities, including financial oversight, organizational planning, and supporting the management. Their primary duty is to ensure that the organization fulfills its agreed-upon mission (Reference Kumar and NunanKumar & Nunan, 2002). Board members also help build trust with external stakeholders, including funders, donors, collaborating organizations, and service recipients (Reference Renz, Brown and AnderssonRenz et al., 2023). Because board seats are limited, selection mechanisms are stronger than for volunteering in general and may bear similarities to those found in the labor market (Reference Handy and MookHandy & Mook, 2011).

Research on social inequality in volunteering has traditionally been grounded in the resource-theory model. This model holds that the propensity to volunteer varies with individuals’ economic, cultural, and social resources, including income, education, networks, and social status (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007). These resources align with dominant status positions that can be leveraged by individuals to gain advantages (Reference SmithSmith, 1994). For example, those with substantial economic resources can donate money to enhance their visibility, prestige, and influence, paving the way to board positions. Cultural resources can bolster credibility and perceived qualifications for board membership and are associated with a greater fluency in norms, values, and language used in a board setting. From an organizational perspective, having competent, experienced, and well-connected board members matters internally for performance and externally for building support and securing funding (Reference Abzug and GalaskiewiczAbzug & Galaskiewicz, 2001; Reference GulbrandsenGulbrandsen, 2020; Reference Moore, Sobieraj, Whitt, Mayorova and BeaulieuMoore et al., 2002).

Although the resource-theory model has yielded valuable and well-tested insights into social inequality in volunteering (see e.g. Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007; Reference WilsonWilson, 2012), it has recently faced criticisms for contributing to a relative stagnation as “research in this tradition continuously reconfirms the relationship between individual resources and volunteering as an empirical regularity” (Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and ShacharHustinx et al., 2022). A central concern is the model's limited dynamism, which may obscure how changes in socioeconomic structures and differences across national contexts reshape the link between social inequality and volunteering. Importantly, the resource-theory model may not fully account for how the vertically and horizontally differentiated socioeconomic structure of post-industrial society relates to organizational governance. In a knowledge-intensive economy, a premium is placed on configurations of organizational and sociocultural knowledge, skills, and experience as well as social connections (Reference BellBell, 1973). Voluntary organizations, like public and market actors, depend on combinations of such resources to navigate their environments (Reference Steen-Johnsen, Enjolras, Wijkström and ZimmerSteen-Johnsen & Enjolras, 2011). Moreover, labor market conditions and the nature of authority relations affect individuals’ security, flexibility, and motivations (Reference GoldthorpeGoldthorpe, 2000), shaping their opportunities and willingness to participate in voluntary organizations. This brings attention to the need for alternative or complementary approaches to the resource-theory model.

A Social Class Approach to Nonprofit Governance: The Occupational Class Scheme

While social class approaches are commonly used in the social sciences as a multi-dimensional account of inequality (Reference SavageSavage, 2015), they are notably absent from much volunteering research. Although labor market relations that underlie class positions may seem unrelated to volunteering, the distinctions and hierarchies they produce entail “relative social disadvantage” (Reference Connelly, Gayle and LambertConnelly et al., 2016), reflecting not only economic circumstances but also cultural factors and social relations. Importantly, social class captures the interplay of socioeconomic attributes known to influence volunteering (Reference Chan, Birkelund, Aas and WiborgChan et al., 2011). Although not widespread in volunteering research, social class analysis has shown its relevance. Andersen and Bakken (Reference Andersen and Bakken2019) find class effects in youths’ participation in organized sports in Norway using an occupational scheme that measures parents’ social class position. van den Bogaard et al. (Reference van den Bogaard, Henkens and Kalmijn2014) demonstrate that retirees’ former occupational status influences their likelihood of volunteering during retirement. With respect to board volunteering, an occupational social class approach is particularly pertinent because it highlights how class positions are associated with technical, managerial, and sociocultural expertise that is valued by voluntary organizations and that may be advantageous for individuals in securing board positions.

In their occupational social class approach, Erikson et al. (Reference Erikson, Goldthorpe and Portocarero1979) define social class along two dimensions: employment status and the regulation of employment relations. First, they differentiate employers, the self-employed, and employees. Then, employees are distinguished with regard to the degree of autonomy, authority, and security that their position offers, more specifically whether their work is regulated according to ‘the labor contract’ or ‘a service relationship’ (Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson & Goldthorpe, 1992). The labor contract is typical of occupations where workers are easily replaceable and entails tightly regulated employment and payment arrangements, close monitoring and supervision, and absence of long-term provisions and benefits. In contrast, a service relationship is typical for occupations requiring expertise and skills that are hard to monitor. Such occupations involve exchanging long-term commitment for employer trust, offer incremental advancements, and provide greater employment security (Reference GoldthorpeGoldthorpe, 2000).

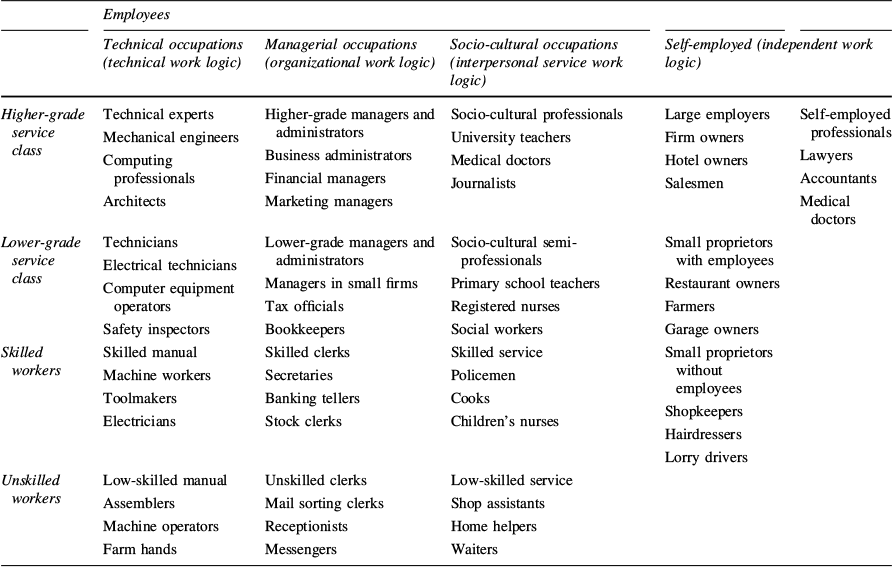

Based on this, a class scheme is outlined comprising higher and lower service classes of managers and professionals; intermediate positions comprising routine non-manual positions and lower-grade technical and supervisory positions; and skilled and unskilled working classes, in addition to the self-employed (e.g., small business-owners and farmers) (Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson & Goldthorpe, 1992). Oesch (Reference Oesch2003, Reference Oesch2006) has sought to adapt this scheme to contemporary European labor markets by adding distinctions within the service classes based on work logics, namely technical, organizational, and interpersonal. The premise is that authority relations, primary orientations, and skill requirements vary with “whether an occupation involves the deployment of technical expertise and craft, the administration of organizational power or face-to-face attendance to people's personal demands” (Reference OeschOesch, 2006, p. 267). This yields a cross-cutting distinction between technical, managerial, and socio-cultural occupations, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 The occupational class scheme (based on Oesch, Reference Oesch2006)

Employees |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Technical occupations (technical work logic) |

Managerial occupations (organizational work logic) |

Socio-cultural occupations (interpersonal service work logic) |

Self-employed (independent work logic) |

||

Higher-grade service class |

Technical experts Mechanical engineers Computing professionals Architects |

Higher-grade managers and administrators Business administrators Financial managers Marketing managers |

Socio-cultural professionals University teachers Medical doctors Journalists |

Large employers Firm owners Hotel owners Salesmen |

Self-employed professionals Lawyers Accountants Medical doctors |

Lower-grade service class |

Technicians Electrical technicians Computer equipment operators Safety inspectors |

Lower-grade managers and administrators Managers in small firms Tax officials Bookkeepers |

Socio-cultural semi-professionals Primary school teachers Registered nurses Social workers |

Small proprietors with employees Restaurant owners Farmers Garage owners |

|

Skilled workers |

Skilled manual Machine workers Toolmakers Electricians |

Skilled clerks Secretaries Banking tellers Stock clerks |

Skilled service Policemen Cooks Children's nurses |

Small proprietors without employees Shopkeepers Hairdressers Lorry drivers |

|

Unskilled workers |

Low-skilled manual Assemblers Machine operators Farm hands |

Unskilled clerks Mail sorting clerks Receptionists Messengers |

Low-skilled service Shop assistants Home helpers Waiters |

||

This occupational class scheme integrates individuals’ work-related status with economic, cultural, and social resources, as well as preferences and motivations, to explain social outcomes—such as a board volunteering. First, a person's class position can influence his or her financial security and flexibility. Although the relationship between free time and volunteering is not straightforward (Reference Einolf and ChambréEinolf & Chambré, 2011), those in service class positions enjoy greater autonomy, authority, and security at work, which affords the flexibility required for time-intensive board volunteering. One's authority at work may also translate into a willingness to assume leadership roles in voluntary organizations. By contrast, those in working class positions often face demanding schedules or have multiple jobs, reducing their availability and motivation to volunteer. Even where symbolic compensation is offered, the return may be insufficient to make board volunteering a viable use of their time. Retirees and those outside the labor market are a partial exception, as board responsibilities can substitute for work activities (Reference Walton, Clerkin, Christensen, Paarlberg, Nesbit and TschirhartWalton et al., 2017).

Second, service class occupations are likely to be linked to knowledge and skills in demand by voluntary organizations, such as legal or financial expertise. Board volunteering gives individuals in these positions opportunities to use formal education and practical experience and to develop their expertise beyond the work setting. They may also have greater confidence in their abilities to take on board responsibilities (Reference Janoski and WilsonJanoski & Wilson, 1995). By contrast, individuals in working class positions may be dissuaded from board volunteering because the work is unfamiliar, and their practical skills are less directly transferable. Volunteering habits are often socialized through cultural practices, which are embedded class-specific values, preferences, and interests. In addition, individuals in service class positions tend to have larger and more diverse social networks (Reference Pichler and WallacePichler & Wallace, 2009), which provide better opportunities to obtain board positions through weak as well as strong ties (Reference GranovetterGranovetter, 1973). Recruitment into voluntary activities is known to depend on networks and perceived trustworthiness (Reference BekkersBekkers, 2005; Reference SmithSmith, 1994; Reference Wilson and MusickWilson & Musick, 1998). Social differences in board volunteering are potentially reproduced when new board members are recruited within the existing members’ networks.

For board volunteering, occupational status may be a stronger determinant than for volunteering in general, given the link between paid work and board tasks. Although many studies have examined the role of occupational status (Reference Abzug and GalaskiewiczAbzug & Galaskiewicz, 2001; Reference Abzug and SimonoffAbzug & Simonoff, 2004; Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007; Reference Tschirhart, Reed, Freeman and AnkerTschirhart et al., 2009; Reference Walton, Clerkin, Christensen, Paarlberg, Nesbit and TschirhartWalton et al., 2017), it is often treated as distinct from individuals' socioeconomic resources. An occupational class scheme highlights this link through vertical and horizontal variations: configurations of resources, skills, and motivations differ between classes and occupations. Abzug and Galaskiewicz (Reference Abzug and Galaskiewicz2001) find that managers and professionals are significantly better represented on nonprofit boards in the United States. Higher and lower-grade managers and administrators may benefit from, and be motivated by, experience in strategic decision-making, fiscal management, and organizational leadership. Financial and administrative expertise associated with such occupations is likely to be valued in a board setting. Socio-cultural professionals and semi-professionals, in turn, may offer expertise on community needs and be motivated by mission alignment, particularly in organizations related to culture and arts, education, health, and social issues. By contrast, the skills of technical experts and technicians may be directly less transferable and less sought after as board members or personally motivated to volunteer.

In summary, we argue that one's placement on the vertical axis plays a role, so we assume that those in higher class positions will be more likely to volunteer on boards than those in lower positions. However, the relationship between social class and board volunteering may be less straightforward than simply varying between the service and working classes. The different configurations of individual resources associated with various class positions, as captured on the horizontal axis, may produce effects that cut across the hierarchical class structure. Among the service classes, we expect that higher-grade managers and administrators, as well as socio-cultural professionals like university teachers, nurses, and social workers, to be more likely to volunteer compared to those in technical occupations.

Norway: Board Volunteering in a Post-Industrial Yet Egalitarian Context

Democratic involvement is a defining feature of the member-based voluntary organizations that form the core of the voluntary sector in Norway (and Scandinavia) (Sivesind et al., Reference Sivesind, Arnesen, Gulbrandsen, Nordø, Enjolras, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). Members’ democratic rights are set out in organizational statutes and an unwritten law of associations and typically include the right to stand for election to governance roles, participate in member meetings and activities, and attend and vote at annual general meetings (Reference WoxholthWoxholth, 1998, Reference Woxholth2020). Board volunteering is essential, as members are expected to take their turn in governance, and some Norwegian organizations have statutes requiring boards to represent specific organizational subdivisions, geographical regions, or social quotas (e.g., a certain share of women). Broad participation is also valued because it fosters democratic norms and competencies (Reference Torpe, Ferrer-Fons, Maloney and RoßteutscherTorpe & Ferrer-Fons, 2007). This contrasts with countries where the sector is dominated by more professional organizations, such as philanthropic foundations or nonprofit service providers, and where the focus is on services produced or funds distributed in line with legal requirements, statutes, and external stakeholders’ expectations (Reference CornforthCornforth, 2003; Reference Van Puyvelde, Caers, Du Bois and JegersVan Puyvelde et al., 2016).

However, in recent decades, the Norwegian voluntary sector has shifted towards a more administratively complex and professionalized management model (Reference Steen-Johnsen, Enjolras, Wijkström and ZimmerSteen-Johnsen & Enjolras, 2011). Many organizations face heightened external demands that necessitate more strategic thinking about board composition. To navigate their environments, maintain legitimacy, and secure funding, organizations increasingly rely on board members with transferrable qualifications, experience, and networks from politics and business. At the same time, social disparities have become apparent in Norwegian society, although much of the egalitarian character that it is known for remains (Reference Barth, Moene, Pedersen, Fischer and StraussBarth et al., 2021). This is seen also in the voluntary sector, where studies show that volunteers more often belong to higher socioeconomic strata compared to non-volunteers, a pattern that also applies to board volunteering (Reference EimhjellenEimhjellen, 2023; Reference Qvist, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen, Strømsnes and SvedbergQvist et al., 2019). This echoes the international literature, which indicates that board volunteers tend to have higher socioeconomic status and come from more prestigious professional backgrounds (Reference Abzug and GalaskiewiczAbzug & Galaskiewicz, 2001; Reference Abzug and SimonoffAbzug & Simonoff, 2004; Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007; Reference Tschirhart, Reed, Freeman and AnkerTschirhart et al., 2009; Reference Walton, Clerkin, Christensen, Paarlberg, Nesbit and TschirhartWalton et al., 2017).

In the Norwegian context, evidence suggests that social differences in board volunteering are not explained solely by the volume of economic and cultural resources, but also by its composition (Reference EimhjellenEimhjellen, 2023). Broad member rights and norms of participation lower formal barriers and widen the pool of eligible volunteers, but increased administrative demands introduce competence thresholds that may privilege certain configurations of skills that are more unequally distributed in the population (e.g., administrative and financial literacies, network ties to politics and business, and work autonomy and flexibility). The tensions between these developments make Norway a compelling case for a social class analysis of board volunteering. Although those configurations relate to economic, social, and cultural resources, class positions as defined by employment relations and work logics may better capture how “bundling” of skills, resources, and expertise affects who volunteers on boards and who does not.

Data and Methods

The analysis is based on a nationally representative survey on volunteering carried out among individuals between the ages of 18 and 79 living in Norway in May 2019. Kantar TNS conducted the survey on behalf of the Centre for Research on Civil Society and Voluntary Sector at the Institute for Social Research in Oslo, Norway. Respondents were drawn from an online panel and completed an online questionnaire. The response rate was 44.9% with a net sample of 5153. In the net sample, there was a slight overrepresentation of women compared to men and individuals residing in the southern parts of Norway, and a larger overrepresentation of individuals with university and college education (Reference Eimhjellen and FladmoeEimhjellen & Fladmoe, 2020). Weights were calculated to correct for these biases.

Board Volunteering

Board volunteering is measured with a binary indicator of whether individuals engaged in board work in voluntary organizations. Following a question on whether respondents had volunteered for a voluntary organization, they were asked, “What kind of work have you done for voluntary organizations in the past 12 months?” Several activities were listed to the respondent, including “Board work.” Because such involvement typically presupposes board membership, we infer that those reporting board work held a formal seat on the board(s) of one or more organizations. The phrasing implies active participation, so the measure may not capture individuals who held board roles but were inactive, such as deputy board members or members of inactive organizations.

Social Class Position

Social class position is measured using the Oesch occupational class scheme (Reference OeschOesch, 2006), operationalized based on data on respondents’ occupation and employment status. Respondents were asked the name or title of their position in their main occupation, which they used to search a catalogue of pre-defined occupational titles based on the International Standard of Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) (see ILO, 2012). If a title was not specified, respondents described their occupation for post-survey coding. In the ISCO-08, each occupational title is designated an occupational code, which, combined with information on employment status (employed or self-employed), was used to construct a 12-level occupational class scheme using the Oesch Stata module (Kaiser, Reference Kaiser2018). The scheme distinguishes positions by employment status, regulation of employment relations, and technical, managerial, or socio-cultural work logics. The higher service classes comprise: (1) Technical experts, (2) Higher-grade managers and administrators, and (3) Socio-cultural professionals. The lower service classes comprise: (4) Technicians, (5) Lower-grade managers and administrators, and (6) Socio-cultural semi-professionals. Skilled workers comprise: (7) Skilled manual, (8) Skilled clerks, and (9) Skilled service. (10) Unskilled workers are not distinguished according to work logic in our application, in part due to a lower number of observations in this category. In addition, (11) The self-employed and (12) Others are included. The survey did not collect additional information on self-employment, so we were unable to differentiate between classes within this category (e.g., large employers, professionals, small proprietors, cf. Oesch (Reference Oesch2006)). The Others category encompasses retirees, welfare recipients, students, and others outside the labor market, for whom information on past or present occupation was not available. However, retirees with data on occupational code were given a class position.

Economic, Cultural, and Social Resources

To assess the social class approach relative to the resource-theory model, we include measures of economic, cultural, and social resources commonly used in studies of volunteering (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007). Economic resources are measured by respondents’ pre-tax household income. Respondents were asked to report their household income based on eight pre-defined categories in intervals of 199,999 Norwegian kroner, ranging from below 200,000 to 1.4 million and above. A limitation is that the data does not include information on capital income or assets, which also determine individuals’ overall economic situation. Cultural resources are measured using information on respondents’ highest achieved education level, field of education, and the number of books in the home. The first two variables are included to measure formal qualifications as they relate to specific fields of knowledge. Lower and higher education levels are represented by a binary variable distinguishing between lower/upper secondary school and university or college education. Field of education is a categorical variable that encompasses four main fields: (1) General education, (2) Arts and humanities, social sciences, and law, (3) Engineering, medicine, and natural sciences, and (4) Finance and service. The number of books in the home represents a measure of cultural resources as a form of (objectified) capital (Reference Sieben and LechnerSieben & Lechner, 2019). The variable comprises six categories: (0) no books, (1) 0–19 books, (2) 20–99 books, (3) 100–499 books, (4) 500–999 books, and (5) more than 1000 books.

Social resources are measured by the number of friends, social network resources, and interpersonal trust. Friends, acquaintances, and network ties are an important pathway into volunteering in general (Reference Wilson and MusickWilson & Musick, 1998), and even more so into board volunteering. Respondents were asked, “How many close friends do you have at present?”: (0) No friends, (1) 1–2 friends, (2) 3–5 friends, (4) 6–10 friends, and (5) 10 or more friends. Furthermore, social network resources are measured by binary variables based on questions on whether respondents’ circle of friends included persons that “are able to help you find work if it becomes necessary”, “are able to lend you a large sum of money”, and “have a leading position in business, the public administration or in politics”. Lastly, trust in others may influence the willingness to take on responsibilities for an organization's governance together with others in a board setting. Interpersonal trust was measured by asking, “On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 means that one cannot be careful enough and 10 means that most people are trustworthy. Do you think that you cannot be careful enough when dealing with others, or do you think that most people in general are trustworthy?” A caveat is that the social resource measures are partially endogenous to board volunteering. For example, having a large network not only helps channel people into board membership but may also be a consequence of board work.

Control Variables

In addition, we control for gender and age, as both characteristics are consistently associated with differences in volunteering and class. Women tend to be more likely to volunteer than men (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007), but men more often occupy senior and managerial positions (Reference Meyer and RamederMeyer & Rameder, 2022). Volunteering also tends to vary across the life course, typically increasing through mid-adulthood before declining in later life (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2007), and age is related to class position through changes in occupational status. These demographic patterns are thus important to account for to avoid conflating their effects with those of occupational class.

Descriptive Analysis

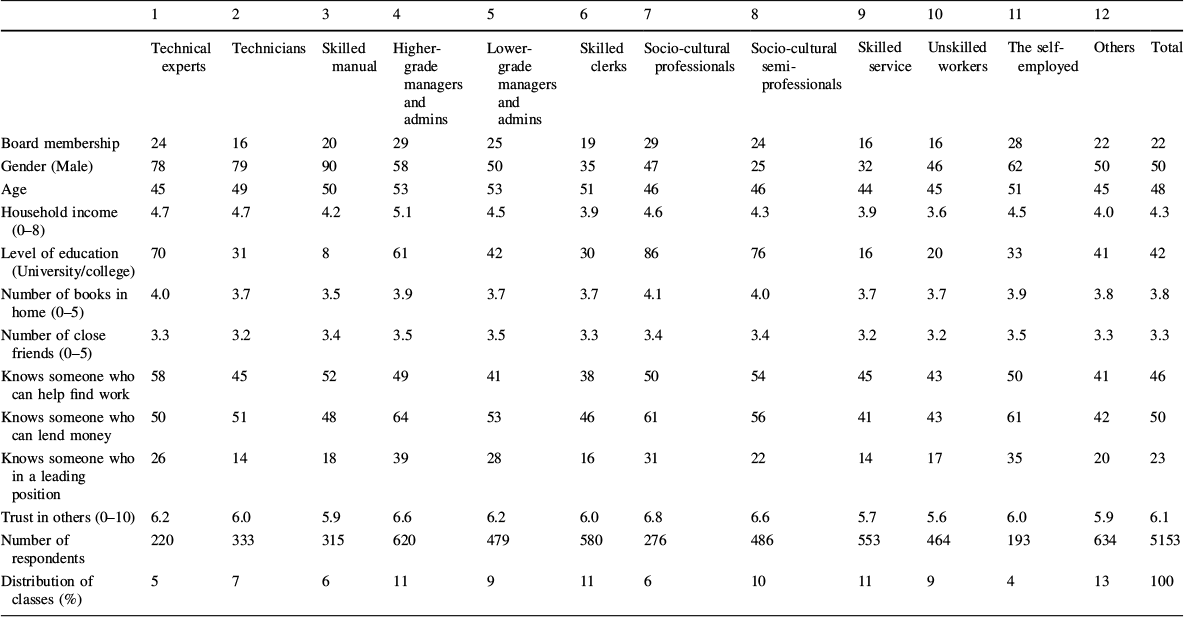

Table 2 reports the means or shares of key variables by social class position. As seen from the bottom of the table, a majority of the sample belongs to managerial and socio-cultural positions. Higher-grade managers and administrators, skilled clerks, and skilled service workers are the largest categories, closely followed by lower-grade managers and administrators, socio-cultural semi-professionals, and unskilled workers. However, the Others category (retirees, welfare recipients, students, and others outside the labor market) is the single largest group.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics. Means or shares of key variables, by social class position. Weighted

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Technical experts |

Technicians |

Skilled manual |

Higher-grade managers and admins |

Lower-grade managers and admins |

Skilled clerks |

Socio-cultural professionals |

Socio-cultural semi-professionals |

Skilled service |

Unskilled workers |

The self-employed |

Others |

Total |

|

Board membership |

24 |

16 |

20 |

29 |

25 |

19 |

29 |

24 |

16 |

16 |

28 |

22 |

22 |

Gender (Male) |

78 |

79 |

90 |

58 |

50 |

35 |

47 |

25 |

32 |

46 |

62 |

50 |

50 |

Age |

45 |

49 |

50 |

53 |

53 |

51 |

46 |

46 |

44 |

45 |

51 |

45 |

48 |

Household income (0–8) |

4.7 |

4.7 |

4.2 |

5.1 |

4.5 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

4.3 |

Level of education (University/college) |

70 |

31 |

8 |

61 |

42 |

30 |

86 |

76 |

16 |

20 |

33 |

41 |

42 |

Number of books in home (0–5) |

4.0 |

3.7 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

Number of close friends (0–5) |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

Knows someone who can help find work |

58 |

45 |

52 |

49 |

41 |

38 |

50 |

54 |

45 |

43 |

50 |

41 |

46 |

Knows someone who can lend money |

50 |

51 |

48 |

64 |

53 |

46 |

61 |

56 |

41 |

43 |

61 |

42 |

50 |

Knows someone who in a leading position |

26 |

14 |

18 |

39 |

28 |

16 |

31 |

22 |

14 |

17 |

35 |

20 |

23 |

Trust in others (0–10) |

6.2 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

6.6 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

6.8 |

6.6 |

5.7 |

5.6 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

Number of respondents |

220 |

333 |

315 |

620 |

479 |

580 |

276 |

486 |

553 |

464 |

193 |

634 |

5153 |

Distribution of classes (%) |

5 |

7 |

6 |

11 |

9 |

11 |

6 |

10 |

11 |

9 |

4 |

13 |

100 |

First, the table shows a social class gradient in board volunteering: the share rises from the lower working-class positions through the lower-grade to the higher-grade service class positions. For example, within socio-cultural occupations, 16 percent of skilled service workers volunteer, compared to 24 percent among socio-cultural semi-professionals and 29 percent among socio-cultural professionals. A similar pattern is seen within managerial occupations, but it diverges within technical occupations. The share is highest among technical experts (the higher-grade service position), at 24 percent, while skilled manual workers report a slightly higher level than technicians (the lower-grade service position), at 20 percent compared to 16 percent. Unskilled workers report lower levels of board volunteering than those in occupations within the service class, skilled manual workers, and skilled clerks.

Second, the figures indicate that the class pattern varies horizontally across segments of the scheme. Most notably, the level of board volunteering is 5 percentage points lower among technical experts than among higher-grade managers and administrators and socio-cultural professionals, and 7–8 percentage points lower among technicians than among lower-grade managers and administrators and socio-cultural semi-professionals. Skilled service workers also volunteer less often than skilled manual workers and skilled clerks (16 percent compared to 20 and 19 percent, respectively). The self-employed report is comparable to that of the higher-grade service class positions (24 percent). Among retirees, welfare recipients, students, and others outside the labor market, the share is 22 percent, between the levels observed for skilled workers and lower-grade service classes. Overall, the differences between classes are moderate.

Regarding the economic, cultural, and social resource variables, as expected, the share with a university or college education increases along the vertical axis of the class scheme. The score on the average number of books in the home varies little. Household income also shows limited variation, although it is higher among service class positions than working class positions. For the measures of social resources, we see minor class differences in the number of friends and in trust of others. The share who knows someone in a leading position is higher for upper class positions. Knowing someone who can help find work and who can lend money varies across managerial and socio-cultural positions. The patterns suggest that resources vary with social class, although differences on some of the measures are moderate.

Regression Analysis

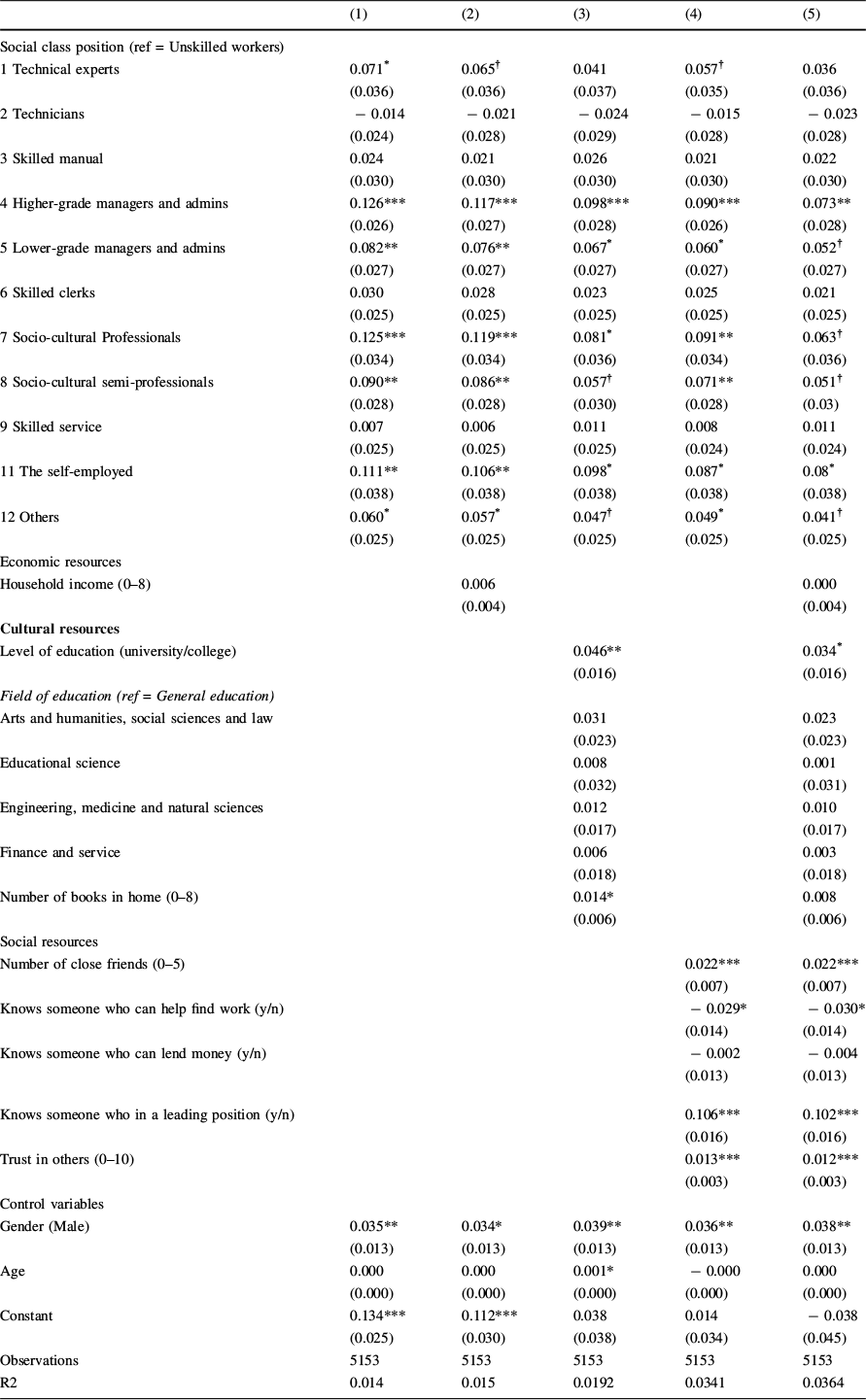

Table 3 reports linear probability models with board volunteering as the dependent variable. All models include social class position and control for gender and age to avoid confounding. Unskilled workers serve as the reference group. We estimate separate models that add, in turn, economic, social, and cultural resources, followed by a model including all three. Using the full model, we assess both vertical and horizontal class differences and the extent to which individual resources explain the differences.

Table 3 Linear probability model with board volunteering as the dependent variable

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Social class position (ref = Unskilled workers) |

|||||

1 Technical experts |

0.071* |

0.065† |

0.041 |

0.057† |

0.036 |

(0.036) |

(0.036) |

(0.037) |

(0.035) |

(0.036) |

|

2 Technicians |

− 0.014 |

− 0.021 |

− 0.024 |

− 0.015 |

− 0.023 |

(0.024) |

(0.028) |

(0.029) |

(0.028) |

(0.028) |

|

3 Skilled manual |

0.024 |

0.021 |

0.026 |

0.021 |

0.022 |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

|

4 Higher-grade managers and admins |

0.126*** |

0.117*** |

0.098*** |

0.090*** |

0.073** |

(0.026) |

(0.027) |

(0.028) |

(0.026) |

(0.028) |

|

5 Lower-grade managers and admins |

0.082** |

0.076** |

0.067* |

0.060* |

0.052† |

(0.027) |

(0.027) |

(0.027) |

(0.027) |

(0.027) |

|

6 Skilled clerks |

0.030 |

0.028 |

0.023 |

0.025 |

0.021 |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

|

7 Socio-cultural Professionals |

0.125*** |

0.119*** |

0.081* |

0.091** |

0.063† |

(0.034) |

(0.034) |

(0.036) |

(0.034) |

(0.036) |

|

8 Socio-cultural semi-professionals |

0.090** |

0.086** |

0.057† |

0.071** |

0.051† |

(0.028) |

(0.028) |

(0.030) |

(0.028) |

(0.03) |

|

9 Skilled service |

0.007 |

0.006 |

0.011 |

0.008 |

0.011 |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.024) |

(0.024) |

|

11 The self-employed |

0.111** |

0.106** |

0.098* |

0.087* |

0.08* |

(0.038) |

(0.038) |

(0.038) |

(0.038) |

(0.038) |

|

12 Others |

0.060* |

0.057* |

0.047† |

0.049* |

0.041† |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

(0.025) |

|

Economic resources |

|||||

Household income (0–8) |

0.006 |

0.000 |

|||

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

||||

Cultural resources |

|||||

Level of education (university/college) |

0.046** |

0.034* |

|||

(0.016) |

(0.016) |

||||

Field of education (ref = General education) |

|||||

Arts and humanities, social sciences and law |

0.031 |

0.023 |

|||

(0.023) |

(0.023) |

||||

Educational science |

0.008 |

0.001 |

|||

(0.032) |

(0.031) |

||||

Engineering, medicine and natural sciences |

0.012 |

0.010 |

|||

(0.017) |

(0.017) |

||||

Finance and service |

0.006 |

0.003 |

|||

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

||||

Number of books in home (0–8) |

0.014* |

0.008 |

|||

(0.006) |

(0.006) |

||||

Social resources |

|||||

Number of close friends (0–5) |

0.022*** |

0.022*** |

|||

(0.007) |

(0.007) |

||||

Knows someone who can help find work (y/n) |

− 0.029* |

− 0.030* |

|||

(0.014) |

(0.014) |

||||

Knows someone who can lend money (y/n) |

− 0.002 |

− 0.004 |

|||

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

||||

Knows someone who in a leading position (y/n) |

0.106*** |

0.102*** |

|||

(0.016) |

(0.016) |

||||

Trust in others (0–10) |

0.013*** |

0.012*** |

|||

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

||||

Control variables |

|||||

Gender (Male) |

0.035** |

0.034* |

0.039** |

0.036** |

0.038** |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

|

Age |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.001* |

− 0.000 |

0.000 |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

Constant |

0.134*** |

0.112*** |

0.038 |

0.014 |

− 0.038 |

(0.025) |

(0.030) |

(0.038) |

(0.034) |

(0.045) |

|

Observations |

5153 |

5153 |

5153 |

5153 |

5153 |

R2 |

0.014 |

0.015 |

0.0192 |

0.0341 |

0.0364 |

Standard errors in parentheses

†p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Starting with model 1, compared to unskilled workers, higher-grade service positions across all three occupational segments and lower-grade service positions within managerial and socio-cultural occupations show a significantly higher probability of board volunteering. Skilled working-class positions show no significant effects, indicating a divide between service and unskilled working-class positions. The self-employed and those in the ‘Other’ category are also more likely to volunteer on boards than unskilled workers. Additionally, the model shows that men volunteer to a greater degree than women.

In model 2, which adds economic resources, household income has no significant effect on board volunteering, and the class coefficients are essentially unchanged. In model 3, which instead adds cultural resources, education level but not field of education significantly and positively influences the probability of board volunteering. The number of books in the home also has a small, positive effect. Class differences remain but are reduced, especially those within technical occupations. Notably, the difference between unskilled workers and either technical experts, technicians, or skilled manual workers is not significant. Model 4 adds social resources only. The number of close friends and the level of interpersonal trust both have significant and positive effects on board volunteering. Knowing someone who can help find work has a significant negative effect, while knowing someone who can lend money is not significant. Knowing someone in a leading position significantly increases the probability of board volunteering. As in model 3, class differences are reduced.

Model 5 includes all resource measures. The previously observed effects of cultural and social resources remain, and the effects of social class on board volunteering are reduced. There is no significant difference between technical positions and unskilled workers, but a class gradient persists within managerial and socio-cultural occupations. With the reduced magnitudes, both vertical and horizontal differences are smaller, though there still is a distinction in board volunteering between technical positions and the managerial and socio-cultural positions.

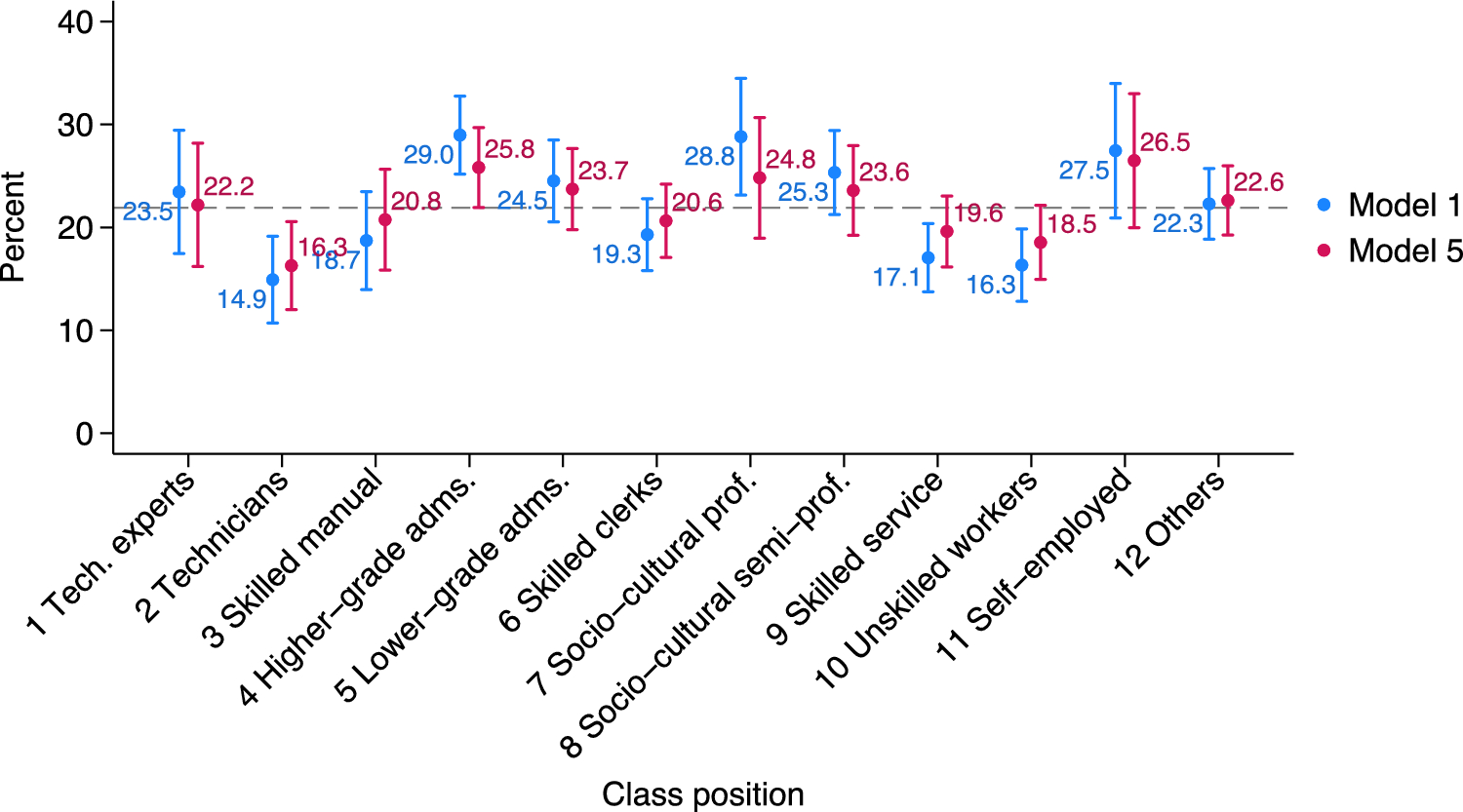

To illustrate the observed patterns, Fig. 1 shows predicted probabilities of board volunteering by class position based on model 5. The dashed line indicates the mean predicted probability. Predicted probabilities from model 1 (without the resource variables) are included as a reference for comparison.

Fig. 1 Predicted probabilities of board volunteering by class position with 95% CIs. Note: The dashed line shows the mean probability of board volunteering. Based on Table 3

The figure shows that the predicted probability of board volunteering is 25.8 percent for higher-grade managers and administrators, and 23.7 percent for lower-grade managers and administrators, compared with 20.6 percent for skilled clerks. For socio-cultural professionals and semi-professionals, it is 24.8 percent and 23.6 percent, compared to 19.6 percent for skilled service workers. For technical experts, it is 22.2 percent as compared to 16.3 percent for technicians and 20.8 percent for skilled manual workers. The predicted probability for unskilled workers is 18.5 percent. Relative to the mean predicted probability, higher-grade managers and administrators, socio-cultural professionals and semi-professionals, and the self-employed are more likely to volunteer on boards, whereas technicians, skilled service workers, and unskilled workers are less likely. At the same time, the figure illustrates that compared to model 1, the estimates for higher-grade managers and administrators and for socio-cultural professionals decline the most after controlling for gender, age, and economic, cultural, and social resources. However, differences across class positions are small and confidence intervals overlap.

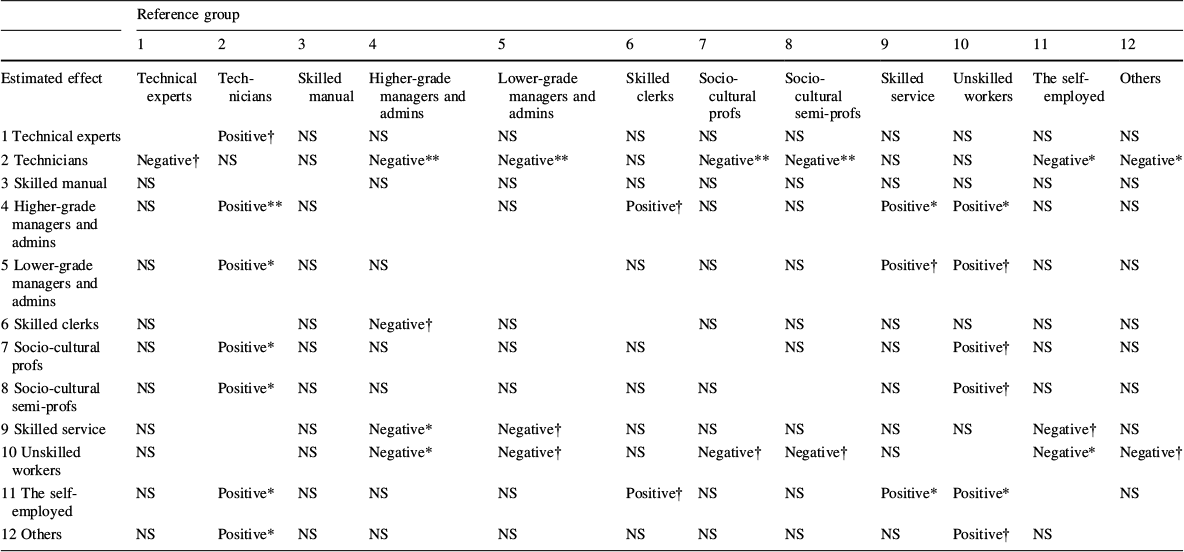

To discern significant differences, we therefore lastly vary the reference group in model 5. Table 4 shows a significantly higher probability of board volunteering for higher-grade managers and administrators than for both skilled clerks and skilled service workers, and for lower-grade managers and administrators than for skilled service workers but not skilled clerks. There are no significant differences within sociocultural occupations, nor between skilled manual workers and all other positions. The main horizontal difference concerns technicians, who are significantly less likely to volunteer than all higher- and lower-grade positions. In fact, the difference between technicians and higher-grade managers and administrators is quite large, 9.5 percentage points.

Table 4 Estimated effects on board volunteering of social class position depending on reference group

Reference group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

Estimated effect |

Technical experts |

Tech-nicians |

Skilled manual |

Higher-grade managers and admins |

Lower-grade managers and admins |

Skilled clerks |

Socio-cultural profs |

Socio-cultural semi-profs |

Skilled service |

Unskilled workers |

The self-employed |

Others |

1 Technical experts |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

|

2 Technicians |

Negative† |

NS |

NS |

Negative** |

Negative** |

NS |

Negative** |

Negative** |

NS |

NS |

Negative* |

Negative* |

3 Skilled manual |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

||

4 Higher-grade managers and admins |

NS |

Positive** |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

Positive* |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

|

5 Lower-grade managers and admins |

NS |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

|

6 Skilled clerks |

NS |

NS |

Negative† |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

||

7 Socio-cultural profs |

NS |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

|

8 Socio-cultural semi-profs |

NS |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

|

9 Skilled service |

NS |

NS |

Negative* |

Negative† |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Negative† |

NS |

|

10 Unskilled workers |

NS |

NS |

Negative* |

Negative† |

NS |

Negative† |

Negative† |

NS |

Negative* |

Negative† |

||

11 The self-employed |

NS |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

NS |

NS |

Positive* |

Positive* |

NS |

|

12 Others |

NS |

Positive* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Positive† |

NS |

|

Note: Based on model 5 in Table 3. NS = Non-significant

†p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Concluding Discussion

Our main findings show that individuals in higher-grade, and to some extent lower-grade, service class positions within managerial and socio-cultural occupations are more likely to volunteer on boards than those in skilled and unskilled working-class positions. However, the largest difference is between higher and lower-grade service class positions across two specific segments in the class scheme: higher-grade administrators and managers are much more likely to volunteer than technicians. We also find that class effects are moderately reduced only in some instances when taking economic, social, and cultural resources into account, and among our measures only the level of education and those related to social network resources have noteworthy effects on board volunteering. As such, class differences in board volunteering are to a limited degree explained by individual resources. Differences in board volunteering between higher and lower classes align with theoretical expectations related to variations in autonomy, authority, and security associated with “the service relationship” and “the labor contract” (Reference GoldthorpeGoldthorpe, 2000), and how employment relations can be transferable to board recruitment processes. Specifically, the positive effects for higher- and lower-grade managers and administrators support the argument that administrative, financial, and legal expertise are valued in board recruitment. Similarly, the positive effects for socio-cultural professionals and semi-professionals fit the expectation that they are valued for their expertise on community needs and that they may be motivated by mission alignment. The absence of a clear pattern for technical positions may reflect that their skills are harder to translate into board volunteering, limiting organizational demand or personal motivation.

Furthermore, an important implication is that voluntary organizations’ need for expertise to navigate more complex environments indeed may be associated with stronger recruitment from the upper middle class even in the egalitarian Norwegian context, although we cannot make causal inferences to this effect. If so, however, this can weaken the broad member representation that traditionally has been viewed as fundamental to the democratic character of voluntary organizations in Norway. However, our findings also speak to a more general context-independent managerial problem of a potential legitimacy gap in organizational governance, where overreliance on “expert volunteers” risks underrepresenting those with feet on the ground and who have first-hand knowledge of members’ experiences and community needs. To address this, voluntary organizations may consider deliberate strategies to balance the need for specialized expertise with grassroots representation. Ensuring that frontline members and volunteers are directly represented on boards could offset a possible upper-class bias if not necessarily reduce it altogether. More realistically perhaps, strengthening parallel committee structures that give this group more meaningful influence over programmatic and operational issues can be important, provided that their input is acknowledged and integrated in board decision-making. Another approach is leadership programs that aim to empower ordinary members and volunteers to take on board responsibilities and positions of trust within the organizations, particularly among typically underrepresented groups such as those with an ethnic minority background. By highlighting these tensions, our study underscores how a social class approach can inform not only the analysis of board volunteering but also practical strategies for sustaining democratic governance in voluntary organizations.

The egalitarian setting and the importance of democratic involvement in voluntary organizations in Norway likely shape our findings. In contexts with greater social inequality, and voluntary and nonprofit sectors more strongly dominated by professionalized organizations, such as in the United States and the United Kingdom, board volunteering may be even more concentrated among elites or higher classes possessing specific expertise and resources (e.g., Reference Abzug and GalaskiewiczAbzug & Galaskiewicz, 2001). Replicating this approach in countries with more pronounced inequalities could therefore shed light on whether the modest overall class differences we observe in Norway are amplified elsewhere, and whether alternative pathways into board volunteering emerge. At the same time, applying the methodology in less stratified contexts could reveal whether Norway's pattern represents an intermediate case. The availability of statistical packages for mapping occupational class schemes to ISCO codes means that occupational class analysis can be readily replicated in comparative studies using survey or register data. In this sense, the study demonstrates not only substantive findings for the Norwegian case but also a methodological template with significant potential for advancing cross-national research on social class and governance.

A limitation of our study is that we cannot assess how the effects of social class and individual resources on board volunteering vary across types of voluntary organizations. The skills emphasized in board recruitment probably differ depending on the field of activity, as variations in the composition of core stakeholders, external funders, and types of operational activities precede result in needs in terms of governance inputs. For example, sports clubs may value persons with local networks and practical planning skills. Cultural organizations may seek those with artistic expertise or links to relevant funding bodies. Welfare-oriented organizations may prioritize policy knowledge or professional credentials. Assessing such field-specific dynamics would require a larger data set that allows for efficient estimation of within- and across-category variation, such as register data on board members. Future research based on more comprehensive data on boards is also important to understand how organizational characteristics interact with dimensions of inequality, such as those based on ethnicity and gender.

In sum, our study contributes to volunteering research in several ways. Empirically, it uncovers more nuanced socioeconomic differences in board volunteering in Norway than previously reported, showing that both vertical and horizontal class positions matter. Theoretically, it demonstrates how a social class approach complements the resource-theory model by highlighting not only the volume but also the configuration of skills and expertise that influence access to governance roles. Beyond these contributions, the findings underscore important implications for practice. By applying an occupational class framework that can be replicated in other national contexts, the study also provides a methodological template for advancing cross-national research on social inequality in volunteering and governance.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and feedback.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Institute for Social Research. This study was supported by the Centre for Research on Civil Society and Voluntary Sector at the Institute for Social Research, Oslo, Norway.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Data Protection Services of the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research.